Abstract

This report, issued by the ACVIM Specialty of Cardiology consensus panel, revises guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD, also known as endocardiosis and degenerative or chronic valvular heart disease) in dogs, originally published in 2009. Updates were made to diagnostic, as well as medical, surgical, and dietary treatment recommendations. The strength of these recommendations was based on both the quantity and quality of available evidence supporting diagnostic and therapeutic decisions. Management of MMVD before the onset of clinical signs of heart failure has changed substantially compared with the 2009 guidelines, and new strategies to diagnose and treat advanced heart failure and pulmonary hypertension are reviewed.

Keywords: canine, congestive heart failure, evidence‐based treatment, mitral

Abbreviations

- ACEI

angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors

- Ao

aorta

- BW

body weight

- CHF

congestive heart failure

- CRI

constant rate infusion

- IM

intramuscularly

- LA

left atrium

- LOE

level of evidence

- LV

left ventricle

- LVIDD

left ventricular end diastolic diameter

- LVIDd

left ventricular end diastolic diameter in diastole

- LVIDdN

left ventricular end diastolic diameter normalized for body weight

- MMVD

myxomatous mitral valve disease

- MR

mitral regurgitation

- NT‐proBNP

N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide

- VHS

vertebral heart score

- VLAS

vertebral left atrial size

1. INTRODUCTION

The panel adopted the following scheme, adapted from the American Heart Association,1 to rate the strength of the recommendations in these guidelines. The recommendation class designation appears with each recommendation, along with a second term that independently rates the quality of the evidence upon which the recommendation was based.

2. CLASSIFICATION OF RECOMMENDATIONS

Class I recommendations are strong, reflecting the panel's conviction that the recommended action appears to have definite benefit for most patients, outweighing the risk to most patients.

Class I recommendations can be summarized as “benefit >>> risk”.

Class IIa recommendations are moderately strong, reflecting the panel's belief that the recommended action should benefit most patients, probably outweighing the risk to most patients.

Class IIa recommendations can be summarized as “benefit >> risk”.

Class IIb recommendations are weak, reflecting the belief that the recommended action possibly benefits some patients and may outweigh the risk of taking the proposed action in most patients.

Class IIb recommendations can be summarized as “benefit > risk”.

Class III is used to describe recommendations in which the panel believes that the potential risk and benefit of the proposed action are essentially equal, such that these actions should probably not be pursued under most circumstances.

Class III recommendations can be summarized as “benefit = risk”.

Class IV recommendations indicate the panel's belief that the proposed action is more likely to cause harm than benefit to most patients, such that Class IV designates actions that the panel believes are contraindicated under most circumstances.

Class IV recommendations can be summarized as “risk >> benefit”.

The recommendation classification and level of evidence (LOE) upon which that recommendation was based were independently determined by the panel (ie, any class of recommendation may be paired with any LOE).

The panel acknowledges that future evidence may change the strength of any of these recommendations, as well as the quality of the evidence on which they are based. Many important clinical questions addressed in the guidelines have not yet been adequately addressed by clinical trials. At times, the panel has made strong recommendations based on more than the available evidence—thus weak or even absent evidence does not necessarily accompany a weak recommendation. Although randomized clinical trial evidence may be unavailable, a clear clinical consensus that a particular test or treatment is useful may exist.

3. LEVELS OF EVIDENCE

The methods of assessing the quality of the scientific evidence that supports clinical decision making are evolving. The panel chose to use a hybrid of the American Heart Association and Veterinary Emergency Critical Care RECOVER evidence grading criteria, as outlined below.1, 2

3.1. Strong

High‐quality evidence is from ≥1 randomized controlled trial, or a moderate‐quality randomized controlled trial, corroborated by a high‐quality observational study or other moderate‐quality trials. These prospective clinical studies were performed in dogs and either randomly allocated subjects to an intervention or control group or used concurrent controls (ie, controls recruited at the same time as the experimental subjects) without randomization. Strong evidence also could have been obtained from prospectively enrolled, controlled, observational clinical studies in dogs with spontaneously occurring mitral valve disease. These studies asked clinically relevant questions, were considered to be adequately powered, and did not experience excessive loss of subjects to follow up in any group, generating a clear and statistically valid result.

3.2. Moderate

Moderate‐quality evidence is from ≥1 well‐designed, well‐executed nonrandomized studies, observational studies, or registry studies, or meta‐analyses of such studies. Evidence rated as “moderate” by the panel was generated from controlled, retrospective studies in dogs (ie, studies in which dogs with mitral valve disease [or appropriate controls] were selected from a previous period in time). Moderate evidence also could have been generated from blinded and controlled laboratory studies that were performed in experimental dogs.

3.3. Weak

Weak‐quality evidence is from randomized or nonrandomized observational or registry studies with limitations of design or execution, but performed in dogs with clinical myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD), or physiological, mechanistic, or experimental studies performed in research dogs. Evidence rated as “weak” by the panel was generated from uncontrolled clinical case reports or case series in dogs with mitral valve disease, as well as by experimental or clinical studies that were not performed in dogs with MMVD. These could include experimental models of mitral valve disease in other species, as well as high‐quality studies in humans (such as meta‐analyses, randomized controlled trials, and clinical studies with concurrent controls, including observational studies) with spontaneous mitral valve disease.

3.4. Expert opinion

Expert opinion based on clinical experience, common sense, or physiologic or mechanistic studies performed in species other than dogs is considered the weakest LOE.

4. INCIDENCE, PATHOLOGY, AND PATHOGENESIS OF MMVD

It is estimated that approximately 10% of dogs presented to primary care veterinary practices have heart disease, and MMVD is the most common heart disease of dogs in many parts of the world, accounting for approximately 75% of heart disease cases seen in dogs by veterinary practices in North America.

The pathology of MMVD has been relatively recently reviewed,3 and some progress in understanding the genetics and pathophysiology of the disease has been reported.4, 5 Myxomatous mitral valve disease most commonly affects the left atrioventricular or mitral valve, although in at least 30% of cases, the right atrioventricular (tricuspid) valve also is involved.6 The disease is approximately 1.5 times more common in males than in females. Prevalence is also higher in smaller (<20 kg) dogs, although large breeds sometimes are affected, and larger dogs also often experience faster disease progression with more apparent myocardial dysfunction, and have a more guarded prognosis.7 In small breed dogs, the disease generally is slowly but at times unpredictably progressive. Most dogs experience the onset of a recognizable murmur of mitral valve regurgitation years before the clinical onset of heart failure. Cavalier King Charles Spaniels notably are predisposed to developing MMVD at a relatively young age, although the time course of their disease progression to heart failure does not appear to be markedly different from that of other small breed dogs.8, 9

Although the cause of MMVD remains unknown, the disease has an inherited component in some breeds,5, 10 and the severity of the disease may have a genetic component in other breeds. The disease consistently is characterized by changes in the cellular constituents as well as the intercellular matrix of the valve apparatus (including the valve leaflets and chordae tendineae).11, 12 These changes involve both the collagen content and the alignment of collagen fibrils within the valve. Expansion of the spongiosa layer is characterized by changes in the proteoglycan content of this layer. Dysregulation of the extracellular matrix appears to be central to these changes. Valvular interstitial cells, possibly with post‐transcriptional regulation from microsatellite ribonucleic acids, acquire properties of activated myofibroblasts, and activated myofibroblasts increase proteolytic enzymes, including matrix metalloproteinases, which degrade collagen and elastin faster than they can be produced by unactivated valvular interstitial cells.13, 14, 15

Endothelial cell changes and subendothelial thickening also occur,16, 17, 18 but these changes do not appear to put dogs with MMVD at increased risk for either arterial thromboembolism or infective endocarditis. Mitral valve prolapse is a common finding in dogs with myxomatous valve degeneration and represents a prominent echocardiographic feature of MMVD in some breeds.10, 19, 20 Progressive deformation of the valve structure eventually prevents effective coaptation, allowing regurgitation (valve leakage). Progressive valvular regurgitation increases cardiac work, leading to ventricular remodeling (eccentric hypertrophy of both the atrium and ventricle, and intercellular matrix changes), and eventually to ventricular dysfunction.

