Abstract

OBJECTIVES

The healthcare burden of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) in the United States has not been characterized. We previously showed that AIH disproportionately affects people of color in a single hospital system. The current study aimed to determine whether the same disparity occurs nationwide.

METHODS

We analyzed hospitalizations with a primary discharge diagnosis corresponding to the ICD-9 code for AIH in the National Inpatient Sample between 2008 and 2012. For each racial/ethnic group, we calculated the AIH hospitalization rate per 100,000 population and per 100,000 all-cause hospitalizations, then calculated a risk ratio compared to the reference rate among whites. We used multivariable logistic regression models to assess for racial disparities and to identify predictors of in-hospital mortality during AIH hospitalizations.

RESULTS

The national rate of AIH hospitalization was 0.73 hospitalizations per 100,000 population. Blacks and Latinos were hospitalized for AIH at a rate 69% (P<0.001) and 20% higher (P<0.001) than whites, respectively. After controlling for age, gender, payer, residence, zip code income, region, and cirrhosis, black race was a statistically significant predictor for mortality during AIH hospitalizations (odds ratio (OR) 2.81, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.43, 5.47).

CONCLUSIONS

Hospitalizations for AIH disproportionately affect black and Latino Americans. Black race is independently associated with higher odds of death during hospitalizations for AIH. This racial disparity may be related to biological, genetic, environmental, socioeconomic, and healthcare access and quality factors.

INTRODUCTION

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is an uncommon immune-mediated liver disorder, typically characterized by elevated transaminases and immunoglobulin levels, autoantibodies, and histologic evidence of interface hepatitis (1). The etiology of AIH is unknown, although a genetic predisposition, a dysregulated immune system, and environmental factors are thought to be involved (2). Epidemiological research has largely come from single centers in the United States and studies in racially/ethnically homogeneous countries (3–7). More information about affected populations and the healthcare burden of AIH in the United States is needed.

AIH is a disease seen in people of all races and ethnicities (8). A few retrospective, single-center studies have suggested that the clinical presentation and outcome of AIH differ by race (7,9,10). We previously reported that in our racially/ethnically diverse center, AIH cases disproportionately affected the people of color (abstract, The Liver Meeting 2015).

In order to characterize the burden of AIH on the community and on the healthcare system and to further investigate racial/ethnic disparities, we assessed hospital admissions for AIH as captured by the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). We hypothesized that the people of color are disproportionately hospitalized for AIH and suffer worse outcomes during those hospitalizations, compared to whites.

METHODS

Data source

The NIS is one of the databases developed for the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). The NIS is a database of inpatient information typically collected from discharge summaries. Data variables include patient demographics, hospital characteristics, discharge diagnoses and procedures, total charges and payment source, length of stay, and discharge status. Patient demographics, including ethnicity, are self-reported.

Prior to 2012, the NIS raw data sampled 20% of all participating US community hospitals and recorded all discharge records within those hospitals. A community hospital is defined by the American Hospital Association to be all non-Federal general, and other specialty hospitals…included are public hospitals and academic medical centers. Consequently, Veterans Affairs hospitals, Indian Health Service hospitals, and other Federal hospitals are excluded. Short-term rehabilitation hospitals, long-term non-acute care hospitals, psychiatric hospitals, and alcoholism/chemical dependency treatment facilities were also excluded. Beginning with the 2012 data, which was included in our analysis, the NIS was redesigned to systematically sample 20% of discharge records from all HCUP-participating hospitals. Under the previous sample design, in situations where certain types of conditions are concentrated in certain types of hospitals, there were considerable variation in national estimates of healthcare utilization depending on which hospitals were selected for the sample. For example, breast cancer treatment is concentrated in specialty hospitals, and estimates will vary depending on whether specialty hospitals were chosen in the 20% sample. We have to assume that AIH treatment is not concentrated in certain types of hospitals and that AIH hospitalizations from before 2012 and during 2012 are equally representative samples.

Between the sampled years 2008 and 2011, the NIS collected raw data from 42 to 46 states, 1,056 to 1,049 hospitals, and 8.2 to 8.0 million patients. The revised NIS sampled 20% of patients across all 4,500+ HCUP hospitals across 48 states. Discharge-level weights were applied to obtain national estimates. Data years are calendar years; 2008 data includes discharges from 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2008. We sample 2008–2012 data years and consequently analyzed discharges from 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2012 (11).

Data points

Each discharge record was labeled with several discharge diagnoses. The allowed number of discharge diagnoses varied by state with as few as 9 in Louisiana and as many as 61 in Indiana. We considered the first discharge diagnosis to be the primary discharge diagnosis and to be the most relevant diagnosis for the hospitalization. Prior validation studies have shown that the discharge diagnosis accurately captures the reason for hospitalization, e.g., ischemic heart disease (12), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (13), pulmonary embolism (14), primary biliary cirrhosis (15), and hepatitis B and C (16). There is also a precedence for using the primary and secondary discharge diagnosis to identify hospitalizations for constipation (17), hepatitis A (18), esophageal variceal bleeding (19), and cholangitis (20). We analyzed hospitalizations labeled with a primary discharge diagnosis of International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code 571.42 Autoimmune Hepatitis, a code instituted in 2008. Prior to 2008, AIH was coded under ICD-9 code 571.49 Chronic Hepatitis, which included active chronic hepatitis, fibrous, hypertrophic, interstitial, lupoid, plasma cell, post-necrotic, recurrent, and Waldenstrom’s hepatitis. In order to analyze a larger sample of AIH-related hospitalizations for the mortality analysis, we analyzed hospitalizations labeled with the ICD-9 code for AIH as one of its top five discharge diagnoses.

