Abstract

Introduction

More than one-third of women in the U.S. have engaged in heterosexual anal intercourse (HAI), but little is known regarding women’s perceptions of HAI and motivations for engaging in this sexual behavior.

Aim

This study aimed to explore U.S. women’s motivations for engaging in HAI and to investigate how they navigate HAI in the context of sexual relationships.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20 women, ages 18–50 years old, who had engaged in anal intercourse with a male partner within the past 3 months. The interview guide was developed utilizing a conceptual framework based on the Theory of Planned Behavior.

Main Outcome Measure

Thematic content analysis was performed, and salient themes were identified.

Results

Salient themes were identified in all key components of the construct, including attitudes toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Women’s intent to engage in HAI was influenced by their attitudes toward HAI and level of control and trust with their partners. Primary motivators were partner and personal pleasure and sexual curiosity and experimentation.

Conclusion

The Theory of Planned Behavior construct was well suited to explore factors influencing women’s intent to engage in HAI. Most women perceive negative societal norms toward HAI. Although this does not appear to affect intention to engage in HAI, it does affect disclosure of this sexual activity with friends and healthcare providers. It is important for healthcare providers to provide open, non-judgmental counseling regarding HAI to decrease stigma, enhance communication, and improve sexual health.

Benson LS, Gilmore KC, Micks EA, et al. Perceptions of Anal Intercourse Among Heterosexual Women: A Pilot Qualitative Study. Sex Med 2019;7:198–206.

Key Words: Heterosexual Anal Intercourse, Penile-Anal Intercourse, Sexual Behavior, Theory of Planned Behavior, Qualitative Methods

Introduction

More than one-third of women in the U.S. have engaged in heterosexual anal intercourse (HAI).1 Although recent studies have helped elucidate correlates of HAI in the U.S., little is known regarding women’s perceptions of HAI and motivations for engaging in this sexual behavior.2 Research interest in HAI stems from the higher transmission rates of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections for receptive anal vs vaginal intercourse, potentially lower condom use rates with HAI, and the significant stigma surrounding HAI.1, 3, 4, 5 Because HAI has become a more common part of the sexual repertoire, it has become increasingly important to understand women’s perceptions of, and experiences with, HAI.6 Despite the frequency of HAI among heterosexual women, there is a paucity of data on specific practices among the U.S. population. HAI is underreported by women and often considered a taboo topic for discussion by both patients and physicians.3, 7

Knowledge regarding women’s attitudes toward HAI is especially limited.6 1 focus group study found that women reported engaging in HAI as a result of drug and alcohol use, exchange of drugs and money with sex, personal enjoyment, and in the setting of coercion or violence.8 This study was limited by inclusion of women recruited through an outpatient drug treatment program, and thus distinct from a general U.S. population. A more recent focus group study demonstrated themes of curiosity, pain, pleasure, and stigma.9 Although HAI is an emerging sexual norm, attitudes toward HAI are complex and not yet well understood. Much of the literature treats HAI as a riskier substitute for penile-vaginal intercourse.6

Evidence suggests that HAI is associated with an 18-fold increased risk for HIV transmission for women, vs receptive penile-vaginal intercourse.3 However, the role that HAI plays in HIV transmission remains incompletely understood, because of a lack of knowledge regarding infectiousness of HAI, frequency of HAI, and frequency of HAI in the setting of sexual violence.3 In addition to any risks inherent to HAI, women are also less likely to discuss this practice with their healthcare providers due to stigma.9 It is important to understand women’s motivations and practices regarding HAI to understand better how to counsel them regarding their risks.