It has been hypothesized that abnormal numbers or types of mitogen receptors (ie, any of the subtypes of serotonin, endothelin, or angiotensin receptors) on fibroblast cell membranes in the valves of affected dogs play a role in the pathophysiology of acquired valvular lesions.21, 22, 23 Systemic or local metabolic, neurohormonal, or inflammatory mediators (eg, endogenous catecholamines, inflammatory cytokines) also may influence progression of the valve lesion or the subsequent myocardial remodeling and ventricular dysfunction that accompany long‐standing, hemodynamically important valvular regurgitation. The interactions of these factors, as well as the impact of changes in mitral valve annular geometry and mechanical stress on the pathogenesis and progression of MMVD, are incompletely understood.11, 12, 13, 24

The prevalence of MMVD increases markedly with age in small breed dogs, with up to 85% showing evidence of the valve lesion by 13 years of age.25 The presence of the pathologic lesion of MMVD in an individual does not necessarily identify a dog that will develop clinically relevant valve regurgitation or signs of heart failure. Depending on the rate of progression of the individual's valvular disease relative to other common pathologic conditions that occur late in life and often prove fatal, the presence of MMVD in the absence of clinical signs may or may not influence the course of the affected dog's life.

It has become clear that age, progressive heart enlargement (of the left atrium [LA] and ventricle), increased transmitral E wave blood flow velocities, increased serum N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) concentrations, and increases in resting heart rate are at least moderately predictive of the rate of progression of MMVD and can help identify dogs at risk for impending heart failure.26, 27, 28, 29 The rate of change of echocardiographic and radiographic variables also may identify animals at increased risk of heart failure or death from cardiac cause.30, 31 Development of truly predictive (sensitive and specific) risk stratification schemes, however, awaits further refinement.

5. CLASSIFICATION OF HEART DISEASE AND HEART FAILURE

The term heart disease is used synonymously with cardiac pathology—in this case, myxomatous degenerative changes of the mitral valve. Heart disease, depending on its nature, rate of progression, and patient age and condition may or may not lead to heart failure. The term “heart failure” refers to clinical signs caused by heart dysfunction. Heart failure is caused by heart disease that affects heart function such that either venous pressures increase so severely that fluid accumulates in the lungs or a body cavity (congestive heart failure [CHF], sometimes called “backward heart failure because the heart fails to drain the veins adequately), or the heart's pumping ability is compromised such that it cannot meet the body's needs either during exercise or at rest, in the face of either normal or increased venous pressures (sometimes called “forward heart failure”).

In 2009, the consensus panel adapted a staging system for heart disease and heart failure, and sought to link the severity of morphologic changes and clinical signs to appropriate treatments at each stage.32 According to this approach, patients are expected to advance from 1 stage to the next stage, unless progression of the disease is altered by corrective treatment (such as surgery). This staging system, applied to dogs with MMVD, remains useful, although recent clinical trial results necessitate a more critical clinical evaluation of dogs in Stage B to facilitate sound therapeutic decision making.

This staging system for MMVD describes 4 basic stages of heart disease and heart failure:

Stage A identifies dogs at high risk for developing heart disease but that currently have no identifiable structural disorder of the heart (eg, every Cavalier King Charles Spaniel or other predisposed breed without a heart murmur).

- Stage B identifies dogs with structural heart disease (eg, the typical murmur of mitral valve regurgitation, accompanied by some typical valve pathology, is present), but that have never developed clinical signs caused by heart failure. In a change from the 2009 recommendations, strong evidence now supports initiating treatment to delay the onset of clinical signs of heart failure in a subset of stage B patients with more advanced cardiac morphologic changes (outlined below).

- Stage B1 describes asymptomatic dogs that have no radiographic or echocardiographic evidence of cardiac remodeling in response to their MMVD, as well as those in which remodeling changes are present, but not severe enough to meet current clinical trial criteria that have been used to determine that initiating treatment is warranted (see specific criteria below).

- Stage B2 refers to asymptomatic dogs that have more advanced mitral valve regurgitation that is hemodynamically severe and long‐standing enough to have caused radiographic and echocardiographic findings of left atrial and ventricular enlargement that meet clinical trial criteria used to identify dogs that clearly should benefit from initiating pharmacologic treatment to delay the onset of heart failure (specific criteria detailed below).

Stage C denotes dogs with either current or past clinical signs of heart failure caused by MMVD. Because of important treatment differences between dogs with acute heart failure requiring hospital care and those in which heart failure can be treated on an outpatient basis, these issues have been addressed separately by the panel. It is important to note that some dogs presented with heart failure for the first time may have severe clinical signs requiring aggressive treatment (eg, with additional afterload reducers or temporary ventilatory assistance) that more typically would be reserved for those patients refractory to standard treatment (see Stage D below).

Stage D refers to dogs with end‐stage MMVD, in which clinical signs of heart failure are refractory to standard treatment (defined later in this consensus statement). Such patients require advanced or specialized treatment strategies to remain clinically comfortable with their disease, and at some point, treatment efforts become futile without surgical repair of the valve. As with Stage C, the panel has distinguished between dogs in Stage D that require acute, hospital‐based treatment and those that can be managed as outpatients.

This staging system emphasizes that there are known risk factors and structural prerequisites for the development of heart failure caused by MMVD. Accordingly, the classification system is designed to aid in:

developing screening programs for the presence of MMVD in dogs known to be at risk;

implementing interventions that may (now and in the future) decrease the risk of disease development or progression;

identifying asymptomatic dogs with MMVD early in the course of their disease, comparable to in situ cancer, so they can be more effectively managed medically as chronic disease patients, or possibly be treated surgically;

identifying symptomatic dogs with MMVD so that these patients can be managed medically as chronic disease patients or possibly treated surgically; and

identifying symptomatic dogs with advanced heart failure caused by MMVD refractory to conventional medical treatment. These patients require aggressive or new treatment strategies, possibly including surgery, or potentially palliative or hospice‐type end‐of‐life care.

6. GUIDELINES FOR DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF MMVD

6.1. Stage A

Dogs at higher than average risk for developing heart failure but without any apparent structural abnormality (ie, no audible heart murmur) at the time of examination.

6.1.1. Recommendations for diagnosis of Stage A (unchanged from 2009)

Small breed dogs, including breeds with known predisposition to develop MMVD (eg, Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, Dachshunds, Miniature, and Toy Poodles) should undergo regular evaluations (yearly auscultation by the family veterinarian) as part of routine health care. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

Owners of breeding dogs or those at especially high risk, such as Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, may choose to participate in yearly screening events at dog shows or other events sponsored by their breed association or kennel club and conducted by board‐certified cardiologists participating in an ACVIM‐approved disease registry. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

6.1.2. Recommendations for treatment of Stage A (unchanged from 2009)

No drug treatment recommended for any patient. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

No dietary treatment recommended for any patient. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

Potential breeding animals should no longer be bred if a murmur or echocardiographic evidence of mitral regurgitation (MR) is identified early, during the normal breeding age range (<6‐8 years of age). (Class I, LOE: moderate)33, 34

6.2. Stage B

Dogs in Stage B have a structural abnormality (eg, the presence of MMVD) but have never had clinical signs of heart failure associated with their disease.

6.2.1. Recommendations for diagnosis and further categorization of Stage B

Myxomatous mitral valve disease typically is recognized during a screening or routine health examination by auscultation of a heart murmur typical of mitral valve regurgitation.

Thoracic radiography is recommended in all patients to assess the hemodynamic relevance of the valve disease and to obtain baseline thoracic radiographs at a time when the patient is asymptomatic for MMVD. Patients with MMVD frequently have concurrent tracheal or bronchial diseases and having baseline radiographs at a time when the dog is asymptomatic can enhance the ability to radiographically differentiate cardiac from noncardiac causes of cough in the face of future clinical signs. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion).

Blood pressure measurement is recommended for all patients to identify or rule out concurrent systemic hypertension and to establish baseline blood pressure. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

Echocardiography, performed by an experienced operator, is recommended to definitively identify the cause of the murmur, answer specific questions regarding the severity of cardiac chamber enlargement, and identify comorbidities. A specialist's examination might identify hemodynamic abnormalities including pulmonary hypertension or increased left atrial pressure. Echocardiographic identification of mild left atrial or ventricular enlargement can be challenging, and comparisons to breed‐specific normal values may be required (Class I, LOE: Moderate).35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41 In addition to short axis basilar views, recently described 2‐dimensional, long‐axis echocardiographic ratios (left ventricle (LV)/aorta (Ao), LA/Ao, and LA/LV) have proven to be effective for identifying left atrial and ventricular enlargement in dogs with MMVD.42 (Class I, LOE: strong)

The panel recognizes that it is sometimes necessary to use thoracic radiography in the absence of echocardiography to further refine Stage B. Under these circumstances, the clinician must be cautious because of marked variation in thoracic conformation and breed differences in normal vertebral heart scales; the use of the vertebral left atrial size (VLAS) (details below) may be beneficial. (Class I, LOE: moderate)

6.3. Stage B1: Asymptomatic dogs with mitral valve regurgitation caused by MMVD that is not severe enough to meet criteria used to trigger the use of medical treatment to delay the onset of heart failure.

