Abstract

Background

Low baseline plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) is associated with increased risk of acute respiratory infections, but its association with long-term risk of sepsis remains unclear.

Methods

We performed a case-cohort analysis of participants selected from the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study, a US cohort of 30239 adults aged ≥45 years. We measured baseline plasma 25(OH)D in 711 sepsis cases and in 992 participants randomly selected from the REGARDS cohort. We captured sepsis events by screening records with International Classification of Disease methods and then adjudicating clinical charts for significant, suspected infection and severe inflammatory response syndrome criteria on presentation.

Results

In the study sample, the median age of participants was 65.0 years, 41% self-identified as black, and 45% were male. Mean plasma 25(OH)D concentration was 25.8 ng/mL; for 31% of participants, it was <20 ng/mL. The adjusted risk of community-acquired sepsis was higher for each lower category of baseline 25(OH)D. Specifically, in a Cox proportional hazards model adjusting for multiple potential confounders, when compared to a baseline 25(OH)D >33.6 ng/mL, lower 25(OH)D groups were associated with higher hazards of sepsis (16.5–22.4 ng/mL; hazard ratio [HR]; 3.21; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.98 to 5.21 and <16.5 ng/mL; HR, 6.81, 95% CI, 3.95 to 11.73). Results did not materially differ in analyses stratified by race or age.

Conclusions

In the REGARDS cohort of community-dwelling US adults, low plasma 25(OH)D measured at a time of relative health was independently associated with increased risk of sepsis.

Keywords: sepsis, septicemia, community-acquired infection, vitamin D

We demonstrate a robust association between low baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and an increased long-term risk of subsequent community-acquired sepsis in a large cohort of US adults. This generates hypotheses regarding a modifiable risk factor for sepsis prevention.

Vitamin D has an integral role in the functioning of the innate immune system. In humans, several types of immune cells have vitamin D receptors and the intracellular enzymatic machinery to convert circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) into its biologically active form [1]. In response to invading pathogens, these immune cells absorb, activate, and utilize 25(OH)D to produce the antimicrobial cathelicidin peptide, LL-37 [2]. This microbicidal molecule of the innate immune system has activity on several bacteria, viruses, and fungi; can disrupt biofilms; promotes phagocytosis and subsequent oxidative burst; and induces chemotaxis of other immune cells to sites of infection [3–7].

The clinical applications of these mechanistic discoveries are encouraging, with a recent individual-level metaanalysis of randomized, controlled trials demonstrating that vitamin D supplementation reduces the risk of acute respiratory infections [8]. Additionally, a recent metaanalysis of 10 observational studies demonstrated an association between low vitamin D status and sepsis [9]. However, there are significant limitations of the studies in that metaanalysis that we sought to address in the present study. Specifically, several of the studies measured vitamin D at admission to the intensive care unit or hospital, when 25(OH)D can act as an acute-phase reactant and low measurements may reflect a response to acute inflammation rather than depleted baseline stores [10–13]. This introduces the possibility of reverse causality in the interpretations of the associations in those studies. Additionally, the studies that comprise the majority of the metaanalyses’ pooled estimate constructed their cohorts from patients who were critically ill and had a vitamin D concentration checked by a provider in the healthcare system sometime in the 7–365 days prior to critical illness [14–18]. This may introduce a bias by indication and further limits generalizability to the critically ill. Finally, these latter cohort studies accounted for >90% of the weight of the pooled estimates and all drew from overlapping years of a clinical data warehouse from the same 2 northeastern US hospitals, limiting the generalizability of the association outside of that healthcare system and study group [14–18].

In our study, we address the question of whether low baseline vitamin D concentrations, measured in a sample of community-dwelling US adults at a time of relative health, are associated with increased risk of a subsequent community-acquired sepsis event. Our rationale was that measuring vitamin D at a time of relative health in a community-based cohort may make any findings more pertinent to understanding the potential role of treating low vitamin D concentrations in population-based strategies to prevent sepsis in older adults.

