Abstract

Addressing stigma remains a pressing HIV priority globally. We examined whether stigma-related experiences were associated with lower social support and greater psychological distress among young Black men who have sex with men (YBMSM). YBMSM (ages 18–30; N=474) completed an in-person baseline survey and reported their experiences of externalized stigma (i.e., racial and sexuality discrimination), internalized stigma (i.e., homonegativity), social support, and psychological distress (i.e., anxiety and depression symptoms). We used structural equation modeling to test the association between stigma and psychological distress, and examined whether social support mediated the relationship between stigma and psychological distress. Recognizing that these associations may differ by HIV status, we compared our models by self-reported HIV status (N=275 HIV-negative/unknown; N=199 living with HIV). Among seronegative/serounknown YBMSM, internalized and externalized stigma were positively associated with psychological distress, and diminished the protective effect of social support on psychological distress. Among YBMSM living with HIV, externalized stigma was associated with greater anxiety symptoms and diminished social support. Internalized stigma was not associated with social support or psychological distress. Our findings suggest that YBMSM who experience stigma are more vulnerable to psychological distress and may have diminished buffering through social support. These effects are accentuated among YBMSM living with HIV, highlighting the need for additional research focused on the development of tailored stigma reduction interventions for YBMSM.

Keywords: Depression, Anxiety, Structural equation modeling, Racial/ethnic minority, LGBT

Introduction

Men who have sex with men (MSM) account for most new HIV infections in the United States, with young Black MSM (YBMSM) experiencing steep disparities in HIV incidence and HIV care outcomes when compared to Non-Hispanic White MSM (Holtgrave et al., 2014; Matthews et al., 2016; Sullivan et al., 2015). These disparities are often caused and amplified by the presence of structural inequities in YBMSM’s lives (Millett, Flores, Peterson, & Bakeman, 2007; Sullivan et al., 2014). For instance, YBMSM not only contend with negative societal reactions to their sexual orientation, but also may experience limited acceptance within their own cultural community and racial prejudice in society more broadly (Maulsby, Millett, Lindsey, Kelley, Johnson, Montoya & Holtgrave, 2014). Research examining how these experiences of stigma affect the health and well-being of YBMSM often employ single-axis perspectives (i.e., focusing on either race, sexuality, or HIV) to understand these associations, limiting our ability to understand how these experiences intersect (see Bowleg et al., 2017 for a review). Researchers, advocates, and policy-makers have recognized that intersectional stigma-related processes must be addressed directly if we are to reduce YBMSM’s psychosocial vulnerability to HIV-related risk correlates (e.g., psychological distress) and improve their outcomes across the HIV prevention and care continuum (Eaton et al., 2015; Grossman et al., 2011; Kalichman, Katner, Banas, & Kalichman, 2017).

YBMSM often are subjected to complex and synergistic discriminatory experiences due to their race, sexuality, and (presumed) HIV status (Earnshaw & Chaudoir, 2009; Earnshaw, Smith, Chaudoir, Amico, & Copenhaver, 2013; Earnshaw, Smith, Cunningham, & Copenhaver, 2015; Turan et al., 2017). These experiences may manifest as externalized (e.g., discriminatory events in everyday life) and internalized (e.g., internalized homonegativity) stigma, and may be particularly salient for YBMSM given their dual racial and sexual minority identities. As significant stressors in the lives of YBMSM, these stigma can intensify psychological distress (e.g., symptoms of depression and anxiety) and undermine the health of YBMSM. Therefore, building on the role of stigma as a fundamental cause of health disparities (Hatzenbuehler, O’Cleirigh, Mayer, Mimiaga, & Safren, 2011), we sought to characterize how YBMSM’s experiences of stigma were associated with symptoms of psychological distress (e.g., depression and anxiety). We focus on psychological distress as the primary outcome of this study given its robust association with numerous HIV-related prevention and care outcomes (Grossman, Purcell, Rotheram-Borus, & Veniegas, 2013; Nanni, Caruso, Mitchell, Meggiolaro, & Grassi, 2015).

Social support can mitigate how stigmatizing events affect psychological distress. In his seminal work on the stress-buffering hypothesis, Cohen (1988, 2004) noted that social support could buffer the effects that stressors had on psychological well-being through two pathways. The first pathway (i.e., direct effect) posits that social support directly improves psychological well-being by promoting positive affect and increasing individuals’ sense of self-worth and kinship. The second pathway (i.e., indirect effect) suggests that social support can mitigate the magnitude that a stressor can have on an individuals’ well-being (Rueger, Malecki, Pyun, Aycock, & Coyle, 2016). In prior studies, researchers have found a strong inverse association between social support and psychological distress among racial/ethnic MSM (Latkin et al., 2017; Wong et al., 2014; Yang, et al, 2013). Social support has also been implicated in decreased risk of seroconversion among Black MSM (Hermanstyne et al., 2018). From a fundamental cause perspective (Hatzenbuehler, Phelan, & Link, 2013), however, stigma can erode the availability and enactment of social support within YBMSM’s networks and limit the potential for social supports to buffer the impact of stigma on psychological distress. Therefore, it is imperative to understand whether YBMSM’s experiences of stigma are associated with less social support, thereby indirectly contributing to increased psychological distress.

