Abstract

RAD51 is the central protein in homologous recombination repair (HR), where it first binds ssDNA and then catalyzes strand invasion via a D-loop intermediate. Additionally, RAD51 plays a role in faithful DNA replication by protecting stalled replication forks; this requires RAD51 to bind DNA but may not require the strand invasion activity of RAD51. We previously described a small-molecule inhibitor of RAD51 named RI(dl)-2 (RAD51 inhibitor of D-loop formation #2 hereafter called 2h), which inhibits D-loop activity while sparing ssDNA binding. However, 2h is limited in its ability to inhibit HR in vivo, preventing only about 50% of total HR events in cells. We sought to improve upon this by performing a structure-activity-relationship (SAR) campaign for more potent analogs of 2h. Most compounds were prepared from 1-(2-aminophenyl)pyrroles by forming the quinoxaline moiety either by condensation with aldehydes, then dehydrogenation of the resulting 4,5-dihydro intermediates, or by condensation with N,N’-carbonyldiimidazole, chlorination, and installation of the 4-substituent through Suzuki-Miyaura coupling. Many analogs exhibited enhanced activity against human RAD51, but in several of these compounds the increased inhibition was due to the introduction of dsDNA intercalation activity. We developed a sensitive assay to measure dsDNA intercalation, and identified two analogs of 2h that promote complete HR inhibition in cells while exerting minimal intercalation activity.

Keywords: Biological activity, Cancer, DNA repair, Inhibitors, Structure-activity relationships

Graphical Abstract

We previously described a small-molecule inhibitor of RAD51, which inhibits D-loop activity while sparing the ssDNA binding function. The resulting lead compound, however, was limited in its ability to completely inhibit HR in vivo. Here we employed a structure-activity-relationship (SAR) campaign that led to more potent analogs.

Introduction

Homologous recombination (HR) is an essential DNA repair process, which ensures genomic stability by repairing DNA double strand breaks (DSBs). Unlike other pathways of DSB repair like the error-prone non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) pathway, HR repairs DNA damage by utilizing an undamaged homologous DNA template to guide the repair process.[1–2] Initiation of HR requires the processing of DSB ends to generate a 3’ single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) tail at the site of DNA damage, which is subsequently coated with RAD51 to form a helical nucleoprotein filament. This resulting RAD51 nucleofilament is capable of searching for a homologous DNA sequence and invading it to form a joint molecule intermediate, termed a D-loop. Additional related proteins subsequently promote accurate DNA synthesis using the undamaged homologous sequence as a template.

In addition to its role in DSB repair, RAD51 nucleofilaments also serve a critical function in protecting stalled DNA replication forks from MRE11-mediated degradation.[3–4] RAD51 helps accomplish this by promoting the reversal of replication forks into four-way junctions (or so called ‘chicken feet’), by re-annealing the parental DNA strands and promoting annealing of nascent DNA strands.[5] Although some uncertainty remains regarding the influence this process has in cellular resistance to DNA damaging treatments, recent work from Maria Jasin suggests that fork protection plays only a minor role in the repair of cisplatin-induced DNA damage.[6–7]

RAD51 is commonly over-expressed in various types of human cancer cells[8–9], leading to elevated HR efficiency and associated resistance to oncologic therapies.[10–13] Inhibition of RAD51 with siRNA or chemical antagonists can overcome this resistance to therapy, thereby rendering tumor cells more susceptible to chemotherapy and radiotherapy.[14–16] Several small molecule RAD51 inhibitors have been described, most of which act by preventing the formation of RAD51 filaments on ssDNA.[14, 17–20] It is important to note, however, that complete loss of RAD51 function eliminates both of its known functions: DSB repair and replication fork stabilization. Therefore, we generated a novel class of RAD51 inhibitors, capable of preventing D-loop formation (and hence HR-mediated DSB repair) while permitting assembly of RAD51 at stalled replication forks.[21]

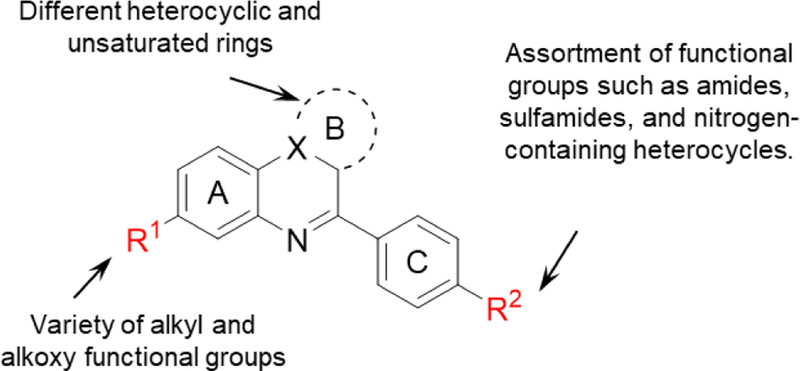

The preferred compound from our initial campaign (RI(dl)-2, hereafter termed compound 2h) was proven capable of inhibiting RAD51’s D-loop activity while having minimal effects on RAD51’s ssDNA binding activity.[21] While 2h is capable of inhibiting most HR events within the first 24 hours following the induction of a DSB, we noted that it is less effective at blocking HR events that occur at later time points. Therefore, we sought to develop improved compounds that inhibit total HR events to a greater degree. Our SAR campaign (summarized in Figure 1) sought to access a large diversity of analogs while maintaining ease of synthesis, and towards this goal explored substitution in the carbocyclic portion of the quinoxaline ring system (ring A) and modifications to the pyrrole ring (ring B) and the 4-aryl group (ring C). Modifications of the latter type eventually became the focus of the present work. Several compounds were identified that were more potent inhibitors of RAD51 protein. However, many of these more potent inhibitors acquired significant DNA intercalation activity and associated cellular toxicity; therefore, we employed a sensitive and quantitative assay to exclude compounds exhibiting this off-target activity. The resulting optimized compounds offer an improved ability to block HR in vivo while retaining specific inhibition of RAD51’s D-loop activity, sparing RAD51-ssDNA binding activity, and showing minimal DNA intercalation activity.

Figure 1.

Proposed modifications of 2h.

Results and Discussion

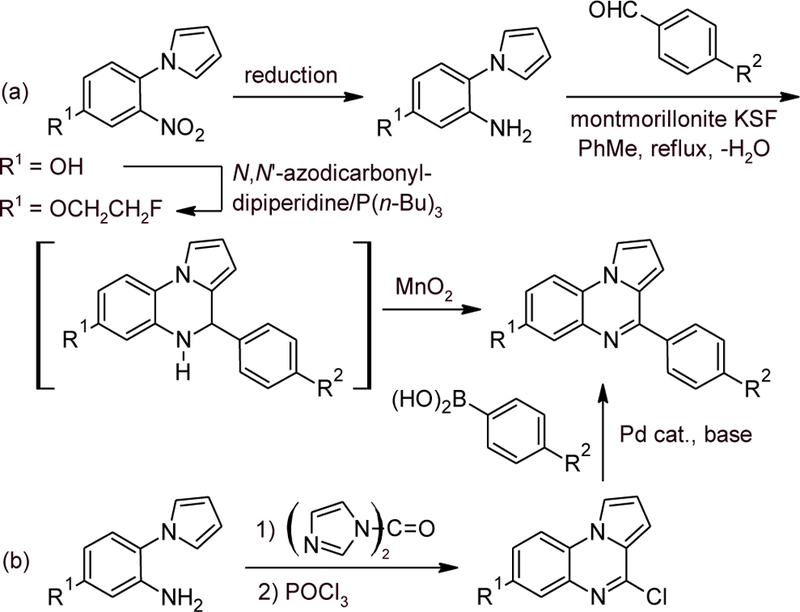

General Synthetic Approach.

Scheme 1 illustrates the generic methods employed in synthesizing the compounds of this study. In most cases, a modification of the reported synthetic approach[21] was employed (route a). The introduction of the 2-fluoroethoxy group through a Mitsunobu reaction gave improved yields when the modified reagent, N,N’-azodicarbonyldipiperidine/P(n-Bu)3,[22] was substituted for the traditional reagent, diethylazodicarboxylate/PPh3. The generation of the pyrrolo[1,2-a]quinoxaline ring system by reaction of 1-(2-aminophenyl)pyrroles with aldehydes requires acid catalysis, and in our earlier work, anhydrous AlCl3 was employed. The inconvenience of handling this highly moisture-sensitive material, especially on a small scale, induced us to search for alternatives. After some experimentation, the commercial, acid-treated clay mineral, montmorillonite KSF (and to a lesser extent, montmorillonite K10), was found suitable for this purpose. The reaction is best performed in boiling toluene with continuous removal of the generated water, and in favorable cases affords yields up to 90% after oxidation of the resulting 4,5-dihydro intermediate with activated MnO2. The heterogeneous reagents are simply filtered off after completion of the reaction. For a number of target compounds, it was advantageous to preform the tricyclic parent structure without the attached aryl group and to arylate subsequently via a Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reaction (route b). Syntheses of compounds with modified B rings follow this coupling approach as well. The syntheses were in many cases completed by a final modification of the substituent R2. A nitro group was chosen as the precursor to not only primary but also several substituted amines. N-monoalkyl derivatives were formed in only moderate yields by reductive alkylation of the primary amines, but this approach nevertheless appears preferable to the previously employed dealkylation of N,N-dialkyl derivatives in the course of the MnO2 oxidation.

