Abstract

Background

Oral gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) supplementation increases growth hormone (GH) serum levels and protein synthesis. Therefore, post-exercise supplementation using GABA and protein may help enhance training-induced muscle hypertrophy. We evaluated whether GABA with whey protein enhanced muscular hypertrophy in men after progressive resistance training.

Methods

Twenty-one healthy men (26 - 48 years) were randomized to receive whey protein (WP; 10 g) or whey protein + GABA (WP + GABA; 10 g + 100 mg) daily for 12 weeks. Both groups performed resistance training twice per week (three sets of 12 repetitions at 60% of maximal strength; leg press, leg extension, leg curl, chest press, and pull down). Body composition was assessed using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.

Results

In the WP + GABA group, resting plasma GH concentrations were significantly elevated at 4 and 8 weeks, compared to baseline. However, resting plasma GH concentrations in the WP group were only significantly elevated at 8 weeks. After 12 weeks, the WP + GABA group exhibited significantly greater increase in whole body fat-free mass than the WP group.

Conclusions

The GABA and whey protein combination was more effective for increasing whole body fat-free mass; daily GABA supplementation may help enhance exercise-induced muscle hypertrophy.

Keywords: Protein, Supplementation, Gamma-aminobutyric acid, Whey protein, Resistance training

Introduction

Skeletal muscle plays an important role in regulating resting metabolism, lipid oxidation, postprandial glucose disposal, and locomotion [1]. Muscle mass and function loss can also lead to reduction in physical activity, which may negatively affect metabolic processes (e.g. osteoporosis, obesity, and impaired glucose tolerance) [2]. In addition to improving sports performance, promoting muscular hypertrophy can improve muscle mass and function, which can subsequently increase quality of life and reduce the risks of various diseases.

Repeated bouts of anabolic stimulation (e.g. resistance training) increase muscle mass and improve muscle function by inducing muscle hypertrophy [3]. However, besides resistance exercise, nutrient intake can also stimulate muscle protein synthesis [4]. Protein and amino acid consumption promotes muscle protein synthesis by increasing amino acid blood levels and enhancing amino acid transport to muscle cells [5, 6]. Thus, amino acid and protein supplementation with resistance exercise augments muscle protein synthesis, compared to resistance exercise alone [7].

Different protein sources have distinct qualitative effects on muscle anabolism. Whey protein is rapidly digested and its high essential amino acid levels include branched-chain amino acids. In humans, ingestion of whey protein at rest and after resistance exercise stimulates muscle protein synthesis [8, 9] and promotes increases in lean body mass, compared to ingestion of other protein sources (e.g. casein and soy protein) [10, 11], although not all studies agree with the superiority of whey over casein [12, 13]. Therefore, milk-based proteins (e.g. whey) combined with resistance exercise are effective for promoting muscular hypertrophy.

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is a widely distributed amino acid found in foods, such as vegetables, fruits, and fermented foods. In vertebrates, GABA exists in the brain and acts as an inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system [14]. Oral GABA administration relieves anxiety [15], reduces psychological stress [16], induces relaxation [17], and improves sleep [18] by increasing total and parasympathetic nerve activities [19]. GABA also supports the physiologic adjustment of pituitary gland function and controls growth hormone (GH) secretion from the pituitary gland [20, 21]. Thus, GH plays an important role in skeletal muscle growth and maintenance [22]. GH has acute stimulatory effects on amino acid transport [23] and insulin growth factor-1 production, which promotes muscle protein synthesis [24]. GABA administration in humans elevated plasma GH concentrations at rest [25, 26]. Moreover, GABA administration in male rats for 10 days increased resting plasma GH concentrations and promoted protein synthesis at baseline in the gastrocnemius muscle, brain, and liver [27]. Conversely, in hypophysectomized rats, GABA does not stimulate GH secretion; hence, GABA-induced GH-concentration increase may influence the pituitary gland [28]. Augmented basal GH concentration by intravenous human recombinant GH (hrGH) administration in young men significantly increased muscle protein synthesis at rest [29]. Additionally, daily hrGH administration in old women for 4 weeks showed a 50% increase in muscle protein synthesis at rest [30]. Although these indicate that basal GH level may modulate muscle protein turnover, no study has investigated effects of increased basal GH plus resistance training on muscle hypertrophy.

