Abstract

Objective: Evaluate effects of revised education classes on classroom engagement during inpatient rehabilitation for individuals with spinal cord injury/disease (SCI/D).

Design: Multiple-baseline, quasi-experimental design with video recorded engagement observations during conventional and revised education classes; visual and statistical analysis of difference in positive engagement responses observed in classes using each approach.

Participants/Setting: 81 patients (72% male, 73% white, mean age 36 SD 15.6) admitted for SCI/D inpatient rehabilitation in a non-profit rehabilitation hospital, who attended one or more of 33 care self-management education classes that were video recorded. All study activities were approved by the host facility institutional review board.

Intervention: Conventional nurse-led self-management classes were replaced with revised peer-led classes incorporating approaches to promote transformative learning. Revised classes were introduced across three subject areas in a step-wise fashion over 15 weeks.

Outcome Measure: Positive engagement responses (asking questions, participating in discussion, gesturing, raising hand, or otherwise noting approval) were documented from video recordings of 14 conventional and 19 revised education classes.

Results: Significantly higher average (per patient per class) positive engagement responses were observed in the revised compared to conventional classes (p=0.008).

Conclusion: Redesigning SCI inpatient rehabilitation care self-management classes to promote transformative learning increased patient engagement. Additional research is needed to examine longer term outcomes and replicability in other settings.

Keywords: Rehabilitation, Spinal cord injuries, Peer group, Education, Care self-management, Mentoring

Individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) face lifelong risks of potentially life-threatening secondary conditions (e.g., pressure injuries, urinary tract infections, respiratory problems). A major goal of rehabilitation is imparting the knowledge and skills needed for effective self-management of care needs to minimize these complications. Effective patient education in self-management of conditions associated with SCI is considered the standard of care.1–5

Despite the importance of patient education for effective self-management, rehabilitation providers struggle to find time (due to shorter lengths of stay) and effective teaching strategies to ensure patients are prepared. During the weeks after injury, many patients have not had time to adjust to the trauma and its consequences, either physically or emotionally. Under these circumstances, ability to retain knowledge and skills needed for effective self-management may be diminished.6 As a result patients and their families may leave the hospital feeling overwhelmed and unprepared to assume responsibility for personal care.

Many factors contribute to SCI patients’ difficulty in embracing the knowledge and skills needed for self-management during the rehabilitation process. A key issue is patients’ “readiness to learn,” which is influenced by pre-morbid factors (e.g., health literacy, capacity for critical thinking and problem-solving) and consequences of injury (e.g., medical complications, pain, depression).6 Transformative learning theory aids in understanding why patients may lack readiness to learn at this stage of recovery – they don't yet have the “mindset” to understand why new information is important. Transformative learning is the process by which adults change, or transform, how they think about their lives as they encounter major challenges, such as a traumatic injury.7 Through the process of transformation, adult learners critically examine the “disconnect” between existing beliefs and changes brought about by a life-altering event and subsequently transform their perspective.8 This in-depth personal change in perspective is necessary to regain meaning in life and is important to achieving a “new normal” life with SCI.9

The concept of self-efficacy –belief in one's ability to execute actions required to achieve desired outcomes – is another important concept in adult learning.10 It is especially applicable to learning new skills and has been shown to be a powerful mediator in self-management of chronic conditions.11 Self-efficacy can be enhanced through carefully designed instruction that promotes skill mastery, and includes modeling of desired behavior and social support for behavior change.10

Blended learning and the reverse classroom model are emerging instructional strategies that have relevance for transformative learning and promotion of self-efficacy. Blended learning strategies combine face-to-face education with asynchronous online learning, and can be more effective and efficient than traditional classroom instruction.12 The reverse classroom model involves “flipping” classroom and outside learning activities. At its most basic, students review material outside of class and class time is used for knowledge application. Class time is devoted to modeling and demonstration of new tasks with performance feedback, and problem-solving scenarios that involve application of new knowledge.

