Abstract

Purpose:

We sought to examine the pharmacodynamic activation of the DNA damage response (DDR) pathway in tumors following anticancer treatment for confirmation of target engagement.

Experimental Design:

We evaluated the time course and spatial activation of 3 protein biomarkers of DNA damage recognition and repair (γH2AX, pS343-Nbs1, and Rad51) simultaneously in a quantitative multiplex immunofluorescence assay (IFA) to assess DDR pathway activation in tumor tissues following exposure to DNA-damaging agents.

Results:

Due to inherent biological variability, baseline DDR biomarker levels were evaluated in a colorectal cancer microarray to establish clinically-relevant thresholds for pharmacodynamic activation. Xenograft-bearing mice and clinical colorectal tumor biopsies obtained from subjects exposed to DNA damaging therapeutic regimens demonstrated marked intra-tumor heterogeneity in the timing and extent of DDR biomarker activation, due in part to the cell-cycle dependency of DNA damage biomarker expression.

Conclusions:

We have demonstrated the clinical utility of this DDR multiplex IFA in preclinical models and clinical specimens following exposure to multiple classes of cytotoxic agents, DNA repair protein inhibitors, and molecularly-targeted agents, in both homologous recombination-proficient and -deficient contexts. Levels exceeding 4% nuclear area positive (NAP) γH2AX, 4% NAP pS343-Nbs1, and 5% cells with ≥5 Rad51 nuclear foci indicate a DDR activation response to treatment in human colorectal cancer tissue. Determination of effect-level cutoffs allows for robust interpretation of biomarkers with significant inter-patient and intra-tumor heterogeneity; simultaneous assessment of biomarkers induced at different phases of the DNA damage response guards against the risk of false negatives due to an ill-timed biopsy.

Keywords: Immunofluorescence, pharmacodynamic assay, DNA damage repair, multiplex, cytotoxic chemotherapy

INTRODUCTION

Therapeutic agents that induce cell death by directly damaging DNA remain mainstays of cancer treatment. As new therapeutic agents enter the clinical arena and novel combination therapy approaches are explored, there is a growing need to monitor DNA damage repair (DDR) directly in patient tumors to provide proof of mechanism for novel agents, to evaluate potential causes of cytotoxic potentiation, as well as to understand differences in drug responses for individual patients (1). Assays of primary and secondary pharmacodynamic (PD) effect are particularly suited for these applications, because they can provide direct evidence of target engagement, unlike downstream markers of drug effect such as cellular apoptosis, which may predict drug response but do not clearly indicate a mechanism of action. With the renewed interest in epigenetic and DNA damaging agents for their ability to combine with immunotherapy, for example, it will be critical to know whether DNA damage occurred as predicted.

Establishing the PD response of DNA damage indicators, such as the biomarker of DNA double-stranded breaks histone H2AX phosphorylated at Ser139 (γH2AX) (2–5), in the preclinical setting can also guide the development of clinical drug administration and biomarker collection scheduling. Our experience, however, is that preclinical PD outcomes may not be fully recapitulated in clinical studies. Analysis of biopsies from patients with advanced solid tumors who received combination treatment with veliparib and irinotecan did not replicate the increase in γH2AX levels expected from preclinical modeling (6). In such cases, the discordance between preclinical and clinical observations could stem from numerous factors; notably, in most clinical trials only a single post-treatment tumor sampling is feasible. Hence, a difference of a few hours in collection time could substantively alter the likelihood of observing activation of certain biomarkers. Moreover, the induction of a given biomarker can be the result of signaling through multiple pathways, complicating the interpretation of its activation. For instance, while γH2AX is a strong indicator of DNA double-stranded breaks (DSB) and associated repair, it is also found during apoptosis-induced DNA fragmentation. Without using newer methods that distinguish these two outcomes, the interpretation of a γH2AX signal at later time points after drug treatment where either DNA repair or apoptosis may occur is difficult (7).

To expand the versatility and specificity of our measurements of DDR, we incorporated two additional biomarkers into our validated immunofluorescence assay (IFA) for γH2AX (4, 6). Nbs1 was selected due to its contribution to the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 (MRN) complex (critical for early DNA damage recognition, processing, and signaling), ATM recruitment to damage sites, double-strand break repair, and cell cycle checkpoint activation (8–11). The phosphorylation status of Nbs1 has been shown to dictate downstream repair choices between error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and error-free homologous recombination (HR) using homologous sister chromatids, in a cell cycle-dependent manner (12). ATM-dependent phosphorylation of Nbs1 at S343 occurs in response to DSB (13–15), making pS343-Nbs1 a valuable addition to our assay. Rad51, an essential component of the homologous recombination repair pathway, forms foci at DSB sites and can be quantified to measure DNA damage, repair, and homologous recombination pathway status (16–20). Rad51 has also recently emerged as a critical constituent in the process of replication fork reversal which protects these structures from degradation (21–23).

In this report, we establish the natural range of expression of pS343-Nbs1, Rad51, and γH2AX in colorectal cancer clinical specimens to define response thresholds for the individual biomarkers that must be exceeded to indicate a PD drug response. Furthermore, we demonstrate broad applicability of our novel multiplex IFA to characterize DDR pathway activation following genotoxic stress in cellular and mouse cancer models with and without HR deficiencies, using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) specimens that have been rapidly cryopreserved at the point of collection with a proven procedure for stabilizing phosphoprotein biomarkers (24). These results establish assay fitness-for-purpose, which revealed robust biomarker responses occurring over a time frame suitable for clinical implementation with tumor core biopsies, i.e., 4–6 h after drug administration, and confirm the usefulness of multiplexing DDR markers to guard against the risk of false negatives. Notably, we describe for the first time the phosphorylation of Serine-343 on Nbs1 in response to several classes of DNA-damaging agents other than ionizing radiation and irrespective of p53 or BRCA1 status, and observed substantial inter- and intra-tumor heterogeneity in DDR biomarker activation, which we attribute to asynchronous progression through the cell cycle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and reagents.

HT-29 human colon cancer, A375 human melanoma, A2780 ovarian cancer, A673 Ewing sarcoma, and HCT-116 colorectal carcinoma cell lines (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were grown in RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Lonza) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Lonza).

Primary antibody validation and conjugation.

All primary monoclonal antibodies (mAb) were purchased from commercial vendors: pS343-Nbs1 (rabbit mAb, Abcam), γH2AX (mouse mAb, Millipore), and Rad51 (rabbit mAb, Epitomics; mouse mAb, Novus Biologicals). Certificates of Analysis were provided for all antibodies. Antibodies were custom-conjugated to fluorescent dyes or haptens: anti-γH2AX-biotin (Millipore), anti-γH2AX to Alexa Fluor 790, anti-pS343-Nbs1 to Digoxigenin (DIG) and anti-Rad51 to Dinitrophenol (DNP) (Molecular Probes, Inc.). New and previously qualified lots of antibodies were compared side-by-side. Validation details can be found in the Supplemental Methods and Supplemental Figs. S1 and S2, and in LoRusso, et al. for pS343-Nbs1 (6). Cell cycle and apoptosis antibodies used were: p21 Waf1/Cip1 (12D1), cyclin B1 (D5C10), p-histone H3-Ser 10 (rabbit mAb, Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA), cyclin B1-Alexa-647 (rabbit mAb, [EPR17060] Abcam), geminin (mouse mAb, Abcam), and cleaved caspase-3 rabbit antibody (R&D Systems).

Drug-treated animal models.

