Abstract

The opioid epidemic has increased hospital admissions for serious infections related to opioid abuse. Our findings demonstrate that addiction medicine consultation is associated with increased treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD), greater likelihood of completing antimicrobial therapy, and reduced readmission rates among patients with OUD and serious infections requiring hospitalization.

Keywords: opioids, readmissions, bacterial infections, opioid use disorder, addiction

The current opioid epidemic represents a significant burden on the healthcare system. Patients admitted for medical complications of opioid use disorder (OUD) have greater lengths of stay and higher readmission rates compared with the general population [1–3]. Some of the most serious medical complications of opioid use, particularly injection drug use (IDU), are infectious in nature, including bloodstream infections, infective endocarditis, osteomyelitis, epidural abscess, septic arthritis, necrotizing fasciitis, and myositis [1, 4]. These diagnoses generally warrant treatment with prolonged parenteral antimicrobial therapy.

For patients without a history of OUD, outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) often occurs in the patient’s home or a skilled nursing facility. However, patients who inject drugs are often ineligible to receive OPAT and therefore have to complete their antimicrobial therapy in an inpatient setting [5]. These prolonged admissions are challenging for patients and are frequently complicated by opioid cravings and withdrawal, prompting many patients to leave against medical advice (AMA) prior to completing appropriate therapy [6, 7]. Readmissions for severe complications of incompletely treated infections are common in this population, dangerous for the individual patient, and costly to the healthcare system [1]. The objective of this study was to determine whether inpatient consultation with an addiction medicine specialist improves clinical outcomes and reduces readmission rates for patients hospitalized with severe infectious complications of OUD.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective chart review of patients admitted between January 2016 and January 2018 to Barnes-Jewish Hospital, a 1400-bed, academic, tertiary care center in St Louis, Missouri. Electronic medical records (EMRs) of all patients who received infectious disease (ID) consultation were examined, identifying those with International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) discharge diagnosis codes corresponding with IDU or OUD (Supplementary Table 1) and ICD-10 diagnosis codes for serious infections that generally require prolonged parenteral antimicrobials (Supplementary Table 2). Admissions were then individually chart reviewed by an author (L. R. M.). Patient hospitalizations were included only if all of the following criteria were met: (1) infection was attributed to IDU or OUD by the ID consultant; (2) a prolonged course of parenteral antimicrobial therapy (defined as >2 weeks) was recommended by the ID consultant; and (3) the patient was not able to receive OPAT. Patients discharged to skilled nursing facilities, long-term care facilities, or able to receive parenteral antimicrobial therapy at dialysis centers were excluded from this review (n = 47) as they were able to receive intravenous antibiotics outside of the hospital. Each admission was treated as an independent event; therefore, some patients were included in the study more than once.

Consultation with an addiction medicine physician was captured by billing data and verified via review of the EMR. Outcomes of interest that were analyzed were completion of parenteral antimicrobial therapy (assessed by comprehensive review of the ID consultation notes, medication administration records, and physician discharge summaries); receipt of medication-assisted treatment (MAT), comprised of buprenorphine, methadone, or either oral or intramuscular naltrexone (assessed by review of the medication administration history in the EMR); and mortality (assessed using both the EMR and the National Social Security Death Index). Patient demographics, clinical data, and microbiology data pertaining to acute care hospitalization for serious infection, and evidence of subsequent emergency department (ED) visits and/or hospitalization were collected using the EMR. This review included screening ED visits and readmissions within 90 days of discharge at any of 15 hospitals in the BJC HealthCare system as well as 20 neighboring hospitals in the St Louis metropolitan region. All hospital readmissions were reviewed and were noted to be related to the patient’s OUD or recent infectious complications, with the exception of admissions for normal spontaneous delivery of an infant, which were excluded from the analysis.

EMR data were merged and cleaned using Statistical Analytics Software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Descriptive statistics were performed with Prism 7 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, California). Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Fisher exact tests were used for statistical significance testing for categorical variables. Age was compared between patients who received an addiction medicine consultation and those who did not receive an addiction medicine consultation using the Mann-Whitney U test. All tests for significance were 2-tailed, with P values < .05 considered significant. Kaplan-Meier estimates were used to describe the survival distribution for time to readmission. The log-rank statistic was used to test the difference in time to readmission. The total intensive care unit (ICU) days during readmissions were summed for comparison purposes.