Stage B1 dogs are characterized by a spectrum of imaging findings ranging from those with radiographically and echocardiographically normal left atrial [LA] and ventricular [LV] dimensions with normal LV systolic function and normal radiographic vertebral heart or VLAS to those with echocardiographic or radiographic evidence of left atrial and ventricular enlargement that does not meet specific criteria outlined below.

6.3.1. Recommendations for treatment and monitoring of Stage B1 (both pharmacologic and dietary, small and large breed dogs) remain unchanged from the 2009 recommendations

Treatment is not recommended in these dogs because at this early stage of disease, progression to heart failure is uncertain, unlikely to occur within the recommended evaluation interval, and there is no evidence that medication is effective at this stage. To summarize,

No drug or dietary treatment is recommended (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

Reevaluation by echocardiography is suggested (or radiography if echocardiography is unavailable) in 6‐12 months, depending on the imaging results (some panelists recommend more frequent follow‐up in large dogs). (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

6.4. Stage B2: Asymptomatic MMVD causing MR severe enough to result in cardiac remodeling (LA and LV enlargement) sufficient to recommend treatment before the onset of clinical signs based on the results of a clinical trial.43, 44 Dogs in this category should meet the current criteria outlined below.

- Stage B2 criteria for heart enlargement identify dogs that are likely to benefit substantially from treatment before the onset of clinical signs of heart failure. (Class I, LOE: Strong):

- murmur intensity ≥3/6;

Ideally, all these criteria should be met before initiating treatment, because treatment represents a lifelong commitment. Of these criteria, echocardiographic evidence of left atrial and ventricular enlargement meeting or exceeding these criteria is considered to be the most reliable way to identify dogs expected to benefit from treatment.

Although studies to identify reliable radiographic markers of Stage B2 cardiac remodeling and enlargement in MMVD are underway, definitive criteria for the radiographic identification of this stage are currently not available. In the absence of echocardiographic measurements, clear radiographic evidence of cardiomegaly (eg, a “general breed” VHS ≥11.5, or a comparable “breed‐adjusted” VHS in cases where breed‐specific VHS normal values are available) or evidence of accelerating (increasing) interval change in radiographic or echocardiographic cardiac enlargement patterns42 can substitute for quantitative echocardiography to identify Stage B2. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

A newer index of radiographic left atrial enlargement, the VLAS, provides a quantitative method of estimating left atrial size. Measured on either the right or left lateral radiograph by drawing a line from the center of the most ventral aspect of the carina to the most caudal aspect of the LA where it intersects with the dorsal border of the caudal vena cava, that line then is transposed to the cranial edge of the 4th thoracic vertebral body.54 Studies are ongoing to determine a VLAS value that accurately predicts B2 remodeling, but in the absence of echocardiography, VLAS values of ≥3 likely identify Stage B2 MMVD. (Class 1, LOE: moderate)

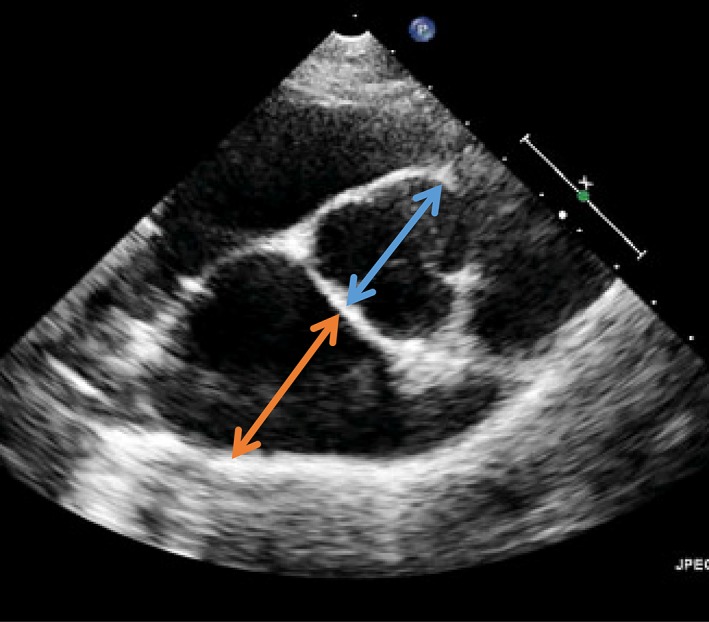

Figure 1.

One of the 4 criteria that identify advanced Stage B2 in dogs is that the echocardiographic LA : Ao ratio as measured in the right‐sided short‐axis view in early diastole is ≥1.6. The measurement is illustrated. The blue arrow illustrates the measurement of the aortic dimension at the level of the aortic valve, and the orange arrow illustrates measurement of the left atrial dimension

Table 1.

One of the 4 criteria that identify advanced Stage B2 in dogs is an increase in their left ventricular chamber size, such that normalized to their body weight (BW), it is ≥1.7

| BW (kg) | LVIDD (cm) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1.7 |

| 2 | 2.1 |

| 3 | 2.4 |

| 4 | 2.6 |

| 5 | 2.7 |

| 6 | 2.9 |

| 7 | 3.0 |

| 8 | 3.1 |

| 9 | 3.2 |

| 10 | 3.3 |

| 11 | 3.4 |

| 12 | 3.5 |

| 13 | 3.6 |

| 14 | 3.7 |

| 15 | 3.8 |

| 16 | 3.8 |

| 17 | 3.9 |

| 18 | 4.0 |

| 19 | 4.0 |

| 20 | 4.1 |

For dogs weighing between 1 and 20 kg (BW, left hand column), the left ventricular end diastolic diameter (LVIDD) meeting this criterion must be more than or equal to the dimension (in cm) in the right hand column. In the referenced clinical trial, the end‐diastolic LV dimension was obtained from a 2D short‐axis‐guided M‐mode echocardiogram of the chamber.55 The formula for normalizing LVIDD to BW is LVIDdN = LVIDd (cm)/weight (kg)0.294. [Correction added on 24‐April‐2019, after first online publication: in the legend for Table 1, (cm)/weight (kg)0294 was corrected to (cm)/weight (kg)0.294]

6.4.1. Recommendations for treatment of Stage B2

Pimobendan is recommended at a dosage of 0.25‐0.3 mg/kg PO q12h.44, 55 (Class I, LOE: strong)

Dietary treatment is recommended. Principles guiding dietary treatment at this stage include mild dietary sodium restriction and provision of a highly palatable diet with adequate protein and calories for maintaining optimal body condition.56 (Class IIa, LOE: weak)

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI): For patients in Stage B2 on either initial examination, or in which the LA has increased markedly in size on successive monitoring examinations, 5 (of 10) panelists recommend treatment with ACEI.57, 58, 59 (Class IIa in geographic regions where ACEI are low cost, LOE: weak)

Clinical trials addressing the efficacy of ACEI for treatment of dogs in Stage B have shown mixed results.

Beta blockade is not recommended routinely to delay the onset of heart failure in dogs in Stage B2, regardless of heart enlargement. Clinical trials addressing the efficacy of beta blockers for the treatment of dogs in Stage B2 have shown no benefit to date. (Class III, LOE: weak)

Spironolactone also is not recommended for routine use to delay the onset of heart failure in dogs. Clinical trials addressing the efficacy of spironolactone for the treatment of dogs in Stage B2 have not been published as of this writing (2019), although a pilot study suggests this approach should be used60 (Class IIb, LOE: expert opinion).

No other pharmacologic treatments for Stage B were recommended by a majority of panelists. A few panelists considered the use of the following medications for patients in advanced Stage B2 under specific circumstances: beta blockers, amlodipine. These treatment strategies require further investigation to assess their efficacy and safety in this patient population before definitive recommendations can be made. (Class III, LOE: expert opinion)

Some panelists find the use of cough suppressants useful in occasional patients in advanced Stage B2 when their cough is thought to be the result of pressure from cardiac enlargement (without pulmonary edema) on adjacent bronchi. (Class IIa, LOE: expert opinion)

Surgical intervention in advanced Stage B2 is possible and recommended by some panelists for clients who can afford and access mitral valve repair at the few centers demonstrating evidence of acceptably low complication rates and effective, durable results.61, 62, 63 (Class IIa, LOE: moderate)

6.5. Stage C

Stage C dogs have MMVD severe enough to cause current or past clinical signs of heart failure. Stage C includes all dogs with MMVD that have experienced an episode of clinical heart failure and that are not refractory to standard heart failure treatment (standard treatment is defined below). These patients continue to be categorized as Stage C even after improvement or complete resolution of their clinical signs with standard treatment. In exceptional cases that undergo successful surgical mitral valve repair, reclassification to Stage B is warranted.