Athymic nu/nu mice were implanted with A375 (topotecan-responsive), A673, HCT-116, or A2780 cells as previously described (4,25). A375 xenograft quadrants were collected from mice 4 h after intraperitoneal administration of vehicle (sterile water) or 4.7 mg/kg topotecan. The maximum tolerated dose (MTD) for topotecan administered to mice once daily for 5 consecutive days (QDx5) is 4.7 mg/kg/day (4,26,27). A673 xenograft quadrants were collected from mice following intraperitoneal administration of vehicle (saline) or 240 mg/kg gemcitabine at 2, 4, 7, 12, 24 or 52 h after one dose. HCT-116 xenografts were collected from mice following oral administration of vehicle (saline) or clofarabine (60 mg/kg) at 24 h after the first dose on a 5xQ2D schedule; or following intraperitoneal administration of vehicle (saline), 2 mg/kg 5-aza-T-dCyd (NSC 777586) or 0.75 mg/kg decitabine (NSC 127716) on treatment day 11 following 10 doses on the schedule QDx5, rest 2 days, QDx5, rest 9 days. A2780 xenografts were collected from mice following intraperitoneal administration of vehicle (saline) or 6 mg/kg cisplatin (NSC 119875) at 4, 7, or 24 h after one dose. Samples were fixed in neutral-buffered formalin, and paraffin-embedded as previously described (4).

NCI-Frederick is accredited by AAALAC International and follows the Public Health Service Policy for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Animal care was provided in accordance with the procedures outlined in the “Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (National Research Council; 1996; National Academy Press; Washington, D.C.), and all studies were conducted under an approved Animal Care and Use Committee protocol. Mice were housed in sterile, filter-capped, polycarbonate cages (Allentown Caging) in a barrier facility on a 12 h light/dark cycle, and provided with sterilized food and water, ad libitum. Prior to drug treatment, the animals were randomized into groups using a commercial software program (Study Director, Studylog Systems, Inc.). See Supplemental Methods for handling of the human colon patient-derived xenografts.

Human tumor biopsies.

Pairs of 18-gauge core needle tumor biopsies were collected from metastatic sites in patients with advanced disseminated disease refractory to prior therapy and enrolled in early phase clinical trials conducted by the National Cancer Institute’s Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis (DCTD) and Center for Cancer Research at the NIH Clinical Center, Bethesda, MD. Biopsies were obtained before and 5 days after the initiation of treatment, and analyzed for levels of DDR biomarkers γH2AX, pS343-Nbs1, and Rad51 using the quantitative IFA validated for use on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded human tissue described below. All patients gave written informed consent for study participation. Study design and conduct complied with all applicable regulations, guidances, and local policies, and the study was approved by the NCI institutional review board. Biopsies were placed in pre-chilled cryogenic vials, snap-frozen within 2 minutes of collection, and stored at ≤ –80 °C. Biopsies were fixed and paraffin blocked together with a biomarker-positive control tissue for sectioning, following DCTD standard operating procedures (http://dctd.cancer.gov/ResearchResources/ResearchResources-biomarkers.htm).

Tissue microarrays containing colonic or rectal adenocarcinoma and normal tissue adjacent to tumor were obtained from Indivumed GmbH (Hamburg, Germany). Tissue was derived from tumor resections, and ischemia times were less than 5 minutes until fixation in formalin or snap-freezing, with the exception of two tumor fragments that had ischemia times of 6 and 9 minutes. Formalin fixed tissue cores were paraffin-embedded and supplied as blocks or tissue sections on slides.

Multiplex immunofluorescence staining.

The method used for staining FFPE tissue sections was modified from our previously described Bond-max™ Autostainer Staining protocol (4); detailed Bond-max System (Leica Microsystems) methods can be obtained from the manufacturer. Two formats of γH2AX (clone JBW301) antibody were used. Either a biotin-conjugated γH2AX antibody, which was detected with the use of Streptavidin labeled with Alexa Fluor 660, or a γH2AX‒Alexa Fluor 790 custom conjugated antibody was used. Custom conjugated pS343-Nbs1-DIG and Rad51-DNP antibodies were detected with the use of Alexa Fluor 546- or Alexa Fluor-647 IgG Fraction Monoclonal Mouse Anti-Digoxin (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated anti-Dinitrophenyl-KLH Rabbit IgG Antibody fraction, (DNP-488) (ThermoFisher). After staining with a cocktail of all 3 primary antibodies, followed by washing and staining with the secondary reporting antibodies (see Supplemental Methods for details), the slides were rinsed in 1X PBS and blotted to remove excess liquid. Slides were cured overnight with Prolong Gold Antifade Reagent (Invitrogen) in the dark and imaged the following day. For long-term storage, slides were stored in the dark at –20 °C. For images used in assay development, slides were stained with individual antibodies using a method similar to the method above without the use of conjugated primary mAb. Confocal images (12-bit) were acquired at 20X using a Nikon A1 scan head on a Nikon 90i microscope at 0.24 μm/pixel, and 20X widefield images (14-bit) were acquired in the 790 nM channel using an Andor DU888 EMCDD camera at 0.65 μm/pixel.

Quantitative Biomarker Analysis.

To restrict DDR-IFA analysis to primarily tumor cells, Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E)-stained 5 μm sections from each biopsy or tissue microarray were annotated for areas of viable tumor by a pathologist, and this annotation was used to choose DDR-IFA image analysis fields on neighboring slides. Fields from at least 2 different slides and a minimum of 3000 cells were required for each analysis. Definiens Architect XD Tissue Studio IF (Version 2.4.2.; Build 40013) software program was used for analysis of biomarker expression, co-expression (within the same cell), and nuclear enumeration. Definiens Tissue Studio software was used to quantify the changes in nuclear biomarker expression by two methods: nuclear area positive (NAP) analysis (defined by the Area of the Marker mask divided by the Area of the Nuclear Mask) for biomarkers displaying diffuse nuclear expression (γH2AX and pS343-Nbs1), or foci count per nucleus for biomarkers exhibiting distinct nuclear foci. See the Supplemental Methods and Supplemental Figures S3, S4, and S5 for quantitation details. Quantitation was performed by cell enumeration based on a positive/negative cutoff for background fluorescence in each channel, for each image.

Statistical analysis.

Descriptive statistics including mean, standard deviation (SD), standard error of the mean (SEM), and Student’s t-test were conducted with Microsoft Excel. The significance level for the 95% confidence interval (CI) was set at α = 0.05 for a two-sided Student’s t-test.