We aimed to examine the effects of oral GABA plus whey protein supplementation on muscular hypertrophy in men after progressive resistance training. We hypothesized that GABA administration with post-exercise protein supplementation may enhance training-induced muscle hypertrophy concomitant with elevated resting plasma GH concentrations.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

We included 26 healthy and physically active Japanese men (26 - 48 years) who did not exercise regularly. They were screened based on absence of clinical history, normal blood pressure values, and absence of specific lifestyle factors (e.g. sleep time and physical activity). All subjects provided written informed consent before participation; this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Pharma Foods International Co., Ltd. All procedures were performed in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study design

We used a randomized double-blind parallel-group design. The 26 subjects were randomized into two groups that received daily whey protein doses (WP, n = 13) or whey protein and GABA (WP + GABA, n = 13) for 12 weeks and performed resistance exercise twice per week. Body composition and maximal strength were measured at baseline and after 12 weeks. Resting plasma GH concentrations were assessed at baseline, 4, 8, and 12 weeks. Blood sampling was performed after an overnight fast on a non-exercise day morning. Dietary habits were assessed using a brief-type self-administered diet history questionnaire (BDHQ) [31] at baseline and 12 weeks.

Supplements

The WP group ingested 10 g whey protein powder (36.1 kcal, 8.85 g protein); the WP + GABA group ingested a mixed powder (36.6 kcal) that contained 10 g whey protein powder and 125 mg GABA powder (0.5 kcal, 100 mg GABA). Subjects were instructed to ingest the supplements within 15 min of training, or before sleep on a non-exercise day. Each supplement was dissolved in 150 mL water immediately before ingestion. The whey protein powder was a whey protein isolate (Lactocrystal®; Nippon Shinyaku Co., Ltd, Kyoto, Japan); the GABA powder was produced through natural fermentation using a specific lactic acid bacteria strain (Pharma GABA®; 80% purity; Pharma Foods International Co., Ltd, Kyoto, Japan).

Resistance training program

The resistance training program included five upper-body and lower-body exercises: leg press, leg extension, leg curl, chest press, and pull down (LifeFitness, Schiller Park, IL, USA). Both groups performed the same training program. Training sessions were completed within 60 min and included the following: 5 min, warm-up (ergometer cycling); 45 min, resistance exercise; and 10 min, stretching exercise. This training program was performed twice per week in a fitness club with training equipment and included one unsupervised and one professional trainer-supervised session per week. All resistance exercises were performed in three sets (12 repetitions; 2 - 3 min rest periods). Maximal strength was measured at baseline and after 12 weeks using the indirect measurement technique. The warm-up load was estimated to allow the subject to complete 5 - 8 repetitions. Weight was increased gradually until a failed attempt or until appropriate form was not maintained. The percentage of repetition maximum (RM) was determined based on number of repetitions. Maximal strength was calculated by dividing weight by percentage of RM [32]. Exercise intensity was set at 50% maximal strength for the first week and then raised to 60% after week 1. Weights were progressively increased in 2.5 - 5 kg intervals when the prescribed repetitions could be completed. The trainer ensured that subjects provided maximum effort and intensity for all supervised training sessions. Subjects were instructed to only perform exercises as part of the training program; those who missed three exercise sessions were excluded from the analysis.

Body composition and plasma measurements

Body composition (fat-free mass, fat mass, and total body mass) was assessed for all subjects using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (GE Healthcare, Madison, WI, USA). Blood samples were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 15 min to isolate plasma fractions. Plasma GH concentrations were measured using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for human GH (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Statistical analysis

Mean and standard deviation (SD) were used for descriptive statistics. A 2 × 2 repeated-measure analysis of variance was used to assess inter-group differences (WP vs. WP + GABA) and differences between the time points. Post hoc comparisons were analyzed using the Bonferroni test. The two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was used to compare changes in fat-free mass between the groups (WP vs. WP + GABA). Differences were considered significant at P values < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel version 2013-version 15.0.4849.1003 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). The University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trials Registry number is UMIN000025842.