The challenges of living with HIV may further exacerbate experiences of stigma and social isolation, and accentuate the relationships between stigma, social support, and psychological distress among YBMSM (Maulsby et al., 2014). In prior research, YBMSM living with HIV reported challenges in establishing social networks and gaining social support due to their sexual orientation and HIV status (Garcia et al., 2016). Similarly, in a study of youth living with HIV, sexual minority youth were more likely than heterosexual counterparts to have low social support, which was correlated with greater number of mental health symptoms (Lam et al., 2007). In light of these prior findings, we examined whether the experiences of stigma and their association to psychological distress differed by HIV status, in part due to an erosion in the perceived availability of social support in YBMSM’s lives.

The primary goal of this report is to examine the association between stigma, social support, and psychological distress in a sample of YBMSM. Our study has three primary objectives. The first objective was to test the direct associations between psychological distress (e.g., symptoms of depression and anxiety) and internalized (e.g., internalized homonegativity) and externalized (e.g., sexual and racial discrimination) stigma. Consistent with prior research, we hypothesized that internalized and externalized stigma would be independently and positively associated with psychological distress. The second objective sought to examine whether YBMSM’s experiences of stigma were directly associated with their perceived availability of social support, and indirectly associated with psychological distress through social support. Consistent with prior research and the stress-buffering hypothesis, we hypothesized that social support would be negatively associated with psychological distress (main effect) and would also serve to buffer the relationship between stigma and well-being (indirect effect). Finally, in our third objective, we explored whether the proposed associations between stigma, social support, and psychological distress varied based on participants’ self-reported HIV status. We hypothesized that YBMSM living with HIV would benefit less from the protective factors of social support than their seronegative peers.

Methods

Sample

A randomized controlled trial comparing an online HIV intervention that included information, interactive skills-based activities, and connections with other participants through structured social networking forums to a control website that provided information about HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STI) enrolled 474 YBMSM between November 2013 and October 2015. Participants completed an online baseline survey at an in-person enrollment visit and three online follow-up assessments (3 (intervention completion), 6 and 12-months) post enrollment. Study eligibility criteria at enrollment were: (1) age 18 to 30 (inclusive); (2) born biologically male; (3) self-identify as Black or African American; (4) currently reside in North Carolina; and (5) currently have access to a mobile device (e.g. smartphone, tablet) that connects to the internet. Participants also had to self-report any of the following in the past six months: (a) condomless anal sex with a male partner, (b) any anal sex with more than three male sex partners, (c) exchange of money, gifts, shelter, or drugs for anal sex with a male partner, or (d) anal sex while under the influence of drugs or alcohol (i.e., high or drunk within two hours of sex). This analysis focuses on baseline data for the 474 participants who enrolled in the study.

Social media advertisements and targeted messages were posted on websites, including Craigslist, relevant Facebook groups, and Grindr. Participants were also recruited through word of mouth and flyers at local case management organizations, and HIV/STI clinics. Study flyers inviting individuals to participate were also posted at local college campuses and previously identified venues (bars, clubs, coffee shops) frequented by YBMSM.

Procedures

Eligible participants were scheduled to attend an in-person visit where they were consented and enrolled in the study. Participants then completed a computer-assisted, multi-domain baseline survey that took on average 45 to 60 minutes. Participants received $50 for completing the baseline survey. The (blinded) Institutional Review Board approved this project.

Measures

Depression symptoms.

Depression symptoms were assessed using the validated Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). The 21 items include symptoms of depression (e.g., “I was bothered by things that don’t usually bother me”) during the past week. Responses were on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = Rarely or none, 3 = All of the time). Positively worded items were reverse coded. Participants’ depression scores were a sum score of the 21 items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80). For structural equation modeling (SEM) analyses, we created three parcels to serve as indicators of the depression latent score.

Anxiety symptoms.

Anxiety symptoms were measured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) 7-items subscale of the Patient Health Questionnaire (Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Lowe, 2006). The seven items measured symptoms of anxiety (e.g., “Being so restless that it is hard to sit still”) in the past two weeks using a 4-point scale (1 = Not at all, 4 = Nearly every day). Anxiety scores were a mean composite of the items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93). Each item was used as an indicator to create the anxiety latent score in our SEM analyses.

Social Support.

We used the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS; Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991) to measure participants’ perceived availability of social support. The MOS has four subscales that examine the functional support characteristics in participants’ social networks: informational/emotional (8 items; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.97), tangible (4 items; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92), and affectionate support (3 items; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94), as well as positive social interactions (4 items Cronbach’s alpha = 0.97). Each item is scored on a 5-point scale (1=None of the time, 5=All of the time). We created mean scores for each subscale and then summed them to create a total social support score (Cronbach’s alpha=.93). In our SEM analyses, we used each subscale as an indicator of the social support latent construct.

Internalized Homonegativity.

We used a 5-item internalized homonegativity scale as our proxy measure for internalized stigma (Herek et al., 1997). An example item includes, “I feel that being gay/bisexual is a personal shortcoming for me.” Item responses were assessed on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree). The internalized homonegativity scale yielded high reliability in our sample (Cronbach’s alpha = .87).