Scheme 1.

Generic approaches to pyrrolo[1,2-a]quinoxalines.

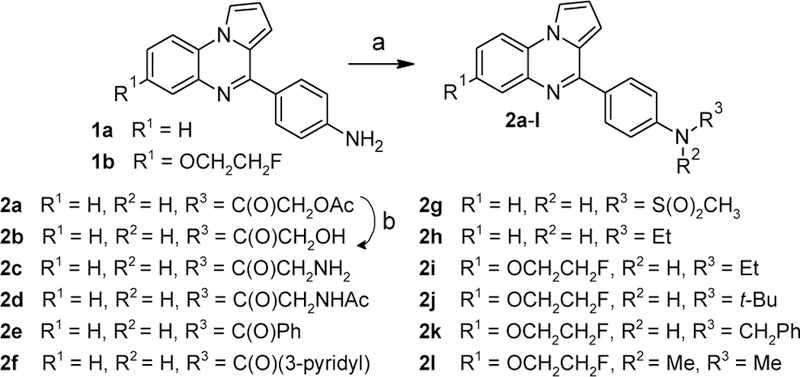

Modification of Ring C.

Anilines 1a and 1b were derivatized into a variety of carboxamides, sulfonamides, and N-alkylation products (Scheme 2). The amides 2a and 2c-f were obtained by reacting anilines 1a and 1b with the appropriate carboxylic acid in the presence of HATU[23] and N,N-diisopropylethylamine. Hydrolysis of 2a under basic conditions afforded the free alcohol 2b. Reaction of the aniline 1a with methanesulfonyl chloride provided the sulfonamide 2g. The N-ethyl derivates 2h and 2i, the N-benzyl derivative 2k, and the N,N-dimethyl derivative 2l were obtained by reductive alkylation of anilines 1a and 1b with sodium triacetoxyborohydride[24] and acetaldehyde, benzaldehyde, and formaldehyde, respectively. The N-tert-butyl substituted amine 2j was accessed by reaction of aniline 1b with tert-butyl 2,2,2-trichloroacetimidate and copper triflate in nitromethane.[25]

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of compounds 2a-i. Reagents and conditions: (a) For 2a,c-f: carboxylic acid, HATU, N,N-diisopropylethylamine, DMF, 50 °C, 11–78%; for 2g: methanesulfonyl chloride, pyridine, CH2Cl2, rt, 9%; for 2h,i,k,l: aldehyde, NaBH(OAc)3, Na2SO4, CH2Cl2, rt, 44–81%; for 2j: tert-butyl 2,2,2-trichloroacetimidate, cat. Cu(OTf)2, nitromethane, rt, 16%; (b) 2M aq. NaOH/MeOH/THF, rt, 83%.

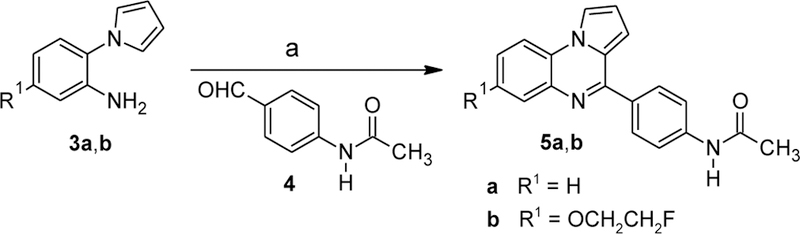

The N-acetyl derivatives 5a,b were synthesized from the corresponding N-(2-aminophenyl)pyrroles 3a,b by reaction with 4-acetamidobenzaldehyde (4) in the presence of montmorillonite K10 (Scheme 3). The initial mixtures of the desired products 5a,b with their 4,5-dihydro derivatives (a result of partial air oxidation of the latter) were treated with MnO2 to provide the fully oxidized amides.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of compounds 5a-b. Reagents and conditions: (a) montmorillonite K10, toluene, reflux, then MnO2, CHCl3, reflux, 6–19%.

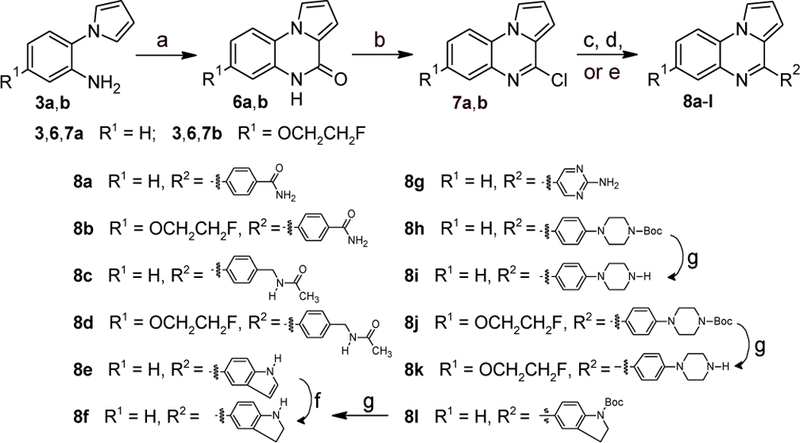

Functionalization of ring C was further explored by Suzuki-Miyaura coupling of aryl chlorides 6a and 6b with boronic acids (Scheme 4). Initial attempts with Pd(PPh3)4 as catalyst[26] provided mostly low yields of the desired products. Changing the catalyst system to a trialkylphosphine ligand, tricyclohexylphosphine (PCy3), with a Pd(0) source[27–28] provided higher yields of the desired biaryls. The carboxamides 8a,b and acetamidomethyl derivatives 8c,d were synthesized in good yields under these conditions. Coupling of indole-5-boronic acid with 6a using Pd(PPh3)4 as catalyst provided a moderate yield of 8e, and subsequent reduction of the indole moiety with NaBH3CN[29] provided indoline 8f. As a side reaction, reduction of the C(4)=N double bond in the pyrroloquinoxaline moiety was observed, and we found it more efficient to prepare 8f via its N-Boc derivative 8l, which resulted from coupling of 6a with the appropriate pinacolboronate. Pyrimidine 8g was accessed in low yield with the Pd(0)/PCy3 catalyst system using 2-aminopyrimidine-5-boronic acid as the coupling partner. The Pd(0)/PCy3 catalyst system provided also good yields of the N-Boc-piperidine derivatives 8h and 8j. Removal of the Boc groups with trifluoroacetic acid provided the desired free amines 8f, 8i, and 8k.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of compounds 8a-i. Reagents and conditions: (a) CDI, o-dichlorobenzene, reflux; (b) POCl3, reflux, 70–95% over 2 steps; (c) for 8a-d,g,h,j: R2B(OH)2, aq. K3PO4, cat. Pd2(dba)3/PCy3, dioxane, 99 °C, 16–94%; (d) for 8e: Na2CO3, cat. Pd(PPh3)4, toluene/EtOH/H2O (15:1:4), reflux, 44%; (e) for 8l: pinacol N-Boc-indoline-5-boronate, aq. K3PO4, cat. Pd2(dba)3/PCy3, dioxane, 99 °C, 91%; (f) NaBH3CN, AcOH, rt, 21%; (g) TFA, CH2Cl2, rt, 64–81%.

An additional variety of substitutions on ring C were examined for the fluoroethoxy-substituted ring A as shown in Scheme 5. The aryl bromide 9 was obtained through a variant of our clay-catalyzed cyclization reaction employing the dimethyl acetal rather than the free aldehyde and distilling off the MeOH formed. Cu-catalyzed C-N coupling reactions of 9 with 2-pyrrolidone, pyrazole, imidazole,[30] and ethanolamine[31] provided 10a, 10b, 10c, and 10e, respectively. The morpholine derivative 10d was accessed via a Pd-catalyzed coupling of 9 with morpholine[32]. The ethylene glycol derivative 10f was synthesized via a Cu-catalyzed C-O coupling reaction of 9 with ethylene glycol. Cu-catalyzed cyanation[33] of 9 provided the nitrile 10g. The homologous nitrile 10i was accessed via coupling of 9 with trimethylsilylacetonitrile.[34] Subsequent borane reduction of either nitrile provided the amines 10h and 10j, respectively, in only moderate yields, the main complication again being reduction of the C(4)=N double bond.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of compounds 10a-j. Reagents and conditions: (a) p-bromobenzaldehyde dimethyl acetal, montmorillonite KSF, 1,2,4-trichlorobenzene, 100–120 °C; MnO2, CHCl3, reflux, 79%; (b) for 10a-c: nitrogen-containing building block, K2CO3, cat. CuI/hexamethylenetetramine, DMF, 140 °C, 14–69%; (c) for 10d: morpholine, cat. Pd(OAc)2/Xantphos, toluene, 100 °C, 61%; (d) for 10e: 2-aminoethanol, K3PO4, cat. CuI/L-proline, DMSO, 90 °C, 48%; (e) for 10f: ethylene glycol, K3PO4, cat. CuI/8-hydroxyquinoline, 110 °C, 28%; (f) for 10g: K4[Fe(CN)6], cat. CuI, 1-methylimidazole, 160 °C, 47%; (g) for 10i: Me3SiCH2CN, ZnF2, cat. Pd2dba3/Xantphos, DMF, 100 °C, 51%; (h) BH3·THF, rt, 36–43%.

