Abstract

Background

The management of complex orthopedic infections usually includes a prolonged course of intravenous antibiotic agents. We investigated whether oral antibiotic therapy is noninferior to intravenous antibiotic therapy for this indication.

Methods

We enrolled adults who were being treated for bone or joint infection at 26 U.K. centers. Within 7 days after surgery (or, if the infection was being managed without surgery, within 7 days after the start of antibiotic treatment), participants were randomly assigned to receive either intravenous or oral antibiotics to complete the first 6 weeks of therapy. Follow-on oral antibiotics were permitted in both groups. The primary end point was definitive treatment failure within 1 year after randomization. In the analysis of the risk of the primary end point, the noninferiority margin was 7.5 percentage points.

Results

Among the 1054 participants (527 in each group), end-point data were available for 1015 (96.3%). Treatment failure occurred in 74 of 506 participants (14.6%) in the intravenous group and 67 of 509 participants (13.2%) in the oral group. Missing end-point data (39 participants, 3.7%) were imputed. The intention-to-treat analysis showed a difference in the risk of definitive treatment failure (oral group vs. intravenous group) of −1.4 percentage points (90% confidence interval [CI], −4.9 to 2.2; 95% CI, −5.6 to 2.9), indicating noninferiority. Complete-case, per-protocol, and sensitivity analyses supported this result. The between-group difference in the incidence of serious adverse events was not significant (146 of 527 participants [27.7%] in the intravenous group and 138 of 527 [26.2%] in the oral group; P = 0.58). Catheter complications, analyzed as a secondary end point, were more common in the intravenous group (9.4% vs. 1.0%).

Conclusions

Oral antibiotic therapy was noninferior to intravenous antibiotic therapy when used during the first 6 weeks for complex orthopedic infection, as assessed by treatment failure at 1 year. (Funded by the National Institute for Health Research; OVIVA Current Controlled Trials number, ISRCTN91566927.)

Complex bone and joint infections are typically managed with surgery and a prolonged course of treatment with intravenous antibiotic agents.1,2 The preference for intravenous antibiotics reflects a broadly held belief that parenteral therapy is inherently superior to oral therapy,3 a view supported by an influential 1970 article that suggested that “… osteomyelitis is rarely controlled without the combination of careful, complete surgical debridement and prolonged (four to six weeks) parenteral antibiotic therapy … .” 4 However, intravenous therapy is associated with substantial risks, inconvenience, and higher costs than oral therapy.5,6 A meta-analysis involving 180 patients with chronic osteomyelitis, 118 of whom were followed for more than 1 year, showed no advantage of intravenous therapy over oral therapy, but there was insufficient evidence to draw conclusions with potential clinical utility.7 We therefore conducted a pragmatic noninferiority trial to evaluate outcomes at 1 year after intravenous therapy as compared with oral therapy administered during the initial 6 weeks of treatment for orthopedic infection.

Methods

Trial Design and Participants

Oral versus Intravenous Antibiotics for Bone and Joint Infection (OVIVA) was a multicenter, open-label, parallel-group, randomized, controlled non-inferiority trial. Blinding was not used, because we considered it unethical to expose participants in the oral group to the risks associated with prolonged courses of intravenously administered placebo. The methodologic details of the trial, summarized below, are presented in detail in the published protocol,8 which is also available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org. The trial was approved by the U.K. National Research Ethics Committee South Central. The first, second, and last authors wrote the first draft of the manuscript. The authors vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and for the fidelity of the trial to the protocol.

Eligible participants were older than 18 years of age, provided written informed consent, and, in the attending physician’s opinion, would ordinarily have been treated with 6 weeks of intravenous antibiotic therapy for one of the following acute or chronic bone or joint infections: native osteomyelitis of the extraaxial skeleton, native joint infection requiring excision arthroplasty, prosthetic joint infection, orthopedic fixation-device infection, or vertebral osteomyelitis with or without associated diskitis or soft-tissue infection.

Randomization and Interventions

The statistician prepared a concealed, computer-generated, 1:1 randomization list, using variably sized permuted blocks, with participants stratified according to center. Randomization was performed by trained staff members using a centralized assignment system.

Participants began their randomly assigned treatment strategy as soon as possible (but no more than 7 days) after definitive surgical intervention or, if the infection was being managed conservatively, the start of antibiotic therapy. Antibiotics were selected by accredited infection specialists with such factors as local epidemiology, antimicrobial susceptibility, bioavailability, previous infections, contraindications, allergies, and drug interactions taken into account; the choice of antibiotic was therefore assumed to be the most appropriate therapy for each participant.

In the intravenous group, adjunctive oral agents such as rifampin were permitted at the infection specialist’s discretion, reflecting usual practice.9 In the oral group, up to 5 consecutive days of intravenous antibiotics were allowed for unrelated intercurrent infections. Antibiotics administered before definitive treatment, as well as follow-on therapy beyond 6 weeks, were permitted in both groups but were not governed by the trial protocol.

Assessments, Objectives, and End Points

Clinical assessments and patient-reported outcome measures were recorded at enrollment and at days 42, 120, and 365. Adherence to treatment was assessed at days 14 and 42.

The primary end point was definite treatment failure within 1 year after randomization, defined as the presence of at least one clinical criterion (draining sinus tract arising from bone or prosthesis or the presence of frank pus adjacent to bone or prosthesis), microbiologic criterion (phenotypically indistinguishable bacteria isolated from two or more deep-tissue samples or a pathogenic organism from a single closed aspirate or biopsy), or histologic criterion (presence of characteristic inflammatory infiltrate or microorganisms). All potential primary end-point events, which were identified by local active surveillance during follow-up, were subsequently categorized by an end-point committee of three independent specialists who were unaware of the trial-group assignments. The members of the committee determined the category of each event by consensus. There were four categories, which were based on predefined criteria: uninfected, possible treatment failure, probable treatment failure, or definite treatment failure (see the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org).

