Abstract

Objective:

This article examines adoption as a strategy used by parents to fulfill their preference for a specific sex composition among their children in the United States.

Background:

Evidence from the United States suggests that parents with children of the same sex are more likely to continue childbearing, as parents generally desire at least one girl and one boy. What is unknown, however, is whether parents use adoption to fulfill this same preference.

Method:

Using data from the 2016 American Community Survey (n=1,107,800 children), the authors test the relationships among the sex composition of preceding siblings, child sex, and adoption status.

Results:

Children who had same-sex preceding siblings were more likely to be adopted, as opposed to biologically related to their parents, than children who had mixed-sex preceding siblings. Further, adopted children were more likely to be of the missing sex (i.e., adopted girls were more likely than were adopted boys to have only preceding brothers).

Conclusion:

These findings suggest a need to consider parental sex preferences and child sex in studies on adoption decisions. Further, adoption provides one mechanism parents can use to achieve a balanced sex composition among their children.

Keywords: Adoption, Gender, Siblings, Children, Demography, Family Formation

Parents in the United States tend to prefer a “balanced” family, with at least one boy and one girl (for a review, see Lundberg, 2005). Several researchers have found that parents with children of the same sex are more likely to continue childbearing in the pursuit of creating a gender-balanced family than are parents with one son and one daughter (e.g., Ben-Porath & Welch, 1976; Tian & Morgan, 2015). What remains unknown, however, is whether parents use adoption as an alternate strategy to fulfill these preferences.

Adoption may pose a strategy that is more efficient for parents wishing to fulfill their sex preferences. As opposed to childbearing, adoption grants parents greater control over the demographic characteristics of their children, as parents can decide whether to adopt based on the characteristics of the child. Therefore, as total fertility rates remain near or below replacement level (2.1 children per woman) in many industrialized countries, adoption could be important to parents seeking to fulfill their preference for a gender-balanced family while avoiding having excess children.

We use data from the American Community Survey (ACS) to examine the relationships among the sex composition of preceding siblings, child sex, and adoption status. This study provides the first representative assessment of the role sex preferences play in U.S. adoption.

Background

Sex Preferences for Children

Research in the United States has documented that parents continue childbearing if they have same-sex children, presumably to fulfill their preference for at least one boy and one girl. For example, Ben-Porath and Welch (1976) found a U-shaped relationship between the probability of having more children and the ratio of boys to the total number of children parents already had. Thus, parents without a son or a daughter are more likely to continue childbearing, presumably to create a balanced family. Similar studies across many European countries support these findings (e.g., Andersson, Hank, Ronsen, & Vikat, 2006; Hank & Kohler, 2000).

The strength of these preferences has changed over time. Pollard and Morgan (2002), using multiple cycles of two nationally representative surveys from 1980–1995, found that the relationship between the sex composition of children and continuation to a third birth weakened over time in the United States, leading to gender indifference. They attributed this to the gender revolution, which refers to women’s significant advances in education, politics, and employment, as well as the many anti-discrimination laws passed during the last half of the 20th century (England, 2010). One consequence of this revolution, they argued, is that boys and girls appeared to become increasingly similar and, therefore, more substitutable. In a follow-up study, Tian and Morgan (2015) found that, although the relationship between the sex composition of existing children and continued childbearing between 1986 and 1995 weakened, this relationship did not continue to weaken post-1996. The researchers concluded that this attenuation was consistent with a “stalled” gender revolution, as men hesitate to participate in traditionally feminine spheres (e.g., housework) (England, 2010).

There are several reasons why parents might prefer a certain sex composition among their children. In the United States, parents typically do not consider sons and daughters to be interchangeable; American parents perceive that boys and girls have their own “traits, strengths, leisure activities, and interests” (Williamson, 1976, p. 22). Parents may view the familial roles sons and daughters play as distinct and, therefore, wish to maximize family functioning by having at least one son and one daughter. Further, parents may also wish to expand their parenting experience by participating in activities relevant to both sons and daughters. It is also possible that parents gain symbolic status by achieving a balanced, ideal family (Nugent, 2013). Both mothers and fathers in the United States appear to have at least a slight preference for a child of their same sex (Dahl & Moretti, 2008). Perhaps parents feel they could better assist a child of their same sex to navigate rites of passage, activities, and developmental changes that are unique to their sex. For example, many consider fathers a vital developmental influence in their sons’ lives because they can model appropriate masculinity and help their sons avoid antisocial behaviors (Edin & Nelson, 2013). Therefore, among heterosexual couples, parents may want a child of each sex.