Peer support is a strong component of instruction to promote transformative learning. People learn more and try harder when they learn from people they perceive to be like themselves, managing circumstances like their own.11 Peer-led instruction provides an effective context for modeling because peers are seen as relevant to the learner. Fellow students can also serve as models for each other, seeing others like themselves solve problems. The best-researched self-efficacy enhancing intervention is the Stanford Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP) developed by Lorig and colleagues. Studies have demonstrated that CDSMP enhances self-efficacy in self-management tasks, thereby improving health outcomes.13–17

A recent study assessing readiness to learn for self-directed care in SCI patients identified engagement in class as a fundamental premise.18 It surmised that as patient engagement increases, readiness to learn also increases. Nurse assessment corroborated that greater patient engagement in self-care education is associated with fewer complications and hospital readmissions in the first year post injury.19 Students who are actively engaged in class have been reported to perform better then students who are less engaged.20, 21

This article presents results of a study that set out to determine if patient engagement in self-management education classes could be improved by incorporating several changes in class format and structure. We compared engagement in classes facilitated by a nurse educator using conventional, didactic instruction (i.e., PowerPoint lecture followed by question and answer period) to classes facilitated by a SCI peer that incorporated instructional strategies intended to promote transformative learning (blended learning approach; peer-facilitated discussion focused on problem-solving strategies around questions/concerns expressed by participants). We hypothesized that the revised, peer-led classes would improve participants’ engagement in class activities, compared to conventional, nurse-led classes.

Methods

Setting/Participants. The study was conducted in a free-standing, non-profit hospital specializing in medical rehabilitation of brain and spinal cord injury. Eligible participants included all patients admitted to the SCI inpatient rehabilitation program who attended patient self-care education classes over 15 weeks. The study was approved by the host facility's institutional review board.

Study Design. We used a multiple-baseline design, wherein the revised classes were introduced across three subject areas in step-wise fashion over successive weeks.22, 23 Commonly used in single-subject research, characteristics of this design include repeated baseline measurements and staggered introduction of the intervention across at least three behaviors (of a single participant), settings, or individuals. The multiple-baseline design can also be applied to groups of individuals or settings (such as classes) assuming the groups are independent, that is change in one group following introduction of an intervention does not carry over to other groups.24 The design controls for the effect of extraneous events (history) by showing that changes occur after and only after introduction of the intervention to each group.25 Data analysis of the design involves examining – visually and statistically – changes in the slope or level of the repeated measures taken before and after introduction of the intervention across each group. In this case, the classes for three subject areas – skin care, bladder management, and special concerns – were treated as groups. Over a 15-week period, the conventional classes for each of these subject areas were replaced with revised, peer-led classes. The order in which the revised classes were introduced across subject areas was determined randomly.

Study Comparators.Table 1 summarizes features of the self-care class redesign. For the conventional classes, nurse educators assigned patients to self-care education classes that occurred throughout the last 3 weeks of rehabilitation. Classes were presented in didactic formats with PowerPoint-aided lectures by the nurse followed by a question/answer period. Lectures reviewed basic anatomy and physiology, functional changes after SCI, and options for management of these changes. The lectures were supplemented with bed-side instruction by a nurse with the patient and/or caregiver in conjunction with specific care routines (e.g., intermittent catheterization).

Table 1. Patient self-care education class redesign.

| Conventional Classes | Peer-led Classes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leader: One of three nurse educators | Leader: Peer mentor with 15 years ‘experience’ living with SCI and trained by lead nurse educator | |||

| Approach: Didactic PowerPoint-directed lecture | Approach: Problem-solving discussions using mixed media | |||

| Time: One-hour class at either 11:00 or 3:30 any Monday-Thursday during last 3 weeks of rehabilitation (not all classes in same week; each class offered every other week) | Time: Patients scheduled for ‘education week,’ each class at 11:00-12:00: Monday - Skin Management, Tuesday - Bowel Management, Wednesday - Bladder Management, Thursday - Special Concerns | |||

| Class name | Content | Class name | Content | |

| Overview of SCI | [Eliminated] | Refer to educational website in each class | ||

