Abstract

The impact of the Pulmonary Embolism Response Team (PERT) model on trainee physician education and autonomy over the management of high risk pulmonary embolism (PE) is unknown. A resident and fellow questionnaire was administered 1 year after PERT implementation. A total of 122 physicians were surveyed, and 73 responded. Even after 12 months of interacting with the PERT consultative service, and having formal instruction in high risk PE management, 51% and 49% of respondents underestimated the true 3-month mortality for sub-massive and massive PE, respectively, and 44% were unaware of a common physical exam finding in patients with PE. Comparing before and after PERT implementation, physicians perceived enhanced confidence in identifying (p<0.001), and managing (p=0.003) sub-massive/massive PE, enhanced confidence in treating patients appropriately with systemic thrombolysis (p=0.04), and increased knowledge of indications for systemic thrombolysis and surgical embolectomy (p=0.043 and p<0.001, respectively). Respondents self-reported an increased fund of knowledge of high risk PE pathophysiology (77%), and the perception that a multi-disciplinary team improves the care of patients with high risk PE (89%). Seventy-one percent of respondents favored broad implementation of a PERT similar to an acute myocardial infarction team. Overall, trainee physicians at a large institution perceived an enhanced educational experience while managing PE following PERT implementation, believing the team concept is better for patient care.

Keywords: autonomy, education, massive PE, pulmonary embolism (PE), pulmonary embolism response team (PERT), sub-massive PE, thrombolysis

Introduction

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is the third most common cardiovascular cause of death in the United States.1,2 Diagnosis of PE remains a challenge as PE often presents with non-specific symptoms. Risk stratification plays a crucial role in directing management options for PE. The true risk of adverse clinical events for patients with high risk PE who have a 90-day mortality of 25–50% is often underestimated.3 High risk PE includes massive PE (systolic blood pressure (SBP) < 90 mmHg for at least 15 minutes) and sub-massive PE (SBP > 90 mmHg, but with additional evidence of right heart dysfunction on imaging with or without elevated plasma cardiac biomarkers).4 Various risk stratification tools are available to predict short-term morbidity and mortality for high risk PE.5,6 There are a wide range of therapeutic options available for these high risk patients, often requiring the involvement of multiple specialties. Thus, coordination of care and providing the optimal therapy can be challenging.

The concept of a Pulmonary Embolism Response Team (PERT) has been suggested to address the aforementioned limitations.7,8 A PERT is comprised of a multi-disciplinary group of physicians responsible for expeditious evaluation and treatment of high risk PE patients. By bringing together multiple experts in consultation and to direct patient care for PE, house staff may benefit by receiving teaching from multiple expert perspectives, but they may also feel a structured team evaluation of patients with high risk PE conflicts with their personal practice style. A coincident though unintentional educational benefit at the level of trainee physicians managing patients with high risk PE may emerge in teaching hospitals with a PERT. We sought to evaluate the knowledge of high risk PE and the educational benefit perceived by residents and fellows after PERT implementation by way of a detailed survey.

Methods

The study was approved by the University of Rochester (UR) Research Subjects Review Board (protocol #00068927). The multi-disciplinary PERT at UR, which was started by a vascular medicine physician and cardiologist, is comprised of the following specialties: cardiology, pulmonary medicine, emergency medicine, cardiac surgery, vascular surgery, pharmacy, and interventional radiology. A resident and fellow electronic questionnaire was administered in the following departments: internal medicine, emergency medicine, cardiology, cardiothoracic and vascular surgery, pulmonology, and critical care. Permission from each of the program directors was sought prior to administering the questionnaire; all but one specialty responded to this request. For each PERT activation at UR, the coronary care unit and medical intensive care unit are expected to respond within 15 minutes with the anticipation that, together, their respective expertise allows for a cohesive and thoughtful plan to be implemented within 60 minutes, involving other PERT members only if needed. Trainee physicians therefore were exposed to PERT members from emergency medicine, cardiology, and pulmonary medicine more than other sub-specialties. This was a single center study assessment at a single time point. A questionnaire and a short multiple choice quiz were assigned at the end of the academic year in which a multi-disciplinary PERT had been functioning for 12 months.

