Abstract

AIMS:

It is unclear if the presence of type-2 diabetes in one spouse is associated with the development of diabetes in the other spouse. We studied the concordance of diabetes among black and white participants in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study and summarized existing studies in a meta-analysis.

METHODS:

We conducted a prospective cohort analysis of ARIC data from 8077 married men and women (mean age 54 years) without diabetes at baseline (1987–89). Complementary log-log models that accounted for interval censoring was used to model the hazard ratio (HR) for the association of spousal diabetes status with the incidence of diabetes. For the meta-analysis, we searched MEDLINE and EMBASE for observational studies published through December 2018 that evaluated spousal concordance for diabetes.

RESULTS:

During a median follow-up of 22 years, 2512 incident cases of diabetes were recorded. In models with adjustment for general adiposity, spousal cardiometabolic factors and other diabetes risk factors, adults who had a spouse with diabetes had elevated risk for incident diabetes compared to those without a spouse diagnosed with diabetes (HR =1.20, 95% confidence interval: 1.02–1.41). This association did not differ by sex or race. Summarized estimates from the 17 studies (489,798 participants from 9 countries) included in the meta-analysis showed a positive association between spousal diabetes status and the development of diabetes (Pooled odds ratio =1.88, 95%CI: 1.52–2.33).

CONCLUSIONS:

Results from this large prospective biracial cohort and meta-analysis provides evidence that spouses of persons with diabetes are a high-risk group for diabetes.

Keywords: Concordance, epidemiology, longitudinal, obesity, spouse, type 2 diabetes

INTRODUCTION

Type 2 diabetes continues to be a critical public health challenge worldwide. Globally, more than 425 million adults over the age of 20 years are estimated to have diabetes [1] and this number is estimated to increase in the face of the current obesity trends.

A family history of diabetes is an important component in diabetes risk assessment. Familial aggregation studies estimate the heritability of diabetes to be approximately 25% [2,3]. However, genetic variants (>65) currently identified by genome-wide association studies to be associated with diabetes explain less than 10% of the disease’s heritability [4], and they do not fully explain the rapid rise in the prevalence of diabetes. While genetic factors are important in the etiology of diabetes, environmental and behavioral/lifestyle factors such as obesity, diet, and physical activity play important roles in the expression of genetic risk on the incidence of diabetes.

Spouses are usually genetically unrelated but may share some common lifestyle and environmental factors. Accordingly, some previous studies have reported spousal concordance for high glucose levels [5,6] while others suggest that spouses of persons with diabetes have a greater risk of diabetes compared to spouses of persons without diabetes [7–11]. However, a meta-analysis of 5 cross-sectional studies found no significant spousal concordance for diabetes after accounting for body mass index (BMI) [12]. To date, the prospective investigations of spousal concordance of diabetes are sparse with the results being equivocal [7,13–15]. Prior prospective studies have largely failed to account for other risk factors for diabetes such as smoking, diet and physical activity in addition to other potential mediators like lipids and blood pressure.

Therefore, we aimed to assess, prospectively, among a biracial cohort of white and black men and women enrolled in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study whether spouses of individuals with diabetes are at a higher risk of developing diabetes than spouses of individuals without diabetes, independent of other diabetes risk factors and common shared lifestyle factors. We hypothesized that having a spouse with diabetes would be positively associated with the incidence of diabetes independent of excess adiposity. To put our findings in context and provide a higher level of evidence, we also pooled our results with prior published studies in a meta-analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

The ARIC study is a multi-center prospective cohort study of 15,792 men and women aged 45–64 who were recruited and examined in 1987–1989 from four US communities in North Carolina, Mississippi, Minnesota, and Maryland to identify risk factors for atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. To date, 5 follow-up examinations have been conducted in 1990–92, 1993–95, 1996–98, 2011–13 and 2016–17. Additionally, participants have been contacted by phone annually or semi-annually since baseline with more than 90% of the surviving cohort continuing to respond. All participants provided written informed consent with data collection protocols approved by the Institutional Review Boards of each participating ARIC study center (the Universities of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, Mississippi, Minnesota, and John Hopkins University) and the coordinating center (North Carolina-Chapel Hill), and the research was conducted in accordance with the principles described in the Declaration of Helsinki. The present analysis was restricted to only married individuals at baseline. Spousal pairs were identified by asking participants to report their marital status (i.e., married, never married, divorced, separated, or widowed) prior to enrollment in ARIC and, if applicable, to identify their spouse. No same-sex pairs were included. Details of the study design and methods for ARIC [16] as well as procedures used to identify spousal pairs [17,18] are described elsewhere.

Exposure, risk factors and outcome

At baseline and each ARIC follow‐up visit, standardized protocols were used to collect information from participants. Age, sex, race, parental history of diabetes, education, smoking status, alcohol intake, and medications were all self-reported at baseline. Blood pressure was measured three times using a random-zero sphygmomanometer with participants seated and after five minutes of rest. The average of the second and third consecutive measurements was used for analysis. BMI was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared. Waist circumference was measured at the level of the umbilicus. Sports-related physical activity was assessed by the Baecke questionnaire [19]. Total daily caloric intake was estimated using a modified 61-question Willet food frequency questionnaire [20]. Blood samples were obtained at every visit and participants were asked to fast for 12 hours before the blood draw. Plasma total cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol were determined by enzymatic methods. Glucose was measured using the hexokinase-glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase method and insulin was measured by radioimmunoassay in serum. The exposure for this analysis is having a spouse diagnosed with diabetes. Ascertainment of diabetes status was conducted at each visit and follow-up phone interviews. Diabetes was defined as a fasting blood glucose level ≥7.0 mmol/L, non–fasting blood glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, self-reported physician diagnosis of diabetes, or reported current use of antidiabetic medication.

