Abstract

This consensus statement on chronic hepatitis (CH) in dogs is based on the expert opinion of 7 specialists with extensive experience in diagnosing, treating, and conducting clinical research in hepatology in dogs. It was generated from expert opinion and information gathered from searching of PubMed for manuscripts on CH, the Veterinary Information Network for abstracts and conference proceeding from annual meetings of the American College of Veterinary Medicine and the European College of Veterinary Medicine, and selected manuscripts from the human literature on CH. The panel recognizes that the diagnosis and treatment of CH in the dog is a complex process that requires integration of clinical presentation with clinical pathology, diagnostic imaging, and hepatic biopsy. Essential to this process is an index of suspicion for CH, knowledge of how to best collect tissue samples, access to a pathologist with experience in assessing hepatic histopathology, knowledge of reasonable medical interventions, and a strategy for monitoring treatment response and complications.

Keywords: ascites, bile acids, bilirubin, biopsy, coagulation, copper, hepatic, inflammation, liver, portosystemic shunting

Abbreviations

- AAT

alpha‐1 antitrypsin

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- APSS

acquired portosystemic shunts

- aPTT

activated partial thromboplastin time

- BT

Bedlington Terrier

- CH

chronic hepatitis

- CT

computed tomography

- Cu

copper

- CuCH

copper associated chronic hepatitis

- DDAVP

desmopressin

- D‐Pen

D‐penicillamine

- FFP

fresh frozen plasma

- GGT

gamma‐glutamyl transferase

- GSH

glutathione

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- HE

hepatic encephalopathy

- LDH

lobular dissecting hepatitis

- LR

Labrador Retriever

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NRC

National Research Council

- PH

portal hypertension

- PT

prothrombin time

- PVP

portal vein pressure

- PVT

portal vein thrombosis

- SAMe

s‐adenosylmethionine

- TEG

thromboelastography

- TSBA

total serum bile acid

1. DEFINITION OF CHRONIC HEPATITIS

The panel accepts the World Small Animal Veterinary Association definition of chronic hepatitis (CH) as the most complete and accurate currently available1, 2 (Figure 1, Supporting Information S1, Table 1). The key histologic features include the presence of lymphocytic, plasmacytic, or granulomatous inflammation (portal, multifocal, zonal, or panlobular) or some combination of these along with hepatocyte cell death and variable severity of fibrosis and regeneration. Inflammation most commonly originates (or usually is more severe) in portal regions, often spilling over into the hepatic lobule (interface hepatitis). Cirrhosis reflects end‐stage CH when substantial architectural distortion, fibrosis, and sinusoidal portal hypertension (PH) are present. A variant of CH called lobular dissecting hepatitis (LDH) is characterized by lobular inflammation accompanied by disruption of hepatic cords by fine fibrous septa, hepatocyte necrosis, and a marked ductular reaction (Figure 1, Supporting Information S1).

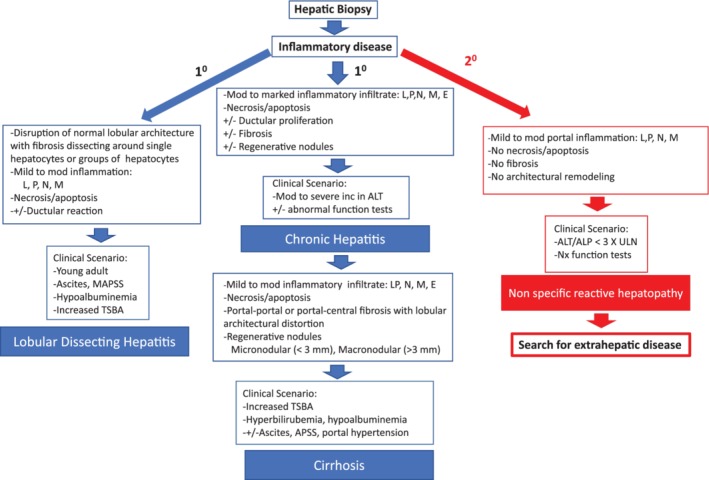

Figure 1.

Primary and secondary chronic inflammatory hepatopathies in dogs. Inflammatory changes on a hepatic biopsy can be due to a primary or secondary hepatopathies. The primary hepatopathies represent a disease process centered on the liver and include chronic hepatitis which can progress to cirrhosis and lobular dissecting hepatitis. Primary hepatopathies are typically accompanied by evidence of hepatocyte necrosis/apoptosis as well as varying degrees of ductular proliferation and fibrosis. Secondary hepatopathies however occur due to a primary disease process elsewhere in the body, often involving the splanchnic circulation, that damage the liver. In this case inflammatory changes are limited to the portal areas and are not accompanied by fibrosis or hepatocyte necrosis/apoptosis. In this case the liver lesions do not represent the primary problem and one should search for the presence of an extrahepatic disorder. ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; APSS, acquired portosystemic shunts; E, eosinophilic; L, lymphocytic; M, granulomatous; N, neutrophilic; P, plasmacytic; TSBS, total serum bile acids

Table 1.

Key points: Definition

|

Because the liver is the recipient of the splanchnic venous outflow, it is exposed to inflammatory cytokines and endotoxin circulated from alimentary viscera. This may culminate in hepatic injury associated with modest inflammatory infiltrates in portal, lobular, or centrilobular regions without obvious hepatocyte death.3, 4, 5 This condition is best termed nonspecific reactive hepatopathy to systemic disease and is not consistent with CH as referred to in this document (Figure 1).

2. ETIOLOGY

Although there is evidence for infectious, metabolic, toxic, and immune causes of CH, most cases of CH in the dog are classified as idiopathic (Table 2).

Table 2.

Factors implicated in the etiology of chronic hepatitis (CH) in dogs and the consensus panel's opinion on the relative strength of evidence (strong, moderate, or weak) based on both the scientific literature and clinical experience

| Etiology | Evidence | References |

|---|---|---|

| Immune | Moderate‐strong | (see Table 5) |

| Toxic | ||

| Copper | Strong | Many (6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46) |

| Metabolic | ||

| Protoporphyria | Moderate (but rare) | Kroeze (47) |

| alpha‐1‐anti‐trypsin | Weak | Sevelius (48) |

| Infectious | ||

| Leptospirosis | Moderate | Bishop (49) Adamus (50) McKallum (51) |

| Leishmaniasis | Moderate‐strong | Gonzalez (52) Rallis (53) |

| Rickettsial | Weak | Egenvall (54) Mylonakis (55) Frank (56) Harrus (57) Nair (58) Hildebrandt (59) De Castro (60) |

| Mycobacteria | Moderate | Campora (61) Martinho (62) Naughton (63) Turinelli (64) Rocha (65) |

| Histoplasmosis | Moderate | Chapman (66) Bromel (67) |

| Protozoal (Neospora, Sarcocystis, Toxoplasma) | Moderate | Allison (68) Dubey (69) Fry (70) Hoon‐Hanks (71) Magana (72) Dubey (73) |

| Bartonella | Weak | Gillepsie (74) Saunders (75) |

| Viral | Negligible | Bexfield (76) Boomkins (77) Rakich (78) Van der Laan (79) |

Strong evidence = numerous peer‐reviewed scientific papers or case series.

Moderate evidence = a single peer‐reviewed scientific paper or peer reviewed abstract.

Weak evidence = single case report, observational impressions, or extrapolation from human literature.

2.1. Infectious

To date there is no strong evidence of a viral etiology.76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81 Sporadic cases of CH have been associated with other infectious agents. Leptospirosis causes acute hepatitis and there is some evidence it can induce a chronic pyogranulomatous response.49, 50, 51 Bacillus piliformis, Helicobacter canis, and Bartonella spp have been identified in dogs with CH, but the evidence that these bacteria are the cause is not compelling.1, 74, 75, 82 Ehrlichia canis has been associated with CH, and nonsuppurative hepatitis has been reported with babesiosis.54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 83 Experimentally, anaplasmosis causes subacute hepatitis.58, 59, 60, 75, 84 Leishmaniasis is associated with CH, usually causing granulomatous inflammation.52, 53 Multiple other systemic diseases can have hepatic involvement with the potential to cause CH (Neospora, toxoplasmosis, Sarcocystis, histoplasmosis, Mycobacterium, shistosomiasis, visceral larva migrans), but lesions typically are acute and necrotizing and part of a multisystemic disorder.61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 85, 86, 87, 88

2.2. Drugs and toxins

Several drugs and toxins have been implicated in causing liver injury.89 Most often they cause acute injury, but in some instances CH or cirrhosis are potential sequele. Strong evidence indicates that treatment with phenobarbital, primidone, phenytoin, and lomustine can result in CH.90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96 In the case of phenobarbital, toxicity may be direct or related to altered metabolism of other xenobiotics. Several other drugs or toxins including carprofen, oxidbendazole, amiodarone, aflatoxin, and cycasin may lead to CH although they more commonly cause acute hepatic injury.89, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106 In humans, it is estimated that herbal and dietary supplements are responsible for up to 18% of drug‐induced liver injury (refer to https://livertox.nih.gov/).107, 108, 109, 110, 111 There are several anecdotal but poorly documented reports of liver injury in dogs given herbals or nutritional supplements. Clinicians should be vigilant in obtaining a complete drug history, including nontraditional therapies. Knowledge of commonly implicated agents and a high index of suspicion are essential for diagnosis.

