Abstract

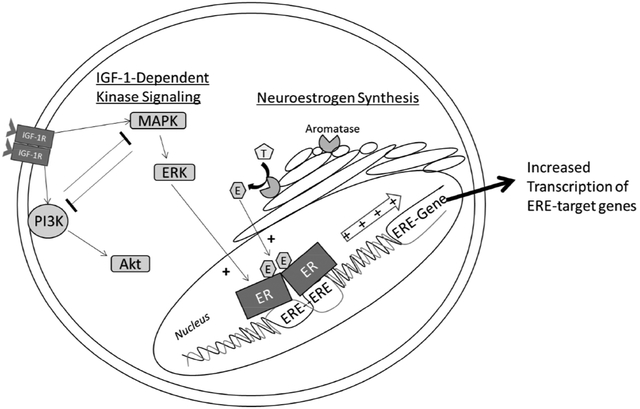

Non-canonical mechanisms of estrogen receptor activation may continue to support women’s cognitive health long after cessation of ovarian function. These mechanisms of estrogen receptor activation may include ligand-dependent actions via locally synthesized neuroestrogens and ligand-independent actions via growth factor-dependent activation of intracellular kinase cascades. We tested the hypothesis that ligand-dependent and ligand-independent mechanisms interact to activate nuclear estrogen receptors in the Neuro-2A neuroblastoma cell line in the absence of exogenous estrogens. Transcriptional output of estrogen receptors was measured following treatment with insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) in the presence of specific inhibitors for mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), phosphoinositde-3 kinase (PI3K), and neuroestrogen synthesis. Results indicate that IGF-1-dependent activation of nuclear estrogen receptors is mediated by MAPK, is opposed PI3K, and requires concomitant endogenous neuroestrogen synthesis. We conclude that both cellular signaling context and endogenous ligand availability are important modulators of ligand-independent nuclear estrogen receptor activation.

Keywords: Insulin-like growth factor-1, PI3K, MAPK, aromatase, neuroestrogens, estrogen receptor

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Regulation of estrogenic signaling in neuronal cells is canonically viewed as a prototypical nuclear hormone receptor system. Estrogenic compounds are synthesized by a distant endocrine gland, the ovaries, and secreted into the bloodstream to perfuse estrogen-sensitive target tissues throughout the body including the brain (McEwen et al. 1982). As lipophilic molecules, estrogens can penetrate the lipid membrane of target cells and diffuse to the nucleus, where they bind to and activate their prototypical nuclear hormone receptors to regulate estrogen-dependent gene expression. Nuclear estrogen receptors exhibit both ligand-dependent and ligand-independent modes of activation that are mechanistically distinct (Tora et al. 1989). Ligand-dependent activation of estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) is accomplished through concerted function of the C, D, and E domains and denoted activation function-2 (AF-2) (Webster et al. 1988). Ligand-independent activation of ERα is initiated through concerted function of the A/B and C domains and denoted activation function-1 (AF-1) (Kumar et al. 1987).

There is evidence to suggest that both that ligand-dependent and ligand-independent activation of estrogen receptors continue to occur in neuronal cells in absence of ovarian estrogens. The aromatase enzyme catalyzes the final step of estrogen synthesis, converting testosterones to estrogens (Thompson & Siiteri 1974). This enzyme is expressed in discrete regions of the primate and rodent brain including the hippocampus (Wehrenberg et al. 2001). Aromatase enzyme inhibitor treatment is detrimental to cognitive function in both post-menopausal women (Bender et al. 2015; Collins et al. 2009; Bayer et al. 2015) and ovariectomized rodents (Vierk et al. 2012; Martin et al. 2003). Furthermore, significant aromatase enzyme activity continues to occur in primary cultures of hippocampal neurons for at least 12 days in vitro (Prange-Kiel et al. 2003), functioning to maintain synaptic spine density through activation of nuclear ERα (Kretz et al. 2004; Zhou et al. 2014). Therefore, local neuroestrogen synthesis may continue to activate nuclear estrogen receptors in absence of ovarian estrogens.

Ligand-independent activation of neuronal nuclear estrogen receptors may also continue to occur in absence of ovarian estrogens. AF-1 requires intracellular kinase cascade-dependent phosphorylation of specific residues in the A/B domain of nuclear estrogen receptors (Le Goff et al. 1994; Kato et al. 1995; Bunone et al. 1996). The insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) receptor (IGF-1R) and ERα co-localize in the rodent hippocampus (Cardona-Gómez et al. 2000). The two major IGF-1R effector cascades are the phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3K) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family cascades (Kadowaki et al. 1996). Both the PI3K and MAPK cascades can regulate the transcriptional output of ERα in neuronal cells (Patrone et al. 1998; Mendez & Garcia-Segura 2006). Therefore, IGF-1R may activate nuclear estrogen receptors in neuronal cells through regulation of the PI3K or MAPK cascade.

Multiple lines of evidence indicate a reciprocally interactive relationship exists between ligand-independent kinase cascade signaling and estrogen receptor function. In hippocampal neurons, membrane-associated estrogen receptors can activate the MAPK cascade through interaction with membrane-associated metabotropic glutamate receptors (Boulware et al. 2005), resulting in enhanced hippocampus-dependent memory (Boulware et al. 2013). Likewise, estrogen-independent activation of intracellular kinase signaling can activate nuclear estrogen receptor signaling. In COS-1 renal carcinoma cells, MAPK-dependent activation of ERα was only observed in the presence of the full agonist 17-β-estradiol (17βE2), the partial agonist tamoxifen, or by genetic removal of the ligand-binding domain entirely (Tora et al. 1989; Ali et al. 1993; Kato et al. 1995). In contrast, similar experiments indicate that MAPK activation in absence of applied ligand is sufficient to activate estrogen receptors in the HeLa cervical cancer and SK-BR-3 breast cancer cell lines (Bunone et al. 1996) as well as the SK-N-BE neuroblastoma (Patrone et al. 1998) and Neuro-2A neuroblastoma cell lines (Mendez & Garcia-Segura 2006). Unlike the nonsteroidogenic COS-1 cell line (Zuber et al. 1986), the latter cell lines were derived from inherently estrogenic tissue. Both HeLa cells and neuronal cultures have since been shown to endogenously synthesize estrogenic compounds in vitro (Ishikawa et al. 2006; Prange-Kiel et al. 2003). Therefore it is possible that endogenous synthesis of estrogenic compounds in these cell lines functions to relieve inhibition from the unbound ligand-binding domain and permit estrogen receptor activation in absence of exogenously applied ligand.

Our lab has found multiple lines of evidence suggesting that both brain-derived estrogen synthesis and ligand-independent activation of nuclear estrogen receptors continue in the rodent brain in absence of any circulating ovarian or exogenously applied estrogens. We first found that increased levels of ERα in the hippocampus of ovariectomized rats enhances hippocampus-dependent memory (Rodgers et al. 2010; Witty et al. 2012), through a mechanism dependent on IGF-1R signaling (Witty et al. 2013). We have also found that intrahippocampal infusion of IGF-1 increases phosphorylation of ERα at serine-118 and expression of estrogen receptor-dependent target genes (Grissom & Daniel 2016). We have separately shown that continuous, unopposed estradiol exposure enhances hippocampus-dependent memory in ovariectomized rats through a mechanism dependent on brain-derived estradiol (Nelson et al. 2016). Finally, we have shown that significant estrogen response element (ERE)-dependent gene expression continues in the hippocampus and cortex long after ovariectomy in the transgenic ERE-LUC mouse line (Pollard et al. 2018). However, the mechanisms through which IGF-1-dependent kinase activation and ligand availability interact in neuronal cells to regulate ERE-dependent gene expression are poorly defined.

We hypothesize that both IGF-1-dependent kinase activation and locally synthesized neuroestrogens interactively regulate estrogen receptor activity in neuronal cells in the absence of exogenously applied estradiol. The Neuro-2A cell line was chosen as the model system for these studies because IGF-1-dependent regulation of nuclear estrogen receptors has already been established and has been shown to interact with the application of exogenous estradiol (Mendez & Garcia-Segura 2006). The goal of the present work is to integrate the effects of MAPK activation, PI3K activation, exogenously applied estradiol, and endogenous neuroestrogen synthesis in determining the transcriptional output of estrogen receptors in Neuro-2A cells. In a series of experiments, we determined the sequence of kinase cascade activation events that occur following IGF-1 treatment. We then determined how activation of these two kinases contributes to regulation of estrogen receptor-dependent gene transcription. We finally determined the contribution of neuroestrogen synthesis to basal and IGF-1-dependent nuclear estrogen receptor activation.

2. Methods

2.1. Experiment 1: Time-course of IGF-1-dependent activation of PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK

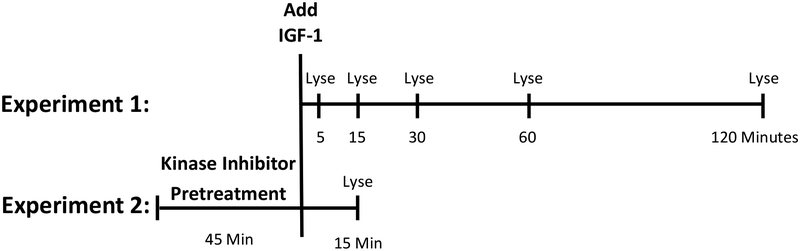

Initially we sought to observe the time-course of IGF-1-dependent activation of PI3K and MAPK in the Neuro-2A cell line. This experiment was not replicated for statistical analyses but only served to identify the optimal treatment time-point to be used in a subsequent experiment in which replication and statistical analyses would be performed. Cells were hormone starved for 24 hours and then pretreated for 45 minutes with the PI3K inhibitor, wortmannin, the MAPK inhibitor, U0126, or DMSO alone. As shown in Figure 1, cultures were then treated for zero, five, 15, 30, 60, or 120 minutes with IGF-1 and cellular protein was extracted for western blot analysis. A separate control experiment was performed in which cultures were treated with 100nM IGF-1 or vehicle alone for either 15 minutes or 24 hours before lysis. Results of this experiment are shown in Supplemental Figure 1. The relative amount of phosphorylated S473-Akt and T202/Y204 p42/44 ERK was used to quantify relative PI3K and MAPK activity, respectively.