Data period

For our cross-sectional analysis of demographics, hospital course, and mortality, we analyzed the 2008–2012 hospitalizations with a primary discharge diagnosis of 571.42. The number of AIH hospitalizations rapidly increased from 2008 to 2010 potentially due to adoption of the new code, rather than an actual increase in incidence or prevalence. As a result, for our analysis of hospitalization rate, we excluded 2008 and 2009 and only analyzed 2010–2012 hospitalizations with a primary discharge diagnosis of 571.42.

Data variables

We included the following variables in our analysis: age, gender, race/ethnicity, median income for patient’s zip code of residence, payer/insurance, metro/micropolitan residence, and United States region. Age was categorized into six groups (<20, 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, >60) for the chi-square analysis and as a continuous variable for the logistic regression. Racial/ethnic groups included white, black, Latino, Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American, and other. Metropolitan residence was defined as a county with a population greater than 50,000 and was stratified into four categories (central counties with a population more than one million, akin to “inner cities”; fringe counties with a population more than one million, akin to “suburbs”; counties with a population <1 million but >250,000; and counties with a population <250,000 but >50,000); micropolitan residence was defined as a county with a population <50,000. The course of each hospitalization for AIH was assessed using up to four diagnoses listed after the primary discharge diagnosis and the first five procedures.

Analysis

Demographics: In the bivariate analysis of AIH and non-AIH hospitalizations, we compared demographic and hospital characteristics using the χ2-test for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables. Hospital course: We compared clinical presentation, length of stay, and mortality rate of AIH hospitalizations between the different races/ethnicities. Hospitalization rate: We calculated the rate of AIH hospitalizations and the rate of all-cause hospitalizations per 100,000 persons by dividing the 3-year total number of race-specific AIH and all-cause hospitalizations by the 3-year total race-specific population during 2010–2012. Race-specific populations were obtained from the US Census Bureau (https://www.census.gov/topics/population/data.html). We reported risk ratios for each race as compared to whites as reference. We also calculated the race-specific rate of AIH hospitalization per 100,000 hospitalizations by dividing the 3-year total number of AIH hospitalizations by the three-year total number of hospitalizations during 2010–2012. Predictors of AIH Hospitalization: We used a multivariable logistic regression model to evaluate the relationship between race/ethnicity and hospitalization for AIH (vs. non-AIH diagnoses) while adjusting for age, sex, payer, income, community size, and region. Predictors of AIH in-hospital mortality: We used a multivariable logistic regression model to assess for racial/ethnic differences in in-hospital mortality while adjusting for the above variables plus cirrhosis. We also performed a sensitivity analysis of AIH-related hospitalizations, in which AIH appears anywhere within the top five discharge diagnoses, as opposed to only the first discharge diagnosis. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA Statistical Software: Release 13.0, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA. This study relies on public, de-identified data and does not constitute research involving human subjects; it complies with Title 45 of the USCode of Federal Regulations. As such, it was exempt from the Institutional Review Board approval.

RESULTS

The National Inpatient Sample data from 2008 to 2012 captured 1,933 hospitalizations with a primary discharge diagnosis of AIH. Using the sampling weights provided by HCUP, this represents 9,258 (95% confidence interval (CI), 8,471–10,044) AIH hospitalizations during the study period.

Patient demographics

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of this weighted sample of AIH hospitalizations. The median age was 53 years (interquartile range 28–72). Whites constituted 57%, followed by Latinos (19%), blacks (18%), and Asian/Pacific Islander (2%). Private insurance (including HMO) was the primary payment source (41%). The South contributed the largest portion of AIH hospitalizations (39%).The majority of the discharges (84%) were from metropolitan counties. Table 1 shows that the racial/ethnic distribution of AIH hospitalizations differed significantly from that of non-AIH hospitalizations (p<0.01).

Table 1.

Characteristics of AIH hospitalizations compared to non-AIH hospitalizations

| Characteristics | Hospitalizations with a primary discharge diagnosis of AIH | Hospitalizations with a primary discharge diagnosis other than AIH | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=9,258 | % | N=186,735,489 | % | ||

| Age, year | <0.01 | ||||

| <20 | 974 | 10.5% | 31,934,862 | 17.1% | |

| 20–29 | 1,033 | 11.2% | 18,398,533 | 9.9% | |

| 30–39 | 1,129 | 12.2% | 17,664,332 | 9.5% | |

| 40–49 | 1,307 | 14.1% | 17,503,655 | 9.4% | |

| 50–59 | 1,934 | 20.9% | 23,736,255 | 12.7% | |

| >60 | 2,871 | 31.0% | 77,306,352 | 41.4% | |

| Gender | <0.01 | ||||

| Male | 1,781 | 19.3% | 78,242,252 | 42.0% | |

| Female | 7,462 | 80.7% | 108,122,937 | 58.0% | |

| Race | <0.01 | ||||

| White | 4,666 | 57.0% | 108,128,364 | 66.3% | |

| Black | 1,463 | 17.9% | 23,671,609 | 14.5% | |

| Latino | 1,556 | 19.0% | 19,985,467 | 12.2% | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 142 | 1.7% | 4,348,503 | 2.7% | |

