Abstract

This study examines convergent and divergent validity for middle childhood anxious solitude, unsociability, and peer exclusion as assessed by five informants (peers, teachers, observers, the self, and parents). Participants were 163 (67 male, 96 female) third grade children (M age = 8.70 years). Parent reports were available for a subset of the sample (N = 95). Validity was analyzed via multitrait–multimethod correlation matrices and structural equation models. Results indicate that anxious solitude and peer exclusion have better convergent and divergent validity than unsociability, although there is evidence of shared method variance for all constructs. Peers have the best combination of convergent and divergent validity, and parents, the worst; teachers, observers, and the self demonstrated mid-level validity.

Keywords: social withdrawal, social anxiety, unsociability, peer exclusion

The importance of studying childhood solitude is underscored by research indicating that solitary children (especially anxious solitary [AS] children), compared with others, experience higher rates of peer rejection and exclusion, poor social self-concept, loneliness, and depressive symptoms throughout middle childhood and adolescence (e.g., Gazelle & Ladd, 2003; Hymel, Rubin, Rowden, & LeMare, 1990; Morison & Masten, 1991; Rubin, Chen, McDougall, Bowker, & McKinnon, 1995; Rubin & Mills, 1988), and difficulties with adult developmental tasks, such as entry into marriage and a stable career for men with a childhood history of solitude (Caspi, Elder, & Bem, 1988; see also Kerr, Lambert, & Bem, 1996), and providing responsive parenting for women with a childhood history of solitude (Serbin, Cooperman, Peters, Lehoux, Stack, & Schwartzman, 1998). Yet integrating findings from multiple investigations on childhood solitude is often a challenge for two reasons: Across investigations, assessments often (1) capture different forms of solitude, and (2) derive from different informants. This investigation is a systematic examination of which forms and informants of solitude are best supported by empirical evidence.

Forms of Solitude

Contemporary research on solitude in middle childhood identifies three major forms: AS, unsociability, and peer exclusion (Asendorpf, 1990; Coplan, Prakash, O’Neil, & Armer, 2004; Gazelle & Ladd, 2003). Both AS and unsociability locate the impetus for solitude within the child whereas peer exclusion locates the impetus for solitude externally in the interpersonal environment. Work on childhood solitude sometimes does not distinguish between these different forms, but rather uses the umbrella term ‘social withdrawal’ to designate children who play alone among peers at elevated rates, for whatever reason. All constructs refer to solitude that occurs in a context in which familiar peers are available as potential playmates (e.g., such as school recess).

Both internally-based forms of solitude, AS and unsociability, are affective/behavioral/motivational constructs. AS is conceptualized as solitary behavior that is prompted by social anxiety (affect) (Gazelle & Ladd, 2003), comprised in part of ‘social evaluative concerns’ (e.g., worry that peers will disapprove of one’s behavior) (Coplan, 2000; Coplan & Rubin, 1998). Shyness, verbal inhibition, and onlooking solitary behavior (watching other children play without joining in) are behavioral hallmarks of AS (Coplan, Rubin, Fox, Calkins, & Stewart, 1994). The motivational underpinnings of AS are conceptualized as conflict between normative social approach and heightened social avoidance motivations (e.g., as manifested in onlooking behavior) (Asendorpf, 1990). Thus, children high in AS are conceptualized as wanting to play with their peers but being blocked by social anxiety.

In contrast, unsociability refers to playing alone due to social disinterest (low social approach and low social avoidance motivations) (Asendorpf, 1990). In other words, children high in unsociability want to play alone. Unsociability is often conceptualized as being accompanied by neutral or positive affect (especially a lack of social anxiety; Harrist, Zaia, Bates, Dodge, & Pettit, 1997). However, it is problematic to use affect as the primary identification criteria for unsociability because lack of anxiety is not equivalent to the presence of social disinterest/low social approach motivation. Thus, studies that identify unsociable children via lack of anxiety (e.g., Harrist et al.) actually form a default catch-all category that may have members who are heterogeneous in regard to social disinterest. In regard to behavior, some have suggested that absorption in objects (object-focus) occurs with unsociability (Jennings, 1975). This possibility would suggest that the behavioral manifestation of unsociability would be directed solitary play (for instance, manipulating objects; at recess, this would include such activities as solitary swinging and ball bouncing) (Coplan et al., 2004). However, neither the affective nor the behavioral components of unsociability have been the subject of much empirical investigation, and therefore do not have substantial empirical support.

Peer exclusion refers to solitude that is imposed externally when peers leave a child out of their activities (Gazelle & Ladd, 2003). Exclusion can happen both passively (a child is ignored at recess) and actively (peers refuse to allow a child to sit with them or join their game). Although these three forms of solitude—AS, unsociability, and peer exclusion—are conceptually distinct as constructs, recent research suggests that they do not correspond to subgroups of children that are mutually exclusive (Coplan et al., 2004; Gazelle & Ladd; Gazelle & Rudolph, 2004).

In particular, research has indicated that there are substantial proportions of both excluded and non-excluded AS children (Gazelle & Ladd, 2003; Gazelle & Rudolph, 2004). Therefore, solitude appears primarily motivated from within for some children, but for other children, simultaneously maintained by both internal and external forces. This distinction has proven to be substantively and theoretically important, because the joint internal and external (or child × environment) forces of AS and peer exclusion vs. AS alone predict more stability in AS and more internalizing symptoms over time (Gazelle & Ladd; Gazelle & Rudolph). Consequently, AS and peer exclusion were expected to be distinct but positively correlated constructs.

Less is known about the co-occurrence of unsociability with other forms of solitude, although one study demonstrated a positive concurrent association between parent-reported unsociability and teacher-reported exclusion among preschool children (Coplan et al., 2004). Furthermore, there has been some indication that unsociability (when assessed as observed directed solitary or ‘solitary passive’ behavior) becomes increasingly related to peer relations difficulties (as reported by both peers and teachers) with age (Coplan, Gavinski-Molina, Lagace-Seguin, & Wichmann, 2001; Rubin & Mills, 1988; see also Coplan et al., 1994 for discussion). This increasing relation may occur because this orientation is perceived as increasingly deviant by peers, as most children spend increasing time in interactive peer play with age. Thus, there is reason to expect a degree of co-occurrence between unsociability and exclusion by third grade, but less is known about the co-occurrence of unsociability and AS. Conceptually, the definition of unsociability would appear to preclude AS, but it is unclear whether or not empirical evidence supports this conceptual distinction. Empirical evidence is lacking both because unsociability is (1) rarely included in examinations of divergent validity among multiple forms of childhood solitude, and (2) typically studied as a dimension without identifying groups that are either ‘pure’ or defined by the co-occurrence of other forms of solitude. This investigation examines all three forms of solitude as dimensions. Unsociability was expected to be positively correlated with the other two forms of solitude. The present analysis was expected to address the empirical basis for considering unsociability as distinct from other forms of solitude.

Informants of Solitude

Contemporary assessment of childhood solitude relies on one or more of five possible informants: peers, teachers, observers, the self, and parents. Investigations often rely on a single informant to rate the degree to which children display these forms of solitude. Although some studies report degree of convergence among multiple informants of solitude (Gazelle & Ladd, 2003; Ledingham, Younger, Schwartzman, & Bergeron, 1982), these studies typically examine convergence among two, or more rarely, three informants. Furthermore, the most time-intensive forms of assessment (e.g., behavioral observation) are often absent from such examinations of multi-informant convergence. Thus, there is a need to examine all five informants within a single study.