| Bowel Management and Nutrition | Anatomy and Physiology (A&P) of gastrointestinal (GI) system**Physiologic effect of SCI on GI system**Options for bowel management**Common problems identified | Bowel Management and Nutrition**(trial class, not included in analyses) | Introductory video re bowel management after SCI, video vignettes of involuntary bowel movements, diarrhea, constipation, and healthy nutrition followed by problem solving discussions | |

| Bladder Management | A&P of urinary system**Physiologic effect of SCI on urinary system**Options for bladder management**Common problems | Bladder Management | Introductory video re bladder management after SCI. Red/yellow/green light activity to stratify UTI symptoms. Problem solving discussions. | |

| Skin Management and Pressure Injury Prevention | A&P of the integumentary system**Physiologic effect of SCI on integumentary system**Causes of issues**Prevention of skin issues | Skin Management and Pressure Injury Prevention | Introductory video re skin management after SCI. “What's wrong with this picture” activity. Problem solving discussions. | |

| Respiratory Management and Infection Control | A&P of respiratory system**Pneumonia: signs/symptoms, treatment, prevention. Importance of cleanliness, hand washing, minimizing germ exposure | Special Concerns + incorporated content of optional conventional classes | Jeopardy type game where participants select topic (respiratory, blood pressure, autonomic dysreflexia, spasms, blood clots) and answer questions within each to earn points for competition. Each content area also rolled into the other 3 classes | |

| Additional optional classes (30 minutes each) | ||||

| Spasticity and Prevention of Complications | A&P of spasticity**Advantages/disadvantages of spasms and treatments | |||

| Autonomic Dysreflexia | A&P of Autonomic Dysreflexia**Signs/symptoms/causes/treatment |

Conventional classes were consolidated into 4 revised classes; nurse educators had been concerned that patients were scheduled for too many classes, which competed with therapy schedules, and with the change in design, believed content could be covered adequately in 4 classes. During one of the last 3 weeks of the inpatient stay, educators scheduled patients to participate in ‘education week,’ consisting of four 1-hour classes offered Monday-Thursday. Three of the four classes were included in the study; the bowel management class was revised first and used as a trial of the revised approach.

One member of the peer support team led all redesigned classes; at least one additional peer attended each class to provide support and expand experiential knowledge available to class participants. The peer leader contributed 15 years of experience living with SCI and used his knowledge of relearning self-care function/needs to lead problem-solving discussions. A nurse educator was present in each class as a content expert to answer medical or health-related questions.

Class content shifted from a focus on physiology and functional changes after SCI to identifying and solving problems resulting from changes due to injury. Revised education materials were developed by nurse educators and peer mentors collaboratively to ensure that clinically appropriate content was included and presented in a way that related to patients in a “this is how we, as people with SCI, manage our self-care needs and associated conditions.” Patients were instructed to refer to the hospital's patient education website,26 which was referenced in every class, for comprehensive information regarding management of SCI. As with conventional classes, the revised classes were supplemented with bed-side instruction by a nurse in conjunction with specific care routines.

The revised classes incorporated a blended learning delivery approach with mixed media presentations followed by problem-solving discussions. Using a modified, “flipped-classroom” format, each class began with a brief (<3 minute) video depicting people with SCI identifying the topic to be discussed and providing options for self-management. Following the video, patients were asked if they wanted to discuss specific issues related to the topic. Next, an interactive activity, unique to each class, was done to further engage participants and encourage problem-solving strategies. We introduced the revised approach in step-wise fashion across three subject areas – skin management, bladder management, and respiratory/infection control (renamed special concerns as the focus broadened to include spasticity and autonomic dysreflexia) - over a 15-week period. Baseline measures were taken in the conventional classes before introduction of the revised classes for each of the three subject areas.

Data collection. A total of 33 classes (14 conventional and 19 revised) were video recorded over the study period. To record the classes, a nurse educator pushed the record button and mounted a GoPro camera on top of the projection screen in the classroom prior to the start of class. All patients attending class were included in the video recording. Twelve classes during the study period were not recorded successfully, either because the nurse educator forgot to initiate recording or the record function did not work properly. These omissions occurred at random across the course of the study.