| Native American | 39 | 0.5% | 1,186,948 | 0.7% | |

| Other | 323 | 3.9% | 5,869,158 | 3.6% | |

| Payer | <0.01 | ||||

| Medicare | 2,467 | 26.7% | 71,033,950 | 38.1% | |

| Medicaid | 1,700 | 18.4% | 37,604,643 | 20.2% | |

| Private | 3,757 | 40.7% | 60,844,996 | 32.7% | |

| Self-pay | 780 | 8.4% | 9,680,626 | 5.2% | |

| No charge | 107 | 1.2% | 934,676 | 0.5% | |

| Other | 431 | 4.7% | 6,212,517 | 3.3% | |

| Residence | 0.07 | ||||

| Central metro >1 mil | 3,141 | 34.2% | 55,322,790 | 30.3% | |

| Fringe metro >1 mil | 2,109 | 22.9% | 43,674,800 | 23.9% | |

| Metro 250 K–1 mil | 1,643 | 17.9% | 33,711,890 | 18.5% | |

| Metro 50–250 K | 778 | 8.5% | 16,363,307 | 9.0% | |

| Micropolitan | 931 | 10.1% | 20,254,333 | 11.1% | |

| Not metro or micro | 588 | 6.4% | 13,342,430 | 7.3% | |

| Zip code income | 0.23 | ||||

| Bottom quartile | 2,614 | 28.7% | 53,066,594 | 29.1% | |

| Second quartile | 2,550 | 28.0% | 47,129,097 | 25.9% | |

| Third quartile | 2,041 | 22.4% | 43,601,863 | 23.9% | |

| Top quartile | 1,899 | 20.9% | 38,425,941 | 21.1% | |

| Region | 0.72 | ||||

| East | 1,694 | 18.3% | 35,983,085 | 19.3% | |

| Midwest | 2,025 | 21.9% | 42,493,242 | 22.8% | |

| South | 3,581 | 38.7% | 71,512,373 | 38.3% | |

| West | 1,959 | 21.2% | 36,746,789 | 19.7% | |

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis.

Rates of hospitalization for AIH

The average annual rate of hospitalization in 2010–2012 for AIH among all individuals in the U.S. census was 0.73 per 100,000 population. AIH hospitalization burden on national race-specific population: Blacks were hospitalized for AIH at a 69% higher rate (95% CI, 1.58–1.81) compared to whites, and Latinos at a 20% higher rate (95% CI, 1.12–1.28). Asians and Pacific Islanders were hospitalized at a rate 64% lower than whites (95% CI, 0.29–0.43; Table 2a). Hospitalization burden on national race-specific population: To evaluate whether this disparity reflected a differential hospital utilization for any indications, i.e., AIH and non-AIH; we calculated an all-cause hospitalization rate per 100,000 population for each race. Compared to whites, blacks were hospitalized at a rate 19% higher (95% CI, 1.189–1.190), Latinos 29% lower (95% CI, 0.708–0.709), and Asians and Pacific Islanders 50% lower (95% CI, 0.497–0.498; Table 2b). AIH hospitalization contribution to total race-specific healthcare utilization: We calculated the AIH hospitalization rate per 100,000 all-cause hospitalizations and found that blacks were hospitalized for AIH at a rate 42% higher than whites (95% CI, 1.33–1.52) and Latinos 69% higher (95% CI, 1.58–1.81) relative to the number of all-cause hospitalizations. Asians and Pacific Islanders were hospitalized at a rate 29% lower than whites (95% CI, 0.58–0.87; Table 2c).

Table 2A.

AIH hospitalization rate per 100,000 race-specific population, 2010–2012

| White | Black | Latino | API | Alla | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | |||||

| AIH hospitalizations | 1,134 | 398 | 382 | 34 | 2,248 |

| National population | 197,318,956 | 37,922,522 | 50,477,594 | 15,158,732 | 308,745,538 |

| 2011 | |||||

| AIH hospitalizations | 1218 | 387 | 383 | 20 | 2,385 |

| National population | 197,529,690 | 38,364,773 | 51,881,267 | 15698443 | 308,758,105 |

| 2012 | |||||

| AIH hospitalizations | 1,175 | 375 | 345 | 45 | 2,160 |

| National population | 197,705,655 | 38,727,063 | 53,027,708 | 16140684 | 309,347,057 |

| 2010–2012 | |||||

| 3-Year total AIH hospitalizations | 3,526 | 1,159 | 1,110 | 99 | 6,792 |

| 3-Year total population | 592,554,301 | 115,014,358 | 155,386,569 | 46,997,859 | 926,850,700 |

| AIH hospitalization rate (per 100,000) | 0.60 | 1.01 | 0.71 | 0.21 | 0.73 |

| Relative risk ratio | REF | 1.69 | 1.20 | 0.36 | 1.23 |

| 95% CI | REF | 1.58–1.81 | 1.12–1.28 | 0.29–0.43 |

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; CI, confidence interval.

All includes self-reported race “Other” and discharges for which race information was not available.

Table 2B.

All-cause hospitalization rate per 100,000 race-specific population, 2010–2012

| White | Black | Latino | API | Alla | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | |||||

| Hospitalizations | 21,616,106 | 5,261,207 | 4,086,156 | 880,131 | 33,117,915 |

| National population | 197,318,956 | 37,922,522 | 50,477,594 | 15,158,732 | 308,745,538 |

| 2011 | |||||

| Hospitalizations | 21,977,732 | 4,989,477 | 4,160,276 | 804,366 | 33,266,802 |

| National population | 197,529,690 | 38,364,773 | 51,881,267 | 15698443 | 308,758,105 |

| 2012 | |||||

| Hospitalizations | 22,759,225 | 5,073,490 | 4,076,682 | 933,061 | 34,392,488 |

| National population | 197,705,655 | 38,727,063 | 53,027,708 | 16140684 | 309,347,057 |

| 2010–2012 | |||||

| 3-Year total all-cause hospitalizations | 66,353,062 | 15,324,174 | 12,323,115 | 2,617,557 | 100,777,205 |

| 3-Year total population | 592,554,301 | 115,014,358 | 155,386,569 | 46,997,859 | 926,850,700 |

| All-cause hospitalization rate (per 100,000) | 11197.80 | 13323.71 | 7930.62 | 5569.52 | 10873.08 |

| Relative risk ratio | REF | 1.19 | 0.71 | 0.50 | 0.97 |

| 95% CI | REF | 1.189–1.190 | 0.708–0.709 | 0.497–0.498 |

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; CI, confidence interval.

