Abstract

The opioid crisis is a significant public health issue with more than 115 people dying from opioid overdose per day in the United States. The aim of the present study was to characterize the in vitro and in vivo pharmacological effects of 17-cyclopropylmethyl-3,14β-dihydroxy-4,5α-epoxy-6α-(indole-7-carboxamido)morphinan (NAN), a μ opioid receptor (MOR) ligand that may be a potential candidate for opioid use disorder treatment that produces less withdrawal signs than naltrexone. The efficacy of NAN was compared to varying efficacy ligands at the MOR, and determined at the δ opioid receptor (DOR) and κ opioid receptor (KOR). NAN was identified as a low efficacy partial agonist for G-protein activation at the MOR and DOR, but had relatively high efficacy at the KOR. In contrast to high efficacy MOR agonists, NAN did not induce MOR internalization, downregulation, or desensitization, but it antagonized agonist-induced MOR internalization and stimulation of intracellular Ca2+ release. Opioid withdrawal studies conducted using morphine-pelleted mice demonstrated that NAN precipitated significantly less withdrawal signs than naltrexone at similar doses. Furthermore, NAN failed to produce fentanyl-like discriminative stimulus effects in rats up to doses that produced dose- and time-dependent antagonism of fentanyl. Overall, these results provide converging lines of evidence that NAN functions mainly as a MOR antagonist and support further consideration of NAN as a candidate medication for opioid use disorder treatment.

Keywords: Opioid use disorder, naltrexamine, NAN, μ opioid receptors, opioid antagonist, mixed function ligand

Graphical Abstract

■ INTRODUCTION

Despite over 100 years of diligent law enforcement and legislative deterrents, opioid abuse still persists.1 Deaths due to prescription opioid overdoses have quadrupled since 2000. In addition, deaths due to heroin overdose have also more than quadrupled since 2010.2–5 The most current statistics show that more than 64,000 people died in 2016 due to drug overdose which was a 22% increase over the previous year (52,404 drug overdose deaths in 2015) and this is the largest annual jump ever recorded in the United States.5–7 One reason for this sharp rise is due to increase in the number of drug overdose deaths from fentanyl and fentanyl analogues (20,000 deaths in 2016) which has increased by over 540% within the last 3 years5–9 It is also important to note that the deaths due to drug overdose in 2016 were greater than the 37,461 deaths due to motor vehicles10 and more than the 38,000 who died due to gun-related deaths11 in 2016; indeed, drug overdose is the leading cause of death for Americans under 50.12 It is estimated that 115 people die per day due to only opioid overdose in the United States alone.7 Drug abuse not only has a negative impact on the health of Americans, but also has a huge economic burden costing over $600 billion annually.13

Current Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medications for opioid use disorder include opioid agonists (e.g., methadone or buprenorphine) and opioid antagonists (e.g., naltrexone). Methadone and buprenorphine (Figure 1A) are full and partial μ opioid receptor (MOR) agonists, respectively, and typically used as replacement therapies; however, approximately 40–60% of patients relapse while being maintained on these treatments.13 Undesirable effects of methadone and buprenorphine include abuse liability, respiratory depression (particularly methadone), immunosuppression, and hyperalgesia.13–17 Although the opioid antagonist naltrexone (NTX) (Figure 1A) lacks the undesirable effects associated with methadone and buprenorphine, NTX and another opioid antagonist approved for opioid overdose reversal, naloxone, have been shown to produce undesirable effects such as depression, dysphoria, suicide, pulmonary edema, cardiac arrhythmias, and precipitation of opioid withdrawal resulting in low compliance.18–21 Some of these undesirable effects could be attributed to the lack of selectivity for the MOR over other opioid receptors, such as δ opioid receptor (DOR) and κ opioid receptor (KOR).18–20 Thus, there is still imperative to improve upon the current opioid use disorder treatments.22–24

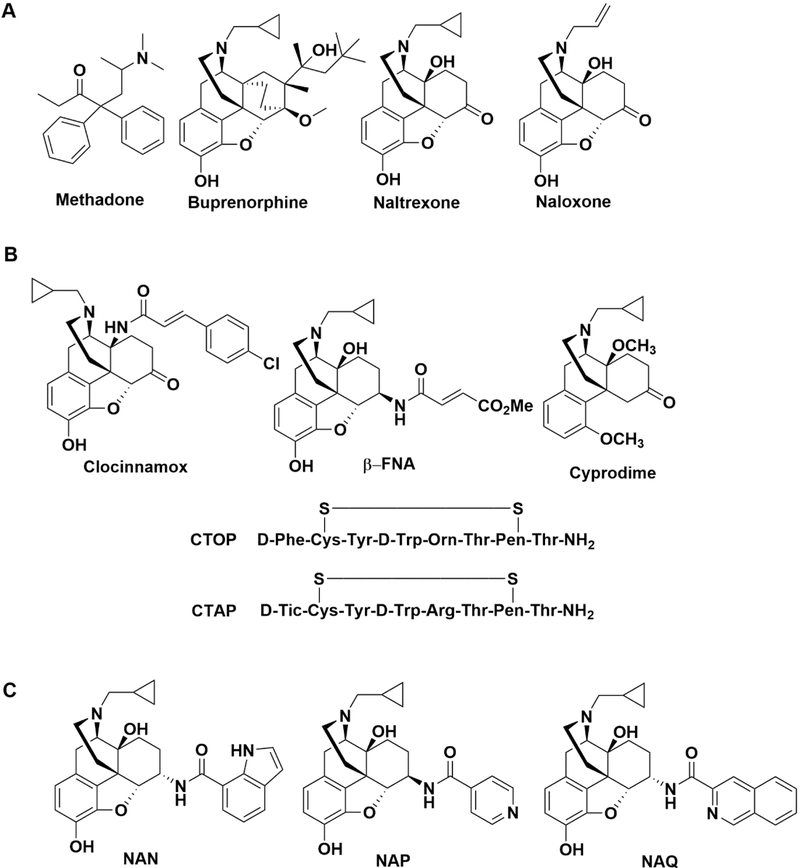

Figure 1.

Food and Drug Administration approved compounds for the treatment of opioid use disorder or opioid overdose (A) together with previously reported (B) and recently reported (C) MOR selective antagonists.

Opioids produce their effects by stimulating opioid receptors belonging to the class A rhodopsin-like G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily.25 There are four main types of opioid receptors which include MOR, KOR, DOR, and the nociceptin opioid peptide receptor (NOP).25,26 These receptors exist throughout the nervous system and peripheral organs such as heart, lungs, liver, gastrointestinal and reproductive tracts.27–29 Activation of the MOR mediates both the therapeutic effects of opioids such as analgesia and undesirable effects such as constipation and respiratory depression. MOR selective antagonists, such as clocinnamox β-FNA, CTAP, CTOP, and cyprodime, have been designed and synthesized (Figure 1B).30–34 However, these compounds either: (1) bind irreversibly to the MOR, (2) are conformationally constrained peptides with poor bioavailability and blood-brain barrier penetration, or (3) have lower affinity and moderate selectivity for the MOR compared to NTX.30–34 Thus, the development of a selective, potent, reversible nonpeptidic MOR antagonist remains highly desirable.

Our laboratory recently designed and synthesized 17-cyclopropylmethyl-3,14β-dihydroxy-4,5α-epoxy-6β-(4′-pyridylcarboxamido)morphinan (NAP) and 17-cyclopropyl-methyl-3,14β-dihydroxy-4,5α-epoxy-6α-(isoquinoline-3-carboxamido)morphinan (NAQ) which were shown to be antagonists selective for the MOR over the KOR and DOR (Figure 1C).35,36 Pharmacokinetic studies showed NAP acted peripherally while NAQ acted centrally.37. Further pharmacological studies showed that NAQ antagonizes or minimally activates MOR signaling without producing prototypical MOR agonist adaptations that contribute to tolerance, opioid dependence, or precipitation of cellular withdrawal in both in vitro and in vivo models.38–41

In addition to NAQ, we have recently identified 17-cyclopropylmethyl-3,14β-dihydroxy-4,5α-epoxy-6α-(indole-7-carboxamido)morphinan (NAN) as a potent MOR selective antagonist (Figure 1C).42 NAN was identified as a bitopic MOR ligand which may combine the advantages of orthosteric and allosteric ligands to produce less opioid tolerance, dependence, and greater MOR selectivity.42–44 The present studies report more extensive in vitro and in vivo pharmacological findings with NAN to support consideration of NAN as a candidate medication for opioid use disorder similar to NTX, however, with fewer undesirable effects than NTX.

■ RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

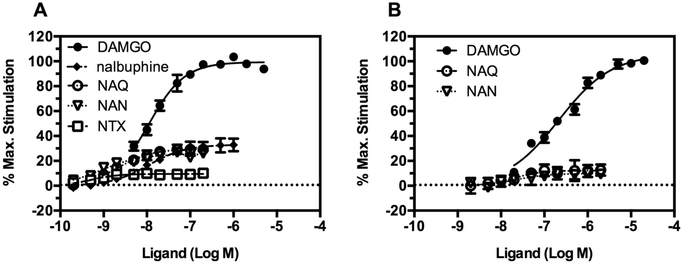

In Vitro Comparison of NAN with Varying Efficacy MOR Ligands in Both mMOR-CHO Cells and the Mouse Thalamus.

We previously showed that NAN was a low efficacy MOR partial agonist in the [35S]-GTPγS functional assay in monoclonal mouse MOR-expressing Chinese hamster ovary cells (mMOR-CHO) and almost completely antagonized the antinociceptive activity of morphine in mice in the warm water tail immersion assay.42 Herein, the efficacy and potency of NAN were compared to those of other MOR ligands with varying efficacies using the [35S]-GTPγS functional assay in mMOR-CHO cells (Figure 2A). The comparison was also conducted using membranes prepared from mouse thalamus, which expresses mostly the MOR, to avoid exclusive reliance on data from transfected cell lines in which the MOR is expressed at supraphysiological levels (Figure 2B). NTX and nalbuphine were not included in the mouse thalamus comparison because they were previously found to act as pure antagonists in the rat thalamus.45 The potency and efficacy values of the ligands obtained in both mMOR-CHO cells and mouse thalamus are shown in Table S1 (Supporting Information). Efficacy was determined as the percent stimulation relative to a maximally effective concentration of [d-Ala2, N-MePhe4, Gly-ol]-enkephalin (DAMGO), which is a full MOR agonist. The efficacy obtained for NAN (Emax (% DAMGO) = 25.46 ± 1.58) in mMOR-CHO cells was similar to the efficacy we previously reported (NAN_Emax (% DAMGO) = 19.11 ± 3.31).Figure 2A shows that NAN produced low MOR stimulation that was significantly less than DAMGO and similar to NAQ and nalbuphine, a clinically available low efficacy MOR partial agonist, in mMOR-CHO cells and mouse thalamus (Statistical comparison is shown in the Supporting Information, Figures S1 and S2).