Secondary end points were probable or possible treatment failure, early discontinuation of the randomly assigned treatment strategy, intravenous catheter complications, Clostridium difficile–associated diarrhea, serious adverse events, resource use, health status (measured with the three-level version of the European Quality of Life–5 Dimensions [EQ-5D-3L]),10 the Oxford Hip and Knee Scores,11 and adherence to treatment (based on the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale [scores range from 0 to 8, with higher scores indicating better adherence] or the Medication Event Monitoring System12,13).

Statistical Analysis

The sample size of 1050 participants was based on a 5% anticipated rate of treatment failure (the rate that was observed during a single-center pilot study), a 5-percentage-point noninferiority margin on the absolute risk difference scale (corresponding to a relative difference of 100%), with a one-sided alpha level of 0.05, 90% power, and 10% loss to follow-up. The 5-percentage-point noninferiority margin was based on a consensus among a wide range of researchers, infectious-disease specialists, and orthopedic surgeons and balanced the potential risks and benefits of oral therapy. In February 2015, after 601 participants had undergone randomization in the multicenter trial, a planned interim analysis showed an overall failure rate of approximately 12.5%. The original 5-percentage-point margin was consequently considered too restrictive and therefore, by consensus, the investigators adjusted the noninferiority margin to 7.5 percentage points on the absolute risk difference scale (corresponding to a 60% relative difference) with approval from the trial steering committee, data and safety monitoring committee, and ethics committee. Further information is provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

In the primary intention-to-treat analysis, proportions of participants with definite treatment failure at 1 year were compared with the use of multiple imputation by chained equations for missing end-point data.14 Noninferiority was met if the upper limit of two-sided 90% confidence interval around the unadjusted absolute difference in risk (i.e., the risk in the oral group minus the risk in the intravenous group) was less than 7.5 percentage points (in accordance with the sample-size calculation). Two-sided 95% confidence intervals were also estimated. The modified intention-to-treat analysis included only the participants with complete end-point data. The per-protocol analysis included only participants who received at least 4 weeks of their randomly assigned treatment. For sensitivity analyses, missing end-point data were replaced by treatment failure in the oral group and success in the intravenous group. An exploratory Bayesian analysis (in the modified intention-to-treat population) was used to assess robustness to the noninferiority margin.

Continuous end points were analyzed with the use of adjusted quantile regression or rank-sum tests. Categorical data were compared with the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Subgroup analyses for definitive treatment failure considered point estimates and 95% confidence intervals rather than the 7.5-percentage-point non-inferiority margin. Prespecified subgroup analyses were performed for baseline diagnostic certainty, surgical procedure, infecting pathogen, the antibiotic that the clinician had intended to prescribe (excluding rifampin) before randomization, and clinician-specified intention specifically for adjunctive rifampin. Post hoc subgroup analyses were performed for metal retention, identified pathogen (as compared with culture-negative) infection, use of local antibiotics, and peripheral vascular disease. Subgroup analyses were considered supplementary and were not adjusted for multiple testing. All analyses were performed with Stata software, version 14SE (StataCorp).

Results

Participants

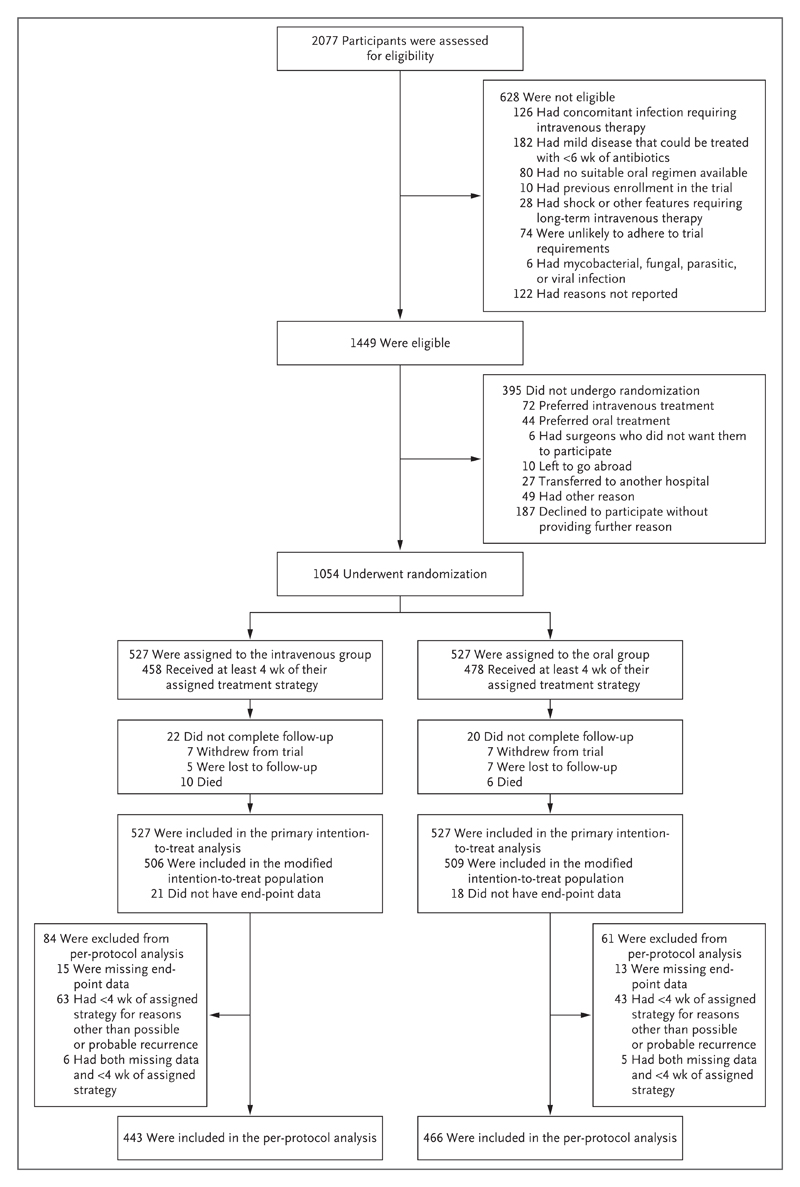

We recruited 1054 participants (including 228 from the single-center internal pilot study) across 26 U.K. sites (median, 8 participants per site; interquartile range, 4 to 24) between June 2010 and October 2015. Of the 42 participants who did not complete follow-up, 39 had no end-point data recorded; the modified intention-to-treat analysis therefore included 1015 participants. The per-protocol analysis included 909 participants (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Enrollment, Randomization, and Follow-up.

