Abstract

Introduction:

Second trimester asymptomatic cervical dilation is significant risk factor for early preterm birth. The objective of this study is to evaluate whether transvaginal ultrasound cervical length (CL) predicts asymptomatic cervical dilation on physical exam in women with short cervix (CL≤25mm) and no prior preterm birth.

Material and methods:

Secondary analysis of a randomized trial on pessary in asymptomatic singletons without prior preterm birth diagnosed with CL≤25mm between 18 0/7– 23 6/7 weeks. Participants had transvaginal ultrasound and physical cervical exam and were randomized to pessary or no pessary with all patients with cervical length≤20mm offered vaginal progesterone. The primary outcome was to determine whether CL was predictive of asymptomatic physical cervical dilation ≥1cm using receiver operating characteristic curve.

Results:

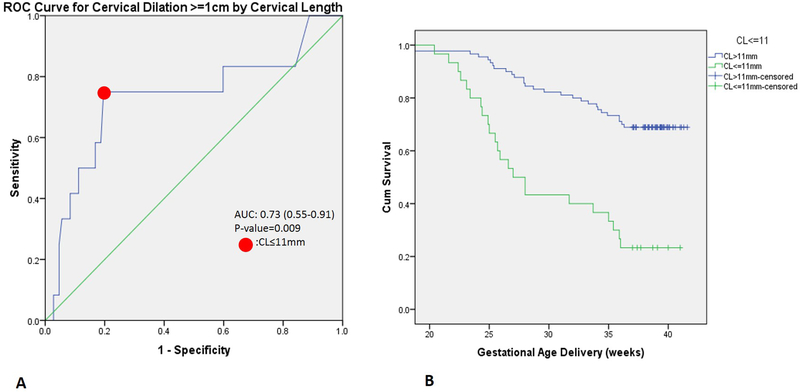

One-hundred-nineteen women were included. Based on receiver operating characteristic curve, CL ≤11mm was best predictive of cervical dilation ≥1cm, with 75% sensitivity, 80% specificity, and area under the curve 0.73(0.55–0.91), p=0.009. Cervical length ≤11mm had increased incidence of cervical dilation ≥1cm on physical exam (30% vs 3%, odds ratio 12.29 (3.05 to 49.37) p<0.001) with a negative predictive value of 97%. Patients with ≥1cm dilation had increased preterm birth <37 weeks (75% vs 39%, p=0.03) compared to those not dilated. Women with a CL ≤11mm had increased preterm birth <37 weeks (77% vs 31%, p<0.001), preterm birth <34 weeks (63% vs 22%, p<0.001), and lower birthweight (1552±1047 vs 2560±1072g, p<0.001) compared to women with CL >11mm.

Conclusions:

Among singletons without prior preterm birth diagnosed with short cervix (≤25mm), CL ≤11mm may identify a subgroup of patients at high risk for asymptomatic cervical dilation and poor perinatal outcome. Physical exam should be considered and adjunctive preterm birth prevention measures should be studied in singletons with CL≤11mm.

Keywords: Cervical length, short cervix, transvaginal ultrasound, preterm birth, advanced cervical dilation

INTRODUCTION

Preterm birth is a leading cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality, with earlier gestational age correlated with increased morbidity and mortality(1). However, our ability to predict and prevent preterm birth remains limited, especially in women without a history of prior preterm birth. A short cervix ≤25mm is a known risk factor for early preterm birth (<34 weeks), and vaginal progesterone has been shown to reduce this risk(2–6), although it is not universally effective. A recent study demonstrated that of women delivered preterm with no history of prior preterm birth, a short cervix in the second trimester was associated with a significantly increased risk of very early preterm birth (<28weeks) compared to those with normal cervical length(7). Another recent study suggested that vaginal progesterone may not be as effective in preventing preterm birth in women with a very short cervix (<15mm) compared to women with a cervical length (CL) of 15–20 mm,(8) and a recent meta-analysis did not find a significant reduction in preterm birth<33 weeks in the subgroup of women with cervical length<10mm treated with vaginal progesterone versus placebo(9). Cervical dilation is an independent risk factor of preterm birth, for which a cerclage, rather than progesterone alone, may be recommended to reduce risk of preterm birth in women with singleton gestations(10).

