Abstract

Risk of cancer increases with age; and socioeconomic factors have been shown to be relevant for (predictive of) cancer risk-related behaviors and cancer early detection and screening. Yet, much of this research has relied on traditional measures of socioeconomic status (SES) to assess socioeconomic circumstances, which limits our understanding of the various pathways through which the socioeconomic environment affects cancer risk. Research on hardship and health suggests that concepts of financial hardship can uncover socioeconomic factors influencing health behaviors over and above traditional SES measures. Thus, consistently including measures of financial hardship in cancer prevention research and practice may help us further explicate the pathway between socioeconomic circumstances and cancer risk-related behaviors and cancer screening among older adults and help us identify intervention and policy targets. We present a conceptual model of financial hardship that can be applied to cancer prevention research among older adults to provide guidance on the conceptualization, measurement, and intervention on financial hardship in this population. The conceptual model advances a research agenda that calls for greater conceptual and measurement clarity of the material, psychosocial, and behavioral aspects of the socioeconomic environment to inform the identification of potentially modifiable socioeconomic factors associated with cancer risk-related behaviors among older adults.

Keywords: Socioeconomic status, Financial distress, Social determinants of health

Cancer is a family of many diseases caused by different factors across multiple levels (e.g., individual, societal, and environmental) operating synergistically over years, progressing in distinct stages (Ecsedy & Hunter, 2008). Though cancer can occur at any age (National Cancer Institute (NCI), 2015), the risk of cancer incidence and mortality increases with age; and 55% of all cancers (other than nonmelanoma skin cancer) occur in those aged at least 65 years, 28% occur in those aged 65–74 years, 19% occur in those aged 75–84 years, and 8% occur in those aged 85+ years (US Cancer Statistics Working Group, 2017). By the year 2030, 20% US population will be more than the age of 65 years, and the population of those aged 85 years and older will double, from 4 million to more than 8 million (Ortman, Velkoff, & Hogan, 2014). To address this substantial population shift, primary and secondary efforts to prevent cancer (e.g., screening) among older adults are critical for the quality of life of this population, and for mitigating the burden this population shift will have on US households and the health care system (Bellizzi, Mustian, Palesh, & Diefenbach, 2008).

Cancer Risk-Related Behaviors and Socioeconomic Status

Engaging in cancer-preventive behaviors has been shown to be socioeconomically patterned across the life course (Ward et al., 2004). Research has shown a negative correlation between socioeconomic status (SES; household income, educational attainment, and employment status) and cancer risk factors such as physical inactivity behavior, smoking status, and obesity (Link, Northridge, Phelan, & Ganz, 1998), and a positive correlation with access to and use of screening behaviors for breast, colon, cervical, and prostate cancers (Drake, Lathan, Okechukwu, & Bennett, 2008; Link et al., 1998). However, the mechanisms through which SES influences cancer risk remain understudied, and the limited scope of extant SES measures is not adequately capturing socioeconomic circumstances or the many pathways by which socioeconomic circumstances may influence health behaviors (Oakes & Rossi, 2003). Although SES is often conceptualized as a multidimensional construct, it is usually measured by a single indicator (Braveman et al., 2005). Yet, no single indicator of SES adequately captures the many aspects of the socioeconomic context that influence cancer risk (Ma, Ward, Siegel, & Jemal, 2015). There is also evidence that traditional measures of SES may not be equivalent across racial/ethnic groups (Shavers, 2007). In addition to the issues with explicating the socioeconomic context where cancer risk-related behaviors take place, cancer prevention strategies for older adults are complex because of issues related to comorbidities, mobility, and lack of access to geriatric specialists, and whether the preventive effort will improve the quality of life and extend survival (Dunn, Greenwald, & Anderson, 2012).