Each informant of childhood solitude has strengths and weaknesses. Strengths of peer reports include an ‘inside perspective’ (peer relations from the perspective of peers themselves), multiple informants (which diminish single-informant biases and augment reliability), and access to relevant contexts to observe solitary behavior among peers (school: recess as well as the classroom), whereas weaknesses include questionable reliability of peer perceptions of solitude prior to third grade (Bukowski, 1990; Crozier & Burnham, 1990; Younger, Schwartzman, & Ledingham, 1985, 1986) and potential discrepancies between the strength of peer reputation and rate of occurrence (Gazelle in press). Strengths of teachers include access to relevant environments (school: the classroom more so than recess) and familiarity with a relatively large number of age mates as a frame of reference, whereas weaknesses include bias stemming from the role of teacher (e.g., salience of behaviors that cause disruption of instructional activities rather than typically non-disruptive solitary behaviors) and time-limited knowledge of children (often limited to the present school year). Strengths of observers include ratings based on objective criteria, access to relevant environments (e.g., school), and information about rate of occurrence, whereas weaknesses include the limited time in which observers’ ratings are made. Strengths of parents include extensive knowledge of the child’s history (typically from birth), whereas weaknesses include limited access to relevant environments (e.g., school where solitude among peers often occurs) and biases related to the role of parent (e.g., investment in seeing one’s child in a positive light). Finally, strengths of child self reports include direct access to the child’s subjective experience and social motivation, whereas weaknesses include biases common to self reports in general (e.g., the fundamental attribution error in which negative information about others is attributed to personality, whereas negative information about the self is attributed to the situation; Pronin, Lin, & Ross, 2002), self reports from children in particular (young children may have limited insight about the self), as well as those that may be specific to solitary children in particular (e.g., less time interacting with others may translate into a less normative frame of reference in solitary children).

Although each informant of childhood solitude has strengths and weaknesses, some informants are preferred over others. In the developmental literature, a preference for either peer report (at least beginning in third grade, e.g., Gazelle, Putallaz, Li, Grimes, Kupersmidt, & Coie, 2005) or behavioral observation (e.g., Rubin & Mills, 1988) is typical because of the multiple strengths of these methods, although the three other methods are also sometimes employed either as primary forms of measurement or to establish convergence (e.g., Gazelle & Ladd, 2003). Because the forms of assessment preferred by developmentalists are the two most time-intensive (peer sociometrics in part due to the time required to gather permission for large numbers of students and achieve a high proportion of participants in each classroom, and observation due to the time-intensive nature of the assessment itself), it is important to empirically establish that they are worthy of this investment in time and resources. Additionally, it is valuable to establish empirically the degree to which other forms of assessment correspond to these preferred methods in order to make informed decisions when multiple informants are desired or it is not possible to use preferred assessment methods. We expected that certain informants would correspond more strongly than others based on past evidence and two principles: (1) shared environment: greater correspondence should be achieved among participants who share an environment (e.g. the school environment) (Achenbach, McConaughy, & Howell, 1987), and (2) self-biases: self-reports have certain inherent biases (Pronin et al., 2002).

Because the behaviors of interest occur among familiar peers at school, the degree to which informants have direct access to the school environment was expected to be a major source of convergence or the lack thereof. Consequently, peers, teachers, observers, and the self were expected to agree with one another more strongly than with parents (Achenbach et al., 1987). However, this general expectation must be qualified by the strengths and weaknesses of each method as previously enumerated. Additionally, the same principle would suggest that shared home environment may also lead to convergence between the self and parents (although behaviors of interest occur among peers at school). Finally, we expected self-biases to diminish convergence among the self and other informants, including those who share the school environment.

Gender Differences

Equal prevalence of elevated AS among boys and girls is typically found in the developmental literature (Coplan et al., 2001), although clinically significant social anxiety is more common among girls than boys in clinical investigations (Albano & Krain, 2005). Thus, any difference in prevalence should favor girls. Additionally, the co-occurrence of AS and peer exclusion or victimization has been found for children of both sexes (Gazelle et al., 2005), although this relation appears somewhat stronger for boys in early middle childhood (Gazelle & Ladd, 2003). This may occur because AS is a greater violation of male gender norms emphasizing self-confidence and dominance (Caspi et al., 1988; Coplan et al.). Thus, it is possible that AS and peer exclusion would be more strongly correlated in boys than girls. Because the degree of correlation among constructs impacts divergent validity, empirical evidence for valid forms and informants of solitude will be examined for children both combined and separated by sex.

Hypotheses

It was hypothesized that a model differentiating between AS, unsociability, and peer exclusion would (1) demonstrate adequate fit, (2) indicate that these forms of solitude are positively correlated, and (3) that the improvement in fit between models that do and do not distinguish unsociability from other forms of solitude would be modest.1 Additionally, (4) it was expected that all five informants of solitude would make significant contributions to each construct, thus demonstrating acceptable convergent validity. In particular, peers, teachers, and observers were expected to demonstrate relatively strong contributions to constructs. (5) All informants were expected to demonstrate some shared method variance (i.e., to have significant standardized same-informant error covariances), a common condition that limits divergent validity. (6) Finally, it was expected that AS and peer exclusion might be more highly correlated in boys than girls, resulting in better divergent validity for girls.

Method

Participants

Participants were 163 children with informed parental consent from a larger screening sample of 688 children from 46 third grade classrooms in seven public elementary schools. Approximately half of these participants (N = 80) were selected because they scored at or above 1 SD on the peer-reported AS composite. An approximately equal number of children who scored below 1 SD on the peer-reported AS composite were selected as demographically matched controls (N = 83) to eliminate potential demographic confounds for differences among AS and non-AS children. Controls were selected as the closest demographic match for AS children in regard to sex, ethnicity, age, classroom, and free- or reduced-lunch status. Because control children were selected without regard to behavior (except that they were below 1 SD in AS), the full distribution of all forms of solitude was retained in the selected sample, although children high in AS were oversampled. Additional analyses suggest that this oversampling did not substantially impact the structure of relations among forms of solitude.2

Selected vs. non-selected children in the screening sample did not differ in age (selected M = 8.70 years, SD = .55, non-selected M = 8.65 years, SD = .48, t = .94, NS) or in rate of free or reduced lunch (selected 31 percent, non-selected 29 percent, χ2 = .23, NS). There was a higher frequency of female (59 percent) than male (41 percent) selected children in comparison with non-selected screening children (female 49 percent, male 51 percent, χ2 = 4.74, p < .05). The race/ethnicity of the selected sample is diverse and resembles the composition of the screening sample except that marginally more Latino (χ2 = 3.53, p < .10) and significantly fewer African-American children (χ2 = 6.19, p < .05) were selected (selected vs. non-selected: 64 percent vs. 61 percent European-American, 21 percent vs. 15 percent Latino, 14 percent vs. 23 percent African-American, and 2 percent vs. 2 percent Asian-American). Because children were selected on the basis of elevated AS scores (or having demographics that matched those of AS children), demographic discrepancies between the screening and selected samples are a result of differential prevalence of elevated AS among demographic groups in this sample. Greater prevalence of AS among girls than boys is consistent with some developmental literature (Burgess, Wojslawowicz, Rubin, Rose-Krasnor, & Booth-LaForce, 2006; Rubin, Wojslawowicz, Rose-Krasnor, Booth-LaForce, & Burgess, 2006) and the majority of clinical literature (Albano & Krain, 2005). Ethnic differences were not hypothesized and are not necessarily related to culture. The tendency toward elevated AS among Latino children may be related to stressful economic or acculturation conditions.

Third grade is a particularly opportune age period to study the structure of multiple forms of solitude from the perspective of multiple informants. Firstly, little information about the structure of different forms of solitude is available in this age period (most work distinguishing between AS and unsociability has been conducted with preschool and kindergarten-age children; Coplan, 2000; Coplan & Rubin, 1998; Coplan et al., 1994, 2004). Secondly, third grade is the earliest developmental period for which empirical evidence supports the validity of children’s self- and peer- reports of solitude (Bukowski, 1990; Crozier & Burnham, 1990; Younger et al., 1985, 1986).

Measures

Each form of solitude was assessed by five informants: peers, teachers, observers, the self, and parents. Assessments are described by informant and construct in turn.

