Abstract

Consistent with a holistic perspective emphasizing the integration of multiple individual characteristics within child systems, it was hypothesized that subgroups of anxious solitary (AS) children characterized by agreeableness, behavioral normality, attention-seeking–immaturity, and externalizing behaviors would demonstrate heterogeneity in peer relations and dyadic friendships. Sociometrics were collected for 688 3rd-grade children (mean age = 8.66 years, 51.5% female), and recess observations were obtained for a subset of 163 children. Results revealed that agreeable AS children demonstrated significantly superior relational adaptation relative to other AS children, whereas normative, attention-seeking–immature, and externalizing AS children demonstrated increasing relational adversity. Attention-seeking–immature AS children engaged in particularly high rates of directed solitary behavior and were most ignored by peers. Externalizing AS children were most often victimized by peers. Subgroup differences in sociometric peer adversity were qualified by sex.

Keywords: social withdrawal, shyness, social anxiety, peer relations, victimization, exclusion

Anxious solitary (AS) children—children who desire peer interaction but often play alone among familiar peers because of shyness and social anxiety—may differ from one another substantially in the quality of their relations with peers. Although these children share hallmarks of anxious solitude—shyness (e.g., not having much to say to peers) and reticent behavior (onlooking solitary behavior or watching peers play without joining in and unoccupied solitary behavior; Coplan, Rubin, Fox, Calkins, & Stewart, 1994)—when they do interact with peers, the nature of that interaction may nevertheless differ. Even though these children are more rejected and victimized than other children on average (Cillessen, Van Ijzendoorn, Van Lieshout, & Hartup, 1992; Egan & Perry, 1998; French, 1988, 1990; Gazelle et al., 2005), recent research has revealed that there is substantial heterogeneity among AS children in the degree to which they encounter peer adversity (e.g., exclusion or victimization; Gazelle & Ladd, 2003; Gazelle & Rudolph, 2004). Moreover, this evidence has indicated that the adjustment trajectories of AS children who encounter peer adversity diverge from their nonmistreated counterparts over time—excluded AS children display more stable AS and report more depressive symptoms over time. These findings underscore the importance of understanding factors that contribute to heterogeneity in peer relations among AS children.

Consistent with Child × Environment models of development (Cairns, Elder, & Costello, 1996; Magnusson & Stattin, 2006; Sameroff, 1993), differential risk for peer adversity is likely to be a function of both child and environment. With regard to proximal environmental influences, one study found that children whose AS tendencies predated their entry to elementary school were subsequently more likely to experience peer rejection in first-grade classrooms observed to have negative emotional climate (Gazelle, 2006). In regard to distal environmental influences, a number of studies have examined culture as a moderator of risk for peer adversity among shy children (Chen, Rubin, & Li, 1995; Chen, Rubin, Li, & Li, 1999; Chen, Rubin, & Li, 1995; Chen, Rubin, & Sun, 1992; Hart et al., 2000; Schwartz, Chang, & Farver, 2001). However, very little is known about individual-level characteristics that may contribute to differential risk for peer adversity among AS children.

Previous attempts to use individual characteristics to form meaningful subgroups of solitary children have taken two basic approaches: identifying children who display different types of solitary behavior and identifying children who display solitary behavior in combination with other social behaviors. The first approach is not an appropriate method for identifying subgroups of AS children because it does not make distinctions among AS children, but rather between AS children and children who play alone for other reasons (usually social disinterest, although this is usually studied dimensionally and it is unclear whether there is a reliable disinterested group with substantial prevalence; Coplan, Prakash, O'Neil, & Armer, 2004). The second approach is holistic and person oriented in that it places emphasis on how multiple characteristics combine within individuals and how the same characteristic (e.g., anxious solitude) may vary in adaptational significance in individual systems with different assortments of characteristics (Bergman, Magnusson, & El-Khouri, 2003; Magnusson, 1988; Magnusson & Stattin, 2006). The major advantage of this approach is that it focuses on how individuals with particular combinations of characteristics function and are perceived by others as integrated systems. This approach has been more successful in identifying substantial differences in peer treatment among AS children, but it has been largely limited to identification of AS children with and without externalizing behaviors (Feltham, Doyle, Schwartzman, Ledingham, & Serbin, 1985; Gazelle & Ladd, 2003; Harrist, Zaia, Bates, Dodge, & Pettit, 1997; Ladd & Burgess, 1999; Ledingham, Younger, Schwartzman, & Bergeron, 1982; Lyons, Serbin, & Marchessault, 1988). Other than this distinction between externalizing and nonexternalizing AS children, child sex is the only major individual difference that has received substantial attention in investigations of differential risk of peer adversity among AS children.

In sum, current knowledge about individual characteristics that confer differential risk for peer adversity among AS children is limited to child sex and co-occurring aggressive behavior. Although several investigations have found greater peer rejection or exclusion among AS boys than AS girls in middle childhood (e.g., Gazelle & Ladd, 2003; Morison & Masten, 1991), observational and sociometric evidence has indicated that AS girls experience peer adversity as well (French, 1990; Gazelle et al., 2005) and may experience more depressive symptoms as a consequence of exclusion in early adolescence (Gazelle & Rudolph, 2004). Thus, AS children of both sexes are at risk for peer adversity and emotional maladjustment, although the relative degree of risk varies according to developmental time period and the outcome of interest.

Children who demonstrate combined AS and aggressive behaviors have consistently been found to be particularly maladjusted in investigations from multiple laboratories. Aggressive AS children are extremely rejected, highly excluded and victimized, and have few friends (Feltham et al., 1985; Gazelle & Ladd, 2003; Ladd & Burgess, 1999; Ledingham et al., 1982; Lyons et al., 1988). In a low socioeconomic status urban sample, these children were also at particular risk for academic failure, placement in special classes, and eventually school drop out and teenage pregnancy (Ledingham & Schwartzman, 1984; Serbin et al., 1998). Consistent with past investigations, in the present study AS children who display externalizing behaviors were expected to encounter high peer adversity and particularly elevated victimization. But only a moderate proportion of AS children were expected to demonstrate externalizing behaviors, leaving much variability in peer adversity unexplained.

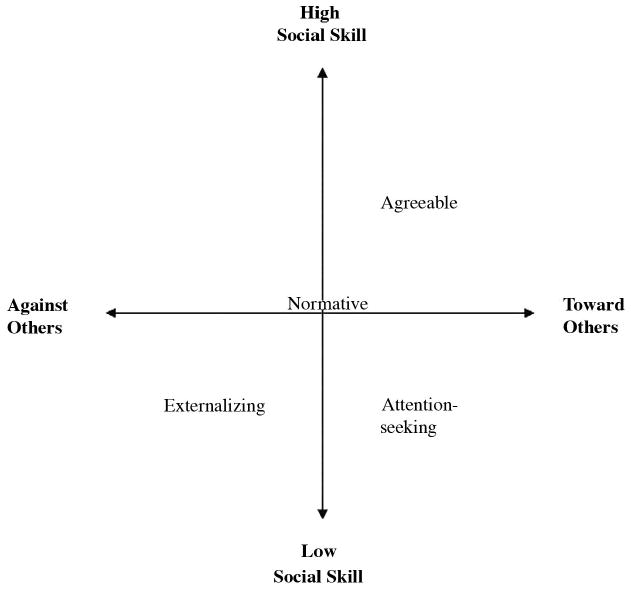

The Present Study

The present study is based on the holistic person-oriented premise that there are multiple behavioral characteristics that substantially buffer or augment AS children's risk for peer adversity (Bergman et al., 2003; Magnusson, 1988; Magnusson & Stattin, 2006). This premise contrasts with the common assumption that nonaggressive AS children are poorly accepted by peers because of an absence of socially desirable behavior rather than the presence of socially undesirable behavior. That is, AS children's low rate of peer interaction is often interpreted to mean that when they are with peers, they “do nothing.” In this study, it is proposed that this assumption is incorrect for some subgroups of AS children. From the perspective of peers, children can be conceptualized as occupying a two-dimensional space in which they vary in regard to both interpersonal orientation (oriented toward or against social interaction with others; Caspi, Elder, & Bem, 1988; Horney, 1945) and social skill (high to low; see Figure 1). In simple terms, peers can be conceptualized as evaluating a child's behavior by asking themselves, “How does the child engage with others?” (do they support or oppose others' actions; interpersonal orientation) and “How well is this engagement executed?” (degree of social skill). Although AS children are often characterized as being oriented “away” from others (social disengagement), when they do come into contact with others they must interact to some extent, and the nature of this interaction can be characterized by an orientation toward or against others (collaborative social engagement or social conflict; Caspi et al., 1988; Horney, 1945). In addition to the externalizing AS group described above, which would be characterized as moving against others in an unskillful manner, and an otherwise behaviorally normative AS subgroup that would be characterized by relatively moderate interpersonal orientation and social skill, this framework suggests the existence of two novel groups. The first is a subgroup that is oriented toward others and high in social skill—it will be referred to as agreeable AS. It is hypothesized that despite their timidity, these AS children display behavior that peers deem highly socially desirable. The second is a subgroup that, again despite their timidity, is oriented toward others but is relatively low in social skill—it will be referred to as attention-seeking–immature AS. It is hypothesized that these AS children display nonexternalizing behavior that peers find undesirable. This group goes against the assumption that an interpersonal orientation toward others implies successful peer relations. These subgroups populate the center and each quadrant of the proposed model with one exception—orientation against others and high social skill (the upper left quadrant). Although this quadrant may apply to some non-AS children (e.g., instrumentally aggressive children), a substantial number of AS children were not expected to display this combination of characteristics, and therefore it does not serve as the basis for an AS subgroup.

