Highlights

-

•

Greater physical activity is related to better health-related quality of life, being moderate-to-vigorous the intensity of physical activity that presented the strongest associations.

-

•

The time spent in sedentary behaviours is negatively related to health-related quality of life, independently of the level of physical activity of these patients.

-

•

Women with fibromyalgia that accomplish the physical activity recommendations (at least 150 min/week of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity) present better scores in bodily pain and social function domains.

Keywords: Accelerometry, GT3X+, Mental health, Physical health

Abstract

Purpose

To examine the association of physical activity (PA) intensity levels and sedentary time with health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in women with fibromyalgia and whether patients meeting the current PA guidelines present better HRQoL.

Methods

This cross-sectional study included 407 women with fibromyalgia aged 51.4 ± 7.6 years. The time spent (min/day) in different PA intensity levels (light, moderate, and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) and sedentary time were measured with triaxial accelerometry. The proportion of women meeting the American PA recommendations (≥150 min/week of MVPA in bouts ≥10 min) was also calculated. HRQoL domains (physical function, physical role, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, emotional role, and mental health), as well as physical and mental components, were assessed using the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey.

Results

All PA intensity levels were positively correlated with different HRQoL dimensions (rpartial between 0.10 and 0.23, all p < 0.05). MVPA was independently associated with social functioning (p < 0.05). Sedentary time was independently associated with physical function, physical role, bodily pain, vitality, social functioning, and both the physical and mental component summary score (all p < 0.05). Patients meeting the PA recommendations presented better scores for bodily pain (mean = 24.2 (95%CI: 21.3–27.2) vs. mean = 20.4 (95%CI: 18.9–21.9), p = 0.023) and better scores for social functioning (mean = 48.7 (95%CI: 43.9–44.8) vs. mean = 42.3 (95%CI: 39.8–44.8), p = 0.024).

Conclusion

MVPA (positively) and sedentary time (negatively) are independently associated with HRQoL in women with fibromyalgia. Meeting the current PA recommendations is significantly associated with better scores for bodily pain and social functioning. These results highlight the importance of being physically active and avoiding sedentary behaviors in this population.

1. Introduction

Fibromyalgia is a chronic condition with persistent and widespread pain along with other symptoms such as fatigue, nonrestorative sleep, and cognitive difficulties.1 These factors have a considerable negative impact on the patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL),2 which represents the individuals' perception of physical, mental, and social health status. Because fibromyalgia has no cure, treatment is usually focused on improving HRQoL along with symptomatology management.

Physical exercise has been shown to be an alternative to pharmacologic treatments in fibromyalgia,3 yet adherence to exercise programs is challenging.4 Modifying daily physical activity (PA) might potentially be a more sustainable behavior over time. Previous studies have observed a positive association between PA and HRQoL both in the general population5, 6 and among those with fibromyalgia.7, 8 Nonetheless, fear of pain and worsening of symptoms lead patients to avoid PAs,9 and only 20% of them seem to meet the American PA recommendations.10, 11 The fulfillment of these PA recommendations for the general population has been related to a higher cardiovascular risk in fibromyalgia,12 but it is unclear whether this may also extend to other health outcomes, such as HRQoL. In similar conditions, such as arthritis, those patients meeting the PA recommendations for arthritis13 or the general population14 presented a better HRQoL. The intensity and dose of PA to elicit disease-specific benefits in fibromyalgia is yet to be defined. Previous research studying the influence of PA on health of these patients is mainly focused on symptoms15, 16, 17, 18 or physical domains of HRQoL outcomes.8, 19,20 Therefore, the extent to which different PA intensity levels (e.g., light, moderate, or vigorous) are associated with all domains of HRQoL and which of them is the best indicator of current HRQoL are currently unknown.

Sedentary behaviors, which include activities that involve sitting or reclining and demand only low levels of energy expenditure,21 have negative consequences on health independent of those behaviors related to insufficient PA.22 For instance, sedentary time is linked to lower HRQoL in the general population.6, 23 Patients with fibromyalgia spend more time of their waking time in sedentary behaviors (on average, 48%) than do healthy individuals.11 Hence, it is of major clinical and public health interest to assess the extent to which sedentary time is associated with HRQoL in patients with fibromyalgia because preventing prolonged sedentary behaviors might be advisable.

A detailed characterization of how different PA intensity levels and sedentary time are related to diverse domains of HRQoL would provide valuable information for the design of prospective studies and specific PA recommendations for this group of patients. Therefore, the aims of the current study were to test (1) the association of objectively measured PA intensity levels (i.e., light, moderate, and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) and sedentary time with HRQoL in women with fibromyalgia, (2) whether different PA intensity levels and sedentary time are independently associated with HRQoL among these patients, and (3) and whether patients meeting the current American PA guidelines present better HRQoL than those not meeting the PA guidelines. We hypothesized that (1) all PA intensity levels (positively) and sedentary time (negatively) are associated with HRQoL in women with fibromyalgia, (2) PA and sedentary time are independently associated with HRQoL among these patients, and (3) patients who meet the current American PA guidelines present better HRQoL than those not meeting the PA guidelines.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

A province-proportional recruitment of patients with fibromyalgia from southern Spain (Andalusia) was planned, as described elsewhere.24 Briefly, patients were contacted through fibromyalgia associations, email, and social media. After providing detailed information about the aims and study procedures, we obtained written informed consent from all study participants. A total of 646 patients with fibromyalgia agreed to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria for the current study were (1) to have neither acute nor terminal illness nor severe cognitive impairment (Mini-Mental State Examination25 score <10), (2) to be ≤65 years old, and (3) to be previously diagnosed by a rheumatologist and meet the official 1990 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) fibromyalgia criteria (widespread pain >3 months and pain with ≤4 kg/cm2 of pressure reported for ≥11 of 18 tender points).26 The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Virgen de las Nieves, Granada (Spain).