Figure 2.

Concentration-effect curves of (A) DAMGO, NAQ, NAN, nalbuphine, and NTX in mMOR-CHO cells and (B) DAMGO, NAQ, and NAN in mouse thalamus. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM from at least four independent experiments. Net agonist stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding was 167.58 ± 9.01 and 221.13 ± 5.73 fmol/mg and the basal binding in the absence of the agonist was 32.54 ± 1.77 and 125.19 ± 4.13 fmol/mg in mMOR-CHO cells and thalamus, respectively.

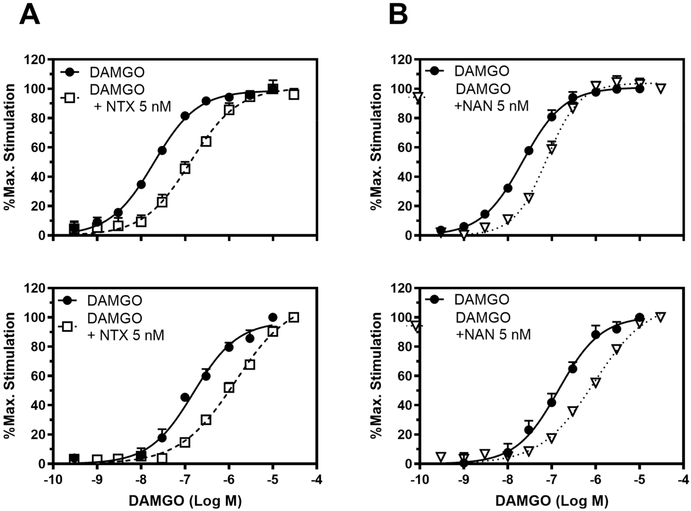

MOR Competitive Antagonism Studies with NAN.

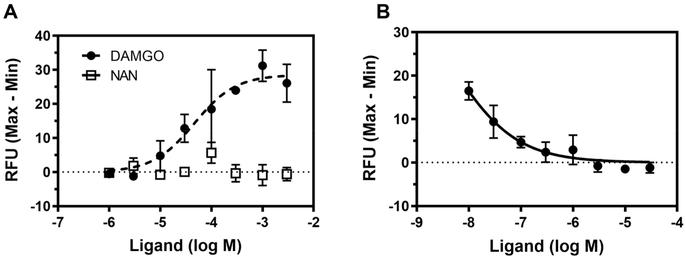

The [35S]-GTPγS functional assay was conducted to investigate the ability of NAN to produce a parallel rightward shift in the concentration effect curve of DAMGO. As observed in Figure 3, coincubation with 5 nM NAN produced a right shift in the DAMGO concentration-effect curve in both mMOR-CHO cells and thalamus similar to 5 nM NTX, a positive control. These results indicate that NAN is a MOR competitive antagonist and not a noncompetitive antagonist because NAN did not have any effect on the DAMGO Emax value (Figure 3). The calculated Ke values of NAN in mMOR-CHO cells and mouse thalamus were very similar, as shown in Table 1. However, the Ki value for NAN binding to MOR we previously reported (Ki (nM) = 0.23 ± 0.02)42 was lower than the Ke values obtained here. The reason for this discrepancy could be due to the different assay conditions used in determining the binding Ki and the functional Ke values. For instance, sodium and guanosine-5′-diphosphate (GDP) were used in the [35S]-GTPγS functional assay to determine the Ke, but not in determining the Ki in the receptor binding assays. It is well-known that sodium and guanine nucleotides reduce the affinity of full and partial MOR agonists (like NAN) but not of pure antagonists (like NTX), which can differentially affect agonist potency in functional assays.46–48 This could explain why the Ke of NTX was not significantly different from its Ki (NTX Ki (nM) = 0.33 ± 0.02) (Table 1).49 Thus, NAN acted as a high affinity MOR competitive antagonist in both mMOR-CHO cells and mouse thalamus. In addition, NAN concentration-dependently inhibited Ca2+ flux induced by DAMGO in the Ca2+ flux assay using Gαqi5 transfected hMOR-CHO cells (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Concentration effect curves of DAMGO in the absence and presence of 5 nM (A) NTX, (B) NAN in mMOR-CHO cells (upper panels) and mouse thalamus (lower panels). Data are represented as mean values ± SEM from at least four experiments. Net agonist stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding was 169.31 ± 5.85 and 279.53 ± 4.84 fmol/mg and the basal binding in the absence of the agonist was 33.07 ± 0.82 and 140.05 ± 3.94 fmol/mg in mMOR-CHO cells and thalamus, respectively. Bmax value obtained from the saturation binding assay for mMOR-CHO cells was 1.76 ± 0.50 pmol/mg.

Table 1.

Competitive Antagonism of DAMGO-Stimulated [35S]-GTPγS Binding by NTX and NAN in mMOR-CHO Cells and Mouse Thalamus

| EC50 (nM) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | DAMGO only | DAMGO + drug | EC50 shift | Ke (nM) | |

| mMOR-CHO cells | NTX | 19.29 ± 1.04 | 141.88 ± 13.72 | 7.43 ± 0.84 | 0.83 ± 0.12 |

| NAN | 23.56 ± 3.24 | 80.87 ± 11.69 | 3.45 ± 0.16 | 2.08 ± 0.14 | |

| mouse thalamus | NTX | 162.71 ± 26.09 | 1465.94 ± 333.70 | 10.58 ± 0.83 | 0.73 ± 0.16 |

| NAN | 179.86 ± 48.63 | 941.66 ± 78.02 | 8.30 ± 2.22 | 1.55 ± 0.56 | |

Figure 4.

Ca2+ flux assays in Gαqi5 transfected hMOR-CHO cells. (A) MOR full agonist DAMGO concentration-dependently increased intracellular Ca2+ level, whereas no apparent agonism was observed for NAN. (B) NAN antagonized DAMGO (500 nM)-induced intracellular Ca2+ increase. The EC50 of DAMGO = 36.32 ± 1.85 nM and the IC50 of NAN = 50.29 ± 1.62 nM. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM (n = 3).

[35S]-GTPγS Functional Assay at the KOR and DOR.

As previously indicated, activating or blocking KOR or DOR may lead to undesirable effects which could limit the therapeutic utility.50–53 Therefore, we determined the potency and efficacy of NAN at the DOR and KOR using the same cell line expressing mouse KOR or DOR (mKOR-CHO and mDOR-CHO). The efficacy was calculated as a percent of the effect of a maximal effective concentration of a full KOR or DOR agonist (U50,488H or SNC80, respectively). Results showed that NAN had relatively low potency at KOR with an EC50 value of ~18 nM, which is less potent than U50,488H and NTX (Table 2). In addition, NAN was an intermediate efficacy KOR agonist (Emax ~ 74%) compared to NTX (Emax ~ 27%).

Table 2.

Efficacy and Potency of NAN in the KOR and DOR CHO Cells

| DOR |

KOR |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | EC50 (nM) | Emax (% max of SNC80) | EC50 (nM) | Emax (% max of U50,488H) |

| SNC80 | 87.58 ± 22.33 | 100.23 ± 4.00 | ND | ND |

| U50,488H | ND | ND | 10.43 ± 0.66 | 100.41 ± 1.50 |

| NTX | NDa | NDa | 3.25 ± 0.70 | 27.12 ± 2.48 |

| NAN | 22.81 ± 3.95 | 26.67 ± 1.17 | 17.79 ± 3.24 | 73.90 ± 3.69 |

ND means not determined. Emax and EC50 of NTX in DOR CHO cells could not be determined because percent stimulation was very low. Bmax values for the DOR and KOR obtained from saturation binding assay were 1.76 ± 0.23 and 1.80 ± 0.11 pmol/mg, respectively.

At the DOR, NAN was a low-efficacy partial agonist (Emax ~ 27%) with relatively low potency (EC50 ~ 23 nM) (Table 2). In fact, the potency of NAN at the DOR was ~20-fold lower than that at the MOR (Table S1). NTX had extremely low DOR efficacy and did not stimulate [35S]-GTPγS binding at concentrations up to 10 μM (Table 2). NAN was more potent at the MOR than the DOR, which was in accordance with the binding affinity previously reported for NAN (MOR Ki = 0.23 ± 0.02 nM, DOR Ki = 13.69 ± 1.39 nM).42 NAN at a concentration of 3 μM did not inhibit binding of [3H]-nociceptin to the NOP receptor. In general, these results demonstrate NAN is an intermediate efficacy KOR agonist, a low-efficacy partial DOR agonist and does not bind to the NOP.

One approach to develop opioid use disorder medications is to design multifunctional or multitarget opioid receptor ligands.54,55 As mentioned earlier, undesirable effects of opioid agonist include respiratory depression and abuse potential and are primarily mediated through MOR activation. Although KOR agonists produce undesirable effects such as dysphoria and diuresis,50,51 activation of the KOR attenuates the abuse-related effects of abused drugs.56 Thus, the combined MOR partial agonist and intermediate efficacy KOR agonist profile of NAN may be suitable for its development as a candidate for opioid use disorder pharmacotherapy.

Opioid Withdrawal Studies.

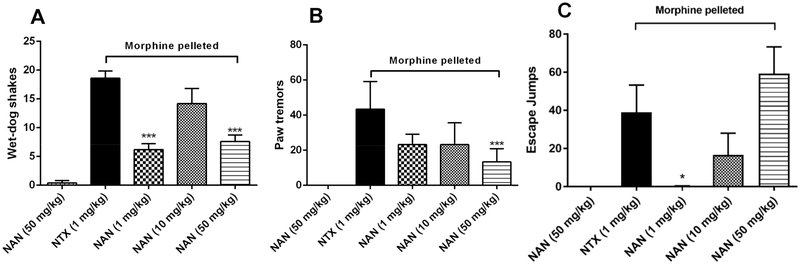

Studies have shown that opioid antagonists such as naltrexone and naloxone precipitate somatic opioid withdrawal signs when given to opioid dependent patients.57–59 Thus, we determined whether NAN would produce opioid withdrawal signs in morphine-pelleted mice (Figure 5). In this study, somatic signs of opioid withdrawal in mice (wet-dog shakes, paw tremors, and jumps) were observed for a 20 min period after injecting the mice with NAN. A 50 mg/kg dose of NAN did not induce any significant withdrawal signs in placebo-pelleted mice (Figure 5, the first columns). A 1 mg/kg dose of NAN produced significantly less wet-dog shakes and escape jumps than 1 mg/kg NTX (Figure 5A and C, the third columns) in morphine-pelleted mice. Moreover, 50 mg/kg NAN also produced significantly less wet-dog shakes and paw tremors than 1 mg/kg NTX (Figure 5A and B, the fifth columns). However, 10 and 50 mg/kg NAN produced escape jumps that were not significantly different from those at 1 mg/kg NTX (Figure 5C, the fourth and fifth columns). Overall, NAN produced significantly less withdrawal signs in two out of three tests than NTX across similar doses, which could be due to the higher MOR efficacy of NAN compared to NTX (NAN Emax (%DAMGO) = 25.46 ± 1.58, NTX Emax (%DAMGO) = 9.73 ± 0.72) (Table S1). In summary, these results suggest that NAN would produce less withdrawal effects than NTX when initiated as an opioid use disorder medication and therefore may enhance patient medication compliance.

