Abstract

In this article, 23 compounds (6 and 7a–7v) were prepared and evaluated for their in vitro α-glucosidase inhibitory activity. The compounds 7d, 7f, 7i, 7n, 7o, 7r, 7s, 7u, and 7v displayed the α-glucosidase inhibition activity with IC50 values ranging from 1.68 to 7.88 µM. Among all tested compounds, 7u was found to be the most efficient, being 32-fold more active than the standard drug acarbose, which significantly attenuated postprandial blood glucose in mice. In addition, the compound 7u also induced the fluorescence quenching and conformational changes of enzyme, by forming α-glucosidase–7u complex in a mixed inhibition type. The thermodynamic constants recognised the interaction between 7u and α-glucosidase and was an enthalpy-driven spontaneous exothermic reaction. The synchronous fluorescence and CD spectra also indicate that the compound 7u changed the enzyme conformation. The findings identify the binding interactions between new ligands and α-glucosidase and reveal the compound 7u as a potent α-glucosidase inhibitor.

Keywords: α-Glucosidase, acetophenone derivatives, inhibiting mechanism, in vitro, in vivo

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is one of the major chronic diseases1. The incidence and prevalence of diabetes have risen sharply in recent years, and 642 million people might be suffering from diabetes until 20402,3. α-Glucosidase is a type of glycoside hydrolase, which favors in absorption of carbohydrates. By inhibiting its activity, the absorption of small intestine carbohydrates could be delayed, which bring on the reduction of postprandial blood glucose4,5. Moreover, the inhibition of α-glucosidase also has positive effects to treat some diseases such as virosis, cancer, and chronic heart failure etc6,7. Nowadays, the α-glucosidase inhibitors have been recognised as an efficient therapy in the treatment of type-II diabetes (T2D)8. They inhibit membrane bound α-glucosidase in the cells lining the small intestine, which in turn decreases the digestion of starch and additional dietary sugars, helping to avoid hyperglycemia and maintain normal blood sugar levels9. Therefore, it is significant to discover new classes of α-glucosidase inhibitors and to investigate the action mechanism of these inhibitors.

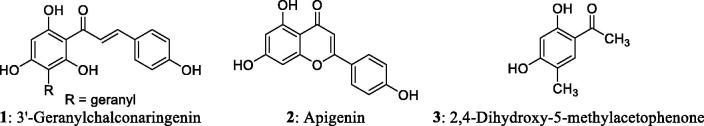

Numerous medical and nutritional researches have revealed that the natural phenols took a key position in prevention and control of various diseases like diabetes, cancer, and neurodegenerative10,11. Various natural products have been reported for their α-glucosidase inhibition activity. The study of Sun et al.12 and Zeng et al.13, shows that the natural phenols 3′-geranylchalconaringenin 1 and apigenin 2 (Figure 1) both exhibited superior inhibition activity against α-glucosidase than acarbose (a standard drug). The compound 2,4-dihydroxy-5-methylacetophenone 3 was isolated from the cultures of Polyporus picipes (Figure 1) by our group as a good fungicide14–19, which also showed considerable inhibitory activity against α-glucosidase in prescreen. Considering the structural characteristics of existing phenolic α-glucosidase inhibitors and the advantages of natural product resources, in this research work about 23 derivatives of 2,4-dihydroxy-5-methylacetophenone 3 were synthesised. The newly prepared analogs were also explored for their inhibitory activity and mechanism against α-glucosidase.

Figure 1.

The structures of 3′-geranylchalconaringenin 1, apigenin 2 and 2,4-dihydroxy-5-methylacetophenone 3.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. General

1H NMR and 13 C NMR spectra were carried out using a 500 MHz Avance spectrometer (Bruker, USA) or a Varian Mercury 400 MHz spectrometer. Chemical shifts were measured relative to the residual solvent peaks of CDCl3 with tetramethylsilane as the internal standard. High-resolution mass spectra were recorded on an AB SCIEX Triple TOF 5600+ spectrometer. The in vitro inhibitory activity and kinetic assay of α-glucosidase were measured by a microplate reader (Synergy HTX, BioTek Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). Fluorescence spectra were conducted on a spectrofluorometer (LS55, Perkin Elmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). All of the CD spectra were measured at 298 K with a circular spectrometer (Chirascan, Applied Photophysics Ltd., UK). Titration microcalorimetry measurement conducted on a Nano-ITC SV instrument (TA Instruments Ltd., UK). The surgeries were performed under anesthesia and all efforts were made to minimise animal suffering. The blood glucose levels were determined via a glucose detection kit (Robio Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The jejuna for everted sleeve assays were obtained from adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (SCXK (Shaan) 2017–003, 7 weeks old). The concentrations of glucose in the soaking solution and intestinal sleeve were detected using S-10 biosensor analyzer (Sieman Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China). All reaction progress was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on silica gel GF254 (Qingdao Haiyang Chemical Co., Ltd., Qingdao, China) with ultraviolet detection. Reagents were purchased from commercial sources (Bodi Chemical Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China; Aladdin Industrial Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), and used as received. α-Glucosidase (EC 3.2.1.20, Sigma-Aldrich Chemical, St. Louis, MO, USA); 4-nitrophenyl-α-D-glucopyranoside (pNPG) (99%, Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China).

