Abstract

Platinum anticancer agents are essential components in chemotherapeutic regimens for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients ineligible for targeted therapy. However, platinum-based regimens have reached a plateau of therapeutic efficacy; therefore, it is critical to implement novel approaches for improvement. The hexosamine biosynthesis pathway (HBP), which produces amino-sugar N-acetyl-glucosamine (GlcNAc) for protein glycosylation, is important for protein function and cell survival. Here we show a beneficial effect by combination of cisplatin with HBP inhibition. Expression of glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase (GFAT), the rate-limiting enzyme of HBP, was increased in NSCLC cell lines and tissues. Pharmacological inhibition of GFAT activity or knockdown of GFAT impaired cell proliferation and exerted a synergistic or additive cytotoxicity to the cells treated with cisplatin. Mechanistically, GFAT positively regulated the expression of binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP; also known as glucose-regulated protein 78, GRP78), an endoplasmic reticulum chaperone involved in unfolded protein response. Suppressing GFAT activity resulted in downregulation of BiP that activated inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), a sensor protein of unfolded protein response, and exacerbated cisplatin-induced cell apoptosis. These data identify GFAT-mediated HBP as a target for improving platinum-based chemotherapy for NSCLC.

Keywords: hexosamine biosynthesis pathway, glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase, cisplatin, binding immunoglobulin protein, non-small cell lung cancer

Introduction

Lung cancer remains the most deadly malignancy worldwide. Currently, in first-line treatment, cytotoxic chemotherapy with platinum-based doublets is the standard of care for advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients not having sensitizing gene alterations eligible for targeted therapy (for example, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitors). Although recent advances in immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors offer new options for a subset of patients[1], the majority of lung cancer patients with advanced diseases, including patients whose diseases progress after targeted therapy, still rely on conventional cytotoxic agents. Unfortunately, the therapeutic efficacy of platinum-based regimens has reached a plateau[1]. Therefore, it is critical to develop novel and practical combination therapies to improve the efficacy of platinum agents.

The profound alteration in metabolism in cancer cells has long been regarded as a therapeutic opportunity. This notion has become more attractive with increasingly in-depth understanding of cancer metabolism[2]. The hexosamine biosynthesis pathway (HBP) is a minor glucose-utilization pathway that produces uridine dinucleotide phosphate-N-acetyl-glucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) for protein glycosylation including O-GlcNAcylation (the covalent attachment of a single GlcNAc to serine or threonine residues)[3]. Glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase (GFAT) catalyzes the first and committed step of HBP that determines the hexosamine flux[4,5]. The pathway has been linked to the development of some cancer types, but little is known about the role of HBP in the response of cancer cells to chemotherapy. In this study, we demonstrate that the activity of HBP was elevated in lung cancer cells, as evidenced by the increases of GFAT expression and protein O-GlcNAcylation. Inhibition of HBP with GFAT inhibitors or siRNA impaired cell proliferation, and had additive or synergistic effects with cisplatin on various lung cancer cell lines. We further show that GFAT inhibition reduced the expression of BiP and activated IRE1α, which enhanced cisplatin-induced apoptosis. Thus, HBP deserves further exploitation for combination therapy with platinum agents for lung cancer.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

Cisplatin (cis-diammineplatinum(II) dichloride (Cat. No. P4394), 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine (DON, D2141), azaserine (A4142), D-(+)-glucosamine hydrochloride (G1515) and 2-deoxy-D-glucose (D8375) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) and dissolved in distilled water. Tunicamycin (T7765) and thapsigargin (T9033) were also Sigma products and prepared with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). IRE1 RNase inhibitor A106 (531399) was from Millipore (Burlington, MA) and dissolved in DMSO. The commercial antibodies for the following proteins were used : GFAT1 (ab125069), GFAT2 (ab176206), RL2 (ab2739, recognizing O-GlcNAc), phospho-IRE1α (serine 724, ab48187) from Abcam (Cambridge, MA); caspase 3 p17 (sc-271028, recognizing both uncleaved and cleaved forms), BiP/GRP78(glucose-regulated protein 78; sc-1050) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); CHOP (2895), Phospho-eIF2α (serine 51, 9721), BiP/GRP78 (3177) from Cell Signaling; β-actin (A2103) and β-tubulin (T6074) from Sigma; PARP1 (BML-SA248) from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY) and XBP1s (647502) from Biolegend (San Diego, CA).

Cell culture

Lung cancer cell lines (adenocarcinoma: A549, Calu-3, H23, H358, H460, H1299, H1568, H1792, H1975 and H2009; squamous cell carcinoma: H520, H2170, SK-MES1 and SW900) were purchase from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and maintained in RPMI-1640 medium with 2 mM of glutamine and antibiotics penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 µg/ml) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Immortalized human bronchial epithelial cell (HBEC) lines HBEC2, HBEC3 and HBEC14 were kind gifts from Drs. Jerry W. Shay and John D. Minna (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX) and have been described previously[6]. The medium for HBECs was keratinocyte serum-free medium (K-SFM) with supplements (50 µg/ml of bovine pituitary extract and 5 ng/ml of epidermal growth factor; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and antibiotics. HEK293 cells were purchased from ATCC and maintained in DMEM with high glucose (Thermo Fisher) and antibiotics. Lung cancer cell lines were authenticated by short tandem repeat (STR) DNA profiling using commercial service (Genetica Cell Line Testing, Burlington, NC). HBEC lines and HEK293 were not authenticated.