Adoption and Sex Preferences

Adoption provides unique insight into families as social constructs (Fisher, 2003). We can more fully assess parental preferences through adoption, than solely through childbearing, because parents have a great deal of control over the characteristics of their children. Ishizawa and Kubo (2014) found that adoptive parents chose the type of adoption they pursued in order to fulfill their preferences for a child of a particular age and race. Parents who wanted a child of their same race, for example, were more likely to utilize domestic, as opposed to international, adoption.

A small body of research on parental sex preferences considers adoption as a strategy to fulfill these preferences. This research focuses predominantly on China and India. For example, Chen, Ebenstien, Edlund, and Li (2015) found that parents placed more girls for adoption than they did boys in China, presumably due to son preference. Further, families without children or those with older sons tended to adopt girls in this context (e.g., Chen, Ebenstien, Edlund, & Li, 2015; Lid, Larsen, & Wyshak, 2004). Therefore, the sex composition of preceding children and the child’s sex were important to adoption decisions.

Two studies using non-representative samples of adoptive and prospective adoptive parents specifically examined sex preferences in the United States. Brooks, James, and Barth (2002) found that adoptive parents did not have strong preferences for one sex over the other, whereas Baccara, Collard-Wexler, Felli, and Yarvis (2010) found that potential adoptive parents favored girls. Neither study considered the sex composition of existing children nor used representative data. We address these gaps in the present study.

Current Study

To our knowledge, this study is the first representative assessment of the relationship between the sex composition of preceding siblings and adoption in the United States. We used data from the 2016 ACS to test the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Children are more likely to be adopted if their preceding siblings are same-sex children (only boys or only girls) than if their siblings are mixed-sex.

Hypothesis 2: Adopted children with same-sex preceding siblings are more likely to be of the missing sex (i.e., female children are more likely than male children to be adopted into families comprised of only boys).

Method

Data and Sample

We tested our hypotheses using data from a 2016 sample of the American Community Survey (ACS), available in the database of the Integrated Public Use Microdata Samples (IPUMS) (https://usa.ipums.org/usa/acs.shtml) (Ruggles, Genadek, Goeken, Grover, & Sobek, 2017). In 2010, the survey replaced the decennial census as the main source of information gathered in the long-form questionnaire that asked questions on issues such as disability status, employment, and household characteristics. The ACS provides data on adoption status, making it the largest source of information on the characteristics of adopted children and their parents in the United States. We used the five-year 2016 sample, which provides the most recent nationally representative data of the U.S. population and contains a larger number of adopted children compared to those found in other surveys like the National Survey of Adoptive Parents.

Our analyses focused only on children (individuals 18 years old or younger). There were 3,317,167 children in surveyed households of the 2016 American Community Survey. We excluded children for whom we did not have reliable information regarding their preceding siblings or adoption status. First, we excluded 1,770 children who were listed either as the head of the household or as the spouse of the head of the household. Second, we excluded 30,408 children who did not have a head of household listed, which largely included institutionalized children. Third, we excluded 231,784 children who lived in a family with multiple children of the same age (e.g., twins) to avoid assigning one (or more) multiple(s) as a preceding and one as a following sibling. Fourth, we excluded 383,576 children whose youngest parent was over the age of 50 to avoid families with adult children (over age 18), as these children are more likely to be non-resident and, therefore, not listed in the household. Fifth, we excluded 224,411 children who were not listed as a biological or adopted child, including step-children, foster children, and grandchildren, because their adoption status was unclear. Finally, we deleted 1,337,418 children who did not have preceding siblings, because it was not possible to make inferences about their parents’ sex preferences. Our final sample included 1,107,800 children placed in households with at least two resident children age 18 or younger. There were no missing data.

Our sample differed from a sample of all households with children 18 years old or younger (n=3,284,989). Several of these differences are due to our exclusion of children with no preceding siblings: children in our sample were younger and fewer were adopted. Further, due to our parental age criterion, children in our sample had younger parents, on average. Finally, due to our exclusion of children in foster care, stepchildren, and grandchildren, our sample had fewer children with disabilities, foreign-born children, and more children with married parents (see Table A1 in the online supplementary material).

Measures

Dependent variables.

Our first dependent variable was a dichotomous indicator of whether a child was adopted or not, as reported by the household head (1=adopted, 0=not adopted). Our second dependent variable indicated whether the adopted child was female (1=female, 0=male).

