Abstract

Using P25 as the titanium source and based on a hydrothermal route, we have synthesized CaTiO3 nanocuboids (NCs) with the width of 0.3–0.5 μm and length of 0.8–1.1 μm, and systematically investigated their growth process. Au nanoparticles (NPs) of 3–7 nm in size were assembled on the surface of CaTiO3 NCs via a photocatalytic reduction method to achieve excellent Au@CaTiO3 composite photocatalysts. Various techniques were used to characterize the as-prepared samples, including X-ray powder diffraction (XRD), scanning/transmission electron microscopy (SEM/TEM), diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (UV-vis DRS), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Rhodamine B (RhB) in aqueous solution was chosen as the model pollutant to assess the photocatalytic performance of the samples separately under simulated-sunlight, ultraviolet (UV) and visible-light irradiation. Under irradiation of all kinds of light sources, the Au@CaTiO3 composites, particularly the 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 composite, exhibit greatly enhanced photocatalytic performance when compared with bare CaTiO3 NCs. The main roles of Au NPs in the enhanced photocatalytic mechanism of the Au@CaTiO3 composites manifest in the following aspects: (1) Au NPs act as excellent electron sinks to capture the photoexcited electrons in CaTiO3, thus leading to an efficient separation of photoexcited electron/hole pairs in CaTiO3; (2) the electromagnetic field caused by localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) of Au NPs could facilitate the generation and separation of electron/hole pairs in CaTiO3; and (3) the LSPR-induced electrons in Au NPs could take part in the photocatalytic reactions.

Keywords: CaTiO3 nanocuboids, Au nanoparticles, localized surface plasmon resonance, Au@CaTiO3 composite, photocatalytic performance

1. Introduction

The rapid social development has raised two big issues facing mankind, i.e., environmental pollution and energy shortage. In particular, water resources are seriously and increasingly becoming polluted by the wastewater discharged from chemical industries, which poses a great threat to human health and survival. Organic dyes and pigments, most commonly existing in the industrial wastewater, are carcinogenic to humans and hardly self-decomposed [1,2]. It is imperative to remove the organic pollutants and purify water resources via a simple, low-cost, green and non-fossil-consumptive technology. In this sense, semiconductor-based photocatalysis has sparked a great interest due to its potential applications in wastewater treatment [3,4,5,6,7,8]. This technology allows the use of solar light—a sustainable, inexhaustible and economically attractive energy source—as the power source to degrade organic pollutants. The photocatalytic process depends highly on photogenerated electrons (e−) and holes (h+) in semiconductor photocatalysts, as well as their reduction and oxidation capabilities. Nevertheless, the photoexcited e−/h+ pairs are easily to be recombined and only a few of them are available for the photocatalytic reactions. To achieve an excellent semiconductor photocatalyst, the photoexcited e−/h+ pairs must be efficiently separated. As an important class of photocatalysts, titanium-contained oxide semiconductors can be photocatalytically active only under ultraviolet (UV) irradiation owing to their wide bandgap (Eg = 3.1–3.3 eV) [9,10,11,12,13]. It is noted that solar radiation includes only a small portion of UV light (~5%), but a large amount of visible light (45%). Enhancing the visible-light absorption of photocatalysts is the key point to make the best use of solar energy to drive the photocatalysis. Up to now, various strategies have been widely applied to modify semiconductor photocatalysts with the aim of facilitating the photoexcited e−/h+ pair separation and widening their light absorption range [14,15,16,17,18,19,20].

Zero-dimensional, one-dimensional and two-dimensional nanomaterials (e.g., metal nanoparticles (NPs), carbon quantum dots, carbon nanotubes, graphene) have attracted a great deal of interest due to their interesting physicochemical characteristics and great potential applications in the fields of bioimaging, energy conversion, optoelectronic devices, wave absorption and sensors [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Furthermore, these nanomaterials can be used as excellent modifiers or co-catalysts and are widely coupled with semiconductors to improve their photocatalytic performances [34,35,36,37,38]. Noble metal NPs are particularly interesting as the co-catalysts because they can not only facilitate the photoexcited e−/h+ pair separation but also enhance visible-light absorption. The enhanced photocatalytic mechanisms by noble metal NPs can be ascribed to two aspects [39,40]. First, noble metal NPs can act as electron sinks to trap photogenerated electrons from the semiconductor, thus leading to an efficient separation of e−/h+ pairs. Second, noble metal NPs can absorb visible light to induce localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) [41,42]. The LSPR-caused electromagnetic field could facilitate the generation and separation of e−/h+ pairs in the semiconductor. Simultaneously, LSPR-induced electrons in noble metal NPs could also take part in the photocatalytic reactions. Due to these unique properties, much work has demonstrated that noble metal NPs decorated semiconductors manifest significantly enhanced photocatalytic performances when compared with bare semiconductors [15,38,39,40].

Calcium titanate (CaTiO3), a typical titanium-contained oxide semiconductor with a perovskite-type structure, has sparked a great interest among researchers owing to its promising properties of ferroelectricity, piezoelectricity, elasticity, and photocatalytic activity [43,44,45,46,47]. As a photocatalyst, CaTiO3 has been shown to exhibit a pronounced photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants, as well as photocatalytic splitting of water into hydrogen and oxygen [48,49,50,51,52]. Semiconductor-based photocatalysis, intrinsically being a heterogeneous surface catalytic reaction, is highly dependent on the crystal morphology of the semiconductor. In particular, an excellent photocatalytic activity could be achieved for the semiconductor with special exposed facets [53,54]. In our previous studies, we have demonstrated that CaTiO3 nanocuboids (NCs) with (101) and (010) exposed facets exhibit a photocatalytic activity superior to that of sphere-like CaTiO3 nanoparticles [55]. In this work, we have assembled Au NPs on the surface of CaTiO3 NCs and found that the obtained Au@CaTiO3 composites exhibit much enhanced photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes under both UV and visible light irradiation. Compared to Ag NPs, Au NPs offer an advantage of higher chemical stability. However, there is no work concerned with the Au NPs modified CaTiO3 photocatalysts, though Ag NPs have been frequently used as a co-catalyst to improve the photocatalytic performance of CaTiO3 [56,57,58]. Here we also systematically investigated the growth process of CaTiO3 photocatalysts. The photocatalytic mechanism of the Au@CaTiO3 composites were systematically investigated and discussed. The present Au@CaTiO3 nanocomposite photocatalysts can be introduced in micro/nano photocatalytic devices for the wastewater treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of CaTiO3 NCs

CaTiO3 NCs were synthesized via a hydrothermal route at 200 °C as described in the literature [55]. To unveil the growth process of CaTiO3 NCs, different hydrothermal reaction times (0.5, 1, 5, 10 and 24 h) were performed.

2.2. Assembly of Au NPs on CaTiO3 NCs

A photocatalytic reduction method was employed to hybridize Au NPs on the surface of CaTiO3 NCs synthesized at 200 °C for 24 h. 0.1 g of the as-synthesized CaTiO3 NCs and 0.025 g of ammonium oxalate (AO) were successively added in 80 mL of deionized water. The suspension was ultrasonically treated for 30 min and then magnetically stirred for another 30 min to make CaTiO3 particles uniformly disperse. 0.8 mL of HAuCl4 solution (0.029 mol·L−1, M) was dropped in the CaTiO3 suspension. The resultant mixture was magnetically stirred for 60 min, and then irradiated with ultraviolet (UV) light, which was emitted from a 15 W low-pressure mercury lamp, for 30 min under mild stirring. During the irradiation process, Au3+ ions were reduced by the photogenerated electrons in CaTiO3 to form Au NPs, which were simultaneously assembled on the surface of CaTiO3 NCs. The product was collected by centrifugation. After washing several times with deionized water and ethanol, and then drying at 60 °C for 12 h, the final product was obtained as the 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 composite with an Au mass fraction of 4.3%. By adding different volumes of HAuCl4 solution (0.2, 0.5, 1.1 and 1.4 mL), several other composite samples 1.1%Au@CaTiO3, 2.7%Au@CaTiO3, 5.9%Au@CaTiO3 and 7.4%Au@CaTiO3 were also prepared.

