Abstract

Background and Objectives

We reviewed the literature on older adults (OAs) who are caring for persons living with HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), with the goal of adapting models of caregiver stress and coping to include culturally relevant and contextually appropriate factors specific to SSA, drawing on both life course and cultural capital theories.

Research Design and Methods

A systematic literature search found 81 articles published between 1975 and 2016 which were reviewed using a narrative approach. Primary sources of articles included electronic databases and relevant WHO websites.

Results

The main challenge of caregiving in SSA reflects significant financial constraints, specifically the lack of necessities such as food security, clean water, and access to health care. Caregiving is further complicated in SSA by serial bouts of caring for multiple individuals, including adult children and grandchildren, in the context of high levels of stigma associated with HIV. Factors promoting caregiver resilience included spirituality, bidirectional (reciprocal) caregiving, and collective coping strategies.

Discussion and Implications

The creation of a theoretical model of caregiving which focuses more broadly on the sociocultural context of caregiving could lead to new ways of developing interventions in low-resources communities.

Keywords: Caregiving, International issues, Stress and coping

The confluence of population aging and the HIV/AIDS epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has resulted in a wide range of psychosocial and health impacts that are not fully understood (AVERT, 2015). SSA accounts for 70% of all cases of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA), with prevalence ranging widely across the different countries in the region (UNAIDS, 2015). HIV/AIDS has eroded the working capacity of communities, and affected needed financial and material support to survive (Kang'ethe, 2012; Knodel, Watkins, & VanLandingham, 2002). Thus, many older adults (OAs; 50+) have been forced into primary caregiving roles as younger adults, who would normally provide support to aging parents and their children, died from HIV/AIDS (Mathambo & Gibbs, 2009).

Given the contextual nature of older adult (OA) care giving in SSA to PLWHA, it is important to understand the role of context (aging, HIV/AIDS, war, poverty) in the development of effective interventions. In SSA as elsewhere, care is shaped by the culture which informs the dimensions of “good” care, culture-specific approaches to symptoms and illness, and bereavement (Gysels, Pell, Straus, & Pool, 2011).

It is critical to address resource deficits for PLWHA and surviving orphans, including lack of basic infrastructure, food insecurity, and poor record keeping (Njororai & Njororai, 2013; Oppong, 2006). Unemployment and industrialization may also play a critical role in the recruitment of OA caregivers, as these forces often lead to urban migration and high prevalence of HIV/AIDS which, in turn, resulted in the creation of orphans and vulnerable children (OVC; Dolbin-MacNab & Yancura, 2017). Patriarchy and the marginalization of women exacerbates care deficits (Schatz & Seeley, 2015). Women, and increasingly OA women, provide most of the informal care in SSA. The emergence of male caregivers who provide both instrumental (financial) and nursing care is reflective of a larger demographic shift related to the feminization of labor in urban centers and the lack of employment for men (Block, 2016; Block, 2014).

The main goal of this review article is to extend sociocultural models of stress and coping to a true multilevel model which incorporates the impact of the larger historical context on social institutions, which in turn affect individual level stress and coping practices. We will do this through focusing on the impact of cultural resources on caregiver wellbeing in OAs providing care to persons with HIV/AIDS.

Sociocultural Models of Stress and Coping

Sociocultural values are important for the caregiving process (Pearlin, Mullan, Semple, & Skaff, 1990). Using Hispanic American caregivers as exemplars, Aranda and Knight (1997) defined culture in terms of a bipolar dimension of individualism and familism. They hypothesized that individuals adhering to individualism would report higher levels of caregiving burden because the provision of care would interfere with the caregiver’s autonomy, whereas those adhering to familism would report lower levels. Surprisingly, this was not supported by their data. Knight and Sayegh (2010) recommended that additional research on ethnic differences in caregiving needed to explore a range of finer-grained dimensions of cultural values that are associated with both positive and negative effects on caregiver health outcomes. Aldwin (2007) suggested that cultural values influence coping resources, including social support and coping strategies, as well as the cognitive appraisal of burden, which might prove to be a fruitful avenue for expanding the model.

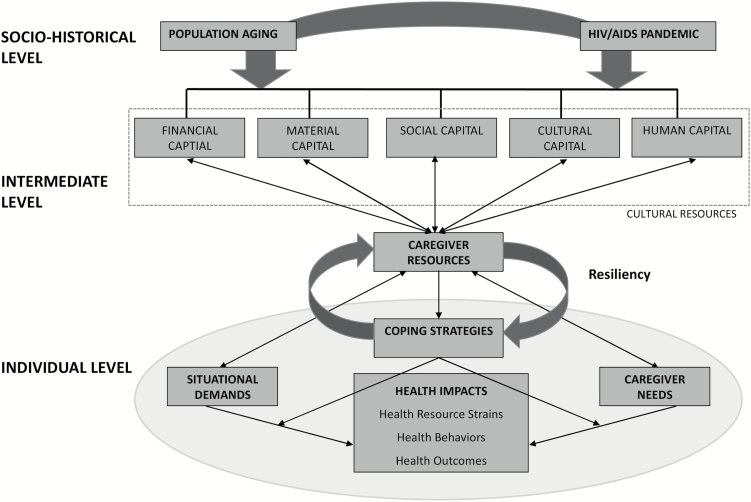

Following Knight and Sayegh’s (2010) recommendations, we expanded their stress and coping model (see Figure 1). (Knight and Sayegh’s original model is highlighted by a gray background.) The model consists of three levels: the sociohistorical, the intermediate, and the individual contexts. We drew on life course theory (Elder & George, 2016), which posits that individuals’ developmental paths are embedded in and transformed by local and global contexts and events that occur in the historical period and geographical location in which they live. In our model, the sociohistorical level is represented by the current confluence of population aging and the HIV epidemic. In SSA, the role of OA has been transformed in part because the HIV/AIDS epidemic has resulted in over a million deaths among working age adults (15–49), creating a “missing generation” (AVERT, 2015).

Figure 1.

Sociocultural multileveled model of stress and coping. Sayegh and Knight’s model is highlighted in gray.

The second level of the expanded model in Figure 1 reflects Bourdieu’s theory of cultural capital or resources as the intermediary link between the larger sociohistorical context and immediate context of care (Bourdieu, 1986). Conceptually, culture can be understood to be a resource or capital that can be spent, bartered, saved, discarded, created, or extinguished. Five types of cultural resources have been identified (Bourdieu, 1986; Heckman, 2007). Material capital includes the built environment, including hospitals, housing, transportation, food production, and sanitation systems (Lynch, Smith, Kaplan, & House, 2000; Ralston, 2017), and is a predictor of health and wellbeing among OAs (Ralston, 2017). Financial capital refers to access to tangible assets that can be used to purchase goods and services (Galama, 2015). Cultural capital refers to one’s knowledge base, skill sets, assets, and social status (Bourdieu, 1986). Social capital refers to resources linked to social networks. The amount of social capital depends on the size of network connections and the resources possessed by network members. Human capital refers to an individual’s genetic assets concerning appearance, intelligence, and talents, as well as their health status (Heckman, 2007). Note that culture also includes barriers to resources in these categories, such as some inequalities, health disparities, and social stigma.

The third level is the individual level and involves matching the situational demands of caregiving with the cultural resources needed to utilize or create coping strategies in response to these demands (see Aldwin, 2007). The double-headed arrows in the model suggest dynamic, transactional relationships among established cultural resources, caregiving situational demands, caregiver needs, and the resources available to caregivers. When the system is in a state of disequilibrium, caregivers may create new cultural resources to meet these demands. Caregiver resiliency is the ability of caregivers to adapt by using thee cultural resources, and is illustrated by the movement from the intermediate level to the individual level (Aldwin & Igarashi, 2016).

Our expanded model differs from Knight and Sayegh’s model in two distinct ways. First, we have expanded their definition of cultural values to refer to resources that can either be pre-existing or newly created to meet ongoing caregiving demands. Secondly, their model focuses on caregiving for patients with dementia, but we believe that this expanded conceptual model may be applicable to a wide range of illnesses and caregiving situations, including HIV-related caregiving. We will apply our conceptual model to the systematic review of the literature on OA caregivers to persons impacted by and/or living with HIV/AIDS in SSA.

Methods

Approach and Search Strategy

We searched both peer-reviewed and gray literature sources for articles published in English between January 1, 1975, and December 31, 2016, on OAs caring for HIV-positive family members in SSA in the following databases: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Social Sciences Citation Index, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Africa-Wide: NiPAD, and relevant WHO websites. Articles were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: conducted in SSA; sampled OA caregivers, aged 50 and older; used community samples; and focused on HIV-related impacts. There were no restrictions on sample size or study design. Articles were excluded if they were not available in English. Identified articles from all sources were imported and duplicates removed. Titles and abstracts were read, and if deemed appropriate, the full article was obtained and coded.

Organizing the Information

Caregivers were defined as adult women or men aged 50+ who are providing care to PLWHA and/or children younger than 18 who may or may not be HIV-positive, but need care because of HIV. Most the articles included in this review had an aspect of caregiver stress/burden, orphan caregiving, or the impacts of caregiving on caregiver health, wellbeing, and finances in the title or abstract.