2.2. Chemistry

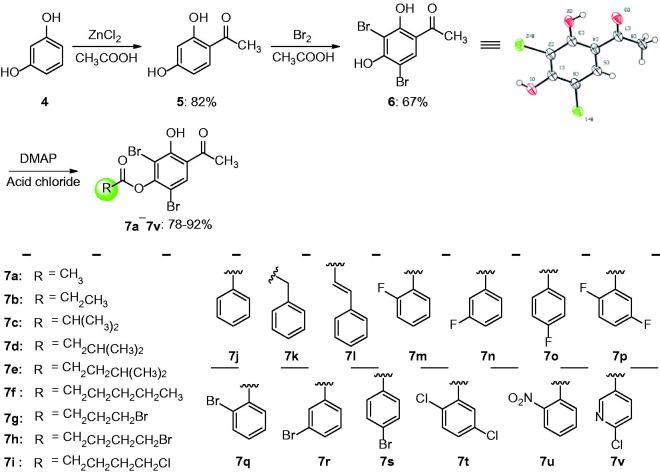

The synthesis of natural product 3 has been reported by our group (Scheme S1)15. Compounds 6 and 7a–7v were carried out as illustrated in Scheme 1. Details are described below.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of compounds 7a−7v.

2.2.1. Synthesis of 3,5-dibromo-2,4-dihydroxyacetophenone (6)

To a solution of 2,4-dihydroxyacetophenone 5 (1.52 g, 10 mmol) in acetic acid (80%, 20 ml), 3.2 g of bromine (1.04 ml, 20 mmol) dissolved in 10 ml acetic acid was added dropwise with continuous stirring20. The mixture was stirred for 15 min. Then the pale red crystals obtained, which were filtered off and recrystallised from benzene to give compound 6 as white crystals, yield (2.06 g, 67%), m.p. 174 − 175 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 13.31 (s, 1 H), 7.88 (s, 1 H), 2.60 (s, 3 H); 13 C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 202.0, 160.4, 155.6, 133.4, 115.3, 99.4, 98.9, 26.3. HR-ESI-MS m/z Calcd. for C8H6Br2O3 [M–H]– 306.8611, found 306.8610.

2.2.2. Synthesis of compounds 7a–7v

A solution of 6 (1 mmol), 4-dimethylaminopyridine (2 mmol) and acid chloride (1.2 mmol) in dry acetonitrile (15 ml) was stirred at room temperature. The reaction was monitored by TLC. On completion, the resulting mixture was directly evaporated. Then the residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography with petroleum ether and ethyl acetate (10:1, v/v) to produce 7a–7v in 78–92% yield.

2.3. Biological evaluation

2.3.1. α-Glucosidase inhibitory assay

The α-glucosidase inhibitory assay was performed according to a slightly modified method previously reported21,22. In brief, a series of reaction solutions, including a fixed amount of α-glucosidase (10 unit/mL 3.75 µL), different concentrations of inhibitors (the tested compounds or positive controls, 37.5 µL), and sodium phosphate buffer (PBS, 596.75 µL, 0.1 M, pH 6.8), were incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. To initiate the reaction, 112.5 µL of pNPG (6.0 mM, as a substrate) was added into the pre-incubated mixtures, and the final volume of reaction system was kept at 750 µL. The p-nitrophenol released from pNPG substrate was used as the target substance to quantify the enzymatic activity. The absorbance of p-nitrophenol was monitored at 405 nm after incubation at 37 °C for 30 min. All samples were analyzed in triplicate, acarbose, and genistein were used as positive controls. The negative control was prepared by adding PBS instead of α-glucosidase, the blank was prepared by adding solvent instead of tested compounds, and the inhibition rate was calculated as the following Equation (1).

| (1) |

Equation (1). Inhibition rate calculation formula.

2.3.2. Sucrose–loading test

The carbohydrate loading test was conducted according as Kato et al.23 and Han et al.24 reported, with slight modifications. Fifteen male Kunming mice (35–40 g) after an overnight fast were randomly divided into three groups (five mice per group). Sucrose (2.5 g/kg body weight), as well as the tested compound 7u (20 mg/kg body weight) and acarbose (20 mg/kg body weight) were dissolved in 0.5% sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC–Na) solution, then administered to mice via a gavage method, respectively. A blank control group was loaded with 0.5% CMC–Na solution only. The blood samples were collected from the mice’s tail vein at 0, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min, and the blood glucose levels were determined by a glucose detection kit.

2.3.3. Everted sleeve assays

The inhibitory activity of compound 7u against α-glucosidase was assayed on everted intestinal sleeves following the methods of Han et al.24 and Scow et al.25 with little modifications. After a 12-h fasting, the jejunum of 200–220 g Sprague-Dawley mice was obtained. Then the proximal jejunum was flushed with pre-cold isotonic saline (4 °C) and cut into 3 cm-long segments. Each segment was weighed separately, everted and both ends were secured by tying knots. Then the sleeves were incubated (90 min at 37 °C) in mammalian Ringer’s solution containing sucrose (1.5 mM) and an appropriate concentration of the inhibitor (0.17 mM). Following the incubation, the concentrations of glucose in the soaking solution and intestinal sleeves were tested with biosensor analyzer (S-10). The total glucose concentration was calculated as glucose per gram of gut weight (mmol/g).

2.3.4. Kinetic analysis

To further explore the inhibitory characteristic of this type of compounds, kinetic studies of the selected compound 7u were performed3,13,26. Different final concentrations (0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 µM) of the inhibitor 7u around the IC50 values were chosen. The concentration of α-glucosidase was kept at 1 µM, and the pNPG concentrations varied from 2.0 to 12.0 mM in the absence and presence of compound 7u. The type of inhibition was analyzed on the basis of the Michaelis–Menten constant (Km) and maximal rate (Vmax) of the enzyme. The parameters were determined via Lineweaver–Burk plots, which was obtained by plotting enzyme reaction velocity (ν) and substrate (pNPG), namely, 1/ν versus 1/[pNPG]. The secondary plot slope against [7u] was also determined. The protein concentration was determined according to the Bradford method27 using bovine serum albumin as the standard28.

