Abstract

Television advertising has been a primary method for marketing new health plans available under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to consumers. Kantar Media/CMAG data were used to analyze advertising content during three ACA open enrollment periods (2013-2016). Few advertisement airings featured people who were elderly, disabled, or receiving care in a medical setting, and airings increasingly featured children, young adults and people exercising overtime. The most common informational messages focused on plan choice and availability of low-cost plans, but messages shifted over open enrollment cycles to emphasize avoidance of tax penalties and availability of financial assistance. Over the three open enrollment periods, there was a sharp decline in explicit mentions of the ACA or Obamacare in advertisements. Overall, television advertisements have increasingly targeted young, healthy consumers and informational appeals have shifted toward a focus on financial factors in persuading individuals to enroll in Marketplace plans. These advertising approaches make sense in the context of pressures to market plans to appeal to a sufficiently large, diverse group. Importantly, dramatic declines over time in explicit mention of the law mean that citizens may fail to understand the connection between the actions of government and the benefits they are receiving.

Keywords: media, health insurance, local news, advertising, public opinion, politics

INTRODUCTION

In the Fall of 2013, the first ACA open enrollment period was launched to enroll Americans in health insurance through new insurance options in the new individual (or subsequently small-group) Marketplaces or through optional state Medicaid expansion for low-income Americans. By early 2017, there had been four open enrollment cycles resulting in over 20 million individuals gaining insurance through either the Marketplaces or state Medicaid expansions in 32 states and the District of Columbia. Enrollment of this magnitude required a large investment in informational and marketing campaigns. Many entities sponsored advertising for new health insurance products available under the ACA, including private insurance companies and brokers, state-sponsored Marketplaces, a federally-facilitated Marketplace through healthcare.gov, and other outreach efforts by consumer health insurance enrollment advocates such as Enroll America. Television product advertising has been a primary method for marketing new insurance options available under the ACA to consumers.a

Marketplace advertising has been swept up in broader partisan conflicts over the future of the ACA. In September 2017, the Trump Administration announced its intention to cut advertising for television commercials for the healthcare.gov ACA enrollment site entirely, and reduce the federal ACA enrollment marketing budget by 90 percent – from $100 million spent on the 2017 open enrollment period to only $10 million for the 2018 open enrollment cycle beginning November 2017. Importantly, this reduction does not affect other types of ACA-related health insurance product marketing dollars (i.e., advertisements sponsored by state Marketplaces, private insurers).

Prior research supports the notion that news media content of the ACA including television advertising powerfully influences both consumer insurance purchasing behaviors and the opinions of the broader public. Studies have documented substantial geographic variation in the volume and tone of insurance product advertisements during ACA open enrollment periods (Gollust et al. 2014), and this variation in exposure to media messages about the law was associated with public perceptions of the ACA, changes in insurance rates, and individuals’ information-seeking and uptake of marketplace plans in 2014 (Fowler et al 2017; Karaca-Mandic et al. 2017; Gollust et al. 2018). Fowler and colleagues found that a higher volume of insurance advertising, as well as local news coverage, were associated with beliefs among survey respondents that they were well-informed about the law (2017). Karaca-Mandic and colleagues found that the volume of television advertising during the first open enrollment period was associated with greater insurance coverage (2017). Specifically, counties with higher volumes of local insurance advertisements experienced larger reductions in their uninsured rates than other counties. State-sponsored advertisements had the strongest relationship with uninsurance declines, and this was driven by greater Medicaid enrollment among the previously uninsured. In addition, geographic variation in the counts of insurance ads aired – particularly federally-sponsored ads—was associated with individuals’ odds of shopping for and obtaining a marketplace plan in 2014 (Gollust et al. 2018).

The connection between health insurance advertising content and public opinion about health policy is not unique to political discourse over the ACA. Interest groups have been attempting to influence public attitudes about national health reform in the U.S. as long as these debates have been occurring. In his history of the public relations industry in America, for example, Scott Cutlip describes advertising efforts launched by the American Medical Association in the late 1940s to oppose President Truman’s national health insurance plan including the wide distribution of an advertisement featuring Luke Fildes’ famous 1887 painting (hanging in the Tate Britain in London) of a doctor at a child’s bedside at home. The accompanying captions read: “The Voluntary Way is the American Way” and “Keep Politics Out of this Picture.” (1994) More recently, Darrell West and colleagues used public opinion surveys to investigate public response to political advertisements to oppose President Clinton’s health care reform plan in 1993-94 (1996). The authors found that advertisements including the well-known ‘Harry and Louise’ ads directed against the Clinton reform plan played a critical role in the attachment of negative views by the public of some to the key elements of the proposed reform.

In contemporary policy discourse over the ACA, however, the content of television insurance product advertising has not been examined in depth, and little is known about how advertising content has evolved over subsequent open enrollment periods as marketers learned from their experiences with the new Marketplaces. Understanding how health insurance options have been depicted in advertising is consequential because the audience for the messages about the new products available as a result of the law include both uninsured individuals seeking to purchase coverage and a much larger group of insured Americans whose impressions of the law have been shaped, at least in part, through media exposure including insurance product advertising (Soroka, Maioni, and Martin 2013). In part, this relates to the question of whether and to what extent individuals formulate opinions and make decisions in a health care setting on the basis of personal experience versus pre-formed opinions due to ideology or other informational sources. Prior work by Blidook suggest opinions on health care derive from multiple sources (Blidook 2008). Importantly, the literature suggests that the more directly a person experiences an issue, the less open he or she is open to external influences (e.g., via the media) on that issue (Mutz 1992; Ball-Rokeach and DeFleur 1976; Blidook 2008). Thus, the content of advertising matters not only for policy (i.e., the composition of the individual Marketplace and the types of appeals used by advertisement sponsors) but also for politics, particularly what information about the ACA the general public observing these marketing efforts might draw in forming their attitudes about the law, efforts to replace or modify it, and future health reform efforts.