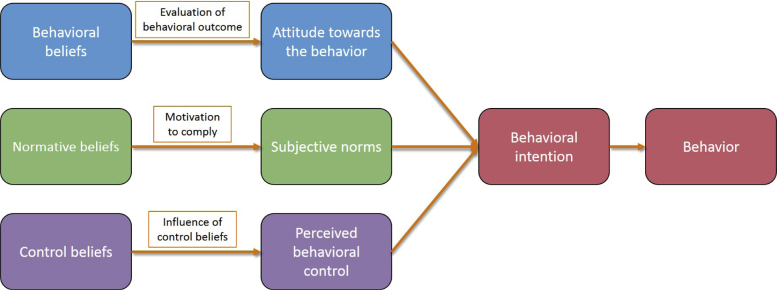

This study sought to explore perceptions and behaviors surrounding HAI among a population of U.S. women, utilizing a theoretical framework based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). The TPB is a theoretical construct linking individual motivational factors with the likelihood of performing a specific behavior (Figure 1).10 The TPB construct states that subjective norms, attitude toward a behavior, and perceived control shape an individual’s behavioral intentions. This framework has been used to predict a large variety of health behaviors, including sexual behaviors.11, 12 Attitude is determined by an individual’s evaluation of their own behavioral beliefs toward the behavior. Subjective norms are formed by an individual’s perception of the normative beliefs of society and others. Perceived control refers to an individual’s beliefs regarding the presence of facilitators or barriers to performance of the behavior. The study authors hypothesized that this theoretical construct would be well-suited to explain women’s intent to engage in HAI. The TPB framework was used to explore not only women’s own attitudes toward HAI, but also their normative beliefs toward HAI and their perceived control over engaging in these activities in their sexual encounters.

Figure 1.

Theory of Planned Behavior model.

Materials and Methods

Study Participants

Participants were recruited for semi-structured in-depth interviews. One-on-one interviews were specifically chosen given the sensitive nature of the topic. All participants were English-speaking women, ages 18–50 years old, who self-identified as heterosexual and had engaged in anal intercourse with a male partner within the past 3 months. This study was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

Recruitment

Participants in the greater Seattle area were recruited via posted advertisements in local print and online newspapers, on Craigslist, and on a University of Washington research recruitment website. Recruitment materials stated that the University of Washington was conducting a study regarding sexual behavior, included eligibility criteria, and advertised that participants would receive a $50 gift card in return for participating in an interview lasting ≤1 hour in length. The recruitment materials instructed women to either e-mail or call the research coordinator if interested. Potential participants were then screened over the phone by the female research coordinator for study eligibility. Only the research coordinator had access to this contact information, which was kept in a secure file.

Study Procedures

All interviews were conducted in person with 1 of 2 female researchers (the first author, an obstetrician/gynecologist, and the second author, a research scientist). Interviews took place at the University of Washington in a private office. Participants did not meet the researchers before the interview and had no knowledge of the researchers other than their roles at the University of Washington and a basic overview of the study. Participants had no further contact with the research team after completion of the interview.

All participants provided written informed consent. Participants were then instructed to complete a demographic survey on a secure tablet using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture). The researchers did not have access to the demographic survey data at the time of the interviews. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Washington. REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data collection for research studies.13

The conceptual framework was developed based on the TPB, as described above (Figure 1).10 This conceptual framework was then used to develop a semi-structured interview guide. All interviews were digitally recorded and subsequently transcribed by a professional transcription service. All participants were assigned a randomly generated study identification number. Both the demographic surveys and interview transcriptions were stored with these study identification numbers.

Data Analysis

An a priori codebook was developed using the TPB framework. 2 researchers independently coded the transcripts. Data were analyzed using a thematic content analysis approach. The codebook was revised as the interviews were analyzed. The 2 researchers added and changed codes during the interview process to incorporate emerging themes. All discrepancies between researchers were resolved by discussion and consensus. Salient themes included in the analysis were the third or higher order codes that were coded in ≥80% of the interviews. Each of these codes are described in detail along with representative quotations. Data analysis was conducted using Dedoose software.

Results

In-depth interviews were conducted with 20 study subjects. Median interview length was 33 minutes and 54 seconds. Demographic characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. Median number of lifetime sexual partners was 11 (interquartile range [IQR] 4–28), and median number of lifetime anal sexual partners was 2 (IQR 1–3). Mean age of first anal intercourse was 24 years, ranging from 15–42 years. Half of participants reported engaging in HAI <1 time per month, and only 15% report engaging in HAI ≥1 time per week. Condoms were reported to be used always for HAI by 35% of participants, most of the time by 5%, rarely by 5%, and never by 55%.

Table 1.