Key independent variable.

Our primary independent variable was the sex composition of preceding siblings. Considering all siblings who were older than the index child was, we created a categorical variable indicating whether preceding siblings were 1=only sisters, 2=only brothers, or 3=included at least one brother and one sister.

Control variables.

We accounted for several characteristics of the index child and household. We accounted for the child’s age, in years, and disability status, indicating whether the child had cognitive, ambulatory, self-care, or independent living difficulty (1=child has difficulty, 0=child does not). Previous researchers have linked children’s disability status to adoption decisions (Chandra, Abma, Maza, & Bachrach, 1999). We also accounted for the race/ethnicity of the child (1=non-Hispanic black, 2=Hispanic, 3=non-Hispanic white, 4=Asian, 5=other race or ethnicity), whether the child was foreign born (1=immigrant, 0=not immigrant), and whether the child had a preceding adopted sibling (1=yes, 0=no). Past research shows that adoptive parents are more likely to be married, older, and have more education than non-adoptive parents (Jones, 2009; Thomas, 2016). Therefore, we accounted for parental marital status (1=married, 0=not married), the age of the oldest parent, in years, and the highest education of either parent (1=less than high school, 2=high school, and 3= some college or more). If we identified only one parent for a child, we included this parent’s characteristics. We also accounted for the number of children in the household, the sex of the household head (1=female, 0=male), and the race/ethnicity of the household head (1=non-Hispanic black, 2=Hispanic, 3=non-Hispanic white, 4=Asian, 5=other race or ethnicity).

Analytic Strategy

We estimated several logistic regression models. We first examined the relationship between the sex composition of preceding siblings and the adoption status of the index child (H1). We then estimated a model predicting adoption status, which included an interaction between the child’s sex and the sex composition of preceding siblings (H2). Finally, we limited our sample to adopted children (n=18,029) to observe the relationship between the proportion of girls among preceding siblings and the sex of the adopted child. Our models controlled for child and household characteristics. To account for dependency among children in the same household, we estimated robust standard errors using the cluster command in Stata 14.

Results

Our results show that adoption was a rare occurrence; just under two percent of children in our sample were adopted (see Table 1). Regardless of adoption status, there was substantial variation in the sex composition of preceding siblings. For the entire sample, approximately 16 percent had at least one sister and brother preceding them, 43 percent of children had preceding brothers only, and 41 percent had preceding sisters only.

Table 1.

Means of Characteristics of Children, Aged 0–18, by Adoption Status, 2016, United States

| All Children (n=1,107,800) |

Adopted (n=18,029) |

Not Adopted (n=1,089,771) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of the Child | |||

| Adopted | 0.02 | -- | -- |

| Sex composition of preceding siblings | |||

| At least one brother and one sister | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.16 |

| Only brothers | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.43 |

| Only sisters | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.41 |

| Female | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.49 |

| Age | 6.87 | 7.56 | 6.86 |

| Disability | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.02 |

| Race/Ethnicity of child | |||

| White | 0.58 | 0.48 | 0.59 |

| Hispanic | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.22 |

| Black | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.09 |

| Asian | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.05 |

| Other | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.06 |

| Foreign born | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.02 |

| Preceding adopted sibling | 0.02 | 0.62 | 0.01 |

| Characteristics of the Household | |||

| Parents married | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.76 |

| Age of oldest parent | 39.41 | 43.31 | 39.34 |

| Highest education of either parent | |||

| Some college or more | 0.74 | 0.81 | 0.74 |

| High school | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.16 |

| Less than high school | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.10 |

| Number of children in the household | 2.89 | 3.04 | 2.89 |

| Female household head | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.52 |

| Race/Ethnicity of household head | |||

| White | 0.62 | 0.75 | 0.62 |

| Hispanic | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.20 |

| Black | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.10 |

| Asian | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| Other | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

Data: American Community Survey 2016

Adopted children were more often female (53 percent of adopted children compared to 49 percent of non-adopted children), disabled (8 percent of adopted children vs. 2 percent of non-adopted children), foreign-born (17 percent of adopted children vs. 2 percent of non-adopted children), and less often white (48 percent of adopted children vs. 59 percent of non-adopted children) than non-adopted children. These findings likely reflect the “supply” of children available for adoption. Further, adopted children had a preceding adopted sibling much more often than non-adopted children did. As expected, adopted children more often resided in advantaged households than non-adopted children in terms of marital status, educational attainment, and race of their parents (Jones, 2009; Thomas, 2016).