Figure 1.

Peers' perceptions of a child can be located on two dimensions: interpersonal orientation (moving toward or against others) and social skill. These dimensions are relevant to both solitary and nonsolitary children. Although solitary children's interpersonal orientation is often characterized as “moving away” from others, when they come into contact with others their interaction can be characterized as moving toward or against others. This figure is intended to be a conceptual tool. Dimensional distances between characteristics were not empirically determined.

Agreeable Anxious Solitary Children

Despite their timidity, agreeable AS children may display highly responsive social behavior that is perceived as desirable by peers. Although such children may not take the initiative in making social overtures, they may be highly responsive to others' overtures by agreeing to cooperate and share, readily returning a smile, and listening to others attentively. These behaviors are referred to as agreeable rather than prosocial to emphasize that they may not require social initiative but rather sensitive responding to others' overtures. Although agreeable behaviors have received little attention in the literature on childhood social withdrawal, in one study socially inhibited children judged to be globally socially competent by their teachers demonstrated positive adjustment over time, including diminished anxious solitude (Asendorpf, 1994). Moreover, the compensatory nature of such socially desirable characteristics for shy individuals has been proposed by Leary and Buckley (2000) in the adult shyness literature. Yet, even in the adult literature, agreeable characteristics in shy individuals have received little empirical attention.

Attention-Seeking–Immature Anxious Solitary Children

Despite their timidity, a substantial subgroup of AS children was expected to display attention-seeking and immature behaviors. Although the coexistence of attention seeking and timidity might appear contradictory at first glance, consideration of the motivational underpinnings of AS supports the possibility of this coexistence. AS children are conceptualized as wanting to interact with peers but being blocked by social anxiety. Asendorpf (1990) has characterized this as a social approach–avoidance conflict. Here, we propose that some AS children may manifest social approach and avoidance behaviors via vacillation between attention-seeking and AS behavior that is readily observable to peers. Attention seeking is behavior that is geared toward attracting peer attention but is inappropriate or incongruous with ongoing peer activities and therefore socially unskillful. For instance, in a previous study, after an AS girl was disqualified from a game of Twister, she repeatedly asked her playmates if they would like to play another game even though they were still clearly engaged in the original game and ignored her interruptions. When children display this sort of behavior, they may appear younger or less mature than their peers. Although AS children have periodically been described as immature or appearing younger relative to agemates (Rubin & Mills, 1988), these characteristics have often been conflated with externalizing behavior, and the relation between variation in this characteristic and peer adversity among AS children has not been systematically investigated. Peers were expected to find attention-seeking and immature behaviors to be irritating. Consequently, attention-seeking–immature AS children were expected to have elevated rates of peer adversity and to be particularly prone to being ignored.

Emphasis on Assets and Risks

One of the ways in which the present framework for identifying AS subgroups differs from past work is identification of subgroups on the basis of assets as well as risks. Consequently, this framework permits predictions about groups expected to have relatively positive peer relations (the agreeable AS group) and differing degrees and forms of peer difficulty. This emphasis on assets and risks also lends itself to examination of subgroup differences on positive characteristics other than those included in subgroup criteria (e.g., agreeableness) that may play a role in buffering AS children from relational difficulty. Specifically, the degree to which children were perceived as fun and good at being leaders was examined because these characteristics were expected to be highly valued by peers. It was unclear whether children who readily cooperated, listened to, and smiled at peers (agreeable characteristics) would be viewed as fun or having leadership qualities because these characteristics suggest a degree of social initiative and spontaneity that might or might not accompany agreeableness.

Additionally, the degree to which children were perceived as smart by peers was examined because this nonsocial behavioral characteristic is salient in the school environment in which peer relations take place. Although a number of previous investigations have found mild negative correlations between measures of intelligence and AS (e.g., Chen et al., 1992; Ludwig & Lazarus, 1983; Morison & Masten, 1991), it was expected that AS children would be heterogeneous in this regard. Furthermore, there is reason to believe that intelligence may serve as an important buffer for behaviorally vulnerable children (Radke-Yarrow & Brown, 1993), although there is more evidence of this to date in children with aggressive rather than AS profiles (Luthar & Zigler, 1992; Masten et al., 1999).

Finally, in addition to examining differences among subgroups in peer group–level acceptance, examination of prevalence and reciprocity of dyadic friendships was planned. Because friends can protect behaviorally vulnerable children from peer victimization (Hodges, Boivin, Vitaro, & Bukowski, 1999; Schwartz, Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 2000), examination of friendship prevalence and reciprocity are part of the broader picture of differences among subgroups in protection versus risk from peer adversity. Also, consistent with a focus on assets and risks, examining friendship provides a more complete view of the benefits some AS children may reap from peer contact.

Developmental Considerations

The proposed AS subgroups were expected to be perceptible to peers and linked to heterogeneous peer relations by third grade. Past investigations have indicated that peers' perceptions of AS are reliable by third grade but relatively unreliable at younger ages, in contrast to peers' perceptions of externalizing behaviors, which are reliable at younger ages (Younger, Schwartzman, & Ledingham, 1985, 1986). It has been suggested that this discrepancy is because of developmental change in peer social cognition. Because AS behavior lacks the direct impact and salience of aggressive behaviors, young peers may not reliably perceive this behavior until they become more cognitively mature around third grade. Given the present focus on linkages between peer perceived behavior and peer treatment, this study focuses on the earliest age at which evidence suggests reliable linkages between peer perceptions of AS and peer treatment.

Peer Processes Linked to the Co-Occurrence of Child Behaviors

The principle that a particular behavioral pattern (anxious solitude) can translate into widely different peer relations depending on co-occurring behaviors is central to the conceptual framework that supports a subgroup approach. Specifically, it was expected that AS behaviors, in and of themselves, would be moderately detrimental to children's peer relations as they limit children's contacts with peers. However, agreeableness was expected to diminish the negative effect of AS children's limited contact with peers by ensuring that when peers initiated contact, these children were highly responsive partners. In contrast, attention-seeking– immature and externalizing behaviors were expected to be aversive to peers. Although aversive behaviors are not always linked to peer mistreatment (Rodkin, Farmer, Pearl, & Van Acker, 2000), it was expected that AS would disinhibit constraints against peer mistreatment toward attention-seeking–immature and externalizing children because peers would perceive them as unable to defend themselves because of their poor capacity for effective social assertion and having few friends who could come to their defense.

Hypotheses

AS children were expected to differ widely in degree of success and adversity in peer relations depending on how their anxious solitude functioned in the context of the whole social person they presented to peers. Specifically, agreeable AS children were expected to be moderately successful with peer relations relative to other AS children, normative AS children to experience less peer adversity than attention-seeking–immature and externalizing AS children, and attention-seeking–immature and externalizing AS children to experience high levels of adversity that would differ somewhat in form. Attention-seeking–immature children were expected to experience particularly heightened exclusion relative to other AS children because of the potentially irritating nature of their interpersonal behavior, and externalizing AS children were expected to experience particularly heightened victimization. It was further expected that both male and female members of the highest risk AS subgroups would experience peer adversity. Finally, when children shared the same subgroup characteristics (agreeableness, attention seeking–immaturity, or externalizing), AS versus non-AS children were expected to demonstrate more interpersonal difficulties and to be perceived by peers as having fewer positive attributes.

Method

Participants

Screening participants were 688 children with informed parental consent (mean age at the outset of the study = 8.66 years, SD = 0.50) drawn from all 46 third-grade public school classrooms in seven elementary schools in a suburban to rural region of the southeastern United States. This sample represents 80% (688/856) of children in these classrooms. Girls and boys were approximately equally represented (51.5% female, n = 354; 48.5% male, n = 334), and the sample was diverse with regard to race and ethnicity (62% European American, 20% African American, 16% Latino, and 2% Asian American). The majority of children resided in English-speaking families, and a minority of children resided in Spanish-speaking families (approximately 9.2%, as determined by parents having selected the Spanish-language version of the permission slip to return; these children attended schools in which English was spoken and comprehended English well enough to complete measures in English). The sample was also diverse in regard to socioeconomic status, with 30% of children receiving free or reduced-cost school lunch.

Subgroup analyses were conducted with children who received sociometric assessments in both the fall and spring (661 children, 96% of screening children), and recess observations were conducted for a selected subset of these children (n = 163). Approximately half of observed participants (n = 80) were selected because they scored at or above 1 standard deviation on the fall peer-reported AS composite. Approximately an equal number of children were selected as demographically matched controls (n = 83) to eliminate demographics as a confound for any observed differences among AS and non-AS children. Controls were selected on the basis of being the closest match for an AS child with regard to sex, ethnicity, age, classroom, and free or reduced-cost lunch status. Selected children did not differ from nonselected children in the screening sample with regard to age (selected: M = 8.70 years, SD = 0.55; nonselected: M = 8.65 years, SD = .48; t(686) = .94, ns) or in the rate at which they received free or reduced-cost lunch (selected, 31%; nonselected, 29%; χ2(1, N = 688) = 0.23, ns). There was a higher frequency of female (59%) than male (41%) selected children, in comparison to nonselected screening children (female, 49%; male, 51%; χ2(1, N = 688) = 4.74, p < .05). The race and ethnicity of the selected sample was diverse and resembled the composition of the screening sample except that marginally more Latino children (χ2(1, N = 688) = 3.53, p < .10) and significantly fewer African American children (χ2(1, N = 688) = 6.19, p < .05) were selected (selected vs. nonselected, respectively: 64% vs. 61% European American, 13% vs. 22% African American, 21% vs. 15% Latino, and 2% vs. 2% Asian American). Because children were selected on the basis of elevated AS scores (or having demographics that matched those of children with elevated AS scores), demographic discrepancies between the screening and selected samples are a result of differential prevalence of elevated AS among demographic groups in this sample.