2.3. Sample Characterization

The crystal structures, morphologies and microstructures of the samples were characterized by X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) and scanning/transmission electron microscopy (SEM/TEM). The used apparatuses were a D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer (Bruker AXS, Karlsruhe, Germany), a JSM-6701F field-emission scanning electron microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and a JEM-1200EX field-emission transmission electron microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). A PHI-5702 multi-functional X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (Physical Electronics, hanhassen, MN, USA) was employed for the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis. Ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) measurements were performed on a TU-1901 double beam UV-vis spectrophotometer (Beijing Purkinje General Instrument Co. Ltd., Beijing, China). A Spectrum Two Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) was used for the FTIR spectroscopy analysis of the samples.

2.4. Photocatalytic Test

To assess the photocatalytic performances of the samples, RhB in aqueous solution (5 mg·L−1) was used as the model pollutant. Simulated sunlight (emitted from a 200 W xenon lamp, 300 < λ < 2500 nm), UV light (emitted from a 30 W low-pressure mercury lamp, λ = 254 nm) and visible light (generated by a 200 W halogen-tungsten lamp, λ > 400 nm) were separately used as the light source. The reaction solution was composed of 100 mL of RhB solution and 0.1 g of the photocatalyst. The adsorption of RhB on the photocatalyst surface was examined by magnetically stirring the mixture in the dark for 30 min. The RhB concentration was monitored by measuring the absorbance of the reaction solution. 2.5 mL of the reaction solution was sampled from the photoreactor and centrifuged to remove the photocatalyst. The absorbance measurement was performed on a UV-vis spectrophotometer at λ = 554 nm. The percentage degradation of RhB (D%) was obtained according to D% = (C0 − Ct)/C0 × 100% (C0 = initial RhB concentration; Ct = residual RhB concentration).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis and Growth Process of CaTiO3 NCs

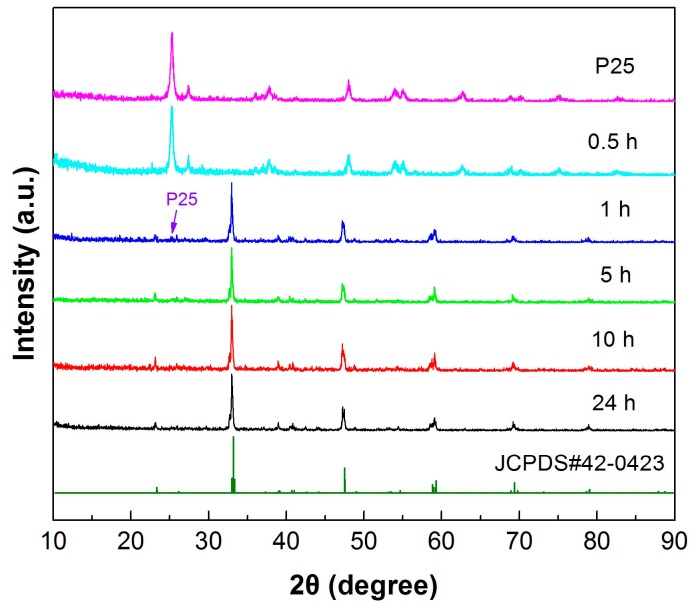

The crystal structures of precursor P25 and the samples prepared at 200 °C with different reaction times (0.5, 1, 5, 10 and 24 h) were determined by XRD patterns, as shown in Figure 1. It is seen that at 0.5 h reaction time, the obtained sample maintains a crystal structure identical to that of P25 without the formation of CaTiO3 phase. At 1 h reaction time, CaTiO3 phase is largely crystallized and only minor TiO2 is observed in the resultant sample. When the reaction time is increased up to 5 h, single CaTiO3 phase is obtained. All the diffraction peaks of the sample can be indexed to the CaTiO3 orthorhombic phase (JCPDS#42-0423). With further prolonging the reaction time, the diffraction peaks of the resultant samples undergo no change, indicating no structural change of CaTiO3 crystals.

Figure 1.

X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) patterns of precursor P25 and the samples prepared at 200 °C with different reaction times (0.5, 1, 5, 10 and 24 h).

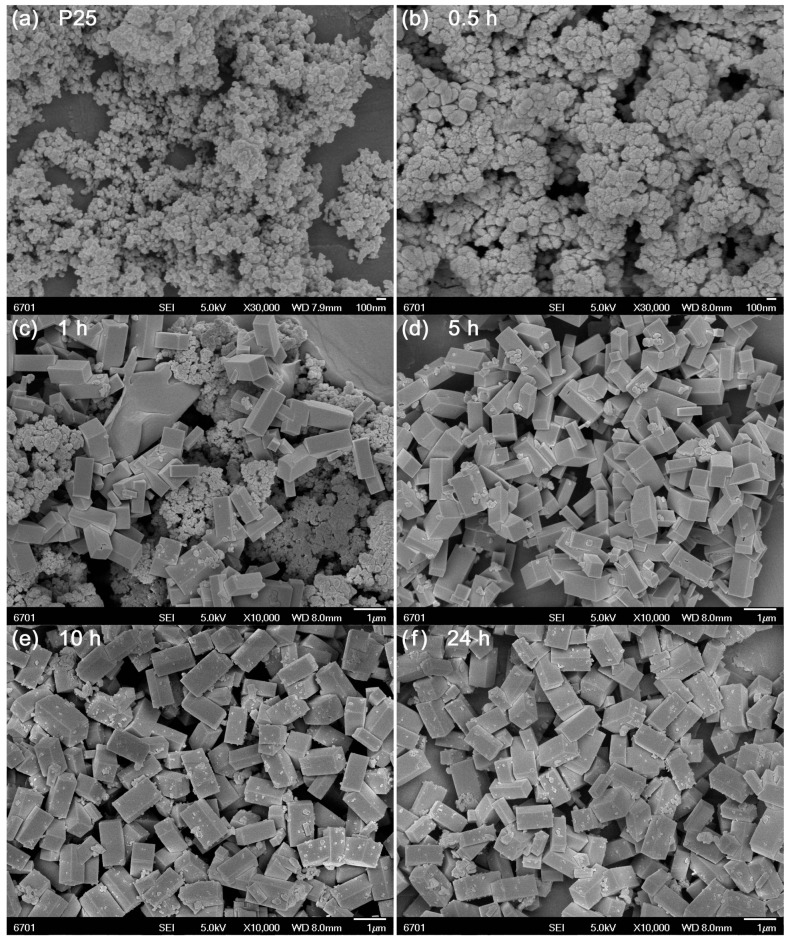

Figure 2 illustrates the SEM images of precursor P25 and the samples prepared at different reaction times. It is seen that P25 is composed of sphere-like nanoparticles with average size of 25 nm (Figure 2a). At 0.5 h of reaction, the TiO2 nanoparticles undergo almost no change, as shown in Figure 2b. The sample derived at 1 h reaction time mainly consists of cuboid-like particles together with minor sphere-like nanoparticles (Figure 2c), indicating that most of TiO2 nanoparticles are coupled with Ca species to form CaTiO3 NCs. With increasing the reaction time up to 5 h, TiO2 nanoparticles disappear and single CaTiO3 NCs are formed, as depicted in Figure 2d. These CaTiO3 NCs have a size of 0.3–0.5 μm in width and 0.8–1.1 μm in length. Further prolonging the reaction time up to 10 h (Figure 2e) and 24 h (Figure 2f) leads to no obvious morphological change of CaTiO3 NCs.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of (a) precursor P25 and the samples prepared at (b) 0.5, (c) 1, (d) 5, (e) 10 and (f) 24 h.

