Abstract

Corneal neovascularization (CNV) leads to the loss of corneal transparency and vision impairment, and can ultimately cause blindness. Topical corticosteroids are the first line treatment for suppressing CNV, but poor ocular bioavailability and rapid clearance of eye drops makes frequent administration necessary. Patient compliance with frequent eye drop regimens is poor. We developed biodegradable nanoparticles loaded with dexamethasone sodium phosphate (DSP) using zinc ion bridging, DSP-Zn-NP, with dense coatings of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG). DSP-Zn-NP were safe and capable of providing sustained delivery of DSP to the front of the eye following subconjunctival (SCT) administration in rats. We reported that a single SCT administration of DSP-Zn-NP prevented suture-induced CNV in rats for two weeks. In contrast, the eyes receiving SCT administration of either saline or DSP solution developed extensive CNV in less than 1 week. SCT administration of DSP-Zn-NP could be an effective strategy in preventing and treating CNV.

Keywords: ocular drug delivery, polymer, corticosteroid, neovascularization, animal model

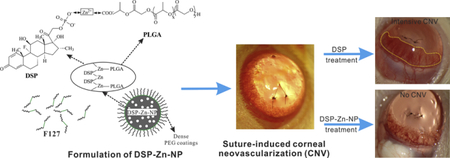

Graphical Abstract

Dexamethasone sodium phosphate (DSP) was encapsulated into PLGA nanoparticles (DSP-Zn-NP) with dense PEG coatings through a zinc ion chelation following a nanoprecipitation preparation. One single subconjunctival administration of DSP-Zn-NP effectively inhibited the suture-induced corneal neovascularization for up to 2 weeks in a rat model.

1. Introduction

Various pathological conditions can induce the invasion of new vessels (neovascularization) from the limbus to the typically avascular cornea.1 Corneal neovascularization (CNV) can eventually lead to loss of corneal transparency and decreased visual acuity. Topical corticosteroids are the first line treatment for CNV, and the anti-angiogenic effect of various corticosteroids, including dexamethasone, has been demonstrated in different animal models and in clinical practice.1 The ability of anti-angiogenic corticosteroid on CNV may be partially attributed to the inhibition of the secretion of growth factors, especially vascular endothelial derived growth factor (VEGF), and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs).1 However, topically applied drugs typically do not penetrate the cornea efficiently, and the small fraction of drug that is absorbed is usually rapidly cleared.2 Inhibiting and/or treating CNV requires frequent administration of topical corticosteroids1, and compliance with frequent dosing regimens is poor. Reducing or eliminating dependence on patient compliance is an important next step in the management of CNV.3

We developed dexamethasone sodium phosphate (DSP) encapsulated nanoparticles via zinc ion bridging (DSP-Zn-NP) using carboxyl terminated poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA-COOH) followed by nanoprecipitation.4 DSP-Zn-NP exhibited high drug loading and sustained drug release.4 Pluronic F127 at the nanoparticle preparation led to dense PEG coatings on nanoparticle, which are critical to decrease the inflammation following ocular administration of nanoparticles.5 We have also shown that SCT administration of DSP-Zn-NP with dense PEG coatings cause no toxicity in the injection site of the eye.4 Here, we demonstrate that a single SCT DSP-Zn-NP provides safe and effective inhibition of CNV in a rat model for up to two weeks.

2. Materials and Methods

DSP-Zn-NP were prepared and characterized as previously reported.4 The CNV rat model was set up at day0 (Figure S1),6 immediately followed by SCT administration of different therapeutics. Details are provided in Supplementary Materials.

