Abstract

Objective: To examine (i) the associations between physical activity dimensions, cardiorespiratory fitness and body composition and, (ii) the associations between physical activity dimensions, cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition and biomarkers of cardiometabolic health in persons with spinal cord injury (SCI).

Methods: A cross-sectional prospective cohort study with 7-day follow-up was conducted. Body composition, cardiorespiratory fitness and biomarkers of cardiometabolic health were measured in thirty-three participants with SCI (> 1 year post injury). Physical activity dimensions were objectively assessed over 7-days.

Results: Activity energy expenditure (r =.43), physical activity level (r =.39), and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) (r =.48) were significantly (P < 0.001) associated with absolute (L/min) peak oxygen uptake (⩒O2 peak). ⩒O2 peak was significantly higher in persons performing ≥150 MVPA minutes/week compared to <40 minutes/week (P = 0.003). Individual physical activity dimensions were not significantly associated with biomarkers of cardiometabolic health. However, body composition characteristics (BMI, waist and hip circumference) showed significant (P < 0.04), moderate (r >.30) associations with parameters of metabolic regulation, lipid profiles and inflammatory biomarkers. Relative ⩒O2 peak (ml/kg/min) was moderately associated with only insulin sensitivity (r = 0.37, P = 0.03).

Conclusions: Physical activity dimensions are associated with cardiorespiratory fitness; however, stronger and more consistent associations suggest that poor cardiometabolic health is associated with higher body fat content. Given these findings, the regulation of energy balance should be an important consideration for researchers and clinicians looking to improve cardiometabolic health in persons with SCI.

Key words: Cardiorespiratory fitness, Cardiovascular disease, Metabolic disease, Paraplegia, Inflammation

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is characterised by increased mortality1 and a greater risk of developing chronic diseases (i.e. cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes; T2D) compared to non-disabled individuals.2,3 In the general population, larger volumes of physical activity are associated with reduced all-cause mortality4 and a substantially lower incidence of T2D.5 Therefore, such relationships between physical activity and health are of considerable interest to policy makers and clinicians, especially in populations at increased risk of developing chronic disease. The Canadian physical activity guidelines for individuals with SCI (PAG-SCI)6 and recently published American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine (ACRM) recommendations7 both promote at least 40 minutes/week of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA). However, Totosy de Zepetnek et al.,8 has since demonstrated that adherence to the PAG-SCI for sixteen weeks was insufficient to promote clinically meaningful changes in cardiometabolic health biomarkers.

The current exercise and sports science Australia (ESSA) position statement on exercise and spinal cord injury9 is more in keeping with volumes of MVPA (> 150 minutes/week) promoted by international health authorities [World Health Organisation (WHO)]. Consequently, there remains uncertainty about the most suitable volume of MVPA for this population, partly because physical activity is a complex construct that is difficult to accurately measure. Recent technological advancements (i.e. multi-sensor physical activity monitors) and the development of population or individual-specific prediction algorithms now facilitate more accurate measurement of free-living physical activity behaviours in persons who use wheelchairs.10

There are numerous important dimensions of physical activity, besides the amount of time engaged in activities of a specific intensity, which could be biologically relevant and important for cardiometaoblic health.11 With respect to weight loss or maintenance, activity energy expenditure (AEE) is a key consideration.12 Consequently, certain international health authorities (i.e. Institute of Medicine) base their physical activity recommendations around normalised AEE [Physical activity level (PAL); Total energy expenditure/Resting metabolic rate]. Nevertheless, other physical activity dimensions such as sedentary time and light-intensity activity have been shown to provide considerable (and arguably independent) health-related benefits in the general population.13–15 Despite recent interest in sedentary behaviours in persons with SCI,16 such physical activity dimensions remain to be analysed in the context of cardiometabolic health biomarkers in this population.

Poor cardiorespiratory fitness has been widely reported in individuals with SCI.17,18 This is concerning as there is a wealth of evidence identifying cardiorespiratory fitness as an important determinant of all-cause morbidity and mortality in the able-bodied population.19,20 Moreover, it has been suggested that only 1 in 4 young people with paraplegia were able to achieve peak functional capacity necessary to maintain independent living.21 Of note, the only relevant environmental factor known to influence ⩒O2 peak is physical activity.22 Besides the adoption of a sedentary lifestyle and poor cardiorespiratory fitness, deleterious body composition changes also occur following SCI (reduced fat free mass and increased fat mass).23,24 The increase in central obesity, particularly the accumulation of visceral adipose tissue, has been linked to impaired carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in persons with SCI.25 Consequently, this study aims to examine: (i) the associations between physical activity dimensions, cardiorespiratory fitness and body composition and, (ii) the associations between physical activity dimensions, cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition and biomarkers of cardiometabolic health in persons with spinal cord injury (SCI).

Methods

Sample and experimental procedures

This study used pooled baseline data from two trials conducted at the University of Bath between December 2012 and April 2016.26,27 Ethical approval for these trials was granted by the University of Bath’s Research Ethics Approval Committee for Health (REACH) and the South West National Research Ethics Service Committee (REC reference number: 14/SW/0106). Participants were recruited from the local community, were not under medical care and were not taking T2D medication. All participants provided written informed consent. Thirty-three men (n = 27) and women (n = 6) with chronic (>1 year) SCI were included in the analysis. All data collection methods and subsequent analyses were identical between studies.