Given the risk of preterm birth associated with short cervix and the benefit of vaginal progesterone in this setting, mid-trimester universal transvaginal ultrasound (TVU) CL screening has been suggested as a useful tool for preterm birth prevention in women without a history of prior preterm birth(5,11,12). However, beyond ultrasound screening, there is no current recommendation for physical exam for assessment of cervical dilation in the setting of an asymptomatic short cervix despite the fact that women with asymptomatic cervical dilation may benefit from cerclage placement(10,13–15). Advanced cervical dilation has varied by study, but the largest prospective cohort study15 defined it as cervical dilation ≥1cm and found benefit with cerclage in this setting. Given the high risk of early preterm birth in women with a short cervix even with progesterone therapy, we sought to assess whether there is a TVU CL below which women are at increased risk for asymptomatic cervical dilation. This would suggest a CL cut off for which a physical exam should be conducted to identify asymptomatic cervical dilation, identifying patients who may benefit from further study of adjunctive interventions such as cerclage.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This is a planned secondary analysis of the Prevention of Preterm birth with Pessary in Singletons trial (PoPPS trial) which was aimed to determine if pessary use prevents preterm birth in singleton gestations with a short TVU CL and without a prior spontaneous preterm birth(16). The parent trial was Institutional Review Board approved and only deidentified data was used in this secondary analysis. The primary study was powered for the primary outcome of preterm birth and not for this planned secondary analysis. Inclusion criteria included singleton pregnancy, 18 0/7 – 23 6/7 weeks with CL ≤25mm and no prior spontaneous preterm birth. Exclusion criteria included any sign/symptom of preterm labor, rupture of membranes, abruption, or chorioamnionitis, vaginal bleeding, lethal structural congenital anomaly, chromosomal anomaly, ballooning of membraes into the cervix or CL=0mm, painful regular contractions, or placenta previa. In the parent trial 17,383 patients were screened, 2.4% (N=422) were diagnosed with short cervix ≤25mm and 122 agreed to randomization to pessary or no pessary and all patients with CL ≤20mm were offered vaginal progesterone. Transvaginal ultrasound CL assessments were performed by CLEAR certified sonographers (clear.perinatalquality.org) using CLEAR criteria of the Perinatal Quality Foundation(17) and reviewed by Maternal Fetal Medicine attending physicians. In addition to CL measurement, the presence or absence of funneling and sludge was also documented. Women with a TVU CL ≤25mm at 180–236 weeks gestation were randomized to receive the Bioteque cup pessary or no pessary. Treatment with vaginal progesterone was recommended to women with a TVU CL ≤20mm. After randomization study subjects underwent a physical manual cervical exam to assess the Bishop score from which cervical dilation was assessed for this secondary analysis. As part of the Bishop score, cervical dilation of the internal os was assigned a value 0 to 2, with 0=closed, 1= 1–2cm dilated, and 2= 3–4 cm dilated(16). Physical exam was performed by selected investigators trained in pessary placement and standardized reporting of cervical exam; examiners were not blinded to CL result and exam was performed after ultrasound and prior to any treatment initiation. Sterile speculum exam, vaginal swab for infection, and additional testing such as amniocentesis, or serum markers to evaluate for chorioamnionitis were not routinely performed as part of the study protocol. Management of patients noted to have cervical dilation on physical exam and use of cerclage was determined by individual providers, and was not dictated by the study protocol. The outcome of the trial did not find a significant difference in preterm birth rate with pessary use although the trial was stopped early due to the fact that the two primary recruiting sites would be unable to continue to enroll subjects in this trial, given precedence of a competing National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Unit Network (MFMU) pessary trial after their entrance into the NICHD MFMU Network.

