Abstract

Objective

We evaluated the clinical effects of a telephone call service for psychological symptoms such as anxiety, depression or apathy in subacute myelo-optico-neuropathy (SMON) patients living alone or with a single caregiver.

Methods

Up to 16 SMON patients (4 men, 12 women) and 32 control subjects were evaluated by the geriatric depression scale (GDS), apathy scale (AS) and state and trait anxiety inventory (STAI) forms X-I, including the P and A values for depression, apathy and state anxiety including disturbed peace of mind and enhanced anxiety, respectively, before (pre) and three months after (post) the telephone call service.

Results

The SMON patients, especially women, had significantly worse baseline scores in GDS (depression), AS (apathy) and STAI (state anxiety) than control subjects. The automated telephone call service significantly improved the high baseline STAI scores, including the P and A scores (disturbed peace of mind and enhanced anxiety), of SMON patients but not the GDS or AS scores.

Conclusion

SMON patients, especially women, living alone or with a single caregiver showed higher baseline depression, apathy and anxiety scores than the control subjects. The present automated telephone call service proved to be a useful care tool for improving the anxiety of SMON patients with high STAI P and A scores.

Keywords: anxiety, SMON, STAI, telephone call service

Introduction

Subacute myelo-optico-neuropathy (SMON) is a subacute neurological disease characterized by sensory and motor disturbances in the lower extremities and visual impairment due to clioquinol intoxication. While the cognitive function is rarely impaired (1-3), SMON patients sometimes experience affective problems, such as depression and apathy, related to the severity of neurological symptoms and limited activities of daily living (ADL) (4-6). We previously reported changes in anxiety due to genetic testing in hereditary spinocerebellar degeneration (SCD) patients (7). However, anxiety in SMON patients has not been well evaluated, especially among those who are living alone or with a single caregiver at home in a super-aged society.

We previously reported the efficacy of a unique telephone call service (Andes PhoneⓇ, Andes, Matsudo, Japan) for improving the anxiety among neurological disease patients living alone or with a single caregiver (8). This system automatically calls participants at their desired time once a week, and participants answer questions simply by pressing the numbers #1, #2 or #3 on their phone. In the present study, we evaluated the clinical effects of this telephone call service in relieving psychological symptoms, such as anxiety, depression and apathy, in SMON patients living alone or with a single caregiver.

Materials and Methods

Participants and subjects

The present study included SMON patients without cognitive impairment (n=16; 12 men, 4 women) living alone (n=2; 1 man and 1 woman) or with a single caregiver (n=14), and control subjects (n=32) living alone (n=3) or with a single caregiver (n=29) from an outpatient clinic at Okayama University Hospital. All SMON patients showed mild muscle weakness and sensory disturbance in the lower limbs but were independent in their daily life and always able to visit a primary-care doctor near their home. Subjects without any neurodegenerative disease, psychiatric disease or cognitive impairment were included as control subjects who were matched for age and gender with SMON patients. A lack of cognitive impairment among the subjects was confirmed by expert neurological clinicians according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition or the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision. All participants gave their written informed consent, and the Okayama University Ethics Review Board approved all study procedures.

Automated telephone call service and clinical evaluation

SMON patients received calls from an automated telephone call service (Andes PhoneⓇ) with the aim of checking on their medical conditions at their desired time of day, once a week for three months. The participants answered questions from the telephone service by pressing the appropriate number: #1 for ‘no problem,’ #2 for ‘request a phone call within a few days by a medical consultant,’ and #3 for ‘request an immediate phone call by a medical consultant.’ When the participants pressed #2 or #3 for the telephone service, a member of the Okayama Prefecture Intractable Disease Medical Council staff called them back within a few days (for #2) or as soon as possible (for #3) to address the patients' problems and carefully advise them with appropriate medical consultations. The percentage of each answer type (#1, #2, and #3), and any calls/answers made in error, by the participants was recorded.

Just before (pre) and three months after (post) starting the telephone call service, SMON patients were evaluated at the outpatient clinic of Okayama University Hospital using affective assessments, namely the geriatric depression scale (GDS) (9), apathy scale (AS) (10) and state and trait anxiety inventories (STAI) (11) forms X-I for depression, apathy and state anxiety, respectively. The STAI (forms X-I) were separated into two types of questions: one evaluating the degree of disturbed peace of mind (P value) and another evaluating the degree of enhanced anxiety (A value). Control subjects were also evaluated by GDS, AS and STAI only once at the clinic of Okayama University Hospital. Clinical demographic data, such as the participants' age and sex, were also analyzed.