Figure 5.

NAN (s.c.) in opioid-withdrawal assays in chronic morphine-exposed mice (n = 5): (A) Wet-dog shakes, (B) paw tremors, and (C) escape jumps. The first column in each figure represents placebo-pelleted mice, while the second to the fifth columns represent morphine-pelleted mice. *** P < 0.001, * P < 0.05, compared to 1 mg/kg naltrexone (NTX, s.c.).

Effects of NAN on MOR Regulation.

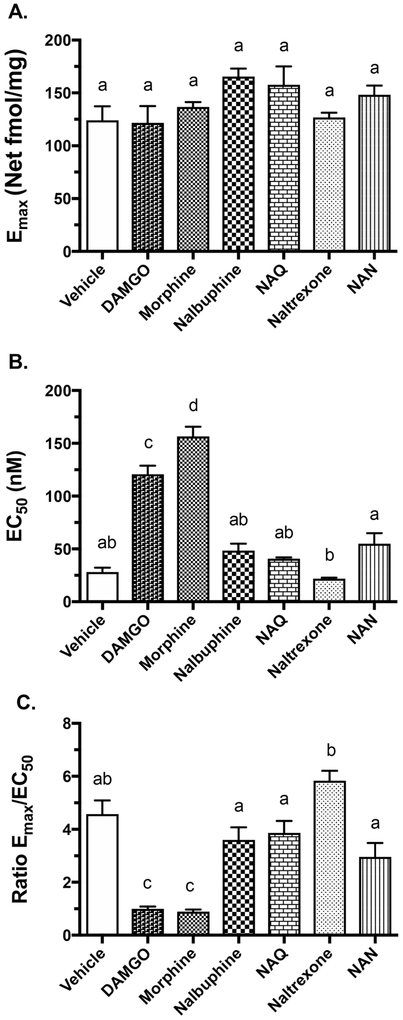

Since NAN produced significantly less withdrawal signs than naltrexone in vivo, possibly due to its higher efficacy on the MOR, a study was conducted to determine whether NAN produces cellular adaptation. Cellular adaptation to opioids may result in part from downregulation or desensitization of the MOR due to continuous opioid agonist exposure.38,53,60 mMOR-CHO cells were incubated for 24 h with NAN along with MOR ligands of varying efficacy. Cellular adaptation was quantified as an increase in the EC50 and/or reduction in the Emax value of DAMGO to stimulate [35S]-GTPγS binding in membranes from ligand-treated cells. Prior treatment with the opioid agonists (morphine and DAMGO) resulted in significant increases in DAMGO EC50 values, whereas treatment with the MOR antagonist NTX and low efficacy partial agonists nalbuphine and NAQ did not produce a significant change in the DAMGO EC50 value compared to vehicle treatment (Figure 6B). Treatment with NAN did not alter the DAMGO EC50 value compared to the vehicle treatment, however it was significantly elevated compared to treatment with NTX (Figure 6B). Neither treatment with MOR agonists nor antagonists produced any significant changes in the DAMGO Emax values (Figure 6A). To further examine the effects of ligand pretreatment on parameters of DAMGO-stimulated G-protein activation, we also calculated the Emax/EC50 ratio as a measure of receptor activation efficiency as we previously published.38 This ratio showed a significant decrease in cells treated with DAMGO or morphine, but not in cells treated with any of the low efficacy ligands, compared to vehicle-treated cells (Figure 6C). However, treatment with nalbuphine, NAQ or NAN all slightly decreased this ratio relative to treatment with NTX. Thus, morphine and DAMGO treatment produced an apparent desensitization of the MOR compared to vehicle treatment, whereas treatment with low efficacy ligands did not. Overall, the results obtained were similar to those reported in our previously published study.38

Figure 6.

Effects of ligand pretreatment of mMOR-CHO treated cells on mMOR-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding. (A) Emax values of DAMGO. (B) EC50 values of DAMGO. (C) Receptor efficiency (Emax/EC50). Data are presented as mean values ± SEM (n = 4). Statistics: values without any of the same letter designations are p < 0.05 different from each other by ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test.

To determine whether treatment with NAN affected MOR levels, saturation binding of [3H]naloxone to MOR was conducted in membranes from NAN-treated mMOR-CHO cells. This result was compared to our previously reported values obtained after treatment of these cells with the same opioid ligands examined above.38 Both morphine and DAMGO produced an approximate 50% reduction in receptor density (Bmax) whereas the low efficacy opioid ligands did not (Table 3). Interestingly, treatment with NTX, NAQ or NAN produced a significant reduction in the apparent [3H]naloxone binding affinity (Table 3). The reason for this effect is unclear but could be due to inadequate removal of these high affinity ligands from the MOR before the binding study was conducted. If so, then the magnitude of the apparent increase in [3H]naloxone KD value after NAN treatment (7.7-fold) compared to NTX and NAQ(3.5–4-fold), suggests that NAN may dissociate more slowly from the MOR.

Table 3.

Bmax and KD values of [3H]Naloxone Saturation Binding in Opioid Ligand-Pretreated MOR-CHO Cell Membranesa

| pretreatment | Bmax (pmol/mg) | KD (nM) |

|---|---|---|

| vehicleb | 2.90 ± 0.24 | 1.16 ± 0.23 |

| DAMGOb | 1.49 ± 0.12* | 1.96 ± 0.07 |

| morphineb | 1.58 ± 0.10* | 1.84 ± 0.28 |

| nalbuphineb | 3.66 ± 0.26 | 1.70 ± 0.10 |

| NAQb | 3.75 ± 0.34 | 4.44 ± 0.37** |

| NAN | 3.92 ± 0.20 | 10.00 ± 1.63**** |

| naltrexoneb | 3.86 ± 0.68 | 3.84 ± 0.44* |

Data are mean ± SEM of Bmax and KD values derived from nonlinear regression analysis of [3H]naloxone saturation binding curves (n = 4).

p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.0001 different from corresponding value in vehicle-pretreated cells.

Values previously published.38

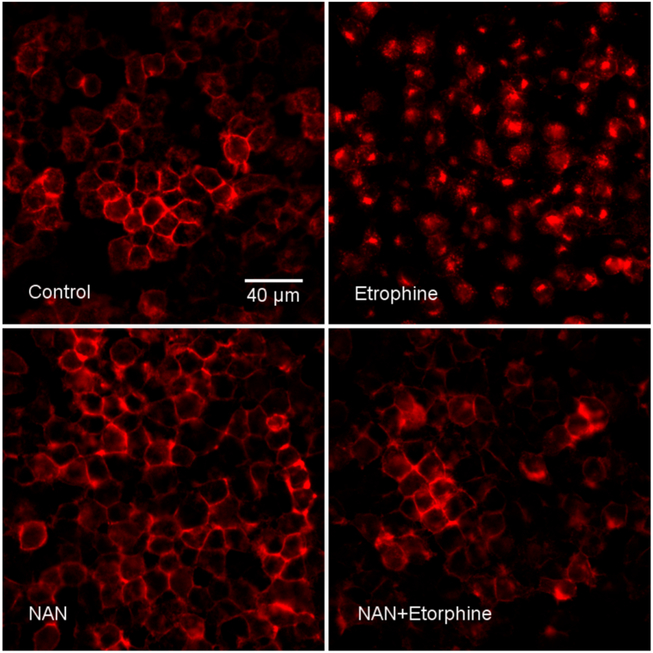

Quantification using operational models to assess the decrease of functional MOR-effector signaling after chronic morphine treatment in isolated systems suggest that a loss of approximately 80% of functional surface MOR would be required to produce the observed reduction in the potency of DAMGO.61,62 Both morphine and DAMGO pretreatment produced less than 80% reduction in MOR density; therefore, the apparent desensitization produced by these agonists may not be entirely due to receptor downregulation, but loss of receptor efficiency (Figure 6C). However, because we measured downregulation of total membrane-associated MOR, one possibility is a subset of these binding sites were internalized MOR in the vesicular fraction. Therefore, another study was conducted to visually determine whether NAN induced MOR internalization. N2A-HA-rMOR-N2A cells incubated with mouse anti-HA.11 antibody for 1 h, were treated with NAN and the high efficacy MOR agonist etorphine, fixed with 4% PFA and immunostained with Alexa Fluor 594 (Red) goat anti-mouse IgG. NAN did not induce MOR internalization while etorphine induced MOR internalization compared to the control (Figure 7). Importantly, NAN inhibited etorphine-induced MOR internalization, indicating that it acts as an antagonist of agonist-induced internalization (Figure 7). Overall, these in vitro data suggest NAN may not produce MOR adaptations that contribute to opioid tolerance.

Figure 7.

NAN inhibited etorphine-induced MOR internalization in N2A-HA-rMOR-N2A cell line. Cells were incubated with mouse anti-HA.11 antibody for 1 h, treated with or without ligands as indicated, fixed with 4% PFA, and immunostained with Alexa Fluor 594 (Red) goat anti-mouse IgG (see Methods). Panel labels: Control showed HA-rMOR in plasma membranes. Etorphine, treatment with 1 μM etorphine for 15 min induced HA-rMOR endocytosis. NAN, treatment at 10 μM for 30 min had no effect on HA-rMOR distribution. NAN+Etorphine, treatment with NAN inhibited HA-rMOR internalization induced by etorphine. This experiment was performed twice with two different HA-rMOR-N2A clonal cells with similar results. Results from one of the clonal cells (H38) are presented.

Drug Discrimination Studies.