The most common toxic injury causing CH in dogs is a consequence of hepatic copper (Cu) excess.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 Copper‐associated CH (CuCH) may develop in any breed, including mixed breeds, but the Bedlington Terrier (BT), Dalmatian, Labrador Retriever (LR), Doberman Pinscher, and West Highland White Terrier are predisposed.

Abnormal hepatic Cu accumulation results from altered hepatic Cu excretion in bile, excessive dietary Cu intake or both. When Cu exceeds the hepatocyte transport and Cu‐binding capacity, free Cu causes oxidative stress leading to hepatocellular degeneration and cell death with acute or chronic hepatic inflammation or both.112, 113

Altered Cu excretion primarily is associated with genetic mutations in proteins involved with hepatic Cu transport. In BT, autosomal recessive deletions in exon 2 of the ATP7B associated protein COMMD1 leads to CuCH.114, 115, 116 Copper concentrations can reach over 10 000 μg/g dry weight (dw) liver in this breed (normal hepatic Cu ranges from 120 to 400 μg/g dw).18, 19, 24, 26, 35, 37 Genetic screening for COMMD1 deletion, along with selective breeding in BT, has almost eliminated this disease. Recently, a candidate gene ABCA12 has been implicated independent of the COMMD1 deletion.117 Cu‐mediated liver injury in LR may be influenced by mutations in ATP7B gene, which predispose to Cu accumulation, and mutations in ATP7A gene, the intestinal Cu transporter, which protects against Cu accumulation.13 Although genetic testing for these mutations is commercially available, the predictive and diagnostic utility of such testing currently is unknown.

Chronic cholestasis can cause hepatic Cu accumulation. Dogs, unlike humans and cats, are more resistant to Cu accumulation from cholestasis unless exposed to a high dietary Cu load.118, 119

The increasing frequency of CH cases beginning in the late 1990s correlates with the change in the premixes used to supplement Cu in commercial dog foods, which resulted in higher amounts of bioavailable Cu in diets.8, 21, 36, 46, 120, 121 The panel believes that the National Research Council (NRC) and Association of American Feed Control Officials dietary guidelines, along with a change to more bioavailable Cu chelate premixes in commercial dog food, are linked with an increased prevalence of hepatic Cu accumulation in dogs (Table 3).122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130 The Cu concentrations in dog foods often exceed NRC recommendations by >2‐4.8, 120, 128

Table 3.

Dietary copper minimum allowances and copper content of dog foods

| NRCa minimum | AAFCOb minimum | Average dog food | Hepatic dietsc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copper concentration (mg/kg DM/d) | 6d | 7.3e | ~15‐25 | ~4.9 |

Abbreviations: AAFCO, Association of American Food Control Officials; DM, dry matter; NRC, National Research Council.

The NRC recommendations were extrapolated for adult dogs based on observations of puppies fed diets containing 0.11‐0.19 mg/100 kcal metabolizable energy/day that resulted in reduced serum ceruloplasmin concentrations. Serum ceruloplasmin concentrations however do not reflect copper (Cu) bioavailability and this assumption may be not valid for dietary Cu adequacy and dietary recommendations.35, 122, 123, 124, 125

The AAFCO recommendations for adult maintenance require a minimum of 7.3 mg/kg/DM/d with no maximum limit, regardless of the Cu source.1 This recommended amount of Cu is typically added as a premix but fails to also include the Cu present in the base diet. Changes in premix formulations containing Cu oxide with a bioavailability of ~5% to that of Cu chelates (acetate, sulfate, and carbonate) with ~60%‐100% bioavailability significantly increases the amount of Cu absorbed.126, 127 Consequently, there is a large variation in the Cu concentrations in dog foods and many commercial foods have Cu concentrations that far exceed the NRC recommendations by 2‐4 times or even more.8, 120, 128

Hepatic diets specifically Royal Canin Hepatic, Hills L/d and Purina HP Hepatic (Europe only) contain Cu concentrations below AAFCO and NRC requirements. These diets approximate the dietary Cu concentration of approximately 5 mg/kg DM that is the concentration that maintained affected Bedlington Terrier in a neutral Cu balance.

Equates to ~0.15 mg/100 kcal/d.

Equates to ~0.21 mg/100 kcal/d.

The diagnosis of CuCH encompasses several specific findings listed in Table 4. It is unknown what concentration of hepatic Cu is required to trigger CH in the dog. Historical studies have suggested that hepatic damage evidenced by increased serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity, histopathologic morphologic changes or both begins when hepatic Cu concentrations exceed 1000 μg/g dw and almost invariably occurs when levels are >1500 μg/g dw.129 However, considerable phenotypic variability exists with some dogs having “toxic” Cu concentrations (ie, >1000 μg/g dw) and no evidence of hepatic damage, whereas others with concentrations <1000 μg/g dw have substantial hepatic damage.21, 32, 34, 35 The individual threshold for injury likely is influenced by environmental, physiologic, and genetic factors.131, 132, 133, 134

Table 4.

Key points: Copper Associated Hepatitis (CuCH)

| Diagnostic criteria of CuCH |

|

| Challenges in diagnosis of CuCH |

|

Some dogs can have CuCH with lower hepatic copper concentrations.

Copper concentration at which CuCH exists is difficult to empirically state, and other factors such as pattern of copper distribution on biopsy and associated histopathologic damage, copper levels in diet, and clinical picture must be considered.

Table 4 lists the challenges associated with diagnosing CuCH. Determining whether hepatic Cu is the primary driving force for hepatic inflammation may require chelation and monitoring of surrogate indicators of hepatocyte recovery (normalization of serum enzyme activities, repeat liver Cu quantification, or both). Failed resolution of injury after appropriate chelation indicates another pathogenic mechanism. It is speculated that Cu injury can induce neo‐epitope expression, inciting a secondary self‐perpetuating immune response.

Rarely individuals with high concentrations of hepatic Cu can undergo an acute necroinflammatory crisis releasing Cu and causing a Coombs' negative hemolytic anemia.18, 37, 40 Additionally, an acquired Fanconi‐like syndrome characterized by euglycemic glucosuria associated with renal Cu accumulation also can occur in some cases.135, 136, 137, 138

2.3. Metabolic conditions

Alpha‐1 antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency, caused by abnormal hepatic processing of AAT, results in hepatocyte retention of abnormally folded proteins causing CH.139 Abnormal hepatic AAT accumulation is reported in American and English Cocker Spaniels with CH in the absence of circulating AAT deficiency.48 Whether accumulation of hepatic AAT causes liver disease or merely reflects liver injury needs further investigation. A rare metabolic disorder of porphyrin metabolism, erythropoietic protoporphyria, results in abnormal accumulation of porphyrins within hepatocytes and was reported as a cause of CH in a colony of German Shepherds.47

2.4. Immune‐mediated CH

In humans, the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis relies on complex algorithms that make use of serum markers (enzymology, IgG, and autoantibodies including antinuclear antibodies, anti‐mitochondrial antibodies, and anti‐liver and kidney microsomal antibodies), and demonstrated absence of viral markers, excessive alcohol intake, or toxic drug or supplement administration, along with typical hepatic histology and response to immunosuppressive treatment.140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145 Immune‐mediated hepatitis in humans is thought to occur in genetically predisposed individuals when exposure to certain triggers, such as a pathogen, drug, vaccination, toxin, or change in intestinal microbiome provokes a T‐cell mediated immune response targeting liver‐specific epitopes. The inciting trigger may not be apparent at the time of diagnosis.

Specific criteria for the diagnosis of immune‐mediated hepatitis in dogs have not been developed. An immune basis in some dogs with idiopathic CH is suggested by several criteria (Table 5) which include the presence of lymphocytic infiltrates in the liver, abnormal expression of major histocompatibility complex class II proteins, positive serum autoantibodies, familial history of liver disease, association with other immune‐mediated disorders, female predisposition, and favorable response to immunosuppression.1, 7, 9, 14, 15, 20, 32, 34, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 165, 167, 168 A presumptive clinical diagnosis of immune‐mediated CH in the dog requires elimination of other etiologies and a favorable response to immunosuppressive treatment. Currently, the lack of commercially available tests to detect liver‐specific antibody‐antigen interactions or cell immunosensitization in dogs with CH limits the definitive determination of an immune‐mediated etiology.

Table 5.

