Abstract

Background:

Efficacy of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among men who have sex with men (MSM) is well documented in randomized trials. Following trial completion, participants are challenged with acquiring PrEP on their own, and remaining adherent.

Methods:

This was a follow-up study of the TAPIR randomized controlled multi-center PrEP trial. Participants were contacted after their last TAPIR visit (i.e., after study provided PrEP was discontinued) to attend observational post-trial visits 24 and 48 weeks later. Adherence during TAPIR and post-trial visits was estimated by dried blood spot (DBS) intracellular tenofovir diphosphate (TFV-DP) levels (adequate adherence defined as TFV-DP levels >719 fmol/punch). Binary logistic regression analysis assessed predictors of completing post-trial visits and PrEP adherence among participants completing ≥ 1 visit.

Results:

Of 395 TAPIR participants who were on PrEP as part of the TAPIR trial for a median of 597 days (range 3–757 days), 122 (31%) completed ≥ 1 post-trial visit (57% of UCSD participants completed post-trial visits, while this was 13% or lower for other study sites). Among participants who completed ≥ 1 post-trial visit, 57% had adequate adherence post-trial. Significant predictors of adequate adherence post-trial were less problematic substance use, higher risk behavior, and adequate adherence in year 1 of TAPIR.

Conclusion:

More than half of PrEP users followed after trial completion had successfully acquired PrEP and showed adequate adherence. Additional adherence monitoring and interventions measures may be needed for those with low PrEP adherence and problematic substance use during the first year of trial.

Keywords: Adherence, continuum, real-life cohort, substance use, risk behavior

Introduction

Despite declining numbers of incident infections, HIV continues to have a disproportionate impact on men who have sex with men (MSM) 1–3. The efficacy of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) / emtricitabine (FTC) for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in MSM has been well documented in several randomized controlled trials 4–6. The effectiveness of TDF/FTC for HIV PrEP strongly depends on adherence 7,8. This was also outlined by a recently published mathematical model showing increased adherence was the only factor that reduced the number needed to treat with PrEP to prevent one HIV infection 9. For MSM, the iPrEx study was pivotal in showing that TDF/FTC reduced the risk of HIV infection in MSM by >90% in those with adherence defined by tenofovir diphosphate (TFV-DP) drug levels commensurate with 4 or more tablets per week 10.

PrEP adherence measures vary widely between randomized controlled trials 4–6,11–15. While self-reported adherence measures seem to overestimate actual adherence16, trials measuring TFV-DP drug levels reported adequate adherence (corresponding to 4 or more tablets a week) in about 80–90% of study participants, while near-perfect adherence (corresponding to 7 or more tablets a week) in 40–50% of study participants 17,18. However, these published data do not inform us about PrEP use and adherence after roll-off from PrEP trials and PrEP demonstration projects, when participants are challenged with establishing care, acquiring PrEP, and remaining adherent 14,19–22.

This study aimed to identify predictors of PrEP adherence post-trial period for participants completing the TAPIR randomized controlled trial of text messaging versus standard care for adherence to daily TDF/FTC PrEP in MSM in Southern California between 2014–2016 (NCT01761643).

Material and Methods

Setting and Participants

To achieve this goal, we leveraged the ending of an existing PrEP demonstration project, the TAPIR trial (CCTG595), a randomized controlled trial of individualized text messaging versus standard care for adherence to daily TDF/FTC PrEP, conducted between 2014–2016 (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01761643) 17. In TAPIR, PrEP was given in combination with safety monitoring, HIV testing, and risk reduction counseling to MSM and transgender women 17. The pool of potential participants for follow-up came from 395 patients (392 MSM and 3 transgender women) who had at least one DBS PrEP level measured during TAPIR at four Southern California medical centers [(University of California San Diego (UCSD), University of Southern California (USC), Long Beach Health Department, and Harbor-University of California Los Angeles (UCLA)] 23. Eligible participants for TAPIR were HIV-uninfected MSM and transgender women (age ≥ 18 years) with elevated risk for HIV acquisition as previously published 23. Although the primary outcome for TAPIR was TFV-DP drug levels at weeks 12 and 48, study participants were allowed to continue past week 48 on study drug until the last subject completed their week 48 visit; at that timepoint everyone was discontinued from study-provided PrEP 17 upon when study-provided PrEP was discontinued. At the final two visits, participants were provided with information regarding local PrEP providers and where to obtain PrEP in the community, but were on their own to self-initiate PrEP continuation. As part of the current study, we conducted prospective strictly observational (i.e., no PrEP services were provided) follow-up visits at least 24 weeks following TAPIR trial roll-off and a second follow up visit at 24 weeks following the first follow up visit. Follow-up visits were conducted at UCSD, USC and Harbor UCLA only. Follow up visits of TAPIR participants enrolled at the Long Beach Health Department were conducted at Harbor UCLA.