The primary theory guiding much of the recent research on the association between socioeconomic circumstances and health/health behavior is the “fundamental causes theory” (Link & Phelan, 1995). This theory suggests that resources such as “money, knowledge, prestige, power, and beneficial social connections” (Phelan, Link, & Tehranifar, 2010) are sorted by socioeconomic position; and these resources create the social context where health behaviors (acquisition and cessation) are implemented and our health status produced. In creating this context, the resources (or lack of such resources) are the factors that put people at risk of (e.g., cancer) risk. To address the fundamental causes in cancer prevention intervention research, Sorensen and colleagues (2003) put forth a framework for incorporating the socioeconomic context in cancer risk-related behavior interventions (Sorensen et al., 2003). Their framework suggests that it is necessary to understand how SES structures the patterns of social circumstances and the resources available in the target population when developing cancer prevention interventions/policies. Such an approach requires an explication of socioeconomic circumstances not only to understand the financial resources available but also to discern the financial worries that arise from one’s socioeconomic position.

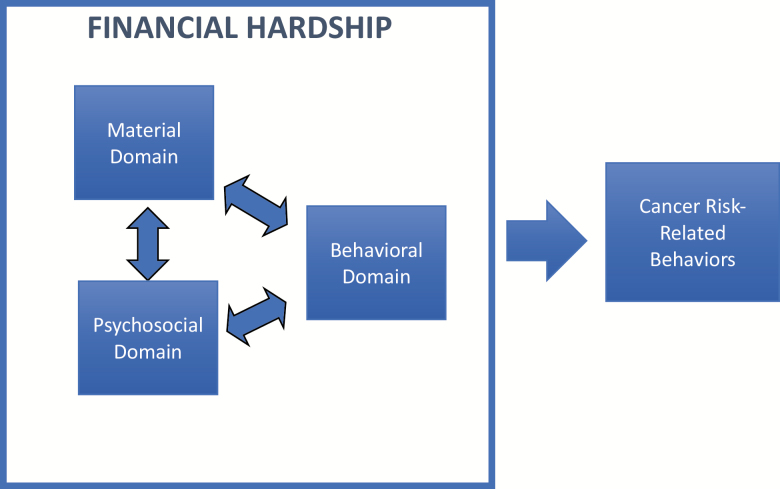

To operationalize the social circumstances and the resources available in the framework of Sorensen and colleagues (2003), we suggest cancer prevention researchers and practitioners complement traditional SES measures with measures of financial hardship. The objective of the following discussion was to put forth a conceptual model of financial hardship previously introduced in cancer survivorship research (Altice, Banegas, Tucker-Seeley, & Yabroff, 2017; Tucker-Seeley & Yabroff, 2016; Yabroff, Zhao, Zheng, Rai, & Han, 2018) to be applied to cancer prevention research and practice. This model, which builds on theoretical work in the health disparities literature (Bartley, 2004), sorts and characterizes concepts used to describe the financial hardship experience following cancer diagnosis into three domains: material, psychosocial, and behavioral. We contend that the application of this conceptual model to cancer prevention research and practice among older adults can guide efforts for targeted intervention development on the socioeconomic factors most influencing acquisition and cessation of cancer risk-related behaviors and cancer screening behaviors. This conceptual model in the context of cancer prevention among older adults encourages consideration of household financial hardship before engagement with the health care system for cancer care. Although Medicare coverage for older adults is meant to provide protection from financial catastrophe when an illness like cancer presents, research suggests that the exposure to out-of-pocket cost burden can be substantial for families even with Medicare (Davidoff et al., 2013). Thus, understanding household financial hardship before disease diagnosis (i.e., for cancer prevention efforts) can help to elucidate the influence of socioeconomic circumstances as households move across the cancer continuum from prevention to detection/diagnosis and treatment throughout survivorship.

