Abstract

Background:

Studies have shown that parents have a significant influence on emerging adult college students’ drinking during the first year of college. Limited research has been conducted to address the question of whether parenting later in college continues to matter in a similar manner. The current study utilized a prospective design to identify associations between parental permissiveness toward alcohol use and monitoring behaviors and student drinking outcomes during the first and fourth years of college.

Methods:

Participants (N = 1,429) at three large public universities completed surveys during the fall semesters of their first (T1) and fourth years (T2) (84.3% retention). The study employed a structural equation model to examine associations between parental permissiveness of college student alcohol use, parental monitoring, student drinking, and consequences at T1 and T2, controlling for parental modeling of risky drinking, peer norms, sex, and campus.

Results:

Examination of the association between parenting and student drinking outcomes revealed: 1) Parental permissiveness was positively associated with drinking at T1 and again at T2; 2) Parental permissiveness had indirect effects on consequences via the effects on drinking at both times. Specifically, a one unit increase in parental permissiveness at T1 resulted in students experiencing 4–5 more consequences as a result of their drinking at T2; 3) Parental permissiveness was not associated with monitoring at T2; and 4) Both parental permissiveness and monitoring at T2 were associated with drinking at T2.

Conclusions:

The findings provide evidence for the continued importance of parenting in the 4th year of college and parents expressing low permissiveness toward student drinking may be beneficial to reducing risky drinking even as students turn 21.

Keywords: parental influence, college risky drinking, alcohol-related consequences

Introduction

Parents are notable influences on college students’ drinking-related behaviors (Borsari et al., 2007; Calhoun et al., 2018; Madkour et al., 2017; Turrisi et al., 2013). Studies have shown that specific parenting behaviors can reduce the effects of peer and environmental influences on risky drinking behaviors as well as directly influence students’ drinking behaviors (Mallett et al., 2011; Rulison et al., 2016; Wood et al., 2004). This is consistent with Social Learning Theory, which posits that important social referents, such as parents and peers, have an impact on individuals’ behaviors (Bandura and Walters, 1963). Studies have examined parental factors related to risky drinking (e.g., Wood et al., 2004); however, the majority of this work has focused on adolescents and first-year college students (e.g., Brown et al., 2008; Schulenberg and Maggs, 2002). Reviews of the literature focusing on adolescent and emerging adult substance use have highlighted the importance and value of parenting and have encouraged research using longitudinal multivariate methods to gain greater insights into the processes that might otherwise be missed (Chassin and Handley, 2006; Fromme, 2006; Van der Vorst et al., 2006b). The current study extends previous research by examining the influence of parental permissiveness and monitoring on college student drinking outcomes into the fourth year of college, once students have turned 21. While some students mature out of drinking during the later years of college, others demonstrate risky behavior well into their twenties (Hingson et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2013). Understanding the role of key parenting behaviors in relation to young adult risky drinking may provide practical information pertinent to intervention efforts.

For instance, research has consistently shown parental permissiveness to be a significant predictor of drinking across developmental windows (e.g., Koning et al., 2010; Koning et al., 2012; Van der Vorst et al., 2009). For example, using a within-family design, Van der Vorst and colleagues (2005) observed a negative relationship between parents enforcing strict rules about alcohol use and alcohol use among their 13–16 year old adolescents. Findings from subsequent work supported these findings while demonstrating that positive attachment between parents and adolescents did not significantly prevent drinking (Van der Vorst et al., 2006a). Taken together, these studies demonstrate the importance of parental permissiveness of adolescent alcohol use in relation to risky underage drinking.

Studies examining college students have also found specific parental permissiveness of alcohol use was associated with risky drinking and increased consequences in this age group (Abar et al., 2012; Patock-Peckham et al., 2011; Patock-Peckham and Morgan-Lopez, 2006; Rulison et al., 2016; Turrisi and Ray, 2010; Varvil-Weld et al., 2012; Walls et al., 2009). For example, a cross-sectional study by Patock-Peckham and colleagues (2001) was unique in that it studied gender differences and found differential associations for maternal and paternal permissiveness on college student self regulation and in turn, college drinking. Specifically, mothers’ permissiveness had a stronger influence on daughters’ behaviors and fathers had a stronger influence on sons’ behaviors. Varvil-Weld and colleagues (2012), using longitudinal methods, observed that students whose parents were pro-alcohol (permissive) were four times more likely to experience problematic consequences compared to students whose parents were anti-alcohol. Rulison and colleagues (2016) examined whether parental permissiveness of drinking was directly related with alcohol use and consequences or mediated through perceived peer approval of risky drinking. The study found perceived friend approval of drinking mediated some outcomes such as alcohol use and health-based consequences; however, perceived parental permissiveness of drinking was directly related with other consequences including academic problems and driving after drinking. Finally, Calhoun et al. (2018) utilized a four-year within- and between-person longitudinal design and found that college students’ perceptions of their parents’ permissibility toward drinking increased across college. Interestingly, perceived permissibility remained associated with risky drinking behavior even as students approached the legal drinking age.

Research has also reported associations between parental monitoring and drinking (e.g., Abar and Turrisi, 2008; Patock-Peckham et al., 2011; Reifman et al., 1998; Wood et al., 2004). Studies on emerging adults attending college have found parental monitoring influenced students’ peer selection (Abar and Turrisi, 2008). Students who reported higher levels of parental monitoring tended to associate with peers who engaged in fewer risky drinking practices, and as a result, drank less alcohol themselves. Patock-Peckham and colleagues (2011) observed gender-specific mediational relationships for parental monitoring such that higher rates of perceived paternal monitoring mediated the relationship between parenting style and consequence outcomes among female college students, while a similar pattern of findings emerged for maternal monitoring among males.