2.2. Procedures

On Day 1 of the study, the Mini-Mental State Examination was administered and participants filled out the modified 2010 ACR preliminary criteria, self-reported sociodemographic data, and drug consumption questionnaires. Tender points, anthropometry, and body composition were also assessed. The 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36)27 was given to patients to be completed at home. Two days later, patients returned to the laboratory, where questionnaires were collected and checked by the researchers. After that, participants received instructions on how to complete the sleep diary and the accelerometers were provided. The accelerometers and sleep diaries were returned to the research team 9 days later.

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Sociodemographic data and drug consumption

We collected sociodemographic data by using a self-reported questionnaire including date of birth, marital status (married/not married), educational level (university/nonuniversity), and occupational status (working/not working). Additionally, to assess an exclusion criterion, participants were asked: “Have you ever been diagnosed with an acute or terminal illness?” Furthermore, patients reported the consumption of antidepressants and analgesics (yes/no) during the previous 2 weeks.

2.3.2. PA levels and sedentary time

Patients were asked to wear a triaxial accelerometer GT3X+ (Actigraph, Pensacola, FL, USA) for 9 days during the whole day (24 h) except during water-based activities. The device was worn around the hip, secured with an elastic belt underneath clothing. Data were collected at a rate of 30 Hz and at an epoch length of 60 s, in concordance with the cut-points validation studies.28, 29 PA from the 9 consecutive days was recorded, although data from the first day (to avoid reactivity) and the last day (device return) were excluded from the analysis. Bouts of 90 continuous minutes (allowance of 2-min interval of nonzero counts with the up-/downstream 30-min consecutive 0 count window for detection of artifactual movements) of 0 count were considered nonwear periods30 and were excluded as well. In agreement with prior literature,31 7 continuous days in total with a minimum of 10 valid hours was required to be included in the analysis. Data download, reduction, cleaning, and analyses were conducted using the manufacturer software ActiLife Version 6.11.7 (Actigraph). Accelerometer wear time was calculated by subtracting the sleeping time (obtained from the sleep diary, in which patients indicated the time they went to bed and the time they woke up) from each day. Sedentary time was estimated as the time accumulated below 200 counts/min during periods of wear time.28 PA intensity levels (light PA, moderate PA, vigorous PA, and MVPA) were calculated based on recommended PA vector magnitude cut-points:29 200–2689, 2690–6166, ≥6167, and ≥2690 counts/min, respectively. All values were expressed in min/day. We calculated the proportion of women meeting the American PA recommendations for adults aged 18–64 years (≥150 min/week of MVPA for ≥10 min at a time).10

2.3.3. HRQoL

HRQoL was evaluated using the SF-36. This questionnaire has been validated for Spanish populations.27 The SF-36 is composed of 36 items that assess 8 dimensions of health (i.e., physical functioning, physical role, bodily pain, general health, social functioning, emotional role, mental health, and vitality) and 2 component summary scores (i.e., physical and mental health). The score in each dimension is standardized and ranges from 0 (worst health status) to 100 (best health status).

2.3.4. Tenderness and diagnostic criteria

Following the 1990 ACR criteria for classification of fibromyalgia,26 we assessed 18 tender points using a standard pressure algometer (FPK 20; Wagner Instruments, Greenwich, CT, USA). We obtained the mean pressure of 2 measurements at each tender point. A tender point was considered positive when the patient felt pain at pressure ≤4 kg/cm2. The total number of positive tender points was recorded for each patient. Because different diagnoses for fibromyalgia currently coexist, we also complementarily used the modified 2010 ACR preliminary diagnosis criteria32, 33, 34 (description in the supplementary material) to understand potential discrepancies owing to the patients’ classifications.

2.3.5. Anthropometry and body composition

Weight (kg) and total body fat percentage was assessed using a portable 8-polar tactile-electrode bioelectrical impedance device (InBody R20; Biospace, Seoul, Republic of Korea). The validity and reliability of this instrument have been reported elsewhere.35, 36 As the manufacturer recommends, we requested participants not to have a shower, not to practice intense PA, and not to ingest large amounts of fluid and/or food in the 2 h before the measurement. Patients were also asked not to wear either clothing (except underwear) or metal objects during the measurement. A stadiometer (Seca 22; Seca Gmbh, Hamburg, Germany) was used to measure height (cm), and body mass index was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m) squared.