We used a narrative approach similar to Yee and Schultz’s (2000) review of the empirical care giving literature. The diversity in measures used and the heavy reliance on qualitative research made a meta-analysis inadvisable. Several steps were used in organizing this review. Our first step involved summarizing the studies by constructing a table containing the country, sampling strategies, main topical domain, and the salient findings for each study). We considered organizing the articles by country, decade or other time variable (pre-and-post apartheid in South Africa), but there did not appear to be any substantive differences in the reported findings since the late 1990s when this topic first appears, and instead opted to organize it by country and publication date (see Table 1) for heuristic purposes.

Table 1.

Summary of Sub-Saharan Africa Studies on Older Adults Caregiving for HIV/IADS Family and Friends

| Author | Sample and study design | Situational demand | Coping | Caregiver needs | Health impacts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Context/material capital | Financial capital | Social capital | Cultural and human capital | Health resource/ strains | Health outcomes/ behaviors | |||

| Multiple countries | ||||||||

| Lackey et al., 2011 | Qualitative OA CGs and OVC (N = 256) | Inheritance challenge food security | Prevention training | Vulnerable | ▼ Intergenerational relationships | ▼ Intergenerational life skills | ▲ Opportunity cost | ▼ Physical and mental health |

| Zimmer & Dayton, 2005 | Comparative cross-sectional | OAs in extended household | Vulnerable | ▼ Support | ||||

| Botswana | ||||||||

| Shaibu, 2013 | Qualitative OAs to OVC (N = 12) age = 60–80 | Farm Distance | Spiritualty & resilience | Vulnerable | ▼ Support | Hard accept CG role | ▲ Opportunity cost | ▼ Physical & mental health |

| Bock & Johnson, 2008 | Experimental Women age = 25–49 years (N = 22) & >50 years (N = 17) | OVC discipline | Vulnerable | ▼ Intergenerational life skills | Produce ▼ food | |||

| Thupayagale- Tshweneagae, 2008 | Qualitative grandmothers to OVC (N = 25) | OVC discipline | Blame on witchcraft bad neighbors | Vulnerable | Stigma | Fail to protect family | Financial, physical & relational stress | Disenfranchised grief Sleepa |

| Alpasian & Mabutho, 2005 | Qualitative (N = 7) | Vulnerable | ▼ Support | ▼ Physical & Mental health | ||||

| Lindsey et al., 2003 | Cross sectional (N = 35) | OAs are dislocated | Spiritualty & resilience | Vulnerable | Stigma | Lack knowledge of HIV/AIDS | Financial, physical, & relational stress | ▼ Mental health. Fasting of food |

| Drah, 2014 | Qualitative (N = 49) | OAs have assets/lack mobility | Spiritualty & resilience | Vulnerable multiple job | Financial, physical stress | ▼ Physical ▲Stress overworkeda | ||

| Mwinituo & Mill, 2006 | Qualitative (N = 15) | Disrespect by doctors | Vulnerable | ▼ Support high stigma | Hide care work | ▼ Physical & mental health | ||

| Kenya | ||||||||

| Chepngeno- Langat, 2014 | Longitudinal (N = 1,322) | Number of OA CGs ▲ annually by 3% | Saving ▲ likelihood of CG | Age & health ▲ likelihood of CG | Serial CG | ▼ Physical & mental health | ||

| Chepngeno- Langat & Evandrou, 2013 | Longitudinal (N = 1,489) | Non-CGs older OAs Lack mobility | Age & health ▲ likelihood of CG | Serial CG | For non-CGs ▼ physical & mental health | |||

| Ice, Sadruddin, Vagedes, Yogo, & Juma, 2012 | Cross sectional Luo CGs age = 60+ (N = 40) | Mostly female CGs | Women ▲ stress than men, Male CGs ▼ stress | Stress | For women, stress ▲ CG & CG intensity but not number of OVC | |||

| Ice et al., 2011 | Longitudinal age 60+ (N = 689) | Food Security | Vulnerable | Social support → BMI | Age ▼ Nutrition | CG → anthropometric measures | Stress negative → anthropometric measures | |

| Chepngeno- Langat, Madise, Evandrou, & Falkingham, 2011 | Cross-sectional N = 1,529) | HIV-CGs were younger | Vulnerable | Gender | Female AIDS CGs have ▲ disability & mobility, male CGs ▼ physical health than non-male CGs | |||

| Chepngeno- Langat & Falkingham, et al., 2010 | Cross-sectional (N = 1,587) | Most CGs were male | HIV-CGs wealthier than non-CGs | HIV-CGs younger, ▼ schooling & married | Male CGs longer care than female CGs who provide critical care | |||

| Skovdal, 2010 | Qualitative OA guardians (N = 36), OVC (N = 69) | Bidirectional care between OA & OVC | Vulnerable | OVC are cared for & provide care for OA-CGs | ||||

| Muga & Onyango-Ouma, 2009 | Qualitative/cross sectional (N = 115) | Climate change/increased dependency ratio | Vulnerable | ▼ Support | Intergenerational relationships | Food security | ||

| Wangui, 2009 | Qualitative 60+ (N = 30) | ▲ Nutritional status, increase land assets | Hired out or gave land to sons | OAs depend on remittances | ▼ Support | ▲ Nutritional OAs Cared for 2-3 OVC | Labor shortage and poor health limited land use | |

| Ice, Zidron, & Juma, 2008 | Cross-sectional mean age 73, (N = 287) | Vulnerable | Social support → pain | Age → SF-36 score and health | Grants → low pain, better mental health | Female CGs ▲ health than non-CGs, Male CGs ▼ than non-CG | ||

| Oburu, 2005 | Cross sectional mothers (N = 115) & OAs (N = 134) | Limited food crop | Age → OVC emotional adjustment score | ▼ Energy, insufficient labor, | OA CGs ▲ stress than biological mothers, stress not → OVC adjustment | |||

| Winters et al., 2005 | Cross-sectional (N = 103) | No → blood glucose & depression | ||||||

| Juma et al., 2004 | Qualitative (N = 84), | Food Security/poor housing, OVC Discipline | Small–scaled farming, pension, loans, spiritualty | Vulnerable | Lack knowledge of HIV/AIDS & care skills | ▲ Opportunity cost. Financial, emotional, and nursing care | ▼ Physical & Mental health Satisfaction for care role | |

| Oburu & Palmérus, 2003 | Cross-sectional (N = 249) | Non-literate CGs use coercive discipline | OVCs age & assertive discipline → Total stress | |||||

| Nyambedha et al., 2003 | Qualitative households (N = 1,100) | OVC discipline, Inheritance rights | Used paid labor, small businesses | Vulnerable | ▼ Social support, High social stigma | Tradition of care | ▲ Opportunity cost | Skipped meals & missed sleep to nurse infantsa |

| Lesotho | ||||||||

| Makoae, 2011 | Qualitative CGs (N = 21) | High HIV prevalence do not know CR HIV statue | Maintain ritual of feeding | CR food intake linked to CG wellbeing | ||||

| Littrell et al., 2012 | Mixed methods (N = 1,281) | Vulnerable | ▼ Social support | Aged CGs more stable than younger CGs | Must provide financial, emotional and nursing care | OA CGs ▼Physical health & Mental health same for both | ||

| Malawi | ||||||||

| Sefasi, 2010 | Qualitative (N = 116) | Resource depletion | Vulnerable | Knowledge of HIV/ AIDS & care skills | Financial, emotional, & nursing care | |||

| Nigeria | ||||||||

| Apata et al., 2010 | Panel (N = 240) | 21% of all OVC loss parents to AIDS | Selling assets | Vulnerable | ▼ Mental health | |||

| South Africa | ||||||||

| Sidloyi & Bomela, 2016 | Qualitative retired women 60+ (N = 15) | Premarital pregnancies, Crime | Loans, friend-ship based networks, small businesses | OAs Casual work, child labor | Social network | |||

| Nyirenda et al., 2015 | Cross-sectional CGs and non-CGs age 50+ (N = 422) | Vulnerable | Household wealth related to wellbeing | ▲ Alcohol use AIDS death related to OA poor physical health | ||||

| Dolbin- Magnab, Jarrott, O'Hora, Vrugt, & Erasmus, 2015 | Qualitative OA women (N = 75) | Spirituality, loans, OVC grants Social network | OAs Access instrumental support | ▲ Social network | HIV+ OAs ▲ Health than HIV affected OAs | |||

| Chazan, 2014 | Qualitative OA women (N = 100) | ▼ Social Support Group | OAs enjoyed, & had hope for OVC | |||||

| Kidman & Thurman, 2014 | Longitudinal (N = 726) | Dependency ratio 1:6,Female CGs, Food insecurity | Vulnerable | ▼ Physical & Mental health | ||||

| Schatz & Gilbert, 2014 | Qualitative Women, aged 60+, (N = 30) | Gendered work/roles | Stigma | CG-Burden | ||||