While studies have established associations between parenting and risky student behaviors as important factors early on in the transition to college (Patock-Peckham et al., 2006; Rulison et al., 2016; Varvil-Weld et al., 2012; Walls et al., 2009), there still is limited research to address the question of whether parenting later in college continues to matter in a similar manner (with the exception of Calhoun et al., 2018). The current study extends previous examinations of the associations between parental permissiveness, monitoring, and emerging adult risky drinking and consequences by utilizing: 1) a prospective design to address developmental differences between the first and fourth years of college; 2) both maternal and paternal behaviors (i.e., permissiveness of alcohol use, general and binge drinking monitoring); 3) statistical controls to account for peer normative influences on student drinking outcomes, which have been found to be reliable predictors of student drinking (e.g., Borsari and Carey, 2003; Larimer et al., 2004; Lewis and Neighbors, 2006; White et al., 2000); 4) sex differences at the level of the student; and 5) a geographically diverse sample of students, because a common limitation of college student drinking studies is that they tend to take place at one location and lack generalizability.

Based on previous work, we tested the following hypotheses: 1) higher parental permissiveness of alcohol use would be associated with riskier drinking and more problems at both time points; 2) parental permissiveness during the fourth year of college (T2) would mediate the effects of parental permissiveness during the first year of college (T1) on drinking at T2; 3) higher parental permissiveness would be associated with less monitoring at both time points; and 4) to extend previous work demonstrating the importance of monitoring in the first year of college, higher parental monitoring would be associated with lower student drinking and, in turn, lower consequences at T1 and T2. Finally, the present study included an examination of the moderating effect of sex differences of the student in the relationship between parental permissiveness and drinking at T2. Because past studies have observed mixed effects with regard to sex effects of parenting on college drinking and consequences (e.g., Patock-Peckham et al., 2011; Varvil-Weld et al. 2012) and limited studies exist on older adult student samples beyond the first year, these analyses were exploratory.

Materials and Method

Procedure and participants

Participants were 1,429 students enrolled in three large public universities located in the southeastern, northeastern, and northwestern United States for increased sample heterogeneity. At the initial assessment (fall semester first year; T1) participants were 18.21 (SD = .40) years old with the majority identifying as female (59.4%, n = 848) and Caucasian (74.2%, n = 1060). Other races included Asian (11.1%, n = 159), African American (4.7%, n = 67), and multi-racial (5.1%, n = 73). A total of 17.1% (n = 245) identified as Hispanic. Three years later (fall semester senior year; T2), participants were 21.11 (SD = .37) years old.

Participants were randomly selected from registrars’ lists at each university (N = 5226) in 2011 and 2012. Invitation letters explaining the purpose of the study, procedures, and compensation were mailed to all potential participants during the fall semester (T1) of their first year of college. Letters contained the URL to access the survey, along with a Personal Identification Number (PIN). Emailed invitations containing the same information, along with up to six emailed reminders, were also sent to potential participants’ university email addresses. Similarly, invitation letters and reminder messages were emailed to continuing participants during the fall semester of their senior (T2) year of college. The universities’ local institutional review boards approved all study procedures. Students received $25–30 for each assessment.

At baseline, 2,320 students (44.4% response rate) filled out baseline measures. Of those, 1,429 students (61.6%) met the eligibility criteria of: 1) being between the ages of 18–19, and 2) having at least one parent or guardian consent and complete baseline measures. A total of 1,204 students completed the T2 senior year assessment (84.3% retention rate). Of those participants, 89.3% were still enrolled in college. No differences were found within males or females when comparing those who did and did not complete T2 in regards to weekly or peak drinking. No differences were found in regards to race between those who did and did not complete T2.

Measures

All measures were assessed at the student level, which is consistent with the majority of studies examining parenting behaviors in relation to college drinking using similar methodologies (e.g., Varvil-Weld et al., 2012). Studies have shown that correspondence between parents and students is reliable (Varvil-Weld et al., 2013) and students’ perceptions of their parents’ behaviors are significantly associated with drinking-related outcomes (e.g., Patock-Peckham et al., 2011). Our measures have been selected based on item/scale analyses that identified factors with high alphas. All of the measures used in the study are correlated with constructs that are theoretically related (e.g., other parenting constructs, risky behaviors) and not significantly correlated with social desirability. We have included alphas for each measure used at both the T1 and T2 assessments (where applicable). To address outliers, we used procedures recommended by Tabachnick and Fidell (2013) and recoded scores outside the range (skewness values beyond +/− 2 and kurtosis values beyond +/− 5) to 3.29 times the standard deviation beyond the mean.

Parental monitoring.

Eight items from Abar and Turrisi (2008) and Wood and colleagues (2004) were used to assess different dimensions of perceived parental monitoring.

Four items were used to assess general monitoring. For example, 2 items assessed: “My mother tries to know where I go at night,” and “My mother tries to know what I do during my free time.” The same two questions were also asked replacing father in the items. Response options were on a 5-point scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Alphas for these items ranged between .83 - .84 for T1 and T2.

Four additional items were used to assess binge monitoring: “My mother asks me whether I am binge drinking,” and “My mother checks in with other sources (e.g., siblings) to see if I am binge drinking while in college.” The same two questions were also asked replacing father in the items. Response options were on a 5-point scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Alphas for these items ranged between .77 - .86 for T1 and T2.

Parental permissiveness of alcohol use.

Parental permissiveness of alcohol use was assessed using measures from Reifman et al. (1998) and Wood et al. (2004). Participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement with 4 items regarding their beliefs of their mothers’ and fathers’ approval of alcohol use on a 5-point scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). The items were: “My mother thinks it is okay if I drink alcohol on special occasions outside the home (e.g., at a friend’s party)” and “My mother doesn’t mind if I drink alcohol once in a while.” The same two questions were also asked replacing father in the items (alphas ranged .89 - .93 for T1 and T2).

Alcohol use.