2.4. Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample. Participants presented extremely low values of vigorous PA (0.4 min/day); therefore, vigorous PA was excluded from all analyses. In preliminary analyses, bivariate correlations were used to explore the role of different variables related to physical, social, and psychological factors that have been shown to determine HRQoL in patients with fibromyalgia.37 As a result, age, marital status, education level, current occupational status, total body fat percentage, and drug consumption (both analgesics and antidepressants) were identified as potential confounders and were introduced in all analyses along with total accelerometer wear time. Partial correlation was used to study the individual association of the different PA levels (light PA, moderate PA, and MVPA) and sedentary time with HRQoL (Objective 1) while controlling for all aforementioned covariates. Then, to explore the independent association of PA intensity levels and sedentary time with HRQoL (Objective 2), linear regression analyses were conducted. All dimensions of HRQoL (physical functioning, physical role, bodily pain, general health, social functioning, emotional role, mental health, and vitality) and the physical and mental component summary scores (assessing physical and mental health) were entered as dependent variables in separate models. All PA intensity levels (except vigorous PA), sedentary time, and all covariates (sociodemographic variables, drug consumption, and total body fat percentage) were entered simultaneously using a forward stepwise procedure based on the exploratory nature of these analyses. Moreover, a stepwise procedure was used because the aim was to observe the best indicator of HRQoL among the PA variables (i.e., the PA variables that presented the strongest associations). This procedure introduces the variables step by step into the model (if p < 0.05) according to the strength of the association with the outcome. The model is reassessed with the addition of every new variable, and variables are left out of the model if p > 0.10. Accelerometer wear time was introduced with the “enter” procedure to control all analyses for its effect. Normal probability plots of the standardized residual and scatterplots of residuals were generated to test normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity. The nonautocorrelation assumption was also met (Durbin-Watson test; 1.5 < d < 2.5 for all regression models). No serious multicollinearity problems among the predictor variables of the model were found (all variance inflation factor statistics <10.0).

Differences in HRQoL of patients meeting vs. not meeting the current PA guidelines (≥150 min/week of MVPA in bouts of ≥10 min; Objective 3) were calculated with multivariate analysis of covariance. The 8 dimensions and the 2 component summary scores of HRQoL were entered as dependent variables, and sociodemographic variables, total body fat percentage, drugs consumption, and accelerometer wear time were entered as covariates.

Normality was assumed owing to the large sample size and the homoscedasticity assumption of HRQoL (assessed with the Levene test) was reasonably met between patients’ meeting vs. not meeting recommendations of PA. All analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences SPSS Version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The level of significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

A total of 39 women with fibromyalgia were not previously diagnosed, 99 did not meet the 1990 ACR criteria, 1 had severe cognitive impairment, and 14 did not meet the age criteria. Men with fibromyalgia were not included in the current study owing to the small sample (n = 21). A total of 17 participants did not agree to wear the accelerometer, and data from 3 participants were lost owing to accelerometer malfunction. A total of 17 participants did not meet the accelerometer criteria (insufficient wear time or incomplete sleep diaries), and 28 did not return completed questionnaires. The final sample size included in the analysis was 407 women with fibromyalgia. Patients’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants (n = 407).

| Variable | Mean ± SD or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (year) | 51.4 ± 7.6 |

| Total tender points (11–18) | 16.7 ± 2.0 |

| Algometer score (18–144) | 43.2 ±13.4 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.4 ± 5.4 |

| Total body fat (%) | 40.1 ±7.6 |

| HRQoL, SF-36 (0–100) | |

| Physical functioning | 39.2 ± 18.9 |

| Physical role | 33.2 ± 21.2 |

| Bodily pain | 21.2 ± 14.7 |

| General health | 28.5 ± 15.3 |

| Vitality | 22.3 ± 17.7 |

| Social functioning | 43.7 ± 24.7 |

| Emotional role | 56.9 ± 27.9 |

| Mental health | 46.2 ± 19.7 |

| Physical component | 29.5 ± 6.9 |

| Mental component | 36.0 ± 11.6 |

| PA and sedentary behavior (min/day) | |

| Accelerometer wear time | 923.0 ± 78.9 |

| Sedentary time | 460.1 ± 104.1 |

| Light PA | 418.6 ± 91.8 |

| Moderate PA | 43.9 ± 29.5 |

| Vigorous PA | 0.4 ± 2.0 |

| MVPA | 44.3 ± 30.1 |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 311 (76.4) |

| Not married | 96 (23.6) |

| Education level | |

| Nonuniversity | 349 (85.7) |

| University | 58 (14.3) |

| Current occupational status | |

| Working | 107 (26.3) |

| Not working | 300 (73.7) |

| Drug consumption | |

| Analgesics | 367 (90.2) |

| Antidepressants | 232 (57.0) |

| PA recommendations | |

| Meet PA recommendations | 86 (21.1) |

| Not meet PA recommendations | 321 (78.9) |

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; HRQoL = health-related quality of life; MVPA = moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; PA = physical activity; SF-36 = 36-item Short-Form Health Survey.

Partial correlations of PA intensity levels and sedentary time with HRQoL are presented in Table 2. Light PA was significantly associated with physical functioning, bodily pain, vitality, and social functioning (rpartial between 0.11 and 0.20, all p ≤ 0.05). Moderate PA and MVPA were both significantly associated with physical functioning, physical role, vitality, social functioning, and physical component (rpartial between 0.10 and 0.22, all p ≤ 0.05). Sedentary time was inversely associated with all dimensions of HRQoL (rpartial between –0.24 and –0.11, all p ≤ 0.05), except for general health, emotional role, and mental health.