The participants were well matched with regard to baseline characteristics (Table 1, and Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix); 639 of the 1054 participants (60.6%) had metalware-related infection, and 80 (7.6%) were treated without surgical intervention. The baseline diagnosis of infection was determined on the basis of clinical findings in 558 of 1054 participants (52.9%) and, in cases in which samples were submitted, on the basis of microbiologic findings in 802 of 1003 participants (80.0%) and histologic findings in 543 of 636 (85.4%). Additional details are provided in Table S1A in the Supplementary Appendix. Investigators and an independent assessment committee with members who were unaware of the treatment-group assignments used predefined criteria, detailed in the Supplementary Appendix, to determine diagnostic certainty at baseline: 954 participants (90.5%) had definite infection, 23 (2.2%) had probable infection, and 76 (7.2%) had possible infection (data were unavailable for 1 participant).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Trial Participants.*.

| Characteristic | Intravenous Group (N = 527) |

Oral Group (N = 527) |

Total (N = 1054) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age — yr | |||

| Median (interquartile range) | 61 (49–70) | 60 (49–70) | 60 (49–70) |

| Range | 18–92 | 18–91 | 18–92 |

| Male sex — no. (%) | 320 (60.7) | 358 (67.9) | 678 (64.3) |

| Baseline surgical procedure — no. (%) | |||

| No implant or device present; débridement of chronic osteomyelitis performed | 153 (29.0) | 169 (32.1) | 322 (30.6) |

| No implant or device present; débridement of chronic osteomyelitis not performed | 25 (4.7) | 29 (5.5) | 54 (5.1) |

| Débridement and implant retention | 124 (23.5) | 123 (23.3) | 247 (23.4) |

| Removal of orthopedic device for infection | 89 (16.9) | 78 (14.8) | 167 (15.8) |

| Prosthetic joint implant removed | 68 (12.9) | 67 (12.7) | 135 (12.8) |

| Prosthetic joint implant, one-stage revision | 47 (8.9) | 43 (8.2) | 90 (8.5) |

| Surgery for diskitis, spinal osteomyelitis, or epidural abscess; débridement performed | 8 (1.5) | 5 (0.9) | 13 (1.2) |

| Surgery for diskitis, spinal osteomyelitis, or epidural abscess; débridement not performed | 13 (2.5) | 13 (2.5) | 26 (2.5) |

| Deep-tissue histologic result — no. (%) | |||

| Infected | 266 (50.5) | 277 (52.6) | 543 (51.5) |

| Equivocal | 13 (2.5) | 17 (3.2) | 30 (2.8) |

| Uninfected | 31 (5.9) | 32 (6.1) | 63 (6.0) |

| Not done or missing† | 217 (41.2) | 201 (38.1) | 418 (39.7) |

| Microbiologic diagnostic sampling — no. (%) | |||

| Two or more samples positive for same organism | 357 (67.7) | 338 (64.1) | 695 (65.9) |

| Two or more samples taken but only one positive for a given pathogenic organism | 20 (3.8) | 32 (6.1) | 52 (4.9) |

| Only one sample taken, which was found to be positive for a pathogenic organism by closed biopsy | 25 (4.7) | 30 (5.7) | 55 (5.2) |

| Two or more samples taken but only one positive for a given nonpathogenic organism | 21 (4.0) | 25 (4.7) | 46 (4.4) |

| Sampling undertaken but no organisms identified | 77 (14.6) | 78 (14.8) | 155 (14.7) |

| Not done or missing‡ | 27 (5.1) | 24 (4.6) | 51 (4.8) |

| Organisms identified — no./total no. (%)§ | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 196/500 (39.2) | 182/503 (36.2) | 378/1003 (37.7) |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococcus | 137/500 (27.4) | 135/503 (26.8) | 272/1003 (27.1) |

| Streptococcus species | 72/500 (14.4) | 73/503 (14.5) | 145/1003 (14.5) |

| Pseudomonas species | 28/500 (5.6) | 23/503 (4.6) | 51/1003 (5.1) |

| Other gram-negative organisms | 84/500 (16.8) | 84/503 (16.7) | 168/1003 (16.7) |

| Culture negative | 77/500 (15.4) | 78/503 (15.5) | 155/1003 (15.5) |

There was no significant difference between the groups for any variable shown other than sex (P = 0.02). Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding. Additional baseline characteristics are shown in Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix.

For 409 participants (212 in the intravenous group and 197 in the oral group), no tissue samples were submitted for histologic examination; for 9 participants (5 in the intravenous group and 4 in the oral group), the results of histologic analysis were missing.

For 42 participants (22 in the intravenous group and 20 in the oral group), no tissue samples were submitted for microbiologic examination; for 9 participants (5 in the intravenous group and 4 in the oral group), the results of microbiologic analysis were missing.

More than one option was possible: 153 participants had polymicrobial infection with two organisms, and 28 had polymicrobial infection with three or more organisms; 45 isolates were not in the listed subgroups.