Each video recording was reviewed independently by two observers who counted the number of positive engagement responses observed. Their counts were compared for accuracy and the videos independently re-reviewed to resolve any discrepancies, until 100% agreement was achieved both in the count of positive engagement responses and which patient made the response. Engagement responses included patients asking questions, participating in class discussion, and gesturing, raising hand, or otherwise noting agreement or disagreement with points being made in the discussion. For each class, the number of positive engagement responses was totaled and divided by the number of participants to determine the average number of positive engagement responses per class.

Given the staggered introduction of the revised classes, patients included in the video recordings may have attended only conventional classes (early in the study), only revised classes (later), or a mix of both formats. Patients who attended a mix of class formats were interviewed at the end of ‘education week’ to document their perceptions of which format (conventional or revised) helped strengthen their understanding of the topic and confidence in their ability to manage their care needs. Next, they were asked which class (skin, bladder, special concerns) was most informative (and why), and in which class they felt most engaged (and why). Responses were grouped into conventional and revised class categories.

Analysis. All patients observed in at least one video recording were included in the analyses. In addition to visual analysis, we used a randomization test to examine differences in engagement responses between conventional and revised classes for each of the three subject areas. We used the Koehler-Levin randomization test for multiple baseline designs,27 using the SCRT-R (Single-Case Randomization Test – R) program developed by Bulte and Ohghena28 for the R open-source statistical analysis package. The Koehler-Levin procedure involves calculating a test statistic (in this case, the average number of engagement responses per patient per class) for all possible intervention vs. baseline outcomes (derived from mathematical permutations). A complete randomization distribution is constructed based on all possible outcomes, and the location of the actual outcome within the distribution is noted along with its statistical probability (determined by the total number of permutations). We estimated effect size by calculating the percentage of non-overlapping data (PND) for each data series.29

Results

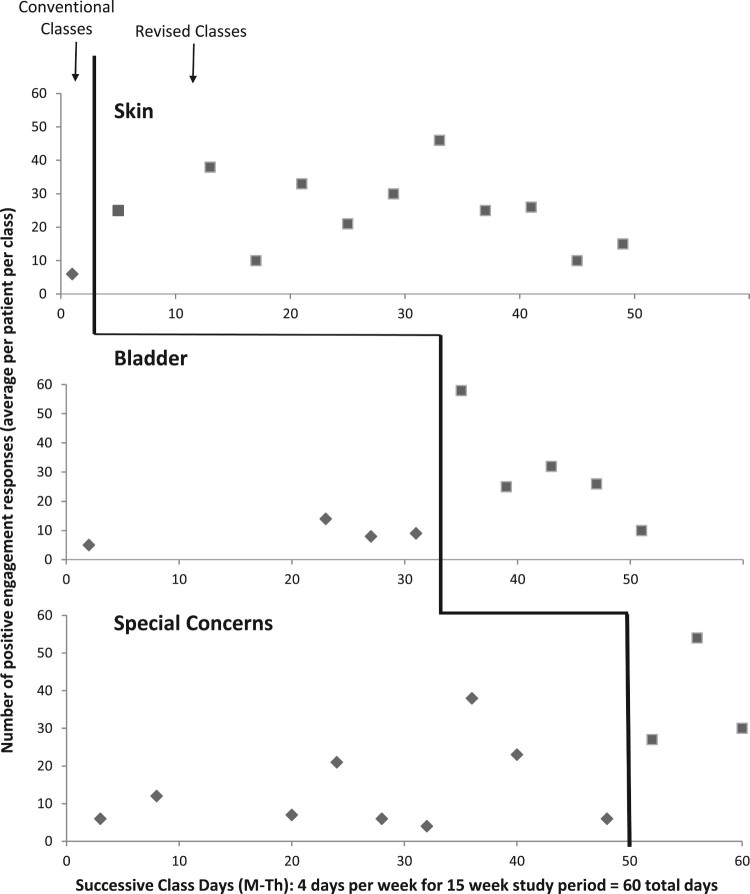

A total of 81 patients participated in one or more conventional or revised classes. Participant characteristics were 72% male, 73% Caucasian, with a mean age of 36 (SD = 15.6). Figure 1 presents visual analysis of the multiple baseline design. It depicts the classes, in each of three subject areas, in which observations of engagement were documented (plotted as the average number of engagement responses per patient per class) for conventional (diamonds) and revised (squares) classes. The solid black line indicates the point in time that each class format was changed. Immediate and dramatic increases in the number of positive engagement responses were noted with introduction of the revised class format, across all three subject areas.