In this study, we collected and analyzed the content of a random sample of television insurance product advertisements that aired in one or more US media markets during the initial three ACA open enrollments spanning three distinct time periods from Fall 2013 to Spring 2016. There are a number of important questions about the content of information communicated to the uninsured and the general public through ACA advertising. First, we examined which groups (e.g., private companies, state and federal government agencies, consumer advocates) sponsored the health insurance advertisements that aired during these three initial open enrollment periods. Second, we assessed the extent to which advertising targeted so-called “young invincibles” in marketing new insurance products. This label has been given to adults under age 35 who often opt against purchasing health insurance due to the belief that they will not need it and might better direct their purchasing power toward other priorities (Levine and Mulligan 2017). It has been challenging to persuade young, healthy uninsured individuals to avail themselves of insurance. However, it is critical to the stability of the individual health insurance market to enroll enough healthy consumers to counterbalance the sicker, costlier uninsured individuals who are more likely to directly benefit from enrolling. Therefore, we expected that ACA health plan advertising would target young and healthy adults disproportionately to their numbers among the uninsured, and more aggressively than other uninsured populations who might benefit from new insurance options (e.g., newly eligible middle age adults). We also hypothesized that efforts to target young invincibles might be augmented over time as concerns about risk selection in the Marketplaces were highlighted in news media reports (Leonard 2016).

Third, we assessed which types of informational messages advertisers relied on to persuade uninsured individuals to enroll, and whether these informational messages shifted over subsequent open enrollment periods. In short (15 to 120 second) insurance advertisements, it is not possible to convey all of the elements critical to choosing among competing health insurance products. Therefore, marketers must weigh tradeoffs in communicating different types of information (Story and French 2004). For example, if an advertisement sponsor was most concerned about consumers’ resistance to purchase insurance due to costs, advertisements might focus on the availability of low cost plans, the large subsidies being offered through the Marketplaces, or access to free/low cost preventive services. Alternatively, if an advertisement sponsor thought consumers might be resistant to purchasing insurance due to fears about a complicated enrollment process, advertisements might feature messages about the availability of enrollment assistance or the simplicity of the enrollment process. We hypothesized that the informational messages conveyed through advertisement airings may shift over time as plan options were constrained and premiums rose following the exodus of a subset of health plans from Marketplaces. Additionally, we expected that sponsors would use different types of informational messages to persuade uninsured Latinos to enroll (e.g., simplicity of enrollment) via Spanish language advertisements relative to advertisements airing in English.

Finally, given the ideologically-charged debate over the ACA, it is important to understand whether advertisements mention the government’s role in establishing and subsidizing the new health insurance options being offered through the ACA. The question of whether or not advertisements explicitly reference the health law is relevant in the context of Suzanne Mettler’s theory of the submerged state (Mettler 2011). Mettler argues that public support for governmental programs will be lower when citizens fail to understand the connection between the state and the benefits they receive. If consumers do not understand that health plans they could benefit from are part of the ACA, this theory would suggest that these consumers would be less likely to support the law (or more likely to support repeal efforts). We hypothesize that advertisements sponsored by insurance companies would be more likely to submerge the government’s role relative to other sponsors (e.g., state and federal Marketplaces).

DATA AND METHODS

DATA SOURCE

We obtained Kantar Media/CMAG television health insurance product advertising data airing during the first three ACA open enrollment periods in all 210 US local media markets from the Wesleyan Media Project. A media market or designated market area (DMA) is defined as a geographic area that has access to similar radio and television stations and is updated annually by the Nielson Company. (“DMA Regions” 2013) The three open enrollment periods were: (1) October 2013 through March 2014; (2) November 2014 through February 2015, and (3) November 2015 through February 2016. These advertising data included video files for 3747 unique advertisements that aired on local television or national cable in each media market. Data also included information on the volume of airings of each advertisement overall and within media market by open enrollment period.

We excluded unique advertisements that aired exclusively on national network or cable advertising because we wanted to ensure geographic representation of messages airing at the local level throughout the country (ads that aired on both local broadcast and national remained in the sample). The vast majority of advertising that aired on national network or cable outlets also ran on local broadcast (73 percent of unique advertisements and 89 percent of airings were still eligible for sampling). Only two of the 21 federal advertisements (10 percent of advertisements and 23 percent of airings) were excluded in this subset. In addition, we excluded televisions advertisements that were exclusively about Medicaid. In practice, there were almost no advertisements excluded due to a Medicaid product focus. We did include advertisements, such as those from the state-based exchanges, mentioning multiple types of insurance (e.g., Medicaid and private insurance).

Next, we randomly sampled 1054 unique advertisements from the entire pooled set of unique advertisements to code. We excluded Medicare Advantage and Medicaid, CHIP advertisements (N=163) and advertisements sponsored by specific hospitals (N=4) to focus on marketing of insurance products newly available through the ACA. We also excluded 12 unique advertisements with corrupted files (i.e., problems with sounds or visuals that prevented coding). The final sample included 875 unique advertisements. Fifteen percent of the unique advertisements were Spanish language (N=131). There were 1,074,653 airings of these unique advertisements with 490,659 airings in open enrollment 1; 337,068 airings in open enrollment 2, and 246,926 airings in open enrollment 3. The decline in sampled airings across the enrollment periods mirrored the decline overtime within the full census of airings. Ten percent of all airings were of Spanish language advertisements (N=110,134).