Route and Duration of Antibiotic Therapy

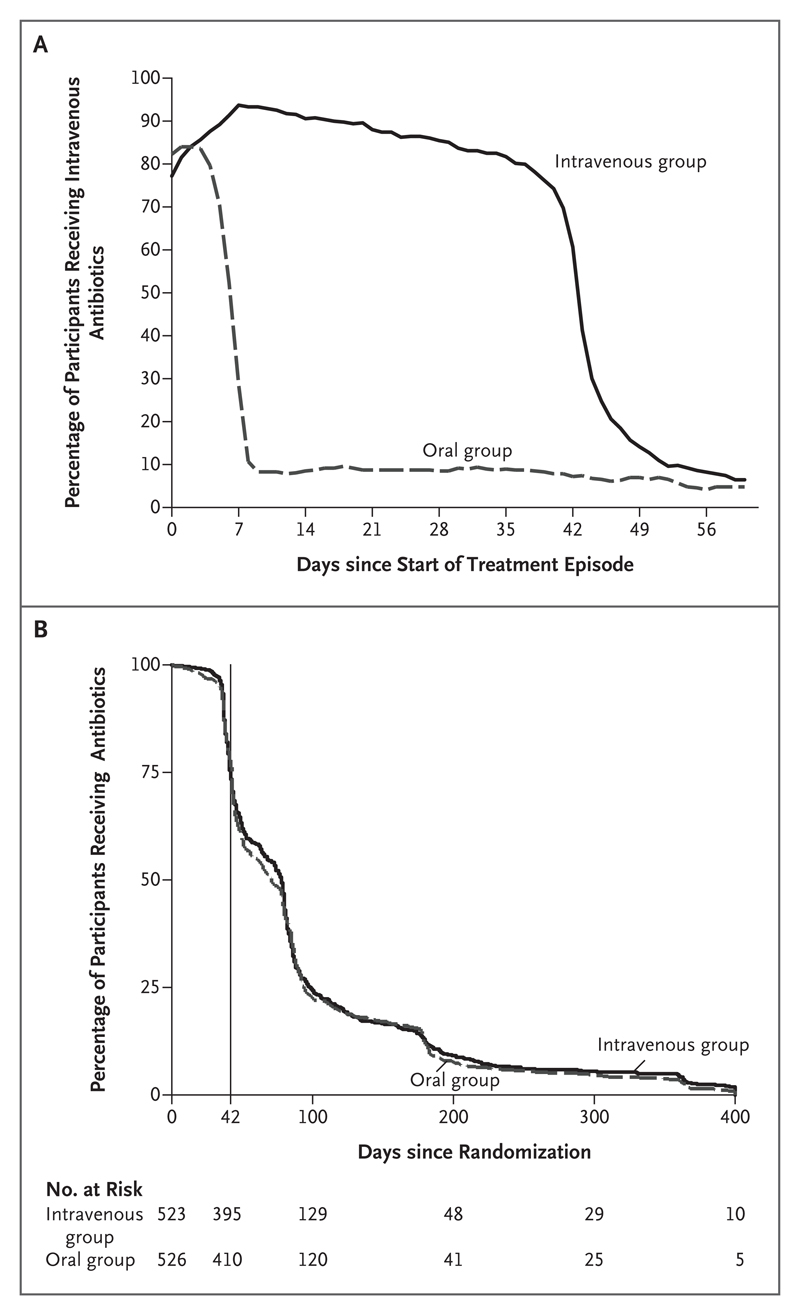

Most participants (93.3% of those in the intravenous group and 89.3% of those in the oral group) began their randomly assigned treatment regimen within 7 days after surgery or the start of antibiotic therapy. In the intravenous group, the percentage of participants receiving intravenous therapy declined slowly and then fell substantially at 6 weeks, reflecting planned treatment changes. Over the same period, approximately 10% of the participants in the oral group were receiving intravenous therapy at any time (Fig. 2A). Antibiotic therapy was continued beyond 6 weeks for 805 of 1049 participants (76.7%); the median total duration of therapy was 78 days (interquartile range, 42 to 99) in the intravenous group and 71 days (interquartile range, 43 to 94) in the oral group (P = 0.63) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Route and Duration of Antibiotic Therapy.

Panel A shows the percentage of participants receiving intravenous antibiotics from the start of the treatment episode (i.e., the date of definitive surgery or, if surgery was not performed, the start of planned curative antibiotic therapy) through day 60. Participants who had been randomly assigned to receive oral therapy and received intravenous therapy were doing so because they were prescribed intravenous antibiotics for up to 5 days for an intercurrent infection unrelated to the incident orthopedic infection (permitted by the protocol); were unable or unwilling to take oral therapy for any reason (secondary end point); were, subsequent to randomization, considered to have no suitable oral options for antibiotic therapy on the basis of emerging susceptibility results (secondary end point); or had had a potential treatment failure (primary end point). Most participants who had been randomly assigned to receive intravenous therapy but were receiving oral therapy over the same period were doing so because of a failure of intravenous access (secondary end point). Panel B shows the percentage of participants receiving any antibiotic through the final follow-up. The vertical line indicates 6 weeks after the start of treatment (i.e., the end of the intervention period).

Primary Analysis

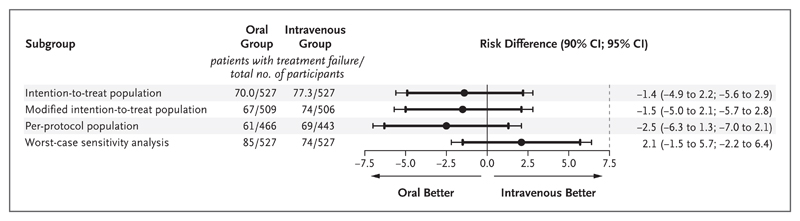

Definitive treatment failure, defined according to clinical, microbiologic, or histologic criteria (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix) and adjudicated by an end-point committee with members who were unaware of the treatment-group assignments, occurred in 74 of 506 participants (14.6%) in the intravenous group and 67 of 509 (13.2%) in the oral group. The missing end-point data for 39 of 1054 participants (3.7%) were imputed (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). The difference in the risk of definitive treatment failure (oral group vs. intravenous group) in the intention-to-treat population was −1.4 percentage points (90% confidence interval [CI], −4.9 to 2.2; 95% CI, −5.6 to 2.9), thus meeting noninferiority criteria based on either the 7.5-percentage-point or 5-percentage-point margin.

The modified intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses were consistent with the intention-to-treat analysis (Fig. 3), as was an exploratory Bayesian analysis that estimated a 0.1% and 12.7% probability that oral treatment was at least 5 percentage points and at least 1 percentage point inferior, respectively, to intravenous treatment. A “worst-case” scenario for missing data (i.e., one in which it was assumed that, for participants with missing data, all those who were randomly assigned to receive oral therapy and none of those who were randomly assigned to receive intravenous therapy had definitive treatment failures) was consistent with noninferiority when the 7.5-percentage-point margin was used.