Racial and Sexual Discrimination.

We measured participants’ experiences of multiple discrimination due to their sexuality and race (Bogart, Wagner et al., 2010). For each identity, participants answered 10 statements related to discriminatory experiences (0=No, 1=Yes) in the prior year (e.g., “Treated with hostility/coldness by strangers because of your race/ethnicity”; “Personal property damaged/stolen because of your sexual identity”. We created a summed score for both discrimination scales (Cronbach’s alpha = .88 for racial discrimination; Cronbach’s alpha = .88 for sexuality discrimination). Given prior research suggesting multiple discrimination based on sexuality and race among Black MSM (Bogart, Wagner, Galvan, Landrine, Klein & Sticklor, 2011), we examined the correlation between these two discrimination scales. Given the high correlation between the scales (r=.57; p<.001), we created an externalized stigma latent construct using both discrimination scales as indicators in our subsequent SEM analyses.

HIV Status.

Participants were asked to report whether they had ever tested for HIV. Those reporting prior testing were asked to report the result of their last test. Participants who reported being HIV-negative and/or not having ever tested for HIV were collapsed into one grouping variable (0=HIV negative/unknown; 1=Living with HIV).

Data Analytic Strategy

We used EQS version 6.1 (Bentler, 2004) to construct our structural equation models (SEM). Contrary to regression or other methods, the SEM approach allowed us to test our two endogenous latent factors (e.g., anxiety and depression) simultaneously (Klem, 2000), and to examine the direct and indirect structural path models between our latent constructs (Bedeian, Day, Kelloway, 1997). Our estimation of model coefficients was improved by using an estimated covariance matrix generated from the variables’ observed covariance matrix. The comparisons between the observed and estimated covariance matrices provided overall goodness-of-fit measures, allowed for model modifications, and provided a straightforward approach for group comparisons.

We present our findings following Raykov, Tomer, and Nessel’s (1991) proposed guidelines for adequate reporting of structural equation modeling and provide three goodness-of-fit indices: Bentler-Bonnet’s Normed Fit Index (NFI), Bentler-Bonnet’s Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI). We also provide information on the root mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) as an index of misfit (Boomsma, 2000). Hu & Bentler (1999) suggest values of .90 or higher among fit indices and values of .06 or lower for RMSEA as acceptable indications of well-fitting models. We used the maximum-likelihood (ML) solution for our model estimation. Consideration was given to potential model modifications suggested by the Lagrange Multiplier Test for adding parameters and the Wald Test for dropping parameters, but we opted to avoid making any changes because they were unsubstantiated by the literature and reduced the likelihood of capitalizing on chance (Kline, 1998).

Results

Sample Description

Participants’ mean age was 24.33 (SD=3.21 years), with YBMSM living with HIV being slightly older (M=24.93, SD=3.12) than their peers who were HIV negative/serounknown (M=23.90, SD=3.22; t(471)=3.50, p<.001). Nearly two thirds of the sample self-identified as gay (n=310; 65.4%), with others identifying as bisexual (n=86; 18.1%), queer (n=7; 1.5%), questioning (n=10; 2.1%), straight (n=8; 1.7%), or some other category (e.g., “being myself”; “curious”, “demisexual”, “human”; n=53; 11.2%). We observed no differences by HIV status in participants’ sexual orientation identity.

Over a fifth of the sample (21.9%) reported experiencing homelessness in the prior six months (see Table 1), with YBMSM living with HIV being more likely to report recent homelessness (33.2%) than their peers who self-reported as HIV negative/serounknown (13.8%), X2(N=474, df=1)=25.23, p<.001). Fifty-percent of the sample was currently enrolled at school, and two-thirds (64.6%) were currently employed.

Table 1.

Descriptive and bivariate comparisons by HIV-status

| Total (N=474) |

HIV-negative (N=275) |

HIV-positive (N=197) |

Test statistic |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 24.33 (3.22) | 23.90 (3.22) | 24.93 (3.12) | 3.50 | .001 |

| Enrolled in School | 237 (50%) | 146 (53.1%) | 91 (45.7%) | 2.50 | .11 |

| Currently Employed | 306 (64.6%) | 187 (68.0%) | 119 (59.8%) | 3.39 | .07 |

| Homeless (prior 6 months) | 104 (21.9%) | 38 (13.8%) | 66 (33.2%) | 25.23 | .001 |

| Internalized homonegativity | 2.32 (1.09) | 2.26 (1.10) | 2.41 (1.08) | 1.42 | .16 |

| Sexuality-related discrimination | 2.42 (2.88) | 2.29 (2.71) | 2.59 (3.10) | 1.06 | .29 |

| Racial discrimination | 2.19 (2.74) | 2.22 (2.64) | 2.14 (2.87) | −.32 | .75 |

| Social Support | 15.42 (4.44) | 15.84 (4.38) | 14.85 (4.46) | −2.39 | .02 |

| Depression | 20.58 (8.19) | 19.52 (7.58) | 22.04 (8.77) | 3.33 | .001 |

| Anxiety | 6.31 (5.93) | 5.75 (5.66) | 7.13 (6.22) | 2.50 | .01 |

In bivariate comparisons (see Table 1), YBMSM living with HIV reported lower social support and greater symptoms of depression and anxiety, respectively, than their counterparts who self-reported as HIV negative/serounknown. There were no mean differences by HIV status for internalized homonegativity, sexuality-related discrimination or racial discrimination.