Participants visited the laboratory following an overnight fast (> 10 hours). Visits were scheduled within the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle for eumenorrheic female participants (n = 3). Out of the remaining female participants; two were postmenopausal and one amenorrheic. Anthropometric characteristics: height, waist and hip circumference were measured in duplicate to the nearest cm, with participants in a supine position, using a non-elastic tape measure (Lufkin, Sparks, USA). Body mass was measured using platform wheelchair scales (Detecto® BRW1000, Webb City, USA). A 20-mL venous blood sample was drawn from an antecubital vein, with serum and plasma stored at −80°C. Key systemic metabolites and hormones [serum triacylglycerol (TG), total and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, c-reactive protein (CRP) and plasma glucose] were measured in a batch analysis with commercially available spectrophotometric assays (Randox Laboratories, Co. Antrim, UK) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) [serum interleukin-6 (IL-6) (Quantikine HS, R & D Systems Inc, Abingdon, UK) and insulin (Mercodia AB, Uppsala, Sweden)].

Following a submaximal warm-up, participants performed an incremental exercise protocol on an electrically braked arm-crank ergometer (Lode Angio, Groningen, Netherlands). A cadence of 75 rpm was encouraged throughout the test and the starting intensity was selected based on the participants training history. Resistance was increased by 14W every three minutes until the point of volitional exhaustion (approximately 9–12 min).27 ⩒O2 peak was measured throughout using a computerised metabolic system (TrueOne® 2400, ParvoMedics, Salt Lake City, USA), with corresponding heart rate measurements (Polar T31 heart rate monitor, Polar Electro Inc., Lake Success USA) taken throughout exercise. Breath-by-breath ⩒O2 values were averaged over the final minute of each exercise stage, with the highest value representative of ⩒O2 peak. A number of criteria (with at least two of these being achieved) were applied to determine whether this endpoint reflected a valid ⩒O2 peak value. These were: (i) a peak RER value ≥ 1.1, (ii) a peak heart rate ≥ 95% the age-predicted maximum (200 beats/minute minus chronological age) and, (iii) an increase in ⩒O2 ≤ 2 ml/kg/min in response to an increased workload.28

Over the following 7 days participants wore a chest-mounted multi-sensor physical activity monitor (ActiheartTM, Cambridge Neurotechnology Ltd, Papworth, UK) to estimate habitual physical activity dimensions. These were activity energy expenditure (AEE; kcal/day), physical activity level (PAL; Total energy expenditure/Resting metabolic rate), and based on metabolic equivalents (METs) time spent performing (minutes/day); sedentary activities (< 1.5 METs), light-intensity activity (1.5–2.9 METs) and moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity (MVPA; ≥ 3 METs). The physical activity monitor was individually calibrated as described previously.27 This monitor and approach was previously validated for use in wheelchair users.26 Considering wear time impacts the reliability of determining sedentary behaviour,29 participants were required to wear the device for > 80% of each 24-hour period to constitute a valid measurement day. Participants were excluded from the analysis if they had < 4 valid measurement days. This is the number of days necessary to reliably measure PAL in middle aged adults with a multi-sensor physical activity monitor.30

Statistical analysis

The Homeostasis Model Assessment (HOMA) calculator, incorporating the updated HOMA-2 model,31 was used to derive fasting estimates of pancreatic β-cell function (-β), insulin resistance (-IR) and sensitivity (-S). LDL-C was calculated using the Friedewald equation [LDL-C = total cholesterol – HDL-C – (triacylglycerol/2.2)].32 All data were analysed for normality of distribution. The distributions of AEE, PAL, MVPA, hip circumference, fasting glucose and insulin, HOMA2-IR, CRP and IL-6 were positively skewed. Therefore, these values were log-transformed to allow the use of parametric statistics. Waist circumference was negatively skewed and was therefore reflected prior to log-transformation. Age, level of spinal cord lesion, time since injury (all continuous variables), neurological completeness of injury and sex (both categorical variables) were assessed as covariates for all dependent variables. Pearson correlation coefficients and independent t-tests were conducted for continuous and categorical covariates, respectively. Part correlations were calculated between dimensions of physical activity, cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition characteristics and biomarkers of cardiometabolic health, with adjustments for significant (P ≤ 0.05) covariates where indicated, using multiple linear regressions. The following descriptors were used to help interpret the magnitude of each correlation: small (r > 0.1), moderate (r > 0.3), large (r > 0.5) and, very large (r > 0.7). Where significant part correlations are observed for MVPA, participants were dichotomised into three groups LOW, less than 40 minutes/week (n = 9); MOD, 40 - 149 minutes/week (n = 11); or HIGH, ≥ 150 minutes/week (n = 11). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to determine differences between groups, with a Bonferroni correction for multiple Post Hoc comparisons. ANOVAs were performed on raw data, irrespective of any minor deviations from a normal distribution.33 Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (SPSS Statistics version 22; IBM Corp, Armonk, USA) with statistical significance accepted at a priori of α ≤ 0.05.

Results

Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. One participant had untreated T2D (fasting plasma glucose = 8.62 mmol/L). Dyslipidaemia was common, with 48% having total cholesterol values ≥ 5 mmol/L and 61% having elevated LDL-C (≥3 mmol/L) and depressed HDL-C (≤ 1.03 mmol/L for males and ≤ 1.29 mmol/L for females). Forty-five and forty-eight percent of participants had increased abdominal obesity (waist circumference > 94 cm) and high-risk of developing future cardiovascular events (CRP; > 3 mg/L), respectively. Only 35% of participants achieved the time/intensity physical activity guidelines from the WHO (≥ 150 minutes/week MVPA).