A standard drink definition was included for all measures of alcohol use (i.e., 12 oz. beer, 10 oz. wine cooler, 4 oz. wine, 1 oz. 100 proof (1 ¼ oz. 80 proof) liquor).

Typical weekly drinking.

Using the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins et al., 1985), students indicated how many drinks they consumed on each day of a typical week within the past 3 months. Responses for each of the 7 days were summed across items to provide a composite score of total weekly number of drinks consumed (T1: α = .77; T2: α = .81).

Peak blood alcohol content (peak BAC).

Students reported the maximum number of drinks consumed on an occasion within the past month and the number of hours they spent drinking on that occasion using the Quantity/Frequency/Peak questionnaire (QFP; Dimeff et al., 1999; Marlatt et al., 1998). From their responses, peak blood alcohol concentration (peak BAC) was calculated following established guidelines (Dimeff et al., 1999; Matthews and Miller, 1979) to account for weight, sex, and time taken to consume alcohol.

Drinking consequences.

Alcohol-related consequences were measured using a combination of established scales. A 39-item questionnaire consisting of 35 questions adapted from the Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (YAACQ; Read et al., 2006) and 4 questions adapted from the Young Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Test (YAAPST; Hurlbut and Sher, 1992; Larimer et al., 1999) was used to measure drinking consequences. Participants were asked to indicate whether they had experienced a range of alcohol-related consequences in the past year (e.g., hangover, blackout, forced sex, etc.). Responses were measured on a 7-point scale ranging from no, not in the past year (0) to 11 or more times in the past year (6). Items receiving < 5% endorsement were excluded. Responses from the 32 items were summed to create a composite variable of consequences experienced in the past year (T1: α = .95; T2: α = .96).

Covariates.

The following covariates measured at T1 were added to the model in addition to the main variables of interest.

Demographics.

Due to the cross-regional locations of data collection, university campus was entered as a covariate in the model. Sex was included to assess gender differences.

Peer norms.

Participants were asked how much their closest friends approve of binge drinking. The single item, measured on a 5-point scale ranging from strongly disagree (−2) to strongly agree (2), asked “My closest friends would approve of me having [5/4 drinks, for males and females, respectively] or more drinks on one occasion”.

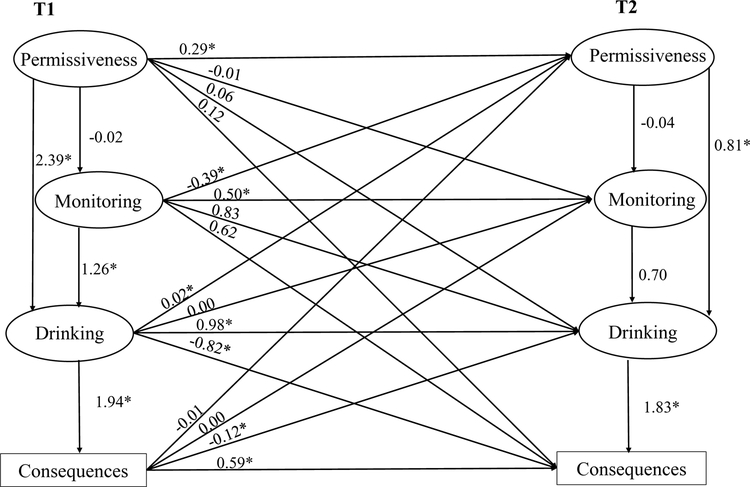

Analytic Strategy

The analyses addressed four main aims: 1) examine hypothesized relationships between parental permissiveness of alcohol use, student drinking, and consequences at both time points (see Figure 1 for all paths); 2) examine the longitudinal effects of parental permissiveness at T1 on permissiveness and drinking at T2; 3) examine the hypothesized relationships between parental permissiveness and monitoring at both time points; and 4) examine the hypothesized relationship between monitoring and drinking at T2. To do so, a saturated autoregressive cross-lagged model with latent constructs for parental permissiveness of alcohol use, parental monitoring, and drinking, and an observed consequence construct, at both T1 and T2, was examined using Mplus 8 (Muthén and Muthén, 2017). Covariates for sex, campus, and peer norms, on T2 drinking and consequences were also included in the model (covariates are not shown in Figure 1). The model was estimated using full-information maximum-likelihood estimates (FIML) to account for missing data estimates among the indicators, and maximum likelihood robust (MLR) to address the potential for non-normality in the data. The model also employed the negative binomial option for the consequence construct to account for potential concerns of an overdispersed count variable and a Monte Carlo integration with 2000 iteration points.

Figure 1. Structural Equation Model for T1 and T2.

Path model identifying prospective relationships between parental permissiveness, monitoring, and college student drinking and consequences during the first and fourth years of college.

Note: *p<.05

To determine mediation, we utilized the joint-significance test as identified by MacKinnon et al. (2002). The joint-significance test signifies mediation when both the alpha path (α; distal pathways) and beta path (β; proximal pathways) are significant, with the effect size of the mediated path identified as the product of both path coefficients (αβ).

Finally, the last aim of the study included an examination of the moderating effect of sex differences of the student in the relationship between permissiveness and drinking, and monitoring and drinking at T2. To do so, a separate model was examined where product terms involving sex and permissiveness and sex and monitoring on drinking at T2 were included. No significant effects were observed in these analyses. Thus, all the results are reported for the model that did not contain product terms.

Results

Descriptive Statistics.

All sample means and standard deviations of key variables are provided in Table 1. Parental monitoring significantly decreased from T1 to T2 while parental permissiveness significantly increased. Student drinking and consequences significantly increased from T1 to T2.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for parenting constructs and drinking outcomes.

| Item | T1 Mean (SD) | T2 Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monitoring | 2.94 (0.85) | 2.87 (0.89) | F(1, 130.04) = 4.88* |

| Permissiveness | 2.85 (1.24) | 3.86 (0.95) | F(1, 1290.63) = 862.48*** |

| DDQ | 5.17 (7.72) | 8.05 (8.80) | F(1, 1212.16) = 186.73*** |

| Peak BAC | 0.08 (0.10) | 0.10 (0.09) | F(1, 1299.73) = 35.25*** |

| Consequences | 10.89 (17.07) | 17.04 (21.72) | F(1, 1267.79) = 144.48*** |

Note:

p < .05,

p < .001.