All includes self-reported race “Other” and discharges for which race information was not available.

Table 2C.

AIH hospitalization rate per 100,000 all-cause hospitalizations, 2010–2012

| White | Black | Latino | API | Alla | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | |||||

| AIH hospitalizations | 1134 | 398 | 382 | 34 | 2248 |

| Total hospitalizations | 21,616,106 | 5,261,207 | 4,086,156 | 880,131 | 33,117,915 |

| 2011 | |||||

| AIH hospitalizations | 1,218 | 387 | 383 | 20 | 2,385 |

| Total hospitalizations | 21,977,732 | 4,989,477 | 4,160,276 | 804,366 | 33,266,802 |

| 2012 | |||||

| AIH hospitalizations | 1175 | 375 | 345 | 45 | 2160 |

| Total hospitalizations | 22,759,225 | 5,073,490 | 4,076,682 | 933,061 | 34,392,488 |

| 2010–2012 | |||||

| 3-year total AIH hospitalizations | 3,526 | 1,159 | 1,110 | 99 | 6,792 |

| 3-year total all-cause hospitalizations | 66,353,062 | 15,324,174 | 12,323,115 | 2,617,557 | 100,777,205 |

| AIH hospitalization rate (per 100,000 Hospitalizations) | 5.31 | 7.56 | 9.00 | 3.80 | 6.74 |

| Relative risk ratio | REF | 1.42 | 1.69 | 0.71 | 1.27 |

| 95% CI | REF | 1.33–1.52 | 1.58–1.81 | 0.58–0.87 |

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; API, Asian Pacific islander; CI, confidence interval.

All includes self-reported race “Other” and discharges for which race information was not available.

Predictors of AIH vs. non-AIH hospitalization

We assessed the effect of individual and community factors on hospitalization for AIH vs. for non-AIH primary diagnoses (Table 3). After controlling for all variables listed, race, gender, insurance status, and community income were associated with an AIH discharge diagnosis. Patients hospitalized for AIH were more likely to be black (odds ratio (OR) 1.49, 95% CI 1.28, 1.75); Latino (OR 1.83, 95% CI 1.54, 2.16); female (OR 3.09, 95% CI 2.69, 3.56); older (OR 1.01, 95% CI 1.005, 1.011); covered by non-Medicare or Medicaid insurance; and in the second lowest quartile for median income by zip code (OR 1.20, 95% CI 1.04, 1.38). There was no statistically significant association with the metropolitan/micropolitan residence or geographic region of participants.

Table 3.

Predictors of Hospitalization for a primary discharge diagnosis of AIH vs. non-AIH

| Factor | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Age, yr | ||||

| Age (1 yr) | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | <0.01 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | REF | |||

| Female | 3.09 | 2.69 | 3.56 | <0.01 |

| Race | ||||

| White | REF | |||

| Black | 1.49 | 1.28 | 1.75 | <0.01 |

| Latino | 1.83 | 1.54 | 2.16 | <0.01 |

| Asian/Pacific islander | 0.62 | 0.42 | 0.92 | 0.02 |

| Native American | 0.71 | 0.33 | 1.52 | 0.38 |

| Other | 1.23 | 0.91 | 1.67 | 0.18 |

| Payer | ||||

| Medicare | REF | |||

| Medicaid | 1.49 | 1.2 | 1.84 | <0.01 |

| Private | 2.39 | 1.95 | 2.71 | <0.01 |

| Self-pay | 3.14 | 2.4 | 4.11 | <0.01 |

| No charge | 4.46 | 2.44 | 8.15 | <0.01 |

| Other | 2.84 | 2.14 | 3.77 | <0.01 |

| Residence | ||||

| Central metro >1 mil | REF | |||

| Fringe metro >1 mil | 0.91 | 0.77 | 1.07 | 0.25 |

| Metro 250 K–1 mil | 0.93 | 0.77 | 1.11 | 0.40 |

| Metro 50–250 K | 0.98 | 0.79 | 1.22 | 0.87 |

| Micropolitan | 1.05 | 0.83 | 1.32 | 0.68 |

| Not metro or micropolitan | 0.99 | 0.75 | 1.3 | 0.94 |

| Zip code income | ||||

| Bottom quartile | REF | |||

| Second quartile | 1.20 | 1.04 | 1.38 | 0.01 |

| Third quartile | 1.05 | 0.89 | 1.23 | 0.53 |

| Top quartile | 1.13 | 0.96 | 1.35 | 0.14 |

| Region | ||||

| East | REF | |||

| Midwest | 0.95 | 0.74 | 1.22 | 0.68 |

| South | 0.96 | 0.79 | 1.16 | 0.65 |

| West | 1.00 | 0.79 | 1.27 | 1.00 |

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; yr, year.

Hospital course/presentation

Table 4 describes the hospitalizations with a primary discharge diagnosis of AIH in terms of concomitant conditions, procedures, length of stay, and mortality. At least one complication associated with decompensated cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma occurred in 36% of AIH hospitalizations. The two most common complications were ascites (16% of AIH hospitalizations) and hepatic encephalopathy (10% of AIH hospitalizations). At least one complication occurred in 38% of white, 30% of black, 38% of Latino, 17% of Asian, and 23% of native american AIH hospitalizations. At least one concomitant autoimmune disorder occurred in 11% AIH hospitalizations. Lupus was the most common, included on 3% of AIH hospitalizations, followed by primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) or primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) at 2%. Hepatitis C was present in 1% of AIH hospitalizations.

Table 4.