Statistical analysis

From 8976 married participants at baseline who reported either black or white race, we excluded all participants who had diabetes at baseline, resulting in an analytic sample of 8077 participants. Characteristics of the study participants were described using means (standard deviations) and proportions stratified by sex. We used complementary log-log regression models that accounted for interval censoring to estimate the hazard rate ratio (HR) for the association between baseline spousal diabetes status and the incidence of diabetes occurring from baseline to December 31, 2016. Model 1 adjusted for demographic factors. Model 2 further adjusted for behavior and lifestyle factors. Model 3 further adjusted for parental history of diabetes and cardiometabolic factors such as HDL and total cholesterol, systolic blood pressure and body mass index, which were all modeled as time-varying covariates. Model 4 further adjusted for the spouse’s cardiometabolic factors. To determine whether the magnitude of association of a husband’s diabetes status on the wife’s risk for developing diabetes is the same as the magnitude of association of a wife’s diabetes status on the husband’s risk for diabetes, a two-way interaction between spousal diabetes status and sex was conducted. Other formal tests for multiplicative interactions of age, race, BMI, parental history of diabetes, systolic blood pressure, total caloric intake and total cholesterol with spousal diabetes status in relation to incident diabetes were assessed. All these interaction tests were found not to be statistically significant (p>0.05). Two sensitivity analyses were performed. First, to explore the influence of the duration of shared norms, practices, and behaviors among couples on the risk of diabetes, an analysis was performed to assess the association of spousal diabetes with the incidence of diabetes among participants who reported being divorced, separated or widowed after baseline. Second, to evaluate the robustness of the reported estimates, incident diabetes was restricted to self-reported physician diagnosis of diabetes.

Meta-analysis

The meta-analysis was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (Supplementary material (SM) table S1) [21]. The protocol is registered at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO (ID: CRD42018106905). We performed a systematic literature search with no language restrictions in MEDLINE, and EMBASE, to evaluate all studies published (including abstracts) up until December 31, 2018 that assessed spousal diabetes as a risk factor for the development of diabetes in the non-diabetes spouse. The search strategy included a combination of text word and medical subject heading (SM table S2). Reference lists of retrieved articles were also reviewed and authors of relevant articles were contacted for missing data (100% response). Studies were included if 1) they had a cohort, case-control or cross-sectional design; 2) the main exposure of interest was spousal diabetes risk; 3) the endpoints of interest were prevalent or incident type-2 diabetes; 4) risk estimates were reported, namely odds ratios (OR), relative risks, incidence rate ratios or hazard rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Studies were excluded if they did not assess within spousal associations, reported estimates for a composite outcome of pre-diabetes and diabetes, or reported associations only with glucose levels. For each study, the maximally adjusted risk estimate was chosen whenever available. The methodological quality of the studies included in the meta-analysis were evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for case-control studies and cohort studies [22] and a modified version for evaluating cross-sectional studies [23] (SM table S3).

Data extraction and Analysis

The following information was recorded for each study using a standardized form: author, year of publication, location, study design, sample size, number of events, definition of diabetes status and confounders adjusted in models. Odds ratio was the summary effect estimate of choice. When the incidence of an event is low, the odds ratio has been shown to be a good approximation for the incidence rate ratio or hazard rate ratio [24]. Therefore, rate ratios were treated as ORs without further adjustment as the incidence of diabetes in these study populations was low (≤ 10%). When studies did not report effect estimates but provided raw data to do so, odds ratios and exact CIs were estimated using conditional maximum-likelihood methods [25]. Whenever unavailable for a study, overall estimates were calculated by combining sex-specific estimates. Significant between-study heterogeneity was anticipated based on known regional differences in both the burden and predisposing environmental factors for diabetes as well as the varying study designs used. Therefore, summary estimates across all studies were calculated using DerSimonian and Laird’s random-effects method, weighting individual study risk estimates by the inverse of their variance [26]. Statistical heterogeneity among studies was assessed using Cochran’s Q test and I2 with a p value of < 0.10 used to reject the null hypothesis that estimates from the various studies are homogenous. To determine the size and clinical relevance of the observed heterogeneity [27], the underlying between-study variance, τ 2 was also reported. Possible sources of heterogeneity were also explored using Galbraith plot [28] and subgroup analysis. Meta-regression analysis was subsequently used to determine whether study-level covariates explained some of the observed between-study heterogeneity. Publication bias was assessed by visual interpretation of funnel plots, Begg’s adjusted rank correlation [29], Egger’ regression asymmetry tests [30] and weighed fail-safe N [31]. To evaluate the stability of the results of the summary estimate, several sensitivity analyses were performed including sequentially removing one study at a time to evaluate the influence of each study on the pooled estimate. Cumulative meta-analysis was also performed by sorting the studies based on publication year to assess the influence of accumulation of data over time on the pooled OR as well as sorting studies from the most precise to least precise based on sample size.

RESULTS

Prospective cohort analysis

At baseline, a total of 771 ARIC participants had spouses who were diagnosed with diabetes. Having a spouse with diabetes showed positive associations with age, black race, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, insulin levels, BMI and waist circumference, and negative associations with education, alcohol intake and sports-related physical activity scores (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 8077 married participants without diabetes by sex, ARIC study 1987–1989

| Men | P value | Women | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spouses of DM women (n = 326) |