Guidelines for standard pharmacologic treatment are provided for both in‐hospital (acute) management of heart failure and for home care (chronic) management of heart failure, as well as recommendations for chronic dietary management. Some patients in Stage C may have life‐threatening clinical signs and require more extensive acute treatment than is considered standard. These acute care patients temporarily may share medical management strategies with dogs that have progressed to Stage D (refractory heart failure, see below).

For both Stages C and D (MMVD patients with symptomatic heart failure), the acute care of heart failure is focused on regulating the patient's hemodynamic status and tissue oxygen delivery. This is accomplished by monitoring (as much as possible, under existing clinical circumstances) and optimizing the patient's preload, afterload, heart rate, contractility, and oxygenation, while decreasing oxygen demand. The ultimate goals include improving cardiac output, decreasing mitral valve regurgitation, and relieving clinical signs associated with either low cardiac output or excessively increased venous pressures (congestion), especially pulmonary dysfunction.

The broad goals of chronic management (in clinical settings where surgery to effectively repair the mitral valve is not possible) are focused on maintaining hemodynamic improvements while providing additional treatments aimed at slowing the progression of disease, prolonging survival, decreasing the clinical signs of CHF, enhancing exercise capacity, maintaining body weight (BW), and improving quality of life.

6.5.1. Recommendations for diagnosis of Stage C

The signalment, history, and physical examination can be helpful in determining the pretest probability of heart failure as a cause of clinical signs in patients with MMVD. For example, obese dogs with no history of weight loss are less likely to be in heart failure secondary to MMVD; dogs with marked sinus arrhythmia and relatively slow heart rates also are less likely to have clinical signs attributable to MMVD than are those with similar clinical signs (eg, cough, dyspnea) with sinus rhythm or sinus tachycardia. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

The typical dog in Stage C from MMVD presents with clinical signs of left‐sided CHF and a history that can include tachypnea, restlessness, respiratory distress, or cough. Because of the relatively high prevalence of chronic tracheobronchial disease in the population most at risk for MMVD, the presence of a typical left apical regurgitant quality murmur in a coughing dog does not necessarily mean that clinical signs are the result of CHF. A clinical database (including thoracic radiographs and ideally an echocardiogram) should be obtained. Additionally, basic laboratory tests, including at a minimum PCV as well as serum total protein, creatinine, urea nitrogen and electrolyte concentrations, and urine specific gravity) should be obtained as soon as practical in dogs with heart failure. Impaired renal function in particular represents an important comorbidity in dogs with heart failure. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

Echocardiography with Doppler studies also is useful in the diagnosis of dogs with MMVD that have advanced to Stages C and D. Cardiac ultrasound examination can confirm the presence of MMVD, quantify chamber enlargements and cardiac function, provide general estimates of LV filling pressures, and identify comorbidities and complications of chronic MR. These might include pulmonary hypertension, acquired atrial septal defect, and pericardial effusion from an atrial tear or unrelated cardiac tumor. As an example, a pretreatment finding of a low‐velocity E‐wave on pulsed‐wave Doppler strongly argues against a diagnosis of left‐sided heart failure. Conversely, most dogs in Stages C and D have high‐velocity early filling waves. In dogs with evidence of symptomatic pulmonary hypertension (eg, exertional fatigue, collapse or syncope, ascites from right‐sided CHF), spectral Doppler findings can substantiate the diagnosis and help guide therapeutic decision‐making.

Serum NT‐proBNP concentrations (obtained using a commercially available test) can add useful adjunct evidence when determining the cause of clinical signs in dogs with MMVD, especially when the NT‐proBNP concentration is normal or nearly normal in a symptomatic animal. As a group, dogs with clinical signs caused by heart failure have higher serum NT‐proBNP concentrations than do dogs in which clinical signs are caused by primary pulmonary disease, although the positive predictive value of any single specific NT‐proBNP concentration has not been adequately characterized. A normal or near normal NT‐proBNP concentration in a dog with clinical signs of cough, dyspnea, or exercise intolerance strongly suggests that heart failure is not the cause of the clinical signs.64, 65 (Class I, LOE: moderate)

Most symptomatic dogs with MMVD are middle‐aged or older, and it is prudent to complete the clinical database with a blood pressure assessment, CBC, serum biochemical profile, and urinalysis, especially if treatment for CHF is anticipated. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

6.5.2. Recommendations for acute (hospital‐based) treatment of Stage C

Furosemide 2 mg/kg administered IV (or intramuscularly [IM]), followed by 2 mg/kg IV or IM hourly until the patient's respiratory signs are substantially improved (ie, respiratory rate and effort are decreased) or a total dosage of 8 mg/kg has been reached over 4 hours. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

For life‐threatening pulmonary edema (ie, expectoration of froth associated with severe dyspnea, radiographic white‐out lung, poor initial response to furosemide bolus with failure of respiratory effort and rate to improve over 2 hours), furosemide also may be administered as a constant rate infusion (CRI) at a dosage of 0.66‐1 mg/kg/hour after the initial bolus.66, 67 (Class IIa, LOE: weak)

Allow the patient free access to water once diuresis has begun. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion; humane considerations apply)

Pimobendan, 0.25‐0.3 mg/kg administered PO q12h. Although the clinical trial evidence supporting the chronic use of pimobendan in the management of Stage C heart failure from MMVD is stronger than for the acute presentation, the recommendation to use pimobendan in acute heart failure treatment is strongly supported by hemodynamic and experimental evidence68 as well as the anecdotal experience of the panelists. In many countries outside of the United States, pimobendan for IV administration is available. (Class I, LOE: weak)

Oxygen supplementation, if needed, can be administered via a humidity and temperature‐controlled oxygen cage or incubator or via a nasal oxygen cannula. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

Mechanical treatments (eg, abdominal paracentesis, thoracentesis) are recommended to relieve effusions judged sufficient to impair ventilation or cause respiratory distress. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

Sedation‐anxiety associated with dyspnea should be treated. Narcotics, or a narcotic combined with an anxiolytic agent, most often are used by panelists. Care must be taken to monitor the blood pressure and respiratory response to narcotics and tranquilizers in the setting of acute heart failure. No specific treatment or dosage regimen was used by all panelists. Butorphanol 0.2 to 0.25 mg/kg administered IM or IV was the narcotic most often utilized for this purpose; combinations of buprenorphine (0.0075‐0.01 mg/kg) and acepromazine (0.01‐0.03 mg/kg IV, IM, or SC) as well as other narcotics, including morphine and hydrocodone, also were suggested. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

Provide optimal nursing care, including maintenance of appropriate environmental temperature and humidity, increase of the head on pillows, and placement of sedated patients in sternal posture. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

Dobutamine (2.5‐10 μg/kg/min as a CRI, starting at 2.5 μg/kg/min and increasing the dosage incrementally) may be used in addition to the above treatments to improve the left ventricular function in patients that fail to respond adequately to diuretics, pimobendan, sedation, oxygen, and comfort care measures. Continuous ECG monitoring is recommended where available during dobutamine infusion, with dosage reduction indicated if tachycardia or ectopic beats occur. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

Constant IV infusion of sodium nitroprusside at dosages ranging from 1 to 15 μg/kg/min) for up to 48 hours often is useful for life‐threatening, poorly responsive pulmonary edema69; this medication is currently (2018) expensive in the United States. The use and PO titration of additional arterial dilators (eg, hydralazine or amlodipine, specific dosing recommendations also in Class D below) also may be useful in patients when administration of nitroprusside is not feasible. (Class I, LOE: weak)

ACEI, for example, enalapril or benazepril, 0.5 mg/kg PO q12h. Although treatment with an ACEI is a Class I recommendation for chronic Stage C heart failure (see below) and some panelists also treat acute heart failure with ACEI, the evidence supporting ACEI efficacy and safety in acute treatment, when combined with furosemide and pimobendan, is less clear. There is, however, clear evidence that the acute administration of enalapril plus furosemide in acute heart failure results in significant improvement in pulmonary capillary wedge pressure when compared with the administration of furosemide alone.70 (Class IIb, LOE: weak)