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

| Demographics | |

| Age (y) | 44 ± 9 |

| Sex (male/female) | 27/6 |

| Injury characteristics | |

| AIS A - B | 29 |

| AIS C - D | 4 |

| Lesion level | T1 – L4 |

| Time since injury (y) | 15 ± 10 |

| Body composition | |

| Body mass (kg) | 76.1 ± 12.5 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.3 ± 3.6 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 92.6 (12.5) |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 94.7 (9.6) |

| Physical activity1 | |

| AEE (kcal/day) | 358 (279) |

| PAL | 1.38 (0.18) |

| MVPA (min/day) | 17 (27) |

| Cardiorespiratory fitness2 | |

| ⩒O2 peak (L/min) | 1.51 ± 0.50 |

| ⩒O2 peak (ml/kg/min) | 19.8 ± 6.4 |

| Metabolic Regulation | |

| Fasting serum insulin (pmol/L) | 42.3 (34.5) |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L) | 5.33 (0.73) |

| HOMA2-IR | 0.74 (0.68) |

| HOMA2-β (%) | 75.0 ± 28.2 |

| HOMA2-S | 140.9 ± 67.7 |

| Cardiovascular health | |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.03 ± 0.97 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.07 ± 0.23 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.42 ± 0.81 |

| Triacylglycerol (mmol/L) | 1.21 ± 0.46 |

| Inflammatory markers | |

| CRP (mg/L)3 | 2.63 (4.72) |

| IL-6 (pg/ml)4 | 0.76 (0.75) |

Note: Data are mean ± SD for parametric variables. Non-parametric variables (waist and hip circumference, dimensions of physical activity, fasting serum insulin and plasma glucose, HOMA2-IR and, inflammatory markers) are median (interquartile range). Numbers of participants in each categorical variable are also presented (sex, neurological completeness of injury) along with the range of SCI lesion levels.

1missing data; n = 31 due to ActiheartTM monitor failure. ActiheartTM monitors were worn continually for 7 ± 1 days, with 96 ± 4% (mean ± SD) daily wear time.

2missing data; n = 30 due to participants not achieving valid ⩒O2 peak criteria.

3missing data; n = 29 due to small quantity of blood.

4missing data; n = 31 due to small quantity of blood.

Abbreviations: AEE, activity energy expenditure; AIS, American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale; BMI, body mass index; CRP, c-reactive protein; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HOMA, homeostasis model assessment; IR, insulin resistance; β, pancreatic β-cell function; S, sensitivity; IL-6, interleukin-6; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MVPA, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; PAL, physical activity level; ⩒O2 peak, peak oxygen uptake.

Covariates

A lower SCI lesion was associated with; a higher BMI (r = 0.38, P = 0.03), ⩒O2 peak [absolute and relative, r = 0.44 (P = 0.01) and 0.40 (P = 0.027), respectively] and poorer metabolic regulation [fasting insulin, r = 0.43 (P = 0.01); HOMA2-IR, r =0.45 (P = 0.009), and insulin sensitivity, r = −0.50 (P = 0.003)]. Longer time since injury was associated with higher fasting glucose concentrations (r = 0.36, P = 0.038). Older age was associated with lower ⩒O2 peak [absolute and relative, r = −0.44 (P = 0.016) and −0.59 (P = 0.001), respectively)]. ⩒O2 peak was also significantly higher in males (P = 0.007) and participants with incomplete SCI (P < 0.029). Females had significantly higher HDL-C concentrations (P = 0.008).

Associations between dimensions of physical activity, body composition characteristics and cardiorespiratory fitness

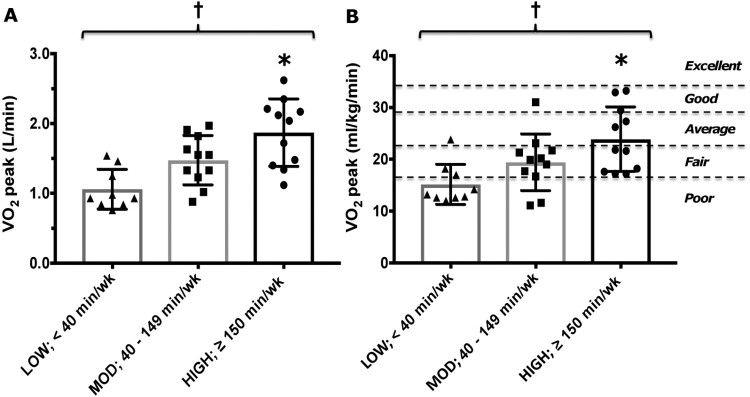

Part correlation coefficients between dimensions of physical activity (independent variables), body composition characteristics and cardiorespiratory fitness (dependent variables) are displayed in Table 2. There were no significant associations between physical activity dimensions and body composition characteristics. Greater PAL and MVPA revealed a moderate (r > 0.30) association with cardiorespiratory fitness (both absolute and relative ⩒O2 peak). There were also small but significant associations between AEE, sedentary time and ⩒O2 peak (ml/kg/min). When dichotomised into three groups (LOW, MOD, HIGH) there was a significant effect of MVPA volume on both absolute (Fig. 1A) and relative (Fig. 1B) ⩒O2 peak (P = < 0.005). Post Hoc analyses revealed that ⩒O2 peak was significantly higher in the HIGH compared to the LOW group (P < 0.003).