Spouses of non- DM women (n = 3653) |

Spouses of DM men (n = 445) |

Spouses of non DM men (n = 3653) |

|||

| Age, years | 56.9 (0.3) | 55.2 (0.1) | 0.001 | 54.2 (0.3) | 52.8 (0.1) | 0.001 |

| Race, black (%) | 27.2 | 13.1 | 0.001 | 23.8 | 13.0 | 0.001 |

| Education (%) | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||||

| < high school | 34.8 | 19.5 | 20.9 | 14.5 | ||

| High school | 39.1 | 37.5 | 50.9 | 49.1 | ||

| > High school | 26.2 | 43.0 | 28.2 | 36.4 | ||

| Smoking status, current (%) | 28.8 | 24.7 | 0.109 | 20.9 | 21.5 | 0.807 |

| Alcohol intake (g/day) | 57.7 (7.9) | 69.2 (2) | 0.099 | 20.0 (2.6) | 22.4 (0/8) | 0.330 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 126 (1.0) | 121 (0.3) | 0.001 | 121 (0.9) | 117 (0.3) | 0.001 |

| Hypertension meds (%) | 26.1 | 24.3 | 0.460 | 33.3 | 24.6 | 0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.0 (0.3) | 27.2 (0.1) | 0.001 | 28.0 (0.3) | 26.5 (0.1) | 0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 100.5 (0.7) | 98.7 (0.2) | 0.003 | 96.0 (0.7) | 91.7 (0.2) | 0.001 |

| Total caloric intake (kcal/day) | 1822 (44) | 1764 (12) | 0.159 | 1559 (31) | 1499 (10) | 0.040 |

| Sports-related physical activity | 2.5 (0) | 2.6 (0) | 0.001 | 2.3 (0) | 2.4 (0) | 0.008 |

| Total-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.50 (0.06) | 5.48 (0.02) | 0.759 | 5.67 (0.05) | 5.58 (0.02) | 0.117 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.20 (0.02) | 1.18 (0.01) | 0.278 | 1.56 (0.02) | 1.57 (0.01) | 0.550 |

| Lipid-lowering meds (%) | 2.8 | 3.2 | 0.868 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 0.742 |

| Insulin (pmol/L) | 85.3 (3.3) | 79.6 (0.9) | 0.084 | 79.9 (2.8) | 70.1 (0.9) | 0.001 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 5.64 (0.03) | 5.60 (0.01) | 0.153 | 5.42 (0.02) | 5.36 (0.01) | 0.006 |

| Family history of diabetes (%) | 23.9 | 21.1 | 0.259 | 25.4 | 22.9 | 0.259 |

Values are means (standard deviations) or percentages. DM: diabetes mellitus, HDL: high-density lipoprotein

During a median follow-up of 22 years, 2512 incident cases of diabetes were recorded with 2239 of the cases defined based on blood glucose levels or medication while 668 of these were based on blood glucose levels alone. Overall, participants with a spouse diagnosed with diabetes were more likely to develop diabetes compared to adults whose spouse did not have diabetes at baseline (HR=1.48, CI: 1.30–1.67) (Table 2). The association was slightly higher among husbands whose wife had diabetes (HR= 1.63, 95%CI: 1.36–1.96) compared to wives whose husband had diabetes (HR= 1.44, 95%CI: 1.21–1.71). However, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.62). The association was attenuated but remained significant after adjustment for demographic factors (model 2) or behavior and lifestyle factors, parental history of diabetes and cardiometabolic factors (model 3). After further adjustment for a participant’s spouse risk factors for diabetes, namely smoking status, systolic blood pressure, alcohol intake, total daily caloric intake, HDL and total cholesterol, the HR was 1.20 (95%CI: 1.02–1.41) for incident diabetes among adults with a spouse diagnosed with diabetes. No appreciable difference was observed when additional adjustment for an individual’s own waist circumference was made.

Table 2.

Hazard rate ratios (95% confidence intervals) for the association of spousal diabetes status with the incidence of diabetes, ARIC study 1987–2016

| Model | Hazard rate ratios | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | 1.48 | 1.30–1.67 |

| Model 1 | 1.34 | 1.17–1.52 |

| Model 2 | 1.33 | 1.17–1.51 |

| Model 3 | 1.27 | 1.08–1.49 |

| Model 4 | 1.20 | 1.02–1.41 |

Model 1 adjusted for demographic factors: age, race, sex, ARIC center and education.

Model 2 further adjusted for behavior and lifestyle factors namely total daily caloric intake, smoking status, alcohol intake and physical activity.

Model 3 further adjusted for parental history of diabetes and cardiometabolic factors: body mass index, HDL and total cholesterol, and systolic blood pressure which were all modeled as time-varying covariates.

Model 4 further adjusted for a person’s spouse risk factors (baseline smoking status, systolic blood pressure, alcohol intake, total daily caloric intake, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and total cholesterol).

In sensitivity analyses, the association of spousal diabetes status and incident diabetes was similar when incident diabetes was restricted to either cases of self- reported physician diagnosis of diabetes (HR= 1.17: 95%CI: 0.97–1.40), cases of diabetes based on blood glucose levels or medication use (HR= 1.15: 95%CI: 0.96–1.38)) or cases of diabetes based on blood glucose only (HR=1.00:95%CI:0.68–1.46). The there was no appreciable difference in the risk for diabetes between participants who remained married during follow-up (n=5745) and those who reported being divorced, separated or widowed during follow-up (n=2332) (p = 0.568).