Statistical Analyses

The primary outcome was to determine whether CL was predictive of asymptomatic physical cervical dilation ≥1cm with receiver operating characteristic curve. CL cut-off was determined by the point on the receiver operating characteristic curve that maximized the Youden index (sensitivity + specificity – 1). Increased risk of physical cervical dilation >=1cm based on TVU CL cut-off was measured by incidence and odds ratio (OR). Secondary outcomes included perinatal outcomes: gestational age at delivery, incidence of preterm birth <37 and <34 weeks, Kaplan Meier survival curve with log rank analysis for preterm birth<37 week, and birthweight, were all compared by CL. Additionally, we examined the correlation of funneling and amniotic sludge on ultrasound with physical cervical dilation as well as the correlation between TVU CL and other parts of the Bishop score with Pearson correlation coefficient. Baseline characteristics including demographic characteristics and obstetric and gynecologic history was also collected and compared. Continuous variables were compared using the t-test or Mann Whitney U test for nonparametric variables and categorical variables with chi-square analysis/Fishers exact as appropriate. P<0.05 was considered significant. Missing data was excluded in pair wise fashion. SPSS v 23.0 (IBM SPSS, Armonk, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Given the use of vaginal progesterone and pessary in this study, planned subgroup analysis was done in these subgroups for perinatal outcomes. The use of vaginal progesterone and/or pessary does not affect the primary outcome of physical dilation at the time of CL ultrasound thus subgroup analysis for primary outcome not performed.

Ethical Approval

The parent randomized controlled trial was Institutional Review Board approved and registered in clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02056652)(16). This secondary analysis utilized de-identified data and is Institutional Review Board exempt under 45 CFR 46.101(b).4.

RESULTS

Of 122 women randomized in the trial, 119 had both a TVU CL measurement and a physical cervical dilatation documented. Of the 119 women, 12 (10%) had a cervical dilation ≥1cm, and none had cervical dilation ≥3cm. Descriptive characteristics of patients who were dilated available in Table 3/Supplement. ROC curve demonstrated that a TVU CL ≤11mm was best predictive of cervical dilation ≥1cm in otherwise asymptomatic women with a sensitivity of 75%, specificity of 80%, with an area under the curve of 0.73 (95% confidence interval; 0.55 to 0.91, P=0.009) (Figure1A). Positive predictive value of CL ≤11mm for asymptomatic cervical dilation was 30%, negative predictive value was 97%.

Table 3:

Descriptive characteristics of patients who were dilated.

| Age | BMI(kg/m2) | Race | GA at diagnosis | Cervical length (mm) | Pessary | Vaginal Progesterone | Cerclage | GA at delivery | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25.6 | 25.6 | Black/AA | 20.4 | 11 | No | Yes | No | 27 |

| 2 | 29.4 | 29.4 | Mixed | 20.3 | 1.23 | No | Yes | No | 35.4 |

| 3 | 46.7 | 23.4 | White/Caucasian | 20.6 | 3.2 | Yes | Yes | No | 22.4 |

| 4 | 40 | 23 | Black/AA | 22.1 | 9.8 | No | N/A | No | 39.1 |

| 5 | 26.2 | 27.7 | Black/AA | 19.9 | 3.2 | Yes | Yes | No | 24.9 |

| 6 | 25.5 | 39.8 | Black/AA | 21.6 | 7.5 | Yes | Yes | No | 23.4 |

| 7 | 20.9 | 20.1 | Black/AA | 20.1 | 20.2 | No | N/A | No | 36.1 |

| 8 | 29 | 22.3 | Black/AA | 20.9 | 4 | No | N/A | Yes | 23.1 |

| 9 | 24.6 | 26 | Black/AA | 20.9 | 23 | Yes | No | No | 26.4 |

| 10 | 26.3 | 26.9 | Black/AA | 23 | 23 | Yes | No | No | 38.1 |

| 11 | 30.2 | 22.3 | Black/AA | 21.6 | 11 | Yes | Yes | No | 37.7 |

| 12 | 32.9 | 21.3 | White/Caucasian | 19.9 | 5 | No | No | Yes | 35 |

AA: African American; BMI: body mass index; GA: gestational age; N/A data not available.

Figure 1.

A: Receiver operating characteristic curve for physical cervical dilation ≥1cm by cervical length (mm) in women diagnosed with short cervix (≤25mm). Area under the curve of 0.73 (95% CI 0.55–0.91), p=.009.

B: Kaplan Meier curve for preterm birth <37 weeks by cervical length >11mm versus ≤11mm in women diagnosed with short cervix (≤25mm),Mantel-Cox log rank p<.001. Data censored after 37 weeks.