Measures

PrEP Continuation and Adherence

PrEP continuation was defined by participant self-report of linking to a provider and continuing to receive PrEP from a provider during post-TAPIR study visits. Adherence was estimated by dried blood spot (DBS) intracellular TFV-DP levels only for those who reported having taken any PrEP within the last 2 weeks. A concentration of >719 fmol/punch was used to estimate four or more tablets per week on average (i.e., “adequate” adherence). This value is the unrounded lower quartile corresponding to 700 fmol/punch level used in the iPrEx OLE study, which showed 0 out of 28 seroconversions when TFV-DP was at or above 700 fmol/punch 24. A concentration of >1246 fmol/punch was defined as “near-perfect” adherence, associated with taking seven doses of TDF in past week 24,25. Intracellular TFV-DP concentrations were performed at the last on-drug visit that occurred on or before the TAPIR 48-week visit, and at the 24- and 48-weeks post-trial visits for participants reporting PrEP continuance at the respective time points as described before 25.

Frequency of substance use in past 3 months was assessed at week 48 TAPIR visit using a Substance Use Screening questionnaire (SCID). We also evaluated stimulant substances use (including poppers, methamphetamine, cocaine, ecstasy, amphetamine and other stimulants), non-stimulant substances use (including heroin, other opioids e.g. vicodin, oxycontin, sedatives, antianxiety drugs, hallucinogens, dissociative drugs, inhalants), and any substance use (including both stimulant and non-stimulant substances listed above). Problematic use was assessed at baseline using the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST10) and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), and defined as described before 24.

Self-reported sexual risk behavior was assessed at week 48 of the TAPIR trial via questionnaires. Sexually transmitted infection (STI) screening assessments during the first year of TAPIR included syphilis (serum rapid plasma regain (RPR) and, if positive, confirmatory treponemal test), as well as NAAT of both urine, pharyngeal and rectal swabs for chlamydia and gonorrhea (Hologic Aptima). Newly diagnosed STIs were communicated to participants who were referred to their provider or a local STD clinic for treatment. Incident STI was defined as having positive results of gonorrhea or chlamydia at any site or positive syphilis RPR result during the first year of TAPIR. Sexual risk behavior and STI were summarized into the CalcR Score, developed as an alternative tool to evaluate HIV risk based on patient-specific HIV transmission events 26. The score has been generated from a mathematical equation that focuses on sexual transmission methods and biological factors that may increase HIV acquisition in the absence of PrEP: condomless receptive and insertive anal intercourse acts and incident STDs including gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis and herpes, as reported for the last month, as described before 26.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 25 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois). Demographics, PrEP adherence, substance use, and risk behaviors assessed at week 48 of the TAPIR trial were compared between participants who completed at least one post-trial visit versus those who did not using Fisher’s exact test/Chi-square test for categorical variables and Students T-Test/Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test for continuous variables. Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare DBS levels between TAPIR week 48 and post-trial visits. Univariate and multivariable binary logistic regression analyses assessed predictors of completing post-trial visits (model 1, UCSD participants only because post-trial follow up rates were >50% at UCSD while they were below 13% at other study sites; alternative model 1 included participants from all sites but used study site as clustering variable) and PrEP adherence among those who completed ≥ 1 visit (models 2, 3, 4, and 5, participants of all four study sites, model 4 and 5 used study site as clustering variable); alternative models 2 and 3 focused only on PrEP adherence among those on PrEP. Variables with a p-value <0.2 in univariate analysis were included in the multivariable model. Variables in the final model were selected with a stepwise forward procedure. Model discrimination was assessed by the goodness-of-fit Hosmer-Lemeshow statistics. Odds ratios (ORs) and adjusted odds ratios (aOR) including 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated and a p-value of <0·05 was considered statistically significant. The study was approved by the University of California, San Diego institutional review board (IRB) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Of 395 TAPIR participants who were enrolled in TAPIR for a median of 597 days (range 3–757 days) and provided with free PrEP during study engagement, 122 (31%) completed one or both post-trial visits; 108 individuals completed the 24-week post-trial visit and 96 the 48-week post-trial visit. For the last follow-up the total time of observation including both time in the trial and follow-up was median 1122 days (range 687–1534 days). Follow-up rate differed significantly between participating centers, and was highest at UCSD with 57% (100/174 participants). Lower participation was seen at other sites: 13% (17/127) at USC, 6% (3/47) for Long Beach, and 4% (2/47) for Harbor-UCLA. Further analyses on predictors of post-trial visits focused therefore on UCSD participants only (median TAPIR enrollment 616 days, range 21–734 days; 95 completed the 24-week post-trial visit and 82 the 48-week post-trial visit), while models on predictors of post-trial adherence included post-trial participants from all four study sites. Demographic data and characteristics at week 48 of the TAPIR trial for UCSD participants who did and did not complete ≥1 post-trial visit, as well as for USC, Long Beach and Harbor-UCLA participants who completed ≥1 post-trial visit are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1:

Demographic Data and Characteristics at week 48 of the TAPIR trial for University of California San Diego (UCSD) participants who did and did not complete ≥1 post-trial visits, and participants from University of Southern California (USC), Long Beach, and Harbor University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) who completed ≥1 post-trial visit, as well as participants from all study sites who completed post-trial visit(s) and had or had not adequate PrEP adherence.

| Variables: N(%) if not stated otherwise | UCSD TAPIR Participants who completed ≥1 post-trial visits (n=100) | UCSD TAPIR Participants who did not complete post-trial visits (n=74) | P-value | USC, Long Beach and UCLA TAPIR Participants who completed ≥1 post-trial visits (n=22) | Participants who completed ≥1 post-trial visits and had adequate PrEP adherence (n=70) | Participants who completed ≥1 post-trial visits but were not linked to PrEP or reached not adequate adherence (n=52) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender: | 0.425 | 1.000 | |||||

| Male | 100 (100%) | 73 (99%) | 22 (100%) | 70 (100%) | 52 (100%) | ||

| Transgender male to female | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Age, years; mean (SD) | 37 (10) | 33 (9) | 0.007 | 34 (9) | 38 (10) | 36 (11) | 0.489 |

| Race | 0.879 | 0.364 | |||||

| White | 74 (74%) | 54 (73%) | 16 (73%) | 54 (77%) | 36 (69%) | ||

| Hispanic Ethnicity: | 15 (15%) | 27 (36%) | 0.002 | 7 (32%) | 11 (16%) | 11 (21%) | 0.462 |

| Education: | 0.676 | 0.715 | |||||

| High School or lower | 8 (8%) | 10 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (6%) | 4/51 (8%) | ||

| Some College | 35 (35%) | 26 (35%) | 5/21 (24%) | 25 (36%) | 15/51 (29%) | ||

| Bachelors degree | 32 (32%) | 22 (30%) | 11/21 (52%) | 22 (31%) | 21/51 (41%) | ||

| Post graduate or advanced Degree | 25 (25%) | 16 (22%) | 5/21 (24%) | 18 (26%) | 12/51 (24%) | ||

| Household Income: | 0.359 | 0.983 | |||||

| < $2000/ month | 18 (18%) | 20 (27%) | 5/21 (24%) | 13 (18%) | 10/51 (20%) | ||

| > $2000/ month | 77 (77%) | 51 (69%) | 11/21 (24%) | 51 (73%) | 38/51 (75%) | ||

| Refused to answer | 5 (5%) | 3 (4%) | 5/21 (24%) | 6 (9%) | 4/51 (8%) | ||

| Intervention Arm (i.e. receiving daily text messages for PrEP adherence | 43 (43%) | 45 (61%) | 0.020 | 9 (41%) | 29 (41%) | 23 (44%) | 0.757 |

| Duration on TAPIR PrEP trial (days); mean, SD | 608 (141) | 462 (232) | <0.001 | 607 (115) | 634 (105) | 573 (164) | 0.015 |

| Calculated HIV sexual risk (CalcR) score (1-month) at week 48 TAPIR visit; median, IQR | 0.028 (0–0.107) | 0.050 (0–0.143) | 0.164 | 0.021 (0–0.073) | 0.039 (0–0.128) | 0.015 (0–0.073) | 0.076 |

| Adequate Adherence week 48 TAPIR trial | 90/97 (93%) | 46/59 (78%) | 0.007 | 17/21 (81%) | 67 (96%) | 40/48 (83%) | 0.023 |

| Near perfect Adherence week 48 TAPIR trial | 48/97 (49%) | 18/59 (31%) | 0.020 | 8/21 (38%) | 38 (54%) | 18/48 (38%) | 0.073 |

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) week 48; median points (IQR) | 5 (3–8) | 5 (3–9) | 0.918 | 4 (2–10) | 5 (3–9) | 5 (2–8) | 0.803 |

| Stimulant Substance use week 48 TAPIR | 27 (27%) | 25/73 (34%) | 0.305 | 8 (36%) | 19 (27%) | 16 (31%) | 0.661 |

| Non-stimulant Substance use (alcohol, marijuana, poppers excluded) week 48 TAPIR | 43 (43%) | 39/73 (53%) | 0.175 | 9 (41%) | 32 (46%) | 20 (38%) | 0.463 |

| Popper use | 39 (39%) | 36/73 (49%) | 0.176 | 12 (55%) | 31 (44%) | 20 (38%) | 0.519 |

| Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST10) week 48; median points (IQR) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | 0.172 | 2 (1–4) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | 0.021 |

N indicated for variables that were no available from all study participants.