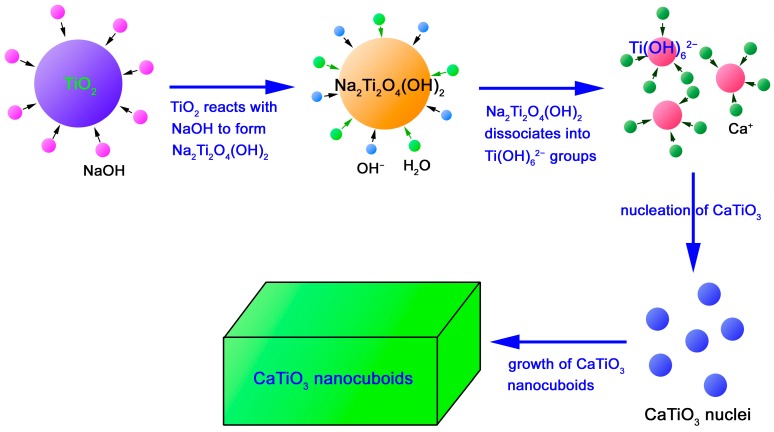

The growth process and mechanism of CaTiO3 NCs is schematically illustrated in Figure 3. In the concentrated NaOH solution, polycrystalline TiO2 nanoparticles are expected to react with NaOH to form Na2Ti2O4(OH)2 particles [59]. Simultaneously, in the strong alkaline environment and high temperature-high pressure conditions, Na2Ti2O4(OH)2 dissociates to form Ti(OH)62− ion groups [60]. Ca2+ ions in the precursor solution are adsorbed onto the surface of Ti(OH)62− ions and further penetrate into the interior. During this process, a series of chemical reactions will take place, including the breaking of Ti-O-Ti bonds, dehydroxylation and nucleation of CaTiO3 crystals. To reduce the overall surface energy, the nucleated CaTiO3 crystals grow into nanocuboids finally. The dominant chemical reactions involved can be briefly described as follows:

| 2NaOH + 2TiO2 → Na2Ti2O4(OH)2 | (1) |

| Na2Ti2O4(OH)2 + 2OH− + 4H2O → 2Ti(OH)62− + 2Na+ | (2) |

| Ca2+ + Ti(OH)62− → CaTiO3 + 3H2O | (3) |

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of the growth process and mechanism of CaTiO3 NCs.

3.2. Au NPs Modified CaTiO3 NCs

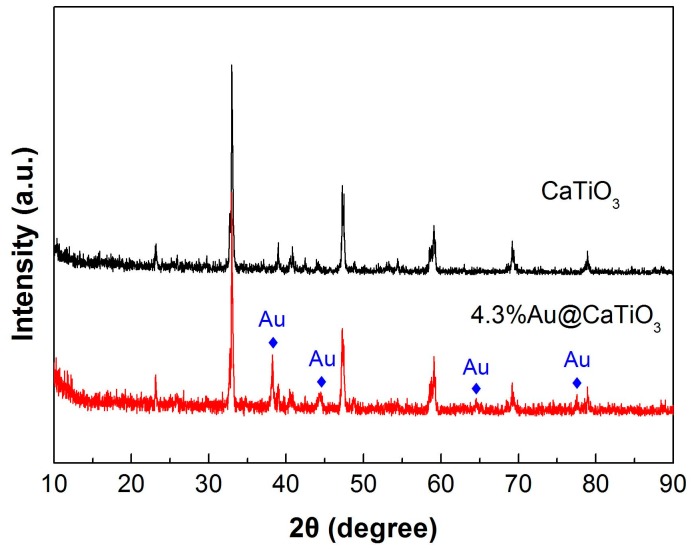

CaTiO3 NCs synthesized at 200 °C for 24 h was chosen to be modified with Au NPs with the aim of enhancing their photocatalytic performance. Figure 4 shows the XRD patterns of bare CaTiO3 NCs and 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 composite. The dominant diffraction peaks of 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 are similar to those of bare CaTiO3, indicating that the CaTiO3 orthorhombic structure undergoes no change on the decoration of Au NPs. However, additional weak diffraction peaks characterized as the Au cubic structure (JCPDS#04-0784) are clearly detected on the XRD pattern of the composite, which confirms the formation of Au NPs onto CaTiO3 NCs.

Figure 4.

XRD patterns of bare CaTiO3 NCs and the 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 composite.

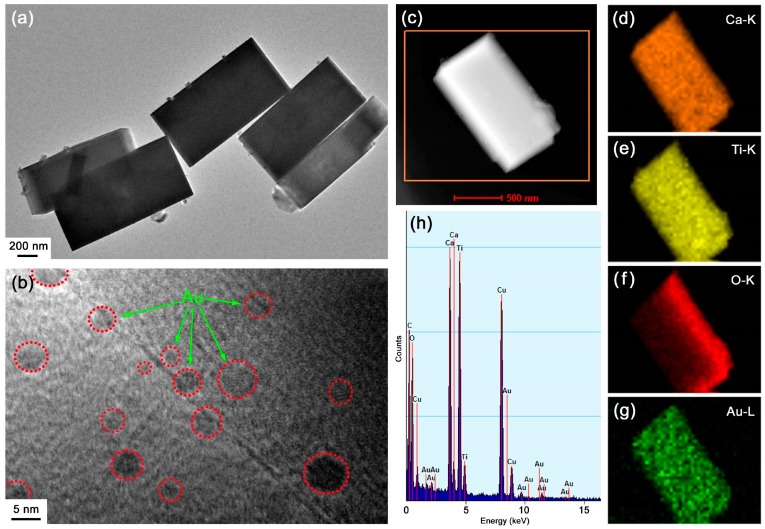

TEM investigation was further carried out to unveil the microstructure of the 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 composite. Figure 5a shows the TEM image of the composite, from which one can see that CaTiO3 presents a regular morphology of NCs with width of 0.3–0.5 μm and length of 0.8–1.1 μm. The CaTiO3 morphology obtained by TEM is in accordance with the SEM observation result. Moreover, small-sized Au NPs are seen to be decorated on the surface of CaTiO3 NCs. The high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image depicted in Figure 5b further confirms the good assembly of Au NPs on the surface of CaTiO3 NCs. The decorated Au NPs are shaped like spheres and have a size distribution of 3–7 nm. Energy-dispersive x-ray elemental mapping was used to investigate the elemental distribution of the 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 composite. Figure 5c illustrates the dark-field scanning TEM (DF-STEM) image of the composite, and the corresponding elemental mapping images are given in Figure 5d–g. It is observed that the NCs present uniformly-distributed elements of Ca, Ti and O. Moreover, Au element is also seen to be uniformly distributed throughout the NCs, indicating that CaTiO3 NCs are uniformly decorated with Au NPs. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) spectrum was further used to examine the chemical composition of the 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 composite. As shown in Figure 5h, the composite sample is composed of Ca, Ti, O, and Au elements. Additional Cu and C signals detected on the EDS spectrum could come from the TEM microgrid holder [61]. The obtained Au content from the EDS spectrum is 4.1%, which is basically in agreement with the stoichiometric composition of the 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 composite.