Demographic/obstetric characteristics between women with a TVU CL >11mm vs ≤11mm were similar except vaginal progesterone use was more common in those with CL ≤11mm than >11mm (95% vs 48%, P<0.001) (Table 1). Roughly half the women in each group had a pessary placed and 10% (3 of 30) of women with a TVU CL ≤11mm had a cerclage versus 2% (2 of 92) of those with CL>11mm (P=0.09). A TVU CL ≤11mm was associated with an increased incidence of cervical dilation ≥1cm (30% vs 3%, P<0.001) with an OR of 12.29 (3.05–49.37) compared to a TVU CL >11mm.

Table 1:

Comparison of demographic characteristics, obstetric/medical history, current pregnancy complications, and perinatal outcomes between women without prior preterm birth (PTB) diagnosed with short cervix (≤25mm) with cervical length >11mm versus ≤11mm. Data presented as N(%) or mean (± standard deviation) or median (interquartile range).

| Cervical length >11mm (N=89) |

Cervical length ≤11mm (N=30) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEMOGRAPHICS | |||

| Maternal Age (years) | 28.8±6.1 | 29.2±6.9 | 0.73 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.6±6.5 | 26.4±5.3 | 0.87 |

| GA at ultrasound (weeks) | 21.1±1.2 | 20.1±1.1 | 0.60 |

| Non-Hispanic | 80 (90) | 28 (93) | |

| More than one | 2 (2) | 1 (3) | |

| Current tobacco use | 6 (7) | 0 (0) | 0.20 |

| Current alcohol use | 10 (11) | 3 (10) | 1.0 |

| Cocaine or heroin use | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0.25 |

| OBSTETRICS HISTORY | |||

| Prior full term delivery | 32 (36) | 9 (30) | 0.52 |

| Prior D&E for miscarriage or abortion | 49 (55) | 18 (60) | 0.30 |

| History of cervical surgery | 10 (11) | 5 (17) | 0.70 |

| Known uterine anomaly | 3 (3) | 3 (10) | 0.16 |

| CURRENT PREGNANCY | |||

| Pessary | 44 (49) | 16 (53) | 0.83 |

| Cerclage | 2 (2) | 3 (10) | 0.09 |

| Vaginal Progesteronea | 30/62 (48) | 19/20 (95) | <0.001 |

| OUTCOMES | |||

| Physical cervical dilation ≥1cm | 3 (3) | 9 (30) | <0.001 |

| GA of delivery (week) | 38.4 [34.9–39.4] | 27.0 [23.3–36.5] | <0.001 |

| PTB<37 weeks | 27 (31) | 23 (77) | <0.001 |

| PTB<34 weeks | 19 (22) | 19 (63) | <0.001 |

| Birthweight (g) | 3020 [2310–3335] | 670 [480–2780] | <0.001 |

Vaginal progesterone use not uniformly documented, N=82.

BMI: body mass index; GA: gestational age; D&E: dilation and evacuation.

Regarding perinatal outcomes, women with a TVU CL ≤11mm had a lower mean gestational age at delivery (29.9±6.6 vs 35.6±7.2wks, P<0.001), increased incidence of preterm birth <37 weeks (77% vs 31%, P<0.001), preterm birth <34 weeks (63% vs 22%, P<0.001), and lower mean birth weight (1552±1047.3 vs 2560.4±1072.4g, P<0.001) (Table 1) compared with women with a TVU CL >11mm. Kaplan Meier survival curve demonstrated a significant difference in gestation between those with CL >11m versus ≤11mm (Mantel-cox log rank, P<0.001), of particular note 50% of those with CL ≤11mm delivered <27 weeks compared to ~10% of those with CL >11mm (Figure 1B).

Regarding subgroup analyses, women with a TVU CL ≤11mm had a lower mean gestational age at delivery even in the subgroup of women treated with pessary (30.7±6.3 vs 36.3±4.5, P=0.004) and women treated with vaginal progesterone (30.4±6.1 vs 36.1±4.8, P=0.002).

