Abstract

Many marine species inhabiting icy seawater produce antifreeze proteins (AFPs) to prevent their body fluids from freezing. The sculpin species of the superfamily Cottoidea are widely found from the Arctic to southern hemisphere, some of which are known to express AFP. Here we clarified DNA sequence encoding type I AFP for 3 species of 2 families (Cottidae and Agonidae) belonging to Cottoidea. We also examined antifreeze activity for 3 families and 32 species of Cottoidea (Cottidae, Agonidae, and Rhamphocottidae). These fishes were collected in 2013–2015 from the Arctic Ocean, Alaska, Japan. We could identify 8 distinct DNA sequences exhibiting a high similarity to those reported for Myoxocephalus species, suggesting that Cottidae and Agonidae share the same DNA sequence encoding type I AFP. Among the 3 families, Rhamphocottidae that experience a warm current did not show antifreeze activity. The species inhabiting the Arctic Ocean and Northern Japan that often covered with ice floe showed high activity, while those inhabiting Alaska, Southern Japan with a warm current showed low/no activity. These results suggest that Cottoidea acquires type I AFP gene before dividing into Cottidae and Agonidae, and have adapted to each location with optimal antifreeze activity level.

Keywords: antifreeze proteins, cold adaptations, Cottoidea, thermal hysteresis

1. Introduction

How creatures expand their distribution range by acquiring adaptive traits, and which mechanisms and/or adaptations decide this distribution range is a central and universal problem in evolutionary ecology. Acquisition of thermal tolerance is important for adaptation to cold and hot habitats. For these adaptations, many species express heat shock proteins [1,2], antifreeze proteins (AFPs) and antifreeze glycoproteins (AFGPs) [3,4].

Many marine species inhabiting icy seawater produce AF(G)Ps to prevent their body fluids from freezing [3,5,6], and type I–III AFPs and AFGPs have been found in marine fishes [7,8,9,10,11]. These proteins are thought to inhibit ice growth by irreversible adsorption to the surface of nascent ice crystals generated at the freezing point of water [12]. The acquisitions of AF(G)P enable adaptation to cold environments, and are closely related to geographic events. The cold period started after 35 million years ago (Ma) when the Antarctica was formed [13], and AFGP acquisition enabled Notothenia fishes survive these cold periods. These fishes rapidly speciated and adaptively radiated, because fishes without cold tolerance leave Antarctica during cold periods. On the other hand, in the Arctic Ocean, the formation of ice-sheets began 47.5 Ma [14], and developed after 3 Ma. The genus Myoxocephalus, inhabiting the northern hemisphere, included in the Cottidae, are estimated to have acquired AFP at least 30 Ma [15]. In addition, cunner is thought to have acquired AFP at the last glaciation, because this species express AFPs only in epithelial cells [16].

Superfamily Cottoidea was recently reconstructed with 7 families, 94 genera and 387 species; Jordanidae, Rhamphocottidae (Ereuniidae), Scorpaenichthyidae, Agonidae (Hemitripteridae), Cottidae, Psychrolutidae, and Bathylutichthyidae [17]. The species are mainly distributed in the high latitude area of the northern hemisphere, and 6 families, 22 genera and 72 species are found in the Arctic Ocean [18]. In the superfamily Cottoidea, type II AFPs are found in the family Agonidae (Hemitripterus americanus, Brachyopsis rostratus) [19,20], and a type I AFP is found in the family Cottidae (Myoxocephalus spp.) [21]. In the genus Myoxocephalus, Arctic species, M. scorpius, M. aenaeus, and M. polyacanthocephalus, show higher antifreeze activity, and subarctic–temperate species, M. stelleri, shows lower antifreeze activity [15,21,22]. The deep-sea species M. octodecemspinosus express AFP only in the skin [23], not in plasma [24]. A total of 5 genera and 5 species possess antifreeze activity in the superfamily Cottoidea: Hemilepidotus jordani, Gymnocanthus herzensteini, Furcina osimae [25,26], longsnout poacher, Brachyopsis rostratus [27], and sea raven, Hemitripterus americanus [9]. However, the antifreeze activity in almost species is still unknown in this superfamily. To understand cold adaptation in the superfamily Cottoidea, we clarified DNA sequences encoding type I AFP for 2 families and 3 species, and antifreeze activities for 4 families and 32 species. We lastly discussed about the acquisition of AFP and adaptation to the cold region in the superfamily Cottoidea.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collections