Study participant demographics

| Study participants n = 20 |

|

|---|---|

| Age (in years), mean ± SD | 32.2 ± 8.8 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Asian | 1 (5) |

| Hispanic | 1 (5) |

| White | 15 (75) |

| Multiple/Other | 3 (15) |

| Education level, n (%) | |

| <High school | 1 (5) |

| High school graduate | 4 (20) |

| College graduate | 15 (75) |

| Relationship status, n (%) | |

| Single, not in a relationship | 6 (30) |

| In a relationship, not cohabiting | 8 (40) |

| In a relationship, cohabiting | 2 (10) |

| Married | 4 (20) |

| Yearly household income, n (%) | |

| <$25,000 | 7 (35) |

| $25,000–49,999 | 9 (45) |

| $50,000–99,999 | 2 (10) |

| ≥$100,000 | 2 (10) |

| Frequency of HAI in past 3 months, n (%) | |

| <1 time/mo | 10 (50) |

| 1–3 times/mo | 7 (35) |

| 1 time/wk | 1 (5) |

| 2–3 times/wk | 2 (10) |

| Lifetime partners (vaginal), median (IQR) | 11 (4-29) |

| Lifetime partners (anal), median (IQR) | 2 (1-3) |

| Age at first HAI (in years), mean ± SD | 23.8 ± 7.4 |

HAI = heterosexual anal intercourse; IQR = interquartile range.

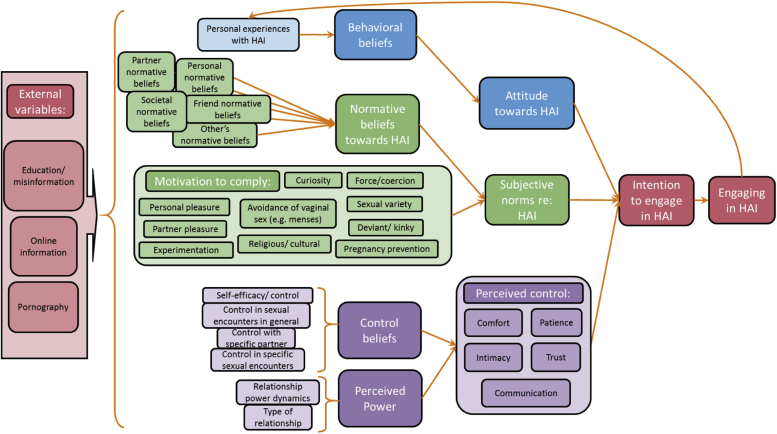

The conceptual framework was developed based on the TPB model (Figure 2). The final codebook is shown in Table 2. Codes were organized under parent codes representing the key components of the conceptual framework: attitude, subjective norm, perceived control, and external variables. As indicated in Table 2, codes from all 4 of these categories met criteria for inclusion. 16 salient themes were identified. 6 of these themes emerged during the analysis; the remainder were included in the original codebook.

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework based on Theory of Planned Behavior model. HAI = heterosexual anal intercourse.

Table 2.

HAI Qualitative Study Codebook

| 1st order codes | 2nd order codes | 3rd order codes | 4th order codes |

|---|---|---|---|

| External variables | Education/information and misinformation | ||

| Pornography∗ | |||

| Sex-positive individuals/information | |||

| Attitudes toward HAI | Behavioral beliefs | Personal beliefs∗ | Positive personal beliefs |

| Negative personal beliefs | |||

| Change in personal beliefs | |||

| Ambivalence | |||

| Body image | |||

| Shame | |||

| Personal experience | Positive personal experience | ||

| Negative personal experience∗ | |||

| Change in personal experience | |||

| Subjective norms | Normative beliefs | Societal beliefs∗ | Positive societal beliefs |

| Negative societal beliefs∗ | |||

| Change in societal beliefs | |||

| Partner beliefs | Positive partner beliefs | ||

| Negative partner beliefs | |||

| Friend beliefs∗ | Positive friend beliefs | ||

| Negative friend beliefs | |||

| Family beliefs | Positive family beliefs | ||

| Negative family beliefs | |||

| Others’ beliefs | |||

| Motivators | Partner pleasure∗ | ||

| Personal pleasure∗ | |||

| Sexual exploration/experimentation or curiosity∗ | |||

| Kinky/deviant behavior | |||

| Pregnancy prevention | |||

| Religion or perceived virginity | |||

| Avoidance of vaginal sex during menses | |||

| STI prevention | |||

| Force or coercion | |||

| Perceived control in sexual relationships | Control beliefs | Control over sexual encounters in general | High control with sexual encounters in general |