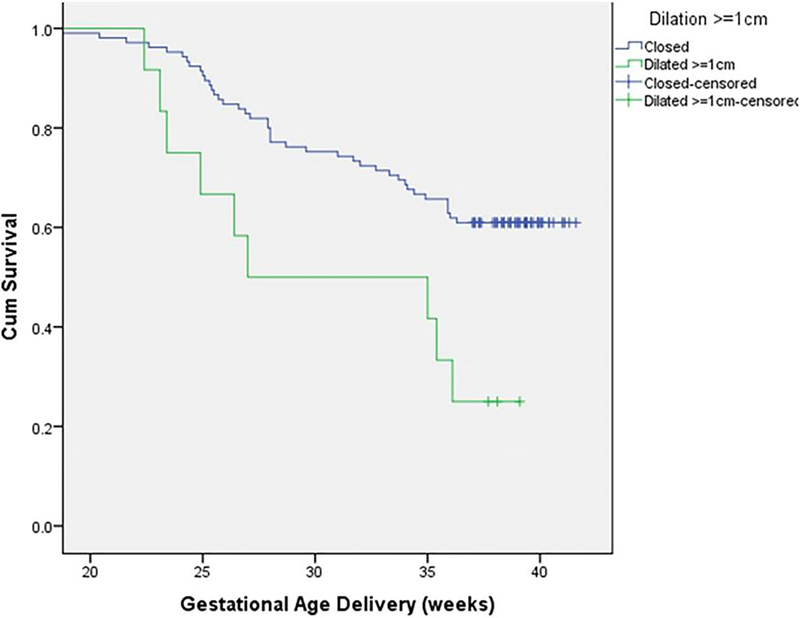

Table 2 reports baseline characteristics and outcomes of women with short cervix (≤25mm) who were versus were not dilated, baseline demographic and obstetric characteristics were similar between groups. Women with ≥1cm dilation had an increased risk of preterm birth <37 weeks (75% vs 39%, OR 4.68 (1.2–18.3) P=0.03) compared to those not dilated. Kaplan Meier survival curve demonstrated a significant difference in latency between those with cervical dilation≥1cm versus <1cm with 50% of those dilated delivering <28 weeks and over 50% of those undilated delivering at term (Mantel-cox log rank, P<0.001) (Figure 2).

Table 2:

Comparison of demographic characteristics, obstetric/medical history, current pregnancy complications, and perinatal outcomes between women without prior preterm birth (PTB) diagnosed with short cervix (≤25mm) with no physical cervical dilation versus cervical dilation ≥1cm. Data presented as N(%) or mean (± standard deviation) or median [interquartile range].

| No Physical Cervical Dilation (N=107) |

Physical Cervical Dilation ≥1cm (N=12) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEMOGRAPHICS | |||

| Maternal Age (years) | 28.8±6.2 | 29.8±7.2 | 0.68 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.7±6.3 | 25.7±5.3 | 0.58 |

| GA at ultrasound (weeks) | 21.0±1.2 | 21.0±1.0 | 0.78 |

| Non-Hispanic | 94 (90) | 11 (92) | |

| More than one | 2 (2) | 1 (8) | |

| Current tobacco use | 6 (6) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| Current alcohol use | 12 (11) | 0 (0) | 0.60 |

| Cocaine or heroin use | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| OBSTETRICS HISTORY | |||

| Prior full term delivery | 36 (34) | 5 (42) | 0.60 |

| Prior D&E for miscarriage or abortion | 61 (57) | 6 (50) | 0.65 |

| History of cervical surgery | 13 (12) | 2 (17) | 0.86 |

| Known uterine anomaly | 5 (5) | 1 (8) | 0.48 |

| CURRENT PREGNANCY | |||

| Pessary | 54 (50) | 6 (50) | 0.97 |

| Cerclage | 3 (3) | 2 (17) | 0.08 |

| Vaginal Progesteronea | 43/73 (59) | 6/9 (67) | 0.65 |

| OUTCOMES | |||

| GA of delivery (week) | 38 [31.2–39.4] | 31 [23.8–37.3] | 0.13 |

| PTB<37 weeks | 41 (39) | 9 (75) | 0.03 |

| PTB<34 weeks | 32 (31) | 6 (50) | 0.17 |

| Birthweight (g) | 2807 [1360–3253] | 654 [460–2775] | 0.13 |

Vaginal progesterone use not uniformly documented, N=82.

BMI: body mass index; GA: gestational age; D&E: dilation and evacuation;

Figure 2.

