Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to compare the isokinetic strength of hip muscles in dominant vs nondominant legs in healthy adults.

Methods

Thirty-two healthy college students (15 male and 17 female) volunteered to participate in this study. A Biodex system 3 was used to measure isokinetic peak torque at an angular velocity of 60°/s for the hip flexors, extensors, abductors, and adductors in both dominant and nondominant legs. Hip flexors and extensors were tested from the supine lying position while hip abductors and adductors were tested from the side lying position using concentric mode of muscle contraction.

Results

There were no statistically significant differences between the dominant and nondominant sides for all tested hip muscles.

Conclusion

Leg dominance does not appear to affect hip muscle strength in healthy adults. This may be used as normative data for those with differences in muscle strength between involved and uninvolved sides.

Key Indexing Terms: Musculoskeletal Physiological Phenomena, Hip Joint, Muscle Strength

Introduction

Although the human body appears to be bilaterally symmetrical, the right and left sides are not the same and may be recognized as anatomically asymmetric. The cerebral hemisphere that controls movements of the limbs shows anatomical differences between the right and left sides. It was suggested that the modal difference between the sides means that sense organs, central nerves, and effectors have asymmetric ability to move efficiently and appropriately. The asymmetry of function has been defined as lateral dominance.1

The leg dominance of either the right or the left differs among people.2 Some studies examining the lateral dominance of the legs used performance tests such as standing long jump and vertical jumping.3 Lateral dominance for muscular endurance of the leg used in isokinetic exercise is not clear. When exerting maximum muscular strength, humans control the needed muscular strength based on their own sensation of output and exert suitable muscular strength.4

During rehabilitation, limb strength symmetry is used as an evaluation criterion to determine the level of participation in sporting events and activities of daily living. Range of motion (ROM), muscular strength, muscular endurance, and power are also often measured to assess limb symmetry. Non–weight-bearing isokinetic testing is a widely used method to measure maximum unilateral strength for strength comparisons between legs. However, non–weight-bearing strength testing may not provide sufficient information to predict performance during weight-bearing tasks.5 Greater than a 15% difference between limbs is often considered a substantial asymmetry in healthy athletes and may put them at increased risk of injury.6 By increasing weight-bearing asymmetry, the postural instability increases owing to reduced efficiency of hip load and unload mechanisms, increasing compensatory ankle movements.7

Peak torque as an indicator of muscle strength is frequently used in the rehabilitation process as a goal for return to participation by making a comparison between the injured and noninjured limbs.8 The isokinetic strength test is used as a functional test to examine unilateral strength imbalances.9 Previous studies comparing muscle strength between dominant and nondominant legs concentrated on functional performance tests and isokinetic knee and ankle strength assessment in athletes and healthy individuals. For example, Siqueira et al10 evaluated isokinetic strength of knee flexors and extensors in nonathletes, jumper athletes, and nonjumper athletes. In addition, the effect of leg dominance on ROM, limb alignment, calf muscle circumference, isometric ankle joint torque, and myoelectric activity of calf muscles was investigated in middle-aged people by Valderrabano et al.11

In the same context, a study conducted by Lanshammar and Ribom12 was to assess hamstring and quadriceps muscle strength in dominant vs nondominant legs of middle-aged women. Isolated assessment of the effect of leg dominance on hip muscle strength by a valid instrument like isokinetic dynamometer is needed. Moreover, Rezaei et al13 assessed knee flexor and extensor strength in healthy Iranian men and women using an isokinetic dynamometer. Furthermore, McGrath et al14 conducted a systematic review to assess the effect of leg dominance on isokinetic quadriceps and hamstring muscle strengths, hamstring-to-quadriceps ratios, single-leg hop for distance, single-leg vertical jump, and vertical ground reaction force after a single-leg vertical jump.

Based upon the above information, studies assessing isokinetic hip muscle strength in dominant vs nondominant limbs are needed. The hip joint is an important joint that bears and transfers weight from the upper body to the lower limbs. Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to isolate hip joint muscles for isokinetic strength assessment in dominant vs nondominant legs. The current study also focused on isolated assessment of healthy nonathletes to eliminate the effect of sport participation on muscle strength and also to make a base of results and normative data for the hip joint.