| Low control with sexual encounters in general | |||

| Control with specific partner∗ | High control with specific partner∗ | ||

| Low control with specific partner | |||

| Control with specific sexual encounter | High control with specific sexual encounter | ||

| Low control with specific sexual encounter | |||

| Self-efficacy/control | High self-efficacy/control | ||

| Low self-efficacy/control | |||

| Change in control beliefs | |||

| Perceived power | Type of relationship∗ | Relationship power dynamics | |

| Change in relationship dynamics | |||

| Facilitators and barriers to perceived power in a given relationship/encounter∗ | Trust∗ | ||

| Comfort∗ | |||

| Communication∗ | |||

| Intimacy | |||

| Vulnerability | |||

| Patience | |||

| Emotional experience | |||

| Influence of alcohol | |||

| Positive communication | |||

| Negative communication | |||

HAI = heterosexual anal intercourse; STI = sexually transmitted infection.

3rd order or higher order codes that met criteria for inclusion in analysis (occurring in ≥80% of transcripts).

External Variables

Participants described pornography as an external influence on their perceptions of HAI more than any other factor. As an external variable, pornography influences all other domains in the TPB model, especially personal attitudes and societal norms. Although many participants reported not watching pornography themselves, those who did reported mixed effects on their personal attitudes toward HAI. Some of these impressions were negative (“I have never seen pornography in which anal sex looked pleasant to me” [Participant 15]), whereas others were positive (“I watched pornography where that [HAI] was the central subject, and I really liked that” [Participant 1]). Many participants described pornography as contributing to negative societal norms toward HAI and reinforcing damaging stereotypes of women. For example, Participant 19 stated: “I think because of the onslaught of all of the porn that kind of objectifies women and where women are just kind of this free kind of commodity. I’m assuming that women who would engage in anal sex are viewed a bit lower upon because of that.” Participants also described the availability of pornography featuring HAI as normalizing this sexual behavior: “People who like to watch porn can go watch it [HAI]. It’s not like it’s hard to find. So again, I don’t think it’s as shocking or unusual as it used to be” [Participant 18].

Attitudes Toward HAI

Behavioral Beliefs Toward HAI

Women’s normative beliefs toward HAI, including perceived societal stigma toward HAI, influenced their preconceptions of HAI before engaging in this sexual activity; negative preconceptions of HAI did not seem to dissuade women from engaging in HAI for the first time. Some women reported that it sounded physically uncomfortable or painful. For example, Participant 16 stated: “Oh, just imagining a penis going into my anus did not sound very fun at all…sounds really painful.” This negatively influenced their interest in engaging in HAI personally. Others expressed concerns about cultural stigma surrounding women who engage in HAI. Participant 5 stated: “The first thing I think about is that it’s trashy…it’s not something that someone who respects themselves and their body does.” Some participants reported positive personal beliefs toward HAI, often related to sexual curiosity. (“It seems like it’s really adventurous and explorative to like, you know, attempt to find new, like, pleasures and erotic areas of your body” [Participant 4].) Many women also described changes in their beliefs toward HAI over time as they had more personal experiences on which to draw. Participant 4 also stated: “Yeah, I think [my opinion of HAI] completely changed. Because I was—I think I had an expectation, and I had kind of built it up, just based on cultural assumptions and conversations I've had with other women.” Several participants felt not only positively toward HAI for themselves, but they also felt that more women should explore HAI with their partners.

Personal Experience with HAI

Most study participants described a negative early experience with HAI. Typically these experiences were perceived as negative because they were physically painful. Several women also described the experience as negative because they did not consent to it or felt their consent was coerced. Participant 7 stated: “He just kind of jammed it in there. He didn't even like tell me or anything. And I think that's maybe kind of why it hurt? Because it hurt.” Many participants also reported subsequent positive experiences, or a change in their experience engaging in HAI over time. (“I think it is one of those things that, once you kind of are comfortable with it, it’s really rewarding” [Participant 16].) Recent experiences with HAI ranged from negative to positive. Women who had positive experiences with HAI also reported engaging in HAI for their own sexual pleasure.

