Background:

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is the second most common cancer, with approximately 700,000 new lesions annually in the US incurring treatment costs approximating 1.6 billion dollars.(1) cSCC incidence is expected to rise in an active, aging population increasing the need for new therapeutic strategies.(2) Since cSCCs typically arise from actinic keratoses (AKs) and squamous cell carcinoma in situ (SCCIS), effective treatment of these precursor lesions could decrease the number of cSCCs.(3) Current treatments for AKs/SCCIS include cyrotherapy, curettage or excision which leads to skin dyspigmentation and/or scarring at significant financial cost. Topical therapies for AKs/SCCIS include 5–fluorouracil (5-FU), imiquimod, diclofenac and ingenol mebutate. 5-FU and imiquimod produce prominent inflammation limiting compliance, and diclofenac has demonstrated suboptimal clearance rates.(4, 5) Ingenol mebutate is irritating, promotes endothelial cell necrosis and is costly compared to other therapies.(6, 7) Therefore, there is a medical need for effective topical AK therapeutics that lack adverse side effects.

One potential new approach to treat AKs/SCCIS would be to test the efficacy of topical small molecule kinase inhibitors (SMKIs) targeting drivers of growth in lesional keratinocytes.(8) One biologically plausible class of kinases to target is the Src-family tyrosine kinases (SFKs) which are known drivers of human cSCCs and shown to be activated in human AKs/SCCIS.(8, 9) The other key consideration is to identify molecules that can effectively penetrate the thickened stratum corneum and epithelial layers found in AKs/SCCIS/cSCCs. It has been shown that the human epidermal barrier may be permeable to some organic molecules with a size of 500 daltons or less.(10) We identified dasatinib, a small molecule inhibitor of SFKs with a molecular weight of 488 daltons, as a potential candidate molecule that may penetrate the epidermal barrier to significantly inhibit SFKs driving AK/SCCIS growth and induce lesion regression.(8, 11)

Questions addressed:

We hypothesized that topical kinase inhibitors targeting tyrosine kinases or downstream oncogenic pathways might be effective for treating skin cancer. To test this hypothesis, we used K14-Fyn Y528F transgenic mice which represent an in vivo skin cancer model that produces cSCCs and precancerous lesions analogous to corresponding human lesions.(12) In this model, the cSCCs show activation of SFKs and downstream oncogenic signaling pathways including the PI3K/mTOR, Ras/MAPK and Jak/STAT pathways. This transgenic model provides a useful tool for screening topical kinase inhibitors that may be efficacious in treating skin cancer.

Using this model as a screening tool, we applied topical dasatinib and BEZ235, an inhibitor of the PI3K/mTOR pathway, to cSCCs and compared their efficacy to induce cSCC regression against vehicle and the first-line topical agent, 5-fluorouracil.

Experimental design:

Five-to-six week-old K14-Fyn Y528F mice with cSCCs were divided into 3 cohorts for topical treatment: control (18 cSCCs), dasatinib (25 cSCCs) and 5-FU (18 cSCCs). Inclusion criteria were that cSCCs needed to be 3×3 mm or larger; such lesions have keratotic scale and a thickness similar or greater than that seen in human AKs/SCCIS which is a more stringent therapeutic test than treating smaller lesions that occur in this model. Prior to treatment, cSCCs were measured with calipers in the two longest dimensions to calculate tumor area and then photographed. These procedures were repeated weekly during treatment to follow cSCC size for treatment efficacy. cSCCs were treated daily (7x/week) with vehicle (DMSO), dasatinib solution (0.89%) and 5% 5-FU. In analogous experiments, mice with cSCCs were divided into 2 cohorts for topical treatments: vehicle control (10 cSCCs) and BEZ-235 (1%) (15 cSCCs). Biopsies of representative cSCCs were taken at time 0 and at the indicated time points to assess tumor regression, inflammation and epidermal ulceration.