Model of Financial Hardship Applied to Cancer Prevention Research

Cancer prevention research generally uses the traditional measures of SES (income and education) to capture socioeconomic circumstances; however, these traditional measures of SES may not adequately capture the heterogeneity that results from disparate levels of asset accumulation and the differential demands on financial resources across the life course or capture the psychosocial and behavioral components of how SES is experienced. Measures of financial hardship can be used to assess the material and psychosocial aspects of one’s economic situation, capture how well an individual is “economizing” and if s/he has the financial resources to handle unexpected life events (Strumpel, 1976). Familiar financial hardship-related concepts including financial strain, financial satisfaction, and financial distress differ from traditional measures of socioeconomic circumstances such as household income as they capture whether the individual is affording his/her basic necessities, is satisfied with his/her level of financial resources, and whether his/her current level of deprivation is a stressful experience. Research has shown the importance of including financial hardship concepts in studies of the association between socioeconomic circumstances and the health/health behavior of older adults. These studies show that even after adjusting for traditional measures of SES such as educational attainment and income, financial hardship concepts (e.g., financial distress and financial adjustments) remain associated with health/health behavior of older adults, suggesting that over and above these traditional measures of SES, financial well-being exerts an influence on the health/health behaviors of older adults (Advani et al., 2014; Tucker-Seeley, Subramanian, Li, & Sorensen, 2009). This research suggests that interventions/policies designed to address socioeconomic determinants of health behaviors should consider not only traditional aspects of socioeconomic circumstances (e.g., increasing income) but also the psychosocial (e.g., reducing financial distress and worry) and the behavioral (e.g., preventing financial adjustments detrimental to health) aspects of financial hardship.

Domains of Financial Hardship Defined

In the context of cancer prevention, explicating the financial hardship experience can describe the pathway through which socioeconomic resources are marshaled and readied to deploy for acquisition and cessation health behaviors that protect against cancer risk (e.g., engaging in physical activity and quitting smoking). We conceptualize financial hardship across three domains: material, psychosocial, and behavioral (Bartley, 2004). Concepts and measures in the material domain describe and capture the financial resources one has or has access to, and whether individuals report having the financial resources to meet their expenses. The psychosocial domain describes how one feels about those financial resources and can be measured by concepts such as financial satisfaction and financial worry. The behavioral domain describes what one does with their financial resources and is measured by the purposeful efforts households use to economize such as reducing spending on essential/nonessential household goods and postponing/avoiding medical care. The specific correlational association or the directionality among the domains has yet to be specified, and although there is no explicit temporal component in this description of financial hardship, the conceptual model described in the cancer survivorship literature suggests that the behavioral domain is meant to capture the household’s efforts to economize based on their material resources and psychosocial response to those resources following cancer diagnosis. In applying this conceptual model to cancer prevention research and practice among older adults, it is not assumed that the individual/household is responding to the financial burden of a health shock (i.e., cancer diagnosis) but that the material, psychosocial, and behavioral aspects of financial hardship further describe the socioeconomic environment where health behavior decisions to reduce cancer risk are made.

Financial Hardship Among Older Adults

Explicating the financial hardship experience of older adults is not a new endeavor (Cook & Kramek, 1986; Liang, Kahana, & Doherty, 1980). Research in gerontology in general (Kahn & Pearlin, 2006; Liang & Fairchild, 1979; Szanton, Thorpe, & Whitfield, 2010; Tucker-Seeley, Marshall, & Yang, 2016) and in financial gerontology (Cutler, Gregg, & Lawton, 1992) in particular has extensively explored the financial well-being of older adults. This research has generally focused on the relationship among objective and subjective indicators of socioeconomic circumstances, household financial security, quality of life, and physical/mental health in the later stage of the life course. Key findings from this literature suggest that the pathway from individual socioeconomic resources (objective and subjective) to health and well-being is mediated by relative deprivation (Hsieh, 2003). This research also showed that financial hardship and/or financial distress experienced over time is detrimental to the health/well-being of older adults. To build on this previous research effort, we propose the material–psychosocial–behavioral conceptual model of financial hardship to sort and characterize the many terms used to describe financial hardship among older adults; we suggest that the conceptual model in Figure 1 can better guide cancer prevention researchers and practitioners to conceptualize and operationalize the aspects of socioeconomic circumstances that are influencing cancer risk-related behaviors among older adults. Though this discussion is introducing a conceptual model of financial hardship for cancer prevention research efforts among older adults, this model can be applied in defining and measuring financial hardship for cancer prevention research in any adult population. The flexibility of this conceptual model is that within each domain, researchers may decide to include measures of financial hardship relevant to the finances of specific age groups (e.g., managing retirement resources).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of financial hardship.