This study was approved by the Washington University Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Of the 125 patients who met inclusion criteria, 38 (30.4%) patients received an addiction medicine consultation. Demographic characteristics and clinical data of patients are shown in Table 1. Hepatitis C virus infection was more common among the addiction medicine consultation group (ADC) than among those not seen by addiction medicine (NADC). Other comorbidities were evenly distributed between both groups.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Intravenous Drug Use Admitted to the Hospital With a Serious Infection Who Received an Addiction Medicine Consultation Compared With Patients Who Did Not Receive an Addiction Medicine Consultation

| Characteristic | Addiction Medicine Consultation (n = 38) | No Addiction Medicine Consultation (n = 87) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| African American | 13 (34) | 35 (40) | .555 |

| Female | 21 (55) | 46 (52) | .847 |

| Median age, y (range) | 36 (19–63) | 35 (19–67) | .952 |

| IV heroin use | 37 (97) | 81 (93) | .674 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| HIV infection | 1 (2) | 2 (2) | >.999 |

| HCV infection | 25 (66) | 34 (39) | .007 |

| Endocarditis | 10 (26) | 25 (28) | .832 |

| Prior valve replacement | 7 (18) | 13 (15) | .607 |

| Diabetes | 2 (5) | 3 (3) | .639 |

| Malignancy | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | .091 |

| COPD | 3 (7) | 5 (6) | .698 |

| Hypertension | 2 (5) | 2 (2) | .584 |

| Osteomyelitis | 4 (11) | 5 (6) | .453 |

| Pregnant | 1 (3) | 2 (2) | >.999 |

| Bipolar disorder | 2 (5) | 6 (7) | >.999 |

| CHF | 2 (5) | 1 (5) | .216 |

| None | 4 (11) | 16 (18) | .426 |

| Causative organisma | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 29 (76) | 58 (67) | .301 |

| Candida species | 2 (5) | 6 (7) | >.999 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 1 (3) | 5 (6) | .666 |

| Culture negative | 2 (5) | 9 (10) | .502 |

| Other organismb | 4 (11) | 9 (10) | >.999 |

| Admission diagnoses | |||

| Osteomyelitis | 7 (18) | 19 (22) | .812 |

| Epidural abscess | 2 (5) | 7 (8) | .721 |

| Septic joint | 8 (21) | 12 (14) | .304 |

| Necrotizing fasciitis or myositis | 2 (5) | 7 (8) | .721 |

| Bacteremia | 9 (24) | 21 (24) | >.999 |

| Fungemia | 2 (5) | 6 (7) | >.999 |

| Endocarditis | 25 (66) | 43 (49) | .119 |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IV, intravenous.

aCausative organism was not mutually exclusive, so infections with multiple pathogens were counted for each pathogen.

bOther organisms identified included Staphylococcus epidermidis, Serratia marcescens, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Streptococcus viridans, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Veillonella species, Achromobacter species, and Haemophilus influenzae.

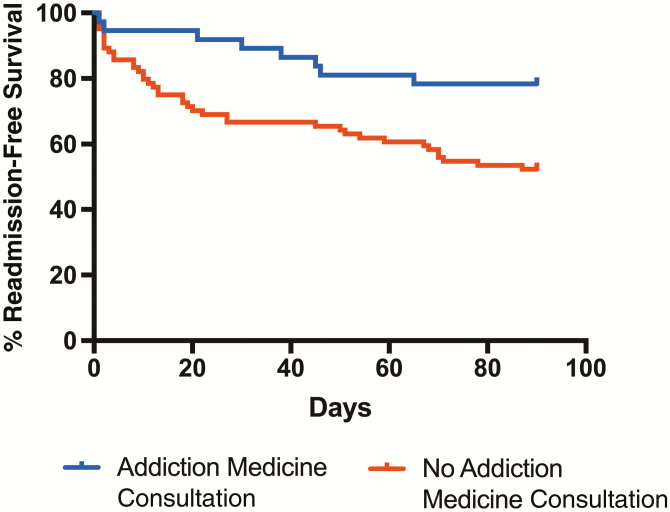

Thirty-three (86.8%) ADC and 15 (17.2%) NADC patients (OR, 31.68 [95% CI, 10.25–81.29]) received MAT (Table 2). Addiction medicine consultation was associated with a significantly greater rate of completion of parenteral antimicrobial therapy (30 [78.9%] ADC patients vs 35 [40.2%] NADC patients; OR, 5.57 [95% CI, 2.25–13.07]). AMA discharges and elopements were also significantly lower in the ADC group (6 [15.8%] ADC patients vs 43 [49.4%] NADC patients; OR, 0.19 [95% CI, .08–.48]). Patients who received an addiction medicine consultation were less likely to be readmitted within 90 days of discharge, with a subdistribution hazard ratio of 0.378 (95% CI, .21–.69; Figure 1). Readmitted ADC patients accounted for a total of 9 days in the ICU, compared to 88 days for readmitted NADC patients.

Table 2.