Results:

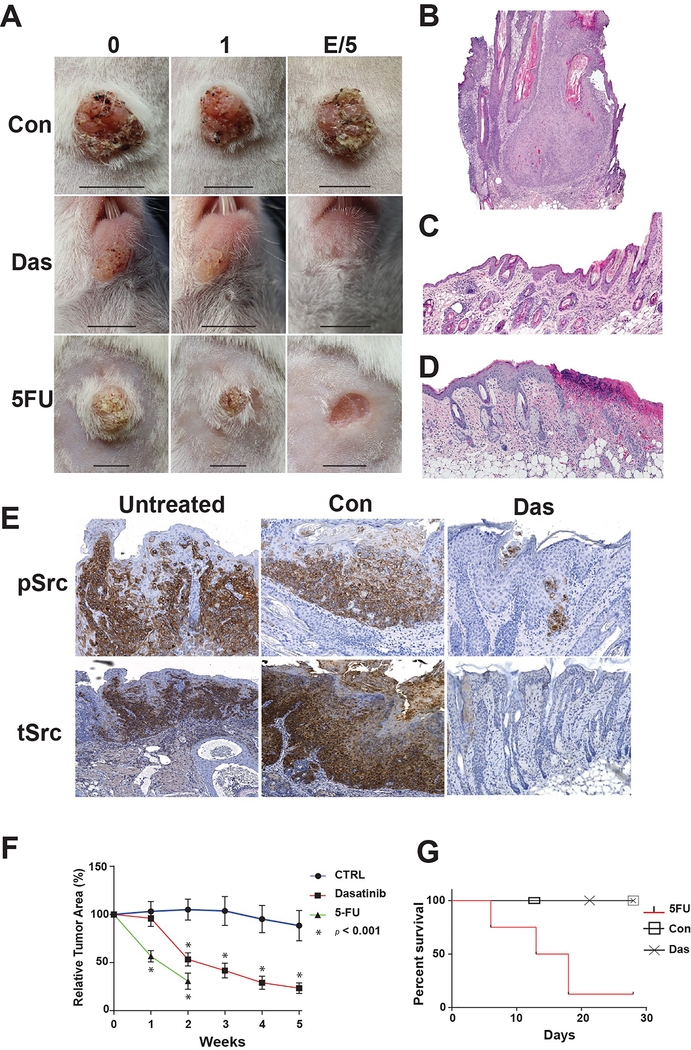

Topical Dasatinib (0.89%) applied daily induced 45% and 77% regression of cSCCs after two and five weeks of treatment respectively compared to control, p<0.05 (Figs 1A, B, C, D and F). Topical 5-FU (5%), induced 70% regression at two weeks. cSCC regression with 5-FU was associated with epidermal ulceration in 2/15 of tumors and 7/8 mice died by day 18 of 5-FU treatments (Figs 1A, D and G). No cSCC ulceration or murine mortality were seen in the dasatinib or control cohorts (Fig. 1G). During the first three weeks of vehicle application, control cSCCs enlarged. After 5 weeks of vehicle application, the control cSCCs only lost 12% of relative tumor area.

Figure 1. Topical Dasatinib induces cSCC regression and inhibits Src oncodrivers without ulceration or mortality.

A) Representative images of cSCCs in K14-Fyn Y528F mice treated with vehicle (Con), Dasatinib (Das) or 5-FU taken at time 0, 1 week or 5 weeks/treatment endpoint. Scale bar- 5 mm B-D) Representative histologic images of cSCCs at the treatment endpoints: Vehicle (B), Dasatinib (C) or 5-FU (D). E) Immunostaining for activated Src kinases and total Src kinases (tSrc) was performed on representative sections of untreated, vehicle-treated (Con) or dasatinib-treated (Das) cSCCs. Near complete loss of activated Src kinases was noted in dasatinib-treated, regressing cSCCs. Immunostaining for total Src kinases demonstrated a similar, but broader staining pattern. F) Relative tumor area as a function of treatment and time. Vehicle-treated cSCCs, N=18, grow and persist while dasatinib-treated cSCCs demonstrate regression by week 2, N=25. 5-FU treated lesions demonstrate significant regression by week 1, N=13. Error bars indicate SEM. * p < 0.05 G) Mice treated with 5-FU demonstrate high mortality by 18 days. No mortality noted in vehicle or dasatinib treated cohorts.