Peer Reports

Peer sociometrics were administered simultaneously to participating children in each classroom in the fall at least two months after the beginning of the school year. The percentage of participating children in each class ranged from 70 percent to 100 percent (M = 81 percent). Items were adapted from previously established sociometric question sets (e.g., Gazelle & Ladd, 2003). Each nomination was read aloud to the class, and then children selected classmates’ names on their individual class rosters. Nominations were unlimited and cross-sex nominations were allowed because these procedures result in superior psychometric properties (Foster, Bell-Dolan, & Berler, 1986; Terry & Coie, 1991). Self-nominations were allowed; however, peer-and self-report composites were computed separately. Children’s scores on each item were equal to the total number of nominations they received from classmates. These scores were standardized by classroom to control for variation in classroom size.

An AS composite was computed as the mean of three items, with higher scores indicating higher levels of AS (α = .81): (1) ‘Some kids act really shy around other kids. They seem to be nervous or afraid to be around other kids and they don’t talk much. They often play alone at recess. Who are the kids in your class who are shy and play alone a lot?’; (2) ‘Some kids watch what other kids are doing but don’t join in. At recess they watch other kids play but they play by themselves. Who are the kids in your class who are shy and watch other kids but play alone a lot?’; and (3) ‘Some kids are very quiet. They don’t have much to say to other kids. Who in your class is shy and doesn’t have much to say to other kids?’.

A single item was used to identify unsociable behavior: ‘Some kids play alone a lot not because they’re shy or afraid, but because they like to play alone. Because these kids like to do things alone, they often don’t try to play with other kids. Who are the kids in your class who like to play alone but aren’t shy?’. Because of the multi-informant nature of peer nominations, even single items are reliable (Coie, Dodge, & Kupersmidt, 1990).

An exclusion composite was computed as the mean of two items identifying direct and indirect exclusion, with higher scores indicating higher levels of exclusion (α = .79): direct exclusion (1) ‘When some kids ask if they can play, other kids say “no” and won’t let them play. Who are the kids in your class who can’t play?’, and indirect exclusion (2) ‘Some kids get left out when other kids are talking and playing together. They don’t get invited to parties or chosen to be on teams or to be work partners. Who are the kids in your class who get left out and aren’t chosen?’.

Self Reports

Children completed self-nominations during the sociometric interview that were identical to peer nominations in content and scoring except they were not standardized by class size. Self reports demonstrated low to modest reliability (AS α = .57, exclusion α = .55).

Teacher Reports

Teachers rated how strongly each child’s fall behavior resembled specific behavioral profiles designed to closely match the content of peer nominations for the current study on a 5-point scale (0 for no resemblance to 4 for perfect resemblance). The AS profile was ‘children who, when with peers, act shy, don’t talk much, and seem to be nervous or self-conscious. They often play alone at recess and may sit alone at lunch or not have anyone to talk to at lunch’. The unsociable profile was ‘children who often play alone not because they’re shy or afraid, but because they like to play alone. Because these children like to do things alone, they often don’t try to play with other children’. The exclusion profile was ‘children who get left out when other children are talking or playing together. They don’t get invited to parties or chosen to be on teams or to be work partners’.

Recess Observations

Children were observed during naturalistic free play at school recess in the late fall through the spring (after peer, teacher, and self-assessments, and concurrently with parent assessments) for five five-minute intervals (on at least three separate days) for a total of 25 minutes of observed free play activity per child. The occurrence of mutually exclusive child behaviors and peer responses were coded live in 30-second observe, 30-second record intervals. Scores reported indicate the proportion of intervals that a behavior or peer response occurred (number of intervals code observed/total number of observational intervals). The peer interaction observational system (PIOS) was created for the present study. The PIOS was adapted from two existing observational systems: the play observation system (POS, the play observation scale [POS]; Rubin, 2001), which captures child behaviors, and a system developed by Putallaz and Wasserman (1989), which captures peers’ responses. Two graduate-level research assistants (RAs) were trained as follows. Firstly, the RAs and principal investigator attended a POS training session with Dr. Rubin and his staff. Secondly, the adapted coding system was employed live and refined on a pilot sample of children at free play until coders reached reliability. Subsequently, during data collection, RAs double coded 23.7 percent of the observations (approximately every fifth observation to insure maintenance of reliability). Inter-rater reliability (i.e., Cohen’s kappa, κ) was acceptable for all variables and is reported by construct below. The face validity of this coding system is supported by codes that reflect the key definitional behaviors or peer responses for each construct as described above. Moreover, these codes were adapted from well-established coding systems (Putallaz & Wasserman, 1989; Rubin, 2001; the play observation scale [POS], University of Maryland, 2001). The convergent and divergent validity of the observational system is reported in the Results section.

Codes relevant to the present analyses were the child codes ‘alone-onlooker,’ ‘alone-unoccupied,’ and ‘alone-directed,’ and the group responses ‘excluded’ and ‘ignore’. ‘Alone-onlooker’ was recorded when a child was within 10 ft of a peer group and visually attending to the group but made no attempt to join (κ = .90). ‘Alone-unoccupied’ was recorded when a child was alone but not engaged in any activity, such as wandering aimlessly or staring into space (κ = .86). ‘Alone-directed’ was recorded when a child was engaged in a solitary activity, such as swinging or playing on the slide (κ = .87). Group responses were coded as ‘excluded’ when peers directly told the target child he/she could not play or ran away from him/her, and ‘ignore’ when peers indirectly did not include the target child in their group activity or otherwise acknowledge the target child’s presence, but there were no additional indications of either rejection or acceptance (κ = .80 and .96, respectively). An exclusion composite was formed by summing ‘excluded’ and ‘ignore’.

Parent Reports

Parents completed an adapted version of the child behavior scale (Ladd & Profilet, 1996) in the spring. Parents assessed how strongly their child’s behavior resembled specific descriptors on a 3-point scale (0 ‘doesn’t apply’ to 2 ‘certainly applies’). Composites were computed as the mean of items reflecting AS (five items, including: shy with peers, watches or listens to peers without joining in; α = .61), unsociability (four items, including: not interested in peers, enjoys solitary activity while peers socialize; α = .65), and exclusion (five items, including: not chosen as playmate by peers, excluded from peers’ activities; α = .82). Higher scores indicate higher levels of AS, unsociability, or exclusion. Although attempts were made to obtain the questionnaire from parents of all participating children, only 95 (58 percent) were completed. Nonetheless, there were no significant differences between children whose parents did or did not complete the questionnaires in regard to any of the three peer-reported solitude constructs (ts =−.50–.60, NS).

Results

Analytic Plan

Results of the traditional multitrait–multimethod correlation matrix (MTMM matrix; Campbell & Fiske, 1959) analyses are presented for descriptive purposes, but the primary means of analysis was structural equation modeling (SEM; Kline, 2005) with AMOS 6.0 (Arbuckle, 2005). SEM was chosen as the primary analytic method because it permits more advanced examination of MTMM data than traditional methods (i.e., instead of examining zero-order correlations, it models unique contribution of an informant to a construct after controlling for the contribution of other informants and shared method variance). Also, whereas the strengths of different correlations are typically compared subjectively in traditional MTMM (Fisher’s Z is not appropriate for this application; Steiger [1980]), more straightforward statistical tests exist for SEM. For simplification, in the remainder of the text, ‘traits’ are referred to as ‘constructs’ and ‘methods’ as ‘informants’.

Using the traditional MTMM method, convergent and divergent validity were examined by correlating multiple constructs assessed by multiple informants. Convergent validity refers to the idea that concepts that are conceptually related and independently measured should be highly correlated. In other words, assessments of the same construct by different informants should converge. Divergent validity refers to the idea that concepts that are not conceptually related should not be highly correlated (regardless of whether or not they are assessed by the same or different informants). Divergent validity is indicative of informants’ ability to distinguish among constructs. Campbell and Fiske (1959) outlined two primary methods of assessing divergent validity. Firstly, multiple assessments of the same vs. different constructs should correlate more strongly when both are assessed by different informants (general divergent validity). Secondly, assessments of the same construct by different informants should correlate more strongly than they do with assessments of different constructs by the same informant (the shared method variance component of divergent validity). If this criterion is satisfied, different constructs are thought to be truly correlated; however, failure to meet this criterion raises the possibility that correlations may be due to the perspective or bias of a specific informant type.