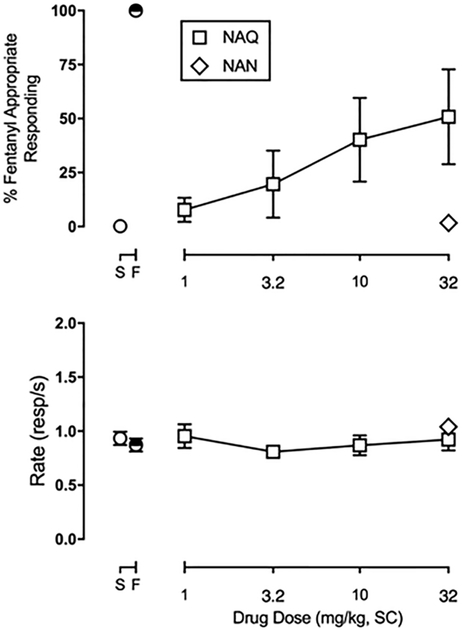

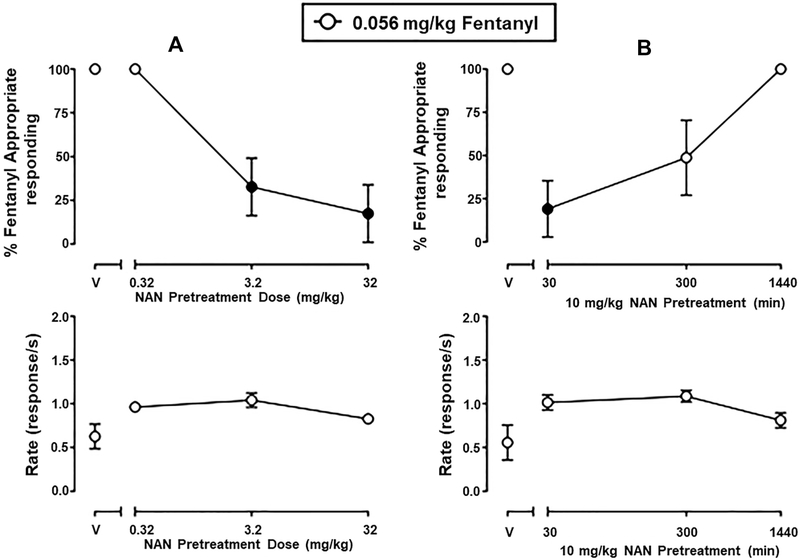

Although low efficacy opioid partial agonists like nalbuphine generally have lower abuse liability than high efficacy opioids like morphine and fentanyl, they nonetheless have some abuse liability due to overlapping subjective effects. One approach to assess subjective effects of drugs is the drug discrimination assay.63 Therefore, a study was conducted in rats trained to discriminate between fentanyl (0.04 mg/kg) and saline to determine whether NAN would produce MOR agonist fentanyl-like discriminative stimulus effects. On fentanyl and saline training days preceding all test days, mean ± SEM percent injection-appropriate responding was 99.7 ± 0.2 and 99.8 ± 0.1, respectively. Rates of responding (mean ± SEM) during fentanyl and saline training days were 0.82 ± 0.05 and 0.89 ± 0.04 responses/s, respectively. NAN (32 mg/kg) produced a maximum of 1.7 ± 1.5% fentanyl-appropriate responding (FAR). For comparison, NAQ, another low efficacy MOR-selective ligand identified by us previously35,64 and further examined in studies described above, produced fentanyl-appropriate responding in a dose-related manner, up to a maximum of 56.1 ± 17.4% at 32 mg/kg of NAQ (Figure 8). Neither NAN nor NAQ significantly altered rates of responding (data not shown). Because 32 mg/kg NAN failed to produce >50% fentanyl-like discriminative stimulus effects in any animal, two additional experiments were conducted to determine the potency and time course of NAN to antagonize the discriminative stimulus effects of fentanyl. These results are shown in Figure 9. In the potency studies, 3.2 and 32 mg/kg, but not 0.32 mg/kg, NAN significantly attenuated the discriminative stimulus effects of fentanyl (Figure 9A, upper panel) (F1.751,8.755 = 13.79, p = 0.0024). In the time course studies, 10 mg/kg NAN administered as a 30 min pretreatment significantly attenuated the discriminative stimulus effects of fentanyl and lasted for up to 300 min (Figure 9B, upper panel) (F1.175, 8.75 = 10.46, p = 0.0056). NAN did not significantly alter rates of responding in either the potency or time course studies (Figure 9, lower panels). Response rate data collected from the drug discrimination studies provide evidence that the antagonist effect of NAN is not due to elimination of behavior, but a selective effect to attenuate the discriminative stimulus effects of fentanyl. Thus, even though NAN has intermediate efficacy KOR agonist effects in vitro, NAN did not produce a generalized behavioral depression. Furthermore, NAN did not produce antinociception in the tail-flick assay42 suggesting that its MOR efficacy or KOR efficacy or occupancy was not sufficient in that procedure. Future studies using conditioned place preference or aversion should be conducted to establish that NAN does not have rewarding or aversive effects. Overall, these behavioral results demonstrate that NAN functioned as a competitive MOR antagonist whereas NAQ functioned as a low efficacy MOR partial agonist in opioid agonist drug discrimination. This latter result agrees with previous findings that NAQ acted similarly to the MOR partial agonist nalbuphine in intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS) studies.64

Figure 8.

Effects of NAN (32 mg/kg, SC) and NAQ (1–32 mg/kg, SC) to produce fentanyl-appropriate responding in rats trained to discriminate 0.04 mg/kg, SC fentanyl from saline. Abscissa: drug dose in milligrams per kilogram. Ordinate: top panels: percent fentanyl-appropriate responding; bottom panels: response rate in responses/s. The symbols above saline (S) or fentanyl (F) show percent fentanyl-appropriate responding on all training days preceding test days. Each point represents the mean ± SEM of 6 (3 female and 3 male) rats.

Figure 9.

Potency (left panels) and time course (right panels) of NAN pretreatment on the discriminative stimulus effects of 0.056 mg/kg fentanyl in rats. Left abscissa: drug dose in milligrams per kilogram. Right abscissa: NAN pretreatment time (min) before fentanyl administration. Top ordinate: percent fentanyl-appropriate responding. Bottom ordinate: rates of responding in responses per sec. Each point represents the mean ± SEM of 6 (3 female and 3 male) rats. Filled points denote statistically significance compared to vehicle pretreatment (p < 0.05).

Molecular Modeling Study.

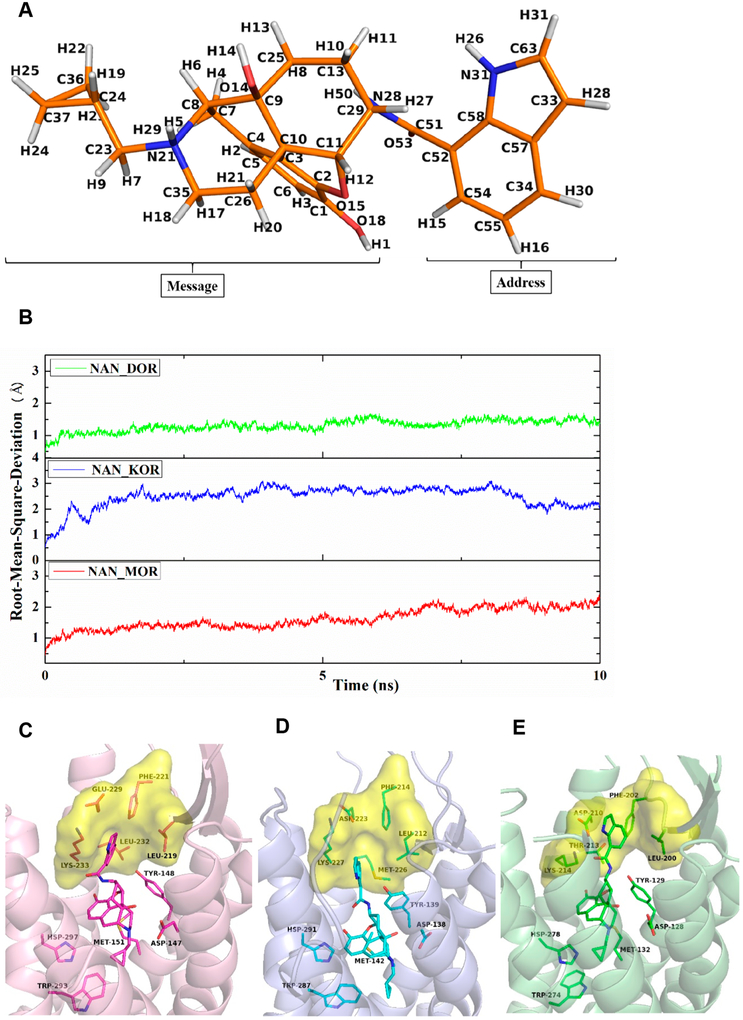

Finally, to understand the different efficacies and affinities of NAN (Figure 10A) at the MOR, KOR, and DOR, docking studies were first conducted to obtain the complexes of NAN with the three opioid receptors using the crystal structures of the inactive form of the MOR (PDB ID: 4DKL),65 the active form of the KOR (PDB ID: 6B73),66 and the inactive form of the DOR (PDB ID: 4EJ4).67 The highest scored (CHEM-PLP) docking solutions were further selected as the optimal binding poses (defined as NAN_MOR, NAN_KOR, and NAN_DOR complexes) to conduct the 10 ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. After the MD simulations, the root-mean-square deviation (rmsd) values of all the protein backbone atoms relative to the respective starting structures were calculated and the results are displayed in Figure 10B. The average rmsd values of the NAN_MOR, NAN_KOR, and NAN_DOR complexes were determined as 1.97, 2.53, and 1.43 Å, respectively, which indicated that the three complexes achieved stability after 10 ns MD simulations.68–70Therefore, snapshots from the 7–10 ns of MD simulations was utilized to analyze the interactions between the ligand and the receptors.

Figure 10.

Chemical structure of NAN with atom notation were derived from the complex after molecular dynamics simulations (A). Root-mean-square deviation (rmsd) of the protein backbone atoms of the three systems relative to the respective starting structures (B). Binding modes of NAN_MOR (C), NAN_KOR (D), and NAN_DOR (E) complexes with key amino acid residues in the binding site after 10 ns MD simulations. Protein shown as cartoon model in light-pink (MOR), light-blue (KOR), and light-green (DOR); NAN and key amino acid residues shown as stick model. Carbon atoms: NAN_MOR complex (magentas); NAN_KOR complex (cyan); NAN_DOR complex (green); surface models in yellow represent the “address” domain of MOR, KOR, and DOR.