| Bachman- DeSilva et al., 2013 | Longitudinal (N = 4,030) | 75% Households had grants, Food insecurity | Vulnerable | ▼ Physical & Mental health | ||||

| Casale & Wild, 2013 | Qualitative | CGs care for average 2.7 OVC, OVC discipline & crime | Vulnerable | ▼ Support | ||||

| Govender et al, 2012 | Longitudinal (N = 616) | Vulnerable | ▼ Support | HIV Wealth depletion | ▼ Physical & Mental health | |||

| Schatz & Gilbert, 2012 | Qualitative women age 60–75, (N = 30) | Lacking piped water,electricity, climate, OVCdiscipline | Spirituality, traditional medicines | Vulnerable | ▼ Physical & Mental health | |||

| Petros, 2012 | Cross-sectional OAs in South Africa, (N = 305) | Lacking piped water,electricity, Sanitation, bidirectional care | Vulnerable | Rely on informal support | CG-Fair wellbeing, untreated physical & mental illness | |||

| Tamasane & Head, 2012 | Cross-sectional (N = 5,254) | 1/3rd of children in Kopanong are OVC | Vulnerable | State gate keepers for child grant | Child grants are difficult | CG-rated health as Fair | ||

| Petros, 2011 | Policy OAs | Lacked basic services | Vulnerable | CG stigma | Care under extreme deprivation | ▼ Physical Health | ||

| Casale, 2011 | Qualitative older adults | Adversity, resilience, hire out help | Vulnerable child grants are difficult to get | ▼ Support | Traditional healer | ▲ Joy, focus & hope for OVC | ||

| Kruger et al., 2011 | Cross-sectional rural OAs (N = 134) & urban OAs age = 60+ (N = 196) | Pension main source of income | Age | Health of HIV affected OVC is compromised | Rural OAs had ▲ micronutrient & trace element intake, urban ▲ fat | |||

| Ogunmefun et al., 2011 | Qualitative 50–75 age (N = 60) | CG secrecy | Verbal & Social stigma | Marginal diets | ||||

| Schatz et al., 2011 | Qualitative Women (N = 21) | Estrange/disconnected households | Vulnerable | ▼ Social Support | ▲ Social isolation Depression | |||

| Ardington et al., 2010 | Panel data Age 60+, (N = 7,127) | No difference in expenditure pattern CG & non-CG | Pension mitigate consequences of HIV/AIDS | No impact of death of Adult child | CG-Burden & CG-Stress | |||

| Boon, James, et al., 2010 | Cross-sectional (N = 409) | Female care for average of 4.65 OVC | Income → negative attitude | Communicate with OVC | Expenditure had no impact on Mental &Physical Health | |||

| Boon, Ruiter, et al., 2010 | Longitudinal isiXhosa (N = 820) | 21% of Adult children unemployed, 4.8% of the adult children are HIV+, OAs care for a average of 4.6 OVC | Vulnerable | ▼ Social Support | Intervention | Program ▲ CG ability to relax | ||

| Raniga & Simpson, 2010 | Qualitative OA (N = 15) | Pension stabilized family | Spirituality | ▲ Social supports | Adult death ▼ income | ▼ Physical & Mental health | ||

| Munthree & Maharaj, 2010 | Mixed methods men & women (N = 974) | 25% of CGs care > 3 OVC, Females are primary CGs | Vulnerable | Adult death ▼ income | CG-burden/exhaustion | |||

| Boon et al., 2009 | Cross-sectional isiXhosa speaking CGs (N=202) | 50% of OAs have no income & care for 4.97 OVC | Vulnerable | Completion ▲ attitudes for PLWHA | Completion ▲ CG attitudes, norms & care | ▼ Physical & Mental health | ||

| Hlabyago & Ogunbanjo, 2009 | Qualitative age 50+ (N = 9) | OVC discipline | Vulnerable | ▼ Support social & services | CG painful | Mental & physical health/fear risk for HIV | ||

| Nyasni, Sterberg, & Smith, 2009 | Qualitative age 50+, (N = 45) | OVC discipline | Vulnerable | ▼ Support social | Emotional support to OVC | Intergenerational Disharmony | CG burden/Physical health | |

| Hosegood, Preston, Busza, Moitse, & Timaeus, 2007 | Qualitative CG age 50+ and OVC 15+ (N = 12) | OA men were more likely to be married/OA lived in extended families | Vulnerable | AIDS death 20% of household | Adult death ▼ income | Mental Health | ||

| Schatz, 2007 | Qualitative OAs age >59 (N = 30) | OA lived in extended families | Vulnerable | ▼ Family support | Provide emotional support to OVC | Adult death ▼ income | ||

| Hosegood, & Timaeus, 2006 | Cross-sectional (N=10,612) | 50% of household experience a death of prime-age adult | Vulnerable | Stigma & isolation | OA care expected | Adult death ▼ income | ||

| Ogunmefun & Schatz, 2009 | Cross-sectional female CGs (N = 60) | OA women are becoming CGs | Invested in insurance/credit | HIV households vulnerable | Extended family supported | OAs pay for all care to PLWHA | ||

| Reddy, James, Esu-Williams, & Fisher, 2005 | Qualitative (N = 89) | Pensions are used for household needs, OVC discipline | Vulnerable | Community social support | Must carry out multiple parenting roles | CG is emotionally & physically demanding | ||

| Tanzania | ||||||||

| de Klerk, 2011 | Qualitative OA caregivers | Data collected before roll-out of antiretroviral therapy | CRs are hidden to keep social support | Concealment means good parenting & loving care | ▲ Mental health | |||

| Dayton & Ainsworth, 2004 | Cross-sectional Age = 50+ (N = 757) | OA are not mobile in households Death of prime- age adult → presence of OAs | Healthy household 2× ▲ gainful activity rates, | 42% of deaths were among prime-age adult | Prime-age adult death → ▲ BMI | |||

| Ainsworth & Dayton, 2003 | Cross-sectional Age = 50+ (N = 1512) | 56% of OAs have no durable assets, 67% of deaths attributed to AIDS | Vulnerable Adult death ▼ income | BMI ▲ women than men | 42% of deaths were among prime-age adult | Household wealth ▲ BMI for OAs OVC in household ▼ → BMI | ||

| Togo | ||||||||

| Moore, 2007 | Qualitative age = 50+, (N = 7) | Emotional coping, sought professional help | Adult death ▼ income | Adult death ▼ social support | OAs felt too old for CG | OAs pay for all care to PLWHA & OVC | Accepting death of adult child, CG burden for OVC | |

| Moore & Henry, 2005 | Mixed Method OAs (N = 50) | Condoms, stopping sexual activity, monogamy | Vulnerable Adult death ▼ income | ▼ social support & isolation | Do not believe HIV care is risky | Need affordable drugs &foods | CG burden for OVC | |

| Uganda | ||||||||

| Rutakumwa et al., 2015 | Qualitative OAs (N = 40) dyads | Subsistence food production | Vulnerable | ▼Social support | Financial, physical & relational stress | ▼ Physical & Mental health &bidirectional CG | ||

| Seruwagi, 2014 | Qualitative (N = 129) | Bidirectional caregiving between CGs and OVC | OAs support early marriage | OAs provide instrumental s upport for education | ▼ Physical & Mental health &bidirectional CG | |||

| Kasedde et al., 2014 | Qualitative OA (N = 61) | Reciprocity Cultural intergenerational exchange | Preparing OVC for OA’s death | Vulnerable | ▼ social support & Stigma | Use of traditional medicine | Timing of CG Financial & relational stress | |

| Mugisha et al., 2013 | Cross-sectional, (N = 510) | CG work → financial & physical support | Women → financial support than men | Women care for OVC & provide → care than men | CG work, poverty, poor health HIV → CG burden | |||

| Kamya & Poindexter, 2009 | Qualitative OA CGs (N = 11) | HIV/AIDS deaths, war and famine | Spirituality/inner resiliency | Vulnerable | Logistics of care & money | Stress, fear & poverty | ||

| Nankwango, Neema, & Phillips, 2009 | Qualitative (N=215) | 58% of population has lost someone to AIDS | Social support, professional help, faith | ▼ social support & Stigma | Lack of education about HIV | Burden of OVC care is on rural OAs | ||

| Ssengonzi, 2009 | Qualitative (N = 27) | PLWHA’s finances → OA CG | ▼ social support & Stigma | Women provide care mostly spouse | ▼ Physical & Mental health | |||

| Ssengonzi, 2007 | Qualitative N = 20, | Food insecurity | Food cultivation | Vulnerable | ▼ social support & Stigma | Women provide care mostly spouse | Financial, physical & relational stress | ▼ Physical & Mental health |

| Kakooza & Kimuna, 2005 | Cross-sectional OA, age 50+ (N = 300) | Vulnerable | ▼ social support & Stigma | Financial, physical & relational stress | ▼ Physical & Mental health Balance dieta | |||

| Zimbabwe | ▼ Physical & Mental health | |||||||

| Zvinavashe, Mukombwe, Mulkona, & Haruzivishe, 2015 | Qualitative OVC- CGs (N = 30) | In adequate housing | Seek help from donations, sold surplus goods | Vulnerable | ▼ social support | No physical & Mental health problems | ||