Figure 3. Differences in Risk According to the Analysis Performed.

The point estimates for the differences in failure rates are shown with 90% (thick lines) and 95% (thin lines) two-sided confidence intervals. The noninferiority margin is indicated by the vertical dashed line. The use of two-sided 90% confidence intervals was prespecified in the trial protocol in accordance with the sample-size calculation. Because two-sided 95% confidence intervals are also now commonly included in noninferiority trials, they are shown here to assess the sensitivity of the results to a change in significance level. In the intention-to-treat population, missing data were imputed with the use of multiple imputation by chained equations. The modified intention-to-treat population included only the participants with complete end-point data. The worst-case sensitivity analysis shows the results based on the worst-case assumption that, for participants with missing data, all participants who were randomly assigned to receive oral therapy and no participants who were randomly assigned to receive intravenous therapy had definitive treatment failures, thus introducing the worst possible bias against the oral strategy.

There was no evidence of heterogeneity according to center (P = 0.51) (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). No predefined or post hoc subgroup analyses showed an outcome advantage of either intravenous or oral therapy (P>0.05 for all analyses of heterogeneity) (Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix), and there was no evidence of a significant between-group difference in the time to treatment failure (P = 0.57) (Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Secondary End Points

In the modified intention-to-treat population, probable or possible treatment failures occurred in 6 of 506 participants (1.2%) in the intravenous group and 10 of 509 participants (2.0%) in the oral group. The difference (oral minus intravenous) in the risk of any treatment failure (definite, probable, or possible) was −0.7 percentage points (90% CI, −4.4 to 3.1; 95% CI, −5.1 to 3.8) (Table S4 in the Supplementary Appendix). Members of the end-point committee were unanimous in their categorization of 136 of 141 cases (96%) as definite treatment failure and 13 of 16 cases (81%) as probable or possible treatment failure. Consensus on the remaining 8 cases was achieved by discussion.

Early discontinuation of the randomly assigned treatment strategy was more common in the intravenous group than in the oral group (99 of 523 participants [18.9%] vs. 67 of 523 [12.8%], P = 0.006), as were complications associated with the intravenous catheter (49 of 523 [9.4%] vs. 5 of 523 [1.0%], P<0.001). There was no significant difference in the incidence of C. difficile–associated diarrhea (9 of 523 [1.7%] in the intravenous group and 5 of 523 [1.0%] in the oral group, P = 0.30) or the percentage of participants reporting at least one serious adverse event (146 of 527 [27.7%] in the intravenous group and 138 of 527 (26.2%) in the oral group, P = 0.58) (Table 2). The median hospital stay was significantly longer in the intravenous group than in the oral group (14 days [interquartile range, 11 to 21] vs. 11 days [interquartile range, 8 to 20], P<0.001) (Fig. S4 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Table 2. Serious Adverse Events and Secondary End Points.

| Event or End Point | Intravenous Group (N = 527) |

Oral Group (N = 527) |

Total (N = 1054) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants with at least one serious adverse event — no. (%)* | 146 (27.7) | 138 (26.2) | 284 (26.9) |

| Classification of serious adverse events — no. of events/total no. (%)† | |||

| Related to operative site‡ | 46/220 (20.9) | 69/224 (30.8) | 115/444 (25.9) |

| Antibiotic-related§ | 30/220 (13.6) | 15/224 (6.7) | 45/444 (10.1) |

| Frailty-related¶ | 10/220 (4.5) | 5/224 (2.2) | 15/444 (3.4) |

| Neurologic | 4/220 (1.8) | 10/224 (4.5) | 14/444 (3.2) |

| Cardiovascular | 26/220 (11.8) | 29/224 (12.9) | 55/444 (12.4) |

| Respiratory | 14/220 (6.4) | 21/224 (9.4) | 35/444 (7.9) |

| Gastrointestinal | 21/220 (9.5) | 13/224 (5.8) | 34/444 (7.7) |

| Renal | 2/220 (0.9) | 8/224 (3.6) | 10/444 (2.3) |

| Diabetic | 7/220 (3.2) | 10/224 (4.5) | 17/444 (3.8) |

| Genitourinary | 9/220 (4.1) | 4/224 (1.8) | 13/444 (2.9) |

| Neoplastic | 4/220 (1.8) | 6/224 (2.7) | 10/444 (2.3) |

| Musculoskeletal, not related to original site | 17/220 (7.7) | 21/224 (9.4) | 38/444 (8.6) |

| Skin and soft tissue, not related to original site | 10/220 (4.5) | 7/224 (3.1) | 17/444 (3.8) |

| Other events‖ | 3/220 (1.4) | 0/224 | 3/444 (0.7) |

| Deaths from any cause** | 17/220 (7.7) | 6/224 (2.7) | 23/444 (5.2) |

| Serious adverse events occurring during first 6 wk of therapy | 76/220 (34.5) | 77/224 (34.4) | 153/444 (34.5) |

| Secondary end points — no. of participants/total no. (%)†† | |||

| Intravenous catheter complications‡‡ | 49/523 (9.4) | 5/523 (1.0) | 54/1046 (5.2) |

| Episode of C. difficile–associated diarrhea§§ | 9/523 (1.7) | 5/523 (1.0) | 14/1046 (1.3) |

| Early discontinuation of randomly assigned treatment strategy¶¶ | 99/523 (18.9) | 67/523 (12.8) | 166/1046 (15.9) |

Shown are participants reporting at least one serious adverse event unrelated to intravenous catheter complications, C. difficile–associated diarrhea, or early discontinuation of the randomly assigned treatment strategy (P = 0.58).

A total of 444 serious adverse events (unrelated to catheter complications, C. difficile–associated diarrhea, or early discontinuation of the randomly assigned treatment strategy) were reported among 284 participants.

This category includes prolongation of hospital stay or readmission for symptom control, wound management, mobility, skin and soft tissue infection, dislocation, or a recurrent primary end-point event.