Figure 1:

Time-lines used in western blotting experiments. In Experiment 1, IGF-1 was added to culture media and cells were lysed after five, 15, 30, 60, or 120-minute incubations. Western blotting was performed to determine the time-course of IGF-1-dependent PI3K and MAPK activation in Neuro-2A cells. In Experiment 2, the 15-minute time-point was replicated multiple times for statistical analysis. Cultures were pretreated for 45 minutes with the PI3K inhibitor, wortmannin, the MAPK inhibitor, U0126, the combination of wortmannin and U0126, or DMSO alone. Cells were then incubated with IGF-1 or its vehicle alone for 15 minutes prior to lysis. Western blotting was performed to determine the effect of PI3K and MAPK inhibition on IGF-1-dependent kinase signaling.

2.1.1. Culture Maintenance

The Neuro-2A cell line was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and cultured in growth media composed of phenol red-free 50/50 DMEM/Ham’s F12 media (Life Technologies; Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies; Carlsbad, CA), 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (5,000 units/mL of each, ThermoFisher Scientific; Waltham, MA), and 0.2% plasmocin prophylactic (2.5mg/mL, InvivoGen; San Diego, CA). Cells were grown in a sterile incubator held at 37°C and 5% carbon dioxide. The culture was passaged with a 1:3 split ratio as necessary. No culture was used for experiments after 10 passages.

2.1.2. Hormone Starvation

Cells were incubated in steroid hormone-free media comprised of phenol red-free 50/50 DMEM/Ham’s F12 media supplemented with 2% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies; Carlsbad, CA) for 24 hours prior to initiation of all treatment paradigms.

2.1.3. Kinase Inhibitor Pretreatment

The MAPK inhibitor, U0126 (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and the PI3K inhibitor, wortmannin (Sigma Aldrich; St. Louis, MO), were dissolved in DMSO. Kinase inhibitors were added directly to cell culture media to a final concentration of 10uM U0126 and 100nM wortmannin. An equal volume of DMSO was added to cultures receiving no pretreatment, resulting in a final concentration of 0.43% DMSO in all cultures during pretreatment.

2.1.4. IGF-1 treatment

IGF-1 (GroPrep, Thebarton, SA, Australia) was dissolved in 10mm HCl and added directly to the pretreated culture media to a final concentration of 100nM (Mendez & Garcia-Segura 2006). An equal volume of 10mM HCl was added vehicle-treated cultures resulting in a final concentration of 0.02mM HCl in all cultures. Vehicle-treated cultures were lysed 120 minutes after addition of vehicle and are represented by the zero-minute time-point in Figure 3. IGF-1 treated cultures were treated for five, 15, 30, 60, or 120 minutes in IGF-1 and then lysed for western blotting analysis.

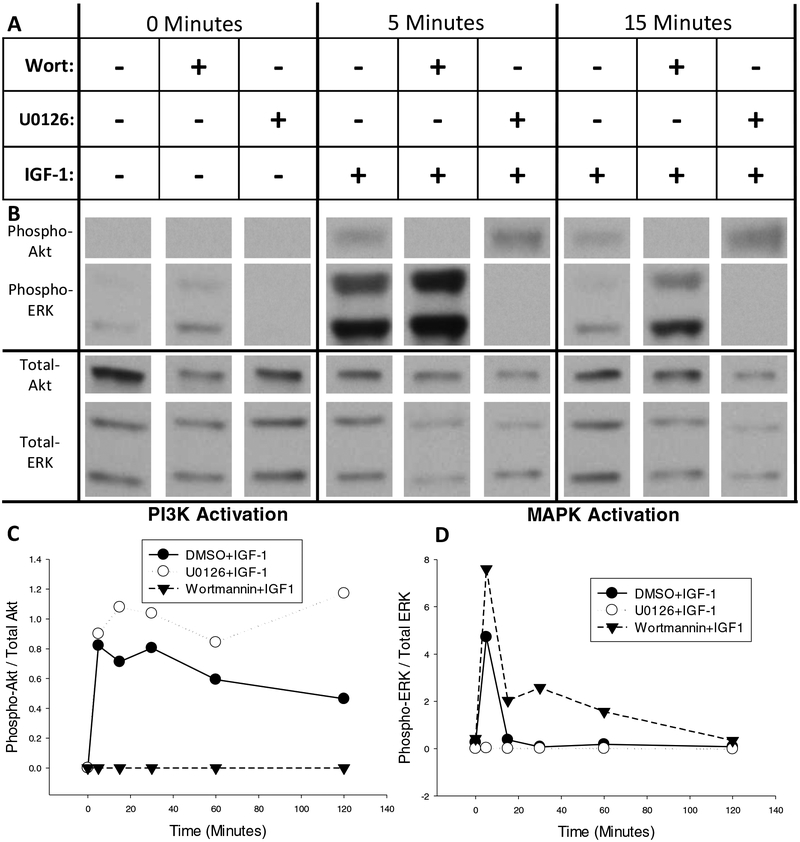

Figure 3.

Time-course of MAPK and PI3K activation after treatment with IGF-1 as determined by phosphorylation of ERK and Akt, respectively. (A) Neuro-2A cultures were pretreated for 45 minutes with the PI3K inhibitor, wortmannin, the MAPK inhibitor, U0126, or vehicle alone (0.43% DMSO). Cells were then treated for zero, five, 15, 30, 60, or 120 minutes with 100nM IGF-1. (B) Representative western blots of phosphorylated and total Akt and ERK after zero, five, or 15 minutes of IGF-1 treatment that were developed with low-sensitivity chemiluminescent substrate. (C) Quantification of Akt and (D) quantification of ERK phosphorylation over time after activation of IGF-1. + addition of drug, - omission of drug.

2.1.5. Sample Collection for Western Blotting

Cultures were lysed with the addition of ice cold lysis buffer composed of 50mM Tris-HCl, 150mM sodium chloride, 1mM EDTA, 1mM sodium orthovanadate, 10mM sodium pyrophosphate, 20mM glycerophosphate, 50mM sodium fluoride, 0.1mM PMSF, 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 1% Nonidet-P40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS. Homogenate was then centrifuged at 12,000g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and the protein concentration of each sample was determined with a Lowry Assay (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA). Lysate was mixed 1:1 with Laemmli sample loading buffer (62.5mM Tris-HCl, 2% SDS, 25% glycerol, 0.01% bromophenol blue, 350mM DTT, pH 6.8) and boiled for 8 minutes. The protein concentration of each sample was equalized with additional loading buffer and stored at −80°C.

2.1.6. Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed as described previously (Grissom & Daniel 2016) using 15ug of total protein from culture lysate. Separate blots were initially probed for either phospho-T202/Y204 p42/44 ERK (Cell Signaling 9101S; Danvers, MA) or phospho-serine 473 Akt (Cell Signaling 9271S). Blots were then stripped with Restore Stripping Buffer (Fisher Scientific; Hampton, NH) for 15 minutes at room temperature with no agitation and re-probed for either total p42/p44 ERK (Cell Signaling 9102S) or total Akt (Cell Signaling 9272S), respectively. All primary antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:5000 and visualized with the horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz sc-2004; Dallas, TX) at a dilution of 1:20,000. The presence of HRP was detected with the Enhanced Chemiluminescent Substrate (ECL) (Pierce Scientific; Waltham, MA). ECL solution was applied to blots and film was exposed to blots for increasing duration until the darkest band began to reach saturation. The optical density multiplied by the area (D×A) of western blot bands representing the proteins of interest were quantified with MCID Core imaging software (InterFocus Imaging Ltd.; Cambridge, England). Both the 44kDa and 42kDa bands of ERK showed similar patterns of phosphorylation and DxA values of both bands were summed for quantitative analysis. The D×A of phosphorylated kinase was normalized to the D×A of total kinase to obtain a quantitative value of phosphorylation.

2.2. Experiment 2: Interaction of IGF-1-dependent PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK signaling

We next sought to confirm the apparent interaction between PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK signaling following IGF-1 treatment seen in Experiment 1 through replication of the 15-minute time-point and statistical analysis. Figure 1 outlines the timeline of Experiment 2. Neuro-2A cultures were pretreated for 45 minutes with the PI3K/Akt inhibitor, wortmannin, the MAPK/ERK inhibitor, U0126, the combination of wortmannin and U0126, or DMSO alone. Cultures were then incubated with IGF-1 for 15 minutes to induce IGF-1-dependent kinase signaling. Cultures were lysed and cellular protein content was extracted from lysate to determine the relative activation of kinase cascades through western blot analysis. Culture maintenance and hormone starvation were performed as described in Section 2.1. Kinase inhibitor pretreatment was performed as described in Section 2.1.3 with an additional group pretreated with the combination of 100nM wortmannin and 10uM U0126.

2.2.1. IGF-1 Treatment

IGF-1 treatment was performed as described in Section 2.1.4. IGF-1 was added directly to pretreated culture media and an equal volume of vehicle was added to cultures that did not receive IGF-1 treatment resulting in a final concentration of 0.02mM HCl in all cultures. All cultures were lysed 15 minutes after treatment. Sample collection and western blotting were performed as described in Section 2.1 with the following exception: the presence of HRP was detected with the SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Pierce Scientific; Waltham, MA) to better quantify lower abundance bands for quantitative statistical analysis. Short film exposures were used to quantify ERK phosphorylation and IGF-1 induced phosphorylation of Akt. Longer exposures were used to quantify Akt phosphorylation in the absence of IGF-1 treatment.