Coding Approach and Measures

The study team developed and pilot tested an 8-minute, 28-item coding instrument to collect data on the audio and visual content of each advertisement (see appendix A). Both English and Spanish advertisements were coded by three trained coder authors (SB, KA, JP), with a random subset of 12% of English advertisements (N=107) independently coded by 2 coders to assess item inter-rater reliability. We measured inter-rater reliability by use of Kappa statistics, a measure that enabled us to adjust for agreement by chance. Item raw agreement ranged from 88% to 100% (k 0.70–1.00) for all variables included in this study (see appendix B), which exceeded conventional standards for acceptable reliability (Landis and Koch 1977).

We collected and coded content at the unique advertisement level and, within advertisement, at the focal person level. We defined a focal person as a non-cartoon individual of any age whose face was visible and appeared for at least 3 seconds in the advertisement.

At the advertisement level, we categorized each sponsor as a health insurance company (including broker-sponsored advertisements), a state Marketplace (individual or SHOP), the federal Marketplace, or enrollment advocates (i.e., Enroll America). Additionally, we coded for six specific types of messages advertisers included to encourage enrollment: availability of a choice of plans; availability of low cost plans; provision of financial assistance with premiums; enrollment assistance provided; simplicity of the enrollment process; access to high quality medical care, and enrolling to avoid tax penalties. We also coded whether each unique advertisement included any explicit mention of the ACA, Obamacare, health/health care reform, the health insurance Marketplace, or the healthcare.gov website.

We then coded information at the focal person level within each advertisement. We coded information for up to 5 focal people per advertisement. We coded the following information for each focal person: female or male, race, age (i.e., child, young adult, middle age, elderly person), disabled, engaging in exercise, receiving care in medical setting, overweight or obese, or smoking tobacco. We operationalized the concept of “young invincible” by examining the extent to which airings focused on young adults based on the notion that viewers observing an individual in their own age group in an advertisement might be more likely to think about health insurance as something they should consider themselves. We were also interested in understanding the extent to which people in advertisements were featured engaging in ‘healthy’ activities (e.g., exercise) versus ‘unhealthy’ activities (e.g., smoking). Only a subset of unique advertisements (N=587) contained focal people (totaling N=1,670 focal people), and these advertisements included an average of 2.84 focal people. At the airings level, a total of 2,056,011 focal people appeared in airings since only a subset of airings (N=767,871) contained focal people.

Data Analysis

While we coded these data at the unique advertisement and focal person levels, we conducted data analysis at the airings level. Analysis of data at the airings level provides the more accurate picture of the volume and geographic reach of informational content communicated to the uninsured and the general public via television advertising.

We compared whether the content of advertisement airings differed significantly by advertisement sponsor (e.g., insurance companies, state Marketplaces, federally-facilitated Marketplace, or enrollment advocates), across enrollment periods, or by advertisement language (Spanish versus English) using chi-squared tests. We examined geographic variation at the media market level of mentions of the ACA or Obamacare in advertisement airings by enrollment periods using GIS mapping. Finally, we used logistic regression to examine the variables associated with the probability that an airing included a young adult as a focal person and the probability that an airing explicitly mentioned the ACA or Obamacare, controlling for other advertisement airing-level characteristics. These included the open enrollment period in which an airing appeared, the airing sponsor (i.e., sponsored by insurer, state marketplace, federally-facilitated marketplace, or enrollment advocate), the uninsured rate in the media market an airing appeared, the proportion of the media market’s population voting for former President Barack Obama in the 2012 election, the type of Marketplace offered in the state in which the airing appeared (federally-facilitated Marketplace or other), and the language of the airing.