Statistical analyses

Comparisons between baseline characteristics (gender and age) and the scores of affective assessments before (pre) the start of the telephone call service for control subjects and SMON patients, further divided by sex, were carried out using the Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test followed by a Dunn's post hoc comparison for continuous variables, and with Pearson's chi-squared test (χ2) for comparison of proportions. Changes in affective assessment scores between pre- and post-telephone service were analyzed using Wilcoxon's signed-rank test. Spearman's rank correlation-coefficient test was conducted to examine correlations among STAI scores before the telephone service and the change after implementation (post-telephone service minus pre-telephone service), and among the change in the STAI score after implementation and the percentage of ‘request call back’ answers for the telephone service.

Statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism 5 software program (version 5.00; GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA). A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

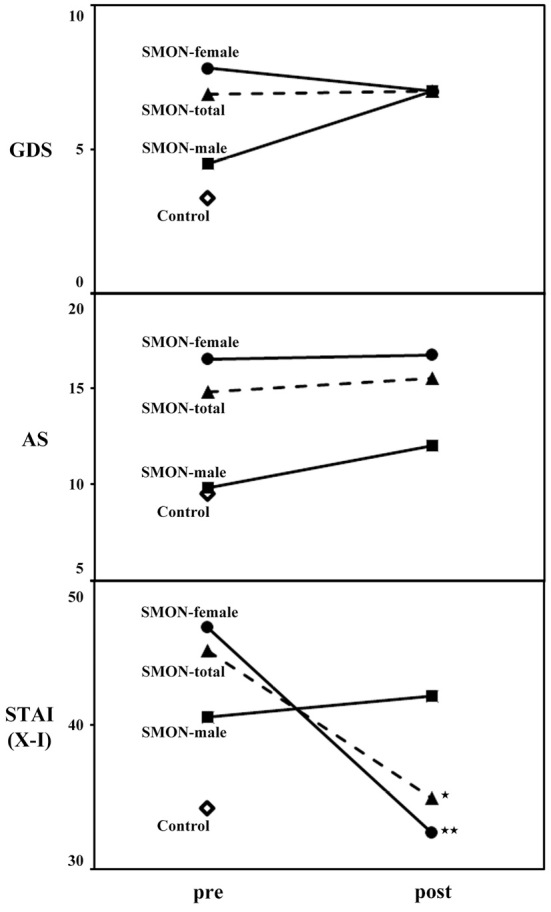

The clinical characteristics of control subjects and SMON patients are shown in Table. There was no significant difference in the gender or age between the control subjects and total, male and female SMON patients. There were no significant gender-related differences in the GDS and AS scores of the control subjects (data not shown). The baseline GDS and AS scores of the total SMON patients (6.9±4.3 and 14.8±8.3, respectively), especially female SMON patients (7.8±4.2 and 16.5±7.8, respectively), were significantly worse than those of control subjects (3.3±2.6 and 9.5±5.9, respectively) (Table, #p<0.05). After the telephone call service, the GDS and AS scores of total and female SMON patients did not change (Table, Fig. 1, upper and middle panel), while those of male patients worsened (not significant).

Table.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients with SMON.

| Control | SMON | Statistical analysis | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | |||||||||||

| No. of cases | 32 | 16 | 4 | 12 | |||||||||

| Male (%) | 43.8 | 25.0 | a) χ2=1.60; p=n.s. | ||||||||||

| Age at examination (y) | 74.9 | ± | 6.1 | 77.8 | ± | 8.6 | 80.3 | ± | 8.8 | 76.9 | ± | 8.4 | b) p=n.s. |

| Pre-telephone service | |||||||||||||

| GDS | 3.3 | ± | 2.6 | 6.9 | ± | 4.3# | 4.5 | ± | 3.6 | 7.8 | ± | 4.2# | b) p<0.01 |

| AS | 9.5 | ± | 5.9 | 14.8 | ± | 8.3 | 9.8 | ± | 7.6 | 16.5 | ± | 7.8 | b) p<0.05 |

| STAI (X-I) total | 34.2 | ± | 9.3 | 45.1 | ± | 11.3## | 40.5 | ± | 6.5 | 46.7 | ± | 12.1## | b) p<0.001 |

| STAI (X-I) P value | 20.3 | ± | 6.3 | 26.5 | ± | 7.3# | 20.8 | ± | 3.9 | 28.4 | ± | 7.6## | b) p<0.01 |