RESULTS

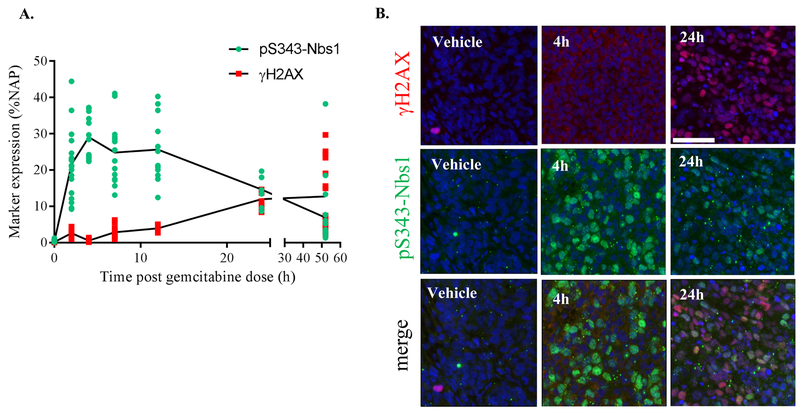

Contrasting kinetics of pS343-Nbs1 and γH2AX responses to gemcitabine in vivo

While characterizing the time course of the DNA damage response in a Ewing’s sarcoma xenograft model derived from A673 cells, an histology with known sensitivity to the cytotoxic cytidine analogue gemcitabine (28,29), we noted a 24 h delay in the induction of the DSB biomarker γH2AX in response to a single dose (at the mouse MTD—240 mg/kg) of gemcitabine (Figs. 1A and 1B). In contrast, robust induction of pS343-Nbs1 was detected within 2 h of treatment, and the signal was sustained for at least 24 h. The earlier induction of pS343-Nbs1 is concordant with its role in early DNA damage recognition, end processing, and signaling. As for γH2AX, its later activation is consistent with the mechanism of action of gemcitabine, which irreversibly inhibits ribonucleotide reductase leading to stalled replication forks and S-phase arrest, and eventually causes replication fork collapse and emergence of DSBs (30,31). The complementarity of the time-frames for pS343-Nbs1 and γH2AX induction in this model suggests a solution to the issue of selecting a single timepoint for clinical biopsy collection to assess the pharmacodynamic effects of drug treatment. Assessing biomarkers that are induced at different phases of the DNA damage response helps to ensure that a poorly timed biopsy will not result in a falsely negative PD signal. Therefore, we developed a multiplex quantitative IFA assay to assess the induction of γH2AX, pS343-Nbs1, and Rad51 in patient specimens to assist with pharmacodynamics-driven development of cancer therapeutics that damage DNA. Importantly, our characterization of pS343-Nbs1 established that it is induced in response to different classes of DNA damaging agents including gemcitabine, topotecan, cisplatin, and ionizing radiation, irrespective of p53 or BRCA1 status (Supplemental Figs. S4A–S4C). As expected, pS343-Nbs1 was not activated by agents that do not directly induce DNA damage such as the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (Supplemental Fig. S4D).

Figure 1. Timing of the activation of pS343-Nbs1, and γH2AX in response to gemcitabine in vivo.

(A) Analysis of gemcitabine-treated A673 Ewing sarcoma xenograft samples from 2, 4, 7, 12, 24 and 52 h after one dose gemcitabine (240 mg/kg). % Nuclear area positive (NAP) was measured for pS343-Nbs1 and γH2AX on co-stained slides. Marker expression per field is plotted. (B) Representative images showing pS343-Nbs1 (green), γH2AX (red), and DAPI (blue).

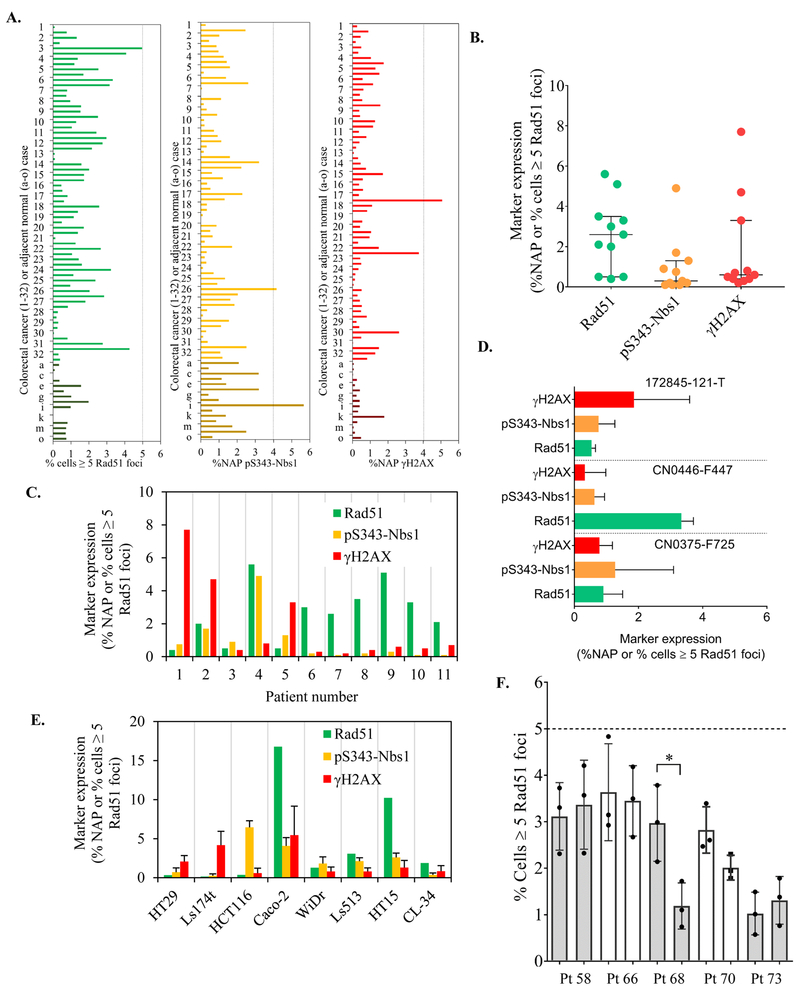

Biological baseline variability in human tumor specimens and determination of cutoff values for establishing a PD biomarker response

The DDR-IFA staining procedure for γH2AX, pS343-Nbs1, and Rad51 was developed to allow the use of both direct and indirect reporter methods, as described in Supplemental Materials and Methods. Baseline biological variability was established for each biomarker across 64 individual cores from 32 colorectal (CRC) tumor resections contained in a paraffin-embedded colorectal tissue microarray (TMA; Indivumed, Hamburg, Germany). The TMA also included 15 cores of normal tissue found adjacent to cancer. A comparison of the normal colorectal tissues and CRC tumor tissues showed that the DNA biomarkers had largely overlapping expression ranges, allowing us to pool the normal and tumor tissues for the purpose of establishing the biological baseline variability for colorectal tissue (Fig. 2A). The individual tissue cores analyzed had a minimum of 66 and maximum of 7,346 cells available for DDR-IFA analysis (median 1,657; mean 1,887) with cell counts in the normal tissue generally lower than those in the tumor tissue. At least 500 individual nuclei were analyzed for biomarker expression in greater than 95% of the cores, and ≥1000 individual cells were analyzed in 88% of the cores.

Figure 2. Baseline expression of DDR markers and establishment of response cutoff values.

(A) Baseline expression of selected DDR markers was demonstrated and quantified in a colorectal tissue array with 32 tumors (2 cores per case are included) and 15 normal colon tissues. At least 500 individual tumor nuclei were quantified in 95% of the tissue microarray cores. (B-C) Baseline marker quantitation in advanced stage colorectal cancers from patients enrolled in Phase 1 clinical trials at NCI. Median expression and inter-quantile range is indicated for each marker. A minimum of 4,000 individual tumor nuclei were quantitated across at least two nonadjacent slides per biopsy specimen. (D) Baseline expression in human colon adenocarcinoma patient-derived xenografts. At least 5,000 nuclei quantified per model. (E) Baseline expression of selected DDR markers was demonstrated and quantified in 8 colorectal cancer cell lines. Over 1000 individual nuclei were quantified for each cell line. (F) Inter-lesion baseline Rad51 quantitation from patients with advanced stage cancers with two biopsies each collected from the same lesion. *p< 0.05. The dashed line represents our empirically determined baseline value cutoff of 5% of cells ≥ 5 Rad51 foci per nucleus.