Meta‐Analysis

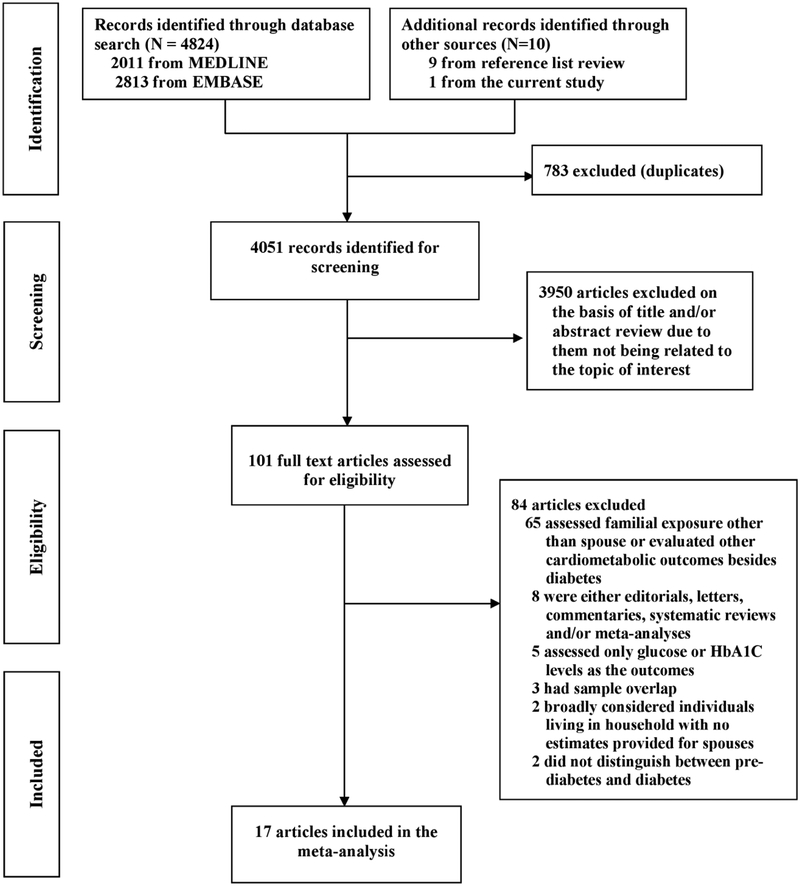

Sixteen studies [9–11,8,32–35,6,13,36,37,7,14,15,38] together with the current study from the ARIC cohort met the inclusion criteria for the meta-analysis (Fig. 1). Characteristics of the included studies which comprised of 489,798 participants from 9 countries are presented in the ESM table S4. Of these, 3 were case-control studies, 5 were cohort studies and 9 were cross-sectional studies. For the cohort studies, the average follow-up ranged from 3 to 25 years.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study selection for the meta‐analysis

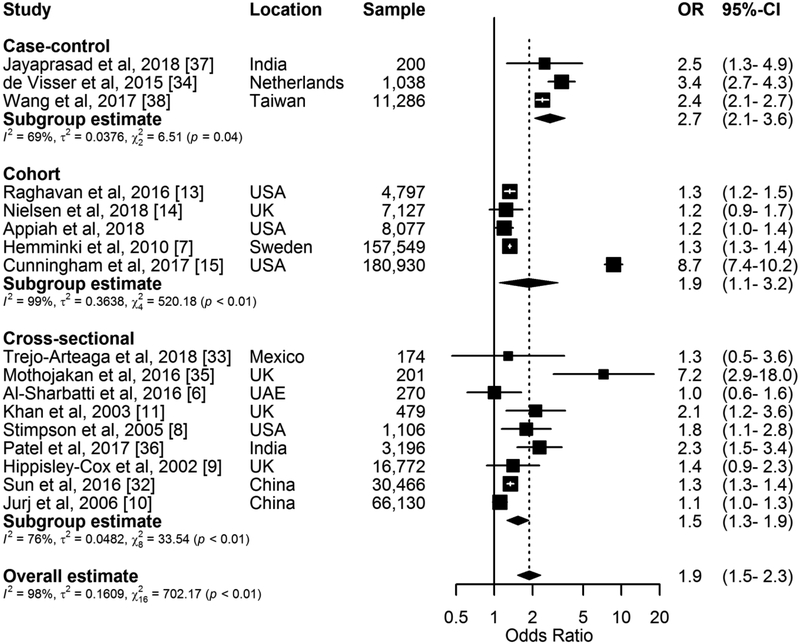

In our pooled analysis, having a spouse with diabetes was significantly associated with developing diabetes (Pooled OR=1.88, 1.52–2.33, I2 = 97.7%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). In subgroup analyses, the association was observed to be larger in case-control studies than cohort and cross-sectional studies (Table 3). The pooled estimates did not vary by region, sex, sample size, adjustment for BMI, diabetes diagnostic criteria and study quality. The funnel plot appeared largely asymmetrical (SM Fig. S1) with empirical evidence supporting this observation (Begg test p=0.187, Egger’s bias=3.08, p=0.121). Furthermore, the number of unpublished studies of null effect that would reduce the results of this analysis to statistical non-significance was estimated by fail-safe N to be 223, confirming that these results are robust to publication bias. The Galbraith plot showed that 7 of the 17 studies fell outside of the ± 2 standard deviations parallel lines thus indicating potential presence of significant heterogeneity (SM Fig. S2). When these 7 studies were excluded in sensitivity analysis, the observed heterogeneity was reduced considerably with I2 changing from 97.7% to 18.1%. It is not entirely clear what these outlier studies have in common that accounted for substantial heterogeneity beyond sampling error in the analysis. However, six of the seven studies made no adjustment for BMI with the other having more than a fifth of participants (~39,000) with missing information for BMI. Although the overall effect estimate for the development of diabetes after a spouse’s diagnosis was attenuated with the exclusion of these seven studies, it remained statistically significant (Pooled OR=1.33, 1.24–1.42) (SM Fig. S3). In meta-regression analysis, there was no influence on the pooled estimate by any study level characteristics. In analysis which sequentially omitted one study at a time and recalculated the pooled ORs for the remainder of the studies, it was observed that no individual study influenced the pooled estimate substantially; however, the omission of the study by Cunningham et al[15] resulted in a 17% reduced change in the pooled estimate (SM Fig. S4). The cumulative meta-analysis showed that the association of spousal diabetes status with the development of diabetes remained significant over time but tended to fluctuate with the accumulation of studies (SM Fig. S5). Further analysis sorting the studies in the sequence of largest to smallest sample size showed that the confidence interval for the pooled estimate became increasingly narrower with the addition of smaller studies (SM Fig. S6).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of odds ratios and 95% CIs for the association of spousal diabetes status with the development of diabetes in the non-diabetes spouse. Appiah et al is the current study

Table 3.