2.2.2. Statistical Analysis

This experiment was independently repeated six times, with at least three sample replicates per group per repetition. Phosphorylation of ERK and Akt was quantified as described in Section 2.1.6. The calculated ratio of phosphorylated kinase to total kinase was then averaged for all replicate samples within each group and within each experiment. Average values were complied across experiments for statistical analysis with a final “n” of six. Phosphorylated Akt in the presence of wortmannin and phosphorylated ERK in the presence of U0126 were not consistently detectable by western blot and were omitted from statistical analysis. Therefore, the final analysis of ERK phosphorylation only included cultures pretreated with wortmannin or DMSO alone while the final analysis of Akt phosphorylation only included cultures pretreated with U0126 or DMSO alone. Furthermore, bands representing phosphorylated Akt after IGF-1 treatment could not be quantitatively imaged with the same film exposure as bands representing phosphorylated Akt after vehicle treatment because IGF-1 treatment results a large induction of Akt phosphorylation. Therefore, Akt phosphorylation in the presence of IGF-1 treatment could not be quantitatively compared to Akt phosphorylation in the absence of IGF-1 treatment. Individual paired t-tests were then used to make the following comparisons: ERK phosphorylation in DMSO pretreatment/vehicle treatment groups versus wortmannin pretreatment/vehicle treatment group, ERK phosphorylation in DMSO pretreatment/IGF-1 treatment group versus wortmannin pretreatment/IGF-1 treatment group, Akt phosphorylation in DMSO pretreatment/vehicle treatment group versus U0126 pretreatment/vehicle treatment group, and Akt phosphorylation in DMSO pretreatment/IGF-1 treatment group versus U0126 pretreatment/IGF-1 treatment group.

2.3. Experiment 3: Time-Course of IGF-1-dependent Estrogen Receptor Activation

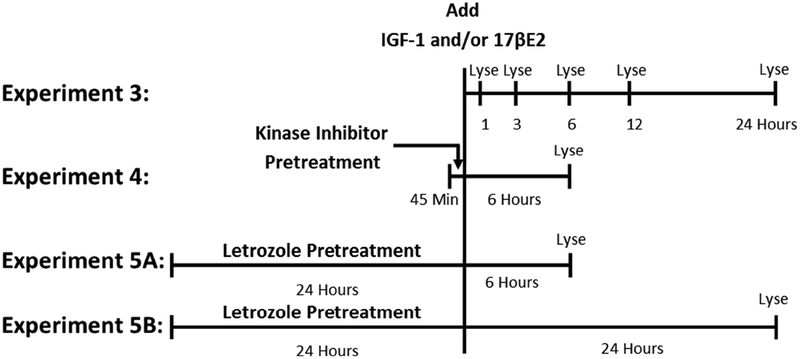

We next sought to compare the time-course of transcriptional activation at estrogen response elements that occurs following application of IGF-1 to the time-course that occurs following application of 17-β-estradiol. This experiment was not replicated for statistical analyses but only served to identify the optimal treatment time-points to be used in Experiments 4 and 5 where both the representative short-term response time-point (six hours) and long-term response time-point (24 hours) were replicated multiple times for statistical analysis. Cultures were transiently transfected with the ERE-Firefly and CMV-Renilla luciferase constructs. The ERE-Firefly luciferase reports transcriptional activity at estrogen response elements while CMV-Renilla luciferase reports transcriptional activity at the constitutively active CMV control promoter. The time-course of Experiment 3 is shown in Figure 2. Cultures were treated with IGF-1 or estradiol and incubated for durations of one, three, six, 12, or 24 hours prior to lysis. Lysate was then immediately analyzed for the presence of the experimental Firefly luciferase and control Renilla luciferase protein content. Culture maintenance was again performed as described in Section 2.1.1.

Figure 2:

Time-lines used in luciferase reporter experiments. In Experiment 3, cultures were treated with IGF-1, 17βE2, or vehicle alone for durations of one, three, six, 12, or 24 hours. Cultures were lysed and immediately analyzed for dual luciferase reporter enzyme expression. The six-hour time point was replicated in Experiments 4 and 5. In Experiment 4, cultures were pretreated for 45 minutes with the PI3K inhibitor, wortmannin, the MAPK inhibitor, U0126, the combination of wortmannin and U0126, or DMSO alone. Cells were then treated with IGF-1, 17βE2, IGF-1+17βE2, or vehicle alone for six hours. Cultures were lysed and immediately analyzed for dual luciferase reporter enzyme expression. In Experiment 5, cultures were pretreated for 24 hours with the aromatase enzyme inhibitor, letrozole, or DMSO alone. Cells were then treated with IGF-1, 17βE2, IGF-1+17βE2, or vehicle alone for six hours (Experiment 5A) or 24 hours (Experiment 5B). Cultures were lysed and immediately analyzed for dual luciferase reporter enzyme expression.

2.3.1. Transfection

The Invitrogen Neon Transfection System (Life Technologies; Carlsbad, CA) was used according to manufacturer’s instructions to transfect cells via electroporation. Each transfection contained 106 cells and 120ng of plasmid DNA comprised of 10ng CMV-GFP plasmid (Promega; Madison, WI), 10ng CMV-Renilla luciferase plasmid (Promega; Madison, WI), 100ng ERE-firefly luciferase plasmid. The ERE-Firefly luciferase (3× ERE TATA luc) plasmid was a gift from Donald McDonnell (Addgene plasmid # 11354) (Hall & McDonnell 1999). Two pulses, each 1400V and 20 milliseconds, were applied to the transfection mixture and cells were plated in a 96-well plate at a seeding density of 1.05×105 cells per cm2 in antibiotic-free growth media. Cells were allowed to recover in growth media for 40 hours after electroporation and prior to steroid hormone starvation. Cultures were then hormone starved for 24 hours prior to treatment as described in Section 2.1.2.

2.3.2. IGF-1 and Estradiol Treatment

17-β-estradiol (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in 100% ethanol. IGF-1 was dissolved in 10mM HCl. IGF-1 was added directly to culture media at a final concentration of 100nM. 17-β-estradiol was added directly to culture media at a final concentration of 10nM. Where either treatment was omitted, an equal volume of vehicle alone was added directly to media resulting in a final concentration of 0.03% ethanol and 0.02mM HCl in all cultures. Cells were treated with estradiol, IGF-1, or vehicle alone for one, three, six, 12, or 24 hours before lysis. Lysate was immediately analyzed for the presence of Firefly and Renilla luciferase enzyme proteins.

2.3.3. Dual-Luciferase Assays

Firefly and Renilla luciferase enzyme content was quantified using the Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Promega; Madison, WI). Briefly, Firefly buffer is first added to each culture well. This buffer both lyses the culture and provides the substrate for the Firefly luciferase reaction. Firefly luminescence is then immediately measured on a luminometer, which is proportional to Firefly luciferase enzyme content. The Renilla buffer is then added to each culture well. This buffer quenches the Firefly luciferase reaction and provides the substrate for the Renilla luciferase reaction. Renilla luminescence is then immediately measured on a luminometer, which is proportional to the Renilla luciferase enzyme content.

2.3.4. Statistical Analysis

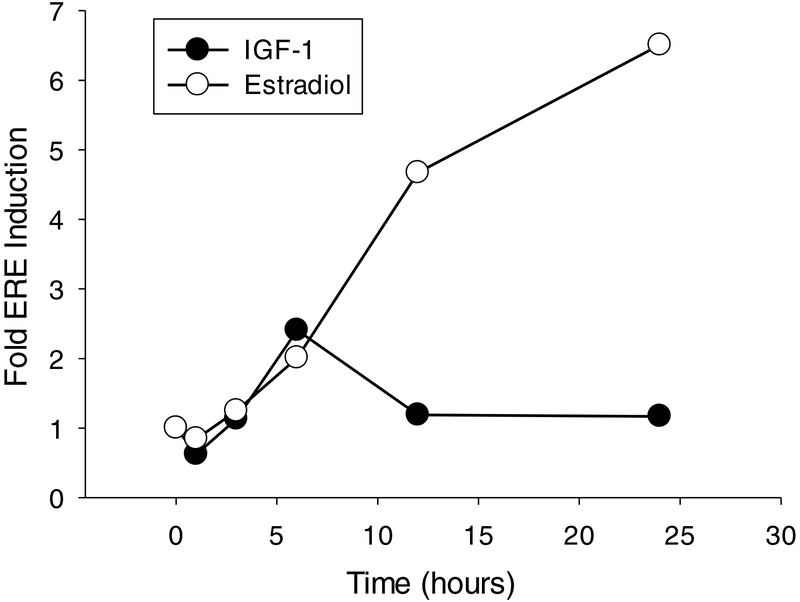

A single experiment was conducted with three replicate wells for each treatment group and time-point. The observed Firefly luciferase enzyme content was normalized to Renilla luciferase enzyme content to obtain a value for the fold induction of ERE-dependent gene transcription at each time-point. The Firefly/Renilla luciferase enzyme content value was averaged across each of the three wells in each treatment group and normalized to the time-matched vehicle control condition. All vehicle controls thus have a value of 1 and are represented by the zero-minute time-point in Figure 6.

Figure 6:

Time-course of estrogen receptor response to IGF-1 and 17-β-estradiol application. Cultures were transfected with an experimental construct expressing Firefly luciferase under control of the consensus estrogen response element (ERE) and a control construct expressing Renilla luciferase under control of the ubiquitous CMV promoter. Cultures were treated with IGF-1 or estradiol for one, three, six, 12, or 24 hours and lysed to determine the fold induction of the ERE-dependent reporter construct. The response of estrogen receptors to IGF-1 was transient, reaching its maximum six hours after stimulation and returning to baseline by 12 hours. The response to estradiol progressively increased throughout the 24-hour treatment period. Data are normalized to the average time-matched vehicle-treated control represented by the zero-minute time-point.

2.4. Experiment 4: IGF-1-dependent Regulation of Estrogen Receptor Activity through PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK

We next sought to determine if IGF-1-dependent regulation of estrogen receptor activity in Neuro-2A cells is mediated through the PI3K/Akt and/or MAPK/ERK kinase cascades. The timeline of Experiment 4 is outlined in Figure 2. Neuro-2A cells were transfected with dual ERE-Firefly and CMV-Renilla luciferase constructs via electroporation. Cultures were then pretreated for 45 minutes with the PI3K/Akt inhibitor, wortmannin, the MAPK/ERK inhibitor, U0126, the combination of wortmannin and U0126, or DMSO alone. Cultures were then treated with IGF-1 for six hours and dual luciferase assays were performed to determine the effect of inhibition of these two kinase cascades on IGF-1-dependent activation of estrogen receptors in Neuro-2A cells. General culture maintenance was performed as described in Section 2.1. Transfection was performed as described in Section 2.3.1. Cultures were hormone starved for 24 hours prior to treatment as described in Section 2.1.2. Cultures were pretreated for 45 minutes with the PI3K/Akt and/or MAPK/ERK inhibitors as described in Section 2.2.