Evidence for immune‐mediated chronic hepatitis in the dog

| Finding | Reference | Breed(s) |

|---|---|---|

| A lymphocytic infiltrate of the target organ | Defines CH (1) | |

| Boisclair et al (2001)146 | ||

| Sakai et al (2006)147 | ||

| Association with a MHC class II haplotype | Bexfield et al (2012)148 | ESS |

| Speeti et al (2003)149 | DP | |

| Dyggve et al (2011)150 | DP | |

| Positive autoantibodies | Weiss et al (1995)151 | V |

| Andersson and Sevelius (1992)152 | V | |

| Dyggve et al (2017)153 | DP | |

| Dyggve et al (2017)154 | DP | |

| Positive family history of disease | Speeti et al (1998)155 | DP |

| Johnson et al (1982)20 | DP | |

| Dyggve et al (2011)150 | DP | |

| Hoffman et al (2006, 2008)9, 14 | LR | |

| Fieten et al (2016)13 | LR | |

| Thornburg et al (1986, 1996)32, 34 | WW | |

| Female predisposition | Andersson and Sevelius (1995)156 | V |

| Fuentealba et al (1997)157 | V | |

| Johnson et al (1982)20 | DP | |

| Crawford et al (1985)7 | DP | |

| Bexfield et al (2011, 2012)158, 159 | V, ESS | |

| Hirose et al (2014)160 | V ESS | |

| Hoffman et al (2006)15 | LR | |

| Smedley et al (2009)30 | LR | |

| Mandigers et al (2004)45 | DP | |

| Dyggve et al (2011)150 | DP | |

| van den Ingh et al (1988)161 | DP | |

| A favorable response to immunosuppression | Strombeck et al (1988)162 | V |

| Favier et al (2013)163 | V | |

| Sakai et al (2006)147 | ECS | |

| Bayton et al (2017)164 | ESS | |

| Kanemoto et al (2013)165 | ACS | |

| Ullah et al (2017)166 | V | |

| Poitout et al (1997)167 | V | |

| Association with another autoimmune disease | Shih et al (2007)168 | LR |

Abbreviation: ACS, American Cocker Spaniel; DP, Doberman Pinscher; ESS, English Springer Spaniel; LR, Labrador Retriever; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; V, various breeds; WW, West Highland White Terrier.

Key points related to etiology are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Key points: Etiology

|

3. SIGNALMENT AND CLINICAL SIGNS

3.1. Signalment

Details and evidence for breed, sex, and age predispositions are summarized in Supporting Information Table S1. There is strong evidence in ≥2 studies for an increased prevalence of CH in BT,24, 35 Doberman Pinschers,7, 20, 43, 44, 45, 150, 153, 154, 155, 156, 158, 162, 169, 170, 171, 172, 173 LR,8, 10, 14, 21, 27, 138, 158, 162, 163, 168, 169, 172 Dalmatians,39, 40, 41, 157, 158, 169, 174 American and English Cocker Spaniels,27, 48, 156, 157, 162, 163, 165, 169, 175 English Springer Spaniels,158, 159, 170, 175, 176 and West Highland White Terriers31, 32, 34, 156, 157, 169 in several countries. In addition, in Sweden the Scottish Terrier, and in the United Kingdom the Cairn Terrier, Great Dane, Samoyed, Yorkshire Terrier, and Jack Russell Terrier are predisposed.156, 158 There is some suspicion for a breed predisposition in Standard Poodles and American Cocker Spaniels, which appear to be overrepresented in reports on LDH.165, 177, 178, 179, 180, 181

The overall mean age when clinical signs are reported is 7.2 years (11 studies, n = 983 dogs). Disease duration before diagnosis is unclear.27, 147, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 169, 172, 175 Reported age ranges in specific breeds are shown in Supporting Information Table S1. Dalmatians, Doberman Pinschers, and English Springer Spaniels present significantly younger than LR, English Cocker Spaniels, and Cairn Terriers with CH.158 American Cocker Spaniels are significantly younger than English Cocker Spaniels with CH.158 The age of presentation for CuCH and idiopathic CH do not appear to be different. Dogs with LDH present younger than do dogs with CH, with an average age of 2 years (3 months to 7 years, 4 studies with n = 41 dogs).27, 177, 178, 179, 180

Reported sex ratios in individual breeds are shown in Supporting Information Table S1. Female predisposition occurs in LR, Dobermans, Dalmatians, and English Springer Spaniels.6, 7, 15, 20, 39, 158, 159, 170 Male predisposition occurs in American and English Cocker Spaniels.156, 165, 182

3.2. Clinical signs

Clinical signs reported for dogs with CH are summarized in Table 7. Clinical signs typically are nonspecific, such as loss of appetite and lethargy.15, 20, 27, 39, 157, 159, 163, 165, 175, 179, 183, 184, 185, 186 Less common but more specific signs of jaundice and ascites occur in approximately 33% of dogs and hepatic encephalopathy (HE) and bleeding tendencies occur in 6%‐7%. Dogs with late stage CH or cirrhosis are more likely to have ascites and gastrointestinal bleeding.156, 161, 180, 183, 185, 186

Table 7.

Clinical signs in dogs with chronic hepatitis

| Clinical sign | Number of dogsa , b | Percentage of dogs |

|---|---|---|

| Decreased appetite | 180 | 61 |

| Lethargy/depression | 165 | 56 |

| Icterus | 100 | 34 |

| Ascites | 95 | 32 |

| PU/PD | 91 | 30 |

| Vomiting | 71 | 24 |

| Diarrhea | 58 | 20 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 21 | 7.1 |

| Melena | 18 | 6.1 |

| Abdominal pain | 9 | 3.1 |

| Gingival bleeding | 2 | 0.6 |

| Hematochezia | 1 | 0.3 |

| Hemoperitoneum | 1 | 0.3 |

A high incidence of ascites, icterus, and abdominal pain occurs in English Springer Spaniels.159 American Cocker Spaniels also have a high incidence of ascites and acquired portosystemic shunts (APSS) in the absence of hyperbilirubinemia at the time of presentation.165, 180 Over 80% of dogs with LDH present with ascites.27, 165, 177, 179, 180 Cases of granulomatous CH more commonly have fever and abdominal pain.25, 66, 187

Chronic hepatitis seemingly has a long subclinical phase consistent with the observation that up to 20% of dogs with CH have increased serum liver enzyme activities in the absence of clinical illness.6, 7, 12, 15, 27, 32, 157, 168, 175

Key points associated with signalment and clinical signs are summarized in Table 8.

Table 8.

Key points: Signalment and Clinical Signs

|

4. CLINCAL PATHOLOGY

4.1. Serum enzymology

Details on serum liver enzyme activities from 27 retrospective studies of 848 dogs show increased serum ALT activity as the earliest indicator of CH (Table 9).7, 12, 15, 20, 25, 32, 39, 156, 157, 159, 163, 168, 170, 175, 176, 177, 178, 179, 180, 183, 184, 186, 188, 189, 190, 191, 192, 193, 194 Serum ALT activity thus is the best screening test for CH. However, histopathologic evidence of CH can exist in the absence of increased serum liver enzyme activity.192, 193, 195, 196 Increased serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity occurs later in CH. If both ALT and ALP activities are increased, the magnitude of ALT increase often exceeds that of ALP.15, 163, 165, 168As CH progresses and hepatic parenchyma decreases, ALP and gamma‐glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) activities increase compared to ALT (Table 6). Through the course of disease, considerable variation in serum ALT activity can occur suggesting that the extent of necroinflammation fluctuates over time.155 In late stage cirrhosis, transaminases may decrease with parenchymal loss (Table 10).185, 186, 189, 191, 197 Although serum ALT activity has no prognostic application, it has some association with the severity of histologic injury. Less information is available regarding serum aspartate aminotransferase and GGT activities in CH, but they tend to mirror serum ALT and ALP activities, respectively, although both are less sensitive. Evidence suggests that serum concentrations of some microRNAs, particularly miR‐122, are increased with minimal liver injury in the dog in the absence of increases in ALT activity, and thus may have superior sensitivity over standard serum liver enzymology in detecting early CH.192, 193, 194, 195, 196

Table 9.

Common biochemical changes in dogs with chronic hepatitis

| Parameter | Percent increased | Number of studies (# dogs)a |

|---|---|---|

| Inc ALT | 85 ± 16 | 10 (250) |

| Inc ALP | 84 ± 19 | 10 (250) |

| Inc AST | 78 ± 10 | 3 (56) |

| Inc GGT | 61 ± 12 | 5 (121) |

| Inc TSBA | 75 ± 14 | 9 (109) |

| Dec BUN | 40 ± 29 | 5 (65) |

| Dec albumin | 49 ± 19 | 15 (323) |

| Dec cholesterol | 40 ± 12 | 4 (118) |

Table 10.

Comparison of serum ALT and ALP increases in dogs with chronic hepatitis and/or cirrhosis

4.2. Function tests

Hyperbilirubinemia is reported in approximately 50% of dogs with CH and is a negative prognostic indicator (Table 9).175 Because of the liver's large synthetic reserve for albumin synthesis, hypoalbuminemia is a late marker of hepatic synthetic failure. Hypoalbuminemia occurs in most dogs with LDH.177, 178, 179, 180 Decreased concentrations of blood urea nitrogen and cholesterol develop in approximately 40% of dogs with CH, occurring most commonly in those with cirrhosis.165 Hypoglycemia is rare in CH and more often is associated with acute liver failure.

Total serum bile acid (TSBA) concentrations are the most sensitive hepatic function test for CH.197, 198, 199 However, their sensitivity, particularly for early stage disease, is inadequate, which makes them poor screening tests for CH and thus should not be used as the basis for deciding to pursue hepatic biopsy.189, 192, 200 However, TSBA concentrations are uniformly increased when portosystemic shunting is present, thus their sensitivity for detecting cirrhosis and the presence of APSS is high.189 Dogs with cholestasis (ie, hyperbilirubinemia) associated with hepatic disease will always have increased TSBA.