T1=First year of college, T2=Fourth year of college.

Model Statistics.

The results of the saturated autoregressive cross-lagged model are shown in Figure 1, the full correlation matrix are provided in Tables 2a and 2b, and all the model path statistics are included in Table 3.1 The analyses of the hypotheses are described in turn.

Table 2a.

Correlation matrix of observed variables.

| T1 PermM1 |

T1 PermF1 |

T1 PermM2 |

T1 PermF2 |

T1 GMonM |

T1 GMonF |

T1 BDMonM |

T1 BDMonF |

T1 DDQ |

T1 BAC |

T1 Cons |

T2 PermM1 |

T2 PermF1 |

T2 PermM2 |

T2 PermF2 |

T2 GMonM |

T2 GMonF |

T2 BDMonM |

T2 BDMonF |

T2 DDQ |

T2 BAC |

T2 Cons |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1PermM1 | 1.00 | .823** | −.099** | −.103** | −0.03 | −.060* | .299** | .300** | .268** | .363** | .299** | −.092** | −.060* | −0.04 | −0.03 | .198** | .210** | .198** | ||||

| T1PermF1 | 0.81** | 1.00 | −.073** | −.122** | −0.01 | −0.05 | .314** | .311** | .284** | .316** | .352** | −.061* | −.068* | 0.01 | −0.03 | .234** | .230** | .225** | ||||

| T1PermM2 | 0.80** | 0.70** | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||||

| T1PermF2 | 0.67** | 0.80** | 0.82** | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| T1GMonM | −0.10** | −0.07* | −0.09** | −0.07* | 1.00 | .615** | .271** | .250** | −.084** | −.093** | −0.05 | −.076** | −.081** | .469** | .308** | .191** | .142** | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.05 | ||

| T1GMonF | −0.10** | −0.13** | −0.10** | −0.10** | 0.62** | 1.00 | .253** | .399** | −.064* | −.094** | −.071** | −.067* | −.069* | .333** | .430** | .153** | .182** | −0.01 | −0.03 | −.067* | ||

| T1BDMonM | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.03 | 0.27** | 0.25** | 1.00 | .761** | .077** | .058* | .075** | −.110** | −.084** | .139** | .086** | .357** | .256** | .094** | 0.05 | .101** | ||

| T1BDMonF | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.08** | −0.07* | 0.25** | 0.40** | 0.76** | 1.00 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −.150** | −.132** | .160** | .170** | .295** | .300** | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.04 | ||

| T1DDQ | 0.30** | 0.33** | 0.27** | 0.27** | −0.08** | −0.06* | 0.08** | 0.03 | 1.00 | .731** | .705** | .161** | .139** | −.067* | −0.04 | .065* | .077* | .583** | .359** | .492** | ||

| T1BAC | 0.29** | 0.30** | 0.28** | 0.29** | −0.09** | −0.09** | 0.06* | −0.01 | 0.73** | 1.00 | .649** | .192** | .177** | −.059* | −.072* | 0.02 | 0.03 | .442** | .368** | .450** | ||

| T1Cons | 0.26** | 0.30** | 0.25** | 0.25** | −0.05 | −0.07** | 0.08** | 0.04 | 0.71** | 0.65** | 1.00 | .113** | .111** | −0.05 | −0.05 | .065* | .082** | .385** | .300** | .548** | ||

| T2PermM1 | 0.35** | 0.30** | 0.35** | 0.31** | −0.07* | −0.07* | −0.11* | −0.15** | 0.16** | 0.19** | 0.11** | 1.00 | .836** | −.062* | −.069* | −.128** | −.111** | .176** | .216** | .132** | ||

| T2PermF1 | 0.28** | 0.33** | 0.28** | 0.34** | −0.08** | −0.08* | −0.07* | −0.12** | 0.13** | 0.17** | 0.11** | 0.84** | 1.00 | 0.00 | −.070* | −.084** | −.110** | .195** | .216** | .137** | ||

| T2PermM2 | 0.30** | 0.26** | 0.33** | 0.29** | −0.08** | −0.06 | −0.10** | −0.14** | 0.15** | 0.19** | 0.11** | 0.87** | 0.72** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| T2PermF2 | 0.25** | 0.30** | 0.28** | 0.33** | −0.08** | −0.06 | −0.09** | −0.14** | 0.14** | 0.17** | 0.11** | 0.74** | 0.87** | 0.83** | 1.00 | |||||||

| T2GMonM | −0.12** | −0.08** | −0.06* | −0.04 | 0.47** | 0.33** | 0.14** | 0.16** | −0.07* | −0.06* | −0.05 | −0.06* | 0.00 | −0.06* | 0.00 | 1.00 | .647** | .352** | .312** | −.102** | −.074* | −.109** |

| T2GMonF | −0.09** | −0.09** | −0.03 | −0.04 | 0.31** | 0.43** | 0.09** | 0.17** | −0.04 | −0.07* | −0.05 | −0.08* | −0.08* | −0.06 | −0.06* | 0.65** | 1.00 | .310** | .448** | −.062* | −.094** | −.114** |

| T2BDMonM | −0.06 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.19** | 0.15** | 0.36** | 0.30** | 0.07* | 0.02 | 0.07* | −0.12** | −0.06* | −0.13** | −0.10** | 0.35** | 0.31** | 1.00 | .778** | .077** | 0.03 | .063* |