Reverse transcription and polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cell lines using RNeasy RNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Reverse transcription was performed with ImProm-II Reverse Transcription System (A3800; Promega, Madison, WI). The primers with the following sequences were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (San Diego, CA): GFAT1, 5’-CTG TGA GAC CCA AAG GTT GAT A-3’ (forward) and 5’-GGG AGC TAC TGG CAG AAA TAA-3’ (reverse); GFAT2, 5’-GGA TGC TAC ATG GGA AGA GAA G-3’ (forward) and 5’-GAC TTC AGG ACA CAG AGA AAC A-3’; and β-actin, 5’-CCA GCC TTC CTT CCT GGG CAT-3’ (forward) and 5’-AGG AGC AAT GAT CTT GAT CTT CAT T-3’ (reverse). The amplification conditions were: 95°C, 40 sec; 55°C, 40 sec; 72 °C, 40 sec, and 28 cycles for both GFAT1 and GFAT2, and 20 cycles for β-actin. The products were run in 2.5% agarose with 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide, observed and photographed with ChemiDoc™ Imaging System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). In addition, twenty-four pairs of lung tissues (12 adenocarcinomas, 12 squamous cell carcinomas and corresponding distant normal lung tissues) were randomly selected from an tumor bank and subjected to TaqMan assay for GFAT gene expression as described previously[7]. Briefly, total RNA extracted with Trizol (Invitrogen) was used for reverse transcription with High Capacity cDNA RT kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Real-time PCR was performed with predesigned primers (Assay ID: GFPT1, Hs00899865_m1; GFPT2, Hs01049561_m1) and ABI PRISM 7900HT (Applied Biosystems). Amplification was done in duplicate for each gene in individual samples. Results were normalized to corresponding β-actin simultaneously amplified and then expressed as fold increase (cancer over normal lung tissue).

Plasmids and siRNA transfection

Wild type human GFAT1 plasmid (Cat. No. EX-T0173-M67) was purchased from GeneCopoeia (Rochville, MD). The pCMV BiP-Myc-KDEL-wt plasmid was a gift from Dr. Ron Prywes (Plasmid No. 27164; Addgene, Watertown, MA)[8]. Human siRNAs targeting GFAT1 (s5708) and GFAT2 (s19305) as well as negative control siRNA (4390844) were from Thermo Fisher. Transfection of plasmids was carried out using Fugene HD (Promega, Madison, WI) at a DNA (µg): Fugene HD (µl) ratio of 1:3. For RNA interference, siRNA was incubated with INTERFERin (Polyplus-Transfection, New York, USA) at the amount of 4 µl /well of a 12-well plate according to the protocol from the manufacturer.

Establishment of BiP promoter reporter cell line and luciferase assay

A549 cells were co-transfected with pGL-BiP-P plasmid, which expresses luciferase under the control of a fragment (- 958 to +99) of human BiP promoter and was kindly provided by Dr. Jairaj K. Acharya (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD)[9], and pcDNA3.1-C for neomycin resistance. Stable expressing cells were selected by G418 resistance and luciferase level over parental cells. Cells were then treated with DON for 24 h. Luciferase assay was carried out using reagents (E4530) from Promega and a luminometer (Turner Designs, San Jose, CA). Light readings were normalized to respective protein concentrations of the samples and expressed as relative levels.

Cell viability assay and analysis of drug combination

Cells were incubated with 40 µg/ml MTT [(3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] for 2 h. After three washes with phosphate-buffered saline, DMSO was added to the wells. The color intensity (OD570) of the solutions was determined with a plate reader. Cell viability was expressed as percentages with the reading of the control set as 100 (percent). In some experiments, relative cell viability was further calculated as indicated in individual figure legends. For DON and cisplatin combination treatment, cells were treated for 3 days. IC50 for individual drug and combination index (CI) was calculated using CompuSyn software and interpreted according to the Chou-Talalay Method (CI = 1, additive effect; CI < 1, synergism; and CI > 1, antagonism) [10].

Western blot

Whole cell lysate was prepared with M2 lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH7.6; 0.5% NP-40, 250 mM NaCl, 3 mM ethylene glycol-bis(aminoethyl ether)-tetraacetic acid, 3 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM sodium vanadate and 1 µg/ml leupeptin). Protein amount was quantitated with protein quantitation reagent from Bio-Rad. Equal amount of protein from each sample was electrophoresed on 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate - polyacrylamide gel and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. After blocking with 5% skim-milk, the membrane was incubated with primary antibody overnight followed by washing and incubation of corresponding secondary antibody. Protein signal was visualized and recorded using enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and ChemiDot™ imaging system.

Statistics

Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± SD (standard deviation). Statistics was done with GraphPad Prism 5.0 software. Unpaired t test was used to compare two means in cell-based assays, and paired t test was used for mRNA expression results of lung cancer/normal tissue samples. All tests were two-tailed. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Overexpression of GFAT in lung cancer cell lines and tissues

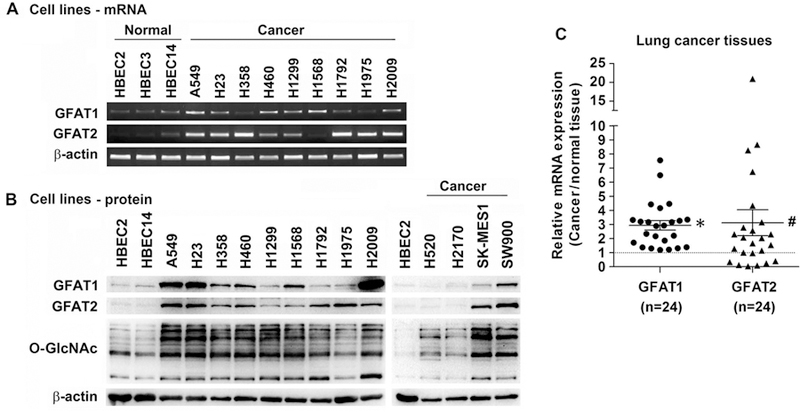

GFAT has two isozymes, GFAT1[11] and GFAT2[12], encoded by different genes (GFPT1 and GFPT2, respectively; for simplicity, in this work both genes and proteins were referred to as GFAT1 and GFAT2 and as GFAT collectively). Human GFAT1 and GFAT2 have 75.6% homology in their protein sequences, presumably catalyze identical reactions without reported difference in catalytic activity, but have distinct distribution in normal tissues[12] and likely differential responses to stimuli[13–15]. We first examined the expression of GFAT in various lung cancer cell lines. Compared with that of HBECs, all cancer cells lines had higher expression of GFAT mRNA, and correspondingly, GFAT protein levels and protein O-GlcNAcylation (Figure 1A and 1B), indicative of increased GFAT activity. To validate the findings in cell lines, we interrogated GFAT mRNA expression in lung cancer tissues, and found that average GFAT mRNA level was increased compared with that of the corresponding normal tissues (Figure 1C). When examined individually, the majority of lung cancers (9/12 in adenocarcinomas and 11/12 in squamous cell carcinomas) had over two-fold increase of at least one isozyme (not shown).