RESULTS

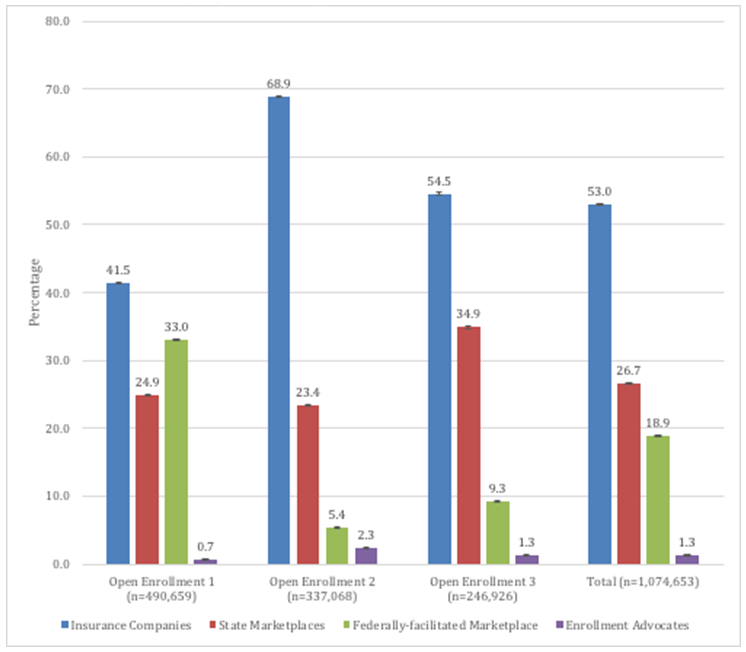

Figure 1 shows the share of total health insurance advertisement airings sponsored by insurance companies, state Marketplaces, the federal-facilitated Marketplace and enrollment advocates. Overall, 53.0% of advertisement airings were sponsored by insurance companies; these airings constituted 41.5% of airings in open enrollment 1, 68.9% of airings in open enrollment 2 and 54.5% of airings in open enrollment 3. The second most prevalent source of advertisement airings was state Marketplace sponsors, responsible for 26.7 percent of total airings. Advertisements sponsored by the federally-facilitated Marketplace (18.9% of airings) and enrollment advocates (1.3% of airings) constituted a relatively small source of total airings. Compared with open enrollment 1, the share of federally-sponsored advertisement airings decreases sharply, while the share of airings sponsored by insurance companies increased. In all three periods, advertisements sponsored by enrollment advocates constituted a tiny share of total airings.

Figure 1. Television Health Insurance Advertisement Airings by Advertisement Sponsor, Overall and by Open Enrollment Period (N=1,074,653 Airings).

Note: Insurance companies category includes private brokers.

Table 1 summarizes information on the individuals depicted in advertisement airings. Overall, very few airings included elderly people, people receiving care in a medical setting, disabled people or overweight or obese people, and none were smokers. Compared with period 1, focal people depicted in open enrollment period 3 were less likely to be middle aged, or receiving medical care, and more likely to be children and young adults, engaged in exercise and overweight or obese. Compared with English language airings, Spanish language airings were more likely to include non-white people, females, children and young adults, people exercising and people receiving medical care.

Table 1.

Focal People Depicted in Television Health Insurance Advertisement Airings, 2013-2016

| Total | Open Enrollment Period 1 |

Open Enrollment Period 2 |

Open Enrollment Period 3 |

English Language |

Spanish Language |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (%) | 45.4 | 47.0 | 44.2* | 43.9* | 44.4 | 51.8* |

| Non-white(%) | 50.8 | 54.6 | 49.5* | 45.6* | 44.2 | 96.9* |

| Disabled person (%) | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0* | 0.0* | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Child(%) | 22.3 | 20.9 | 19.0* | 29.4* | 21.9 | 24.7* |

| Young adult(%) | 16.5 | 11.6 | 21.2* | 19.0* | 14.7 | 29.4* |

| Middle age person(%) | 59.3 | 66.4 | 58.0* | 48.2* | 61.9* | 41.8* |

| Elderly person(%) | 1.9 | 1.1 | 1.9* | 3.4* | 1.6 | 4.1* |

| Person engaged in Exercise(%) | 16.3 | 11.1 | 18.5* | 22.9* | 16.0 | 18.5* |

| Person receiving care in medical setting(%) | 7.8 | 13.6 | 3.6* | 3.0* | 7.5 | 9.8* |

| Overweight or obese person(%) | 2.4 | 0.9 | 3.6* | 3.3* | 2.4 | 2.0* |

| Person smoking tobacco (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Focal people N(%) | 2,056,011 (100%) |

895,869 (43.6%) |

668,744 (32.53%) |

491,398 (23.9%) |

1,799,514 (87.5) |

256,497 (12.5) |

Note:

Refers to difference from Open Enrollment 1 (versus 2 and 3) and differences from English language (versus Spanish language) at 0.05 significance level

Regression results in the first column of Table 2 confirm that, controlling for other airings-level characteristics, advertisements aired in enrollment periods 2 and 3 were significantly more likely to include a young adult as a focal person relative to period 1. Compared with those sponsored by state Marketplaces, advertisements sponsored by insurance companies and enrollment advocates were significantly less likely to feature a young adult focal person, and advertisements sponsored by the federal Marketplaces were more likely to feature a young adult in airings. Relative to other airings, those in English (relative to Spanish) and those that aired in media markets with higher uninsurance rates were less likely to feature a young adult and media markets voting in higher proportions for President Obama in the 2012 election were more likely to feature a young adult.

Table 2.

Multivariable Regression Results on Probability of Explicit Mention of the ACA or Obamacare in Television Health Insurance Advertisement Airings, 2013-2016

| Young Adult Focal Person (n=2,056,011) |

Mentions the Affordable Care Act or ObamaCare (n=1,074,653) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Open Enrollment Period (REF: Open Enrollment Period 1) |

||

| Open Enrollment Period 2 | 2.81* [2.78, 2.83] |

0.10* [0.09, 0.10] |

| Open Enrollment Period 3 | 2.15* [2.13, 2.17] |

0.11* [0.11, 0.11] |

| Advertisement Sponsor (REF: State marketplace) |

||

| Insurance Companies | 0.40* [0.40, 0.40] |

14.91* [14.62, 15.21] |

| Federally-facilitated Marketplace | 1.63* [1.61, 1.65] |

10.35* [10.12, 10.57] |

| Enrollment Advocates | 0.68* [0.63, 0.72] |

23.71* [22.69, 24.78] |

| Media Market Level % Uninsured | 0.44* [0.41, 0.47] |

2.88* [2.63, 3.14] |

| Media Market Level % Obama Vote, 2012 | 2.55* [2.45, 2.65] |

0.83 [0.79, 0.88] |

| Federally Facilitated Exchange in State, 2014 | 1.38* [1.37, 1.40] |

1.02* [1.00, 1.03] |

| English Language Advertisement | 0.51* [0.50, 0.52] |

1.23* [1.20, 1.25] |

Notes: Mentions ACA or Obamacare includes: Obamacare or Affordable Care Act or ACA or Health care law or the president's (or Obama's) health care law or Health reform or health care reform. Insurance companies category includes private brokers. Data on type of exchange identified from Kaiser Family Foundation.