METHODS

We used a prospective case-cohort design. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Alabama at Birmingham approved this study, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Setting—the REGARDS Cohort

The REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) cohort includes 30239 adults aged ≥45 years from the 48 contiguous US states and the District of Columbia. The cohort was designed to characterize US geographic and racial disparities in stroke mortality and is comprised of community-dwelling adults at a stable phase of health [19]. REGARDS oversampled individuals from the southeastern United States, with 20% of the cohort originating from the “stroke buckle” (coastal plains of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia) and 30% from the “stroke belt” (the remainder of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia plus Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, and Arkansas). Enrollment of REGARDS participants occurred between 2003 and 2007. The study excluded individuals of races other than black or white, undergoing active cancer treatment, residing in or on a waiting list for a nursing home, and having inability to communicate in English [19].

Baseline participant information including medical history, functional status, health behaviors, physical characteristics (height, weight), physiologic measures (blood pressure, pulse, electrocardiogram), current medications, diet, family history of diseases, psychosocial factors, and prior residences was collected. Blood and urine specimens were also collected from each participant.

Exposures and Outcomes

The primary exposure was baseline plasma 25(OH)D, sampled at participants’ baseline visit and measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Immunodetection Systems, Fountain Hills, AZ) in the Laboratory for Clinical Biochemistry Research at the University of Vermont. The assay had a detectable range of 5–150 ng/mL and coefficients of variation between 8.8% and 12.5%. The study also collected other patient characteristics, including demographic information, health behaviors, body-mass index (BMI), baseline medical conditions, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) (additional details in Supplementary Materials, Appendix 1).

The primary outcome was a sepsis event captured through 31 December 2012. The REGARDS study contacted all study participants by telephone at 6-month intervals to identify the date, location, and attributed reason for all hospitalizations. From these reports, study personnel obtained hospital records for all hospitalizations attributed to a serious infection using International Classification of Disease (ICD) taxonomy of Angus et al [20]. Two trained research personnel, unaware of 25(OH)D status, performed a structured review of hospital records to confirm the presence of a serious infection as a major reason for hospital presentation and to identify pertinent physiologic measures and laboratory assay test results from the first 28 hours of hospitalization. Sepsis events included hospitalizations with clinical measures satisfying 2 of 4 severe inflammatory response syndrome criteria [21]. Prior review of 1349 records demonstrated excellent interrater agreement for the classification of serious infection (kappa = 0.92) and sepsis (kappa = 0.90).

Derivation of Case-Cohort Samples

We used a case-cohort study design to provide an unbiased estimate of the relative hazard of the outcome without requiring measurement of biomarkers in all REGARDS participants [22]. The subcohort sample (comparison group) was selected using stratified sampling to ensure sufficient representation among demographic groups. All participants with at least 1 follow-up contact (n = 29653) were categorized into 20 strata based on age (45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75–84, ≥85 years), race (black or white), and sex (male or female) [23]. In each stratum, participants were randomly selected to fulfill the desired distribution: 50% black, 50% white, 50% female, 50% male, 20% age 45–54, 20% age 55–64, 25% age 65–74, 25% age 75–84, and 10% age ≥85. Weights were calculated to allow upweighting of cohort random sample participants and cases back to the original sample. The subcohort was sampled without regard to 25(OH)D status or sepsis outcomes. However, participants were later excluded from a subcohort for insufficient aliquot volume or extreme 25(OHD) measurements. For the sepsis cases, due to finite resources, we selected a 50% random sample of all REGARDS participants who developed sepsis for measurement of 25(OH)D in stored plasma samples to be eligible for this study. Given the sample sizes of case and subcohort samples, we were powered to detect a minimal hazard ratio of 1.8 comparing the highest to the lowest quintile of 25(OH)D [24].