| T2BDMonF | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.14** | 0.18** | 0.26** | 0.30** | 0.08* | 0.03 | 0.08** | −0.10** | −0.09** | −0.11** | −0.12** | 0.31** | 0.45** | 0.78** | 1.00 | .096** | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| T2DDQ | 0.20** | 0.24** | 0.18** | 0.21** | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.09** | 0.05 | 0.58** | 0.44** | 0.39** | 0.18** | 0.19** | 0.17** | 0.18** | −0.10** | −0.06* | 0.08** | 0.10** | 1.00 | .595** | .608** |

| T2BAC | 0.21** | 0.24** | 0.19** | 0.20** | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.36** | 0.37** | 0.30** | 0.21** | .21** | 0.21** | 0.21** | −0.07* | −.010** | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.60** | 1.00 | .474** |

| T2Cons | 0.20** | 0.22** | 0.18** | 0.21** | −0.05 | −0.07* | 0.10** | 0.04 | 0.49** | 0.45** | 0.55** | 0.13** | .13** | 0.13** | 0.14** | −0.11** | −0.11** | 0.06* | 0.05 | 0.61** | 0.47** | 1.00 |

Note:

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05.

T1=First year of college, T2=Fourth year of college, PermM1=mother permissiveness special occasions, PermF1=father permissiveness special occasions, PermM2=mother permissiveness sometimes, PermF2=father permissiveness sometimes, GMonM=mother general monitoring, GMonF=father general monitoring, BDMonM=mother binge monitoring, BDMonF=father binge monitoring, DDQ=typical weekly drinking, BAC=peak blood alcohol content, Cons=drinking consequences.

Table 2b.

Correlation between covariates and observed variables

| T1Sex | T1Peer | Campusd1 | Campusd2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1PermM 1 | −0.01 | 0.34** | 0.07** | −0.6* |

| T1PermF1 | −0.06* | 0.37** | 0.09** | −0.08** |

| T1PermM2 | 0.04 | 0.30** | 0.01 | −0.01 |

| T1PermF2 | −0.02 | 0.33** | 0.02 | −0.03 |

| T1GMonM | 0.16** | −0.05 | −0.12** | 0.23** |

| T1GMonF | 0.07* | −0.11** | −0.08** | 0.18** |

| T1BDMonM | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.07** |

| T1BDMonF | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.11** |

| T1DDQ | −0.13** | 0.51** | 0.21** | −0.16** |

| T1BAC | 0.01 | 0.50** | 0.14** | −0.19** |

| T1Cons | 0.00 | 0.46** | 0.08** | −0.12** |

| T2PermM1 | 0.03 | 0.18** | 0.16** | −0.13** |

| T2PermF1 | 0.01 | 0.19** | 0.15** | −0.17** |

| T2PermM2 | 0.04 | 0.17** | 0.14** | −0.14** |

| T2PermF2 | 0.02 | 0.18** | 0.13** | −0.16** |

| T2GMonM | 0.20** | −0.08** | −0.09** | 0.24** |

| T2GMonF | 0.10** | −0.08** | −0.04 | 0.19** |

| T2BDMonM | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.10** |

| T2BDMonF | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.08* |

| T2DDQ | −0.25** | 0.41** | 0.31** | −0.26** |

| T2BAC | 0.01 | 0.34** | 0.20** | −0.19** |

| T2Cons | −0.06* | 0.37** | 0.15** | −0.19** |

| T1Sex | 1.00 | −0.07** | −0.08** | 0.11** |

| T1Peer | 1.00 | 0.15** | −0.15** | |

| Campusd1 | 1.00 | −0.43** | ||

| Campusd2 | 1.00 |

Note:

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05.

T1=First year of college, T2=Fourth year of college, PermM1=mother permissiveness special occasions, PermF1=father permissiveness special occasions, PermM2=mother permissiveness sometimes, PermF2=father permissiveness sometimes, GMonM=mother general monitoring, GMonF=father general monitoring, BDMonM=mother binge monitoring, BDMonF=father binger monitoring, DDQ=typical weekly drinking, BAC=peak blood alcohol content, Cons=drinking consequences, Peer=peer norms, Campusd=campus dummy code.

Table 3.

Model Statistics.

| Paths | b-values | SE | z-score | Cohens d | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monitor (T1) | |||||

| Permissiveness (T1) | −0.02 | 0.01 | −1.52 | .00 | −0.04, 0.01 |

| Drink (T1) | |||||

| Permissiveness (T1) | 2.39 | 0.21 | 11.38 | .31 | 2.03, 2.86 |

| Monitor (T1) | 1.26 | 0.66 | 1.90 | .05 | 0.09, 2.66 |

| Consequences (T1) | |||||

| Drink (T1) | 1.94 | 0.09 | 21.70 | .57 | 1.77, 2.13 |

| Permissiveness (T2) | |||||

| Permissiveness (T1) | 0.29 | 0.03 | 9.67 | .33 | 0.24, 0.36 |

| Monitor (T1) | −0.39 | 0.11 | −3.56 | .09 | −0.64, −0.19 |

| Drink (T1) | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.91 | .53 | 0.01, 0.03 |

| Consequences (T1) | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | .00 | −0.01, 0.00 |

| Monitor (T2) | |||||

| Permissiveness(T1) | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.44 | .01 | −0.04, 0.02 |

| Monitor (T1) | 0.50 | 0.07 | 6.78 | .18 | 0.37, 0.66 |

| Drink (T1) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | .00 | −0.01, 0.01 |

| Consequences (T1) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | .00 | −0.00, 0.00 |

| Permissiveness (T2) | −0.04 | 0.02 | −1.92 | .00 | −0.09, 0.00 |

| Drink (T2) | |||||

| Permissiveness (T1) | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.24 | .00 | −0.43, 0.55 |

| Monitor (T1) | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.99 | .00 | −0.73, 2.53 |