The binding modes of the NAN_MOR, NAN_KOR, and NAN_DOR complexes after 10 ns MD simulations are shown in Figure 10, where it can be seen that NAN bound to the same binding domain of the MOR, KOR, and DOR. Thus, the epoxymorphinan moiety (“message” portion) interacted with the “message” domain; the indole ring (“address” portion) interacted with the “address” domain, which was similar to other reported opioid ligands.71–73 In the MOR_NAN complex, the “message” portion of NAN formed ionic interaction with D1473.32, hydrogen bonding interaction with Y1483.33, and hydrophobic interactions with residues M1513.36, W2936.48, and H2976.52. Meanwhile, the “address” portions of NAN formed hydrophobic interactions with the “address” domain of the MOR, formed by residues L219ECL2, F221ECL2, E2295.35, L2325.38, and K2335.39 (Figure 10C and Table 4). In the KOR_NAN complex (Figure 10D), the “address” portion of NAN was much farther away from the “address” domain of the KOR (Table 4). The cause of this movement was the larger spatial structure of the side chain of M2265.38 in the KOR_NAN complex than that of the side chain of L2325.38 in the MOR_NAN complex. As a consequence, the interaction between the “address” portion of NAN and the “address” domain of the KOR was smaller than that between the “address” portion of NAN and the “address” domain of the MOR. For the DOR_NAN complex (Figure 10E), owing to the much smaller spatial structure of the side chain of T2135.38 than that of the side chain of L2325.38 in the MOR_NAN complex, the “address” portion of NAN moved close to the “address” domain of the DOR than that of the MOR (Table 4). Consequently, the binding of the “address” portion of NAN with the “address” domain of the DOR may be stronger than that of the “address” portion of NAN with the “address” domain of the MOR. However, the movement of the “address” portion of NAN may further result in the “message” portion of NAN moving away from the “message” domain of the DOR (Table 4). Hence, the hydrophobic interactions between the “message” portion of NAN and residues W2746.48 and H2786.52 in the NAN_DOR complex were weaker than those in the NAN MOR and NAN KOR complexes, which may be the reason for the lower binding affinity of NAN and possibly the lower activation efficacy at the DOR compared to the MOR and KOR.42

Table 4.

Measured Shortest Distances between Atoms on Critical Amino Acid Residues and Atoms on the Ligands in NAN_MOR, NAN_KOR, and NAN_DOR Complexes after 10 ns MD Simulations

| complex | binding domain |

atom of ligand |

atom of residue | distance (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAN_MOR | message | N21@NAN | OD2@D1473.32 | 3.5 |

| O15@NAN | OH@Y1483.33 | 4.5 | ||

| C2@NAN | CE@M1513.36 | 4.0 | ||

| C36@NAN | CH2@W2936.48 | 4.1 | ||

| C5@NAN | CE1@H2976.52 | 5.3 | ||

| address | C33@NAN | CB@L219ECL2 | 5.4 | |

| C34@NAN | CZ@F221ECL2 | 4.1 | ||

| C33@NAN | CD@E2295.35 | 4.2 | ||

| C55@NAN | CD2@L2325.38 | 4.0 | ||

| C57@NAN | CE@K2335.39 | 3.4 | ||

| NAN_KOR | message | N21@NAN | OD2@D1383.32 | 2.8 |

| O15@NAN | OH@Y1393.33 | 4.2 | ||

| C2@NAN | CE@M1423.36 | 3.7 | ||

| C36@NAN | CH2@W2876.48 | 4.1 | ||

| C5@NAN | CE1@H2916.52 | 4.4 | ||

| address | C55@NAN | CD1@L212ECL2 | 5.0 | |

| C34@NAN | CE2@F214ECL2 | 5.7 | ||

| C34@NAN | CG@D2235.35 | 5.9 | ||

| C55@NAN | CG@M2265.38 | 4.5 | ||

| C34@NAN | CG@K2275.39 | 3.7 | ||

| NAN_DOR | message | N21@NAN | OD2@D1283.32 | 4.5 |

| O15@NAN | OH@Y1293.33 | 3.4 | ||

| C1@NAN | CE@M1323.36 | 4.7 | ||

| C36@NAN | CH2@W2746.48 | 9.9 | ||

| C5@NAN | CE1@H2786.52 | 5.9 | ||

| address | C55@NAN | CB@L200ECL2 | 3.7 | |

| C34@NAN | CE2@F202ECL2 | 4.0 | ||

| C33@NAN | CG@D2105.35 | 4.0 | ||

| C55@NAN | CG2@T2135.38 | 6.8 | ||

| C52@NAN | CE@K2145.39 | 4.5 |

In conclusion, NAN was identified as a low-efficacy MOR partial agonist which antagonized the effects of DAMGO in vitro and morphine42 and fentanyl in vivo. The pharmacological profile of NAN at the DOR, KOR, MOR, and NOP was determined and NAN was characterized as a low-efficacy DOR and MOR partial agonist and an intermediate efficacy KOR agonist. In addition, NAN did not show NOP binding at 3 μM. Molecular modeling studies showed that NAN formed weaker hydrophobic interactions at the DOR compared to the MOR and KOR which could account for the lower binding affinities at the DOR as previously observed. MOR desensitization, downregulation, and internalization experiments demonstrated that NAN may not produce MOR adaptations that contribute to cellular tolerance. Withdrawal studies in morphine-pelleted mice showed that NAN produced significantly less withdrawal signs than NTX at similar doses. Additional in vivo studies conducted using rats that have been trained to discriminate between fentanyl and saline suggested that NAN acted as a lower efficacy MOR ligand than NAQ because, unlike NAQ it did not produce MOR agonist-like discriminative stimulus effects. Moreover, NAN antagonized the discriminative stimulus effects of fentanyl. Thus, NAN would be predicted to have lower abuse potential than NAQ. Although future studies should examine effects of NAN on other abuse related actions of opioids, such as opioid self-administration, modulation of ICSS responding, and place conditioning, NAN warrants further consideration as a candidate medication for opioid use disorder treatment.

■ METHODS

Drugs.

DAMGO, fentanyl HCl, morphine sulfate, (−)-nalbuphine, U50,488 HCl, and (−)-naltrexone HCl were procured from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), Bethesda, MD and then made into solutions by dissolving in double distilled water (ddH2O). NAN and NAQ were synthesized as hydrochloric acid (HCl) salts in our laboratory as previously reported.42 For the in vitro studies, NAN was dissolved in 90% ddH2O and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO. In the animal studies, NAQ was dissolved in 40% DMSO and 60% sterile water. NAN was dissolved in 25% DMSO and 75% sterile water. All drugs were administered subcutaneously (SQ) at an injection volume of 1–2 mL/kg. SNC80 was procured from Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK; guanosine-5′-O′-(γ-thio)-triphosphate (GTPγS) and GDP from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; [35S]-GTPγS from PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA. All drug doses for in vivo experiments were expressed as the salt forms listed above.

G-Protein Activation Assays.

[35S]GTPγS Functional Studies.

Membrane preparations of the mMOR-CHO, mKOR-CHO, mDOR-CHO, and mouse thalamus were used in these experiments. In this assay, 10 or 8 μg of membrane protein from the cell lines or thalamus was incubated with 20 μM GDP (30 μM GDP was used for the study using thalamus), 0.1 nM [35S]GTPγS, assay buffer (TME + 100 mM NaCl), and varying concentrations of the compounds under investigation for 90 min (incubation was 2 h for thalamus membrane preparations) in a 30 °C water bath. Nonspecific binding was determined with 20 μM unlabeled GTPγS. Here, 3 and 10 μM DAMGO were included in the assay as maximally effective concentration of a full agonist for the MOR in mMOR-CHO cells and thalamus, respectively; 5 μM U50,488H and 5 μM SNC80 were used for the KOR and DOR. The incubation was terminated by rapid vacuum filtration through GF/B glass fiber filters. Bound radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation spectrophotometry. The competitive antagonist studies followed the same procedure except that 5 nM of NAN and NTX were incubated with varying concentrations of DAMGO.

Data Analysis of [35S]GTPγS Functional Assay.

All samples were assayed in duplicate and repeated at least four times for a total of ≥4 independent determinations. Results were reported as mean values ± SEM. Concentration–effect curves were fit by nonlinear regression to a one-site binding model, using Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA) to determine EC50 and Emax values. The Emax values for receptors were calculated as relative to net full agonist-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding, which is defined as (net-stimulated binding by ligand/net-stimulated binding by maximally effective concentration of a full agonist) × 100%. Ke values in the competitive antagonism studies were determined using the equation Ke = [Ant]/DR-1, where [Ant] is the concentration of antagonist and DR is the ratio of the DAMGO EC50 of values in the presence and absence of antagonist.

NOP Receptor Binding Assay.

Cell Membrane Preparation.

A clonal CHO cell line stably expressing the human NOP receptor at ~5 pmol/mg protein was cultured in an incubator maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in MEM (Minimum Essential Medium, ref 41500, Gibco, NY) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1 mM pyruvic acid, and 1× antibiotics (A5955, Sigma, MO) to ~80% confluence. Membranes were prepared according to our published procedures.74 Cells were collected in PBS containing 1 mM EDTA 0.54 mM, NaCl 140 mM, KCl 2.7 mM, Na2HPO4 8.1 mM, KH2PO4 1.46 mM, and glucose 1 mM, pH 7.0) and centrifuged at 500g for 3 min. Cell pellets were suspended in a hypotonic lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, pH 7.4), centrifuged at 50,000g for 30 min and the pellet of crude membranes was resuspended in lysis buffer, centrifuged again. The pellet was resuspended in binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1%BSA, pH 7.4), aliquoted, snap-frozen in ethanol/dry ice bath, and stored in −80 °C freezer.

[3H]nociception Binding.

Binding was performed in 1 mL of binding buffer containing membranes (20 μg proteins), 0.2 nM [3H]nociceptin, with or without 3 μM of a test ligand as indicated. Nonspecific binding was defined with 1 μM cold nociceptin. After incubation on a shaker at room temperature for 1h, bound and free [3H] nociceptin were separated by filtration under vacuum with a Brandel 24-channel harvester and GF/B filter paper. Radioactivity on filter paper was determined by liquid scintillation counting.

Data Analysis.

% inhibition was calculated as follows.