Results

Participant characteristics and compliance

The 26 men were randomized into the WP or WP + GABA groups; age and body composition did not differ between groups. Five subjects were subsequently excluded from the analysis because of personal reasons (WP, n = 1; WP + GABA, n = 1), not completing 90% of supplement intake requirements (WP, n = 1), and not completing 90% of exercise sessions (WP, n = 1; WP + GABA, n = 1). Thus, 21 subjects completed the 12-week program (WP, n = 10, 40.1 ± 7.9 years; WP + GABA, n = 11, 38.8 ± 5.7 years).

Dietary intake

There were no significant intra-group (at baseline vs. 12 weeks) or inter-group (WP group vs. WP + GABA group) differences in the dietary intake values (Table 1).

Table 1. Nutritional Intake Values at Baseline and After 12 Weeks.

| WP group |

WP + GABA group |

ANOVA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 12 weeks | Baseline | 12 weeks | ||

| Energy intake (kcal/day) | 2,153 ± 1,034 | 2,105 ± 723 | 1,681 ± 585 | 1,761 ± 395 | G: P = 0.186, T: P = 0.907, G × T: P = 0.651 |

| Protein intake (g/day) | 69 ± 24 | 75 ± 24 | 61 ± 26 | 62 ± 20 | G: P = 0.302, T: P = 0.431, G × T: P = 0.488 |

| Carbohydrate intake (g/day) | 303 ± 170 | 299 ± 125 | 219 ± 79 | 218 ± 58 | G: P = 0.103, T: P = 0.913, G × T: P = 0.925 |

| Fat intake (g/day) | 53 ± 19 | 54 ± 18 | 49 ± 21 | 50 ± 15 | G: P = 0.608, T: P = 0.809, G × T: P = 0.957 |

Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation. WP: whey protein; WP + GABA: whey protein + gamma-aminobutyric acid; ANOVA: analysis of variance; G: group effect; T: time effect; G × T: group × time effect.

Maximal strength

The mean maximal strength for each exercise was improved after 12 weeks (Table 2). Lower body maximal strength significantly improved within each group after resistance training (leg press, leg extension, and leg curl: all P < 0.05), although there were no significant inter-group differences. Upper body maximal strength also significantly improved within each group after resistance training (chest press and pull down: both P < 0.05), although there were no significant inter-group differences.

Table 2. Maximal Strength Values at Baseline and After 12 Weeks.

| WP group |

WP + GABA group |

ANOVA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 12 weeks | Baseline | 12 weeks | ||

| Leg press (kg) | 127 ± 31 | 202 ± 53 | 133 ± 38 | 230 ± 74 | G: P = 0.414, T: P = 0.000, G × T: P = 0.404 |

| Leg extension (kg) | 64 ± 17 | 91 ± 33 | 64 ± 13 | 91 ± 15 | G: P = 0.968, T: P = 0.000, G × T: P = 0.947 |

| Leg curl (kg) | 53 ± 14 | 77 ± 22 | 55 ± 11 | 78 ± 19 | G: P = 0.866, T: P = 0.000, G × T: P = 0.929 |

| Chest press (kg) | 52 ± 11 | 65 ± 13 | 63 ± 14 | 78 ± 16 | G: P = 0.058, T: P = 0.000, G × T: P = 0.727 |

| Pull down (kg) | 59 ± 15 | 73 ± 15 | 65 ± 15 | 78 ± 15 | G: P = 0.411, T: P = 0.000, G × T: P = 0.876 |

Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation. WP: whey protein; WP + GABA: whey protein + gamma-aminobutyric acid; ANOVA: analysis of variance; G: group effect; T: time effect; G × T: group × time effect.