Eligible individuals included residents and fellows who were working at UR Medical Center when the survey was administered. Current email addresses were obtained from residency and fellowship coordinators. Two emails were sent – the first explaining the study with the Institutional Review Board-approved form, and a second with the formal survey. A reminder email was sent once weekly for 1 month. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and participants had the right to withdraw at any time without consequence. Upon completion of the survey, participants were asked to submit their responses via the same website. The survey asked the physicians to provide some demographic information and respond to multiple choice questions to assess their general knowledge of PE. Physicians were also asked to respond to statements regarding their perception of PE management before and after implementation of the PERT. We purposefully excluded individuals transitioning from trainee to faculty positions during the academic year, as well as trainee physicians who were involved in implementing the PERT at UR. For the purposes of data representation, ‘high risk PE’ refers to massive and sub-massive PE.

Demographic and survey responses were analyzed using frequency tables and descriptive statistics. The responses to pointed statements based on respondent perception before and after interacting with the PERT were listed according to the Likert scale as follows: strongly disagree = 1, disagree = 2, neutral = 3, agree = 4, strongly agree = 5. This strategy generated a continuous variable which was expressed as mean value and standard deviation of the mean for responses. Binomial testing was employed to assess the respondent general knowledge of PE including mortality risk, treatment strategies available, and knowledge of contraindications to certain treatment options. We compared how respondents perceived their self-reported knowledge base at a single time point, asking them to reflect on their perception before and after PERT implementation. Continuous variables were compared using the independent samples t-test. Chi-squared testing was used to compare categorical variables. Significance was determined as p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Qualitative data were displayed using population size (n) and percent.

Results

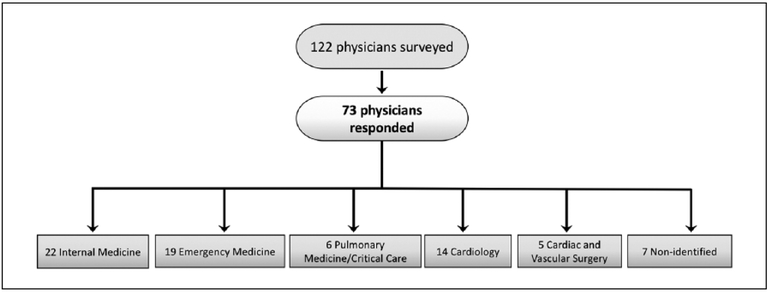

Questionnaires were administered to 122 physicians in which 73 (65%) responded. Among respondents, 30.1% were internal medicine residents, 26% were emergency medicine residents, 19.2% were cardiology fellows, 8.2% were either pulmonary or critical care fellows, 6.8% were cardiothoracic and vascular surgery fellows, and 9.6% elected not to identify their training program (Figure 1). Self-reported demographic information of the respondents is indicated in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Trainee physicians surveyed. Resident physicians and clinical fellows were surveyed by email. A list of multiple choice questions was presented to each subject as well as direct questions based on the physician’s perception before and after implementation of a PERT.

PERT, Pulmonary Embolism Response Team.

Table 1.

Demographics of trainee physicians surveyed.

| Study group (n = 73) | |

|---|---|

| Male/female (n, %) | 37/36, 51%/49% |

| MD/DO (%) | 88%/12% |

| Age group, years | |

| 12–29 (n, %) | 35, 47.9% |

| 30–39 (n, %) | 35, 47.9% |

| 40–49 (n, %) | 3, 4.1% |

| Sub-specialties | |

| Cardiology fellows (n, %) | 14, 19% |

| Emergency medicine residents (n, %) | 19, 26% |

| Internal medicine residents (n. %) | 22, 32% |

| Pulmonary and critical care fellows (n, %) | 6, 8% |

| Cardiothoracic / vascular surgery residents (n, %) | 5, 7% |

| Non-specified (n, %) | 7, 9.6% |

Resident physicians and clinical fellows were surveyed as indicated in the methods section. Of those trainees who responded, most provided demographic information, credentials, and identified their training program, as indicated.