Hyperammonemia has similar sensitivity to detecting CH or cirrhosis and APSS as do TSBA, and it is somewhat more specific because it is not affected by cholestasis.200 However, it is much more technically difficult to accurately measure blood ammonia concentrations.197, 201, 202, 203, 204 Although hyperammonemia infers the presence of HE, HE can develop in the absence of high blood ammonia concentrations.204, 205 Ammonium biurate crystalluria in dogs with CH provides evidence of episodic hyperammonemia.

4.3. Hematology and coagulation testing

Hematology and coagulation testing are discussed in Biopsy Acquisition and Interpretation sections.

4.4. Urinalysis

Isosthenuria is seen in dogs with polyuria and polydipsia. A transient acquired Fanconi‐like syndrome characterized by euglycemic glucosuria may develop in dogs with CuCH and in other toxin‐induced liver injuries when concurrent renal tubular injury occurs.34, 39, 49, 50, 51, 135, 136, 137, 138, 159, 168 The glucosuria in dogs with CuCH resolves with recovery from acute injury.

Key points associated with clinical pathology are summarized in Table 11.

Table 11.

Key points: Clinical Pathology

|

|

5. IMAGING

Abdominal radiographs estimate overall liver size, shape, and opacity, but are not sensitive to subtle variations.206, 207 Microhepatica is suspected when the gastric axis is displaced cranially and hepatomegaly when the liver extends beyond the costal arch with rounded edges. Radiographs are unreliable in assessing asymmetric change in hepatic size. Abdominal serosal detail is decreased when ascites is present.

Hepatic ultrasonography is the preferred imaging modality for the initial evaluation of dogs with suspected CH because it permits identification of alternative diagnoses or complicating factors (eg, PH, ascites, APSS, thrombi).207, 208, 209 Ultrasound imaging can assist in deciding on the most prudent method of tissue acquisition and may facilitate needle biopsy sampling.205 Hepatic ultrasonography provides information regarding size, shape, echogenicity, and echotexture of the parenchyma, as well as information on the biliary tract and main vessels.208 However, imaging the liver in dogs with CH can be challenging because this organ is located mostly under the rib cage, and its conformation varies among breeds. This modality also is highly operator‐dependent, and therefore the results of published work vary with the experience of the sonographer and the type of equipment used.

Ultrasound findings in the liver of dogs with CH or cirrhosis often are diffuse. Hepatic size remains subjectively assessed by estimating the position of the liver with the probe placed in a subcostal position. Generally, liver size is variable with CH, more often being small, especially with advanced disease.15, 27, 39, 159, 165, 168, 175, 183, 185 Several factors such as patient position and gastric distention may affect estimation of liver size. In late CH, when liver size is decreased, evaluation is more difficult.

The liver normally is hypoechoic compared to the spleen. The liver in CH tends to be hyperechoic because of the presence of fibrosis or glycogen‐type vacuolation. As CH progresses, the echotexture of the liver becomes heterogeneous with small hypoechoic nodules. Heterogenicity may vary among liver lobes. Concurrent disease such as acute inflammation, glycogen or lipid vacuolar change, and benign nodular hyperplasia can affect liver size, contour, and echogenicity.

Mild or early grades of CH may affect liver size or echotexture minimally, which may account for the reported poor sensitivity of ultrasonography in detecting CH at different stages.209, 210, 211, 212, 213 Liver size was normal in 14%‐57% of dogs with CH in several studies, but the stage of disease was unclear.6, 15, 27, 168, 183, 185, 211 Thus normal ultrasonographic appearance of the liver should not dissuade the clinician from hepatic biopsy in a dog with suspected CH.211, 213

The features of microhepatica, irregular hypoechoic nodules, and irregular margins often are seen in end‐stage CH,170, 185, 186 although in some advanced cases the liver still can appear relatively normal. Ultrasonographic evidence of PH may accompany late‐stage CH (Table 13). These signs include the presence of ascites, APSS, edema in the gallbladder wall, gastrointestinal wall or pancreatic region, decreased portal blood flow velocity (mean velocity < 10 cm/s), hepatofugal blood flow or both.215, 216, 217, 218, 219 Acquired portosystemic shunts usually appear as plexuses of tiny tortuous vessels located caudal to the kidneys, or as a splenorenal anastomosis flowing from the splenic vein to the plexus, the left renal vein, caudal vena cava, or aberrant vessels in the mesentery; all best seen with color or power Doppler.208, 215, 219 Determination of portal flow dynamics (velocity, direction of flow) is technically challenging and highly dependent on operator experience and skill.

Table 13.

Coagulation parameters in dogs with chronic hepatitis

| Coagulation parameter | Percent changed | Number of studies (# dogs)a |

|---|---|---|

| PT prolongation | 47 ± 30 | 10 (224) |

| aPTT prolongation | 42 ± 15 | 10 (224) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 23 ± 17 | 7 (117) |

| Anemia | 34 ± 27 | 11 (237) |

| Hypofibrinogenemia | 57 ± 32 | 7 (102) |

| Decreased protein C activity | 69 ± 29 | 4 (61) |

| Decreased antithrombin | 23 ± 17 | 2 (19) |

Portal vein thrombosis (PVT) can develop as a complication of CH in dogs.220, 221 In the presence of ascites, abdominal pain, and thrombocytopenia, PVT should be suspected and the portal vein carefully evaluated for presence of a thrombus that can be nearly anechoic to moderately echogenic. Thrombi also may be discovered in other venous beds, most often involving splenic vasculature. Abdominal effusion, patient body conformation, or the presence of abdominal pain may obfuscate detection of PVT by ultrasound examination.222

The use of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to characterize liver architecture in CH has not been reported in dogs. However, CT angiography is of particular interest in dogs with small livers and those with suspected PH, PVT, or APSS.219

In humans, MRI features can distinguish between acute versus chronic diffuse liver diseases by quantifying biomarkers such as lipid, iron, and collagen.223 Application of these techniques could change the diagnostic and therapeutic approach to chronic hepatopathies in the future.

Key points associated with imaging are summarized in Table 12.

Table 12.

Key points: Imaging

|

6. BIOPSY ACQUISITION

6.1. Pre‐biopsy considerations

The primary concern for any hepatic sampling technique is post‐procedural hemorrhage. Although the risk of hemorrhage post‐biopsy exists in dogs with CH, the prevalence is poorly documented. Published studies of post‐biopsy hemorrhage including a heterogenous group of hepatic disorders indicate a 1.2%‐3.3% incidence of bleeding complications.224, 225, 226, 227, 228, 229 However, many patients with moderate to severe coagulation abnormalities were pretreated with fresh frozen plasma (FFP) transfusions before liver biopsy likely influencing observed complications.

Assessment of bleeding risk in CH is challenging because of the liver's complex and antagonistic role in the synthesis and degradation of pro‐ and anti‐thrombotic proteins and its role in fibrinolysis.214, 230, 231, 232, 233 Assessment by evaluation of prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), plasma fibrinogen concentration, platelet count, or buccal mucosal bleeding time (BMBT) does not consistently predict risk of bleeding after liver biopsy in humans.234, 235, 236, 237 In humans, there is consensus that moderate to severe prolongations in PT and aPTT (>1.5 × upper limit of normal), platelet count <50 000/μL, anemia (PCV < 30%), and low plasma fibrinogen concentration (<100 mg/dL) have some predictive ability in assessing bleeding risk and thus these variables have been incorporated into pre‐procedural standard of care guidelines.237, 238, 239, 240

Coagulation and hematological abnormalities may exist in dogs with CH. Mild anemia develops in approximately one‐third of affected dogs (Table 13) where it may reflect gastrointestinal bleeding from mucosal ulceration, coagulopathies, or anemia of chronic disease. Dogs with CH appear to be predisposed to duodenal ulceration.241, 242 Microcytosis frequently accompanies APSS.186 Mild subclinical thrombocytopenia occurs in approximately 23% of affected dogs, typically in later stage disease where it may be associated with a consumptive process or decreased production of thrombopoietin by hepatocytes.168, 185 Thrombocytopathia may develop in some dogs with CH.243, 244 Mild to moderate prolongations of PT and aPTT occur in approximately 40% of affected dogs presumably reflecting synthetic failure or vitamin K deficiency.230 The consensus panel recognizes inherent variability in point‐of‐care testing for PT and aPTT and that there is inconsistent concordance with reference laboratory testing. Low plasma concentrations of fibrinogen occur in 60% of affected dogs, particularly in those with late stage disease.161, 165, 183, 231, 244 Anticoagulants protein C and antithrombin are decreased in 70 and 23% of dogs with CH, respectively, and decreases may be more common in dogs with APSS.157, 183, 186, 189, 231, 244

Thromboelastography (TEG) commonly is used to evaluate coagulation status and guide clotting factor repletion and fibrinolytic treatments in human liver transplant patients. In humans, TEG analysis can predict bleeding tendencies in cirrhotic patients.245, 246, 247 Thromboelastography studies in dogs with CH suggest that hypocoagulable, hypercoagulable, or normocoagulable states exist,183 with up to 25% of affected dogs being hyperfibrinolytic.183 At this time, the value of TEG in predicting coagulation status in dogs with CH is unknown. Plasma fibrinogen concentrations seemingly reflect TEG indices of clot strength in dogs with liver disease.183, 229, 248, 249 As such, plasma fibrinogen concentration is recommended for bleeding risk assessment in CH.250, 251, 252

Despite the lack of studies in veterinary medicine that show correlation with in vitro coagulation studies and iatrogenic hemorrhage after liver biopsy, bleeding can be a serious complication of invasive procedures and there is value in identification of high‐risk patients. The consensus panel's recommendations for coagulation assessment are summarized in Table 14. Preexisting anemia (PCV < 30%) decreases the threshold for development of hemodynamic instability after hemorrhage and may affect platelet dynamics, provoking hemorrhage.253, 254

Table 14.