Immunohistochemical analysis of representative lesions from control and dasatinib- treated cSCCs demonstrated lower levels of activated Src kinases compared to vehicle-treated and untreated lesions (Fig 1E). Immunohistochemical analysis for total Src kinases showed a staining pattern similar to activated Src kinase in all three sets of lestions (Fig 1E). However, staining for total Src kinase demonstrated broader staining but much weaker in the dasatinib-treated lesions (Fig 1E). These data indicate that dasatinib-treatment may activate cellular mechanisms that downregulate activated Src kinases. The data show that dasatinib-induced regression of the cSCCs is associated with decreased levels of activated and total Src kinases that approximate levels seen in unremarkable epidermis.

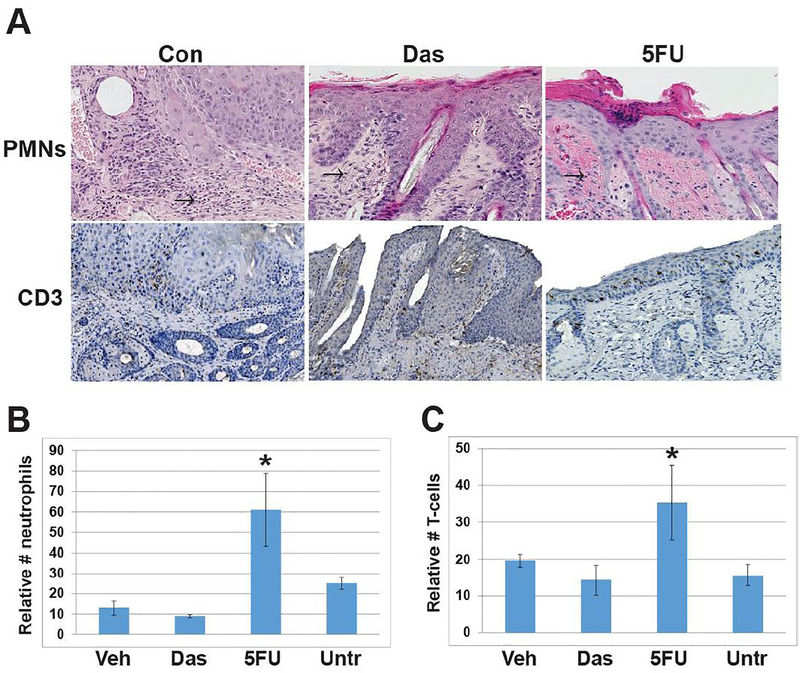

The level of inflammation associated with topical dasatinib and 5-FU treatment was determined by assessing the number of dermal CD3-positive T cells and neutrophils in three representative treated lesions from each cohort. The level of inflammation associated with treatment was determined by counting CD3-positive T-cells and neutrophils in the dermis at the treatment site. Dasatinib treatment of cSCCs did not increase levels of CD3-positive T cells or neutrophils compared to untreated cSCCs and vehicle-treated lesions (Fig. 2). In contrast, topical 5-FU induced inflammation and was associated with higher numbers of CD3-positive T (p=0.03) cells and neutrophils (p=0.04) compared to dasatinib-treated mice. In some cases, topical 5-FU induced epidermal ulceration (Figs 1 and 2). Overall, dasatinib induced cSCC regression similar to topical 5-FU with less inflammation and no ulceration.

Figure 2. Topical Dasatinib does not promote dermal inflammation as does 5-FU.

A) Representative images of cSCCs at treatment endpoints were assessed for neutrophils and T-cell numbers by histomorphologic analysis and CD3 immunostaining. (Con), Dasatinib (Das) or 5-FU taken at time 0, 1 week or 5 weeks/treatment endpoint. Arrows indicate neutrophils. B) Graphical representation of dermal neutrophil counts of biopsies from three representative cSCCs from each cohort, error bars indicate SEM. 5-FU vs. Das, * p= 0.04 C) Graphical representation of dermal CD3 T cell counts from three representative cSCCs from each cohort, error bars indicate SEM. 5-FU vs. Das, * p= 0.03

Since SFKs are known to activate the PI3K/mTOR pathway in the K14-Fyn Y528F model, we determined if topical application of BEZ-235, a small molecule PI3K/mTOR inhibitor, to cSCCs induced regression similar to that seen with dasatinib. Topical application of 1% BEZ-235 induce regression of cSCCs by over 60% compared to vehicle-treated lesions by 5 weeks without significant erythema or ulceration (Fig S1). The BEZ-235-induced regression was found to be statistically significant at each weekly timepoint p<0.01 (Fig S1).