2.3.5. Fluorescence spectra measurements

The steady state fluorescence emission spectra, were recorded between 300 and 500 nm at the excitation wavelength of 280 nm at three different temperatures (25, 31 and 37 °C), and both the excitation and emission slits were set at 2.5 nm. Compound 7u at different concentrations (from 0 to 6 µM) were added into the 3.0 ml solution containing a fixed amount of α-glucosidase (2μM). All of the mixtures were held for 5 min to equilibrate before measurements. The fluorescence spectra of buffer were subtracted as the background fluorescence29–32.

The synchronous fluorescence spectra of α-glucosidase in the absence and presence of compound 7u were scanned by setting the excitation and emission wavelength intervals (Δλ) at 15 and 60 nm, respectively. To eradicate the probability of re-absorption and inner filter effects in UV absorption, all of the fluorescence data were corrected for absorption of exciting light and emitted light, based on the Equation S13,13.

2.3.6. Titration micro-calorimetry measurement

Titration of the compound 7u into the α-glucosidase was performed at 25 °C. All the solutions were prepared in 0.1 M PBS (pH 6.8). The α-glucosidase solution (2.5μM) was placed in the 1.3 ml sample cell of the calorimeter, and the injection syringe was loaded with the solution of 7u (30μM, in 0.05% DMSO). The solution of compound 7u was titrated into the sample cell at 25 °C as a progression of 25 injections of 10μL. The time delay between each two injections was 300 s. To ensure comprehensive mixing, all the sample was stirred at a speed of 300 rpm during experiment. The control experiments included the titration of the compound 7u solution into 0.1 M PBS (pH 6.8)33–35.

2.3.7. Circular dichroism measurement

The CD measurements of α-glucosidase in the presence of compound 7u were conducted in far–UV region (190–250 nm), under nitrogen environment using a 1.0 mm path length cuvette. The concentration of α-glucosidase was maintained constant (2 µM) while the 7u concentration was varied as 0, 1, 2, and 4 µM. All observed CD spectra were recorded in 0.1 M PBS (pH 6.8) at 25 °C13,31.

2.4. Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SD. The statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA), using one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey post hoc test (for comparison among three or more groups). The statistical significance was considered at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Chemistry

The natural product 3 can be easily obtained by reduction and Friedel-Crafts reactions of industrial raw material 2,4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde15. The compound 5, similar to the natural product 3, can be obtained in good yield (82%) from resorcinol 4 with previously reported catalyst ZnCl2–CH3COOH (Scheme 1). In order to increase the metabolic stability36, the Br was used to replace the hydrogen atoms by conventional halogenation reaction and the moderate yield (67%) was acquired20. The structure of compound 6 was also verified by X-ray single crystal diffraction (CCDC 1869203). With this compound 6 in hand, the main focus was on modifying phenolic hydroxyl at OH-4′, which is more reactive than OH-2′ due to presence of intramolecular hydrogen bond. That’s why a series of ester derivatives 7a–7v (78–92% yields) was synthesised, with various chain alkanes and substituted phenyl groups, which in turn varied in chain length, electron-inducing ability and substitution position. All these compounds were thoroughly characterised (see Supporting Information for details, Figures S2–S24). This diversity of product may help to explore the interactions between small molecules and biotarget.

3.2. Biological evaluation

3.2.1. In vitro α-glucosidase inhibitory activity and SARs

As presented in Table 1, all the compounds were tested for their inhibition rate under 20 µM. Then the active compounds whose inhibition rates were over 70% were evaluated for their IC50 values. The IC50 values were found between 1.68 and 7.88 μM for 7d, 7f, 7i, 7n, 7o, 7r, 7s, 7u, and 7v, while that of acarbose and genistein was 54.74 and 22.64 μM, respectively. These results indicated that those compounds were more effective against α-glucosidase than the standard drug acarbose.

Table 1.

α-Glucosidase inhibition of high active compounds in vitro.

| Compd. | IC50 (µM) | Compd. | IC50 (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 16.22 ± 0.41 | 7l | 12.07 ± 0.22 |

| 6 | 17.38 ± 0.55 | 7n | 3.46 ± 0.26 |

| 7c | 19.35 ± 0.46 | 7o | 1.97 ± 0.28 |

| 7d | 6.08 ± 0.20 | 7r | 4.62 ± 0.24 |

| 7e | 10.89 ± 0.07 | 7s | 7.88 ± 0.17 |

| 7f | 6.73 ± 0.81 | 7u | 1.68 ± 0.05 |

| 7g | 12.43 ± 0.27 | 7v | 1.85 ± 0.27 |

| 7i | 3.27 ± 0.39 | Genistein | 22.64 ± 3.03 |

| 7j | 17.49 ± 0.53 | Acarbose | 54.74 ± 0.16 |

The SARs of these derivatives were summarised briefly as following: (1) longer straight-chain alkyl at ester substitution sites could increase the level of α-glucosidase inhibition, as IC50 of compounds 7a and 7f were >20 and 6.73 µM, respectively; (2) the introduction of branched alkyl chain are favorable, as inhibiting activity of compounds 7c (IC50 = 19.35 µM) was superior than 7a; (3) the haloalkyl chain might improve the inhibition, such as compound 7i (IC50 = 3.27 µM). However, compound 7 h was a special case which lost the activity; (4) the aromatic ring substituted groups were beneficial for improving the activity, except for the compounds 7k, 7 m, 7q, and 7t. Especially, the large steric and electron-withdrawing groups on the aromatic rings were essential for enhancing the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity (the IC50 of 7u was 1.68 µM). Compound 7u was found as the most high active against α-glucosidase among all newly synthesised compounds. We thus furtherly explored its mechanism on α-glucosidase inhibition by several methods.