Statistical Analyses

We first categorized plasma 25(OH)D concentrations into 5 quantiles to create approximately equally sized samples within each categorization to facilitate multivariable analyses. Then, descriptive statistics were used to compare participant characteristics across quintiles of 25(OH)D within the cohort random sample using appropriate weights to account for the stratified sampling design. After confirming the proportionality of hazards, 2 weighted Cox regression models for case-cohort studies [25] were used to estimate the hazard of incident sepsis as a function of baseline 25(OH)D. The first model was unadjusted, and the second model was adjusted for covariates that were decided a priori. The adjusted model included age, sex, race, region of recruitment, annual family income, educational attainment, season of blood draw, current smoking, BMI, diabetes status, physical activity, chronic pulmonary disease status, chronic kidney disease status, and log-transformed hsCRP. In both models, 25(OH)D was analyzed in quintiles, with >33.6 ng/mL as the referent group. In additional analyses, we repeated the analyses using traditional cut-points for vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency for skeletal outcomes (<20 ng/mL, 20–39 ng/mL, ≥30 ng/mL) and at a dichotomous cut-point at 20 ng/mL. Given wide variability in the distribution of 25(OH)D concentrations by age and race, we performed stratified analyses by these factors. All analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

After excluding 63 participants who had missing 25(OH)D concentrations and 5 who had a history of sepsis prior to the baseline visit, we included 711 sepsis cases (662 of whom arose outside the random subcohort and 49 of whom arose from the random subcohort). Of the original 1104 in the random subcohort, 1041 had an available 25(OH)D and 49 had a sepsis event, leaving the final size of the comparison subcohort group at 992.

Table 1 describes the overall characteristics of participants in the subcohort and by quintile of baseline 25(OH)D. The study sample had a median age of 65.0 years (95% confidence interval [CI], 64.5 to 65.6), with 41% of the participants self-identifying as black and 55% women. Other notable characteristics of the subcohort were high prevalences of obesity, inactivity, diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, and chronic kidney disease (defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or a urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g) at baseline. Among the samples, the mean baseline plasma 25(OH)D concentration was 25.8 ng/mL, with 31% <20 ng/mL.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of REGARDS Participants, Stratified by Quintiles of Baseline 25-Hydoxyvitamin D Concentrations

| Characteristic | Quintile 1 (<16.5 ng/mL) |

Quintile 2 (16.5–22.4 ng/mL) |

Quintile 3 (22.5–27.1 ng/mL) |

Quintile 4 (27.2–33.6 ng/mL) |

Quintile 5 (>33.6 ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted N | 5561 | 5535 | 5605 | 5632 | 5637 |

| Age, years | 63.7 (62.6,64.7) | 65.7 (64.4,66.9) | 65.5 (64.3,66.7) | 65.5 (64.3,66.7) | 64.7 (63.5,65.9) |

| Male sex | 32 | 45 | 43 | 40 | 45 |

| Black | 79 | 54 | 33 | 23 | 17 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 31.6 (30.4,32.8) | 30.1 (29.3,30.9) | 28.9 (28.1,29.7) | 28.1 (27.3,28.9) | 27.1 (26.3,28.0) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 130.7 (127.8,133.6) | 128.1 (125.7,130.5) | 127.0 (124.6,129.4) | 125.9 (123.5,128.3) | 124.5 (121.9,127.1) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 78.5 (76.9,80.1) | 77.3 (75.9,78.5) | 76.1 (74.8,77.6) | 75.1 (73.6,76.6) | 74.6 (72.9,76.2) |

| Not a high school graduate | 18 | 19 | 12 | 6 | 6 |

| Income <$20000 | 25 | 21 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Smoking (current) | 24 | 11 | 12 | 4 | 17 |

| Alcohol | |||||

| None | 76 | 67 | 62 | 58 | 50 |

| Moderate | 20 | 31 | 35 | 34 | 42 |

| Heavy | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 7 |

| Exercise (none) | 49 | 36 | 29 | 27 | 28 |

| Co-morbidities | |||||

| Diabetes | 29 | 31 | 24 | 11 | 10 |

| Coronary heart disease | 14 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 18 |

| Coronary artery disease | 23 | 22 | 23 | 13 | 17 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 8 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 8 |

| Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration, ng/mL | 12.9 (12.5,13.2) | 19.4 (19.1,19.7) | 24.7 (24.5,24.9) | 30.1 (29.8,30.4) | 41.5 (40.3,42.8) |

| High-sensitivity C-reactive protein, mg/L | 2.8 [1.2,7.3] | 2.4 [0.9,4.8] | 2.0 [1.0,4.8] | 1.9 [0.9,4.5] | 1.7 [0.8,4.2] |

Values are presented as mean (95% confidence intervals), median (interquartile range), or proportion.