Test used to determine risk of bleeding complications in dogs with chronic hepatitis

| Bleeding risk assessment test | High risk |

|---|---|

| PCV | <30% |

| Platelet count | <50 000/uL |

| PT, aPTT | Either >1.5 × ULN |

| Fibrinogen | <100 mg/dL |

| vWF activitya | <50% |

| BMBTa | >5 minutes |

Abbreviations: aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; BMBT, buccal mucosal bleeding time; PT, prothrombin time; ULN, upper limit of normal; vWF, von Willebrand's factor.

In predisposed breed such as Doberman Pinscher, Scottish Terrier, Shetland Sheepdog, Golden Retriever, Old English Sheepdog, Rottweiler, German Shepherd Dog, Schnauzer, Corgi, and Chesapeake Bay Retriever.

If a liver biopsy is elective, and the patient is receiving drugs affecting coagulation, such drugs should be discontinued for an appropriate duration of time before biopsy.

In dogs identified with risk for bleeding or development of anemia, anticipatory preparation for potential blood component treatment is recommended. High‐risk dogs ideally should have hepatic biopsy performed via laparoscopy where tissue injury is minor compared to laparotomy and hemostasis can be more tightly controlled compared to ultrasound‐guided needle biopsy methods. Strict attention to proper technique regardless of the method of biopsy is warranted, and dogs should be hospitalized overnight in a facility that can provide direct observation. There is not enough evidence to recommend routine prophylaxis with FFP or other blood products, vitamin K, or protease inhibitors, and their use should be considered on a case‐by‐case basis. Although these interventions may have beneficial effects in correcting abnormal laboratory parameters in various clinical settings, there is little clinical evidence that they decrease the risk of bleeding in dogs with CH undergoing liver biopsy. Administration of cryoprecipitate and desmopressin (DDAVP) is warranted in dogs with proven von Willebrand disease.

Risks of hepatic biopsy other than hemorrhage include anesthetic complications, air embolism and pneumothorax (with laparoscopy), and infection.210, 255

6.2. Sampling methods

The diagnosis of CH requires histopathologic evaluation of liver biopsy specimens. Hepatic sampling can be done by ultrasound‐guided percutaneous core biopsy, at laparoscopy using a 5‐mm cup forceps, or by wedge biopsy at laparotomy. The advantages and disadvantages of each method are highlighted in Supporting Information Table S2. Fine‐needle aspirates have no role in the definitive diagnosis of CH, because they often miss inflammatory infiltrates, extent of fibrosis, or abnormal Cu accumulation.256, 257, 258, 259

In general, larger biopsy specimens obtained during laparoscopy or laparotomy are of better diagnostic quality, and are recommended for the diagnosis of CH. If biopsy specimens cannot be obtained by laparoscopy or laparotomy, 14‐16 G percutaneous ultrasound‐quided biopsies, if performed correctly, can provide adequate specimens.

During surgical procedures, biopsy specimens should not be obtained exclusively from the periphery of liver lobes if these appear fibrotic.260 Studies have shown that both central and peripheral biopsy specimens can be obtained safely.261 Quantitative hepatic Cu measurement using 1 of the hepatic biopsy specimens is recommended. The specimen should be taken from the least‐affected region, avoiding regenerative nodules and highly fibrotic lobes, both of which may underrepresent hepatic Cu burden.262, 263, 264

At least 12‐15 portal triads are recommended for proper evaluation of hepatic biopsy specimens.265 This number of triads can be reliably achieved only if multiple needle (n > 4) or laparoscopic cup forceps biopsy specimens (n = 2‐4) are obtained.265, 266 In 1 study, the diagnostic accuracy of 2 18‐gauge needle biopsy specimens was compared to a gold standard of surgical wedge biopsy of the liver in 124 patients.267 The overall discordance between the 2 methods was 67% in dogs with CH with or without cirrhosis. Numerous studies have documented substantial variation among liver lobes in terms of gross appearance and histologic features in dogs with CH.226, 267, 268 This variation highlights the need to collect biopsy specimens from multiple liver lobes. These specimens are in addition to those needed for bacterial culture and Cu quantification.

Biopsy specimens should be handled carefully to avoid crush and fragmentation artifact. Tissue should be placed promptly into neutral buffered formalin. Inking of specimens allows identification of lobe origin when samples are embedded together for viewing on 1 slide. Additional biopsy specimens are placed immediately in appropriate transport media for aerobic and anaerobic bacterial culture and in an empty glass tube for Cu quantification.

Approximately 20‐40 mg of liver (wet weight) are required for Cu quantitation using atomic absorption spectrometry. This amount equates to 1 full 14 G (2‐cm long) needle biopsy specimen or half of a 5‐mm laparoscopic biopsy specimen. A full length 18 G needle biopsy provides only 3‐5 mg of liver tissue255 and Cu measurement will be erroneously low.263

The consensus panel recommends the following for hepatic biopsy specimen acquisition: a minimum of 5 laparoscopic or surgical biopsy specimens from at least 2 liver lobes should be obtained for histopathology (3), aerobic and anaerobic culture (1) and quantitative Cu analysis (1). If needle biopsy specimens are obtained, collecting multiple biopsy specimens using a 14 or 16 G needle will decrease sampling error. Some studies suggest that the risk of bleeding, although independent of needle gauge, increases with the number of biopsy specimens obtained.224

After biopsy, the patient should be kept quiet and closely monitored for complications, especially hemorrhage. Pain medication should be given depending on the type of biopsy procedure. Vital signs (heart rate, femoral pulse quality, mucous membrane color, PCV, and blood pressure) should be monitored before the procedure and every 2 hours up until 6 hours post‐biopsy. If there are no signs of hemodynamic instability and no clinically relevant decrease in PCV at that time (>6%‐10% decrease) then substantial post‐biopsy hemorrhage is unlikely. If clinically relevant hemorrhage is suspected, abdominal ultrasound examination is used to identify newly accumulated effusion that may warrant sampling.

Key points related to biopsy acquisition are summarized in Table 15.

Table 15.

Key points: Biopsy Acquisition

|

6.3. Biopsy specimen interpretation

Biopsy specimens should be promptly placed into 10% neutral buffered formalin in at a ratio of 10:1 (fixative to tissue). No sample should be thicker than 0.5‐1 cm to ensure proper fixation.210, 255

Small biopsy specimens (needle biopsies), generally require special handling and the use of specialized mesh cassettes to protect needle cores from fragmentation during transportation. Non‐compressive sponges can be used but care should be taken to avoid distortion of tissue caused by cassette compression. Care is needed to select sponges that do not perforate the samples.

The key features of liver biopsy specimen interpretation include evaluation of inflammation, cellular injury or death, fibrosis, ductular reaction, and pigment deposition. Thorough evaluation of liver biopsy specimens requires application of several special stains in addition to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). These enable better evaluation of remodeling, as well as Cu, iron, and connective tissue deposition (Table 16).

Table 16.

Staining of biopsies from dogs with chronic hepatitis

| Category | Stain | Feature stained |

|---|---|---|

| Required | Hematoxylin and eosin | Nuclear and cytoplasmic features |

| Rhodanine/Rubeanic acid | Copper | |

| Picrosirius red/Masson's trichrome | Collagen | |

| Recommended | Gordon and Sweet | Reticulin |

| Perl's | Iron | |

| Schmorl's | Lipofuscin | |

| Situational | Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS)/diastase | Glycogen/non‐glycogen carbohydrates |

| Oil Red O | Lipid | |

| Hall's stain | Bile | |

| Stains for infectious diseases, e.g; Ziehl Neelsen (acid fast), Fite's, Gomori methenamine silver (GMS), PAS, FISH | Organisms |

Abbreviation: FISH, fluorescent in situ hybridization.

The type of inflammation should be characterized, (eg, neutrophilic, suppurative, lymphocytic, granulomatous, or pyogranulomatous), as these patterns can suggest underlying pathogenesis. The extent and type of the inflammation should be graded using a standardized scheme to give an activity score, or at least characterized using language that conveys lesion severity.1, 210 The location of the inflammation within the portal tract and the lobule should be identified. The presence of interface inflammation, involving injury extending beyond the portal tract boundaries (ie, extending beyond the limiting plate), should be identified and its extent characterized. Necrosis, seen as apoptosis or lytic necrosis, can affect hepatocytes, biliary epithelium, sinuosiodal endothelium, sinsusoidal lining cells, and transiting inflammatory cells. The types of cells affected should be identified. The extent and distribution of cell death (eg, individual cell, massive, multifocal, centrilobular, and periportal) should be characterized and graded.269 Vacuolar change (eg, discrete lipid vacuoles or glycogen‐type cytosolic accumulation) can coexist with CH.270 These changes may represent hepatocyte injury or hepatocyte response to inflammatory mediators, cytokines, or endotoxin or both.

