Abstract

Limited health literacy is a common but often unrecognized problem associated with poor health outcomes. Well-validated screening tools are available to identify and provide the opportunity to intervene for at-risk patients in a resource-efficient manner. This is a multi-method study describing the implementation of a hospital-wide routine health literacy assessment at an academic medical center initiated by nurses in April 2014 and applied to all adult inpatients. Results were documented in the electronic health record, which then generated care plans and alerts for patients who screened positive. A nursing survey showed good ease of use and adequate patient acceptance of the screening process. Six months after hospital-wide implementation, retrospective chart abstraction of 1455 patients showed 84% were screened. We conclude that a routine health literacy assessment can be feasibly and successfully implemented into the nursing workflow and electronic health record of a major academic medical center.

Keywords: Health Literacy Screening, Hospital Implementation, Inpatient Assessment

INTRODUCTION

The 1992 National Adult Literacy Survey (NALS) reported that 90 million adult Americans were either functionally illiterate or could not read above a 5th grade level.1 The 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) found no significant difference.2 Given the difficulty of comprehension of medical information even for highly educated individuals, the number of adults with limited health literacy would be expected to be significantly higher than the number with limited basic literacy.3 Health literacy can be defined as the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.4 Current estimates of the burden of limited health literacy range from 15% to over 50%,3,5–9 depending on the study. A large systematic review from 2005 on the prevalence of limited health literacy demonstrated a weighted prevalence of 26% (95%CI, 22–29%), but as high as 68%.10 Not only is such prevalence high, identification of limited health literacy is confounded because patients are unlikely to know or, more importantly, disclose their limited health literacy status.11

Limited health literacy is associated with numerous poor health outcomes including hospital readmissions, increased emergency department visits, and excess morbidity and mortality.9,12–16 There is an abundance of literature on well-validated screening tools for health literacy,17,18 and studies of interventions aimed at improving health outcomes for those with limited health literacy are beginning to show promise.19,20 The Institute of Medicine recommended in 2004 that health literacy assessment be incorporated into health care information systems.3 However, experts in the field today generally recommend a universal precautions approach, which advocates improved communication for all patients, in which case screening is not necessary.21–25

We agree with those who advocate universal precautions since all patients, regardless of literacy status, benefit from more explicit and improved health communication.26 However, we propose that patients with low health literacy represent a uniquely vulnerable population who would benefit from identification and more robust intervention. Published accounts on this topic are scarce. There is only one report in the literature on routine health literacy screening at a large medical center.27,28 As a safety net institution, the bedside nurses and hospitalists at our center were acutely aware of the problem of limited health literacy, and so together we formed a “grass roots” Health Literacy Project Team. One of our aims was to develop, implement, and evaluate a fully integrated hospital-wide process for health literacy screening. Here we describe the implementation and preliminary outcomes.

METHODS

This is a descriptive study of a health literacy screening pilot followed by initiation of a hospital-wide screen which is ongoing today. We also present results of a nursing survey conducted during the pilot and a chart abstraction where we assessed nursing compliance with the large-scale screening effort. Our intervention was conducted at XXXXX Hospital, a 900-bed major tertiary care academic medical center that serves as a referral center for the XXXXX geographic area. In the fall of 2012, we assembled a multi-disciplinary Health Literacy Project Team comprised of professionals representing the Departments of Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy, Social Work Services, the Health Science Center Libraries, Information Technology, Home Health, and Ambulatory Clinic Services. In December 2014, we received approval from the XXXXX Institutional Review Board, Committee IRB-01, to conduct a Retrospective Data/Chart Abstraction, allowing us to analyze data regarding our implementation of a health literacy screen at our institution.