While mean age was similar across quintiles of 25(OH)D, there were increasing proportions of females, blacks, those without a high school diploma, and those with an income <$20000 in each successively lower 25(OH)D quintile. In regards to health behaviors, among successively lower quintiles of 25(OH)D, there were higher proportions of participants reporting inactivity. The proportion of participants reporting tobacco use at baseline was highest among the lowest and highest quintiles of 25(OH)D. Among baseline medical conditions, the prevalence of diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease was higher in lower 25(OH)D quintiles.

Associations Between Baseline 25(OH)D and Incident Sepsis

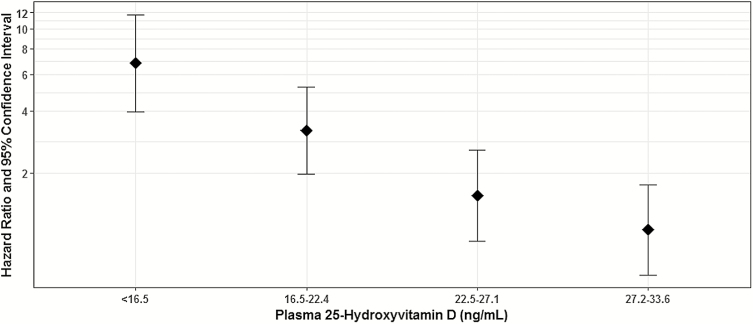

Table 2 shows the results of unadjusted and adjusted Cox proportional hazard regressions for sepsis events. In the unadjusted analysis and each of the multivariable models, when compared to the highest 25(OH)D quintile, each successively lower 25(OH)D quintile had a consecutively higher hazard for sepsis. The adjusted model controlled for age, sex, race, region of recruitment, annual family income, educational attainment, season of blood draw, current smoking, BMI, diabetes mellitus, physical activity, chronic pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, and hsCRP (Figure 1). In this model, when compared to those with 25(OH)D >33.6 ng/mL, those with 25(OH)D <16.5 ng/mL had a 6.81 higher adjusted hazard of sepsis (95%CI, 3.95 to 11.73), those with 25(OH)D 16.5–22.4 ng/mL had a 3.21 higher hazard of sepsis (95% CI, 1.98 to 5.21), and those with 25(OH)D 22.5–27.1 ng/mL had a nonsignificant 1.55 higher hazard of sepsis (95% CI, 0.93 to 2.57).

Table 2.

Association of Baseline 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentrations With Incidence of Sepsis

| Quintiles of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D | Linear Model per 1 ng/mL Lower |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| <16.5 ng/mL | 16.5–22.4 ng/mL | 22.5–27.1 ng/mL | 27.2–33.6 ng/mL | >33.6 ng/mL | ||

| N | 222 | 214 | 191 | 191 | 174 | 992 |

| Events | 285 | 162 | 120 | 75 | 69 | 711 |

| Unadjusted model | 4.30 (3.00,6.16) | 2.42 (1.67,3.51) | 1.57 (1.06,2.31) | 0.93 (0.61,1.42) | ref | 1.11 (1.09,1.14) |

| Adjusted model | 6.81 (3.95,11.73) | 3.21 (1.98,5.21) | 1.55 (0.93,2.57) | 1.06 (0.64,1.75) | ref | 1.09 (1.07,1.13) |

Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals from Cox proportional hazard models. The adjusted model includes age, sex, race, region of recruitment, annual family income, educational attainment, season of blood draw, current smoking, body mass index, diabetes status, physical activity, chronic pulmonary disease status, chronic kidney disease status, and log-transformed high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

Abbreviation: ref, referent.

Figure 1.

Associations between baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D and incident sepsis.