Fibrosis is a key feature in the diagnosis of CH, because it is the main hallmark of chronicity. The location (eg, portal, centrolobular, and sinusoidal) and extent should be described using a standardized scheme or language that conveys lesion severity.1, 269 Special stains such as Sirius red or Masson's trichrome are particularly useful to evaluate fibrosis and to ensure that fibrous septa are not overlooked. Stains for fibrous tissue and reticulin can help distinguish between new collagen synthesis and parenchymal collapse, a distinction not always straightforward in H&E stained sections. Often, but varying with etiology, fibrosis begins as expansion of the portal tract connective tissue. With time, thin septa may extend into the periportal regions and evolve into progressively thicker septa that bridge between portal tracts or to central vein regions. The final stages of fibrosis are characterized by prominent bridging septa and nodular regeneration of hepatocytes. At this point, the diagnostic term applied is cirrhosis or end‐stage liver. Reticulin stain can highlight subtle structural changes such as centrilobular collapse, focal loss of parenchymal integrity, or early nodular regeneration.

Ductular reaction (ie, proliferation of small ductular structures derived from either mature biliary epithelial cells or bipotential progenitor cells) often is seen in chronic liver injury and is not necessarily indicative of biliary disease.271, 272 It is common in many dogs with CH and also develops in LDH.165, 177, 180

Evaluation for pathologic Cu accumulation is mandatory in dogs with CH.17, 22 Rhodanine or rubeanic acid staining for Cu or Cu‐binding proteins detects the presence, acinar distribution, and can subjectively estimate the severity of Cu accumulation. In dogs, pathologic accumulation of Cu is almost always most severe in centrilobular regions. It can advance into midzonal and periportal hepatocytes with increasing Cu accumulation. Periportal accumulation is often nonspecific and involves small amounts of Cu that are not clinically relevant. A subjective grading scale should be used to score the severity of Cu accumulation. Judging the clinical relevance of Cu accumulation involves considering its association with necrotic hepatocytes and development of small “copper granulomas.” Copper granulomas are unique macrophage aggregates integrated with lymphocytes, pigmented macrophages, variable neutrophils, and occasional plasma cells, with intralesional eosinophilic refractile Cu‐protein aggregates in foamy macrophages with rhodanine staining. Semiquantitative scores generated with these scoring systems have good correlation with quantitative measures and should be part of routine biopsy specimen evaluation.17, 18, 21, 31 Because the amount of Cu may vary among liver lobes, pathologists should be able to identify which lobes are being evaluated histopathologically. The preparation of sections from different liver lobes on a single slide facilitates overall assessment.

Atomic absorption spectroscopy is the gold standard for quantitative assessment of hepatic Cu content and requires only a small amount (20‐40 mg) of tissue for accurate determination.21, 262 Analysis should be reported on a dry weight basis. Other analytical methods are available (inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy30, 273 and neutron activation analysis15, 274, 275), but these methods require publication of additional validation. Digital quantification of Cu using scanning of rhodanine‐stained biopsy sections may be the most accurate method for determination of tissue Cu, because it quantifies Cu in the rhodamine‐stained tissue and can avoid variations in Cu content that occur in CH, particularly once normal lobular architecture has been distorted.262

When there are discordant results between quantitative and qualitative evaluations of hepatic Cu content, or a sample for Cu analysis was not obtained during biopsy, deparaffinized tissue from the block or fresh frozen tissue can be used to perform additional Cu analysis.263

Special stains for infectious agents can be useful in selected circumstances. Granulomatous or pyogranulomatous inflammation should prompt a search for infectious etiology. Acid fast stains for mycobacteria and periodic acid Schiff or silver stains can detect fungi. Gram staining or fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH)25, 51, 187 can detect bacteria. Immunohistochemical staining can detect viruses and protozoa. Saving snap‐frozen samples of liver is useful for molecular techniques such as PCR.

Once the pathologist has assessed the tissue section, a morphologic diagnosis is made. A thorough pathologic assessment is facilitated by having comprehensive clinical data, multiple sites of collection of adequate tissue specimens that are properly labeled, and inclusion of gross images of the liver. An exchange of information between clinician and pathologist optimizes liver biopsy specimen interpretation. In many instances, it may be preferable to send samples from challenging cases to a pathologist with expertise in hepatic pathology.276, 277

Key points related to biopsy interpretations are summarized in Table 17.

Table 17.

Key points: Biopsy Interpretation

|

7. TREATMENT

Treatment of CH in dog should target the causative agent (Table 2). Unfortunately, CH in the dog often is often idiopathic.6, 27, 38 If thorough diagnostic investigation fails to disclose a plausible etiology, then treatment with nonspecific hepatoprotective agents (see below) with or without a trial of immunosuppressive treatment may be indicated. Immunosuppressive interventions should be based on histologic evidence of a suspected immune‐mediated process.

7.1. Infectious

Infectious hepatopathies require antimicrobial treatment. Discussion of these interventions is beyond the scope of this consensus statement and readers are referred to reviews and recent book chapters.278, 279, 280, 281 In some cases, treatment of the inciting infectious agent (eg, leptosporosis) may lead to clinical remission of CH, whereas in other cases full remission may not be achieved, possibly as a result of pathogen‐induced self‐perpetuating immune disease.51

7.2. Drugs and toxins

Suspected hepatotoxic drug or supplement exposure should be promptly discontinued and hepatic recovery monitored by serial biochemical evaluations. In most cases, antioxidant treatment is indicated. In dogs with histologically identified inflammatory infiltrates, short courses of an anti‐inflammatory dosage of corticosteroids may be beneficial.282 It is unclear whether dogs with preexisting CH are predisposed to drug‐induced liver disease. In human patients, CH is a risk factor for some drug reactions.283, 284, 285 Some, but not all, panel members felt that dogs with CuCH were at increased risk for nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug‐induced liver injury.103

7.3. Copper‐associated CH

Increased hepatic Cu concentration in a dog with CH is abnormal and should be managed. Excess hepatic Cu increases risk for oxidative membrane injury, generating injurious hydroxyl and superoxide radicals.286 Treatment for CuCH involves lifelong dietary Cu restriction and removal of Cu from the liver. After completion of chelation, zinc may be administered to restrict enteral Cu absorption.

Copper‐restricted diets (Table 18) that provide <0.12 mg/100 kcal of Cu are recommended in all dogs with a Cu concentration >600 μg/g dw.11, 16, 17, 35 Dietary Cu restriction does not replace the need for Cu chelation. Because most currently available Cu‐restricted diets are modestly protein restricted, and because most dogs with CH do not require protein restriction, additional protein supplementation is advised. If dogs will not eat a commercial Cu‐restricted diet, a homemade Cu‐restricted diet may be formulated by a clinical nutritionist. Copper concentration of water should be <0.1 μg/g. With Cu plumbing, flushing the line for 5 minutes eliminates Cu. If bottled water is used, it should be distilled. Dietary Cu restriction is advised as lifelong management unless a point source of Cu contamination in the environment is identified.

Table 18.

Treatment of copper (Cu) associated chronic hepatitis

| Treatment | Mechanism of action | Dose/duration | Formulations | Other relevant pharmacology | Adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary Cu restriction | Limits Cu uptake in intestine Diet: <0.12 mg Cu/100 kcal Water: limit Cu intake in water <0.1 μg/g Flush Cu pipes for 5 minutes Bottled water should be distilled |

AAFCO recommendations for Cu = 0.18 mg/100 kcal Restricted diet:0.09‐0.12 mg/100 kcal Duration: lifetime |

Commercially available Cu restricted diets: Royal Canine Hepatic (St Charles, MO) Hills L/d Liver Care, (Topeka, KS) Purina HP Hepatic (Europe only), (St. Louis, MO) Homemade diet (balanced canine diet‐ best formulated by a clinical nutritionist) |

Copper restricted diets are mildly protein restricted: 3.9‐4.1 mg/100 kcal Minimal protein requirement = 4.5 mg/100 kcal |

Most dogs do not need protein restriction therefore supplement commercial Cu restricted diets with protein source: 0.5‐1.5 g protein/kg body weight. Copper content of alternative protein sources: https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/ |

| D‐Penicillamine | Chelates Cu, with urinary excretion Upregulates hepatic metallothien binding intracellular Cu |

10‐15 mg/kg BID Administer 30 minutes before or 2 hours after a meal Treatment duration based on repeat hepatic Cu quantification or surrogate monitoring of ALT Maintenance therapy at 2‐3 times weekly, once a day with a reduced dose (50%) observationally effective |

Cuprimine (Bausch Health, Quebec, Canada) ‐DePen (Meda Pharmaceutical, Somerset, NJ) Compounded formulations in the United States |

Anti‐inflammatory Anti‐fibrotic Co‐treatment with zinc contraindicated |

Common: Nausea, vomiting, hyporexia Dermatological reactions Occasional proteinuria (glomerulonephritis) Induced ALP and glycogen vacuolar hepatopathy Rare: Immunologic reactions (joint, liver) Bone marrow dyscrasia Tetratogenic Cu and Zn deficiency (rare) Pyridoxine deficiency (rare) (supplement with 10‐25 mg daily) Monitor UPC, CBC and liver enzymes |

| Trientine | Copper chelator | 5‐7.5 mg/kg PO BID | Syprine (Bausch Health, Quebec, Canada) | Prohibitively expensive | Acute kidney injury |

| Zinc | Interferes with enteric zinc absorption by inducing intestinal metallothionein that binds Cu Induces hepatic metallothionein |

8‐10 mg/kg/d of elemental zinc Decoppers slowly therefore only suitable for maintenance treatment |

FDA approved: Galzin (Teva Pharmaceuticals, North Wale, PA) zinc acetate (30% zinc) OTC: zinc gluconate Gluzin (Extreme V, Lowes, DE) (13% zinc) |

Monitor serum levels for effective dose: >200 μg/dL | Common: Nausea, vomiting Rare: Hemolytic anemia. Monitor serum levels for toxic dose: <800 μg/dL |

Abbreviations: AAFCO, Association of American Feed Control Officials; CBC, complete blood count; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; UPC, urine protein creatinine ratio; Zn, zinc.