Figure 1.

Multiple baseline implementation: Positive engagement responses (average per patient per class) by class type (conventional and revised) and topic (skin, bladder, special concerns)

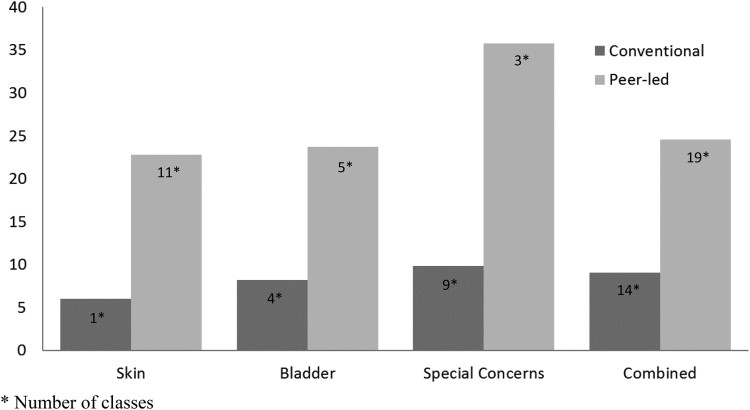

Figure 2 presents the average number of positive engagement responses (per patient per class) for classes in each subject area and all classes combined, during the 15-week study period. The randomization test revealed significantly higher counts of positive engagement responses in the revised compared to conventional classes (p = 0.008). We calculated PND at 84%, indicating a medium to large effect size based on published guidelines for PND.30

Figure 2.

Positive engagement observations (average per patient per class) by class type (conventional and revised) and topic (skin, bladder, special concerns).

p-value = 0.008 (Single-Case Randomization Test)

Interviews with 37 patients who participated in a mix of conventional and revised classes revealed that 87% of respondents believed the revised-format classes better strengthened their understanding of the topic and ability to solve problems related to their care needs; 8% preferred conventional classes, and 5% were not sure. Most patients (35 of 37 respondents) also found class topics delivered by peers to be more informative and more engaging than the conventional approach. Tables 2 and 3 groups patient responses for which class was most informative and in which class they felt more engaged in the learning process (separated by conventional and revised format).

Table 2. “Why did you find identified class(es) more informative?” (Selected Responses).

| Peer-Led Classes – total 35 responses |

|---|

| Because the teacher can empathize with me. |

| It touched me more by having my peers teach it than talking over slides. |

| There was more discussion. |

| Because it's better designed and not a PowerPoint. |

| Good video, instructor was able to get the class involved. |

| Due to [peer's] own experience and personal examples. Also, the videos were more show and tell. |

| Having a spinal cord injury [person] teach the class is easier to relate to. |

| They [peers} relate to me most and overall were more fun. I learned a lot about skin and it was most memorable |

| Conventional Classes – total 2 responses |

| Because it [respiratory] is most relevant to what I think I’ll deal with the most |

| Because it [respiratory] is the number one cause of death in quadriplegics |

Table 3. “Why do you feel you were more engaged in identified class(es)?” (Selected Responses).

| Peer-Led Classes – total 35 responses |

|---|

| Because it was more of an open forum. |

| I felt like it was more one on one and peer to peer. |

| Because they put you on the spot and talk to you instead of at you. |

| Because it encourages engagement. |

| Because there were two gentlemen who I could relate to. |

| [Peers] provided great examples of real-life scenarios. |

| Because of having someone I can relate to. |

| The overall set up of the information provided was more engaging. |

| Because the game forced me to. Class brought up a lot of things I hadn't thought of |

| Conventional Classes – total 0 responses |

| None of the classes – total 2 responses |

| No explanation provided |

Discussion

We observed immediate and sustained increases in patient engagement after introduction of the revised class format for each subject area. A randomization test confirmed that statistically significant improvements in engagement were associated with the revised class format. Participant feedback provided social validation of the observed improvements, indicating greater perceived benefit of the revised format for most participants.