MD, doctor of allopathic medicine; DO, doctor of osteopathic medicine.

The questionnaire in its entirety is included in the Supplemental Appendix. In response to questions regarding general knowledge of PE, most respondents correctly identified the definitions of sub-massive PE (91.2%, p<0.001), massive PE (91.2%, p<0.001) and the meaning of the Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (PESI) score (87.7%, p<0.001). Many respondents failed to correctly identify the 3-month mortality risk for sub-massive PE (49.1% correct), massive PE (50.9% correct). Many respondents were unaware that tachypnea is a very sensitive and common physical exam finding for PE (56.1% correct).

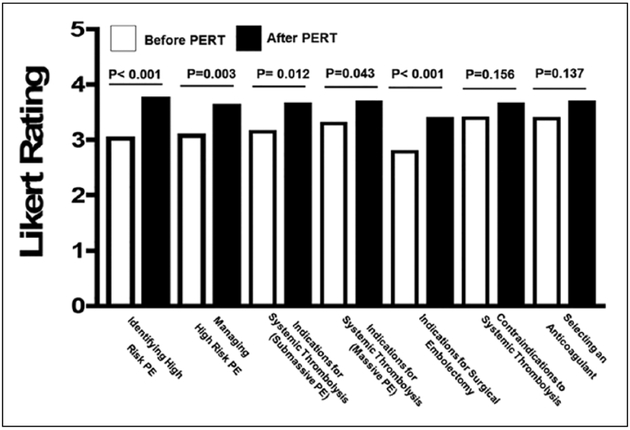

Comparing before and after PERT implementation, Likert-scale responses (Figure 2) showed that physicians’ self-reported increased confidence in identifying high risk PE (3.1 vs 3.8, p<0.001), in managing high risk PE (3.1 vs 3.7, p=0.003), knowing the guidelines for the use of systemic thrombolytic therapy for sub-massive PE (3.2 vs 3.7, p=0.012), massive PE (3.3 vs 3.7, p=0.043), and indications for surgical embolectomy (2.8 vs 3.4, p<0.001). Respondents self-reported no change in awareness of contraindications to the use of systemic thrombolytic agents before and after the PERT (3.4 vs 3.7, p=0.156) or choosing anticoagulants for high risk PE (3.4 vs 3.7, p=0.137). Respondents self-reported an increased awareness of the requirement for parenteral heparin before administering systemic thrombolytic agents for PE (41.5% vs 63.1%, p=0.032), but no change in awareness of which clinical scenarios best warrant the use of Venous-Arterial Extra-Corporeal Membrane Oxygenation (VA-ECMO) (76.9% vs 91.3%, p=0.055) or catheter-directed thrombolysis (90.6% vs 93.5%, p=0.596) for massive PE.

Figure 2.

Trainee physicians’ responses reflecting on the PERT. Multiple choice questions (Likert scale 1–5) indicating physician perceptions before (unshaded columns) and after (shaded columns) PERT implementation.

PE, pulmonary embolism; PERT, Pulmonary Embolism Response Team.