To this dataset we also added DDR-IFA baseline data from 11 baseline core needle biopsies collected before initiation of protocol therapy from patients at the NCI Developmental Therapeutics Clinic with advanced-stage colon or colorectal cancer (Figs. 2B and 2C), for a total of 90 human colorectal tissue specimens. The tumor content of these biopsies was evaluated by pathologist review and a minimum of 4,000 individual tumor nuclei were quantitated across at least two nonadjacent sections to ensure a representative sampling of each tumor biopsy. More cells were analyzed for each core needle biopsy specimen than for each specimen in the TMA because more tissue was available; however, we found the biomarker expression ranges from both groups were in good agreement. A 95% cutoff value was then determined for each biomarker from the pooled TMA (tumor and normal tissue) cores and core-needle biopsies so PD response in colorectal cancer could be defined as a biomarker value that exceeded biological baseline variability to allow small but significant biomarker inductions by drugs with unknown mechanisms to be measured. For this dataset of 90 individual colorectal tissues, 95% of the specimens had baseline values below 4% NAP for γH2AX, 4% NAP for pS343-Nbs1, and 5% of cells positive for Rad51 signal (measured as ≥5 foci per nucleus). These values did not change when tissues with less than 500 nuclei were excluded from the analysis.

We further assessed the variability of DDR biomarker baseline values in 3 independent patient-derived xenograft models of colon cancer origin (172845–121-T, CN0446-F447, and CN0375-F725) to determine whether the threshold values established above applied to models of this disease. The baseline values for all 3 biomarkers also fell below the 95% cutoff value established with the TMA (Fig. 2D). However, the DDR-IFA revealed DDR biomarker expression to be higher and more variable in 8 colon cancer cell lines compared to human tissue (Fig. 2E). These findings may not be surprising given the well-established differences between in vitro models and tumor tissue. The critical nature of understanding the baseline variability in interpreting clinical results is shown in a study of duplicate pre-treatment biopsies analyzed for Rad51 (Fig. 2F). Ten biopsies from 5 patients were analyzed, with each of the duplicate biopsies per patient derived from the same tumor lesion. In all cases the mean Rad51 signal measured across 3 sections fell below the effect-level cutoff of 5% Rad51 baseline expression, and in most cases the baseline values were not significantly different from each other. However, in patient 68 we did observe significantly different Rad51 expression between the duplicates, demonstrating that biological variability of baseline values alone could lead to misinterpretation of a change as a drug effect if an effect-level cutoff is not established. To avoid misinterpretations stemming from baseline heterogeneity, we use the expression cutoffs established here, rather than a comparison to baseline values, to more reliably define DDR biomarker activation for all colorectal cancers and derived tissues. Similar studies may be needed to define effect-level cutoffs in other cancer types.

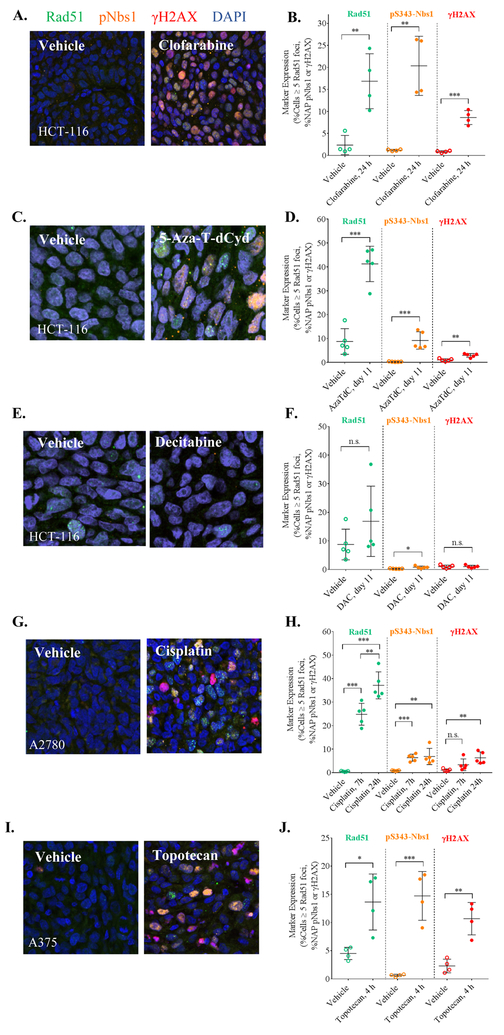

Assessment of DDR activation in vivo and across drug classes

We assessed the newly established effect-level thresholds of the PD biomarker responses of relevant in vivo models in a time frame consistent with clinical sampling. We analyzed tumor quarters from mice bearing human tumor xenografts (4–5 per group) pre- and post-treatment with a panel of approved and investigational anti-cancer agents using the DDR multiplex assay (Fig. 3). A minimum of 10,000 cells per treatment group were analyzed. A single 60 mg/kg dose of the purine nucleoside antimetabolite clofarabine, which slows the growth of HCT-116 xenografts but does not cause tumor regression (25), caused significant induction of all 3 biomarkers (24 h after one dose; **p< 0.01 for Rad51 and pS343-Nbs1 and ***p< 0.001 for γH2AX; Figs. 3A–3B). Similarly, treatment with 2 mg/kg of the DNA hypomethylating nucleoside analog 5-aza-4’-thio-2’-deoxycytidine (5-aza-T-dCyd), a therapeutic dose (tumor volumes did not double during 2 full cycles of treatment and the optimum treatment-to-control ratio of tumor volumes [T/C] was 12%), produced induction of all 3 biomarkers 24 h after the tenth dose (***p< 0.001 for Rad51 and pS343-Nbs1 and **p< 0.01 for γH2AX; Figs. 3C–3D). In contrast, treatment with the nucleic acid synthesis inhibitor decitabine (Figs. 3E–3F), which induces only tumor growth delay in HCT-116 xenografts (with a time-to-tumor-volume-doubling of 6 days and an optimum T/C of 44%), caused a modest increase in pS343-Nbs1 (*p< 0.05) 24 h after the tenth dose (0.75 mg/kg), which did not exceed the expected 4% NAP cut-off.

Figure 3. DDR multiplex is broadly applicable across classes of different genotoxic therapeutic agents in vivo.

Representative immunofluorescence images showing the induction of DDR markers in a variety of xenograft models treated with different genotoxic agents: (A) 60 mg/kg clofarabine Q2Dx5, (C) 2 mg/kg 5-aza-T-dCyd (AzaTdC) QDx5 with 2-day rest, and (E) 0.75 mg/kg decitabine (DAC) QDx5 with 2-day rest in HCT-116 colon xenografts; (G) single 6 mg/kg dose of cisplatin in A2780 ovarian; and (I) 4.7 mg/kg topotecan QDx5 in A375 melanoma xenografts. Resolution: 20X confocal, 0.24 μm/pixel. Corresponding changes in DDR marker expression are shown in (B, D, F, H, J), and the timing of xenograft sampling is indicated on the x-axes. Although all 3 markers are significantly activated by treatment with the 5 agents, at the cellular level, DDR expression varies widely. Statistical significance for the difference in marker expression levels between vehicle-treated and drug-treated xenografts corresponds to *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001.

A2780 ovarian cancer xenografts treated with 6 mg/kg of the DNA crosslinking agent cisplatin, a dose that causes moderate tumor growth delay (32), showed significant induction of Rad51 and pS343-Nbs1 but not γH2AX within 7 h of treatment; Rad51 expression further increased between 7 h and 24 h (**p < 0.01). After 24 h of treatment, all three biomarkers were significantly induced (Figs. 3G–3H). Furthermore, analysis of A375 xenografts 4 h after treatment with 4.7 mg/kg topotecan revealed a significant increase in the percentage of cells positive for Rad51 (*p< 0.05) in addition to the significant induction of pS343-Nbs1 (***p< 0.001) and γH2AX (**p< 0.01) (Figs. 3I–3J). This biomarker response was associated with a dose of topotecan (4.7 mg/kg) that causes tumor regression in this model (4). γH2AX and pS343-Nbs1 expression was also examined at a lower dose of topotecan (0.5 mg/kg), which does not cause tumor regression but does elicit a moderate biomarker response and therefore serves as the minimum biologically effective dose that produces a change in the PD biomarkers that are distinguishable from the non-treated control group (4) (Supplemental Fig. S6).