Although children were selected to be observed at recess on the basis of fall AS peer sociometric nominations (with a cutoff of 1 standard deviation), fall and spring anxious solitude and other peer sociometric scores were subsequently combined in composites and used in analyses (with a top tertile cutoff) to ensure that children were assigned to subgroups on the basis of relatively enduring characteristics (measures used in selection and selection criteria are described in greater detail below). Using fall to spring composites resulted in the same number of AS (n = 80) and non-AS (n = 83) children observed at recess, and demographics remained matched, although 7 children from each group were reclassified. Identifying relatively enduring subgroups with criteria from multiple time points is consistent with previous investigations (Gazelle & Ladd, 2003). Also, using tertile cutoffs is consistent with methods used in previous investigations of childhood solitude (Ladd & Burgess, 1999; Rubin, Chen, & Hymel, 1993; Rubin, Wojslawowicz, Rose-Krasnor, Booth-LaForce, & Burgess, 2006). Preliminary analyses confirmed that using means of fall and spring assessments (rather than using one or both time points separately) resulted in the selection of children with more stable characteristics.

Measures

A summary of intercorrelations among all primary variables appears in Table 1. Sociometrics were administered twice in the fall and spring, and recess observations were conducted after the end of the fall sociometric until the end of the school year. The following sections describe each form of assessment.

Table 1. Intercorrelations Among all Variables.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer-report sociometrics: grouping variables | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Anxious solitary | — | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Agreeable | .01 | — | |||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Attention-seeking–immature | .15*** | −.54*** | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Externalizing | − .13** | −.59*** | .74*** | — | |||||||||||||||||

| Peer-report sociometrics: negative | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Rejected | .21*** | −.63*** | .69*** | .63*** | — | ||||||||||||||||

| 6. Excluded | .56*** | −.35*** | .61*** | .32*** | .64*** | — | |||||||||||||||

| 7. Victimized | .44*** | −.31*** | .62*** | .36*** | .56*** | .76*** | — | ||||||||||||||

| 8. Can't defend self | .66*** | −.15*** | .41*** | .10** | .40*** | .70*** | .65*** | — | |||||||||||||

| Peer-report sociometrics: positive | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 9. Accepted | − .33*** | .55*** | − .43*** | − .29*** | − .65*** | −.55*** | − .43*** | − .40*** | — | ||||||||||||

| 10. Smart | − .15*** | .65*** | − .42*** | − .38*** | − .51*** | −.40*** | − .36*** | − .33*** | .46*** | — | |||||||||||

| 11. Fun | − .31*** | .60*** | − .37*** | − .26*** | − .55*** | −.48*** | − .36*** | − .40*** | .68*** | .60*** | — | ||||||||||

| 12. Leader | − .26*** | .51*** | − .30*** | − .16*** | −.41*** | −.37*** | − .33*** | − .34*** | .56*** | .59*** | .67*** | — | |||||||||

| Recess observations | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 13. Actively accepted | − .33*** | .21** | − .15 | .02 | − .29*** | −.34*** | − .25** | − .33*** | .39*** | .24** | .29*** | .20* | — | ||||||||

| 14. Ignored | .34*** | −.25** | .13 | − .08 | .29*** | .36*** | .30*** | .35*** | −.37*** | − .27*** | − .30*** | − .25** | − .75*** | — | |||||||

| 15. Victimized | .02 | −.17* | .46*** | .30*** | .34*** | .31*** | .27*** | .19* | −.25** | − .15 | − .12 | − .08 | − .23** | .00 | — | ||||||

| 16. Reticent | .36*** | −.19* | .11 | − .08 | .24** | .36*** | .28*** | .33*** | −.34*** | − .25** | − .27*** | − .24** | − .59*** | .70*** | − .02 | — | |||||

| 17. Alone directed | .16* | − .15 | .05 | − .08 | .16* | .18* | .14 | .18* | −.20* | − .18* | − .17* | − .13 | − .55*** | .76*** | .02 | .14 | — | ||||

| Child–peer sociometric friendship | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 18. Reciprocated friends | − .21*** | .34*** | −.24*** | − .19*** | − .35*** | − .29*** | − .20*** | − .22*** | .43*** | .28*** | .41*** | .34*** | .21** | − .23** | − .14 | − .20* | −.14 | — | |||

| 19. Unreciprocated bid (made) | .05 | − .25*** | .18*** | .11* | .18*** | .18*** | .15*** | .10** | −.26*** | − .20*** | − .28*** | − .22*** | − .14 | .12 | .09 | .06 | .08 | −.09* | — | ||

| 20. Unreciprocated bid (received) | − .11** | .35*** | −.24*** | − .17*** | − .35*** | −.24*** | − .19*** | − .17*** | .42*** | .25*** | .35*** | .30*** | .17* | − .08 | − .23** | − .09 | .00 | −.05 | − .28*** | — | |

| 21. Child sex | − .12** | −.33*** | .17*** | .21*** | .14*** | −.01 | .08 | − .03 | −.04 | − .09 | − .07 | − .03 | − .09 | .04 | .23** | .04 | −.03 | −.05 | − .01 | − .05** | — |

Note. N = 661 for sociometrics, N = 657 for reciprocated friendship, and N = 163 for recess observations. Sociometric composites are the mean of fall and spring assessments.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Peer Sociometrics: Grouping Variables

Peer nominations were administered simultaneously to participating children in each classroom. Each nomination was read aloud to the class and then children selected classmates' names on their individual class rosters. Nominations were unlimited, and cross-sex nominations were allowed because these procedures result in superior psychometric properties (Foster, Bell-Dolan, & Berler, 1986; Terry & Coie, 1991). Children's scores on each item were equal to the total number of nominations they received from classmates. These scores were standardized by classroom to control for variation in classroom size. Multi-item composites were computed as detailed below.

Anxious solitude

The AS composite consists of three nominations: Peers nominate classmates who (a) “act really shy around other kids. They seem to be nervous or afraid to be around other kids and they don't talk much. They often play alone at recess,” (b) “Watch what other kids are doing but don't join in. At recess they watch other kids playing but they play by themselves,” and (c) “are very quiet. They don't have much to say to other kids.” These nominations are adapted from previous investigations (e.g., Gazelle & Ladd, 2003). This composite demonstrated adequate reliability at each time point (αs = .76–.86) and 6-month stability (r = .72, p < .001). The mean of fall and spring assessments for this and all other sociometric composites is used in analyses.

Agreeableness

Peers nominated classmates who (a) “are friendly and nice. They smile and say ‘Hi’ to everyone” and (b) “are good at helping and sharing with other kids. They cooperate with other kids. For example, they let other kids have a turn.” This composite demonstrated adequate reliability (α = .59–.84) and stability (r = .56, p < .001).

Attention-seeking–immaturity

Peers nominated classmates who (a) “try to get attention from other kids in ways that are annoying or bother other kids” and (b) “act younger than other kids their age.” This composite demonstrated adequate reliability (αs = .72–79) and stability (r = .70, p < .001).

Externalizing behaviors

Peers nominated classmates who (a) “start fights, call kids bad names, say mean things, and hit other kids,” (b) “make up stories about other kids that aren't true and spread rumors about kids in their class,” and (c) “get out of their seats a lot, act wild, and make a lot of noise. They bother people who are trying to work.” This composite demonstrated adequate reliability (αs = .80–.83) and stability (r = .73, p < .001).

Because attention-seeking–immature and externalizing composites were positively correlated (r2 = .54 indicates that although they share about half their variance, half of their variance is unshared), a confirmatory factor analysis was performed to contrast a three-factor model of subgroup characteristics in which agreeableness, attention seeking–immaturity, and externalizing items were allowed to contribute only to their respective latent constructs to an analogous two-factor model in which agreeableness was estimated in the same way but attention-seeking–immature and externalizing items contributed to a combined factor. Results indicated that the three-factor model had better fit (comparative fit index = .96, goodness-of-fit index = .96, standardized root-mean-square residual = .03; all items loaded significantly onto the expected latent constructs λs = .65–.84). This result supports the notion that although some externalizing behaviors are perceived as attention seeking–immature, nonexternalizing behaviors are the primary determinants of attention seeking–immaturity.

Identification of behavioral groups

Children were identified as AS if they were in the top tertile of the peer-reported AS composite consisting of both fall and spring assessments (n = 129). Children scoring below the AS cutoff were classified as non-AS (n = 532). More girls than boys were above the threshold for AS (62%; χ2 = 7.45, p < .01). Although some investigators have standardized sociometric scores for AS and other characteristics by sex, it was considered preferable to preserve sex differences so that they could be explicitly tested in analyses.

