Abstract

The kidney is an organ particularly susceptible to damage caused by infections and autoimmune conditions. Renal inflammation confers protection against microbial infections. However, if unchecked, unresolved inflammation may lead to kidney damage. Although proinflammatory cytokine Interleukin-17 (IL-17) is required for immunity against extracellular pathogens, dysregulated IL-17 response is also linked to autoimmunity. In this review, we will discuss the current knowledge of IL-17 activity in the kidney in context to renal immunity and autoimmunity and raise the intriguing question to what extent neutralization of IL-17 is beneficial or harmful to renal inflammation.

Introduction

The kidneys are frequent targets of infectious agents as well as pathogenic immune response in systemic and organ-specific autoimmunity. According to NIH, approximately 14% of the people (∼20 million) in US suffer from some form of chronic kidney diseases (www.niddk.gov). In addition, pyelonephritis is a frequent complication of urinary tract infection by E. coli, the most frequent infection in humans (1). Yet, our understanding of the fundamental immune processes in the kidney lags behind that of other visceral organs such as the gut or liver. The kidney is an immunologically distinct organ, due to its poor regenerative capacity, toxins (uremia), hypoxia and arterial blood pressure, which have profound impact on the ongoing immune response in the kidney (2, 3). Additionally, lack of reliable animal models of kidney diseases and technical difficulties in procuring adequate human renal biopsy samples make it challenging to interrogate pathways linked to host defense and autoimmune diseases in the kidney. Conversely, kidney failure disturbs immunity, causes intestinal barrier dysfunction and dysbiosis, and drives systemic inflammation or immunodeficiency. Therefore, kidney disease is a major health problem and that understanding the mechanisms leading to renal disease is an important endeavor with a great potential health impact. Renal inflammation and immune system activation play a key role in acute or chronic kidney diseases. The objective of this review is to outline some of the evidence connecting immune and inflammatory mechanisms in renal anti-microbial immunity and autoimmune kidney diseases.

In the past decade, IL-17A (IL-17), a pro-inflammatory cytokine, has received considerable attention for its pathogenic role in autoimmune diseases. Although protective in infectious settings, overproduction of IL-17 promotes inflammation and autoimmunity (4). IL-17 recruits and stimulates different cells to drive chronic inflammation. Regulating IL-17 levels or action by using IL-17 or IL-17 receptor blocking antibodies has shown remarkable efficacy in attenuating experimental autoimmune diseases. In this review, we will overview IL-17 induction and function in relation to host defense and autoimmune diseases in the kidney.

Biology of IL-17

IL-17 (IL-17A, also termed CTLA-8) was originally cloned in 1993 (5). The IL-17 family consists of six cytokines IL-17A (IL-17), IL-17B, IL-17C, IL-17D, IL-17E (IL-25) and IL-17F (6, 7). The IL-17R family includes five receptor subunits, IL-17RA, IL-17RB, IL-17RC, IL-17RD and IL-17RE (7). IL-17 and IL-17F exist either as a homodimer or as a heterodimer, and signals through dimeric IL-17RA and IL-17RC receptor complex (7). Although IL-17R is ubiquitously expressed, non-hematopoietic cells are generally the principal responders to IL-17. Upon ligand binding, adaptor protein Act1 is recruited to the receptor subunits and activates multiple cell signaling pathways via different TNF receptor associated factor (TRAF) proteins. Activation of TRAF6 leads to triggering of multiple transcription factors including NF-κB, C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ and MAPK (7). IL-17R-Act1 complex also links with MEKK3 and MEK5 in a TRAF4-dependent manner, ensuing ERK5 activation (7). While TRAF6 and TRAF4-mediated IL-17 signaling results in transcription of classical IL-17 responsive inflammatory genes, IL-17 signaling via Act1-TRAF2-TRAF5 complex controls mRNA stability of IL-17 target genes.

IL-17 induces inflammatory gene expression either by driving de novo gene transcription or by stabilizing target mRNA transcripts. IL-17 activates NF-κB and induces the expression of NF-κB-dependent cytokines. Subsequent studies identified a characteristic “IL-17 gene signature” including cytokines (IL-6, IL-1, G-CSF, GM-CSF and TNFα), chemokines (CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL5, CCL2, CCL7 and CCL20), anti-microbial peptides (AMPs) (βdefensins, S100 proteins and lipocalin2) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (MMPs 1, 3, 9 and 13) (8, 9). Moreover, tissue-specific gene targets are also identified in different organs. For example, IL-17 upregulates renal-protective genes encoding Kallikrein-kinin system in C. albicans infected kidney, which prevent kidney damage during acute or chronic kidney injury (10, 11). IL-17 also activates mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways including extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), p38 and JUN N-terminal kinase (JNK) (12). Additionally, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) transcription factors act as transcriptional regulators of IL-17 signaling in target cells (13).

IL-17 came into prominence in 2005 with the discovery of a new population of CD4+ T helper (Th) cells characterized by the expression of IL-17 (14–17). This subset became known as “T-helper 17” (Th17) cells. During priming of naïve CD4+ T cells, antigen presenting cells secret IL-1, IL-6 and IL-23. This favors Th17 differentiation via STAT3 and RORγt, and secretion of IL-17, IL-17F, GM-CSF and IL-22. Furthermore, a number of innate immune subsets make IL-17, such as γδ+ T cells, natural killer T cells and TCRβ+ ‘natural’ Th17 cells and Type 3 “innate lymphoid cells” (ILC3) (18).

Renal immunity against pathogens

Kidneys in a healthy state are sterile. However, renal infections are common and occur via hematogenous routes or from ascending spread from the bladder or urethra. The very early response to invading pathogens is provided by the unidirectional flow and acidic pH of urine, epithelial barriers, and local production of anti-microbial factors that trap pathogens or interfere with their ability to attach to tissue (2, 19–22). This is followed by a robust innate immune response in the kidney, which provides the first line of host defense. The innate response is initiated by several classes of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as membrane-bound Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs), together with inflammasomes. Following pathogen clearance, both innate effector cells and kidney-resident cells release tissue repair enzymes and anti-inflammatory proteins, which are necessary to maintain immune homeostasis and repair injured tissue. Innate response also set the stage for adaptive immunity, required for long term protective immunity in the kidney.