Kaplan Meier curve for preterm birth <37 weeks by cervical dilation >1cm vs <1cm in women diagnosed with short cervix (≤25mm),Mantel-Cox log rank p<.001. Data censored after 37 weeks.

Compared to women with CL>11mm without cervical dilation, women who had CL≤11mm with cervical dilation ≥1cm had a higher rate of preterm birth <37wk (78% vs 30%, OR 8.3(1.6 to 42.6), P<0.001) and preterm birth <34 wk (56% vs 21% OR 4.6 (1.1 to 18.96), P<0.001), an earlier median gestational age of delivery (27.0 [23.3 to 36.5] vs 38.4 [34.9 to 39.4], P<0.001) and lower birthweight (g) (670 [480 to 2780] vs 3020 [2310 to 3335], P<0.001). In the subgroup of only women with a very short CL≤11mm (N=30) there was no significant difference in preterm birth <37wk (78%vs 76%, P=0.9) or <34 weeks (55% vs 66%, P=0.56) between those who were dilated (N=9) vs not (N=21).

We also examined whether other ultrasound findings were correlated with physical cervical dilation. Cervical funneling (n=62) and amniotic sludge (n=28) on ultrasound were not significantly correlated with a finding of cervical dilation (r=−0.09, P=0.33 and r=−0.08, P=0.41 respectively), and were also not significantly correlated with dilation in the subgroup of women with CL ≤11mm (r=−0.43, P=0.82 and r=0, P=1.0 respectively). In looking at the relationship between TVU CL and the Bishop score, TVU CL was significantly correlated with the total Bishop score (r=−0.22, P=0.015), but in examining the components of the Bishop score, it was only correlated with cervical dilation (r=−0.29, P=0.002), and not correlated with effacement (r=−0.11, P=0.23), position (r=−.12, P=0.19) or station (r=0.07, P=0.45).

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that among patients without prior preterm birth diagnosed with short cervix (≤25mm), those with asymptomatic cervical dilation have increased risk of preterm birth, and we have identified a CL cut off that is best predictive of asymptomatic cervical dilation in this population. We suggest that identification of patients with asymptomatic cervical dilation is an important step to identifying those for whom additional preterm birth prevention interventions should be studied. Patients with a CL ≤11mm and cervical dilation had significantly worse perinatal outcomes than those with CL >11mm without cervical dilation. The inverse correlation seen between CL and risk of cervical dilation is physiologically plausible given that cervical shortening is a known prequel to preterm delivery(6), and, our study suggests, a prequel specifically to cervical dilation.

This study adds to current literature regarding ultrasound CL and preterm birth prevention. Previous studies have compared ultrasound CL to physical dilation or physical effacement and found ultrasound CL to be a more sensitive predictor of preterm birth in otherwise asymptomatic women(18–20). Another study found that in women with preexisting risk factors for preterm birth, the combination of CL <30mm and cervical dilation ≥1cm prior to 24 weeks was associated with the highest risk for preterm delivery compared to short CL or cervical dilation alone(21). Another smaller observational study similarly found a high rate of cervical dilation in women with CL ≤10mm (66%, 10/15 patients)(22). However, that study population was patients with a history of cervical dilation or preterm birth and planned cerclage, which is different from our study population, for whom cerclage is not currently indicated. Our study is unique in its sample size, population of a large number patients without prior preterm birth who develop the infrequent condition of short cervix, and identification of a TVU CL cut off associated with asymptomatic cervical dilation. We have evaluated for a number of other risk factors for short cervix and preterm birth, including prior dilation and evacuation(23,24), prior cervical surgery(25), prior term delivery, and tobacco use(26), and CL was the only significant factor associated with cervical dilation. This is noteworthy because we also demonstrate increased risk of preterm birth associated with asymptomatic cervical dilation in this already high risk group of women with short cervix (≤25mm) but no prior preterm birth, thus the identification of women with asymptomatic cervical dilation is an important step to identifying those for whom additional interventions should be studied.