D‐penicillamine (D‐Pen) is the Cu chelator of choice (Table 10). This drug binds hepatic Cu which subsequently is eliminated in urine.9, 287, 288 In addition, D‐Pen increases metallothionein in hepatocytes (detoxifying intracellular Cu) and enterocytes (facilitating fecal elimination) and has mild anti‐inflammatory and anti‐fibrotic properties.288, 289, 290, 291, 292 D‐penicillamine is given PO on an empty stomach because food substantially decreases bioavailability.293

D‐penicillamine combined with dietary Cu restriction usually normalizes hepatic Cu concentrations as high as 1500 μg/g dw within 6 months. Hepatic Cu concentrations of 2000‐3000 μg/kg dw typically normalize within 9 months. Higher concentrations may require longer chelation intervals. Chelation may fail or take longer if D‐Pen is not given with a Cu‐restricted diet. Treatment efficacy is best determined by repeat quantification of hepatic Cu concentration. Normalization of serum ALT activity is used as a surrogate to estimate treatment success. Because serum ALT activity lacks the sensitivity to determine residual mild Cu accumulation and associated hepatic damage,194 treatment for 1 month after ALT activity returns to normal is recommended. It is difficult to predict the duration of chelation necessary for individual dogs.12

Adverse effects of D‐Pen (Table 18) are mostly gastrointestinal. Strategies to combat these include gradual dose escalation, administering D‐Pen with a small piece of meat, or concurrent use of antiemetics. Some panel members preferred coadministration of a short course of low‐dose corticosteroids to stimulate appetite when dogs are inappetent. Other adverse effects of D‐Pen are rare, with proteinuria or skin eruptions being most common. D‐penicillamine may induce ALP activity and a mild to moderate vacuolar hepatopathy that resolves with drug discontinuation.44 Co‐treatment with D‐Pen and zinc is strictly contraindicated because each negates the benefits of the other.

Because of the high cost of D‐Pen products (Table 18) in the United States, the consensus panel members in the United States routinely used D‐Pen compounded at specialty pharmacies and agreed that these products are effective.

Experience with alternative Cu‐chelating agents such as choline tetrathiomolybdate and trientine (Table 18) in dogs is limited. Therefore, they cannot be recommended at this time.293, 294, 295, 296, 297

Zinc interferes with enteric Cu uptake via metallothionein induction (Table 18).298, 299 Zinc acetate decreases hepatic Cu in a small study in dogs.299 Zinc administration, however, decreases hepatic Cu concentrations slowly, making it inappropriate for acute interventions.300 One study demonstrated no additional benefit when PO zinc was combined with a Cu‐restricted diet.10 Based on limited information, a zinc dosage for CuCH has been extrapolated (Table 10). Zinc must be given on an empty stomach. An over‐the‐counter pharmaceutical grade formulation of zinc gluconate is used in Wilson's disease and a prescription drug (zinc acetate) is also available. Plasma zinc concentrations should be measured to assure therapeutic but not toxic serum concentrations. Gastrointestinal intolerance is common and often dose limiting.

During chelation treatment, antioxidant treatment, such as S‐adenosylmethionine (SAMe) and vitamin E, is recommended because Cu causes oxidative liver injury (Table 19).113, 286, 300, 301, 302, 303, 304, 305, 306, 307, 308, 309, 310, 311, 312

Table 19.

Hepatoprotective medications used in the treatment of chronic hepatitis in dogs

| Medication | Formulation | Dose | Mechanism of action | Adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S‐adenosylmethionine (SAMe) | Unstable compound use only stabilized salts Butanedisulfonate Tosylate Phytate |

20 mg/kg PO once a day on an empty stomach Phytate salt: 8‐10 mg/kg once a daya |

Increases intracellular cysteine leading to increased hepatic glutathione synthesis Increases methylation of phospholipids and DNA which promotes membrane stability and controls production of inflammatory cytokines. Numerous other advantageous effects. Increases hepatoprotective polyamines |

Rare: Nausea |

| Vitamin E | Alpha‐tocopherol | 10 IU/kg once a day PO not to exceed 400 IU per dog, given with food to increase bioavailability | Protects against lipid peroxidation Anti‐fibrotic Anti‐inflammatory |

Overdosage: can impair vitamin K activity; may increase risk for oxidative injury because of accumulation of tocopheroxy radical |

| Ursodeoxycholate | Stable bile acid Use of generic encouraged 250 mg pill and 300 mg capsule |

15 mg/kg once a day PO given with food to increase bioavailability | Antioxidant Choleretic Immunomodulatory Anti‐inflammatory |

Rare: Nausea Diarrhea Safety studies show no adverse clinical or biochemical effects. Mild effect on TSBA levels |

| Silymarin (milk thistle) | Active ingredients: silybin A silybin B Available complexed to phosphatidyl choline to increase bioavailability but data lacking on achieving therapeutic effect |

Native extract: Dose largely undefined: 4‐8 mg/kg/d given 2‐3 times a day PC complexed: not well defined 0.7‐6 mg/kg/d PO once a day |

Antioxidant Anti‐inflammatory Anti‐fibrotic Choleretic |

Rare: Inhibits CP450 enzymes and p‐glycoprotein |

Abbreviations: PC, phosphatidylcholine; TSBA, total serum bile acid.

Pharmacologic data not published to substantiate lower dose of the phytate salt.

In some dogs with CuCH, severe lymphocytic hepatitis may reflect a concurrent primary process or reactive neoeptitope formation provoked by oxidative injury. These dogs require immunomodulatory treatment as prescribed for those with other suspected immune‐mediated necroinflammatory liver disorders. This treatment can be initiated at the time of the original diagnosis, when appropriate measures to decrease hepatic Cu fail to normalize serum ALT activity, or when repeat hepatic biopsy shows restoration of normal Cu concentrations but persistent inflammation.

Dietary Cu restriction is advised as a lifelong management strategy in any dog with CuCH. Copper‐restricted diets as a solitary intervention after chelation may maintain hepatic Cu concentration in the reference range in some dogs, but this depends on client compliance and has not been studied across many different dog breeds. Some dogs need additional chronic management strategies: either chronic low‐dose zinc or chronic intermittent low‐dose D‐Pen administration 2‐3 times weekly (5‐10 mg/kg PO). D‐penicillamine may be effective using this dosing strategy, but this has not been studied in dogs with CuCH.

7.4. Hepatoprotective agents and antioxidants

Necroinflammatory hepatic disease is associated with depletion of antioxidant defense mechanisms,172, 303, 304, 305, 306, 307 justifying the use of cytoprotective agents with antioxidant properties (Table 19).

Ursodeoxycholic acid is a relatively hydrophilic dihydroxy secondary bile acid with choleretic, immunomodulatory, antioxidant, anti‐inflammatory, cytoprotective, and antiapoptotic properties.308, 309, 310 It is widely prescribed for liver disease despite little investigation of its efficacy.311, 312 This bile acid is recommended based on the benefits shown in multiple preclinical and clinical studies in humans and in animal models of liver disease (Table 11). It is indicated for dogs with CH manifesting evidence of cholestasis, inflammation involving bile ductules, and in those with suspected bile‐borne bacterial infection.