Both AS and non-AS versions of the following mutually exclusive groups were identified. Behaviorally normative children were below the top tertile in agreeable, attention-seeking–immature, and externalizing composites (AS, n = 42; non-AS, n = 201). Agreeable children were at or above the top tertile in the agreeable composite and below the top tertile in attention-seeking–immature and externalizing composites (AS, n = 39; non-AS, n = 169). Attention-seeking–immature children were at or above the top tertile in the attention-seeking–immature composite and below the top tertile in the externalizing composite (AS, n = 22; non-AS, n = 23). Externalizing children were at or above the top tertile in the externalizing composite (AS, n = 26; non-AS, n = 139). Note that externalizing criteria “trump” all other subgroup behaviors because externalizing behavior was expected to (a) counteract the benefits of agreeableness and (b) attract attention and therefore be perceived as attention seeking–immature. Similarly, attention-seeking–immature criteria trump agreeableness because these behaviors were also expected to counteract the benefits of agreeableness. Consistent with expectations, few children demonstrated the combination of high agreeableness and either externalizing or attention seeking–immaturity (n = 5), but the combination of externalizing and attention seeking–immaturity was common (see below). See Table 2 for a summary of group sample sizes for both sociometric and observational data, sex, and identification criteria. Although there were more girls than boys in the agreeable AS subgroup (χ2 = 16.03, p < .001), there were no significant differences in the number of boys and girls in other AS subgroups. Attention-seeking–immature children were clearly low in externalizing behavior; they not only scored below the top tertile in externalizing behavior by definition, but scored below the mean for externalizing behavior on average (attention-seeking–immature AS, M = −0.22, SD = 0.42; attention-seeking–immature non-AS, M = −0.06, SD = 0.26). Externalizing children, like attention-seeking–immature children, had extreme scores on attention-seeking–immaturity (externalizing AS, M = 2.24, SD = 1.31; externalizing non-AS, M = 0.92, SD = 0.99). Thus, although both attention-seeking–immature and externalizing children were perceived as highly attention seeking and immature by peers, these groups were clearly differentiated by the absence versus presence of externalizing behaviors.

Table 2. Behavioral Groups.

| Group | Sociometric data | Observational data | Grouping criteria | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxious solitary | Non anxious solitary | N | Anxious solitary | Non anxious solitary | N | Agreeable | Attention seeking | Externalizing | |||||

| n | % female | n | % female | n | % female | n | % female | ||||||

| Agreeable | 39 | 82 | 169 | 74 | 22 | 91 | 38 | 71 | ≥Top tertile | <Top tertile | <Top tertile | ||

| Normative | 42 | 62 | 201 | 40 | 28 | 61 | 29 | 52 | <Top tertile | <Top tertile | <Top tertile | ||

| Attention-seeking–immature | 22 | 55 | 23 | 35 | 15 | 53 | 4 | 50 | ≥Top tertile | <Top tertile | |||

| Externalizing | 26 | 38 | 139 | 35 | 15 | 33 | 12 | 17 | ≥Top tertile | ||||

| Total | 129 | 62 | 532 | 49 | 661 | 80 | 63 | 83 | 55 | 163 | |||

| % of Total | 20% | 80% | 100 | 49% | 51% | 100 | |||||||

Note. The sample of children with observational data is a subset of the full sample.

Peer Sociometrics: Peer Relations and Additional Child Characteristics

Negative Peer Nominations

Rejection

Peers nominated classmates who “you do not like to play with” (stability: r = .54, p < .001).

Exclusion

Peers nominated classmates who (a) “get left out when other kids are talking or playing together. They don't get invited to parties or chosen to be on teams or to be work partners” and (b) “ask if they can play and other kids say ‘no’ and won't let them play.” This composite demonstrated adequate reliability (αs = .73–.83) and stability (r = .68, p < .001).

Victimization

Peers nominated classmates who “get picked on and made fun of by other kids. They get teased or get called names” and “get hit, kicked, or pushed by other kids” (the second item was available in the spring only, α = .60; stability: r = .60, p < .001).

Inability to defend oneself

Peers nominated classmates who “don't know how to stick up for themselves or defend themselves when other kids pick on them. They don't know what to do or say when other kids pick on them or tease them” (stability: r = .55, p < .001). Single-item sociometric indices, because of their multi-informant nature, have good psychometric properties (Coie, Dodge, & Kupersmidt, 1990). As with other sociometric indices, scores for these measures were calculated as the mean of fall and spring assessments.

Peer Sociometrics: Peer Relations and Additional Child Characteristics

Positive Peer Nominations

Accepted

Peers nominated classmates who they “like to play with a lot” (stability: r = .53, p < .001). Consistent with past investigations that have established peer acceptance and rejection as separate dimensions rather than opposite ends of the same continuum, peer acceptance and rejection were moderately negatively correlated (r = −.65, p < .001; Coie, Dodge, & Coppotelli, 1982).

Smart

Peers nominated classmates who “do very well at school and earn high grades. They are smart” (stability: r = .72, p < .001). This nomination was positively correlated with children's actual average grades (r = .39, p < .001) and end-of-grade achievement test scores (r = .37, p < .001), which were obtained only for observed children.

Fun

Peers nominated classmates who “have great ideas about what to play. They always seem to have something interesting to talk about and to have a lot of fun” (stability: r = .46, p < .001).

Leader

Peers nominated classmates who “are the leaders, the kids who others look up to” (stability: r = .52, p < .001). Again, scores for these measures were calculated as the mean of fall and spring assessments.

Close friends

Peers nominated an unlimited number of classmates who “are your close friends.” This item demonstrated adequate stability (r = .51, p < .001). No restraints were placed on the sex of friendship pairs. When children chose each other as a close friend, their friendship was counted as a “reciprocal friend.” When a child chose a friend who did not choose him or her in return, this was counted as an “unreciprocated bid made.” When a child received a bid that he or she did not return this was counted as an “unreciprocated bid received.”

Observations of Behavior and Peer Treatment

Selected children (n = 163) were observed during naturalistic free play at school recess. Trained observers recorded the child's behavior and simultaneous peer response for five 5-min sessions on at least 3 different days for a total of 25 min of recess observation. The occurrence of mutually exclusive child behaviors and peer responses were coded live in 30-s observe, 30-s record intervals. Scores reported indicate the proportion of intervals that a behavior or peer response occurred (number of intervals code observed/total number of observational intervals). The Peer Interaction Observational System (PIOS) was created for this investigation. The PIOS was adapted from two existing observational systems: the Play Observation System (Rubin, 2001) and a system developed by Putallaz and Wasserman (1989). Distinctions between types of solitary behavior (e.g., onlooking, unoccupied, and directed) were drawn from the Play Observation System. However, several adaptations were necessary because the Peer Interaction Observational System is intended for live observation of naturalistic recess interaction in middle childhood, whereas the Play Observation System has primarily been used in laboratory settings with delayed video-coding with younger children (i.e., preschool and kindergarten). The Peer Interaction Observational System uses longer coding intervals (30 s vs. 10 s) and does not distinguish between cognitive levels of play (e.g., constructive vs. exploratory solitary play are both scored as directed solitary play), which are less relevant in this older age group. Furthermore, PIOS codes capture both child behavior and peer response, whereas POS codes capture only child behavior. Peer treatment was captured by adapting a system developed by Putallaz and Wasserman (1989). This system simultaneously codes target child behavior and peer treatment of the target child for each observational interval. The codes within each category (child behavior or peer treatment) are mutually exclusive. Peer treatment includes acceptance, ignoring, and victimization. When more than one behavior or peer treatment occurred in a 30-s interval, the code with the longest duration was recorded (but systematic exceptions to the duration rule were made for actions that could be brief, such as victimization). To test interrater reliability, 24% of observations were conducted simultaneously by two observers. The operational definition and interrater reliability (kappa) for each observational category relevant to the current report is described below.

Active acceptance: The child was engaged in a joint activity with a single partner or group and participated in verbal or gestural communication (give and take; κ = .84).

Ignore: Peers did not acknowledge the child nor include the child in group activity (κ = .96).

Victimization: Peers acted negatively toward the child through unfriendly teasing, hitting, or pushing or other negative behavior (κ = .95).

Alone directed: The child was alone and engaged in an activity (e.g., playing on the slide, shooting baskets, or reading; κ = .87).

Reticence: Reticence is a composite of both onlooking and unoccupied solitary behavior. Onlooking solitary behavior was coded when the child was alone and placed him- or herself within approximately 10 ft of peers and visually attended to their activity without making any overt attempt to join (κ = .90). Unoccupied solitary behavior was coded when the child was alone and not involved in a purposeful activity (e.g., staring into space or wandering aimlessly; κ = .86).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Before examining hypothesized differences among AS subgroups, continuous variables involved in subgroup definition were examined for properties that would support a subgroup approach. Specifically, hierarchical linear regression analyses were performed to test whether the relations between subgroup characteristics and AS in predicting criterions consisted of main effects only or of interaction effects as well. The logic behind this analysis is that if the relations consisted only of main effects, then this pattern in the data could be most efficiently demonstrated by an analysis such as multiple regression in which the additive effects of all possible combinations of multiple variables could be inferred from results. If interaction effects were found, however, this suggests that certain characteristics take on special significance when they co-occur with other specific characteristics within individuals. Thus, interaction effects support the utility of a subgroup approach, which is especially efficient at representing differences among and prevalence of groups of children with specific patterns of co-occurring characteristics. Results of hierarchical multiple regression of criterions on subgroup characteristics dummy coded to reflect subgroup cutoffs (1 = top tertile, 0 = bottom two tertiles) revealed both significant main and interactive effects for all subgroup variables and all sociometric criterion classes (with variation in effects by criterion; see Table 3), supporting the appropriateness of subgroups. Because subgroup comparisons were considered to be the primary means of analysis, individual interactions are not graphed and described. Nonetheless, the overall pattern of interactions supports subgroup analyses by indicating that heightened subgroup behaviors had an amplified impact on children's peer relations when they co-occurred versus did not co-occur with heightened AS. Although only main but no interaction effects emerged for recess observation criterions, subgroup analyses are reported on these data to illustrate differences among the same subgroups via multiple methods (observation and sociometrics). Subgroup analyses were particularly efficient at representing these data in which multiple interactions occurred.