| Drink (T1) | 0.98 | 0.10 | 9.76 | .26 | 0.80, 1.19 |

| Consequences (T1) | −0.12 | 0.03 | −3.71 | .11 | −0.18, −0.06 |

| Permissiveness (T2) | 0.81 | 0.30 | 2.72 | .07 | 0.23, 1.36 |

| Monitor (T2) | 0.70 | 0.60 | 1.16 | .03 | −0.46, 1.91 |

| Consequences (T2) | |||||

| Permissiveness (T1) | 0.12 | 0.56 | 0.21 | .01 | −1.00, 1.28 |

| Monitor (T1) | 0.62 | 1.49 | 0.42 | .00 | −2.13, 3.65 |

| Drink (T1) | −0.82 | 0.31 | −2.65 | .07 | −1.47, −0.24 |

| Consequences (T1) | 0.59 | 0.09 | 6.85 | .17 | 0.43, 0.76 |

| Drink (T2) | 1.83 | 0.19 | 9.72 | .26 | 1.49, 2.23 |

| Sex | 2.02 | 0.90 | 2.25 | .05 | 0.24, 3.77 |

| Peer Approval | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.92 | .02 | −0.38, 1.07 |

| Campusd1 | −2.37 | 1.11 | −2.14 | .05 | −4.43, −0.16 |

| Campusd2 | −3.40 | 1.07 | −3.18 | .07 | −5.40, −1.27 |

Note: Bolded b-values indicate significance. Campusd=campus dummy code.

Aim 1: Higher permissiveness of alcohol use would be associated with riskier drinking and more problems at both time points.

Examination of Figure 1 revealed that parental permissiveness was significantly and positively associated with drinking at T1 (b = 2.46) and again at T2 (b = .81). Students who endorsed more permissive parenting also reported higher rates of drinking at both time points. Parental permissiveness also was observed to have an indirect significant positive association on consequences at both T1 and T2 through its effect on drinking at T1 and T2, respectively (T1: product of α and β paths = 4.77; T2: product of α and β paths = 1.48). Thus, a 1 unit increase in parental permissiveness at T1 would result in students experiencing ~4–5 more consequences as a result of their increased drinking.

Aim 2: Permissiveness at T2 will mediate the effects of permissiveness at T1 and drinking at T2.

Parental permissiveness at T1 was observed to have a significant positive association with parental permissiveness at T2 (b = .30), which in turn was positively associated with drinking at T2 (.81). The mediated effect of parental permissiveness at T1 on drinking at T2 was significant (product of α and β paths = .24).

Aim 3: Permissiveness would be associated with less monitoring at both time points.

Parental permissiveness at T1 was not significantly associated with monitoring at T1 (ns), or T2 (ns).

Aim 4: Examine the hypothesized relationship between monitoring and drinking at both time points.

Parental monitoring at T1 was not significantly associated with drinking at T1 (ns) or T2 (ns).

Discussion

The current study examined the influence of parental permissiveness and monitoring on college student drinking outcomes during the first and fourth years of college. Consistent with Social Learning Theory (Bandura and Walters, 1963), our findings suggest parents continue to be a significant social influence on students’ decision making around alcohol consumption as they age into adulthood. As hypothesized, more permissive parenting was associated with increased rates of drinking and consequences during both the first and fourth years of college. For example, based on our findings a small difference in parental permissiveness at T1 (i.e., a 1 unit increase) would be predicted to result in students experiencing ~4–5 additional consequences in their first year of college. Further, permissiveness at T2 mediated the relationship between T1 permissiveness and student drinking at T2. These findings have several important implications. First, this parenting behavior is fairly consistent across time. Second, intervening with more permissive parents as students enter college may have a lasting impact on later parenting behaviors that continue to influence drinking behaviors and alcohol problems even after students turn 21 and transition into adulthood.

Findings from the study show evidence that students whose parents are more permissive may be less likely to mature out of higher risk drinking by the time they reach their fourth year in college. These findings are consistent with Jackson and colleagues (2001) who observed higher risk drinkers and individuals having a family history of alcohol problems were less likely to show maturing out over college and into adulthood. Additional studies that examine associations between permissive parenting practices and dependence outcomes in older emerging adult students would be useful to identify early and malleable predictors of chronic outcomes.

The study also examined the relationship between permissiveness, monitoring, and drinking; however, we did not find support for our proposed hypotheses. We found no significant relationships between permissiveness and monitoring at T1 or T2. Further, relationships between monitoring and drinking were not significant at either time. One explanation for this finding is that permissiveness accounted for the majority of the variance. It may be that the messages parents send about their approval of drinking have a much greater impact compared to checking in about their student’s activities or other social behaviors. For example, parents who are permissive may check in with their students about school, living arrangements, food, money, etc., but not convey values that they should not consume alcohol. Alternatively, they make social plans with their students that include alcohol consumption (e.g., visiting and attending a tailgate or party where alcohol is consumed). This explanation is consistent with other longitudinal studies that have observed significant relationships for parental permissiveness and drinking and nonsignificant findings for other parental variables and drinking, when they are both examined together (Van der Vorst et al., 2006a; Varvil-Weld et al., 2012).

The findings suggest parents who convey low acceptability of risky student drinking may be more successful at reducing drinking among their sons and daughters across college. This is a particularly relevant finding considering we observed increases in permissiveness between T1 and T2 while student drinking and consequences were higher at T2 compared to T1. The latter observations are consistent with Hingson and colleagues (2009) who have also shown increased risky drinking in the early twenties.

By reinforcing healthy behaviors before and after 21, parents demonstrated a protective influence on their students’ drinking behaviors and consequences. These findings were consistent for both males and females when T1 covariate constructs were included in the models. These findings extend the cross-sectional examination of the effects of parenting on student drinking outcomes of Patock-Peckham and colleagues (2011). Consistent with their study, the current research argues for parents to convey less permissive messages about drinking coupled with increased monitoring to reduce risky drinking and consequences for both sons and daughters throughout college and after turning 21.