In SEM, convergent and divergent validity were assessed via confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), which models each of multiple informants’ contributions to each of multiple constructs. Convergent validity is measured by examining the strength of each informant’s loading on each latent construct, with stronger loadings indicating stronger convergent validity. The general form of divergent validity is assessed by examining the correlations among latent constructs, with high correlations being indicative of poor general divergent validity. Shared method variance is modeled by allowing error terms for each informant to correlate across constructs (this is referred to as a correlated trait–correlated uniqueness model; Kline, 2005; Lance, Noble, & Scullen, 2002). High correlations among error terms indicate high shared method variance. An alternate to MTMM analyses is the correlated trait–correlated method approach, in which constructs and informants are each modeled as latent constructs, but this method often does not converge (Lance et al., 2002), as was the case in the current study.

In SEM, models are typically judged to be a good fit for the data when they demonstrate superior fit relative to alternate models. Thus, a three-factor model in which AS, unsociability, and exclusion are distinguished from one another is compared with alternate two- and one-factor models. Finally, in addition to computing a combined-sex CFA, a sex-differentiated multi-group CFA was computed and tested for measurement invariance to examine gender differences.

Traditional MTMM Analysis

A correlation matrix was computed to examine convergent and divergent validity of AS, unsociability, and peer exclusion as assessed by five informants (see Table 1). Although it was originally expected that observed directed solitary play would be indicative of unsociability (Coplan et al., 1994), significant correlations emerged between self-reported unsociability and observed unoccupied solitary behavior (r = .25, p < .001) rather than directed solitary behavior (r = −.06, NS). Self-reported unsociability was assigned particular importance because (1) it is the only direct source of information on motivation, and (2) behavioral and affective indicators of unsociability are not well established empirically. Therefore, unoccupied solitary behavior served as the observed index of unsociability. Consequently, unoccupied solitary behavior was not combined with onlooking solitary behavior to form a reticence composite, and onlooking solitary behavior was employed as the sole observed index of AS.

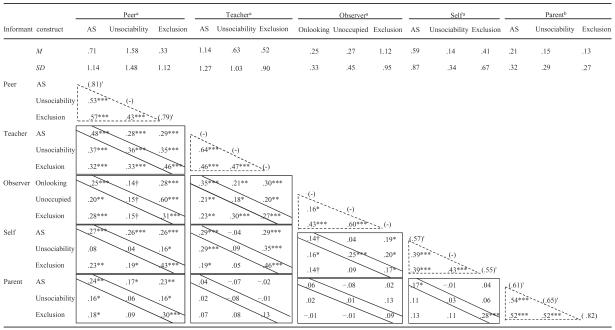

Table 1. Multitrait-Multimethod Correlation Matrix for Children’s Anxious Solitude, Unsociability, and Peer Exclusion by Five Informants.

Note: Parentheses indicate Cronbach’s alphas. (–) Cronbach’s alpha not computed for single-item measures. Values in diagonals are same construct–different informant correlations (convergent validity). Values in solid triangles are different construct–different informant correlations (general divergent validity). Values in triangles with dashed lines are different construct–same informant correlations (shared method variance component of divergent validity).

† p < .10

* p < .05

** p < .01

*** p < .001

a N = 163.

b N = 95.

AS = Anxious solitude.

Convergent Validity

In keeping with the principle of convergent validity, which states that independent measures of the same construct should correlate strongly (Campbell & Fiske, 1959), multi-informant autocorrelations (see validity diagonals in Table 1) were examined for AS, unsociability, and peer exclusion. Results indicate greater mean convergent validity for AS and exclusion than for unsociability (M rs = .23, .29 vs. .11, respectively; see mean CV values in Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of Multitrait–Multimethod Correlation Matrix Indicating Convergent and Divergent Validity by Construct and Informant Pairs.

| Anxious solitude |

Unsociability |

Exclusion |

Mean by informant pair |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV |

DV |

SMV |

CV |

DV |

SMV |

CV |

DV |

SMV |

CV |

DV |

SMV |

|||||||

| Informant | r | Highest DCDI |

% CV > DCDI |

Highest DCSI |

% CV > DCSI |

r | Highest DCDI |

% CV > DCDI |

Highest DCSI |

% CV > DCSI |

r | Highest DCDI |

% CV > DCDI |

Highest DCSI |

% CV > DCSI |

r | % CV > DCDI |

% CV > DCSI |

| Peer–teacher | .48 | .37 | 100 | .64 | 0 | .36 | .37 | 75 | .64 | 0 | .46 | .35 | 100 | .57 | 50 | .43 | 92 | 17 |

| Peer–observer | .25 | .28 | 50 | .57 | 25 | .15 | .60 | 50 | .60 | 0 | .31 | .28 | 100 | .60 | 0 | .24 | 67 | 8 |

| Peer–self | .27 | .26 | 100 | .57 | 0 | .04 | .27 | 0 | .53 | 0 | .43 | .26 | 100 | .57 | 75 | .25 | 67 | 25 |

| Peer–parent | .24 | .23 | 100 | .61 | 0 | .06 | .17 | 0 | .54 | 0 | .30 | .23 | 100 | .57 | 0 | .20 | 67 | 0 |

| Teacher–observer | .35 | .30 | 100 | .64 | 25 | .18 | .30 | 0 | .64 | 25 | .27 | .30 | 50 | .60 | 0 | .27 | 50 | 17 |

| Teacher–self | .29 | .29 | 100 | .63 | 0 | .09 | .35 | 50 | .64 | 0 | .46 | .35 | 100 | .47 | 75 | .28 | 83 | 25 |

| Teacher–parent | .04 | .07 | 75 | .64 | 0 | −.08 | .08 | 0 | .64 | 0 | .13 | .08 | 100 | .52 | 0 | .03 | 58 | 0 |

| Observer–self | .14 | .19 | 50 | .43 | 0 | .25 | .20 | 100 | .60 | 25 | .17 | .19 | 75 | .60 | 0 | .19 | 75 | 8 |

| Observer–parent | .06 | .02 | 100 | .54 | 0 | .01 | .13 | 50 | .60 | 0 | .09 | .13 | 75 | .60 | 0 | .05 | 75 | 0 |

| Self–parent | .17 | .13 | 100 | .61 | 0 | .03 | .11 | 25 | .54 | 0 | .28 | .13 | 100 | .52 | 0 | .16 | 75 | 0 |

| Mean by construct | .23 | 88 | 5 | .11 | 35 | 5 | .29 | 90 | 20 | |||||||||

Note: CV = convergent validity; DV = general divergent validity; SMV = shared method variance component of divergent validity; r = correlation in validity diagonal; highest DCDI = highest different construct–different informant correlation; % CV > DCDI = percentage of validity diagonal correlations exceeding different construct–different informant correlations; highest DCSI = highest different construct–same informant correlation; % CV > DCDI = percentage of validity diagonal correlations exceeding different construct-same informant correlations.

The informant pairs with the greatest mean convergent validity across constructs in descending order were as follows: teacher–peer r = .43, teacher–self r = .28, teacher–observer r = .27, peer–self r = .25, peer-observer r = .24. Because highest convergence was achieved among informants in the school environment, these results are consistent with the principle of shared environment.

Divergent Validity

Divergent validity was examined with two principle methods recommended by Campbell and Fiske (1959). Firstly, general divergent validity requires that correlations should be higher for the same vs. different constructs when both are assessed by different informants. In Table 1, values in the validity (same construct–different informant) diagonals were compared with values in the solid different construct–different informant triangles in the same row and column. General divergent validity was greater for AS and exclusion than unsociability (with validity diagonal correlations exceeding different construct–different informant correlations for an average of 88 percent and 90 percent of comparisons for AS and exclusion, respectively vs. 35 percent for unsociability; see mean DV values by construct in Table 2). For AS and exclusion, most informant pairs demonstrated acceptable divergent validity. However, for unsociability, divergent validity was acceptable only for peers–teachers and observers–self.