A. IL-17-mediated renal immunity against bacterial infections

The most common bacteria responsible for kidney infection is Escherichia coli (E. coli), which accounts for close to 80% of cases of kidney (pyelonephritis), urinary tract (UTI) and bladder infections (cystitis) (23). Other bacterias include methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aurues (MRSA), Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterococcus faecalis (23).

i. Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC)

Urinary tract infection (UTI) caused by UPEC is one of the most common infection in humans, affecting 150 million people each year worldwide (23). Bacteria present in fecal matter infect the peri-urethral area and bladder. If left unchecked, the bacteria ascend the ureters to the kidney and establish acute pyelonephritis. In most severe cases UPEC infection may lead to permanent renal scarring and septicemia (1).

Sivick et al. systematically interrogated the impact of IL-17 in innate and adaptive immunity against UPEC in a mouse model of trans-urethral infection (24). In this system, IL-17 has been shown to play no role in adaptive immune response in the bladder. In contrast, IL-17 produced by γδ+ T cells drives bacterial clearance in the infected bladder at early time point. The protective effect of IL-17 was attributed to its ability to induce cytokines and chemokines necessary to facilitate the influx of neutrophils and other innate effectors in the bladder. In line with this observation, mice deficient in γδ+ T cells showed increased susceptibility to UTI (25). However, this study did not measure renal IL-17 levels nor do they investigate the contribution of IL-17 in defense against UPEC in the kidneys. A separate report showed that expression of IL-17 is increased in the kidney following UPEC infection at 24 and 48 h p.i. This increase in IL-17 level is regulated by surfactant proteins A and D in the infected kidney (26). Consequently, surfactant proteins A and D knockout mice showed increased bacterial load in the kidney following UPEC infection. Future in-depth studies should focus on addressing the renal activities of IL-17 in the kidneys following UTI infection.

ii. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aurues (MRSA)

MRSA infection is a major clinical challenge and in most cases difficult to treat. Although MRSA resides in the skin and nasal tract, infection of kidney may occur through blood stream infection and from ascending spread from urinary tract (27). If uncontrolled, MRSA infection in the kidney may lead to the development of more serious conditions including septic shock. The first evidence documenting 15-fold increase in the kidney burden of MRSA following IL-17 neutralization suggest that IL-17 plays a vital role in protecting against disseminated infection. Interestingly, neutralization of IL-22, another cytokine produced by Th17 cells, has no impact on renal bacterial load. Kidneys of mice subjected to IL-17 neutralization showed reduced number of T cells and neutrophils. However, renal expression of AMPs and cytokines were unchanged (28). Indeed, protective efficacy of NDV3 vaccine against invasive MRSA infection requires the induction of IL-17 response (29). O-Acetylation of peptidoglycan of MRSA limits Th17 cell priming and permits MRSA reinfection in the absence of functional Th17 memory (30). Moreover, vaccination with recombinant N terminus of the candidal Als3p adhesin (rAls3p-N) resulted in ∼5-fold reduction in kidney bacterial burden and improved survival in mice. The vaccination primed Th1, Th17 and Th1/Th17 cells in the draining lymph nodes, which in turn stimulated neutrophil influx and proinflammatory cytokine levels in the kidney (31). A new report showed that vaccination with non-toxic mutant TSST-1 drives IL-17-dependent protection against S. aureus infection (32). In vaccinated animals, IL-17 producing cells were increased in the spleen and the vaccine-induced protection against S. aureus was abolished in the IL-17 knockout mice (32).

B. IL-17-mediated renal immunity against fungal infections

Invasive fungal infections are a major cause of mortality in hospitalized patients (33). The opportunistic pathogens such as Candida, Aspergillus, Mucor, Cryptococcus, and Histoplasma are particularly known to infect the kidneys in predisposed individuals with serious complications. At the same time there is a high incidence of invasive fungal infections in patients with renal disease and kidney transplant recipients under effects of immunosuppression and environmental exposure (34). There are two mechanisms by which these fungal species infect the kidney: infections can begin in the lower urinary tract and ascend to the kidneys, and infection can also occur via hematogenous dissemination to the kidneys.

Candida albicans is the causative agent of candidiasis at the mucosal sites including oral cavity, skin and vagina (35). However, the most severe Candida-induced disease resulting in high mortality rate (∼40%) is disseminated candidiasis (33, 36, 37). The kidney is the most common organ involved in disseminated candidiasis. This was demonstrated in a review of 45 autopsies of patients with disseminated candidiasis. Almost 89% (40 out 45) had overt histological evidence of renal involvement (38). Similarly, majority of the fungus are recovered from the kidneys of systemically infected mice. During disseminated candidiasis, C. albicans hyphae invade and damage kidney leading to renal insufficiency (10). Considerable data implicate IL-17 in immunity to disseminated candidiasis (39–42). Data from our group and others have shown that IL-17 is produced locally in the kidney within 24 to 48 h in response to fungal infection (10, 43). Accordingly, mice lacking IL-17RA or IL-17 exhibited increased fungal load in the kidney and succumb to infection earlier than control animals (39–42).

Although IL-17 has been detected in the fungal infected kidney, the exact cellular source of IL-17 was unknown. By taking advantage of sensitive IL-17 fate tracking mice, we demonstrated that innate γδ+ T cells are the primary cellular source of IL-17 in the C. albicans infected kidneys, with minor contribution from innate αβ+ T cells (44). In uninfected mice, a small baseline population of IL-17 producing γδ+ T cells was also observed, which proliferated in response to systemic fungal infection. These data indicate that both kidney resident and infiltrating γδ+ T cells may contribute to renal IL-17 production in the fungal infected kidney.