Univariate and multivariable logistic regression models for predicting ≥1 post-trial visit among TAPIR trial participants at UCSD are shown in Table 2. Multivariable predictors of completing post-trial visits included more total days of TAPIR enrollment (i.e. more total days of study provided PrEP), adequate adherence at the week 48 TAPIR visit, and self-reported non-Hispanic ethnicity. Total days of TAPIR enrollment remained the strongest predictor in the stepwise approach, followed by non-Hispanic ethnicity. In the alternative model 1 which included study participants at all sites and used study site as clustering variable, multivariable predictors of completing post-trial visits included non-Hispanic ethnicity (aOR 2.58; p<0.001), adequate adherence at week 48 TAPIR visit (aOR 1.89; p<0.001), no self-reported popper use (aOR for popper use 0.42; p<0.001), total days of TAPIR enrollment (aOR 1.004 per day; p=0.001), not being randomized in the intervention arm (aOR for intervention arm 0.59; p=0.013), and more problematic alcohol use (aOR 1.07 per AUDIT score point; p=0.035).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariable binary Logistic Regression Models for predicting ≥1 post PrEP trial study visit among participants at the University of California San Diego.

| Model 1: Variables for Predicting Post-Trial Visit (n=174) | OR | 95% CI | p value | aOR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Model | Multivariable Model* | |||||

| Intervention Arm (i.e. receiving daily text messages for PrEP adherence | 0.486 | 0.264 – 0.897 | 0.021 | - | - | n.s. |

| Age (per year) | 1.044 | 1.011 – 1.079 | 0.009 | - | - | n.s. |

| Non-Hispanic ethnicity | 2.524 | 1.261 –5.051 | 0.009 | 3.606 | 1.598 – 9.993 | 0.002 |

| Higher Education category | 1.139 | 0·897 – 1.445 | 0.285 | |||

| Higher Income category | 1.212 | 1.019 – 1.443 | 0.030 | - | - | n.s. |

| Duration on PrEP trial (per day) | 1.004 | 1.002 – 1.006 | <0.001 | 1.004 | 1.001 – 1.006 | 0.003 |

| Adequate Adherence End of PrEP trial Study visit | 3.634 | 1.357 – 9.731 | 0.010 | 3.517 | 1.238 – 9.993 | 0.018 |

| Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST10; per score point) | 0.843 | 0.707 – 1.006 | 0.058 | - | - | n.s. |

| Stimulant Substance Use | 0.710 | 0.369 – 1.367 | 0.305 | |||

| Non-stimulant Substance Use (alcohol, marijuana and poppers excluded) | 0.658 | 0.358 – 1.207 | 0.176 | Not included | ||

| Popper use | 0.657 | 0.357 – 1.209 | 0.177 | Not included | ||

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; per score point) | 1.010 | 0.939 – 1.087 | 0.780 | |||

| Calculated HIV risk score (CalcR) Month | 0.323 | 0.028 – 3.673 | 0.362 | |||

Chi square 8.852; p=0.355 Hosmer Lemeshow; Forward Wald Binary Logistic Regression

Abbreviation: OR=odds ratio; aOR=adjusted odds ratio

Among 122 participants who completed ≥ 1 post-trial visit (i.e. 62 participants completed both visits, while 33 completed only one visit) at all sites, 95 (78%) indicated that they were on PrEP and had DBS levels measured. Overall, 70/95 (74%) had adequate adherence, and 32/95 (34%) near perfect adherence at their last post-trial visit where DBS was measured (6 individuals had DBS levels measured at 24-weeks post-trial but not 48-weeks post-trial where they indicated that they were not on PrEP). Demographic data and characteristics of participants completing post-trial visits with and without adequate adherence are depicted in Table 1. The only significant predictor in univariate analysis of self-reported linkage to PrEP at the last post-trial visit was less problematic substance use (OR per DAST10 score point 0.757, 95%CI 0.595 – 0.962; p=0.023).

Participants with adequate adherence at the week 48 TAPIR trial visit had also significantly higher DBS TFV-DP levels at last post-trial follow up than those without adequate adherence (median 993 fmol/punch, IQR 0–1397 vs. median 636 fmol/punch, IQR 0–758; p=0.030). The same was found for participants with near-perfect adherence at the week 48 TAPIR trial visit versus those without near-perfect adherence (median 1173 fmol/punch, IQR 0–1533 vs. median 791 fmol/punch, IQR 0–1092; p=0.021).