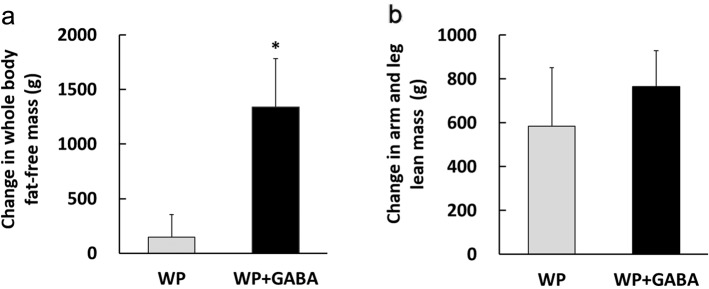

Resting plasma GH concentrations

The WP + GABA group exhibited significantly higher resting plasma GH concentrations at weeks 4 and 8, compared to baseline (P < 0.05, Fig. 1). The WP group exhibited significantly higher concentrations only at week 8, compared to baseline (P < 0.05). However, there were no significant inter-group differences.

Figure 1.

Resting plasma growth hormone concentrations. Values represent the mean ± standard error for 10 subjects (the whey protein group (WP)) or 11 subjects (the whey protein + gamma-aminobutyric acid group (WP + GABA)). *P < 0.05 vs. baseline of the WP + GABA group; **P < 0.05 vs. baseline of the WP group.

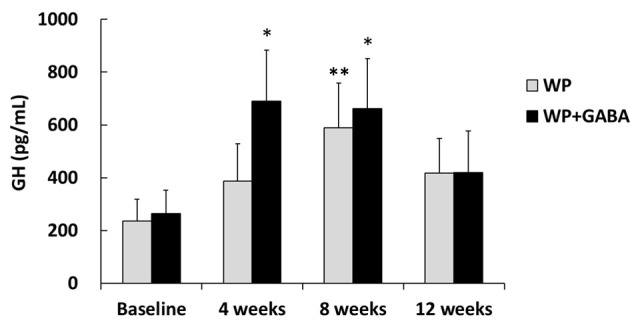

Body weight and composition

There was a significant time effect (P < 0.05) and group × time interaction effect (P <0.05) for whole body fat-free mass (Table 3). However, no significant differences within or between group were detected with post hoc test. There was also a significant time effect (P < 0.05) for arm and leg lean mass, although there was no significant group effect by time-interaction. Body weight, body mass index (BMI), and fat mass did not change significantly after 12 weeks.

Table 3. Body Composition at Baseline and After 12 Weeks.

| WP group |

WP + GABA group |

ANOVA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 12 weeks | Baseline | 12 weeks | ||

| Weight (kg) | 70.5 ± 8.6 | 70.8 ± 9.0 | 70.5 ± 8.9 | 71.7 ± 10.4 | G: P = 0.917, T: P = 0.079, G × T: P = 0.252 |

| Fat mass (kg) | 16.8 ± 4.9 | 16.9 ± 5.4 | 16.4 ± 5.6 | 16.3 ± 6.3 | G: P = 0.846, T: P = 0.957, G × T: P = 0.773 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.3 ± 2.2 | 23.4 ± 2.3 | 24.2 ± 3.6 | 24.6 ± 4.1 | G: P = 0.501, T: P = 0.089, G × T: P = 0.247 |

| Whole body fat-free mass (kg) | 50.9 ± 4.7 | 51.0 ± 4.6 | 51.2 ± 5.4 | 52.5 ± 6.2 | G: P = 0.714, T: P = 0.011, G × T: P = 0.037 |

| Arm and leg lean mass (kg) | 23.0 ± 2.3 | 23.6 ± 2.7 | 23.4 ± 2.8 | 24.2 ± 2.9 | G: P = 0.695, T: P = 0.001, G × T: P = 0.584 |

Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation. WP: whey protein; WP + GABA: whey protein + gamma-aminobutyric acid; BMI: body mass index; ANOVA: analysis of variance; G: group effect; T: time effect; G × T: group × time effect.