It is important to note that the revised classes incorporated several changes intended to promote transformative learning, including peer-facilitation, blended learning, and the flipped classroom approach. Thus, observed improvements in patient engagement cannot be attributed to any single change and, in fact, all of the changes likely contributed. However, the value of engaging peers as educators is verified by several anecdotal findings. First, patients who participated in a mix of conventional and revised classes, voiced strong support for the value of learning from others who have “been there, done that.” Although the clinical expertise of nurse educators was clearly valued, many patients commented that hearing information from other people with SCI made the information more relatable.

Second, as patient education is an integral part of nursing practice,31 nurse educators were at first hesitant about using peers who were not trained professionally. However, nurse educators saw immediate differences in how patients were more engaged in class. This became obvious when the peer-led approach was first trialed in the bowel management class. Patients circled around the peer leader rather than lining up in front of the projector screen as they had done during conventional classes. Patients did not hurry to leave and discussions continued after class ended. During the bowel management class trial, patients would ask why peers were not leading other classes and their interest in attending other classes waned. By observing the revised process, nurses realized important clinical information could be woven into informal discussions led by peers. They observed patients beginning to reflect personal relevance and becoming more participatory in class activities. These observations, along with data demonstrating greater patient engagement, convinced nurse educators that peer-led education can be effective, and they have become strong advocates for this approach.

Findings of greater engagement in peer-led classes confirm findings by Lorig and colleagues with the CDSMP.13–17 People relate better to people they perceive to be like themselves managing circumstances like their own. Peers were able to ‘joke’ about personal experiences, putting patients at ease and prompting self-reflection. While patients were sometimes reluctant to talk about personal issues, when a peer related a humorous personal story, patients became more willing to discuss their concerns. Although humor can be a useful tool to increase engagement, it must be used carefully so that it is not interpreted as rude or uncaring.32

A fourth justification for the involvement of peers in supporting patients’ self-management education is philosophical but also relevant to community reintegration after rehabilitation and broader health policy issues. Peers helping peers and “nothing about us without us” are long-standing, fundamental tenets of the independent living movement, so much so that peer support is one of the mandated core services of centers for independent living.33 Peer support extends beyond support for healthcare to all aspects of community reintegration and resuming a “new normal” life after SCI. From a health policy perspective, peer support contributes to greater consumer autonomy and control over health outcomes. It is a cornerstone of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, designed to improve care transitions, reduce unplanned readmissions, and better coordinate post-discharge services.34–36 This may also reduce reliance on the healthcare system and ultimately lower healthcare costs, as consumers find more convenient access to support from peers for health and wellness endeavors. The important role of peers as change agents in recovery is increasingly being recognized as the standard of care, as evidenced by recent revisions of the CARF accreditation standards.37 We believe the results presented here lend support for this emerging standard of care.

Finally, we hypothesized that increased patient engagement in self-care education classes would contribute to better self-management and improved longer-term health outcomes. While beyond the scope of the present study, future research should examine these relationships to validate the importance of patient engagement. Future research should also attempt to isolate the role of peers as change agents in patient education (for example, comparing effects of the same educational program delivered by peers vs. nurse educators), and examine implementation across multiple sites to determine scalability and setting events that are important to successful replication.

Limitations

Several methodological limitations should be acknowledged. First, the original implementation timeline for our multiple baseline design was altered to accommodate patient and educator demand. The revised class format trialed in the bowel management class was so popular with patients and differences in engagement so obvious, we conceded to organizational pressure to implement the new class format as soon as possible. The decision to implement sooner, combined with recording malfunctions, resulted in obtaining only one baseline measure of patient engagement for skin classes before the revised format was implemented. Fortunately, effects of the revised class format clearly exceeded the baseline collected during the conventional skin class.