Nitroglycerin ointment, approximately half an inch paste/10 kg BW, applied to an unhaired or shaved area of skin, can be used for the first 24 to 36 hours of hospitalization.71, 72 Some panelists recommend administering the ointment at intervals (12 hours on, 12 hours off). Other panelists do not use nitroglycerin in this setting. (Class IIb, LOE: weak)

6.5.3. Recommendations for chronic (home‐based) treatment of Stage C

Continue PO furosemide administration to effect, commonly at a dosage of 2 mg/kg administered q12h, or as needed to maintain patient comfort. Some panelists now choose to substitute torsemide for furosemide at 1/10‐1/20 or approximately 5% to 10% of the furosemide dosage, or approximately 0.1‐0.3 mg/kg q24h73 for home care in animals in which hospitalized CHF management using furosemide was difficult or met with limited success. (Class I, LOE: moderate)

Chronic PO furosemide dosages ≥8 mg/kg q24h in any dosing regimen (or the equipotent torsemide dosage) needed to maintain patient comfort in the face of appropriate dosages of pimobendan, an ACEI, and spironolactone indicate disease progression to Stage D. Consideration of known causes of diuretic resistance, including noncompliance (ie, not receiving the drug), high sodium intake, slow absorption (eg, gut edema), impaired secretion into the renal tubular lumen (eg, chronic kidney disease, advanced age, concurrent nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug use), hypoproteinemia, hypotension, nephron remodeling, and neurohormonal activation is warranted. (Class I, LOE: weak)

Measurement of serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, and electrolyte concentrations 3‐14 days after initiating furosemide treatment is recommended for animals with Stage C heart failure. (Class I, LOE: weak)

Continue or start ACEI (eg, enalapril or benazepril, 0.5 mg/kg PO q12h) or an equivalent dosage of another ACEI, if approved for this use. Measurement of serum creatinine and electrolyte concentrations 3‐14 days after beginning an ACEI is recommended for animals with Stage C heart failure. Concern for development of acute kidney injury is warranted should serum creatinine concentrations increase by ≥30% of the baseline concentration. (Class I, LOE: weak)

Spironolactone (2.0 mg/kg PO q12 ‐ 24 h) is recommended as an adjunct for chronic treatment of dogs in Stage C heart failure. The primary benefit of spironolactone in this situation is thought to be aldosterone antagonism.74, 75 (Class I, LOE: moderate)

Continue pimobendan, 0.25‐0.3 mg/kg PO q12h.76, 77 (Class I, LOE: strong)

Panelists recommend against starting a beta blocker in the face of active clinical signs of CHF (eg, cardiogenic pulmonary edema) caused by MMVD. (Class IV, LOE: weak)

None of the panelists routinely use nitroglycerin in the chronic treatment of Stage C heart failure. (Class III, LOE: expert opinion)

Participation in a structured, home‐based extended care program to promote ideal BW, appetite, respiratory and heart rate monitoring while providing client support to enhance medication regimen adherence and dosage adjustments in patients with heart failure is encouraged. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

Of these variables, identification of increases in resting respiratory rate above normal baseline has the best predictive value for impending clinical decompensation.78, 79 (Class I, LOE: moderate).

In centers with low complication rates, Stage C patients benefit from surgical intervention to repair their mitral valve apparatus.61, 63 (Class I, LOE: moderate)

In cases complicated by atrial fibrillation, diltiazem, often in combination with digoxin (see below), is recommended to control ventricular rate. Multiple preparations of diltiazem are available; treatment should be started at a modest dosage for the preparation chosen and titrated to achieve heart rate control. Ideally, mean heart rate as measured by Holter monitoring in dogs with well‐controlled signs of CHF receiving stable drug dosage regimens should be close to normal or at least <125 beats per minute.80, 81 (Class I, LOE: moderate)

Digoxin 0.0025‐0.005 mg/kg, administered PO q12h to achieve a target steady‐state plasma concentration (approximately 8 hours post‐pill) of 0.8‐1.5 ng/mL. For the chronic management of Stage C heart failure, panelists recommended the addition of digoxin only in cases complicated by persistent atrial fibrillation to slow the ventricular response rate. In these cases, digoxin generally is used in combination with diltiazem. Digoxin may not be tolerated in patients with factors known to put animals at risk for adverse effects or toxicity (eg, increases of serum creatinine concentration above normal, ventricular ectopy, concerns over owner adherence, or chronic gastrointestinal disease resulting in frequent or unpredictable bouts of vomiting or diarrhea).82 (Class IIb, LOE: moderate)

In patients receiving a beta blocker before the onset of Stage C heart failure, the majority of panelists continue beta blockade; some panelists consider dosage reduction if needed clinically because of clinical signs of low cardiac output, hypothermia, or bradycardia. (Class IIB, LOE: expert opinion)

Some panelists find the use of cough suppressants useful in occasional patients in Stage C heart failure from MMVD. (Class IIa, LOE: expert opinion)

Some panelists find the use of bronchodilators useful in occasional patients in Stage C MMVD patients. (Class IIb, LOE: expert opinion)

6.5.4. Recommendations for dietary treatment for Stage C

Cardiac cachexia is defined as a loss of muscle or lean body mass associated with heart failure, with or without clinically relevant accompanying weight loss. Cachexia has substantial negative prognostic implications and is much easier to prevent than to treat.83, 84 (Class I, LOE: moderate)

Maintain adequate calorie intake (maintenance calorie intake in Stage C should be approximately 60 kcal/kg BW) to minimize weight loss that often occurs in CHF.85, 86 Simple culinary strategies to improve appetite may be beneficial in accomplishing this goal (eg, warming food, mixing wet food with dry food, offering a variety of foods). (Class I, LOE: moderate)

Specifically address and inquire about the occurrence of anorexia and make efforts to treat any drug‐induced or other identifiable causes of anorexia that occur. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

Record body condition score and accurate weight of the patient at every clinic visit and investigate the cause of clinically relevant changes in body condition, weight gain or loss. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

Ensure adequate protein intake and avoid low‐protein diets designed to treat chronic kidney disease, unless severe concurrent renal failure is present.83 (Class I, LOE: moderate)

Modestly restrict sodium intake, taking into consideration sodium from all dietary sources (including dog food, treats, table food, and foods used to administer medications) and avoid any processed or other salted foods.87, 88 (Class I, LOE: moderate)

Monitor serum electrolyte concentrations and supplement the diet with potassium from either natural or commercial sources only if hypokalemia is identified. The panel's anecdotal experience is that hypokalemia is much more common in animals receiving torsemide. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

Hyperkalemia is relatively rare in patients treated for CHF with diuretics, even in those concurrently receiving ACEI in combination with spironolactone. Diets and foods with high potassium content should be avoided when hyperkalemia is present. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

Consider monitoring serum magnesium concentrations, especially as heart failure progresses and in dogs with arrhythmias. Supplement with magnesium in cases in which hypomagnesemia is identified. (Class IIa, LOE: expert opinion)

Consider supplementing with omega‐3 fatty acids, especially in dogs with decreased appetite, muscle loss, or arrhythmia.86 (Class IIa, LOE: moderate)

6.6. Stage D

Patients have clinical signs of failure refractory to standard treatment for Stage C heart failure from MMVD. Stage D dogs thus require more than a total daily dosage of 8 mg/kg of furosemide or the equivalent dosage of torsemide, administered concurrently with standard doses of the other medications thought to control the clinical signs of heart failure (eg, pimobendan, 0.25‐0.3 mg/kg PO q12h, a standard dosage of approved ACEI, and 2.0 mg/kg of spironolactone daily). When needed, antiarrhythmic medication to maintain sinus rhythm or regulate the ventricular response to atrial fibrillation (mean daily heart rate <125/minute)81 should be in use before a patient is considered to be refractory to standard treatment.

Few clinical trials have addressed drug efficacy and safety in this patient population. This deficiency leaves cardiologists treating heart failure refractory to conventional medical treatment with a perplexing variety of treatment options. Because of the relative lack of clinical trial evidence and the diverse clinical presentations of patients with end‐stage heart failure, development of meaningful consensus guidelines regarding the timing and implementation of individual pharmacologic and dietary treatment strategies for Stage D patients proved difficult.

Surgical intervention to repair the mitral valve at Stage D is possible and indicated where feasible, although it is associated with higher perioperative mortality and decreased overall survival in studies reported to date.61

As with Stage C, guidelines for pharmacologic treatment are provided for both in‐hospital (acute) and at‐home care (chronic) management of heart failure, as well as recommendations for chronic dietary management.