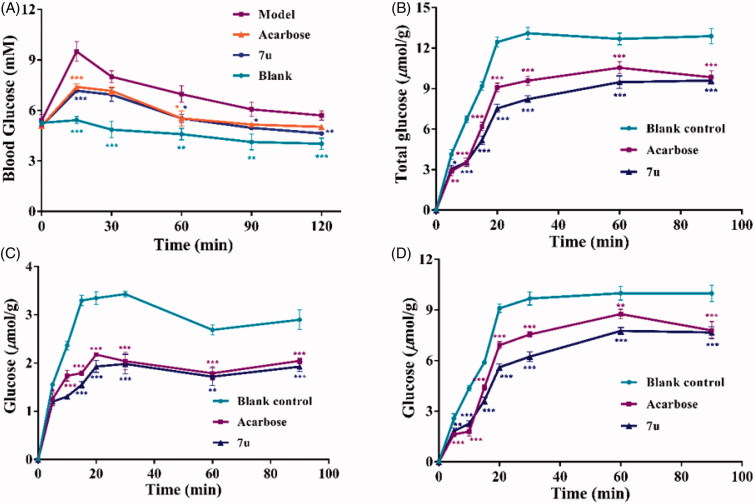

3.2.2. Sucrose-loading test

The sucrose loading assay was performed to confirm whether compound 7u kept reduction effects on postprandial blood glucose levels in vivo. The blood glucose levels were measured as scheduled time, by the glucose detection kit. As shown in Figure 2(A), the blood glucose level of fasted mice was rapidly increased from 5.40 to 9.50 mM after administration of sucrose (2.5 g/kg body weight) for 15 min. In comparison, the blood glucose level of blank group exhibited almost no variations through the test time course. Meanwhile, an obvious repressive effect on blood glucose concentrations at peaked 15 min was observed for treated group (compound 7u), which were similar to acarbose. Interestingly, both blood glucose concentrations of 7u treated group and acarbose treated group were at lower level than the model group, and exhibited no significant difference up to 90 min. It can be inferred that the hyperglycemic inhibition by 7u was probably associated with its inhibitory activity on the carbohydrate-digestive enzymes. For example, α-glucosidase, or the glucose transporters, including sodium-dependent glucose cotransporters (SGLTs) and the facilitative glucose transporters (GLUTs)24.

Figure 2.

(A) Effects of compound 7u and acarbose on postprandial blood glucose levels. (B) Inhibitory activity of compound 7u (0.17 mM) and acarbose (0.17 mM) on mice intestinal α-glucosidase. Total concentration of glucose (μmol/g); (C) and (D) Plots of the concentrations of glucose (μmol/g) in and out of the intestinal sleeves, respectively.

3.2.3. Everted sleeve assays

The α-glucosidase is one of the most important carbohydrate digestive enzymes which are found on the surface membrane of the intestine. In order to explore the inhibitory activity of compound 7u against intestine α-glucosidase, the inhibitory activity of α-glucosidase on everted intestinal sleeves was tested. As shown in Figure 2(B), both 7u (0.17 mM) and acarbose (0.17 mM) led to decreasing the concentration of total glucose from the first (5 min) to the last (90 min) time-point, and the concentrations of glucose were found much lower than that of the blank. Additionally, the inhibitory activity of compound 7u was better than that of acarbose. The glucose concentrations of compound 7u and acarbose-treated groups in the intestinal sleeves were lower than that of blank (Figure 2(C)), which indicated both 7u and acarbose could inhibit the activity of glucose transporters, such as SGLT1 and GLUT2, and help reducing the glucose absorption from the intestinal tract to the blood25. The compound 7u also decreased the glucose concentrations in the solution present outside the intestinal sleeves (Figure 2(D)), which suggested that 7u was more efficient to inhibit the transformation of sucrose to glucose. Accordingly, compound 7u was taken as a significant inhibitor of α-glucosidase. The inhibitory activity of α-glucosidase could effectively reduce postprandial blood glucose, which agreed with the result of sucrose-loading test. Hence, the major concentration was exploring the inhibitory mechanism of compound 7u against α-glucosidase.