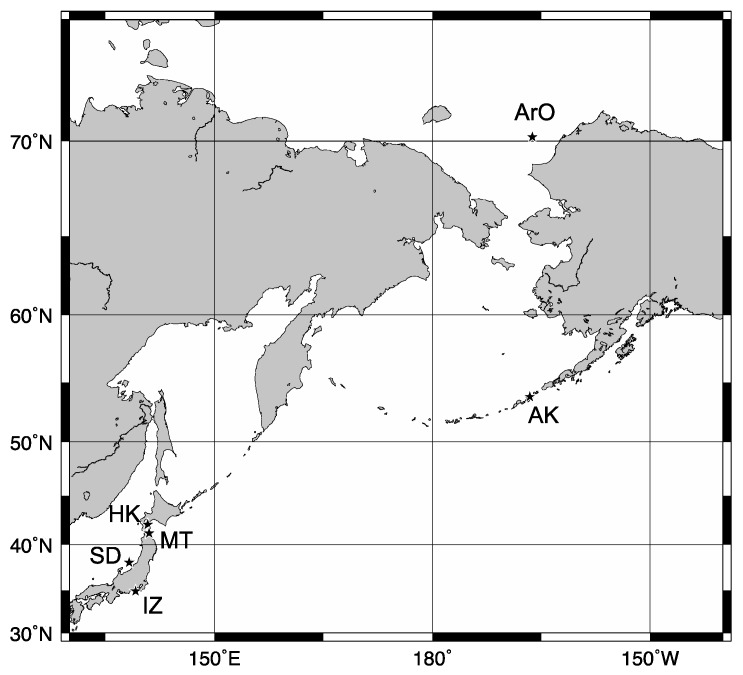

Samples were collected from the Arctic Ocean, Alaska, Hokkaido, Mutsu, Sado Island and Izu (Figure 1). Detailed information of each location is presented in Table 1. Sculpins were identified by morphological characters using the “Fishes of Alaska” [28], “Fishes of Japan” [29] at laboratory. Muscle tissues of five species from the Arctic Ocean (166.2308333° E, 70.18950° N), nine from Alaska (166.5858000° E, 53.8383333° N), thirteen from Hokkaido (140.8086° W, 42.07233333° N), three from Mutsu bay (140.9923333° W, 41.191° N), five from Sado Island (138.241° W, 38.07183333° N), and one from Izu (139.1303° W, 34.8847° N) were collected for antifreeze activity measurements (Table 1). Since the skin portion contains a mucoid substance that prevents the activity measurements, we removed that portion from the sample as much as possible. This removal also minimized the contamination of the skin-type AFP. These muscle tissues were preserved at −25 °C until measurement. For the determination of AFP sequences, the fresh dorsal fins and livers from Hemilepidotus jordani and Gymnocanthus tricuspis, collected in Alaska, and Porocottus allisi, collected in Hokkaido, were stocked overnight at 4 °C in RNAlater® Stabilization Solution (Life TechnologiesTM, Carlsbad, CA, USA) to thoroughly penetrate cells, and then stocked at −80 °C for long storage. These treatments were according to the Hokkaido University Regulations of Animal Experimentation.

Figure 1.

Sampling locations are represented with stars. ArO: the Arctic Ocean, AK: Alaska, HK: Hokkaido, MT: Mutsu, SD: Sado Island, IZ: Izu.

Table 1.

Sampling locations and antifreeze activities. SBT: Sea bottom temperature (°C), N: number of species.

| Location | Date | SBT | N | Antifreeze Activity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | None | ||||

| Arctic Ocean | July 2013 | −0.7 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 1 |

| Alaska | March 2014 | 3.6 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 5 |

| Hokkaido | April 2014 | 4.4 | 13 | 7 | 3 | 3 |

| Mutsu Bay | December 2013 | 10.4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Sado Island | February 2014 | 9.6 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Izu | March 2015 | 7.0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Summary * | 32 | 14 | 6 | 16 | ||

* Include duplicated species.

2.2. Measurement of Antifreeze Activities

DeVries [30] showed that the freezing point of blood that does not contain AFP is 0.01 °C. Several articles have shown that type I–III AFP were successfully purified from fish muscle homogenates, and described fish muscle as a rich source of AFP [20,25,31,32,33]. It has also been shown that the ice-shaping ability of AFP is not nullified by contaminants present in body fluid, such as blood serum. Hence, we used minced muscle homogenates as a source material for examining antifreeze activity. After weighing the muscle tissues, they were homogenized, using a Beadbeater (Biospec, Bartlesville, OK, USA), in tubes containing an equal amount of distilled water, and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 15 minutes to obtain supernatant solutions for antifreeze activity measurement. Antifreeze activity was measured using a temperature-controlled stage, as described by Takamichi et al. [34]. The supernatant solutions were super-cooled −55 °C/min, heated up 5 °C/min after being complete frozen, and cooled down −1 °C/min. As ice crystals change shapes, depending on the AFP concentrations or the ice-binding power [35,36,37], the level of antifreeze activity was defined as follows: “high level” with the formation of bi-pyramidal ice crystals, “low level” with hexagonal ice crystals, and “zero” with other shapes.

2.3. cDNA Syntheses, Cloning, and Sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from fin clips that collected at Alaska and Hokkaido using the QuickGene RNA tissue kit S II (QuickGene 800, Kurabo, Japan) and DNase I Amplification Grade (InvitrogenTM, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The first strand cDNA was synthesized from the RNA, using SuperScript VILO (InvitrogenTM, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was conducted to select candidate AFP genes from each reverse transcription (RT)-PCR amplicon. Five primers (5’1, 5’2, Deg1, 3’1 and 3’2) [38] and one primer (LS-ST-P2) [15] were used in three combinations (5’1 and 3’1, 5’2 and 3’1, and LS-ST-P2 and 3’1) in the first PCR, and then the same four primers except 5’1 and 3’1 primers in all possible combinations were used for the second PCR, with the first PCR products serving as the DNA templates (Table 2). The concentration of each primer was 0.4 µM. KOD-Plus- Ver. 2 (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan), including KOD DNA polymerase, was used for both PCRs. PCR products from a single RT-PCR amplicon were pooled and sub-cloned, using the TArget CloneTM -Plus- system (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transformations into E. coli (ECOSTM Competent E. coli JM109, Nippongene, Tokyo, Japan) were conducted by the heat shock method, and bacteria were then incubated on LB/amp/IPTG/X-gal plates containing ampicillin for 12 hours at 37 °C. After blue/white selection, all the white colonies were re-streaked and amplified by colony PCR. Each reaction was conducted in a total volume of 50 µL, which consisted of 0.2 µM of each primer (universal T7 and T3 promoter primers), 1x EmeraldAmp PCR Master Mix (Takara Bio Inc., Siga, Japan), and the picked DNA sample. The PCR conditions were as follows: pre-denaturing at 95 °C for 1 min, 30 cycles of denaturing at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 60 °C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 3 min, and final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were purified using NucleoSpin® Gel and PCR Clean-up according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). Sequencing was conducted with two directions using same universal primers (T7 and T3 promoters) using Applied Biosystems 3730x1 DNA analyzer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) by Macrogen Japan (Kyoto, Japan).