3. Results and discussion

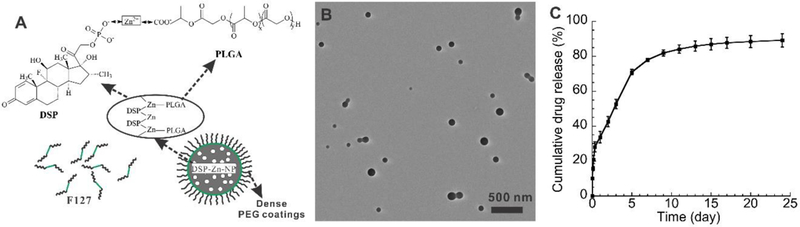

Drugs administered by SCT administration transport into the eye by trans-scleral diffusion,7, 8 a process that is limited for drugs that are poorly water-soluble.9 However, the therapeutic effects of water-soluble corticosteroids injected SCT are short-lived,10 such that frequent injections are required.11 Therefore, we sought to formulate a delivery system for water-soluble corticosteroid, DSP, by noncovalent zinc ion bridging between carboxyl groups on PLGA and phosphate groups on DSP (Figure 1A). We achieved dense PEG coatings on DSP-Zn-NP using a triblock copolymer of poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(propylene oxide)-poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG-PPO-PEG) (Pluronic F127) (Figure 1A), and the hydrophobic PPO chains (green) on F127 provided strong noncovalent coating on hydrophobic PLGA nanoparticles.12 The DSP-Zn-NP were spherical particles (Figure 1B) with an average diameter of 200nm and a polydispersity index of 0.12 indicating relatively uniform particle size distribution. DSP-Zn-NP had DSP loading of ~8wt%. FTIR confirmed the existence of chemical bonds from phosphate-zinc (bands at 3011, 2645, 23230 and 2162 cm−1) in DSP-Zn-NP (Figure S2). Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy measured the zinc content of 0.91wt% in DSP-Zn-NP, suggesting an approximately 1:1 molar ratio of zinc to DSP by comparing with the DSP content measured from HPLC. The DSP-Zn-NP released DSP in a sustained manner for about 3 weeks in vitro (Figure 1C). The gradual release of DSP without a significant initial burst suggested complete incorporation of DSP into nanoparticle through zinc ion bridging rather than adsorption to particle surface. The DSP release is controlled by polymer degradation, and can be further adjusted by changing the compositions (molecular weight and LA/GA ratio) of PLGA/PLA polymers and the blend with PLGA-PEG/PLA-PEG copolymers.13 As reported previously, one SCT administration of DSP-Zn-NP delivered sustained levels of DSP to the aqueous humor for more than 7days, whereas DSP were nearly undetectable in the aqueous humor 1day after injection of free DSP.4

Figure 1.

(A) Scheme of DSP-Zn-NP prepared through the ion bridging with zinc at the presence of F127. (B) TEM image of the DSP-Zn-NP, and (C) DSP release profile from DSP-Zn-NP in vitro.

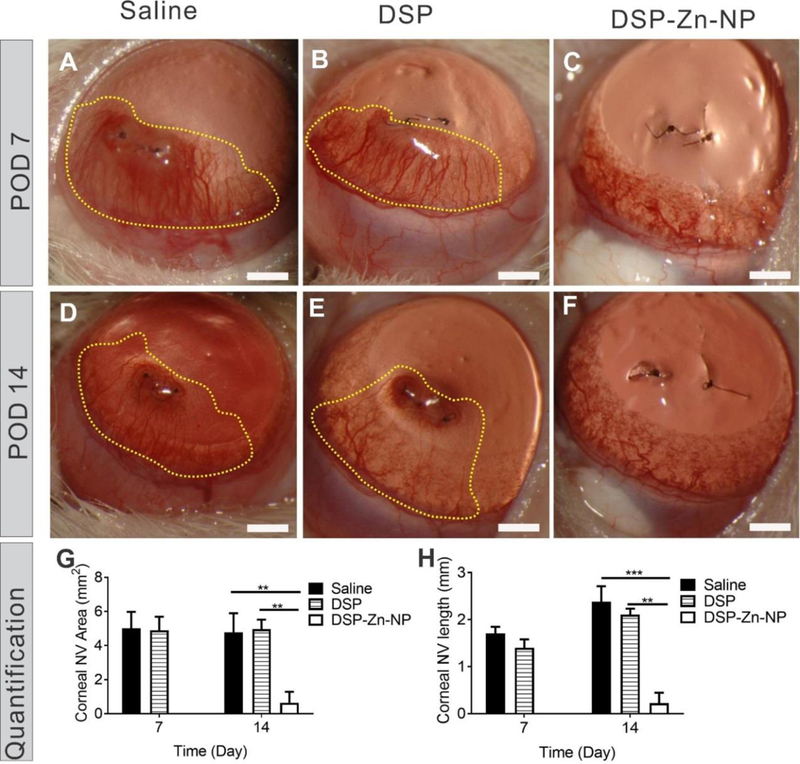

In the saline-treated group, CNV reached the suture position (2mm from limbus) by postoperative day 7 (POD7) (Figure 2A) with the average area of 5.0±2.1 mm2 and length of 1.7±0.3 mm (Figure 2G-H). The new vessels continued to grow through POD14 (Figure 2D) with the average area of 4.8±2.5 mm2 and length of 2.3±0.8 mm (Figure 2G-H). Similarly, SCT DSP at the time of intrastromal suture placement did not inhibit CNV (Figure 2B-D), with the average area of 5.0±0.6 mm2 and average length 2.0±0.1 mm by POD14 (Figure 2G-H). It is thought that water-soluble drugs like DSP can achieve more efficient intraocular delivery following SCT administration (through trans-scleral diffusion) as compared to administration of the same drug in conventional eye drops.8 However, the therapeutic effects of water-soluble DSP are still short-lived following SCT administration due to rapid drug clearance.10 In rats, only 0.4% of the original dose remained in the anterior chamber 2h after SCT administration of DSP solution, and the DSP level in the anterior chamber dropped below the detection limit within 24h.4