Figure 5.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image (a), HRTEM image (b), DF-STEM image (c), elemental mapping images (d–g), and EDS spectrum (h) of the 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 composite.

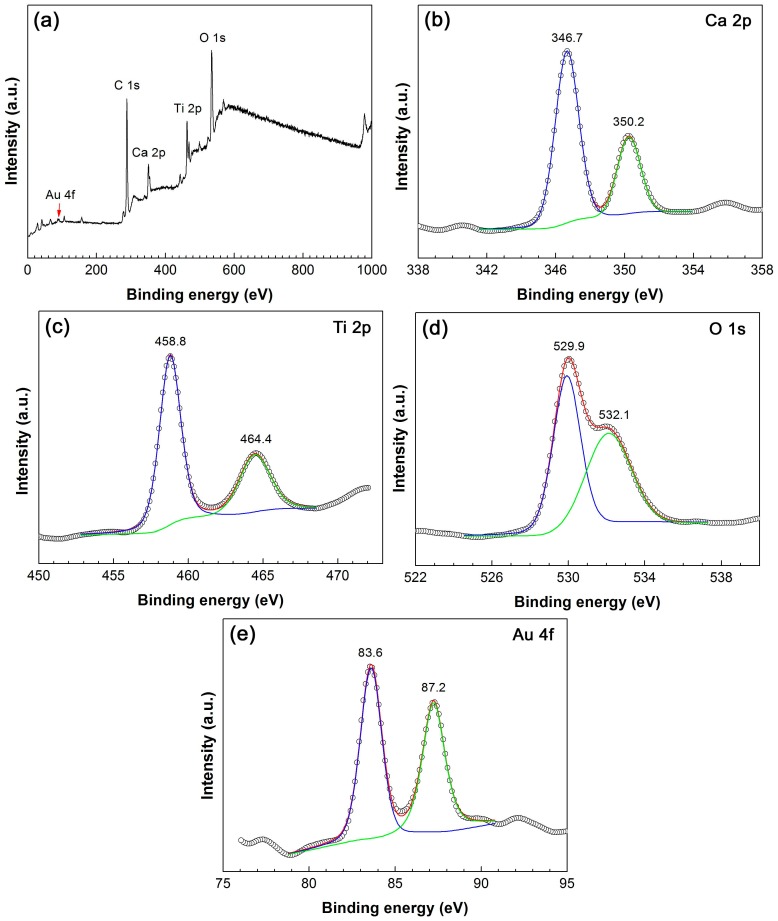

The XPS analyses were performed on 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 to elucidate the chemical states of elements. Figure 6a shows the survey XPS spectrum, revealing that the composite is composed of the elements Ca, Ti, O and Au. The observed C signal comes from adventitious carbon, which is used for the calibration of binding energy (C 1s binding energy: 284.8 eV). On the high-resolution XPS spectrum of Ca 2p core level (Figure 6b), the observed peaks at 346.7 and 350.2 eV account for Ca 2p3/2 and Ca 2p1/2, respectively. On the Ti 2p XPS spectrum (Figure 6c), the Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2 binding energies are observed at 458.8 and 464.4 eV, respectively. The binding energy positions suggest that the Ca and Ti species behave as Ca2+ and Ti4+ oxidation states, respectively [13]. Two peaks at 529.9 and 532.1 eV are detected on the O 1s XPS spectrum (Figure 6d), which are assigned to the crystal lattice oxygen in CaTiO3 and chemisorbed oxygen species [13,62]. On the Au 4f XPS spectrum (Figure 6e), the peak at 83.6 is attributed to Au 4f7/2 and the peak at 87.2 eV corresponds to Au 4f5/2. This implies the Au species exists in the metallic state [63].

Figure 6.

XPS survey scan spectrum (a), and high-resolution XPS spectra of (b) Ca 2p, (c) Ti 2p, (d) O 1s and (e) Au 4f of the 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 composite.

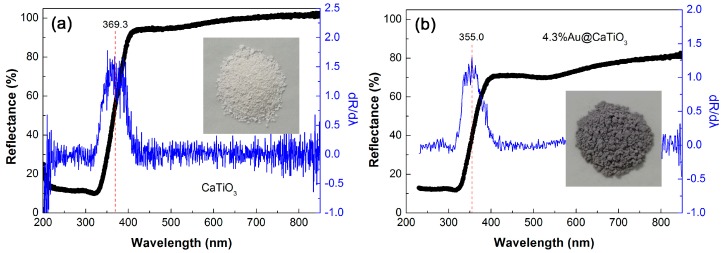

Figure 7a,b depict the UV-vis DRS spectra of CaTiO3 and 4.3%Au@CaTiO3, respectively, along with the corresponding first derivative curves of the UV-vis DRS spectra and the digital images of the samples (insets). It is seen that the decoration of Au NPs onto CaTiO3 NCs obviously enhances the visible-light absorption. This is further confirmed by the deepening of the apparent color for the 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 composite (dark gray), as compared to bare CaTiO3 NCs (cream white). The enhanced visible-light absorption implies that the Au@CaTiO3 composite photocatalyst can utilize photons more effectively. From the first derivative spectra, the absorption edge of CaTiO3 and 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 is obtained as 369.3 and 355.0 nm, respectively [64]. This suggests that bare CaTiO3 has a bandgap energy (Eg) of 3.36 eV and 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 exhibits an Eg of 3.49 eV. The slight increase in the Eg of the composite could be due to the interaction between CaTiO3 NCs and Au NPs.

Figure 7.

UV-vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) spectra, first derivative curves of the UV-vis DRS spectra and digital images (insets) of (a) CaTiO3 and (b) 4.3%Au@CaTiO3.

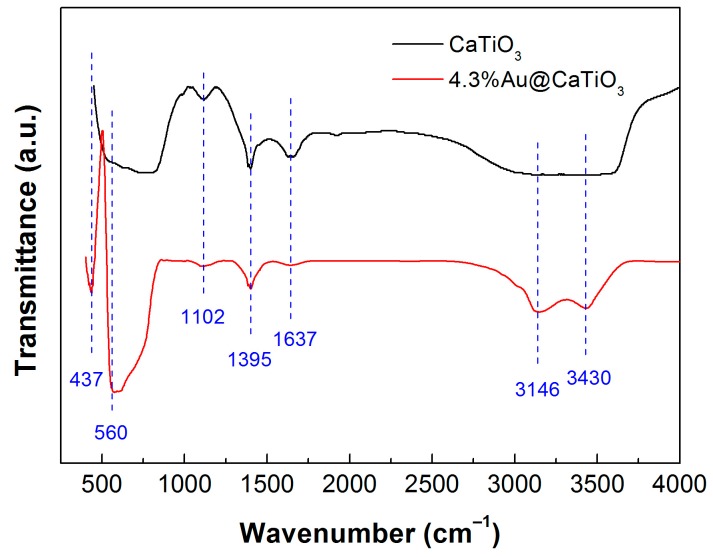

We measured the FTIR spectra of CaTiO3 and 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 to elucidate their functional groups, as shown in Figure 8. The absorption peaks at 437 and 560 cm−1 are characterized as the Ti–O stretching vibration and Ti–O–Ti bridging stretching mode [65,66]. This implies the existence of TiO6 octahedra and the formation of CaTiO3 perovskite-type structure. The observed broad bands at 3430 (H2O stretching vibration) and 1637 cm−1 (H2O bending vibration) suggest the presence of water molecules absorbed on the surface of the samples [67]. The presence of NH3+ group can be confirmed by the N–H stretching vibration located at around 3146 cm−1 [68]. The peaks detected at 1395 and 1102 cm−1 are attributed to the O–H in-plane deformation and C–OH stretching vibrations of alcohols [34]. This indicates that alcohols could be anchored on the samples during their washing process. In addition, no characteristic peaks assignable to Au oxides are observed for the 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 composite, implying Au species exists in the metallic state.