Table 2: Part correlation coefficients, with adjustments for covariates where indicated, between independent variables (dimensions of physical activity) and dependent variables (body composition characteristics and cardiorespiratory fitness).

| Dimensions of Physical activity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AEE (kcal/day) | PAL | Sedentary time (min/day) | Light-intensity activity (min/day) | MVPA (min/day) | |

| Body Composition | |||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.08 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.02 |

| Waist Circumference (cm) | 0.10 | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| Hip Circumference (cm) | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.25 |

| Cardiorespiratory fitness | |||||

| ⩒O2 peak (L/min)a,b,c,d | 0.43† | 0.39† | −0.22 | 0.11 | 0.48† |

| ⩒O2 peak (ml/kg/min)a,b,c,d | 0.28* | 0.35† | −0.26* | 0.16 | 0.32† |

Dependent variable covariates (P < 0.05): alevel of spinal cord lesion, bage, csex and dneurological completeness of injury

Abbreviations: AEE, activity energy expenditure; BMI, body mass index; MVPA, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; PAL, physical activity level; ⩒O2 peak, peak oxygen uptake. * P < 0.05. †P < 0.01.

Figure 1.

Comparison of absolute (L/min, panel A) and relative (ml/kg/min; panel B) cardiorespiratory fitness (⩒O2 peak) between participants with chronic paraplegia, grouped by habitual volume of MVPA (LOW, < 40 minutes/week; MOD, 40–149 minutes/week and; HIGH, ≥ 150 minutes/week). Fig. 1B is overlaid with categories for normative ⩒O2 peak values, specific to individuals with paraplegia(17).

† Significant difference between groups (P < 0.005)

* Significant difference between HIGH vs LOW MVPA (P < 0.003).

Associations of physical activity dimensions, body composition characteristics and cardiorespiratory fitness with biomarkers of cardiometabolic disease

Part correlation coefficients between ⩒O2 peak, physical activity dimensions, body composition characteristics (all independent variables) and a range of markers of metabolic regulation, cardiovascular health and inflammation are shown in Table 3. Dimensions of objectively measured physical activity were not associated with biomarkers of metabolic regulation, cardiovascular health or inflammation. Larger relative ⩒O2 peak was only associated with improved insulin sensitivity (r = 0.37, P = 0.03). No significant associations were observed between absolute ⩒O2 peak and cardiometabolic health biomarkers. Central adiposity (i.e. larger waist circumference) was moderately associated with greater insulin resistance, inflammation, TG concentrations and depressed HDL-C. Greater BMI and hip-circumference was also moderately associated with unfavourable markers of metabolic regulation and CRP concentrations.

Table 3. Part correlation coefficients, with adjustments for covariates where indicated, between independent variables (cardiorespiratory fitness, dimensions of physical activity and body composition characteristics) and dependent variables (metabolic regulation, cardiovascular health and inflammatory markers).

| Cardiorespiratory fitness | Dimensions of physical activity | Body composition characteristics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ⩒O2 peak (L/min) | ⩒O2 peak (ml/kg/min) | AEE (kcal/day) | PAL | Sedentary time (min/day) | Light-intensity (min/day) | MVPA (min/day) | BMI (kg/m2) | Waist circumference (cm) | Hip circumference (cm) | |

| Metabolic regulation | ||||||||||

| Fasting serum insulina | −0.11 | −0.26 | −0.09 | −0.14 | 0.09 | −0.11 | −0.13 | 0.44† | 0.28 | 0.38* |

| Fasting plasma glucoseb | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.06 |

| HOMA2-IRa | −0.15 | −0.32 | −0.13 | −0.19 | 0.15 | −0.14 | −0.16 | 0.46† | 0.34* | 0.42† |

| HOMA2-β | −0.10 | −0.22 | −0.10 | −0.11 | 0.12 | −0.14 | −0.16 | 0.51† | 0.29 | 0.42* |

| HOMA2-Sa | 0.22 | 0.37* | 0.13 | 0.19 | −0.22 | 0.19 | 0.16 | −0.41† | −0.33* | −0.41† |

| Cardiovascular health | ||||||||||

| Total cholesterol | −0.24 | −0.18 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.06 | −0.02 | −0.15 |

| HDL-Cc | −0.30 | −0.17 | −0.24 | −0.17 | 0.13 | −0.08 | −0.25 | −0.23 | −0.32* | −0.17 |

| LDL-C | −0.13 | −0.07 | 0.12 | 0.16 | −0.17 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.04 | −0.04 | −0.27 |

| Triacylglycerol | −0.06 | −0.16 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.11 | −0.14 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.38* | 0.29 |

| Inflammatory markers4 | ||||||||||

| CRP | 0.11 | −0.09 | 0.06 | 0.01 | −0.10 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.47* | 0.43* | 0.39* |

| IL-6 | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.10 | 0.06 | −0.21 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.33 | 0.38* | 0.08 |

Dependent variable covariates (P < 0.05): alevel of spinal cord lesion, btime since injury and, csex.

Abbreviations: AEE, activity energy expenditure; BMI, body mass index; CRP, c-reactive protein; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HOMA2, homeostasis model assessment; IR, insulin resistance; β, pancreatic β-cell function; S, sensitivity; IL-6, interleukin-6; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MVPA, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; PAL, physical activity level; ⩒O2 peak, peak oxygen uptake.

*P < 0.05. †P < 0.01.