Table 2.

Partial correlations of PA intensity levels and sedentary behavior with HRQoL (n = 407).

| Variable | Light PA | Moderate PA | MVPA | Sedentary time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | 0.11⁎ | 0.11⁎ | 0.12⁎ | –0.13⁎⁎ |

| Physical role | 0.08 | 0.12⁎ | 0.12⁎ | –0.11⁎ |

| Bodily pain | 0.11* | 0.08 | 0.09 | –0.13⁎⁎ |

| General health | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | –0.04 |

| Vitality | 0.13⁎⁎ | 0.13⁎⁎ | 0.13⁎⁎ | –0.15⁎⁎ |

| Social functioning | 0.20⁎⁎⁎ | 0.22⁎⁎⁎ | 0.22⁎⁎⁎ | –0.24⁎⁎⁎ |

| Emotional role | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.04 | –0.07 |

| Mental health | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | –0.04 |

| Physical component | 0.09 | 0.10⁎ | 0.10⁎ | –0.11⁎ |

| Mental component | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 | –0.11⁎ |

Notes: Analyses are controlled for age, total body fat percentage, current occupational status, education level, marital status, accelerometer wear time, and consumption of analgesics and antidepressants.

Abbreviations: HRQoL = health-related quality of life; MVPA = moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; PA = physical activity.

p ≤ 0.05,

p ≤ 0.01,

p ≤ 0.001.

The regression model between PA intensity levels and sedentary time, and SF-36 dimensions, as well as the physical and mental health component summary score (physical and mental health), are shown in Table 3. MVPA was the only PA intensity level independently associated with HRQoL, specifically with social functioning (b = 0.10, p = 0.037). Sedentary time was independently associated with physical functioning (b = –0.03), physical role (b = –0.03), bodily pain (b = –0.02), vitality (b = –0.03), social functioning (b = –0.05), and the physical (b = –0.01) and mental (b = –0.01) component summary score (all p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Models of regression coefficients assessing the association of PA intensity levels and sedentary time with HRQoL (n = 407).

| β | b | 95%CI | p | Adjusted R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | 0.063 | ||||

| Accelerometer wear time | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.01 to 0.06 | 0.002 | |

| Medication for depression | –0.14 | –5.29 | –9.00 to –1.57 | 0.005 | |

| Sedentary time | –0.18 | –0.03 | –0.05 to –0.01 | 0.001 | |

| Physical role | 0.134 | ||||

| Accelerometer wear time | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.01 to 0.06 | 0.009 | |

| Not working | –0.2 | –9.75 | –14.24 to –5.25 | <0.001 | |

| Medication for depression | –0.20 | –8.46 | –12.47 to –4.46 | <0.001 | |

| Sedentary time | –0.14 | –0.03 | –0.05 to –0.01 | 0.006 | |

| Bodily pain | 0.143 | ||||

| Accelerometer wear time | 0.07 | 0.01 | –0.01 to 0.03 | 0.177 | |

| Total body fat percentage | –0.10 | –0.20 | –0.38 to –0.02 | 0.031 | |

| Medication for depression | –0.31 | –9.09 | –11.86 to –6.32 | <0.001 | |

| Sedentary time | –0.16 | –0.02 | –0.04 to –0.01 | 0.003 | |

| General health | 0.086 | ||||

| Accelerometer wear time | 0.04 | 0.01 | –0.01 to 0.03 | 0.461 | |

| Not working | –0.11 | –3.64 | –6.95 to –0.32 | 0.032 | |

| Medication for depression | –0.24 | –7.39 | –10.33 to –4.45 | <0.001 | |

| Medication for pain | –0.10 | –4.87 | –9.73 to –0.02 | 0.042 | |

| Vitality | 0.092 | ||||

| Accelerometer wear time | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.00 to 0.05 | 0.041 | |

| Medication for depression | –0.20 | –7.15 | –10.60 to –3.70 | <0.001 | |

| Medication for pain | –0.09 | –5.58 | –11.14 to –0.01 | 0.049 | |

| Sedentary time | –0.18 | –0.03 | –0.05 to –0.01 | 0.001 | |

| Social functioning | 0.215 | ||||

| Accelerometer wear time | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.01 to 0.08 | 0.005 | |

| Age | 0.10 | 0.34 | 0.05 to 0.63 | 0.021 | |

| Medication for depression | –0.28 | –14.03 | –18.50 to –9.55 | <0.001 | |

| Medication for pain | –0.10 | –8.26 | –15.50 to –1.01 | 0.026 | |

| MVPA | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.01 to 0.18 | 0.037 | |

| Sedentary time | –0.21 | –0.05 | –0.08 to –0.02 | <0.001 | |

| Emotional role | 0.161 | ||||

| Accelerometer wear time | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.01 to 0.07 | 0.014 | |

| Not working | –0.13 | –8.04 | –13.82 to –2.27 | 0.006 | |

| Medication for depression | –0.34 | –19.32 | –24.40 to –14.24 | <0.001 | |

| Mental health | 0.143 | ||||

| Accelerometer wear time | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.00 to 0.05 | 0.048 | |

