Abstract

Owing to the antihemostatic property of viper venom, hemorrhagic complications including intracerebral hemorrhage are the most commonly encountered after viper bite. Ischemic strokes have been rarely reported after viper envenomation, and its occurrence has been attributed to multiple mechanisms. Postsnakebite seizures are known to occur after neurotoxic bite. Here, we report the case of a viper bite victim who developed status epilepticus within 3 h after viper bite. He had only mild signs of local envenomation, and prolonged whole blood clotting time was the only manifestation of systemic envenomation. Subsequently, he was found to have developed right hemiparesis and global aphasia. Brain imaging revealed large infarcts in bilateral middle cerebral artery (MCA) territories. We report this as a unique case of viper bite which presented to the emergency room with status epilepticus. Moreover, bilateral MCA infarct, as was found in this case, is genuinely rare in scientific literature. Finally, the absence of overt features of envenomation makes this case stand out from other similar reported occurrences.

Keywords: Infarct, middle cerebral artery, status epilepticus, viper bite, Infarctus, artère cérébrale moyenne, état de mal épileptique, morsure de vipère

Résumé

En raison de la propriété antihémostatique du venin de vipère, les complications hémorragiques, y compris l’hémorragie intracérébrale, sont les plus courantes. rencontré après morsure de vipère. Des AVC ischémiques ont rarement été signalés après une envenimation par vipère, et son apparition a été attribuée à mécanismes multiples Les crises d’épilepsie postnakebite se produisent après une piqûre neurotoxique. Ici, nous rapportons le cas d’une victime de morsure de vipère qui état de mal épileptique dans les trois heures suivant la piqûre des vipères. Il ne présentait que de légers signes d’envenimation locale et un temps de coagulation du sang total prolongé était la seule manifestation de l’envenimation systémique. Par la suite, il s’est avéré avoir développé une hémiparésie droite et une aphasie globale. L’imagerie cérébrale a révélé de grands infarctus dans les territoires bilatéraux de l’artère cérébrale moyenne (ACM). Nous rapportons cela comme un cas unique de morsure de vipère présenté à la salle d’urgence avec le statut épileptique. De plus, l’infarctus bilatéral à MCA, comme on l’a constaté dans ce cas, est vraiment rare dans littérature scientifique. Enfin, l’absence de caractéristiques évidentes d’envenimation fait que ce cas se distingue des autres cas similaires

INTRODUCTION

Snake envenomation is an important public health hazard in the developing countries, and it continues to be one of the major contributors for morbidity and mortality in India. The most common cause of snakebite in India is due to viper species. Snakes of Viperidae family produce venoms with a wide range of activities mainly affecting hemostasis. Systemic envenomation is a complex phenomenon that manifests as hematological, renal, cardiac, and neurological abnormalities. Intracerebral hemorrhage is the most commonly encountered cause of stroke after viper bite, and it has aptly been attributed to the antihemostatic property of viper venom. Rare presentation with ischemic stroke has also been reported in literature, and multiple mechanisms are held responsible for the development of cerebral infarct after viper bite. Although seizure as a delayed complication has been reported, early-onset seizure after viper envenomation is exceedingly rare. We report here a case of viper bite victim who developed status epilepticus within 3 h of bite, on his way to our center, and was later found to have multiple cerebral infarcts.

CASE REPORT

A 50-year-old male patient was brought to the emergency room in status epilepticus. The patient did not have any preexisting comorbidities and never ever had any seizure before the present episode. As per description of his relatives, 3 h back, he was bitten by a viper on the second toe of his left lower limb while he was at work in the field. On his way to hospital, generalized convulsive seizure set in and continued to occur at frequent intervals. Intravenous phenytoin, as per guidelines, was loaded immediately in the emergency room. Seizures subsided after he received another half-loading dose of injection phenytoin, leaving him in postictal confusion. After regaining consciousness, he was found to have developed right-sided upper- and lower-limb weakness and facial deviation to the left and global aphasia. The site of bite revealed minimal reaction in the form of fang marks and small swelling. There was no active bleeding and the patient was hemodynamically stable with blood pressure of 110/76 mmHg. His whole blood clotting time (WBCT) on admission was 28 min. Twenty vials of polyvalent anti-snake venom were given the following standard guidelines. His WBCT returned to 18 min when it was measured after 6 h. The routine blood and urine parameters were as follows – hemoglobin – 10.2 g/dL; total leukocyte count – 6700/cubic mm; platelets – 2.6 lakh/cumm; urea – 26 mg/dL; creatinine – 0.9 mg/dL; prothrombin time – 11.2 s (11–15 s); activated partial thromboplastin time – 35.4 s (35–40 s); liver function test – within normal limits; and urine – few red blood cells. D-dimer level in blood was 610 ng/mL (110–250 ng/mL). Serum fibrinogen, antithrombin, protein C, and protein S levels were found to be within normal limits. Serum lipid profile did not reveal any abnormality. Electrocardiography and echocardiography were within normal limits.