Materials and Methods

Participants

This study involved 32 healthy college students (15 male and 17 female) from the Faculty of Physical Therapy, Cairo University, Egypt. They volunteered to participate in this study. The age, body mass, and height ranges were 20.47 ± 0.36 years, 67.78 ± 2.06 kg, and 166.4 ± 1.58 cm, respectively. The dominant side for all participants was the right side. Leg dominance was identified by participants as the leg that would be used to kick a ball or to ascend and descend stairs.15

Participants were included in the study if they were free from musculoskeletal injuries and deformities. In addition, hip muscle strength was of at least grade 4 as assessed by manual muscle test. All participants gave written consent upon agreement to participate in the study. The Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Physical Therapy, Cairo University approved this study.

Instrumentation

The Biodex system 3 isokinetic dynamometer (Biodex Medical Systems, Shirley, New York) was used to measure peak torque (PT) values of hip flexors, extensors, abductors, and adductors for both dominant and nondominant legs as an indicator of muscle strength. The Biodex dynamometer is an electromechanical device, which provides measures of peak torque of varied joints through different angular velocities.16 The Biodex 3 is a reliable device by which the same results are obtained when the test is repeated several times.17., 18.

Procedures

The participants’ personal data were collected. The data included each participant’s age, body mass, height, and dominant side. The nature of the study, aims, equipment, and procedures were explained to the participants before starting measurement to be familiar with the study. The isokinetic strengths of the hip muscles were evaluated during concentric contraction at an angular velocity of 60°/s. This velocity is the most representative of muscle strength according to force velocity relationship data.19., 20.

Isokinetic Evaluation of Hip Muscle Strength

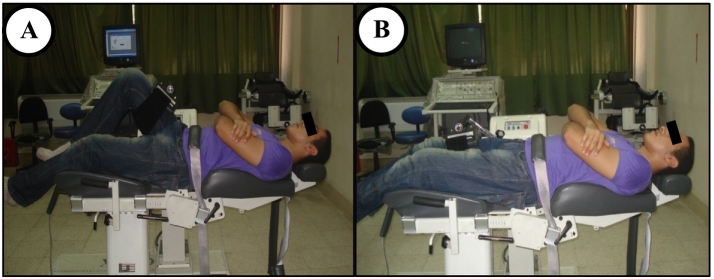

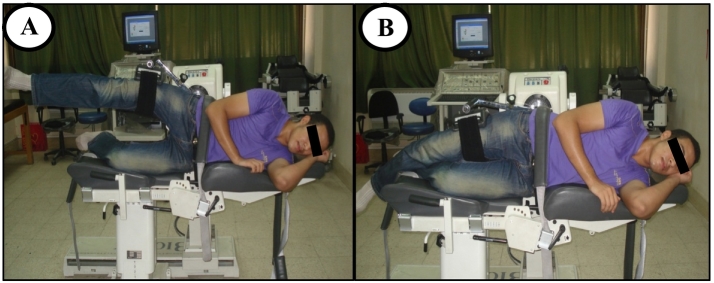

For assessing hip flexors and extensors, the participant was instructed to lie supine on the positioning chair with the hip to be tested closest to the dynamometer (Fig 1). Also, for assessing hip abductors and adductors, the participant was instructed to assume a side-lying position on the positioning chair with the limb to be tested on the top and the opposite limb flexed at the knee (Fig 2). The chair and dynamometer were adjusted so that the shaft aligned with the axis of rotation of the hip.

Fig 1.

(A) Hip flexion. (B) Hip extension.

Fig 2.

(A) Hip abduction. (B) Hip adduction.

The axis of rotation of the hip joint was adjusted to the level of the greater trochanter during assessing hip flexors and extensors, but it was adjusted at the level of the anterior superior iliac spine during assessing hip abductors and adductors.21., 22. The ROM limits were set at 50° flexion, 0°extension, 45° abduction, and 0° adduction. After that, gravitational correction was performed21 and concentric mode of muscle contraction was selected. Finally, the participant was instructed to push and pull the tested hip up and down as hard and as fast as possible for 5 successive repetitions. All these steps were done bilaterally for both dominant and nondominant sides.