Secondly, to examine shared method variance, validity diagonal values were compared with those in the different construct–same informant triangles (see triangles with dashed lines in Table 1). Considerable shared method variance was observed for all three constructs, although exclusion appears to suffer from somewhat less shared method variance than AS and unsociability (see mean SMV by construct in Table 2; these are the mean proportions of convergent validity correlations that exceeded different construct–same informant correlations by construct). Likewise, shared method variance was elevated across informants, but peer–teacher, peer–self, teacher–observer, and teacher–self pairs had the least shared method variance (see average SMV values by informant pairs in Table 2). However, traditional MTMM analyses do not explicitly differentiate shared method variance from true correlations among constructs. In contrast, SEM directly models both the degree of partial (rather than zero-order) correlation among constructs and shared method variance separately.

Structural Equation Modeling

The Three-factor Model

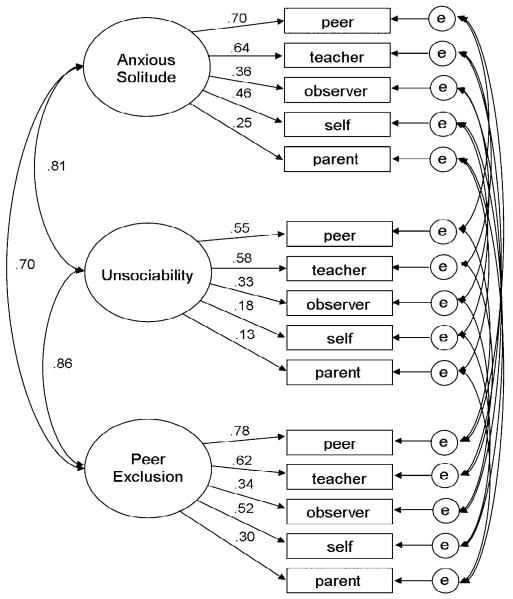

A three-factor CFA was conducted to examine convergent and divergent validity (see Figure 1). The large circles represent latent constructs or factors: AS, unsociability, and peer exclusion. The boxes represent the measured variables for each construct by informant: peers, teachers, observers, self, and parents. The single-headed arrows from the large circles to the boxes represent factor loadings (path coefficients) of the measured variables onto their respective latent constructs. The curved arrows between the large circles represent correlations between the latent constructs. The smaller circles represent error terms or unexplained variance associated with each measured variable (there were too many of these values to display in figures, but they are summarized later in the text and in tabular form). Error terms were allowed to correlate within informant across constructs to represent shared method variance. Each of the three latent constructs was constrained to have a variance of 1.0.

Figure 1.

Three-factor Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Anxious Solitude, Unsociability, and Peer Exclusion as Assessed by Five Informants.

Fit Indices

Several indices were used to evaluate model fit, including the chi-square, normed chi-square (NC), root mean square residual error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR). Acceptable fit was judged according to the criteria recommended by Hu and Bentler (1999). The chi-square is a test of ‘badness of fit,’ with significant values indicating that the model fits the data poorly. However, because the chi-square statistic is sensitive to sample size, significant values are often a product of large sample size rather than poor model fit. The NC statistic corrects for this sensitivity by dividing the chi-square by the model’s degrees of freedom. NC values of 2 or less are considered acceptable (Byrne, 1989). The RMSEA is another ‘badness of fit’ index, but it corrects for model complexity. RMSEA values that are not significantly different from zero (defined as less than .06) are considered to be acceptable. The SRMR is the standardized average of the co-variance residuals, or more specifically, the difference between the observed and predicted correlations. SRMR values of .08 or lower are indicative of acceptable fit.

To compare model fit for the three-factor model vs. the alternate two- and one-factor models, the expected cross-validation index (ECVI) of predictive fit indices was calculated. The ECVI is used to rank order competing models (Kline, 2005), with lower values indicating better model fit. For a summary of ideal values for fit indices, see Table 3.

Table 3. Summary of Confirmatory Factor Analysis Model Fit Indices.

| χ 2 | df | NC | RMSEA | SRMR | ECVI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal standards | NS | N/A | ≤2 | <.06 | ≤.08 | Lower |

| Three-factor model | 87.68† | 72 | 1.22 | .037 | .03 | 1.13 |

| Girls’ model | 97.56* | 72 | 1.36 | .061 | .05 | 2.04 |

| Boys’ model | 69.83NS | 72 | .97 | .000 | .05 | 2.51 |

| Two-factor model | 102.63* | 74 | 1.39 | .049 | .04 | 1.20 |

| One-factor model | 124.04*** | 75 | 1.65 | .064 | .04 | 1.32 |

p < .10

p < .05

p < .001.

df = degrees of freedom; NC = normed chi-square; RMSEA = root mean square residual error of approximation; SRMR = standardized root mean squared residual; ECVI = expected cross-validation index; NS = not significant.

Convergent Validity

Convergent validity was evaluated based on the size and significance of the standardized factor loadings of the measured variables on their respective constructs (latent factors) after controlling for shared method variance and the contributions of other informants to the same latent construct. Every measured informant loaded significantly (ps < .002) onto its respective latent construct, supporting convergent validity (see Figure 1). These SEM results differ from traditional MTMM results, in which not all correlations in the validity diagonals were significant. Additionally, all path coefficients (and mean path coefficients) in the SEM model were compared statistically via a t-test computed by dividing the difference of two factor loadings by their pooled standard error. Mean factor loadings were significantly higher for AS (M λ = .48) and exclusion (M λ = .51) than unsociability (M λ = .35; see Table 4). Also, mean factor loadings were significantly higher for peers (M λ = .68) and teachers (M λ = .61) than observers (M λ = .34) and the self (M λ = .39), and parents (M λ = .23) demonstrated the least convergent validity of all informants.

Table 4. Standardized Factor Loadings (λ) and Significant Differences among Loadings by Construct and Informant for the Three-factor Model (Convergent Validity).

| Anxious solitude |

Unsociability |

Exclusion |

Mean by Informant |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informant | λ | λ | λ | |

| Peer | .70a | .55a | .78a | .68A |

| Teacher | .64a | .58a | .62b | .61A |

| Observer | .36b | .33b | .34d | .34B |

| Self | .46b | .18c | .52c | .39B |

| Parent | .25b | .13c | .30d | .23C |

| Mean by construct | .48A | .35B | .51A |

Note: Factor loadings in the same column with different lower case superscripts are significantly different at p < .05 or better, excluding the last row and column. Factor loadings in the last row and column with different capitalized superscripts are significantly different at p < .05 or better.

Divergent Validity

The three constructs were allowed to correlate with one another to model the degree of general divergent validity. Correlations among the three constructs were high (AS–peer exclusion r = .70, AS–unsociability r = .81, and unsociability–exclusion r = .86). It is considered worthwhile to distinguish between latent constructs that correlate less than .80, thus supporting the distinction between AS and peer exclusion, but calling into question whether or not unsociability can be distinguished from the other two constructs. In order to further examine the empirical support for distinguishing unsociability from the other two constructs, the three-factor model was compared with an alternate two-factor model in which all internally-based sources of solitude were combined, and a one-factor model in which all solitude was combined. Although the two- and one-factor models fit adequately, all fit indices were best for the three-factor model (see Table 3). An alternate version of the three-factor model in which unoccupied behavior was removed from the model was also computed in order to examine whether or not this measure was contributing to high correlations among constructs; however, no improvement in the model resulted. Thus, despite high correlations between unsociability and the other two constructs, the original version of the three-factor model achieved the best combination of fit indices and was therefore chosen as the primary model for interpretation.

Shared method variance was examined by allowing the error terms for each informant to correlate across constructs. All error correlations were statistically compared via the same t-test used to compare factor loadings (computed by dividing the difference of two error correlations by their pooled standard error). There were no significant differences in mean error correlations (Θ) by construct, but differences were apparent by informant (see Table 5). Peers had the least shared method variance (best divergent validity; M Θ = .28) and did not differ significantly from observers (M Θ = .32), but had significantly less shared method variance than parents (M Θ = .39), teachers (M Θ = .39), and the self (M Θ = .37).