Pooled odds ratios (95% CI) for stratified meta-analyses of the association of spousal diabetes status with the development of diabetes in the spouse without diabetes

| Characteristics | Studies, N | Pooled OR (5%CI) | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.692 | ||

| Male | 5 | 1.37 (1.26–1.49) | |

| Female | 5 | 1.34 (1.30–1.38) | |

| Region | 0.602 | ||

| Asia | 6 | 1.61 (1.18–2.19) | |

| Europe | 6 | 2.03 (1.32–3.14) | |

| North America | 5 | 2.04 (0.84–4.94) | |

| Study design | 0.004 | ||

| Cross-sectional | 9 | 1.54 (1.25–1.88) | |

| Case-control | 3 | 2.74 (2.07–3.62) | |

| Cohort | 5 | 1.89 (1.09–3.28) | |

| Adjustment for BMI | 0.854 | ||

| No | 10 | 1.83 (1.40–2.39) | |

| Yes | 7 | 1.93 (1.16–3.20) | |

| Sample size | 0.767 | ||

| <1,000 | 5 | 2.10 (1.13–3.87) | |

| 1,000–9,999 | 6 | 1.71 (1.25–2.34) | |

| > 10,000 | 6 | 1.97 (1.37–2.85) | |

| Adjustment for confounders | 0.728 | ||

| Unadjusted | 4 | 2.09 (1.08–4.06) | |

| Adjusted | 13 | 1.84 (1.46–2.33) | |

| Diabetes diagnosis | 0.779 | ||

| Self-reported only | 3 | 2.12 (0.97–4.63) | |

| Self-report and blood glucose or medication | 14 | 1.89 (1.49–2.40) | |

| Quality score | 0.798 | ||

| > 7 | 8 | 1.95 (1.35–2.81) | |

| ≤ 7 | 9 | 1.84 (1.36–2.47) |

Between group comparison p value

BMI: Body mass index; CI: Confidence interval; N: Number; OR: Odds ratio

DISCUSSION

Results from this large prospective observational cohort of white and black men and women enrolled in the ARIC study with a median follow-up of 22 years and extensive assessment of diabetes risk factors showed an elevated risk of diabetes among adults who have a spouse with diabetes. This association did not differ by sex, race or diabetes case definition used. Although this positive association was attenuated by adjustment for shared demographic, social, behavioral, dietary and time-varying physiological and cardiometabolic factors, the observed association remained statistically significant. Similarly, the meta-analysis pooling ARIC data with 16 other observational studies also found a positive association of spousal diabetes status with the development of diabetes.

Previous reports for the association of spousal diabetes status with the development of diabetes have been inconsistent. A previous meta-analysis on spousal concordance for coronary risk factors reported a modest 16% elevated odds for diabetes concordance based on the review of 3 cross-sectional studies [39]. The meta-analysis of 5 cross-sectional studies by Leong et al [12] found no significant spousal concordance for diabetes after accounting for BMI. Obesity and diabetes share similar risk factors with the former influencing the occurrence of the latter. Among obese young adults, the lifetime risk of diabetes is estimated to be 57.0% and 54.6% for men and women with the risk increasing to 70.3% and 74.4% for very obese men and women [40]. Similar to other cohort studies [15,13], the present ARIC study showed an elevated risk for spousal concordance of diabetes after accounting for BMI. These findings of elevated risk of diabetes among spouses of persons with diabetes beyond obesity were corroborated by the current meta-analysis which included more than three times the studies evaluated in previous meta-analyses [12,39]. Taken together, these results suggest that shared adiposity may not completely explain the elevated risk of diabetes among married couples or partners.

The shared diabetes risk among married couples or partners observed in this and other studies may be largely explained by shared behavior/lifestyle and environmental factors. Among spouses who are genetically unrelated, host characteristics such as behavior/lifestyle factors and environmental exposures may play important roles in the development of diabetes.

Behavior/lifestyle and environmental factors may influence the phenotypic expression of diabetes either directly or indirectly by modulating the genetic susceptibility of one or both spouses [41,42]. Two theories have been widely publicized to explain the influence of behavior/lifestyle factors on shared diabetes risk among spouses. The first theory is non-random or assortative mating, which refers to the tendency of individuals to select spouses based on preference for similar phenotypic characteristics and normative attribute such as health norms, body composition, physical or sedentary activities and socioeconomic status [42,14,15]. The second theory alludes to spouses converging in their behaviors and lifestyle over the course of the marriage as a result of engaging in similar activities, practices, and habits [42,14,15]. In support of both theories, substantial spousal resemblance has been reported for blood pressure [43], glucose [5,6], lipids [9], physical activity [44,45], sedentary lifestyle [46], diet and eating patterns [47,48], dietary supplement use [49], sleeping patterns [50] and smoking [48]. For instance, having an obese spouse is reported to be associated with a 37% to a 2-fold risk of obesity in the other spouse [51,52].