Our results support our first hypothesis that children are more likely to be adopted if their preceding siblings are of the same sex (see Table 2, Model 1). However, this relationship was stronger for girls. Children with preceding brothers only were 46 percent more likely, and children with preceding sisters only were 29 percent more likely, to be adopted than children with preceding brothers and sisters (p<0.001). Female children were 20 percent more likely to be adopted than males were, and children with disabilities were 210 percent more likely to be adopted than were non-disabled children. Children’s age had a nonlinear relationship with adoption with the probability of adoption increasing until age 4 and then slightly decreasing. White children were significantly less likely to be adopted compared to children of all other races and ethnicities, whereas children born outside of the United States were significantly more likely to be adopted. Finally, having a preceding adopted sibling was a strong predictor of adoption status. Children with preceding adopted siblings were 158 times more likely to be adopted than were children without a preceding adopted sibling (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Predicting Adoption of Children 18 Years or Younger in the United States, 2016

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | OR | B | SE B | OR | |

| Characteristics of the Child | ||||||

| Sex composition of preceding siblings | ||||||

| At least one brother and one sister (r) | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Only brothers | 0.38*** | 0.03 | 1.46 | 0.21*** | 0.04 | 1.23 |

| Only sisters | 0.25*** | 0.03 | 1.29 | 0.30*** | 0.04 | 1.35 |

| Female | 0.18*** | 0.02 | 1.20 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 1.07 |

| Only brothers * Female | 0.33*** | 0.06 | 1.40 | |||

| Only sisters * Female | −0.08 | 0.06 | 0.93 | |||

| Age | 0.05*** | 0.01 | 1.05 | 0.05*** | 0.01 | 1.05 |

| Age^2 | −0.004*** | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.005*** | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Disability | 1.13*** | 0.04 | 3.10 | 1.13*** | 0.04 | 3.10 |

| Race/Ethnicity of child | ||||||

| White (r) | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Black | 3.17*** | 0.07 | 23.81 | 3.17*** | 0.07 | 23.79 |

| Hispanic | 1.30*** | 0.05 | 3.67 | 1.30*** | 0.05 | 3.67 |

| Asian | 3.83*** | 0.06 | 46.02 | 3.82*** | 0.06 | 45.50 |

| Other | 1.16*** | 0.05 | 3.21 | 1.17*** | 0.05 | 3.21 |

| Foreign born | 1.82*** | 0.03 | 6.20 | 1.82*** | 0.03 | 6.18 |

| Preceding adopted sibling | 5.06*** | 0.02 | 158.21 | 5.07*** | 0.02 | 158.81 |

| Characteristics of the Household | ||||||

| Married parents | −0.11*** | 0.03 | 0.89 | −0.11*** | 0.03 | 0.89 |

| Age of oldest parent | 0.11*** | 0.01 | 1.11 | 0.11*** | 0.01 | 1.11 |

| Highest education of either parent | ||||||

| Some college or more (r) | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||

| High school | 0.02 | 0.03 | 1.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 1.02 |

| Less than high school | −0.18*** | 0.05 | 0.84 | −0.18*** | 0.05 | 0.84 |

| Number of children in the household | 0.07*** | 0.01 | 1.08 | 0.07*** | 0.01 | 1.08 |

| Household head is female | 0.23*** | 0.02 | 1.25 | 0.23*** | 0.02 | 1.25 |

| Race/Ethnicity of household head | ||||||

| White (r) | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Black | −2.95*** | 0.09 | 0.05 | −2.95*** | 0.09 | 0.05 |

| Hispanic | −1.30*** | 0.06 | 0.27 | −1.30*** | 0.06 | 0.27 |

| Asian | −4.26*** | 0.09 | 0.01 | −4.25*** | 0.09 | 0.01 |

| Other | −0.89*** | 0.07 | 0.41 | −0.89*** | 0.07 | 0.41 |

N 1,107,800

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Data: American Community Survey 2016

Note. N=88,239 for at least one brother and one sister *female

N=232,551 for only brothers*female

N=220,744 for only sisters*female

N=91,833 for at least one brother and one sister*male

N=246,121 for only brothers*male

N=228,312 for only sisters*male

In terms of household characteristics, children with married parents were 11 percent less likely to be adopted than children with unmarried parents, once accounting for other parental characteristics, such as educational attainment, that influence the likelihood of marriage. As expected, children of parents with less than a high school education were 16 percent less likely to be adopted than those with parents who had some college or more, and children were more likely to be adopted when residing in households with a larger number of children. Finally, children with older parents or a female head of household had higher odds of being adopted. Children with a white head of household were more likely to be adopted than were children with a head of household of another race or ethnicity.