Implications

Several key findings are worth noting in the current study. First, the findings support the assertion that parents may be most impactful on student drinking outcomes by taking a less permissive stance toward underage drinking in college. Based on the parenting approaches described by Baumrind (1978), there are different ways parents can convey this message which should be carefully considered. First, some parents may take an authoritarian approach by simply telling their young adult they disapprove of underage drinking and direct their son or daughter to avoid it. However, such an approach may not be ideal, given that past research has shown a positive relationship between authoritarian parenting and higher risk drinking behaviors and problems (Mallett et al., 2011) as well as impulsive behaviors (Patock-Peckham and Morgan-Lopez, 2006). Alternatively, parents may have more success by adopting an authoritative approach. This would consist of engaging in a discussion about the risks of underage drinking and the scientific rationale behind parents not encouraging this behavior. Guiding young adults in the decision-making process and using positive communication practices, rather than forcefully directing, has been associated with lower risk behaviors and drinking outcomes (Madkour et al., 2017; Patock-Peckham and Morgan-Lopez, 2006). While monitoring is an important element of the parent-student relationship, permissiveness of alcohol use stood out as a pivotal indicator of problems. In light of these findings, parent-based interventions (PBIs) could be enhanced by focusing on intervening with parents to decrease overall permissiveness of alcohol use and increase positive communication about this important topic with their students.

Notably, we observed higher rates of drinking and reported consequences at T2, suggesting that, on average, students’ drinking patterns and reported consequences were higher in the fourth year of college compared to the first year of college. Further, we also observed decreased monitoring and increased permissiveness. These findings demonstrate a need for continued intervention efforts throughout college or as students are graduating. Parents may still be impactful by helping students set reasonable limits on alcohol consumption and provide guidance for healthy and moderate drinking.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study was not without limitations. First, family structure was not assessed which may not have captured single parent families or split families. However, FIML was used to address missing data and therefore allowed us to use all students regardless of if they had both a mother and father figure or only one parental figure. Future research that aims to replicate these findings in single-parent homes and identify if any differences arise for students with divorced parents compared to married parents would be beneficial. Further, students were only eligible for the entirety of the study if they had at least one parent also consent and complete the baseline assessment. Therefore, the students in the study may have parents with high levels of parent-child engagement, and may not generalize to all parents of college students, or to parents who have children that are college-aged (i.e., 18–22), but are not currently enrolled at a 2- or 4-year institution. Research should aim to replicate these findings in college students with varying levels of parent engagement, differing parental demographics, and in non-college attending populations. It is also important to note, there are additional measures of parental permissiveness that offer a broader assessment of the construct and are appropriate for adolescent populations (Van der Vorst et al., 2005). In particular, Van der Vorst’s measure may offer particular perspectives on parent permissiveness that were not assessed in the method of measurement used in the present study (e.g., parents allowing their children to come home tipsy or when going out with friends). Future studies that examine permissiveness could benefit from examining multiple dimensions and developmental differences (e.g., use in adolescents living with parents vs. use in young adult populations living away from parents) and would be a useful addition to the literature. Third, the research was conducted at three campuses to increase the heterogeneity of the sample, and although we did not observe evidence suggestive of clustering effects due to campus, future studies should continue to evaluate this in their analyses to account for this possibility. Finally, we contrasted the first and fourth years of college in our study. This approach does not take into account associations that could vary in years two and three of college. Future studies may benefit from a more discrete examination of the effects of parental permissiveness on student drinking that includes shorter intervals of assessment.

Conclusion

Results indicated that parental permissiveness of alcohol use is a significant indicator of risky drinking and related problems across the college years. Findings suggest that parent-based interventions could be strengthened by enhancing components about the important role of parental permissiveness of alcohol use and monitoring in relation to student drinking outcomes and emphasizing continued conversations throughout college.

Acknowledgments:

This research was supported by NIAAA R01AA012529 awarded to Rob Turrisi. The authors would like to thank Sarah Ackerman, M.S. and the anonymous peer reviewers for their valuable feedback on the manuscript.

Footnotes

To assess whether campus differences created clustering that would inflate model effects, we compared the R2 values when predicting consequences at T2 without the campus dummy codes in the model (R2 = .56) versus with the campus dummy codes in the model (R2 = .57). The R2diff between the two models (R2diff. = .01) is highly suggestive that there are no substantial effects of clustering that would inflate the significant effects observed in our model.