| Mhaka- Mutepfa et al., 2015 | Cross-sectional Mean = 62.4 (N = 327) | Most have access to care Material capital not → ASLb score | Social support → ASL score | Age → with resilience & ASL | Urban OAs, physical & Mental health → ASL | |||

| Skovdal et al., 2011 | Qualitative Nurses (N = 25) OAs, (N = 8) | Food needs are being met via NGOsc Lack of transportation | Vulnerable | ▼ social support | Poor health literacy | Financial, physical & care stress | ▼ Physical & Mental health | |

| Mudavanhu, Segalo, & Fourie, 2008 | Qualitative Age = 50 + 6 (N = 12) | Climate instability Food insecurity | Seek help from donations, grants | Vulnerable | Financial, physical & care stress | ▼ Physical & Mental health | ||

| Agyarko et al., 2002 | Food insecurity, Community violence | Vulnerable | Stigma | Fear of contracting HIV | Financial, physical & care stress | ▼ Physical & Mental health | ||

| Bindura- Mutangandura, 2001 | Qualitative mean 50+ (N = 20) | Resource reallocation join burial societies | Adult child death ▼ Vulnerable | Adult child death ▼ social support | Financial, physical & care stress | ▼ Physical & Mental health | ||

| Mupedziswa, 1997 | Policy study | Climate instability Food Insecurity Foreign debt | Use pension | Vulnerable | Adult child death ▼ social support | Need for healthcare, food, and shelter | ||

Note: BMI = Body mass index; CG = caregiver; CR = care-recipient; OA = older adult(s); OVC = orphan and vulnerable children; PLWHA = person(s) living with HIV/AIDS.

aHealth behavior. bAcceptance of self and life events. cNongovernmental organization.

We grouped these items into the categories defined by our theoretical model to illustrate the importance of cultural resources on informal caregiving. Finally, where appropriate, we noted examples of health outcomes across the three broad domains of health resource strains, health behaviors, and health outcomes.

Results

A total of 122 articles were identified from the databases, out of which a total of 81 met all the selection criteria and were used in the study. Articles were excluded because the topic did not include caregivers (n = 17), the caregiver was too young (n = 9), the study was not based in SSA (n = 11), or did not meet other criteria (n = 3). Out of the 81 reviewed articles, most were situated in South Africa (n = 31), followed by Kenya (n = 16), and Uganda (n = 9), Zimbabwe (n = 7), with the remaining studies in Botswana (n = 5), Ghana (n = 2), Lesotho (n = 1), Malawi (n = 2), Nigeria (n = 1), Tanzania (n = 3), and Togo (n = 2). Two cross-sectional studies on OA caregivers examined five or more countries at once. The articles described a variety of methods to collect data including, qualitative data collection (44%), cross-sectional and longitudinal quantitative studies (51%), and mixed-methods research studies (5%).

Situational Demands

The deaths of prime-age adults have altered household composition and access to resources (Adamchak, Wilson, Nyanguru, & Hampson, 1991; Agyarko, Madzingira, Mupedziswa, Mujuru, & Kanyowa, 2002; Ainsworth & Dayton, 2003; Cohen & Menken, 2006). The articles detailed the poor infrastructure, such as the lack hospitals, medications, access to land, irrigation and modern farming techniques, food distribution, and transportation, as well as widespread unemployment, food insecurity, and climate change. This impacts OA caregivers’ ability to provide safe and effective care to PLWHA and to OVC (Ainsworth & Dayton, 2003; Juma, Okeyo, & Kidenda, 2004; Muga & Onyango-Ouma, 2009). For example, in Tanzania, early publications reported that social safety nets were compromised (Kaijage, 1997), hospitals were overwhelmed (Uys & Cameron, 2003), and food insecurity was commonplace (United Republic of Tanzania, 2006). Recent reports from Tanzania suggest that little has changed. HIV-related stigma and discrimination, stress, and care burden continue to challenge resources for caregiving (de Klerk, 2011; Pallangyo & Mayers, 2009).

AIDS-related deaths have resulted in the creation of 12-million orphans who have largely been absorbed into extended family networks comprised of OAs (Hlabyago & Ogunbanjo, 2009). In most countries in SSA, the extended family, primarily grandparents, care for a large number of OVC (HelpAge International, 2008; Monasch & Boerma, 2004). In national household surveys conducted in 40 countries, only 13 of the countries included information on OA caregivers (Monasch & Boerma, 2004). In those 13 countries, between 24% and 64% of OAs were fostering OVC affected by HIV/AIDS. In Malawi, OAs cared for nearly half (46%) of orphans who have lost both parents. Despite the relatively low prevalence of HIV/AIDS in Kenya, the percentage of OAs providing care increased from 11% in 2006 to 14% by 2014 (Chepngeno-Langat, 2014). In Namibia, the proportion of orphans being cared for by grandparents rose from 44% in 1992 to 61% in 2000 (UNICEF, 2003). In Zimbabwe, South Africa, and Namibia, 60% of AIDS orphans lived with OA caregivers (Zimmer & Dayton, 2005).

Caregiving for OVC has some positive aspects. In Kenya, OVC in the household was associated with better health outcomes for men (Ice, Juma, & Yogo, 2008). In Botswana, a country with the second highest prevalence of HIV/AIDS in the world (17.6%), both children and OAs provide bidirectional care (Lindsey, Hirschfeld, Tiou, & Neube, 2003). Similar patterns of bidirectional care were reported in Kenya and South Africa (Petros, 2011, 2012; Skovdal, 2010). Often, OAs are receiving care for non-HIV or HIV-related health issues or personal care (Nyirenda, Evandrou, Mutevedzi, Hosegood, & Falkingham, 2015). In SSA, OVC often do necessary chores, such as hauling water, tending animals, and so on, which helps both to fill in the labor gap caused by parental death and helps the grandparent’s household economy (Sidloyi & Bomela, 2016; Skovdal, 2010). This care work by OVC is not purely instrumental. In Uganda, the care work for OA caregivers was described as compassionate, highly desired, and loving (Rutakumwa et al. 2015; Seruwagi 2014).

Food insecurity, reported in most of the reviewed articles, is perhaps one of the most unanticipated effects of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. This stems in part from the loss of working age adults, access to land, inheritance laws, and an overall of loss of productivity due to poverty (Agyarko et al., 2002; Mwanyangala, Mayombana, & Urassa, 2010; Pallangyo & Mayers, 2009), time spent caregiving, lack of knowledge of modern farming techniques, increased household size, aging, and chronic health problems (Nyirenda et al., 2015; Oburu, 2005; Wangui, 2009). OAs who cared for very young children seem to be particularly burdened (Shaibu, 2013).

In summary, the HIV/AIDS literature has largely focused on the impacts of caring for OVC rather than OAs caring for both adult children and grandchildren. Research is needed on the influence of HIV-related caregiving responsibilities versus other types of informal care and how care recipients are affected when an established caregiver experiences a decline in health or functional status.

Caregiver Needs

Caregiver needs reflect the range of resources required for support. Included is the availability of resources that directly impact caregiver performance in assistance with activities of daily living (ADL), and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), such as the access to financial capital, social support (social capital), and caregiving know how (cultural capital).

Financial Capital

The main source of income for caregivers varied by country. In South Africa, the majority of OAs depend on the old-age pensions and cottage industries, e.g., selling fruit, milling grain, or providing other nondurable goods and services (Bachman-DeSilva et al., 2013). The impact of public transfers are considerable; a Cape Town study found no differences in expenditure patterns between households with orphans, AIDS-related deaths, and other OA households (Ardington et al., 2010). Household subsidies did initially promote stabilization of households in SSA (Raniga & Simpson, 2010). However, the subsidies were not enough and subsequent studies reported that OAs were financially worse off after providing care to a family member with HIV (Bachman-DeSilva et al., 2013; Casale, 2015; Casale & Wild, 2013; Cohen et al., 2015; Kidman & Thurman, 2014).

Many SSA countries do not have broad pension coverage, and poverty consistently impinges on cultural resources throughout the region. Reasons for economic insecurity center around six recurring themes. First, caregiving duties prevented engaging in income-generating activities (Chazan, 2008; Juma et al., 2004; Shaibu, 2013), and second, there were fewer family members available to farm and tend cattle (Lindsey et al., 2003; Wangui, 2009). Third, repeated bouts of caregiving depleted household resources (Chepngeno-Langat, 2014), often resulting in the fourth problem, poor health. Fifth, what few government grants exist are often inconsistent, insufficient, and nonaccessible (Bachanas et al., 2001; Hlabyago & Ogunbanjo, 2009; Petros, 2012; Tamasane & Head, 2012). Finally, HIV-related caregiving resulted in a lack of support from surviving sons and daughters, as well as inheritance inequalities among male and female family relatives. Thus, there are multiple pathways to poverty among older caregivers.