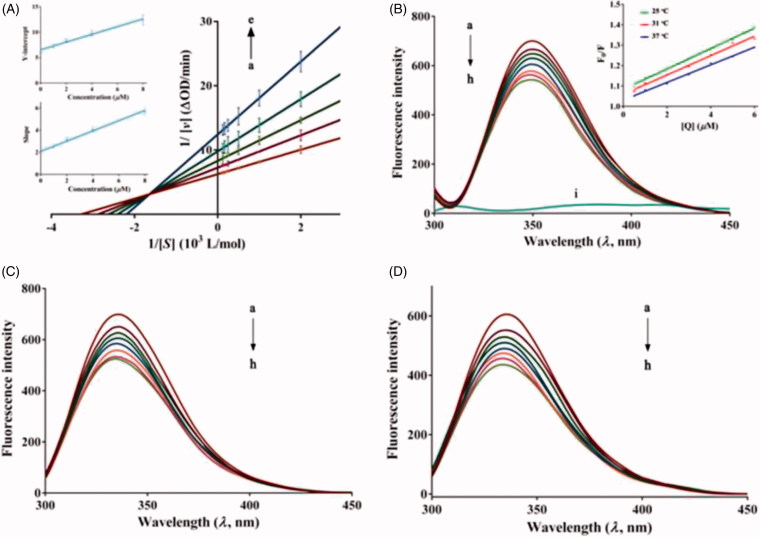

3.2.4. Kinetic analysis of inhibitory type

To explore the type of inhibition characterised by 7u against α-glucosidase, the kinetic assay was carried out by Lineweaver–Burk equation and Michaelis–Menten equation (Equations S2–S4). As shown in Lineweaver–Burk double-reciprocal plot (Figure 3(A)), the lines intersected in second quadrant, while, Vmax and Km changed with varying the concentration of compound 7u. These results indicated that 7u induced a mixed-type inhibition. The secondary plots (inset of Figure 3(A)) showed a good linear relationship, suggesting that the inhibitor (7u) bound mainly in a single kind of inhibition sites on α-glucosidase. The kinetic parameters (Table 2) were also obtained by the nonlinear regression of the Michaelis–Menten plots (Supplementary Figure S1) and the Ki value of this mixed-type inhibition was calculated as 2.28 μM.

Figure 3.

(A) Lineweaver–Burk plots. c(7u) = 0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 8 μM for curves a → e, respectively. The inset was the secondary plots of slope (the upper left) and Y-intercept (the lower left) versus [7u]. (B) Fluorescence spectra of α-glucosidase in the presence of 7 u at various concentrations (pH 6.8, T = 25 °C, λex = 280 nm, λem = 346 nm). c(α-glucosidase) = 2 µM, and c(7u) = 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 µM for curves a → h, respectively. Curve i shows the emission spectrum of 7 u at the concentration of 6 µM. The Stern–Volmer plots for the fluorescence quenching of α-glucosidase by 7 u at different temperatures were inserted. (C) T = 31 °C. (D) T = 37 °C.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters of α-glucosidase in the presence of 7u.

| Concentrations of 7u (µM) | Vmax (µM·min−1) | Km (µM) | Ki (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.60 ± 0.03 | 5.19 ± 0.67 | 2.28 ± 0.46 |

| 1 | 1.39 ± 0.02 | 6.18 ± 0.59 | |

| 2 | 1.24 ± 0.01 | 8.17 ± 0.37 | |

| 4 | 1.04 ± 0.01 | 9.08 ± 0.53 | |

| 8 | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 10.83 ± 0.96 |

3.2.5. Fluorescence quenching mechanism and binding characterisations

The endogenous fluorescence property of α-glucosidase is mainly derived from aromatic amino acid residues, such as tryptophan and tyrosine3. So the fluorescence quenching experiments could be used to characterise the binding constant (Ka), binding site (n) and mechanism of binding between 7u and the enzyme. As shown in Figure 3(B)–(D), α-glucosidase possessed a strong fluorescence-emission peak at 350 nm, which quenched regularly with the addition of increasing the sample (7u) concentrations. The data suggested the change of α-glucosidase structure, at the meantime, reflecting the formation of α-glucosidase–7u complex.

To shed light on the interaction mechanism, the Stern–Volmer equation (Equations S5) was used to analyze the fluorescence data. The Stern–Volmer plots (the inset in Figure 3(B)) suggested that the quenching course was a single mode. Generally, there are two types of quenching i.e. dynamic quenching and static quenching. Usually, static quenching is characterised by decreasing quenching constant with increasing temperature29. As listed in Table 3, the values of KSV have a negative correlation with temperature, specifying a static quenching mechanism. Furthermore, the values of Kq (1012 L·mol−1·s−1) far exceeded than maximum diffusion collision quenching constant (2.0 × 1010 L·mol−1·s−1), which also suggested a static quenching process. The intrinsic binding constant Ka and the number of binding sites n values of α-glucosidase with 7u could be calculated by the double logarithm equation (Equations S6). The Table 3 presented the values of Ka which were in the order of 105 L·mol−1, indicating a moderate to good binding affinity of compound 7u for the α-glucosidase. In addition, the values of Ka were also inversely correlated with temperature that evoked the stability of the compound–enzyme complex decreased at a higher temperature. Furthermore, the value of n was approximate to 1, which indicated the presence of a single binding site for understudy compound (7u) on α-glucosidase.

Table 3.

Quenching constants (Ksv), binding constants (Ka) and number of binding sites (n) for the 7u − α-glucosidase system at different temperatures.

| T (oC) | KSV (× 104 L·mol−1) | Ra | Ka (× 105 L·mol−1) | n | Rb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 5.00 ± 0.04 | 0.9937 | 4.35 ± 0.05 | 1.23 | 0.9986 |

| 31 | 4.74 ± 0.03 | 0.9905 | 2.50 ± 0.04 | 1.19 | 0.9990 |

| 37 | 4.31 ± 0.02 | 0.9964 | 1.33 ± 0.03 | 1.15 | 0.9993 |

aThe correlation coefficient for the KSV value.

bThe correlation coefficient for the Ka value.

To further characterise the intermolecular forces between α-glucosidase and 7u, the thermodynamic parameters were also calculated by using van’t Hoff equation (Equation S7 and S8), which determined the main forces contributing to the ligand–protein stability.

The values of ΔH° and ΔS° were obtained from the linearly fitted plot of logKa against 1/T. The values of Ka rose with the temperature enhancement, which directed that the binding ability of 7u to α-glucosidase became stronger with increasing temperature, while the binding reaction was exothermic. The negative values of ΔG° showed that the binding process was thermodynamically favorable and occurred spontaneously. As the calculated parameters listed in Table 4, the negative values of ΔH° (–75.82 kJ·mol−1) and ΔS° (–146.32 J·mol−1·K−1) indicated the action of van der Waals force and hydrogen bonds offered the dominant contribution not only in formation but also in stabilisation of the α-glucosidase–7u complex. The reaction also characterised an enthalpy-driven process due to |ΔH°| > |TΔS°|.