S‐adenosylmethionine is an intermediary metabolite essential for hepatic transsulfuration, transmethylation, and decarboxylation reactions. Because severe liver injury can downregulate the enzyme controlling methionine transformation into SAMe, SAMe can become a conditionally essential nutrient.313, 314

Hepatic transsulfuration of SAMe generates glutathione (GSH), an important antioxidant in the liver. Hepatic GSH concentrations in dogs are lower compared to other species, which potentially increases their risk for oxidative injury.303 Giving SAMe replenishes hepatic GSH in dogs.315

The high reactivity of natural SAMe limits its pharmacologic potential. However, stable synthetic salts with enteric coatings allow the use of PO SAMe supplements. The initial formulation, a disulfonate salt, was replaced with a tosylate salt. Formation of a granular barrier with the tosylate salt yielded a non‐enteric coated chewable tablet. A new generation phytate salt with enteric coating is now available. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the 1,4‐butanedisulfonate salt and the pharmacokinetics of the granular tosylate salt were studied in dogs.315, 316, 317 Details of the phytate salt bioavailability have not yet been published, but it is thought to have increased bioavailability, permitting use at a lower dosage (5‐10 mg/kg). Caution is advised in selecting a SAMe product because many have unknown bioavailability and vary in SAMe content.318 The panel recommends SAMe products from reputable manufacturers for which bioavailability and pharmacokinetics in dogs and product content have been reported.315, 316, 319, 320, 321

Although there is strong preclinical evidence that SAMe has hepatoprotective actions in vitro and in animal models of liver disease, the clinical benefit of SAMe has not been rigorously investigated. A few clinical trials in humans suggest benefit in improving biochemical tests of liver function, but not in overall outcome.319, 320 In dogs, SAMe administration protected against acetaminophen hepatotoxicity and improved hepatic GSH in corticosteroid‐induced vacuolar hepatopathy.315, 321 In addition, a SAMe/silymarin formulation protected against lomustine‐associated hepatotoxicosis.96 There is a need, however, for high‐quality randomized placebo‐controlled clinical trials in well‐defined clinical populations.

Despite historical use of milk thistle derivatives (silymarin, silibinin) for liver disease in humans, and recent popularity for use in dogs with suspected liver disease, documentation of beneficial effects remains equivocal. Outcomes of in vitro and in vivo studies of silibinin are confounded by inappropriate nomenclature of different studied compounds and dose variability of active ingredients.312 The PO bioavailability of silymarin is low (30%‐50%) and the half‐life short (4‐6 hours), meaning high doses and repeated administration are necessary to obtain therapeutic concentrations.312 Studies of silymarin in humans, including National Institutes of Health‐sponsored clinical trials using highly standardized preparations, have failed to achieve projected therapeutic endpoints.322, 323, 324

Commercial formulations of silybin complexed with phosphatidylcholine have improved bioavailability (4.4‐fold increase over uncomplexed extract),325, 326, 327, 328 but it is unknown if this formulation achieves therapeutic relevance. A single study of complexed silymarin with SAMe showed protection against lomustine‐associated hepatotoxicosis in dogs.96 Toxicity has been reported rarely. Because silymarin can inhibit certain cytochrome‐p450 enzymes and p‐glycoprotein, caution is warranted if high‐dose silybin is used with polypharmacy protocols.312 Although most panel members used a combination of SAMe silybin product, additional studies are needed to clarify the clinical benefit of silymarin products in dogs with CH.

α‐Tocopherol (vitamin E) functions as an antioxidant protecting cell and organelle membranes (notably mitochondrial) from lipid peroxidation.329, 330, 331, 332 A pilot study of dogs with CH fed a vitamin E‐supplemented diet for 3 months found increased serum and hepatic vitamin E concentrations accompanied by improved GSH redox cycling, but no change in histologic features.333 Although all panel members use vitamin E in necroinflammatory liver disease, largely based on clinical evidence of its efficacy in certain liver diseases in humans,329, 330, 331, 332 they acknowledge that there is limited study of its efficacy in CH in dogs.

7.5. Immune‐mediated hepatitis

A few studies using prednisolone, azathioprine, or cyclosporine in CH have been reported in dogs and are summarized in Table 20.146, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166, 334 In these reports, some dogs with CH showed improvement, inferring an immunomodulatory or anti‐inflammatory benefit. However, it is difficult to draw general conclusions from these studies because they were done in many different breeds, used variable doses of immunosuppressive therapies with other concurrent therapies, often lacked post‐treatment histology, and involvement of Cu was not standardized or quantified.

Table 20.

Summary of studies investigating anti‐inflammatory/immunosuppressive treatment in dogs with chronic hepatitis

| Study | Design | Breeds/numbers | Drugs | Results | Important bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strombeck et al (1988)162 | Retrospective | Multiple, n = 151 | Prednisone: 2.2 mg/kg PO tapered to 0.6 mg/kg over 2‐3 weeks | Treatment increased survival from a median of 10m to 30m | Lots of Dobermans Dogs that died in first week excluded Lack of dose standardization Lack of copper exclusion Inclusion of drug associated disease |

| Favier et al (2013)163 | Retrospective | Only idiopathic CH Multiple breeds, n = 36 |

Prednisolone: 1 mg/kg/d PO for 12 weeks | Complete remission in 11/36, partial response in 8/36, no response in 17/36 Histological remission in 9/36 dogs at 3 weeks |

Only needle biopsy follow‐up No information on diet or concurrent supportive interventions |

| Bayton et al (2013)164 | Prospective | English Springer Spaniels, n = 14 | Prednisolone: 1‐2 mg/kg/d PO | Improvement in liver enzymes and bilirubin Improved survival over historical controls |

Concurrent supportive interventions No follow‐up biopsy |

| Sakai et al (2014)334 | Retrospective | Labrador Retrievers, n = 8 | Prednisone Azathioprine | Median survival 630 day (21‐2336) No improvement in survival over historical controls |

Copper status not defined No control group No biopsy follow‐up |

| Kanemoto et al (2013)165 | Retrospective | Cocker Spaniels, n = 13 | Prednisone: 0.5‐1.25 mg/kg/d PO Azathioprine: 1 mg/kg/d PO |

Longer survival than reported in historical controls | Concurrent supportive intervention No biopsy follow‐up Variability in long‐term follow‐up |

| Ullal et al (2018)166 | Retrospective | Multiple, n = 48 | Cyclosporine: 5 mg/kg BID PO | 76% obtained remission (normalization of ALT) | No biopsy follow‐up Concurrent supportive intervention |

| Speeti et al (2005)149 | Retrospective, necropsy | Dobermans, n = 14 | Prednisolone: 0.1‐0.5 mg/kg/d PO | Down regulation of MHC Class II expression | Limited to evaluation of MHC Positive copper expression |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CH, chronic hepatitis; MHC, major histocompatibility complex.

Collectively, these studies support the existence of a subset of dogs with CH that respond to immunosuppressive treatment. At present, however, not enough evidence is available to recommend an optimal immunosuppressive protocol. The following recommendations reflect the clinical observational experience of the panel without unanimous agreement regarding the best initial approach. All agreed that corticosteroids are efficacious as first‐line treatment, but acknowledged the limiting impact of drug‐related adverse effects (eg, catabolic effects, polyuria, polydipsia, hepatocyte glycogen vacuolationo or degeneration, serum liver enzyme induction) that complicate evaluation of treatment response. Additional adverse effects are especially problematic in dogs with advanced liver injury (eg, sodium and water retention that provoke ascites, catabolism, risk for enteric ulceration that may precipitate HE, complex imbalances in coagulation leading to hypercoagulability). Some panel members combine corticosteroids with another immunosuppressive drug (either azathioprine or cyclosporine) to enable more rapid tapering of the corticosteroid administration to every other day anti‐inflammatory doses. For most panelists, maintenance on the second drug alone was the goal. For other panel members, single agent cyclosporine twice a day was used as first‐line treatment to avoid the adverse effects of corticosteroids. Cyclosporoine is tapered to once a day as soon as remission is established. Mycophenolate also has been used with success as a first‐ or second‐line treatment by panel members and in combination with corticosteroids. The length of time necessary to reach remission with immunosuppressive therapy and whether or not lifelong maintenance therapy is necessary in immune mediated CH in dogs is larged undefined. Consult Table 21 for information on drug dosages, formulations, and adverse effects.

Table 21.

Use of immunosuppressive therapy in immune hepatitis

| Drug | Dose | Formulations | Adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prednisone/prednisolone | 2 mg/kg once a day gradually tapered to 0.5 mg/kg every other day No greater than 40 mg/d/dog |

No evidence that hepatic disease limits conversion of prednisone to prednisolone When ascites is present use dexamethasone (no mineralocorticoid effect) or methylprednisolone (“minimal” mineralocorticoid effect) equivalents to avoid sodium retention |

Induction of liver enzymes particularly ALP and GGT Steroid hepatopathy PU/PD/PP Hypercoagulability Nausea/vomiting Catabolism Sodium retention Subclinical UTI |

| Azathioprine | 2 mg/kg (or 50 mg/m2) SID for 14 days then every other day | Generic formulation acceptable | Bone marrow suppression Hepatotoxicity (rare) |

| Cyclosporine | 5 mg/kg BID tapered to once a day | Use modified cyclosporine only Atopica (Elanco, Greenfield, IN) or Neoral (East Hanover, NJ) Pharmacokinetic (trough levels) and pharmacodynamic (IL‐2 suppression) may optimize dose administration |

Common: Nausea/vomiting Gingival hyperplasia Rare: Hepatotoxicity Subclinical UTI Opportunistic infections |

| Mycophenolate | 10‐15 mg/kg BID | Generic formulations acceptable | Diarrhea which may be delayed |

Abbreviations: ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, gamma‐glutamyl transferasel IL‐2, interleukin 2; PD, polydipsia; PP, polydipsia; PU, polyuria; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Key points associated with treatment are summarized in Table 22.

Table 22.

Key points: Treatment

|

7.6. Dietary management