The antibiotic-related events listed here met the definition of a serious adverse event and were attributed by the responsible infection specialist to antibiotic therapy (rather than to unrelated coexisting conditions). They included acute kidney injury (5 events), allergic reactions requiring immediate intervention (5), confusion (5), drug-induced fever (6), severe gastrointestinal symptoms (8), severe skin reactions (including suspected Stephens–Johnson syndrome) (7), eosinophilic pneumonitis (2), neutropenia or thrombocytopenia (4), tendonitis (1), hepatitis (1), and cardiac arrhythmia (1).

Frailty-related severe adverse events included slips, trips, or falls in elderly participants or readmission as a result of an inability to live at home (e.g., because of problems with mobility, safety, or cognitive impairment).

Other events in the intravenous group included foreign body in eye, acute Epstein–Barr virus infection, alcohol withdrawal, and opiate overdose.

There were 3 deaths within 30 days after randomization, all in the intravenous group; 1 each was attributed to pneumonia, sepsis secondary to infected leg ulcers, and C. difficile–associated toxic megacolon. Of the remaining 20 deaths, 7 (5 in the intravenous group and 2 in the oral group) were attributed to cardiovascular disease, 5 (4 in the intravenous group and 1 in the oral group) to pneumonia, 4 (3 in the intravenous group and 1 in the oral group) to underlying neoplasia, and 1 (in the intravenous group) to spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. The cause of death in 3 patients (1 in the intravenous group and 2 in the oral group) was not reported.

Intravenous catheter complications, C. difficile–associated diarrhea, and early discontinuation of the randomly assigned treatment strategy were secondary end points and were not classified as serious adverse events for the purposes of this analysis. In 8 cases (4 in each group), no data were submitted. In 3 cases (2 in the intravenous group and 1 in the oral group), data were carried forward after censoring.

Intravenous catheter complications included mechanical failure (24 of 49 participants in the intravenous group, 3 of 5 in the oral group), thrombosis or thrombophlebitis (13 of 49 in the intravenous group, 1 of 5 in the oral group), and catheter-related infection (12 of 49 in the intravenous group, 1 of 5 in the oral group). In the intravenous group, catheter complications resulted in removal of the catheter in 42 of 49 participants in the intravenous group and in 4 of 5 participants in the oral group. Overall P<0.001 for the between-group comparison. Four patients who were randomly assigned to the oral group had a catheter complication after having been switched to intravenous therapy after meeting an end point; 1 patient who was randomly assigned to the oral group had a catheter complication arising from an unrelated clinical episode several months after the initial 6-week follow-up period.

The between-group difference in the risk of C. difficile–associated diarrhea was −0.8 percentage points (95% confidence interval, −2.2 to 0.6; P = 0.30 by Fisher’s exact test).

Reasons for early discontinuation of the randomly assigned treatment strategy included difficulties with intravenous access or administration (41 of 99 participants in the intravenous group and 0 of 67 in the oral group), antibiotic adverse effects (26 of 99 in the intravenous group and 23 of 67 in the oral group), patient preference (19 of 99 in the intravenous group and 5 of 67 in the oral group), intercurrent illness (2 of 99 in the intravenous group and 8 of 67 in the oral group), possible or probable recurrence (1 of 99 in the intravenous group and 15 of 67 in the oral group), good clinical response (1 of 99 in the intravenous group and 0 of 67 in the oral group), and other reasons (9 of 99 in the intravenous group and 15 of 67 in the oral group). The reason was not available for 0 of 99 in the intravenous group and 1 of 67 in the oral group. Overall P = 0.006 for the between-group comparison, by Pearson’s chi-square test.

Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

The median EQ-5D-3L score, Oxford Hip Score, and Oxford Knee Score improved over time in both groups. At days 120 and 365, neither the EQ-5D-3L nor the Oxford Hip Score differed significantly between the groups (P = 0.61 and P = 0.18, respectively), but better Oxford Knee Scores were observed in the oral group than in the intravenous group at both time points (P = 0.01 and P = 0.04, respectively) (Table S5 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Adherence to Treatment

Morisky scores of 6 or higher (indicating medium or high adherence) at day 42, which we interpret as indicating a limited risk of adherence-related treatment failure, were reported by 75 of the 80 participants (93.8%) in the intravenous group who administered their own medication and by 283 of 323 participants (87.6%) in the oral group (Table S6 in the Supplementary Appendix). Data from the participants in the oral group, whose adherence was monitored by means of a Medication Event Monitoring System, showed higher than 95% dose-by-dose adherence in 56 of 62 participants (90.3%); 154 of 4060 planned doses (3.8%) were not taken (Table S7 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Planned Antibiotic Therapy

The intravenous and oral antibiotic regimens that had originally been planned by the participants’ physicians were documented before randomization for 917 and 945 participants, respectively. The most frequently planned intravenous antibiotics were glycopeptides (380 of 917 participants [41.4%]) and cephalosporins (345 of 917 [37.6%]) (Table S8 in the Supplementary Appendix). The most frequently planned oral antibiotics (excluding rifampin) were quinolones (414 of 945 participants [43.8%]) and combination oral therapy (133 of 945 [14.1%]) (Table S9 in the Supplementary Appendix). Outcomes did not vary significantly between the groups according to the intended intravenous or oral antibiotic agent (P = 0.42 and P = 0.80, respectively, for heterogeneity) (Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). The actual antibiotics prescribed (excluding rifampin), defined by use for at least 7 days during the initial 6-week treatment period, were most commonly glycopeptides (214 of 521 participants [41.1%]) and cephalosporins (173 of 521 [33.2%]) in the intravenous group and quinolones (191 of 523 [36.5%]) and combination therapy (87 of 523 [16.6%]) in the oral group (Table S10 in the Supplementary Appendix).