Screening Tool

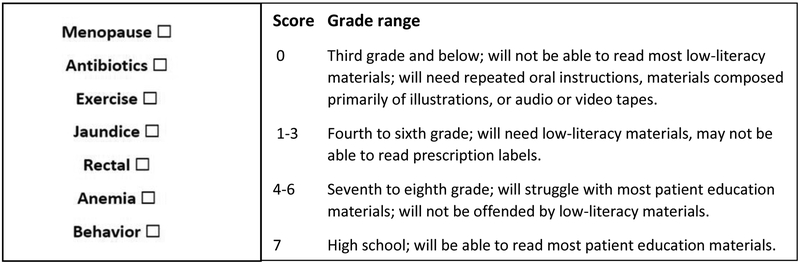

One of the initial steps in our intervention was to select a health literacy screening tool. The Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) is one of the oldest and most widely used health literacy assessment instruments.29 We selected the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine – Short Form (REALM-SF).30,31 This 7-item tool has been validated and field tested in diverse research settings and has excellent agreement with the longer 66-item REALM instrument.21 Bedside nurses were included on the Health Literacy Project Team and were instrumental in the selection of the REALM-SF, which was chosen due to its ease of use. The REALM-SF scoring tool and corresponding grade-level assignments are illustrated in Figure 1.21,30,31 We elected to define patients with a REALM-SF score of 7 as possessing “Adequate” health literacy, and patients with a score of 6 or below as possessing “Limited” health literacy.

Figure 1:

REALM-SF Form with Corresponding Grade-Level Assignments

Abbreviation: REALM-SF, Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine-Short Form

Screening Process

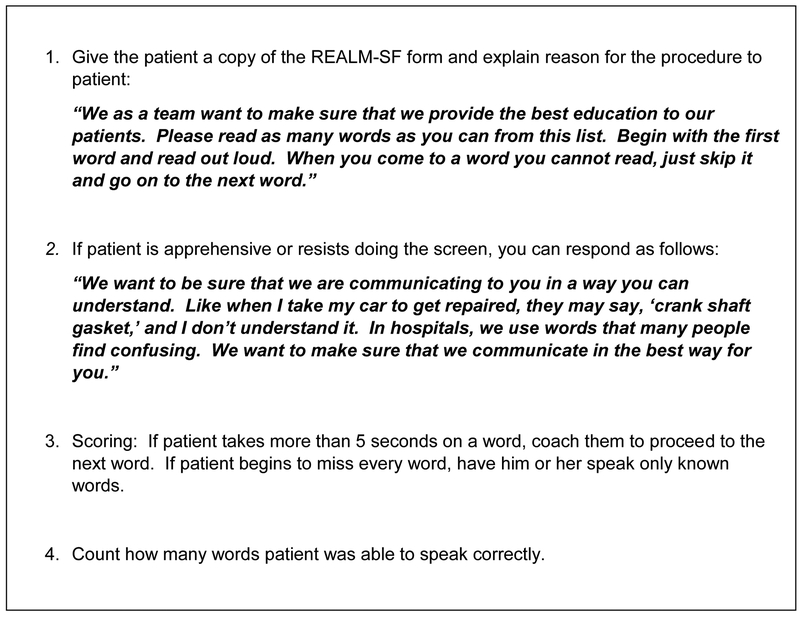

During the admission intake process the bedside nurse checks to see if the patient was previously screened. If not, the nurse uses scripting developed by our project team (Figure 2) to guide the discussion and ask the patient to pronounce the 7 words listed in the REALM-SF. Both the scripting and the 7 words are printed on a laminated card attached to the computer on wheels. If the patient pronounces all the words correctly, then the nurse clicks the “Adequate Health Literacy” button. If the patient is unable to pronounce one or more words, then the nurse clicks the “Limited Health Literacy” button.

Figure 2:

Scripting for Administration of the REALM-SF Screening Tool by Nurses

Abbreviation: REALM-SF, Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine-Short Form

Pilot Use of REALM-SF Screening Tool

Prior to the implementation of hospital-wide health literacy screening, we elected to pilot the use of the REALM-SF screening tool on a single adult medical surgical unit from November 2013 through February 2014. This is a 36-bed unit staffed with a total of 42 full-time and part-time nurses. We conducted this pilot to assess the ease of use, as well as nurse and patient acceptability of the screening tool in the inpatient setting. We also sought to gain the nurses’ feedback regarding recommended improvements. We chose this unit because the unit manager was one of our first strong advocates for health literacy. A resource nurse provided education to unit nurses. She also provided laminated cards for nurses to administer the tool. No additional unit staff or equipment were required for the pilot or the hospital-wide implementation. A five-question survey was designed by nursing leadership, and administered by Survey Monkey® 32 to assess the nursing staff’s use of the REALM-SF and their understanding of interventions. On this pilot inpatient medical unit, we surveyed 246 patients and found a limited health literacy prevalence of 36%.