6.6.1. Recommendations for the diagnosis of Stage D (refractory heart failure)

Because Stage D heart failure patients are, by definition, refractory to the standard treatments for Stage C patients, defining refractory CHF involves the same diagnostic steps outlined for Stage C plus the finding of failure to respond to treatments outlined in the Stage C guidelines.

6.6.2. Recommendations for acute (hospital‐based) treatment of Stage D

In the absence of severe renal insufficiency (eg, serum creatinine concentration >3 mg/dL), additional furosemide can be administered to dyspneic patients diagnosed with refractory heart failure as an initial 2 mg/kg IV bolus followed by either additional bolus doses or a furosemide CRI at a dosage of 0.66‐1 mg/kg/h, until respiratory distress (rate and effort) has decreased, or for a maximum of 4 hours. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

Torsemide, a potent long‐acting loop diuretic may be used to treat dogs no longer adequately responsive to furosemide (0.1‐0.2 mg/kg q12h‐q24h or approximately 5%‐10% of the current furosemide dosage to deliver a furosemide‐equivalent dose).28 It appears that the diuresis induced by torsemide produces less renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system activation than more frequent doses of furosemide, similar to what has been shown in dogs and horses with the diuresis induced by furosemide CRI.89, 90 Clinicians should continue to allow patients free access to water, once diuresis has begun. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

- Cavitary centesis (abdominal paracentesis, thoracentesis), as needed to relieve respiratory distress or discomfort. (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

- In addition to oxygen supplementation as in Stage C (above), mechanical ventilatory assistance may be useful in making the patient comfortable, in allowing time for medications to have an effect, and in providing time for left atrial dilatation to accommodate sudden increases in mitral valve regurgitant volume in patients with acute exacerbation of MMVD (eg, chordae tendineae rupture with severe cardiogenic pulmonary edema) and impending respiratory failure.91 (Class I, LOE: weak)

In patients that can tolerate it, more vigorous afterload reduction (arterial vasodilation) is recommended, with close monitoring of arterial blood pressure. In cases in which mechanical ventilation and IV vasodilator or inotropic support is needed, arterial pressure monitoring via peripheral arterial catheterization is preferred over noninvasive blood pressure monitoring when possible. In dogs judged to be too sick to wait for the effects of PO afterload reduction or inotropic support (eg, pimobendan with or without hydralazine or amlodipine), the administration of a CRI IV of sodium nitroprusside (for afterload reduction) or dobutamine (for inotropic support, especially in hypotensive patients) or both is recommended by a majority of panelists.69 Both are started at dosages of 1.0 μg/kg/min and up‐titrated every 15‐30 minutes to a maximum of approximately 10‐15 μg/kg/min. These rates may be used for 12‐48 hours to improve hemodynamic status and control refractory cardiogenic pulmonary edema. Continuous ECG and blood pressure monitoring are recommended to minimize the potential risks of this treatment. (Class IIa, LOE: weak)

Potentially beneficial PO drugs that decrease afterload in this situation include hydralazine (0.5‐2.0 mg/kg PO, starting at a low dosage and titrating to effect as described above with nitroprusside, but with hourly dosage increases or amlodipine (approximately 0.05‐0.1 mg/kg PO, also to effect, although maximal drug effect does not occur for approximately 3 hours, mandating a slower titration). (Class I, LOE: expert opinion)

These drugs are recommended in addition to an ACEI and pimobendan. Vigilance is needed to avoid serious, prolonged hypotension (monitor blood pressure closely, maintaining arterial systolic blood pressure >85 mm Hg, or mean arterial blood pressure >60 mm Hg). Serum creatinine concentration should be reevaluated no more than 24 to 72 hours after initiating these drugs.

The panel emphasized that because afterload reduction may increase cardiac output substantially in the setting of severe MR and heart failure, administration of an effective arterial dilator drug in this setting does not necessarily compromise blood pressure. (Class IIa, LOE: expert opinion).

Sildenafil, (starting at 1‐2 mg/kg PO q8h, and titrating if needed) is used by panelists to treat Stage D heart failure from MMVD that is complicated by clinically relevant estimated pulmonary hypertension. Pulmonary hypertension is recognized as an increasingly frequent complication of MMVD, either as a direct consequence of severe mitral valve regurgitation or as an independent comorbidity that can be responsible for clinical signs including syncope, cough, and shortness of breath (dyspnea), and sometimes radiographically evident pulmonary infiltrates.92, 93 (Class I, LOE: moderate) The occurrence of ascites or jugular distension in patients with primarily left‐sided heart disease is suggestive of pulmonary hypertension and should prompt an attempt to conclusively diagnose and identify patients that may benefit from sildenafil. (Class IIa, LOE: weak)

Pimobendan dosage may be increased (off‐label use) to include a third 0.3 mg/kg daily PO dose (ie, 0.3 mg/kg PO q8h); some panelists administer an additional dose of pimobendan on admission to Stage D patients with acute pulmonary edema regardless of the timing of the last dose given at home. This dosage recommendation is outside the US Food and Drug Administration–approved labeling for pimobendan (off‐label use), and this use of the drug should be explained to and approved by the client. (Class IIa, LOE: expert opinion)

Some panelists recommend adjunctive treatment with bronchodilators in treating cardiogenic pulmonary edema in hospitalized patients. (Class IIb, LOE: expert opinion)

6.6.3. Recommendations for chronic (home‐based) Stage D treatment

Furosemide (or torsemide) dosage should be increased as needed to decrease the accumulation of pulmonary edema or body cavity effusions, if not limited by renal dysfunction (indicators of which generally should be monitored 12‐48 hours after dosage increases). Inappetence may increase the risk of development of azotemia associated with medications for heart failure. The specific strategy and magnitude of dosage increase (eg, same dosage divided q8h instead of 2 higher doses, substituting 1 SC dose for a PO dose q4h, or flexible SC dose supplementation, based on BW or girth measurements) varied widely among the panelists. See Stage C recommendations (above) for a brief discussion of diuretic resistance. (Class IIa, LOE: expert opinion)

Torsemide, a potent and longer‐acting loop diuretic, may be used to treat dogs no longer adequately responsive to furosemide (torsemide beginning dosage of 0.1‐0.2 mg/kg PO, or approximately 5%‐10% of the current furosemide dosage, up to approximately 0.6 mg/kg, divided q12h if necessary).94 (Class I, LOE: moderate)

Spironolactone, if not already started as recommended in Stage C, is indicated for chronic treatment of Stage D patients.74 (Class I, LOE: moderate)

Beta blockers generally should not be initiated at this stage, unless they are being used as an adjunct to control heart rate in atrial fibrillation. (Class IV, LOE: expert opinion)

Hydrochlorothiazide was recommended by several panelists as adjunctive treatment to furosemide or torsemide, utilizing various dosing schedules (including intermittent use every 2nd‐4th day). Some panelists warned of the risk of acute kidney insufficiency and marked electrolyte disturbances, based on personal experience. (Class IIb, LOE: expert opinion)

Pimobendan dosage is increased by some panelists to include a third 0.3 mg/kg daily dose (off‐label use; routine explanations and cautions to the owner apply as in hospital care described above) or an even higher dosage when repeated rescue is necessary. (Class IIa, LOE: expert opinion)

Additional afterload reduction, using either amlodipine or hydralazine (see dosages and cautions above), may provide additional hemodynamic benefit and decrease cough frequency.

Digoxin, at the same (relatively low) dosages recommended by some panelists for Stage C heart failure with atrial fibrillation, is recommended for the treatment of atrial fibrillation in Stage D patients lacking a concrete contraindication.82 (Class IIb, LOE: moderate)

Digoxin, at the same (relatively low) dosages recommended by some panelists for Stage C heart failure with atrial fibrillation, also is recommended by some panelists for all Stage D patients, including those in sinus rhythm, lacking a concrete contraindication. (Class IIb, LOE: expert opinion)

Sildenafil (1‐2 mg/kg PO q8h) may be useful in the management of patients with clinical signs related to exertion and in management of ascites when there is echocardiographic evidence of moderate to severe pulmonary hypertension.95 (Class IIa, LOE: weak)

Beta blockade may be useful in decreasing the ventricular response rate in atrial fibrillation after stabilization and digitalization, but caution should be used because of the negative inotropic effects of beta blockers. (Class IIb, LOE: expert opinion)

The majority of panelists felt that beta blockade initiated previously should not be stopped, but that dosage reduction may be needed if shortness of breath cannot be controlled by the addition of other medications or if bradycardia, hypotension, or both were present. (Class IIb, LOE: expert opinion)

Cough suppressants are recommended to treat chronic, intractable cough in Stage D home care patients by some panelists. (Class IIa, LOE: expert opinion)

Bronchodilators are recommended to treat chronic, intractable coughing in Stage D home care patients by some panelists. (Class IIb, LOE: expert opinion)

6.6.4. Recommendation for chronic (home‐based) dietary treatment for Stage D

All of the dietary considerations for Stage C (above) apply.