One-way within-subject multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted in the current study to test the effect of leg dominance as an independent variable with 2 levels, dominant and nondominant, on 4 dependent variables: isokinetic PT values of the hip flexors, extensors, abductors, and adductors. Mauchly’s sphericity test was insignificant, indicating homogeneity of the within-subject factor. All statistical measures were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 20 for Windows (SPSS; IBM Corp, Armonk, New York). The level of significance for all statistical tests was set at P < .05.

Results

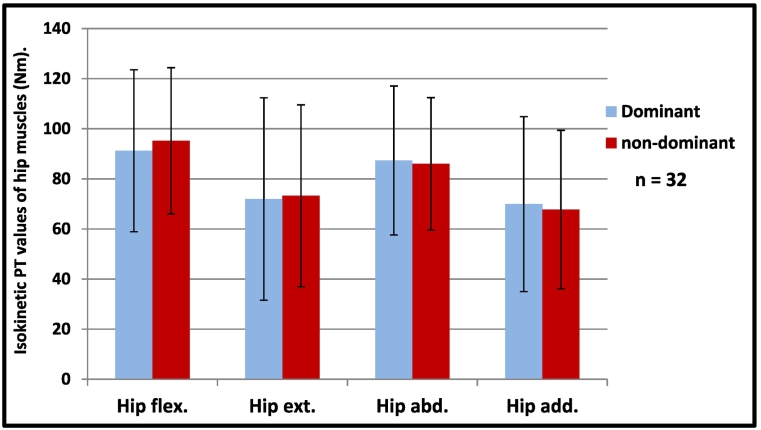

One-way within-subject multivariate analysis of variance revealed that there were no statistically significant differences between the dominant and nondominant legs for all tested hip muscles (P > .05). Descriptive statistics (mean ± standard deviation) for isokinetic PT values of hip flexors, extensors, abductors, and adductors in the dominant side leg were 91.22 ± 32.34, 71.96 ± 40.41, 87.35 ± 29.75, and 69.92 ± 34.91 Nm, respectively. Meanwhile, those of the nondominant leg were 95.23 ± 29.20, 73.28 ± 36.31, 85.99 ± 26.42, and 67.74 ± 31.63 (Table 1 and Fig 3).

Table 1.

Descriptive and Inferential Statistics of Isokinetic PT Values (Nm) of Hip Muscles for Dominant and Nondominant Sides

| Variable | Limb | Mean | Standard Deviation | F Value | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hip flexors | Dominant | 91.22 | 32.34 | 1.12 | .30 |

| Nondominant | 95.23 | 29.20 | |||

| Hip extensors | Dominant | 71.96 | 40.41 | 0.81 | .81 |

| Nondominant | 73.28 | 36.31 | |||

| Hip abductors | Dominant | 87.35 | 29.20 | 0.73 | .73 |

| Nondominant | 85.99 | 26.42 | |||

| Hip adductors | Dominant | 69.92 | 34.91 | 0.55 | .55 |

| Nondominant | 67.74 | 31.63 |

Fig 3.

Descriptive statistics of isokinetic PT values (Nm) for hip muscles in dominant and nondominant legs. abd, abduction; add, adduction; ext, extension; flex, flexion; PT, peak torque.

Discussion

The current study revealed no significant differences in all measured hip muscle strengths between dominant and nondominant legs. Most previous studies supported the current study results. Holmes and Alderink23 evaluated isokinetic strength of the quadriceps femoris and hamstring muscles at 60°/s and 180°/s in high school-aged students. They found no significant differences in muscle strengths between dominant and nondominant legs at both tested speeds. Burnie and Brodie24 determined that isokinetic knee flexion and extension strength differences did not exist between the dominant and nondominant legs in preadolescent males. Negligible differences were found between the dominant and nondominant isokinetic leg strength for knee flexion and extension, hip flexion and extension, and hip abduction and adduction in university soccer players.25 In addition, no difference was detected by Neumann et al26 between right and left isometric hip abduction torque across multiple hip angles in young adult men and women. Similar to the current study, Greenberger et al27 evaluated isokinetic concentric knee extensor strength at 240°/s in 20 male and female students and reported no significant differences between the dominant and nondominant legs.