Table 3. Multiple Interactive Effects of Subgrouping Variables in Regression Support a Subgroup Approach Across Most Criterions.

| Variables | Negative sociometrics (peer evaluation–treatment and child response)a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rejected | Excluded | Victimized | Can't defend self | |||||

| β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| AS | 0.18 | 3.74*** | 0.39 | 8.50*** | 0.27 | 5.35*** | 0.45 | 9.06*** |

| Agreeable | −0.25 | −6.75*** | −0.11 | −3.11** | −0.01 | −0.22 | −0.03 | −0.69 |

| Attention-seeking–immature | 0.24 | 5.24*** | 0.26 | 5.92*** | 0.26 | 5.52*** | 0.13 | 2.80** |

| Externalizing | 0.28 | 6.32*** | 0.07 | 1.70** | 0.10 | 2.24* | 0.02 | 0.42 |

| AS × Agreeable | −0.03 | −0.69* | −0.03 | −0.73 | 0.01 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.62 |

| AS × Attention Seeking | 0.11 | 2.16* | 0.20 | 4.12*** | 0.19 | 3.70*** | 0.23 | 4.48*** |

| AS × Externalizing | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.91 | 0.12 | 2.72** | −0.01 | −0.23 |

| Sex | −0.06 | − 1.13 | −0.12 | −2.42* | −0.04 | −0.71 | −0.06 | − 1.13 |

| Sex × AS | 0.15 | 2.88** | 0.19 | 3.66*** | 0.09 | 1.71† | 0.11 | 2.02* |

| Sex × Agreeable | 0.02 | 0.37 | 0.04 | 0.86 | 0.04 | 0.83 | −0.02 | −0.44 |

| Sex × Attention | −0.07 | − 1.36 | −0.06 | − 1.28 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.34 |

| Sex × Externalizing | 0.04 | 0.74 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.03 | −0.52 |

| Sex × AS × Agreeable | −0.04 | −0.81 | −0.04 | −0.77 | 0.04 | 0.88 | 0.06 | 1.20 |

| Sex × AS × Attention | 0.04 | 0.82 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.26 | −0.08 | − 1.50 |

| Sex × AS × Externalizing | −0.10 | −2.37* | −0.08 | − 1.86† | −0.07 | − 1.51 | 0.07 | 1.58 |

| Positive sociometrics (peer evaluation and child response)a | ||||||||

| Accepted | Smart | Fun | Leader | |||||

| AS | −0.33 | − 8.75*** | −0.16 | −4.36*** | −0.33 | −9.18*** | −0.27 | −6.87*** |

| Agreeable | 0.53 | 14.30*** | 0.63 | 17.18*** | 0.66 | 18.54*** | 0.61 | 15.75*** |

| Attention-seeking–immature | −0.20 | −3.97*** | − 0.10 | − 1.94† | −0.13 | −2.64** | −0.18 | −3.39*** |

| Externalizing | 0.12 | 2.47** | 0.04 | 0.84 | 0.18 | 3.71*** | 0.30 | 5.72*** |

| AS × Agreeable | −0.07 | −2.00* | − 0.01 | −0.28 | −0.12 | −3.37*** | −0.12 | −3.14** |

| AS × Attention Seeking | 0.03 | 0.77 | 0.04 | 0.88 | 0.07 | 1.75† | −0.08 | 1.76† |

| AS × Externalizing | −0.08 | − 1.78† | − 0.04 | −0.82 | −0.10 | −2.39* | −0.13 | −2.76** |

| Observed peer treatment and child behaviorb | ||||||||

| Actively accepted | Ignored | Victimized | Alone directed | |||||

| AS | −0.23 | −2.25* | 0.20 | 1.98* | −0.20 | −2.01* | 0.03 | 0.31 |

| Agreeable | 0.22 | 2.06* | −0.27 | −2.62** | 0.05 | 0.48 | −0.20 | − 1.83† |

| Attention-seeking–immature | −0.06 | −0.39 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.56 | 3.69*** | −0.02 | −0.13 |

| Externalizing | 0.13 | 1.07 | − 0.22 | − 1.82† | −0.02 | −0.14 | −0.18 | − 1.39 |

| AS × Agreeable | − 0.03 | − 0.28 | − 0.04 | −0.43 | 0.03 | 0.29 | −0.01 | −0.12 |

| AS × Attention Seeking | −0.07 | −0.50 | 0.11 | 0.76 | 0.09 | 0.68 | 0.16 | 1.07 |

| AS × Externalizing | 0.06 | 0.51 | −0.06 | −0.51 | −0.17 | − 1.52 | −0.09 | −0.76 |

| Reciprocity of child–peer friendshipc | ||||||||

| Reciprocated bid | Unreciprocated bid made | Unreciprocated bid received | ||||||

| Constant | 1.61 | 33.27*** | 1.58 | 26.55*** | 1.48 | 29.17*** | ||

| AS | −0.30 | − 5.02*** | 0.08 | 1.15 | −0.16 | −2.60** | ||

| Agreeable | 0.43 | 7.39*** | −0.40 | − 5.60*** | 0.48 | 7.88*** | ||

| Attention-seeking–immature | −0.09 | − 1.09 | 0.31 | 3.28*** | −0.14 | − 1.73† | ||

| Externalizing | 0.04 | 0.48 | −0.28 | −2.94** | 0.14 | 1.67† | ||

| AS × Agreeable | −0.10 | − 1.66† | 0.09 | 1.24 | −0.03 | −0.58 | ||

| AS × Attention Seeking | 0.04 | 0.63 | −0.16 | −2.36* | 0.04 | 0.67 | ||

| AS × Externalizing | −0.06 | −0.89 | 0.14 | 1.60 | −0.13 | − 1.73† | ||

Note. All betas are standardized except for friendship. AS = anxious solitary.

N = 661.

N = 163.

N = 657.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

p < .10.

Anxious Solitary Versus Non-Anxious Solitary Children

Before proceeding to examine differences among subgroups in peer relations, initial analyses were conducted to confirm that children identified as AS by their peers demonstrated reticent behavior at recess and perceived themselves as exhibiting such behavior. All AS subgroups were expected to differ from non-AS subgroups in observed reticent behavior (onlooking and unoccupied solitary behavior), as this is considered to be the hallmark of AS (Coplan et al., 1994). As expected, a 2 × 2 (AS or Non-AS Group × Sex) analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed that AS groups displayed significantly more reticent behavior at recess than did non-AS groups (Ms = .14 and .07, SDs = .14 and = .09, respectively; F(1) = 13.01, p < .001). These means indicate that AS children were observed to spend twice as many intervals engaged in reticent behavior at recess than other children. There was no significant effect for sex (F(1) = 0.54, ns) nor of the Group × Sex interaction (F(1) = 0.04, ns). Further analyses revealed that there were no significant differences among AS subgroups in reticent behavior. Furthermore, a 2 × 2 (AS or Non-AS Group × Sex) ANOVA revealed that AS groups nominated themselves for AS behavior on the sociometric interview (M = .86, SD = .82) significantly more often than did non-AS groups (M = .38, SD = .60, F(1) = 50.41, p < .001). Girls tended to nominate themselves as AS more often than did boys (girls: M = .55, SD = .72; boys: M = .40, SD = .62; F(1) = 3.02, p < .10), but there was no interaction of AS group with sex (F(1) = 0.00, ns). Finally, there were no significant differences among AS subgroups in AS self-nominations. Thus, children identified by peers as AS were confirmed to display elevated reticent behavior at recess and to perceive themselves as more AS than other children. Subsequent analyses examined differences among all subgroups in success and adversity in peer relations, additional child characteristics, and prevalence and reciprocity of friendships.

Multivariate Analyses

Differences among subgroups were examined with multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs). Separate MANOVAs were performed for the following criterion categories: peer sociometrics (positive and negative nominations were analyzed separately), recess observations, and child–peer friendship bids (also derived from sociometrics). In each two-way MANOVA, the effects of behavioral subgroup, child sex, and the interaction between behavioral subgroup and child sex were examined. Each MANOVA yielded significant multivariate behavioral subgroup differences and, except for negative sociometrics, no significant Sex × Behavioral Subgroup interactions (see Tables 4–7). Thus, follow-up Games-Howell multiple comparison tests were conducted to further examine subgroup differences for children combined by sex for all dependent measures except negative sociometrics, for which subgroup differences are reported separately by sex.