Figure 2.

Representative slit lamp images of rat corneas at POD7 and POD14 after SCT administration of (A, D) saline, (B, E) DSP solution (180 µg DSP) and (C, F) DSP-Zn-NP (180 µg DSP). Quantified (G) CNV area and (H) CNV length. The dotted yellow lines indicate CNV areas. Mean±SEM, n=6. No stats indicated for the POD7 in G and H because of no new blood vessels observed at this timepoint. Scale bar: 1mm.

In contrast to treatment with saline or DSP solution, DSP-Zn-NP eliminated CNV in the same rat model by POD7 (Figure 2C), and the suppression of CNV lasted to POD14 (Figure 2F). Only 1 of 6 rats treated with DSP-Zn-NP showed evidence of mild CNV at POD14, with the average CNV area of 0.6±0.6 mm2 and length of 0.2±0.2 mm (Figure 2G-H). DSP release from DSP-Zn-NP in the SCT space significantly improved drug retention and prolonged drug levels in anterior chamber for more than 7days,4 which led to enhanced suppression of CNV in the rat model. PLGA NP will be gradually cleared by hydrolysis of PLGA ester linkage throughout the NP matrix (bulk erosion) in the presence of water in the surrounding conjunctiva tissues to produce lactic and glycolic acids, which will be eventually eliminated safely via the Krebs cycle by conversion to carbon dioxide and water.14