Outcomes of Patients With Intravenous Drug Use Admitted to the Hospital With a Serious Infection Who Received an Addiction Medicine Consultation Compared With Patients Who Did Not Receive an Addiction Medicine Consultation

| Outcome | Addiction Medicine Consultation (n = 38) | No Addiction Medicine Consultation (n = 87) | OR (95% CI) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Received MAT | 33 (87) | 15 (17) | 31.68 (10.25–81.29) | <.0001 |

| Completed antibiotic therapy | 30 (79) | 35 (40) | 5.57 (2.25–13.07) | <.0001 |

| Elopement or discharged AMA | 6 (16) | 43 (49) | 0.19 (.08–.48) | .0003 |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: AMA, against medical advice; CI, confidence interval; MAT, medication-assisted treatment; OR, odds ratio.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier plot showing percentage of readmission-free survival according to addiction medicine consultation. The survival estimates between the 2 groups is statistically significant (P = .0085; log-rank test).

DISCUSSION

In our study, patients with a diagnosis of OUD admitted to the hospital with an infection requiring prolonged antimicrobial therapy and who received an addiction medicine consultation had better outcomes than those who did not receive an addiction medicine consultation. Specifically, patients seen by an addiction medicine specialist were more likely to receive MAT, more likely complete their parenteral antibiotic treatment, and less likely to be discharged AMA or elope from the hospital. Furthermore, patients seen by the addiction medicine service had significantly fewer readmissions within 90 days after discharge. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that addiction medicine consultations improve patient care in individuals with OUD who are admitted for serious infections requiring prolonged hospitalizations for intravenous antibiotics.

These findings underscore the importance of addressing addiction issues in patients hospitalized with infectious complications associated with OUD. Hospitalizations for serious infections stemming from OUD may represent a high-risk touchpoint and present an opportunity to deliver interventions to reduce opioid-related mortality. Addiction medicine consultation during these hospitalizations may create an opportunity to initiate and engage patients in treatment, discuss harm-reduction strategies such as overdose education, and render significant financial savings as well as improve patient care [8]. MAT is well known to improve outcomes in patients with OUD, and our data further reinforce that medications for OUD are an integral part of the care of OUD-related infections [9, 10].

This study had several limitations. This was a retrospective study conducted at a single tertiary care, academic medical center, so our data may not be generalizable to other hospitals. An additional limitation is the use of ICD codes to identify patients, as it is possible that some patients were missed due to failures in documentation and coding. Selection bias could also be present; addiction medicine consultation was most likely to be nonrandom and based on a patient’s clinical presentation and prognosis. Additionally, it is also possible that patients who did not receive MAT refused addiction medicine consultation or declined treatment. Therefore, lack of appropriate consultation may not represent a missed opportunity to intervene by the admitting providers.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates substantial benefits from addiction medicine consultation in hospitalized patients with OUDs who require long-term parenteral antibiotics. ID providers should strongly consider consulting addiction medicine or addressing underlying opioid use as part of a multidisciplinary team approach for this challenging population.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Disclaimer. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH (grant numbers KL2TR002346, CRTCUL1RR024992, and T32 AI007172).

Potential conflicts of interest. D. K. W. has received payments from Pfizer, and personal fees from Centene, Carefusion/BD, Pursuit Vascular, and PDI. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Ronan MV, Herzig SJ. Hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and associated serious infections increased sharply, 2002-12. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016; 35:832–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fleischauer A, Ruhl L, Rhea S, Barnes E. Hospitalizations for endocarditis and associated health care costs among persons with diagnosed drug dependence—North Carolina, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017; 66:569–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clark RE, Baxter JD, Aweh G, O’Connell E, Fisher WH, Barton BA. Risk factors for relapse and higher costs among medicaid members with opioid dependence or abuse: opioid agonists, comorbidities, and treatment history. J Subst Abuse Treat 2015; 57:75–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Walley AY, Paasche-Orlow M, Lee EC, et al. Acute care hospital utilization among medical inpatients discharged with a substance use disorder diagnosis. J Addict Med 2012; 6:50–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rapoport A, Fischer L, Santibanez S, Beekmann S, Polgreen P, Rowley C. Infectious diseases physicians’ perspectives regarding injection drug use and related infections, United States, 2017. Open Forum Infect Dis 2018; 5:ofy132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rosenthal ES, Karchmer AW, Theisen-Toupal J, Castillo RA, Rowley CF. Suboptimal addiction interventions for patients hospitalized with injection drug use–associated infective endocarditis. Am J Med 2016; 129:481–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Haber PS, Demirkol A, Lange K, Murnion B. Management of injecting drug users admitted to hospital. Lancet 2009; 374:1284–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jicha C, Saxon D, Lofwall MR, Fanucchi LC. Substance use disorder assessment, diagnosis, and management for patients hospitalized with severe infections due to injection drug use [manuscript published online ahead of print 24 September 2018]. J Addict Med 2018. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fullerton CA, Kim M, Thomas CP, et al. Medication-assisted treatment with methadone: assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv 2014; 65:146–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thomas CP, Fullerton CA, Kim M, et al. Medication-assisted treatment with buprenorphine: assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv 2014; 65:158–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.