Calcium Flux Assay.

hMOR-CHO cells were maintained as described previously. After 4 h of Gαqi5 transfection, cells were plated at 30,000 cells per well into a clear bottom black walled 96-well plate (Greiner Bio-one) and incubated for 24 h. The growth media was then decanted, and the wells were washed with 50:1 HBSS:HEPES assay buffer. Cells were then incubated with Fluo4 loading buffer (40 μL of 2 μM Fluo4-AM (Invitrogen), 84 μL of 2.5 mM probenecid, in 8 mL of assay buffer) for 30 min. For antagonism studies, varying concentrations of test compounds were added in triplicate and the plate was incubated for an additional 15 min. Plates were then read on a FlexStation3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices) at 494/516 ex/em for a total of 120 s. For the agonism study, after 15 s of reading, varying concentrations of test compounds in triplicate or 500 nM of DAMGO (antagonism study) in assay buffer, or assay buffer alone (control), were added. Changes in Ca2+ flux were monitored and peak height values were recorded. The obtained values were then subjected to nonlinear regression analysis to determine EC50 or IC50 values using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

MOR Desensitization and Downregulation Study.

Incubation of mMOR-CHO Cells with Opioid Ligands.

mMOR-CHO cells were grown in culture media (DMEM/F12 media, 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 0.5% G418) for 5 days in an incubator set at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and 95% humidity. On the fifth day when the cells were confluent, the culture media was removed and the cells were rinsed with 5 mL of PBS. The cells were then treated with DAMGO (5 μM), morphine (5 μM), nalbuphine (1 μM), NAN (1 μM), naltrexone (1 μM), or vehicle (0.02% DMSO) dissolved in DMEM/F12 media and incubated for 24 h. After incubation, the treatment media was removed and the cells were washed three times with 10 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Another 5 mL of PBS was added to each dish, and the cells were then scraped off the dishes using a scraper. The cells were then centrifuged at 1,000g for 10 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant was decanted and membrane buffer (50 mM Tris, 3 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM EGTA, pH 7.4) was added to each sample. The cells were then homogenized and then centrifuged again at 50,000g for 10 min. The supernatant was decanted, and the cells homogenized again in membrane buffer. Bradford assay was conducted to determine the concentration of the membrane protein. The membrane protein preparations were then stored at −80 °C.

MOR Saturation Assay.

Membranes were homogenized in membrane buffer and centrifuged at 50,000g for 10 min. This step was repeated to ensure that the drugs were completely removed from the receptor. The supernatant was then decanted and membranes were resuspended in 50 mM Tris, 3 mM MgCl2, and 0.2 mM EGTA (pH 7.4). The MOR membrane protein (30 μg) was then incubated with varying concentrations of [3H]naloxone (specific activity = 66.58 Ci/mmol) for 90 min at 30 °C. Nonspecific binding was determined using 5 μM naltrexone. The incubation was terminated by rapid filtration and bound radioactivity was determined as described above. KD and Bmax values were determined by nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The [35S]-GTPγS functional assay described above was used to investigate desensitization. The membranes from different ligand-treated mMOR-CHO cells preparations were incubated with varying concentrations of DAMGO.

MOR Internalization Assay.

Cell Culture.

Rat MOR cDNA was epitope-tagged with HA at N-terminus and inserted in pcDNA vector with neomycin resistance gene. The construct was transfected into Neuro2A mouse neuroblastoma cells (ATCC) and grown in medium containing 0.5 mg/mL G418 (Geneticin). Clonal cells stably expressing MOR were screened by [3H]diprenorphine binding assay. Two clonal cell lines expressing MOR at 1–2 pmol/mg protein (clones H38 and H16) were used for the internalization experiment (N2A-HA-rMOR). Cells were cultured in 10 cm dishes an incubator maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in humidified air in MEM (Minimum Essential Medium, ref 41500, Gibco, NY) supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin, streptomycin, and amphotericin (A5955, Sigma, MO) and grown to 80% confluence.

MOR Internalization.

Cells were subcultured into 6-well plates with a coverslip placed in each well at 300,000 cells per well. At 48 h later, mouse anti-HA.11 antibodies (Clone 16B12, BioLegend, CA) were added at 1:1000 to cell medium and incubated for 1 h. NAN (final 10 μM), or vehicle was subsequently added and incubated for 15 min. Etorphine (final 1 μM) or vehicle was then added and incubated for another 15 min. Plates were placed on ice and washed three times with ice-cold PBS. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PB for 15 min at room temperature, and washed three times, 5 min each time with 0.15 M Tris-HCl, pH7.4. The secondary antibodies, Alexa Fluor594 goat anti-mouse IgG (A11005, Invitrogen, OR) in PBS containing 5% normal goat serum, 0.1% Triton X100, 0.1 M glycine (pH 7.4) were added at 2 mL/well (1:1000) and incubated on a shaker with light protection for 2 h at room temperature. After washing three times with PBS, the coverslips were mounted on slides using mounting medium (H-1200, Vector Laboratories, CA) and cured overnight. The images were acquired by Nikon Eclipse TE300 fluoresce microscope coupled to a digital camera (MagnaFire) using a 20× objective and processed with ImageJ.

Withdrawal Assay in Chronic Morphine-Pelleted Mice.

Animals.

Male Swiss Webster mice (25–30 g, Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) were raised in animal care quarters and maintained at room temperature on light-dark cycle. Food and water were available ad libitum. Protocols and procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center and complied with the recommendations of the IASP (International Association for the Study of Pain).

Withdrawal Protocol.

This experiment was conducted as previously reported. Briefly, a 75 mg morphine pellet was implanted into the base of the neck of the mice and the mice were then given time to recover in their home cages before the test was conducted. The mice were then allowed for 30 min habituation to an open-topped, square, clear Plexiglas observation chamber (26 × 26 × 26 cm3) with lines partitioning the bottom into quadrants before they were given an antagonist. All drugs and test compounds were administered subcutaneously (s.c.). Withdrawal was precipitated at 72 h from pellet implantation with naltrexone (1.0 mg/kg, s.c.), and the tested compounds at indicated doses. Withdrawal commenced within 3 min after antagonist administration. Escape jumps, paw tremors and wet dog shakes were quantified by counting their occurrences over 20 min for each mouse using five mice per drug. The data were expressed as mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA followed by the post hoc Dunnett test were performed to assess significance using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Drug Discrimination Study.

Subjects.

Seven adult Sprague–Dawley rats (3 males and 4 females, Envigo, Frederick, MD) served as subjects for the discrimination studies. Rats were fed sufficient daily amounts of rodent chow (Envigo Teklab Lab Rat/Mouse 7012, Teklad Diets, Madison, WI) to maintain weight ranges from 300 to 350 g (males) and 200–250 g (females) throughout the entire study. Rats were individually housed and had unlimited access to water in the home cage. Rats were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled vivarium that was maintained on a 12 h light–dark cycle (lights on from 0600 to 1800) and accredited by AAALAC International. Experimental protocols were approved by the IACUC at Virginia Commonwealth University and conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health 2011 Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.75

Apparatus.

Studies were conducted in sound-attenuating boxes containing modular acrylic and metal test chambers (29.2 × 30.5 × 24.1 cm; Med Associates, St. Albans, VT). Each chamber contained two retractable response levers (4.5 cm wide, 2.0 cm deep, 3.0 cm above the floor), three stimulus lights (red, yellow, and green) centered 7.6 cm above the lever, and a liquid dipper along one of the chamber walls. In addition, sonalert modules (2900 and 4500 Hz) were placed in the upper left and right corners of the chambers, respectively. Custom programs written in Med-State notation (Med Associates) controlled experimental parameters and data collection.

Discrimination Training.

After initial magazine training, rats were trained to discriminate 0.04 mg/kg subcutaneous (SC) fentanyl from saline in a two-lever discrimination procedure modified from a previously described procedure. The position of the fentanyl-appropriate lever was the right lever for 6 rats (2 males; 4 females) and the left lever for 1 male rats. Saline or 0.04 mg/kg fentanyl was administered SC 30 min before the start of the response period, in a double alternating sequence. Discrimination training sessions were conducted at least 5 days per week and consisted of a 10 min response period where rats could earn up to 10 dipper presentations of 1 mL liquid food (Ensure Original nutrition shake, Abbott Nutrition, Columbus, OH) by responding under a fixed-ratio (FR) 10 schedule of reinforcement. At the start of the response period, both levers extended and all stimulus lights above both levers were illuminated. Completion of the ratio requirement on the injection-appropriate lever resulted in liquid food presentation and a three-millisecond tone from both sonalert modules. Responses on the injection-inappropriate lever reset the ratio requirement for the injection-appropriate lever. The response period terminated after 15 min or after 10 reinforcers were earned. The criterion for accurate discrimination was (1) greater than 80% injection-appropriate responding before delivery of the first reinforcer, (2) greater than 80% injection-appropriate responding for the entire response period, and (3) completion of at least one ratio requirement for five out of six consecutive sessions.

Discrimination Testing.

Once rats met drug discrimination training criteria described above, test sessions were initiated. Test sessions were identical to training sessions, except that response requirement completion (FR10) on either lever resulted in liquid food presentation. Test sessions were generally conducted on Tuesdays and Fridays and training sessions were conducted on all other days. Test sessions were only conducted if a rat met criteria for the two preceding training sessions. Two types of test sessions were conducted. First, substitution tests were conducted to determine whether NAQ (1–32 mg/kg, SC) and NAN (32 mg/kg, SC) would produce fentanyl-like discriminative stimulus effects. Both NAQ and NAN were administered 30 min before the behavioral session. Second, in the absence of an effect in the substitution experiments, pretreatment studies to fentanyl were conducted to determine potency and time course to antagonize fentanyl discriminative stimulus effects. For potency studies, vehicle or NAN (0.32–32 mg/kg, SC) were administered as a 15 min pretreatment to 0.056 mg/kg fentanyl. For time course studies, 10 mg/kg NAN was administered 30, 300, and 1440 min (24 h) before 0.056 mg/kg fentanyl. All experimental manipulations were determined once in a cohort of 6 rats (3 males and 3 females). One female rat that completed all NAN experiments was not included in the NAQ experiments due to health issues unrelated to the experiment. A different female rat was added to the NAQ experiments to maintain the balanced sex design and sample size of six rats.

Data Analysis.

The primary dependent measures were (1) percent fentanyl-appropriate responding (%FAR) (calculated as (number of responses on the fentanyl-associated lever divided by the total number of responses on both the fentanyl- and saline-associated levers) × 100) and (2) rates of responding expressed as number of responses divided by total session time in seconds. Results were analyzed using a repeated-measures one-way ANOVA with drug dose or pretreatment time as the main factors. A significant main effect was followed up by a Dunnett post hoc test. In addition, data analysis was supplemented with an additional approach to provide summary measure of drug effects.76 Drugs that produced >80% fentanyl-appropriate responding were considered to produce full substitution. Drugs that produced between 20 and 80% fentanyl-appropriate responding were considered to produce partial substitution, and <20% was considered to produce no substitution.