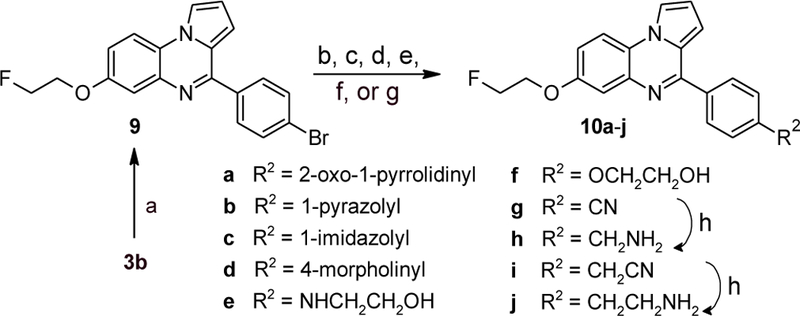

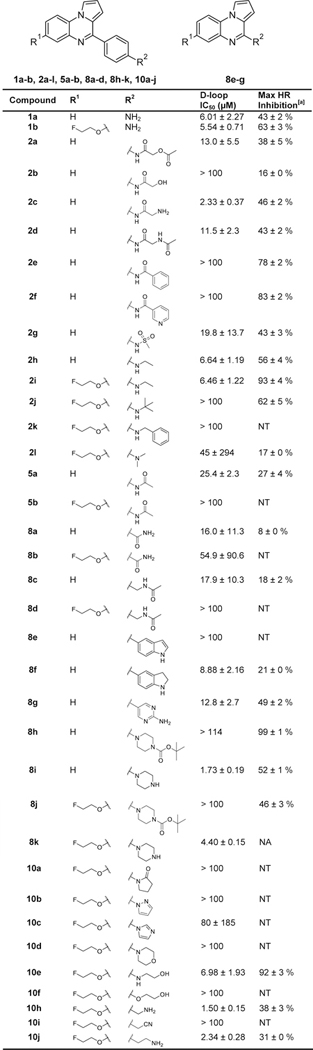

We used the gel-based D-loop assay to measure the ability of compounds to inhibit the homologous strand exchange activity of purified human RAD51 protein.[21] Compounds that showed significant inhibition of D-loop activity in this biochemical assay were prioritized for testing in the DR-GFP assay, which measures HR activity in cells.[35] In this assay, 293-HEK cells containing an integrated DR-GFP reporter are transfected with a plasmid that expresses the I-SceI endonuclease, which generates a DSB in the DR-GFP reporter cassette. Cells are subsequently grown for 48 hours in the presence of candidate small molecules. Results of these assays are displayed in Table 1, Supporting Information Figure 1, and Supporting Information Figure 2, demonstrating that in most cases compounds with R1 = fluoroethoxy showed little difference in their inhibitory activity against purified RAD51 compared to otherwise identical compounds without this substituent. However, for 1a and 2h, introduction of a 7-fluoroethoxy substituent yielded compounds that showed greater inhibition of cellular HR (compare 1a to 1b and 2h to 2i). Additionally, the fluoroethoxy-substituted compound 10e showed strong inhibition of cellular HR similar to 2i. Finally, all aromatic R2 substituents except in the case of 8f and 8g resulted in a loss of RAD51 D-loop inhibitory activity. Other bulky modifications to R2 such as those on 8h and 10d resulted in a loss of activity, suggesting that steric hinderance at this site may contribute to the lack of RAD51 inhibition by these compounds.

Table 1.

Summary of Ring C Modifications. Measurements are reported as the indicated values ± standard error, with each data set testing at least six compound concentrations. NT = Not tested. NA = Not enough cells recovered for testing due to high compound toxicity.

|

HR inhibition observed at the lesser of either the maximum tested concentration of 40 μM or the maximum tolerated dose (20 μM for 10h, 10 μM for 8i and 10j, and 5 μM for 8k).

Modification of Ring B.

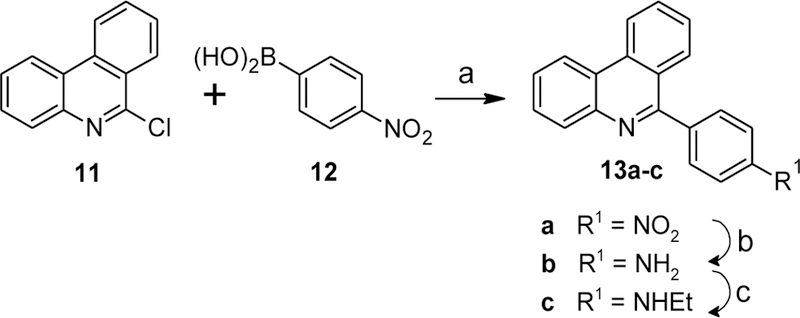

This ring was replaced with various aromatics as shown in Schemes 6–8. Reacting commercially available 6-chlorophenanthridine with 4-nitrobenzeneboronic acid under standard Suzuki-Miyaura coupling conditions yielded 13a (Scheme 6). Reduction of the nitro group via catalytic hydrogenation provided 13b, and subsequent reductive alkylation of the aniline with acetaldehyde provided the N-ethyl derivative 13c.

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of compounds 13a-c. Reagents and conditions: (a) Na2CO3, cat. Pd(PPh3)4, toluene/EtOH/H2O (15:1:4), reflux, 43%; (b) H2 (1 bar), 20% Pd(OH)2/C, MeOH, 81%; (c) CH3CHO, NaBH(OAc)3, Na2SO4, CH2Cl2, rt, 51%.

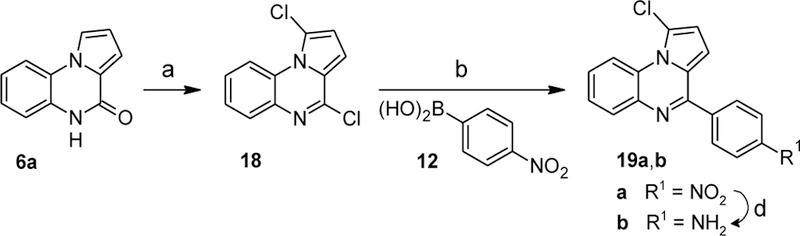

Scheme 8.

Synthesis of compounds 19a,b. Reagents and conditions: (a) PCl5, POCl3, reflux, 41%; (b) Na2CO3, cat. Pd(PPh3)4, toluene/EtOH/H2O (15:1:4), 100 °C; (d) SnCl2·H2O, 1-propanol/chlorobenzene (1:1), 90 °C, 28% over 3 steps.

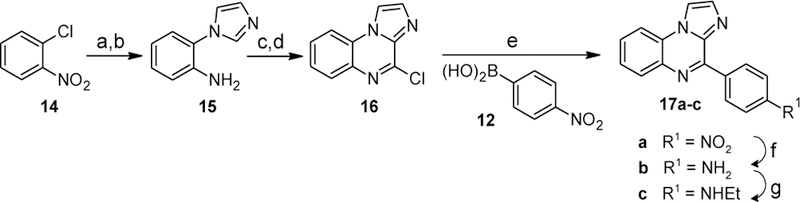

Replacement of ring B with an imidazole ring was accomplished as shown in Scheme 7. Copper-catalyzed coupling of imidazole with 2-chloronitrobenzene (14) followed by hydrogenation of the nitro group yielded 2-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)aniline (15). Reaction of this intermediate with N,N’-carbonyldiimidazole (CDI) followed by chlorination with POCl3 yielded 4-chloroimidazo[1,2-a]quinoxaline (16). Suzuki-Miyaura coupling of 16 with 4-nitrobenzeneboronic acid (12) provided compound 17a. Hydrogenation of the nitro group afforded the aniline 17b, and subsequent reductive alkylation with acetaldehyde and sodium cyanoborohydride provided the N-ethyl derivative 17c in moderate yield.

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of compounds 17a-c. Reagents and conditions: (a) imidazole, potassium tert-butoxide, cat. CuI/benzotriazole, DMSO, 120 °C, 44%; (b) H2 (1 bar), 20% Pd(OH)2/C, MeOH, 100%; (c) CDI, o-dichlorobenzene, reflux, 2 h; (d) POCl3, reflux, 15 h, 55% over 2 steps; (e) Na2CO3, cat. Pd(PPh3)4, toluene/EtOH/H2O (15:1:4), 100 °C; (f) H2 (1 bar), 20% Pd(OH)2/C, MeOH, rt, 45% over 2 steps; (g) CH3CHO, NaBH(OAc)3, Na2SO4, CH2Cl2, rt, 51%.