Furthermore, isokinetic knee extensor and flexor strength of 76 male and female students at 60°/s was evaluated by Spry et al.28 They reported no significant differences between the legs. Lucca and Kline29 tested knee extensors and flexors as well. Concentric strength of 54 male and female students was evaluated using the Cybex II isokinetic dynamometer at 60, 120, and 240°/s. The authors reported no significant differences between the legs, suggesting that the legs have less opportunity to develop asymmetric strength and dexterity because lower-extremity work (eg, walking, running, stair climbing) is commonly bilateral. Kobayashi et al30 revealed no significant differences in the isokinetic strength of knee extensors between dominant and nondominant legs. Interestingly, a systematic review by McGrath et al14 also revealed no significant differences (P = .57) in isokinetic quadriceps and hamstring muscles strengths between dominant and nondominant legs. This systematic review searched the MEDLINE, CINAHL, and EMBASE databases, and the authors recommended further research to quantify asymmetries.

In contrast to these findings, Hunter et al31 found slightly higher dominant knee extension isometric torque (128.1 ± 3.0 Nm) compared with the nondominant leg (122.3 ± 3.0 Nm) in 217 women between ages 20 and 89 years. These studies measured unilateral strength in a non–weight-bearing stance. Measurement of unilateral leg strength in a weight-bearing stance could provide the most meaningful information to predict the participant’s functional capability owing to the specificity between the strength test and weight-bearing activities. Results from a weight-bearing strength test could be used to help determine the athlete’s capability for the return to sport participation or the return of an individual to higher demanding activities of daily living. This study differs from the current study in the method of testing muscle strength. The authors tested isometric muscle strength rather than isokinetic strength. In isometric testing, muscle strength is tested at specific angles and not throughout the entire ROM, unlike isokinetic testing. In addition, this isometric test angle may be varied in both limbs, causing a small variation in strength of both limbs affecting the accuracy of measurement.

Kellis et al32 also found that the isokinetic peak torque of knee flexors in the dominant leg was significantly higher than that of the nondominant at all testing speeds in young soccer players (P < .05). They confirmed that leg dominance had a greater effect on strength gain in soccer players. In the current study, nonathlete participants have the same opportunity for muscle strength gain in both dominant and nondominant legs. Therefore, the results of Kellis et al oppose the current study results.

In addition, Siqueira et al10 investigated isokinetic concentric knee extensor and flexor strength in the dominant and nondominant legs of 3 groups: nonathletes, jumpers, and runners or sprinters. After testing participants on the Cybex 6000 at 60°/s and 240°/s, the findings revealed that the dominant knee flexors were significantly stronger than the nondominant flexors at 60°/s in nonathletes (P < .05). Although the dominant knee extensor strength was higher, the difference was not statistically significant in nonathletes (P > .05). In jumpers and runners, the nondominant knee extensors were significantly stronger than dominant knee extensors at 240°/s (P < .05). These results show that there was a small tendency toward asymmetry with prevalence of the dominant side. These differences may be related to the prevailing function of each limb in locomotion. The nondominant limb has a higher support function, requiring greater action of the knee extensors in absorbing power (to restrain movements) in relation to the other leg during the mean stance phase. The dominant leg has a propulsion function, and during the final stance phase, greater muscular activity and high power development occurs in the hip and ankle compared with that in the nondominant limb.33

Jacobs et al34 examined the strength and fatigability of the hip abductors in the dominant and nondominant legs. Unlike the current study, they did not perform isokinetic testing in their study. Participants performed 3 5-second maximal voluntary isometric contraction trials of the hip abductors with the dominant and nondominant legs. After the maximal strength trials, participants performed a submaximal (50% of maximal voluntary isometric contraction) 30-second fatigue trial with each leg. The results revealed that hip abductor strength differences existed between the dominant and nondominant legs. Although this study focused on hip joint like the current study, not all hip muscles were assessed. Also, muscle strength was assessed using a different method of assessment than the method used in the current study. This explains the differences in hip abductor strength, which were found between dominant and nondominant legs. Until now, there have been debates and controversial results concerning the differences in hip muscle strengths between limbs.