Testing the measurement model of study variables

Prior to testing our structural models, we proceeded to test the measurement models’ adequacy. Table 2 provides a summary of all study variables’ correlations. The measurement model allowed the ascertainment of the chosen indicators’ appropriateness for the various latent factors in our analyses, with an acceptable fit for the overall sample [χ2(179, N = 454) = 565.20, p < .001; NFI = .91, NNFI = .93, CFI = .94, RMSEA = .07 (CI: 0.06, 0.08)]. Fit was also adequate when stratified by HIV status: HIV-negative/unknown [χ2(179, N = 263) = 372.24, p < .001; NFI = .90, NNFI = .94, CFI = .95, RMSEA = .06 (CI: .05, .07)] and HIV-positive [χ2(179, N = 191) = 350.62 p < .001; NFI = .88, NNFI = .92, CFI = .94, RMSEA = .07 (CI: .06, .08)]. We found our latent factors and indicators had measurement invariance when we compared them between the HIV-negative/unknown and HIV-positive samples; however, proposed direct and indirect pathways varied based on HIV status. Therefore, we present our structural equation models by HIV status below.

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations among variables by HIV status

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Internalized homonegativity | 1 | .187** | .147* | −.174* | .149* | 0.134 |

| 2. Sexuality discrimination | .128* | 1 | .620*** | −.280*** | .347*** | .498*** |

| 3. Racial discrimination | .176** | .530*** | 1 | −.174* | .177* | .271*** |

| 4. Social support | −.197** | −.205*** | −.105 | 1 | −.159* | −.279*** |

| 5. Depression | .164** | .282*** | .235*** | −.188*** | 1 | .645*** |

| 6. Anxiety | .208*** | .233*** | .242*** | −.185*** | .556*** | 1 |

Notes. Top diagonal presents correlations for sample living with HIV. Lower diagonal indicates correlations for HIV-negative and HIV-serostatus unknown sample.

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

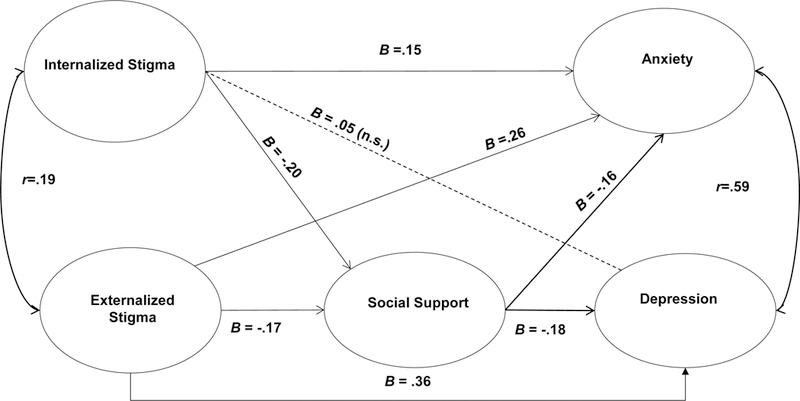

HIV Negative/Serostatus Unknown YBMSM

As shown in Figure 1, greater externalized stigma was associated with higher depression (β=.36, p<.05) and anxiety (β=.26, p<.05) symptoms, and lower social support (β=−.17, p<.05). Internalized stigma was associated with greater anxiety symptoms (β=.15, p<.05) and lower social support (β=−.20, p<.05). We observed no direct association between internalized homonegativity and depression symptoms (β=.05, n.s.). We observed positive correlations between the stigma factors (i.e., internalized and externalized stigma; r=.19, p<.05) and psychological distress factors (i.e., anxiety and depression symptoms; r=.59, p<.05).

Figure 1.

Structural Equation Model for HIV-negative and HIV serounknown YBMSM (N=275)

Social support was associated with lower depression (β=−.18, p<.05) and anxiety (β=−.16, p<.05) symptoms. We then tested for the indirect effects of stigma on psychological distress outcomes through social support (see Table 3). Internalized (β=−.037, p<.05) stigma was indirectly associated with depression symptoms through social support, yet externalized stigma was not. Neither internalized nor externalized stigma were indirectly associated with anxiety symptoms through social support.

Table 3.