Figure 1.

Increased expression of GFAT in lung cancer cell lines and tissues. (A) Expression of GFAT mRNA in HBECs and lung cancer cell lines. Total RNA was extracted from cell lines; cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription and used for PCR with specific primers for GFAT1, GFAT2, and β-actin as loading control. Products were run in agarose gel with EB. (B) GFAT protein and O-GlcNAcylation levels in HBECs and lung cancer cell lines as examined with Western blot in total cell lysates. β-Actin was probed as a loading control. (C) GFAT mRNA expression in human lung cancer tissues examined with TaqMan assay. GFAT expression in 12 adenocarcinomas, 12 squamous cell carcinomas, and their corresponding distant normal tissues was normalized to respective β-actin, and then cancer over normal expression was calculated. * P<0.01; # P<0.05, in paired comparison with normal tissues as 1.

Inhibition of GFAT is synergistic or additive to cisplatin cytotoxicity in lung cancer cells

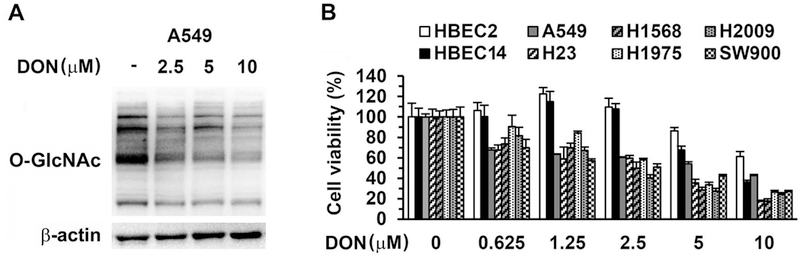

Having confirmed that GFAT was overexpressed in lung cancer cells, we used DON, a glutamine analog and an irreversible GFAT inhibitor[13,16–18], to investigate the potential of targeting the HBP pathway. DON displayed its effect on GFAT by decreasing protein O-GlcNAcylation in a dose-dependent manner in A549 cells (Figure 2A). DON also inhibited lung cancer cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner. Notably, cancer cells were more sensitive to DON treatment than HBECs, indicating that cancer cells are more dependent on HBP activity for proliferation (Figure 2B). We then tested DON in combination with cisplatin in three NSCLC cell lines with various concentrations. DON demonstrated mostly an additive effect (CI=1) in inhibiting cancer cell growth in A549 cells (Table 1), but synergistic effects (CI<1) in Calu-3 and H2009 cells (Table 2). Therefore, DON was able to enhance the efficacy of cisplatin in all the cancer cell lines tested in certain concentration combinations.

Figure 2.

Effects of combined treatment of DON and cisplatin in lung cancer cells. (A) A549 cells were incubated with DON for 24 h and protein O-GlcNAcylation was detected with Western blot with β-actin as loading control. (B) HBECs and lung cancer cell lines were treated in triplicate with various concentrations of DON for 48 h and viable cells were determined with MTT assay.

Table 1.

CI of DON and cisplatin in A549 cells

| DON (µM) |

Cisplatin (µM) |

Inhibition (%) |

CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.625 | 2.5 | 33.3 | 1.23 |

| 0.625 | 5.0 | 53.6 | 1.17 |

| 1.25 | 2.5 | 48.1 | 0.96 |

| 1.25 | 5.0 | 62.9 | 1.00 |

| 1.25 | 10.0 | 48.4 | 2.69 |

| 2.5 | 2.5 | 63.0 | 0.77 |

| 2.5 | 5.0 | 68.4 | 0.98 |

| 5.0 | 5.0 | 74.3 | 0.98 |

| 5.0 | 10.0 | 83.4 | 1.06 |

| 10.0 | 5.0 | 83.0 | 0.84 |

| 10.0 | 10.0 | 94.2 | 0.53 |

IC50: DON, 3.7 µM; cisplatin, 4.5 µM.

Table 2.

CI of DON and cisplatin in Calu-3 and H2009 cells

| DON (µM) |

Cisplatin (µM) |

Calu-3 |

H2009 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition (%) |

CI | Inhibition (%) |

CI | ||||

| 0.75 | 2.0 | 29.7 | 1.25 | 52.3 | 0.66 | ||

| 0.75 | 4.0 | 55.3 | 0.96 | 73.8 | 0.61 | ||

| 1.5 | 2.0 | 47.0 | 0.80 | 49.1 | 0.91 | ||

| 1.5 | 4.0 | 63.7 | 0.79 | 75.8 | 0.62 | ||

| 3.0 | 2.0 | 35.2 | 1.56 | 57.9 | 0.93 | ||

| 3.0 | 4.0 | 54.6 | 1.25 | 87.7 | 0.39 | ||

| 3.0 | 8.0 | 88.2 | 0.49 | 91.5 | 0.52 | ||

| 6.0 | 2.0 | 65.2 | 0.81 | 77.8 | 0.61 | ||

| 6.0 | 4.0 | 70.0 | 0.94 | 85.4 | 0.56 | ||

| 6.0 | 8.0 | 91.5 | 0.42 | 90.0 | 0.66 | ||

| 12.0 | 2.0 | 86.5 | 0.47 | 85.5 | 0.59 | ||

| 12.0 | 4.0 | 90.0 | 0.44 | 91.5 | 0.46 | ||

| 12.0 | 8.0 | 96.5 | 0.25 | 93.6 | 0.55 | ||

IC50: Calu-3: DON, 7.0 µM; cisplatin, 3.9 µM.