| Medication for depression | –0.36 | –14.391 | –18.00 to –10.78 | <0.001 | |

| Physical component summary | 0.048 | ||||

| Accelerometer wear time | 0.08 | 0.01 | –0.00 to 0.02 | 0.149 | |

| Not working | –0.14 | –2.24 | –3.77 to –0.71 | 0.004 | |

| Sedentary time | –0.17 | –0.01 | –0.02 to 0.00 | 0.001 | |

| Mental component summary | 0.193 | ||||

| Accelerometer wear time | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.01 to 0.04 | 0.002 | |

| Medication for depression | –0.37 | –8.59 | –10.73 to –6.45 | <0.001 | |

| Medication for pain | –0.09 | –3.65 | –7.11 to –0.20 | 0.038 | |

| Sedentary time | –0.12 | –0.01 | –0.02 to 0.00 | 0.018 |

Notes: Forward stepwise regression using age, marital status, education level, current occupational status, consumption of analgesics and antidepressants, total body fat percentage, light PA, MVPA, and sedentary time. Accelerometer wear time was used as a covariate (enter method) in all models. PA levels and sedentary time are highlighted in bold.

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; HRQoL = health-related quality of life; MVPA = moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; PA = physical activity.

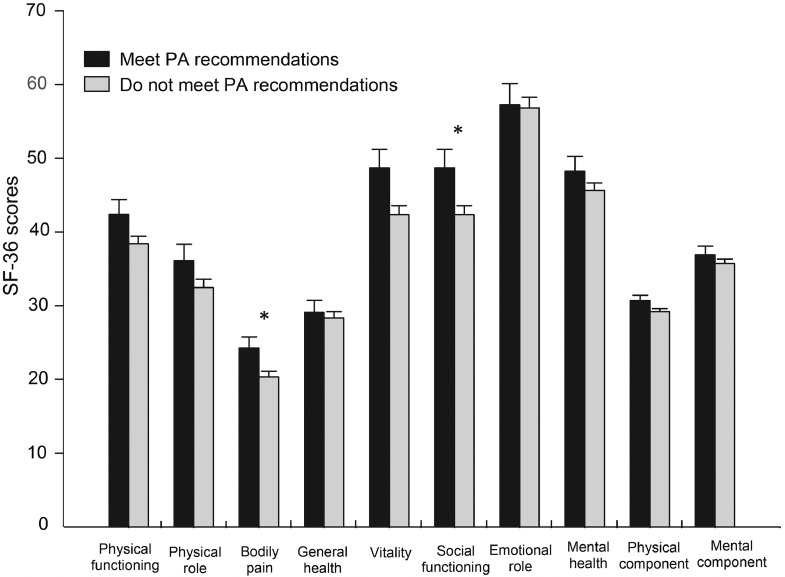

Fig. 1 shows the differences in the dimensions of HRQoL in women with fibromyalgia meeting (n = 86) vs. not meeting (n = 321) the current American PA recommendations. Multivariate analysis of covariance analysis showed no significant differences between the 2 groups for global HRQoL (Hottelling T2: F(8, 391) = 0.027; p = 0.239). In further analysis for each dimension, patients who met the current PA recommendations presented better scores in bodily pain (95% confidence interval (CI): 21.3–27.2 vs. 18.9–21.9; p = 0.023) and social functioning (95%CI: 43.9–44.8 vs. 39.8–44.8; p = 0.024) dimensions than those who did not meet the current PA recommendations.

Fig. 1.

Means (95% confidence interval) of scores on the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) for each dimension in patients meeting (n = 86) and not meeting (n = 321) the current physical activity (PA) recommendations. Differences between groups were studied using multivariable analysis of covariance with sociodemographic variables (marital status, occupational status, and education level), total body fat percentage, drug consumption, and accelerometer wear time entered as covariates, Hottelling T2: F (8, 391) = 0.027; p = 0.239. *p < 0.05.

The supplementary material includes a replication of all analyses using the modified 2010 ACR preliminary criteria for diagnosis. Overall, both analyses showed similar results except for a lack of association between sedentary time and physical role, bodily pain, and mental health component when using the modified 2010 ACR criteria.

4. Discussion

The current study showed that light PA and MVPA (positively) and sedentary time (negatively) are associated with different dimensions of HRQoL in women with fibromyalgia. MVPA intensity level and sedentary time were independently associated with HRQoL dimensions (except for general health, emotional role, and mental health). Participants meeting the current PA recommendations showed better scores in bodily pain and social functioning dimensions of HRQoL than those not meeting the current PA recommendations. Our findings suggest that patients with fibromyalgia should be encouraged to reduce sedentary time and increase their PA levels.