Decomposition of Effects for YBMSM

| Outcome | Predictor | Total/Stratified | Total Effects |

Indirect Effects (via social support) |

Direct Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Support | Internalized Stigma | Total sample HIV-negative/unknown sample Sample living with HIV |

−.178* −.202* −.122 |

||

| Externalized Stigma | Total sample HIV-negative/unknown sample Sample living with HIV |

−.229* −.172* −.299 |

|||

| Depression | Internalized Stigma | Total sample HIV-negative/unknown sample Sample living with HIV |

.119* .052 .096 |

.027* .037* .008 |

.092* .015 .088 |

| Externalized Stigma | Total sample HIV-negative/unknown sample Sample living with HIV |

.344* .360* .440* |

.035* .032 .019 |

.309* .328* .421* |

|

| Social Support | Total sample HIV-negative/unknown sample Sample living with HIV |

−.153* −.183* −.065 |

|||

| Anxiety | Internalized Stigma | Total sample HIV-negative/unknown sample Sample living with HIV |

.147* .151* .049 |

.031* .032 .020 |

.116* .119 .029 |

| Externalized Stigma | Total sample HIV-negative/unknown sample Sample living with HIV |

.369* .258* .440* |

.041* .027 .049* |

.328* .231* .391* |

|

| Social Support | Total sample HIV-negative/unknown sample Sample living with HIV |

−.177* −.156* −.164* |

|||

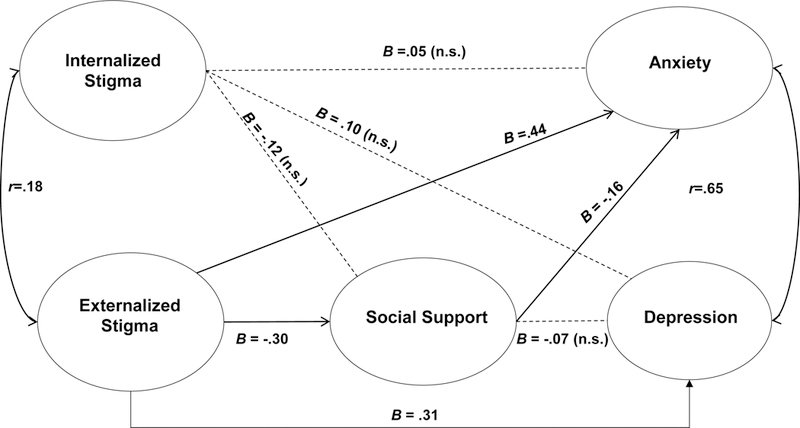

YBMSM living with HIV

As shown in Figure 2, greater externalized stigma was associated with lower social support (β=−.30, p<.05), depression symptoms (β=.31, p<.05) and anxiety symptoms (β=−.44, p<.05) among participants living with HIV. Internalized stigma was not associated with social support (β=−.12, n.s.), or anxiety (β=−.05, n.s.) and depression (β=−.10, n.s.) symptoms. We observed positive correlations between our exogenous stigma factors (i.e., internalized and externalized stigma; r=.18, p<.05) and our endogenous distress factors (i.e., anxiety and depression symptoms; r=.65, p<.05).

Figure 2.

Structural Equation Model for YBMSM living with HIV (N=199)

We observed a negative, direct association between social support and anxiety symptoms (β=−.16, p<.05). We found no indirect association between internalized or externalized stigma and depression symptoms through social support (See Table 3). Externalized stigma was indirectly associated with anxiety through social support (β=−.049, p<.05), yet internalized stigma was not. We found no association between social support and depression symptoms (β=−.07, n.s.) among YBMSM living with HIV.

Discussion

Researchers have advocated for the use of intersectional approaches to understand and address stigma in the lives of YBMSM given their dual (racial and sexual) minority status, as well as being the group most heavily affected by HIV in the United States (Bowleg et al., 2017). In this study, we examined the association between stigma (both internalized and externalized) and psychological distress in a sample of YBMSM. Further, we examined whether social support, a common intervention component in HIV prevention and care interventions, buffered the association between stigma and psychological distress. Overall, our results suggest that experiences of internalized and externalized stigma are linked to increased psychological distress, and also impede the buffering effect conveyed by social support. Furthermore, consistent with minority stress theories (Meyer, 1995, 2001), our findings acknowledge that, although internalized and externalized stigma are correlated, they have independent associations to psychological distress.

Experiences of externalized stigma contributed to psychological distress, with greater instances of racial and sexuality-related discrimination being positively linked to greater symptoms of psychological distress across both HIV-status models. These findings are consistent with prior studies indicating that intersectional stigma exposes individuals to daily stressors that heighten their vulnerability to physical and psychological events of discrimination (Khan, Ilcisin, & Saxton, 2017), and underscore the importance of anti-discrimination policies and stigma-reduction approaches within the context of HIV prevention and care interventions (Hosek et al., 2018). At present, however, it remains unclear whether there are particular settings or contexts that accentuate YBMSM’s vulnerability to these discriminatory events. Given the importance of social location when examining how intersecting identities result in structural inequalities (Bowleg et al., 2017), future research should examine how geospatial characteristics and factors in the social environment accentuate YBMSM’s vulnerability to discrimination in order to inform multilevel interventions.

The relationship between internalized stigma and psychological distress varied by HIV status. Although no association was observed between internalized stigma and psychological distress among the sample living with HIV, seronegative/serounknown YBMSM reporting greater internalized stigma were more likely to exhibit anxiety symptoms. Curiously, there was no relationship between internalized stigma and depressive symptoms in the HIV seronegative/serounknown group. These divergent findings by HIV status are consistent with prior research in this area, and, underscore the need for additional studies to unpack these disparities (Maulsby et al., 2014). Prior research, for instance, has linked anxiety symptoms with hypervigilance; thus, our findings may reflect differences in the salience that seronegative/serounknown YBMSM place to their sexuality relative to their peers living with HIV (Lekas, Siegel, & Leider, 2011). Furthermore, it is possible that YBMSM living with HIV experience different or additional stressors (e.g., HIV-related stigma) not captured in the current analyses. This might explain why YBMSM living with HIV exhibited greater mean anxiety and depression symptoms scores than their HIV seronegative/serounknown peers, even though bivariate analyses did not suggest that these groups differed in their internalized stigma (e.g., internalized homonegativity) scores. Future qualitative and quantitative research examining these proposed pathways is warranted.