Subjective Norms

Normative Beliefs

Most participants reported influence from their friends’ normative beliefs toward HAI. Some women described their friends’ views as primarily negative or positive, whereas others reported mixed views among different friends or groups of friends (“It would depend on the friend. Some people would say ‘Oh yeah, I do too,’ and then I would have other friends who I think would be pretty shocked or find it really distasteful.” [Participant 17]). Participants’ perceptions of their friends’ beliefs influenced not only their own views toward HAI, but the degree to which they felt comfortable discussing this sexual behavior with their friends (“But I definitely think it’s stigmatized. I mean, I wouldn’t really talk to my friends, for instance, about it.” [Participant 14]).

Almost all participants described negative societal normative beliefs toward HAI.

And I just feel like, there's just so much shame surrounding it in society. So much, you know, stigma about it, because it is a dirty place, and people don't know how to handle it.” [Participant 6]

Anal sex…is still considered a taboo subject…It’s more the sort of thing...that prostitutes would do or porn stars would do or your wife would do like once or twice and would grit her teeth and just bear it. [Participant 19]

In general, participants reported that their decision-making regarding HAI was not influenced by their belief that the overwhelming majority of women feel that society disapproves of HAI and women who engage in this sexual behavior. However, several participants did express a sense that societal norms likely discourage other women from exploring HAI.

Their view on it is, like, men trying to trick you into something, because so often is portrayed is, like, guys pressuring the girlfriends into doing anal, and in that story, in that narrative, it's always, like, the girlfriend doesn't really want to do it and she does it just kind of to appease him. [Participant 1]

Several participants noted that societal stigma influenced how comfortable they were discussing this sexual activity with their healthcare providers. Participant 17 stated the following:

It’s [HAI] not really put out as an option. You know, when I think about sex education that people might have in high school or younger, or even when you go to see a healthcare provider, there is—it is extraordinarily rare that anal sex is even mentioned as an option for women… I think that kind of increases the taboo around it, because no one really asks that question. And when I think about sexually transmitted infections, you could have it just anally and not have it vaginally or something.

Motivators to Engage in HAI

The most commonly cited motivators for engaging in HAI were partner pleasure, personal pleasure, and sexual exploration or curiosity. All but 1 participant described partner pleasure as a primary motivator. Although many women reported also engaging in HAI for their own pleasure (“It’s like a totally different sensation and a pretty strong orgasm too. Yeah, I really enjoy it” [Participant 16]), others reported continuing to engage in HAI for their partners’ pleasure despite not enjoying it personally (“It’s something that’s for him. It’s something that I’m kind of sacrificing for him” [Participant 5]). A variety of other motivators were discussed by participants, including pregnancy prevention, maintaining perceived virginity status for religious reasons, and avoiding vaginal intercourse during menstruation. Several women also reported a history of coerced or nonconsensual HAI.

Women reported a variety of ways in which HAI was initiated. Some reported that initiation of HAI in specific sexual encounters was always mutual, while for others the male partner primarily initiated HAI; few women reported that they were most frequently the initiator.

Perceived Control

Control Beliefs

The majority of women in this study reported that they were much more likely to engage in HAI when they felt they had a high degree of control in their relationship with a specific partner.

But he like constantly—It was on me if we wanted to keep going? So even during, he would be like, “Is this okay? Are you okay? Do you want to stop?” So I felt like any time I was in control of the situation. I never felt like, “Oh, I have to keep going 'cause he wants to.” Or like—No, I always felt like I was in charge of what was happening. Which is good. [Participant 8]

Women described these relationships as ones in which they had a high level of perceived power and the ability to decline sexual acts with their partners. These relationships were frequently described as longer-term or monogamous relationships. Participants contrasted these relationships or sexual encounters with ones in which they felt a lower degree of control, and subsequently would not feel comfortable engaging in HAI.

I also had kind of a lot of 1-night-stand situations, and I would never have tried that [HAI] in that sort of setting where you meet someone for the first time and you're doing that with them. I don't think I would've been open to it. But just because I—I don't know, I'd hung out with him a lot, and I liked all—I just felt comfortable and like there wasn't any pressure and I could say no if I wanted to and so all that just kind of made me more receptive to…anything he said, I guess. 'Cause I trusted him. [Participant 8]

Participants who had experienced coerced or forced HAI typically experienced this with monogamous partners, but described these relationships as ones where they had lower control.

Perceived Power

Women reported a high level of perceived power in their sexual relationships as a prerequisite to engaging in HAI. Factors that influenced perceived power included type of relationship, trust, comfort, and communication. Regardless of duration or status of relationship, a feeling of trust and comfort with a particular partner generally facilitated a higher degree of control.