Ring B was further modified by introducing a chloro substituent into the 1-position of the parent pyrrolo(1,2-a)quinoxaline as shown in Scheme 8. Reacting intermediate 6a with PCl5[36] provided a dichlorinated intermediate 18 which upon coupling with boronic acid 12 under Suzuki-Miyaura conditions yielded the nitroarene 19a. Reduction of the nitro group afforded aniline 19b.

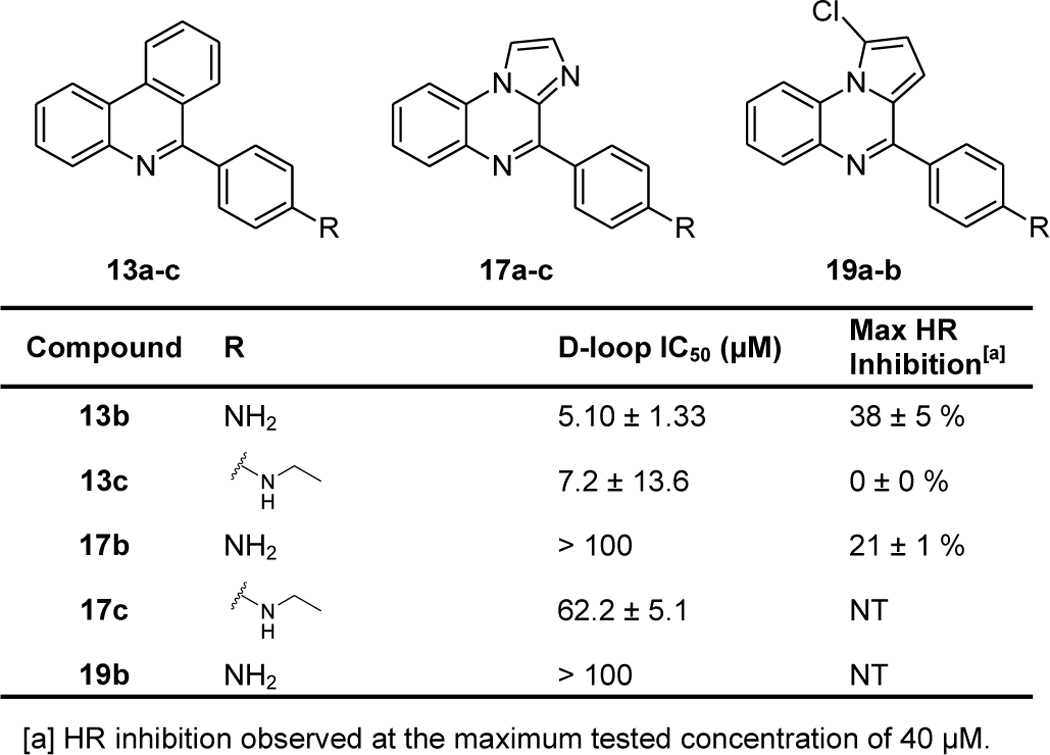

We again utilized used the biochemical D-loop assay to measure the ability of compounds to inhibit the homologous strand exchange activity of purified human RAD51 protein, and we used these results to determine which compounds to advance into cell-based assays of HR activity. Results of these assays are displayed in Table 2, Supporting Information Figure 1, and Supporting Information Figure 2, demonstrating that chlorination of the B-ring leads to a loss of D-loop inhibition (compare 1a and 19b). Also, while replacement of the pyrroloquinoxaline core of 2h with phenanthridine has no discernible effect on RAD51 D-loop inhibition, cellular HR inhibition is greatly weakened (compare 2h and 13c). Finally, replacement of the B-ring with imidazole leads to a loss of RAD51 D-loop inhibitory activity.

Table 2.

Summary of Ring B Modifications. Measurements are reported as the indicated values ± standard error, with each data set testing at least six compound concentrations. NT = Not tested.

|

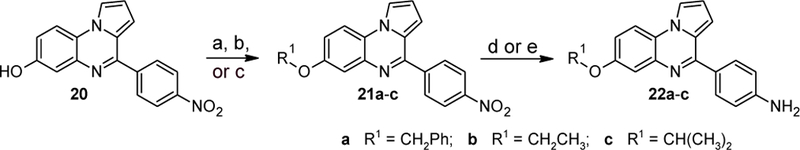

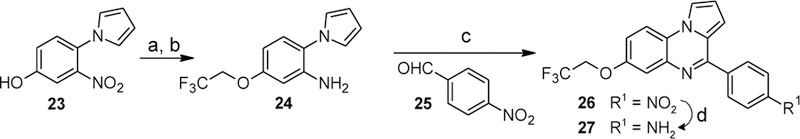

Modification of Ring A.

To explore the effects of different alkoxy groups in ring A, phenol 20[21] was alkylated with benzyl bromide, ethyl iodide, and isopropyl iodide, respectively (Scheme 9). Hydrogenation of the nitro group on ring C afforded the desired anilines 22a-c in good yield.

Scheme 9.

Synthesis of compounds 22a-c. Reagents and conditions: (a) for 21a: BnBr, NaH, DMF, rt, 89%; (b) for 21b: EtI, NaH, DMF, rt, 92%; (c) for 22c: i-PrI, NaH, DMF, rt, 84%; (d) for 22a: (d) H2 (1 bar), 5% Pt/C, MeOH, rt, 82%; (e) for compounds 23b,c: H2 (1 bar), 5% Pd/C, MeOH, rt, 64–76%.

The synthesis of the trifluoroethoxy derivative 27 on the same route failed due to the combination of low solubility of 20 and low reactivity of the alkylating agent. The successful pathway is shown in Scheme 10. Alkylation of the readily soluble phenol 23 followed by hydrogenation of the nitroarene provided the substituted aniline 24. Its reaction with 4-nitrobenzaldehyde (25) in the presence of montmorillonite KSF followed by oxidation with MnO2 yielded the nitroarene 26. Pd-catalyzed hydrogenation of the nitro group afforded the desired aniline 27.

Scheme 10.

Synthesis of compound 27. Reagents and conditions: (a) F3CCH2I, K2CO3, DMF, 100 °C, 21%; (b) H2 (1 bar), 5% Pd/C, MeOH, rt, then H2 (1 bar), 10% Pd/C, MeOH, rt, then H2 (1 bar), 20% Pd(OH)2/C, MeOH, rt, 56%; (c) montmorillonite KSF, toluene, reflux, then MnO2, CHCl3, reflux (53%); (d) H2 (1 bar), 10% Pd/C, MeOH, rt, 88%.

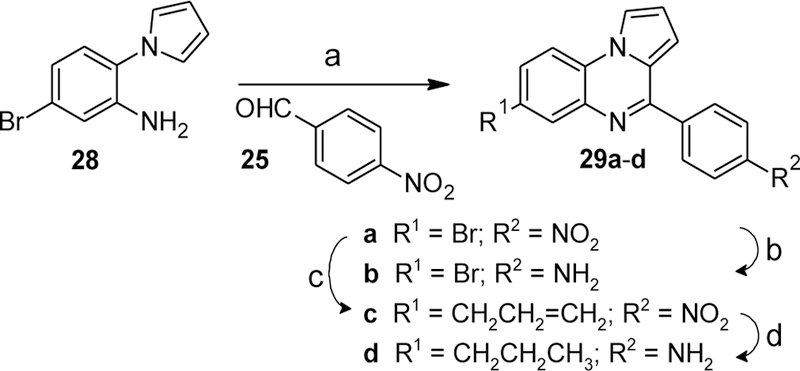

Ring A substitution was further explored by synthesizing the 6-bromo and 6-n-propyl derivatives as shown in Scheme 11. The aniline 28 reacted with 4-nitrobenzaldehyde (25) in the presence of montmorillonite KSF followed by further oxidation with MnO2 to yield the nitroarene 29a. Selective reduction of the nitro group with tin(II) chloride[37] produced the desired aniline 29b. Aryl bromide 29a was also converted to the allyl-substituted intermediate 29c via Stille coupling with allyltributyltin. Pd-catalyzed hydrogenation of both the nitro and allyl groups afforded 29d.

Scheme 11.

Synthesis of compounds 29b,d. Reagents and conditions: (a) montmorillonite KSF, toluene, reflux, then MnO2, CHCl3, reflux, 85%; (b) allyltributyltin, cat. Pd(PPh3)4, toluene, 110 °C, 54%; (c) SnCl2·H2O, PhCl/1-propanol, 100 °C, 71%; (e) H2 (1 bar), 5% Pd/C, MeOH, rt, 83%.