Table 5. Standardized Error Covariances (Θ) by Informants (Shared Method Variance) and Pairs of Constructs (General Divergent Validity) for the Three-factor Model.

| Anxious solitude– unsociability |

Unsociability– exclusion |

Exclusion–anxious solitude |

Mean by informant |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informant | Θ | Θ | Θ | |

| Peer | .34b | .12a | .39a | .28A |

| Teacher | .55c | .27b | .34b | .39B |

| Observer | .06a | .55c | .36e | .32AB |

| Self | .39b | .41c | .31c | .37B |

| Parent | .54c | .51c | .12d | .39B |

| Mean by construct |

.38A | .37A | .30A |

Note: Error covariances in the same column with different lower case superscripts are significantly different at p < .05 or better, excluding the last row and column. Error covariances in the last row and column with different capitalized superscripts are significantly different at p < .05 or better.

Comparison of Traditional MTMM Analyses with Three-factor Structural Equation Modeling Model

Convergent Validity

Both SEM and traditional analyses suggest that convergent validity by construct was higher for AS and exclusion than unsociability. Likewise, both analytic methods indicated that convergent validity by informant was greatest for peers and teachers, with other school-based informants showing mid-level validity, and parents (the only non-school based informants) demonstrating the least validity. These results support the principle that shared environment promotes convergence.

Divergent Validity

In regard to general divergent validity by construct, both SEM and traditional analyses indicated greater divergence for AS and exclusion than unsociability. Although SEM analyses indicated high correlations involving unsociability, the three-factor model demonstrated modestly better fit than alternate two- and one-factor models, suggesting that the three constructs can be distinguished from one another but are highly correlated.

SEM indicated that peers demonstrated significantly less shared method variance than teachers, the self, or parents (there were no differences between observers and other informants). Although traditional analyses indicated that peers were among those with less shared method variance (and these results are therefore compatible with those derived from SEM), the traditional method did not directly separate actual co-occurrence of constructs from shared method variance. That is, whereas SEM explicitly models the separate contribution of constructs and informants to variance explained and each effect controls for the other, construct and method (informant) variance are combined in the correlations displayed in a traditional MTMM matrix and are only parsed into construct and method variance indirectly by making comparisons among certain sets of correlations.

Gender Differences

First, single-sex MTMM correlation matrices were computed for descriptive purposes. Next, gender differences were examined by testing the equality of covariance matrices for boys and girls in a multi-sample three-factor CFA (because AMOS cannot perform this test, it was performed in LISREL). As with the combined-sex CFA, latent variables were given variances of 1.0, and factor loadings were allowed to vary. Factor loadings were similar to those of the combined-sex model, but results suggested that the covariance matrices were not equal (χ2 = 3230.38, p < .001, RMSEA = .21), so models were examined separately for boys and girls (detailed results can be obtained from the first author). Both single-sex models had adequate fit, although the boys’ model’s fit was somewhat better (see Table 3).

Similar to the combined-sex model, in the single-sex models, AS and exclusion demonstrated statistically equivalent mean convergent validity whereas unsociability demonstrated less mean convergent validity (in the boys’ model, unsociability demonstrated less convergent validity than exclusion only). Single-sex models were also consistent with the combined-sex model in regard to convergent validity by informant, indicating that peers and teachers demonstrated significantly higher factor loadings than other informants. The least convergent validity was demonstrated by parents in both the combined- and single-sex models; observers demonstrated equally poor convergent validity in both single-sex models; and the self demonstrated equally poor convergent validity in the boys’ model.

In regard to general divergent validity, the combined-sex model revealed a positive correlation between AS and exclusion that was within recommended guidelines (below .80) for separate constructs, but higher-than-recommended positive correlations involving unsociability. In contrast, the boys’ model indicated higher-than-recommended positive correlations among all three constructs, whereas the girls’ model indicated positive correlations that were within recommended guidelines for all three constructs. Consistent with expectations, there was a stronger correlation between AS and exclusion for boys than girls (r = .88 vs. .51, Fisher’s Z = 5.01, p < .001). No expectations were advanced about sex differences in the strength of correlations between unsociability and the other two constructs, but again, correlations were higher for boys than girls (unsociability–AS r = .94 vs. .76, Z = 4.57, p < .001; unsociability–exclusion r = .98 vs. .59, respectively, Z = 9.97, p < .001). Thus, general divergent validity was within recommended guidelines for girls, but appears more problematic for boys.

The shared method variance component of divergent validity was relatively consistent across combined- and single-sex models. Peers demonstrated the least shared method variance across models. Observers demonstrated similarly low shared method variance in both the combined and boys’ models, but not in the girls’ model. Parents were among those informants with the most (worst) shared method variance across all models. Finally, the three constructs demonstrated statistically equivalent mean shared method variance across all models.

Discussion

This investigation contributes to extant literature by providing a systematic empirical evaluation of the validity of the three primary forms of childhood solitude—AS, unsociability, and peer exclusion—and the five major informants of childhood solitude: peers, teachers, observers, the self, and parents. Results indicate greater convergent and divergent validity for AS and peer exclusion than for unsociability. Peers stand out for strong convergent and divergent validity whereas parents stand out for poor validity, but all five informants’ reports made significant contributions.

Anxious Solitude and Exclusion

Results suggest that from the perspective of multiple informants, anxious affect, shyness, verbal inhibition, and high rates of onlooking solitary behavior indicate AS, whereas being ignored and explicitly left out of activities indicate peer exclusion. These two constructs are conceptually distinct: AS locates the impetus for solitude internally (in the child), whereas peer exclusion locates it externally (in the peer environment). However, these constructs’ separateness does not imply that they are mutually exclusive. Indeed, past investigations have demonstrated that some children demonstrate ‘pure’ forms of both constructs whereas others demonstrate the co-occurrence of AS and peer exclusion (Gazelle & Ladd, 2003; Gazelle & Rudolph, 2004). Present results are consistent with past literature in indicating that these constructs are distinct but positively and substantially correlated (Bowker, Bukowski, Zargarpour, & Hoza, 1998; Gazelle & Ladd, 2003). Indeed, the co-occurrence of these constructs is of central importance to the diathesis-stress explanation for poorer behavioral and emotional adjustment in anxious–solitary–excluded children than in their ‘pure’ counterparts (Gazelle & Ladd, 2003; Gazelle & Rudolph, 2004). According to the diathesis-stress perspective, AS children are particularly concerned about how they will be treated by peers (the term ‘diathesis’ indicates that this concern renders the child vulnerable to interpersonal stress), and peer exclusion and other forms of peer mistreatment confirm their interpersonal fears, thus exacerbating social and emotional difficulties.

Unsociability

Results indicate poorer convergent and divergent validity for unsociability than for the other two forms of solitude. Poorer convergent validity is perhaps a reflection of the current lack of knowledge about behavioral and affective manifestations of unsociability. Whereas previous theorists proposed that high rates of directed solitary behavior index unsociability (Coplan et al., 2004), empirical evidence failed to support this proposition among third grade children (observed directed solitary behavior was uncorrelated with self-reported social disinterest). Rather, unoccupied solitary behavior demonstrated a positive relation with both self-reported social disinterest and the latent construct of unsociability. Whereas past theorists have proposed that unsociability stems from ‘object focus’ or being engrossed in objects (e.g., toys, books) (Jennings, 1975), these results suggest that unsociability may not so much stem from object focus as lack of focus on the external (either people or objects). This might imply an internal focus (e.g., with one’s own thoughts or feelings) or a broader motivational deficit (lack of interest in both people and objects). Further work will be needed to test these possibilities and examine whether or not manifestations of unsociability change with development. Specifically, the majority of work distinguishing between AS and unsociability has been conducted with preschool- and kindergarten-age children, which may explain why different behavioral correlates of unsociability were found in the present investigation. An additional possibility is that lack of association between directed solitary play at recess and self-reported social disinterest may be a feature of context. Unsociable children may be more interested in objects available indoors (e.g., toys, books) rather than outdoors (e.g., recess equipment and objects in nature). However, observation of outdoor play at recess is more ecologically valid than indoor observation for third graders, who typically experience free-play periods at school primarily during recess.