Figure 8.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra of CaTiO3 and 4.3%Au@CaTiO3.

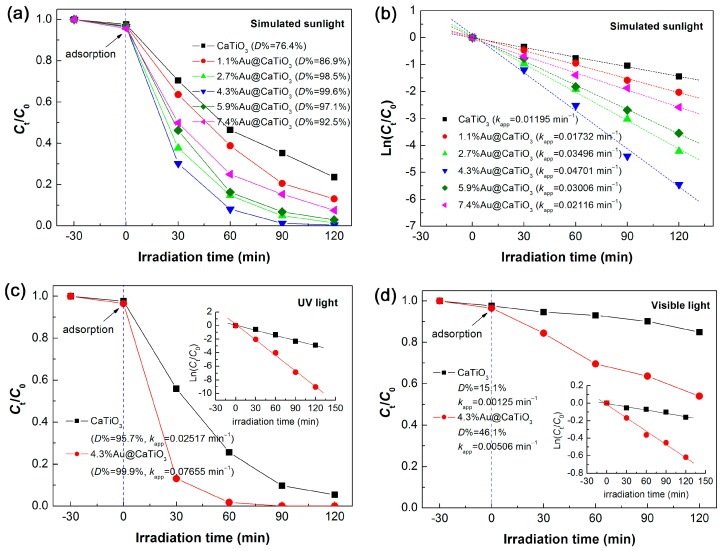

To assess the photocatalytic degradation of RhB over the samples, three types of light source were separately used, i.e., simulated sunlight (300 < λ < 2500 nm), UV light (λ = 254 nm) and visible light (λ > 400 nm). Figure 9a shows the simulated-sunlight degradation of RhB photocatalyzed by CaTiO3 and Au@CaTiO3 composites. It is demonstrated that the Au@CaTiO3 composites manifests a photocatalytic activity much superior to that of bare CaTiO3 NCs. The content of decorated Au NPs has an obvious effect on the photocatalytic activity of the composite samples. With increasing the Au content, the photocatalytic activity of the samples gradually increases and reaches the highest level for 4.3%Au@CaTiO3. However, further increasing the Au content gives rise to a decrease in the photocatalytic activity. This could be explained by the fact that excessive decoration of Au NPs on the surface of CaTiO3 NCs could reduce the light absorption of CaTiO3. The degradation percentage of RhB after 120 min of photocatalytic reaction is inserted in Figure 9a. For the optimal composite sample—4.3%Au@CaTiO3, the dye degradation reaches 99.6%, which is increased by 23.2% when compared with that for bare CaTiO3 (76.4%). We also carried out the kinetic analysis of the dye degradation over the samples, as illustrated in Figure 9b. One can see that the plots of Ln(Ct/C0) vs. t present a good linear relationship and can be perfectly described using the pseudo-first-order kinetic equation: Ln(Ct/C0) = −kappt [69,70]. Based on the linear-regression fitting, the apparent first-order reaction rate constant kapp is obtained, as inserted in Figure 9b. It is concluded from the reaction rate constants (kapp(CaTiO3) = 0.01195 min−1; kapp(4.3%Au@CaTiO3) = 0.04701 min−1) that the photocatalytic activity of 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 is ~3.9 times as large as that of bare CaTiO3. Further comparison of the UV and visible-light photocatalytic performance between CaTiO3 and 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 was carried out. As shown in Figure 9c, CaTiO3 exhibits an important UV photocatalytic activity toward the degradation of RhB. Moreover, a significantly enhanced UV photocatalytic activity is observed for the 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 composite photocatalyst, which is ca. 3.0 times larger than that of bare CaTiO3. The visible-light photocatalytic degradation of RhB over CaTiO3 and 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 is shown in Figure 9d. It is observed that bare CaTiO3 photocatalyzes only 15.1% degradation of the dye after 120 min of photocatalysis, which could be ascribed to the dye-photosensitized degradation. This is indicative of a poor photocatalytic activity of CaTiO3. Whereas 46.1% of RhB is observed to be degraded over 4.3%Au@CaTiO3, implying a greatly enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity of the composite.

Figure 9.

(a) Time-dependent photocatalytic degradation of RhB over bare CaTiO3 and Au@CaTiO3 composites under simulated sunlight irradiation. (b) Kinetic plots of the dye degradation over the samples under simulated sunlight irradiation. (c) UV and (d) visible-light photocatalytic degradation of RhB over bare CaTiO3 and 4.3%Au@CaTiO3.

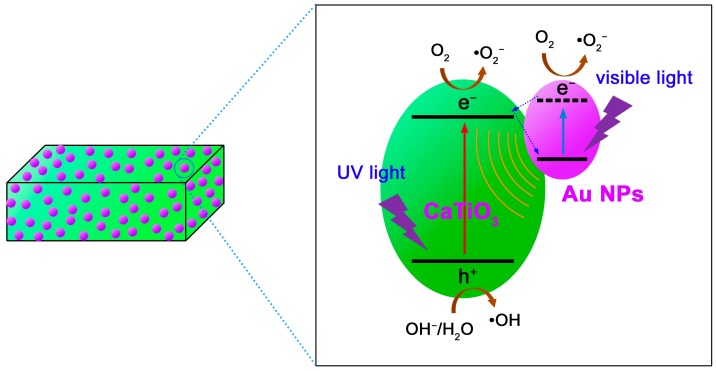

Based on the above experimental results, we propose a possible mechanism to elucidate the enhanced photocatalytic performance of the Au NPs modified CaTiO3 NCs, as schematically depicted Figure 10. Under UV irradiation, CaTiO3 is excited to produce electrons in the CB and holes in the valence band (VB) of the semiconductor. Au NPs cannot be excited under UV irradiation, but they can act as excellent electron sinks to capture the photogenerated electrons in CaTiO3. This is because the Fermi level of Au (+0.45 V vs. normal hydrogen electrode (NHE) [71,72]) is more positive than the CB potential of CaTiO3 (−0.43 V vs. NHE [55]). The electron transfer process from the CB of CaTiO3 to Au NPs promotes the spatial separation of the electron/hole pairs in CaTiO3. This is supported by photoluminescence spectra (Figure S1), photocurrent response curves (Figure S2a) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) spectra (Figure S2b). As a result, more holes in the VB of CaTiO3 are available for taking part in the photocatalytic reactions. Under visible-light irradiation, CaTiO3 cannot be directly excited to produce electron/hole pairs, instead LSPR of Au NPs is induced by the visible-light absorption [39,40]. The LSPR-induced electrons in Au NPs could take part in the photocatalytic reactions, and moreover, the electromagnetic field caused by LSPR could stimulate the generation of electron/hole pairs in CaTiO3. This is why the Au@CaTiO3 composites also manifest enhanced visible-light photocatalytic degradation of RhB. When simulated sunlight is used as the light source, Au NPs simultaneously act as electron sinks and behave as LSPR effect in the Au@CaTiO3 composites. The two mechanisms collectively result in the enhanced photocatalytic performance of the composites under simulated sunlight irradiation.

Figure 10.

Schematic illustration of the photocatalytic mechanism of the Au@CaTiO3 composites.