Table 4. Negative Peer Sociometrics Multivariate Analysis of Variance: Significant Mean Differences Among Girls' and Boys' Subgroups in Negative Sociometrics.

| Behavioral groups | Peer evaluation/treatment | Child response: Can't defend self | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rejected | Excluded | Victimized | ||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Multivariate behavioral group F | 28.65*** | |||||||

| Multivariate sex F | 1.76 | |||||||

| Multivariate Behavioral Group × Sex F | 2.03** | |||||||

| Girls | ||||||||

| Univariate behavioral group F | 15.56*** | 17.99*** | 10.44*** | 12.38*** | ||||

| Behavioral group partial η2 | 0.44 | 0.48 | 0.40 | 0.39 | ||||

| Agreeable | −0.61a | 0.48 | −0.46a | 0.33 | −0.34a, c | 0.43 | −0.28a | 0.45 |

| Agreeable AS | −0.50a, b | 0.47 | −0.01b, c | 0.76 | −0.10a, b, c | 0.73 | 0.39c,, d | 0.90 |

| Normative | −0.13c | 0.64 | −0.19b | 0.49 | −0.26a, c | 0.44 | −0.24a, b | 0.49 |

| Normative AS | −0.06b, c | 0.83 | 0.42c | 0.97 | 0.18b, c, d | 0.66 | 0.55c, d | 1.00 |

| Attention-seeking–immature | 0.24a, b, c, d | 0.89 | 0.21a, b, c | 0.65 | 0.03c | 0.48 | 0.20a, b, c, d | 0.81 |

| Attention-seeking–immature AS | 0.75d, e | 0.63 | 1.67d | 0.97 | 0.98d, e | 0.86 | 1.81e | 0.94 |

| Externalizing | 0.72d | 0.89 | 0.37c | 0.86 | 0.21b, c, d | 0.68 | −0.01b c | 0.55 |

| Externalizing AS | 1.63e | 0.80 | 2.28d | 1.16 | 1.99e | 1.19 | 1.43d, e | 1.19 |

| Boys | ||||||||

| Univariate behavioral group F | 32.55*** | 38.67*** | 28.22*** | 36.18*** | ||||

| Behavioral group partial η2 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.39 | 0.45 | ||||

| Agreeable | −0.61a, c | 0.44 | −0.54a | 0.27 | −0.35a | 0.37 | −0.43a | 0.50 |

| Agreeable AS | −0.17c | 0.74 | 0.73 | 1.23 | 0.74 | 1.14 | 1.40b | 0.81 |

| Normative | −0.23b, c | 0.55 | −0.41a, b | 0.31 | −0.30a | 0.50 | −0.34a | 0.51 |

| Normative AS | 0.51c, d, e | 0.74 | 0.88c, d | 1.14 | 0.43b, c | 0.84 | 0.95b | 1.21 |

| Attention-seeking–immature | −0.08b, c, d | 0.60 | −0.05b, c | 0.54 | 0.11b | 0.47 | −0.10a | 0.51 |

| Attention-seeking–immature AS | 1.11e | 0.74 | 1.85d | 1.22 | 1.37c, d | 0.90 | 1.38b | 1.28 |

| Externalizing | 0.61c, e | 0.76 | 0.06c | 0.87 | 0.21b | 0.81 | −0.15a | 0.67 |

| Externalizing AS | 1.32e | 0.97 | 1.81d | 1.36 | 1.73d | 1.25 | 1.80b | 1.29 |

Note. N = 661 (341 girls). Means in the same column and panel with different subscripts are significantly different from each other at p < .05 or better. AS = anxious solitary. All criterions are standardized.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 7. Peer Friendships Multivariate Analysis of Variance: Significant Differences Among Subgroups in Mean Number of Friendships With Varying Levels of Reciprocity.

| Behavioral group | Reciprocity of child–peer friendship | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reciprocated bid | Unreciprocated bid made | Unreciprocated bid received | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Multivariate behavioral group F | 8.40*** | |||||

| Multivariate Sex F | 1.26 | |||||

| Multivariate Behavioral Group × Sex F | 1.34 | |||||

| Univariate behavioral group F | 11.00*** | 4.35*** | 10.22*** | |||

| Behavioral group partial η2 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.10 | |||

| Agreeable | 2.23a | 1.28 | 1.07a | 1.26 | 2.11a | 1.43 |

| Agreeable AS | 1.67a, b, c | 1.20 | 1.59 | 1.27 | 1.95a, b | 1.50 |

| Normative | 1.65b | 1.22 | 1.59b | 1.58 | 1.43b, c | 1.27 |

| Normative AS | 1.10b, d | 1.22 | 1.59 | 1.58 | 1.22b, c, d, e | 1.08 |

| Attention seeking–immature | 1.26b, d | 1.32 | 2.13 | 1.71 | 1.04b, c, d, e | 1.33 |

| Attention seeking–immature AS | 0.91c, d | 0.92 | 1.50 | 1.22 | 0.86d, e | 0.71 |

| Externalizing | 1.32b, d | 1.24 | 1.85b | 1.63 | 1.17c, d | 1.14 |

| Externalizing AS | 0.88d | 0.95 | 1.92 | 1.47 | 0.62e | 0.70 |

Note. N = 657. Means in the same column with different subscripts are significantly different from each other at p < .05 or better. Values represent number of friendship bids. AS = anxious solitary.

p < .001.

The next section describes differences among behavioral subgroups as tested with follow-up Games-Howell multiple comparison tests. Each AS subgroup is described in turn. The textual description emphasizes differences among AS groups, but differences between AS subgroups and their same-behavior non-AS counterparts are also described to illustrate the effects of subgroup characteristics both in combination with and separate from AS.

Agreeable Anxious Solitary Children

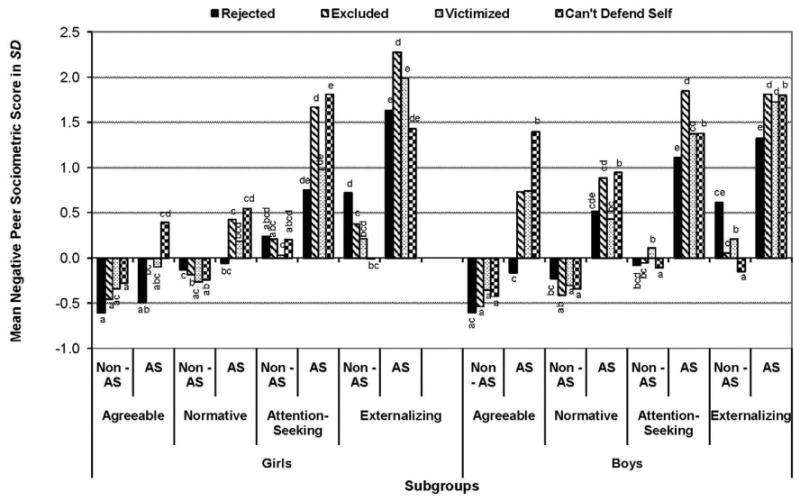

Consistent with hypotheses, sociometric data indicated that agreeable AS children, and agreeable AS girls in particular, fared well with peer relations. Agreeable AS children, especially girls, experienced little peer adversity. Agreeable AS children were significantly less rejected than attention-seeking–immature and externalizing AS subgroups (M = −0.50 to −0.17 vs. 0.75 to 1.63 SD). Moreover, agreeable AS girls were significantly less excluded and victimized than attention-seeking–immature and externalizing AS girls (M = −0.10 to −0.01, 0.98 to 2.28 SD). Agreeable AS girls were also perceived by peers as less unable to defend themselves than attention-seeking–immature AS girls (M = 0.39 vs. 1.81 SD). In contrast, agreeable AS boys demonstrated moderate elevation in exclusion and victimization (M = .73 vs. .74 SD) but did not differ significantly from other groups in this regard. Agreeable AS boys, like all other AS boys' groups, were perceived as significantly more unable to defend themselves than boys in all non-AS groups (M = 1.40 vs. −0.10 to −0.43 SD). Agreeable AS and non-AS children were both relatively low on peer difficulties, but agreeable AS children were significantly more excluded (girls only; M = −0.01 vs. −0.46 SD) and perceived to be more unable to defend themselves (M = 0.39 vs. −0.28 SD). See Table 4 and Figure 2. Agreeable AS girls' and boys' groups were significantly less excluded and victimized and perceived to be less unable to defend themselves (M = −0.10 to 0.39 vs. 0.73 to 1.40 SD; ts = −2.06 to −2.72, ps < .05; see Table 4 and Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mean negative peer sociometrics by subgroup and sex. Subgroups of the same gender with different superscripts for the same criterion differ from each other at p < .05 or better. This figure corresponds to Table 4. AS = anxious solitary.

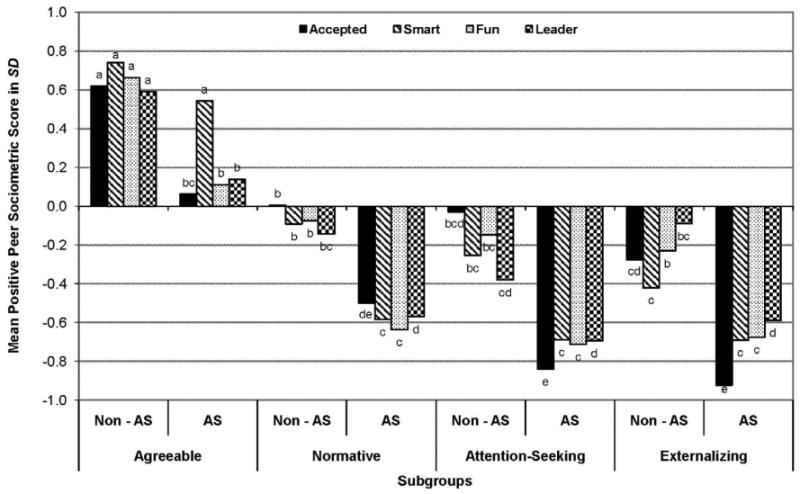

Moreover, peers liked agreeable AS children and perceived them to possess positive attributes. Agreeable AS children were significantly better accepted than all other AS subgroups (M = 0.06 to −0.50 vs. −0.92 SD). Furthermore, peers reported that agreeable AS children were significantly smarter (M = 0.54), fun, and better leaders (M = 0.11 to 0.14) in comparison to other AS subgroups (M = −0.57 to −0.71, on each positive attribute). Although agreeable AS children were viewed positively relative to other AS subgroups, they were viewed significantly less positively than agreeable non-AS children on all positive attributes except smart (M = 0.06 to 0.54 vs. 0.59 to 0.74 SD). See Table 5 and Figure 3.