I’ve been with a lot of guys, and the guys that I’ve done it [HAI] with are the guys that I’m closer to at least, so it’s more exciting when it’s with someone that I could trust a lot and—like I know that if I wanted to stop, they’d stop. Or I know that they’d try to go slow instead of just stick it in. So that’s exciting when I have a guy that I can super trust with that.” [Participant 20]

Participants described comfort with a particular sexual partner in terms of initiating or declining sexual acts, open communication regarding sex, and their own bodies and exploring sexual behaviors that may at times be physically messy or awkward.

Open communication about sex and about the relationship in general also facilitated a high level of perceived power and control in a relationship.

Yeah, I feel completely confident, comfortable to bring up ideas, to listen to ideas, to respond exactly how I feel. To let him know if I am or not—I don't feel that there will ever be a problem with me letting him know that I don't actually think I’d like that, or let’s try this differently. I feel completely listened to and heard and respected. [Participant 2]

Many women cited good communication as a requirement for engaging in HAI.

Discussion

This study explored women’s decisions to engage in HAI. The TPB construct was applied and found to be well suited to exploring factors influencing women’s intent to engage in HAI. Salient themes were identified in all key components of the construct, including attitudes toward the behavior, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and external factors.

The most commonly cited motivators by the study participants to engage in HAI were partner and personal sexual pleasure and experimentation. Study participants discussed subjective norms at length, and the most common themes explored in the area of normative beliefs were beliefs shared by friends and societal beliefs. Although women reported mixed views from friends, their perceptions of societal beliefs were overwhelmingly negative. This is particularly interesting in the context of HAI as an emerging sexual norm, and women’s desire to participate in HAI regardless of how they feel society might view them. Many women described pornography as normalizing HAI but also contributing to negative societal norms and reinforcing negative stereotypes of women. Most participants cited partner trust, comfort with patient, and open communication as key facilitators of HAI and their sexual relationships in general. Participants also described their level of control in sexual relationships with specific partners to be integral to their experiences with HAI, as well as influence from their own prior experiences with HAI, whether positive or negative.

Recent qualitative literature exploring HAI has revealed many and diverse themes, some of which were identified again in this study.8, 9 The results from this study expanded on several of these themes, and also explored new and different themes, elucidating the varied and complex nature of women’s beliefs and attitudes toward HAI. The novelty of these results lies not in the themes revealed but in the application of the TPB framework to the decision to engage in HAI. This study was also unique in the decision to use individual interviews rather than focus groups, given the sensitive nature of the subject matter.

Despite the overwhelming majority of participants reporting sexual pleasure, curiosity, and experimentation as motivators for engaging in HAI, many participants did report negative personal experiences with HAI. These experiences were typically early sexual experiences and often occurred with lack of consent or coerced consent. The frequency of coerced and nonconsensual intercourse is alarming, and, for HAI in particular, may increase risk of HIV and other infection transmission.3, 14

There are several limitations to the study findings. The small sample size limits the ability to draw broad conclusions, although thematic saturation was reached in this study population. Most of the participants were white, college-educated, and living in or near a single urban area, which limits generalizability of these findings to a more diverse population. These study participants were also people who felt comfortable discussing the details of their sexual behaviors, and may not be representative of the general population. This study also focused on heterosexual penile-anal intercourse and did not explore other anal sexual behaviors. Further research should include a larger, more diverse population. Motivations and attitudes toward HAI are varied and complex, and much remains to be elucidated.

Conclusions

Women’s intent to engage in HAI is influenced by their attitudes toward HAI and level of control and trust with their partners. Most participants perceived negative societal norms toward HAI. These societal normative beliefs did not appear to dissuade women from engaging in HAI, but did appear to affect disclosure of this sexual behavior with friends and healthcare providers. This is an interesting contrast to the emergence of HAI as a sexual norm, a sexual behavior that is increasingly common yet remains a taboo topic for discussion.