refers to difference from 1.00 at 0.05 significance level

Table 3 shows the proportion of airings including specific informational content aimed at persuading individuals to enroll in new insurance products. Overall, across all 3 open enrollment periods, most common types of information mentioned were choice of health plans (61.2%) and the availability of low cost plans (55.4%). Other informational messages sponsors commonly mentioned in airings were the availability of financial assistance (49.1%) and the availability of enrollment assistance (40.8%). Only a quarter of airings included messages encouraging enrollment by noting the availability of low cost or free preventive services (28.3%), and even fewer mentioned the simplicity of the enrollment process (22.2%), the ability to access high quality medical care (17.8%) or being able to avoid tax penalties by enrolling (10.7%).

Table 3.

Information Included in Television Health Insurance Advertisement Airings, 2013-2016 (N=1,074,653)

| Total | Open Enrollment Period 1 (%) |

Open Enrollment Period 2 (%) |

Open Enrollment Period 3 (%) |

Insurance Companies (%) |

State Market- places (%) |

Federally- facilitated Market- place (%) |

Enrollment Advocates (%) |

English Language (%) |

Spanish Language (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choice of plans available | 61.2 | 70.6 | 62.2* | 41.4* | 64.2 | 38.1* | 84.2* | 81.6* | 61.9 | 55.7* |

| Low cost plans available | 55.4 | 64.6 | 48.8* | 46.3* | 43.9 | 47.9* | 97.3* | 71.5* | 55.4 | 56.2* |

| Financial assistance available | 49.1 | 41.4 | 56.6* | 54.3* | 50.5 | 55.7* | 35.0* | 65.0* | 47.8 | 60.8* |

| Assistance with enrollment available | 40.8 | 39.9 | 46.2* | 35.0* | 54.5 | 37.7* | 7.1* | 35.0* | 39.8 | 49.5* |

| Free/low cost preventive services available | 28.3 | 32.3 | 25.0* | 24.6* | 36.8 | 6.9* | 36.0* | 6.0* | 30.2 | 11.4* |

| Simplicity of enrollment | 22.2 | 18.1 | 29.1* | 20.7* | 25.3 | 14.1* | 26.3* | 1.5* | 23.1 | 14.4* |

| Access to high quality medical care | 17.8 | 19.2 | 16.0* | 17.4* | 29.8 | 7.5* | 0.0* | 0.0* | 19.6 | 2.2* |

| Avoiding penalties | 10.7 | 1.5 | 20.1* | 16.3* | 17.7 | 3.4* | 1.8* | 7.6* | 10.6 | 11.8* |

| Health law mentioned: | ||||||||||

| Any mention of health law | 48.7 | 69.8 | 31.1* | 30.9* | 38.8 | 32.8* | 99.5* | 40.2* | 49.6 | 40.4* |

| Mentions ACA or Obamacare | 27.4 | 47.4 | 11.0* | 10.2* | 31.9 | 4.9* | 46.3* | 32.6 | 28.6 | 17.6* |

| Mentions state or federally-facilitated Marketplace | 26.9 | 40.1 | 18.8* | 11.7* | 8.7 | 28.3* | 77.2* | 7.5* | 27.3 | 23.2* |

| Mentions healthcare.gov website | 19.2 | 33.0 | 5.8* | 9.9* | 0.6 | 0.0* | 99.4* | 1.5* | 19.6 | 15.0* |

| healthcare.gov website | ||||||||||

| Airings (%) | 100.0 | 45.7 | 31.4 | 23.0 | 53.0 | 26.7 | 18.9 | 1.3 | 89.8 | 10.2 |

Note: Any mention of health law includes: mentions ACA or Obamacare, mentions state or federally-facilitated Marketplace, mentions healthcare.gov website. Mentions ACA or Obamacare includes: Obamacare or Affordable Care Act or ACA or Health care law or the president's (or Obama's) health care law or Health reform or health care reform. Insurance companies category includes private brokers.

Refers to difference from Open Enrollment 1 (versus 2 and 3), differences from Insurance companies (versus other advertisement sponsors), and differences from English language (versus Spanish language) at 0.05 significance level

The proportion of airings mentioning the two most common messages, plan choice and the availability of low cost plans, declined over time. Between open enrollment period 1 and 3, mention of these messages dropped from 70.6 to 41.4% and from 64.6% to 46.3%, respectively. In contrast, the proportion of advertisement airings mentioning the availability of financial assistance with premiums and avoiding tax penalties increased dramatically. Airings noting the availability of financial assistance increased from 41.4% in period 1 to 56.6% in period 2 and 54.3% in period 3, and airings noting avoidance of tax penalties increased from 1.5% in period 1 to 20.1% in period 2 and 16.3% in period 3.

As indicated in Table 3, we also identified differences in the types of informational messages by the sponsor and the language of airings. Insurance companies, for example, were more likely to emphasize the availability of assistance with enrollment and the benefits of accessing high quality medical care in their advertisements relative to other sponsors. Spanish language advertisements were significantly more likely to mention the availability of financial assistance (60.8% versus 47.8%) and enrollment assistance (49.5% versus 39.8%) compared with English language advertisements, but were less likely to mention preventive services (11.4% versus 30.2%), the simplicity of the enrollment process (14.4% versus 23.1%) or the high quality of care (2.2% versus 19.6%).