References

- Abar CC, Morgan NR, Small ML, Maggs JL (2012) Investigating associations between perceived parental alcohol-related messages and college student drinking. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 73:71–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abar C, Turrisi R (2008) How important are parents during the college years? A longitudinal perspective of indirect influences parents yield on their college teens’ alcohol use. Addict Behav 33:1360–1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, Walters RH (1963) Social learning and personality development. Holt Rinehart and Winston, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D (1978) Parental disciplinary patterns and social competence in children. Youth Soc 9:239–276. [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB (2003) Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. J Stud Alcohol 64:331–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Murphy JG, Barnett NP (2007) Predictors of alcohol use during the first year of college: Implications for prevention. Addict Behav 32:2062–2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, McGue M, Maggs J, Schulenberg J, Hingson R, Swartzwelder S, Martin C, Chung T, Tapert SF, Sher K, Winters KC, Lowman C, Murphy S (2008) A developmental perspective on alcohol and youths 16 to 20 years of age. Pediatrics 4:S290–S310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun BH, Maggs JL, Loken E (2018) Change in college students’ perceived parental permissibility of alcohol use and its relation to college drinking. Addict Behav 76:275–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Handley ED (2006) Parents and families as contexts for the development of substance use and substance use disorders. Psychol Addict Behav 20:135–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA (1985) Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. J Consult Clin Psychol 53:189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA (1999) Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS). Guildford, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K (2006) Parenting and other influences on the alcohol use and emotional adjustment of children, adolescents, and emerging adults. Psychol Addict Behav 20:138–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER (2009) Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl 16:12–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut SC, Sher KJ (1992) Assessing alcohol problems in college students. J Am Coll Health 41:49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Gotham HJ, Wood PK (2001) Transitioning into and out of large-effect drinking in young adulthood. J Abnorm Psychol 110:378–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koning IM, Engels RCME, Verdurmen JEE, Vollebergh WAM (2010) Alcohol-specific socialization practices and alcohol use in Dutch early adolescents. J Adolesc 33:93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koning IM, van den Eijnden RJJM, Verdurmen JEE, Engels RCME, Vollebergh WAM (2012) Developmental alcohol-specific parenting profiles in adolescence and their relationship with adolescents’ alcohol use. J Youth Adolesc 41:1502–1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Lydum AR, Anderson BK, Turner AP (1999) Male and female recipients of unwanted sexual contact in a college student sample: Prevalence rates, alcohol use, and depression symptoms. Sex Roles 40:295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Mallett KA, Geisner IM (2004) Predicting drinking behavior and alcohol-related problems among fraternity and sorority members: Examining the role of descriptive and injunctive norms. Psychol Addict Behav 18:203–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Chassin L, Villalta I (2013) Maturing out of alcohol involvement: Transitions in latent drinking statuses from late adolescence to adulthood. Dev Psychopathol 25:1137–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C (2006) Social norms approaches using descriptive drinking norms education: A review of the research on personalized normative feedback. J Am Coll Health 54:213–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V (2002) A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods 7:83–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madkour AS, Clum G, Miles TT, Wang H, Jackson K, Shankar A (2017) Parental influences on heavy episodic drinking development in the transition to early adulthood. J Adolesc Health 61:147–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallett KA, Turrisi R, Ray AE, Stapleton J, Abar C, Mastroleo N, Tollison S, Grossbard J, Larimer ME (2011) Do parents know best? Examining the relationship between parenting profiles, prevention efforts, and peak drinking in college students. J Appl Soc Psychol 41:2904–2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Dimeff LA, Larimer ME, Quigley LA, Somers JM, Williams E (1998) Screening and brief intervention for high-risk college student drinkers: Results from a 2-year follow-up assessment. J Consult Clin Psychol 66:604–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DB, Miller WR (1979) Estimating blood alcohol concentration: Two computer programs and their applications in therapy and research. Addict Behav 4:55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO (2017) Mplus User’s Guide. 1998–2017. Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, Cheong J, Balhorn ME, Nagoshi CT (2001) A social learning perspective: A model of parenting styles, self-regulation, perceived drinking control, and alcohol use and problems. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 25:1284–1292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, King KM, Morgan-Lopez AA, Ulloa EC, Moses JM (2011) Gender-specific mediational links between parenting styles, parental monitoring, impulsiveness, drinking control, and alcohol-related problems. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 72:247–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, Morgan-Lopez AA (2006) College drinking behaviors: Mediational links between parenting styles, impulse control, and alcohol-related outcomes. Psychol Addict Behav 20:117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Colder CR (2006) Development and preliminary validation of the young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire. J Stud Alcohol 67:169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reifman A, Barnes G, Dintcheff BA, Farrell MP, Uhteg L (1998) Parental and peer influences on the onset of drinking among adolescents. J Stud Alcohol 59:311–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rulison KL, Wahesh E, Wyrick DL, DeJong W (2016) Parental influence on drinking behaviors at the transition to college: The mediating role of perceived friends’ approval of high-risk drinking. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 77:638–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Maggs JL (2002) A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. J Stud Alcohol Suppl 14:54–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS (2013) Using Multivariate Statistics 6. Allyn and Bacon, Boston. [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Ray AE (2010) Sustained parenting and college drinking in first-year students. Dev Psychobiol 52:286–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Mallett KA, Cleveland MJ, Varvil-Weld L, Abar C, Scaglione N & Hultgren B (2013). Evaluation of timing and dosage of a parent based intervention to minimize college students’ alcohol consumption. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 74(1), 30–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Vorst H, Engels RCME, Meeus W, Dekovic M (2006a) Parental attachment, parental control, and early development of alcohol use: A longitudinal study. Psychol Addict Behav 20: 107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Vorst H, Engels RCME, Meeus W, Dekovic M, Van Leeuwe J (2005) The role of alcohol-specific socialization in adolescents’ drinking behavior. Addiction 100:1464–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Vorst H, Engels RCME, Meeus W, Dekovic M, Vermulst A (2006b) Family factors and adolescents’ alcohol use: A reply to Chassin and Handley (2006) and Fromme (2006). Psychol Addict Behav 20:140–142. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Vorst H, Vermulst AA, Meeus WHJ, Dekovic M, Engels RCME (2009) Identification and prediction of drinking trajectories in early and mid-adolescence. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 38:329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varvil-Weld L, Crowley DM, Turrisi R, Greenberg MT, Mallett KA (2013) Hurting, helping, or neutral? The effects of parental permissiveness toward adolescent drinking on college student alcohol use and problems. Prev Sci 15:716–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varvil-Weld L, Mallett KA, Turrisi R, Abar CC (2012) Using parental profiles to predict membership in a subset of college students experiencing excessive alcohol consequences: Findings from a longitudinal study. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 73:434–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walls TA, Fairlie AM, Wood MD (2009) Parents do matter: A longitudinal two-part mixed model of early college alcohol participation and intensity. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 70:908–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Johnson V, Buyske S (2000) Parental modeling and parenting behavior effects on offspring alcohol and cigarette use: A growth curve analysis. J Subst Abuse 12:287–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MD, Read JP, Mitchell RE, Brand NH (2004) Do parents still matter? Parent and peer influences on alcohol involvement among recent high school graduates. Psychol Addict Behav 18:19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]