Limitations

One of the limitations to this study was the lack of applying power analysis before starting the study. Power analysis should have been done to show the minimum sample size necessary to power the statistics used in the study. The other limitation to this study was that the muscles and movements were tested in single planes of movement. The concept of difference in strength may hold true in situations where several muscles are firing simultaneously in different manners (concentric, isometric, eccentric) to move a human in a weight-bearing manner. Based on the previous studies investigating the effect of leg dominance on lower limb symmetry and muscle balance between the 2 sides, future studies concentrating on hip muscle strength assessment are recommended for both athlete and nonathlete populations. The hip joint works in harmony with other joints (knee and ankle) in the kinetic chain. Therefore, special care should be administered to investigate the hip joint and address it in rehabilitation of limb asymmetry.

Conclusion

This study showed that hip muscle strength does not appear to be affected by leg dominance in healthy adults. This conclusion may be used as normative data for those who have differences in muscle strength between involved and uninvolved sides. Also, the results confirm the symmetry between both limbs in healthy people. Therefore, disturbances in muscle strength owing to specific pathology should be taken in consideration. Furthermore, this suggests that intervention programs should consider symmetry and muscle balance between both sides of the body.

Practical Applications

-

•

Hip flexors and extensors were tested in a supine lying position, whereas hip abductors and adductors were tested in a side-lying position during concentric contraction.

-

•

For those tested in this study, no statistically significant differences were found between the dominant and nondominant sides for all tested hip muscles.

-

•

Leg dominance does not appear to affect hip muscle strength in healthy adults.

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

No funding sources or conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

Contributorship Information

Concept development (provided idea for the research): A.M.A.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): A.M.A.

Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results): A.M.A.

Literature search (performed the literature search): A.M.A.

Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): A.M.A.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking): A.M.A.