Table 4.

Thermodynamic parameters for the 7u − α-glucosidase system.

| T (oC) | ΔGo (kJ·mol−1) | ΔHo (kJ·mol−1) | ΔSo (J·mol−1·K−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | −32.21 ± 0.06 | −75.82 ± 0.11 | −146.32 ± 0.02 |

| 31 | −31.33 ± 0.03 | ||

| 37 | −30.46 ± 0.02 |

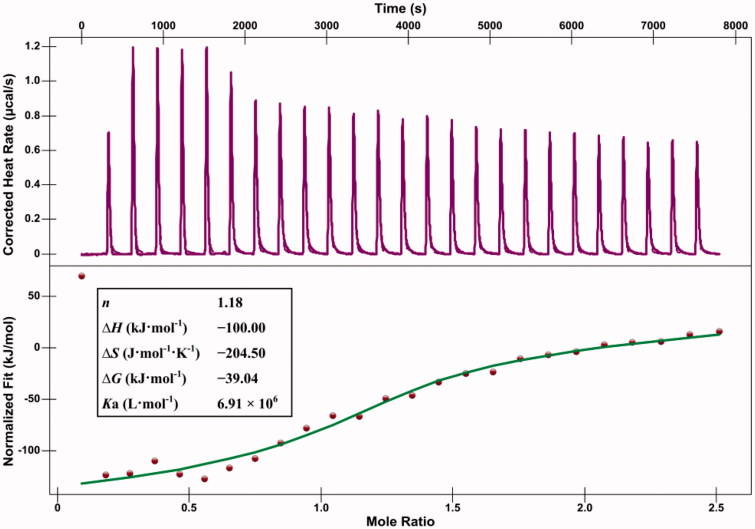

3.2.6. Isothermal titration calorimetry binding assays

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) was carried out to study the interactions between compound 7u and α-glucosidase, which could give direct measurement of the binding constant, the stoichiometry, the heat of reaction, as well as the indirect access to other thermodynamic parameters such as entropic binding contribution and Gibbs free energy. As shown in Figure 4, the green curve corresponded to a binding model with a 1:1 stoichiometry, which also fitted with the change of enthalpy (ΔH, −100.00 kJ·mol−1), entropy (ΔS, –204.50 J·mol−1·K−1) and free energy (ΔG, –39.04 kJ·mol−1). These data indicated that the binding was enthalpy-driven and spontaneous reaction which conformed to the fluorescence result. The value of binding constant Ka was 6.91 × 106 L·mol−1, demonstrating a good binding affinity of compound 7u for α-glucosidase. Fluorescence technology and ITC are common methods for studying the interactions between small molecular ligands and protein35,37,38. In this work, the thermodynamic parameters obtained by these two methods showed the same trend. However, there are some difference in their values, which could be attributed to factors such as the tested solvent environment, the macromolecular state, and the electrostatic repulsions between the molecules that bear the same charge35. Similar situations have also been reported in the literatures35,37. The accurate thermodynamic parameters need to be further studied in combination with other techniques, such as surface plasmon resonance (SPR)38,39 and thermal shift assays (TSA)40,41.

Figure 4.

Calorimetric titration of the α-glucosidase with compound 7 u at 25 °C. Heat flow as a function of time (purple). The green curve corresponds to the theoretical independent model. The thermodynamic constants are presented in the pane.

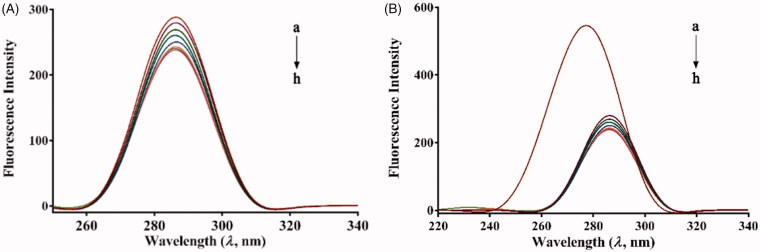

3.2.7. Synchronous fluorescence

The microenvironment changes of fluorophores in α-glucosidase were monitored by synchronous fluorescence spectroscopy, which was done by measuring the possible shift of spectra in maximum emission wavelength before and after binding with ligand. By setting the Δλ (Δλ = λem – λex) at 15 or 60 nm, the information about the microenvironment changes of Tyr and Trp residues were obtained, respectively29. As shown in Figure 5, the synchronous fluorescence intensity of both Tyr and Trp residues decreased with the concentration of 7u increased. No evident shift was observed at the maximum emission wavelength of Tyr residues (Figure 5(A)). However, Trp residues had a noticeable red shift (from 277.5 to 286.5 nm) as shown in Figure 5(B). The result indicated that 7u did not alter the polarity around Tyr residues significantly, while the polarity around the Trp residues enhanced and the hydrophobicity decreased. In addition, the gradually declined fluorescence intensity with increased concentration of 7u further supported the occurrence of fluorescence quenching.

Figure 5.

Synchronous fluorescence spectra of α-glucosidase in the presence of increasing concentrations of 7 u (A) Δλ = 15 nm, (B) Δλ = 60 nm (pH 6.8, T = 25 °C). c(α-glucosidase) = 2 µM. c(7u) = 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 µM for curves a → h, respectively.