Nursing Survey

We surveyed nurses from our pilot medical unit regarding their use of the REALM-SF for screening of health literacy. Nurses were educated regarding the use of the tool and were provided scripting to enhance patient engagement. The survey was administered to 42 nurses after they had used the REALM tool with their inpatients for at least 2 weeks. Twenty-six nurses completed the survey, for a response rate of 62%. The survey results are noted in Table 1. Nurses were asked to score each question as per a standard 5-point Likert scale. The highest scores were for understanding the significance of the intervention (4.6), ease of use of the tool (4.7), and understanding how to document (4.9). The lowest scores were for patient receptivity (3.8) and comfort in administrating the tool (4.1). Based on this feedback we edited the instructional content provided to nurses including the scripting used for patients.

Table 1:

Nursing Survey Regarding Administration of the REALM-SF and Interventions

| 1. | The REALM-SF assessment tool is easy to administer. | 4.7 |

| 2. | I feel comfortable administering the REALM-SF assessment tool. | 4.1 |

| 3. | I understand how to document the REALM-SF in EPIC. | 4.9 |

| 4. | I understand the significance of the suggested interventions. | 4.6 |

| 5. | Patients are receptive when I assess health literacy. | 3.8 |

5 – Agree; 4 – Somewhat Agree; 3 – Neutral; 2 – Somewhat Disagree; 1 - Disagree

Abbreviation: REALM-SF, Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine-Short Form

Incorporating the Screening Tool into our Electronic Health Record

Our goal was for the results of the REALM-SF screening tool to be available to all patient care providers in all units and clinics within the XXXXX system. The process described below was developed and communicated to all RNs via a required Education Update utilizing the HealthStream® online education system33:

The bedside nurse will administer the REALM-SF screening tool to all patients age 18 and older upon admission. Next, the nurse will select “Limited,” “Adequate,” or “Unable to Assess” in the Health Literacy Assessment section of the “Admission Navigator” screen within our EHR system (Epic Systems Corporation).34 The actual REALM-SF score will be documented in the comments section. When “Limited” Health Literacy is selected, a Best Practice Advisory (BPA) will fire the first time each provider accesses the patient’s chart for each encounter, which serves to notify physicians and staff of the patient’s limited health literacy status. The FYI field is then automatically populated with the patient’s health literacy status, which then carries over to all hospital, clinic, and home health encounters with the same patient. The FYI field is located in the top banner of the patient’s chart where other essential information such as patient’s name, code status, and room location is listed. Additionally, a specifically designed limited health literacy Care Plan Problem within Epic is automatically added to the patient’s overall Care Plan. The Health Literacy results will display in the Nursing Discharge Navigator. Once the Health Literacy Assessment/REALM-SF score is documented in Epic, the patient will not need to be rescreened during subsequent hospital or clinic encounters.

Designing a Care Plan for Patients Identified as Possessing Limited Health Literacy

Once individuals of limited health literacy within our hospital were identified, we sought to develop a focused care plan for this patient population throughout their stay, and especially during the discharge process. Care plan elements designed for the limited health literacy patient, based on our project team recommendations, included the following:

Encourage patient to verbalize preferred learning strategy

Provide education in preferred learning strategy

Provide education in preferred language

Avoid medical terminology

Provide easy to read education materials with pictures and/or drawings

Limit the amount of education at one time. Use repetition.