Conclusions:

As a first step in identifying new approaches to treat skin cancer, we hypothesized that topical application of small molecule kinase inhibitors could inhibit the growth of cSCCs in the K14-Fyn Y528F skin cancer model. It has been demonstrated that human AKs, SCCIS and cSCCs contain increased levels of activated Src kinases compared with adjacent unremarkable epidermis. These data support the hypothesis that that Src kinases represent a potential therapeutic target in human AKs/SCCIS/cSCCs.(9)

To further test this hypothesis, cSCCs were treated once daily with 0.89% topical dasatinib; treated cSCCs demonstrated almost 80% regression by 5 weeks while vehicle-treated lesions did not demonstrate significant regression. cSCCs treated with dasatinib demonstrated a similar level of cSCC regression comparable to topical 5% 5-FU after two weeks of daily application. However, topical dasatinib induced cSCC regression without inducing prominent inflammation or ulceration as was seen with 5-FU. In addition, dasatinib was well tolerated by mice while topical 5-FU led to mortality after two weeks. The mortality rate noted in the K14-Fyn Y528F mice treated with topical 5FU is elevated compared to other studies.(13) This may be due to increased drug absorption due to impaired skin barrier formation in the cSCCs leading to elevated systemic levels or to increased production of toxic metabolites in the K14-Fyn Y528F line.(14)

In parallel experiments, topical BEZ-235 also induced regression of cSCCs compared to vehicle without inducing ulceration or significant erythema. Together, these data suggest that topical application of small molecule kinase inhibitors targeting key kinases driving keratinocyte growth may be useful for treating cSCCs and related precursor lesions. These data also raise the possibility that topical application of multiple small molecule kinase inhibitors together targeting the drivers of AKs/SCCIS/SCCs may be more effective than a single compound.

Methods:

In vivo cSCC model:

The K14-Fyn Y528F transgenic mouse was developed and characterized as previously described and is available from Jackson Laboratories: FVB.Cg-Tg(KRT14-Fyn*)aJsey/J.(12) This transgenic mouse spontaneously develops cSCCs that resemble human lesions at the histologic and molecular levels. Study inclusion criteria for mice: 1) genotype positive, 2) non-breeding, and cSCCs greater than 3 mm in diameter were included in the study. The cohorts of mice were as follows: Veh (DMSO)-8 mice with 18 cSCCs, average of 2.3 tumors per mouse; Dasatinib-15 mice with 25 cSCCs, average of 1.7 tumors per mouse; 5FU-8 mice with 13 cSCCs, average of 1.6 tumors per mice; Veh (DMF)-8 mice with 10 cSCCs, 1.3 cSCCs per mouse; BEZ-235–4 mice with 15 tumors, 3.8 cSCCs per mouse. The five cohorts of mice control Veh (DMSO), 5FU, dasatinib, Veh (DMF) and BEZ235 were matched for age and closely for sex.

Topical application of dasatinib, BEZ235 and 5-FU:

DMSO was used as the vehicle control. Dasatinib (LC Laboratories #D-3307) was dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 20 mM equivalent to 0.89%. BEZ-235 (LC Labs Cat. No. N-4288) was dissolved in dimethylformamide (Fisher Cat No. AA43997AE) at 1% (g/g). Topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU, 5% cream, Taro Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd. NDC 51672–4118-6). Mice received approximately 100–150 mg of cream topically per day on each cSCC which contains 5–7.5 mg of 5FU. All topical agents and controls were applied once daily to cSCCs with a cotton swab to uniformly cover the surface of the lesion.

Monitoring cSCC size during treatment:

cSCCs were photographed with a ruler at time 0 and weekly during topical treatment. The area of each cSCC was determined using calipers to measure to two longest orthogonal dimensions at time 0 and weekly during treatment. Tumor measurements were reported as mm2 and ceased if skin became ulcerated or the murine host died. Relative tumor area as a function of time was calculated by using the initial tumor area as 100% and subsequent tumor areas were compared to time 0 area.