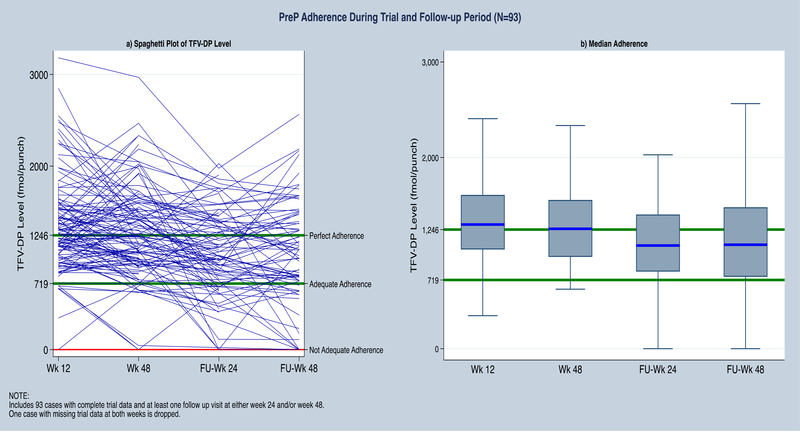

For individual visits, among those who were on PrEP 64/83 (77%) had adequate and 31/83 (37%) near-perfect adherence at 24-weeks post-trial; and 56/74 (76%) adequate and 26/74 (35%) near-perfect adherence at 48-weeks post-trial (Figure 1). DBS TFV-DP levels differed significantly between week 48 of TAPIR and week 24 post-trial (p<0.001; Wilcoxon’s signed rank test; Figure 1). However, a plot of individual adherence levels shows that levels stayed above adequate adherence in most participants (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Longitudinal dried blood spot (DBS) PrEP levels during TAPIR and post-trial. Figure includes 93 individuals who had DBS levels measured during week 24 and 48 of TAPIR and also at either weeks 24 and/or 48 of post-trial (Fu) visits.

Less problematic substance use at the week 48 TAPIR trial visit was the only significant predictor of reaching adequate adherence post trial in the multivariable model of all participants with post-trial visits (Table 3). The multivariable model for near perfect adherence indicated that near perfect adherence at the week 48 TAPIR trial visit, and higher CalcR Scores at the week 48 TAPIR trial visit (indicative of higher sexual risk behavior), were significant predictors for near perfect adherence at the last post-trial visit (Table 3). In the multivariable model 4 (i.e. using study site as clustering variable) higher CalcR scores (aOR 14.02 per score point; p<0.001), less problematic substance use (aOR 0.69 per DAST10 score point; p<0.001), adequate adherence during week 48 of TAPIR (aOR 4.02; p<0.001) and longer enrollment into TAPIR (aOR 1.003; p=0.003) remained all significant predictors of adequate adherence at the last post-trial visit. In the multivariable model 5 (i.e. also using study site as clustering variable) higher CalcR scores (aOR 60.76 per score poin; p<0.001t), longer enrollment into TAPIR (aOR 1.004 per day; p<0.001), older age (aOR 1.04 per year; p<0.001), and absence of popper use (aOR 0.72 for popper use; p=0.008) remained all significant predictors of near-perfect adherence at the last post-trial visit.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariable binary Logistic Regression Models for predicting PrEP linkage plus adequate (Model 2) and near perfect PrEP adherence (Model 3) at the last post-trial visit where levels were measured among participants at all four participating centers.

| Variables for Predicting Post-Trial PrEP Adherence (n=122) | OR | 95% CI | p value | aOR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Model | Multivariable Model | |||||

| Model 2: Variables for Predicting Adequate PrEP Adherence at the last post-trial visit | ||||||

| Intervention Arm (i.e. receiving daily text messages for PrEP adherence | 0.897 | 0.435 – 1.851 | 0.769 | |||

| Study Site other than UCSD | 0.768 | 0.304 – 1.937 | 0.576 | |||

| Age (per year) | 1.016 | 0.979 – 1.053 | 0.401 | |||

| Non-Hispanic ethnicity | 1.333 | 0.528 – 3.368 | 0.543 | |||

| Higher Education category | 0.959 | 0.716 – 1.285 | 0.779 | |||

| Higher Income category | 1.059 | 0.861 – 1.304 | 0.587 | |||

| Duration on PrEP trial (per day) | 1.003 | 1.000 – 1.006 | 0.025 | - | - | n.s. |

| Adequate Adherence Week 48 PrEP trial Study visit | 4.063 | 1.019 – 16.20 | 0.047 | - | - | n.s. |

| Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST10; per score point) | 0.707 | 0.548 – 0.914 | 0.008 | 0.717 | 0.550 – 0.933 | 0.013 |

| Stimulant Substance Use | 0.800 | 0.363 – 1.759 | 0.578 | |||

| Non-stimulant Substance Use (alcohol, marijuana and poppers excluded) | 1.179 | 0.571 – 2.437 | 0.656 | |||