DDR activation in the context of homologous recombination defects

Although the same systematic evaluation of baseline DDR biomarker expression levels has not yet been carried out in ovarian and melanoma tissue arrays, the similar pattern of DDR biomarker activation observed in xenografts derived from HCT-116 colon, A2780 ovarian cancer, and A375 melanoma cell lines suggests that this DDR assay can be generally applied to the monitoring of PD responses to DNA damaging agents regardless of tumor type. We have also observed the DDR assay to report target engagement in differing genetic backgrounds, such as severe homologous recombination defects (HRD). For example, in an MX-1 breast carcinoma xenograft model containing a frameshift in BRCA1 that results in a truncated protein at residue 999 and two BRCA2 nonsynonymous SNPs that have been described in cases of familial breast cancer (N289H and N991D) (33), we observed similar baseline levels of the 3 DDR biomarkers and significant (***p<0.001) drug-induced Rad51 and pS343-Nbs1 inductions in response to irinotecan doses too low to inhibit xenograft growth (Supplemental Figs. S7A–B). In another case, an in vitro experiment with 1 μM cisplatin in isogenic UWB1.289 +/−BRCA1 ovarian carcinoma cells displayed similar expression of the DDR biomarkers in the two genetic backgrounds, with statistically significant (*p<0.05) induction of all three biomarkers after 24 hours of treatment (Supplemental Figs. S7C–D). Further studies are required to determine whether DDR baseline variability is higher in HRD tumors compared to HR-competent tumors, but the results to date demonstrate that background HRD do not preclude the induction of the 3 DDR-IFA biomarkers.

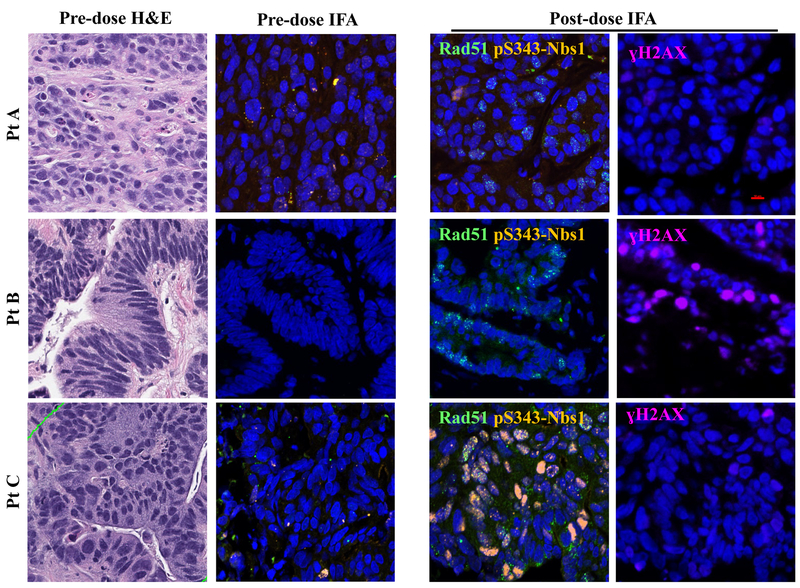

Clinical readiness

To establish the translational potential of measuring aspects of the DDR in the clinic, we applied the DDR multiplex panel to the analysis of 18-gauge tumor biopsies taken from liver metastases in three patients with colon cancer before and after 5 days of treatment with an investigational, DNA damaging drug regimen (NCT01851369) consisting of the DNA damaging agent temozolomide co-administered with the experimental DDR inhibitor TRC102 on days 1–5 of a 28-day cycle (Fig. 4). Despite the similarities in the diagnoses, site and timing of biopsies, drug regimen, lack of clinical response (all 3 patients came off study within the first 2 cycles of treatment), and negligible pre-dose biomarker levels, each patient’s post-treatment biopsy displayed a distinct pattern of DDR biomarker induction. All three patients had ≤2% of cells positive for Rad51 at baseline; Rad51 levels were induced well above the effect level cutoff of 5% (11%, 7% and 17% for Patients A, B & C, respectively) after 5 days of treatment. However, the patients differed in induction of pS343-Nbs1 and γH2AX. After treatment, patient B displayed a 14% NAP γH2AX signal, and patient C had 11% NAP pS343-Nbs1, both values above the established 4% NAP effect-level threshold. Overall, the induction of the DDR biomarkers was measurable using this multiplex biomarker panel, proving the feasibility of using this assay on clinical specimens.

Figure 4. Heterogeneous DDR marker activation in clinical colorectal cancer specimens.

Representative H&E and immunofluorescence (IFA) images from 3 patients with advanced colorectal cancer enrolled in NCI trial NCT01851369 before and 5 days after start of treatment with a DNA damaging therapeutic regimen consisting of TCR102 plus temozolomide administered orally once daily. Red scale bar represents 10 μm.

DDR heterogeneity and the role of cell cycle

Across our in vivo experiments (Fig. 3) and in the 3 colon cancer patient specimens (Fig. 4), we observed heterogeneous patterns of DDR biomarker activation within individual cells and across tissues: a portion of cells expressed a single DDR biomarker, some expressed multiple biomarkers simultaneously, and some expressed none of the DDR biomarkers. Because DNA damage responses are intimately related to the cell cycle, we investigated whether the expression of DDR-IFA biomarkers could be tied to distinct cell cycle phases. To this end, we measured the G1/S cell cycle arrest biomarker p21 (34), the G2 biomarker cytoplasmic cyclin B1 (35), the mitosis biomarker phospho-S10-histone-H3 (pHH3), and the S-phase through early M-phase indicator geminin (36) in p53- and BRCA1/2-proficient A375 xenografts treated with 4.7 mg/kg topotecan at 4 h, which caused significant induction of all three DDR biomarkers (Figs. 3B and 5A). Topotecan-treated tumors displayed a significant increase in nuclear p21 expression, indicative of p53-dependent, DNA damage-induced G1/S arrest (from 1.0% NAP at baseline to 12.9% NAP after treatment; ***p< 0.001), along with a decrease in cells in G2 and mitosis compared to vehicle control as indicated by the decreased number of cells expressing cytoplasmic cyclin B1 (from 5.1% to 2.3%; *p< 0.05) or chromatin-associated pHH3 (from 2.2% to 0.2%; ***p< 0.001; Fig. 5A–B) respectively. No change was seen in geminin expression, likely because IFA thresholding was set to capture all geminin-expressing cells, irrespective of signal intensity (Fig. 5B).