Use teach-back to determine patient understanding of education provided

Provide shame-free environment

Encourage family/caregiver to be at teaching sessions

Encourage patient to ask questions

Hospital-wide Implementation of the Health Literacy Screen

The adverse health consequences associated with limited health literacy and the availability of validated health literacy screening tools are well established in the literature, thus, building a case for this project was not difficult. We engaged the interest of our Chief Nursing Officer and Chief Informatics Officer, which proved to be critical to the success of our initiative. They committed necessary resources for the training of nursing staff and building of the health literacy modules into our EHR. Physician leadership and support was provided by the Department of Medicine Vice Chair of Clinical Affairs, who chaired the Health Literacy Project Team which started meeting in November 2012. Equally important was the intrinsic enthusiasm and dedication of front line staff and unit leaders across the institution.

Demographic information, including race, ethnicity, and payor mix, was included to demonstrate the breadth of diversity of the population studied. Demographic data was obtained from the hospital patient registry, and was routinely collected by the clerk at the time of admission for all patients. Hospital-defined classifications for race were: American Indian, Asian, Black, Hispanic, Multiracial, White, Other, Unknown, and Patient Refused. We combined the following classifications into the “Other” category: American Indian, Hispanic, Multiracial, Other, Unknown, and Patient Refused. Hospital-defined classifications for ethnicity were: Hispanic, Not Hispanic, Unknown, and Patient Refused. We combined the following classifications into the “Other” category: Unknown and Patient Refused.

Institutional Review Board Approval

The XXXXX Institutional Review Board, Committee IRB-01 approved the study protocol (IRB2014XXXXX).

RESULTS

Prevalence of Limited Health Literacy on Hospital Units

Data was collected retrospectively on 1455 inpatients from 9 representative floor units during the time period September 23, 2014 through October 20, 2014. Demographic information related to this patient population is presented in Table 2. The average age of this patient group was 54 years (with age ranging from 18 to 100 years). Sixty-two percent of these patients were female. Sixty-seven percent of patients were white, 26% were black, 1% were Asian, and 6% were categorized as “other.” Regarding payer status, 45% of patients were covered by Medicare/Medicare HMO, 22% were covered by Medicaid/Medicaid HMO, 16% had commercial coverage, 7% had managed care coverage, 8% were self-pay, and 2% were categorized as “other.”

Table 2:

Health Literacy – REALM-SF Demographic Data

Patients Admitted September 23 - October 20, 2014

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Patients | 1455 | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 65 | 5% |

| Not Hispanic | 1371 | 94% |

| Other | 19 | 1% |

| Race | ||

| Asian | 12 | 1% |

| Black | 382 | 26% |

| White | 970 | 67% |

| Other | 91 | 6% |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 895 | 62% |

| Male | 560 | 38% |

| Age | ||

| 18–30 | 255 | 18% |

| 31–50 | 333 | 23% |

| 51–70 | 572 | 39% |

| 71 + | 295 | 20% |

| Payer | ||

| Commercial | 238 | 16% |

| Managed Care | 98 | 7% |

| Medicaid & Medicaid HMO | 318 | 22% |

| Medicare & Medicare HMO | 652 | 45% |

| Self Pay | 118 | 8% |

| Other | 31 | 2% |

Abbreviation: REALM-SF, Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine-Short From

Health literacy assessment results are presented in Table 3. The average REALM-SF screening compliance was 84% (individual unit compliance ranged from 61% to 94%). The average prevalence of limited health literacy was 16% (95% CI 13–18%). Individual unit prevalence ranged from 5% to 32%. We noted lower screening compliance rates on our Surgery and Urology units (average 63%). We observed lower prevalence of limited health literacy on our Surgery, Orthopaedics, Labor/Delivery, and one of our General Medical units (average 8%).

Table 3:

Health Literacy – REALM-SF Compliance and Prevalence Data

Patients Admitted September 23 - October 20, 2014

| Compliance With Use of Tool | Prevalence of Health Literacy Levels | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admitted (#) |