Diverse intervention studies have suggested that PA is effective for improving symptomatology and HRQoL in patients with fibromyalgia.18, 19, 20 However, as far as we know, only 2 previous studies have tested the link between total PA and patients’ perception of health status.7, 8 Sañudo et al.7 found that patients who reported a moderate level of total PA presented better physical function and general health. Culos-Reed and Brawley8 also found evidence that the physical component of HRQoL was independently related with a higher frequency of total PA. Overall, our results concur with previous research, but this is the first study supporting the relation of PA with HRQoL using objective measurements of PA in a large and geographically representative sample of women with fibromyalgia. The specific relationship between PA intensity levels and HRQoL in the general populations remains controversial. Although some studies have shown that the regular participation in high-intensity levels of PA is related to better HRQoL in women,38 others studies have suggested that participation in high-intensity PA for extended periods might result in poorer HRQoL.39 In the present study, when PA intensity levels were studied individually, we observed that light, moderate, and MVPA were correlated with different domains of HRQoL. However, MVPA was the only PA intensity level that showed significant associations with HRQoL, independent of light PA and sedentary time. This finding agrees with recommendations to increase MVPA levels to promote health improvements.10 Complementing prior literature demonstrating that increasing time in MVPA was effective to reduce fibromyalgia impact,18 our results also demonstrated that greater time in MVPA is related to less interference with social activities owing to health status.

In line with prior studies in patients with arthritis,13, 14 we observed that patients who met the PA recommendations had overall better HRQoL, although multivariable analysis of covariance analyses only showed significant differences in the bodily pain and social function domains. Accumulating MVPA for a reduced reported pain partially contrasts with previous studies showing the beneficial role of PA of low and moderate intensity for pain modulation,16 interference,20 and intensity19 in patients with fibromyalgia. However, it is also noteworthy that light PA was the only PA intensity level associated with better scores in the bodily pain domain in the correlation analyses. Therefore, although a link between PA and pain seems to exist,40 the differences in accelerometry devices, cut-points, and tools to assess pain might partly explain the discrepancies when establishing an adequate intensity of PA to promote pain benefits.

The relationship found in the present study between PA and HRQoL is complex and might be explained through intermediate factors. Self-efficacy can be considered a consequence of PA but might also be a potential mediator between PA and HRQoL.41 Positive changes in others’ constructs related to mental health (depression, fatigue, social support, mood,42 affect, or self-esteem43) have been suggested to mediate in the pathway between PA and HRQoL in previous population-based studies as well. More closely related to the physical component, participation in PA tends to be associated with benefits such as reduction of cardiovascular risk factors,12 improved sleep quality, improved fitness level, and reduced functional limitations.10 Although this indirect relationship has been grounded theoretically in previous research, the intermediate role of the aforementioned factors among patients with fibromyalgia is yet to be elucidated.

This study also fills a gap in the literature by evidencing an inverse relationship of objectively measured sedentary time with HRQoL independent of PA in women with fibromyalgia. The strongest association of sedentary time was observed with the social function dimension. The passive nature of different sedentary activities (e.g., watching television or sitting at the computer) is thought to be accompanied by decreased communication and poor social networking.44 Because social isolation concerns are frequently reported by these patients, preventing prolonged sedentary activities and moving toward a less sedentary lifestyle may positively influence this construct of health. Mechanisms that explain the deleterious relationship of sedentary behavior and HRQoL have been less studied than those identified with PA. Nevertheless, some adaptations negatively related to the mental component of HRQoL, such as stress, anxiety, depression, and mental disorders, have been connected to sustained sedentary time.23 Impaired pain regulation related to sedentary behavior15 could additionally explain detriments in patients’ reported health status. Furthermore, prolonged sedentary time compromises cardiometabolic health, leading to increased cardiovascular risk, hypertension, and diabetes.22 The fact that sedentary behavior is higher in patients with fibromyalgia,9 added to the association found between sedentary time and HRQoL independent of PA, displays the importance of this behavior as a target for health promotion efforts in these patients. Therefore, motivating women with fibromyalgia to become less sedentary seems to be a valuable strategy, because this behavior would likely result in increases in light PA behaviors, which also presented positive correlations with HRQoL in the current study, as well as overall symptoms in previous studies.15, 19,45

The absence of a gold standard to identify fibromyalgia makes the evaluation of the disease difficult and controversial. Since the first diagnosis was released in 1990,26 this criterion has been widely used in prior literature and remains the current official criteria for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia. A new understanding of the concept of fibromyalgia arose with the modified ACR 2010 criteria,32 giving greater emphasis to symptoms and dropping the tender point assessment from 1990. The 2011 criteria have some limitations, however, such as the misclassification of patients who do not have generalized pain but have regional pain syndromes.46 It is therefore possible that using different diagnostic criteria changes the fibromyalgia case definitions and consequently might imply slight modifications in study results. To understand the robustness of our results across different classification criteria, the modified 2010 criteria (see the supplementary material) were also used. In our analyses, changes in results related to physical role and bodily pain dimensions, as well as the mental health component, were observed, resulting in a lack of association (but having borderline significance) when using the modified 2010 criteria. These discrepancies were expected because the 2010 symptom severity scale is closely related to those dimensions of health by assessing difficulty in thinking or remembering, pain or cramps in the lower abdomen, depression, and headache.

The present study has some limitations that must be acknowledged. Because our results are derived from a cross-sectional study, the associations found cannot be explained via a causal pathway: although PA might improve HRQoL, it is possible that individuals with impaired HRQoL are less likely to participate in PA behavior. Additionally, owing to the large number of factors related to HRQoL, it is difficult to ascertain the true association between PA intensity levels and sedentary time with HRQoL. Given that only women took part in this study, future studies should investigate whether these associations also occur in men. Despite these limitations, this study has several strengths, including the use of accelerometers, which allowed us to objectively quantify intensities of PA and time spent in sedentary activities. Furthermore, we assessed a relatively large sample size of women with fibromyalgia who were representative of southern Spain (Andalusia).24 We also attempted to enhance the robustness of our analyses by adjusting for a reasonable number of potential confounders.