Large sample sizes lead to small standard errors, which can increase the risk of Type I errors. Therefore, we estimated a measure of model fit using Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). We estimated BIC for a model predicting adoption with all controls except the sex composition of preceding siblings (BIC=99,297.62) and a model with all predictors (BIC=99,175.05). A difference of 10 provides very strong evidence of an improved model with smaller values indicating a more efficient model (Raftery, 1995). Including the sex composition of preceding siblings decreased the BIC by about 123, indicating that this variable improved model fit substantially.

To test our second hypothesis, that children are more likely to be adopted into households if they balance their household’s sex composition (e.g., female children are more likely to be adopted if they have preceding brothers only), we included an interaction between child sex and the sex composition of preceding siblings (Table 2, Model 2). Our results partially support this hypothesis. Female children were significantly more likely than male children were to be adopted if they had no preceding sisters (p<0.001). Female children were less likely than male children were to be adopted if they had no preceding brothers, but this relationship was not statistically significant.

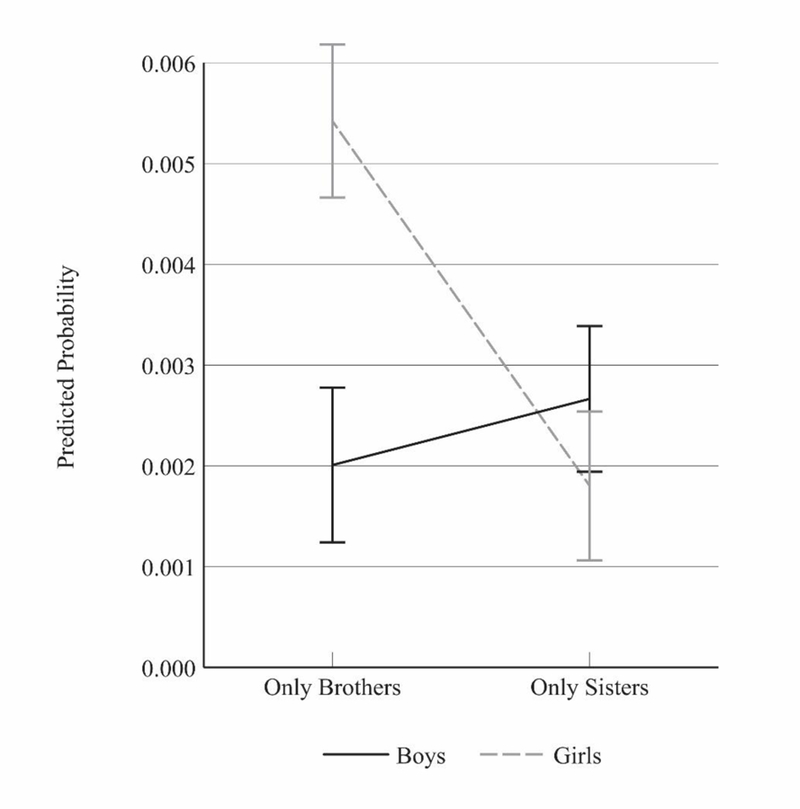

Figure 1 displays the predicted margins from the presented interaction. In accordance with the regression results presented in Table 2, Model 2, girls with only preceding brothers had a higher predicted probability of adoption than girls with only preceding sisters did. The reverse was true for boys. Boys with only preceding brothers had a lower predicted probability of adoption than boys with only preceding sisters did, but this relationship was not statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Average Predicted Association Between Adoption And Preceding Sibling Sex Composition By Child Sex