While our results did not demonstrate a significant difference in preterm birth rate among patients with CL ≤11mm who were dilated versus were not dilated, the numbers in this subgroup were small and this study was not aimed or powered to examine the perinatal morbidity of advanced cervical dilation in this small subgroup. It is important to acknowledge that the use of cerclage in some of the patients with cervical dilation in this study confounds any strict interpretation of the difference in perinatal outcome of those with short cervix who were versus were not dilated and may lead to an underestimate of the perinatal morbidity with cervical dilation. Given the availability of interventions suggested to provide benefit, a control group with no intervention was not possible or ethical. This study did not assess the benefit of cerclage in setting of cervical dilation which has been documented in previous studies (10,13–15). The degree of cervical dilation used for physical exam-indicated cerclage varies by study(13) and is not defined in guidelines(10). The largest cohort study found benefit to a cerclage for those with cervical dilation ≥1cm which is the cut-off used in our study(15). Indications for a physical exam indicated cerclage include ruling out infection and abruption; enrollment in this study included evaluating for infection or abruption and patients with symptoms concerning for either were not eligible to participate.

This study has a number of strengths. While prior studies have compared ultrasound to physical exam in preterm birth prediction, this study is unique in its examination of ultrasound CL to predict asymptomatic cervical dilation and documentation of decreased latency and increased preterm birth in the subgroup of women with short cervix and asymptomatic cervical dilation. Other strengths of this study include use of data prospectively collected from a multicenter trial including a large number of women with short cervix, a relatively infrequent finding with an incidence of 1–2% in the general population(11,12,27). Additionally, although the sample size is limited, we are still able to demonstrate a clinically significant positive and negative predictive value for CL≤11mm in detection of asymptomatic cervical dilation.

This study has some limitations. Most notably, the number of patients with cervical dilation was small (N=12), thus our power to detect differences in outcome for those with very short CL and dilated versus not is limited. Second, although this was a multicenter trial, the patient population is largely African American and comes from urban tertiary care centers, thus potentially limiting the external validity of the data. Third, data on vaginal progesterone use or adherence was not consistently reported although the primary outcome, cervical dilation at time of CL ultrasound, is not affected by this limitation. Furthermore, vaginal progesterone was more common in the CL≤11mm group, and previous studies have demonstrated benefit, not harm, with vaginal progesterone in short cervix, thus it is possible the poor perinatal outcomes with very short or dilated cervix are underestimated in this study. Fourth, use of cerclage and other recommendations such as activity restriction, was provider dependent and not dictated by the trial, so management of women with a dilated cervix on exam varied, although again the benefit of cerclage in the setting of asymptomatic cervical dilation has already been demonstrated in large studies (10,13–15).

CONCLUSION

Early preterm birth is a leading cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality(1), and our study has identified a CL cut off at which physical exam may be indicated to identify asymptomatic cervical dilation, a significant risk factor for preterm birth. Based on our study approximately 10% of patients without prior preterm birth diagnosed with short cervix (≤25mm) will have asymptomatic cervical dilation and those patients with cervical dilation on physical examination are more likely to have a preterm birth. We suggest physical exam should be considered on women with CL ≤11mm to identify this high-risk subset of patients for whom studies on adjunctive interventions for preterm birth prevention are needed.

Key Message.

Among singletons without prior preterm birth diagnosed with short cervix (≤25mm), cervical length ≤11mm may identify a subgroup of patients at high risk for asymptomatic cervical dilation and poor perinatal outcome. Physical exam should be considered and adjunctive preterm birth prevention measures should be studied in singletons with cervical length ≤11mm.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Rupsa C. Boelig is supported by NIH grant T32GM008562.