Hospital course of AIH hospitalizations by Race 2008–2012

| Clinical variables | White | Black | Latino | API | Nat. Am. | Other | Total | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=4,666) | (N=1,463) | (N=1,556) | (N=142) | (N=39) | (N=323) | (N=9,257) | ||

| Complications | ||||||||

| Cirrhosis | 15.14% | 12.46% | 19.11% | 13.13% | 0.00% | 19.35% | 15.47% | 0.23 |

| Ascites | 18.54% | 10.71% | 14.59% | 9.31% | 0.00% | 13.39% | 15.94% | 0.02 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 10.58% | 8.28% | 9.48% | 3.52% | 23.18% | 14.42% | 10.05% | 0.35 |

| Variceal bleed | 4.20% | 2.40% | 2.51% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 3.04% | 3.42% | 0.45 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 0.74% | 0.34% | 0.64% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.61% | 0.94 |

| Any above complications | 37.54% | 29.68% | 38.48% | 16.65% | 23.18% | 41.28% | 36.03% | 0.03 |

| Comorbidity | ||||||||

| Autoimmune thyroid disease | 0.64% | 0.00% | 0.33% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.43% | 0.77 |

| Type 1 diabetes | 0.31% | 0.00% | 0.35% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.24% | 0.95 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1.13% | 1.04% | 0.35% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 1.37% | 0.95% | 0.85 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 1.42% | 0.65% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.92% | 0.35 |

| Crohn’s Disease | 1.26% | 0.64% | 0.63% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.95% | 0.78 |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 2.01% | 1.58% | 0.62% | 3.34% | 0.00% | 2.70% | 1.71% | 0.58 |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 1.57% | 1.35% | 1.43% | 3.52% | 12.97% | 2.75% | 1.64% | 0.17 |

| Systemic erythematosus lupus | 2.66% | 3.64% | 3.42% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 4.78% | 3.00% | 0.77 |

| Hepatitis C Virus | 1.38% | 1.89% | 0.90% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 2.90% | 1.41% | 0.74 |

| HIV/AIDS | 0.00% | 1.38% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.25% | 0.03 |

| Any above comorbidity | 11.50% | 11.88% | 8.02% | 6.86% | 12.97% | 14.50% | 10.95% | 0.46 |

| In-hospital procedures | ||||||||

| Closed biopsy | 28.30% | 28.86% | 24.64% | 17.92% | 12.97% | 37.52% | 27.81% | 0.23 |

| Transjugular liver biopsy | 4.61% | 5.66% | 8.10% | 3.52% | 0.00% | 7.27% | 5.52% | 0.26 |

| Abdominal drainage | 14.17% | 8.82% | 14.94% | 6.60% | 0.00% | 15.71% | 13.23% | 0.13 |

| Endoscopy | 7.62% | 4.02% | 9.62% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 7.48% | 7.18% | 0.06 |

| Liver Transplant | 5.58% | 4.31% | 2.50% | 3.52% | 0.00% | 4.25% | 4.65% | 0.32 |

| Any above procedure | 54.66% | 48.63% | 53.01% | 31.56% | 12.97% | 61.92% | 52.96% | 0.01 |

| Length of stay | ||||||||

| Average length of stay, days | 7.01 | 7.52 | 7.17 | 5.47 | 8.19 | 6.59 | 6.94 | 0.59 |

| In-hospital mortality | ||||||||

| Mortality % | 3.29% | 5.65% | 4.59% | 0.00% | 11.58% | 1.54% | 4.18% | 0.23 |

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; API, Asian Pacific islander.

A majority (53%) of AIH hospitalizations included at least one procedure. Percutaneous liver biopsy (28% of AIH hospitalizations) and paracentesis (13% of AIH hospitalizations) were the most common procedures. The average length of stay was 7 days.

The overall mortality of AIH hospitalizations was 4.2%. The unadjusted in-hospital mortality rate was 3.3% for white AIH hospitalizations, 5.7% for black, 4.6% for Latino, 0% for API, 11.58% for Native Americans (P=0.23).

Predictors of mortality

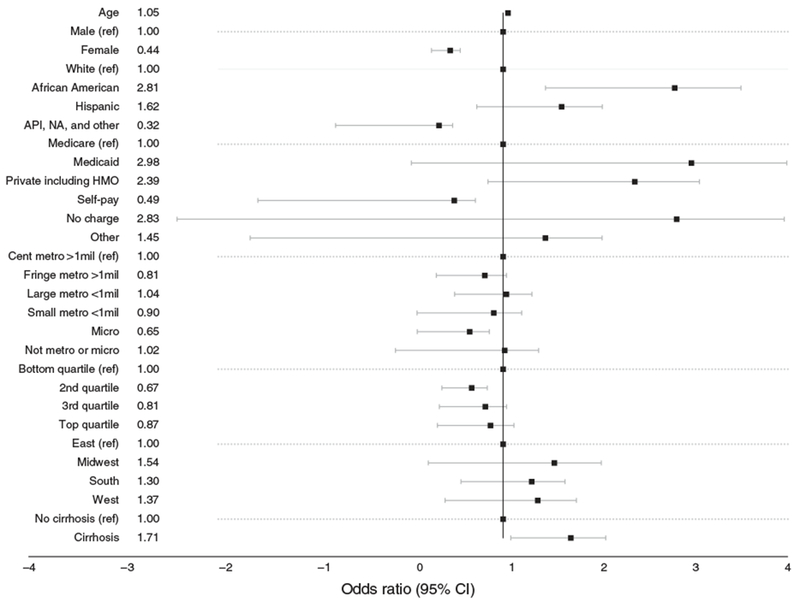

The results of a multivariable logistic regression model of mortality during hospitalizations for AIH are shown in Table 5 and Figure 1. Among AIH hospitalizations, black race increased the odds of mortality (OR 2.81, 95% CI 1.43, 5.47) after controlling for age, gender, payer, residence, zip code income, hospital region, and cirrhosis.