Even though extensive adjustment for some of these shared spousal factors was made in the present ARIC study and other prospective studies [15,13], residual confounding of other unmeasured shared factors may explain the observed elevated risk for the development of diabetes among spouses of persons with diabetes. Other reports have shown that shared built environment characteristics such as homes, schools, workplaces, highways, urbanization, neighborhood walkability, green space, pollution and access to amenities such as parks, fresh fruits/vegetables and preventive health services all influence the risk of developing diabetes [53,54,42]. This suggests that sharing built environmental exposures may also impact couples’ risk of diabetes either directly, for example by means of pollution, or indirectly through influencing behavioral or lifestyle similarities among married couples. All in all, it is also worth noting that these shared spousal upstream and downstream determinants of diabetes may not always result in the development of diabetes among one or both spouses due to differences in underlying physiological and genetic predispositions for diabetes [14]. Explaining how upstream environmental factors influence spousal similarities and differences should be an important focus of future research. Furthermore, investigations of the additional role of built environment on incident diabetes risk beyond shared spousal behavior/lifestyle characteristics and predisposing host genetic susceptibility will provide valuable information that may provide a window of opportunity to intervene on the shared diabetes risk among spouses. Other shared characteristics may also contribute to the development of diabetes among spouses. Spouses under the same household socioeconomic condition often share the same financial resources which may contribute to the degree of resemblance among spouses for health related-activities, cardiometabolic conditions and psychosocial stressors as well as access to health care [45,38]. In most countries, access to health care is largely influenced by health insurance coverage, and inadequate or lack of health insurance coverage have been reported to play a crucial role in the uptake of preventive services for diabetes [55].

It is also possible that genetic predisposition for diabetes among one or both married couple could contribute to spousal concordance for diabetes. Several studies have shown that inherited genetic susceptibility is an important risk factor for diabetes among related individuals. For instance, previous familial aggregation studies have reported the heritability of diabetes to be approximately 25% [2, 3]. However, with the prevalence of consanguineous marriages being low in locations in which majority of the studies for the current meta-analysis were conducted [56], it is unlikely that host genetic susceptibility alone may explain, to a greater extent, the spousal concordance for diabetes observed in the current analysis. In support of this, Raghavan et al [13] observed in the Framingham Offspring Study that the elevated risk for diabetes in adults who have a spouse with diabetes remained even after accounting for spouse’s diabetes additive genetic risk score and parental history of diabetes.

The findings of this study have important clinical and public health implications. A number of clinical evaluation guidelines and risk assessment tools for diabetes focus on factors such as age, race, body weight, BMI, smoking, and family history to identify high risk groups for interventions [57,58]. However, several of these factors are known to cluster in households even among persons that are genetically unrelated. With the prevalence of diabetes rapidly increasing worldwide and 46% (174.8 million) of all diabetes cases in adults estimated to be undiagnosed [59], spousal concordance or history of spousal diabetes status can be leveraged to bolster effects to identify high risk individuals or undiagnosed diabetes cases for couple-based lifestyle preventive services, counseling, or care-delivery interventions. Such interventions have been shown to yield clinically significant results even when only one spouse receives the intervention. For example, having a spouse, relative or friend with diabetes is known to elicit lifestyle changes towards good health and in some instances motivate individuals without diabetes to seek screening and preventive care [60]. Thus, if one spouse adapts healthy lifestyle behaviors, the other spouse is usually more likely to do so as well [61,62].

There are some limitations to this study that must be considered when interpreting our results. First, only heterosexual legally married couples in the ARIC cohort were included in the study. Therefore, the findings may or may not be generalizable to cohabiting but not married couples or to same-sex couples. Second, we were unable to determine the influence of the length of marriage or cohabitation, quality of marriage or the duration of spousal diabetes status, on the reported association as such information were not measured. However, some previous studies observed no significant influence of duration of marriage/cohabitation on spousal concordance for diabetes [10,32,6,8]. In the present study there was no difference in estimates between couples who remained married during follow-up and those who were divorced, separated or widowed. Third, we did not measure some important confounders such as the built environment, access to care and diet quality, therefore we could not account for their influence on the results. Fourth, although there were no appreciable differences in estimates with regard to the diabetes case definition used, the null association found for spousal diabetes status with incident diabetes defined by fasting glucose may point to the possibility of detection bias. It is also possible that this observation may be due to the limited statistical power. Alternatively, Khan et al (11) reported higher odds of diabetes defined by fasting glucose or oral glucose tolerance test among persons with a spouse diagnosed with diabetes. Finally, the pooled OR from the meta-analysis may overestimate the risk of spousal diabetes status with the development of diabetes since some of the included studies reported ORs when the incidence of diabetes in their study population was > 10%.

In summary, the data from this large prospective biracial cohort and summarized estimate from the meta-analysis of 17 studies provides evidence that having a spouse with diabetes elevates an individual’s risk of developing diabetes even beyond the effect of the individual’s own risk factors for diabetes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract numbers (HHSN268201700001I, HHSN268201700002I, HHSN268201700003I, HHSN268201700005I, HHSN268201700004I). The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions. Dr. Appiah was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute training grant T32HL007779. Dr. Selvin was supported by NIH/NIDDK grants K24DK106414 and R01DK089174. The study sponsor was not involved in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The data collection protocols approved by the Institutional Review Boards of each participating ARIC study center (the Universities of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, Mississippi, Minnesota, and John Hopkins University) and the coordinating center (North Carolina-Chapel Hill), and the research was conducted in accordance with the principles described in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

All participants provided written informed consent for the ARIC study

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Detailed procedures for accessing ARIC data can be found at https://www2.cscc.unc.edu/aric/pubs-policies-and-forms-pg. Most ARIC data can be also obtained from BioLINCC, a repository maintained by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute at https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/. For the meta-analysis, no datasets were generated.