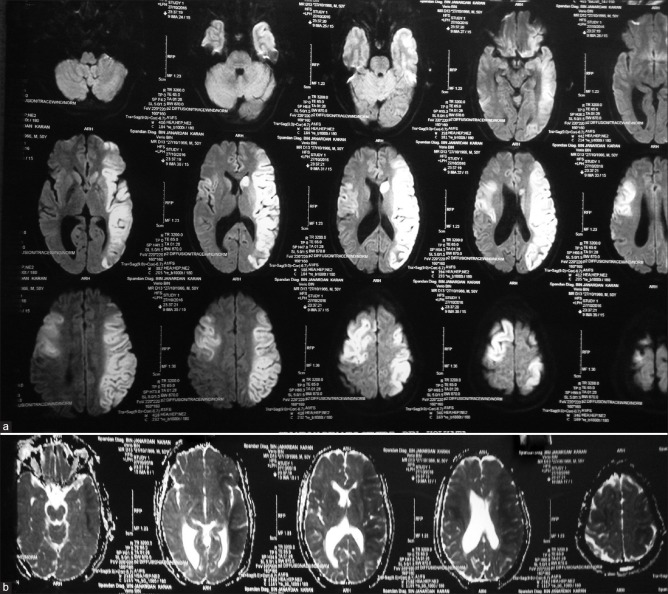

Brain imaging was performed around 6 h after the bite, to look for structural brain lesions. Computed tomography [Figure 1] revealed multiple areas of hypodensity in bilateral middle cerebral artery (MCA) territories, involving caudate nucleus and parietotemporal cortex on the left side and frontoparietal cortex on the right side. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain [Figure 2a and b] was subsequently performed on the 3rd day after admission, and it revealed acute infarction involving more than two-third of the left MCA territory along with small infarct in the right MCA territory (involving parietal cortex). As the patient's clinical condition started to deteriorate at the time of performing MRI (brain), vascular imaging could not be done at that time and he was rushed back to critical care unit. After resuscitation at critical care unit, his condition started to improve slowly. His renal function did not become deranged throughout the course of his hospital stay. Among the coagulation parameters, D-dimer was the only one to have been found elevated in the initial evaluation. At the time of discharge, residual hemiparesis on the right side and global aphasia were persistent. On follow-up after 3 months, his global aphasia was improved into Broca's aphasia; however, motor deficit on the right side was persistent.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography revealed multiple areas of hypodensity in the bilateral middle cerebral artery territories, involving caudate nucleus and parietotemporal cortex on the left side and frontoparietal cortex on the right side

Figure 2.

(a and b) Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain (diffusion-weighted imaging and apparent diffusion coefficient) revealed acute malignant infarction in the left middle cerebral artery territory along with small infarct in the right middle cerebral artery territory (involving parietal cortex)

DISCUSSION

Cerebral infarction following snakebite is an uncommonly reported cause of stroke. Mosquera et al. in their study reported only eight patients (2.6%) with cerebrovascular complications following snakebite (7 hemorrhagic and 1 ischemic).[1] Ischemic stroke is reported in 9 of 500 victims after envenoming in a report from Sri Lanka.[2]

Snake venom is a complex fluid containing procoagulant enzymes (protease, collagenase, and phospholipases) that are thrombin like and activate the coagulation cascade causing consumption of clotting factors and subsequently form intravascular fibrin thrombi. This causes consumptive coagulopathy and leads to bleeding. Viper venom also contains several anticoagulant proteins that activate factors V, IX, X, and XIII or cause fibrinolysis and subsequently hemorrhage. Due to this “pro-bleeding” milieu, the common neurological manifestations are due to intracerebral hemorrhage. However, various mechanisms have been proposed for the rare occurrence of infarction.[2,3,4,5]

Hypotension may be due to excessive sweating, vomiting, and increased vascular permeability due to the release of vasogenic agents or adrenal hemorrhage

Endothelial injury by direct action of the components of viper venom on vessel wall may produce vasculitis and local thrombosis

Hypercoagulability may be due to hypotension or procoagulants in the venom such as arginine, esterase, and hydrolase

Hemorrhagins are complement-mediated toxic components of Viperidae that causes intense vasospasm followed by vasodilatation, while at capillary level, they cause increased vascular permeability, resulting in hemorrhagic infarct

Direct cardiotoxic effects of venom could lead to dysrhythmias, causing cardiac thromboembolism.