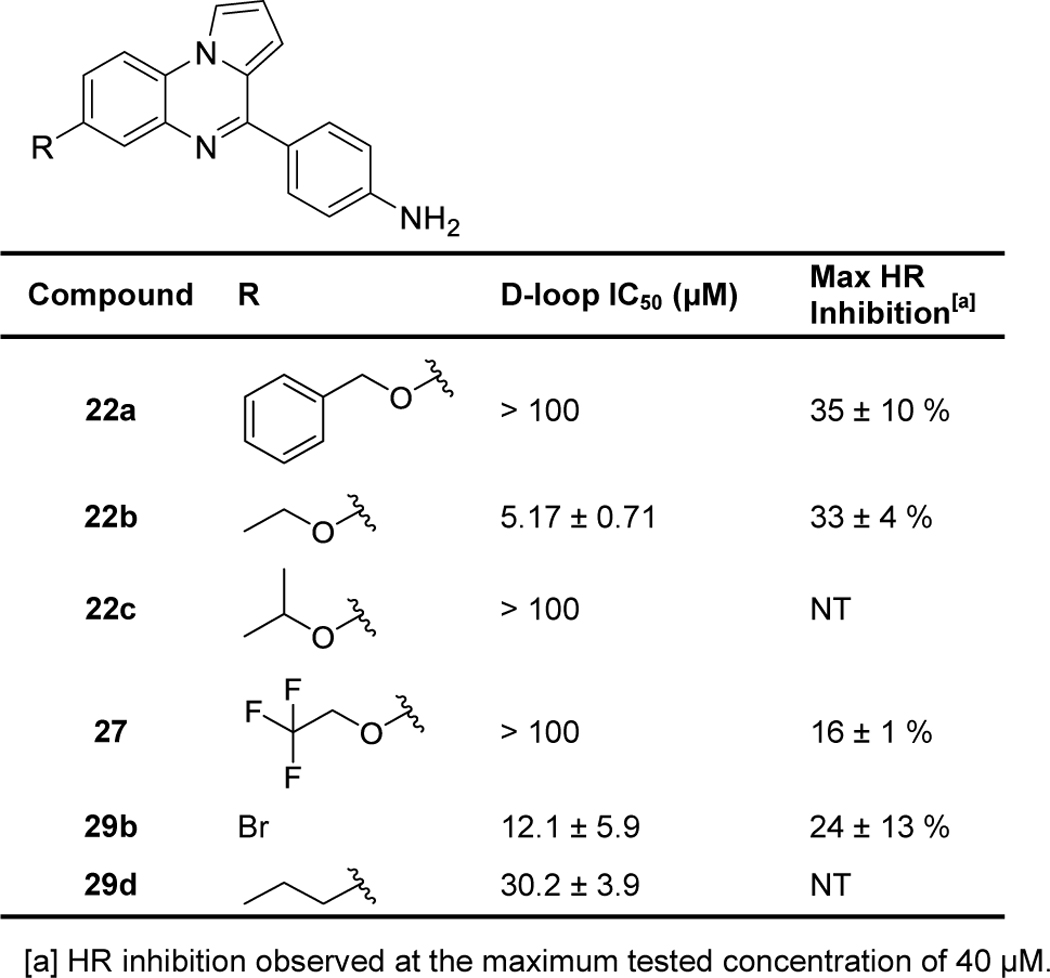

We again utilized used the biochemical D-loop assay to measure the ability of compounds to inhibit purified human RAD51 protein and to inhibit HR activity in cells. Results of these assays are displayed in Table 3, Supporting Information Figure 1, and Supporting Information Figure 2, showing that bulky, hydrophobic groups on ring A resulted in a loss of D-loop inhibitory activity (compare 1a to 22a, 22c, 27, and 29d) and that smaller groups on ring A caused little change in biochemical or cellular inhibitory activities (compare 1a to 22b, 29b).

Table 3.

Summary of Ring A Modifications. Measurements are reported as the indicated values ± standard error, with each data set testing at least six compound concentrations. NT = Not tested.

|

Identification of Off-Target DNA Intercalation Activity.

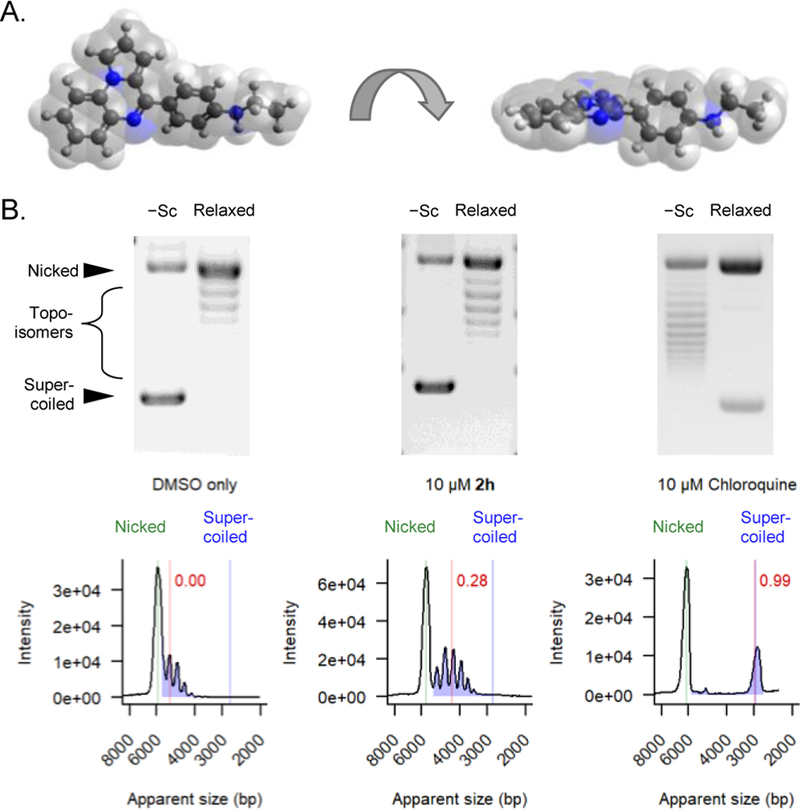

We initially prioritized compounds that inhibited RAD51’s D-loop activity at least as well as the starting compound 2h for further testing. Several of the above described analogs (2c, 8i, 8k, 10h, and 10j) appear to elicit unusually strong inhibitory activities, with IC50 values that approached the concentration of the RAD51 protein (i.e. the intended target) in the biochemical assay. Importantly, the starting chemical scaffold of this SAR campaign exhibits a relatively flat planar central ring structure (Figure 2A). Taken together, this prompted us to question whether some of these new analogs might promote off-target activity by intercalating between dsDNA base pairs and affecting DNA topology. This is an important consideration because RAD51-catalyzed D-loops are much more stable when formed in negatively supercoiled dsDNA than linear dsDNA.[38] We tested this possibility by electrophoresing relaxed covalently-closed circular dsDNA plasmids through agarose gels that were impregnated with individual compounds. In this assay, DNA intercalation activity is detected based on the accumulation of positive supercoils in the plasmid (Figure 2B). The abundance of these compound-induced topoisomers enables the quantification of that compound’s intercalation activity. DMSO vehicle control was defined as having a score of 0, and 10 μM chloroquine was defined as generating a score of 1 (i.e. saturation of the endpoint). Although this method has relatively low throughput, it provides quantitative measurements that are highly sensitive and reproducible. We also included compounds having D-loop IC50 concentrations greater than 100 μM to measure possible intercalation activity in compounds that shared the flat planar structure of 2h but showed weak or non-detectable D-loop inhibitory activity.

Figure 2.

A) Two views of the 3D structure of 2h demonstrate its planar geometry. B) Representative gel images are displayed for circular plasmids (mixture of negatively supercoiled [−Sc] and relaxed covalently closed), which were electrophoresed through agarose gels containing 4% DMSO alone, 10 μM 2h, or 10 μM chloroquine. Densitometry traces are displayed below each gel. The positions of resulting topoisomers are denoted with blue color, and the positions of nicked plasmids are shown in green. The degree of DNA intercalation is denoted by the red line, indicating the median distance of topoisomer migration relative to the DMSO control.

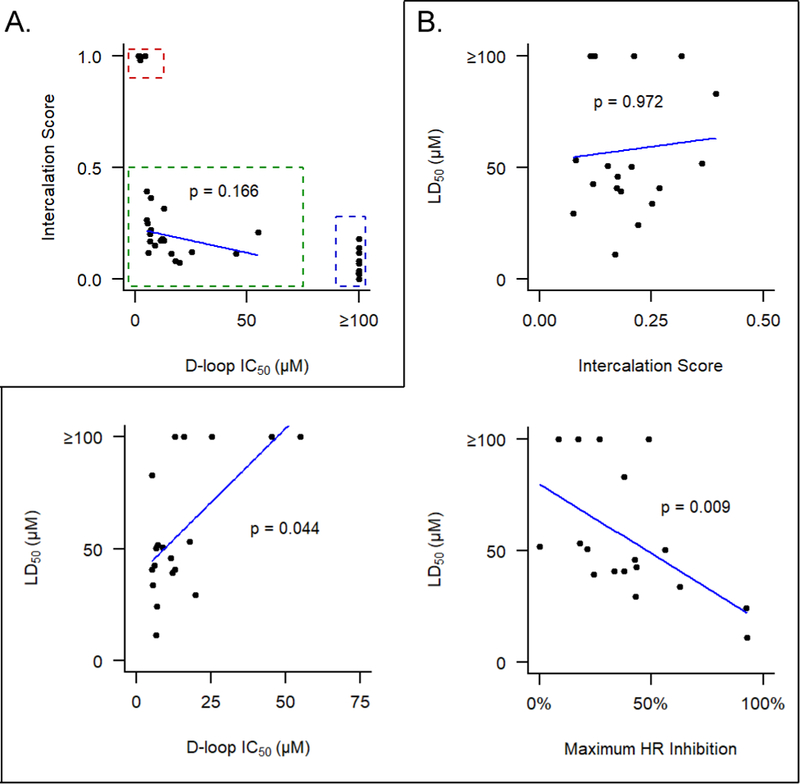

Several of the compounds (2c, 8i, 8k, 10h, and 10j) were found to exhibit significant off-target dsDNA intercalation (Figure 3A, red box). As predicted, these compounds also generate high levels of inhibition of the D-loop assay, with IC50 values that approached the concentration of the RAD51 target. Furthermore, these compounds also highly toxic to cells, with LD50 values in the 5 – 33 μM range. A second subgroup of sub-optimal compounds (Figure 3A, blue box) exhibited low intercalation into dsDNA but a poor ability to inhibit RAD51 in the D-loop assay; these compounds were similarly deemed as not suitable for further development.