The intended use of adjunctive oral rifampin was analyzed separately; it was included with planned intravenous therapy for 142 of 917 participants (15.5%) and with planned oral therapy in 487 of 945 participants (51.5%). Outcomes did not vary significantly according to intended use of rifampin (P = 0.22 for heterogeneity) (Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). The addition of adjunctive rifampin was permitted at any time after randomization; 120 of 523 participants (22.9%) in the intravenous group and 165 of 526 participants (31.4%) in the oral group received rifampin for at least 6 weeks between randomization and final follow-up (Table S11 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Discussion

In this trial, with regard to treatment failure assessed at 1 year, oral antibiotic therapy was non-inferior to intravenous antibiotic therapy when used during the first 6 weeks of treatment for bone and joint infection; our results thereby challenge a widely accepted standard of care.4,15,16 Subgroup analyses did not identify significant heterogeneity, irrespective of baseline surgical procedure, retention of metalware, pathogen, or intended antibiotics at randomization. Oral therapy was associated with shorter hospital stays and fewer complications than intravenous therapy. Oral therapy may not be appropriate for some patients (e.g., those with poor enteral absorption) and pathogens (e.g., those with resistance to oral agents).

The participants in this trial represented the broader patient population, as indicated by the choice of antibiotics9 and the pathogens identified. 17,18 Most participants followed their randomly assigned treatment strategy, and trial retention was high, indicating that the trial design and interventions were generally acceptable. Adherence to oral medication was good; the investigators provided advice regarding adherence but did not use trial-specific adherence tools such as text reminders.

Our trial had some limitations. It was necessarily open label; it would have been impractical to produce matched placebo for each antibiotic that might have been prescribed and would have been unethical to expose participants in the oral group to the risks associated with intravenous administration of placebo for 6 weeks. Objective end-point criteria and an end-point committee with members who were unaware of the treatment-group assignments minimized potential bias due to the open-label design.

We were concerned that participants in the oral group might be prescribed longer follow-on courses of antibiotics than the participants in the intravenous group. In fact, the total treatment duration did not differ between the groups (Fig. 2B). Participants in the intravenous group probably had more frequent health care assessments than did those in the oral group, but treatment failure was not identified earlier in the intravenous group (Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Appendix), which suggests that there was no clinically important variation in postrandomization surveillance.

In this trial, we did not seek to compare specific antibiotic agents or to stipulate which agents should be used. We relied on the expertise of the consulting infectious-disease specialist to select and adjust antibiotic regimens, taking into account factors such as susceptibilities, risk of the emergence of resistance, bioavailability, tissue penetration, side effects, coexisting conditions, and drug interactions. This strategy carries a risk that, in some cases, the preferred antibiotic as defined by in vitro testing may not have been prescribed, but this risk would have been mitigated by the oversight of an accredited specialist in infectious diseases selecting the appropriate therapy for individual participants, consistent with real-world practice.

Rifampin, which is considered by many to be an important agent in the treatment of certain biofilm-associated infections, was more commonly planned as treatment in early antibiotic regimens in the oral group than in the intravenous group, although a subgroup analysis showed no significant effect of planned use on outcome. Actual rifampin use at any time during treatment varied less between the groups than planned use, which suggests that the timing of adjunctive rifampin treatment was influenced by the randomly assigned treatment strategy.

This trial was deliberately inclusive: there was no selection according to infecting organism, surgical procedure, or anatomic site. Although the resulting trial population was heterogeneous, the advantages of generalizability outweigh the disadvantages of heterogeneity. A more selective recruitment strategy, such as inclusion of only primary arthroplasty infections with Staphylococcus aureus, would have made the trial prohibitively long and would have limited the utility of the results. The trial hypothesis was based on the pharmacokinetic principle that appropriately selected oral agents provide adequate antibiotic concentrations at the site of infection. This principle is unlikely to have been differentially affected by, for example, the anatomic site, presence of metalwork, or extent of surgical débridement. However, selection of the appropriate oral agents necessarily relied on a clear understanding of the relevant pharmacologic variables and close liaison between surgical and infectious-disease specialists.

Causal attribution of serious adverse events related to antibiotics was determined by the responsible infectious-disease specialist. Given that these were necessarily based on subjective assessments, they may have been liable to potential biases of unknown effect. Because the participants in the trial were followed up for only 1 year, we cannot rule out the possibility that the risk of later treatment failure, which is known to occur with osteomyelitis, may differ between the trial groups.

We found that appropriately selected oral antibiotic therapy was noninferior to intravenous therapy when used during the first 6 weeks in the management of bone and joint infection, as assessed by treatment failure within 1 year. Oral antibiotic therapy was associated with a shorter length of hospital stay and with fewer complications than intravenous therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service (NHS), the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), or the U.K. Department of Health.

Supported by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment program (project number 11/36/29), the NIHR Imperial College Biomedical Research Centre (to Dr. Cooke), and the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (to Drs. Walker, M. Scarborough, and Bejon).

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

We thank the participants for their participation; the staff of the Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences for coordinating the trial through the Surgical Interventions Trials Unit; the staff of the Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Neil French, Martin Llewelyn, and Colette Smith for their contributions as members of the data and safety monitoring committee; Ben Lipsky, Harriet Hughes, and Deepa Bose for their role as members of the end-point review committee; David Beard and Patrick Julier for their support through the clinical trials unit; Jennifer A. de Beyer for English language editing of the final submitted manuscript; all members of the infectious diseases and orthopedic departments at Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust for their support; the members of the U.K. Clinical Infection Research Group; and the research nurses and investigators across the 26 contributing sites.