Hydroxyl (•OH), superoxide (•O2−) and h+ are generally considered to be the main active species in most of photocatalytic systems [73]. The reactive species trapping experiments (Figure S3) reveal that the degradation of RhB is highly correlated with •OH and h+. However, the photogenerated h+ could not directly oxide the dye, but rather reacts with OH− or H2O to produce another stronger oxidant •OH. Thermodynamically •OH is ready to be generated through the reaction between h+ and OH−/H2O due to the sufficiently positive VB potential of CaTiO3 (+2.93 V vs. NHE [55]) when compared with the redox potentials of H2O/•OH (+2.38 V vs. NHE) and OH−/•OH (+1.99 V vs. NHE) [74]. •O2− plays only a slight role in the photocatalytic degradation of the dye. The sufficiently negative CB potential of CaTiO3 (−0.43 V vs. NHE) suggests that the generation of •O2− can be derived from the reaction of adsorbed O2 with the CB electrons of CaTiO3 (E0(O2/•O2− = −0.13 V vs. NHE) [74]. Moreover, the LSPR-induced electrons in Au NPs could also combine with O2 to produce •O2−. Recycling photocatalytic experiment (Figure S4) is indicative of a good recycling stability of the Au@CaTiO3 composite photocatalyst.

4. Conclusions

Based on a hydrothermal route, CaTiO3 NCs were synthesized using P25 as the titanium source, and their growth process was investigated by varying the reaction time. Au NPs were uniformly decorated on the CaTiO3 NCs surface by a photocatalytic reduction of HAuCl4 solution. Compared to bare CaTiO3 NCs, the as-derived Au@CaTiO3 composites manifest an increased visible-light absorption, increased photocurrent density, decreased charge-transfer resistance, decreased PL intensity, as well as enhanced photocatalytic performance for the degradation of RhB under irradiation of different light sources (simulated sunlight, UV light and visible light). The optimal composite sample, observed to be 4.3%Au@CaTiO3, has a photocatalytic activity 3.9 times as large as that of bare CaTiO3 NCs, and photocatalyzes 99.6% degradation of RhB under simulated sunlight irradiation for 120 min. The enhanced photocatalytic mechanism of the Au@CaTiO3 composites can be explained by (1) the efficient separation of photoexcited e−/h+ pairs in CaTiO3 due to the electron transfer from CaTiO3 NCs to Au NPs, and (2) increased visible-light absorption due to the LSPR effect of Au NPs. The LSPR-caused electromagnetic field could stimulate the generation and separation of e−/h+ pairs in CaTiO3, and moreover, the LSPR-induced electrons in Au NPs could be available for the photodegradation reactions. Reactive species trapping experiments reveal that the dye degradation is highly correlated with •OH radicals and photoexcited holes, whereas •O2− radicals play only a slight role in the photocatalysis. The present Au@CaTiO3 nanocomposite photocatalysts could offer promising applications in the design of micro/nano photocatalytic devices for the wastewater treatment.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2072-666X/10/4/254/s1, Figure S1. PL spectra of CaTiO3 and 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 measured at an excitation wavelength of 375 nm; Figure S2. (a) Transient photocurrent response curves and (b) EIS spectra of CaTiO3 and 4.3%Au@CaTiO3; Figure S3. Effect of ethanol, BQ and AO on the degradation of RhB over 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 under simulated sunlight irradiation; Figure S4. Reusability of 4.3%Au@CaTiO3 for the RhB degradation under simulated sunlight irradiation.