2.4.1. IGF-1 Treatment

IGF-1 treatment was performed as described Section 2.1.4. Results of Experiment 3 (shown in Figure 6) revealed that maximal IGF-1-dependent estrogen receptor activation occurred at the six-hour time point. Therefore, cultures were treated with IGF-1 for six hours in Experiment 4 and dual luciferase assays were immediately performed as described in Section 2.3.3.

2.4.2. Statistical Analysis

This experiment was independently performed three separate times with four replicates per treatment group per experiment. The fold-induction of ERE-dependent gene transcription for each sample (Firefly/Renilla luciferase enzyme expression) was averaged across wells within each treatment group for each experiment. The averaged values were compiled across replicate experiments for statistical analysis with a final “n” of three. A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with within-subjects factors of “kinase inhibitor pretreatment” and “IGF-1 treatment” with LSD post-hoc tests was used to determine significant effects of kinase inhibition and IGF-1 application on the fold induction of ERE-dependent gene expression.

2.5. Experiment 5: Interaction of IGF-1R Signaling and Neuroestrogen Synthesis in Regulation of Estrogen Receptor Activity

Finally we sought to determine if endogenous estradiol synthesis contributes to IGF-1 or estradiol-dependent regulation of estrogen receptors in the Neuro-2A cell line. The results of Experiment 3, shown in Figure 6, determined that IGF-1 dependent ERE-Luciferase reporter expression peaks six hours after treatment while estradiol-dependent ERE-luciferase reporter expression continues to increase up to 24 hours after treatment. Therefore both the six and 24-hour time-points were replicated for statistical analysis in Experiments 5A and 5B, respectively. Cultures were transfected with dual ERE-Firefly and CMV-Renilla luciferase transcriptional reporter constructs and pretreated for 24 hours with the aromatase enzyme inhibitor, letrozole, or DMSO alone. Cultures were then treated with IGF-1, 17βE2, the combination of IGF-1 and 17βE2, or vehicle alone for another six or 24 hours. Lysate was then immediately assayed for the Firefly and Renilla luciferase enzyme content. Culture maintenance was performed as described in Section 2.1.1. Transfection was performed as described in Section 2.3.1.

2.5.1. Aromatase Enzyme Inhibitor Treatment

The aromatase enzyme inhibitor, letrozole (Sigma Aldrich; St. Louis, MO), was dissolved in DMSO and added directly to culture media to a final concentration of 100nM. An equal volume of DMSO was added to cultures receiving vehicle pretreatment resulting in a final concentration of 0.003% DMSO in all cultures during pretreatment. Cells were then incubated for 24 hours.

2.5.2. Hormone Treatment

17-β-estradiol and IGF-1 treatments were added directly to pretreatment media as described in Section 2.3.2 with an additional treatment group receiving co-application of 17-β-estradiol and IGF-1. Where a treatment was omitted, an equal volume of either vehicle was added in its place resulting in a final concentration of 0.03% ethanol and 0.02mM HCl in all cultures. Cultures were then incubated for six hours (Experiment 5A) or 24 hours (Experiment 5B) and lysed. Lysate was immediately analyzed for the presence of Firefly and Renilla luciferase enzyme content as described in Section 2.3.3.

2.5.3. Statistical Analysis

The six and 24-hour experiments were each independently replicated three separate times with four replicate cultures per treatment group per experiment. The fold-induction of ERE-dependent gene transcription (Firefly/Renilla luciferase enzyme content) for each sample was averaged within each treatment group for each experiment. Averaged values were then compiled across replicate experiments for statistical analysis resulting in a final “n” of three. A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with within-subjects factors of “aromatase enzyme inhibition” and “hormone treatment” and LSD post-hoc tests were performed separately for the six and 24-hour experiments to determine significant effects of aromatase enzyme inhibition and hormone treatment on activation of ERE-dependent gene transcription at these two time-points.

3. Results

3.1. Experiment 1: Time-course of IGF-1-dependent activation of PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK

We first sought to qualitatively determine the time-course of PI3K and MAPK activation in response to IGF-1 treatment. As shown in Figure 3A, Neuro-2A cells were treated with IGF-1 in the presence or absence of the PI3K inhibitor, wortmannin (Wort), and the MAPK inhibitor, U0126. Replicate cultures were lysed zero, five, 15, 30, 60, or 120 minutes after IGF-1 addition and western blotting for phosphorylated Akt and ERK was performed to determine relative activation of the PI3K and MAPK kinase cascades, respectively. Western blots depicting phosphorylated and total Akt and ERK from the zero, five, and 15 minute time points are shown in Figure 3B and the full, un-cropped western blots are shown in Supplemental Figure 2. Quantification of relative phosphorylation across all time points for Akt and ERK are represented in Figures 3C and 3D, respectively. As shown in Figure 3C, PI3K is rapidly activated after IGF-1 treatment, reaching its maximal level within five minutes of treatment. IGF-1-dependent PI3K activation is prolonged, remaining elevated above baseline levels throughout the two-hour treatment time-course but returning to baseline levels 24 hours after treatment (see Supplemental Figure 1). The presence of the MAPK inhibitor, U0126, enhanced the magnitude of IGF-1-dependent PI3K activation. As shown in Figure 3D, MAPK is also rapidly activated after application of IGF-1, reaching its maximal level within five minutes of treatment. Unlike IGF-1-dependent activation of PI3K, MAPK activation returns to baseline within 15 minutes of treatment. However the presence of the PI3K inhibitor, wortmannin, enhanced both the magnitude and duration of IGF-1-dependent MAPK activation. IGF-1-dependent ERK phosphorylation in the presence of wortmannin remained elevated up to one hour after treatment relative to both cultures treated with IGF-1 in the absence of wortmannin and vehicle alone. Together these results indicated that IGF-1 treatment rapidly activates both the PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK kinase cascades, which interact through mutual repression in the Neuro-2A cell line.

3.2. Experiment 2: Interaction of IGF-1-dependent PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK Signaling

As described in Section 3.1, both U0126-dpendent enhancement of IGF-1-dependent Akt phosphorylation and wortmannin-dependent enhancement of IGF-1-dependent ERK phosphorylation were apparent at the 15-minute time-point. Therefore, this time-point was chosen for further analysis in Experiment 2. As shown in Figures 4A and 5A, Neuro-2A cultures were pretreated with the PI3K inhibitor, wortmannin, the MAPK inhibitor, U0126, the combination of wortmannin and U0126, or DMSO alone and subsequently treated for 15 minutes with IGF-1 or its vehicle alone. The effect of kinase inhibition on basal phosphorylation of Akt and ERK is shown in Figure 4 while the effect of kinase inhibition on IGF-1-dependent phosphorylation of Akt and ERK is shown in Figure 5.

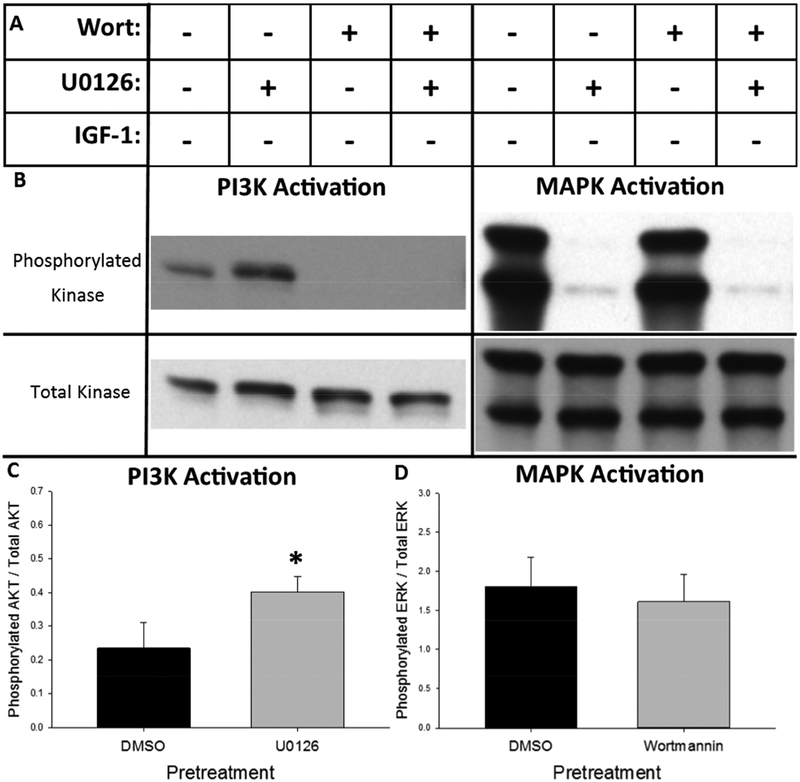

Figure 4.

Basal MAPK cascade activity suppresses basal PI3K cascade activity in the Neuro-2A cell line. (A) Cells were pretreated for 45 minutes with the PI3K inhibitor, wortmannin (Wort), the MAPK inhibitor, U0126, the combination of wortmannin and U0126 or vehicle alone (0.43% DMSO). Cells were then treated an additional 15 minutes with the vehicle for IGF-1 (0.02mM HCl) to observe the effect of pretreatment alone on basal kinase activation. (B) Representative western blots of phosphorylated and total Akt (left) and ERK (right) developed with high-sensitivity chemiluminescent substrate after the indicated treatment paradigm. (C) Inhibition of MAPK with U0126 significantly increases basal phosphorylation of Akt. (D) Inhibition of PI3K/Akt with wortmannin has no effect on mean basal phosphorylation of ERK. Bar graphs represent mean value + SEM. + addition of drug, - omission of drug. *p<0.05 vs. DMSO pretreatment.