Table 5. Positive Peer Sociometrics Multivariate Analysis of Variance: Significant Mean Differences Among Subgroups in Positive Sociometrics.

| Behavioral groups | Peer evaluation: Accepted | Child characteristics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smart | Fun | Leader | ||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Multivariate behavioral group F | 13.13*** | |||||||

| Multivariate sex F | 0.99 | |||||||

| Multivariate Behavioral Group × Sex F | 0.97 | |||||||

| Univariate behavioral group F | 30.01*** | 37.55*** | 31.25*** | 25.32*** | ||||

| Behavioral group partial η2 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.22 | ||||

| Agreeable | 0.62a | 0.69 | 0.74a | 0.83 | 0.66a | 0.72 | 0.59a | 0.94 |

| Agreeable AS | 0.06b, c | 0.84 | 0.54a | 0.85 | 0.11b | 0.80 | 0.14b | 0.86 |

| Normative | 0.00b | 0.70 | −0.09b | 0.74 | −0.07b | 0.66 | −0.14b, c | 0.63 |

| Normative AS | −0.50d,e | 0.71 | −0.58c | 0.71 | −0.64c | 0.48 | −0.57d | 0.33 |

| Attention-seeking–immature | −0.03b c d | 0.89 | −0.25b c | 0.79 | −0.15b, c | 0.75 | −0.38c, d | 0.56 |

| Attention-seeking–immature AS | −0.84e | 0.65 | −0.69c | 0.85 | −0.71c | 0.63 | −0.69d | 0.51 |

| Externalizing | −0.28c, d | 0.84 | −0.42c | 0.70 | −0.23b | 0.84 | −0.09b, c | 0.83 |

| Externalizing AS | −0.92e | 0.71 | −0.69c | 0.59 | −0.67c | 0.67 | −0.59d | 0.60 |

Note. N = 661. Means in the same column with different subscripts are significantly different from each other at p < .05 or better. AS = anxious solitary. All criterions are standardized.

p < .001.

Figure 3.

Mean positive peer sociometrics by subgroup. Subgroups with different superscripts for the same criterion differ from each other at p < .05 or better. This figure corresponds to Table 5. AS = anxious solitary.

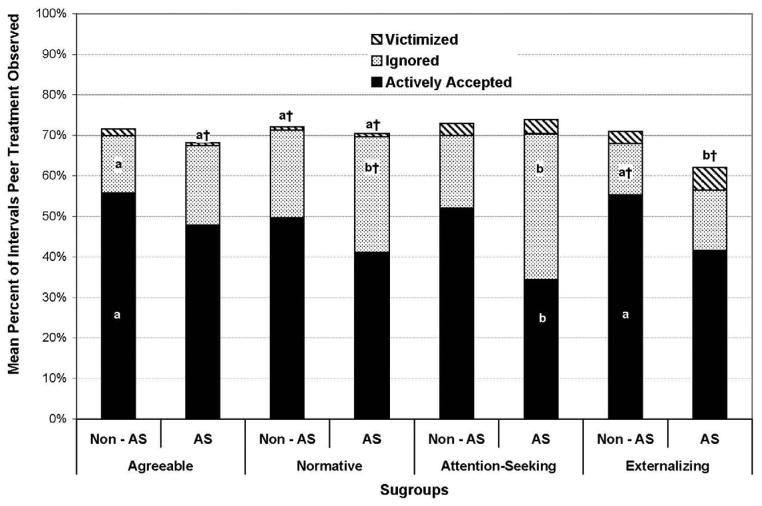

Recess observations, consistent with sociometrics, indicated that agreeable AS children seldom encountered peer adversity. Agreeable AS children were marginally less often victimized by peers than externalizing AS children (M = 1% vs. 6% of intervals). See Table 6 and Figure 4. Note that peer treatment does not add up to 100% of intervals in Figure 4 because a few additional categories (passive acceptance, being approached, and rough-and-tumble play) that did not result in significant differences among subgroups are not shown.

Table 6. Recess Observations Multivariate Analysis of Variance: Significant Differences Among Subgroups in Mean Proportion of Intervals That Peer Treatment of Child Behavior Was Observed at Recess.

| Behavioral groups | Peer treatment | Child behavior: Alone directed | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actively accepted | Ignored | Victimized | ||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Multivariate behavioral group F | 2.40*** | |||||||

| Multivariate Sex F | 2.23 † | |||||||

| Multivariate Behavioral Group × Sex F | 0.67 | |||||||

| Univariate behavioral group F | 2.56* | 3.07** | 5.17*** | 2.29* | ||||

| Behavioral group partial η2 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.10 | ||||

| Agreeable | 0.56a | 0.21 | 0.14a | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.14 |

| Agreeable AS | 0.48 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.13 | 0.01a† | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.10 |

| Normative | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.01a† | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.17 |

| Normative AS | 0.41 | 0.21 | 0.29b† | 0.21 | 0.01a† | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.15 |

| Attention-seeking–immature | 0.52 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| Attention-seeking–immature AS | 0.34b | 0.19 | 0.36b | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.25b† | 0.21 |

| Externalizing | 0.55a | 0.11 | 0.13a† | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.06a† | 0.09 |

| Externalizing AS | 0.42 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.06b† | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.11 |

Note. N = 163. Means are the proportion of intervals in which peer treatment or child behavior was observed. Means in the same column with different subscripts are significantly different from each other at p < .05 (two-tailed). AS = anxious solitary.

Means in the same column with different subscripts are significantly different from each other at p < .05 (one-tailed).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

p < .10.

Figure 4.

Mean percentage of observed recess interaction and behavior by subgroup. Subgroups with different superscripts for the same criterion differ from each other at p < .05 or better. This figure corresponds to Table 6. Note that peer treatment does not add up to 100% of intervals in Figure 4 because a few additional categories (passive acceptance, being approached, and rough-and-tumble play) that did not result in significant differences among subgroups are not shown. AS = anxious solitary.

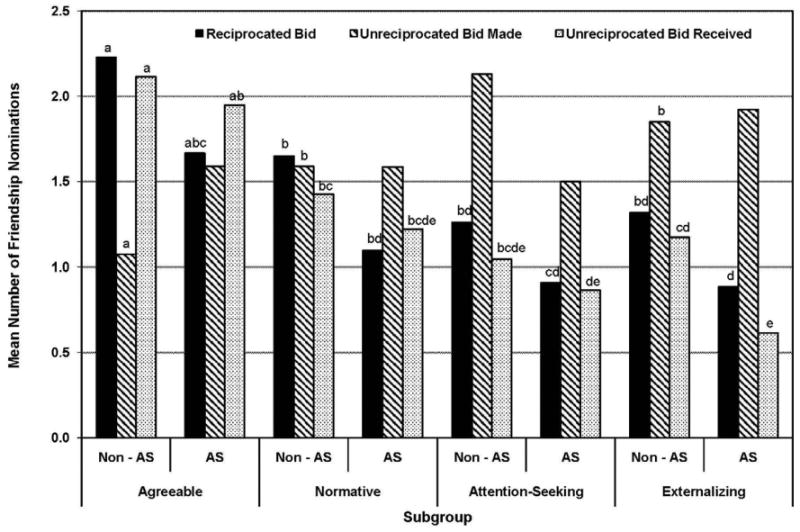

Finally, sociometric friendship nominations indicated that agreeable AS children also fared quite well with dyadic peer relationships. They enjoyed significantly more reciprocated friendships than did externalizing AS children (M = 1.67 vs. 0.88 reciprocated friends). Interestingly, agreeable AS children also received significantly more unreciprocated nominations than did attention-seeking–immature and externalizing AS children (M = 1.95 vs. 0.62 to 0.86 unreciprocated friendship nominations received), indicating that they were considered to be a friend by a relatively large number of children (M = 3.62 total friendship nominations received). Finally, agreeable AS and non-AS children did not differ in friendship reciprocity (M = 1.67 to 1.95 vs. 2.11 to 2.23 for reciprocated friendships and unreciprocated bids received, 1.59 vs. 1.07 for unreciprocated bids made).

Normative Anxious Solitary Children

Normative AS children, particularly boys, experienced moderate peer adversity. Normative AS boys were significantly more rejected than their female counterparts (M = 0.51 vs. −0.06 SD; t = −2.27, p < .05). Similarly, normative AS boys were significantly more rejected than agreeable AS boys (M = 0.51 vs. −0.17 SD) and more excluded, victimized, and unable to defend themselves than normative non-AS boys (M = 0.43 to 0.95 vs. −0.30 to −0.41 SD), whereas normative AS girls did not differ from agreeable AS girls in rejection, exclusion, victimization, or ability to defend themselves (M = −0.06 to 0.55 vs. −0.50 to 0.39 SD), but in comparison to their normative non-AS same-sex counterparts were significantly more excluded and perceived as more unable to defend themselves (M = 0.42 to 0.55 vs. −0.19 to −0.24 SD). See Table 4 and Figure 2.

Normative AS children were also poorly accepted by peers and perceived as low on positive attributes. Normative AS children, relative to agreeable AS children, were significantly less accepted and perceived to be less smart, fun, and good at being leaders (M = −0.50 to −0.64 vs. 0.06 to 0.54 SD). Similarly, normative AS and non-AS children were less accepted and perceived to be less smart, fun, and good at being leaders (M = −0.50 to −0.64 vs. 0.00 to 0.14 SD). See Table 5 and Figure 3.