On the contrary, the WP + GABA group exhibited greater increases in whole body fat-free mass (Fig. 2a) after 12 weeks than the WP group (WP: 146 ± 207 g vs. WP + GABA: 1,340 ± 443 g; P < 0.05). There was no significant inter-group difference in arm and leg lean mass (Fig. 2b) after 12 weeks (WP: 586 ± 265 g vs. WP + GABA: 765 ± 164 g; P = 0.58).

Figure 2.

Change in body composition after 12 weeks as measured using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. (a) Whole body fat-free mass and (b) arm and leg lean mass. Values represent the mean ± standard error for 10 subjects (the whey protein group (WP)) or 11 subjects (the whey protein + gamma-aminobutyric acid group (WP + GABA)). *P < 0.05 vs. the WP group.

Discussion

Our main novel finding was that daily supplementation using GABA and whey protein significantly enhanced whole body fat-free mass after 12 weeks of resistance training among untrained middle-aged men with suboptimal dietary protein intake, which suggests that GABA (in combination with whey protein) may help enhance exercise-induced muscle hypertrophy.

GABA’s ability to enhance muscle hypertrophy may be related in part to its ability to increase basal GH concentrations. Concurrently, GH plays an important role in promoting amino acid transport, cellular amino acid uptake, and skeletal muscle growth [22-24, 33]. High amino acid concentrations in muscle cells can promote protein synthesis and muscle hypertrophy [34]. Oral GABA supplementation promotes protein synthesis in various parts (e.g. the brain and gastrocnemius muscle) and higher plasma GH concentrations at rest in rats [26]. Here, resting plasma GH concentrations in the WP + GABA group (10 g whey protein and 100 mg GABA) were significantly higher at weeks 4 and 8 than at baseline. However, in the WP group (10 g whey protein), plasma GH concentrations increased gradually; the only significant difference was at week 8. In addition to GABA, various amino acids (e.g. arginine, lysine, and branched-chain amino acids) can promote GH secretion [35, 36]. Therefore, gradually increasing GH concentrations in the WP group may be related to amino acids included in whey powder. Conversely, the earlier increase in GH concentrations in the WP + GABA group may be related to the complementary effects of GABA and whey protein amino acids. The higher plasma GH concentration at rest is thought to promote muscle protein synthesis. Direct intravenous GH administration in young men for increasing basal GH concentration indicated a significant increase in basal muscle protein synthesis [29]. Additionally, GH administration in old women for 4 weeks showed a 50% increase in muscle protein synthesis at rest [30]. Thus, GABA may have partly promoted muscle protein synthesis, leading to increase in whole body fat-free mass by elevating resting plasma GH concentrations. Nevertheless, both groups exhibited attenuations in GH concentrations between weeks 8 and 12. Therefore, any anabolic effect of elevated basal GH concentration may have peaked in weeks 4 - 8. However, more frequent assessment is necessary to detect changes in fat-free mass at an early stage. Hence, future studies are warranted to investigate the relationship between changes in resting GH level and resistance exercise-induced muscle hypertrophy.

GABA has other physiological effects, including sleep quality improvement and fatigue reduction. Sleep deprivation negatively influences exercise performance and post-exercise recovery [37, 38]. GABA improves sleep quality by shortening sleep latency and increasing non-rapid eye movement (REM) sleeping time [18]. GABA also reduces acute psychological and physical fatigue by suppressing sympathetic response and increasing parasympathetic response under stressful tasks [19, 39]. Although we did not evaluate sleep quality and psychological effects, there is a possibility that these physiological effects of GABA lead to improved motivation during exercise and/or improved post-exercise recovery. Further studies are warranted to investigate these potential benefits of GABA ingestion.