REFERENCES

- 1.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas — 8th Edition. http://www.diabetesatlas.org. [PubMed]

- 2.Almgren P, Lehtovirta M, Isomaa B, Sarelin L, Taskinen MR, Lyssenko V, Tuomi T, Groop L, Botnia Study G (2011) Heritability and familiality of type 2 diabetes and related quantitative traits in the Botnia Study. Diabetologia 54 (11):2811–2819. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2267-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poulsen P, Kyvik KO, Vaag A, Beck-Nielsen H (1999) Heritability of type II (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus and abnormal glucose tolerance--a population-based twin study. Diabetologia 42 (2):139–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwak SH, Park KS (2013) Genetics of type 2 diabetes and potential clinical implications. Arch Pharm Res 36 (2):167–177. doi: 10.1007/s12272-013-0021-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrett-Connor E, Suarez L (1982) Spouse concordance for fasting plasma glucose in non-diabetics. American journal of epidemiology 116 (3):475–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Sharbatti SS, Abed YI, Al-Heety LM, Basha SA (2016) Spousal Concordance of Diabetes Mellitus among Women in Ajman, United Arab Emirates. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 16 (2):e197–202. doi: 10.18295/squmj.2016.16.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hemminki K, Li X, Sundquist K, Sundquist J (2010) Familial risks for type 2 diabetes in Sweden. Diabetes care 33 (2):293–297. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stimpson JP, Peek MK (2005) Concordance of chronic conditions in older Mexican American couples. Prev Chronic Dis 2 (3):A07. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Pringle M, Crown N, Hammersley V (2002) Married couples’ risk of same disease: cross sectional study. BMJ 325 (7365):636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jurj AL, Wen W, Li HL, Zheng W, Yang G, Xiang YB, Gao YT, Shu XO (2006) Spousal correlations for lifestyle factors and selected diseases in Chinese couples. Annals of epidemiology 16 (4):285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.07.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan A, Lasker SS, Chowdhury TA (2003) Are spouses of patients with type 2 diabetes at increased risk of developing diabetes? Diabetes care 26 (3):710–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leong A, Rahme E, Dasgupta K (2014) Spousal diabetes as a diabetes risk factor: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 12:12. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raghavan S, Pachucki MC, Chang Y, Porneala B, Fox CS, Dupuis J, Meigs JB (2016) Incident Type 2 Diabetes Risk is Influenced by Obesity and Diabetes in Social Contacts: a Social Network Analysis. Journal of general internal medicine 31 (10):1127–1133. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3723-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nielsen J, Hulman A, Witte DR (2018) Spousal cardiometabolic risk factors and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a prospective analysis from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Diabetologia. doi: 10.1007/s00125-018-4587-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cunningham SA, Adams SR, Schmittdiel JA, Ali MK (2017) Incidence of diabetes after a partner’s diagnosis. Prev Med 105:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.08.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The ARIC investigators (1989) The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives.. American journal of epidemiology 129 (4):687–702 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McAdams DeMarco M, Coresh J, Woodward M, Butler KR, Kao WH, Mosley TH Jr., Hindin M, Anderson CA (2011) Hypertension status, treatment, and control among spousal pairs in a middle-aged adult cohort. American journal of epidemiology 174 (7):790–796. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cobb LK, Godino JG, Selvin E, Kucharska-Newton A, Coresh J, Koton S (2015) Spousal Influence on Physical Activity in Middle-Aged and Older Adults: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. American journal of epidemiology. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baecke JA, Burema J, Frijters JE (1982) A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. The American journal of clinical nutrition 36 (5):936–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willett WC, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Bain C, Witschi J, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE (1985) Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. American journal of epidemiology 122 (1):51–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Annals of internal medicine 151 (4):W65–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V L M, Tugwell P The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed July, 24, 2018