H2009: DON, 4.2 µM; cisplatin, 3.8 µM.

Inhibition of GFAT exacerbates cisplatin-induced apoptosis in cancer cells

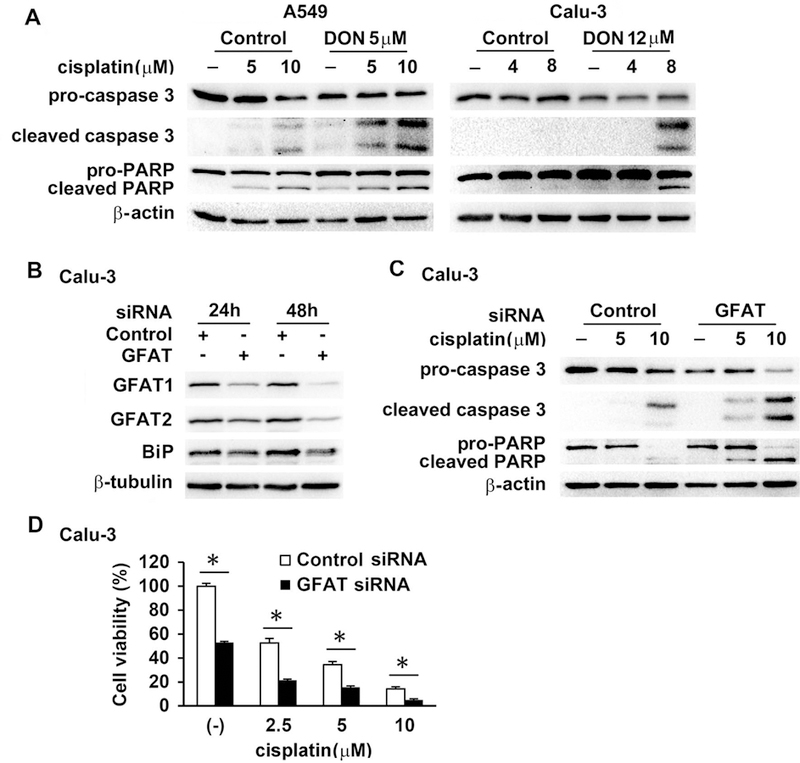

Cisplatin is a DNA cross-linking agent that induces DNA damage and apoptosis in cancer cells. DON greatly increased cisplatin-induced cleavage of caspase 3 and PARP1, a substrate of caspase 3, both of which are hallmarks of apoptosis, in A549 and Calu-3 cells (Figure 3A). These results were confirmed with similar data obtained by transfection of GFAT siRNA instead of DON treatment prior to cisplatin exposure (Figure 3B, 3C, 3D, and data not shown). Thus, inhibition of GFAT function augmented the apoptotic induction in cisplatin-treated cancer cells.

Figure 3.

GFAT inhibition enhanced cisplatin-induced apoptosis. (A) A549 and Calu-3 cells were incubated with DON for 30 min prior to cisplatin for another 24 h. Protein expression was determined in total cell lysates with Western blot. (B and C) Calu-3 cells were transfected with control siRNA (15 nM) or GFAT siRNA (GFAT1, 5 nM; GFAT2, 10 nM) for 24 h and 48 h and then harvested (B), or for 24 h followed by treatment with cisplatin for another 24 h (C). Western blot was performed to examine protein levels. (D) Calu-3 cells were transfected with siRNAs as in (C) and then treated with cisplatin for 4 days. Cell viability was determined with MTT assay. Experiment was done in triplicate. * P<0.01.