Table 2.

Primer combinations.

| 1st Reaction | 2nd Reaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | Forward | Reverse |

| 5’1 | 3’1 | 5’2 | 3’2 |

| LS-ST-P2 | 3’2 | ||

| Deg1 | 3’2 | ||

| 5’2 | 3’1 | LS-ST-P2 | 3’2 |

| Deg1 | 3’2 | ||

| LS-ST-P2 | 3’1 | Deg1 | 3’2 |

2.4. Bioinformatics Analyses

To identify the phylogenetic relationships among Cottoidea, 40 genera and 40 species cited from GenBank were used in these analyses (Table S1). Sequences from four loci (RAG1, COI, Cytb, and 12SrRNA–tRNAVal–16SrRNA) were aligned using MEGA6 with default settings and adjusted visually. Gaps were identified and deleted using MAFFT ver. 7 [39] with the E-INS-i option, and trimAl ver. 1.2 [39,40] with no gap option. Kakusan4 [41] was used to determine the appropriate model for each gene. The maximum likelihood method was also explored using RAxML ver. 7.2.8 [42]. The blanches were colored by the Phytools. The northern distributional limit of the species and the distributional depth range were cited from FishBase [43].

3. Results

3.1. Antifreeze Activity

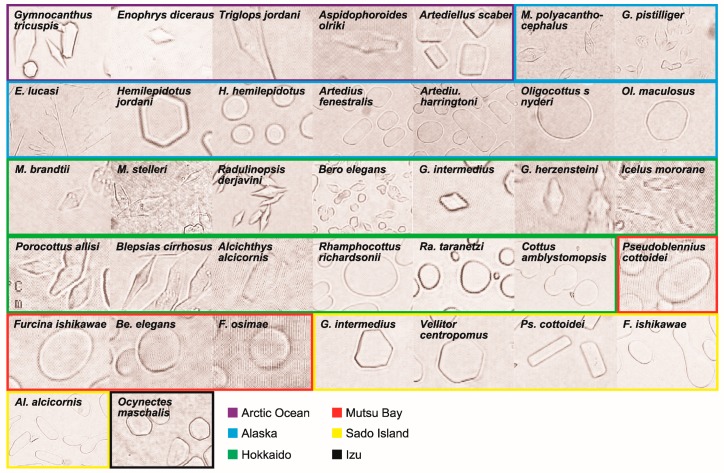

Fourteen of the 32 species examined showed high antifreeze activity, 5 showed low activity, and 13 showed no activity (Table 1, Figure 2, some species was duplicated due to being collected from several locations, see Table 3). Many species inhabiting the Arctic Ocean showed high-level antifreeze activity, while most of the southern species from Sado and Izu showed no activity.

Figure 2.

Ice-crystal photos of all species. Bi-pyramidal ice-crystal represents high antifreeze activity, hexagonal ice-crystal represents low antifreeze activity, and other shapes represents inactivity. Solid squares are colored by location; purple, blue, green, red, yellow, and black show the Arctic Ocean, Alaska, Hokkaido, Mutsu Bay, Sado Island, and Izu, respectively.

Table 3.

Sample information and antifreeze activities in Cottoidea. ArO: Arctic Ocean, AK: Alaska, HK: Hokkaido, MT: Mutsu, SD: Sado Island, IZ: Izu.

| Family | Genus | Species | Location | Depth | Date | Antifreeze Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cottidae | Alcichthys | alcicornis | HK | Subtidal | April 2015 | Low |

| SD | February 2014 | None | ||||

| Artediellus | scaber | ArO | Subtidal | July 2013 | None | |

| Artedius | fenestralis | AK | Tidal | March 2014 | None | |

| harringtoni | AK | Tidal | March 2014 | None | ||

| Bero | elegans | HK | Subtidal | April 2014 | Low | |

| MT | December 2013 | None | ||||

| Cottus | amblystomopsis | HK | Stream | April 2014 | None | |

| Enophrys | lucasi | AK | Subtidal | March 2014 | High | |

| diceraus | ArO | Subtidal | July 2013 | High | ||

| Furcina | ishikawae | MT | Subtidal | December 2013 | None | |

| SD | February 2014 | None | ||||

| osimae | MT | Subtidal | December 2013 | None | ||

| Gymnocanthus | tricuspis | ArO | Subtidal | July 2013 | High | |

| pistilliger | AK | Subtidal | March 2014 | High | ||

| herzensteini | HK | Subtidal | April 2014 | High | ||

| Janurary 2015 | High | |||||

| intermedius | HK | Subtidal | April 2014 | High | ||

| March 2015 | High | |||||

| SD | February 2014 | Low | ||||

| Icelus | mororane | HK | Subtidal | March 2015 | High | |

| Myoxocephalus | polyacanthocephalus | AK | Subtidal | March 2014 | High | |

| stelleri | HK | Subtidal | November 2014 | None | ||

| Janurary 2015 | Low | |||||

| February 2015 | None | |||||

| March 2015 | High | |||||

| April 2015 | Low | |||||

| brandtii | HK | Subtidal | Janurary 2015 | None | ||

| February 2015 | None | |||||

| March 2015 | High | |||||

| April 2015 | High | |||||

| Oligocottus | snyderi | AK | Tidal | March 2014 | None | |

| maculosus | AK | Tidal | March 2014 | None | ||

| Ocynectes | maschalis | IZ | Tidal | April 2015 | None | |

| Porocottus | allisi | HK | Subtidal | March 2015 | High | |

| Pseudoblennius | cottoides | SD | Subtidal | November 2013 | None | |

| February 2014 | None | |||||

| MT | December 2013 | None | ||||

| Radulinopsis | taranetzi | HK | Subtidal | April 2014 | None | |

| derjavini | HK | Subtidal | April 2014 | High | ||

| Triglops | pingelii | ArO | Subtidal | July 2013 | High | |

| Vellitor | centropomus | SD | Subtidal | November 2013 | None | |

| February 2014 | Low | |||||

| Rhamphocottidae | Rhamphocottus | richardsonii | HK | Subtidal | April 2014 | None |