IL-17 is classically known as a regulator of neutrophils and AMPs. Neutrophil influx was reduced in the kidneys of IL-17RA−/− mice during disseminated candidiasis (39). Furthermore, mobilization of the neutrophils in the blood during systemic challenge with C. albicans was also impaired. Interestingly, two reports indicated that IL-17-driven signaling in disseminated candidiasis does not occur in the kidney, but instead targets bone marrow to stimulate NK cell production of GM-CSF; a cytokine responsible for driving candidacidal activity of neutrophils in the kidney(41, 45). In sharp contrast, we showed that IL-17 receptor expression on non-hematopoietic cells is required for host defense against disseminated candidiasis and there is no contribution for hematopoetic cells (44). IL-17 acts on renal tubular epithelial cells to induce the expression of nephron-protective Kallikrein-kinin system (KKS) (10). Activation of KKS is critical to prevent kidney damage and restore renal function by inhibiting apoptotic cell death of kidney-resident cells during hyphal invasion. Accordingly, treatment of mice with specific KKS agonist, currently in clinical trial for numerous inflammatory diseases (www.clinicaltrial.gov) prevents renal damage and improved survival following disseminated candidiasis (10, 44). Interestingly, vaccination with candidal Als3p adhesin (rAls3p-N) with aluminum hydroxide adjuvant lowers renal fungal burden by a log in a Th17 and neutrophil-dependent manner (31). In contrast, mice deficient in IL-17C show improved survival due to reduced renal inflammation and damage in the fungal infected kidney (46). Supporting this line, others have proposed that the Th17-induced activation of neutrophils may also result in an overwhelming inflammatory tissue response that impairs antifungal immune resistance and leads to defective pathogen clearance (47). Although renal infections by non-albicans species are increasing at an alarming rate, very little is known about the role of IL-17-dependent renal immunity against these fungal species. A recent analysis of C. tropicalis systemic infection in mice revealed that IL-17R/Act1 signaling is dispensable for antifungal immunity, whereas CARD9 and TNFα signaling in neutrophils are essential (48).

IL-17 in autoimmune kidney diseases

IL-17 is a pleiotropic cytokine that plays important role in tissue inflammation. This is primarily mediated by inducing the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and MMPs. As kidney is often affected by dysregulated systemic or organ-specific immunity, here we will only highlight the pathogenic role for IL-17 in autoimmune kidney diseases.

i. Mouse models of experimental autoimmune glomerulonephritis

Since the discovery of Th17 cells in 2005, IL-17 has been implicated in many autoinflammatory diseases. Interestingly, the link between IL-17 and renal inflammation was first demonstrated long before the discovery of Th17 cells. Van Kooten et al. showed that IL-17 drives the expression of cytokines and chemokines from tubular epithelial cells under in vitro condition (49). We demonstrated that IL-17-mediated expression of inflammatory mediators’ from tubular epithelial cells is critical for migration of neutrophils. Similarly, mice deficient in IL-17 receptor signaling showed diminished neutrophil influx, but not monocytes and macrophages, in a mouse model of anti-GBM glomerulonephritis (50). Data from our lab and others have shown that both kidney infiltrating CD4+ and γδ+ T cells produce IL-17 in response to kidney injury (43, 50). Indeed a series of studies involving mouse models of various forms of autoimmune glomerulonephritis have provided evidence for functional importance of IL-17 in disease pathogenesis. For example, studies in mouse models of crescentic glomerulonephritis and nephrotoxic nephritis showed that IL-23/Th17-axis and IL-17 are absolutely required for renal dysfunction and pathology (51, 52). Interestingly, ameliorated renal pathology observed in the IL-23p19−/− and IL-17−/− mice are independent of Th1 response, thus arguing against the longstanding notion that glomerulonephritis is a Th1-mediated disease. IL-17 along with TNFα (a cytokine with which IL-17 exhibits profound synergy) drives the expression of chemokine signals such CCL20 from RTECs, required for the infiltration of CCR6+ Th17 and T regulatory cells in the kidney (43). Subsequently, by taking advantage of p40−/− (mice deficient in both IL-12 and IL-23), p35−/− (mice deficient in IL-12 only) and p19−/− (mice deficient in IL-23 only), the relative contribution of IL-12 and IL-23 was interrogated in a mouse model Goodpasture disease. Knockout of IL-23, but not IL-12, led to the diminished proliferation and activation of alpha3 type IV collagen-specific T and B cells and reduced cytokine and antibody production by immune cells (52). As a result, disease severity was significantly diminished in mice deficient in IL-23 signaling. Using a mouse model of T cell planted antigen on the GBM, it was shown that both Th1 and Th17 cells can mediate renal injury (53). However, the immunopathological features, time kinetic and prevalence of certain inflammatory mediators were different in recipient mice receiving either Th1 or Th17 cells. Th17 cells induced the expression of chemokines necessary for neutrophil infiltration and causing early kidney pathology. These results support a report showing that IL-17 promotes early but attenuates established disease in crescentic glomerulonephritis in mice (54). On the other hand, Th1 cell-recipients showed more of a macrophage dominated renal injury at later time points. Following glomerulonephritis, renal infiltration of Th17 cells peaks at day 10 post glomerular injury followed by a decline in the number in course of disease. In contrast, Th1 cells and T regulatory cells infiltrate the kidney at later stages. The mechanisms for differential infiltration of various subsets of CD4+ T cells are poorly understood. However, careful analyses of multiple IL-17 reporter mice revealed that Th17 cells are very stable and do not show signs of transdifferentiation to IFNγ+ or Treg cells in the nephritic kidneys (55). Recently, the migration of Th17 cell from the intestine to nephritic kidney has been elegantly demonstrated in a photo-convertible Kaede mice (56), indicating that intestinal microbiome may impact Th17-dominated kidney diseases. Mice deficient in T-bet and consequently in Th1 cells showed diminished nephritis despite enhanced Th17 response, suggesting that Th1 cells are required for Th17 cells-driven nephritis (57). Finally, a crucial role for IL-17 as a mediator of renal tissue damage was also demonstrated in a murine model of anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis. Here, IL-17 knockout mice were protected from kidney injury due to impairment of both, the innate and the adaptive arms of the immune response (58). Similar to IL-17, other IL-17 family members have been implicated in autoimmune kidney diseases. Mice deficient in IL-17F and IL-17C signaling showed ameliorated renal pathology in mouse model of experimental crescentic and ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis, respectively (59, 60). In two independent studies, polymorphism in the IL-17 pathway genes has been linked to the risk of CKD. An association was identified between allele rs4819554 A, part of the IL-17RA promoter, and risk of developing end stage renal disease and increased expression of IL-17RA and Th17 cell frequency (61, 62).