Tissue histology and immunohistochemistry:

cSCC tumor tissue was harvested from representative lesion prior to initiating treatment, at 2–3 weeks and at the end of treatment. Harvested tissues were fixed in 10% formalin for tissue processing. Histologic slides with hematoxylin and eosin staining were reviewed. The neutrophilic inflamatory response was assessed by morphology on H&E staining, inflammatory cells with a segmented nucleus and cytoplasmic granules. Murine CD3 positive T cells were detected using immunohistochemistry with an CD3 antibody, 1:100 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). To assess cell numbers, five square millimeters of dermis was examined to determine the number of T cells and neutrophils in each biopsy specimen. Cells in the epidermis, hair follicle or fat layer were not counted. Biopsies from 3 different mice in the indicated cohorts were evaluated. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s T test for the means.

Tissue sections were subjected to immunohistochemistry staining as previously reported (Zhao, 2009). Phosphorylated Src kinases was detected using pY416 rabbit Ab from Cell Signaling, #2101 at a 1:20 dilution. Total Src kinases were detected using the SRC2 (sc-18) antibody from Santa Cruz at a 1:100 diltion. All photomicrographs were obtained using a Keyence microscope.

Statistical Analysis:

All statistical calculations were performed using the Student’s t-test for comparison of the means.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This work has been supported in part by the Department of Dermatology, Perelman School of Medicine, the University of Pennsylvania SBRDC NIH P30-AR069589 and NIH RO1 CA-165836 to JTS.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: JTS and the University of Pennsylvania are co-owners of US patents 9,084,790 B2 and 9,555,034 B2 outlining the use of topical small molecule kinase inhibitors to treat skin cancer. These patents have not yet been subject to a licensing agreement.

References:

- 1.Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Harris AR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, 2006. Arch Dermatol 2010: 146: 283–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.General S. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Skin Cancer. 2014. [PubMed]

- 3.Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, Luque C, Eide MJ, Bingham SF. Actinic keratoses: Natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the Veterans Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention Trial. Cancer 2009: 115: 2523–2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bagatin E, Teixeira SP, Hassun KM, Pereira T, Michalany NS, Talarico S. 5-Fluorouracil superficial peel for multiple actinic keratoses. International journal of dermatology 2009: 48: 902–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kose O, Koc E, Erbil AH, Caliskan E, Kurumlu Z. Comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of 3% diclofenac sodium gel and 5% imiquimod cream in the treatment of actinic keratosis. J Dermatolog Treat 2008: 19: 159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li L, Shukla S, Lee A, et al. The skin cancer chemotherapeutic agent ingenol-3-angelate (PEP005) is a substrate for the epidermal multidrug transporter (ABCB1) and targets tumor vasculature. Cancer Research 2010: 70: 4509–4519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vegter S, Tolley K. A network meta-analysis of the relative efficacy of treatments for actinic keratosis of the face or scalp in Europe. PLoS One 2014: 9: e96829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ratushny V, Gober MD, Hick R, Ridky TW, Seykora JT. From keratinocyte to cancer: the pathogenesis and modeling of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Invest 2012: 122: 464–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ayli EE, Li W, Brown TT, Witkiewicz A, Elenitsas R, Seykora JT. Activation of Src-family tyrosine kinases in hyperproliferative epidermal disorders. J Cutan Pathol 2008: 35: 273–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bos JD, Meinardi MM. The 500 Dalton rule for the skin penetration of chemical compounds and drugs. Exp Dermatol 2000: 9: 165–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kramer B, Kneissle M, Birk R, Rotter N, Aderhold C. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibition in HPV-related Squamous Cell Carcinoma Reveals Beneficial Expression of cKIT and Src. Anticancer Res 2018: 38: 2723–2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao L, Li W, Marshall C, et al. Srcasm inhibits Fyn-induced cutaneous carcinogenesis with modulation of Notch1 and p53. Cancer Res 2009: 69: 9439–9447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shim IK, Yi H-J, Yi H-G, et al. Locally-applied 5-fluorouracil-loaded slow-release patch prevents pancreatic cancer growth in an orthotopic mouse model. Oncotarget 2017: 8: 40140–40151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arbiser JL, Bonner MY, Ward N, Elsey J, Rao S. Selenium unmasks protective iron armor: A possible defense against cutaneous inflammation and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.