Table 5.

Predictors of mortality during AIH hospitalizations

| Factor | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Age, yr | ||||

| Age | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.07 | <0.01 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | REF | |||

| Female | 0.44 | 0.24 | 0.83 | 0.01 |

| Race | ||||

| White | REF | |||

| Black | 2.81 | 1.44 | 5.48 | <0.01 |

| Latino | 1.62 | 0.78 | 3.37 | 0.20 |

| API, NA, and other | 0.32 | 0.04 | 2.46 | 0.28 |

| Payer | ||||

| Medicare | REF | |||

| Medicaid | 2.98 | 1.02 | 8.77 | 0.05 |

| Private including HMO | 2.39 | 1.05 | 5.42 | 0.04 |

| Self-pay | 0.49 | 0.05 | 4.54 | 0.53 |

| No charge | 2.83 | 0.61 | 13.15 | 0.19 |

| Other | 1.45 | 0.28 | 7.54 | 0.66 |

| Residence | ||||

| Central metro >1 mil | REF | |||

| Fringe metro >1 mil | 0.81 | 0.36 | 1.81 | 0.60 |

| Metro 250 K–1 mil | 1.04 | 0.51 | 2.10 | 0.92 |

| Metro 50–250 K | 0.90 | 0.33 | 2.49 | 0.84 |

| Micropolitan | 0.65 | 0.24 | 1.73 | 0.39 |

| Not metro or micropolitan | 1.02 | 0.32 | 3.27 | 0.98 |

| Zip code income | ||||

| Bottom quartile | REF | |||

| 2nd quartile | 0.67 | 0.35 | 1.29 | 0.23 |

| 3rd quartile | 0.81 | 0.37 | 1.76 | 0.60 |

| Top quartile | 0.87 | 0.38 | 1.96 | 0.73 |

| Region | ||||

| East | REF | |||

| Midwest | 1.54 | 0.57 | 4.14 | 0.39 |

| South | 1.30 | 0.61 | 2.76 | 0.49 |

| West | 1.37 | 0.57 | 3.28 | 0.49 |

| Cirrhosis | ||||

| No cirrhosis | REF | |||

| Cirrhosis | 1.71 | 0.99 | 2.95 | 0.05 |

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; API, Asian Pacific islander; NA, Native American; yr, year.

Figure 1.

Multivariable logistic regression for predictors of mortality during AIH hospitalizations.

In the broadened sensitivity analysis of all AIH-related hospitalizations, for which AIH appeared anywhere in the top five discharge diagnoses, black race was still an independent predictor of mortality (OR 2.60, 95% CI 1.51, 44.7) after controlling for the above factors (Table 6).

Table 6.

Predictors of mortality during AIH-related hospitalizations

| Factor | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Age, yr | ||||

| Age | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.07 | <0.01 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | REF | |||

| Female | 0.48 | 0.31 | 0.75 | <0.01 |

| Race | ||||

| White | REF | |||

| Black | 2.60 | 1.51 | 4.47 | <0.01 |

| Latino | 1.43 | 0.78 | 2.62 | 0.25 |

| API, NA, and other | 0.50 | 0.16 | 1.55 | 0.23 |

| Payer | ||||

| Medicare | REF | |||

| Medicaid | 2.88 | 1.35 | 6.14 | 0.01 |

| Private including HMO | 1.97 | 1.12 | 3.47 | 0.02 |

| Self-pay | 3.41 | 1.25 | 9.31 | 0.02 |

| No charge | 3.75 | 0.67 | 21.07 | 0.13 |

| Other | 1.87 | 0.53 | 6.56 | 0.33 |

| Residence | ||||

| Central metro >1 mil | REF | |||

| Fringe metro >1 mil | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.54 | 1.79 |

| Metro 250 K–1 mil | 1.07 | 0.81 | 0.60 | 1.94 |

| Metro 50–250 K | 2.04 | 0.03 | 1.09 | 3.81 |

| Micropolitan | 1.02 | 0.97 | 0.48 | 2.13 |

| Not metro or micropolitan | 0.78 | 0.65 | 0.27 | 2.27 |

| Zip code income | ||||

| Bottom quartile | REF | |||

| 2nd quartile | 0.75 | 0.44 | 1.27 | 0.28 |

| 3rd quartile | 0.89 | 0.50 | 1.59 | 0.69 |

| Top quartile | 0.74 | 0.38 | 1.44 | 0.38 |

| Region | ||||

| East | REF | |||

| Midwest | 0.96 | 0.44 | 2.07 | 0.91 |

| South | 0.95 | 0.53 | 1.68 | 0.85 |

| West | 2.20 | 1.28 | 3.78 | <0.01 |

| Cirrhosis | ||||

| No cirrhosis | REF | |||

| Cirrhosis | 2.02 | 1.34 | 3.05 | <0.01 |

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; API, Asian Pacific islander; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; yr, year.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that AIH hospitalizations disproportionately affect black and Latino Americans. Furthermore black race is an independent predictor of mortality during these hospitalizations.

Our finding that the average annual hospitalization rate 2010–2012 for AIH is 0.73 per 100,000 in the United States is comparable to AIH hospitalization rates published elsewhere. A tertiary care referral center in Spain reported 0.8 cases per 100,000 and a secondary care referral center in the United Kingdom reported 3.0 cases per 100,000 (refs 21,22). By comparison, other studies using the NIS data set reported hospitalization rates of 0.29 per 100,000 for hepatitis A; 13.81 per 100,000 for hepatitis C; and 99 per 100,000 for hepatocellular carcinoma (18,23,24).

Prior studies have already suggested that ethnicity is an important factor in the presentation, disease course, and outcome of AIH. Our group previously reported single-center findings that blacks and Latinos composed a percentage of the AIH hospitalization population that is disproportionate to the racial profile of the all-cause hospitalization population. Our study’s hospitalization rate and mortality findings further support this emerging trend.