IL-17RA is utilized by all the IL-17 family members for signaling (4). Although IL-17RA is ubiquitously expressed, majority of the studies showed that IL-17R signaling is mostly restricted to cells of non-hematopoietic origin. Accordingly, we found that IL-17RA−/− mice was protected from autoimmune glomerulonephritis, as evident by reduced glomerular crescent formation, tubulointerstitial inflammation and neutrophil influx in the kidney (50). Interestingly, systemic and humoral immunity was not affected in the absence of IL-17R signaling, suggesting that IL-17RA might be a promising therapeutic target with minimal adverse effects (50). In contrast, another study showed that IL-17RA-deficiency protected mice from crescent formation but not from glomerular necrosis or renal interstitial injury. Investigation of bone marrow chimeras to identify the IL-17 target cells types in glomerulonephritis revealed similar contributions of IL-17 signaling in hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells in the pathogenesis of glomerular pathology (63). However, the role of humoral immunity remains controversial and the exact mechanisms still need to be elucidated.

ii. Lupus nephritis

Lupus nephritis is a severe clinical manifestation of systemic lupus erythematous (SLE) and affects up to 60% of patients (64). While experimental evidence suggests a pathogenic role for IL-17 in mouse models of experimental glomerulonephritis, the contribution of IL-17 in lupus nephritis is an active area of debate. IL-17 producing double-negative T cells (CD3+CD4-CD8-) were detected in the nephritic kidneys of MRL/lpr mouse and lupus patients (65, 66). Using MHC class II tetramers, Kattah et al. identified IL-17 producing CD4+ T cells specific for spliceosomal protein U1–70 in MRL/lpr mice (67). Subsequent studies demonstrated that omission of the IL-23 receptor protected B6/lpr mice from lupus nephritis and that transfer of IL-23-treated lymph node cells from B6/lpr mice induced lupus nephritis in Rag1−/− mice (68). Studies by our group and others have also implicated Th17 cells and IL-17 in the development of proliferative glomerulonephritis in MRL/lpr mice (69, 70). IL-17 cytokines and their signaling via the adaptor protein Act1 contributes to lethal pathology in an FcγR2b-deficient mouse model of lupus nephritis (71). Moreover, studies in autoimmune prone BXD2 mice showed that IL-17 and Th17 cells orchestrate autoreactive germinal center formation and consequently lupus like disease development (72). In the pristine-induced model of lupus nephritis, lack of IL-17A or IL-17F ameliorated disease severity (70, 73). We showed that cross-talk between complement component C5a and Th17 cells are required to inhibit Th17-suppressive type I Interferon signals and pathogenesis of pristine-induced lupus nephritis (74–76). However, nagging discrepancies exist against these interpretations. In a recent study, IL-17 deficiency or neutralization of IL-17 demonstrated minimal impact on the development of proliferative glomerulonephritis in MRL/lpr mice or NZB/NZW mice, respectively (77). The frequency of kidney infiltrating IL-17 producing double-negative T cells and CD4+ T cells were scant compared to number of IFNγ+ cells, indicating a predominance of the Th1 immune response in these models of lupus nephritis. The reasons for the apparent disagreement between these findings are currently unclear. However, difference in genetic backgrounds and microbiome population may account for the discordance observed between these findings and require careful evaluation in the near future.

Multiple studies showed that patients with lupus exhibit elevated serum levels of IL-17, increased numbers of circulating IL-17-producing T cells, and increased IL-17 production by lymphocytes compared to age and sex-matched healthy volunteers (65, 78). In some but not all cases, IL-17 serum levels correlated with lupus disease activity (78, 79). The number of Th17 cells in the peripheral blood of lupus patients increased during flares and decreased following successful treatment (79). Another study demonstrated that IL-17 plasma levels correlated positively with proteinuria and levels of double-stranded DNA antibodies in patients with lupus nephritis, suggesting that IL-17 could serve as a biomarker of disease activity (80). Interestingly, we observed a negative correlation between the frequency of Th17 cells and type I Interferon level in a subset of lupus patients (76). IL-17 expressing double negative T cells were found in kidney biopsy samples of patients with lupus nephritis (65). In sharp contrast, a separate study found no significant association between serum IL-17 levels and nephritis in patients with lupus (81). Thus, the functional role of IL-17 or IL-17 producing innate and adaptive immune cells in renal involvement in lupus patients remains to be fully elucidated.

iii. IgA nephropathy

Patients with IgA nephropathy showed increased serum level of IL-17 in comparison to healthy individuals (82). In vitro stimulation of human mesengial cells with IgA1 has been shown to induce IL-17 production (83). IL-17 might participate in the development of nephropathy by inducing the production and glycosylation of IgA1 in B cells (84). IL-17 can also stimulate the release of cytokines from peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with IgA nephropathy (85). Moreover, imbalance of Treg to Th17 ratio in IgA nephropathy patients has been suggested to play a role in disease pathogenesis and progression (86). With regard to the Th17 response in other human renal inflammatory diseases, such as ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis, Goodpasture’s syndrome, or acute interstitial nephritis, there are no data available, emphasizing the pressing need for future research efforts in this field.

Conclusions

IL-17 and IL-17 producing cells are vital to a wide range of immunologic functions in the kidney. The generation of IL-17 occurs promptly after the initial insults, which may be either infections or chronic kidney injury. The early IL-17 response shapes the inflammatory milieu and orchestrates many downstream processes in innate as well as adaptive immune responses in the kidney. The net consequence can be promotion or inhibition of local renal immune reactions. What factor dictates which one or the other overcomes remain to be precisely defined in the kidney. IL-17 causes autoimmune diseases, but is also implicated in mediating protection against antimicrobial infections. Thus it is imperative to understand how IL-17, which protects kidney from infections, is rendered harmful in the presence of autoinflammatory conditions. Antibodies to IL-17 and IL-17RA are currently approved for the treatment of psoriasis (87, 88). Several other clinical trials (∼90 trials) are currently ongoing targeting various IL-17 pathway molecules in autoimmune diseases (www.clinicaltrials.gov). Therefore, answering these questions is crucial to developing anti-IL-17 based therapies for autoimmune kidney diseases. Since IL-17 is a key determinant of local renal immunity processes, such interventions should be cautiously designed.