Discussion

These data suggest that higher normalised AEE (PAL) and MVPA were moderately associated with higher cardiorespiratory fitness. Both absolute and relative ⩒O2 peak were significantly higher in individuals with SCI that habitually achieved general population MVPA guidelines (≥150 minutes/week) compared to those that perform <40 minutes/week. None of the objectively assessed physical activity dimension were associated with biomarkers of cardiometabolic health. We have previously argued that achieving cardiometabolic health benefits in persons with SCI might be more complex than simply prescribing exercise.34 This may be because upper-body MVPA alone creates insufficient metabolic stress to adequately modulate energy balance and body composition. In support of this, no associations were observed between physical activity dimensions and body composition variables. However, numerous body composition characteristics were significantly associated with biomarkers of metabolic regulation, cardiovascular health and inflammation.

Dimensions of physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness

In the rehabilitation setting, Nooijen et al.,35 objectively assessed physical activity over 48 hours, finding that physical activity levels were associated with ⩒O2 peak. The present study reveals that PAL and MVPA had the strongest associations with relative ⩒O2 peak, although sedentary time also had a weak association. Greater benefits in ⩒O2 peak are seen with volumes more akin to non-disabled MVPA guidelines than PAG-SCI. Considering that light-intensity activity (which encompasses non-exercise activity thermogenesis; NEAT) was not associated with ⩒O2 peak, it could be argued that purposeful exercise above the intensity threshold of MVPA is necessary to improve cardiorespiratory fitness. However, this is difficult to determine when you consider physical activity is a multidimensional construct, whereby no single dimension will adequately reflect an individual’s physical activity.11 For example there are multiple physical activity profiles, whereby one person might have high MVPA (through a bout of structured exercise) and high cardiorespiratory fitness but a low NEAT. In this scenario, NEAT may therefore appear not important (on its own), but of course the situation is more complex than this. For the time being, interventions should be feasible, yet challenging enough (through higher-intensity exercise and greater volumes of MVPA) to increase cardiorespiratory fitness in this population. Moreover, as only 13% of the cohort performed any vigorous-intensity physical activity (≥ 6 METS), future studies should examine whether such unique characteristics of physical activity could be manipulated to improve cardiometabolic health in this population.36

Cardiorespiratory fitness and biomarkers of cardiometabolic disease

Dimensions of physical activity are highly variable from day-to-day,29 whereas cardiorespiratory fitness represents a more stable measure that could be used as a surrogate for long-term physical activity behaviours. Cardiorespiratory fitness has been suggested to be a more clinically meaningful prognostic measure than physical activity, primarily because quantifying ⩒O2 peak has lower measurement error and is highly reproducible.37 However, of all the cardiometabolic outcomes, ⩒O2 peak was only significantly associated with insulin sensitivity in persons with SCI. While cardiorespiratory fitness has been identified as the most important risk factor for clustered cardiometabolic risk in non-disabled individuals37,38 this relationship is not necessarily causal. Higher fitness could simply be a proxy for other improved outcomes. Nevertheless, an increase of 3 ml/kg/min in lower-body ⩒O2 peak in able-bodied individuals is similar to a 1 mmol/L drop in fasting plasma glucose, a 7cm reduction in waist circumference or a 5 mmHg reduction in systolic blood pressure.39 Such increases in cardiorespiratory fitness have also been associated with a 19% reduction in CVD mortality.20 However, due to a lack of strong epidemiological evidence in persons with SCI, we do not currently know whether upper-body cardiorespiratory fitness predicts future health-related endpoints or mortality in this population. The non-significant ‘trivial’ and ‘weak’ associations in this present study may suggest that the substantially reduced cardiorespiratory capacities assessed in persons with SCI plays less of a role in cardiometabolic protection than the substantially higher cardiorespiratory capacities measured in the general population. Indeed, recent research in 140 participants with SCI also demonstrated no significant associations between ⩒O2 peak and metabolic syndrome component risk factors.40 The precise physiological mechanisms for this remain unclear, but are probably related to loss of functional innervation, atrophy of the substantial lower-limb skeletal muscle mass and impaired cardiovascular function observed in persons with SCI.

Dimensions of physical activity and body composition characteristics

The data reported herein, which was collected over 7-days of habitual free-living using a validated multi-sensor device calibrated for each individual participant,26 does not report any associations between specific physical activity dimensions and body composition characteristics. However, previous cross-sectional evidence reported significant (P < 0.01) associations between self-reported physical activity and body composition characteristics (r = −0.62 and −0.67 for trunk fat mass and percentage body fat, respectively) in persons with SCI.41 These body composition variables were measured using a more precise measure of adiposity (dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; DXA), which might explain the discrepancy to the findings from this current study. Paraplegic participants that performed ≥ 25 minutes/day leisure time physical activity (LTPA) have also been shown to have a significantly lower BMI and waist circumference than inactive participants.42 An important caveat is that these two aforementioned studies41,42 actually measured components of ‘exercise’, which a planned, structured, repetitive and intentional movement intended to improve fitness.43 This is a different construct to what was assessed in this current study, physical activity, which is any movement carried out by skeletal muscles that requires energy (encapsulating both activities of daily living and LTPA). Participants in these studies performed a large volume of ‘exercise’; 376 ± 59 min/week,41 > 175 min/week,42 and presumably this is in addition to other activities of daily living. It may be that a higher level of physical activity than that observed in the cohort in this current study is necessary to modulate body composition characteristics in persons with SCI.