| Agonidae | Aspidophoroides | olrikii | ArO | Subtidal | July 2013 | High |

| Blepsias | cirrhosus | HK | Subtidal | April 2014 | High | |

| Hemilepidotus | hemilepidotus | AK | Subtidal | March 2014 | None | |

| jordani | AK | Subtidal | March 2014 | Low | ||

| 3 families | 20 genera | 32 species |

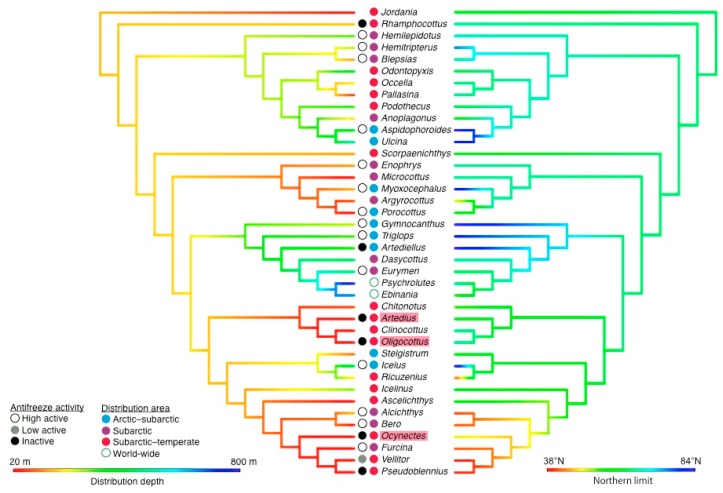

In the family Cottidae, 12 species showed high activity, 4 showed low activity and 11 showed no activity. In the family Agonidae, 2 species showed high activity, 1 showed low activity and 1 showed no activity. The family Ramphocottidae showed no activity (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Molecular phylogeny and antifreeze activity in the superfamily Cottoidea. White, grey, and black circles represent genera with high, low, and no antifreeze activity. Colored circles represent the distribution area; blue, purple, and red show the genera inhabiting the Arctic–subarctic, subarctic, subarctic–temperate areas, respectively; the green-lined circles show the genera inhabiting world-wide. The left tree is colored by the distribution depth; 20 m depth is colored red and 800 m depth is colored blue. The right tree is colored by the northern limit of the distribution area; 38° N is colored red and 84° N is colored blue.

Almost all species in the Arctic Ocean except Artediellus scaber, maintained high-level antifreeze activity, even though they were collected in the summer. Some sculpins inhabiting Alaska exhibited marked activity, but the tide-pool species, including Artedius and Oligocottus, showed no activity. In Hokkaido, Radulinopsis taranetzi and Cottus amblystomopsis showed inactivity, and the other 11 species showed either high or low activities. Many species exhibiting no activity inhabited Mutsu Bay, Sado Island, and Izu, which are warm regions. Antifreeze activities differed among species within a genus, being noted in seven genera: Enophrys, Hemilepidotus, Radulinopsis, Gymnocanthus, Artedius, Icelus, and Myoxocephalus. Two species of Radulinopsis, inhabiting the same latitude and depth range, showed different activities. Antifreeze activity also differed by location for G. intermedius, Alcichthys alcicornis and Bero elegans. On the other hand, the temperate species Vellitor centropomus in Sado showed low antifreeze activity.

3.2. Genetic Structures of Cottidae Antifreeze Proteins

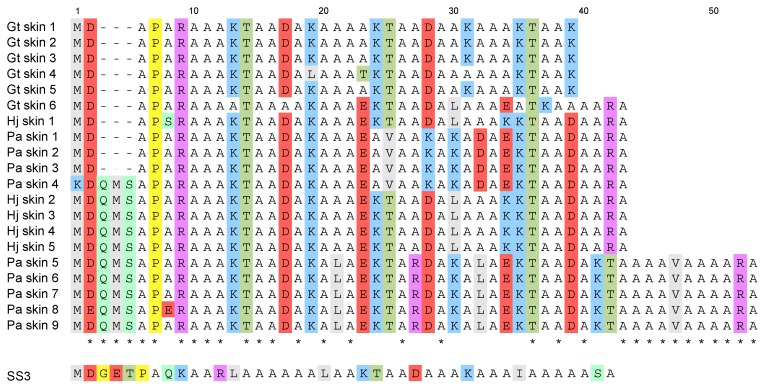

A total of 20 nucleotide sequences, encoding a total of 8 distinct AFPs, were identified (Figure 4). The deduced sequences encoded 4 distinct AFPs in P. allisi, 2 in H. jordani and 3 in G. tricuspis. These 8 sequences represent 5 new AFP variants as some of these sequences were previously known from Myoxocephalus species. This brings the total number of known sequences from the superfamily Cottoidea to 47. The lengths of AFP nucleotide sequences were 312–359 bp and open reading frame consisted of 40 residues in H. jordani, 243–308 bp and 36–40 residues in G. tricuspis, and 281–608 bp and 40–53 residues in P. allisi. The length and sequences of the 5’- and 3’-untranslated regions (UTR) differed among species (Figure S1). Three species show a preference for a particular Ala codon within the AFP sequences; between 44.0 and 59.0% of the Ala residues were encoded by the GCG codon. Three groups, according to a difference in peptide lengths, were determined as follows: 36-residue short isoform (SI), 40- or 43-residue medium isoform (MI), and 53-residue isoform. The 4 AFP sequences deduced from SI (G. tricuspis) are 100% identity to the 36-aa M. polyacanthocephalus sequence, one sequence from MI (P. allisi) is 100% identity to the 40-aa M. brandtii sequence, and nine other sequences from MI (G. tricuspis, P. allisi and H. jordani) are also similar to these sequences. In the coding region, there is 94.2%, 71.2%, and 99.2% identity among SI, MI, and 53-residue isoform, respectively. The 3’-UTRs show highly identity, with 95.3%, 69.6%, and 100% identity within SI, MI, and 53-residue isoform, respectively. The similarity between 53-residue isoform and MI (43-residues) are 79.2% in the coding region and 87.5% in the 3’-UTR. All sequence data were deposited in GenBank (Accession numbers: MK550897–MK550916).