Social Capital

Despite the large literature on caregiving and PLWHA in high-income countries (HICs; Prachkul & Grant, 2003), most studies only examined instrumental social support and stigma. Several SSA studies reported that OA caregivers continue to experience a shortage of informal supports from family, friends, or neighbors (Alpasian & Mabutho, 2005; Boon, Ruiter, et al., 2010; Nyambedha, 2007; Nyambedha, Wandibba, & Aagaard-Hansen, 2003). Most OAs in South Africa (86%) reported that they were solely responsible for providing basic need for dependents (Boon, Ruiter, et al., 2010). In Malawi, only 31% of OAs were dependent on adult children for help (Sefasi, 2010). In Kenya, social support was linked to increased pain and higher BMI scores (Ice, Heh, Yogo, & Juma, 2011; Ice et al., 2008; Wangui, 2009).

Instrumental support from nonfamily sources was equally strained. Several studies reported that OA caregivers were not treated with respect by governmental official and by hospital staff, including doctors (Hlabyago & Ogunbanjo, 2009; Mwinituo & Mill, 2006; Tamasane & Head, 2012).

OA caregivers experienced many forms of stigma. In Botswana, OAs reported a sense of loneliness and isolation and that stigma was experienced by both caregivers for PLWHA and other chronic diseases (Lindsey et al., 2003). Caregivers in South Africa reported verbal, voyeuristic, and physical stigma (Hosegood & Timaeus, 2006; Lindsey et al., 2003; Ogunmefun, Gilbert, & Schatz, 2011). In Ghana, OA caregivers go to great lengths to hide the HIV status of care recipients as well as their caregiving activities, resulting in isolation of both the PLWHA and the caregiver (Mwinituo & Mill, 2006).

Coping Strategies

Studies of coping mainly addressed financial strategies and religious/spiritual strategies. OA caregivers coped with financial strain by using their knowledge and social networks to access old-age and foster-care grants, as well as their saving accounts (Ardington et al., 2010). In Kenya, OA caregivers engaged in small-scale farming and the selling of assets to meet the ongoing care needs of PLWHA and funeral costs (Wangui, 2009). There is some evidence that OAs in South Africa use a revolving pool of microcredit as a source of income (Lackey, Clacherty, Martin, & Hillier, 2011; Ogunmefun & Schatz, 2009; Schatz & Ogunmefun, 2007). Additional coping strategies included: applying for food grants, carefully managing income, investing in funeral insurance and credit programs, and creating associations to form social support networks (Casale, 2011; Chazan, 2008, 2014; Juma et al., 2004).

Several studies reported the use of spirituality as a coping mechanism (Drah, 2014; Shaibu, 2013). In South Africa, caregivers reported talking to their pastor, congregants, and praying to God (Chazan, 2008). Alternately, silence and concealment of AIDS illness was a coping mechanism identified in South Africa to protect and honor individuals affected by HIV/AIDS (de Klerk, 2011).

Health Impacts

Health Resource Strains

There are several unusual characteristics of HIV-related caregiving in SSA. The first is serial caregiving—many OAs care for one adult child, and then another—either concurrently or sequentially, as well as their offspring. In Kenya, 10% of noncaregiving OAs in a household transitioned into caregiving and 50% of these caregivers were providing care transitioned to noncaregiving status (Chepngeno-Langat & Evandrou, 2013). A second feature is the number of care-recipients, which are generally not analyzed with regard to caregiver health outcomes or asset dissolution. Caregiving is associated with high opportunity costs where OAs must forgo gainful opportunities to provide care (Nyambedha, Wandibba, & Aagaard-Hansen, 2001).

Health Behaviors

Health behaviors were only examined by two studies. In the first, OA caregivers reported foregoing meals, restricting their food intake, or working extra jobs to purchase the care-recipient’s preferred food (Kruger, Lekalakalamokgela, & Wentzel-Viljoen, 2011). The second study found that alcohol abuse was problematic for OA caregivers in South Africa (Sidloyi & Bomela, 2016).

Health Outcomes

Grandparents are grieving both for their adult children and report stress in caregiving for grandchildren. In Botswana, OAs had “disenfranchised” grief: they had to hide their own pain of losing adult children because they had to serve as a source of strength to the surviving grandchildren (Thupayagale-Tshweneagae, 2008). Grandmother caregivers in Botswana, Togo, and Uganda reported that they felt depressed and isolated, with a loss of control when grandchildren were unruly and disrespectful (Kamya & Poindexter, 2009; Moore, 2007; Thupayagale-Tshweneagae, 2008). Over half (57%) of Kenyan caregivers reported a poor quality of life and 74% reported that caregiving had a large impact on their lives (Lindsey et al., 2003). Kenyan caregivers of HIV-positive kin had poorer self-reported health compared to other types of caregivers. Men reported worse health than women and new caregivers were more likely to report having a major health problem compared with those who had never provided care (Chepngeno-Langat, 2014). Thus, the majority of the studies find impaired mental and physical health among caregivers, perhaps due to their greater poverty and age.

Discussion

The literature on OA caregiving in SSA is fragmented across several disciplines. Despite the more robust literature on HIV-related caregiving in HICs, much less is known about OA caregivers providing HIV-related care to adult children and grandchildren in SSA. This is important because, in many ways, the situation in SSA presages a dilemma that HICs will be facing in the next few decades—namely, many OAs will be requiring care and there will be too few caregivers (AARP, 2013a, 2013b).

We found that OA caregivers in SSA face a range of challenges that can be framed by the sociohistorical context of population aging and AIDS. Further, our adapted cultural resources model emphasizes the collective nature of both the stressors and adaptive strategies. Most of the articles reviewed focused on material and economic resources, with comparatively fewer about psychosocial resources such as nonfinancial social support and coping in the SSA context. Although access to “public goods” is critical to caregiver wellbeing, it does little to address contextual factors such as, inheritance rights, intergenerational conflict, HIV-stigma, and rising dependency ratios (Lackey et al., 2011; Ralston, 2017). Another topic not addressed in the reviewed literature was related to the development of post-colonial migrant labor patterns (Camlin et al., 2010). However, the relationship between migration and AIDS is complex, and most individuals move to urban centers for economic benefits. Whether this applies to OA caregivers is unknown.

Our multileveled model allows for the capturing of the social-cultural context of caregiving in SSA (population aging and HIV/AIDS pandemic). Studies reviewed consistently reported resource constraints that framed the situational demands of care including: lack of material capital (safe housing, roads, and transportation); lack of inheritance rights; and lack of food security (Ice et al., 2011; Lackey et al., 2011). These stressors were further augmented by the necessity of needing to care for multiple family members, either serially or at the same time (Chepngeno-Langat, 2014; Zimmer et al., 2005).

A significant finding was that the bidirectionality of caregiving was often emphasized. Grandchildren were not only the recipients of care, but they also provided much needed household and farm labor which enhanced their grandparents’ ability to provide care (Kasedde et al., 2014; Petros, 2012; Skovdal, 2010). The care by OVC was not purely instrumental (e.g., running chores). OAs draw strength from their OVC and attach a great deal of importance to the quality of their relationships (Seruwagi, 2014).

Third, at the individual level, the use of cultural resources was linked to a range of coping strategies, such as religious/spiritual coping, which is a very important resource. However, the collective nature of some of the coping strategies allowed for leveraging in resource-poor environments. Villagers reported communal strategies for financial and nutritional shortfalls, as well as for accessing often-distant medical care and meet cultural demand of funeral costs (Njororai & Njororai, 2013).

The relationship between caregiving and caregiver physical wellbeing was more complex. Several studies reported poor health outcomes, but a few studies reporting positive health outcomes. Some of this may be due reverse causality—younger and healthier individuals may take up caregiving duties. However, there is some evidence that having a purpose in life may prove beneficial for older caregiver’s health (Casale, 2015). The SSA grandparents are often literally the only factor preventing complete destitution of their households, which provides a powerful incentive for maintaining functional health.

Despite the resource-poor environment in SSA, many OA caregivers nonetheless exhibited resilience. They drew on their religious/spirituality, their sense of purpose, and their embeddedness in the communities. Despite social stigma, they often utilized collective strategies. Finally, this review emphasized the importance of OAs—in holding together their families and cultures in the face of an overwhelming pandemic and economic pressures.

Conclusion and Future Directions

The current body of evidence uncovered in this literature review partially supports our adapted conceptual model. This model allows for an integrated understanding of the stress and coping processes stemming from the wider cultural context. By identifying cultural resources and the collective nature of coping and adaptation in a resource-poor environment, our model provides a framework for caregiver intervention that is not solely focused on the individual, but recognizes the importance of targeting community-level efforts in interventions.

Bidirectional caregiving is emerging as an important construct (Nagpal, Heid, Zarit, & Whitlatch, 2015). We need more research understanding the dynamic transactions between family members, friends, and the larger community to understand the resources that can be both drawn on and created during stressful situations. Next steps for research in this field should include the identification of processes that fortify existing cultural resources or the development of cultural resources that influence caregiver resilience.

Funding

This study was supported by funds from the National Institute on Aging Diversity Supplement NIH/NIA 3R01AG044917-02S1 to Dr J. Small.