In patients with refractory fluid accumulations, attempts should be made to further decrease dietary sodium intake if it can be done without compromising appetite or renal function. (Class IIa, LOE: expert opinion)

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DECLARATION

Bruce W. Keene—Consulted for Boehringer Ingelheim and CEVA Animal Health.

Clarke E. Atkins—Consulted for Boehringer Ingelheim and CEVA Animal Health.

John D. Bonagura —Consulted for Boehringer Ingelheim, IDEXX and CEVA Animal Health.

Philip R. Fox—Consulted for Boehringer Ingelheim, IDEXX and CEVA Animal Health.

Jens Häggström—Consulted for Boehringer Ingelheim, IDEXX and CEVA Animal Health.

Virginia Luis Fuentes—Consulted for Boehringer Ingelheim and CEVA Animal Health.

Mark A. Oyama—Consulted for Boehringer Ingelheim, CEVA Animal Health, and IDEXX.

John E. Rush—Consulted for Boehringer Ingelheim and IDEXX.

Rebecca Stepien—Consulted for Boehringer Ingelheim and IDEXX.

Masami Uechi—Consulted for Boehringer Ingelheim and TERUMO Corporation.

OFF‐LABEL ANTIMICROBIAL DECLARATION

Authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials.

INSTITUTIONAL ANIMAL CARE AND USE COMMITTEE (IACUC) OR OTHER APPROVAL DECLARATION

Authors declare no IACUC or other approval was needed.

HUMAN ETHICS APPROVAL DECLARATION

Authors declare human ethics approval was not needed for this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was presented in part at the 2017 ACVIM Forum, Seattle, WA, in the plenary program.

Keene BW, Atkins CE, Bonagura JD, et al. ACVIM consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2019;33:1127–1140. 10.1111/jvim.15488

Consensus Statements of the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) provide the veterinary community with up‐to‐date information on the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of clinically important animal diseases. The ACVIM Board of Regents oversees selection of relevant topics, identification of panel members with the expertise to draft the statements, and other aspects of assuring the integrity of the process. The statements are derived from evidence‐based medicine whenever possible and the panel offers interpretive comments when such evidence is inadequate or contradictory. A draft is prepared by the panel, followed by solicitation of input by the ACVIM membership which may be incorporated into the statement. It is then submitted to the Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, where it is edited prior to publication. The authors are solely responsible for the content of the statements.