Figure 4.

Amino acid sequences of type I antifreeze protein (AFP) from three Cottoidea species, Gymnocanthus tricuspis, Porocottus allisi, Myoxocephalus scorpius (SS3), and Hemilepidotus jordani. Thr are colored green. Polar residues (except Thr) are highlighted light green. Basic residues are highlighted blue (Lys) or purple (Arg), acidic are highlighted red (Asp and Glu), hydrophobic residues (except Ala) are highlighted gray (Met, Leu, and Val) and exceptional residues (Pro and Gly) are highlighted yellow. Hyphen (-) represents gaps. Asterisk (*) indicates the conserved site.

4. Discussion

4.1. Type I AFP Was Acquired before the Divergence within Cottoidea

The AFP sequences of Porocottus (Cottidae) are similar to those sequences of Hemilepidotus (Agonidae), and the AFP sequences of Gymnocanthus (Cottidae) are similar to those of Myoxocephalus (Cottidae). The 53-residue isoform sequences share more than 90% identity with AFP sequences from the shorthorn sculpin and longhorn sculpin [21,23]. High similarity between Cottidae and Agonidae indicates that the type I AFP is shared within the superfamily Cottoidea. This also suggests that the ancestral gene of type I AFP has been acquired before the divergence within Cottoidea. Moreover, in Agonidae, the longsnout poacher and the sea raven have type II AFPs [9,27], which are categorized into two: Ca2+-dependent type II AFP, found in Japanese smelt, Hypomesus nipponinsis [32], rainbow smelt, Osmerus mordax, and Atlantic herring, Clupea harengus harengus [44]; and Ca2+-independent type II AFP, found in sea raven, Hemitripterus americanus [19], and longsnout poacher, Brachyosis rostratus [20]. This Ca2+-independent type II AFP is larger than the type I AFPs of sculpins (163 residues in sea raven [45], 133-residues in longsnout poacher [20]). The type II AFPs were acquired by lateral gene transfer [46,47]. In addition, type I AFPs evolved convergence in four families (Pleuronectidae, Cottidae, Liparidae, and Libridae) [38]. Nonetheless, no single family has several AFP types. Our finding was the first report to have two types of AFPs within the family Agonidae. AFP type identification in the remained superfamily Cottoidea has the potential for contributing, not only to our understanding of the cold adaptation process, but also to understanding the unsolved phylogeny within Cottoidea.

4.2. Antifreeze Activity and Current Cold Adaptation

Antifreeze activity in Cottoidea was maintained in the Arctic–subarctic area, but declined in the tidal, deep, and temperate regions. Compared with other regions, almost all species inhabiting the Arctic Ocean showed high antifreeze activity. Many species inhabiting Hokkaido also showed high antifreeze activity. In Alaska, Mutsu, and more southern areas in Japan, most species showed low or no antifreeze activity. These differences are affected by sea currents; cold currents in Hokkaido, and warm currents in Alaska, Mutsu and more southern areas. Compared with the northern limit of the species’ distributional area, species located higher than 48° N in the Northwest Pacific Ocean and higher than 66° N in the North Pacific Ocean showed high antifreeze activity, but species located higher than 58° N showed low or no antifreeze activity. Therefore, the antifreeze activity differs even if the species inhabit the same latitude. The grunt sculpin Rhamphocottus richardosonii, a member of the family Rhamphocottidae, which showed no antifreeze activity is typically found in temperate regions: Japan, Alaska, and Southern California [43]. This species is thought to have expanded its distribution area along the Aleutian archipelagoes during warm periods, moved southward during cold periods, and then divided into the Northeast and Northwest Pacific Oceans, because many marine species moved to milder environment in the cold periods [48]. Therefore, freeze tolerance is not necessary for this species.

The hamecon, Artediellus scaber, inhabiting the Arctic Ocean, which was covered with ice sheet at the time of sampling, did not show antifreeze activity. Although the bottom temperatures were −1.8 °C near the sampling location, there was −0.7 °C at the sampling location. Almost all species in the family Psychlolutidae inhabit deep-water, but one species, the smoothcheek sculpin, Eurymen gyrinus, which inhabits shallow-water, shows high antifreeze activity [25]. In the icy-water area, the lumpfish, Cyclopterus lumpus (Cyclopteridae), and the sand flounder, Scophthalmus aquosus (Pleuronectidae), do not have antifreeze activity in the serum in winter [24]. The longhorn sculpin, which inhabits deep-water, also does not have antifreeze activity in the serum [24], but has antifreeze activity in the skin [23]. The cunner, which recently migrated to the Arctic region, also expresses AFP only in skin and gill filaments [16]. The external epithelia such as skin and gill filaments would be the first tissue to contact with ice. So, the species inhabiting non freeze-risk area and/or recently migrated to the freeze-risk area express AFP only in these tissues. On the other hand, some species of the family Nototheniidae hatch with underdeveloped gill structures, minimizing the risk of ice introduction through these delicate structures [49]. Given together, some hypotheses were proposed: (i) A. scaber has AFPs expressed in the muscle and/or serum during winter as known in many species; (ii) A. scaber expresses AFPs only in skin; and (iii) A. scaber does not have AFPs in the muscle and serum, other physical barriers such as underdeveloped gill structures, elevated osmolality of body fluids and/or mucus on the skin, contribute significantly to the freezing resistance and survival of A. scaber.