Author Contributions

H.Y. conceived the idea of experiment; Y.Y. performed the experiments; H.Y., Y.Y., Z.Y., R.L. and X.W. discussed the results; H.Y. wrote the manuscript; all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51662027) and the HongLiu First-Class Disciplines Development Program of Lanzhou University of Technology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Khataeea A.R., Kasiri M.B. Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes in the presence of nanostructured titanium dioxide: Influence of the chemical structure of dyes. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2010;328:8–26. doi: 10.1016/j.molcata.2010.05.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown M.A., De Vito S.C. Predicting azo dye toxicity. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1993;23:249–324. doi: 10.1080/10643389309388453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di L.J., Yang H., Xian T., Chen X.J. Facile synthesis and enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity of novel p-Ag3PO4/n-BiFeO3 heterojunction composites for dye degradation. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2018;13:257. doi: 10.1186/s11671-018-2671-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pathakoti K., Manubolu M., Hwang H.M. Handbook of Nanomaterials for Industrial Applications. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2018. Chapter 48-nanotechnology applications for environmental industry; pp. 894–907. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xia Y.M., He Z.M., Yang W., Tang B., Lu Y.L., Hu K.J., Su J.B., Li X.P. Effective charge separation in BiOI/Cu2O composites with enhanced photocatalytic activity. Mater. Res. Express. 2018;5:025504. doi: 10.1088/2053-1591/aaa9ee. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rauf M.A., Salman Ashraf S. Fundamental principles and application of heterogeneous photocatalytic degradation of dyes in solution. Chem. Eng. J. 2009;151:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2009.02.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeng Y., Chen X.F., Yi Z., Yi Y.G., Xu X.B. Fabrication of p-n heterostructure ZnO/Si moth-eye structures: Antireflection, enhanced charge separation and photocatalytic properties. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018;441:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guin J.P., Naik D.B., Bhardwaj Y.K., Varshney L. An insight into the effective advanced oxidation process for treatment of simulated textile dye waste water. RSC Adv. 2014;4:39941–39947. doi: 10.1039/C4RA00884G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao X.X., Yang H., Li R.S., Cui Z.M., Liu X.Q. Synthesis of heterojunction photocatalysts composed of Ag2S quantum dots combined with Bi4Ti3O12 nanosheets for the degradation of dyes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2019;26:5524–5538. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-4050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xia Y., He Z., Su J., Liu Y., Tang B. Fabrication and photocatalytic property of novel SrTiO3/Bi5O7I nanocomposites. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2018;13:148. doi: 10.1186/s11671-018-2558-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H., Du L., Yang L.L., Zhang W.J., He H.B. Sol-gel synthesis of La2Ti2O7 modified with PEG4000 for the enhanced photocatalytic activity. J. Adv. Oxid. Technol. 2016;19:366–371. doi: 10.1515/jaots-2016-0221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akpan U.G., Hameed B.H. Parameters affecting the photocatalytic degradation of dyes using TiO2-based photocatalysts: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009;170:520–529. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan Y.X., Yang H., Zhao X.X., Li R.S., Wang X.X. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of surface disorder-engineered CaTiO3. Mater. Res. Bull. 2018;105:286–290. doi: 10.1016/j.materresbull.2018.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alam U., Khan A., Raza W., Khan A., Bahnemann D., Muneer M. Highly efficient Y and V co-doped ZnO photocatalyst with enhanced dye sensitized visible light photocatalytic activity. Catal. Today. 2017;284:169–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cattod.2016.11.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y.F., Fu F., Li Y.Z., Zhang D.S., Chen Y.Y. One-step synthesis of Ag@TiO₂ nanoparticles for enhanced photocatalytic performance. Nanomaterials. 2018;8:1032. doi: 10.3390/nano8121032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng C.X., Yang H., Cui Z.M., Zhang H.M., Wang X.X. A novel Bi4Ti3O12/Ag3PO4 heterojunction photocatalyst with enhanced photocatalytic performance. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017;12:608. doi: 10.1186/s11671-017-2377-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xia Y.M., He Z.M., Hu K.J., Tang B., Su J.B., Liu Y., Li X.P. Fabrication of n-SrTiO3/p-Cu2O heterojunction composites with enhanced photocatalytic performance. J. Alloys Compd. 2018;753:356–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.04.231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang S.F., Gao H.J., Wei Y., Li Y.W., Yang X.H., Fang L.M., Lei L. Insight into the optical, color, photoluminescence properties, and photocatalytic activity of the N-O and C-O functional groups decorating spinel type magnesium aluminate. CrystEngComm. 2019;21:263–277. doi: 10.1039/C8CE01474D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tayyebi A., Soltani T., Hong H., Lee B.K. Improved photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical performance of monoclinic bismuth vanadate by surface defect states (Bi1−xVO4) J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018;514:565–575. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2017.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang S.Y., Yang H., Wang X.X., Feng W.J. Surface disorder engineering of flake-like Bi2WO6 crystals for enhanced photocatalytic activity. J. Electron. Mater. 2019;48:2067–2076. doi: 10.1007/s11664-019-07045-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang X.X., Wu X.X., Zhu J.K., Pang Z.Y., Yang H., Qi Y.P. Theoretical investigation of a highly sensitive refractive-index sensor based on TM0 waveguide mode resonance excited in an asymmetric metal-cladding dielectric waveguide structure. Sensors. 2019;19:1187. doi: 10.3390/s19051187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernando K.A.S., Sahu S.P., Liu Y., Lewis W.K., Guliants E., Jafariyan A., Wang P., Bunker C.E., Sun Y.P. Carbon quantum dots and applications in photocatalytic energy conversion. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2015;7:8363–8376. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b00448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Devil P., Thakur A., Bhardwaj S.K., Saini S., Rajput P., Kumar P. Metal ion sensing and light activated antimicrobial activity of aloevera derived carbon dots. J. Mater. Sci.-Mater. Electron. 2018;29:17254–17261. doi: 10.1007/s10854-018-9819-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yi Z., Liu L., Wang L., Cen C., Chen X., Zhou Z., Ye X., Yi Y., Tang Y., Yi Y., et al. Tunable dual-band perfect absorber consisting of periodic cross-cross monolayer graphene arrays. Results Phys. 2019;13:102217. doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2019.102217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X.X., Tong H., Pang Z.Y., Zhu J.K., Wu X.X., Yang H., Qi Y.P. Theoretical realization of three-dimensional nanolattice structure fabrication based on high-order waveguide-mode interference and sample rotation. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2019;51:38. doi: 10.1007/s11082-019-1759-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X.X., Zhu J.K., Tong H., Yang X.D., Wu X.X., Pang Z.Y., Yang H., Qi Y.P. A theoretical study of a plasmonic sensor comprising a gold nano-disk array on gold film with an SiO2 spacer. Chin. Phys. B. 2019;28:044201. doi: 10.1088/1674-1056/28/4/044201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu L., Chen J.J., Zhou Z.G., Yi Z., Ye X. Tunable absorption enhancement in electric split-ring resonators-shaped graphene array. Mater. Res. Express. 2018;5:045802. doi: 10.1088/2053-1591/aabbd9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cen C.L., Chen J.J., Liang C.P., Huang J., Chen X.F., Tang Y.J., Yi Z., Xu X.B., Yi Y.G., Xiao S.Y. Plasmonic absorption characteristics based on dumbbell-shaped graphene metamaterial arrays. Phys. E. 2018;103:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.physe.2018.05.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yi Z., Lin H., Niu G., Chen X.F., Zhou Z.G., Ye X., Duan T., Yi Y., Tang Y.J., Yi Y.G. triple-band plasmonic perfect metamaterial absorber with good angle-polarization-tolerance. Results Phys. 2019;13:102149. doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2019.02.085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yi Z., Chen J.J., Cen C.L., Chen X.F., Zhou Z.G., Tang Y.J., Ye X., Xiao S.Y., Luo W., Wu P.H. Tunable graphene-based plasmonic perfect metamaterial absorber in the THz region. Micromachines. 2019;10:194. doi: 10.3390/mi10030194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X.X., Bai X.L., Pang Z.Y., Zhu J.K., Wu Y., Yang H., Qi Y.P., Wen X.L. Surface-enhanced Raman scattering by composite structure of gold nanocube-PMMA-gold film. Opt. Mater. Express. 2019;9:1872–1881. doi: 10.1364/OME.9.001872. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang X.X., Pang Z.Y., Tong H., Wu X.X., Bai X.L., Yang H., Wen X.L., Qi Y.P. Theoretical investigation of subwavelength structure fabrication based on multi-exposure surface plasmon interference lithography. Results Phys. 2019;12:732–737. doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2018.12.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang J., Niu G., Yi Z., Chen X.F., Zhou Z.G., Ye X., Tang Y.J., Duan T., Yi Y., Yi Y.G. High sensitivity refractive index sensing with good angle and polarization tolerance using elliptical nanodisk graphene metamaterials. Phys. Scr. 2019 doi: 10.1088/1402-4896/ab185f. in press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao X.X., Yang H., Cui Z.M., Wang X.X., Yi Z. Growth process and CQDs-modified Bi4Ti3O12 square plates with enhanced photocatalytic performance. Micromachines. 2019;10:66. doi: 10.3390/mi10010066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahdiani M., Soofivand F., Ansari F., Salavati-Niasari M. Grafting of CuFe12O19 nanoparticles on CNT and graphene: Eco-friendly synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic activity. J. Clean. Prod. 2018;176:1185–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.11.177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cruz-Ortiz B.R., Hamilton J.W.J., Pablos C., Diaz-Jimenez L., Cortes-Hernandez D.A., Sharma P.K., Castro-Alferez M., Fernandez-Ibanez P., Dunlop P.S.M., Byrne J.A. Mechanism of photocatalytic disinfection using titania-graphene composites under UV and visible irradiation. Chem. Eng. J. 2017;316:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2017.01.094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Di L.J., Yang H., Xian T., Chen X.J. Construction of Z-scheme g-C3N4/CNT/Bi2Fe4O9 composites with improved simulated-sunlight photocatalytic activity for the dye degradation. Micromachines. 