Screened (#) |

Screened (%) |

Adequate | Limited | Unable to Assess |

||||||

| (%) | (%) | (%) | |||||||||

| General Medicine, South Wing | 149 | 129 | 87% | (83%) | (9%) | (8%) | |||||

| General Medicine, East Wing | 141 | 131 | 93% | (80%) | (14%) | (6%) | |||||

| General Medicine Teaching | 175 | 143 | 82% | (64%) | (32%) | (4%) | |||||

| Family Medicine | 224 | 202 | 90% | (68%) | (26%) | (6%) | |||||

| Cardiology | 149 | 137 | 92% | (82%) | (18%) | (0%) | |||||

| Surgery | 159 | 97 | 61% | (89%) | (9%) | (2%) | |||||

| Labor and Delivery | 201 | 189 | 94% | (95%) | (5%) | (0%) | |||||

| Orthopaedics | 132 | 110 | 83% | (89%) | (7%) | (4%) | |||||

| Urology | 125 | 82 | 66% | (88%) | (12%) | (0%) | |||||

| TOTAL | 1455 | 1220 | 84% | (81%) | (16%) | (3%) | |||||

Abbreviation: REALM-SF, Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine-Short Form

LIMITATIONS

Not surprisingly, we noted variability in how often the assessment tool was used (average compliance 84%, range 61% to 94%). We also noted variability in the prevalence of limited health literacy among our various units (average limited health literacy prevalence 16%, range 5% to 32%). The variability in both measures could be due to a number of factors. One factor may be the presence of different populations of patients. For instance, patients admitted for elective procedures may have higher health literacy, which could reduce nurses’ motivation to screen. Another factor may be different levels of engagement by units. For example, medicine units were better represented at planning meetings. A third factor might be differences in nurses’ readiness for change, due to such factors as change in unit leadership or other unit disruptions. Finally, some variability may be explained by cultural factors, which include leadership styles and early versus late adopters.

Challenges experienced during this implementation included nursing concerns regarding the addition of yet another task and another data point for documentation in a system already overburdened by such. Nonetheless, our pilot survey data revealed nurses understood the importance of screening and felt competent in administering the tool. Moreover, as noted above, nursing compliance with using the screening tool was good. Nursing assessment of patient receptivity to the screening tool was not as strong as their own confidence in using the tool. Based on this feedback, we incorporated enhancements to the scripting, and further assessments of patient satisfaction are now underway. Another challenge was how to accurately categorize limited English proficiency patients since this screen is only indicated for English speaking patients. We are now in the process of modifying the list of screening assessment choices in the Admission Navigator to include “Non-English Speaking” so nurses may properly categorize these patients. Since the prevalence of limited English proficiency is only 2% at our hospital, we feel the inclusion of these patients did not significantly impact our outcomes. Of note, our institution routinely provides certified interpreters when clinicians interact with non-English speaking patients. When possible, these interpreters also help translate written material. Assessing the health literacy of non-English speaking patients is also important but currently beyond the scope of this project.

DISCUSSION

Limited Health Literacy is commonplace and associated with poor health outcomes. What makes this problem more challenging is that patients are unlikely to know or disclose their limited health literacy status. However, practical screening tools are now available and intervention studies are beginning to show promise.17–20 We describe the implementation of a health literacy screen at a large academic medical center.

Our project occurred in four stages. First, we recruited the support of the Chief Nursing Officer and the Chief Informatics Officer. Second, we piloted the health literacy screening tool where staff found the tool practical and acceptable to patients. Third, we provided hospital-wide education for nurses on use of the health literacy screen and its related care plan intervention. Fourth, we incorporated the health literacy screen and care plan into our EHR. When a patient screens positive for limited health literacy, two automated responses are triggered: a one-time alert upon chart entry for all users each hospital encounter, and a nursing care plan containing relevant educational recommendations. Implementation of the entire screening process, including all educational and management components, occurred without new direct expense (i.e. no capital or new salary support was requested), grant support, or other external funding. We believe this increased the generalizability of our results since we showed the program can be implemented without significant cost or outside support. Alternatively, we have not yet explored the costs associated with interventions for limited health literacy, but by focusing interventions only on those who most need them, we will reduce the cost and nursing burden associated with universal precautions.23 A detailed account of our interventions for limited health literacy is beyond the scope of this paper. Future studies carefully detailing the impact of health literacy efforts on readmissions, HCAHPS, and other quality metrics will be necessary to define the true economic impact of this work.