| Popper use | 1.110 | 0.537 – 2.296 | 0.778 | |||

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; per score point) | 0.974 | 0.909 – 1.043 | 0.447 | |||

| Calculated HIV risk score (CalcR) Month | 1.821 | 0.072 – 45.83 | 0.716 | |||

| Model 3: Variables for Predicting Near Perfect PrEP Adherence at the last post-trial visit# | ||||||

| Intervention Arm (i.e. receiving daily text messages for PrEP adherence | 1.427 | 0.654 – 3.316 | 0.351 | |||

| Study Site other than UCSD | 1.053 | 0.372 – 2.978 | 0.923 | |||

| Age (per year) | 1.039 | 0.998 – 1.082 | 0.060 | - | - | n.s. |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | 0.963 | 0.340 – 2.724 | 0.943 | |||

| Higher Education category | 0.854 | 0.609 – 1.198 | 0.361 | |||

| Higher Income category | 1.133 | 0.888 – 1.446 | 0.316 | |||

| Duration on PrEP trial (per day) | 1.004 | 1.000 – 1.008 | 0.073 | - | - | n.s. |

| Near perfect Adherence Week 48 PrEP trial Study visit | 6.221 | 2.412 – 16.04 | <0.001 | 5.711 | 2.160 – 15.10 | <0.001 |

| Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST10; per score point) | 0.830 | 0.622 – 1.108 | 0.206 | |||

| Stimulant Substance Use | 0.765 | 0.305 – 1.919 | 0.569 | |||

| Non-stimulant Substance Use (alcohol, marijuana and poppers excluded) | 0.877 | 0.386 – 1.992 | 0.754 | |||

| Popper use | 0.769 | 0.336 – 1.763 | 0.535 | |||

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; per score point) | 0.976 | 0.898 – 1.061 | 0.569 | |||

| Calculated HIV risk score (CalcR) Month | 21.283 | 0.708 – 639.5 | 0.078 | 98.444 | 1.261 – 7687 | 0.039 |

Multivariable model: Chi square 7.780; p=0.255 Hosmer Lemeshow; Forward Wald Binary Logistic Regression

Abbreviation: OR=odds ratio; aOR=adjusted odds ratio

In alternative models focusing only on those 95 participants who self-reported being on PrEP and therefore had DBS TFV-DP levels measured, adequate adherence at TAPIR week 48 was the only significant predictor of adequate adherence at the last post-trial visit. Similarly near perfect adherence at week 48 of TAPIR was the only predictor of near perfect adherence at the last post-trial visit (Supplementary Table 1).

Discussion

We followed PrEP users after completing a clinical PrEP trial to evaluate predictors of post-trial PrEP adherence in a well-characterized cohort of mostly MSM at risk for HIV acquisition. Two major findings are evident. First, adequate PrEP adherence was found frequently in those who completed ≥1 post-trial follow-up visits, and less problematic substance use and adequate PrEP adherence during the PrEP trial were the predictors of adequate adherence post-trial. Second, near-perfect adherence post-trial was found among those with higher sexual risk behavior and near-perfect PrEP adherence during the trial.

Overall, rates of follow-up post-trial varied widely between sites and reached 57% at UCSD. Those who did not complete post-trial visits at UCSD were younger, more likely randomized into the TAPIR intervention arm, had higher income, more problematic drug use, were more likely Hispanic, shorter follow-up duration in the TAPIR trial, and had lower adherence at week 48 of TAPIR. Only the latter three remained significant predictors in the multivariable model. Longer total TAPIR trial participation was the most important predictor for completing post-trial visits, indicating that longer duration of follow-up and study provided free PrEP during a trial may also increase post-trial study linkage. While PrEP linkage and adherence could not be assessed in participants not returning for follow-up visits, it could be hypothesized that PrEP linkage may have been lower among those not returning for follow-up visits. If that’s true, findings that Hispanic MSM were less likely to present for follow-up may be seen in line with previous reports. Hispanic MSM are disproportionately affected by the HIV epidemic, due to social and structural factors contributing to high-risk behaviors and limited PrEP use in real life settings (prescribed to only ~3% of Hispanic MSM who could benefit) 27,28,29. This is particularly true for young Hispanic MSM <25 years of age for which a 35% increase in new HIV diagnoses was observed in California from 2005–2013 30,31. Also previous reports from San Diego, where the majority of TAPIR participants were enrolled, indicate that Hispanic MSM were less likely to come back for follow-up visits after 3 to 6 months 32–34.

About 60% of participants who completed post-trial visits had adequate PrEP adherence. Depending on the model, either less problematic substance use or adequate adherence during the TAPIR trial were the only significant predictors of adequate adherence post-trial in the multivariable model.