To test our second hypothesis further, we limited our analysis to adopted children (n=18,029) and measured the sex composition of preceding siblings as the percentage of preceding siblings who were female (see Table 3). Here, we see that as the percentage of girls in the preceding sibship increased, the likelihood of an adopted child being female decreased. The reverse is also true: as the percentage of girls in the preceding sibship increased, the odds of an adopted child being male increased. We also tested a quadratic term that was not statistically significant, indicating that this relationship is linear (results not shown). This result supports our conclusion that parents use adoption to ensure a child of each sex.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Predicting Child Sex (Female) of Adopted Children 18 Years or Younger in the United States, 2016

| B | SE B | OR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of the Child | |||

| Sex ratio of preceding siblings | |||

| (# of preceding sisters / # of preceding siblings) | −0.28*** | 0.03 | 0.76 |

| Age | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.01 |

| Disability | −0.49*** | 0.06 | 0.61 |

| Race/Ethnicity of child | |||

| White (r) | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Black | −0.18** | 0.06 | 0.83 |

| Hispanic | 0.00 | 0.05 | 1.00 |

| Asian | 0.67*** | 0.07 | 1.96 |

| Other | 0.04 | 0.06 | 1.04 |

| Foreign born | 0.05 | 0.05 | 1.06 |

| Preceding adopted sibling | −0.15 | 0.03 | 0.86 |

| Characteristics of the household | |||

| Married parents | 0.03 | 0.04 | 1.03 |

| Age of oldest parent | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Highest education of either parent | |||

| Some college or more (r) | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| High school | −0.11 | 0.08 | 1.01 |

| Less than high school | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.89 |

| Number of children in the household | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.99 |

| Household head is female | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.99 |

| Race/Ethnicity of household head | |||

| White (r) | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Black | 0.33*** | 0.08 | 1.39 |

| Hispanic | 0.12* | 0.06 | 1.13 |

| Asian | −0.46*** | 0.11 | 0.63 |

| Other | 0.00 | 0.10 | 1.00 |

N 18,029

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Data: American Community Survey 2016

Our results also show that adopted children with disabilities were significantly less likely to be female than male. Similarly, black adopted children were significantly less likely to be female than male when compared to white adopted children. Asian adopted children were significantly more likely to be female and children with a preceding adopted sibling were significantly less likely to be female. Further, adopted children with black or Hispanic parents were more likely to be female than male whereas children with Asian parents were less likely to be female.

With respect to model fit, the BIC for a model predicting the sex of adopted children including all independent variables but the sex composition of preceding siblings was 24,801.14, whereas the BIC for a model predicting the sex of adopted children including the sex composition of preceding children was 24,742.26. This finding indicates a difference of nearly 59, providing strong evidence that including the sex composition of preceding children significantly improves model fit when predicting the sex of adopted children (Raftery, 1995).

Sensitivity Analyses

To test the robustness of the presented results, we conducted a number of sensitivity tests under eight distinct specifications: (a) we limited the sample of adopted children to those who were foreign-born, as we could better infer when these children underwent adoption by using their entry date into the United States; (b) we tested various cutoffs for parental age by excluding families with parents over 40, 60, and no age restriction; (c) we excluded families who only had adopted children or who had adopted children before having biological children; (d) we included a continuous measure of the percentage of preceding siblings who were female and a quadratic term as our main independent variables in Table 2; (e) we limited the sample to children under 10 and under 6, rather than under 19; (f) we estimated models using the five-year 2014 and 2015 samples of the ACS; (g) we included families with multiple children of the same age (e.g., twins); and (h) we used a parity-progression approach, similarly to Zaidi and Morgan (2016), to avoid conflating sex composition with birth order. Across these additional analyses, the main findings remained generally consistent: children with same-sex preceding siblings were more likely to be adopted and more likely to be the opposite sex of the same-sex preceding siblings. The results of the sensitivity analyses appear in the online supplementary materials (see Tables A2 and A3).

Conclusion

We used 2016 American Community Survey (ACS) data to study the relationship between the sex composition of preceding siblings and adoption status. This is the first study to examine adoption as a strategy for parents to enact their sex preferences in the United States. We found several notable results. First, we found that children whose preceding siblings were of the same sex were more likely to be adopted than were those with at least one preceding sibling of each sex. Although these effects differed for males and females, our results suggest that children with same sex preceding siblings were at least 29 percent more likely to be adopted compared to children with a sibling of each sex. This suggests that children are more likely to be adopted when their preceding siblings have an unbalanced sex composition.

Second, we found that the effect of having only preceding brothers was just over 50 percent larger than the effect of having only preceding sisters on adoption status. Relatedly, third, we found that female adopted children were 40 percent more likely than male adopted children to be in families with no preceding sisters, and that these differences were statistically significant. This finding suggests that parents use adoption to create a balanced sex ratio among their children when they do not have girls. Contrary to our hypotheses, we did not find that female adopted children were significantly less likely than male adopted children were to be in families with no preceding brothers.