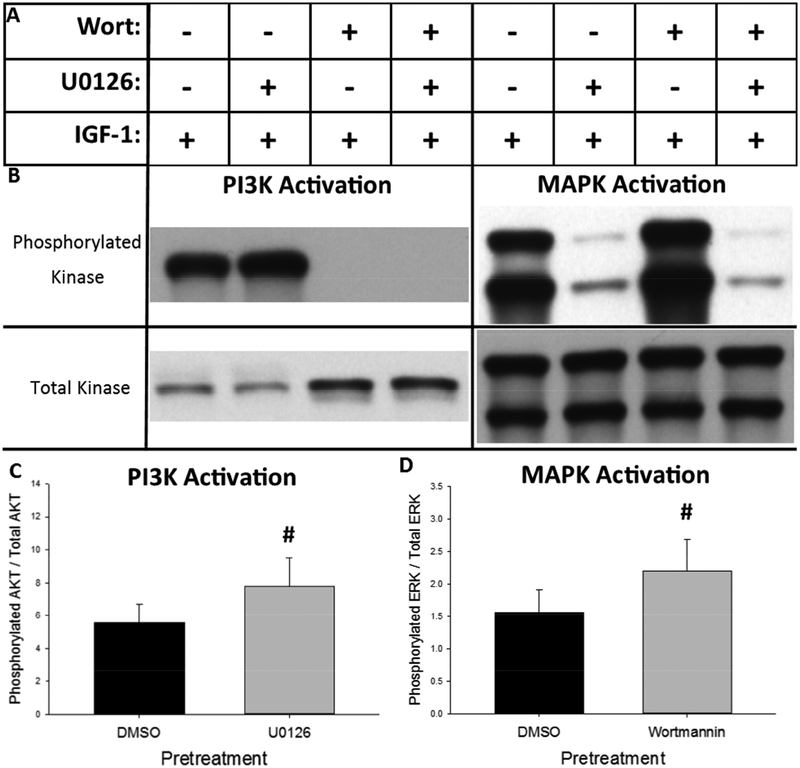

Figure 5.

IGF-1-dependent activation of the MAPK and PI3K kinase cascades are mutually repressive in the Neuro-2A cell line. (A) Cells were pretreated for 45 minutes with the PI3K inhibitor, wortmannin (Wort), the MAPK inhibitor, U0126, the combination of wortmannin and U0126 or vehicle alone (0.43% DMSO). Cells were then treated an additional 15 minutes with IGF-1 to observe the effect of pretreatment on IGF-1-dependent kinase activation. (B) Representative western blots of phosphorylated and total Akt (left) and ERK (right) developed with high-sensitivity chemiluminescent substrate after the indicated treatment paradigm. (C) Inhibition of MAPK/ERK with U0126 significantly increased IGF-1-dependent phosphorylation of Akt. (D) Inhibition of PI3K/Akt with wortmannin significantly increased IGF-1-dependent phosphorylation of ERK. Bar graphs represent mean value + SEM + addition of drug, - omission of drug. #p<0.05 vs. DMSO pretreatment.

Representative western blots demonstrating the effect of MAPK and/or PI3K inhibition on basal phosphorylation of Akt and ERK are shown in Figure 4B. Quantification of the effect of MAPK inhibition on basal phosphorylation of Akt is represented in Figure 4C while quantification of the effect of PI3K inhibition on basal phosphorylation of ERK is represented in Figure 4D. The paired t-tests determined that MAPK inhibition with U0126 significantly increased basal phosphorylation of Akt (t(5)=2.877, p=0.0347) while inhibition of PI3K with wortmannin had no effect on basal phosphorylation of ERK. These results indicate that, in absence of IGF-1 treatment, MAPK activity exerts basal inhibition of PI3K while basal PI3K activity has no effect on MAPK activity.

Representative western blots demonstrating the effect of MAPK and PI3K inhibition on IGF-1-dependent phosphorylation of Akt and ERK are shown in Figure 5B. Quantification of the effect of MAPK inhibition on IGF-1-dependent phosphorylation of Akt is represented in Figure 5C while quantification of the effect of PI3K inhibition on IGF-1-dependent phosphorylation of ERK is represented in Figure 5D. The paired t-tests determined that U0126 pretreatment significantly enhanced IGF-1-dependent Akt phosphorylation (t(5)=5.689, p=0.0023) and wortmannin pretreatment significantly enhanced IGF-1-dependent ERK phosphorylation (t(5)=3.307, p=0.0213). These data confirm that the MAPK and PI3K cascades mutually repress activation of each other in Neuro-2A cells after treatment with IGF-1.

3.3. Experiment 3: Time-Course of IGF-1-dependent Estrogen Receptor Activation

We next sought to qualitatively determine the time-course of IGF-1-dependent activation of nuclear estrogen receptors in Neuro-2A cells in comparison to the time-course of activation of nuclear estrogen receptors by their cognate ligand, 17-β-estradiol. Neuro-2A cells were transfected with experimental ERE-Firefly and control CMV-Renilla luciferase reporter constructs and treated with IGF-1 or 17-β-estradiol for zero, one, three, six, 12, or 24 hours. Fold induction of the experimental ERE-Firefly luciferase reporter construct was used to measure the relative activation of nuclear estrogen receptors. As shown in Figure 6, nuclear estrogen receptors displayed distinct temporal responses to treatment with IGF-1 and 17-β-estradiol. IGF-1 treatment resulted in a transient increase in ERE-dependent gene expression, reaching its maximal response at six hours and returning to baseline within 12 hours of treatment. 17-β-estradiol treatment resulted in a sustained increase in ERE-dependent gene expression, progressively increasing across the duration of the 24-hour time-course. These results indicate that exogenous 17-β-estradiol treatment results in continuous, while IGF-1 treatment results in transient, activation of endogenous nuclear estrogen receptors in the Neuro-2A cell line.

3.4. Experiment 4: IGF-1-dependent Regulation of Estrogen Receptor Activity through PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK

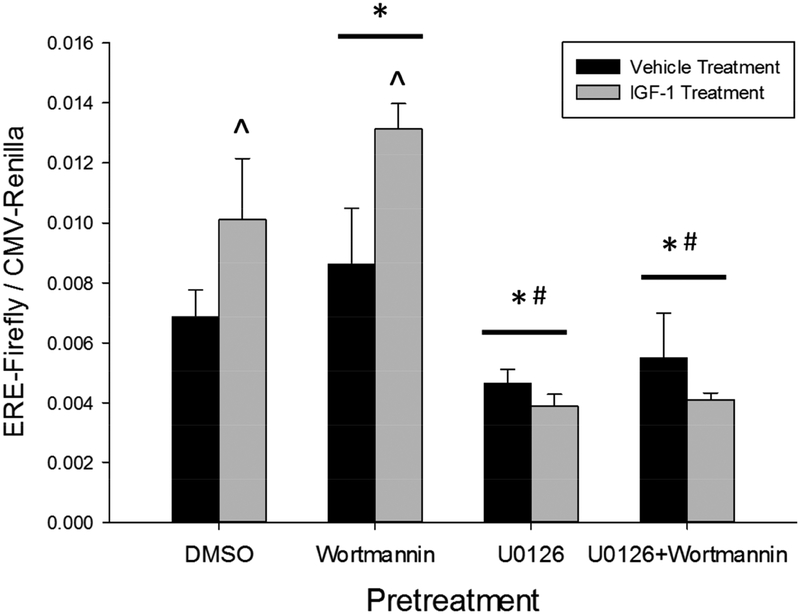

We next sought to determine how activation of MAPK and PI3K contribute to activation of estrogen receptor signaling in Neuro-2A cells. As described in Section 3.3, the maximal induction of ERE-dependent gene expression following IGF-1 application was observed at the six-hour time-point. Therefore, this time-point was chosen for further analysis in Experiment 4. Cells were again transfected with the dual ERE-Firefly and CMV-Renilla luciferase reporter constructs. They were then pretreated for 45 minutes with the PI3K inhibitor, wortmannin, the MAPK inhibitor, U0126, the combination of wortmannin and U0126, or DMSO alone. Cells were then treated for six hours with IGF-1 or vehicle alone and lysed to measure induction of ERE-dependent gene expression. The two-way repeated-measures ANOVA identified a significant main effect of kinase inhibitor pretreatment (F(3,6)=26.458, p<0.001), no main effect of IGF-1 treatment, and a significant interaction between kinase inhibitor pretreatment and IGF-1 treatment (F(3,6)=9.720 p=0.01). Post-hoc testing among levels of pretreatment determined that pretreatment with wortmannin increased (p<0.001) while pretreatment with U0126 (p=0.003) or U0126+wortmannin (p=0.005) decreased ERE-dependent gene expression relative to pretreatment with DMSO alone. Further post-hoc testing to determine the source of pretreatment by treatment interaction revealed that IGF-1 treatment significantly increased ERE-dependent gene expression in cultures pretreated with DMSO (p=0.045) or wortmannin (p=0.014) but not U0126 or the combination U0126 and wortmannin. Finally, IGF-1 treatment after wortmannin pretreatment resulted in a significantly larger induction of ERE-dependent gene transcription than IGF-1 treatment after pretreatment with vehicle alone (p=0.018). Together these results indicate that IGF-1-dependent MAPK activation promotes, while IGF-1-dependent PI3K activation inhibits, ERE-dependent gene expression in Neuro-2A cells.

3.5. Experiment 5: Interaction of IGF-1R Signaling and Neuroestrogen Synthesis in Regulation of Estrogen Receptor Activity

Finally, we sought to determine the contribution of exogenously applied and endogenously synthesized estradiol on IGF-1-dependent activation of estrogen receptors in Neuro-2A cells. As shown in Figure 6, IGF-1-dependent estrogen receptor activation peaked within six hours of treatment while estradiol-dependent estrogen receptor activation continued to increase across the 24-hour time-course. Both the six and 24-hour time-points were chosen for further replication and quantitative statistical analysis to determine the effect of aromatase enzyme inhibition and exogenous estradiol application both during IGF-1 dependent estrogen receptor activation and long after IGF-1-dependent estrogen receptor activation has ceased. Cultures were again transfected with dual ERE-Firefly and CMV-Renilla luciferase reporter constructs and then were pretreated for 24 hours with the aromatase enzyme inhibitor, letrozole, or DMSO alone. Cells were then treated for six or 24 hours with IGF-1, 17βE2, IGF-1+17βE2, or vehicle alone and lysed to determine induction of ERE-dependent gene expression.