Although unsociability is conceptually distinct from other forms of solitude, present results indicate (1) strong correlations between unsociability and other forms of solitude, and (2) only modest improvement in fit when models distinguish unsociability from other forms of solitude, thus raising questions about the empirical basis for unsociability as a separate construct. Conceptually, it is not problematic that unsociability co-occurs with peer exclusion in some children (Coplan et al., 2004). Indeed, past research has indicated that unsociability appears to become increasingly correlated with peer relations difficulties with age (Coplan et al., 1994, 2001; Rubin & Mills, 1988), perhaps because unsociable behavior is perceived as increasingly deviant from age norms (Younger & Daniels, 1992). However, the conceptual definitions of unsociability and AS would appear to be contradictory, as unsociability characterizes children as lacking desire for social interaction whereas AS characterizes children as desiring social interaction. Yet more nuanced thinking about AS and unsociability may resolve this apparent contradiction. It may be that some children vacillate from moment to moment between anxiously desiring social interaction (as manifested in onlooking behavior) to finding some relief and contentment in solitary behavior during which time they do not desire social contact (as manifested in unoccupied solitary behavior). This cycle may come full circle when such children ultimately become lonely in the course of their unsociable solitary behavior and again desire social contact, perhaps prompting a return to onlooking solitary behavior. Consistent with this possibility, evidence from the present investigation suggests some co-occurrence of AS and unsociability (not only were these constructs correlated, but also 9 percent of children endorsed both self-perceptions, 22 percent of children endorsed AS only, and only 3 percent endorsed unsociability only). Further research is needed to understand how some children may vacillate between AS and unsociability over time.

Informants

Across models, peers consistently demonstrated the best convergent and divergent validity. In contrast, parents were consistently among those with the worst convergent and divergent validity. Teachers, observers, and the self tended to demonstrate mid-level convergent and divergent validity. These patterns are consistent with the principle of shared environment (Achenbach et al., 1987). Specifically, there was a pattern of greater convergence among school-based informants. The particularly strong validity of peer reports may be due in part to peers’ presence across school contexts where solitude occurs (recess as well as the classroom), whereas other school-based informants observed primarily in certain school contexts (teachers in the classroom, observers for limited time-periods at recess). Peers’ status as ‘inside observers,’ or participants in rather than observers of the interactions of interest, is also likely to have contributed to the validity of their reports.

The mid-level validity of children’s self-reports of solitude supported the expectation that self-report biases would limit the validity of these reporters (Pronin et al., 2002), who otherwise share many of the same advantages of peers (e.g., access to relevant environments and an ‘inside perspective,’ as well as long-term knowledge of self). Indeed, the greatest weakness of self-reports (a single perspective may often be biased or idiosyncratic) is one of the greatest strengths of peer reports (multiple informants diminish single-rater biases). Ultimately, the use of multiple informants preserves the unique contributions of each informant while avoiding overreliance on informants whose reports evidence lower validity.

Gender Differences

Although comparison of combined-sex vs. sex-differentiated CFAs suggested sex differences, boys’ and girls’ models were similar in most respects. Across models, AS and exclusion demonstrated more convergent validity than unsociability (although unsociability differed only from exclusion in the boys’ model), and peers and teachers demonstrated the best combination of convergent and divergent validity. The major sex difference between models was in informants’ ability to distinguish among constructs (general divergent validity). Specifically, correlations among the three forms of solitude were within recommended limits for girls, but not boys. This result is compatible with past findings indicating greater peer difficulties (including exclusion) among AS boys than girls in early middle childhood (Gazelle & Ladd, 2003). This pattern may occur because peers see AS behaviors as violating male sex norms emphasizing self-assertion and dominance at this age. This rationale would suggest higher actual co-occurrence of these constructs in boys rather than poor divergent validity. Consistent with this possibility, past findings also clearly indicate that the co-occurrence of AS and peer exclusion vs. the occurrence of AS alone confers significantly more behavioral and emotional maladjustment in children of both sexes (Gazelle & Ladd; Gazelle & Rudolph, 2004). If AS and peer exclusion were truly indistinguishable, it should not be possible to identify both ‘pure’ and ‘comorbid’ groups, and ‘comorbid’ groups should not be systematically more maladjusted. The apparent contradiction between the results of the present MTMM CFA and studies that have investigated the adjustment of pure and comorbid groups may be due to a variable- vs. person-oriented approach (CFA vs. subgroup approach, respectively). These approaches are designed to answer different questions. Variable-oriented analyses examine the relation among constructs across data matrices whereas person-oriented analyses examine the co-occurrence of constructs nested within children (Magnusson & Stattin, 2006).

Although gender differences in the relation between AS and peer exclusion were in line with expectations, no gender differences in the relation between unsociability and the other two constructs were expected. Nonetheless, the MTMM CFA indicated that unsociability and the other two constructs were more separable or distinct for girls than boys. It may be that social partners see unsociability as less compatible with stere-otypical feminine characteristics (e.g., expect girls to be highly interested in relationships), and are therefore less likely to make an attribution of unsociability for girls if another explanation is available (they may be more likely to attribute girls’ solitary behavior to sources other than social disinterest). However, this possibility is speculative, and further evidence will be needed to examine whether or not this is a reliable gender difference.

Contributions and Limitations

It is important to acknowledge that present results are applicable to third grade children and might differ somewhat at different ages. In particular, there has been some debate about the validity of peer-reports of solitude before third grade (Younger et al., 1985, 1986), and further MTMM investigations will be needed at younger ages to shed more light on this issue. Furthermore, approximately half of the sample was selected on the basis of elevated AS scores, but children were not similarly oversampled for unsociability (although equal proportions of children with elevated unsociability exist in the screening and selected samples), so this sampling design limits the strength of conclusions regarding unsociability.

Taken together, the present study provides the most systematic and comprehensive empirical examination to date of the comparative strengths of almost all possible informants of the three major forms of childhood solitude. Results more strongly support the construct validity of AS and exclusion than unsociability. This finding suggests that behavioral and affective indicators of unsociability are poorly understood. In particular, a form of solitary behavior previously assumed to indicate unsociability (directed solitary behavior) was unrelated to self-reported social disinterest, whereas self-reported social disinterest correlated positively with unoccupied solitary behavior. Further work is needed to determine whether or not unsociability is best conceptualized as a separate form of solitude or rather as an intermittent state that may occur among some children who experience other forms of solitude.

Present results should serve as a useful guide to researchers when choosing among potential informants of childhood solitude. Although all informants made significant contributions to identifying the three major forms of solitude, some informants would be better choices than others for specific applications. For instance, in a study concerning the relation of children’s solitary behavior to their peer relations, peers and teachers would be better choices than parents. The preferred status of peer reports in the developmental literature appears to be supported by empirical evidence. The validity of observational data was also supported, but it was not quite as robust—particularly in regard to convergent validity. Interestingly, although teacher reports often meet with some skepticism, they were among the methods with the best convergent validity, although their divergent validity was moderate. Overall, results support the value of multiple informants of childhood solitude, but when resources are limited, researchers are urged to employ empirical evidence to make the best-informed decisions.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by grant 1K01MH076237 from NIMH to Heidi Gazelle. This article is based on Tamara Spangler’s Master’s thesis. We extend thanks to Drs. Ric Luecht and Paul Silvia for comments on statistical methods and the children, parents, and teachers who participated in this project.

Footnotes

Modestly better fit indices will be slightly smaller in most cases. However, there is no way to test the significance of differences among indices for contrasting models, because the models are not nested (nested models can be tested via chi-square). Even when models are nested, the chi-square testing differences between them should not be interpreted as a test statistic; rather, predictive fit indices such as the ECVI should be compared, with the lowest value indicating the best fit (Kline, 2005).