Retrospective chart abstraction of 1455 patients from 9 non-ICU units showed average screening compliance to be 84%. We were satisfied with this rate since screening upon admission is often not feasible for patients initially admitted to the intensive care unit and then transferred to the floor. Similarly, patients admitted postoperatively are not easily screened due to residual anesthetic effect, which may explain the lower screening rates observed on surgical units. A transfer screening process and pre-operative screening process are both underway and will be monitored to assess the impact on screening rates. Our chart abstraction showed an average limited health literacy prevalence of 16%, which is on the lower end of published accounts (range 15% to > 50%)3,5–9 and suggests the application of our tool may need refinement. A recent well-performed implementation study also showed challenges with fidelity when scaling a health literacy assessment across a similar academic medical center.27 Optimal application of a tool or process is strongly influenced by the institutional commitment given to the initiative. Consequently, the accurate detection of limited health literacy may mostly be an operational issue. However, it is also possible that the acute care inpatient environment may bias the screening process. Nurses may be more distracted or the patients too ill to fully participate. Consequently, it will be important to compare the effect of these different screening environments as we expand our project to the outpatient environment.

CONCLUSIONS

We conclude that a routine health literacy assessment can be feasibly and successfully implemented into the nursing workflow and electronic health record of a major academic medical center.

IMPLICATIONS.

Some may argue that our application of screening efforts is premature because intervention-based outcome data is limited. However, it is our experience that most healthcare providers value knowing whether their patient can read and understand the instructions they provide. Moreover, we feel the raised awareness of health literacy throughout our institution as a result of our screening initiative has become an important benefit in itself. Having established the feasibility of a hospital-wide health literacy screening program, we believe the stage is now set for subsequent studies to refine the tool, improve the efficiency of the processes, and evaluate effectiveness of interventions.

Source of Funding:

Carrie D. Warring, MBA, MHS is supported by the Gatorade Trust through funds distributed by the University of Florida, Department of Medicine. The funding source had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

This work supported in part by the NIH/NCATS Clinical and Translational Science Award to the University of Florida UL1 TR000064.

Biographies

Carrie D Warring, MBA, MHS earned Master’s degrees in Business Administration and Health Science from the University of Florida and completed her residency in Hospital Administration at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. She is the Quality Manager of the Department of Medicine at the University of Florida in Gainesville, FL. Her research focus is in Health Literacy and Inpatient and Outpatient Quality Improvement.

Jacqueline R Pinkney, MSW graduated from Florida State University earning Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in Social Work. She has extensive experience in working with low income and high utilizer populations. She is the Coordinator of Social Work Services for the UF Health Shands Hospital Care One Clinic in Gainesville, FL.

Elaine D Delvo-Favre, MSN, RN, RN-BC, NEA-BC is the Administrative Director of Nursing Quality and Regulatory Standards at UF Health Shands Hospital in Gainesville, FL. She is also the coordinator of the NICHE geriatric nursing program at UF Health. Her role is focused on improving system-wide nursing and patient quality outcomes guided by evidence-based practice.

Michelle Robinson Rener, MSN, RN is the clinical leader for a 36-bed medical/surgical unit at UF Health Shands Hospital in Gainesville, FL. Her clinical focus is on quality, research, and staff development, with a special interest in patient health literacy and avoidable readmissions.

Jennifer A Lyon, MS, MLIS, AHIP graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Madison with a Masters in Molecular Biology and from the University of North Carolina-Greensboro with a Masters in Library and Information Studies. She did her internship in medical librarianship at Vanderbilt University. She was a biomedical librarian at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and the University of Florida and is presently the Biomedical and Translational Research Librarian at Stony Brook University in Stony Brook, NY. She is a distinguished member of the Academy of Health Information Professionals.

Betty Jax, MSN, RN, ARNP, RN-BC is the former Administrative Director for Nursing Education at UF Health Shands Hospital in Gainesville, FL.

Irene Alexaitis, DNP, RN, NEA-BC is Vice President of Nursing and Patient Services and Chief Nursing Officer of UF Health Shands Hospital in Gainesville, FL. She is also the Associate Dean for Academic-Practice Partnerships at the University of Florida, College of Nursing. She has a particular interest in system-wide intra-professional collaboration and quality improvement to achieve optimal patient outcomes.