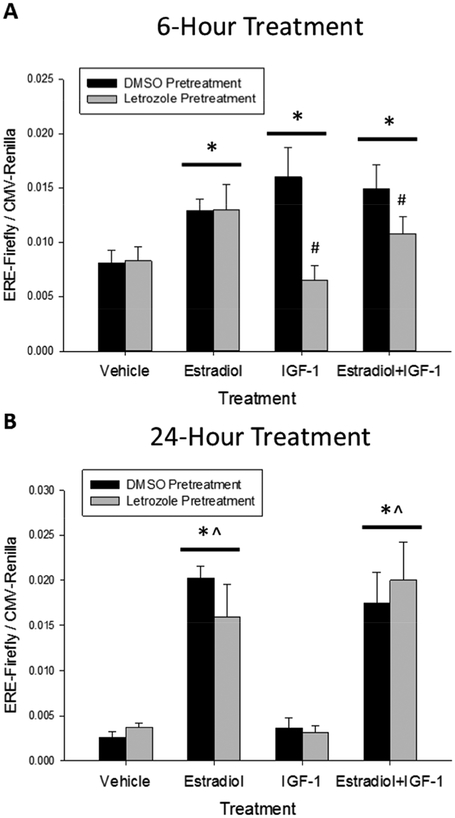

After six hours of treatment, the two-way repeated-measures ANOVA found no significant main effect of aromatase enzyme inhibition, a significant main effect of hormone treatment (F(3,6)=9.877, p=0.003) and a significant interaction between aromatase enzyme inhibition and hormone treatment (F(3,6)=8.370, p=0.006). As shown in Figure 8A, post-hoc testing among the levels of treatment identified that treatment with estradiol (p<0.001), IGF-1 (p=0.013), and the combination of estradiol and IGF-1 (p<0.001) significantly increased ERE-dependent gene expression relative to treatment with vehicle alone. Further post-hoc testing to determine the source of aromatase enzyme inhibition by hormone treatment interaction determined that letrozole pretreatment resulted in a significant reduction in the estrogen receptor response to IGF-1 (p<0.001) as well as the combination of 17-β-estradiol and IGF-1 (p=0.049). Together these results indicate that that in vitro neuroestrogen synthesis mediates IGF-1-dependent activation of estrogen receptors but does not affect short-term estrogen receptor activation in response to application of exogenous estradiol.

Figure 8.

Short-term IGF-1-dependent activation of estrogen receptors in Neuro-2A cells requires aromatase enzyme activity. Cultures were transfected with an experimental construct expressing Firefly luciferase under control of the consensus estrogen response element (ERE) and a control construct expressing Renilla luciferase under control of the ubiquitous CMV promoter. Cells were pretreated for 24 hours with the aromatase enzyme inhibitor, letrozole, or vehicle alone (0.003% DMSO). IGF-1, 17βE2, the combination of IGF-1 and 17βE2, or vehicle alone (0.02mM HCl, 0.03% ethanol) was then added to cultures. Cells were incubated for six hours (A) or 24 hours (B) and lysed to determine expression of the reporter constructs with a dual luciferase assay. IGF-1 treatment enhanced ERE-dependent gene expression when measured six but not 24 hours after treatment. Pretreatment with letrozole blocked IGF-1-dependent estrogen receptor activation six hours post-treatment. Aromatase enzyme inhibition has no effect on IGF-1 or estradiol dependent estrogen receptor activation 24 hours post-treatment. Data presented as mean value + SEM. *p<0.05 vs Vehicle treatment. ^p<0.05 vs IGF-1 treatment. #p<0.05 vs DMSO pretreatment.

After 24 hours of treatment, the two-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed no effect of aromatase enzyme inhibition (F(1,6)=0.0147, p=0.914), a significant effect of hormone treatment (F(3,6)=36.861, p<0.001), and no interaction (F(3,6)=0.522, p=0.682). As shown in Figure 8B, post-hoc testing among the levels of treatment revealed that treatment with estradiol (p<0.001) or the combination of estradiol and IGF-1 (p<0.001) significantly increased ERE-dependent transgene expression relative to treatment vehicle alone. Treatment with IGF-1 alone had no effect on ERE-dependent gene expression and treatment with estradiol (p<0.001) or the combination of estradiol and IGF-1 (p<0.001) also significantly increased ERE-dependent transgene expression relative to treatment IGF-1. Letrozole pretreatment had no effect on ERE-dependent gene expression at the 24-hour time point. These results confirm that estradiol-dependent estrogen receptor activation in Neuro-2A cells persists 24 hours after treatment but IGF-1-dependent estrogen receptor activation does not. Additionally, aromatase enzyme inhibition did not affect the response of nuclear estrogen receptors to the co-application of both estradiol and IGF-1 at the 24-hour time-point. This indicates that aromatase enzyme inhibition only interferes with the response to co-application of both estradiol and IGF-1 during the time when IGF-1 treatment is effective.

4. Discussion

The results presented here outline the mechanisms through which IGF-1-dependent activation of mutually repressive MAPK and PI3K kinase cascades interact with endogenous estrogen synthesis to mediate ERE-dependent gene expression in the Neuro-2A neuroblastoma cell line. The effects of kinase inhibition and IGF-1 treatment on rapid PI3K and MAPK signaling mirror the subsequent patterns of nuclear estrogen receptor activation. IGF-1-dependent activation of nuclear estrogen receptors is mediated through MAPK and inhibited by PI3K and requires endogenous estrogen synthesis.

Basal phosphorylation of both ERK and Akt was detectable by western blot in the absence of any treatment, indicating that both MAPK and PI3K have some level of basal activity in Neuro-2A cells. Inhibition of basal MAPK activity with U0126 resulted in a significant increase in PI3K activity while inhibition of basal Akt activity with wortmannin had no effect on MAPK activity. This result suggests MAPK non-selectively suppresses PI3K while the observed PI3K-dependent suppression of MAPK is specific to IGF-1 treatment. Although only the main effects of MAPK and PI3K inhibition on ERE-dependent gene expression were statistically significant, a post-hoc test performed to directly compare ERE-dependent transgene expression between the DMSO pretreatment, vehicle treatment group and the U0126 pretreatment, vehicle treatment groups was also trending toward significance (p=0.067). Furthermore, as wortmannin pretreatment alone resulted in a non-statistically significant increase in estrogen receptor activation, ERE-dependent gene expression was significantly higher in the wortmannin pretreatment, vehicle treatment group than the U0126 pretreatment, vehicle treatment group (p<0.001). These results suggest that basal MAPK and PI3K activities might each perform a role in regulation of basal estrogen receptor activity in Neuro-2A cells, but this hypothesis would need to be confirmed with additional experimentation. A thorough identification of the sources of basal MAPK and PI3K activity in neuronal cells and how they affect estrogen receptor activity in the absence of applied estrogens is an interesting avenue for further investigation.

IGF-1 treatment elicited a rapid and short burst of MAPK activation in Neuro-2A cells that is terminated within 15 minutes of stimulation. The MAPK inhibitor, U0126, completely blocked IGF-1-dependent induction of ERE-dependent gene expression, indicating that it is the critical kinase that mediates IGF-1-dependent activation of estrogen receptors. We additionally identified a novel function of PI3K in rapid regulation of estrogen receptor activation that is distinct from the previously described long-term regulation of estrogen receptor stability (Mendez & Garcia-Segura 2006). In the present work, application of IGF-1 in the presence of the PI3K inhibitor, wortmannin, enhanced both the magnitude and duration of the transient MAPK burst and also enhanced IGF-1-dependent induction of ERE-dependent gene expression. Furthermore, wortmannin-dependent enhancement of nuclear estrogen receptor activity was not observed in the presence of the MAPK inhibitor U0126. This indicates that PI3K-dependent regulation of nuclear estrogen receptors is achieved through regulation of MAPK activity and not through some unidentified, independent pathway. However, support for this interpretation is limited by the use of a single pharmacological agent for each kinase pathway. We cannot rule out the possibility that these inhibitors had unexpected off target effects similar to previous work with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (Pasapera Limón et al. 2003). The present results are also limited by the lack of replication of IGF-1-dependent rapid activation of MAPK five minutes after treatment. However, this effect has already been described previously in a number of cell types including the Neuro-2A cell line used in the present work (Munderloh et al. 2009). The use of additional pharmacological inhibitors or genetic techniques for manipulation of MAPK and PI3K activity would confirm and refine the mechanisms of IGF-1-dependent interaction between these two kinases.

The previously described endogenous patterns of IGF-1-induced kinase signaling, and resulting interaction between MAPK and PI3K, differ across neuronal sub-types. In R28 retinal neuron-like cells, IGF-1 treatment elicits prolonged activation (at least 80 minutes) of both PI3K and MAPK (Kong et al. 2016). IGF-1 activates PI3K but not MAPK in PC12 neural crest cells but activates both PI3K and MAPK in primary culture of cortical neurons (Wang et al. 2012). IGF-1 activates PI3K and inhibits MAPK in substantia nigra pars compacta dopaminergic neurons in rat model of Parkinson’s disease (Quesada et al. 2008). IGF-1R-dependent activation of PI3K activates ERK via c-raf but independent of Akt in trigeminal ganglion neurons (Wang et al. 2014). Chochlear hair cell survival is enhanced by IGF-1 through a mechanism that requires both PI3K and MAPK and results in transient (12 hour) burst in survival-related gene expression (Hayashi et al. 2013; Hayashi et al. 2014). The pattern of activation in Neuro-2A cells described here is most similar to that of primary cultured hippocampal neurons. IGF-1 treatment results in sustained activation of PI3K but transient activation of MAPK while BDNF treatment results in sustained activation of both cascades in primary cultured hippocampal neurons (Zheng & Quirion 2004).