Figure 3.

A) Sub-optimal analogs exhibit either off-target dsDNA intercalation (red box) or poor ability to inhibit RAD51 in the D-loop assay (blue box). For the remaining 19 compounds (green box), no significant relationship is observed between intercalation score and ability to inhibit D-loop formation (Pearson product-moment correlation). B) Inhibition of RAD51’s D-loop activity and cellular HR activity, but not intercalation activity, correlate with toxicity in 293-HEK cells (Significance determined by Kendall’s tau correlation).

Among remaining 19 compounds (Figure 3A, green box), we found no significant correlation between intercalation score and their ability to inhibit D-loop formation (p=0.17, Pearson product-moment correlation). Furthermore, no significant correlation exists between intercalation score and compound toxicity (Figure 3B). By contrast, compound-induced cellular toxicity does significantly correlate with compounds’ ability to inhibit D-loop formation and to reduce HR proficiency in cells. Taken together, these results support the conclusion that cell-based toxicity for this optimized collection of compounds represents an on-target effect.

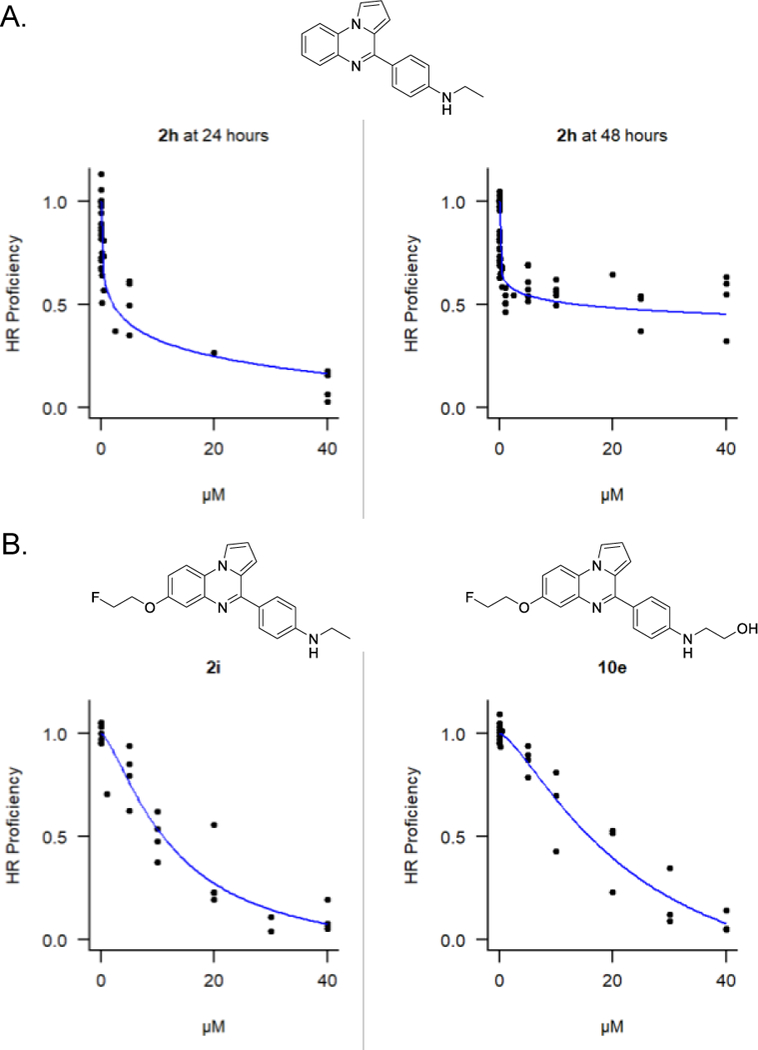

Optimized Analogs Offer Improved Ability to Inhibit HR in Cells.

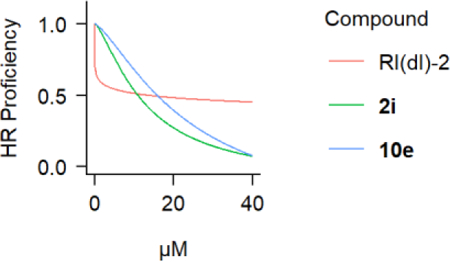

We used the DR-GFP assay to test the ability of select compounds to inhibit HR in human cells.[35] Briefly, cells containing the chromosomally-integrated DR-GFP reporter were transfected with a plasmid that expresses I-SceI, a rare-cutting endonuclease that generates a DSB within the DR-GFP cassette. Compounds were added at the time of transfection, and the cells were outgrown for 48 hours thereafter. Cells capable of successfully performing HR-mediated DSB repair are quantified based on their expression of functional green fluorescent protein (GFP).

As previously reported, the lead compound 2h effectively inhibits HR in the first 24 hours of the DR-GFP assay.[21] However, 2h-treated cells regain some HR activity in the second 24 hours (Figure 4A), which is highly relevant since the majority of I-SceI-dependent conversion events occur within the second 24 hours of the assay. Among the subset of the 19 best compounds, 2i and 10e demonstrated a superior ability to inhibit HR events in the second 24 hours of the assay (Figure 4B). Both compounds exert a nearly linear dose-dependent inhibition of HR, approaching complete inhibition at with concentrations in the 30–40 μM range. Finally, both 2i and 10e showed cellular LD50 values (11.3 ± 0.7 μM for 2i and 24.3 ± 1.3 μM for 10e) that were proportional to their HR inhibition IC50 values at 48 hours following DSB induction (10.9 ± 5.6 μM for 2i and 15.8 ± 8.5 μM for 10e).

Figure 4.

A) Inhibition of HR activity in 293-HEK cells by 2h at 24 hours or 48 hours following DSB induction. B) Inhibition of HR activity by 2i and 10e at 48 hours following DSB induction. Individual data points from at least four independent experiments are plotted along with fitted four-parameter log-logistic curves.

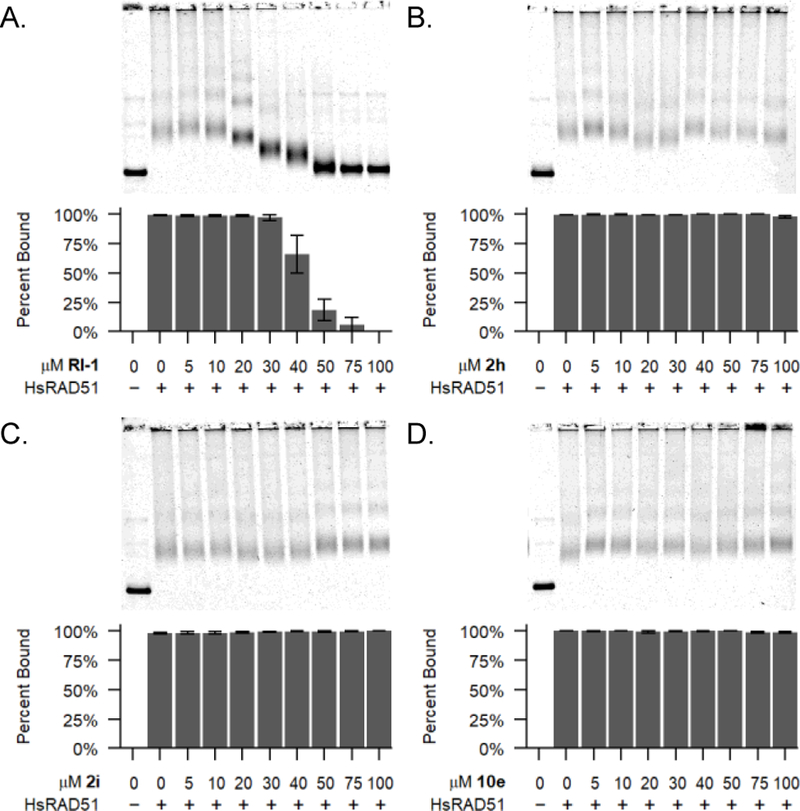

A defining feature of this class of compounds is their ability to inhibit RAD51’s D-loop activity while having minimal effects on RAD51’s ssDNA binding activity.[21] Therefore, additional experiments were performed to confirm that the optimized analogs 2i and 10e had not gained the ability to interfere with RAD51’s binding to ssDNA. Using gel shift assays, we confirmed that neither of these compounds affected the formation or stability of RAD51-ssDNA nucleoprotein filaments on ssDNA (Figure 5). By comparison, the more generalized RAD51 inhibitor RI-1 (which prevents binding of RAD51 to ssDNA) eliminates the formation of RAD51-ssDNA nucleoprotein filaments.[17] Taken together, these results confirm that optimized drug candidates 2i and 10e act to specifically to prevent the D-loop formation activity of RAD51.