Many species decline or lose antifreeze activity in deep areas, such as wolffish, snailfish and flounder [24,50,51]. Generally, there is no freezing risk because of the absence of ice nuclei in the deep area. However, in the family Cottidae, some subtidal species maintain antifreeze activity. A lot of species both shallow- and deep-water species in the superfamily Cottoidea spawn in shallow areas during winter and some species lay on the eggs (e.g., Enophrys bison [52], Hemitripterus villosus [53,54]); so these deep-water species also need freeze tolerance. While subtidal species maintain antifreeze activity, the tide-pool species, such as Artedius, Oligocottus, and Ocynectes, which inhabit Alaska and Izu, do not show antifreeze activity. Tidal areas are hypoxia and dry environments, hence, species inhabit these areas need hypoxia and desiccation tolerance [55]. Alaska and Izu, where inactive species were collected, were not icy during winter. These species might express AFP only in the skin or do not express AFP, due to the expression of genes for hypoxia and desiccation tolerances.

4.3. Distributional Expansion to Cold Regions and Acquisition of AFP

Families Cottidae and Agonidae were originated at the Pacific Ocean (Briggs 2003), and almost sculpins and poachers are distributed in the North Pacific Ocean. Since Near, et al. [56] estimated that the superfamily Cottoidea and the family Liparidae diverged about 30 Ma, the Cottoidea is thought to have acquired the ancestral gene of type I AFP after the divergence, when the formation of ice-sheet had already started in the Arctic [14]. The type II AFP is found in only Agonidae in this superfamily, so Agonidae might acquire type II AFP after the divergence of this family.

The six families, 22 genera and 72 species inhabit the Arctic Ocean in the superfamily Cottoidea, and the species with eelpouts (Zoarcidae), which has type III AFP, reach more than half of all of the species in the Arctic Ocean [18]. A few species in other fishes, such as cods (Gadidae) with AFGP, flounders (Pleuronectidae) with type I AFP, salmons and herrings (Salmonidae and Clupeidae) with type II AFP, also inhabit the Arctic Ocean. In Zoarcidae, almost of the species of genus Lycodes, found in the Arctic Ocean, are estimated to have speciated about 3 Ma when the ice-sheet had developed [57]. Speciations in the Arctic and/or Atlantic Oceans indicate the adaptive radiations to cold regions occurred, so these fishes could occupy in the Arctic Ocean. Furthermore, the current species in the family Cottidae have hypoxia- and desiccation-tolerance even if the subtidal species [55], and some species adapt to fresh- and brackish-water [58], suggesting that these fishes could survive the past Arctic Ocean than the other fishes when the sea-level and salinity changed by glacial cycles. Given together, the superfamily Cottoidea could occupy the cold regions by acquiring various functional genes such as AFPs.

5. Conclusions

We clarified DNA sequence encoding type I AFP for 3 species of 2 families (Cottidae and Agonidae) belonging to Cottoidea. We could identify 8 distinct DNA sequences exhibiting a high similarity to those reported for Myoxocephalus species, suggesting that Cottidae and Agonidae share the same DNA sequence encoding type I AFP. Our findings were the first report that the family Agonidae has two types of AFPs. We also examined antifreeze activity for 3 families and 32 species of Cottoidea (Cottidae, Agonidae, and Rhamphocottidae), 14 species showed high antifreeze activity, 5 showed low activity, and 13 showed no activity. Among the 3 families, Rhamphocottidae that experience a warm current did not show antifreeze activity. Antifreeze activities differed among species within a genus (7 genera). Antifreeze activity also differed by location for 3 species. The species inhabiting the Arctic Ocean and northern Japan that often covered with ice floe showed high activity, while those inhabiting Alaska, southern Japan with a warm current showed low/no activity. These results suggest that Cottoidea acquires the ancestral genes of type I AFP before dividing into Cottidae and Agonidae about 30 Ma, and have adapted to each location by expressing optimal antifreeze activity level. Species in Cottoidea could occupy the cold regions by acquiring various functional genes such as AFPs.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Y. Koya, S. Awata, N. Sato, A. Miyajima, T. Igarashi, T/S Oshoro-maru, Alaska fish and games, Mac Enterprise, and Fisheries Cooperative Association of Aomori (Kawauchi and Wakinosawa) for sampling cooperation.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2218-273X/9/4/139/s1, Table S1: Accession number for molecular phylogenetic analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Y. and H.M.; Data curation, K.T.; formal analysis, A.Y., Y.N. and S.T.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Y.; writing—review and editing: Y.N. and S.T.; supervision, H.M.; funding acquisition, A.Y., S.T. and H.M.