Because children were oversampled for elevated peer-report AS scores, but not unsociability (or any other behavioral characteristic), we checked whether or not the number of children displaying dual AS and unsociability was overrepresented. Children scoring at or above 1 SD in one or both composites were identified. Because there is reason to be skeptical of the accuracy of social partners’ perceptions of unsociability (see pp. 2, 10, 15), this analysis was performed via both peer and self report. In the screening sample, there was a substantial proportion of dual-status children regardless of whether or not peer or self-informants were employed. Interestingly, whereas peers reported approximately an equal number of children who were dual-status and unsociable-only (both 8 percent; χ2 = .04, NS), self reports indicated that dual status was more common than pure unsociability (9 percent vs. 3 percent; χ2 = 20.25, p < .001). Thus, evidence from multiple informants supports the co-occurrence of AS and unsociability in many (but not all) unsociable children. In regard to overrepresentation of dual-status AS-unsociable children in the selected sample, this appears to have occurred only in regard to peer but not self report. Specifically, all peer-identified AS children were oversampled regardless of what other behaviors they displayed. In contrast, peer-identified unsociable-only children were not oversampled. They represented 8 percent of the screening sample and 7 percent of the selected sample (χ2 = .24, NS). However, when children were identified via self report, neither dual (9 percent vs. 11 percent; χ2 = 1.08, NS) nor unsociable-only children (3 percent vs. 2 percent; χ2 = .26, NS) were overrepresented. These patterns would suggest that (1) the overrepresentation of dual-status children appears to be specific to peer reports, suggesting that the presence of four other informants in the model should have mitigated this tendency; and (2) that the co-occurrence of AS and unsociability is a phenomenon reported by multiple informants and appears in the screening as well as the selected sample.

References

- Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT. Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:213–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albano AM, Krain A. Anxiety and anxiety disorders in girls. In: Bell DJ, Foster SL, Mash EJ, editors. Handbook of behavioral and emotional problems in girls. Kluwer; New York: 2005. pp. 79–116. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos 6.0 User’s Guide. Amos Development Corporation; Spring House, PA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Asendorpf JB. Beyond social withdrawal: Shyness, unsociability, and peer avoidance. Human Development. 1990;33:250–259. [Google Scholar]

- Bowker A, Bukowski W, Zargarpour S, Hoza B. A structural and functional analysis of a two-dimensional model of social isolation. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1998;44:447–463. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM. Age differences in children’s memory of information about aggressive, socially withdrawn, and prosociable boys and girls. Child Development. 1990;61:13–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess KB, Wojslawowicz JC, Rubin KH, Rose-Krasnor L, Booth-LaForce C. Social information processing and coping strategies of shy/withdrawn and aggressive children: Does friendship matter? Child Development. 2006;77:371–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00876.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. A primer of LISREL: Basic applications and programming for confirmatory factor analytic models. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DT, Fiske DW. Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin. 1959;56:81–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Elder GH, Bem DJ. Moving away from the world: Life-course patterns of shy children. Developmental Psychology. 1988;24:824–831. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA, Kupersmidt JB. Peer group behavior and social status. In: Asher SR, Coie JD, editors. Peer rejection in childhood. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1990. pp. 17–59. [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ. Assessing nonsocial play in early childhood: Conceptual and methodological approaches. In: Schafer C, editor. Play diagnosis and assessment. 2nd ed. Wiley; New York: 2000. pp. 563–598. [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Gavinski-Molina MH, Lagace-Seguin DG, Wichmann C. When girls versus boys play alone: Nonsocial play and adjustment in kindergarten. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:464–474. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.4.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Prakash K, O’Neil K, Armer M. Do you ‘want’ to play? Distinguishing between conflicted shyness and social disinterest in early childhood. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:244–258. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Rubin KH. Exploring and assessing nonsocial play in the preschool: The development and validation of the preschool play behavior scale. Social Development. 1998;7:72–91. [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Rubin KH, Fox NA, Calkins SD, Stewart SL. Being alone, playing alone, and acting alone: Distinguishing among reticence and passive and active solitude in young children. Child Development. 1994;65:129–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crozier WR, Burnham M. Age-related differences in children’s understanding of shyness. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 1990;8:179–185. [Google Scholar]

- Foster SL, Bell-Dolan D, Berler ES. Methodological issues in the use of sociometrics for selecting children for social skills research and training. Advances in Behavioral Assessment of Children & Families. 1986;2:227–248. [Google Scholar]

- Gazelle H. Behavioral profiles of anxious solitary children and heterogeneity in peer relations. Developmental Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0013303. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazelle H, Ladd GW. Anxious solitude and peer exclusion: A diathesis-stress model of internalizing trajectories in childhood. Child Development. 2003;74:257–278. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazelle H, Putallaz M, Li Y, Grimes CL, Kupersmidt JB, Coie JD. Anxious solitude across contexts: Girls’ interactions with familiar and unfamiliar peers. Child Development. 2005;76:227–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazelle H, Rudolph KD. Moving toward and away from the world: Social approach and avoidance trajectories in anxious solitary youth. Child Development. 2004;75:829–849. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrist AW, Zaia AF, Bates JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS. Subtypes of social withdrawal in early childhood: Sociometric status and social-cognitive differences across four years. Child Development. 1997;68:278–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hymel S, Rubin KH, Rowden L, LeMare L. Children’s peer relationships: Longitudinal prediction of internalizing and externalizing problems from middle to late childhood. Child Development. 1990;61:2004–2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings KD. People versus object orientation, social behavior, and intellectual abilities in preschool children. Developmental Psychology. 1975;11:511–519. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Lambert WW, Bem DJ. Life course sequelae of childhood shyness in Sweden: Comparison with the United States. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:1100–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd Ed. Guilford; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Profilet SM. The child behavior scale: A teacher-report measure of young children’s aggressive, withdrawn, and prosocial behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:1008–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Lance CE, Noble CL, Scullen SE. A critique of the correlated trait-correlated method and correlated uniqueness models for multitrait-multimethod data. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:228–244. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledingham JE, Younger A, Schwartzman AE, Bergeron G. Agreement among teacher, peer, and self-ratings of children’s aggression, withdrawal, and likability. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1982;10:363–372. doi: 10.1007/BF00912327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson D, Stattin H. The person in context: A holistic-interactionistic approach. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 6th ed. Wiley; New York: 2006. pp. 400–464. [Google Scholar]

- Morison P, Masten AS. Peer reputation in middle childhood as a predictor of adaptation in adolescence: A seven-year follow-up. Child Development. 1991;62:991–1007. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronin E, Lin DY, Ross L. The bias blind spot: Perceptions of bias in self versus others. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28:369–381. [Google Scholar]

- Putallaz M, Wasserman A. Children’s naturalistic entry behavior and sociometric status: A developmental perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25:297–305. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH. The play observation scale (POS) University of Maryland; 2001. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Chen X, McDougall P, Bowker A, McKinnon J. The Waterloo longitudinal project: Predicting internalizing and externalizing problems in adolescence. Development & Psychopathology. 1995;7:751–764. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Mills RS. The many faces of social isolation in childhood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:916–924. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Wojslawowicz JC, Rose-Krasnor L, Booth-LaForce C, Burgess KB. The best friendships of shy/withdrawn children: Prevalence, stability, and relationship quality. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:143–157. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-9017-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serbin LA, Cooperman JM, Peters PL, Lehoux PM, Stack DM, Schwartzman AE. Intergenerational transfer of psychosocial risk in women with childhood histories of aggression, withdrawal, or aggression and withdrawal. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1246–1262. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH. Tests for comparing elements of a correlation matrix. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;87:245–251. [Google Scholar]

- Terry R, Coie JD. A comparison of methods for defining sociometric status among children. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:867–880. [Google Scholar]

- Younger AJ, Daniels TM. Children’s reasons for nominating their peers as withdrawn: Passive withdrawal versus active isolation. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:955–960. [Google Scholar]