REFERENCES

- 1. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:776‐803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boller M, Fletcher DJ. RECOVER evidence and knowledge gap analysis on veterinary CPR. Part 1: evidence analysis and consensus process: collaborative path toward small animal CPR guidelines. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2012;22(Suppl.1):S4‐S12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fox PR. Pathology of myxomatous mitral valve disease in the dog. J Vet Cardiol. 2012;14:103‐126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meurs KM, Friedenberg SG, Williams B, et al. Evaluation of genes associated with human myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs with familial myxomatous mitral valve degeneration. Vet J. 2018;232:16‐19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Madsen MB, Olsen LH, Häggström J, et al. Identification of 2 loci associated with development of myxomatous mitral valve disease in cavalier king charles spaniels. J Hered. 2011;102:S62‐S67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Borgarelli M, Buchanan JW. Historical review, epidemiology and natural history of degenerative mitral valve disease. J Vet Cardiol. 2012;14:93‐101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Borgarelli M, Zini E, D'Agnolo G, et al. Comparison of primary mitral valve disease in German shepherd dogs and in small breeds. J Vet Cardiol. 2004;6:27‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Borgarelli M, Häggström J. Canine degenerative myxomatous mitral valve disease: natural history, clinical presentation and therapy. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2010;40:651‐663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Häggström J, Höglund K, Borgarelli M. An update on treatment and prognostic indicators in canine myxomatous mitral valve disease. J Small Anim Pract. 2009;5:25‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Olsen LH, Fredholm M, Pedersen HD. Epidemiology and inheritance of mitral valve prolapse in dachshunds. J Vet Intern Med. 1999;13:448‐456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Aupperle H, Disatian S. Pathology, protein expression and signaling in myxomatous mitral valve degeneration: comparison of dogs and humans. J Vet Cardiol. 2012;14(1):59‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Han RI, Black A, Culshaw GJ, French AT, Else RW, Corcoran BM. Distribution of myofibroblasts, smooth muscle‐like cells, macrophages, and mast cells in mitral valve leaflets of dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease. Am J Vet Res. 2008;69:763‐769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yang VK, Loughran KA, Meola DM, et al. Circulating exosome microRNA associated with heart failure secondary to myxomatous mitral valve disease in a naturally occurring canine model. J Extracell Vesicles. 2017;6(1):1350088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Markby G, Summers KM, MacRae VE, et al. Myxomatous degeneration of the canine mitral valve: from gross changes to molecular events. J Comp Pathol. 2017;156;156:371‐383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Markby G, Summers K, MacRae V, et al. Comparative transcriptomic profiling and gene expression for myxomatous mitral valve disease in the dog and human. Vet Sci. 2017;4:3,E34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Corcoran BM, Black A, Anderson H, et al. Identification of surface morphologic changes in the mitral valve leaflets and chordae tendineae of dogs with myxomatous degeneration. Am J Vet Res. 2004;65:198‐206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Han RI, Black A, Culshaw G, French AT, Corcoran BM. Structural and cellular changes in canine myxomatous mitral valve disease: an image analysis study. J Heart Valve Dis. 2010;19:60‐70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hadian M, Corcoran BM, Bradshaw JP. Molecular changes in fibrillar collagen in myxomatous mitral valve disease. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2010;19:e141‐e148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sargent J, Connolly DJ, Watts V, et al. Assessment of mitral regurgitation in dogs: comparison of results of echocardiography with magnetic resonance imaging. J Small Anim Pract. 2015;56:641‐650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pedersen HD, Lorentzen KA, Kristensen KB. Echocardiographic mitral valve prolapse in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels: epidemiology and prognostic significance for regurgitation. Vet Rec. 1999;144:315‐320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mow T, Pedersen HD. Increased endothelin‐receptor density in myxomatous canine mitral valve leaflets. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1999;34:254‐260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cremer SE, Moesgaard SG, Rasmussen CE, et al. Alpha‐smooth muscle actin and serotonin receptors 2A and 2B in dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease. Res Vet Sci. 2015;100:197‐206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Oyama M a, Levy RJ. Insights into serotonin signaling mechanisms associated with canine degenerative mitral valve disease. J Vet Intern Med. 2010;24:27‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Menciotti G, Borgarelli M, Aherne M, et al. Mitral valve morphology assessed by three‐dimensional transthoracic echocardiography in healthy dogs and dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease. J Vet Cardiol. 2017;19(2):113‐123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Buchanan JW. Chronic valvular disease (endocardiosis) in dogs. Adv Vet Sci Comp Med. 1977;21:75‐106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sargent J, Muzzi R, Mukherjee R, et al. Echocardiographic predictors of survival in dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease. J Vet Cardiol. 2015;17:1‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hezzell MJ, Falk T, Olsen LH, Boswood A, Elliott J. Associations between N‐terminal procollagen type III, fibrosis and echocardiographic indices in dogs that died due to myxomatous mitral valve disease. J Vet Cardiol. 2014;16:257‐264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Peddle GD, Singletary GE, Reynolds CA, Trafny DJ, Machen MC, Oyama MA. Effect of torsemide and furosemide on clinical, laboratory, radiographic and quality of life variables in dogs with heart failure secondary to mitral valve disease. J Vet Cardiol. 2012;14:253‐259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Reynolds CA, Brown DC, Rush JE, et al. Prediction of first onset of congestive heart failure in dogs with degenerative mitral valve disease: the PREDICT cohort study. J Vet Cardiol. 2012;14:193‐202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lord PF, Hansson K, Carnabuci C, Kvart C, Häggström J. Radiographic heart size and its rate of increase as tests for onset of congestive heart failure in cavalier king Charles spaniels with mitral valve regurgitation. J Vet Intern Med. 2011;25:1312‐1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hezzell MJ, Boswood A, Moonarmart W, Elliott J. Selected echocardiographic variables change more rapidly in dogs that die from myxomatous mitral valve disease. J Vet Cardiol. 2012;14:269‐279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Atkins C, Bonagura J, Ettinger S, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of canine chronic valvular heart disease. J Vet Intern Med. 2009;23:1142‐1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Birkegård AC, Reimann MJ, Martinussen T, et al. Breeding restrictions decrease the prevalence of myxomatous mitral valve disease in cavalier king Charles spaniels over an 8‐ to 10‐year period. J Vet Intern Med. 2015;30:63‐68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Swift S, Baldin A, Cripps P. Degenerative valvular disease in the cavalier king Charles spaniel: results of the UK breed scheme 1991‐2010. J Vet Intern Med. 2017;31:9‐14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Crippa L, Ferro E, Melloni E, Brambilla P, Cavalletti E. Echocardiographic parameters and indices in the normal beagle dog. Lab Anim. 1992;26:190‐195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Misbach C, Lefebvre HP, Concordet D, et al. Echocardiography and conventional Doppler examination in clinically healthy adult cavalier king Charles spaniels: effect of body weight, age, and gender, and establishment of reference intervals. J Vet Cardiol. 2014;16:91‐100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jacobson JH, Boon JA, Bright JM. An echocardiographic study of healthy border collies with normal reference ranges for the breed. J Vet Cardiol. 2013;15:123‐130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Morrison SA, Moise NS, Scarlett J, Mohammed H, Yeager AE. Effect of breed and body weight on echocardiographic values in four breeds of dogs of differing somatotype. J Vet Intern Med. 1992;6:220‐224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. O'Leary CA, Mackay BM, Taplin RH, et al. Echocardiographic parameters in 14 healthy English bull terriers. Aust Vet J. 2003;81:535‐542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bavegems V, Duchateau L, Sys SU, et al. Echocardiographic reference values in whippets. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2007;48:230‐238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Trafny DJ, Freeman LM, Bulmer BJ, et al. Auscultatory, echocardiographic, biochemical, nutritional, and environmental characteristics of mitral valve disease in Norfolk terriers. J Vet Cardiol. 2012;14:261‐267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Strohm LE, Visser LC, Chapel EH, Drost WT, Bonagura JD. Two‐dimensional, long‐axis echocardiographic ratios for assessment of left atrial and ventricular size in dogs. J Vet Cardiol. 2018;20(5):330‐342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Boswood A, Häggström J, Gordon SG, et al. Die Wirkung von Pimobendan bei Hunden mit präklinischer myxomatöser Mitralklappenerkrankung und Kardiomegalie: Die EPIC‐Studie—Eine randomisierte klinische Studie. Kleintierpraxis. 2018;62(2):64‐87. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Boswood A, Häggström J, Gordon SG, et al. Effect of Pimobendan in dogs with preclinical myxomatous mitral valve disease and cardiomegaly: the EPIC study—a randomized clinical trial. J Vet Intern Med. 2016;30:1765‐1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hansson K, Häggström J, Kvart C, et al. Left atrial to aortic root indices using two‐dimensional and M‐mode echocardiography in cavalier king Charles spaniels with and without left atrial enlargement. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2002;43:568‐575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cornell CC, Kittleson MD, Torre PD, et al. Allometric scaling of M‐mode C cardiac measurements in normal adult dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2004;18:311‐321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lamb CR, Wikeley H, Boswood A, Pfeiffer DU. Use of breed‐specific ranges for the vertebral heart scale as an aid to the radiographic diagnosis of cardiac disease in dogs. Vet Rec. 2001;148:707‐711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Birks R, Fine DM, Leach SB, et al. Breed‐specific vertebral heart scale for the dachshund. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2017;53:73‐79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kraetschmer S, Ludwig K, Meneses F, Nolte I, Simon D. Vertebral heart scale in the beagle dog. J Small Anim Pract. 2008;49:240‐243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Choisunirachon N, Kamonrat P. Vertebral scale system to measure heart size in radiographs of Shih‐Tzus. Thai J Vet Med. 2008;38(1):60. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jepsen‐Grant K, Pollard RE, Johnson LR. Vertebral heart scores in eight dog breeds. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2013;54:3‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Marin LM, Brown J, McBrien C, et al. Vertebral heart size in retired racing greyhounds. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2007;48:332‐334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bavegems V, Van Caelenberg A, Duchateau L. Vertebral heart size ranges specific for whippets. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2005;46:400‐403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Malcolm EL, Visser LC, Phillips KL, Johnson LR. Diagnostic value of vertebral left atrial size as determined from thoracic radiographs for assessment of left atrial size in dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2018;253(8):1038‐1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Boswood A, Gordon SG, Häggström J, et al. Longitudinal analysis of quality of life, clinical, radiographic, echocardiographic, and laboratory variables in dogs with preclinical myxomatous mitral valve disease receiving pimobendan or placebo: the EPIC study. J Vet Intern Med. 2018;32:72‐85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Freeman LM, Rush JE, Markwell PJ. Effects of dietary modification in dogs with early chronic valvular disease. J Vet Intern Med. 2006;20:1116‐1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kvart C, Häggström J, Pedersen HD, et al. Efficacy of enalapril for prevention of congestive heart failure in dogs with myxomatous valve disease and asymptomatic mitral regurgitation. J Vet Intern Med. 2002;16:80‐88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Atkins CE, Keene BW, Brown WA, et al. Results of the veterinary enalapril trial to prove reduction in onset of heart failure in dogs chronically treated with enalapril alone for compensated, naturally occurring mitral valve insufficiency. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2007;231:1061‐1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pouchelon JL, Jamet N, Gouni V, et al. Effect of benazepril on survival and cardiac events in dogs with asymptomatic mitral valve disease: a retrospective study of 141 cases. J Vet Intern Med. 2008;22:905‐914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hezzell MJ, Boswood A, López‐Alvarez J, Lötter N, Elliott J. Treatment of dogs with compensated myxomatous mitral valve disease with spironolactone—a pilot study. J Vet Cardiol. 2017;19:325‐338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mizuno T, Mizukoshi T, Uechi M. Long‐term outcome in dogs undergoing mitral valve repair with suture annuloplasty and chordae tendinae replacement. J Small Anim Pract. 2013;54:104‐107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Uechi M. Mitral valve repair in dogs. J Vet Cardiol. 2012;14:185‐192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Uechi M, Mizukoshi T, Mizuno T, et al. Mitral valve repair under cardiopulmonary bypass in small‐breed dogs: 48 cases (2006‐2009). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2012;240:1194‐1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Oyama MA, Fox PR, Rush JE, Rozanski EA, Lesser M. Clinical utility of serum N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide concentration for identifying cardiac disease in dogs and assessing disease severity. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008;232:1496‐1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Oyama MA, Rush JE, Rozanski EA, et al. Assessment of serum N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide concentration for differentiation of congestive heart failure from primary respiratory tract disease as the cause of respiratory signs in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2009;235:1319‐1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Adin DB, Taylor AW, Hill RC, Scott KC, Martin FG. Intermittent bolus injection versus continuous infusion of furosemide in normal adult greyhound dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2003;17:632‐636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Adin D, Atkins C, Papich MG. Pharmacodynamic assessment of diuretic efficacy and braking in a furosemide continuous infusion model. J Vet Cardiol. 2018;20:92‐101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Suzuki S, Fukushima R, Ishikawa T, et al. The effect of pimobendan on left atrial pressure in dogs with mitral valve regurgitation. J Vet Intern Med. 2011;25:1328‐1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sabbah HN, Levine TB, Gheorghiade M, Kono T, Goldstein S. Hemodynamic response of a canine model of chronic heart failure to intravenous dobutamine, nitroprusside, enalaprilat, and digoxin. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 1993;7:349‐356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Sisson DD et al. Acute and short‐term hemodynamic, echocardiography, and clinical effects of enalapril maleate in dogs with naturally acquired heart failure: results of the invasive multicenter PROspective veterinary evaluation of Enalapril study: the IMPROVE study group. J Vet Intern Med. 1995;9:234‐242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Nakayama T, Nishijima Y, Miyamoto M, Hamlin RL. Effects of 4 classes of cardiovascular drugs on ventricular function in dogs with mitral regurgitation. J Vet Intern Med. 2007;21:445‐450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Parameswaran N, Hamlin RL, Nakayama T, Rao SS. Increased splenic capacity in response to transdermal application of nitroglycerine in the dog. J Vet Intern Med. 1999;13:44‐46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]