The absolute number of AIH hospitalizations was higher among whites than the absolute number of AIH hospitalizations among blacks or Latinos, 3,526 compared to 1,159 and 1,110, respectively. However, after controlling for the different race-specific population sizes and the larger white population, the rate of AIH hospitalization was higher among blacks and Latinos as compared to whites, 1.01 and 0.71 as compared to 0.6 AIH hospitalizations per 100,000 race-specific population, respectively. The absolute rate differences are small, but the relative risk ratios are statistically significant and represent a troubling racial disparity on a national scale.

This disparity could reflect at least two alternative scenarios: (i) Blacks and Latinos utilize healthcare resources and hospitalizations for all diseases, not only for AIH, at a higher rate compared to whites. However, we found that the all-cause hospitalization rate for blacks was only 19% (95% CI 1.189–1.190) higher than whites. This difference is too small to account for the 69% (95% CI 1.58–1.81) difference in the black vs. white AIH hospitalization rate. Furthermore, the all-cause hospitalization rate for Latinos was 29% (95% CI 0.708–0.709) lower than whites, disproving this scenario. The disproportionate AIH hospitalization rate among blacks and Latinos cannot be explained simply by a higher level of healthcare utilization by these two racial communities. (ii) AIH is more prevalent among blacks and Latinos. The AIH hospitalization rate per population is a reflection of two more specific rates: AIH prevalence in the population and the AIH hospitalization rate among patients with AIH. The NIS only includes cases of AIH that required hospitalization. Consequently, we did not have data on the non-hospitalized AIH population and could not quantify the complete AIH population. As a result, we are unable to determine whether there is a disparity in AIH prevalence. However, our study shows that, at some level, black and Latino communities bear a greater burden of AIH hospitalizations. Combined with our finding that AIH contributed to a higher proportion of all-cause hospitalizations among the race-specific black and Latino population as compared to the white population, more resources are needed to manage AIH for these two communities.

There was no statistically significant difference in the AIH in-hospital mortality rate by race. However, after adjusting for covariates with a multivariable model, black race significantly increased the odds of mortality both in hospitalizations with AIH as a primary diagnosis and as a related diagnosis. While we controlled for gender, race, payer, residence, zip code income, region, and the presence of cirrhosis, the small number of AIH in-hospital fatalities limited the number of variables that could be included in the multivariable regression. With a larger sample and larger number of AIH fatalities, we would have included the size and teaching status of the hospital, liver complications, and other concomitant comorbidities. We decided not to remark on the in-hospital mortality rate observed in API or Native Americans due to the small number of AIH hospitalizations for these two racial groups.

Prior studies have suggested potential biological and socioeconomic factors driving these disparities. Prior reports have shown that blacks and Latinos experience more advanced fibrosis associated with AIH, suggesting a predisposition for more aggressive disease progression (4,5). In a single tertiary-care community hospital, Wong et al. (7) found biopsy-confirmed cirrhosis in 55% of Latino AIH patients compared to 30% of whites and 29% of Asians. In a retrospective single-center 10-year analysis, Verma et al. (10) found that black AIH patients were more likely to present with cirrhosis and liver failure and suffered higher mortality rates compared to non-blacks.

Genetic and pharmacogenomic differences may also affect treatment response and disease progression. The metabolism of prednisone is dependent on cytochrome P450 3A4 and P-glycoprotein transporter. Polymorphisms that affect the expression or function of the cytochrome P450 3A4 or P-glycoprotein can affect the drug concentration, remission with therapy, and need for hospitalization. The different prevalence of specific polymorphisms among the races may contribute to the disproportionate hospitalization rates.

Differences in the access and quality of care may delay diagnosis and result in inadequate or escalation of immunosuppressive therapy and suboptimal management of AIH in blacks and Latinos. Kim et al. (25) showed that patients with consistent access to primary care prior to diagnosis of AIH had better transplant-free overall survival than those without. Echkoff et al. (26) found that black patients were referred for liver transplantation at later stages of end-stage liver compared to white patients. Nguyen et al. (27) found that blacks and Latinos hospitalized for complications of portal hypertension were less likely to undergo a palliative shunt or liver transplant than whites. While data about primary care access and disease stage is unavailable in the NIS, differences in care and implicit bias may contribute to the racial disparities we identified (28).

Prior research studies on race and AIH have largely been retrospective case series with no information on socioeconomic status. Since race may be a confounder in the relationship between socioeconomic status and disease outcomes, the current study was able to account for some aspects of socioeconomic status with the NIS variables. Adjusting for the median income of the patient’s zip code of residence and insurance/payer, as well as urban or rural residence, our analysis still found race/ethnicity to be significantly associated with hospitalization for AIH and death during an AIH hospitalization. Other socioeconomic measures such as education or occupation were not available.

The present analyses of the NIS data set have limitations. AIH only received a specific ICD-9 code in 2008, making hospitalizations for AIH prior to 2008 difficult to identify. Hospitalizations in 2008 may have been underestimated as providers transitioned to the new coding. Recognizing this limitation, we did not attempt to assess trends in AIH hospitalization over time. A major limitation of the NIS is the lack of personal identification codes in the discharge records. This meant the NIS data could not track individual patients across time or settings and a single individual could have been hospitalized multiple times for AIH. Therefore, we cannot say if black and Latino individuals with AIH are hospitalized more often than white Americans. Therapy information was also unavailable and differences reflecting inadequate initiation or escalation of immunosuppression will need further study.