Financial Hardship Terms Used Interchangeably: Conceptual Clarity Needed

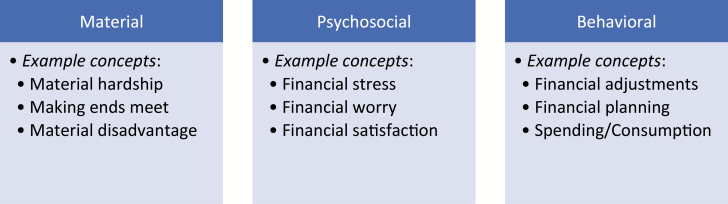

A recent systematic review of financial hardship in the cancer survivorship literature highlighted that many terms (e.g., financial stress, financial worry, financial strain, financial toxicity, and economic burden) are used to capture the financial experience of patients during cancer survivorship (Altice et al., 2017). There is similar inconsistency in the cancer prevention and gerontology literatures in the interchangeable use of financial hardship concepts (e.g., perceived adequacy of resources, financial hardship, economic strain, and financial worry); and what is missing from these research literatures is an overarching framework to sort through the many concepts used to describe financial hardship among older adults. We contend that to guide research on cancer prevention among older adults, the material–psychosocial–behavioral conceptual model can be used to sort financial hardship terms into these three domains (Figure 2); doing so provides some conceptual clarity and consistency to what these terms mean, and it also helps to categorize studies that may use different financial hardship terms but conceptualizing the same experience. More specifically, in applying this conceptual model of financial hardship, the researcher and practitioner consider a priori whether s/he is defining and measuring socioeconomic concepts related to the financial resources the subject has or has access to (material), how the subject feels about those financial resources (psychosocial), and/or what the subject is doing with those financial resources (behavioral).

Figure 2.

Example financial hardship concepts for each domain.

Considering financial hardship concepts across these three domains in cancer prevention research among older adults during the study design phase ensures that barriers (e.g., cost [Holman et al., 2015; Nagelhout, Hogeling, Spruijt, Postma, & De Vries, 2017]) to preventive behaviors are easily identified. In addition, including concepts from each domain also ensures that the specific aspect of financial hardship in one’s socioeconomic environment is targeted in intervention efforts. For example, such specificity allows for the determination of whether the socioeconomic barriers are related to a lack of financial resources the individual has/has access to (material), and/or about how s/he feels about his/her financial resources (psychosocial), and/or what s/he does with his/her financial resources (behavioral). Knowing this can then inform whether a cancer risk-related behavior intervention addresses these barriers by increasing financial resources available to the individual, and/or by focusing on addressing the feelings/emotions related to his/her finances, and/or by focusing on what s/he does with (how s/he manages or makes adjustments to) his/her financial resources.

Conclusion and Next Steps

Using a material–psychosocial–behavioral conceptual model of financial hardship to select concepts for measurement in cancer prevention research and practice among older adults not only further explicates the socioeconomic determinants of cancer risk-related behaviors in this population but the model also provides conceptual clarity to areas of research that have used many of the financial hardship concepts interchangeably. In so doing, comparing across studies using concepts such as financial hardship, financial distress, and financial adjustments is challenging in cancer prevention research because, for example, it remains unclear if the socioeconomic factor influencing acquisition or cessation health behaviors is related to the financial resources the subject has/has access to, how s/he feels about those financial resources, and/or what s/he does to economize his/her financial resources. In addition, using the material–psychosocial–behavioral conceptual model of financial hardship provides guidance for designing targeted intervention focused on specific socioeconomic barriers among older adults for cancer preventive behaviors.

To move the research agenda forward on financial hardship and cancer prevention among older adults, there are several research questions to be explored using the material–psychosocial–behavioral conceptual model of financial hardship. For example, some research questions might include: (1) Are material hardship and financial distress associated with physical inactivity behavior among older adults? (1a) Are there racial/ethnic differences in this association? (1b) Is the association between material hardship and physical inactivity mediated by financial distress? (2) Is financial worry associated with cancer screening behavior or smoking behavior?

By including measures of financial hardship in cancer prevention research and practice among older adults, we can begin to unpack the complex ways in which socioeconomic circumstances are differentially experienced across demographic groups; more specifically, using the material–psychosocial–behavioral conceptual model of financial hardship described in this discussion may help to better understand how such experiences contribute to disparate health behaviors and health outcomes across socioeconomic and racial/ethnic groups.