GFAT regulates BiP expression

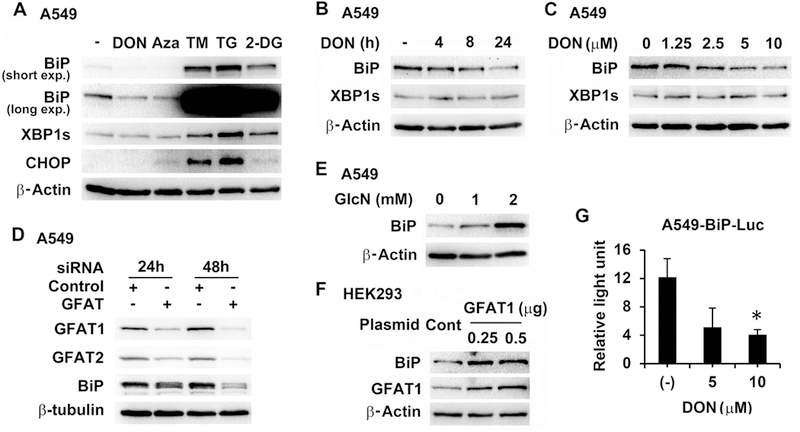

We then examined the mechanisms underlying the potentiation of anticancer activity of cisplatin by HBP inhibition. Previously, BiP, a major endoplasmic reticulum (ER) chaperone, was shown to be induced by GFAT1 overexpression in hepatoma cells. The induction was attributed to ER stress[19]. BiP has also been demonstrated to contribute to cisplatin resistance[20,21]. Therefore, we further investigated the relationship of GFAT activity and BiP expression. DON and azaserine, another glutamine analog GFAT inhibitor, inhibited BiP expression without induction of spliced X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1s) and CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein homologous protein (CHOP) expression, two indicators of ER stress, in contrast to three ER stress inducers, tunicamycin (glycosylation inhibitor), thapsigargin (ER Ca2+ pump inhibitor) and 2-deoxy-glucose (2-DG, glycolysis inhibitor) (Figure 4A). Further, DON inhibited BiP expression in different cell lines (A549 and H2009) in a dose- and time-dependent manner, again without induction of XBP1 splicing (Figure 4B, 4C and data not shown). Additionally, knockdown of GFAT reduced basal BiP level (Figure 3B and Figure 4D); conversely, treating cells with HBP product, glucosamine, or overexpression of GFAT1, induced BiP expression (Figure 4E and 4F). GFAT appeared to regulate BiP transcription, because DON treatment reduced luciferase activity in A549 cells stably transfected with a BiP promoter-driven reporter plasmid (Figure 4G). Taken together, these data demonstrated that GFAT/HBP positively regulated BiP expression.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of GFAT decreased BiP expression. (A) A549 cells were treated with DON (5 µM), azaserine (Aza, 5 µM), tunicamycin (TM, 0.2 µM), thapsigargin (TG, 0.1 µM) or 2-DG (2.5 mM) overnight. (B and C) A549 cells were treated with 5 µM of DON for different times (B) or with various concentrations of DON (C) for 24 h. (D) A549 cells were transfected with control siRNA (15 nM) or GFAT siRNA (GFAT1, 5 nM; GFAT2, 10 nM) for 24 h and 48 h. (E) A549 cells were incubated with glucosamine (GlcN) for 24 h. (F) HEK293 cells were transfected with control vector (0.5 µg) or GFAT1 expressing plasmid for 24 h. Western blot was carried out for protein analysis (A, B, C, D, E, and F). (G) A549-BiP-Luc cells stably expressing BiP promoter-driven luciferase were treated with DON for 24 h. Luciferase activities were measured, normalized to corresponding protein amount and expressed as relative light unit. * P<0.05 compared with untreated (−).

Reduction of BiP activates IRE1α that contributes to enhanced cisplatin-induced cell death in GFAT knockdown cells

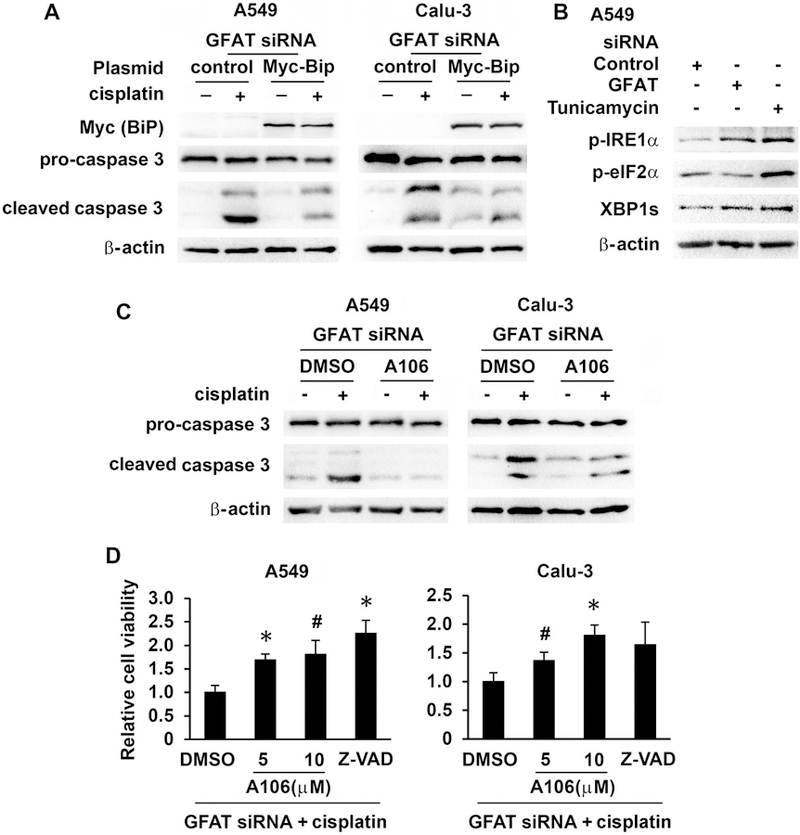

We further interrogated the role of BiP in cisplatin-induced cell death under GFAT inhibition. Lung cancer cells were transfected with GFAT siRNA, followed by BiP transfection and then cisplatin exposure. BiP restoration partially protected cells from cisplatin-induced apoptosis (Figure 5A and data not shown). BiP binds to unfolded or misfolded proteins and releases UPR sensor proteins IRE1, PERK (protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase), and ATF6 (activating transcription factor 6) to initiate UPR. Downregulation of BiP can result in activation of UPR[9]. DON at the concentration used (up to 10 µM), as well as GFAT knockdown, did not trigger XBP1 splicing catalyzed by activated IRE1 and CHOP induction (Figure 4 and data not shown). However, phosphorylation of IRE1α, but not eIF2α (downstream of PERK), was increased after GFAT knockdown (Figure 5B). Consistently, A106, an IRE1α RNase inhibitor[22], partially reduced cisplatin-induced apoptosis in cancer cells (Figure 5C and 5D), similar to findings in a previous report[23] showing a cytoprotective property of IRE1α RNase inhibitors (including STF-083010, from which A106 was derived)[22,24]. We used A106 at 10 µM because at this concentration, the drug effectively suppressed tunicamycin-induced XBP1s expression, but not cell proliferation (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Decreased BiP expression activated IRE1α which contributed to enhanced cisplatin-induced apoptosis in GFAT knockdown cells. (A) A549 and Calu-3 cells were transfected with GFAT siRNA (5 nM of GFAT1 and 10 nM of GFAT2). Six hours after siRNA transfection, cells were further transfected with control vector (0.5 µg) or BiP expressing plasmid (0.5 µg). The next day, cells were treated with cisplatin for 24 h. Protein expression was detected with Western blot. (B) A549 cells were transfected with control (15 nM) or GFAT siRNA (5 nM of GFAT1 and 10 nM of GFAT2) for 24 h or treated with tunicamycin (1 µM) for 2 h. Protein expression was examined with Western blot. (C) A549 and Calu-3 cells were transfected with GFAT siRNA as in (B), and then further treated with DMSO or A106 (10 µM) for 30 min prior to cisplatin (10 µM) for another 24 h. Protein expression was detected with Western blot. (D) A549 and Calu-3 cells were treated as in (C), but with an additional group treated with pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD (10 µM) and the incubation time for cisplatin was 3 days. Cell viability was determined with MTT assay. Results from triplicate samples were presented as relative cell viability. * P<0.01; # P<0.05, compared with DMSO control.