Nearly half of all airings (48.7%) included some mention of the health care law (i.e., the ACA or Obamacare, the state or federally-facilitated Marketplaces, or the healthcare.gov website), but this proportion dropped substantially over time from 69.8 percent in open enrollment 1 to 30.9% in period 3 (see table 3). Likewise, the subset of airings specifically mentioning the ACA or Obamacare (excluding the state or federally-facilitated Marketplaces, or the healthcare.gov website) fell from 47.4% of airings in period 1, to 10.2% in period 3. As expected, nearly all airings sponsored by the federally-facilitated Marketplace mentioned the healthcare.gov website (99.4%), and the federally sponsored airings were also more likely to mention specifically the ACA or Obamacare (46.3%) relative to other sponsors. Spanish language airings were less likely than English language airings to include any mention of the health care law (40.4 versus 49.6) or a specific mention of the ACA or Obamacare (17.6% versus 28.6%).

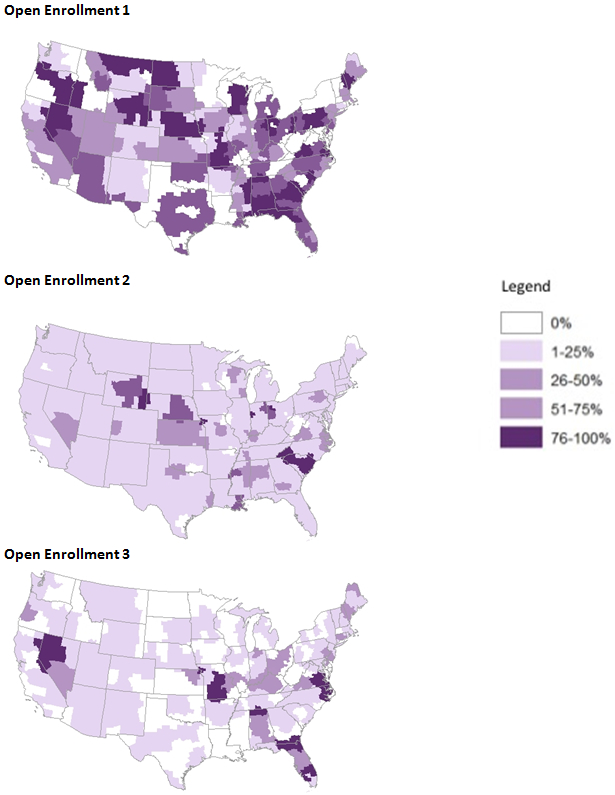

As shown in Figure 2, there was substantial geographic variation in specific references to the ACA or Obamacare in airings across the 210 US media markets. The sharp drop in explicit mentions of the ACA or Obamacare that occurred over time was not restricted to any specific location of the country.

Figure 2.

Geographic Variation Health Insurance Advertisements Airings Mentioning the ACA or ObamaCare by Open Enrollment Period

Regression results in the second column of Table 2 confirm that, controlling for other airings-level characteristics, advertisements aired in enrollment periods 2 and 3 were significantly less likely to mention the ACA or Obamacare explicitly relative to period 1, consistent with the patterns demonstrated in the maps in Figure 2. Compared with those sponsored by state Marketplaces, advertisements sponsored by insurance companies, federal Marketplaces and other sponsors were more likely to mention the ACA or Obamacare in airings. Relative to other airings, those in English (relative to Spanish) and those that aired in media markets with higher uninsurance rates were more likely to explicitly mention the ACA or Obamacare. Surprisingly, media markets voting in higher proportions for President Obama in the 2012 election had lower odds of explicitly mentioning the ACA or Obamacare.

DISCUSSION

Television advertising has been a primary method in communicating to uninsured Americans and the general public about health insurance products newly available in 2014 under key provisions of the ACA. A majority of the health insurance advertisements airings during the initial three open enrollment periods were sponsored by insurance companies, but state Marketplaces, the federally-facilitated Marketplace and enrollment advocates sponsored advertisements encouraging uninsured Americans to enroll.

Our results indicate an effort to market to younger, healthier individuals. Over time, advertising efforts appeared to focus in a more targeted manner on young, healthy invincibles, with the exception of a slight increase over time in airings featuring overweight or obese individuals. Following the first open enrollment period, media reports of a sicker-than-expected group of newly insured individuals (Rogers 2014) may have prompted insurers and regulators to be more concerned about market stability to refine targeted marketing in subsequent periods.

Over time, fewer airings focused on health plan choice, low cost plans, and availability of free/low cost preventive services, and more airings focused on avoiding penalties, availability of financial assistance, and the simplicity of the enrollment process. These shifts in messaging make sense in the context of widely reported declines in the number of plan choices available within markets as some insurers (e.g., Aetna) chose to abandon the new Marketplaces and large premium increases were reported. In addition, the types of appeals featured in airings differed by the sponsor type in fairly predictable ways. Insurance companies and state Marketplaces that had made sizable investments in enrollment assistance highlighted them in their advertising more than federal Marketplaces. It appears likely that sponsors used advertisements to highlight the aspects of their plans prospective enrollees might find most appealing in a highly competitive market.