The obvious next question is, “what do cancer prevention researchers and practitioners do after they find material, psychosocial, or behavioral financial hardship associated with cancer risk-related behaviors?” Although there is not a large body of research evidence on financial hardship interventions to address cancer risk-related behaviors, an example of a program in Delaware showed that when financial barriers were eliminated for colorectal cancer screening, the rates of screening for state residents aged 50 and older increased from 57% in 2002 to 74% in 2009 and racial/ethnic disparities in screening rates were eliminated (Grubbs et al., 2013). Yet, for cancer risk-related behaviors such as physical inactivity and smoking, the most appropriate financial hardship-related intervention/policy remains unclear. Therefore, more research to further elucidate the material–psychosocial–behavioral financial hardship of older adults can help cancer prevention researchers uncover the socioeconomic factors amenable to intervention that can potentially facilitate behavior change.

Yabroff and colleagues (2018) recently highlighted the many gaps in research on financial hardship among cancer survivors and the factors at multiple levels associated with financial hardship, where the multiple levels included individual patient/caregiver, health care team, health care system, and employer-related factors and state and federal policy levels (Yabroff et al., 2018). Many of the gaps noted by Yabroff and colleagues (2018) are relevant for the application of material, psychosocial, and behavioral financial hardship in cancer prevention research; specifically, they noted the lack of standard measures for financial hardship across the three domains of financial hardship, the few intervention studies focused on reducing financial hardship, and the need to focus on the influence of financial hardship at multiple levels, beyond the individual. This suggests that additional research is needed on financial hardship across the cancer continuum (i.e., from prevention to survivorship) and encourages a social–ecological approach that explores the various multilevel pathways through which material, psychosocial, and behavioral financial hardships influence cancer-related outcomes among older adults.

Funding

Dr. Tucker-Seeley was supported by a National Cancer Institute, K01 Career Development Grant (K01 CA169041). Dr. Thorpe was supported by National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (U54MD000214) and the National Institute on Aging (K02AG059140 and R01AG054363). This paper was published as part of a supplement sponsored and funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Advani P. S., Reitzel L. R., Nguyen N. T., Fisher F. D., Savoy E. J., Cuevas A. G., … McNeill L. H (2014). Financial strain and cancer risk behaviors among African Americans. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention, 23, 967–975. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altice C. K., Banegas M. P., Tucker-Seeley R. D., & Yabroff K. R (2017). Financial hardships experienced by cancer survivors: A systematic review. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 109, 1–17. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartley M. (2004). What is health inequality? In Health Inequality: An introduction to theories, concepts, and methods (pp. 1–21). Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bellizzi K. M., Mustian K. M., Palesh O. G., & Diefenbach M (2008). Cancer survivorship and aging: Moving the science forward. Cancer, 113, 3530–3539. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P. A., Cubbin C., Egerter S., Chideya S., Marchi K. S., Metzler M., & Posner S (2005). Socioeconomic status in health research: One size does not fit all. JAMA, 294, 2879–2888. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.22.2879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook F. L., & Kramek L. M (1986). Measuring economic hardship among older Americans. The Gerontologist, 26, 38–47. doi:10.1093/geront/26.1.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler N. E., Gregg D. W., & Lawton M. P (1992). Aging, money, and life satisfaction: Aspects of financial gerontology. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff A. J., Erten M., Shaffer T., Shoemaker J. S., Zuckerman I. H., Pandya N., … Stuart B (2013). Out-of-pocket health care expenditure burden for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. Cancer, 119, 1257–1265. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake B. F., Lathan C. S., Okechukwu C. A., & Bennett G. G (2008). Racial differences in prostate cancer screening by family history. Annals of Epidemiology, 18, 579–583. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn D. K., Greenwald P., & Anderson D. E (2012). Overview of cancer prevention strategies in older adults. In Bellizzi K. M. & Gosney M. A. (Eds.), Cancer and aging handbook: Research and practice (pp. 55–70). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Ecsedy J., & Hunter D (2008). The origin of cancer. In Adami H.-O., Hunter D. J., & Trichopoulos D. (Eds.), Textbook of cancer epidemiology (pp. 61–65). USA: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grubbs S. S., Polite B. N., Carney J. Jr, Bowser W., Rogers J., Katurakes N., … Paskett E. D (2013). Eliminating racial disparities in colorectal cancer in the real world: It took a village. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 31, 1928–1930. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.8412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holman D. M., Berkowitz Z., Guy G. P. Jr, Hawkins N. A., Saraiya M., & Watson M (2015). Patterns of sunscreen use on the face and other exposed skin among US adults. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 73, 83–92.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh C. M. (2003). Income, age and financial satisfaction. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 56, 89–112. doi: 10.2190/KFYF-PMEH-KLQF-EL6K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn J. R., & Pearlin L. I (2006). Financial strain over the life course and health among older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 47, 17–31. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J., & Fairchild T. J (1979). Relative deprivation and perception of financial adequacy among the aged. Journal of Gerontology, 34, 746–759. doi:10.1093/geronj/34.5.746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J., Kahana E., & Doherty E (1980). Financial well-being among the aged: A further elaboration. Journal of Gerontology, 35, 409–420. doi:10.1093/geronj/35.3.409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link B. G., Northridge M. E., Phelan J. C., & Ganz M. L (1998). Social epidemiology and the fundamental cause concept: On the structuring of effective cancer screens by socioeconomic status. Milbank Quarterly, 76, 375–402, 304. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link B. G., & Phelan J (1995). Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 35(Extra Issue), 80–94. doi:10.2307/2626958 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Ward E., Siegel R., & Jemal A (2015). Temporal trends in mortality in the united states, 1969–2013. JAMA, 314, 1731–1739. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagelhout G., Hogeling L., Spruijt R., Postma N., & de Vries H. 2017. Barriers and facilitators for health behavior change among adults from multi-problem households: A qualitative study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 14, 1229. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14101229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute (NCI) (2015). Age and cancer risk Retrieved from www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/age