| STAI (X-I) A value | 14.1 | ± | 5.9 | 18.6 | ± | 5.7# | 19.8 | ± | 5.7 | 18.3 | ± | 6.2 | b) p<0.01 |

| Post-telephone service | |||||||||||||

| GDS | 7.0 | ± | 3.0 | 7.0 | ± | 1.9 | 7.0 | ± | 3.3 | b) p=n.s. | |||

| AS | 15.5 | ± | 9.4 | 12.0 | ± | 6.7 | 16.7 | ± | 9.8 | b) p=n.s. | |||

| STAI (X-I) total | 34.9 | ± | 9.6 | 42.0 | ± | 8.1 | 32.5 | ± | 8.9 | b) p=n.s. | |||

| STAI (X-I) P value | 22.6 | ± | 7.7 | 27.0 | ± | 5.8 | 21.2 | ± | 8.2 | b) p=n.s. | |||

| STAI (X-I) A value | 12.3 | ± | 3.2 | 15.0 | ± | 4.8 | 11.3 | ± | 2.1 | b) p=n.s. | |||

| Answer for telephone service | |||||||||||||

| No problem (%) | 64.5 | 53.0 | 68.3 | b) p=n.s. | |||||||||

| Request call back (%) | 7.4 | 8.8 | 7.0 | b) p=n.s. | |||||||||

| Error (%) | 28.1 | 38.3 | 24.7 | b) p=n.s. | |||||||||

Data are expressed mean±SD.

Dunn’s multiple comparisons: #p<0.05 vs. control; ##p<0.01 vs. control.

a)chi square test; b)Kruskal–Wallis test.

AS: apathy score, GDS: geriatric depression scale, n.s.: not significant, SD: standard deviation, SMON: subacute myelo-optico neuropathy, STAI: state-trait anxiety inventory

Figure 1.

Affective assessments (GDS, AS, and STAI X-I) of control subjects and total, male and female SMON patients before (pre) and after (post) the implementation of the telephone call service. In contrast to GDS and AS, the STAI scores of the total and female SMON patients greatly improved after the implementation of the telephone call service. *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

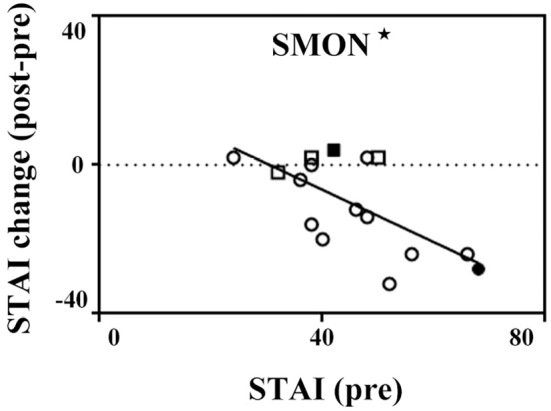

The baseline total STAI (forms X-I) scores of female control subjects (37.9±9.1) were significantly worse than that of male control subjects (29.4±7.3, p<0.05). The baseline total STAI (forms X-I) scores of total SMON patients (45.1±11.3), especially female SMON patients (46.7±12.1), were significantly worse than those of control subjects (34.2±9.3) (Table, ##p<0.01). After the implementation of the telephone call service, the total STAI scores significantly improved in total and female SMON patients (34.9±9.6 and 32.5±8.9, *p<0.05 and **p<0.01, respectively) but not in male patients (42.0±8.1, Table, Fig. 1, lower panel). A comparison between the baseline (pre) STAI scores and the change in the score after implementation (post-pre scores) showed a significant correlation among SMON patients (Fig. 2, *p<0.05), especially in women (Fig. 2, black and blank circles).

Figure 2.

Scatter plots describing the relationships between the baseline (pre) STAI and STAI score change (post-pre) in SMON patients. Black and blank squares show male SMON patients living alone (n=1) and with a single caregiver (n=3), respectively. Black and blank circles show female SMON patients living alone (n=1) and with a single caregiver (n=11). The baseline STAI scores were significantly correlated with the post-pre STAI scores. *p<0.05.