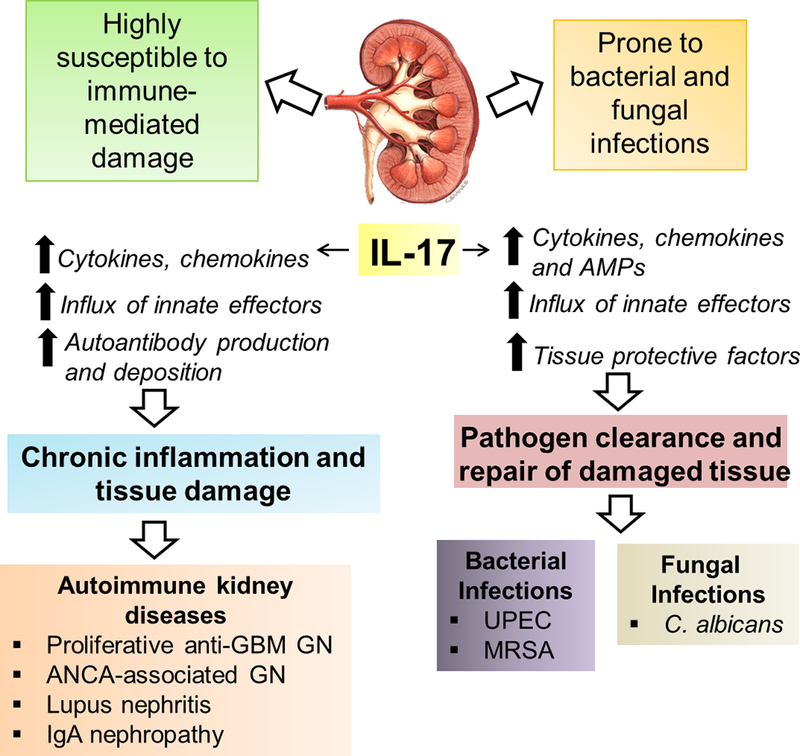

Fig 1: Renal activities of IL-17 in kidney diseases:

Kidney is subject to many infections as well as autoimmune injury. IL-17 is detected in the kidney following renal infections and autoimmune conditions. Owing to its proinflammatory properties, IL-17 is critical to host anti-microbial defense. However, if unrestrained, IL-17 signaling is linked to many autoimmune kidney diseases.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Biswas lab members for helpful suggestions and discussions.

Funding information: This work was supported by the Division of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology, UPMC and NIH grant (# DK104680) to P.S.B.