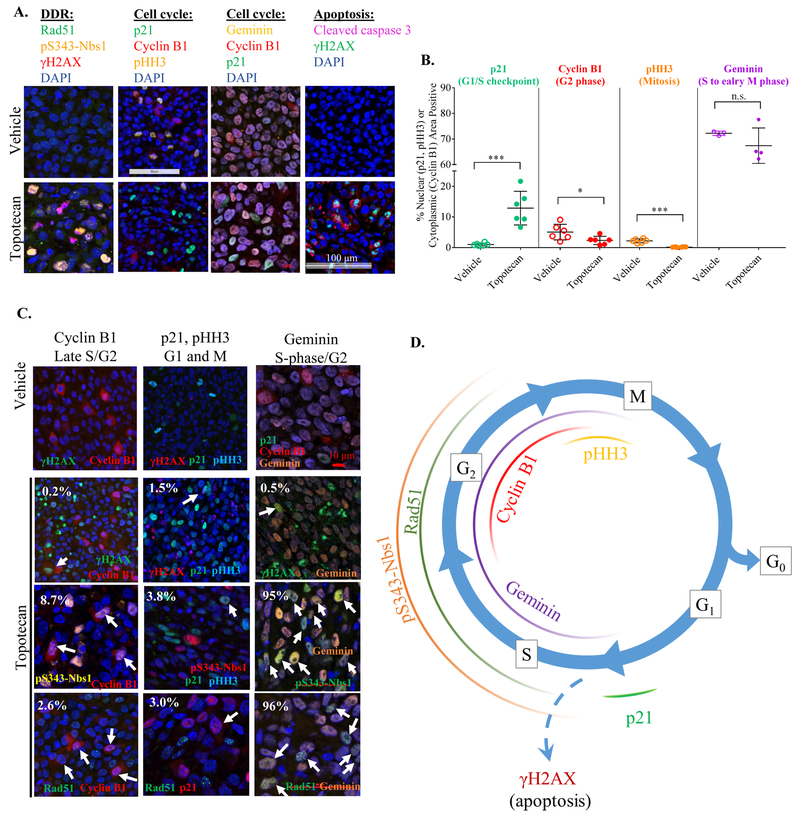

Figure 5. DNA damage marker expression in a cell cycle–dependent manner contributes to heterogeneous DDR response.

(A) Representative immunofluorescence images showing expression of DAPI, DDR markers (Rad51, pS343-Nbs1, γH2AX), cell cycle markers (p21, cyclin B1, pHH3, geminin), and apoptosis markers (cleaved caspase 3 and γH2AX) in vehicle- and topotecan-treated A375 xenografts (4.7 mg/kg). (B) Quantitated expression of cell cycle markers p21, cyclin B1, pHH3, and geminin pre- and post-topotecan treatment (4.7 mg/kg). (C) Co-expression of cell cycle markers and DDR markers. White arrows point out yellow co-localization of pS343-Nbs1/geminin cells and Rad51/geminin-positive cells. The percentage of cells expressing the combination of markers indicated is provided on each slide. There was no colocalization observed of any DDR marker with pHH3 so numbers in middle panel reflect p21 co-localization with each DNA repair biomarker. The white bar represents 90 μm. Red bar 50 μm. (D) Schematic illustration of the effects of topotecan on the activation of DDR and cell cycle markers derived from the A375 xenograft experiments 4 h after a single 4.7 mg/kg dose of topotecan.

Co-localization data for the cell cycle biomarkers and DDR-IFA biomarkers showed that the vast majority of pS343-Nbs1 and Rad51 colocalized with cyclin B1 and geminin but not with p21 (Fig. 5C, 3rd and 4th row, respectively), clearly indicating these biomarkers are activated during S and G2 phases and not at G1 arrest. The role of Rad51 in homologous recombination is well known, and it has also more recently been identified as an important component of replication fork reversal, associated with chemotherapy resistance (21–23); its expression during S-phase and G2 is expected and agrees with in vitro experiments (Supplemental Fig. S8). Interestingly, the lack of co-localization between pS343-Nbs1and p21 suggests that pS343-Nbs1 does not play a significant role in G1 arrest, but rather is active in DNA damage repair mechanisms in the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, with cyclin B1 co-expressed in 8.7% of pS343-Nbs1-expressing cells, and geminin co-expressed in 95% of pS343-Nbs1-expressing cells. In contrast, γH2AX did not markedly colocalize with any of the cell cycle biomarkers (Fig. 5C, 2nd row), but approximately 20% of the γH2AX-positive cells also displayed cleaved caspase-3 blebs, a biomarker of apoptosis (37) (Fig. 5A). It is well-established that γH2AX is a biomarker of both DNA damage and apoptosis and that co-localization of γH2AX with cytoplasmic cleaved caspase-3-positive blebbing identifies the apoptotic cells (37–39). The γH2AX positive cells seen in these samples also display visible chromatin condensation and fragmentation, consistent with them being apoptotic cells. We summarize the heterogeneous DDR-IFA expression pattern observed in vivo in A375 xenografts treated with topotecan in Fig. 5D.

DISCUSSION

Pharmacodynamic (PD) biomarkers are critical in early drug development to ensure that a drug’s mechanism of action can be understood, and can provide evidence of target engagement when developing administration schedules and rational combinations of drug types. PD biomarkers of DNA damage response are somewhat unusual in that they could either be indicative of cells overwhelmed by DNA damage or actively involved in repairing DNA damage following exposure to a DNA-damaging agent; therefore, while the detection of these PD biomarkers provides definitive evidence of drug activity and target engagement, they may not be predictive of overall drug response. In the studies described here, we have demonstrated the importance of using PD biomarkers to understand the variability in the activation of the DNA damage response both with respect to specific drug classes and the timing of individual DNA repair events following drug treatment. The multiplex approach enables measurement of several analytes in a single clinical specimen, maximizing the amount of information from small core needle biopsies. Multiplexing also reduces the possibility of missing a PD response due to specimen timing, dose schedule, or genetic alterations in the tumor (compared to a single biomarker readout). For instance, the lack of modulation at a given time point in a single analyte assay could be wrongly interpreted as either no drug effect or a genetic defect that prevents modulation of the target, a risk that can be circumvented by multiplexing (40). The importance of this approach is illustrated by the treatment of A673 xenografts with gemcitabine (Fig. 1), in which measurable γH2AX levels were found at a much later time point than induction of pS343-Nbs1. Because clinical biopsies are usually collected at a single time point after drug administration, the use of a multiplex assay increases the probability of detecting a reliable PD biomarker signal, which could be used to refine tumor sampling times and assessment of drug mechanism of action. While the 3 PD biomarkers included in our multiplex (γH2AX, pS343-Nbs1, and Rad51) are most commonly associated with the sensing and repair of DSBs, Rad51 also provides a readout of replication fork stalling as a result of single strand breaks (21–23), making the DDR-IFA useful for interpreting whether prolonged replication fork stalling or single strand break induction results in induction of DSBs in particular genetic backgrounds.

We also performed an extensive study of baseline levels of each DDR biomarker across 90 colon/colorectal human tissue specimens, 11 colorectal cancer core-needle biopsies, 3 patient-derived xenografts, and 8 colon cancer cell lines. These evaluations examined the biological range of DDR biomarker expression and determined cutoff values that must be exceeded to conclude that a PD response has occurred (Fig. 2). These efforts revealed small but significant variations in the baseline expression of the biomarkers, not only between specimens from patients with the same histology, but also between individual needle biopsies from the same lesion (Fig. 2F). In the latter example, two baseline biopsies from the same lesion in the same patient had significantly different Rad51 expression (Pt 68 in Fig. 2F, *p< 0.05). This is especially important when reporting small increases in biomarker expression in first-in-human clinical trials that are testing novel investigational agents where no prior clinical data exists, and PD biomarker responses are being interpreted for the first time. Similar findings were also apparent with pS343-Nbs1 and γH2AX based on the differences in paired tumor tissues (Fig. 2A). Differences in biomarker baseline values are the major limitation to reporting percent increases in PD biomarker values in human specimens and are often underappreciated. Our efforts to evaluate baseline expression of all three DDR biomarkers in colorectal tissue facilitated the determination of specific cutoff values below which 95% of baseline measurements fall; we could then confidently distinguish a small drug response from normal baseline variability in this tissue type. This approach is superior to the current method of reporting only a proportional increase, which may erroneously identify small increases from a very low baseline level as a meaningful PD response. Unfortunately, this approach is not yet standard because it requires access to high quality tissue from the tumor type in question and resources to quantify thousands of high content images of human tissues. However, the concordance of DDR biomarker activation patterns between the histologies that we investigated—colorectal and ovarian cancer, and melanoma—add confidence to the broader applicability of colorectal TMA-derived baseline levels (Fig. 3). In the future, we will extend the evaluation of Rad51, pS343-Nbs1, and γH2AX baseline expression levels to additional histologies.