Studies have found that the 6-24-week period of protein supplementation and resistance exercise promoted a 800 - 3,400 g increase in whole body fat-free mass [3, 11]. However, we found that the WP group exhibited a relatively small change in fat-free mass, compared to previously reported changes [3, 11]. This discrepancy may be related to three factors. The first factor is total protein supplementation amount after resistance exercise that exhibits dose-dependent increase in muscle protein synthesis with plateaus at 20 g and 40 g for young and older individuals, respectively [40]. Therefore, 10-g dosage is considered insufficient for maximal anabolic response [5, 41]. Our subjects received a daily 10-g whey protein dose, which may have been insufficient to induce optimal muscle protein synthesis and hypertrophy. The second factor is resistance training intensity and frequency, which can affect muscle mass and strength. A study found that weekly resistance training did not provide significantly greater muscle strength and lean body mass than training three times per week [42]. In this study, untrained subjects performed resistance training twice per week, which may have been insufficient to stimulate maximal muscle hypertrophy. The third factor is low dietary protein intake (Table 1). Protein intake was approximately 1 g/kg/day in both groups, which satisfied an Recommended Dietary Allowance of 0.8 g/kg/day but was likely suboptimal to induce maximal hypertrophy. Nevertheless, the WP + GABA group exhibited a 12-week change of >1 kg in fat-free mass, which was significantly greater than the increase in the WP group (that received the same supplementation and underwent the same training program). Additionally, both groups exhibited similar changes in arm and leg lean masses, suggesting that the enhanced whole body fat-free mass in the WP + GABA group was related to enhanced lean mass in the trunk (rather than in the legs and/or arms). Therefore, these findings may indicate that GABA with whey protein supplementation increases whole body fat-free mass more effectively at low whey protein doses and low-frequency resistance exercise than whey protein supplementation alone.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the effects of GABA in combination with whey protein supplementation on muscular hypertrophy in men during a 12-week program of progressive resistance training. Our results indicate that GABA plus a suboptimal dose of whey protein resulted in significantly enhanced whole body fat-free mass, compared to whey protein alone. Thus, daily supplementation with GABA may be a useful addition to whey protein for enhancing exercise-induced muscle hypertrophy. Nevertheless, further studies are needed to validate our findings, to determine whether GABA directly promotes muscle protein synthesis, and to investigate the mechanism through which GABA enhances lean mass.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Hisayuki Kosaka for his help with conducting the clinical portion of this study. We thank Ms. Tomoko Taniguchi for her help with body composition measurement using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. We would like to acknowledge those who volunteered to participate in our research.

Financial Disclosure

Funding for the study was provided by Pharma Foods International Co., Ltd.

Conflict of Interest

Maya Sakashita, Utano Nakamura, Noriko Horie, and Mujo Kim are working for Pharma Foods International Co., Ltd. which provided GABA in this study.

Informed Consent

The subjects were fully informed and gave their written consent to participate in the study.