Figure 5.

RAD51 binding to ssDNA binding is inhibited by RI-1, but not by optimized compounds 2i or 10e. Representative agarose gels are shown with data plotted from three independent experiments. Error bars denote the standard error of the mean.

Conclusions

The over-expression of the RAD51 recombinase protein represents a common hallmark of malignancy, and tumor cells are especially dependent upon the HR function of RAD51. Taken together, RAD51 is a highly attractive therapeutic target in oncology.[15–16, 18, 39] In addition to its classical role in catalyzing homologous strand exchange, RAD51 additionally plays a central role in protecting stalled replication forks from nucleolytic degradation.[3–4] This protective function in replication requires that RAD51 is able to bind ssDNA, however it may not require the strand invasion activity of RAD51. Therefore, our drug development strategy aims to inhibit RAD51’s D-loop activity while sparing its ssDNA binding activity.

The role of RAD51 and other HR proteins in replication fork remodeling during replication stress has been an intense topic of research in recent years. Further work is underway to mechanistically dissect the effect of our inhibitory compounds on RAD51 at the level of the replication fork. However, such effects may be challenging to investigate using typical nascent DNA resection assays. This is because MRE11-dependent nucleolytic degradation of the nascent DNA at stalled forks requires preceding replication fork reversal, and this reversal process requires RAD51 protein.[40–41] Therefore, compounds that permit RAD51-ssDNA binding are expected to permit fork reversal and to stabilize forks from MRE11-dependent nuclease degradation. Such an effect would be difficult to distinguish from that caused by total loss of RAD51 activity, in which fork reversal never occurs.

Our initial efforts had identified lead compound 2h, which satisfied our broad goals.[21] However, 2h proved to be relatively ineffective at blocking cellular HR events at time points later than 24 hours. This feature of 2h limits its potential utility in clinical settings, given that many common oncologic therapies exert their oncologic effects over prolonged time intervals. An additional challenge that arose during this SAR campaign was the introduction of off-target toxicity, in which some analogs had ability to intercalate into dsDNA. Having now overcome these limitations with the optimized compounds 2i and 10e, our future work will be focused on additional synthetic schemes to improve upon potency.

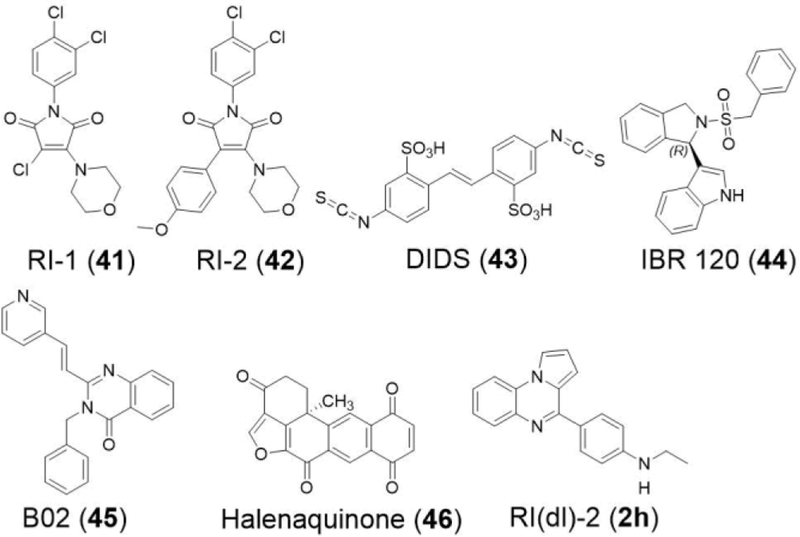

There is a growing interest in RAD51 as a potential target in cancer therapy. Figure 6 shows some of the RAD51-inhibitory compounds in development by our group and others. The first RAD51 inhibitors developed by our group, RI-1 (41) and RI-2 (42), represent a class of compounds that block RAD51-ssDNA nucleoprotein filament formation and subsequent strand exchange.[14, 17] Other compounds in this class include DIDS (43), IBR 120 (44), B02 (45), and a recently-developed analog of 45 with greater single-agent potency against tumor cell lines.[18, 20, 42–43] Halenaquinone (46), 2h, 2i, and 10e belong to a second class of compounds purported to target strand exchange while permitting the binding of RAD51 to ssDNA.[21, 44]

Figure 6.

Chemical structures for several RAD51 inhibitors.

These findings represent a major advance in the development of RAD51-targeting small molecules. To our current knowledge, our series of compounds remain the only known chemicals capable of inhibiting RAD51’s D-loop activity without interfering with its ability to bind ssDNA, both in biochemical systems and in cells. Further work is necessary to determine which clinical scenarios will be best suited for this therapeutic approach. Specifically, we are working to define the optimal classes of DNA-damaging therapies that will offer maximal synergy in combination with these novel compounds. Furthermore, we are exploring the utility of these agents as single-agent treatments in a specific susceptible tumor subtype. Finally, these compounds present a novel set of tools for basic scientists who wish to study the distinct functions of RAD51.

Experimental Section

Cells, Media, and Proteins.

The 293-HEK cell line containing the chromosomal DR-GFP reporter cassette along with the I-SceI expressing pCBASce and pCAGGS empty vector control plasmids were kindly provided by Jeremy Stark and have been described previously.[35] All cell lines were maintained in complete DMEM (DMEM + 4.5 g/L D-glucose + L-glutamine + 10% fetal calf serum + penicillin/streptomycin) and verified to be free of mycoplasma by monthly testing. Human RAD51 protein was purified as described previously.[45]

D-Loop Assay.

Human RAD51 protein in reaction buffer was combined with compound in DMSO in a total volume of 8 µL, incubated at 37 ºC for 10 minutes. Then 1 µL of 5′−32P-labeled or 5’-Cy5-labeled 90-mer ssDNA (5′-TACGAATGCACACGGTGTGGTGGGCCCAGGTATTGTTAGCGGT-TTGAAGCAGGCGGCAGAAGAAGTAACAAAGGAACCTAGAGGCCTT-TT) with homology to the plasmid pRS306 was added, and the reaction was incubated at 37 ºC for an additional 5 minutes. Then 1 µL of supercoiled pRS306 dsDNA plasmid was added, and the reaction was incubated at 37 ºC for 20 minutes. At this point, reactions containing human RAD51 protein consisted of 25 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.0), 1 mM ATP, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 100 µg/mL BSA, 4.5% DMSO, 0.5 µM RAD51, 11 mM NaCl, 1% glycerol, 20 nM ssDNA, and 5 nM pRS306 dsDNA. Reactions using the 5′−32P-labeled ssDNA contained 10 nM ssDNA oligonucleotides and those using the 5’-Cy5-labeled ssDNA contained 20 nM ssDNA oligonucleotides; there was no difference in the ability of compounds to inhibit D-loops between these conditions (data not shown). The reactions were de-proteinized with 0.8% SDS and 0.8 mg/mL proteinase K, mixed with gel loading buffer, and run on a 0.9% agarose / 1X TAE gel. The gel was dried under vacuum on a positively-charged nylon membrane for 2 hours at 80 °C, exposed to a phosphor screen overnight, and imaged on a Storm 860 or Typhoon 9200 scanner (Molecular Dynamics). Quantitation of free oligo and D-loop bands was performed using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

Quantitation of DNA Repair Efficiency in Cells.

293-DR-GFP cells were electroporated in Opti-MEM with 37.5 µg/mL of the I-SceI endonuclease bearing pCBASce plasmid or the pCAGGS empty vector control in 0.4 cm cuvettes at 325 V, 975 µF and seeded into 6-well plates with 2.5 mL complete DMEM + 0.5% DMSO with compound and allowed to outgrow for the indicated time. Following outgrowth, cells were harvested, suspended in PBS with 1 µg/mL 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD), and analyzed on a BD LSRII flow cytometer. Dead and apoptotic cells were gated out based on size, shape, and 7-AAD staining. The fraction of GFP-positive cells was determined within the population of live cells.

Intercalation Assay.

Negatively supercoiled pRS306 plasmid DNA was prepared by standard CsCl gradient purification. Relaxed covalently-closed circular (rCCC) plasmid DNA was prepared from negatively supercoiled plasmid DNA by treating with 1.33 units E. coli topoisomerase I (New England Biolabs) per microgram plasmid DNA at 37 °C for 30 minutes followed by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. One-hundred and fifty nanograms of negatively supercoiled or rCCC plasmid were loaded along with linear DNA size markers in immediately adjacent lanes into a 0.9% agarose 1X TAE gel, with 4% DMSO ± 10 μM compound present throughout the gel and the running buffer. The gel was run at 5 V/cm until the xylene cyanol FF dye had migrated 5 cm from the well, stained with ethidium bromide, and photographed under UV transillumination. Densitometry traces were obtained for each lane using ImageJ, and intercalation scores were calculated from the lane loaded with rCCC plasmid as the median distance migrated by topoisomers for each compound relative to the DMSO-only control from the same experiment.