Through extensive preclinical modeling using empirically determined cutoff values, we demonstrated biomarker responses to multiple DNA damaging agents (Fig. 3 and Supplemental Fig. S5). These experiments provided critical data required to determine whether each assay had sufficient dynamic range and was fit for the purpose of measuring PD drug responses affecting the DDR pathway in vivo. However, preclinical xenograft studies are more easily interpreted than clinical studies due to the ability to compare drug- to vehicle-treated groups in statistically significant samples of animals with homogeneous genetic backgrounds. In clinical specimens, which generally involve smaller samples and greater heterogeneity than preclinical models, the use of multiple biomarkers for the same pathway increases the chance of observing a PD signal and provides more flexibility in interpreting the PD outcome. We have illustrated this point in Fig. 4, in which we demonstrate significantly different DDR biomarker activation patterns in three clinical specimens from colorectal cancer patients receiving the same DNA damaging drug treatment, biopsied at the same time following therapy. Although the drug treatment increased Rad51 levels in all three patient specimens, the γH2AX and pS343-Nbs1 drug responses varied, underscoring the strength of the multiplex approach.

It is known that DSB repair is cell-cycle dependent and occurs at the earliest stage following a cytotoxic injury (34,41–43). This is important for the interpretation of our DDR biomarker determinations and provides insight into the mechanisms of action of the investigational agents the biomarkers are used to evaluate. Because our IFA multiplex technique allowed the visualization and localization of the biomarker signal across a large tumor cell population in the tissue sampled, without tissue extraction (44), we could identify distinct cellular sub-populations within tumors based on biomarker expression patterns, reflecting the relationship of the DDR response to cell cycle phases. Our data demonstrate the cell cycle-dependent expression of DDR markers in response to topotecan treatment (Fig. 5), and may help to explain heterogeneous responses to this and other therapeutic agents that produce DNA damage. Specifically, we noted that cells arrested at the G1/S checkpoint (as indicated by p21 expression) did not substantially colocalize with any of the three DDR biomarkers quantified in our assay, and appeared mainly as DAPI-only stained nuclei in DDR-IFA staining images (Figs. 5A and 5C). Lack of DDR marker expression in this population may reflect the protective effect of the G1/S checkpoint, preventing progression into S-phase and accumulation of DNA damage. Prolonged G1/S arrest may lead to a p53/p21 pathway-induced apoptosis, consistent with our observation of an increase in γH2AX-expressing cells. Co-expression analysis of DDR and cell cycle biomarkers in future studies may allow for greater understanding of drug activity and biomarker effect within a cell cycle context and may be particularly informative for the development of drug combinations in which specific cell cycle phases are targeted.

In summary, we have found that multiple markers of DDR can be evaluated concomitantly in vivo following treatment with a variety of different cancer therapeutic agents that damage DNA, and that the variability of the baseline expression of these DDR biomarkers in human colon cancers, although not inconsequential, permits the clinical quantification of the effects of multiple classes of DNA damaging oncologic drugs on the DDR pathway. Furthermore, we suggest that the heterogeneous nature of the response to these drugs in the clinic may, in part, be due to cell-to-cell, cycle-dependent variations in the capacity of the tumor to repair DNA.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance.

Nuclear proteins γH2AX, pS343-Nbs1, and Rad51 are critical components of the cellular DNA damage response (DDR). We demonstrate in this study that a panel of these three biomarkers can usefully assess the cellular pharmacodynamic (PD) response, needed for establishing mechanism of action and developing drug administration schedules, to multiple classes of DNA-damaging therapeutic agents. We also determined natural baseline levels and variation of these biomarkers in tumor specimens from 43 patients undergoing initial surgery for colorectal cancer, thereby establishing effective threshold levels of activation for each biomarker. Quantitation of the DDR using a multiplex immunofluorescence assay (IFA) for γH2AX, pS343-Nbs1, and Rad51 permits simultaneous evaluation of multiple PD responses, which helps increase the likelihood of observing PD responses that can vary between individuals based on biopsy timing, drug and dose studied, and the genetic background of the patient.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Rachel Andrews, Victor Lonsberry, Brad Gouker, Lindsay Dutko and Donna Butcher, Leidos Biomedical Research, Inc., for their technical contribution to histology efforts. We thank Dr. Yvonne A. Evrard, Suzie Borgel, John Carter, Ray Divelbliss, Les Stotler and Debbie Trail, Leidos Biomedical Research, Inc., and Michelle Ahalt-Gottholm, Biological Testing Branch, NCI, for their technical contributions to in vivo xenograft experiments. We thank Drs. Katherine Ferry-Galow and Priya Balasubramanian, Leidos Biomedical Research, Inc., and Dr. Joe Tomaszewski for valuable discussion. We thank Drs. Mariam Konaté, Kelly Government Services, and Andrea Regier Voth, Leidos Biomedical Research, Inc., for writing support in the preparation of this manuscript.

Financial Support: This research was funded in part by American Recovery and Reinvestment Act funds and in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under Contract No. HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: none