Author Contributions

MS, NH, MK, YY, and SF conceived and designed the experiments; MS, UN, and SF performed experiments and analyzed the data; MS drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Wolfe RR. The underappreciated role of muscle in health and disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(3):475–482. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.3.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dutta C, Hadley EC. The significance of sarcopenia in old age. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50(Spec No):1–4. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50A.Special_Issue.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cermak NM, Res PT, de Groot LC, Saris WH, van Loon LJ. Protein supplementation augments the adaptive response of skeletal muscle to resistance-type exercise training: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(6):1454–1464. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.037556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morton RW, McGlory C, Phillips SM. Nutritional interventions to augment resistance training-induced skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Front Physiol. 2015;6:245. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore DR, Robinson MJ, Fry JL, Tang JE, Glover EI, Wilkinson SB, Prior T. et al. Ingested protein dose response of muscle and albumin protein synthesis after resistance exercise in young men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(1):161–168. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biolo G, Tipton KD, Klein S, Wolfe RR. An abundant supply of amino acids enhances the metabolic effect of exercise on muscle protein. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(1 Pt 1):E122–129. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.273.1.E122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Churchward-Venne TA, Burd NA, Phillips SM. Nutritional regulation of muscle protein synthesis with resistance exercise: strategies to enhance anabolism. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2012;9(1):40. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tipton KD, Elliott TA, Cree MG, Aarsland AA, Sanford AP, Wolfe RR. Stimulation of net muscle protein synthesis by whey protein ingestion before and after exercise. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292(1):E71–76. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00166.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tipton KD, Elliott TA, Cree MG, Wolf SE, Sanford AP, Wolfe RR. Ingestion of casein and whey proteins result in muscle anabolism after resistance exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(12):2073–2081. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000147582.99810.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang JE, Moore DR, Kujbida GW, Tarnopolsky MA, Phillips SM. Ingestion of whey hydrolysate, casein, or soy protein isolate: effects on mixed muscle protein synthesis at rest and following resistance exercise in young men. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2009;107(3):987–992. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00076.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volek JS, Volk BM, Gomez AL, Kunces LJ, Kupchak BR, Freidenreich DJ, Aristizabal JC. et al. Whey protein supplementation during resistance training augments lean body mass. J Am Coll Nutr. 2013;32(2):122–135. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2013.793580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soop M, Nehra V, Henderson GC, Boirie Y, Ford GC, Nair KS. Coingestion of whey protein and casein in a mixed meal: demonstration of a more sustained anabolic effect of casein. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;303(1):E152–162. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00106.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reitelseder S, Agergaard J, Doessing S, Helmark IC, Schjerling P, van Hall G, Kjaer M. et al. Positive muscle protein net balance and differential regulation of atrogene expression after resistance exercise and milk protein supplementation. Eur J Nutr. 2014;53(1):321–333. doi: 10.1007/s00394-013-0530-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts E, Frankel S. gamma-Aminobutyric acid in brain: its formation from glutamic acid. J Biol Chem. 1950;187(1):55–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdou AM, Higashiguchi S, Horie K, Kim M, Hatta H, Yokogoshi H. Relaxation and immunity enhancement effects of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) administration in humans. Biofactors. 2006;26(3):201–208. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520260305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamura H, Takishima T, Kometani T, Yokogoshi H. Psychological stress-reducing effect of chocolate enriched with gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in humans: assessment of stress using heart rate variability and salivary chromogranin A. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2009;60(Suppl 5):106–113. doi: 10.1080/09637480802558508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoto A, Murao S, Motoki M, Yokoyama Y, Horie N, Takeshima K, Masuda K. et al. Oral intake of gamma-aminobutyric acid affects mood and activities of central nervous system during stressed condition induced by mental tasks. Amino Acids. 2012;43(3):1331–1337. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-1206-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamatsu A, Yamashita Y, Pandharipande T, Maru I, Kim M. Effect of oral gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) administration on sleep and its absorption in humans. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2016;25(2):547–551. doi: 10.1007/s10068-016-0076-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujibayashi M, Kamiya T, Takagaki K, Moritani T. Activation of autonomic nervous system activity by the oral ingestion of GABA. J Jpn Soc Nutr Food Sci. 2008;61:129–133. doi: 10.4327/jsnfs.61.129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Acs Z, Szabo B, Kapocs G, Makara GB. gamma-Aminobutyric acid stimulates pituitary growth hormone secretion in the neonatal rat. A superfusion study. Endocrinology. 1987;120(5):1790–1798. doi: 10.1210/endo-120-5-1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson RA, Mitchell R. Effects of gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor agonists on the secretion of growth hormone, luteinizing hormone, adrenocorticotrophic hormone and thyroid-stimulating hormone from the rat pituitary gland in vitro. J Endocrinol. 