Abbreviations

- CL

cervical length receiver

- TVU

transvaginal ultrasound

- OR

odds ratio

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Curtin SC, Mathews TJ. National Vital Statistics Reports Births : Final Data for 2015. Natl Vital Stat Reports. 2015;64(1):1–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hassan SS, Romero R, Vidyadhari D et al. Vaginal progesterone reduces the rate of preterm birth in women with a sonographic short cervix: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ultrasound Obs Gynecol. 2011;38(1):18–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fonseca EB, Celik E, Parra M, Singh M, Nicolaides KH. Progesterone and the risk of preterm birth among women with a short cervix. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(5):462–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romero R, Conde-Agudelo A, El-Refaie W, et al. Vaginal progesterone decreases preterm birth and neonatal morbidity and mortality in women with a twin gestation and a short cervix: an updated meta-analysis of individual patient data. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;49(3):303–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 130: prediction and prevention of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol [Internet]. 2012. October [cited 2016 Oct 27];120(4):964–73. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22996126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iams JD, Goldenberg RL, Meis PJ, et al. The Length of the Cervix and the Risk of Spontaneous Premature Delivery. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal Fetal Medicine Unit Network. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(9):567–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boelig RC, Orzechowski KM, Berghella V. Cervical length, risk factors, and delivery outcomes among women with spontaneous preterm birth. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(17):2840–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boelig RC, Villani M, Jiang E, Orzechowski K, Berghella V. Risk Factors for Early Preterm Birth in Women with Short Cervix Treated with Vaginal Progesterone In: American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Annual Clinical and Scientific Meeting. San Diego; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romero R, Conde-Agudelo A, Da Fonseca E, et al. Vaginal Progesterone for Preventing Preterm Birth and Adverse Perinatal Outcomes in Singleton Gestations with a Short Cervix: A Meta-Analysis of Individual Patient Data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(2):161–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 142: Cerclage for the Management of Cervical Insufficiency. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(2 Pt 1):372–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Son M, Grobman WA, Ayala NK, Miller ES. A universal mid-trimester transvaginal cervical length screening program and its associated reduced preterm birth rate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(3):365.e1–5.0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Temming LA, Durst JK, Tuuli MG et al. Universal cervical length screening: implementation and outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(4):523.e1–523.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ehsanipoor RM, Seligman NS, Saccone G et al. Physical Examination-Indicated Cerclage: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(1):125–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Althuisius SM, Dekker GA, Hummel P, van Geijn HP, Cervical incompetence prevention randomized cerclage trial. Cervical incompetence prevention randomized cerclage trial: emergency cerclage with bed rest versus bed rest alone. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(4):907–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pereira L, Cotter A, Gómez R, Berghella V et al. Expectant management compared with physical examination-indicated cerclage (EM-PEC) in selected women with a dilated cervix at 14(0/7)-25(6/7) weeks: results from the EM-PEC international cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol.2007;197(5):483.e1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dugoff L, Berghella V, Sehdev H, Mackeen AD, Goetzl L, Ludmir J. Prevention of preterm birth with pessary in singletons (PoPPS): a randomized controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;51(5):573–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foundation PQ. Cervical Length Education and Review (CLEAR) [Internet]. [cited 2019 Feb 1]. Available from: https://clear.perinatalquality.org/

- 18.Gomez R, Galasso M, Romero R, et al. Ultrasonographic examination of the uterine cervix is better than cervical digital examination as a predictor of the likelihood of premature delivery in patients with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171(4):956–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berghella V, Tolosa JE, Kuhlman K, Weiner S, Bolognese RJ, Wapner RJ. Cervical ultrasonography compared with manual examination as a predictor of preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177(4):723–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zlatnik FJ, Burmeister LF. Interval evaluation of the cervix for predicting pregnancy outcome and diagnosing cervical incompetence. J Reprod Med. 1993;38(5):365–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsikouras P, Galazios G, Zalvanos A, Bouzaki A, Athanasiadis A. NEW : Scott Memorial Library Article Author : BUFSP - Lending Transvaginal sonographic assessment of the cervix and preterm labor. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2007;34(3):159–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groom KM, Shennan AH, Bennett PR. Ultrasound-indicated cervical cerclage: outcome depends on preoperative cervical length and presence of visible membranes at time of cerclage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(2):445–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boelig RC, Villani M, Jiang E, Orzechowski KM, Berghella V. Prior uterine evacuation and the risk of short cervical length: a retrospective cohort study. J Ultrasound Med. 2018;37(7):1763–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saccone G, Perriera L, Berghella V. Prior uterine evacuation of pregnancy as independent risk factor for preterm birth: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(5):572–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mella MT, Mackeen AD, Gache D, Baxter JK, Berghella V. The utility of screening for historical risk factors for preterm birth in women with known second trimester cervical length. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013. ;26:710–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ananth CV, Vintzileos AM. Epidemiology of preterm birth and its clinical subtypes. 2006;19:773–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orzechowski KM, Boelig RC, Baxter JK, Berghella V. A universal transvaginal cervical length screening program for preterm birth prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(3):520–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]