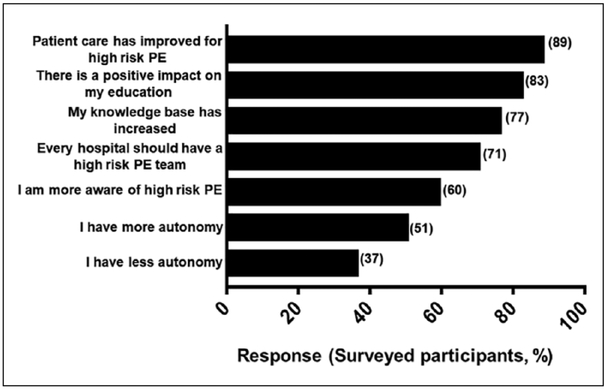

Resident physicians and clinical fellows were asked to respond in the affirmative to direct questions regarding their perception of the PERT and how the PERT affects their autonomy over patient care, their medical education, the quality of patient care delivered, and the hospital effectiveness in managing high risk PE since PERT implementation (Figure 3). Respondents self-reported a mixed perception regarding their autonomy over patient care since PERT implementation when the question was addressed in an affirmative manner; an equal number responded ‘yes’ and ‘no’ when asked if they perceived a change in autonomy. However, when the same question was asked again in a dissenting manner, a 63% majority responded ‘no’ to a perceived loss of autonomy. Respondents did, however, self-report a perceived increase in fund of knowledge (76.6%, p<0.001). They did not self-report an increased awareness of a common clinical sign of PE (59.6%). Respondents self-reported a perception that the PERT improves care of patients with high risk PE (89.4%) and enhances the fund of knowledge for physicians who manage high risk PE (82.6%). A total of 70.8% of respondents indicated that every institution should have a PERT functioning like an acute myocardial infarction team with benchmark metrics that must be met for care of patients acutely, and for follow-up.

Figure 3.

Trainee physicians reflecting on their education. Final indications of trainee perception of the PERT and the effects on their autonomy over patient care, the quality of that care, their medical education, and the hospital effectiveness in managing high risk (sub-massive/massive) PE.

Data are indicated as % affirmative response beside each column. PE, pulmonary embolism; PERT, Pulmonary Embolism Response Team.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report in the literature which considers the impact of a multi-disciplinary PERT on the educational experience of physicians in training. The behavior of individuals interacting with a structured team in a way they never had to previously could potentially impact patient care if the physicians perceive a loss of autonomy, additional call responsibilities, or an enforced team-based consensus decision that is incongruent with their preferred practice style. Our single center study indicates the PERT was in fact positively viewed by trainee physicians. While those who maintain the opinion that an individual physician can effectively manage high risk PE may perceive PERTs as excessive or unnecessary, the voice of trainee physicians in our large academic institution indicates an enhanced educational and patient management experience without a loss of personal autonomy with a PERT.

Consistent with the goals of the National PERT Consortium, efforts directed toward education and research are essential ingredients of a healthy institutional PERT.9 Our data revealed respondents remained quite unaware of the 3-month mortality risk for sub-massive/massive PE and were unaware of common physical exam findings for PE. This signal was detected in spite of the adopted educational measures by the founding members of our institutional PERT; including didactic sessions, institutional grand rounds, and bedside teaching in various aspects of the PERT algorithm. Alarmingly, post-graduate house staff – even after implementation of a PERT – indicated a lack of confidence in identifying relative and absolute contraindications to the use of systemic thrombolytic agents.

The responsibility for implementing and educating trainee physicians in the PERT algorithm at our institution lay heavily within the divisions of cardiology and emergency medicine, which may have introduced unintentional bias into teaching our house staff and fellows about high risk PE. These findings therefore suggest that every member of the PERT – both physicians and surgeons – should devote a portion of their time to formal and informal teaching in the area they are most experienced in.

Patient care for those afflicted with high risk PE – as is the case with patients with vascular disease – tends to be higher quality when physicians and surgeons skilled in acute care, management of complex medical conditions, hemodynamic monitoring, and with procedural competence provide a thoughtful, respectful, and expedited opinion on how best to manage the patient.10