1986;108(1):1–8. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1080001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Godfrey RJ, Madgwick Z, Whyte GP. The exercise-induced growth hormone response in athletes. Sports Med. 2003;33(8):599–613. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200333080-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riggs TR, Walker LM. Growth hormone stimulation of amino acid transport into rat tissues in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1960;235:3603–3607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gunawardane K, Krarup HT, Sandahl CJ, Lunde JJO. In: De Groot LJ, Chrousos G, Dungan K, Feingold KR, Grossman A, Hershman JM, et al., editors. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc; 2015. Normal physiology of growth hormone in adults; pp. 2000–2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cavagnini F, Benetti G, Invitti C, Ramella G, Pinto M, Lazza M, Dubini A. et al. Effect of gamma-aminobutyric acid on growth hormone and prolactin secretion in man: influence of pimozide and domperidone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1980;51(4):789–792. doi: 10.1210/jcem-51-4-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cavagnini F, Invitti C, Pinto M, Maraschini C, Di Landro A, Dubini A, Marelli A. Effect of acute and repeated administration of gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) on growth hormone and prolactin secretion in man. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1980;93(2):149–154. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.0930149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tujioka K, Okuyama S, Yokogoshi H, Fukaya Y, Hayase K, Horie K, Kim M. Dietary gamma-aminobutyric acid affects the brain protein synthesis rate in young rats. Amino Acids. 2007;32(2):255–260. doi: 10.1007/s00726-006-0358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tujioka K, Ohsumi M, Sakamoto K, Thanapreedawat P, Akao M, Kim M, Hayase K. et al. Effect of dietary gamma-aminobutyric acid on the brain protein synthesis rate in hypophysectomized aged rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2011;57(4):285–291. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.57.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fryburg DA, Gelfand RA, Barrett EJ. Growth hormone acutely stimulates forearm muscle protein synthesis in normal humans. Am J Physiol. 1991;260(3 Pt 1):E499–504. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1991.260.3.E499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Butterfield GE, Thompson J, Rennie MJ, Marcus R, Hintz RL, Hoffman AR. Effect of rhGH and rhIGF-I treatment on protein utilization in elderly women. Am J Physiol. 1997;272(1 Pt 1):E94–99. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.272.1.E94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kobayashi S, Honda S, Murakami K, Sasaki S, Okubo H, Hirota N, Notsu A. et al. Both comprehensive and brief self-administered diet history questionnaires satisfactorily rank nutrient intakes in Japanese adults. J Epidemiol. 2012;22(2):151–159. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20110075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baechle TR, Roger WE, Dan W. In: Human kinetics. Baechle TR, Roger WE, editors. Champaign: Human Kinetics Publishers; 2000. Essentials of strength training and conditioning second edition; pp. 410–411. [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Palo EF, Gatti R, Antonelli G, Spinella P. Growth hormone isoforms, segments/fragments: does a link exist with multifunctionality? Clin Chim Acta. 2006;364(1-2):77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carroll CC, Fluckey JD, Williams RH, Sullivan DH, Trappe TA. Human soleus and vastus lateralis muscle protein metabolism with an amino acid infusion. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288(3):E479–485. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00393.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Collier SR, Casey DP, Kanaley JA. Growth hormone responses to varying doses of oral arginine. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2005;15(2):136–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chromiak JA, Antonio J. Use of amino acids as growth hormone-releasing agents by athletes. Nutrition. 2002;18(7-8):657–661. doi: 10.1016/S0899-9007(02)00807-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leeder J, Glaister M, Pizzoferro K, Dawson J, Pedlar C. Sleep duration and quality in elite athletes measured using wristwatch actigraphy. J Sports Sci. 2012;30(6):541–545. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2012.660188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samuels C. Sleep, recovery, and performance: the new frontier in high-performance athletics. Neurol Clin. 2008;26(1):169–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2007.11.012. ix-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kanehira T, Nakamura Y, Nakamura K, Horie K, Horie N, Furugori K, Sauchi Y. et al. Relieving occupational fatigue by consumption of a beverage containing gamma-amino butyric acid. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2011;57(1):9–15. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.57.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang Y, Breen L, Burd NA, Hector AJ, Churchward-Venne TA, Josse AR, Tarnopolsky MA. et al. Resistance exercise enhances myofibrillar protein synthesis with graded intakes of whey protein in older men. Br J Nutr. 2012;108(10):1780–1788. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511007422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moore DR, Areta J, Coffey VG, Stellingwerff T, Phillips SM, Burke LM, Cleroux M. et al. Daytime pattern of post-exercise protein intake affects whole-body protein turnover in resistance-trained males. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2012;9(1):91. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-9-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schoenfeld BJ, Ratamess NA, Peterson MD, Contreras B, Tiryaki-Sonmez G. Influence of resistance training frequency on muscular adaptations in well-trained men. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29(7):1821–1829. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]