Second, our approach to video recording resulted in no recordings for 12 (27%) of the 45 classes conducted during the study period. Mounting the camera on top of the projection screen, although preferable from a viewing standpoint, made it impractical to reach the camera to resolve recording issues during class. Even though not all classes were recorded, those missing were at random with respect to type (conventional vs. revised format) and subject matter. Thus, the captured recordings were representative of all classes conducted.

Third, we cannot claim use of a validated engagement measurement tool. However, to identify constructs of positive engagement, we consulted with nurse educators about the behaviors they consider indicative of active engagement in class. The criteria they identified as ‘positive’ were similar to the highest rated student behaviors on the In-class Engagement Measure (IEM),38 an observation tool to record details of the learning environment and student behaviors. Moreover, direct observation of student behavior, with adequate checks on inter-observer reliability (as employed here), is accepted practice in studies of classroom behavior.

Another limitation, which may influence generalizability of study findings, pertains to the culture of the organization in which this research was conducted. The importance of a culture that endorses peer mentors as part of the rehabilitation team cannot be overstated. When clinicians observed the impact of peers on patient engagement, inside the classroom but also in other aspects of rehabilitation, they became advocates of the process. Other organizations may have a culture that is less conducive to peer involvement. However, it is important to note that even in the setting for this research – an organization with a strong reputation for patient-centered care – there was initial reluctance for peers assuming anything other than a social support role. A substantial contribution of the work presented here is its impact in winning over initially skeptical clinicians and solidifying the role of peers in the rehabilitation process.

Conclusion

Education strategies that promote transformative learning and include peers as educators increase patient engagement in self-management education. Additional research is needed to isolate the contributions of peers to engagement improvements. Research should also examine the relationship between improved engagement, self-efficacy in care management, and long term health outcomes (reduced hospital readmissions), as well as replicability in other settings.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award # IH-12-11-5106 and the Robert W. Woodruff Foundation.

Acknowledgement

All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the PCORI, its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee, or of the Robert W. Woodruff Foundation.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors None.

Declaration of interest None.

Conflicts of interest None.

Ethics approval None.