Funding

This study was supported by Hokkaido University Grant for Research Activities Abroad, Research Fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS Research Fellow), Sasakawa Scientific Research Grant from The Japan Science Society (25-749), Sado City Grant for biodiversity studies, GRENE Arctic Climate Change Research Project, and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (Grant-in-Aid 26-1530, 25304001, 26292098).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Wang W., Hui J.H.L., Williams G.A., Cartwright S.R., Tsang L.M., Chu K.H. Comparative transcriptomics across populations offers new insights into the evolution of thermal resistance in marine snails. Mar. Biol. 2016;163:92. doi: 10.1007/s00227-016-2873-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Werner I., Linares-Casenave J., Van Eenennaam J.P., Doroshov S.I. The effect of temperature stress on development and heat-shock protein expression in larval green sturgeon (Acipenser mirostris) Environ. Biol. Fishes. 2006;79:191–200. doi: 10.1007/s10641-006-9070-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies P.L. Ice-binding proteins: A remarkable diversity of structures for stopping and starting ice growth. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2014;39:548–555. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fletcher G.L., Hew C.L., Davies P.L. Antifreeze proteins of teleost fishes. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2001;63:359–390. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeVries A.L. Role of glycopeptides and peptides in inhibition of crystallization of water in polar fishes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 1984;304:575–588. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng C.H. Evolution of the diverse antifreeze proteins. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1988;8:715–720. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(98)80042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeVries A.L., Wohlschlag D.E. Freezing resistance in some antarctic fishes. Science. 1969;163:1073–1075. doi: 10.1126/science.163.3871.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duman J.G., DeVries A.L. Isolation, characterization, and physical properties of protein antifreezes from the winter flounder, pseudopleuronectes americanus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 1976;54:375–380. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(76)90260-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slaughter D., Fletcher G.L., Ananthanarayanan V.S., Hew C.L. Antifreeze proteins from the sea raven, Hemitripterus americanus. Further evidence for diversity among fish polypeptide antifreezes. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:2022–2026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hew C., Slaughter D., Joshi S., Fletcher G., Ananthanarayanan V.S. Antifreeze polypeptides from the newfoundland ocean pout, Macrozoarces americanus: Presence of multiple and compositionally diverse components. J. Comp. Physiol. B. 1984;155:81–88. doi: 10.1007/BF00688795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X.-M., Trinh K.-Y., Hew C.L. Structure of an antifreeze polypeptide and its precursor from the ocean pout, Macrozoarces americanus. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:12904–12909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raymond J.A., DeVries A.L. Adsorption inhibition as a mechanism of freezing resistance in polar fishes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1977;74:2589–2593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.6.2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Near T.J., Dornburg A., Kuhn K.L., Eastman J.T., Pennington J.N., Patarnello T., Zane L., Fernandez D.A., Jones C.D. Ancient climate change, antifreeze, and the evolutionary diversification of antarctic fishes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:3434–3439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115169109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stickley C.E., St John K., Koç N., Jordan R.W., Passchier S., Pearce R.B., Kearns L.E. Evidence for middle eocene arctic sea ice from diatoms and ice-rafted debris. Nature. 2009;460:376–379. doi: 10.1038/nature08163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamazaki A., Nishimiya Y., Tsuda S., Togashi K., Munehara H. Gene expression of antifreeze protein in relation to historical distributions of myoxocephalus fish species. Mar. Biol. 2018;165:181. doi: 10.1007/s00227-018-3440-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hobbs R.S., Fletcher G.L. Epithelial dominant expression of antifreeze proteins in cunner suggests recent entry into a high freeze-risk ecozone. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2013;164:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson J.S., Grande T.C., Wilson M.V. Fishes of the World. 5th ed. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mecklenburg C.W., Møller P.R., Steinke D. Biodiversity of arctic marine fishes: Taxonomy and zoogeography. Mar. Biodivers. 2011;41:109–140. doi: 10.1007/s12526-010-0070-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng N.F., Khiet-Yen T., Hew C.L. Structure of an antifreeze polypeptide precursor from the sea raven, Hemitripterus americanus. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:15690–15695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishimiya Y., Kondo H., Takamichi M., Sugimoto H., Suzuki M., Miura A., Tsuda S. Crystal structure and mutational analysis of ca2+-independent type ii antifreeze protein from longsnout poacher, Brachyopsis rostratus. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;382:734–746. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Low W.K., Miao M., Ewart K.V., Yang D.S.C., Fletcher G.L., Hew C.L. Skin-type antifreeze protein from the shorthorn sculpin, Myoxocephalus scorpius: Expression and characterization of a mr 9,700 recombinant protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:23098–23103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reisman H.M., Fletcher G.L., Kao M.H., Shears M.A. Antifreeze proteins in the grubby sculpin, Myoxocephalus aenaeus and the tomcod, microgadus tomcod: Comparisons of seasonal cycles. Environ. Biol. Fishes. 1987;18:295–301. doi: 10.1007/BF00004882. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Low W.K., Lin Q., Stathakis C., Miao M., Fletcher G.L., Hew C.L. Isolation and characterization of skin-type, type i antifreeze polypeptides from the longhorn sculpin, Myoxocephalus octodecemspinosus. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:11582–11589. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009293200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duman J.G., DeVries A.L. The role of macromolecular antifreezes in cold water fishes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 1974;52:193–199. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9629(75)80152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahatabuddin S., Tsuda S. Applications of antifreeze proteins: Practical use of the quality products from japanese fishes. In: Iwaya-Inoue M., Sakurai M., Uemura M., editors. Survival Strategies in Extreme Cold and Desiccation. Springer; Heidelberg, Germany: 2018. pp. 321–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsuda S., Miura A. Antifreeze Proteins Originating in Fishes. Application No. 10,104. U.S. Patent. 2005 Jan 27;