The relationship between stigma and social support differed by HIV status. Greater internalized and externalized stigma were associated with lower social support among HIV seronegative/serounknown participants. Among the sample living with HIV, however, we found no direct association between internalized or externalized stigma and social support. Consistent with prior research, social support was both directly and indirectly associated with psychological distress (Huebner et al., 2014; Mutumba et al., 2017; Pingel et al., 2012). Among HIV serounknown/seronegative YBMSM, social support was directly associated with depression and anxiety symptoms. In the decomposition of effects, we also found evidence to suggest that internalized stigma impeded the enactment of social support on anxiety. Among YBMSM living with HIV, social support was directly associated with anxiety symptoms; with indirect effects suggesting that externalized stigma hindered the protective effect of social support on anxiety. Although these findings lend support to the stress-buffering hypothesis (Cohen, Sherrod, & Clark, 1986; Rhodes & Lakey, 1999), our results also suggest that the mechanisms through which social support serves as a protective factor in YBMSM’s lives may differ by HIV status. Consistent to prior literature suggesting that YBMSM living with HIV experience greater social isolation, the divergent findings of social support by HIV status may be attributable to different perceptions regarding social support availability in their social networks. In fact, our bivariate analyses support this notion, with YBMSM living with HIV reporting lower perceived social support relative to their HIV seronegative/serounknown peers. As a result, the opportunity to use social support to buffer the impact of stigma on psychological distress might be attenuated for YBMSM living with HIV. In other words, it seems that the stress-buffering mechanism may be diminished for YBMSM living with HIV. Future research examining how to bolster the availability of social support among YBMSM living with HIV is warranted, as it may inform interventions that maximize the protective effect of social support through the stress-buffering mechanism.

Our study has several limitations deserving mention. First, the study’s cross-sectional data limited the firm temporal ordering of our variables. It is possible that participants experiencing greater psychological distress become more socially isolated and become more vigilant to perceived experiences of stigma. Second, given the absence of a population frame from which to recruit a random sample of YBMSM in the United States, our findings may not be generalizable. Third, given the relatively small number of HIV serounknown participants, we were unable to use SEM to analyze the relationship between stigma, social support, and psychological distress separately for this group. As a result, we grouped HIV serounknown and seronegative participants. Furthermore, given the number of sexual identities observed in our sample, we were unable to test whether our findings differed based on the different sexual orientation identities reported. Future research should explore whether the observed relationships differ across these aforementioned groups. Finally, we measured the overall perceived frequency of stigma and social support in our sample. Future research examining the sources of stigma (e.g., family, neighborhood, providers, partners) and specific types of social support (e.g., instrumental, emotional) may be warranted, as it may inform network-level interventions in this area.

These limitations notwithstanding, our study builds on the existing stigma literature and relies on a large sample of YBMSM. Multilevel HIV prevention and care interventions focused on reducing experiences of stigma in YBMSM’s lives are needed, and, should move beyond the provision of social support as a coping mechanism. Although the provision of social support is important, there has been recognition that individual level factors alone cannot address stigma in YBMSM’s lives. Offering YBMSM more social support, for instance, would serve to compensate for the impact of stigma rather than address its root causes. As such, future intervention efforts are needed that include amelioration of the impact of stigma while also acknowledging underlying causes of stigma. Simultaneously, efforts to promote policies to address structural inequities regarding race, sexuality, and serostatus are required if we are to reduce the disproportionate rate of HIV-related outcomes in YBMSM’s communities (Batchelder, et al 2017; Castel et al, 2015).

Acknowledgements:

We greatly appreciate the hard work of the study staff, and are indebted to the study participants for volunteering their time. This research was sponsored by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), under R21 MH105292 (Muessig & Bauermeister, Co-PIs) and R01 MH093275 (Hightow-Weidman). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH.

References

- Amirkhanian YA (2014). Social networks, sexual networks and HIV risk in men who have sex with men. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 11(1), 81–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaji AB, Bowles KE, Hess KL, Smith JC, Paz-Bailey G, & NHBS study group.(2017).Association between Enacted Stigma and HIV-Related Risk Behavior Among MSM, National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System, 2011. AIDS and Behavior, 21(1), 227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batchelder AW, Safren S, Mitchell AD, Ivardic I, & O’Cleirigh C (2017). Mental health in 2020 for men who have sex with men in the United States. Sexual Health. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg RC, Munthe-Kaas HM, & Ross MW (2016). Internalized homonegativity: A systematic mapping review of empirical research. Journal of homosexuality, 63(4), 541–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg RC, Weatherburn P, Ross MW, & Schmidt AJ (2015). The relationship of internalized homonegativity to sexual health and well-being among men in 38 European countries who have sex with men. Journal of gay & lesbian mental health, 19(3), 285–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L, del Río-González AM, Holt SL, Pérez C, Massie JS, Mandell JE, & A. Boone C (2017). Intersectional Epistemologies of Ignorance: How Behavioral and Social Science Research Shapes What We Know, Think We Know, and Don’t Know About US Black Men’s Sexualities. The Journal of Sex Research, 54 (4), 577–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castel AD, Magnus M, & Greenberg AE (2015). Update on the Epidemiology and Prevention of HIV/AIDS in the USA. Current epidemiology reports, 2(2), 110–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016) Trends in U.S. HIV Diagnoses, 2005–2014. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/hiv-data-trends-fact-sheet-508.pdf Accessed March 20, 2017.