Additionally, we show here that treatment with IGF-1 and 17-β-estradiol elicit distinct temporal transcriptional responses from estrogen receptors in the Neuro-2A cell line. Treatment with estradiol resulted in a progressively increasing rate of ERE-dependent gene expression over a 24-hour time-course. In contrast, IGF-1 treatment elicited only a transient response, peaking at six hours and terminating 12 hours after treatment. It is not clear from the data presented here why the response to IGF-1 was transient. IGF-1 dependent activation of MAPK ceased within 15 minutes of treatment while IGF-1-dependent activation of PI3K lasted for at least two hours but had terminated 24 hours after treatment (see Supplemental Figure 1). The response may be actively terminated or the cells may gradually stop responding as the IGF-1 treatment is naturally degraded. In either case, the termination of response to IGF-1 mirrors the termination of the transient MAPK burst, which is accelerated by IGF-1-induced activation of PI3K. This potentially creates circumstances in which MAPK, the critical kinase that promotes estrogen receptor activation, is actively inhibited while PI3K, a kinase that opposes MAPK-dependent activation of estrogen receptors, remains highly active for at least two hours. We hypothesize that this ultimately results in a prolonged refractory period during which estrogen receptors will be unable to respond to subsequent MAPK stimulatory events. Further studies would be necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

The interaction of IGF-1 and estrogen signaling has been described in various models of neuroprotection (Quesada et al. 2008; Kong et al. 2016; Hayashi et al. 2013; Hayashi et al. 2014), but the direct involvement of ERE-dependent gene expression in these various models was not directly tested. MAPK has previously been shown to activate ERE-dependent gene expression by exogenously expressed ERα in the non-neuronal COS-1 cell line (Kato et al. 1995) and the SK-N-BE neuroblastoma cells (Patrone et al. 1998). Previous wok investigating activation of endogenous estrogen receptors in the Neuro-2A cell line found that IGF-1 and estradiol treatment both enhanced ERE-dependent expression of the SEAP reporter protein 24 hours after treatment (Mendez & Garcia-Segura 2006). However, co-application of IGF-1 and estradiol reduced the estrogen receptor response relative to treatment with estradiol alone. Application of wortmannin not only blocked the IGF-1-dependent reduction in estrogen receptor activity but enhanced activity to levels far above that of treatment with estradiol alone. The results presented here describe a dynamic time-course of IGF-1-dependent regulation of estrogen receptor activity. IGF-1 treatment rapidly activates both MAPK and PI3K, but MAPK activity is rapidly terminated while PI3K activity remains elevated for at least two hours but not as long as 24 hours after treatment (see Supplemental Figure 1). The SEAP reporter protein has a half-life of about 22 hours in culture (Salucci et al. 2002), therefore this reporter system gives an indication about how active estrogen receptors have been over the entire previous day. In contrast, the Firefly luciferase reporter protein has a half-life of only about two hours (Ignowski & Schaffer 2004), meaning this reporter system gives an indication about how active estrogen receptors have been over the previous few hours. The high temporal resolution of this reporter system allowed us to separate the short-term MAPK-dependent estrogen receptor activation from the longer term PI3K-dependent inhibition of ERE-dependent gene expression described previously.

Finally, we have determined for the first time that aromatase enzyme activity is necessary to observe IGF-1-dependent estrogen receptor activation. Neuroestrogen synthesis has been shown to be important for the maintenance of synaptic spine density in hippocampal slice cultures (Kretz et al. 2004) and has been shown to support cognitive function in postmenopausal women (Bender et al. 2015; Collins et al. 2009; Bayer et al. 2015) and ovariectomized rodents (Vierk et al. 2012; Martin et al. 2003). The present work shows a specific requirement for aromatase enzyme activity in the short-term IGF-1-dependent activation of ERE-dependent gene expression. Similar work has shown that aromatase enzyme activity was necessary for rapid activation of Arc and PSD-95 mRNA synthesis in the hippocampal H19–7 immortalized cell line (Chamniansawat & Chongthammakun 2012). In vivo work in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease pathology found that levels of brain-derived estradiol alter the efficacy of estrogen replacement therapy in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease pathology (Li et al. 2013). Like the present work, these observations indicate that exogenously applied estradiol and endogenously synthesized neuroestrogens are not always interchangeable and result in distinct patterns of cell signaling and estrogen dependent gene regulation.

Previous results suggest that relief of ligand-binding domain inhibition is necessary to unmask MAPK-dependent activation of ERα (Ali et al. 1993; Kato et al. 1995). We suggest that in Neuro-2A cells, endogenous estrogen synthesis provides a constant source of minimal ligand sufficient to relieve ligand-binding domain inhibition and permit responsiveness to the IGF-1 stimulatory signal. However, the present work does not rule out alternative interpretations of the data presented. Aromatase activity can also be rapidly activated through intracellular kinase signaling (Fester et al. 2015). It is possible that IGF-1 dependent activation of MAPK directly upregulates aromatase enzyme activity, activating nuclear estrogen receptor activity indirectly through an autocrine mechanism. Additionally, estrogen signaling has also been shown to activate a variety of kinase pathways in neuronal (Boulware et al. 2005) and neuroblastoma cells (Clark et al. 2014; Ni et al. 2015; Takahashi et al. 2011). It is therefore also possible that local aromatase enzyme-dependent estrogen synthesis initiates estrogen-dependent kinase signaling that interacts with IGF-1-dependent kinase signaling and modulates IGF-1-dependent effects on nuclear estrogen receptor activation. Further experimentation will be necessary to refine these observations and elucidate the full mechanism of interaction.

Unexpectedly, co-application of exogenous estradiol along with IGF-1 after aromatase enzyme inhibition did not result in the same short-term level of estrogen receptor activation as application of exogenous estradiol alone after aromatase enzyme inhibition. Small differences in the sequence of stimulatory events experienced by each treatment group can account for this difference. IGF-1 dependent MAPK activation reaches its maximal level within five minutes and returns to near baseline levels after 15 minutes of treatment. It has been shown that estradiol-induced dimerization of ERα is negligible within the first 15 minutes of estradiol application and does not reach maximum levels until two hours after treatment (Powell & Xu 2008). Cultures pretreated with the aromatase enzyme inhibitor followed by treatment with the combination of estradiol and IGF-1 therefore first experienced rapid activation of MAPK and PI3K followed by slower ligand-induced dimerization, while cultures pretreated with aromatase enzyme inhibitor followed by treatment with exogenous estradiol alone experienced only slower ligand-induced dimerization with no intervening kinase activation. The high temporal resolution of the Firefly luciferase reporter systems may be able to detect these differences where other reporter systems with lower temporal resolution would not. Furthermore, aromatase enzyme inhibition had no effect on the response of nuclear estrogen receptors to co-application of estradiol and IGF-1 24 hours after treatment; long after IGF-1-dependent regulation of nuclear estrogen receptors had ceased. Aromatase enzyme inhibition only interfered with the response to co-application of estradiol and IGF-1 within the first six hours when IGF-1 treatment was still effective.

5. Conclusion

The results presented here describe a highly interactive mechanism through which IGF-1 signaling activates nuclear estrogen receptors in the Neuro-2A cell line. IGF-1 treatment simultaneously results in a rapid, but transient, burst in MAPK activity as well as a rapid and prolonged activation of PI3K. MAPK activation is the critical kinase event that mediates IGF-1-dependent estrogen receptor activation. The prolonged activation of PI3K functions to dampen both the transient burst in MAPK activity and subsequent activation of nuclear estrogen receptors. Finally, we have determined that IGF-1-dependent MAPK activation requires concomitant endogenous estrogen synthesis through the aromatase enzyme to mediate estrogen receptor activation. Together these results highlight the interactive nature of cellular signaling context and ligand availability in activation of nuclear estrogen receptors through intracellular kinase signaling.

Supplementary Material

Figure 7.

The MAPK cascade mediates, and the PI3K cascade inhibits, IGF-1-dependent activation of estrogen receptors in the Neuro-2A cell line. Cultures were transfected with an experimental construct expressing Firefly luciferase under control of the consensus estrogen response element (ERE) and a control construct expressing Renilla luciferase under control of the ubiquitous CMV promoter. Cultures were then pretreated for 45 minutes with the PI3K inhibitor, wortmannin, the MAPK inhibitor, U0126, the combination of wortmannin and U0126, or vehicle alone (0.43% DMSO). Cells were then treated with IGF-1 or vehicle alone (0.02mM HCl) for six hours and lysed to determine the fold induction of the ERE-dependent reporter construct. MAPK inhibition decreased basal ERE-dependent gene expression and blocked IGF-1-dependent activation of estrogen receptors. PI3K inhibition potentiated IGF-1-dependent activation of estrogen receptors. Data presented as mean value + SEM. *p<0.05 vs DMSO pretreatment. #p<0.05 vs Wortmannin pretreatment. ^p<0.05 vs Vehicle treatment.

Highlights.

IGF-1 treatment rapidly initiates both MAPK and PI3K cascades in Neuro-2A cells.

MAPK and PI3K interact through mutual repression after IGF-1 treatment.

MAPK mediates IGF-1-dependent activation of nuclear estrogen receptors.

PI3K opposes IGF-1-dependent activation of nuclear estrogen receptors.

IGF-1R-dependent activation of nuclear estrogen receptors requires endogenous aromatase enzyme activity.

Funding

Funding for this work was provided by the National Institute on Aging Grant R01AG041374 (JMD) and the Louisiana board of Regents Fellowship LEQSF(2012–2017)-GF-15 (KJP).