REFERENCES

- 1.Ivashkevich A, Redon CE, Nakamura AJ, Martin RF, Martin OA. Use of the gamma-H2AX assay to monitor DNA damage and repair in translational cancer research. Cancer Lett 2012;327:123–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Redon CE, Nakamura AJ, Zhang YW, Ji JJ, Bonner WM, Kinders RJ, et al. Histone gammaH2AX and poly(ADP-ribose) as clinical pharmacodynamic biomarkers. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:4532–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang LH, Pfister TD, Parchment RE, Kummar S, Rubinstein L, Evrard YA, et al. Monitoring Drug-Induced γH2AX as a Pharmacodynamic Biomarker in Individual Circulating Tumor Cells. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:1073–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinders RJ, Hollingshead M, Lawrence S, Ji J, Tabb B, Bonner WM, et al. Development of a validated immunofluorescence assay for gammaH2AX as a pharmacodynamic marker of topoisomerase I inhibitor activity. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:5447–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Redon CE, Nakamura AJ, Sordet O, Dickey JS, Gouliaeva K, Tabb B, et al. gamma-H2AX detection in peripheral blood lymphocytes, splenocytes, bone marrow, xenografts, and skin. Methods Mol Biol 2011;682:249–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LoRusso PM, Li J, Burger A, Heilbrun LK, Sausville EA, Boerner SA, et al. Phase I Safety, Pharmacokinetic, and Pharmacodynamic Study of the Poly(ADP-ribose) Polymerase (PARP) Inhibitor Veliparib (ABT-888) in Combination with Irinotecan in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:3227–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogakou EP, Nieves-Neira W, Boon C, Pommier Y, Bonner WM. Initiation of DNA fragmentation during apoptosis induces phosphorylation of H2AX histone at serine 139. J Biol Chem 2000;275:9390–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee AY-L, Liu E, Wu X. The Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1 Complex Plays an Important Role in the Prevention of DNA Rereplication in Mammalian Cells. J Biol Chem 2007;282:32243–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Difilippantonio S, Celeste A, Kruhlak MJ, Lee Y, Difilippantonio MJ, Feigenbaum L, et al. Distinct domains in Nbs1 regulate irradiation-induced checkpoints and apoptosis. J Exp Med 2007;204:1003–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu X, Ranganathan V, Weisman DS, Heine WF, Ciccone DN, O’Neill TB, et al. ATM phosphorylation of Nijmegen breakage syndrome protein is required in a DNA damage response. Nature 2000;405:477–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deshpande RA, Lee JH, Arora S, Paull TT. Nbs1 Converts the Human Mre11/Rad50 Nuclease Complex into an Endo/Exonuclease Machine Specific for Protein-DNA Adducts. Mol Cell 2016;64:593–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rai R, Hu C, Broton C, Chen Y, Lei M, Chang S. NBS1 Phosphorylation Status Dictates Repair Choice of Dysfunctional Telomeres. Mol Cell 2017;65:801–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim DS, Kim ST, Xu B, Maser RS, Lin J, Petrini JH, et al. ATM phosphorylates p95/nbs1 in an S-phase checkpoint pathway. Nature 2000;404:613–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gatei M, Young D, Cerosaletti KM, Desai-Mehta A, Spring K, Kozlov S, et al. ATM-dependent phosphorylation of nibrin in response to radiation exposure. Nat Genet 2000;25:115–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao S, Weng YC, Yuan SS, Lin YT, Hsu HC, Lin SC, et al. Functional link between ataxia-telangiectasia and Nijmegen breakage syndrome gene products. Nature 2000;405:473–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krejci L, Altmannova V, Spirek M, Zhao X. Homologous recombination and its regulation. Nucleic Acids Res 2012;40:5795–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birkelbach M, Ferraiolo N, Gheorghiu L, Pfaffle HN, Daly B, Ebright MI, et al. Detection of impaired homologous recombination repair in NSCLC cells and tissues. J Thorac Oncol 2013;8:279–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graeser M, McCarthy A, Lord CJ, Savage K, Hills M, Salter J, et al. A marker of homologous recombination predicts pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in primary breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:6159–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engelke CG, Parsels LA, Qian Y, Zhang Q, Karnak D, Robertson JR, et al. Sensitization of pancreatic cancer to chemoradiation by the Chk1 inhibitor MK8776. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:4412–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mukhopadhyay A, Elattar A, Cerbinskaite A, Wilkinson SJ, Drew Y, Kyle S, et al. Development of a functional assay for homologous recombination status in primary cultures of epithelial ovarian tumor and correlation with sensitivity to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:2344–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zellweger R, Dalcher D, Mutreja K, Berti M, Schmid JA, Herrador R, et al. Rad51-mediated replication fork reversal is a global response to genotoxic treatments in human cells. J Cell Biol 2015;208:563–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mijic S, Zellweger R, Chappidi N, Berti M, Jacobs K, Mutreja K, et al. Replication fork reversal triggers fork degradation in BRCA2-defective cells. Nat Commun 2017;8:859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quinet A, Lemacon D, Vindigni A. Replication Fork Reversal: Players and Guardians. Mol Cell 2017;68:830–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Srivastava AK, Hollingshead MG, Weiner J, Navas T, Evrard YA, Khin SA, et al. Pharmacodynamic Response of the MET/HGF Receptor to Small-Molecule Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Examined with Validated, Fit-for-Clinic Immunoassays. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:3683–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holbeck SL, Camalier R, Crowell JA, Govindharajulu JP, Hollingshead M, Anderson LW, et al. The National Cancer Institute ALMANAC: A Comprehensive Screening Resource for the Detection of Anticancer Drug Pairs with Enhanced Therapeutic Activity. Cancer Res 2017;77:3564–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bookman MA, Malmstrom H, Bolis G, Gordon A, Lissoni A, Krebs JB, et al. Topotecan for the treatment of advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: an open-label phase II study in patients treated after prior chemotherapy that contained cisplatin or carboplatin and paclitaxel. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:3345–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rowinsky EK, Grochow LB, Hendricks CB, Ettinger DS, Forastiere AA, Hurowitz LA, et al. Phase I and pharmacologic study of topotecan: a novel topoisomerase I inhibitor. J Clin Oncol 1992;10:647–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goss KL, Gordon DJ. Gene expression signature based screening identifies ribonucleotide reductase as a candidate therapeutic target in Ewing sarcoma. Oncotarget 2016;7:63003–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goss KL, Koppenhafer SL, Harmoney KM, Terry WW, Gordon DJ. Inhibition of CHK1 sensitizes Ewing sarcoma cells to the ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor gemcitabine. Oncotarget 2017;8:87016–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montano R, Khan N, Hou H, Seigne J, Ernstoff MS, Lewis LD, et al. Cell cycle perturbation induced by gemcitabine in human tumor cells in cell culture, xenografts and bladder cancer patients: implications for clinical trial designs combining gemcitabine with a Chk1 inhibitor. Oncotarget 2017;8:67754–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson R, Eastman A. The cancer therapeutic potential of Chk1 inhibitors: how mechanistic studies impact on clinical trial design. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2013;76:358–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plumb JA, Strathdee G, Sludden J, Kaye SB, Brown R. Reversal of drug resistance in human tumor xenografts by 2’-deoxy-5-azacytidine-induced demethylation of the hMLH1 gene promoter. Cancer Res 2000;60:6039–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donawho CK, Luo Y, Luo Y, Penning TD, Bauch JL, Bouska JJ, et al. ABT-888, an orally active poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor that potentiates DNA-damaging agents in preclinical tumor models. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:2728–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.el-Deiry WS, Harper JW, O’Connor PM, Velculescu VE, Canman CE, Jackman J, et al. WAF1/CIP1 is induced in p53-mediated G1 arrest and apoptosis. Cancer Res 1994;54:1169–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clute P, Pines J. Temporal and spatial control of cyclin B1 destruction in metaphase. Nat Cell Biol 1999;1:82–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wohlschlegel JA, Kutok JL, Weng AP, Dutta A. Expression of geminin as a marker of cell proliferation in normal tissues and malignancies. Am J Pathol 2002;161:267–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dull AB, Wilsker D, Hollingshead M, Mazcko C, Annunziata CM, LeBlanc AK, et al. Development of a quantitative pharmacodynamic assay for apoptosis in fixed tumor tissue and its application in distinguishing cytotoxic drug-induced DNA double strand breaks from DNA double strand breaks associated with apoptosis. Oncotarget 2018;9:17104–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu C, Zhu F, Cho YY, Tang F, Zykova T, Ma WY, et al. Cell apoptosis: requirement of H2AX in DNA ladder formation, but not for the activation of caspase-3. Mol Cell 2006;23:121–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harada A, Matsuzaki K, Takeiri A, Mishima M. The predominant role of apoptosis in gammaH2AX formation induced by aneugens is useful for distinguishing aneugens from clastogens. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen 2014;771:23–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marrero A, Lawrence S, Wilsker D, Voth AR, Kinders RJ. Translating pharmacodynamic biomarkers from bench to bedside: analytical validation and fit-for-purpose studies to qualify multiplex immunofluorescent assays for use on clinical core biopsy specimens. Semin Oncol 2016;43:453–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Orthwein A, Noordermeer SM, Wilson MD, Landry S, Enchev RI, Sherker A, et al. A mechanism for the suppression of homologous recombination in G1 cells. Nature 2015;528:422–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 42.Shaltiel IA, Krenning L, Bruinsma W, Medema RH. The same, only different - DNA damage checkpoints and their reversal throughout the cell cycle. J Cell Sci 2015;128:607–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou BB, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: putting checkpoints in perspective. Nature 2000;408:433–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manning CF, Bundros AM, Trimmer JS. Benefits and Pitfalls of Secondary Antibodies: Why Choosing the Right Secondary Is of Primary Importance. PLoS One 2012;7:e38313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.