Discussion

HBP has been shown to play critical roles in cell physiology and pathology, including cancer development [25–28]. However, in cancer biology study, protein O-GlcNAcylation and the enzymes carrying out the cycling of this modification have long been the focus, while GFAT attracted much less attention. High activity of GFAT in lung and other tumor tissues was observed three decades ago[29,30]. In recent years, accumulating evidence revealed a tumor-promoting function of GFAT. Increased expression of GFAT was detected in human breast[16], prostate[31], colon[32], pancreatic[33,34], and bile duct[35] cancer tissues. The GFAT expression was correlated with worse patient survival in breast[16], pancreatic[33] and liver[36] cancer. Furthermore, GFAT was demonstrated to drive malignant cell growth in vitro and in vivo, and to promote migration and invasion of various cancer cells in vitro[16,32,33,36,37]. However, opposite to the above trend, GFAT1 was shown to exhibit tumor suppressive activities in gastric cancer[38], suggesting possible cell-type specific functions of the enzyme in cancer biology.

In our current work, we first showed that GFAT was prevalently overexpressed in human lung cancer cell lines and tissues. We further showed that DON treatment and GFAT knockdown inhibited the proliferation of lung cancer cells. Additionally, we found cancer cells were more sensitive to DON when compared with HBECs, which indicates cancer cells’ dependence on HBP. Therefore, our data support a potential role of HBP/GFAT in lung cancer development and progression, similar to the majority of the findings in various solid cancers.

The major goal of this study was to determine if GFAT inhibition was able to enhance the anticancer efficacy of cisplatin in lung cancer cells. In various lung cancer cell lines, an additive or synergic cytotoxicity was observed for cisplatin with DON in different dose combinations, which was confirmed with GFAT siRNA transfection instead of DON. Therefore, combining cisplatin with GFAT or HBP inhibition could be a viable option that deserves further assessment.

HBP is a cell protective pathway, which is best illustrated by its activation in cardiac myocytes in ischemic heart diseases[13,14,39]. Inhibition of HBP may enhance cisplatin cytotoxicity through various mechanisms. GFAT activity is closely correlated to the levels of GlcNAc and protein O-GlcNAcylation[17,40–44]. Inhibition of GFAT reduces protein glycosylation including O-GlcNAcylation, a modification contributing to cisplatin resistance in lung cancer cells[45]. Further, the HBP pathway controls the expression of many genes transcriptionally or post-transciptionally. We found that GFAT positively regulated the expression of BiP, which was supported by a previous report[19]. The finding that restoration of BiP in GFAT knockdown cells reduced cisplatin-induced apoptosis clearly implicates BiP in modulating cisplatin susceptibility by GFAT. How HBP regulates gene expression is not well understood; O-GlcNAcylation of transcription factors, histones and other proteins[46,47] may be one of the mechanisms. O-GlcNAcylation of transcription factors important for BiP expression has been reported[40,48–50], but whether this mechanism plays a role in our setting remains to be determined.

BiP is a major ER chaperone involved in the initiation, execution and termination of UPR, an adaptive pathway activated under cell stresses, which consists of three branches with IRE1α, PERK and ATF6 as respective sensors. UPR is critical for cell survival in stress conditions; however, UPR can trigger cell death in unresolved or prolonged ER stress[51]. Downregulation of BiP activates UPR[9]. Hyperactivation of IRE1 can induce apoptosis; conversely, pharmacological inhibition of IRE1α augments cell survival[23,52]. We detected the activation (phosphorylation) of IRE1α but not eIF2α in GFAT knockdown cells. In addition, cisplatin-induced apoptosis of these cells was partially prevented by blocking IRE1α RNAase activity with A106. However, we did not observe increased XBP1s levels and CHOP expression in single or combined treatment with relatively low concentrations of cisplatin. These results suggest that the XBP1 signaling pathway was not activated in our experimental settings, and that IRE1-mediated downstream pathway(s) other than XBP1, such as RNA decay[52], may play a role in cell death in the combined treatment.

Our findings also bring up the possibility of reassessing DON as a cancer therapeutic agent. Originally isolated from Streptomyces in the mid-1950s, DON was tested in preclinical and clinical settings as an anticancer compound. While well-tolerated, the drug as a mono-therapy showed mixed responses in Phase I and II trials, which appeared to reduce the enthusiasm. However, most of those trials were done decades ago, and DON was used alone and as an inhibitor of nucleotide synthesis. The doses and dosing schedules may not be optimal, particularly if DON is considered as a targeting agent. Furthermore, while mono-therapy with DON may not be effective, its combination with other standard agents could maximize the advantage of this compound. The results in this study strongly endorse this hypothesis. Notably, the combinational cytotoxicity effect was observed with low concentrations of DON and clinical achievable doses of cisplatin. This implies that reduced activity of HBP, which is highly active in cancer cells, could increase their sensitivity to platinum anti-cancer agents. Thus, the “old” drug DON may gain a new life when combined with other anticancer agents in clinical application. More specific GFAT inhibitors are currently in development, which would be expected to offer higher activity with lower toxicity[53,54]. It is important to identify potential biomarkers, which may include the expression of GFAT, for patient selection for combination therapy with GFAT-targeting regimens.