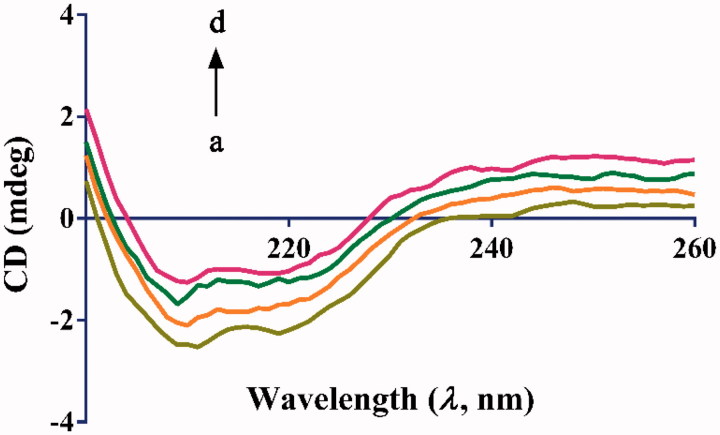

3.2.8. Circular dichroism spectroscopy

The CD spectroscopy has considered as a reliable and sensitive method for monitoring the structural changes of bio-macromolecules in interaction with small molecules. As shown in Figure 6, the CD spectra of α-glucosidase exhibited a pair of negative bands at 209 and 220 nm, which were the characteristic of the α-helical structure of protein, originated from the n→π* and π→π* electron transfer for the peptides bonds of the α-helix3,42. On adding various concentrations of ligand (7u), both intensity of the negative bands decreased without any significant changes in the peak position and shape. The results revealed that binding of 7u to α-glucosidase encouraged the structural transformation of polypeptides, resulting in the inhibition of α-glucosidase activity.

Figure 6.

CD spectra of α-glucosidase in the presence of 7 u. c(α-glucosidase) = 2 µM. The molar ratios of 7 u to α-glucosidase were 0:1, 1:1, 2:1 and 4:1 for curves a → d, respectively.

4. Conclusions

This work demonstrated the α-glucosidase inhibitory potential of natural 2,4-dihydroxy-5-methylacetophenone scaffold and its derivatives. The in vitro study revealed that compounds 7d, 7f, 7i, 7n, 7o, 7r, 7s, 7u, and 7v were efficient α-glucosidase inhibitors with IC50 values of 1.68–7.88 μM, which were much stronger than that of acarbose and genistein. The most promising derivative 7u effectively reduced the level of postprandial blood glucose in vivo mainly through inhibition of the activity of α-glucosidase. Furthermore, this research displayed that compound 7u inhibited the activity of α-glucosidase in a mixed-type manner, with its Ki value of 2.28 µM. As an enthalpy-driven spontaneous process, the compound 7u bound to α-glucosidase to form a complex with one affinity binding site. Overall, this research could enrich the types of candidate α-glucosidase inhibitors and provide more options for efficient chemotherapies in the treatment of Type-II diabetes.

Funding Statement

This work was financially supported by the Natural Science Basic Research Plan in Shaanxi Province of China (2014JZ2-001), the Program of Unified Planning Innovation Engineering of Science & Technology in Shaanxi Province (No.2015KTCQ02-14).

Ethical statement

The animal experimental procedures performed in this study were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Xi’an Jiaotong University, and the protocols were in accordance with the Guidelines for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals: 8th Edition, ISBN-10: 0–309-15396–4. All surgeries were performed under anesthesia and all efforts were made to minimise animal suffering.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Jiang-Kun Dai for fluorescence and ITC data analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. 2016. Global report on diabetes. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. Available at http://www.who.int/diabetes/global-report/en/.