- Oakes J. M., & Rossi P. H (2003). The measurement of SES in health research: Current practice and steps toward a new approach. Social Science and Medicine (1982), 56, 769–784. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00073-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortman J. M., Velkoff V. A., & Hogan H (2014). An aging nation: The older population in the United States. US: United States Census Bureau, Economics and Statistics Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan J. C., Link B. G., & Tehranifar P (2010). Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: Theory, evidence, and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51 (Suppl), S28–S40. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavers V. L. (2007). Measurement of socioeconomic status in health disparities research. Journal of the National Medical Association, 99, 1013–1023. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen G., Emmons K., Hunt M. K., Barbeau E., Goldman R., Peterson K., … Berkman L (2003). Model for incorporating social context in health behavior interventions: Applications for cancer prevention for working-class, multiethnic populations. Preventive Medicine, 37, 188–197. doi:10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00111-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strumpel B. (1976). Economic means for human needs: Social indicators of well-being and discontent. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Szanton S. L., Thorpe R. J., & Whitfield K (2010). Life-course financial strain and health in African-Americans. Social Science and Medicine (1982), 71, 259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker-Seeley R. D., Marshall G., & Yang F (2016). Hardship among older adults in the HRS: Exploring measurement differences across socio-demographic characteristics. Race and Social Problems, 8, 222–230. doi:10.1007/s12552-016-9180-y [Google Scholar]

- Tucker-Seeley R. D., Subramanian S. V., Li Y., & Sorensen G (2009). Neighborhood safety, socioeconomic status, and physical activity in older adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37, 207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker-Seeley R. D., & Yabroff K. R (2016). Minimizing the “Financial toxicity” associated with cancer care: Advancing the research agenda. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 108, 2015–2017. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Cancer Statistics Working Group (2017). United States cancer statistics: 1999–2014 incidence and mortality web-based report. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/uscs/index.htm [Google Scholar]

- Ward E., Jemal A., Cokkinides V., Singh G. K., Cardinez C., Ghafoor A., & Thun M (2004). Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 54, 78–93. doi:10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabroff K. R., Zhao J., Zheng Z., Rai A., & Han X (2018). Medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States: What do we know? What do we need to know? Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention, 27, 1389–1397. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]