Recess observations, consistent with peer sociometrics, indicated that normative AS children experienced moderate peer adversity. Normative AS children were marginally more often ignored than were agreeable children (M = 29% vs. 14% of intervals) and marginally less often victimized than externalizing AS children (M =1% vs. 6% of intervals). See Table 6 and Figure 4.

Finally, the quantity of normative AS children's peer friendships appeared moderately restricted. Normative AS children, relative to agreeable non-AS children, had significantly fewer reciprocated friends and were less often the recipient of an unreciprocated friendship bid (M = 1.10–1.22 vs. 2.11–2.23). Thus, although both normative AS and agreeable non-AS children reciprocated about half the friendships bids they received, normative AS children received only about half as many friendship bids (about two vs. four, respectively). See Table 7 and Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Mean number of reciprocated and unreciprocated friendships by subgroup. Subgroups with different superscripts for the same criterion differ from each other at p < .05 or better. This figure corresponds to Table 7. AS = anxious solitary.

Attention-Seeking–Immature Anxious Solitary Children

Sociometrics indicated that attention-seeking–immature AS children experienced highly elevated peer adversity. Attention-seeking– immature AS children of both sexes experienced elevated rejection, exclusion, and victimization and were perceived to be unable to defend themselves (M = 0.75 to 1.85 SD). For attention-seeking–immature AS girls, these differences were significantly elevated relative to both agreeable AS and normative AS girls (M = −0.01 to 0.55 SD). However, for attention-seeking–immature AS boys, these differences were significant only in relation to non-AS groups (normative and sometimes agreeable boys; M = −0.61 to −0.23 SD), except that they were significantly more rejected than agreeable AS boys (M = −0.61 SD). Furthermore, attention-seeking–immature AS and non-AS children were more rejected (boys only), excluded, victimized, and perceived to be unable to defend themselves (M = 0.75 to 1.85 vs. −0.10 to 0.24 SD). See Table 4 and Figure 2. There were no significant sex differences among attention-seeking–immature AS children.

Additionally, peer sociometrics also revealed that attention-seeking–immature AS children were low in peer acceptance and positive attributes. In comparison to agreeable AS children, they were significantly less accepted and perceived by peers as less smart, fun, and less good at being leaders (M = −0.84 to −0.69 vs. 0.06 to 0.54 SD). Attention-seeking–immature AS and non-AS children were significantly less accepted (M = −0.84 vs. −0.03 SD) but did not differ in regard to other positive attributes (M = −0.69 to −0.71 vs. −0.15 to −0.38 SD). See Table 5 and Figure 3.

Furthermore, recess observations indicated that attention-seeking–immature AS children were often ignored (M = 29% of intervals) and seldom actively accepted (M = 34% of intervals) by peers (significant differences relative to agreeable and externalizing children; Ms = 13%–14% for ignore and 55%–56% for acceptance). Although they experienced a moderate level of victimization (M = 3% of intervals), levels were not significantly different from other groups. These observational results are compatible with sociometric results in indicating that these children experience heightened peer adversity, but more clearly indicate that these children more often experience exclusion than victimization. See Table 6 and Figure 4. Interestingly, these observations also revealed that attention-seeking–immature AS children displayed particularly high rates of alone-directed behavior— marginally more than externalizing children (M = 25% vs. 6% of intervals). See Table 6 (Figure 4 depicts peer treatment but not alone-directed behavior).

Attention-seeking–immature AS children also demonstrated moderate difficulty with peer friendships. They had significantly fewer reciprocated friends than did normative and agreeable children (M = 0.91 vs. 1.65 to 2.23 reciprocated friends) and received significantly fewer unreciprocated friendship bids than did both agreeable AS and agreeable children (M = 0.86 vs. 1.95 to 2.11 unreciprocated friendship bids received). See Table 7 and Figure 5.

Externalizing Anxious Solitary Children

Sociometrics indicated that externalizing AS children were highly rejected, excluded, victimized, and unable to defend themselves. For externalizing AS girls, these differences were significantly elevated relative to both agreeable AS and normative AS girls (M = 1.63 to 2.28 vs. −0.50 to 0.42 SD), except that inability to defend oneself was significant relative only to non-AS girls (agreeable and normative girls; M = 1.43 vs. −0.24 to −0.28 SD). For externalizing AS boys, these differences were significantly elevated relative to normative non-AS boys (M = 1.25 to 1.81 vs. −0.30 to −0.41 SD), except that externalizing AS boys were also significantly more rejected than agreeable AS boys (M = 1.32 vs. −0.17 SD). Furthermore, externalizing AS versus non-AS children were significantly more rejected (girls only), excluded, victimized, and perceived to be unable to defend themselves (M = 1.32 to 2.28 vs. −.15 to .72 SD). See Table 4 and Figure 2. There were no significant sex differences among externalizing AS children in peer difficulties.

Peers also reported that externalizing AS children were not liked and were low in positive attributes. Externalizing AS children, compared with agreeable AS children, were significantly less accepted and perceived as being less smart, fun, and good at being leaders (M = −0.42 to −0.09 vs. 0.06 to 0.54 SD). Furthermore, externalizing AS versus non-AS children were significantly less accepted and perceived to be less fun and not as good at being leaders but did not differ in perceived smartness (M = −0.59 to −0.92 vs. −0.09 to −0.42 SD). See Table 5 and Figure 3.

Recess observations, similar to sociometric data, indicated heightened peer adversity for externalizing AS children, but there were differences in the form of adversity. Observations revealed that externalizing AS children, in comparison to normative AS and agreeable AS children, were significantly more often victimized by peers (M = 6% vs. 1% of intervals). Thus, recess observations were consistent with sociometric data in indicating that externalizing AS children experienced high peer victimization, but indicated that they did not experience significantly more elevated exclusion relative to other groups. See Table 6 and Figure 4.

Externalizing AS children also did not fare well with peer friendships. They had fewer reciprocated friends and received fewer unreciprocated friendship bids than agreeable AS children (M = 0.62–0.88 vs. 1.67–1.95 friends). Thus, externalizing AS children received an average of only 1.5 friendship bids (both reciprocated and unreciprocated), fewer than one of which was reciprocated. Finally, externalizing AS and non-AS children received significantly fewer unreciprocated friendship bids (M = 0.62 vs. 1.17 friendship bids) but otherwise did not differ in friendship reciprocity. See Table 7 and Figure 5.

Effect Sizes

Not only were differences among subgroups statistically significant, but most group effects were of medium to large effect size as indicated by partial eta-square (see Tables 3–7). Partial eta-square indicates the percentage of variance in the dependent variable (e.g., exclusion) accounted for by the unique effect of the independent variable (behavioral group) after accounting for variance accounted for by other independent variables in the model (sex and Behavioral Group × Sex interaction). Partial eta-square ranges from 0 to 1, with larger numbers indicating more percentage of variance accounted for. Eta-square sizes of .01 are considered small; .06, medium; and .14, large. Even though these guidelines are considered too large for partial eta-square, most of the effect sizes obtained were medium to large, according to these criteria. Effect sizes were particularly large for peer adversity, with subgroup effects for both boys and girls accounting for around 40% of the unique variance in sociometric peer rejection, exclusion, and victimization.

Discussion

Results challenge the notion that AS children can be adequately characterized as a unitary group who experience peer adversity. When AS is placed in the context of other social behaviors, both high- and low-functioning profiles emerge. Agreeable AS children (particularly girls) exhibit superior relational adjustment, and behaviorally normative AS, attention-seeking–immature AS, and externalizing AS children exhibit increasing degrees of relational maladjustment. Although both attention-seeking-immature and externalizing AS children experienced high peer adversity, this adversity differed in kind.

Agreeable Anxious Solitary Children

Agreeable AS children are not adequately characterized when they are pooled with other AS children in studies reporting relational difficulties for “average” AS children. Agreeable AS children, particularly girls, experienced low peer rejection, exclusion, and victimization. Moreover, agreeable AS children demonstrated markedly positive peer relations (e.g., above average acceptance). Peers also reported that they displayed desirable social characteristics (above average fun and leadership).

However, the most striking asset of agreeable AS children was perceived intelligence. Peers clearly perceived these children as intelligent and academically successful in school, in contrast to all other AS subgroups. These findings are consistent with studies of resilient children that have indicated that high intelligence is one of the most robust predictors of positive development among behaviorally vulnerable children (Luthar & Zigler, 1992; Masten et al., 1999) and extend these finding by indicating that perceived intelligence appears to buffer risk not only for externalizing children (as evidence has indicated in the past), but also for anxious children. There are several potential sources of this linkage between agreeable and intelligent characteristics. It is possible that an agreeable outlook promotes children's engagement in learning or that both characteristics are supported by responsive parenting. These possibilities should be testable in future research.

Also, agreeable AS children were among those who had relatively high numbers of reciprocated friendships (an average approaching two) and, similar to agreeable non-AS children, received a relatively large number of friendship bids that they did not reciprocate (an average of almost two). Although receiving friendship bids that one does not reciprocate may not appear to fulfill the relational ideal of reciprocity, children who received a relatively large number of unreciprocated bids across subgroups were characterized by agreeableness or behavioral normativeness. Thus, receiving unreciprocated bids does not appear to be indicative of relational problems. Rather, it may indicate that such children are considered to be friends by a relatively large number of children but are perhaps modest or conservative in the number of children they recognize as close friends in return.