Bibliography

- 1.Flores-Mireles AL, Walker JN, Caparon M, and Hultgren SJ 2015. Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nature reviews. Microbiology 13: 269–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurts C, Panzer U, Anders HJ, and Rees AJ 2013. The immune system and kidney disease: basic concepts and clinical implications. Nature reviews. Immunology 13: 738–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kato S, Chmielewski M, Honda H, Pecoits-Filho R, Matsuo S, Yuzawa Y, Tranaeus A, Stenvinkel P, and Lindholm B 2008. Aspects of immune dysfunction in end-stage renal disease. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN 3: 1526–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaffen SL 2011. Recent advances in the IL-17 cytokine family. Current opinion in immunology 23: 613–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rouvier E, Luciani MF, Mattei MG, Denizot F, and Golstein P 1993. CTLA-8, cloned from an activated T cell, bearing AU-rich messenger RNA instability sequences, and homologous to a herpesvirus saimiri gene. Journal of immunology 150: 5445–5456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaffen SL, Jain R, Garg AV, and Cua DJ 2014. The IL-23-IL-17 immune axis: from mechanisms to therapeutic testing. Nature reviews. Immunology 14: 585–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amatya N, Garg AV, and Gaffen SL 2017. IL-17 Signaling: The Yin and the Yang. Trends in immunology 38: 310–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwakura Y, Ishigame H, Saijo S, and Nakae S 2011. Functional specialization of interleukin-17 family members. Immunity 34: 149–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onishi RM, and Gaffen SL 2010. Interleukin-17 and its target genes: mechanisms of interleukin-17 function in disease. Immunology 129: 311–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramani K, Garg AV, Jawale CV, Conti HR, Whibley N, Jackson EK, Shiva SS, Horne W, Kolls JK, Gaffen SL, and Biswas PS 2016. The Kallikrein-Kinin System: A Novel Mediator of IL-17-Driven Anti-Candida Immunity in the Kidney. PLoS pathogens 12: e1005952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu K, Li QZ, Delgado-Vega AM, Abelson AK, Sanchez E, Kelly JA, Li L, Liu Y, Zhou J, Yan M, Ye Q, Liu S, Xie C, Zhou XJ, Chung SA, Pons-Estel B, Witte T, de Ramon E, Bae SC, Barizzone N, Sebastiani GD, Merrill JT, Gregersen PK, Gilkeson GG, Kimberly RP, Vyse TJ, Kim I, D’Alfonso S, Martin J, Harley JB, Criswell LA, Profile Study G, Italian Collaborative G, German Collaborative G, Spanish Collaborative G, Argentinian Collaborative G, Consortium S, Wakeland EK, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, and Mohan C 2009. Kallikrein genes are associated with lupus and glomerular basement membrane-specific antibody-induced nephritis in mice and humans. The Journal of clinical investigation 119: 911–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen F, and Gaffen SL 2008. Structure-function relationships in the IL-17 receptor: implications for signal transduction and therapy. Cytokine 41: 92–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruddy MJ, Wong GC, Liu XK, Yamamoto H, Kasayama S, Kirkwood KL, and Gaffen SL 2004. Functional cooperation between interleukin-17 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha is mediated by CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein family members. The Journal of biological chemistry 279: 2559–2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cua DJ, Sherlock J, Chen Y, Murphy CA, Joyce B, Seymour B, Lucian L, To W, Kwan S, Churakova T, Zurawski S, Wiekowski M, Lira SA, Gorman D, Kastelein RA, and Sedgwick JD 2003. Interleukin-23 rather than interleukin-12 is the critical cytokine for autoimmune inflammation of the brain. Nature 421: 744–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park H, Li Z, Yang XO, Chang SH, Nurieva R, Wang YH, Wang Y, Hood L, Zhu Z, Tian Q, and Dong C 2005. A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nature immunology 6: 1133–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrington LE, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, Turner H, Murphy TL, Murphy KM, and Weaver CT 2005. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nature immunology 6: 1123–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langrish CL, Chen Y, Blumenschein WM, Mattson J, Basham B, Sedgwick JD, McClanahan T, Kastelein RA, and Cua DJ 2005. IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. The Journal of experimental medicine 201: 233–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cua DJ, and Tato CM 2010. Innate IL-17-producing cells: the sentinels of the immune system. Nature reviews. Immunology 10: 479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hepburn NJ, Ruseva MM, Harris CL, and Morgan BP 2008. Complement, roles in renal disease and modulation for therapy. Clinical nephrology 70: 357–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.John R, and Nelson PJ 2007. Dendritic cells in the kidney. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 18: 2628–2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson PJ, Rees AJ, Griffin MD, Hughes J, Kurts C, and Duffield J 2012. The renal mononuclear phagocytic system. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 23: 194–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith KD 2009. Toll-like receptors in kidney disease. Current opinion in nephrology and hypertension 18: 189–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stamm WE, and Norrby SR 2001. Urinary tract infections: disease panorama and challenges. The Journal of infectious diseases 183 Suppl 1: S1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sivick KE, Schaller MA, Smith SN, and Mobley HL 2010. The innate immune response to uropathogenic Escherichia coli involves IL-17A in a murine model of urinary tract infection. Journal of immunology 184: 2065–2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones-Carson J, Balish E, and Uehling DT 1999. Susceptibility of immunodeficient gene-knockout mice to urinary tract infection. The Journal of urology 161: 338–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu F, Ding G, Zhang Z, Gatto LA, Hawgood S, Poulain FR, Cooney RN, and Wang G 2016. Innate immunity of surfactant proteins A and D in urinary tract infection with uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Innate immunity 22: 9–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hassoun A, Linden PK, and Friedman B 2017. Incidence, prevalence, and management of MRSA bacteremia across patient populations-a review of recent developments in MRSA management and treatment. Critical care 21: 211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan LC, Chaili S, Filler SG, Barr K, Wang H, Kupferwasser D, Edwards JE Jr., Xiong YQ, Ibrahim AS, Miller LS, Schmidt CS, Hennessey JP Jr., and Yeaman MR 2015. Nonredundant Roles of Interleukin-17A (IL-17A) and IL-22 in Murine Host Defense against Cutaneous and Hematogenous Infection Due to Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Infection and immunity 83: 4427–4437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeaman MR, Filler SG, Chaili S, Barr K, Wang H, Kupferwasser D, Hennessey JP Jr., Fu Y, Schmidt CS, Edwards JE Jr., Xiong YQ, and Ibrahim AS 2014. Mechanisms of NDV-3 vaccine efficacy in MRSA skin versus invasive infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111: E5555–5563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanchez M, Kolar SL, Muller S, Reyes CN, Wolf AJ, Ogawa C, Singhania R, De Carvalho DD, Arditi M, Underhill DM, Martins GA, and Liu GY 2017. O-Acetylation of Peptidoglycan Limits Helper T Cell Priming and Permits Staphylococcus aureus Reinfection. Cell host & microbe 22: 543–551 e544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin L, Ibrahim AS, Xu X, Farber JM, Avanesian V, Baquir B, Fu Y, French SW, Edwards JE Jr., and Spellberg B 2009. Th1-Th17 cells mediate protective adaptive immunity against Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans infection in mice. PLoS pathogens 5: e1000703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Narita K, Hu DL, Asano K, and Nakane A 2015. Vaccination with non-toxic mutant toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 induces IL-17-dependent protection against Staphylococcus aureus infection. Pathogens and disease 73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NA, Levitz SM, Netea MG, and White TC 2012. Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Science translational medicine 4: 165rv113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yapar N 2014. Epidemiology and risk factors for invasive candidiasis. Therapeutics and clinical risk management 10: 95–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dongari-Bagtoglou A, and Fidel P 2005. The host cytokine responses and protective immunity in oropharyngeal candidiasis. J Dent Res 84: 966–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown GD, and Netea MG 2012. Exciting developments in the immunology of fungal infections. Cell Host Microbe 11: 422–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lionakis MS 2014. New insights into innate immune control of systemic candidiasis. Medical mycology 52: 555–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lehner T 1964. Systemic Candidiasis and Renal Involvement. Lancet 2: 1414–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang W, Na L, Fidel PL, and Schwarzenberger P 2004. Requirement of interleukin-17A for systemic anti-Candida albicans host defense in mice. The Journal of infectious diseases 190: 624–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van de Veerdonk FL, Kullberg BJ, Verschueren IC, Hendriks T, van der Meer JW, Joosten LA, and Netea MG 2010. Differential effects of IL-17 pathway in disseminated candidiasis and zymosan-induced multiple organ failure. Shock 34: 407–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bar E, Whitney PG, Moor K, Reis e Sousa C, and LeibundGut-Landmann S 2014. IL-17 regulates systemic fungal immunity by controlling the functional competence of NK cells. Immunity 40: 117–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saijo S, Ikeda S, Yamabe K, Kakuta S, Ishigame H, Akitsu A, Fujikado N, Kusaka T, Kubo S, Chung SH, Komatsu R, Miura N, Adachi Y, Ohno N, Shibuya K, Yamamoto N, Kawakami K, Yamasaki S, Saito T, Akira S, and Iwakura Y 2010. Dectin-2 recognition of alpha-mannans and induction of Th17 cell differentiation is essential for host defense against Candida albicans. Immunity 32: 681–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turner JE, Krebs C, Tittel AP, Paust HJ, Meyer-Schwesinger C, Bennstein SB, Steinmetz OM, Prinz I, Magnus T, Korn T, Stahl RA, Kurts C, and Panzer U 2012. IL-17A production by renal gammadelta T cells promotes kidney injury in crescentic GN. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 23: 1486–1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramani K, Jawale CV, Verma AH, Coleman BM, Kolls JK, and Biswas PS 2018. Unexpected kidney-restricted role for IL-17 receptor signaling in defense against systemic Candida albicans infection. JCI insight 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dominguez-Andres J, Feo-Lucas L, de la Escalera M. Minguito, Gonzalez L, Lopez-Bravo M, and Ardavin C 2017. Inflammatory Ly6C(high) Monocytes Protect against Candidiasis through IL-15-Driven NK Cell/Neutrophil Activation. Immunity 46: 1059–1072 e1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang J, Meng S, Hong S, Lin X, Jin W, and Dong C 2016. IL-17C is required for lethal inflammation during systemic fungal infection. Cellular & molecular immunology 13: 474–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zelante T, De Luca A, Bonifazi P, Montagnoli C, Bozza S, Moretti S, Belladonna ML, Vacca C, Conte C, Mosci P, Bistoni F, Puccetti P, Kastelein RA, Kopf M, and Romani L 2007. IL-23 and the Th17 pathway promote inflammation and impair antifungal immune resistance. European journal of immunology 37: 2695–2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Whibley N, Jaycox JR, Reid D, Garg AV, Taylor JA, Clancy CJ, Nguyen MH, Biswas PS, McGeachy MJ, Brown GD, and Gaffen SL 2015. Delinking CARD9 and IL-17: CARD9 Protects against Candida tropicalis Infection through a TNF-alpha-Dependent, IL-17-Independent Mechanism. Journal of immunology 195: 3781–3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Kooten C, Boonstra JG, Paape ME, Fossiez F, Banchereau J, Lebecque S, Bruijn JA, De Fijter JW, Van Es LA, and Daha MR 1998. Interleukin-17 activates human renal epithelial cells in vitro and is expressed during renal allograft rejection. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 9: 1526–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ramani K, Pawaria S, Maers K, Huppler AR, Gaffen SL, and Biswas PS 2014. An essential role of interleukin-17 receptor signaling in the development of autoimmune glomerulonephritis. Journal of leukocyte biology 96: 463–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paust HJ, Turner JE, Steinmetz OM, Peters A, Heymann F, Holscher C, Wolf G, Kurts C, Mittrucker HW, Stahl RA, and Panzer U 2009. The IL-23/Th17 axis contributes to renal injury in experimental glomerulonephritis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 20: 969–979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ooi JD, Phoon RK, Holdsworth SR, and Kitching AR 2009. IL-23, not IL-12, directs autoimmunity to the Goodpasture antigen. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 20: 980–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Summers SA, Steinmetz OM, Li M, Kausman JY, Semple T, Edgtton KL, Borza DB, Braley H, Holdsworth SR, and Kitching AR 2009. Th1 and Th17 cells induce proliferative glomerulonephritis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 20: 2518–2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Odobasic D, Gan PY, Summers SA, Semple TJ, Muljadi RC, Iwakura Y, Kitching AR, and Holdsworth SR 2011. Interleukin-17A promotes early but attenuates established disease in crescentic glomerulonephritis in mice. The American journal of pathology 179: 1188–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krebs CF, Turner JE, Paust HJ, Kapffer S, Koyro T, Krohn S, Ufer F, Friese MA, Flavell RA, Stockinger B, Steinmetz OM, Stahl RA, Huber S, and Panzer U 2016. Plasticity of Th17 Cells in Autoimmune Kidney Diseases. Journal of immunology 197: 449–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krebs CF, Paust HJ, Krohn S, Koyro T, Brix SR, Riedel JH, Bartsch P, Wiech T, Meyer-Schwesinger C, Huang J, Fischer N, Busch P, Mittrucker HW, Steinhoff U, Stockinger B, Perez LG, Wenzel UO, Janneck M, Steinmetz OM, Gagliani N, Stahl RAK, Huber S, Turner JE, and Panzer U 2016. Autoimmune Renal Disease Is Exacerbated by S1P-Receptor-1-Dependent Intestinal Th17 Cell Migration to the Kidney. Immunity 45: 1078–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Phoon RK, Kitching AR, Odobasic D, Jones LK, Semple TJ, and Holdsworth SR 2008. T-bet deficiency attenuates renal injury in experimental crescentic glomerulonephritis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 19: 477–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gan PY, Steinmetz OM, Tan DS, O’Sullivan KM, Ooi JD, Iwakura Y, Kitching AR, and Holdsworth SR 2010. Th17 cells promote autoimmune anti-myeloperoxidase glomerulonephritis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 21: 925–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Riedel JH, Paust HJ, Krohn S, Turner JE, Kluger MA, Steinmetz OM, Krebs CF, Stahl RA, and Panzer U 2016. IL-17F Promotes Tissue Injury in Autoimmune Kidney Diseases. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 27: 3666–3677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krohn S, Nies JF, Kapffer S, Schmidt T, Riedel JH, Kaffke A, Peters A, Borchers A, Steinmetz OM, Krebs CF, Turner JE, Brix SR, Paust HJ, Stahl RAK, and Panzer U 2018. IL-17C/IL-17 Receptor E Signaling in CD4(+) T Cells Promotes TH17 Cell-Driven Glomerular Inflammation. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 29: 1210–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Coto E, Gomez J, Suarez B, Tranche S, Diaz-Corte C, Ortiz A, Ruiz-Ortega M, Coto-Segura P, Batalla A, and Lopez-Larrea C 2015. Association between the IL17RA rs4819554 polymorphism and reduced renal filtration rate in the Spanish RENASTUR cohort. Human immunology 76: 75–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim YG, Kim EY, Ihm CG, Lee TW, Lee SH, Jeong KH, Moon JY, Chung JH, and Kim YH 2012. Gene polymorphisms of interleukin-17 and interleukin-17 receptor are associated with end-stage kidney disease. American journal of nephrology 36: 472–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ghali JR, O’Sullivan KM, Eggenhuizen PJ, Holdsworth SR, and Kitching AR 2017. Interleukin-17RA Promotes Humoral Responses and Glomerular Injury in Experimental Rapidly Progressive Glomerulonephritis. Nephron 135: 207–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kulkarni OP, and Anders HJ 2012. Lupus nephritis. How latest insights into its pathogenesis promote novel therapies. Current opinion in rheumatology 24: 457–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Crispin JC, Oukka M, Bayliss G, Cohen RA, Van Beek CA, Stillman IE, Kyttaris VC, Juang YT, and Tsokos GC 2008. Expanded double negative T cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus produce IL-17 and infiltrate the kidneys. Journal of immunology 181: 8761–8766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang Z, Kyttaris VC, and Tsokos GC 2009. The role of IL-23/IL-17 axis in lupus nephritis. Journal of immunology 183: 3160–3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kattah NH, Newell EW, Jarrell JA, Chu AD, Xie J, Kattah MG, Goldberger O, Ye J, Chakravarty EF, Davis MM, and Utz PJ 2015. Tetramers reveal IL-17-secreting CD4+ T cells that are specific for U1–70 in lupus and mixed connective tissue disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112: 3044–3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kyttaris VC, Zhang Z, Kuchroo VK, Oukka M, and Tsokos GC 2010. Cutting edge: IL-23 receptor deficiency prevents the development of lupus nephritis in C57BL/6-lpr/lpr mice. Journal of immunology 184: 4605–4609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Biswas PS, Gupta S, Chang E, Song L, Stirzaker RA, Liao JK, Bhagat G, and Pernis AB 2010. Phosphorylation of IRF4 by ROCK2 regulates IL-17 and IL-21 production and the development of autoimmunity in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation 120: 3280–3295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Amarilyo G, Lourenco EV, Shi FD, and La Cava A 2014. IL-17 promotes murine lupus. Journal of immunology 193: 540–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pisitkun P, Ha HL, Wang H, Claudio E, Tivy CC, Zhou H, Mayadas TN, Illei GG, and Siebenlist U 2012. Interleukin-17 cytokines are critical in development of fatal lupus glomerulonephritis. Immunity 37: 1104–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hsu HC, Yang P, Wang J, Wu Q, Myers R, Chen J, Yi J, Guentert T, Tousson A, Stanus AL, Le TV, Lorenz RG, Xu H, Kolls JK, Carter RH, Chaplin DD, Williams RW, and Mountz JD 2008. Interleukin 17-producing T helper cells and interleukin 17 orchestrate autoreactive germinal center development in autoimmune BXD2 mice. Nature immunology 9: 166–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Summers SA, Odobasic D, Khouri MB, Steinmetz OM, Yang Y, Holdsworth SR, and Kitching AR 2014. Endogenous interleukin (IL)-17A promotes pristane-induced systemic autoimmunity and lupus nephritis induced by pristane. Clinical and experimental immunology 176: 341–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pawaria S, Ramani K, Maers K, Liu Y, Kane LP, Levesque MC, and Biswas PS 2014. Complement component C5a permits the coexistence of pathogenic Th17 cells and type I IFN in lupus. Journal of immunology 193: 3288–3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ramani K, and Biswas PS 2016. Interleukin 17 signaling drives Type I Interferon induced proliferative crescentic glomerulonephritis in lupus-prone mice. Clinical immunology 162: 31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Biswas PS, Aggarwal R, Levesque MC, Maers K, and Ramani K 2015. Type I interferon and T helper 17 cells co-exist and co-regulate disease pathogenesis in lupus patients. International journal of rheumatic diseases 18: 646–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kluger MA, Melderis S, Nosko A, Goerke B, Luig M, Meyer MC, Turner JE, Meyer-Schwesinger C, Wegscheid C, Tiegs G, Stahl RA, Panzer U, and Steinmetz OM 2016. Treg17 cells are programmed by Stat3 to suppress Th17 responses in systemic lupus. Kidney international 89: 158–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wong CK, Lit LC, Tam LS, Li EK, Wong PT, and Lam CW 2008. Hyperproduction of IL-23 and IL-17 in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: implications for Th17-mediated inflammation in auto-immunity. Clinical immunology 127: 385–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yang J, Chu Y, Yang X, Gao D, Zhu L, Yang X, Wan L, and Li M 2009. Th17 and natural Treg cell population dynamics in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and rheumatism 60: 1472–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Abdel Galil SM, Ezzeldin N, and El-Boshy ME 2015. The role of serum IL-17 and IL-6 as biomarkers of disease activity and predictors of remission in patients with lupus nephritis. Cytokine 76: 280–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhao XF, Pan HF, Yuan H, Zhang WH, Li XP, Wang GH, Wu GC, Su H, Pan FM, Li WX, Li LH, Chen GP, and Ye DQ 2010. Increased serum interleukin 17 in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Molecular biology reports 37: 81–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stangou M, Papagianni A, Bantis C, Moisiadis D, Kasimatis S, Spartalis M, Pantzaki A, Efstratiadis G, and Memmos D 2013. Up-regulation of urinary markers predict outcome in IgA nephropathy but their predictive value is influenced by treatment with steroids and azathioprine. Clinical nephrology 80: 203–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lu G, Zhang X, Shen L, Qiao Q, Li Y, Sun J, and Zhang J 2017. CCL20 secreted from IgA1-stimulated human mesangial cells recruits inflammatory Th17 cells in IgA nephropathy. PloS one 12: e0178352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lin JR, Wen J, Zhang H, Wang L, Gou FF, Yang M, and Fan JM 2018. Interleukin-17 promotes the production of underglycosylated IgA1 in DAKIKI cells. Renal failure 40: 60–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Matsumoto K, and Kanmatsuse K 2003. Interleukin-17 stimulates the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines by blood monocytes in patients with IgA nephropathy. Scandinavian journal of urology and nephrology 37: 164–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lin FJ, Jiang GR, Shan JP, Zhu C, Zou J, and Wu XR 2012. Imbalance of regulatory T cells to Th17 cells in IgA nephropathy. Scandinavian journal of clinical and laboratory investigation 72: 221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Leonardi C, Matheson R, Zachariae C, Cameron G, Li L, Edson-Heredia E, Braun D, and Banerjee S 2012. Anti-interleukin-17 monoclonal antibody ixekizumab in chronic plaque psoriasis. The New England journal of medicine 366: 1190–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Papp KA, Leonardi C, Menter A, Ortonne JP, Krueger JG, Kricorian G, Aras G, Li J, Russell CB, Thompson EH, and Baumgartner S 2012. Brodalumab, an anti-interleukin-17-receptor antibody for psoriasis. The New England journal of medicine 366: 1181–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]