References

- 1.Oda N. Kyoto University Press; Kyoto, Japan: 1998. The Right and Left It2 Exercise. [in Japanese] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Champan J, Champan LJ, Allen J. The measurement of foot preference. Neuropsychologia. 1987;25(3):579–584. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(87)90082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohtani K. A study of relationship between referred foot and long jump performance. Jpn J Sport Methodol. 1996;9(3):141–147. [in Japanese] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohtsuki T. Neuro-coordination of voluntary muscular strength in humans. In: Miyashita M, Kagaya J, editors. Science and Mechanisms in the Human Body. Kyorin Shoten; Tokyo, Japan: 1997. [in Japanese] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pincivero D, Lephart S, Karunakara R. Relation between open and closed kinematic chain assessment of knee strength and functional performance. Clin J Sports Med. 1997;7(1):11–16. doi: 10.1097/00042752-199701000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knapik JJ, Bauman CL, Jones BH, Harris JM, Vaughan L. Preseason strength and flexibility imbalances associated with athletic injuries in female collegiate athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(1):77–81. doi: 10.1177/036354659101900113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anker LC, Weerdesteyn V, van Nes IJW, Nienhuis B, Straatman H, Geurts ACH. The relation between postural stability and weight distribution in healthy subjects. Gait Posture. 2008;27(3):471–477. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahnama N, Lees A, Bambaecichi E. A comparison of muscle strength and flexibility between the preferred and non-preferred leg in English soccer players. Ergonomics. 2005;48(11-14):1568–1575. doi: 10.1080/00140130500101585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Croisier JL, Forthomme B, Namurois MH, Vanderthommen M, Crielaard JM. Hamstring muscle strain recurrence and strength performance disorders. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(2):199–203. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300020901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siqueira CM, Pelegrini FR, Fontana MF, Greve JD. Isokinetic dynamometry of knee flexors and extensors: comparative study among nonathletes, jumper athletes and runner athletes. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo. 2002;57(1):19–24. doi: 10.1590/s0041-87812002000100004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valderrabano V, Nigg BM, Nat SC. Muscular lower leg asymmetry in middle-aged people. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28(2):242–249. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2007.0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lanshammar K, Ribom EL. Differences in muscle strength in dominant and non-dominant leg in females aged 20-39 years – a population-based study. Phys Ther Sport. 2011;12(2):76–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rezaei M, Ebrahimi I, Vassaghi-Gharamaleki B. Isokinetic dynamometry of the knee extensors and flexors in Iranian healthy males and females. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2014;7(28):108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGrath TM, Waddingtong G, Scarcell JM. The effect of limb dominance on lower limb functional performance--a systematic review. J Sports Sci. 2016;34(4):289–302. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2015.1050601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilkerson B, Colston A, Short N, Neal L, Hoewischer E, Pixley J. Neuromuscular changes in female collegiate athletes resulting from a plyometric jump-training program. J Athl Train. 2004;39(1):17–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertocci G, Frost K, Burdett R, Wassinger C, Fitzgerald S. Isokinetic performance after total hip replacement. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;83(1):1–9. doi: 10.1097/01.PHM.0000098047.26314.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drouin J, Valovich-McLeod T, Shultz S, Gansneder B, Perrin D. Reliability and validity of the Biodex system 3 pro isokinetic dynamometer velocity, torque and position measurements. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004;91(1):22–29. doi: 10.1007/s00421-003-0933-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orri JC, Darden GF. Technical report: reliability and validity of iSAM 9000 isokinetic dynamometer. J Strength Cond Res. 2008;22(1):310–317. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31815fa2c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thorp L, Wimmer M, Foucher K, Sumner D, Shakoor N, Block J. The biomechanical effects of focused muscle training on medial knee loads in OA of the knee: a pilot proof of concept study. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2010;10(2):166–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yahiaa D, Jribi A, Ghroubia D, Elleuchb D, Bakloutic D. Elleucha D. A study of isokinetic trunk and knee muscle strength in patients with chronic sciatica. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2011;53(4):239–249. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dugailly B, Brassinnea D, Pirottea D, Mourauxa V, Feipelc D, Klein P. Isokinetic assessment of hip muscle concentric strength in normal subjects: a reproducibility study. Isokinet Exerc Sci. 2005;13(12):129–137. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teng W, Keong C, Ghosh A, Thimurayan V. Effects of a resistance training program on isokinetic peak torque and anaerobic power of 13-16 years old taekwondo athletes. JSHS. 2008;2(2):111–121. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holmes JR, Alderink GJ. Isokinetic strength characteristics of the quadriceps femoris and hamstring muscles in high school students. Phys Ther. 1984;64(6):914–918. doi: 10.1093/ptj/64.6.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burnie J, Brodie D. Isokinetic measurement in preadolescent males. Int J Sports Med. 1986;7(4):205–209. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1025759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masuda K, Kikuhara N, Takahashi H, Yamanaka K. The relationship between cross-sectional area and strength in various isokinetic movements among soccer players. J Sports Sci. 2003;21(10):851–858. doi: 10.1080/0264041031000102042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neumann D, Soderberg G, Cook T. Comparison of maximal isometric hip abductor muscle torque between sides. Phys Ther. 1988;68(4):496–507. doi: 10.1093/ptj/68.4.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenberger HB, Peterno MV. Relationship of knee extensor strength and hopping test performance in the assessment of lower extremity function. JOSPT. 1995;22(5):202–206. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1995.22.5.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spry S, Zebas C, Visser M. What is leg dominance? In: Hamill J, editor. Bio-mechanics in Sport XI. Proceedings of the XI Symposium of the International Society of Biomechanics in Sports. 1993. pp. 165–168. Amherst, MA: International Society of Biomechanics in Sports. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lucca JA, Kline KK. Effects of upper and lower limb preference on torque production in the knee flexors and extensors. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1989;11(5):202–207. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1989.11.5.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobayashi Y, Kubo J, Matsubayashi T, Matsuo A, Kobayashi K, Ishii N. Relationship between bilateral differences in single-leg jumps and asymmetry in isokinetic knee strength. J Appl Biomech. 2013;29(1):61–67. doi: 10.1123/jab.29.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunter S, Thompson M, Adams R. Relationships among age-associated strength changes and physical activity level, limb dominance, and muscle group in women. J Gerontol B Sci. 2000;55(6):264–273. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.6.b264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kellis S, Gerodimos V, Kellis E, Manou V. Bilateral isokinetic concentric and eccentric strength profiles of the knee extensors and flexors in young soccer players. Isokinet Exerc Sci. 2001;9(2):31–39. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sadeghi H, Allard P, Duhaime M. Functional gait asymmetry in able-bodied subjects. Hum Movement Sci. 1997;16(1):243–258. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobs C, Uhl TL, Seeley M, Sterling W, Goodrich L. Strength and fatigability of the dominant and nondominant hip abductors. J Athl Train. 2005;40(3):203–206. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]