The concept of a multi-specialty team in managing patients with PE has gained popularity over the past few years in the United States and has now become an international phenomenon.11 The PERT concept was introduced to address some of the limitations in management of PE, including difficulties in the diagnosis and risk stratification, as well as variations among different specialties in their expertise in managing patients with sub-massive and massive PE.12 Since the first PERT was born in 2012 at the Massachusetts General Hospital, interest and enthusiasm in developing PERTs has been noted, with promising initial reports on the impact of PERTs in improving patients’ outcomes.11,13 Despite PE being a common medical condition, physicians – as observed in our data – continue to underestimate the true mortality risk in a patient presenting with sub-massive and massive PE. The design of PERTs should include equal attention to improving educational outcomes for physicians belonging to a PERT.14 The PERT Consortium has a goal of educating physicians and the general public regarding PE diagnosis, treatment, and care.9 A knowledge deficit in physicians may be an important variable to consider alongside team-based care when determining the true effect of PERTs on patient outcomes. We propose that greater care should be given to educational endeavors before developing an institutional PERT algorithm, and launching a PERT.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. This survey was conducted once and only after implementation of a PERT, which raises the possibility of recall bias in respondents. While this may be the first investigation of educational aspects of the PERT, we propose that the survey be conducted prior to PERT implementation and then again after 1–2 years in order to assess areas of improvement. Despite multiple reminders, the response rate to our survey was 65%. This raises the real possibility that physicians electing not to participate may have equally strong and perhaps negative opinions of our PERT and, if purposefully choosing not to engage in a team-based decision, clinical management decisions and ultimately patient outcomes may be affected. Lastly, this survey was conducted only in a single center, which may introduces additional biases due to the University of Rochester’s unique educational style, including a focus on the biopsychosocial aspects of medical care.15 Similar surveys conducted at other centers – both community and university-based – are encouraged to determine the generalizability of our observations.

Conclusion

While PERTs may be perceived as excessive or unnecessary in favor of an individual physician managing patients with high risk PE, the voice of trainee physicians in a large academic institution indicates an enhanced educational and patient management experience for sub-massive and massive PE without a loss of personal autonomy. The majority of our physicians and surgeons who participated concur that a team-based approach to high risk acute PE management is superior to decisions made by one physician.

Supplementary Material

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: NIH grants K08HL128856 and HL120200 to SJC.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online with the article.

References

- 1.Castelli R, Tarsia P, Tantardini C, et al. Syncope in patients with pulmonary embolism: Comparison between patients with syncope as the presenting symptom of pulmonary embolism and patients with pulmonary embolism without syncope. Vasc Med 2003; 8: 257–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hawley PC, Hawley MP. Difficulties in diagnosing pulmonary embolism in the obese patient: A literature review. Vasc Med 2011; 16: 444–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corrigan D, Prucnal C, Kabrhel C. Pulmonary embolism: The diagnosis, risk-stratification, treatment and disposition of emergency department patients. Clin Exp Emerg Med 2016; 3: 117–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaff MR, McMurtry MS, Archer SL, et al. Management of massive and submassive pulmonary embolism, iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis, and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 2011; 123: 1788–1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, et al. 2014 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Endorsed by the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 3033–3073.25173341 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torbicki A, Perrier A, Konstantinides S, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2008; 29: 2276–2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sista AK, Friedman OA, Dou E, et al. A pulmonary embolism response team’s initial 20 month experience treating 87 patients with submassive and massive pulmonary embolism. Vasc Med 2018; 23: 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deadmon EK, Giordano NJ, Rosenfield K, et al. Comparison of emergency department patients to inpatients receiving a pulmonary embolism response team (PERT) activation. Acad Emerg Med 2017; 24: 814–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnes GD, Kabrhel C, Courtney DM, et al. Diversity in the pulmonary embolism response team model: An organizational survey of the National PERT Consortium members. Chest 2016; 150: 1414–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cameron SJ. Vascular medicine: The eye cannot see what the mind does not know. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 65: 2760–2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Provias T, Dudzinski DM, Jaff MR, et al. The Massachusetts General Hospital Pulmonary Embolism Response Team (MGH PERT): Creation of a multidisciplinary program to improve care of patients with massive and submassive pulmonary embolism. Hosp Pract 2014; 42: 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez-Lopez J, Channick R. The pulmonary embolism response team: What is the ideal model? Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 38: 51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kabrhel C, Rosovsky R, Channick R, et al. A multidiscipli-nary pulmonary embolism response team: Initial 30-month experience with a novel approach to delivery of care to patients with submassive and massive pulmonary embolism. Chest 2016; 150: 384–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dudzinski DM, Piazza G. Multidisciplinary pulmonary embolism response teams. Circulation 2016; 133: 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engel GL. The biopsychosocial model and medical education. N Engl J Med 1982; 306: 802–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.