Dimensions of physical activity and biomarkers of cardiometabolic disease

No significant associations between dimensions of physical activity and biomarkers of cardiometabolic disease were observed in this current study, which is in contrast to other research that objectively assessed physical activity in this population.35 These findings were in persons with acute not chronic SCI and physical activity was only assessed over two consecutive weekdays, as opposed to a whole week. However, physical activity has previously demonstrated moderate41 and large44 positive associations with HDL-C and sport participation has also been negatively associated with total cholesterol and LDL-C (r = −0.33 and −0.40, respectively).45 It is worth pointing out that despite comparative sample sizes (n = 20–37) in these studies, significant correlations were considerably stronger than those presented in the present study. These observations were reliant on subjective self-report measures, which can quantify a person’s perception of physical activity, rather than their actual physical activity.46 Therefore, it is possible that subjective methods capture something different (i.e. overall lifestyle or their care about their health) to unidimensional physical activity from objective measures, which has a positive effect on associations with cardiometabolic health.

A recent systematic review concluded physical activity may improve inflammatory biomarkers in persons with SCI.47 However, the studies reviewed were noted to have a high risk of bias and provided ‘very low’ levels of evidence. Nevertheless, our inability to detect significant associations between dimensions of physical activity and any cardiometabolic health biomarkers was somewhat unexpected. In keeping with the wider SCI population,48 the majority of our sample is inactive (87% have a PAL ≤ 1.6). The range of PAL was relatively small (1.21–1.89) compared to the wider non-disabled population, which can range from 1.2 for sedentary individuals to ∼ 4.0 for professional endurance athletes.49 As the strength of a correlation is somewhat dependent on the range of values in the sample, this might partly explain why no associations were reported between physical activity dimensions and cardiometabolic health biomarkers, in this present study.

Body composition characteristics and biomarkers of cardiometabolic disease

Considering the substantial multiple correlations between body composition characteristics and biomarkers of cardiometabolic health, it could be argued that body fatness (particularly the accumulation of central adiposity) is the most important consideration in persons with SCI. Overweight middle aged men who were fit and active have previously displayed a poorer profile for various inflammatory and metabolic outcomes compared to fit and active lean counterparts.50 Seemingly, when an objective measure of physical activity is used, adiposity appears more important than physical activity. These findings, albeit in a highly active non-disabled population, are consistent with the data presented in this current study. Energy restriction, combined with regular physical activity appears to be the most effective treatment for obesity51,52 and an important strategy for the management of T2D.53 As these conditions are prevalent in persons with SCI,2,3,23 it seems surprising that there is a paucity of research focussing on weight management through combined diet and exercise interventions in this population. Only one study appears to have implemented a weight management program, with weekly classes in nutrition and exercise behaviour change.54 A significant weight loss was achieved (Δ −3.5 ± 3.1 kg) over 12 weeks, with greater weight loss being associated with a greater reduction in total cholesterol (r > 0.4). Research in overweight non-disabled individuals has also revealed associations between changes in weight loss and inflammatory biomarkers.55 It is clear from the present study that, in individuals with SCI, a lower BMI, waist and hip circumference is associated with favourable cardiometabolic health. This is in conjunction with previous research that has demonstrated higher BMI is linked to unfavourable lipid profiles in persons with SCI (significantly lower HDL-C and higher total cholesterol, LDL-C and TG concentrations).56

Limitations

It should be noted that the associations observed in this cross-sectional study are not indicative of cause and effect. Inventive, carefully controlled cohort studies are required to assess the impact of differing dimensions of physical activity on body composition, cardiorespiratory fitness and biomarkers of cardiometabolic health. The sample size of this current study was too small to better understand the variance in specific cardiometabolic health outcomes, through the development of ‘composite’ models incorporating multiple dimensions of physical activity. A measure of spasticity (i.e. Modified Ashworth Scale) was not included in this study, which could be deemed a limitation. Spasticity has been related to variables of body composition and metabolic profile in persons with SCI57,58 and studies should account for this as an additional covariate in future analyses. Another limitation of this study is the use of crude anthropometric measurements, rather than more accurate methods (magnetic resonance imaging or DXA scan) to assess body composition variables such as lean body mass and fat free mass. Nevertheless, these data highlight the importance of weight management and reducing central adiposity in this population. A further consideration is that only fasting measures of cardiometabolic health were reported. Responses to mixed meal or oral glucose tolerance tests (i.e. postprandial lipaemia and glycaemia) might reveal different associations and should be assessed in future research studies.

Conclusion

Despite physical activity being associated with cardiorespiratory fitness, stronger and more consistent associations were observed between high body fat content and unfavourable biomarkers of cardiometabolic health. Given these findings, the regulation of energy balance (potentially through the manipulation of both diet and physical activity) should be an important consideration for researchers and clinicians looking to improve cardiometabolic health in persons with SCI.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the commitment of participants involved in this study. The authors would also like to thank the University of Bath for the financial support, through generous donations to the DisAbility Sport and Health Research Group from Roger and Susan Whorrod and the Medlock Charitable Trust.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors None.

Funding None.

Conflict of interest None.

Ethics approval None.