MSM with problematic substance use often face important individual barriers (e.g. HIV-related stigma, substance use) and structural barriers (e.g. economic, healthcare) that may reduce linkage and adherence to PrEP 37–40. Importantly, substance use was not associated with lower PrEP adherence in the TAPIR trial 23. However, among participants who completed post-trial visits, problematic substance was a major predictor of not reaching adequate PrEP adherence, by mostly impacting the ability of participants to successfully link to PrEP providers post-study. In contrast, adequate adherence during the TAPIR trial was the only significant predictor of adequate adherence post-trial in those who were on PrEP. While the TAPIR text messaging intervention itself was not associated with higher adherence post-trial, this finding may nevertheless indicate that measures taken to enable participants’ adherence within a trial may have far reaching effects beyond trial roll-off. Near perfect adherence was observed in about half of those with adequate adherence post-trial, and best predicted by having near-perfect adherence during the TAPIR trial. The second significant predictor of near-perfect adherence post-trial was higher sexual risk behavior, indicating that those most at risk may have insight into their HIV risk and appropriately be diligent with PrEP adherence.

There are important limitations to this study, in particular the number of participants who completed post-trial visits. Given that the proportion of participants who completed post-trial visits varied widely between study sites, we had to focus our model on predictors of post-trial visits on UCSD participants only. There are a number of factors that went into this. UCSD may have had greater success with efforts to keep subjects engaged in follow up. The study site may also have been more convenient and less challenging to complete post study visits. It is possible that many individuals who did not attend post-study visits may not have continued PrEP after the study ended and therefore not interested in follow up. Multiple attempts were made to call individuals but many did not respond or did not give reason for nonparticipation. Also there are important limitations to note regarding our setting, where all study sites were located in one geographic area, and a subset of participants were already known to have higher adherence from the TAPIR study, making our setting different from other real-world settings. Finally, PrEP continuation and linkage was defined by participant self-report only, making this a less reliable outcome and preventing our study from detailed assessments of predictors of PrEP linkage.

In conclusion, PrEP users followed for up to 4 years had high rates of adequate adherence suggesting that PrEP can be used effectively by individuals for years. Follow-up post trial was predicted by longer trial enrollment, higher PrEP adherence during the trial and non-Hispanic ethnicity. Longer term adequate adherence was best predicted by having adequate adherence during the PrEP trial and less problematic substance use. Additional adherence monitoring and interventions measures may therefore be needed for those with low PrEP adherence during the first year and those with problematic substance use.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was primarily supported by the Gilead Sciences, Inc. Investigator Sponsored Research (IN-US-276-2122) two NIH pilot grants (AI036214 and DA026306), and a California HIV Research Program (CHRP) grant (EI11-SD-005). In addition, the work was partially supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI064086, MH081482, MH113477, MH062512, and AI106039).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Hoenigl received grant funding from Gilead.

Dr. Moore has been supported as a co-investigator on an educational grant from Gilead.

Dr. Anderson received research support from Gilead Sciences, paid to his institution.

Dr. Blumenthal received educational research funding from Gilead. She also has served as a Gilead PrEP advisor.

Dr. Morris receives research support from Gilead.