Despite the limitations of the NIS data set, these results are a major contribution to our understanding of AIH in the United States. Blacks and Latinos have a higher hospitalization rate for AIH than whites, and correcting for covariates, black race increases the odds of in-hospital mortality during hospitalizations for AIH. Disparities in healthcare utilization and outcomes of AIH exist on a national scale. Future studies should further elucidate the reasons behind these racial disparities in order to design targeted interventions, particularly as the number of people of color in the United States grows.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS CURRENT KNOWLEDGE

Single-center studies have suggested that autoimmune hepatitis may disproportionately affect the people of color.

WHAT IS NEW HERE

In the United States, blacks and Latinos are hospitalized for autoimmune hepatitis at a higher rate as compared to whites.

Even after controlling for socioeconomic factors, black race increases the odds of in-hospital mortality during hospitalizations for autoimmune hepatitis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Janet Coffman.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Guarantor of the article: Michele M. Tana, MD.

Specific author contributions: Jason Wen: analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, statistical analysis. Michael A. Kohn: critical revision of manuscript and statistical analysis.

Robert Wong: critical revision of manuscript and statistical analysis. Ma Somsouk: critical revision of manuscript and statistical analysis. Mandana Khalili: critical revision of manuscript and statistical analysis. Jacquelyn Maher: critical revision of manuscript and statistical analysis. Michele Tana: study concept and design, acquisition of data, critical revision of manuscript and statistical analysis, study supervision.

Financial support: This work was supported in part by the UCSF Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (UL1 TR991872) and the UCSF Liver Center (P30 DK026743).

Potential competing interests: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB et al. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol 1999;31:929–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Czaja AJ, Manns MP Advances in the diagnosis, pathogenesis, and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Gastroenterology 2010;139:58–72.e54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gronbaek L, Vilstrup H, Jepsen P Autoimmune hepatitis in Denmark: incidence, prevalence, prognosis, and causes of death. A nationwide registry-based cohort study. J Hepatol 2014;60:612–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim KN, Casanova RL, Boyer TD et al. Autoimmune hepatitis in African Americans: presenting features and response to therapy. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:3390–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munoz-Espinosa LE, Cordero-Perez P, Cura-Esquivel I et al. Autoimmune hepatitis in Mexican patients. J Clin Gastroenterol 2013;47:372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zolfino T, Heneghan MA, Norris S et al. Characteristics of autoimmune hepatitis in patients who are not of European Caucasoid ethnic origin. Gut 2002;50:713–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong RJ, Gish R, Frederick T et al. The impact of race/ethnicity on the clinical epidemiology of autoimmune hepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2012;46:155–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czaja AJ. Challenges in the diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis . Can J Gastroenterol 2013. ; 27 : 531–9 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minuk GY, Liu S, Kaita K et al. Autoimmune hepatitis in a North American Aboriginal/First Nations population. Can J Gastroenterol 2008. ;22:829–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verma S, Torbenson M, Thuluvath PJ. The impact of ethnicity on the natural history of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology 2007;46:1828–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Houchens R, Ross D, Elixhauser A et al. Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) Redesign Final Report. 2014. HCUP Methods Series Report # 2014–04 ONLINE. April 4, 2014 U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality : Available at http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/methods/methods.jsp

- 12.Rawson NS, Malcolm E . Validity of the recording of ischaemic heart disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the Saskatchewan health care datafiles. Stat Med 1995;14:2627–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazumdar S, Colbus DS, Townsend MC. Validation of hospital discharge diagnosis data for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and other allied conditions. Am J Public Health 1986;76:803–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casez P, Labarere J, Sevestre MA et al. ICD-10 hospital discharge diagnosis codes were sensitive for identifying pulmonary embolism but not deep vein thrombosis . J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:790–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Myers RP, Shaheen AAM, Fong A et al. Validation of coding algorithms for the identification of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis using administrative data. Can J Gastroenterol 2010;24:175–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niu B, Forde KA, Goldberg DS. Coding algorithms for identifying patients with cirrhosis and hepatitis B or C virus using administrative data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2015;24:107–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sethi S, Mikami S, Leclair J et al. Inpatient burden of constipation in the United States: an analysis of national trends in the United States from 1997 to 2010. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:250–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collier MG, Tong X, Xu F. Hepatitis A hospitalizations in the United States, 2002–2011. Hepatology 2015;61:481–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Njei B, McCarty TR, Laine L. Early transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in US patients hospitalized with acute esophageal variceal bleeding. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;32:852–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inamdar S, Sejpal DV, Ullah M et al. Weekend vs. weekday admissions for cholangitis requiring an ERCP: comparison of outcomes in a National Cohort. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:405–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Primo J, Merino C, Fernandez J et al. Incidence and prevalence of autoimmune hepatitis in the area of the Hospital de Sagunto (Spain). Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;27:239–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whalley S, Puvanachandra P, Desai A et al. Hepatology outpatient service provision in secondary care: a study of liver disease incidence and resource costs. Clin Med 2007;7:119–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu FJ, Tong X, Leidner AJ. Hospitalizations And costs associated with hepatitis C and advanced liver disease continue to increase. Health Affairs 2014;33:1728–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mishra A, Otgonsuren M, Venkatesan C et al. The inpatient economic and mortality impact of hepatocellular carcinoma from 2005 to 2009: analysis of the US nationwide inpatient sample. Liver Int 2013;33: 1281–6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim D, Eshtiaghpour D, Alpern J et al. Access to primary care is associated with better autoimmune hepatitis outcomes in an urban county hospital. BMC Gastroenterol 2015;15:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eckhoff DE, McGuire BM, Young CJ et al. Race: a critical factor in organ donation, patient referral and selection, and orthotopic liver transplantation? Liver Transplant Surg 1998;4:499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen GC, Segev DL, Thuluvath PJ. Racial disparities in the management of hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and complications of portal hypertension: A National Study. Hepatology 2007;45:1282–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015;105:e60–e76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]