- 2.Dlamini Z, Mokoena F, Hull R. Abnormalities in alternative splicing in diabetes: therapeutic targets. J Mol Endocrinol 2017;59:93–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ding H, Wu X, Pan J, et al. . New insights into the inhibition mechanism of betulinic acid on α-glucosidase. J Agric Food Chem 2018;66:7065–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lordan S, Smyth TJ, Soler-Vila A, et al. . The α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory effects of Irish seaweed extracts. Food Chem 2013;141:2170–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van De Laar FA, Lucassen PL, Akkermans RP, et al. . α-Glucosidase inhibitors for patients with type 2 diabetes: Results from a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2005;28:154–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Courageot MP, Frenkiel MP, Dos Santos CD, et al. . α-Glucosidase inhibitors reduce dengue virus production by affecting the initial steps of virion morphogenesis in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Virol 2000;74:564–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pili R, Chang J, Partis R, et al. . The α-glucosidase I inhibitor castanospermine alters endothelial cell glycosylation, prevents angiogenesis, and inhibits tumor growth. Cancer Res 1995;55:2920–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henrissat B, Bairoch AM. New families in the classification of glycosyl hydrolases based on amino acid sequence similarities. Biochem J 1993;293:781–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krentz AJ, Bailey CJ. Oral antidiabetic agents: current role in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Drugs 2005;65:385–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao JB, Hogger P. Dietary polyphenols and type 2 diabetes: current insights and future perspectives. Curr Med Chem 2014;22:23–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma SJ, Yu J, Yan DW, et al. . Meroterpene-like compounds derived from β-caryophyllene as potent α-glucosidase inhibitors. Org Biomol Chem 2018;16:9454–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun H, Wang D, Song X, et al. . Natural prenylchalconaringenins and prenylnaringenins as antidiabetic agents: α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibition and in vivo antihyperglycemic and antihyperlipidemic effects. J Agric Food Chem 2017;65:1574–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeng L, Zhang GW, Lin SY, et al. . Inhibitory mechanism of apigenin on α-glucosidase and synergy analysis of flavonoids. J Agric Food Chem 2016;64:6939–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiao J, Zhang Q, Gao YQ, et al. . Secondary metabolites from the endophytic Botryosphaeria dothidea of Melia azedarach and their antifungal, antibacterial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities. J Agric Food Chem 2014;62:3584–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dan WJ, Tuong TML, Wang DC, et al. . Natural products as sources of new fungicides (V): Design and synthesis of acetophenone derivatives against phytopathogenic fungi in vitro and in vivo. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2018;28:2861–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li D, Tuong TML, Dan WJ, et al. . Natural products as sources of new fungicides (IV): Synthesis and biological evaluation of isobutyrophenone analogs as potential inhibitors of class-II fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase. Bioorg Med Chem 2018;26:386–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi W, Dan WJ, Tang JJ, et al. . Natural products as sources of new fungicides (III): Antifungal activity of 2,4-dihydroxy-5-methylacetophenone derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2016;26:2156–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nandinsuren T, Shi W, Zhang AL, et al. . Natural products as sources of new fungicides (II): Antiphytopathogenic activity of 2,4-dihydroxyphenyl ethanone derivatives. Nat. Prod Res 2016;30:1166–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma YT, Fan HF, Gao YQ, et al. . Natural products as sources of new fungicides (I): Synthesis and antifungal activity of acetophenone derivatives against phytopathogenic fungi. Chem Biol Drug Des 2013;81:545–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, Dong H, Zhao F, et al. . The synthesis and synergistic antifungal effects of chalcones against drug resistant Candida albicans. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2016;26:3098–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei J, Zhang XY, Deng S, et al. . α-Glucosidase inhibitors and phytotoxins from Streptomycesxanthophaeus Nat Prod Res 2017;31:2062–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu Y, Wang B, Yang J, et al. . Synthesis and biological evaluation of 3-arylcoumarin derivatives as potential antidiabetic agents. J Enzym Inhib Med Chem 2019;34:15–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kato A, Minoshima Y, Yamamoto J, et al. . Protective effects of dietary chamomile tea on diabetic complications. J Agric Food Chem 2008;56:8206–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han L, Zhang L, Ma W, et al. . Proanthocyanidin B2 attenuates postprandial blood glucose and its inhibitory effect on alpha-glucosidase: analysis by kinetics, fluorescence spectroscopy, atomic force microscopy and molecular docking. Food Funct 2018;9:4673–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scow JS, Iqbal CW, Jones TW, et al. . Absence of evidence of translocation of GLUT2 to the apical membrane of enterocytes in everted intestinal sleeves. J Surg Res 2011;167:56–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song YH, Uddin Z, Jin YM, et al. . Inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP1B) and α-glucosidase by geranylated flavonoids from Paulownia tomentosa. J Enzym Inhib Med Chem 2017;32:1195–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantization of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of proteindye binding. Anal Biochem 1976;72:248–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Honma A, Koyama T, Yazawa K. Anti-hyperglycaemic effects of the Japanese red maple Acer pycnanthum and its constituents the ginnalins B and C. J. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2011;26:176–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeng L, Ding HF, Hu X, et al. . Galangin inhibits α-glucosidase activity and formation of non-enzymatic glycation products. Food Chem 2019;271:70–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shahabadi N, Hadidi S, kalar ZM. Biophysical studies on the interaction of platinum(II) complex containing antiviral drug ribavirin with human serum albumin. J Photoch Photobio B 2016;160:376–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu H, Zeng W, Chen L, et al. . Integrated multi-spectroscopic and molecular docking techniques to probe the interaction mechanism between maltase and 1-deoxynojirimycin, an α-glucosidase inhibitor. Int J Biol Macromol 2018;114:1194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yousefi R, Alavian-Mehr M-M, Mokhtari F, et al. . Pyrimidine-fused heterocycle derivatives as a novel class of inhibitors for α-glucosidase. J Enzym Inhib Med Chem 2013;28:1228–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dai JK, Dan WJ, Li N, et al. . Synthesis and antibacterial activity of C2 or C5 modified and D ring rejiggered canthin-6-one analogues. Food Chem 2018;253:211–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma H, Wang L, Niesen DB, et al. . Structure activity related, mechanistic, and modeling studies of gallotannins containing a glucitol-core and α-glucosidase. RSC Adv 2015;5:107904–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu C, Cheng F, Yang X. Inactivation of soybean trypsin inhibitor by epigallocatechin gallate: Stopped-flow/fluorescence, thermodynamics, and docking studies. J Agric Food Chem 2017;65:921–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carosati E, Cosimelli B, Ioan P, et al. . Understanding oxadiazolothiazinone biological properties: Negative inotropic activity versus cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism. J Med Chem 2016;59:3340–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Srivastava P, Singh K, Verma M, et al. . Photoactive platinum(II) complexes of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug naproxen: Interaction with biological targets, antioxidant activity and cytotoxicity. Eur J Med Chem 2018;144:243–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jerabekwillemsen M, Wienken CJ, Braun D, et al. . Molecular interaction studies using microscale thermophoresis. Assay Drug Dev Techn 2011;9:342–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y, Edalji R, Panchal SC, et al. . Are we there yet? Applying thermodynamic and kinetic profiling on embryonic ectoderm development (EED) hit-to-lead program. J Med Chem 2017;60:8321–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garbett NC, Chaires JB. Thermodynamic studies for drug design and screening. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2012;7:299–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brito CC, Silva HV, Brondani DJ, et al. . Synthesis and biological evaluation of thiazole derivatives as LbSOD inhibitors. J Enzym Inhib Med Chem 2019;34:333–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshimizu M, Tajima Y, Matsuzawa F, et al. . Binding parameters and thermodynamics of the interaction of imino sugars with a recombinant human acid α-glucosidase (alglucosidase alfa): insight into the complex formation mechanism. Clin Chim Acta 2008;391:68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]