Kari Cassel, MBA is the Chief Information Officer at UF Health where she oversees Information Technology/Information Services for the UF Health Science Center and Shands Hospitals in Gainesville and Jacksonville, FL.

Kacy Ealy, BA graduated from the University of Florida and is a Business Development Representative at UF Health Shands HomeCare in Gainesville, FL. Her work focuses on education, growth, and development of home care services as well as the continuum of care and organizational processes between the acute care setting and post-acute services.

Melanie Gross Hagen, MD is an Associate Professor of general internal medicine at the University of Florida College of Medicine in Gainesville, FL. She is the medical director of an outpatient clinic and teaches communication skills and end of life care to medical students.

Erin M Wright, PharmD, BCPS is the Clinical Chief of Cardiovascular and Neuromedicine Clinical Pharmacy Services at UF Health Shands Hospital in Gainesville, FL. She has a particular interest in transitions in care and implementation of new, targeted programs in this area.

Myron Chang, PhD is a former Professor in the Department of Biostatistics at the University of Florida in Gainesville, FL, where he performed statistical research and provided statistical assistance to faculty members in the College of Medicine.

Nila S Radhakrishnan, MD is Assistant Professor of Medicine and Associate Chief for Hospital Medicine at the University of Florida College of Medicine in Gainesville, FL. Her areas of interest are quality and patient safety as well as inpatient medicine.

Robert R Leverence, MD is the Vice Chair of Clinical Affairs for the Department of Medicine and Chief of Hospital Medicine at the University of Florida in Gainesville, FL. His research focus is in the patient experience and systems improvement.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Carrie D Warring, University of Florida, Department of Medicine, Gainesville, FL.

Jacqueline R Pinkney, UF Health Shands Hospital, Gainesville, FL.

Elaine D Delvo-Favre, UF Health Shands Hospital, Gainesville, FL.

Michelle Robinson Rener, UF Health Shands Hospital, Gainesville, FL.

Jennifer A Lyon, Health Sciences Library, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York; formerly Health Science Center Libraries, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

Betty Jax, UF Health Shands Hospital, Gainesville, FL.

Irene Alexaitis, UF Health Shands Hospital, Gainesville, FL.

Kari Cassel, UF Health Shands Hospital, Gainesville, FL.

Kacy Ealy, UF Health Shands Hospital, Gainesville, FL.

Melanie Gross Hagen, University of Florida, Department of Medicine, Gainesville, FL.

Erin M Wright, UF Health Shands Hospital, Gainesville, FL.

Myron Chang, University of Florida, Department of Biostatistics, Gainesville, FL.

Nila S Radhakrishnan, University of Florida, Department of Medicine, Gainesville, FL.

Robert R Leverence, University of Florida, Department of Medicine, Gainesville, FL.

REFERENCES

- 1.NCED. 1992. National Assessment of Adult Literacy. https://nces.ed.gov/naal/nals_products.asp. Accessed 09/02/2014.

- 2.NCED. 2003. National Assessment of Adult Literacy. https://nces.ed.gov/naal/index.asp. Accessed 09/02/2014.