In our case, the patient did not develop any hypotensive episodes throughout the course of his illness and the infarcts also did not conform to watershed zones. Evidence of direct cardiotoxicity was lacking in this case and such large vessel stroke cannot be attributed to embolism only. Thus, procoagulant state (evidenced by raised D-dimer level) and endothelial injury caused by viper venom can be a plausible explanation of in situ vascular thrombosis in this case. However, the rapidity of thrombotic occlusion in this case hints toward some additional contributor. We believe that hemorrhagin-mediated vasospasm might have been an added factor here, although hemorrhagic infarct would fit better in that situation. Hence, interplay of multiple factors seems to have caused the vascular thrombotic occlusion. It is curious that the venom which caused infarcts of such magnitude in the brain produced only minimal signs of local envenomation. This apparent paradox can be addressed by bringing into consideration the components of venom. We may go on to comment that, besides dosage, the composition of venom is an important determinant of ischemic stroke after viper bite. This might explain why ischemic stroke is a rarity even in those cases which have other florid signs of systemic envenomation.

Among the reported cases of ischemic stroke after snakebite, single arterial territory involvement was the most commonly found.[5,6,7,8,9,10] Bilateral anterior cerebral artery territory infarct was found in one of the cases. Involvement of bilateral MCA with a malignant infarct on the left side, as in the index case, is an exceedingly rare scenario.

Seizure as a form of neurotoxicity after snakebite has been reported earlier.[11,12] However, status epilepticus as the presenting manifestation in the emergency room after viper bite is an altogether atypical situation. There could be two possible mechanisms of seizure in this case – first, rapidly developing multiple cortical infarcts resulting from venom-induced widespread endothelial injury, and second, seizure-inducing capacity of the venom itself. Available literature shows that venom of mamba snakes can induce seizure due to the presence of dendrotoxin-K.[13,14] However, till date, no such report is available in favor of viper venom. Since the signs of local envenomation were mild in our case, the history of bite proved to be crucial here. This case exemplifies the importance of considering snakebite in nonepileptic patients presenting with status epilepticus, if any suggestive history is available.

CONCLUSION

Our case exemplifies the interplay of multiple factors – including procoagulant state, endothelial damage, and vasospasm – which give rise to vascular thrombosis after viper bite. Furthermore, this case depicts the fact that composition of venom, besides its dosage, is a potentially important determinant of ischemic stroke. Finally, this patient, who came with status epilepticus, alerts us to a rare presentation after viper bite.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mosquera A, Idrovo LA, Tafur A, Del Brutto OH. Stroke following Bothrops spp. Snakebite. Neurology. 2003;60:1577–80. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000061614.52580.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas L, Tyburn B, Ketterlé J, Biao T, Mehdaoui H, Moravie V, et al. Prognostic significance of clinical grading of patients envenomed by Bothrops lanceolatu in Martinique. Members of the research Group on snake Bite in Martinique. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92:542–5. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(98)90907-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panicker JN, Madhusudanan S. Cerebral infarction in a young male following viper envenomation. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48:744–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boviatsis EJ, Kouyialis AT, Papatheodorou G, Gavra M, Korfias S, Sakas DE, et al. Multiple hemorrhagic brain infarcts after viper envenomation. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68:253–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paul G, Paul BS, Puri S. Snake bite and stroke: Our experience of two cases. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2014;18:257–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.130585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Narang SK, Paleti S, Azeez Asad MA, Samina T. Acute ischemic infarct in the middle cerebral artery territory following a Russell's viper bite. Neurol India. 2009;57:479–80. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.55594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mugundhan K, Thruvarutchelvan K, Sivakumar S. Posterior circulation stroke in a young male following snake bite. J Assoc Physicians India. 2008;56:713–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pal J, Mondal S, Sinha D, Ete T, Chakraborthy A, Nag A, et al. Cerebral infarction: An unusual manifestation of viper snake bite. Int J Med Sci. 2014;2:1180–3. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sebastine C, Athale N, Ghanekar J, Hegde S. Anterior circulation stroke following snake bite: A rare presentation. MGM J Med Sci. 2014;1:143–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gouda S, Pandit V, Seshadri S, Valsalan R, Vikas M. Posterior circulation ischemic stroke following Russell's viper envenomation. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2011;14:301–3. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.91957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seneviratne U, Dissanayake S. Neurological manifestations of snake bite in Sri Lanka. J Postgrad Med. 2002;48:275–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeyarajah R. Russell's viper bites in Sri Lanka. A study of 22 cases. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1984;33:506–10. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1984.33.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bagetta G, Iannone M, Palma E, Nisticò G, Dolly JO. N-methyl-D-aspartate and non-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors mediate seizures and CA1 hippocampal damage induced by dendrotoxin-K in rats. Neuroscience. 1996;71:613–24. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00502-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bagetta G, Nisticó G, Dolly JO. Production of seizures and brain damage in rats by alpha-dendrotoxin, a selective K+channel blocker. Neurosci Lett. 1992;139:34–40. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90851-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]