This study highlights the need for healthcare providers to provide an environment where sexual behaviors, including HAI, can be discussed freely and without fear of stigma or judgment. A national survey of obstetrician gynecologists revealed that less than half routinely asked their patients about sexual problems, and only 1 in 7 asked about pleasure with sexual activity.15 Furthermore, one-fourth of obstetrician gynecologists reported they had expressed disapproval of their patients’ sexual practices. Healthcare providers have the opportunity to discuss sexual behaviors with patients to provide information and counseling, as well as strategies (eg, condoms) to reduce risks associated with these activities.16

Providers should be encouraged to open a dialogue with their patients to accurately assess for sexual violence or coercion, risk of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, and other health concerns. Open, patient-centered discussion regarding HAI and other sexual behaviors with a healthcare provider in a supportive, nonjudgmental environment can enhance communication, de-stigmatize sexual behaviors, increase risk-reducing behaviors, and improve sexual health.7

Statement of Authorship

Category 1

-

(a)Conception and Design

- Lyndsey S. Benson; Kelly C. Gilmore; Elizabeth A. Micks; Erin McCoy; Sarah W. Prager

-

(b)Acquisition of Data

- Lyndsey S. Benson; Kelly C. Gilmore; Elizabeth A. Micks; Sarah W. Prager

-

(c)Analysis and Interpretation of Data

- Lyndsey S. Benson; Kelly C. Gilmore

Category 2

-

(a)Drafting the Article

- Lyndsey S. Benson

-

(b)Revising It for Intellectual Content

- Lyndsey S. Benson; Kelly C. Gilmore; Elizabeth A. Micks; Erin McCoy; Sarah W. Prager

Category 3

-

(a)Final Approval of the Completed Article

- Lyndsey S. Benson; Kelly C. Gilmore; Elizabeth A. Micks; Erin McCoy; Sarah W. Prager

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding: Supported by the Society of Family Planning Research Fund [grant number SFPRF15-23].

References

- 1.Benson L.S., Martins S.L., Whitaker A.K. Correlates of heterosexual anal intercourse among women in the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1746–1752. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halperin D.T. Heterosexual anal intercourse: Prevalence, cultural factors, and HIV infection and other health risks, Part I. AIDS patient care and STDs. 1999;13:717–730. doi: 10.1089/apc.1999.13.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baggaley R.F., Dimitrov D., Owen B.N. Heterosexual anal intercourse: A neglected risk factor for HIV? Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;69(Suppl 1):95–105. doi: 10.1111/aji.12064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldwin J.I., Baldwin J.D. Heterosexual anal intercourse: An understudied, high-risk sexual behavior. Arch Sex Behav. 2000;29:357–373. doi: 10.1023/a:1001918504344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varghese B., Maher J.E., Peterman T.A. Reducing the risk of sexual HIV transmission: Quantifying the per-act risk for HIV on the basis of choice of partner, sex act, and condom use. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:38–43. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McBride K.R., Fortenberry J.D. Heterosexual anal sexuality and anal sex behaviors: A review. J Sex Res. 2010;47:123–136. doi: 10.1080/00224490903402538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talking to patients about sexuality and sexual health [fact sheet] http://www.arhp.org/publications-and-resources/clinical-fact-sheets/sexuality-and-sexual-health Available at: Accessed September 26, 2018.

- 8.Reynolds G.L., Fisher D.G., Rogala B. Why women engage in anal intercourse: Results from a qualitative study. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44:983–995. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0367-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McBride K.R. Heterosexual women's anal sex attitudes and motivations: A focus group study. J Sex Res. 2017:1–11. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2017.1355437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joel Rudd K.G. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1990. Chapter 6: How individuals use information for health action: Consumer information processing. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simms D.C., Byers E.S. Heterosexual daters' sexual initiation behaviors: Use of the theory of planned behavior. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42:105–116. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9994-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tyson M., Covey J., Rosenthal H.E. Theory of planned behavior interventions for reducing heterosexual risk behaviors: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2014;33:1454–1467. doi: 10.1037/hea0000047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breiding M.J., Smith S.G., Basile K.C. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence victimization—National intimate partner and sexual violence survey, United States, 2011. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014;63:1–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sobecki J.N., Curlin F.A., Rasinski K.A. What we don't talk about when we don't talk about sex: Results of a national survey of U.S. obstetrician/gynecologists. J Sex Med. 2012;9:1285–1294. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02702.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golin C.E., Patel S., Tiller K. Start talking about risks: Development of a motivational interviewing-based safer sex program for people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:S72–S83. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9256-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]