- 3.Kindig DA, Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion Committee on Health Literacy. Institute of Medicine; 2004; http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=10883. Accessed 09/02/2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ratzan S, Parker R. Introduction In: Selden C, Zorn M, Ratzan S, Parker R, eds. National Library of Medicine Current Bibliographies in Medicine: Health Literacy. NLM Pub. No. CBM 2000–1. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cordasco KM, Asch SM, Franco I, Mangione CM. Health literacy and English language comprehension among elderly inpatients at an urban safety-net hospital. J Health Hum Serv Adm. 2009;32:30–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olives T, Patel R, Patel S, Hottinger J, Miner JR. Health literacy of adults presenting to an urban ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;29:875–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sahm LJ, Wolf MS, Curtis LM, McCarthy S. Prevalence of limited health literacy among Irish adults. J Health Commun. 2012;17 Suppl 3:100–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Komenaka IK, Nodora JN, Machado L, et al. Health literacy assessment and patient satisfaction in surgical practice. Surgery. 2014;155:374–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirsh JM, Boyle DJ, Collier DH, et al. Limited health literacy is a common finding in a public health hospital’s rheumatology clinic and is predictive of disease severity. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17:236–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paasche-Orlow MK, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nielsen-Bohlman LT, Rudd RR. The prevalence of limited health literacy. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20(2):175–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, et al. The health care experience of patients with low literacy. Arch Fam Med. 1996;5(6):329–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell SE, Sadikova E, Jack BW, Paasche-Orlow MK. Health literacy and 30-day postdischarge hospital utilization. J Health Commun. 2012;17 Suppl 3:325–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, et al. Health literacy interventions and outcomes: an updated systematic review. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalichman SC, Pope H, White D, et al. Association between health literacy and HIV treatment adherence: further evidence from objectively measured medication adherence. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic). 2008;7(6):317–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murray MD, Tu W, Wu J, Morrow D, Smith F, Brater DC. Factors associated with exacerbation of heart failure include treatment adherence and health literacy skills. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;85(6):651–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiss BD, Palmer R. Relationship between health care costs and very low literacy skills in a medically needy and indigent Medicaid population. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2004;17(1):44–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collins SA, Currie LM, Bakken S, Vawdrey DK, Stone PW. Health literacy screening instruments for eHealth applications: a systematic review. J Biomed Inform. 2012;45:598–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nemmers TM, Jorge M. Clinical Assessment of Health Literacy. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation. 2013;29:89–97. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheridan SL, Halpern DJ, Viera AJ, Berkman ND, Donahue KE, Crotty K. Interventions for individuals with low health literacy: a systematic review. J Health Commun. 2011;16 Suppl 3:30–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clement S, Ibrahim S, Crichton N, Wolf M, Rowlands G. Complex interventions to improve the health of people with limited literacy: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75(3):340–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.AHRQ. Health Literacy Measurement Tools. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/literacy/index.html. Accessed 09/02/2014.

- 22.Bailey AN, Porter KJ, Hill JL, Chen Y, Estabrooks PA, Zoellner JM. The impact of health literacy on rural adults’ satisfaction with a multi-component intervention to reduce sugar-sweetened beverage intake. Health education research. 2016;31(4):492–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mabachi NM, Cifuentes M, Barnard J, et al. Demonstration of the Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit: Lessons for Quality Improvement. The Journal of ambulatory care management. 2016;39(3):199–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiss BD, Brega AG, LeBlanc WG, et al. Improving the Effectiveness of Medication Review: Guidance from the Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine : JABFM. 2016;29(1):18–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.AHRQ. Guide to Implementing the Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit: About This Guide http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/literacy-toolkit/impguide/impguide-about.html. Accessed 12/12/2016.

- 26.Brown DR, Ludwig R, Buck GA, Durham D, Shumard T, Graham SS. Health literacy: universal precautions needed. Journal of allied health. 2004;33(2):150–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cawthon C, Mion LC, Willens DE, Roumie CL, Kripalani S. Implementing routine health literacy assessment in hospital and primary care patients. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2014;40:68–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wallston KA, Cawthon C, McNaughton CD, Rothman RL, Osborn CY, Kripalani S. Psychometric properties of the brief health literacy screen in clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;29:119–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis TC, Crouch MA, Long SW, et al. Rapid assessment of literacy levels of adult primary care patients. Fam Med. 1991;23(6):433–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arozullah AM, Yarnold PR, Bennett CL, et al. Development and validation of a short-form, rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine. Med Care. 2007;45(11):1026–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25(6):391–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.SurveyMonkey®. SurveyMonkey® Website. https://www.surveymonkey.com/. Accessed 04/24/2015, 2015.

- 33.HealthStream®. HealthStream® Website. http://www.healthstream.com/. Accessed 04/24/2015, 2015.

- 34.Epic. Epic Systems Website. https://www.epic.com/. Accessed 04/24/2015, 2015.