There are several possible interpretations of these findings. They could be an indication of daughter preference in the United States. This possibility has some support in previous literature. A recent working paper reported that parents with only boys were more likely to proceed to a next birth than were parents with only girls (Blau, Kahn, Brummund, Cook, & Larson-Koester, 2017). A different study found that potential adoptive parents preferred daughters to sons (Baccara, Collard-Wexler, Felli & Yariv, 2010). The authors argued that this preference could reflect parents’ fears about adopting children with behavioral problems, which some perceive to be more likely with boys. However, we found that girls were less likely than boys were to be adopted into families with only preceding girls, despite this relationship not being statistically significant. Therefore, we did not find strong support for daughter preference. Alternatively, these findings could reflect the supply of children available for adoption, which includes more girls than boys (Budiman & Lopez, 2017), and not necessarily parental preferences for a certain sex composition.

Fourth, our findings revealed that the odds of an adopted child being female decreased, and the odds of being male increased, as the percentage of preceding siblings who were girls increased. This finding further supports the conclusion that parents use adoption to create balanced families in the United States.

It is important to note that parents have many motivations to adopt and that multiple preferences likely play a role in adoption decisions. For example, parents may choose to adopt because they want another child and are unable to conceive (Malm & Welti, 2010), and sex preferences play a secondary or minor role in decision-making. Previous research has demonstrated that race and disability status of children are important characteristics that potential adoptive parents consider (Chandra, Abma, Maza, & Bachrach, 1999). Our results do not allow us to determine the extent to which sex preferences are central to adoption decisions; rather, the results point to the child’s sex as one important factor shaping these decisions.

Our results have implications for the existing literature on both adoption and parental preferences for a specific sex composition in the United States. Our findings suggest that parents in the United States are not indifferent when it comes to the sex composition of their children. Instead, they use several strategies, including adoption, to build families to meet their sex preferences. Therefore, studies that examine parents’ motivations to adopt should consider the role of sex preferences. It is also important to examine adoption decisions within the context of the household, including the sex composition of children preceding the adoption. Further, adoption should not be ignored as an additional strategy used by parents to fulfill their sex preferences.

Our study was subject to several limitations. First, information on parent and child characteristics only included 2016 data; however, it is possible that the adoptions occurred up to 18 years beforehand. Therefore, parental education, marital status, and age are not necessarily reflective of the household context when the adoption occurred.

Second, we did not have information about when adoptions took place; therefore, we assumed that adoptions occurred at birth. Because we had information regarding entry to the United States, we could better infer the date of adoption for foreign-born adopted children. Using this information, we re-estimated models with only internationally adopted children. These results did not support our first hypothesis that children with preceding siblings of the same sex would be more likely to be adopted. Instead, children were less likely to be adopted if their preceding siblings were same-sex. This finding could reflect that other preferences are more important to parents when adopting internationally.

Third, the ACS is cross-sectional. Therefore, we were unable to address the fact that some families in our sample would eventually go on to adopt a child but had not done so before the survey. This right censoring may have resulted in conservative estimates about the relationship between the sex composition of preceding siblings and the adoption status of children. Parents with at least one boy and one girl are less likely to continue having children than parents of same-sex children (for a review, see Lundberg, 2005). Assuming this finding is true for both adoption and childbearing, it would indicate that households with only boys or only girls are even more likely to adopt a child than captured here. Future research would benefit from longitudinal analyses designed to address this type of censoring.

Finally, it was beyond the scope of our study to examine the structural inequalities that play a role in adoption. Adoption is not accessible to parents in all sociodemographic populations due to cost, as well as social and political barriers that determine who is an “appropriate” adoptive parent. For example, children are more likely to be adopted by white, wealthy parents in Western countries (Fisher, 2003; Riley & Van Vleet, 2011). Future research is also necessary to understand how adoption plays a role in the reproduction of structural inequalities and how preferences, including sex preferences, influence these relationships.

Our results provide a compelling new direction for future research. Our results imply that families use adoption, like continued childbearing, to fulfill their desire for a balanced family (Lundberg, 2005). Future research should include sex preferences in studies on parents’ motivations to adopt and examine adoption as a strategy—much like continued childbearing—to fulfill sex preferences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) to the Population Research Institute at The Pennsylvania State University for Population Research Infrastructure (P2C HD041025) and Family Demography Training (T32 HD007514).