In summary, we show that GFAT expression was increased in human lung cancer cell lines and tissues. Inhibition of GFAT activity with DON or GFAT siRNA suppressed cell proliferation and had a synergic or additive effect with cisplatin in inducing cancer cell death. Furthermore, we showed that inhibition of GFAT down-regulated BiP expression and activated IRE1α, which contributed to enhanced cisplatin-induced cell death. Together, our data substantiate further studies testing the combination of cisplatin and HBP inhibition, particularly targeting GFAT, for improving lung cancer chemotherapy.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Jairaj K. Acharya (National Cancer Institute, NIH) for providing BiP promoter reporter plasmid and Dr. Ron Prywes (Columbia University) for the donation of BiP expressing plasmid to Addgene.

Grant supports

This work was partially supported by NCI/NIH R03CA223637 (W.C), R21CA193633 (Y.L) and P30CA11800 (S.B).

Abbreviations

- ATF6

activating transcription factor 6

- BiP

binding immunoglobulin protein

- CHOP

CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein homologous protein

- CI

combination index

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DON

6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine

- eIF2α

eukaryotic initiating factor 2α

- GFAT

glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase

- GlcNAc

N-acetyl-glucosamine

- HBEC

human bronchial epithelial cell

- HBP

hexosamine biosynthesis pathway

- IRE1α

inositol-requiring enzyme 1α

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- PERK

protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase

- TG

thapsigargin

- TM

tunicamycin

- UPR

unfolded protein response

- XBP1s

spliced X-box binding protein 1

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aisner DL et al. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 5.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN 2017;15(4):504–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hay N Reprogramming glucose metabolism in cancer: can it be exploited for cancer therapy? Nature reviews 2016;16(10):635–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bond MR, Hanover JA. A little sugar goes a long way: the cell biology of O-GlcNAc. The Journal of cell biology 2015;208(7):869–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banerjee PS, Hart GW, Cho JW. Chemical approaches to study O-GlcNAcylation. Chemical Society reviews 2013;42(10):4345–4357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milewski S Glucosamine-6-phosphate synthase--the multi-facets enzyme. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2002;1597(2):173–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramirez RD, Sheridan S, Girard L et al. Immortalization of human bronchial epithelial cells in the absence of viral oncoproteins. Cancer Res 2004;64(24):9027–9034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tellez CS, Juri DE, Do K et al. EMT and stem cell-like properties associated with miR-205 and miR-200 epigenetic silencing are early manifestations during carcinogen-induced transformation of human lung epithelial cells. Cancer Res 2011;71(8):3087–3097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen J, Chen X, Hendershot L, Prywes R. ER stress regulation of ATF6 localization by dissociation of BiP/GRP78 binding and unmasking of Golgi localization signals. Developmental cell 2002;3(1):99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kosakowska-Cholody T, Lin J, Srideshikan SM, Scheffer L, Tarasova NI, Acharya JK. HKH40A downregulates GRP78/BiP expression in cancer cells. Cell death & disease 2014;5:e1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou TC. Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method. Cancer research 2010;70(2):440–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKnight GL, Mudri SL, Mathewes SL et al. Molecular cloning, cDNA sequence, and bacterial expression of human glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase. The Journal of biological chemistry 1992;267(35):25208–25212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oki T, Yamazaki K, Kuromitsu J, Okada M, Tanaka I. cDNA cloning and mapping of a novel subtype of glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase (GFAT2) in human and mouse. Genomics 1999;57(2):227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang ZV, Deng Y, Gao N et al. Spliced X-box binding protein 1 couples the unfolded protein response to hexosamine biosynthetic pathway. Cell 2014;156(6):1179–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lunde IG, Aronsen JM, Kvaloy H et al. Cardiac O-GlcNAc signaling is increased in hypertrophy and heart failure. Physiological genomics 2011;44(2):162–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dai W, Dierschke SK, Toro AL, Dennis MD. Consumption of a high fat diet promotes protein O-GlcNAcylation in mouse retina via NR4A1-dependent GFAT2 expression. Biochimica et biophysica acta Molecular basis of disease 2018;1864(12):3568–3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Onodera Y, Nam JM, Bissell MJ. Increased sugar uptake promotes oncogenesis via EPAC/RAP1 and O-GlcNAc pathways. The Journal of clinical investigation 2014;124(1):367–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolm-Litty V, Sauer U, Nerlich A, Lehmann R, Schleicher ED. High glucose-induced transforming growth factor beta1 production is mediated by the hexosamine pathway in porcine glomerular mesangial cells. The Journal of clinical investigation 1998;101(1):160–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.James LR, Tang D, Ingram A et al. Flux through the hexosamine pathway is a determinant of nuclear factor kappaB- dependent promoter activation. Diabetes 2002;51(4):1146–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sage AT, Walter LA, Shi Y et al. Hexosamine biosynthesis pathway flux promotes endoplasmic reticulum stress, lipid accumulation, and inflammatory gene expression in hepatic cells. American journal of physiology 2010;298(3):E499–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang CC, Mao ZG, Avery-Kiejda KA, Wade M, Hersey P, Zhang XD. Glucose-regulated protein 78 antagonizes cisplatin and adriamycin in human melanoma cells. Carcinogenesis 2009;30(2):197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mhaidat NM, Alzoubi KH, Khabour OF, Banihani MN, Al-Balas QA, Swaidan S. GRP78 regulates sensitivity of human colorectal cancer cells to DNA targeting agents. Cytotechnology 2016;68(3):459–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kharabi Masouleh B, Geng H, Hurtz C et al. Mechanistic rationale for targeting the unfolded protein response in pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2014;111(21):E2219–2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghosh R, Wang L, Wang ES et al. Allosteric inhibition of the IRE1alpha RNase preserves cell viability and function during endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell 2014;158(3):534–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kriss CL, Pinilla-Ibarz JA, Mailloux AW et al. Overexpression of TCL1 activates the endoplasmic reticulum stress response: a novel mechanism of leukemic progression in mice. Blood 2012;120(5):1027–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanover JA, Krause MW, Love DC. The hexosamine signaling pathway: O-GlcNAc cycling in feast or famine. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2010;1800(2):80–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dassanayaka S, Jones SP. O-GlcNAc and the cardiovascular system. Pharmacology & therapeutics 2014;142(1):62–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slawson C, Copeland RJ, Hart GW. O-GlcNAc signaling: a metabolic link between diabetes and cancer? Trends in biochemical sciences 2010;35(10):547–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Love DC, Krause MW, Hanover JA. O-GlcNAc cycling: emerging roles in development and epigenetics. Seminars in cell & developmental biology 2010;21(6):646–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsuiki S, Miyagi T. Carcinofetal alterations in glucosamine-6-phosphate synthetase. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1975;259:298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greengard O, Herzfeld A. The undifferentiated enzymic composition of human fetal lung and pulmonary tumors. Cancer research 1977;37(3):884–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Itkonen HM, Minner S, Guldvik IJ et al. O-GlcNAc transferase integrates metabolic pathways to regulate the stability of c-MYC in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer research 2013;73(16):5277–5287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vasconcelos-Dos-Santos A, Loponte HF, Mantuano NR et al. Hyperglycemia exacerbates colon cancer malignancy through hexosamine biosynthetic pathway. Oncogenesis 2017;6(3):e306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang C, Peng P, Li L et al. High expression of GFAT1 predicts poor prognosis in patients with pancreatic cancer. Scientific reports 2016;6:39044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guillaumond F, Leca J, Olivares O et al. Strengthened glycolysis under hypoxia supports tumor symbiosis and hexosamine biosynthesis in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2013;110(10):3919–3924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phoomak C, Vaeteewoottacharn K, Silsirivanit A et al. High glucose levels boost the aggressiveness of highly metastatic cholangiocarcinoma cells via O-GlcNAcylation. Scientific reports 2017;7:43842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li L, Shao M, Peng P et al. High expression of GFAT1 predicts unfavorable prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 2017;8(12):19205–19217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ying H, Kimmelman AC, Lyssiotis CA et al. Oncogenic Kras maintains pancreatic tumors through regulation of anabolic glucose metabolism. Cell 2012;149(3):656–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duan F, Jia D, Zhao J et al. Loss of GFAT1 promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and predicts unfavorable prognosis in gastric cancer. Oncotarget 2016;7(25):38427–38439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lehmann LH, Jebessa ZH, Kreusser MM et al. A proteolytic fragment of histone deacetylase 4 protects the heart from failure by regulating the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway. Nature medicine 2018;24(1):62–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jokela TA, Makkonen KM, Oikari S et al. Cellular content of UDP-N-acetylhexosamines controls hyaluronan synthase 2 expression and correlates with O-linked N-acetylglucosamine modification of transcription factors YY1 and SP1. The Journal of biological chemistry 2011;286(38):33632–33640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weigert C, Klopfer K, Kausch C et al. Palmitate-induced activation of the hexosamine pathway in human myotubes: increased expression of glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase. Diabetes 2003;52(3):650–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weigert C, Brodbeck K, Lehmann R, Haring HU, Schleicher ED. Overexpression of glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate-amidotransferase induces transforming growth factor-beta1 synthesis in NIH-3T3 fibroblasts. FEBS letters 2001;488(1–2):95–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawanaka K, Han DH, Gao J, Nolte LA, Holloszy JO. Development of glucose-induced insulin resistance in muscle requires protein synthesis. The Journal of biological chemistry 2001;276(23):20101–20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Veerababu G, Tang J, Hoffman RT et al. Overexpression of glutamine: fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase in the liver of transgenic mice results in enhanced glycogen storage, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes 2000;49(12):2070–2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luanpitpong S, Angsutararux P, Samart P, Chanthra N, Chanvorachote P, Issaragrisil S. Hyper-O-GlcNAcylation induces cisplatin resistance via regulation of p53 and c-Myc in human lung carcinoma. Scientific reports 2017;7(1):10607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zachara NE, Hart GW. Cell signaling, the essential role of O-GlcNAc! Biochimica et biophysica acta 2006;1761(5–6):599–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hardiville S, Hart GW. Nutrient regulation of gene expression by O-GlcNAcylation of chromatin. Current opinion in chemical biology 2016;33:88–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li WW, Hsiung Y, Zhou Y, Roy B, Lee AS. Induction of the mammalian GRP78/BiP gene by Ca2+ depletion and formation of aberrant proteins: activation of the conserved stress-inducible grp core promoter element by the human nuclear factor YY1. Molecular and cellular biology 1997;17(1):54–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baumeister P, Luo S, Skarnes WC et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induction of the Grp78/BiP promoter: activating mechanisms mediated by YY1 and its interactive chromatin modifiers. Molecular and cellular biology 2005;25(11):4529–4540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hiromura M, Choi CH, Sabourin NA, Jones H, Bachvarov D, Usheva A. YY1 is regulated by O-linked N-acetylglucosaminylation (O-glcNAcylation). The Journal of biological chemistry 2003;278(16):14046–14052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sano R, Reed JC. ER stress-induced cell death mechanisms. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2013;1833(12):3460–3470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grootjans J, Kaser A, Kaufman RJ, Blumberg RS. The unfolded protein response in immunity and inflammation. Nature reviews Immunology 2016;16(8):469–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Qian Y, Ahmad M, Chen S et al. Discovery of 1-arylcarbonyl-6,7-dimethoxyisoquinoline derivatives as glutamine fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase (GFAT) inhibitors. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters 2011;21(21):6264–6269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vyas B, Silakari O, Bahia MS, Singh B. Glutamine: fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase (GFAT): homology modelling and designing of new inhibitors using pharmacophore and docking based hierarchical virtual screening protocol. SAR and QSAR in environmental research 2013;24(9):733–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]