- 27.Nishimiya Y., Kondo H., Yasui M., Sugimoto H., Noro N., Sato R., Suzuki M., Miura A., Tsuda S. Crystallization and preliminary x-ray crystallographic analysis of ca2+-independent and ca2+-dependent species of the type ii antifreeze protein. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2006;62:538–541. doi: 10.1107/S1744309106015570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mecklenburg C.W., Mecklenburg T.A., Thorsteinson L.K. Fishes of Alaska. American Fisheries Society; North Bethesda, MD, USA: 2002. p. 1037. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakabo T. Fishes of Japan with Pictoral Keys to the Species. 3rd ed. Tokai University Press; Kanagawa, Japan: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeVries A.L. Biological antifreeze agents in coldwater fishes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Physiol. 1982;73:627–640. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(82)90270-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahatabuddin S., Hanada Y., Nishimiya Y., Miura A., Kondo H., Davies P.L., Tsuda S. Concentration-dependent oligomerization of an alpha-helical antifreeze polypeptide makes it hyperactive. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:42501. doi: 10.1038/srep42501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamashita Y., Miura R., Takemoto Y., Tsuda S., Kawahara H., Obata H. Type ii antifreeze protein from a mid-latitude freshwater fish, Japanese smelt (Hypomesus nipponensis) Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2003;67:461–466. doi: 10.1271/bbb.67.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishimiya Y., Sato R., Takamichi M., Miura A., Tsuda S. Co-operative effect of the isoforms of type iii antifreeze protein expressed in notched-fin eelpout, Zoarces elongatus kner. FEBS J. 2005;272:482–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2004.04490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takamichi M., Nishimiya Y., Miura A., Tsuda S. Effect of annealing time of an ice crystal on the activity of type III antifreeze protein. FEBS J. 2007;274:6469–6476. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davies P.L., Hew C.L. Biochemistry of fish antifreeze proeins. FASEB J. 1990;4:2460–2468. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.4.8.2185972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahatabuddin S., Nishimiya Y., Miura A., Kondo H., Tsuda S. Critical ice shaping concentration (CICS): A new parameter to evaluate the activity of antifreeze proteins. Cryobiol. Cryotechnol. 2016;62:95–103. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rahman A.T., Arai T., Yamauchi A., Miura A., Kondo H., Ohyama Y., Tsuda S. Ice crystallization is strongly inhibited when antifreeze proteins bind to multiple ice planes. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:2212. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36546-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graham L.A., Hobbs R.S., Fletcher G.L., Davies P.L. Helical antifreeze proteins have independently evolved in fishes on four occasions. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e81285. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katoh K., Standley D.M. Mafft multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Capella-Gutiérrez S., Silla-Martínez J.M., Gabaldón T. Trimal: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanabe A.S. Kakusan4 and aminosan: Two programs for comparing nonpartitioned, proportional and separate models for combined molecular phylogenetic analyses of multilocus sequence data. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2011;11:914–921. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2011.03021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stamatakis A. Raxml-vi-hpc: Maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2688–2690. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Froese R., Pauly D. Fishbase. World Wide Web Electronic Publication. [(accessed on 28 February 2019)]; Available online: http://www.fishbase.org.

- 44.Ewart K.V., Fletcher G.L. Isolation and characterization of antifreeze proteins from smelt (osmerus mordax) and atlantic herring (clupea harengus harengus) Can. J. Zool. 1990;68:1652–1658. doi: 10.1139/z90-245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hayes P.H., Scott G., Ng N., Hew C., Davies P. Cystine-rich type ii antifreeze protein precursor is initiated from the third aug codon of its mrna. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:18761–18767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Graham L.A., Lougheed S.C., Ewart K.V., Davies P.L. Lateral transfer of a lectin-like antifreeze protein gene in fishes. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2616. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sorhannus U. Evolution of type ii antifreeze protein genes in teleost fish: A complex scenario involving lateral gene transfers and episodic directional selection. Evol. Bioinform. Online. 2012;8:535–544. doi: 10.4137/EBO.S9976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Briggs J.C. Marine centres of origin as evolutionary engines. J. Biogeogr. 2003;30:1–18. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2699.2003.00810.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cziko P.A., Evans C.W., Cheng C.H., DeVries A.L. Freezing resistance of antifreeze-deficient larval antarctic fish. J. Exp. Biol. 2006;209:407–420. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Desjardins M., Graham L.A., Davies P.L., Fletcher G.L. Antifreeze protein gene amplification facilitated niche exploitation and speciation in wolffish. FEBS J. 2012;279:2215–2230. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jung A., Johnson P., Eastman J., DeVries A. Protein content and freezing avoidance properties of the subdermal extracellular matrix and serum of the antarctic snailfish, Paraliparis devriesi. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 1995;14:71–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00004292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DeMartini E.E. Spatial aspects of reproduction in buffalo sculpin, Enophrys bison. Environ. Biol. Fishes. 1978;3:331–336. doi: 10.1007/BF00000524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Munehara H. Utilization of polychaete tubes as spawning substrate by the sea raven Hemitripterus villosus (scorpaeniformes) Environ. Biol. Fishes. 1992;33:395–398. doi: 10.1007/BF00010953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Markevich A. Spawning of the sea Ravenhemitripterus villosus in peter the great bay, Sea of Japan. Russ. J. Mar. Biol. 2000;26:283–285. doi: 10.1007/BF02759509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mandic M., Ramon M.L., Gracey A.Y., Richards J.G. Divergent transcriptional patterns are related to differences in hypoxia tolerance between the intertidal and the subtidal sculpins. Mol. Ecol. 2014;23:6091–6103. doi: 10.1111/mec.12991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Near T.J., Dornburg A., Eytan R.I., Keck B.P., Smith W.L., Kuhn K.L., Moore J.A., Price S.A., Burbrink F.T., Friedman M., et al. Phylogeny and tempo of diversification in the superradiation of spiny-rayed fishes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:12738–12743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304661110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Møller P.R., Gravlund P. Phylogeny of the eelpout genus lycodes (pisces, zoarcidae) as inferred from mitochondrial cytochrome b and 12s rdna. Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 2003;26:369–388. doi: 10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00362-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kontula T., Väinölä R. Relationships of palearctic and nearctic ‘glacial relict’ Myoxocephalus sculpins from mitochondrial DNA data. Mol. Ecol. 2003;12:3179–3184. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.