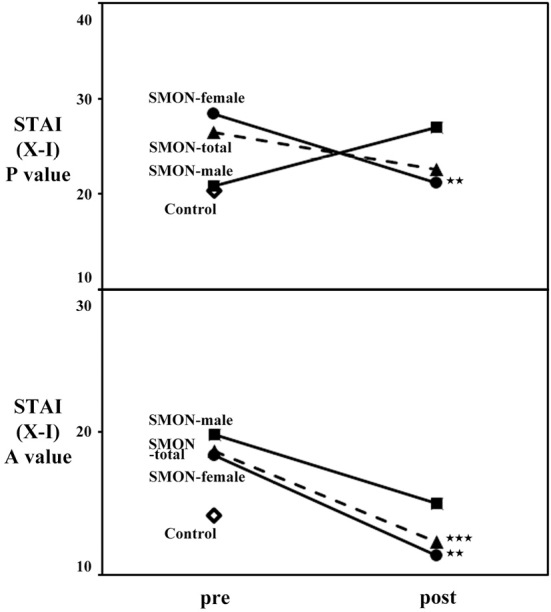

To further analyze the clinical effects of the telephone call service for STAI (forms X-I) scores in SMON patients, control subjects and SMON patients were analyzed in subscales of STAI scores, STAI (X-I) P value and STAI (X-I) A value scores. The baseline STAI (forms X-I) P and A scores of female control subjects (22.0±5.8 and 16.1±6.9) were worse than those of male control subjects (18.0±6.0, not significant, and 11.4±2.4, p<0.01). The baseline STAI (X-I) P scores of total and female SMON patients (26.5±7.3 and 28.4±7.6, respectively) were significantly worse than those of control subjects (20.3±6.3) (Table, #p<0.05 and ##p<0.01) but not worse than those of male SMON patients (20.8±3.9), while baseline STAI (X-I) A scores of total, male and female SMON patients (18.6±5.7, 19.8±5.7 and 18.3±6.2, respectively) were significantly worse than those of control subjects (14.1±5.9) (Table, #p<0.05). After the implementation of the telephone call service, the STAI (X-I) P scores were significantly improved in female SMON patients (21.2±8.2, **p<0.01) but worsened in male SMON patients (27.0±5.8, Table, Fig. 3), while the STAI (X-I) A scores significantly improved in total, male and female SMON patients (12.3±3.2, 15.0±4.8 and 11.3±2.1, respectively, Table, Fig. 3, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001).

Figure 3.

The STAI P value and A values of control subjects and total, male and female SMON patients before (pre) and after (post) the implementation of the telephone call service. The STAI P scores of female SMON patients and the STAI A scores of total and female SMON patients greatly improved after the implementation of the telephone call service, whereas the STAI P scores of male SMON patients worsened. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Total SMON patients showed 28.1% error answers for the telephone call service (Table), which was similar to other neurological diseases and caregiver (8). The rate of answer in total, male or female SMON patients requesting a call back was not correlated with the improvement of STAI scores after the telephone call service (data not shown).

Discussion

The present study showed that SMON patients, especially female SMON patients, living alone or with a single caregiver had significantly worse baseline scores in GDS (depression), AS (apathy) and total STAI (state anxiety) than control subjects (Table). The automated telephone call service for three months significantly improved the STAI scores of female SMON patients but not the GDS or AS scores (Table, Fig. 1). The baseline (pre) STAI score of SMON patients significantly correlated with the score change (post - pre), especially in women (Fig. 2), suggesting a greater benefit of the telephone call service for female SMON patients with severe baseline anxiety. However, the telephone call service greatly improved the STAI A value scores in both male and female SMON patients as well as the STAI P scores in female SMON patients (Table, Fig. 3).

We previously reported that frontal behavioral impairment was correlated with affective disturbances in ALS patients (12). While SMON patients reportedly seem to have worse affective and psychological functions in depression and apathy than the control subjects because SMON patients suffer from phytotoxicity (the harmful effects of clioquinol) (1, 5, 6, 13), the prevalences of dementia have been found to be low in SMON patients (1-3). However, anxiety in SMON patients has not been investigated. The present study is the first to show that SMON patients have a worse state anxiety score accompanied by depression and apathy than the control subjects (Table, Fig. 1), findings that were similar to those in amyotroic lateral sclerosis (ALS), SCD, multiple system atrophy (MSA) and Parkinson's disease (PD) patients (8). Previous reports have shown that the degree of depressive state was associated with the severity of neurological symptoms and limited ADL, especially in female SMON patients (4-6). The present SMON patients living alone or with a single caregiver showed significantly worse depression, apathy and state anxiety scores than control subjects (Table), although the SMON patients were independent in their daily life and always able to visit their primary-care doctor. The present study also showed that female control subjects and SMON patients have a significant worse state anxiety score than male control subjects and SMON patients (Table, Fig. 1), suggesting that women are at a higher risk of psychological diseases, including anxiety, than men (14).