Quantitation of Cellular Toxicity by Compounds.

293-HEK cells were seeded into white clear-bottom 96-well plates at a density of 1.1 × 105 cells/cm2 in 0.2 mL per well complete DMEM with 0.5% DMSO with compound and incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 48 hours. Following incubation, cell viability was measured using CellTiter-Glo reagent (Promega) and reading luminescence values on a Tecan infinite F200 Pro plate reader.

RAD51-DNA binding assay.

Human RAD51 protein in reaction buffer was combined with compound at the indicated concentration in DMSO in a total volume of 9 μL, incubated at 37 °C for 40 minutes, then 1 μL of 4,373-nt closed circular pRS306 virion ssDNA substrate was added, and the reaction was incubated at 37 °C for an additional 5 minutes. At this point, the reaction consisted of 25 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.2), 3 mM ATP, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, 100 μg/mL BSA, 0.5 μM RAD51, 1.5 μM nucleotide concentration ssDNA, and 4.5% DMSO. RAD51-ssDNA complexes were then fixed by addition of 2 μL glutaraldehyde in water to 0.25%, incubated for 5 minutes at 37 °C, and run on a 1% agarose / 1X TAE gel, which was stained in SYBR Gold (Molecular Probes) and imaged using a Typhoon 9200 scanner (Molecular Dynamics).

Statistical Analysis.

All statistical analyses and graphing were performed using R.[46] LD50, IC50, and maximum inhibition values and their standard errors were determined by fitting four-parameter log-logistic curves to the data by least-squares nonlinear regression followed by inverse estimation using the ‘drc’ package.[47] Baseline correction for densitometry plots was performed using the ‘baseline’ package.[48]

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH grant 2R01CA142642 to P.P.C. and A.P.K. The Bruker Avance III 400 NMR spectrometer was supported by NSF grant CHE-1048642, and the Bruker Avance III 500 NMR spectrometer by a generous gift from Paul J. and Margaret M. Bender (both to the University of Wisconsin at Madison Department of Chemistry). The purchase of the Thermo Scientific Q Exactive Plus Orbitrap mass spectrometer was funded by NIH Award 1S10 OD020022-1 to the University of Wisconsin at Madison Department of Chemistry.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

Supporting Information. Synthetic procedures for compounds 1a – 40 can be found in the Supporting Information on the journal’s website.

References:

- [1].Tebbs RS, Zhao Y, Tucker JD, Scheerer JB, Siciliano MJ, Hwang M, Liu N, Legerski RJ, Thompson LH, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92(14), 6354–6358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Thompson LH, Schild D, Mutat. Res 2001, 477(1–2), 131–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Schlacher K, Christ N, Siaud N, Egashira A, Wu H, Jasin M, Cell 2011, 145(4), 529–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ying S, Hamdy FC, Helleday T, Cancer Res 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [5].Zellweger R, Dalcher D, Mutreja K, Berti M, Schmid JA, Herrador R, Vindigni A, Lopes M, J. Cell Biol 2015, 208(5), 563–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ding X, Ray Chaudhuri A, Callen E, Pang Y, Biswas K, Klarmann KD, Martin BK, Burkett S, Cleveland L, Stauffer S, Sullivan T, Dewan A, Marks H, Tubbs AT, Wong N, Buehler E, Akagi K, Martin SE, Keller JR, Nussenzweig A, Sharan SK, Nat. Commun 2016, 7, 12425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Feng W, Jasin M, Nat. Commun 2017, 8(1), 525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hine CM, Seluanov A, Gorbunova V, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105(52), 20810–20815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Klein HL, DNA Repair (Amst) 2008, 7(5), 686–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bello VE, Aloyz RS, Christodoulopoulos G, Panasci LC, Biochem. Pharmacol 2002, 63(9), 1585–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hansen LT, Lundin C, Spang-Thomsen M, Petersen LN, Helleday T, Int. J. Cancer 2003, 105(4), 472–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Slupianek A, Schmutte C, Tombline G, Nieborowska-Skorska M, Hoser G, Nowicki MO, Pierce AJ, Fishel R, Skorski T, Mol. Cell 2001, 8(4), 795–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Vispe S, Cazaux C, Lesca C, Defais M, Nucleic Acids Res 1998, 26(12), 2859–2864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Budke B, Kalin JH, Pawlowski M, Zelivianskaia AS, Wu M, Kozikowski AP, Connell PP, J. Med. Chem 2013, 56(1), 254–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ito M, Yamamoto S, Nimura K, Hiraoka K, Tamai K, Kaneda Y, J. Gene Med 2005, 7(8), 1044–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Russell JS, Brady K, Burgan WE, Cerra MA, Oswald KA, Camphausen K, Tofilon PJ, Cancer Res 2003, 63(21), 7377–7383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Budke B, Logan HL, Kalin JH, Zelivianskaia AS, Cameron McGuire W, Miller LL, Stark JM, Kozikowski AP, Bishop DK, Connell PP, Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40(15), 7347–7357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Huang F, Mazin AV, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2014, 24(14), 3006–3013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Huang F, Mazina OM, Zentner IJ, Cocklin S, Mazin AV, J. Med. Chem 2012, 55(7), 3011–3020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ishida T, Takizawa Y, Kainuma T, Inoue J, Mikawa T, Shibata T, Suzuki H, Tashiro S, Kurumizaka H, Nucleic Acids Res 2009, 37(10), 3367–3376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lv W, Budke B, Pawlowski M, Connell PP, Kozikowski AP, J. Med. Chem 2016, 59(10), 4511–4525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Tsunoda T, Yamamiya Y, Itô S, Tetrahedron Lett 1993, 34(10), 1639–1642. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Carpino LA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1993, 115(10), 4397–4398. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Abdel-Magid AF, Carson KG, Harris BD, Maryanoff CA, Shah RD, J. Org. Chem 1996, 61(11), 3849–3862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cran JW, Vidhani DV, Krafft ME, Synlett 2014, 25(11), 1550–1554. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Miyaura N, Yanagi T, Suzuki A, Synth. Commun 1981, 11(7), 513–519. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kudo N, Perseghini M, Fu GC, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2006, 45(8), 1282–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Littke AF, Dai C, Fu GC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122(17), 4020–4028. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kumar Y, Florvall L, Synth. Commun 1983, 13(6), 489–493. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Cao C, Lu Z, Cai Z, Pang G, Shi Y, Synth. Commun 2012, 42(2), 279–284. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zhang H, Cai Q, Ma D, J. Org. Chem 2005, 70(13), 5164–5173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Guari Y, van Es DS, Reek JNH, Kamer PCJ, van Leeuwen PWNM, Tetrahedron Lett 1999, 40(19), 3789–3790. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Schareina T, Zapf A, Mägerlein W, Müller N, Beller M, Chem. Eur. J 2007, 13(21), 6249–6254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wu L, Hartwig JF, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127(45), 15824–15832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Bennardo N, Cheng A, Huang N, Stark JM, PLoS Genet 2008, 4(6), e1000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Guillon J, Grellier P, Labaied M, Sonnet P, Léger J-M, Déprez-Poulain R, Forfar-Bares I, Dallemagne P, Lemaître N, Péhourcq F, Rochette J, Sergheraert C, Jarry C, J. Med. Chem 2004, 47(8), 1997–2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Bellamy FD, Ou K, Tetrahedron Lett 1984, 25(8), 839–842. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wright WD, Heyer WD, Mol. Cell 2014, 53(3), 420–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Raderschall E, Stout K, Freier S, Suckow V, Schweiger S, Haaf T, Cancer Res 2002, 62(1), 219–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Mijic S, Zellweger R, Chappidi N, Berti M, Jacobs K, Mutreja K, Ursich S, Ray Chaudhuri A, Nussenzweig A, Janscak P, Lopes M, Nat. Commun 2017, 8(1), 859–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Schlacher K, Wu H, Jasin M, Cancer Cell 2012, 22(1), 106–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Zhu J, Chen H, Guo XE, Qiu X-L, Hu C-M, Chamberlin AR, Lee W-H, Eur. J. Med. Chem 2015, 96, 196–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ward A, Dong L, Harris JM, Khanna KK, Al-Ejeh F, Fairlie DP, Wiegmans AP, Liu L, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2017, 27(14), 3096–3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Takaku M, Kainuma T, Ishida-Takaku T, Ishigami S, Suzuki H, Tashiro S, van Soest RWM, Nakao Y, Kurumizaka H, Genes Cells 2011, 16(4), 427–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Jayathilaka K, Sheridan SD, Bold TD, Bochenska K, Logan HL, Weichselbaum RR, Bishop DK, Connell PP, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105(41), 15848–15853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].R_Core_Team, R: A language and environment for statistical computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ritz C, Baty F, Streibig JC, Gerhard D, PLoS One 2015, 10(12), e0146021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Liland KH, Mevik H, Canteri R, Baseline Correction of Spectra, 2015.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.