This is a graphical representation of the estimates from the adjusted model, reported fully in Table 2. Hazard ratios were determined from a Cox proportional hazards model adjusting for age, sex, race, region of recruitment, annual family income, educational attainment, season of blood draw, current smoking, body mass index, diabetes status, physical activity, chronic pulmonary disease status, chronic kidney disease status, and log-transformed high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

Additional Analyses

We performed several additional analyses. First, we examined the main associations utilizing traditional 25(OH)D cut-points and demonstrated findings consistent with our primary analyses (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Second, we performed an analysis stratified by age utilizing the same 25(OH)D cut-points as for the primary analyses. This demonstrated that the associations of 25(OH)D quintiles with sepsis did not differ among those aged <65 years compared to those aged ≥65 years (Supplementary Table 3). Third, we performed 2 stratified analyses by self-reported race, the first utilizing the same cut-points as our primary analysis and the second utilizing race-specific quintiles of 25(OH)D. These both demonstrated similar associations of baseline 25(OH)D with sepsis in black participants compared to white participants (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5).

DISCUSSION

In this study of participants in the REGARDS study, one of the nation’s largest population-based cohorts, we found that low baseline plasma 25(OH)D concentrations were associated with increased long-term risk of community-acquired sepsis. Specifically, when compared to a baseline 25(OH)D >33.6 ng/mL, participants at each lower category had a higher hazard of sepsis. Those in the lowest category, with a 25(OH)D <16.5 ng/mL, had a 6.81-fold higher hazard of sepsis. These results remained robust with adjustment for multiple, relevant confounders, using various 25(OH)D cut points, and when stratifying by race and age. These strong associations are consistent with literature on acute respiratory infections and generate provocative hypotheses in regards to a potentially modifiable risk factor for the increasingly recognized public health problem of sepsis.

This study lends support to the trajectory of clinical literature supporting vitamin D’s role as a modifiable risk factor in the optimal functioning of the immune system. A recent individual-level metaanalysis of nearly 11000 individuals demonstrated that daily or weekly vitamin D supplementation had a protective effect against acute respiratory infections, with a number needed to treat of 33 [8]. Furthermore, this metaanalysis demonstrated that the effect was most pronounced among those with a baseline 25(OH)D <10 ng/mL, which is consistent with the present study’s demonstrated dose-dependent association. These data specifically support the association between vitamin D and respiratory infections, the most common cause of sepsis. Additionally, in vitro and clinical data also support that the effects of vitamin D extend to other sites of infection [3–7, 17, 18, 26–30].

Our study’s findings are consistent with those of other observational studies that examined vitamin D and sepsis but significantly adds to this body of literature with several strengths in design. First, the large, diverse study cohort strengthens the generalizability of the findings to the community-dwelling US population aged >45 years. Second, given that this study measured vitamin D at the relatively healthy baseline of participants in a population-based cohort, the study minimizes potential indication bias and reverse causality that can be introduced in measuring vitamin D during acute illness [10–13] or when a provider deems that the test is clinically indicated for another reason [14–18]. Third, the study minimizes misclassification of the outcome by adjudicating sepsis events through independent chart review of clinical data rather than relying solely on ICD codes. Fourth, the large amount of data collected by the REGARDS baseline study visit allows ample adjustment for multiple, relevant confounders in the analyses [9, 29].

As with any study, this study has its weaknesses. First, we did not have 25(OH)D measurements done via liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS), which studies suggest may be the best method for measuring 25(OH)D in blood samples. Nonetheless, the assay used to measure 25(OH)D in the current study has been validated against LC-MS [31]. Second, vitamin D stores have an expected variation throughout the seasons; in this study, 25(OH)D was captured at 1 nonstandardized time point. This may introduce a nondifferential misclassification of underlying vitamin D stores that would be expected to bias associations toward the null. Third, the method used to capture sepsis through a sequential process of screening records by ICD codes and then relying on physician documentation of suspected infections is not perfectly sensitive [32]. This may introduce nondifferential misclassification of outcome, which would also be expected to bias the results toward the null. Fourth, this study does not include a nonsepsis hospitalization comparator group, and those with low vitamin D status may be more likely to be hospitalized in general. In this scenario, the demonstrated associations may partially reflect the risk of hospitalization. We attempted to minimize this by ensuring our case definition only included sepsis when it was a principle reason for the medical encounter.