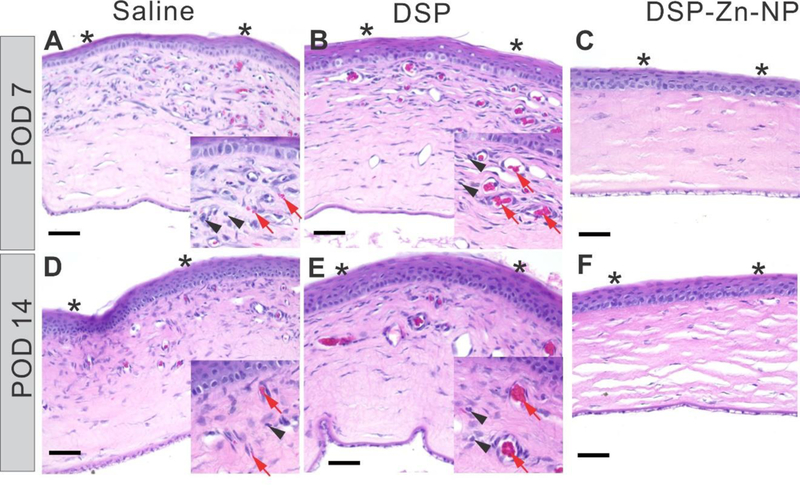

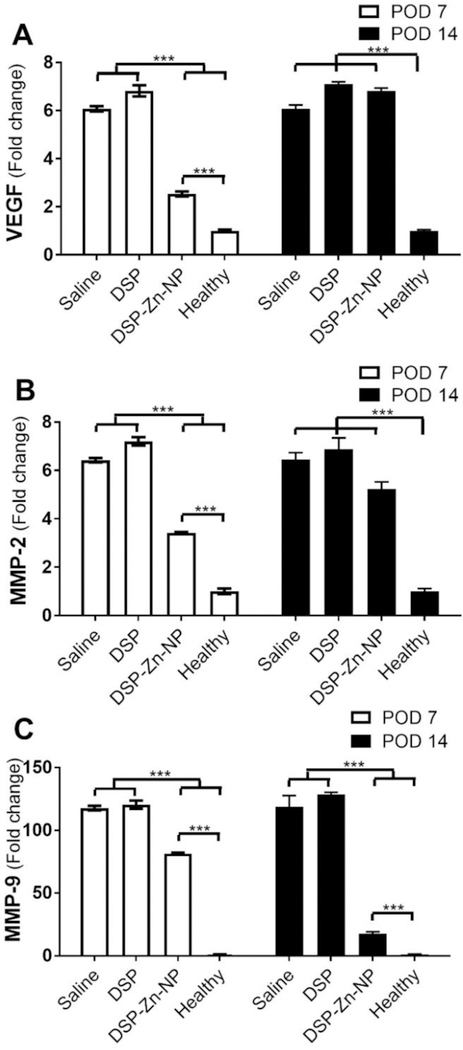

Infiltration of inflammatory cells (black arrow heads) and blood vessel (red arrows) were evident in cornea tissues of rats treated with saline (Figure 3A, D) and DSP (Figure 3B, E) at both POD7 and POD14. In comparison, the corneas of DSP-Zn-NP treated rats showed no signs of inflammation or neovascularization at POD7 or POD14 (Figure 3C, F). It implied that DSP could inhibit the activation and recruitment of inflammatory cells that release various inflammatory cytokines to stimulate angiogenesis,1 which is regarded as a driving force for CNV formation.15 We measured mRNA expression levels of growth factors implicated in CNV, and we found significant suppression of VEGF mRNA in the corneas of rats treated with DSP-Zn-NP in comparison to rats treated with either saline or DSP solution at POD7 (Figure 4A). The VEGF mRNA expression level in rats treated with DSP-Zn-NP increased to levels similar to those in the saline- and DSP-treated rats at POD14, which was the time when ocular DSP levels decreased to undetectable levels in DSP-Zn-NP treated rats.4 VEGF plays a critical role in CNV,16 as demonstrated by the inhibition of CNV using anti-VEGF antibodies.17–19 Figure 4B-C shows that SCT DSP-Zn-NP also significantly suppressed expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 mRNA in the sutured corneas compared to SCT saline or DSP solution at both POD7 and POD14. MMP enzymes degrade extracellular matrix and facilitate the migration of endothelial cells, allowing the formation of new vasculature.20 Upregulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 was found to be involved in CNV,15, 21 and therapies that inhibit MMPs have been found effective in inhibiting CNV.6, 22

Figure 3.

Representative histological images of the sutured corneas at POD7 and POD14 following treatment with SCT administration of (A, D) saline, (B, E) DSP or (C, F) DSP-Zn-NP. Corneal epithelia is marked with asterisk. Scale bar: 50µm.

Figure 4.

RT-PCR analysis of mRNA expression of (A) MMP-2, (B) MMP-9 and (C) VEGF in the corneas without sutures (Healthy) or with sutures following treatment with SCT DSP-Zn-NP, DSP or saline at POD7 and POD14. Mean±SEM, n=3.

Exposure to corticosteroids can cause an increase in intraocular pressure (IOP) and/or ocular toxicity under some circumstances.23 IOP did not increase in rats during 2 weeks after a single SCT DSP-Zn-NP in the current study (Figure S3). In our previous corneal allograft rejection study, we did not observe IOP increase upon weekly SCT administration of DSP-Zn-NP in rats.4

In summary, SCT administration of controlled-release DSP-Zn-NP formulations holds potential to provide sustained, therapeutic levels of DSP to the anterior segment of the eye without increasing IOP or causing toxicity at injection site for inhibition of CNV. CNV is known to cause corneal opacification, and also significantly increases the rate of immunological graft rejection of the keratoplasty.24 SCT DSP-Zn-NP will improve patient drug compliance and will reduce the chance of corneal transplantation rejection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by R01EY027827, Wilmer Core facility (P30-EY001765), the Raymond Kwok Family Research Fund, the Andreas Dracopoulos Research fund, the Richard Lindstrom Research Grant from Eye Bank Association of America, the Ralph E. Powe Junior Faculty Award from ORAU, and a grant from the King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital of Saudi Arabia.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The nanoparticle technology described in this publication is being licensed to GrayBug Vision Inc. Justin Hanes is a founder of GrayBug Vision, Inc. He owns company stock, which is subject to certain rules and restrictions under Johns Hopkins University policy. The terms of this arrangement are being managed by Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