2018;9:613. doi: 10.3390/mi9120613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ji K.M., Deng J.G., Zang H.J., Han J.H., Arandiyan H., Dai H.X. Fabrication and high photocatalytic performance of noble metal nanoparticles supported on 3DOM InVO4-BiVO4 for the visible-light-driven degradation of rhodamine B and methylene blue. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2015;165:285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2014.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee J.E., Bera S., Choi Y.S., Lee W.I. Size-dependent plasmonic effects of M and M@SiO2 (M = Au or Ag) deposited on TiO2 in photocatalytic oxidation reactions. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2017;214:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.05.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.She P., Xu K.L., Zeng S., He Q.R., Sun H., Liu Z.N. Investigating the size effect of Au nanospheres on the photocatalytic activity of Au-modified ZnO nanorods. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017;499:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2017.03.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pang Z.Y., Tong H., Wu X.X., Zhu J.K., Wang X.X., Yang H., Qi Y.P. Theoretical study of multiexposure zeroth-order waveguide mode interference lithography. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2018;50:335. doi: 10.1007/s11082-018-1601-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang X.X., Bai X.L., Pang Z.Y., Yang H., Qi Y.P. Investigation of surface plasmons in Kretschmann structure loaded with a silver nano-cube. Results Phys. 2019;12:1866–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2019.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Biegalski M.D., Qiao L., Gu Y., Mehta A., He Q., Takamura Y., Borisevich A., Chen L.Q. Impact of symmetry on the ferroelectric properties of CaTiO3 thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015;106:162904. doi: 10.1063/1.4918805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu X.N., Gao T.T., Xu X., Liang W.Z., Lin Y., Chen C., Chen X.M. Piezoelectric and dielectric properties of multilayered BaTiO3/(Ba,Ca)TiO3/CaTiO3 thin films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2016;8:22309–22315. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b05469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tariq S., Ahmed A., Saad S., Tariq S. Structural, electronic and elastic properties of the cubic CaTiO3 under pressure: A DFT study. AIP Adv. 2015;5:77111. doi: 10.1063/1.4926437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shi X., Yang H., Liang Z., Tian A., Xue X. Synthesis of vertically aligned CaTiO3 nanotubes with simple hydrothermal method and its photoelectrochemical property. Nanotechnology. 2018;29:385605. doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/aacfde. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yan X., Huang X.J., Fang Y., Min Y.H., Wu Z.J., Li W.S., Yuan J.M., Tan L.G. Synthesis of rodlike CaTiO3 with enhanced charge separation efficiency and high photocatalytic activity. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2014;9:5155–5163. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lim S.N., Song S.A., Jeong Y.C., Kang H.W., Park S.B., Kim K.Y. H2 production under visible light irradiation from aqueous methanol solution on CaTiO3:Cu prepared by spray pyrolysis. J. Electron. Mater. 2017;46:6096–6103. doi: 10.1007/s11664-017-5551-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dong W.X., Song B., Zhao G.L., Meng W.J., Han G.R. Effects of the volume ratio of water and ethanol on morphosynthesis and photocatalytic activity of CaTiO3 by a solvothermal process. Appl. Phys. A. 2017;123:348. doi: 10.1007/s00339-017-0931-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alammara T., Hamma I., Warkb M., Mudring A.V. Low-temperature route to metal titanate perovskite nanoparticles for photocatalytic applications. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2015;178:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2014.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kimijima T., Kanie K., Nakaya M., Muramatsu A. Hydrothermal synthesis of size- and shape-controlled CaTiO3 fine particles and their photocatalytic activity. CrystEngComm. 2014;16:5591–5597. doi: 10.1039/C4CE00376D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ye M., Wang M., Zheng D., Zhang N., Lin C., Lin Z. Garden-like perovskite superstructures with enhanced photocatalytic activity. Nanoscale. 2014;6:3576–3584. doi: 10.1039/c3nr05564g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao X.X., Yang H., Li S.H., Cui Z.M., Zhang C.R. Synthesis and theoretical study of large-sized Bi4Ti3O12 square nanosheets with high photocatalytic activity. Mater. Res. Bull. 2018;107:180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.materresbull.2018.07.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pan J., Liu G., Lu G.Q., Cheng H.M. On the true photoreactivity order of {001}, {010}, and {101} facets of anatase TiO2 crystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:2133–2137. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yan Y.X., Yang H., Zhao X.X., Zhang H.M., Jiang J.L. A hydrothermal route to the synthesis of CaTiO3 nanocuboids using P25 as the titanium source. J. Electron. Mater. 2018;47:3045–3050. doi: 10.1007/s11664-018-6183-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bai L.Y., Xu Q., Cai Z.S. Synthesis of Ag@AgBr/CaTiO3 composite photocatalyst with enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity. J. Mater. Sci.-Mater. Electron. 2018;29:17580–17590. doi: 10.1007/s10854-018-9861-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alzahrani A., Barbash D., Samokhvalov A. “One-pot” synthesis and photocatalytic hydrogen generation with nanocrystalline Ag(0)/CaTiO3 and in situ mechanistic studies. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2016;120:19970–19979. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b05407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jiang Z.Y., Pan J.Q., Wang B.B., Li C.R. Two dimensional Z-scheme AgCl/Ag/CaTiO3 nano-heterojunctions for photocatalytic hydrogen production enhancement. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018;436:519–526. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.12.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang J.J., Jin Z.S., Wang X.D., Li W., Zhang J.W., Zhang S.L., Guo X.Y., Zhang Z.J. Study on composition, structure and formation process of nanotube Na2Ti2O4(OH)2. Dalton Trans. 2003:3898–3901. doi: 10.1039/b305585j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Durrania S.K., Khan Y., Ahmed N., Ahmad M., Hussain M.A. Hydrothermal growth of calcium titanate nanowires from titania. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2011;8:562–569. doi: 10.1007/BF03249091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zheng C.X., Yang H. Assembly of Ag3PO4 nanoparticles on rose flower-like Bi2WO6 hierarchical architectures for achieving high photocatalytic performance. J. Mater. Sci.-Mater. Electron. 2018;29:9291–9300. doi: 10.1007/s10854-018-8959-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pooladi M., Shokrollahi H., Lavasani S.A.N.H., Yang H. Investigation of the structural, magnetic and dielectric properties of Mn-doped Bi2Fe4O9 produced by reverse chemical co-precipitation. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2019;229:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2019.02.076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Camci M.T., Ulgut B., Kocabas C., Suzer S. In-situ XPS monitoring and characterization of electrochemically prepared Au nanoparticles in an ionic liquid. ACS Omega. 2017;2:478–486. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.6b00456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gao H.J., Wang F., Wang S.F., Wang X.X., Yi Z., Yang H. Photocatalytic activity tuning in a novel Ag2S/CQDs/CuBi2O4 composite: Synthesis and photocatalytic mechanism. Mater. Res. Bull. 2019;115:140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.materresbull.2019.03.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Y., Niu C.G., Wang L., Wang Y., Zhang X.G., Zeng G.M. Synthesis of fern-like Ag/AgCl/CaTiO3 plasmonic photocatalysts and their enhanced visible-light photocatalytic properties. RSC Adv. 2016;6:47873–47882. doi: 10.1039/C6RA06435C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roy A.S., Hegde S.G., Parveen A. Synthesis, characterization, AC conductivity, and diode properties of polyaniline–CaTiO3 composites. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2014;25:130–135. doi: 10.1002/pat.3214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang S.F., Gao H.J., Fang L.M., Wei Y., Li Y.W., Lei L. Synthesis and characterization of BaAl2O4 catalyst and its photocatalytic activity towards degradation of methylene blue dye. Z. Phys. Chem. 2019 doi: 10.1515/zpch-2018-1308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mert B.D., Mert M.E., Kardas G., Yazici B. Experimental and theoretical studies on electrochemical synthesis of poly(3-amino-1,2,4-triazole) Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012;258:9668–9674. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2012.04.180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ye Y.C., Yang H., Zhang H.M., Jiang J.L. A promising Ag2CrO4/LaFeO3 heterojunction photocatalyst applied to photo-Fenton degradation of RhB. Environ. Technol. 2018:1–18. doi: 10.1080/09593330.2018.1538261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Konstantinou I.K., Albanis T.A. TiO2-assisted photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes in aqueous solution: Kinetic and mechanistic investigations: A review. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2004;49:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2003.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Subramanian V., Wolf E.E., Kamat P.V. Catalysis with TiO2/Gold nanocomposites: Effect of metal particle size on the Fermi level equilibration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:4943–4950. doi: 10.1021/ja0315199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zheng C.X., Yang H., Cui Z.M. Enhanced photocatalytic performance of Au nanoparticles-modified rose flower-like Bi2WO6 hierarchical architectures. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 2017;125:887–893. doi: 10.2109/jcersj2.17148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhao X.X., Yang H., Zhang H.M., Cui Z.M., Feng W.J. Surface-disorder-engineering-induced enhancement in the photocatalytic activity of Bi4Ti3O12 nanosheets. Desalin. Water Treat. 2019;145:326–336. doi: 10.5004/dwt.2019.23710. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Di L.J., Yang H., Xian T., Liu X.Q., Chen X.J. Photocatalytic and photo-Fenton catalytic degradation activities of Z-scheme Ag2S/BiFeO3 heterojunction composites under visible-light irradiation. Nanomaterials. 2019;9:399. doi: 10.3390/nano9030399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.