Additionally, it is also possible that the observed association between lower 25(OH)D and higher risk of sepsis might be explained by low concentrations of the primary carrier protein for 25(OH)D, vitamin D binding protein (VDBP). The majority of circulating 25(OH)D is tightly bound to VDBP [33]. Because of this, circulating 25(OH)D concentrations decrease when VDBP decreases and vice versa. This is important in that VDBP is a negative acute phase reactant, falling in response to inflammation [34]. Since plasma 25(OH)D measurements largely reflect VDBP-bound 25(OH)D, low 25(OH)D concentrations may reflect decreased VDBP, perhaps acting as a sensitive marker of chronic inflammation related to general illness rather than true vitamin D deficiency. Unfortunately, we did not have measurements of VDBP in the REGARDS cohort, and so we could not account for VDBP concentrations in our analyses.

In conclusion, establishing the links between low vitamin D status and the broader category of sepsis has important public health implications at a time when agencies are increasingly trying to reduce the public health burden of sepsis. Recently, the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare added a sepsis care quality measure to its panel of hospital performance metrics, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention started a Get Ahead of Sepsis campaign [35]. In 2017 the World Health Organization officially recognized sepsis as a global public health problem and encouraged countries to develop strategies to minimize its impact [36]. Within this global context, vitamin D supplementation may potentially represent one piece of an efficacious and cost-effective preventive public health strategy for sepsis that is safe to the individual and without the risks of increasing antibiotic resistance.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We dedicate this manuscript to the memory of our dear colleague and friend Nancy S. Jenny, PhD. The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the REGARDS study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating REGARDS investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.regardsstudy.org and http://www.regardssepsis.org.