Molecular Modeling Study.

The selectivity mechanisms of NAN at the MOR, KOR, and DOR were explored by the molecular modeling study. The chemical structure of NAN was first sketched by Sybyl-X 2.0 (TRIPOS Inc., St. Louis, MO). The X-ray crystal structures of the inactive form of the MOR (PDB ID: 4DKL),65 the active form of the KOR (PDB ID: 6B73),66 and the inactive form of the DOR (PDB ID: 4EJ4)67 were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) at http://www.rcsb.org were utilized as receptors. Second, the genetic algorithm docking program GOLD 5.6 with default settings was applied to dock NAN into the binding sites of the MOR, KOR, and DOR.77,78 Atoms within 10 Å of the γ-carbon atom of D3.32 in the three receptors were used to define the binding site. Moreover, the ionic interaction between the piperidine quaternary ammonium nitrogen of the ligands’ epoxymorphinan nucleus and D3.32, and the hydrogen bond between the ligands’ dihydrofuran oxygen and the phenolic oxygen of Y3.33 were used as constraints to conduct the automated docking. According to the fitness scores, the highest scored solutions (CHEM-PLP) of NAN in the MOR, KOR, and DOR (NAN_MOR, NAN_KOR, and NAN_DOR complexes) were further utilized to conduct the molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Before the MD simulations, the three complexes were embedded in a lipid (POPC) membrane bilayer and solvated with TIP3 water molecules by MEMBRANE plugin and SOLVATE plugin in the Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) program. After that, the saline solution (0.1 nM NaCl) was added to the solvated systems by the SOLVATE plugin in VMD.79 Simulations were conducted utilizing the CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) to generate the force field parameter of NAN.80–82 The CHARMM36 force field parameters were used as the force field parameters for proteins83,84 and lipids.85 All the MD simulations were conducted by the NAMD V2.8 program.86

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was partially supported by NIH/NIDA, DA024022, and DA044855 (Y.Z.), F31DA043921 (K.L.S.), VCU Professional Development Funds (M.L.B.), Jazan University (A.J.), and P30DA013429 and R01DA041359 (L.L.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acschemneuro.9b00038.

Potency and efficacy comparison of NAN and NAM; comparison of ligand Emax values in mMOR-CHO cells and mouse thalamus; Ca2+ flux assays in Gαqi5 transfected hMOR-CHO cells (PDF)

Notes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health. The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Sixtieth Congress (1909) An Act to Prohibit the Importation and Use of Opium for Other than Medicinal Purposes; Congress: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Muhuri P, Gfroerer JC, and Davies CM (2013) Associations of Nonmedical Pain Reliever Use and Initiation of Heroin Use in the US SAMHSA: CBHSQ Data Review p 17, SAMHSA. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, and Scholl L (2016) Increases in Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths — United States, 2010–2015. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 65, 1445–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, and Gladden MR (2016) Increases in Drug and Opioid Overdose Deaths — United States, 2000–2014. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 64, 1378–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Hedegaard H, Warner M, and Minino AM (2017) Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999–2016. NCHS Data Brief, p 294, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Ahmad FB, Rossen LM, Spencer MR, Warner M, and Sutton P (2017) Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts, National Center for Health Statistics, Atlanta. [Google Scholar]

- (7).CDC/NCHS, National Vital Statistics, Mortality (2017) CDC Wonder, US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Pardo B, and Reuter P (2018) Facing Fentanyl: Should the USA Consider Trialling Prescription Heroin? lancet. Psychiatry 5, 613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Katz J The First Count of Fentanyl Deaths in 2016: Up 540% in Three Years. The New York Times, New York, September 2, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- (10).NHTSA Public Affairs (2017) USDOT Releases 2016 Fatal Traffic Crash Data, NHTSA, Washington, DC, [Google Scholar]

- (11).National Center for Health Statistics. Firearm Mortality by State https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/firearm_mortality/firearm.htm (accessed Apr 9, 2018).

- (12).Kaplan S CDC Reports a Record Jump in Drug Overdose Deaths Last Year. The New York Times, New York, November 3, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- (13).National Institute on Drug Abuse (2018) Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide, Third ed., U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Vallejo R, de Leon-Casasola O, and Benyamin R (2004) Opioid Therapy and Immunosuppression. Am. J. Ther. 11, 354–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Doverty M, White JM, Somogyi AA, Bochner F, Ali R, and Ling W (2001) Hyperalgesic Responses in Methadone Maintenance Patients. Pain 90, 91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Bart G (2012) Maintenance Medication for Opiate Addiction: The Foundation of Recovery. J. Addict. Dis. 31, 207–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Feng Y, He X, Yang Y, Chao D, Lazarus H, L., and Xia Y (2012) Current Research on Opioid Receptor Function. Curr. Drug Targets 13, 230–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).van Dorp ELA, Yassen A, and Dahan A (2007) Naloxone Treatment in Opioid Addiction: The Risks and Benefits. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 6, 125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Ritter AJ (2002) Naltrexone in the Treatment of Heroin Dependence: Relationship with Depression and Risk of Overdose. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 36, 224–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Miotto K, McCann M, Basch J, Rawson R, and Ling W (2002) Naltrexone and Dysphoria: Fact or Myth? Am. J. Addict. 11, 151–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Stotts AL, Dodrill CL, and Kosten TR (2009) Opioid Dependence Treatment: Options in Pharmacotherapy. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 10, 1727–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Volkow ND, and Collins FS (2017) The Role of Science in the Opioid Crisis. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 391–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Volkow ND, Woodcock J, Compton WM, Throckmorton DC, Skolnick P, Hertz S, and Wargo EM (2018) Medication Development in Opioid Addiction: Meaningful Clinical End Points. Sci. Transl. Med. 10, eaan2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Collins FS, Koroshetz WJ, and Volkow ND (2018) Helping to End Addiction Over the Long-Term. JAMA 320, 129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Dhawan BN, Cesselin F, Raghubir R, Reisine T, Bradley PB, Portoghese PS, and Hamon AM (1996) International Union of Pharmacology. XII. Classification of Opioid Receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 48, 567–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Stevens CW (2015) Bioinformatics and Evolution of Vertebrate Nociceptin and Opioid Receptors. Vitam. Horm. 97, 57–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Mansour A, Fox CA, Akil H, and Watson SJ (1995) Opioid-Receptor MRNA Expression in the Rat CNS: Anatomical and Functional Implications. Trends Neurosci. 18, 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Peng J, Sarkar S, and Chang SL (2012) Opioid Receptor Expression in Human Brain and Peripheral Tissues Using Absolute Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR. Drug Alcohol Depend. 124, 223–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Agirregoitia E, Peralta L, Mendoza R, Expósito A, Ereño ED, Matorras R, and Agirregoitia N (2012) Expression and Localization of Opioid Receptors during the Maturation of Human Oocytes. Reprod. BioMed. Online 24, 550–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Márki Á, Monory K, Ötvös F, Tóth G, Krassnig R, Schmidhammer H, Traynor JR, Roques BP, Maldonado R, and Borsodi A (1999) μ-Opioid Receptor Specific Antagonist Cyprodime: Characterization by In Vitro Radioligand and [35S]GTPγS Binding Assays. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 383, 209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Burke TF, Woods JH, Lewis JW, and Medzihradsky F (1994) Irreversible Opioid Antagonist Effects of Clocinnamox on Opioid Analgesia and Mu Receptor Binding in Mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 271, 715–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Hawkins KN, Knapp RJ, Lui GK, Gulya K, Kazmierski W, Wan YP, Pelton JT, Hruby VJ, and Yamamura HI (1989) [3H]-[H-D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Orn-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2] ([3H]-CTOP), a Potent and Highly Selective Peptide for Mu Opioid Receptors in Rat Brain. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 248, 73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Kramer TH, Shook JE, Kazmierski W, Ayres EA, Wire WS, Hruby VJ, and Burks TF (1989) Novel Peptidic Mu Opioid Antagonists: Pharmacologic Characterization In Vitro and In Vivo. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 249, 544–551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Abbruscato TJ, Thomas SA, Hruby VJ, and Davis TP (1997) Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability and Bioavailability of a Highly Potent and Mu-Selective Opioid Receptor Antagonist, CTAP: Comparison with Morphine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 280, 402–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Li G, Aschenbach LC, Chen J, Cassidy MP, Stevens DL, Gabra BH, Selley DE, Dewey WL, Westkaemper RB, and Zhang Y (2009) Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of 6alpha- and 6beta-N-Heterocyclic Substituted Naltrexamine Derivatives as Mu Opioid Receptor Selective Antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 52, 1416–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Yuan Y, Li G, He H, Stevens DL, Kozak P, Scoggins KL, Mitra P, Gerk PM, Selley DE, Dewey WL, and Zhang Y (2011) Characterization of 6α- and 6β-N-Heterocyclic Substituted Naltrexamine Derivatives as Novel Leads to Development of Mu Opioid Receptor Selective Antagonists. ACS Chem. Neurosci 2, 346–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Mitra P, Venitz J, Yuan Y, Zhang Y, and Gerk PM (2011) Preclinical Disposition (In Vitro) of Novel μ-Opioid Receptor Selective Antagonists. Drug Metab. Dispos. 39, 1589–1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Obeng S, Yuan Y, Jali A, Selley DE, and Zhang Y (2018) In Vitro and In Vivo Functional Profile Characterization of 17-Cyclopropylmethyl-3,14β-Dihydroxy-4,5α-Epoxy-6α-(Isoquinoline-3-Carboxamido)Morphinan (NAQ) as a Low Efficacy Mu Opioid Receptor Modulator. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 827, 32–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Siemian JN, Obeng S, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, and Li J-X (2016) Antinociceptive Interactions between the Imidazoline I2 Receptor Agonist 2-BFI and Opioids in Rats: Role of Efficacy at the μ-Opioid Receptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 357, 509–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Cornelissen JC, Obeng S, Rice KC, Zhang Y, Negus SS, and Banks ML (2018) Application of Receptor Theory to the Design and Use of Fixed-Proportion Mu-Opioid Agonist and Antagonist Mixtures in Rhesus Monkeys. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 365, 37–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Altarifi AA, Yuan Y, Zhang Y, Selley DE, and Negus SS (2015) Effects of the Novel, Selective and Low-Efficacy Mu Opioid Receptor Ligand NAQ on Intracranial Self-Stimulation in Rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 232, 815–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Obeng S, Wang H, Jali A, Stevens DL, Akbarali HI, Dewey WL, Selley DE, and Zhang Y (2018) Structure–Activity Relationship Studies of 6α- and 6β-Indolylacetamidonaltrexamine Derivatives as Bitopic Mu Opioid Receptor Modulators and Elaboration of the “Message-Address Concept” To Comprehend Their Functional Conversion. ACS Chem. Neurosci, DOI: 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Mohr K, Schmitz J, Schrage R, Tränkle C, and Holzgrabe U (2013) Molecular Alliance-From Orthosteric and Allosteric Ligands to Dualsteric/Bitopic Agonists at G Protein Coupled Receptors. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 52, 508–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Fronik P, Gaiser BI, and Sejer Pedersen D (2017) Bitopic Ligands and Metastable Binding Sites: Opportunities for G Protein-Coupled Receptor (GPCR) Medicinal Chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 60, 4126–4134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Selley DE, Liu Q, and Childers SR (1998) Signal Transduction Correlates of Mu Opioid Agonist Intrinsic Efficacy: Receptor-Stimulated [35S]GTPγS Binding in MMOR-CHO Cells and Rat Thalamus. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 285, 496–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Selley DE, Cao CC, Liu Q, and Childers SR (2000) Effects of Sodium on Agonist Efficacy for G-Protein Activation in Mu-Opioid Receptor-Transfected CHO Cells and Rat Thalamus. Br. J. Pharmacol 130, 987–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Childers SR, and Snyder SH (1978) Guanine Nucleotides Differentiate Agonist and Antagonist Interactions with Opiate Receptors. Life Sci. 23, 759–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Snyder SH, Pert CB, and Pasternak GW (1974) The Opiate Receptor. Ann. Intern. Med. 81, 534–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Yuan Y, Zaidi SA, Stevens DL, Scoggins KL, Mosier PD, Kellogg GE, Dewey WL, Selley DE, and Zhang Y (2015) Design, Syntheses, and Pharmacological Characterization of 17-Cyclopropylmethyl-3,14β-Dihydroxy-4,5α-Epoxy-6α-(Isoquinoline-1 3′-Carboxamido)Morphinan Analogues as Opioid Receptor Ligands. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 23, 1701–1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).White KL, Robinson JE, Zhu H, DiBerto JF, Polepally PR, Zjawiony JK, Nichols DE, Malanga CJ, and Roth BL (2015) The G Protein-Biased κ-Opioid Receptor Agonist RB-64 is Analgesic with a Unique Spectrum of Activities in Vivo. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 352, 98–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Land BB, Bruchas MR, Lemos JC, Xu M, Melief EJ, and Chavkin C (2008) The Dysphoric Component of Stress is Encoded by Activation of the Dynorphin Kappa-Opioid System. J. Neurosci. 28, 407–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Perrine SA, Hoshaw BA, and Unterwald EM (2006) Delta Opioid Receptor Ligands Modulate Anxiety-like Behaviors in the Rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 147, 864–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Jutkiewicz EM, Baladi MG, Folk JE, Rice KC, and Woods JH (2006) The Convulsive and Electroencephalographic Changes Produced by Nonpeptidic Delta-Opioid Agonists in Rats: Comparison with Pentylenetetrazol. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 317, 1337–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Günther T, Dasgupta P, Mann A, Miess E, Kliewer A, Fritzwanker S, Steinborn R, and Schulz S (2018) Targeting Multiple Opioid Receptors - Improved Analgesics with Reduced Side Effects? Br. J. Pharmacol. 175, 2857–2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Olson KM, Lei W, Keresztes A, Lavigne J, and Streicher JM (2017) Novel Molecular Strategies and Targets for Opioid Drug Discovery for the Treatment of Chronic Pain. Yale J. Biol. Med. 90, 97–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Shippenberg TS, Zapata A, and Chefer VI (2007) Dynorphin and the Pathophysiology of Drug Addiction. Pharmacol. Ther. 116, 306–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Resnick RB, Kestenbaum RS, Washton A, and Poole D (1977) Naloxone-Precipitated Withdrawal: A Method for Rapid Induction onto Naltrexone. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 21, 409–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Charney DS, Eugene Redmond D, Galloway MP, Kleber HD, Heninger GR, Murberg M, and Roth RH (1984) Naltrexone Precipitated Opiate Withdrawal in Methadone Addicted Human Subjects: Evidence for Noradrenergic Hyperactivity. Life Sci. 35, 1263–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Wightman RS, Nelson LS, Lee JD, Fox LM, and Smith SW (2018) Severe Opioid Withdrawal Precipitated by Vivitrol®. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 36, 1128.e1–1128.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Kieffer BL (1999) Opioids: First Lessons from Knockout Mice. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 20, 19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Bailey CP, Llorente J, Gabra BH, Smith FL, Dewey WL, Kelly E, and Henderson G (2009) Role of Protein Kinase C and μ-Opioid Receptor (MOPr) Desensitization in Tolerance to Morphine in Rat Locus Coeruleus Neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 29, 307–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Christie MJ (2008) Cellular Neuroadaptations to Chronic Opioids: Tolerance, Withdrawal and Addiction. Br. J. Pharmacol. 154, 384–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Swedberg MDB, and Giarola A (2015) Drug Discrimination: Use in Preclinical Assessment of Abuse Liability. Nonclinical Assess. Abus. Potential New Pharm, 129–149. [Google Scholar]