Other authors: no conflicts

References

- 1.Stecher M, Chaillon A, Eberle J, et al. Molecular epidemiology of the HIV epidemic in three german metropolitan regions - cologne/bonn, munich and hannover, 1999–2016. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):6799–018-25004–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoenigl M, Graff-Zivin J, Little SJ. Costs per diagnosis of acute HIV infection in community-based screening strategies: A comparative analysis of four screening algorithms. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(4):501–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stecher M, Hoenigl M, Eis-Hubinger AM, et al. Hotspots of transmission driving the local hiv epidemic in the cologne-bonn region, germany. Clin Infect Dis. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molina JM, Capitant C, Spire B, et al. On-demand preexposure prophylaxis in men at high risk for HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(23):2237–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu A, Glidden DV, Anderson PL, et al. Patterns and correlates of PrEP drug detection among MSM and transgender women in the global iPrEx study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67(5):528–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu AY, Hessol NA, Vittinghoff E, et al. Medication adherence among men who have sex with men at risk for HIV infection in the united states: Implications for pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014;28(12):622–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jenness SM, Goodreau SM, Rosenberg E, et al. Impact of the centers for disease control’s HIV preexposure prophylaxis guidelines for men who have sex with men in the united states. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(12):1800–1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson PL, Glidden DV, Liu A, et al. Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(151):151ra125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castillo-Mancilla JR, Morrow M, Coyle RP, et al. Tenofovir diphosphate in dried blood spots is strongly associated with viral suppression in individuals with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hojilla JC, Vlahov D, Glidden DV, et al. Skating on thin ice: Stimulant use and sub-optimal adherence to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(3):e25103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koss CA, Hosek SG, Bacchetti P, et al. Comparison of measures of adherence to human immunodeficiency virus preexposure prophylaxis among adolescent and young men who have sex with men in the united states. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(2):213–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landovitz RJ, Beymer M, Kofron R, et al. Plasma tenofovir levels to support adherence to TDF/FTC preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in MSM in los angeles, california. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;76(5):501–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zablotska IB, Vaccher SJ, Bloch M, et al. High adherence to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and no HIV seroconversions despite high levels of risk behaviour and STIs: The australian demonstration study PrELUDE. AIDS Behav. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker Z, Javanbakht M, Mierzwa S, et al. Predictors of over-reporting HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) adherence among young men who have sex with men (YMSM) in self-reported versus biomarker data. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(4):1174–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore DJ, Jain S, Dube MP, et al. Randomized controlled trial of daily text messages to support adherence to preexposure prophylaxis in individuals at risk for human immunodeficiency virus: The TAPIR study. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(10):1566–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasipanodya EC, Jain S, Sun X, et al. Trajectories and predictors of longitudinal preexposure prophylaxis adherence among men who have sex with men. J Infect Dis. 2018;218(10):1551–1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holloway IW, Tan D, Gildner JL, et al. Facilitators and barriers to pre-exposure prophylaxis willingness among young men who have sex with men who use geosocial networking applications in california. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2017;31(12):517–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoagland B, Moreira RI, De Boni RB, et al. High pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake and early adherence among men who have sex with men and transgender women at risk for HIV Infection: the PrEP Brasil demonstration project. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):21472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayer KH, Chan PA, R Patel R, Flash CA, Krakower DS. Evolving models and ongoing challenges for HIV preexposure prophylaxis implementation in the united states. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77(2):119–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosek SG, Rudy B, Landovitz R, et al. An HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Demonstration Project and Safety Study for Young MSM. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(1):21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoenigl M, Jain S, Moore D, et al. Substance use does not impact adherence in men who have sex with men on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;23:2289–2298. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: A cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(9):820–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castillo-Mancilla JR, Zheng JH, Rower JE, et al. Tenofovir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir diphosphate in dried blood spots for determining recent and cumulative drug exposure. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29(2):384–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blumenthal J, Jain S, Mulvihill E, et al. HIV risk perception among men who have sex with men (MSM):A randomized controlled trial. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez O, Wu E, Shultz AZ, et al. Still a hard-to-reach population? using social media to recruit latino gay couples for an HIV intervention adaptation study. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(4):e113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scott HM, Vittinghoff E, Irvin R, et al. Age, race/ethnicity, and behavioral risk factors associated with per contact risk of HIV infection among men who have sex with men in the united states. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65(1):115–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith DK, Van Handel M, Grey JA. BY RACE/ETHNICITY, BLACKS HAVE HIGHEST NUMBER NEEDING PrEP IN THE UNITED STATES, 2015. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections 2018;Abstract 83. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trends in new HIV diagnoses among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in california, 2005–2013. https://archive.cdph.ca.gov/programs/aids/Documents/MSMTrendsFactsheet.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoenigl M, Chaillon A, Morris SR, Little SJ. HIV infection rates and risk behavior among young men undergoing community-based testing in san diego. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoenigl M, Anderson CM, Green N, et al. Repeat HIV-testing is associated with an increase in behavioral risk among men who have sex with men: a cohort study. BMC Med 2015;13:218,015–0458-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin TC, Gianella S, Tenenbaum T, Little SJ, Hoenigl M. A Simple Symptom Score for Acute HIV Infection in a San Diego Community Based Screening Program. Clin Infect Dis. 2018; 67(1):105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.County of San Diego. HIV/AIDS epidemiology report 2015. San Diego: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mimiaga MJ, Closson EF, Kothary V, Mitty JA. Sexual partnerships and considerations for HIV antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis utilization among high-risk substance using men who have sex with men. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43(1):99–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Oldenburg CE, Mitty JA, Biello KB, et al. Differences in attitudes about HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis use among stimulant versus alcohol using men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(7):1451–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Escudero DJ, Kerr T, Wood E, et al. Acceptability of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PREP) among people who inject drugs (PWID) in a canadian setting. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(5):752–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guise A, Albers ER, Strathdee SA. ‘PrEP is not ready for our community, and our community is not ready for PrEP’: Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV for people who inject drugs and limits to the HIV prevention response. Addiction. 2016; 112: 572–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marshall BD, Milloy MJ. Improving the effectiveness and delivery of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to people who inject drugs. Addiction. 2016; 112: 580–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoenigl M, Chaillon A, Moore DJ, Morris SR, Smith DM, Little SJ. Clear links between starting methamphetamine and increasing sexual risk behavior: A cohort study among men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2016; 71: 551–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.