Funding. This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute for Nursing Research (R01NR012726), National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01NS080850; U01 NS041588), National Center for Research Resources (UL1-RR025777), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (U01DK102730 to O. M. G.; K23 DK114475-01 to B. P.), American Heart Association (15SFDRN25620022 to O. M. G.), and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (k08 HS025240 to J. A. K.), as well as by grants from the Center for Clinical and Translational Science and the Lister Hill Center for Health Policy of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Potential conflicts of interest. O. M. G. reports grants and personal fees from Keryx Biopharmaceuticals and personal fees from Amgen outside the submitted work. All remaining authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Baeke F, Takiishi T, Korf H, Gysemans C, Mathieu C. Vitamin D: modulator of the immune system. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2010; 10:482–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hewison M. Antibacterial effects of vitamin D. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2011; 7:337–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yim S, Dhawan P, Ragunath C, Christakos S, Diamond G. Induction of cathelicidin in normal and CF bronchial epithelial cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3). J Cyst Fibros 2007; 6:403–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Turner J, Cho Y, Dinh NN, Waring AJ, Lehrer RI. Activities of LL-37, a cathelin-associated antimicrobial peptide of human neutrophils. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1998; 42:2206–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nijnik A, Hancock RE. The roles of cathelicidin LL-37 in immune defences and novel clinical applications. Curr Opin Hematol 2009; 16:41–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hertting O, Holm Å, Lüthje P, et al. Vitamin D induction of the human antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin in the urinary bladder. PLoS One 2010; 5:e15580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kamen DL, Tangpricha V. Vitamin D and molecular actions on the immune system: modulation of innate and autoimmunity. J Mol Med (Berl) 2010; 88:441–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martineau AR, Jolliffe DA, Hooper RL, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ 2017; 356:i6583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Upala S, Sanguankeo A, Permpalung N. Significant association between vitamin D deficiency and sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Anesthesiol 2015; 15:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Flynn L, Zimmerman LH, McNorton K, et al. Effects of vitamin D deficiency in critically ill surgical patients. Am J Surg 2012; 203:379–82; discussion 82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jeng L, Yamshchikov AV, Judd SE, et al. Alterations in vitamin D status and anti-microbial peptide levels in patients in the intensive care unit with sepsis. J Transl Med 2009; 7:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Müller B, Becker KL, Kränzlin M, et al. Disordered calcium homeostasis of sepsis: association with calcitonin precursors. Eur J Clin Invest 2000; 30:823–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Su LX, Jiang ZX, Cao LC, et al. Significance of low serum vitamin D for infection risk, disease severity and mortality in critically ill patients. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013; 126:2725–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Quraishi SA, Litonjua AA, Moromizato T, et al. Association between prehospital vitamin D status and hospital-acquired bloodstream infections. Am J Clin Nutr 2013; 98:952–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Braun A, Chang D, Mahadevappa K, et al. Association of low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and mortality in the critically ill. Crit Care Med 2011; 39:671–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Braun AB, Gibbons FK, Litonjua AA, Giovannucci E, Christopher KB. Low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D at critical care initiation is associated with increased mortality. Crit Care Med 2012; 40:63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lange N, Litonjua AA, Gibbons FK, Giovannucci E, Christopher KB. Pre-hospital vitamin D concentration, mortality, and bloodstream infection in a hospitalized patient population. Am J Surg 2013; 126:640.e19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moromizato T, Litonjua AA, Braun AB, Gibbons FK, Giovannucci E, Christopher KB. Association of low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and sepsis in the critically ill. Crit Care Med 2014; 42:97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Howard VJ, Cushman M, Pulley L, et al. The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology 2005; 25:135–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med 2001; 29:1303–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bone RC, Sprung CL, Sibbald WJ. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure. Crit Care Med 1992; 20:724–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barlow WE, Ichikawa L, Rosner D, Izumi S. Analysis of case-cohort designs. J Clin Epidemiol 1999; 52:1165–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cushman M, Judd SE, Howard VJ, et al. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide and stroke risk: the reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke cohort. Stroke 2014; 45:1646–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cai J, Zeng D. Sample size/power calculation for case-cohort studies. Biometrics 2004; 60:1015–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Onland-Moret NC, van der A DL, van der Schouw YT, et al. Analysis of case-cohort data: a comparison of different methods. J Clin Epidemiol 2007; 60:350–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Quraishi SA, Litonjua AA, Moromizato T, et al. Association between prehospital vitamin D status and hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infections. J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2015; 39:47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Quraishi SA, Bittner EA, Blum L, Hutter MM, Camargo CA Jr. Association between preoperative 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and hospital-acquired infections following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. JAMA Surg 2014; 149:112–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gombart AF, Bhan I, Borregaard N, et al. Low plasma level of cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (hCAP18) predicts increased infectious disease mortality in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 48:418–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kempker JA, Magee MJ, Cegielski JP, Martin GS. Associations between vitamin D level and hospitalizations with and without an infection in a national cohort of Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Epidemiol 2016; 183:920–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shalaby SA, Handoka NM, Amin RE. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with urinary tract infection in children. Arch Med Sci 2018; 14:115–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cluse ZN, Fudge AN, Whiting MJ, McWhinney B, Parkinson I, O’Loughlin PD. Evaluation of 25-hydroxy vitamin D assay on the immunodiagnostic systems iSYS analyser. Ann Clin Biochem 2012; 49:159–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rhee C, Dantes R, Epstein L, et al. Incidence and trends of sepsis in US hospitals using clinical vs claims data, 2009–2014. JAMA 2017; 318:1241–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bikle DD, Gee E, Halloran B, Kowalski MA, Ryzen E, Haddad JG. Assessment of the free fraction of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in serum and its regulation by albumin and the vitamin D-binding protein. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1986; 63:954–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Waldron JL, Ashby HL, Cornes MP, et al. Vitamin D: a negative acute phase reactant. J Clin Pathol 2013; 66:620–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Get Ahead of Sepsis. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/sepsis/get-ahead-of-sepsis/index.html. Accessed 15 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Global Sepsis Alliance. WHA Adopts Resolution on Sepsis. Available at: https://www.global-sepsis-alliance.org/news/2017/5/26/wha-adopts-resolution-on-sepsis. Accessed 15 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.