References

- 1.Emerich L, Parsons K, Stein A.. Competent care for persons with spinal cord injury and dysfunction in acute inpatient rehabilitation. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehab. 2012;18(2):149–66. doi: 10.1310/sci1802-149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine Bladder management for adults with spinal cord injury: A clinical practice guideline Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America; 2006. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine Neurogenic bowel management in adults with spinal cord injury: A clinical practice guideline for health-care professionals. Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine Respiratory management following spinal cord injury: A clinical practice guideline for health-care professionals. Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine Pressure ulcer prevention and treatment following spinal cord injury: A clinical practice guideline for health-care professionals Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Wyk K, Backwell A, Townson A.. A narrative literature review to direct spinal cord injury patient education programming. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehab. 2015;21(1):499–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mezirow J.Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubouloz C, King J, Ashe B, Paterson B, Chevrier J, Moldoveanu M.. The process of transformation in rehabilitation: What does it look like? International J Therapy and Rehab. 2010;17(11):604–13. doi: 10.12968/ijtr.2010.17.11.79541 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barclay-Goddard R, King J, Dubouloz C, Schwartz C.. Building on transformative learning and response shift theory to investigate health-related quality of life changes over time in individuals with chronic health conditions and disability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(2):214–20. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bandura A.Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lorig K, Gonzalez V.. The integration of theory with practice: a twelve year case study. Health Educ Quarterly. 1992;19(3):355–68. doi: 10.1177/109019819201900307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garrison D, Kanuka H.. Blended learning: Uncovering its transformative potential in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education. 2004;7:95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2004.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lorig KR, Ritter P, Stewart AL, Sobel DS, Brown BW Jr, Bandura A, et al.. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Med Care. 2001;39(11):1217–23. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200111000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Stewart AL, Brown BW Jr, Bandura A, Ritter P, et al. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: A randomized trial. Med Care. 1999;37(1):5–14. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199901000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffiths C, Motlib J, Azad A, Ramsay J, Eldridge S, Feder G, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a lay-led self-management program for Bangladeshi patients with chronic disease. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(520):831–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy A, Reeves D, Bower P, Lee V, Middleton E, Richardson G, et al. The effectiveness and cost effectiveness of a national lay-led self care support programme for patients with long term conditions: A pragmatic randomized controlled trial. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:254–61. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.053538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jerant A, Moore M, Lorig K, Franks P.. Perceived control moderated the self-efficacy-enhancing effects of a chronic illness self-management intervention. Chronic Illn. 2008;4(3):173–82. doi: 10.1177/1742395308089057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olinzock B.A model for assessing learning readiness for self-direction of care in individuals with spinal cord injuries: A qualitative study. SCI Nurs. 2004;21(2):69074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bailey J, Dijkers MP, Gassaway J, Thomas J, Lingefelt P, Kreider SED, et al Relationship of nursing education and care management inpatient rehabilitation interventions and patient characteristics to outcomes following spinal cord injury rehabilitation: The SCIRehab project. J Spinal Cord Med. 2012;35(6):593–610. doi: 10.1179/2045772312Y.0000000067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis S, Freed R, Heller N, Burch G.. Does student engagement affect learning? An empirical investigation of student involvement theory. Academy Business Research Journal. 2015;2:8–16. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonet G, Walters B.. High impact practices: Student engagement and retention. College Student Journal. 2016;50(2):224–35. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baer D, Wolf M, Risley T.. Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. J Applied Behav Analysis. 1968;1(1):91–7. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith J.Single-case experimental designs: A systematic review of published research and current standards. Psychol Methods. 2012;17(4):510–50. doi: 10.1037/a0029312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kazdin A, Kopel S.. On resolving ambiguities of the multiple baseline design: Problems and recommendations. Behavior Therapy. 1975;6(5):601–8. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(75)80181-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawkins N, Sanson-Fisher R, Shakeshift A, D’Este C, Green L.. The multiple baseline design for evaluating population-based research. Amer J Preventive Med. 2007;33(2):162–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shepherd Center myShepherdConnection.org. Available from http://www.myshepherdconnection.org/sci. Accessed March 3, 2017.

- 27.Koehler M, Levin J.. Regulated randomization: A potentially sharper analytic tool for the multiple-baseline design. Psych Methods. 1998;3(2):206–17. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.3.2.206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bulte I, Onghena P.. Randomization tests for multiple-baseline designs: An extension of the SCRT-R package. Behavior Research Methods. 2009;41(2):477–85. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.2.477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parker R, Vannest K, Davis J.. Effect size in single-case research: A review of nine nonoverlap techniques. Behavior Modification. 2011;35(4):1–20. doi: 10.1177/0145445511399147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scruggs T, Mastropieri M.. Summarizing single-subject research: Issues and applications. Behavior Modification. 1998;22:221–42. doi: 10.1177/01454455980223001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Advisory Council on Nurse Education and Practice Addressing new challenges facing nursing education: Solutions for a transforming healthcare environment. Eighth Annual Report to the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Congress. Rockville, MD: Health Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poirier T, Wilhelm T.. Use of humor to enhance learning: Bull’s eye or off the mark. Amer J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(2):Article 27. doi: 10.5688/ajpe78227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore M, Terrell S, Joyce L.. What does person-centered planning mean for the IL paradigm? Paper presented at: National Council on Independent Living. Washington, DC; 2014.

- 34.Naylor M, Aiken L, Kurtzman E, Olds D, Hirschman K.. The Importance of transitional care in achieving health reform. Health Affairs. 2011;30(4):746–54. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steinbrook R.Health care and the American recovery and reinvestment act. New Engl J Med. 2009;360:1057–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0900665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Index for Excerpt from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 ; 2009. Available from https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/hitech_act_excerpt_from_arra_with_index.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2017.

- 37.CARF International Medical Rehabilitation Standards. Tucson, AZ: Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alimoglu M, Sarac D, Alparslan D, Karakas A, Altintas L.. An observation tool for instructor and student behaviors to measure in-class learner engagement: a validation study. Med Educ Online. 2014;19:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]