ORCID

James LJ Bilzonhttp://orcid.org/0000-0002-6701-7603

References

- 1.Chamberlain JD, Meier S, Mader L, von Groote PM, Brinkhof MW.. Mortality and longevity after a spinal cord injury: systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2015;44(3):182–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.LaVela SL, Weaver FM, Goldstein B, Chen K, Miskevics S, Rajan S, et al. Diabetes mellitus in individuals with spinal cord injury or disorder. J Spinal Cord Med. 2006;29(4):387–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai YJ, Lin CL, Chang YJ, Lin MC, Lee ST, Sung FC, et al. Spinal cord injury increases the risk of Type 2 diabetes: a population-based cohort study. Spine Journal. 2014;14(9):1957–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powell KE, Paluch AE, Blair SN.. Physical activity for health: What kind? How much? How intense? On top of what? Annu Rev Publ health. 2011;32:349–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith AD, Crippa A, Woodcock J, Brage S.. Physical activity and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diabetologia. 2016:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ginis KA, Hicks AL, Latimer AE, Warburton DE, Bourne C, Ditor DS, et al. The development of evidence-informed physical activity guidelines for adults with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2011;49(11):1088–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans N, Wingo B, Sasso E, Hicks A, Gorgey AS, Harness E.. Exercise Recommendations and Considerations for Persons With Spinal Cord Injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(9):1749–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Zepetnek JOT, Pelletier CA, Hicks AL, MacDonald MJ.. Following the Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults With Spinal Cord Injury for 16 Weeks Does Not Improve Vascular Health: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(9):1566–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tweedy SM, Beckman EM, Geraghty TJ, Theisen D, Perret C, Harvey LA, et al. Exercise and sports science Australia (ESSA) position statement on exercise and spinal cord injury. J Sci Medicine Sport 2017;20(2):108–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nightingale TE, Rouse PC, Thompson D, Bilzon JLJ.. Measurement of Physical Activity and Energy Expenditure in Wheelchair Users: Methods, Considerations and Future Directions. Sports Medicine - Open. 2017;3(1):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson D, Peacock O, Western M, Batterham AM.. Multidimensional physical activity: an opportunity, not a problem. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2015;43(2):67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine JA, Vander Weg MW, Hill JO, Klesges RC.. N on-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis: The Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon of Societal Weight Gain. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(4):729–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Healy GN, Wijndaele K, Dunstan DW, Shaw JE, Salmon J, Zimmet PZ, et al. Objectively Measured Sedentary Time, Physical Activity, and Metabolic Risk The Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab). Diabetes Care. 2008;31(2):369–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manns PJ, Dunstan DW, Owen N, Healy GN.. Addressing the Nonexercise Part of the Activity Continuum: A More Realistic and Achievable Approach to Activity Programming for Adults With Mobility Disability? Physical Therapy. 2012;92(4):614–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carson V, Ridgers ND, Howard BJ, Winkler EAH, Healy GN, Owen N, et al. Light-Intensity Physical Activity and Cardiometabolic Biomarkers in US Adolescents. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verschuren O, Dekker B, van Koppenhagen C, Post M.. Sedentary Behavior in People With Spinal Cord Injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(1):173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janssen TWJ, Dallmeijer AJ, Veeger D, van der Woude LHV.. Normative values and determinants of physical capacity in individuals with spinal cord injury. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2002;39(1):29–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haisma JA, van der Woude LHV, Stam HJ, Bergen MP, Sluis TAR, Bussmann JBJ.. Physical capacity in wheelchair-dependent persons with a spinal cord injury: a critical review of the literature. Spinal Cord. 2006;44(11):642–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blair SN, Kohl HW 3rd, Paffenbarger RS Jr., Clark DG, Cooper KH, Gibbons LW.. Physical fitness and all-cause mortality. A prospective study of healthy men and women. JAMA. 1989;262(17):2395–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee DC, Sui XM, Artero EG, Lee IM, Church TS, McAuley PA, et al. Long-Term Effects of Changes in Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Body Mass Index on All-Cause and Cardiovascular Disease Mortality in Men The Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study. Circulation. 2011;124(23):2483–U348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noreau L, Shephard RJ.. Spinal-cord injury, exercise and quality-of-life. Sports Medicine. 1995;20(4):226–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Church T.The Low-fitness Phenotype as a Risk Factor: More Than Just Being Sedentary? Obesity. 2009;17:S39-S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spungen AM, Adkins RH, Stewart CA, Wang J, Pierson RN, Waters RL, et al. Factors influencing body composition in persons with spinal cord injury: a cross-sectional study. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95(6):2398–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorgey AS, Dolbow DR, Dolbow JD, Khalil RK, Castillo C, Gater DR.. Effects of spinal cord injury on body composition and metabolic profile - Part I. J Spinal Cord Med. 2014;37(6):693–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gorgey AS, Mather KJ, Gater DR.. Central adiposity associations to carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in individuals with complete motor spinal cord injury. Metabolism. 2011;60(6):843–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nightingale TE, Walhin JP, Thompson D, Bilzon JLJ.. Predicting physical activity energy expenditure in wheelchair users with a multisensor device. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine. 2015;1(1):bmjsem-2015-000008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nightingale TE, Walhin J-P, Turner JE, Thompson D, Bilzon JLJ.. The influence of a home-based exercise intervention on human health indices in individuals with chronic spinal cord injury (HOMEX-SCI): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17:284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goosey-Tolfrey VL.BASES physiological testing guidelines: The disabled athlete. In: Winter EM, Jones A.M, Davison R.C.R, Bromley P.D, Mercer T.H, editor. Sport and Exercise Physiology Testing Guidelines. USA: Routledge; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aadland E, Ylvisåker E.. Reliability of Objectively Measured Sedentary Time and Physical Activity in Adults. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0133296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scheers T, Philippaerts R, Lefevre J.. Variability in physical activity patterns as measured by the SenseWear Armband: how many days are needed? Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112(5):1653–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levy JC, Matthews DR, Hermans MP.. Correct homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) evaluation uses the computer program. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(12):2191–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friedewald W.T, Fredrickson D.S, Levy RI.. Estimation of concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of preparatove ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18(6):499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maxwell SE, Delaney H.D.. Designing experiments and analyzing data: a model comparison perspective. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nightingale TE, Bilzon J.. Cardiovascular Health Benefits of Exercise in People With Spinal Cord Injury: More Complex Than a Prescribed Exercise Intervention? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(6):1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nooijen CFJ, de Groot S, Postma K, Bergen MP, Stam HJ, Bussmann JBJ, et al. A more active lifestyle in persons with a recent spinal cord injury benefits physical fitness and health. Spinal Cord. 2012;50(4):320–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nightingale TE, Metcalfe RS, Vollaard NBJ, Bilzon JLJ.. Exercise guidelines to promote cardiometabolic health in spinal cord injured humans: time to raise the intensity? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(8):1693–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaminsky LA, Arena R, Beckie TM, Brubaker PH, Church TS, Forman DE, et al. The Importance of Cardiorespiratory Fitness in the United States: The Need for a National Registry A Policy Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127(5):652–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knaeps S, Lefevre J, Wijtzes A, Charlier R, Mertens E, Bourgois JG.. Independent Associations between Sedentary Time, Moderate-To-Vigorous Physical Activity, Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Cardio-Metabolic Health: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0160166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kodama S, Saito K, Tanaka S, Maki M, Yachi Y, Asumi M, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a quantitative predictor of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in healthy men and women: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;301(19):2024–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Groot S, Adriaansen JJ, Tepper M, Snoek GJ, van der Woude LHV, Post MWM. . Metabolic syndrome in people with a long-standing spinal cord injury: associations with physical activity and capacity. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41(11):1190–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones LM, Legge M, Goulding A.. Factor analysis of the metabolic syndrome in spinal cord-injured men. Metab-Clin Exp. 2004;53(10):1372–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buchholz AC, Martin Ginis KA, Bray SR, Craven BC, Hicks AL, Hayes KC, et al. Greater daily leisure time physical activity is associated with lower chronic disease risk in adults with spinal cord injury. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2009;34(4):640–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM.. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985;100(2):126–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manns PJ, McCubbin JA, Williams DP.. Fitness, inflammation, and the metabolic syndrome in men with paraplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(6):1176–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Janssen TWJ, vanOers C, vanKamp GJ, TenVoorde BJ, vanderWoude LHV, Hollander AP.. Coronary heart disease risk indicators, aerobic power, and physical activity in men with spinal cord injuries. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78(7):697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loney T, Standage M, Thompson D, Sebire SJ, Cumming S.. Self-report vs. objectively assessed physical activity: which is right for public health? J Phys Act Health. 2011;8(1):62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Neefkes-Zonneveld CR, Bakkum AJ, Bishop NC, van Tulder MW, Janssen TW.. Effect of long-term physical activity and acute exercise on markers of systemic inflammation in persons with chronic spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(1):30–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buchholz AC, McGillivray CF, Pencharz PB.. Physical activity levels are low in free-living adults with chronic paraplegia. Obes Res. 2003;11(4):563–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Westerterp KR.Physical activity and physical activity induced energy expenditure in humans: measurement, determinants, and effects. Frontiers in Physiology. 2013;4:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dixon NC, Hurst TL, Talbot DCS, Tyrrell RM, Thompson D.. Effect of short-term reduced physical activity on cardiovascular risk factors in active lean and overweight middle-aged men. Metabolism. 2013;62(3):361–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Foster-Schubert KE, Alfano CM, Duggan CR, Xiao L, Campbell KL, Kong A, et al. Effect of diet and exercise, alone or combined, on weight and body composition in overweight-to-obese post-menopausal women. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 2012;20(8):1628–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johns DJ, Hartmann-Boyce J, Jebb SA, Aveyard P.. Diet or Exercise Interventions vs Combined Behavioral Weight Management Programs: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Direct Comparisons. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(10):1557–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nathan DM, Buse JB, Davidson MB, Ferrannini E, Holman RR, Sherwin R, et al. Medical Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes: A Consensus Algorithm for the Initiation and Adjustment of Therapy: A consensus statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(1):193–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen Y, Henson S, Jackson AB, Richards JS.. Obesity intervention in persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2006;44(2):82–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nicklas BJ, Ambrosius W, Messier SP, Miller GD, Penninx B, Loeser RF, et al. Diet-induced weight loss, exercise, and chronic inflammation in older, obese adults: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(4):544–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Groot S, Post MW, Snoek GJ, Schuitemaker M, van der Woude LH.. Longitudinal association between lifestyle and coronary heart disease risk factors among individuals with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2013;51(4):314–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gorgey AS, Chiodo AE, Zemper ED, Hornyak JE, Rodriguez GM, Gater DR.. Relationship of spasticity to soft tissue body composition and the metabolic profile in persons with chronic motor complete spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2010;33(1):6–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jung IY, Kim HR, Chun SM, Leigh JH, Shin HI.. Severe spasticity in lower extremities is associated with reduced adiposity and lower fasting plasma glucose level in persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2017;55(4):378–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]