5. Conclusion

This study shows that all PA intensity levels (positively) and sedentary time (negatively) were individually correlated with better scores in different domains of HRQoL. However, among the different PA intensity levels, only MVPA shows an independent association with HRQoL, specifically with the social functioning domain. Moreover, patients who meet the American PA recommendations present significantly better scores in bodily pain and social functioning domains. Interestingly, sedentary time is also independently and inversely associated with the physical functioning, physical role, bodily pain, vitality, social functioning, physical component, and mental component dimensions of HRQoL. The effects on HRQoL of strategies aimed at reducing sedentary time, which results in greater light PA and eventually leads to engagement in MVPA among this population, need to be further evaluated.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank all the members involved in the fieldwork, especially members from CTS-1018 research group. We also gratefully acknowledge all study participants for their collaboration. This study was supported by the Spanish Ministries of Economy and Competitiveness (I+D+i DEP2010-15639; I+D+I DEP2013-40908-R, BES-2014-067612) and the Spanish Ministry of Education (FPU 13/01088; FPU 15/00002).

Authors’ contributions

BGC carried out the analysis and the interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript; VSJ contributed to study conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafted the manuscript; FEL contributed to study conception and design, acquisition of data, and drafted the manuscript; ICAG contributed to study conception and design, acquisition of data, and drafted the manuscript; ASM contributed to study conception and design, acquisition of data, and drafted the manuscript; MBC, MHC, and PAM contributed to acquisition of data and drafted the manuscript; MDF contributed to study conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript, and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2018.07.001.

Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Rahman A, Underwood M, Carnes D. Fibromyalgia. BMJ. 2014;348:g1224. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verbunt JA, Pernot DH, Smeets RJ. Disability and quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macfarlane GJ, Kronisch C, Dean LE, Atzeni F, Häuser W, Flub E. EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:318–328. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones KD, Liptan GL. Exercise interventions in fibromyalgia: clinical applications from the evidence. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009;35:373–391. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bize R, Johnson JA, Plotnikoff RC. Physical activity level and health-related quality of life in the general adult population: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2007;45:401–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies CA, Vandelanotte C, Duncan MJ, van Uffelen JGZ. Associations of physical activity and screen-time on health related quality of life in adults. Prev Med. 2012;55:46–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sañudo JI, Corrales-Sánchez R, Sañudo B. Physical activity levels, quality of life and incidence of depression in older women with Fbromyalgia (Nivel de actividad física, calidad de vida y niveles de depresión en mujeres mayores con Fbromialgia) Escritos Psicol. 2013;6:53–60. [in Spanish] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Culos-Reed SN, Brawley LR. Fibromyalgia, physical activity, and daily functioning: the importance of efficacy and health-related quality of life. Arthritis Care Res. 2000;13:343–351. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200012)13:6<343::aid-art3>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nijs J, Roussel N, Van Oosterwijck J, De Kooning M, Ickmans K, Struyf F. Fear of movement and avoidance behaviour toward physical activity in chronic-fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia: state of the art and implications for clinical practice. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:1121–1129. doi: 10.1007/s10067-013-2277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee . U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2008. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee report, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Segura-Jimenez V, Alvarez-Gallardo IC, Estevez-Lopez F, Soriano-Maldonado A, Delgado-Fernandez M, Ortega FB. Differences in sedentary time and physical activity between female patients with fibromyalgia and healthy controls: the al-Andalus project. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:3047–3057. doi: 10.1002/art.39252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acosta-Manzano P, Segura-Jiménez V, Estévez-López F, Álvarez-Gallardo IC, Soriano-Maldonado A, Borges-Cosic M. Do women with fibromyalgia present higher cardiovascular disease risk profile than healthy women? The al-Andalus project. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017;35:61–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Austin S, Qu H, Shewchuk RM. Association between adherence to physical activity guidelines and health-related quality of life among individuals with physician-diagnosed arthritis. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:1347–1357. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abell JE, Hootman JM, Zack MM, Moriarty D, Helmick CG. Physical activity and health related quality of life among people with arthritis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:380–385. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.028068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellingson LD, Shields MR, Stegner AJ, Cook DB. Physical activity, sustained sedentary behavior, and pain modulation in women with fibromyalgia. J Pain. 2012;13:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLoughlin MJ, Stegner AJ, Cook DB. The relationship between physical activity and brain responses to pain in fibromyalgia. J Pain. 2011;12:640–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Segura-Jimenez V, Borges-Cosic M, Soriano-Maldonado A, Estevez-Lopez F, Alvarez-Gallardo IC, Herrador-Colmenero M. Association of sedentary time and physical activity with pain, fatigue, and impact of fibromyalgia: the al-Andalus study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2017;27:83–92. doi: 10.1111/sms.12630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaleth AS, Saha CK, Jensen MP, Slaven JE, Ang DC. Moderate-vigorous physical activity improves long-term clinical outcomes without worsening pain in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65:1211. doi: 10.1002/acr.21980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fontaine KR, Conn L, Clauw DJ. Effects of lifestyle physical activity on perceived symptoms and physical function in adults with fibromyalgia: results of a randomized trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R55. doi: 10.1186/ar2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaleth AS, Slaven JE, Ang DC. Does increasing steps per day predict improvement in physical function and pain interference in adults with fibromyalgia? Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66:1887–1894. doi: 10.1002/acr.22398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barnes J, Behrens TK, Benden ME, Biddle S, Bond D, Brassard P. Letter to the editor: standardized use of the terms “sedentary” and “sedentary behaviours”. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab Appl Nutr Metab. 2012;37:540–542. doi: 10.1139/h2012-024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Owen N, Healy GN, Matthews CE, Dunstan DW. Too much sitting: the population-health science of sedentary behavior. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2010;38:105. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e3181e373a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellingson LD, Kuffel AE, Cook DB. Active and sedentary behavior patterns predict mental health and quality of life in healthy women: 2885. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2011;43(Suppl. 1):S817. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Segura-Jiménez V, Álvarez-Gallardo IC, Carbonell-Baeza A, Aparicio VA, Ortega FB, Casimiro AJ. Fibromyalgia has a larger impact on physical health than on psychological health, yet both are markedly affected: the al-Andalus project. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;44:563–570. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:160–172. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alonso J, Prieto L, Anto JM. The Spanish version of the SF-36 Health Survey (the SF-36 health questionnaire): an instrument for measuring clinical results. Med Clin (Barc) 1995;104:771–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aguilar-Farías N, Brown WJ, Peeters GM. ActiGraph GT3X+ cut-points for identifying sedentary behaviour in older adults in free-living environments. J Sci Med Sport. 2014;17:293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sasaki JE, John D, Freedson PS. Validation and comparison of ActiGraph activity monitors. J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14:411–416. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi L, Ward SC, Schnelle JF, Buchowski MS. Assessment of wear/nonwear time classification algorithms for triaxial accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:2009–2016. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318258cb36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:181–188. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Katz RS, Mease P. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:600–610. doi: 10.1002/acr.20140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles M, Don L, Häuser W, Katz RS. Fibromyalgia criteria and severity scales for clinical and epidemiological studies: a modification of the ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:1113–1122. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Segura-Jiménez V, Aparicio VA, Álvarez-Gallardo IC, Soriano-Maldonado A, Estévez-López F, Delgado-Fernández M. Validation of the modified 2010 American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia in a Spanish population. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53:1803–1811. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Segura-Jimenez V, Aparicio VA, Alvarez-Gallardo IC, Carbonell-Baeza A, Tornero-Quinones I, Delgado-Fernandez M. Does body composition differ between fibromyalgia patients and controls? The al-Andalus project. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33(Suppl. 1):S25–S32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malavolti M, Mussi C, Poli M, Fantuzzi AL, Salvioli G, Battistini N. Cross-calibration of eight-polar bioelectrical impedance analysis versus dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry for the assessment of total and appendicular body composition in healthy subjects aged 21-82 years. Ann Hum Biol. 2003;30:380–391. doi: 10.1080/0301446031000095211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JW, Lee KE, Park DJ, Kim SH, Nah SS, Lee JH. Determinants of quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia: a structural equation modeling approach. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morimoto T, Oguma Y, Yamazaki S, Sokejima S, Nakayama T, Fukuhara S. Gender differences in effects of physical activity on quality of life and resource utilization. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:537–546. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-3033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown DW, Brown DR, Heath GW, Balluz L, Giles WH, Ford ES. Associations between physical activity dose and health-related quality of life. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2004;36:890–896. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000126778.77049.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Galloway DA, Laimins LA, Division B, Hutchinson F. How does physical activity modulate pain? Pain. 2016;158:87–92. [Google Scholar]

- 41.McAuley E, Doerksen SE, Morris KS, Motl RW, Hu L, Wojcicki TR. Pathways from physical activity to quality of life in older women. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36:13–20. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9036-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Motl RW, McAuley E, Snook EM, Gliottoni RC. Physical activity and quality of life in multiple sclerosis: intermediary roles of disability, fatigue, mood, pain, self-efficacy and social support. Psychol Health Med. 2009;14:111–124. doi: 10.1080/13548500802241902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elavsky S, McAuley E, Motl RW, Konopack JF, Marquez DX, Hu L. Physical activity enhances long-term quality of life in older adults: efficacy, esteem, and affective influences. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30:138–145. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3002_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kraut R, Patterson M, Lundmark V, Kiesler S, Mukopadhyay T, Scherlis W. Internet paradox—a social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? Am Psychol. 1998;53:1017–1031. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.9.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Segura-Jiménez V, Soriano-Maldonado A, Estévez-López F, Álvarez-Gallardo IC, Delgado-Fernández M, Ruiz JR. Independent and joint associations of physical activity and fitness with fibromyalgia symptoms and severity: the al-Ándalus project. J Sports Sci. 2017;35:1565–1574. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2016.1225971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Häuser W, Katz RL. 2016 revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46:319–329. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.