We also observed dramatic declines over time in explicit mention of the health care law. The proportion of airings explicitly mentioning either the ACA or Obamacare dropped to only 10 percent by open enrollment period 3, indicating that advertisement sponsors increasingly shied away from connecting insurance products with the law. This finding might be best understood through the lens of the submerged state. Public opinion data has consistently shown that many Americans do not understand the law nor do they believe they have benefited from it until, in the era of the Trump Presidency and a Republican Congress, these benefits have been under threat of being taken away (Sanger-Katz 2017). The theory of the submerged state predicts that public support for governmental programs will be lower when citizens fail to understand the connection between the actions of government and the benefits they are receiving. This could help explain the paradoxical phenomenon that some Americans who have directly benefited from the health care law express opposition to it. If advertisement sponsors do not highlight that certain private insurance options (e.g., those outside of employer-sponsored insurance) are only available and affordable due to the health care law (via establishment of new Marketplaces, availability of government subsidies, changes in guaranteed issue, etc.) then consumers might not readily understand the government’s role in what they understand to be a purely commercial enterprise.

This raises the question of why some media markets continued to reference ACA/Obamacare in their airings. We explored this by examining the media markets where over 75% of airings mention ACA/Obamacare in open enrollment period three, and they were fairly geographically dispersed with 8 were in the South (4 in Florida, 2 in Virginia, 1 in North Carolina, 1 in Alabama); 3 were in Missouri and 1 was in Nevada. The specific media markets were: Tallahassee FL; Norfolk VA; Greenville NC; West Palm Beach FL; Richmond VA; Jacksonville FL; Ft Myers FL; Columbia MO; Springfield MO; St. Joseph MO; Huntsville AL; and Reno NV. No obvious shared characteristics were evident that connected these locations. Additionally, as Figure 2 indicates, these regions with a high share of airings mentioning the ACA/Obamacare differ from the markets with high mentions during the second open enrollment period.

Given the absence of a clear pattern, it is important to note that another possible explanation of declines in mentions of the ACA/Obamacare following the initial open enrollment period was that advertisers learned from enrollment period 1 that reference to the law was not a particularly motivating reason to enroll in insurance, even among those that favor the law. In other words, this may not have been an effort to intentionally distance the marketing of new insurance options from the ACA, but rather a strategy to move toward enrollment messages viewed as more persuasive by advertisement sponsors.

We detected some important differences in advertisements appearing in Spanish. For example, Spanish language advertisements were more likely (9.8% vs. 7.5%) to include depictions of people receiving care in a medical setting. Latinos have higher rates of uninsurance (Doty et al. 2015) and also tend to be younger and healthier than other groups.(“CDC Vital Signs: Hispanic Health” 2015) For these reasons, marketers may have viewed the advantages of showing people receiving services in health care settings outweighing the risk of attracting enrollment among sicker individuals.

Both theory and empirical research suggest that the content of television advertising shapes public perceptions about the ACA, changes in insurance rates, and individuals’ information-seeking and uptake of marketplace plans. Our findings indicate that, while ACA insurance advertising messages have evolved overtime, people continue to hear different messages about the law based on who they are and where they live. Given what we know how media affects public attitudes and consumer behaviors, it is not surprising that views on the law continue to be highly contentious and hinge in part on attitudes about and trust in government.

Several limitations are important to note. First, kappa statistics confirming high inter-rater reliability are limited to English language advertisements with Spanish language advertisements coding performed by a single author (JP). Therefore, we are unable to assess reliability in coding for Spanish language advertisements. Despite this limitation, it is important to note that all three authors were involved in an extensive coder training process that included detailed debriefing about coding differences, and all three worked closely on pilot testing of the instrument. For these reasons, our expectation is that coding differences between English and Spanish language advertisements will be minimal. Second, while this study sheds light on how television advertisements portrayed insurance products newly available through the ACA, it does not directly provide insights on how exposure to media influenced public attitudes about the law and product purchasing behavior. Third, we were unable to calculate kappa statistics for focal persons with disabilities and smoking tobacco because no unique advertisements including these images were included in our double-coded sample (see appendix B). Fourth, we are unable to compare the content of insurance product advertisements during ACA open enrollments with pre-ACA advertising strategies. The question of how the approaches used by health insurers shifted with the entry of new products into the marketplace following the ACA is an important unanswered question. Fifth, and related, while all of the ads examined were aired corresponding with the timing of open enrollment periods 1 through 3, some of the ads from insurance-company sponsored may have been targeted for their non-marketplace products such as employer-sponsored insurance; we did not determine at the level of each creative which ad was for a product available on-exchange, off-exchange, or only for employer-sponsored plans.

Finally, as noted, we excluded creatives that aired exclusively on a national network or cable advertising because we wanted to ensure geographic representation of messages airing at the local level throughout the country. Importantly, this means that advertisements that aired on both local broadcast and national networks remained in the sample. The vast majority of advertising that aired on national network or cable outlets also ran on local broadcast: 73% of unique creatives and 89% of airings were still eligible for inclusion. While it is possible that the content of insurance product advertising airing exclusively on national network news or national cable differed in important respects from other advertisements, they represent a small proportion (11 percent) of all airings that ran nationally (whether exclusively or on both national and local television), and an even smaller proportion (0.3 percent) of the universe of airings available for analysis.

The future of health insurance in the U.S. remains murky in the context of an ongoing, highly polemic national debate. In the period since our data collection effort concluded, the type and volume of informational messages appears to have shifted with reports the Trump administration has pulled advertisements and outreach efforts encouraging people to sign up for health insurance under the law (Park 2017). In this rapidly-evolving environment, whether and how marketing messages are transmitted to consumers will influence purchasing decisions. Equally important, the nature of advertising will impact the broader public’s views on the appropriate role of government in the health insurance landscape going forward.