- Clerkin EM, Newcomb ME, & Mustanski B (2011). Unpacking the racial disparity in HIV rates: the effect of race on risky sexual behavior among Black young men who have sex with men (YMSM). Journal of behavioral medicine, 34(4), 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Sherrod DR, & Clark MS (1986). Social skills and the stress-protective role of social support. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(5), 963–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, & Wills TA (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological bulletin, 98(2), 310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S (1988). Psychosocial models of the role of social support in the etiology of physical disease. Health psychology, 7(3), 269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S (2004). Social Relationships and Health. American Psychologist, 59(8), 676–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA, & Chaudoir SR (2009). From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: a review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS & Behavior, 13(6), 1160–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, Amico KR, & Copenhaver MM (2013). HIV stigma mechanisms and well-being among PLWH: a test of the HIV stigma framework. AIDS & Behavior, 17(5), 1785–1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Cunningham CO, & Copenhaver MM (2015). Intersectionality of internalized HIV stigma and internalized substance use stigma: Implications for depressive symptoms. Journal of Health Psychology, 20(8), 1083–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton LA, Driffin DD, Kegler C, Smith H, Conway-Washington C, White D, & Cherry C (2015). The role of stigma and medical mistrust in the routine health care engagement of black men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health, 105(2), e75–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields EL, Bogart LM, Galvan FH, Wagner GJ, Klein DJ, & Schuster MA (2013). Association of discrimination-related trauma with sexual risk among HIV-positive African American men who have sex with men. American journal of public health, 103(5), 875–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores D, Leblanc N, & Barroso J (2016). Enrolling and retaining human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients in their care: A metasynthesis of qualitative studies. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 62, 126–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia J, Parker C, Parker RG, Wilson PA, Philbin M, & Hirsch JS (2016). Psychosocial Implications of Homophobia and HIV Stigma in Social Support Networks: Insights for High-Impact HIV Prevention Among Black Men Who Have Sex With Men. Health Education & Behavior, 43(2), 217–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman CI, Forsyth A, Purcell DW, Allison S, Toledo C, & Gordon CM (2011). Advancing Novel HIV Prevention Intervention Research with MSM-Meeting Report. Public Health Reports, 126, 472–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman CI, Purcell DW, Rotheram-Borus MJ, & Veniegas R (2013). Opportunities for HIV Combination Prevention to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. American Psychologist, 68, 237–246. doi: 10.1037/a0032711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, O’Cleirigh C, Mayer KH, Mimiaga MJ, & Safren SA (2011). Prospective associations between HIV-related stigma, transmission risk behaviors, and adverse mental health outcomes in men who have sex with men. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 42(2), 227–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, & Link BG (2013). Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 813–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM (2000). The psychology of sexual prejudice. Current directions in psychological science, 9(1), 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hermanstyne KA, Green HD Jr., Cook R, Tieu HV, Dyer TV, Hucks-Ortiz C, … Shoptaw S (2018). Social Network Support and Decreased Risk of Seroconversion in Black MSM: Results of the Brothers (HPTN 061) Study. JAIDS, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtgrave DR, Kim JJ, Adkins C, Maulsby C, Lindsey KD, Johnson KM, … Kelley, R. T. (2014). Unmet HIV service needs among Black men who have sex with men in the United States. AIDS & Behavior, 18(1), 36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosek SG, Harper GW, Lemos D, Burke-Miller J, Lee S, Friedman L, & Martinez J (2018). Project ACCEPT: Evaluation of a Group-Based Intervention to Improve Engagement in Care for Youth Newly Diagnosed with HIV. AIDS & Behavior, in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner DM, Kegeles SM, Rebchook GM, Peterson JL, Neilands TB, Johnson WD, & Eke AN (2014). Social oppression, psychological vulnerability, and unprotected intercourse among young Black men who have sex with men. Health Psychology, 33, 1568–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner DM, Kegeles SM, Rebchook GM, Peterson JL, Neilands TB, Johnson WD, & Eke AN (2014). Social oppression, psychological vulnerability, and unprotected intercourse among young Black men who have sex with men. Health Psychology, 33(12), 1568–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman S, Katner H, Banas E, & Kalichman M (2017). Population Density and AIDS-Related Stigma in Large-Urban, Small-Urban, and Rural Communities of the Southeastern USA. Prevention Science, 18(5), 517–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapadia F, Bub K, Barton S, Stults CB, & Halkitis PN (2015). Longitudinal Trends in Sexual Behaviors Without a Condom Among Sexual Minority Youth: The P18 Cohort Study. AIDS and Behavior, 19(12), 2152–2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M, Ilcisin M, & Saxton K (2017). Multifactorial discrimination as a fundamental cause of mental health inequities. International Journal for Equity in Health, 16(1), 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam PK. Naar-King S, & Wright K(2007). Social support and disclosure as predictors of mental health in HIV positive youth. AIDS Patient Care & STDs, 21(1), 20–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkin CA, Van Tieu H, Fields S, Hanscom BS, Connor M, Hanscom B, … & Magnus M (2016). Social Network Factors as Correlates and Predictors of High Depressive Symptoms among Black Men Who Have Sex with Men in HPTN 061. AIDS and Behavior, 21(4), 1163–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lekas HM, Siegel K, & Leider J (2011). Felt and enacted stigma among HIV/HCV- coinfected adults: the impact of stigma layering. Qualitative Health Research, 21(9), 1205–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DD, Herrick AL, Coulter RW, Friedman MR, Mills TC, Eaton LA, … POWER Study Team. (2016). Running Backwards: Consequences of Current HIV Incidence Rates for the Next Generation of Black MSM in the United States. AIDS & Behavior, 20(1), 7–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maulsby C, Millett G, Lindsey K, Kelley R, Johnson K, Montoya D, & Holtgrave D (2014). HIV among Black men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States: A review of the literature. AIDS & Behavior, 18(1), 10–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer KH, Wheeler DP, Bekker LG, Grinsztejn B, Remien RH, Sandfort TG, & Beyrer C (2013). Overcoming biological, behavioral and structural vulnerabilities: New directions in research to decrease HIV transmission in men who have sex with men. JAIDS, 63, S161–S167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Flores SA, Peterson JL, & Bakeman R (2007). Explaining disparities in HIV infection among black and white men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. AIDS, 21, 2083–2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA, Hart TA, Jeffries WL, Wilson PA, … & Remis RS (2012). Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: a meta-analysis. The Lancet, 380(9839), 341–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Peterson JL, Wolitski RJ, & Stall R (2006). Greater risk for HIV infection of black men who have sex with men: a critical literature review. American journal of public health, 96(6), 1007–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutumba M, Bauermeister JA, Harper GW, Musiime V, Lepkowski J, Resnicow K, & Snow RC (2017). Psychological distress among Ugandan adolescents living with HIV: Examining stressors and the buffering role of general and religious coping strategies. Global Public Health, 12(12), 1479–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers HF, Wyatt GE, Ullman JB, Loeb TB, Chin D, Prause N, … & Liu H (2015). Cumulative burden of lifetime adversities: Trauma and mental health in low-SES African Americans and Latino/as. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 7(3), 243–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanni MG, Caruso R, Mitchell AJ, Meggiolaro E, & Grassi L (2015). Depression in HIV infected patients: a review. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17(1), 530–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pingel ES, Bauermeister JA, Elkington KS, Fergus S, Caldwell CH, & Zimmerman MA (2012). Condom Use Trajectories in Adolescence and the Transition to Adulthood: The Role of Mother and Father Support. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22, 350–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueger SY, Malecki CK, Pyun Y, Aycock C, & Coyle S (2016). A meta-analytic review of the association between perceived social support and depression in childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 142(10), 1017–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn K, Voisin DR, Bouris A, Jaffe K, Kuhns L, Eavou R, & Schneider J (2017). Multiple Dimensions of Stigma and Health Related Factors Among Young Black Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS and Behavior, 21(1), 207–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn K, Dickson-Gomez J, DiFranceisco W, Kelly JA, St. Lawrence JS, Amirkhanian YA, & Broaddus M (2015). Correlates of internalized homonegativity among black men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention, 27(3), 212–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh LD, van den Berg JJ, Chambers CS, & Operario D (2016). Social support, psychological vulnerability, and HIV risk among African American men who have sex with men. Psychology & health, 31(5), 549–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PS, Peterson J, Rosenberg ES, Kelley CF, Cooper H, Vaughan A, … DiClemente R (2014). Understanding Racial HIV/STI Disparities in Black and White Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Multilevel Approach. PLoS One, 9(3), e90514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PS, Rosenberg ES, Sanchez TH, Kelley CF, Luisi N, Cooper HL, … Salazar LF (2015). Explaining racial disparities in HIV incidence in black and white men who have sex with men in Atlanta, GA: a prospective observational cohort study. Annals of epidemiology, 25(6), 445–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, & Lowe B (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turan B, Hatcher AM, Weiser SD, Johnson MO, Rice WS, & Turan JM (2017). Framing Mechanisms Linking HIV-Related Stigma, Adherence to Treatment, and Health Outcomes. American Journal of Public Health, 107(6), 863–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CF, Schrager SM, Holloway IW, Meyer IH, & Kipke MD (2014). Minority stress experiences and psychological well-being: The impact of support from and connection to social networks within the Los Angeles house and ball communities. Prevention Science, 15(1), 44–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Latkin C, Tobin K, Patterson J, & Spikes P (2013). Informal social support and depression among African American men who have sex with men. Journal of community psychology, 41(4), 435–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]