- (64).Altarifi AA, Yuan Y, Zhang Y, Selley DE, and Negus SS (2015) Effects of the Novel, Selective and Low-Efficacy Mu Opioid Receptor Ligand NAQ on Intracranial Self-Stimulation in Rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 232, 815–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Manglik A, Kruse AC, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Mathiesen JM, Sunahara RK, Pardo L, Weis WI, Kobilka BK, and Granier S (2012) Crystal Structure of the M-Opioid Receptor Bound to a Morphinan Antagonist. Nature 485, 321–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Che T, Majumdar S, Zaidi SA, Ondachi P, McCorvy JD, Wang S, Mosier PD, Uprety R, Vardy E, Krumm BE, Han GW, et al. (2018) Structure of the Nanobody-Stabilized Active State of the Kappa Opioid Receptor. Cell 172, 55–67. e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Granier S, Manglik A, Kruse AC, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Weis WI, and Kobilka BK (2012) Structure of the δ-Opioid Receptor Bound to Naltrindole. Nature 485, 400–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Wang J, Hou T, and Xu X (2006) Recent Advances in Free Energy Calculations with a Combination of Molecular Mechanics and Continuum Models. Curr. Comput.-Aided Drug Des 2, 287–306. [Google Scholar]

- (69).Gohlke H, Kiel C, and Case DA (2003) Insights into Protein–Protein Binding by Binding Free Energy Calculation and Free Energy Decomposition for the Ras–Raf and Ras–RalGDS Complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 330, 891–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Hou T, McLaughlin W, Lu B, Chen K, and Wang W (2006) Prediction of Binding Affinities between the Human Amphiphysin-1 SH3 Domain and its Peptide Ligands Using Homology Modeling, Molecular Dynamics and Molecular Field Analysis. J. Proteome Res. 5, 32–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Zheng Y, Obeng S, Wang H, Stevens DL, Komla E, Selley DE, Dewey WL, Akbarali HI, and Zhang Y (2018) Methylation Products of 6β-N-Heterocyclic Substituted Naltrexamine Derivatives as Potential Peripheral Opioid Receptor Modulators. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 9, 3028–3037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Wang H, Zaidi SA, and Zhang Y (2017) Binding Mode Analyses of NAP Derivatives as Mu Opioid Receptor Selective Ligands through Docking Studies and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 25, 2463–2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Zaidi SA, Arnatt CK, He H, Selley DE, Mosier PD, Kellogg GE, and Zhang Y (2013) Binding Mode Characterization of 6α- and 6β-N-Heterocyclic Substituted Naltrexamine Derivatives via Docking in Opioid Receptor Crystal Structures and Site-Directed Mutagenesis Studies: Application of the ‘Message–address’ Concept in Development of Mu Opio. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 21, 6405–6413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Huang P, Kehner GB, Cowan A, and Liu-Chen LY (2001) Comparison of Pharmacological Activities of Buprenorphine and Norbuprenorphine: Norbuprenorphine Is a Potent Opioid Agonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 297, 688–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).National Research Council (2011) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th ed., National Academies Press, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- (76).Solinas M, Panlilio LV, Justinova Z, Yasar S, and Goldberg SR (2006) Using Drug-Discrimination Techniques to Study the Abuse-Related Effects of Psychoactive Drugs in Rats. Nat. Protoc. 1, 1194–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Jones G, Willett P, Glen RC, Leach AR, and Taylor R (1997) Development and Validation of a Genetic Algorithm for Flexible Docking. J. Mol. Biol. 267, 727–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Jones G, Willett P, and Glen RC (1995) Molecular Recognition of Receptor Sites Using a Genetic Algorithm with a Description of Desolvation. J. Mol. Biol. 245, 43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Humphrey W, Dalke A, and Schulten K (1996) VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics. J. Mol. Graphics 14, 33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Vanommeslaeghe K, Hatcher E, Acharya C, Kundu S, Zhong S, Shim J, Darian E, Guvench O, Lopes P, Vorobyov I, et al. (2009) CHARMM General Force Field: A Force Field for Drug-like Molecules Compatible with the CHARMM All-Atom Additive Biological Force Fields. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 671–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Vanommeslaeghe K, Raman EP, and MacKerell AD (2012) Automation of the CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) II: Assignment of Bonded Parameters and Partial Atomic Charges. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 52, 3155–3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Vanommeslaeghe K, and MacKerell AD (2012) Automation of the CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) I: Bond Perception and Atom Typing. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 52, 3144–3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (83).MacKerell AD, Bashford D, Bellott M, Dunbrack RL, Evanseck JD, Field MJ, Fischer S, Gao J, Guo H, Ha S, et al. (1998) All-Atom Empirical Potential for Molecular Modeling and Dynamics Studies of Proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 3586–3616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).MacKerell AD, Feig M, and Brooks CL (2004) Improved Treatment of the Protein Backbone in Empirical Force Fields. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 698–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).Klauda JB, Venable RM, Freites JA, O’Connor JW, Tobias DJ, Mondragon-Ramirez C, Vorobyov I, MacKerell AD, and Pastor RW (2010) Update of the CHARMM All-Atom Additive Force Field for Lipids: Validation on Six Lipid Types. J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 7830–7843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kalé L, and Schulten K (2005) Scalable Molecular Dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1781–1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.