We previously showed the efficacy of the present telephone call service (Andes PhoneⓇ) for improving anxiety in neurological disease patients suffering from ALS, SCD, MSA, PD, multiple sclerosis (MS) and Alzheimer's disease (AD), especially ALS, SCD, MSA and PD patients with high STAI scores, but we did not analyze the gender-associated differences (8). This telephone service was also shown to be useful for relieving anxiety, including a disturbed peace of mind (STAI P value) and enhanced anxiety (STAI A value), among female SMON patients, particularly those with high STAI scores (Table, Fig. 1-3). In male SMON patients, the present telephone call service improved their enhanced anxiety (STAI A value), which had been higher than control subjects before the implementation of the service, but not the disturbed peace of mind (STAI P value), which was not very high before the service (Table, Fig. 3). These findings suggest that the automated telephone service was useful for improving the elevated STAI P and A scores in SMON patients. Because a high rate of requesting a call back was not correlated with improvement in the STAI scores (date not shown) in male or female patients, we suspect that the anxiety of SMON patients was improved simply by receiving the automated call service every week at home.

In conclusion, female SMON patients living alone or with a single caregiver showed higher baseline depression, apathy and anxiety scores than control subjects (Table). The present automated telephone call service proved to be a useful care tool for improving the high baseline anxiety if SMON patients, especially women (Table, Fig. 1-3), similar to observations in ALS, SCD, MSA and PD patients.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

Financial Support

This work was supported in part by the Okayama Prefecture Intractable Disease Medical Council, a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research and Grants-in-Aid from Research Committees from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED).

Acknowledgement

We thank Satoko Kawano, Fumie Saito, Miho Suzuki and Satoko Yabuta for their technical assistance.

References

- 1.Kawahara Y, Deguchi K, Hishikawa N, et al. Cognitive and affective functions of aged subacute myelo-optico neuropathy patients in Japan. Neurol Clin Neurosci 3: 173-178, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konagaya M, Matsumoto A, Takase S, et al. Clinical analysis of longstanding subacute myelo-optico-neuropathy: sequelae of clioquinol at 32 years after its ban. J Neurol Sci 218: 85-90, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saito Y, Sakai K, Konagaya M. The prevalence of dementia in subacute myelo-optico-neuropathy (SMON) patients who underwent medical checkups. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi (Jpn J Geriatrics) 53: 152-157, 2016(in Japanese, Abstract in English). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamei T, Hashimoto S, Kawado M, et al. Activities of daily living, functional capacity, and life satisfaction of subacute myelo-optico-neuropathy patients in Japan. J Epidemiol 19: 28-33, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Konishi T, Hayashi K, Hayashi M, et al. Depression in patients with subacute myelo-optico-neuropathy (SMON). Intern Med 47: 2127-2131, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konishi T, Hayashi K, Sugiyama H. The aggravation of depression with aging in Japanese patients with subacute myelo-optico-neuropathy (SMON). Intern Med 56: 2119-2123, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abe K, Itoyama Y. Psychological consequences of genetic testing for spinocerebellar ataxia in the Japanese. Eur J Neurol 4: 593-600, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohta Y, Yamashita T, Hishikawa N, et al. Affective improvement of neurological disease patients and caregivers using an automated telephone call service. J Clin Neurosci 56: 74-78, 2018(Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lesher EL, Berryhill JS. Validation of the geriatric depression scale--short form among inpatients. J Clin Psychol 50: 256-260, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Starkstein SE, Fedoroff JP, Price TR, Leiguarda R, Robinson RG. Apathy following cerebrovascular lesions. Stroke 24: 1625-1630, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaudry E, Vagg P, Spielberger CD. Validation of the state-trait distinction in anxiety research. Multivariate Behav Res 10: 331-341, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohta Y, Sato K, Takemoto M, et al. Behavioral and affective features of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. J Neurol Sci 381: 119-125, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoshigoe K, Hayabara T, Usuki T, et al. The psychological properties of SMON patients: studied by means of two questionnaires: the profile of mood states and the stress coping scale (in Japanese). Jpn J Psychosom Med 38: 433-441, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Remes O, Brayne C, van der Linde R, Lafortune L. A systematic review of reviews on the prevalence of anxiety disorders in adult populations. Brain Behav 6: e00497, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]