References

- Andersson G, Hank K, Ronsen M, & Vikat A (2006). Gendering family composition: Sex preferences for children and childbearing behavior in the Nordic countries. Demography, 43(2), 255–267. 10.1353/dem.2006.0010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccara M, Collard-Wexler A, Felli L, & Yariv L (2010). Gender and racial biases: Evidence from child adoption CESifo Working Paper Series No. 2921. Retrieved from https://cepr.org/active/publications/discussion_papers/dp.php?dpno=7647

- Ben-Porath Y, & Welch F (1976). Do sex preferences really matter? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 90(2), 285–307. 10.2307/1884631 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blau FD, Kahn LM, Brummund P, Cook J, & Larson-Koester M (2017). Is there still son preference in the United States? (NBER Working Paper 23816). National Bureau of Economic Research; 10.3386/w23816 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks D, James S, & Barth RP (2002). Preferred characteristics of children in need of adoption: Is there a demand for available foster children? Social Service Review, 76(4), 575–602. [Google Scholar]

- Budiman A & Lopez MH. (2017). Amid decline in international adoptions to U.S., boys outnumber girls for the first time. PEW Research Center Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/10/17/amid-decline-in-international-adoptions-to-u-s-boys-outnumber-girls-for-the-first-time/

- Chandra A, Abma J, Maza P, & Bachrach C (1999). Adoption, adoption seeking, and relinquishment for adoption in the United States. Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics, 306 Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; Retrieved from https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/13614 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Ebenstein A, Edlund L, & Li H (2015). Girl adoption in China—A less-known side of son preference. Population Studies, 69(2), 161–178. 10.1080/00324728.2015.1009253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl GB, & Moretti E (2008). The demand for sons. The Review of Economic Studies, 75(4), 1085–1120. 10.1111/j.1467-937X.2008.00514.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, & Nelson TJ (2013). Doing the best I can: Fatherhood in the inner city Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- England P (2010). The gender revolution: Uneven and stalled. Gender & Society, 24(2), 149–166. 10.1177/0891243210361475 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher AP (2003). Still “not quite as good as having your own”? Toward a sociology of adoption. Annual Review of Sociology, 29(1), 335–361. 10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hank K, & Kohler HP (2000). Gender preferences for children in Europe: Empirical results from 17 FFS countries. Demographic Research, 2 10.4054/DemRes.2000.2.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizawa H, & Kubo K (2014). Factors affecting adoption decisions: Child and parental characteristics. Journal of Family Issues, 35(5), 627–653. 10.1177/0192513X13514408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J (2009). Who adopts?: Characteristics of women and men who have adopted children U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Lid J, Larsen U, & Wyshak G (2004). Factors affecting adoption in China, 1950–87. Population Studies, 58(1), 21–36. 10.1080/0032472032000167698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg S (2005). Sons, daughters, and parental behaviour. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 21(3), 340–356. 10.1093/oxrep/gri020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malm K, & Welti K (2010). Exploring motivations to adopt. Adoption Quarterly, 13(3–4), 185–208. 10.1080/10926755.2010.524872 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent CN (2013). Wanting mixed‐sex children: Separate spheres, rational choice, and symbolic capital motivations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(4), 886–902. 10.1111/jomf.12046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard MS, & Morgan SP (2002). Emerging parental gender indifference? Sex composition of children and the third birth. American Sociological Review, 67(4), 600–613. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raftery AE (1995). Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociological Methodology, 25, 111–163. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/271063 [Google Scholar]

- Riley NE, & Van Vleet KE (2011). Making families through adoption Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press; 10.4135/9781483349558 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggles S, Genadek K, Goeken R, Grover J, & Sobek M (2017). Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 7.0 [dataset] Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tian FF, & Morgan SP (2015). Gender composition of children and the third birth in the United States. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77(5), 1157–1165. 10.1111/jomf.12218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KJ (2016). Adoption, foreign‐born status, and children’s progress in school. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78(1), 75–90. 10.1111/jomf.12268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson NE (1976). Sons or daughters: a cross-cultural survey of parental preferences Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi B, & Morgan SP (2016). In the pursuit of sons: Additional births or sex‐selective abortion in Pakistan? Population and Development Review, 42(4), 693–710. 10.1111/padr.12002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, & Lee GR (2011). Intercountry versus transracial adoption: Analysis of adoptive parents’ motivations and preferences in adoption. Journal of Family Issues, 32(1), 75–98. 10.1177/0192513X10375410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.