Abbreviations

- ERα

estrogen receptor alpha

- AF-2

activation function-2

- AF-1

activation function-1

- IGF-1

insulin-like growth factor-1

- IGF-1R

IGF-1 receptor

- PI3K

phosphoinositide-3 kinase

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- 17βE2

17-β-estradiol

- ERE

estrogen response element

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ali S et al. , 1993. Modulation of transcriptional activation by ligand-dependent phosphorylation of the human oestrogen receptor A/B region. The EMBO journal, 12(3), pp.1153–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer J et al. , 2015. The effect of estrogen synthesis inhibition on hippocampal memory. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 56, pp.213–225. Available at: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender CM et al. , 2015. Patterns of change in cognitive function with anastrozole therapy. Cancer, 121(15), pp.2627–2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulware MI et al. , 2005. Estradiol Activates Group I and II Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor Signaling, Leading to Opposing Influences on cAMP Response Element-Binding Protein. Journal of Neuroscience, 25(20), pp.5066–5078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulware MI, Heisler JD & Frick KM, 2013. The Memory-Enhancing Effects of Hippocampal Estrogen Receptor Activation Involve Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor Signaling. The Journal of Neuroscience, 33(38), pp.15184–15194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunone G et al. , 1996. Activation of the unliganded estrogen receptor by EGF involves the MAP kinase patwhay and direct phosphorylation. The EMBO journal, 15(9), pp.2174–2183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona-Gómez GP, Doncarlos L & Garcia-Segura LM, 2000. Insulin-like growth factor I receptors and estrogen receptors colocalize in female rat brain. Neuroscience, 99(4), pp.751–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamniansawat S & Chongthammakun S, 2012. A priming role of local estrogen on exogenous estrogen-mediated synaptic plasticity and neuroprotection. Experimental and Molecular Medicine, 44(6), pp.403–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S et al. , 2014. Estrogen receptor-mediated transcription involves the activation of multiple kinase pathways in neuroblastoma cells. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 139, pp.45–53. Available at: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins B et al. , 2009. Cognitive effects of hormonal therapy in early stage breast cancer patients: A prospective study. Psycho-Oncology, 18(8), pp.811–821. Available at: http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/fulltext/121552800/PDFSTART%5Cnhttp://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emed9&AN=2009521100%5Cnhttp://sfx.scholarsportal.info/mcmaster?sid=OVID:embase&id=pmid:&id=doi:10.1002/pon.1453&issn. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fester L et al. , 2015. Control of aromatase in hippocampal neurons. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 160, pp.9–14. Available at: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Goff P et al. , 1994. Phosphorylation of the Human Estrogen Receptor. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 269(6), pp.4458–4466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissom EM & Daniel JM, 2016. Evidence for Ligand-Indepenent Activation of Hippocampal Estrogen receptor-α by IGF-1 in Hippocampus of Ovariectomized Rats. Endocrinology, 157(8), pp.3149–3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JM & McDonnell DP, 1999. The estrogen receptor b-isoform (ERb) of the human estrogen receptor modulates ERa transcriptional activity and is a key regulator of the cellular response to estrogens and antiestrogens. Endocrinology, 140(12), p.5566–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y et al. , 2014. Insulin-like growth factor 1 induces the transcription of Gap43 and Ntn1 during hair cell protection in the neonatal murine cochlea. Neuroscience Letters, 560, pp.7–11. Available at: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.11.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y et al. , 2013. Insulin-like growth factor 1 inhibits hair cell apoptosis and promotes the cell cycle of supporting cells by activating different downstream cascades after pharmacological hair cell injury in neonatal mice. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience, 56, pp.29–38. Available at: 10.1016/j.mcn.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignowski JM & Schaffer DV, 2004. Kinetic Analysis and Modeling of Firefly Luciferase as a Quantitative Reporter Gene in Live Mammalian Cells. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 86(7), pp.827–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa T, Glidewell-Kenney C & Jameson JL, 2006. Aromatase-independent testosterone conversion into estrogenic steroids is inhibited by a 5α-reductase inhibitor. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 98(2–3), pp.133–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadowaki T et al. , 1996. Signal transduction mechanism of insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1. Endocrine Journal, 43 Suppl, pp.S33–S41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato S et al. , 1995. Activation of the estrogen receptor through phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinase. Science, 270(5241), pp.1491–1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong D et al. , 2016. Insulin-like growth factor 1 rescues R28 retinal neurons from apoptotic death through ERK-mediated Bim EL phosphorylation independent of Akt. Experimental Eye Research, 151, pp.82–95. Available at: 10.1016/j.exer.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretz O et al. , 2004. Hippocampal Synapses Depend on Hippocampal Estrogen Synthesis. Journal of Neuroscience, 24(26), pp.5913–5921. Available at: http://www.jneurosci.org/cgi/doi/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5186-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V et al. , 1987. Functional domains of the human estrogen receptor. Cell, 51(6), pp.941–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R et al. , 2013. Brain Endogenous Estrogen Levels Determine Responses to Estrogen Replacement Therapy via Regulation of BACE1 and NEP in Female Alzheimer ‘s Transgenic Mice. Molecular Neurobiology, 47, pp.857–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S et al. , 2003. Impaired spatial reference memory in aromatase-deficient (ArKO) mice. Neuroreport, 14(15), pp.1979–1982.s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS et al. , 1982. Steroid hormones: humoral signals which alter brain cell properties and functions. Recent Progress in Hormone Research, 38, pp.41–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez P & Garcia-Segura LM, 2006. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and glycogen synthase kinase 3 regulate estrogen receptor-mediated transcription in neuronal cells. Endocrinology, 147(6), pp.3027–3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munderloh C et al. , 2009. Reggies / Flotillins Regulate Retinal Axon Regeneration in the Zebrafish Optic Nerve and Differentiation of Hippocampal and N2a Neurons. The Journal of Neuroscience, 29(20), pp.6607–6615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson BS, Black KL & Daniel JM, 2016. Circulating Estradiol Regulates Brain-Derived Estradiol via Actions at GnRH Receptors to Impact Memory in Ovariectomized Rats. eNeuro, 3(6), pp.1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Y et al. , 2015. Akt and cAMP response element binding protein mediate 17 -estradiol regulation of glucose transporter 3 expression in human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell line. Neuroscience Letters, 604, pp.58–63. Available at: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasapera Limón AM et al. , 2003. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor LY294002 binds the estrogen receptor and inhibits 17 b-estradiol-induced transcriptional acti v ity of an estrogen sensiti v e reporter gene. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 200, pp.199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrone C et al. , 1998. Divergent pathways regulate ligand-independent activation of ERα in SK-N-BE neuroblastoma and COS-1 renal carcinoma cells. Molecular Endocrinology, 12(6), pp.835–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard KJ, Wartman HD & Daniel JM, 2018. Previous estradiol treatment in ovariectomized mice provides lasting enhancement of memory and brain estrogen receptor activity. Hormones and Behavior, 102(December 2017), pp.76–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell E & Xu W, 2008. Intermolecular interactions identify ligand-selective activity of estrogen receptor α/β dimers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105(48), pp.19012–19017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prange-Kiel J et al. , 2003. Para/Autocrine Regulation of Estrogen Receptors in Hippocampal Neurons. Hippocampus, 13(2), pp.226–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesada A, Lee BY & Micevych PE, 2008. PI3 Kinase / Akt Activation Mediates Estrogen and IGF-1 Nigral DA Neuronal Neuroprotection Against a Unilateral Rat Model of Parkinson ‘s Disease. Developmental Neurobiology, (February), pp.632–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers SP, Bohacek J & Daniel JM, 2010. Transient Estradiol Exposure during Middle Age in Ovariectomized Rats Exerts Lasting Effects on Cognitive Function and the Hippocampus. Endocrinology, 151(3), pp.1194–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salucci V et al. , 2002. Tight control of gene expression by a helper-dependent adenovirus vector carrying the rtTA2-M2 tetracycline transactivator and repressor system. Gene Therapy, 9(21), pp.1415–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K et al. , 2011. Estrogen induces neurite outgrowth via Rho family GTPases in neuroblastoma cells. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience, 48(3), pp.217–224. Available at: 10.1016/j.mcn.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EA & Siiteri PK, 1974. Utilization of Oxygen and Reduced Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate by Human Placental Microsomes during Aromatization of Utilization of Oxygen and Reduced Nicotinamide Adenine Dinwcleotide Phosphate by Human Placental Microsomes during Aromatiz. J Biol Chem, 249(17), pp.5364–5372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tora L et al. , 1989. The Human Estrogen Receptor Has Two Independent Nonacidic Transcriptional Activation Functions. Cell, 59(3), pp.477–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vierk R et al. , 2012. Aromatase inhibition abolishes LTP generation in female but not in male mice. The Journal of Neuroscience, 32(24), pp.8116–26. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22699893 [Accessed November 4, 2013]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H et al. , 2012. Insulin-like growth factor-1 induces the phosphorylation of PRAS40 via the PI3K / Akt signaling pathway in PC12 cells. Neuroscience Letters, 516, pp.105–109. Available at: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H et al. , 2014. Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 Receptor-Mediated Inhibition of A-type K+ Current Induces Sensory Neuronal Hyperexcitability Through the Phospohatidylinositol 3-Kinase and Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase 1/2 Pathways, Independently of Akt. Neuroendocrinology, 155(1), pp.168–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster NJG et al. , 1988. The hormone-binding domains of the estrogen and glucocorticoid receptors contain an inducible transcription activation function. Cell, 54(2), pp.199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrenberg U, Prange-Kiel J & Rune GM, 2001. Steroidogenic factor-1 expression in marmoset and rat hippocampus: Co-localization with StAR and aromatase. Journal of Neurochemistry, 76(6), pp.1879–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witty CF et al. , 2012. Increasing Hippocampal Estrogen Receptor Alpha Levels via Viral Vectors Increases MAP Kinase Activation and Enhances Memory in Aging Rats in the Absence of Ovarian Estrogens. PLoS ONE, 7(12), pp.1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witty CF et al. , 2013. Short-term estradiol administration in aging ovariectomized rats provides lasting benefits for memory and the hippocampus: A role for insulin-like growth factor-I. Endocrinology, 154(2), pp.842–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng W & Quirion R, 2004. Comparative signaling pathways of insulin-like growth factor-1 and brain-derived neurotrophic factor in hippocampal neurons and the role of the PI3 kinase pathway in cell survival. Journal of Neurochemistry, 89, pp.844–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L et al. , 2014. Oestradiol-Induced Synapse Formation in the Female Hippocampus : Roles of Oestrogen Receptor Subtypes Neuroendocrinology. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 26(19), pp.439–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuber MX, Simpson ER & Waterman MR, 1986. Expression of Bovine 17alpha-Hydroxylase Cytochrome P-450 cDNA in Nonsteroidogenic (COS 1) cells. Science, 234(4781), pp.1258–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.