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

References

- AARP (2013a). The aging of the baby boom and the growing care gap: A look at future declines in the availability of family caregivers Retrieved November 12, 2016, from http://www.aarp.org/home-family/caregiving/info-08-2013/the-aging-of-the-baby-boom-and-the-growing-care-gap-AARP-ppi-ltc.html

- AARP (2013b). Report: Caregivers in crises Retreived September 1, 2016, from http://states.aarp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Caregivers-in-Crisis-FINAL.pdf

- Adamchak D. J., Wilson A. O., Nyanguru A., & Hampson J (1991). Elderly support and intergenerational transfer in Zimbabwe: An analysis by gender, marital status, and place of residence. The Gerontologist, 4, 505–513. doi:10.1093/geront/31.4.505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agyarko R. D., Madzingira N., Mupedziswa R., Mujuru N., & Kanyowa L (2002). Impact of AIDS on older people in Africa. Zimbabwe case study Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; Retrieved September 11, 2016, from http://www.popline.org/node/245821 - sthash.TNTzEOLk.dpuf [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth M., & Dayton J (2003). The impact of the AIDS epidemic on the health of older persons in northwestern Tanzania. World Development, 3, 131–148. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00150-X [Google Scholar]

- Aldwin C. M. (2007). Stress, coping, and development: An integrative perspective. USA: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aldwin C. M., & Igarashi H (2016). Coping, optimal aging, and resilience in a sociocultural context. In Bengston V. & Settersten R. A. (Eds.), Handbook of the Theories of Aging (pp. 551–576). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Alpasian N. A. H., & Mabutho S. L (2005). Caring for AIDS orphans: The experience of elderly grandmother caregivers and AIDS orphan. Social Work, 3, 276–295. [Google Scholar]

- Apata T. G., Rahji M. A. Y., Apata O. M., Ogunrewo J. O., & Igbalajobi O. A (2010). Effects of HIV/AIDS epidemic and related sicknesses on family and community structures in Nigeria: Evidence of emergence of older care-givers and orphan hoods. Journal of Science and Technology Education Research, 1, 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Aranda M. P., & Knight B (1997). The influence of ethnicity and culture on the caregiver stress and coping process: A sociocultural review and analysis. The Gerontologist, 37, 342–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardington C., Case A., Islam M., Lam D., Leibbrandt M., Menendez A., & Olgiati A (2010). The impact of AIDS on intergenerational support in South Africa: Evidence from the Cape Area Panel Study. Research on Aging, 1, 97–121. doi:10.1177/0164027509348143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AVERT (2015). HIV and AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa regional overview Retrieved August 15, 2016, from http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_Gap_report_en.pdf

- Bachanas P. J., Kullgren K. A., Schwartz K. S., McDaniel J. S., Smith J., & Nesheim S (2001). Psychological adjustment in caregivers of school-age children infected with HIV: stress, coping, and family factors. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 6, 331–342. Print number: 0146-8693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman-DeSilva M., Skalicky A., Beard J., Cakwe M., Zhuwau T., Quinlan T., & Jonathan L. S (2013). Household dynamics and socioeconomic condition in the context of incident adolescent orphaning in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Vulnerable Child Youth Studies, 8, 10. doi:10.1080/17450128.2012.748237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindura-Mutangandura G. (2001). HIV/AIDS, poverty and elderly women in urban Zimbabwe. South African Feminist Review, 4, 93–105. Accession number: SFLNSSAFR1101SEDZ673000007 [Google Scholar]

- Block E. (2014). Flexible kinship: caring for AIDS orphans in rural Lesotho. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 20, 711−727. doi:10.1111/1467-9655.12131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block E. (2016). Reconsidering the orphan problem: The emergence of male caregivers in Lesotho. AIDS Care, 28, (Suppl. 4), 30–40. doi:10.1080/09540121.2016.1195480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock J., & Johnson S. E (2008). Grandmothers’ Productivity and the HIV/AIDS Pandemic in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 23, 131–145. doi:10.1007/s10823-007-9054-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boon H., James S., Ruiter R. A. C., van den Borne B., Williams E., & Reddy P (2010). Explaining perceived ability among older people to provide care as a result of HIV and AIDS in South Africa. AIDS Care, 22, 399–408. doi:10.1080/09540120903202921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boon H., Ruiter R. A. C., James S., van den Borne B., Williams E., & Reddy P (2009). The impact of a community-based pilot health education intervention for older people as caregivers of orphaned and sick children as a result of HIV and AIDS in South Africa. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 24, 373–389. doi:10.1007/s10823-009-9101-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boon H., Ruiter R. A. C., James S., van den Borne B., Williams E., & Reddy P (2010). Correlates of grief among older adults caring for children and grandchildren as a consequence of HIV and AIDS in South Africa. Journal of Aging and Health, 22, 48–67. doi:10.1177/0898264309349165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. (1986). The forms of capital. In Richardson J. G. (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). New York: Greenwood. [Google Scholar]

- Camlin C.S., Hosegood V., Newell M-L., McGrath N., Ba ¨rnighausen T., Snow R (2010)Gender, migration and HIV in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. PLoS ONE, 7, e11539. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casale M. (2011). ‘I am living a peaceful life with my grandchildren. Nothing else.’ Stories of adversity and ‘resilience’ of older women caring for children in the context of HIV/AIDS and other stressors. Ageing and Society, 31, 1265–1288. doi:10.1017/S0144686X10001303 [Google Scholar]

- Casale M. (2015). The importance of family and community support for the health of HIV-affected populations in Southern Africa: What do we know and where to from here?British Journal of Health Psychology, 20, 21–35. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casale M., & Wild L (2013). Effects and processes linking social support to caregiver health among HIV/AIDS-affected carer-child dyads: A critical review of the empirical evidence. AIDS Behavior, 17, 1591–1611. doi:10.1007/s10461-012-0275-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chazan M. (2008). Seven ‘deadly’ assumptions: Unravelling the implications of HIV/AIDS among grandmothers in South Africa and beyond. Ageing and Society, 28, 935–958. doi:10.1017/S0144686X08007265 [Google Scholar]

- Chazan M. (2014). Everyday mobilisations among grandmothers in South Africa: Survival, support and social change in the era of HIV/AIDS. Ageing and Society, 34, 1641–1665. doi:10.1017/S0144686X13000317 [Google Scholar]

- Chepngeno-Langat G. (2014). Entry and re-entry into informal care-giving over a 3-year prospective study among older people in Nairobi slums, Kenya. Health and Social Care in the Community, 22, 533–544. doi:10.1111/hsc.12114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chepngeno-Langat G., & Evandrou M (2013). Transitions in caregiving and health dynamics of caregivers for people with AIDS: A Prospective study of caregivers in Nairobi slums, Kenya. Journal of Aging and Health, 25, 678–700. doi:10.1177/0898264313488164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chepngeno-Langat G., Falkingham J., Madise N. J., & Evandrou M (2010). Socioeconomic differentials between HIV caregivers and noncaregivers: Is there a selection effect? A case of older people living in Nairobi City slums. Research on Aging, 32, 67–96. doi:10.1177/0164027509348116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chepngeno-Langat G., Madise N., Evandrou M., & Falkingham J (2011). Gender differentials on the health consequences of care-giving to people with AIDS-related illness among older informal carers in two slums in Nairobi, Kenya. AIDS Care-Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, 23, 1586–1594. doi:10.1080/09540121.2011.569698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen B., & Menken J (Eds.) (2006). Aging in Sub-Saharan Africa: Recommendations for furthering research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; Retrieved September 14, 2016, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11812/?report=printable [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen C. R., Steinfeld R. L., Weke E., Bukusi E. A., Hatcher A. M., Shiboski S., Weiser S. D (2015). Shamba Maisha: Pilot agricultural intervention for food security and HIV health outcomes in Kenya: Design, methods, baseline results and process evaluation of a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Springerplus, 4, 122. doi:10.1186/s40064-015-0886-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayton J., & Ainsworth M (2004). The elderly and AIDS: Coping with the impact of adult death in Tanzania. Social Science and Medicine, 59, 2161–2172. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Klerk J. (2011). The compassion of concealment: Silence between older caregivers and dying patients in the AIDS era, northwest Tanzania. Culture Health and Sexuality, 14, S27–S38. doi:10.1080/13691058.2011.631220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolbin-MacNab M. L., & Yancura L. A (2017). International perspectives on grandparents raising grandchildren. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 1−31. Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/0091415016689565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolbin-Magnab M., Jarrott S., O'Hora K. A., Vrugt C., & Erasmus M (2015). Dumela Mma: An examination of resilience among South African grandmothers raising grandchildren. Aging and Society, 36, 2182–2212. doi:10.1017/S0144X15001014 [Google Scholar]

- Drah B. B. (2014). 'Older women', customary obligations and orphan foster caregiving: The case of queen mothers in Manya Klo, Ghana. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 29, 211–229. doi:10.1007/s10823-014-9232-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder G. H., & George L. K (2016). Age, cohorts, and the life course. In Shanahan M. J. & Mortimer J. T. (Eds.), Handbook of the Life Course. Vol. II (pp. 59–85). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Galama T. J. (2015). A Contribution to Health-Capital Theory. CESR-Schaeffer; Working Paper No. 2015-004. [Google Scholar]