References

- 1.Gupta D and Illingworth C, Treatments for corneal neovascularization: a review. Cornea 2011;30:927–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Urtti A, Challenges and obstacles of ocular pharmacokinetics and drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2006;58:1131–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz GF and Quigley HA, Adherence and persistence with glaucoma therapy. Surv Ophthalmol 2008;53:S57–S68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan Q, Xu Q, Boylan NJ, Lamb NW, G. Emmert D, Yang J-C, et al. , Corticosteroid-loaded biodegradable nanoparticles for prevention of corneal allograft rejection in rats. J Control Release 2015;201:32–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDonnell Peter J., Khan Yasin A., Lai Samuel K., Kashiwabuchi Renata T., Behrens Ashley and Hanes JS, Sustained Delivery of Therapeutic Agents to an Eye Compartment, U.S. Patent No. 8889193 B2, Issued November 18, 2014

- 6.Kim I-T, Park H-YL, Choi J-S and Joo C-K, Anti-angiogenic effect of KR-31831 on corneal and choroidal neovascularization in rat models. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012;53:3111–3119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leibowitz HM and Kupferman A, Periocular injection of corticosteroids-Experimental evaluation of its role in treatment of corneal inflammation. Arch Ophthalmol 1977;95:311–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGhee CNJ, Pharmacokinetics of ophthalmic corticosteroids. Br J Ophthalmol 1992;76:681–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prausnitz MR and Noonan JS, Permeability of cornea, sclera, and conjunctiva: A literature analysis for drug delivery to the eye. J Pharm Sci 1998;87:1479–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weijtens O, Feron EJ, Schoemaker RC, Cohen AF, Lentjes EGWM, Romijn FPHTM, et al. , High concentration of dexamethasone in aqueous and vitreous after subconjunctival injection. Am J Ophthalmol 1999;128:192–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalina RE, Increased intraocular pressure following subconjunctival corticosteroid administration. Arch Ophthalmol 1969;81:788–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang M, Lai SK, Wang YY, Zhong WX, Happe C, Zhang M, et al. , Biodegradable nanoparticles composed entirely of safe materials that rapidly penetrate human mucus. Angew Chem Int Ed 2011;50:2597–2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishihara T, Kubota T, Choi T, Takahashi M, Ayano E, Kanazawa H, et al. , Polymeric nanoparticles encapsulating betamethasone phosphate with different release profiles and stealthiness. Int J Pharm 2009;375:148–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee S, Hughes P, Ross A and Robinson M, Biodegradable Implants for Sustained Drug Release in the Eye. Pharm Res 2010;27:2043–2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Z-r, Li Y-p, Lin M-l, Su W-r, Zhang W-X, Zhang Y, et al. , Activated macrophages induce neovascularization through upregulation of MMP-9 and VEGF in rat corneas. Cornea 2012;31:1028–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amano S, Rohan R, Kuroki M, Tolentino M and Adamis AP, Requirement for vascular endothelial growth factor in wound- and inflammation-related corneal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1998;39:18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozdemir O, Altintas O, Altintas L, Yildiz DK, Sener E and Caglar Y, Effects of subconjunctivally injected bevacizumab, etanercept, and the combination of both drugs on experimental corneal neovascularization. Can J Ophthalmol 2013;48:115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffart L, Matonti F, Conrath J, Daniel L, Ridings B, Masson GS, et al. , Inhibition of corneal neovascularization after alkali burn: comparison of different doses of bevacizumab in monotherapy or associated with dexamethasone. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2010;38:346–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pérez-Santonja JJ, Campos-Mollo E, Lledó-Riquelme M, Javaloy J and Alió JL, Inhibition of corneal neovascularization by topical bevacizumab (anti-VEGF) and sunitinib (anti-VEGF and anti-PDGF) in an animal model. Am J Ophthalmol 2010;150:519–528.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stetler-Stevenson WG, Matrix metalloproteinases in angiogenesis: a moving target for therapeutic intervention. J Clin Invest 1999;103:1237–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kvanta A, Sarman S, Fagerholm PER, Seregard S and Steen B, Expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in inflammation-associated corneal neovascularization. Exp Eye Res 2000;70:419–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goktas S, Erdogan E, Sakarya R, Sakarya Y, lmaz M, Ozcimen M, et al. , Inhibition of corneal neovascularization by topical and subconjunctival tigecycline. J Ophthalmol 2014;2014:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zode GS, Sharma AB, Lin X, Searby CC, Bugge K, Kim GH, et al. , Ocular-specific ER stress reduction rescues glaucoma in murine glucocorticoid-induced glaucoma. J Clin Invest 2014;124:1956–1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stark WJ and Maguire MG, The collaborative corneal transplantation studies (CCTS). Effectiveness of histocompatibility matching in high-risk corneal transplantation. The Collaborative Corneal Transplantation Studies Research Group. Arch Ophthalmol 1992;110:1392–1403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.