- 23.Herzog R, Alvarez-Pasquin MJ, Diaz C, Del Barrio JL, Estrada JM, Gil A (2013) Are healthcare workers’ intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? A systematic review. BMC Public Health 13:154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Symons MJ, Moore DT (2002) Hazard rate ratio and prospective epidemiological studies. Journal of clinical epidemiology 55 (9):893–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin D, Austin H (1991) An efficient program for computing conditional maximum likelihood estimates and exact confidence limits for a common odds ratio. Epidemiology 2 (5):359–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DerSimonian R, Laird N (1986) Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 7 (3):177–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rucker G, Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Schumacher M (2008) Undue reliance on I(2) in assessing heterogeneity may mislead. BMC medical research methodology 8:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galbraith RF (1988) A note on graphical presentation of estimated odds ratios from several clinical trials. Statistics in medicine 7 (8):889–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Begg CB, Berlin JA (1988) Publication Bias - a Problem in Interpreting Medical Data. J Roy Stat Soc a Sta 151:419–463. doi:Doi 10.2307/2982993 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315 (7109):629–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenberg MS (2005) The file-drawer problem revisited: a general weighted method for calculating fail-safe numbers in meta-analysis. Evolution 59 (2):464–468 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun J, Lu J, Wang W, Mu Y, Zhao J, Liu C, Chen L, Shi L, Li Q, Yang T, Yan L, Wan Q, Wu S, Liu Y, Wang G, Luo Z, Tang X, Chen G, Huo Y, Gao Z, Su Q, Ye Z, Wang Y, Qin G, Deng H, Yu X, Shen F, Chen L, Zhao L, Bi Y, Xu M, Xu Y, Dai M, Wang T, Zhang D, Lai S, Ning G, Group RS (2016) Prevalence of Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disorders in Spouses of Diabetic Individuals. American journal of epidemiology 184 (5):400–409. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trejo-Arteaga JM, Lopez-Carmona JM, Rodriguez-Moctezuma JR, Peralta-Pedrero ML, Escudero-Montero R, Gutierrez Escolano MF (2008) [Risk of glucose metabolism changes in spouses of Mexican patients with type 2 diabetes]. Med Clin (Barc) 131 (16):605–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Visser KL, Landman GW, Kleefstra N, Meyboom-de Jong B, de Visser W, te Meerman GJ, Bilo HJ (2015) Familial Aggregation between the 14th and 21st Century and Type 2 Diabetes Risk in an Isolated Dutch Population. PloS one 10 (7):e0132549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mothojakan NB, Hussain S, McCafferty K, Yaqoob MM, Chowdhury TA (2016) Comparison of spousal and family history of diabetes, hypertension and renal disease between haemodialysis patients with diabetes and haemodialysis patients without diabetes. Diabetic Medicine 33 (Suppl. 1):159(Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patel SA, Dhillon PK, Kondal D, Jeemon P, Kahol K, Manimunda SP, Purty AJ, Deshpande A, Negi PC, Ladhani S, Toteja GS, Patel V, Prabhakaran D (2017) Chronic disease concordance within Indian households: A cross-sectional study. PLoS medicine 14 (9):e1002395. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jayaprasad N, Bhatkule PR, Narlawar UW (2018) Risk Factors For Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Nagpur: A Case Control Study. International Journal of Scientific Research 7 (2):53–55 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang JY, Liu CS, Lung CH, Yang YT, Lin MH (2017) Investigating spousal concordance of diabetes through statistical analysis and data mining. PloS one 12 (8):e0183413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Castelnuovo A, Quacquaruccio G, Donati MB, de Gaetano G, Iacoviello L (2009) Spousal concordance for major coronary risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of epidemiology 169 (1):1–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Narayan KM, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Gregg EW, Williamson DF (2007) Effect of BMI on lifetime risk for diabetes in the U.S. Diabetes care 30 (6):1562–1566. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murea M, Ma L, Freedman BI (2012) Genetic and environmental factors associated with type 2 diabetes and diabetic vascular complications. Rev Diabet Stud 9 (1):6–22. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2012.9.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mackenbach JD, den Braver NR, Beulens JWJ (2018) Spouses, social networks and other upstream determinants of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 61 (7):1517–1521. doi: 10.1007/s00125-018-4607-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Z, Ji W, Song Y, Li J, Shen Y, Zheng H, Ding Y (2017) Spousal concordance for hypertension: A meta-analysis of observational studies. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 19 (11):1088–1095. doi: 10.1111/jch.13084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cobb LK, Godino JG, Selvin E, Kucharska-Newton A, Coresh J, Koton S (2016) Spousal Influence on Physical Activity in Middle-Aged and Older Adults: The ARIC Study. American journal of epidemiology 183 (5):444–451. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen HJ, Liu Y, Wang Y (2014) Socioeconomic and demographic factors for spousal resemblance in obesity status and habitual physical activity in the United States. J Obes 2014:703215. doi: 10.1155/2014/703215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wood L, Jago R, Sebire SJ, Zahra J, Thompson JL (2015) Sedentary time among spouses: a cross-sectional study exploring associations in sedentary time and behaviour in parents of 5 and 6 year old children. BMC Res Notes 8:787. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1758-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pachucki MA, Jacques PF, Christakis NA (2011) Social network concordance in food choice among spouses, friends, and siblings. American journal of public health 101 (11):2170–2177. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schoeppe S, Vandelanotte C, Rebar AL, Hayman M, Duncan MJ, Alley SJ (2018) Do singles or couples live healthier lifestyles? Trends in Queensland between 2005–2014. PloS one 13 (2):e0192584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lentjes MA, Welch AA, Keogh RH, Luben RN, Khaw KT (2015) Opposites don’t attract: high spouse concordance for dietary supplement use in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer in Norfolk (EPIC-Norfolk) cohort study. Public Health Nutr 18 (6):1060–1066. doi: 10.1017/S1368980014001396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gunn HE, Buysse DJ, Hasler BP, Begley A, Troxel WM (2015) Sleep Concordance in Couples is Associated with Relationship Characteristics. Sleep 38 (6):933–939. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cobb LK, McAdams-DeMarco MA, Gudzune KA, Anderson CA, Demerath E, Woodward M, Selvin E, Coresh J (2016) Changes in Body Mass Index and Obesity Risk in Married Couples Over 25 Years: The ARIC Cohort Study. American journal of epidemiology 183 (5):435–443. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Christakis NA, Fowler JH (2007) The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. The New England journal of medicine 357 (4):370–379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa066082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.den Braver NR, Lakerveld J, Rutters F, Schoonmade LJ, Brug J, Beulens JWJ (2018) Built environmental characteristics and diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 16 (1):12. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0997-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pasala SK, Rao AA, Sridhar GR (2010) Built environment and diabetes. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries 30 (2):63–68. doi: 10.4103/0973-3930.62594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rabi DM, Edwards AL, Southern DA, Svenson LW, Sargious PM, Norton P, Larsen ET, Ghali WA (2006) Association of socio-economic status with diabetes prevalence and utilization of diabetes care services. BMC Health Serv Res 6:124. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hamamy H (2012) Consanguineous marriages : Preconception consultation in primary health care settings. J Community Genet 3 (3):185–192. doi: 10.1007/s12687-011-0072-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Summary of Revisions: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2018 (2018). Diabetes care 41 (Suppl 1):S4–S6. doi: 10.2337/dc18-Srev01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kengne AP, Masconi K, Mbanya VN, Lekoubou A, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Matsha TE (2014) Risk predictive modelling for diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 51 (1):1–12. doi: 10.3109/10408363.2013.853025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beagley J, Guariguata L, Weil C, Motala AA (2014) Global estimates of undiagnosed diabetes in adults. Diabetes research and clinical practice 103 (2):150–160. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mani N, Caiola E, Fortuna RJ (2011) The influence of social networks on patients’ attitudes toward type II diabetes. J Community Health 36 (5):728–732. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9366-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Falba TA, Sindelar JL (2008) Spousal concordance in health behavior change. Health Serv Res 43 (1 Pt 1):96–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00754.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schmittdiel JA, Cunningham SA, Adams SR, Nielsen J, Ali MK (2018) Influence of a New Diabetes Diagnosis on the Health Behaviors of the Patient’s Partner. Ann Fam Med 16 (4):290–295. doi: 10.1370/afm.2259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.