- Govender K., Penning S., George G., & Quinlan T (2012). Weighing up the burden of care on caregivers of orphan children: The Amajuba District Child Health and Wellbeing Project, South Africa. AIDS Care, 24, 712–721. doi:10.1080/09540121.2011.630455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gysels M., Pell C., Straus L., & Pool R (2011). End of life care in sub-Saharan Africa a systematic review of the qualitative literature. BMC Palliative Care, 10, 1–10. doi:10.1186/1472-684X-10-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman J. J. (2007). The economics, technology, and neuroscience of human capability formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104, 13250–13255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HelpAge International (2008). The impact of HIV on older people. Ageways, 71, 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hlabyago K. E., & Ogunbanjo G. A (2009). The experiences of family caregivers concerning their care of HIV/AIDS orphans. South African Family Practice, 51, 506–511. doi:10.1080/20786204.2009.10873915 [Google Scholar]

- Hosegood V., Preston W., Busza J., Moitse S., & Timaeus I. M (2007). Revealing the full extent of households' experiences of HIV and AIDS in rural South Africa. Social Science and Medicine, 65, 1249–1259. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosegood V., & Timaeus I. M (2006). HIV/AIDS and older people in South Africa. In Cohen B. & Merken J. (Eds.), Aging in sub-Sahara Africa: Recommendations for furthering research (pp. 250–275). Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ice G. H., Heh V., Yogo J., & Juma E (2011). Caregiving, gender, and nutritional status in Nyanza Province, Kenya: Grandmothers gain, grandfathers lose. American Journal of Human Biology, 23, 498–508. doi:10.1002/ajhb.21172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ice G. H., Juma E., & Yogo J (2008). The impact of HIV/AIDS on older persons in Africa and Asia. Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan Center on the Demography of Aging; Retrieved June 4, 2016, from http://agingaidsconf.psc.isr.umich.edu/events/hivaidsconf.html [Google Scholar]

- Ice G. H., Sadruddin A. F. A., Vagedes A., Yogo J., & Juma E (2012). Stress associated with caregiving: An examination of the stress process model among Kenyan Luo elders. Social Science and Medicine, 74, 2020–2027. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ice G. H., Zidron A., & Juma E (2008). Health and health perceptions among Kenyan grandparents. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 23, 111–119. doi:10.1007/s10823-008-9063-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juma M., Okeyo T., & Kidenda G (2004). Our hearts are willing, but... Challenges of elderly caregivers in rural Kenya. Horizons Research Update. Nairobi: Population Council. Retrieved June 1, 2016, from http://www.popcouncil.org/uploads/pdfs/horizons/eldrlycrgvrsknyru.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kaijage F. (1997). Rethinking African history: Interdisciplinary perspectives. In McGrath S., Jedrej C., King K., & Thompson J. (Eds.), Rethinking African history. Edinburgh, Scotland: Centre of African Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Kakooza J., & Kimuna S. R (2005). HIV and AIDS orphans' education in Uganda: The changing role of older people. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 3, 63–81. ISSN: 1535-0770, Electronic ISSN: 1535-0932. [Google Scholar]

- Kamya H., & Poindexter C. C (2009). Mama Jaja: The stresses and strengths of HIV-affected Ugandan grandmothers. Social Work in Public Health, 24, 4–21. doi:10.1080/19371910802569294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang'ethe S. (2012). Challenges impacting on the quality of care to persons living with HIV/AIDS and other terminal illnesses with reference to Kanye community home-base care programme. Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 6, 21–32. doi:org/10.1080/17290376.2009.9724926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasedde S., Doyle A. M., Seeley J. A., & Ross D. A (2014). They are not always a burden: Older people and child fostering in Uganda during the HIV epidemic. Social Science and Medicine, 113, 161–168. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidman R., & Thurman T. R (2014). Caregiver burden among adults caring for orphaned children in rural South Africa. Vulnerable Child Youth Studies, 9, 234–246. doi:10.1080/17450128.2013.871379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight B. G., & Sayegh P (2010). Cultural values and caregiving: The updated sociocultural stress and coping model. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65B, 5–13. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbp096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knodel J., Watkins S., & VanLandingham M (2002). AIDS and the older person: An international perspective. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Population Studies Center at the Institute For Social Research: Retrieved November 01, 2016, from http://www.psc.isr.umich.edu/pubs/pdf/rr02-495.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kruger A., Lekalakalamokgela S. E., & Wentzel-Viljoen E (2011). Rural and urban older African caregivers coping with HIV/AIDS are nutritionally compromised. Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics, 30, 274–290. doi:10.1080/01639366.2010.528333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackey D., Clacherty G., Martin P., & Hillier L (2011). Intergenerational issues between older caregivers and children in the context of AIDS in Eastern and Southern Africa. Eastern and Southern Africa: HelpAge International and the Regional Interagency Task Team on Children and AIDS; Retrieved November 01, 2016, from https://mhpss.net/?get=58/1355862147-RIATTIGSreportlowres.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey E., Hirschfeld M., Tiou S., & Neube E (2003). Home-based care in Botswana: Experience of older women and young girls. Healthcare for Women International, 24, 486–501. doi:10.1080/07399330390199384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littrell M., Murphy L., Kumwenda M., & Macintyre K (2012). Gogo care and protection of vunerable children in rural Malawi: Changing responsibilities, capacity to provided, and implications for well-being in the Era of HIV and AIDS. Journal of Cross Cultural Gerontology, 27, 335–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch J. W., Smith G. D., Kaplan G. A., & House J. S (2000). Income inequality and mortality: Importance to health of individual income, psychosocial environment, or material conditions. British Medical Journal, 320, 1200–1204. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7243.1200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makoae M. (2011). Food meanings in HIV and AIDS caregiving trajectories: Ritual, optimism and anguish among caregivers in Lesotho. Psychology Health and Medicine, 16, 190–202. doi:10. 1080/13548506.2010.525656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathambo V., & Gibbs A (2009). Extended family childcare arrangements in a context of AIDS: Collapse or adaptation?AIDS Care, 21 (Suppl. 1), 22–27. doi:10.1080/09540120902942949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhaka-Mutepfa M., Mpofu E., & Cumming R (2015). Impact of protective factors on resilience of grandparent carers fostering orphans and non-orphans in Zimbabwe. Journal of Aging and Health, 27, 454–479. doi:10.1177/0898264314551333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monasch R., & Boerma T (2004). Orphanhood and childcare patterns in sub-Saharan Africa: An analysis of national household survey from 40 countries. AIDS, 18, S55–65. PIMD: 15319744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A. R. (2007). Older poor parents who lost an adult child to AIDS in Togo, West Africa: A qualitative study. Omega (Westport), 56, 289–304. Accession number: 18300652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A. R., & Henry D (2005). Experiences of older informal caregivers to people with HIV/AIDS in Lome, Togo. Ageing International, 30, 147–166. doi:10.1007/s12126-005-1009-8 [Google Scholar]

- Mudavanhu D., Segalo P., & Fourie E (2008). Grandmothers caring for their grandchildren orphaned by HIV and AIDS 4, 76–97 Retrieved November 20, 2016, from http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/unipsyc/unipsyc_v4_n1_a7.pdf

- Muga G. O., & Onyango-Ouma W (2009). Changing household composition and food security among the elderly caretakers in rural western Kenya. Journal of Cross Cultural Gerontology, 24, 259–272. doi:10.1007/s10823-008-9090-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugisha J., Scholten F., Owilla S., Naidoo N., Seeley J., Chatterji S., Boerma T (2013). Caregiving responsibilities and burden among older people by HIV status and other determinants in Uganda. AIDS Care, 25, 1341–1348. doi:10.1080/09540121.2013.765936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munthree C., & Maharaj P (2010). Growing old in the era of a high prevalence of HIV/AIDS: The impact of AIDS on older men and women in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Research on Aging, 32, 155–174. doi:10.1177/0164027510361829 [Google Scholar]

- Mupedziswa R. (1997). AIDS and the older Zimbabweans: Who will care for the carers?Southern African Journal of Gerontology, 6, 9–12. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.21504/sajg.v6i2.114 [Google Scholar]

- Mwanyangala M. A., Mayombana C., & Urassa H (2010). Health status and quality of life among older adults in rural Tanzania. Global Health Action, 3 (Suppl. 2), 36–44. doi:10.3402/gha.v3i0.2142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwinituo P. P., & Mill J. E (2006). Stigma associated with Ghanaian caregivers of AIDS patients. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 28, 369–382. doi:10.1177/0193945906286602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagpal N., Heid A. R., Zarit S. H., & Whitlatch C. J (2015). Religiosity and quality of life: A dyadic perspective of individuals with dementia and their caregivers. Aging and Mental Health, 19, 500–506. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.952708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nankwango A., Neema S., & Phillips J (2009). Exploring and curbing the effects of HIV/AIDS on elderly people in Uganda. Journal of Community and Health Sciences, 2, 19−30. [Google Scholar]