CONCLUSION

Television advertising constitutes one important source of information available to consumers and the broader public about the health plan options newly available starting in 2014 under the ACA. Sponsors’ choices about the volume and content of television advertisements aired around the country can influence who should consider enrolling, the advantages of enrolling in one plan over another, and the public’s perceptions about role of government in facilitating broader access to insurance via individual and small group Marketplace options. Results indicate that, over the three open enrollments, advertisement sponsors increasingly targeted appeals to young, healthy consumers. Additionally, advertisement sponsors altered the informational content as market dynamics changed (e.g., focusing less on plan choice overtime as choices dwindled within markets), and increasingly opted against explicitly connecting the insurance products with the health law. These strategies all make sense from a business standpoint, and the viability of the law over the longer term will depend in part on advertising sponsors’ ability to successfully market plans that will appeal to a sufficiently large, diverse group.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Consumers have also learned about new insurance options available under the ACA through other sources including political advertising, news media coverage, social media, and direct outreach efforts by brokers, navigators, and consumer advocates.

REFERENCES

- Ball-Rokeach SJ, and DeFleur ML. 1976. “A Dependency Model of Mass-Media Effects.” Communication Research 3 (1): 3–21. 10.1177/009365027600300101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blidook Kelly. 2008. “Media, Public Opinion and Health Care in Canada: How the Media Affect ‘The Way Things Are.’” Canadian Journal of Political Science / Revue Canadienne de Science Politique 41 (2): 355–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cutlip Scott M. 1994. The Unseen Power: Public Relations: A History. Routledge; Hillsdale, New Jersey. [Google Scholar]

- “CDC Vital Signs: Hispanic Health.” 2015. United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/pdf/2015-05-vitalsigns.pdf.

- “DMA Regions.” 2013. The Nielsen Company. 2013. http://www.nielsen.com/intl-campaigns/us/dma-maps.html.

- Doty Michelle, Beutel Sophie, Rasmussen Petra, and Collins Sara. 2015. “Latinos Have Made Coverage Gains but Millions Are Still Uninsured.” The Commonwealth Fund Blog (blog). April 27, 2015. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/blog/2015/apr/latinos-have-made-coverage-gains.

- Fowler Erika Franklin, Baum Laura M., Barry Colleen L., Niederdeppe Jeff, and Gollust Sarah E.. 2017. “Media Messages and Perceptions of the Affordable Care Act during the Early Phase of Implementation.” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 42 (1): 167–95. 10.1215/03616878-3702806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollust Sarah E., Barry Colleen L., Niederdeppe Jeff, Baum Laura, and Fowler Erika Franklin. 2014. “First Impressions: Geographic Variation in Media Messages during the First Phase of ACA Implementation.” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 39 (6): 1253–62. 10.1215/03616878-2813756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollust SE, Wilcock A, Fowler EF, Barry CL, Niederdeppe J, Baum LM, Karaca-Mandic P. “TV Advertising Volumes Were Associated with Individuals’ Health Insurance Marketplace Shopping and Enrollment Behaviors in 2014” Under review, Health Affairs. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaca-Mandic Pinar, Wilcock Andrew, Baum Laura, Barry Colleen L., Fowler Erika Franklin, Niederdeppe Jeff, and Gollust Sarah E.. 2017. “The Volume Of TV Advertisements During The ACA’s First Enrollment Period Was Associated With Increased Insurance Coverage.” Health Affairs, March, 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1440. 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, and Koch GG. 1977. “The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data.” Biometrics 33 (1): 159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard Kimberly. 2016. “‘Young Invincibles’ Remain Elusive for Obamacare.” US News and World Report, September 7, 2016. https://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2016-09-07/young-invincibles-remain-elusive-for-obamacare.

- Levine Deborah, and Mulligan Jessica. 2017. “Mere Mortals: Overselling the Young Invincibles.” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 42 (2): 387–407. 10.1215/03616878-3766781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mettler Suzanne. 2011. The Submerged State: How Invisible Government Policies Undermine American Democracy Chicago Studies in American Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mutz Diana C. 1992. “Impersonal Influence: Effects of Representations of Public Opinion on Political Attitudes.” Political Behavior 14 (2): 89–122. 10.1007/BF00992237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park Haeyoun. 2017. “4 Ways Trump Is Weakening Obamacare, Even After Repeal Plan’s Failure.” The New York Times, July 19, 2017, sec. U.S. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/07/19/us/what-trump-can-do-to-let-obamacare-fail.html.

- Rogers Kate. 2014. “Early ACA Enrollees Were Sicker Than Average.” Fox Business, April 9, 2014. http://www.foxbusiness.com/features/2014/04/09/report-early-aca-enrollees-were-sicker-than-average.html.

- Sanger-Katz Margot. 2017. “Obamacare More Popular Than Ever, Now That It May Be Repealed.” The New York Times, February 1, 2017, sec. U.S. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/02/01/us/politics/obamacare-approval-poll.html.

- Soroka Stuart, Maioni Antonia, and Martin Pierre. 2013. “What Moves Public Opinion on Health Care? Individual Experiences, System Performance, and Media Framing.” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 38 (5): 893–920. 10.1215/03616878-2334656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Story Mary, and French Simone. 2004. “Food Advertising and Marketing Directed at Children and Adolescents in the US.” The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 1 (1): 3 10.1186/1479-5868-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West Darrell M, Heith Diane, Goodwin Chris. 1996. Harry and Louise Go to Washington: Political Advertising and Health Care Reform. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. (1996) 21 (1): 35–68. 10.1215/03616878-21-1-35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.