Appendix

The authors’ full names and academic degrees are as follows: Ho-Kwong Li, M.R.C.P., Ines Rombach, D.Phil., Rhea Zambellas, M.Sc., A. Sarah Walker, Ph.D., Martin A. McNally, F.R.C.S.(Orth.), Bridget L. Atkins, F.R.C.P., Benjamin A. Lipsky, M.D., Harriet C. Hughes, M.A.(Cantab.), Deepa Bose, F.R.C.S., Michelle Kümin, Ph.D., Claire Scarborough, M.R.C.P., Philippa C. Matthews, D.Phil., Andrew J. Brent, Ph.D., Jose Lomas, M.D., Roger Gundle, D.Phil., Mark Rogers, F.R.C.S., Adrian Taylor, F.R.C.S., Brian Angus, F.R.C.P., Ivor Byren, F.R.C.P., Anthony R. Berendt, F.R.C.P., Simon Warren, F.R.C.P., Fiona E. Fitzgerald, R.N., Damien J.F. Mack, F.R.C.Path., Susan Hopkins, F.R.C.P., Jonathan Folb, Ph.D., Helen E. Reynolds, R.N., Elinor Moore, F.R.C.P., Jocelyn Marshall, R.N., Neil Jenkins, Ph.D., Christopher E. Moran, Ph.D., Andrew F. Woodhouse, F.R.C.A.P., Samantha Stafford, R.N., R. Andrew Seaton, M.D., Claire Vallance, B.N., Carolyn J. Hemsley, Ph.D., Karen Bisnauthsing, M.Sc., Jonathan A.T. Sandoe, Ph.D., Ila Aggarwal, F.R.C.Path., Simon C. Ellis, M.R.C.P., Deborah J. Bunn, R.N., Rebecca K. Sutherland, F.R.C.P., Gavin Barlow, F.R.C.P., Cushla Cooper, M.Sc., Claudia Geue, Ph.D., Nicola McMeekin, M.Sc., Andrew H. Briggs, D.Phil., Parham Sendi, M.D., Elham Khatamzas, Ph.D., Tri Wangrangsimakul, F.R.C.Path., T.H. Nicholas Wong, F.R.C.Path., Lucinda K. Barrett, Ph.D., Abtin Alvand, D.Phil., C. Fraser Old, Ph.D., Jennifer Bostock, M.A., John Paul, M.D., Graham Cooke, F.R.C.P., Guy E. Thwaites, F.R.C.P., Philip Bejon, Ph.D., and Matthew Scarborough, Ph.D.

The authors’ affiliations are as follows:

Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (H.-K.L., M.A.M., B.L.A., P.C.M., A.J.B., J.L., R.G., M.R., A.T., B.A., I.B., A.R.B., E.K., T.W., T.H.N.W., L.K.B., A.A., P.B., M.S.) and the Nuffield Departments of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Science (I.R., R.Z., C.C., A.A.) and Medicine (M.K., C.S., P.C.M., A.J.B., B.A., G.E.T., P.B., M.S.) and the Division of Medical Sciences (B.A.L.), University of Oxford, Oxford, the Division of Infectious Diseases, Imperial College London (H.-K.L., G.C.), Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Unit, University College London (A.S.W.), Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust (S.W., D.J.F.M., S.H.), Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust (C.J.H., K.B.), and Public Health England (J.P.), London, University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff (H.C.H.), University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust (D.B.) and Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust (N.J., C.E.M., A.F.W., S.S.), Birmingham, Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital NHS Trust, Stanmore (S.W., F.E.F., D.J.F.M.), Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospitals NHS Trust, Liverpool (J.F., H.E.R.), Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridge (E.M., J.M.), Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde (R.A.S., C.V.), and Health Economics and Health Technology Assessment, University of Glasgow (C.G., N.M., A.H.B.), Glasgow, Leeds Teaching Hospital NHS Trust, University of Leeds, Leeds (J.A.T.S.), Ninewells Hospital, NHS Tayside, Dundee (I.A.), Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, Northumberland (S.C.E., D.J.B.), Western General Hospital, NHS Lothian, Edinburgh (R.K.S.), and Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust, Hull (G.B.) — all in the United Kingdom; University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland (P.S.); Oxford University Clinical Research Unit, Wellcome Trust, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam (G.E.T.); and Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI)–Wellcome Trust Research Programme, Kilifi, Kenya (P.B.). C.F.O. and J.B. are patient representatives and do not have an institutional affiliation.

Footnotes

A complete list of the OVIVA trial collaborators is provided in the Supplementary Appendix, available atlabel NEJM.org.

Address reprint requests to Dr. M. Scarborough at Microbiology Level 6, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford OX3 9DL, United Kingdom.

References

- 1.Lew DP, Waldvogel FA. Osteomyelitis. Lancet. 2004;364:369–79. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16727-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimmerli W, Ochsner PE. Management of infection associated with prosthetic joints. Infection. 2003;31:99–108. doi: 10.1007/s15010-002-3079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li HK, Agweyu A, English M, Bejon P. An unsupported preference for intravenous antibiotics. PLoS Med. 2015;12(5):e1001825. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waldvogel FA, Medoff G, Swartz MN. Osteomyelitis: a review of clinical features, therapeutic considerations and unusual aspects. N Engl J Med. 1970;282:198–206. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197001222820406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spellberg B, Lipsky BA. Systemic antibiotic therapy for chronic osteomyelitis in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:393–407. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rangel SJ, Anderson BR, Srivastava R, et al. Intravenous versus oral antibiotics for the prevention of treatment failure in children with complicated appendicitis: has the abandonment of peripherally inserted catheters been justified? Ann Surg. 2017;266:361–8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conterno LO, Turchi MD. Antibiotics for treating chronic osteomyelitis in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004439.pub3. CD004439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li HK, Scarborough M, Zambellas R, et al. Oral versus intravenous antibiotic treatment for bone and joint infections (OVIVA): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:583. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-1098-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Berendt AR, et al. Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(1):e1–e25. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37:53–72. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray DW, Fitzpatrick R, Rogers K, et al. The use of the Oxford hip and knee scores. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1010–4. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B8.19424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10:348–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 13.Farmer KC. Methods for measuring and monitoring medication regimen adherence in clinical trials and clinical practice. Clin Ther. 1999;21:1074–1090. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(99)80026-5. 1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30:377–99. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mader JT, Calhoun J. Osteomyelitis. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Mandell, Douglas and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases. 4th ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1995. pp. 1039–51. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berendt AR, McNally M. Osteomyelitis. In: Warell DA, Cox TM, Firth JD, editors. Oxford textbook of medicine. 5th ed. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 3788–95. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheehy SH, Atkins BA, Bejon P, et al. The microbiology of chronic osteomyelitis: prevalence of resistance to common empirical anti-microbial regimens. J Infect. 2010;60:338–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Titécat M, Senneville E, Wallet F, et al. Bacterial epidemiology of osteoarticular infections in a referent center: 10-year study. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013;99:653–8. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.