- Njororai F., & Njororai W. W. S (2013). Older adult caregivers to people with HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa: A review of the literature and policy implications for change. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education, 51, 248–266. doi:10.1080/14635240.2012.703389 [Google Scholar]

- Nyambedha E. O. (2007). Practices of relatedness and the re-invention of dual as a network of care for orphans and widows in western Kenya. Africa, 77, 517–535. doi:10.3366/afr.2007.77.4.517 [Google Scholar]

- Nyambedha E. O., Wandibba S., & Aagaard-Hansen J (2001). Policy implications of the inadequate support systems for orphans in western Kenya. Health Policy, 58, 83–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-8510(01)00145-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyambedha E. O., Wandibba S., & Aagaard-Hansen J (2003). "Retirement lost"-the new role of the elderly as caretakers for orphans in Western Kenya. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 18, 33–52. doi:10.1023/A:1024826528476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyasni E., Sterberg E., & Smith H (2009). Fostering children affected by AIDS in Richard Bay, South Africa: A qualitative study of grandparents' experiences. African Journal of AIDS Research, 8, 181–192. doi:10.2989/AFAR2009.8.2.6.858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyirenda M., Evandrou M., Mutevedzi P., Hosegood V., & Falkingham J (2015). Who cares? Implications of care-giving and -receiving by HIV-infected or -affected older people on functional disability and emotional wellbeing. Ageing and Society, 35, 169–202. doi:10.1017/S0144686X13000615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oburu P. O. (2005). Caregiving stress and adjustment problems of Kenyan orphans raised by grandmothers. Infant and Child Development, 14, 199–210. doi:10.1002/icd.388 [Google Scholar]

- Oburu P. O., & Palmérus K (2003). Parenting stress and self-reported discipline strategies of Kenyan caregiving grandmothers. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27, 505–512. doi:10.1080/01650250344000127 [Google Scholar]

- Ogunmefun C., Gilbert L., & Schatz E. J (2011). Older female caregivers and HIV/AIDS-related secondary stigma in rural South Africa. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 26, 85–102. doi:10.1007/s10823-010-9129-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogunmefun C., & Schatz E. J (2009). Caregivers' sacrifices: The opportunity costs of adult morbidity and mortality on female pensioners in rural South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 1, 95–109. doi:10.1080/03768350802640123 [Google Scholar]

- Oppong C. (2006). Familial roles and social transformations: Older men and women in sub-Saharan Africa. Research on Aging, 28, 654–668. doi:10.1177/0164027506291744 [Google Scholar]

- Pallangyo E., & Mayers P (2009). Experiences of informal female caregivers providing care for people living with HIV in dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 20, 481–493. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2009.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. I., Mullan J. T., Semple S. J., & Skaff M. M (1990). Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist, 30, 583–594. doi:10.1093/geront/30.5.583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petros S. G. (2011). Supporting older caregivers to persons affected by HIV and AIDS. Economic and Social Rights in South Africa, 12, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Petros S. G. (2012). Use of a mixed methods approach to investigate the support needs of older caregivers to family members affected by HIV and AIDS in South Africa. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 6, 275–293. doi:10.1177/1558689811425915 [Google Scholar]

- Prachakul W., & Grant J. S (2003). Informal Caregivers of Persons with HIV/AIDS: A Review and Analysis. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 14, 55−71. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1055329003014003005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralston M. (2017). The role of older persons’ environment in aging well: Quality of life, illness, and community context in South Africa. The Gerontologist, 1–10. doi:10.1093/geront/gnx091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raniga T., & Simpson B (2010). Grandmothers bearing the brunt of HIV/AIDS in Bhambayi, Kwa Zulu-Natal, South Africa. The Social Work Practitioner-Researcher, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy S., James S., Esu-Williams E., & Fisher A (2005). Inkala, ixinge etyeni: Trapped in a difficult situation” The burden of care on the elderly in the Eastern Cape, South Africa Johannesburg, South Africa: Population Council, Horizons: Retrieved June 11, 2016, from http://www.popline.org/node/257488 [Google Scholar]

- Rutakumwa R., Zalwango F., Richards E., & Seeley J (2015). Exploring the care relationship between grandparents/older carers and children infected with HIV in south-western Uganda: Implications for care for both the children and their older carers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12, 2120–2134. doi:10.3390/ijerph120202120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz E. J. (2007). "Taking care of my own blood": Older women's relationships to their households in rural South Africa. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 69, 147–154. doi:10.1080/14034950701355676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz E. J., & Gilbert L (2012). “My heart is very painful”: Physical, mental and social wellbeing of older women at the times of HIV/AIDS in rural South Africa. Journal of Aging Studies, 26, 16–25. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2011.05.003 [Google Scholar]

- Schatz E. J., & Gilbert L (2014). "My legs affect me a lot. ... I can no longer walk to the forest to fetch firewood": Challenges related to health and the performance of daily tasks for older women in a high HIV context. Health Care Women Int, 35, 771–788. doi:10.1080/07399332.2014.900064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz E. J., Madhavan S., & Williams J (2011). Female-headed households contending with AIDS-related hardship in rural South Afriica. Health and Place, 17, 598–605. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.12.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz E. J., & Ogunmefun C (2007). Caring and contributing: The role of older women in rural South African multi-generational households in the HIV/AIDS era. World Development, 35, 1390–1403. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.04.004 [Google Scholar]

- Schatz E. J., & Seeley J (2015). Gender, ageing and carework in East and Southern Africa: A review. Global Public Health, 10, 1185–1200. doi:10.1080/17441692.2015.1035664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sefasi A. P. (2010). Impact of HIV and AIDS on the eldery: A case study of Chiladzulu district. Malawi Medical Journal, 22, 101–103. PPMCID: PMC3345771. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seruwagi G. K. (2014). Making sense of intergenerational closeness and distance: The case of grandparent caregivers in Uganda. The International Journal of Aging and Society, 3, 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Shaibu S. (2013). Experiences of grandmothers caring for orphan grandchildren in Botswana. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 45, 363–370. doi:10.1111/jnu.12041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidloyi S. S., & Bomela N. J (2016). Survival strategies of elderly women in Ngangelizwe Township, Mthatha, South Africa: Livelihoods, social networks and income. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 62, 43–52. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2015.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skovdal M. (2010). Children caring for their “caregivers”: Exploring the caring arrangements in households affected by AIDS in Western Kenya. AIDS Care, 22, 96–103. doi:10.1080/09540120903016537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skovdal M., Campbell C., Madanhire C., Nyamukapa C., & Gregson S (2011). Challenges faced by elderly guardians in sustaining the adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected children in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care, 23, 957–964. doi:10.1080/09540121.2010.542298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ssengonzi R. (2007). The plight of older persons as caregivers to people infected/affected by HIV/AIDS: Evidence from Uganda. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 22, 339–353. doi:10.1007/s10823-007-9043-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ssengonzi R. (2009). The impact of HIV/AIDS on the living arrangements and well-being of elderly caregivers in rural Uganda. AIDS Care, 21, 309–314. doi:10.1080/09540120802183461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamasane T., & Head J (2012). The quality of material care provided by grandparents for their orphan grandchildren in the context of HIV/AIDS and poverty: A study of Kopanong municipality, Free State. Journal on the Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 7, 76–84. doi:10.1080/17290376.2010.9724960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thupayagale-Tshweneagae G. (2008). Psychosocial effects experienced by grandmothers as primary caregivers in rural Botswana. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 15, 351–356. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01232.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS (2015). How AIDS changed everything report Retrieved October 4, 2016, from http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2015/MDG6_15years-15lessonsfromtheAIDSresponse

- UNICEF (2003). Africa's orphaned generation. New York: UNICEF: Retrieved November 6, 2016, from http://www.unicef.org/sowc06/pdfs/africas_orphans.pdf [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania (2006). Millennium Development Goals (MDGS) progress report Ministry of Planning, Economy and Empowerment. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: United Nation Development Program: Retrieved October 6, 2016, from www.undp.org/.../MDG/.../MDG%20Country%20Reports/United%20Republic [Google Scholar]

- Uys L., & Cameron S (2003). Home-based HIV/AIDS care. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wangui E. E. (2009). Livelihood strategies and nutritional status of grandparent caregivers of AIDS orphans in Nyando District, Kenya. Qualitative Health Research, 19, 1702–1715. doi:10.1177/1049732309352906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters T. M., Hendrix A. N., Zidron A., McConnell A. N., Escano I. G., Kermode T. T., … Ice G. H (2005). Blood glucose correlations with depression, body habitus and caregiving status in the elderly Kenyan Luo grandparents. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, 105, 28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee J. L., & Schulz R (2000). Gender differences in psychiatric morbidity among family caregivers: A review and analysis. The Gerontologist, 40, 147–164. doi:10.1093/geront/40.2.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer Z., & Dayton J (2005). Older adults in sub-Saharan Africa living with children and grandchildren. Population Studies-A Journal of Demography, 59, 295–312. doi:10.1080/00324720500212255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]