Summary

Women have smaller cortisol responses to psychological stress than men do, and women taking hormonal contraceptives (HC+) have smaller responses than HC– women. Cortisol secretion undergoes substantial diurnal variation, with elevated levels in the morning and lower levels in the afternoon, and these variations are accompanied by differences in response to acute stress. However, the impact of HC use on these diurnal relationships has not been examined. We tested saliva cortisol values in 744 healthy young adults, 351 men and 393 women, 254 HC– and 139 HC+, who were assigned to morning (9:00 am) or afternoon (1:00 pm) test sessions that were held both on a rest day and a stress day that included public speaking and mental arithmetic challenges. Saliva cortisol responses to stress were largest in men and progressively smaller in HC– and in HC+ women (F = 23.26, p < .0001). In the morning test sessions, HC+ women had significantly elevated rest day cortisol levels (t = 5.99, p << .0001, Cohen’s d = 0.95) along with a complete absence of response on the stress day. In the afternoon sessions, both HC+ and HC– women had normal rest-day cortisol levels and normal responses to the stressors. Heart rates at rest and during stress did not vary by time of day or HC status. Cortisol stress responses in HC+ women are absent in the morning and normal in size by early afternoon. Studies of stress reactivity should account for time of day in evaluating cortisol responses in women using hormonal contraceptives.

Keywords: hormonal contraceptives, women, cortisol, heart rate, stress reactivity

Cortisol reactivity to laboratory stress manipulations has a significant place in the literature on stress and health. Practical considerations for the design and interpretation of studies of cortisol reactivity may involve comparing men and women and addressing the impact of the time of day on stress reactivity. Hormonal contraceptive (HC) use elevates saliva free cortisol levels in the morning hours (Carr, Parker, Madden, MacDonald, & Porter, 1979; Kuhl, Jung-Hoffmann, Weber, & Boehm, 1993), with values being double those in unmedicated women. Cortisol responses to stress are reliably found to be smaller in women than in men (Kirschbaum, Wust, & Hellhammer, 1992), and smaller still in women taking hormonal contraceptives (HC+) relative to untreated women (HC–) (Kirschbaum, Kudielka, Gaab, Schommer, & Hellhammer, 1999; Roche, King, Cohoon, & Lovallo, 2013). However, the effect of time of day on the magnitude of stress responses in HC+ and HC– women is not established.

Cortisol secretion varies significantly across the waking hours, peaking shortly after awakening and diminishing steadily into the early morning (Weitzman et al., 1971). This pronounced diurnal cycle may affect cortisol stress responses in the lab depending on the time of day the testing occurs. Informal recommendations for designing studies of cortisol stress reactivity frequently advocate measuring cortisol in the afternoon, on the premise that large responses should occur more readily against low afternoon baselines compared to high morning baselines. In an earlier paper (Lovallo, Farag, & Vincent, 2010) we reported that, despite a higher baseline, the response to stress is larger in the morning and smaller in the afternoon for both men and women, in keeping with a prior systematic review (Dickerson and Kemeny, 2004). The impact of time of day in relation to HC status was not addressed.

In the present analysis, we asked whether cortisol responses to mental stress were diminished in groups of HC+ women tested in the morning (9:00) and in the early afternoon (1:00) relative to HC– controls and to men. For interpretation of the cortisol data, we compared the study groups on heart rate reactivity and subjective responses to the stressors.

Methods

Overview.

This is a secondary analysis of data from the Oklahoma Family Health Patterns Project, a study of risk factors for alcoholism (Lovallo et al., 2013). The large sample participating in the study provides useful information individual and situational factors affecting stress reactivity. Subjects visited the laboratory for an initial screening session that included interview and paper and pencil evaluations for inclusion criteria and sociodemographic characteristics. Those meeting inclusion criteria were then scheduled for two more visits held at the same time each day.

Subjects.

The present analysis includes 393 women and 351 men who completed the stress protocol. Subjects were recruited through community advertisement and received financial compensation for participating. Each signed an informed consent form approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB no. 2302) of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center and the VA Medical Center, Oklahoma City, OK.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Participants were 18–30 years of age, in good physical health, had a body mass index < 30, and had no reported history of serious medical disorder. Hormonal contraceptive use was determined based on a health and medication questionnaire completed during intake screening and updated on each lab visit. The questionnaire did not distinguish between oral contraceptives or implants. Prospective volunteers were excluded if they: were taking prescription medications other than hormonal birth control; had a history of alcohol or drug dependence; met criteria for current substance abuse within the past 2 mo; failed a urine drug screen or breath-alcohol test on days of testing; or had a history of any Axis I disorder other than past depression (> 60 days previous), as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders, 4th ed. (Association, 1994). Smoking and smokeless tobacco use were not exclusionary.

Procedure.

Following the screening visit, subjects visited the lab twice more for behavioral and stress testing. These two additional sessions were held at the same time on both days, either in the morning at 9:00 am (N = 349) or in the afternoon 1:00 pm (N = 360). Each subject was required to provide a negative urine pregnancy test upon arriving at the lab on each day of testing. No attempt was made to account for phase of menstrual cycle in relation to days of testing.

To maximize stress responses, the first lab day involved the stress procedure and the second day was designated the resting control day. Subjects were briefed in advance of this test order and were told to expect to deliver short speeches and a mental arithmetic task on the stress day. Placing stress exposure on day 1 compares to testing on a single study day, as done in most stress research (Lovallo, Farag, et al., 2010).

Stress protocol.

The protocol was designed to call forth significant cognitive effort to perform well in the presence of an experimenter engaging in social evaluation and providing corrections for errors, both of which threatened embarrassment for lapses in performance (al’Absi et al., 1997). The protocol (105 min) included a prestress baseline (30 min), during which the subject sat quietly and read general interest magazines, followed by mental stress (45 min) consisting of simulated public speaking (30 min) (Saab, Matthews, Stoney, & McDonald, 1989) and mental arithmetic (15 min) (al’Absi, et al., 1997), and finishing in a recovery period (30 min). A white coated experimenter monitored performance taking notes on a clipboard and corrected errors during mental arithmetic.

Resting control day.

The protocol lasted 105 minutes, during which the subject sat and read general interest magazines or watched videotapes of nature programs lacking emotional content.

Subjective reports.

Subjects rated their moods at each saliva sample using 12 10-point visual-analogue scales adapted from Foresman (Lundberg., 1980) containing a Distress subscale (impatience, irritability, distress, pleasantness, and feelings of control) and an Activation subscale (effort, tension, concentration, interest, and stimulation) (al’Absi, et al., 1997).

Mood and temperament assessment.

As part of the screening process, all subjects completed self-report instruments including the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck and Beamesderfer, 1974), the Eysenck Personality Inventory Neuroticism scale EPI-N (Eysenck and Eysenck, 1964), and the Socialization Scale of the California Personality Inventory (CPI-So) (Gough, 1994). We interpret the BDI and EPI-N to be useful measures of affective stability (Meites, Lovallo, & Pishkin, 1980) and the CPI-So to represent a sense of social connectedness, behavioral regulation, and empathy (Gough, 1994).

Saliva collection times and cortisol assay

Because cortisol secretion is dependent on the sleep-wake cycle (Czeisler and Klerman, 1999), volunteers were required to have a normal work or school schedule and a nighttime sleep pattern. Since cortisol levels are affected by blood glucose values (Dallman et al., 2003), all volunteers ate a standard meal at the lab before beginning the protocol. Saliva samples were collected using the Salivette device (Sarstedt, Newton, NC, USA) and were taken at 9 periods across both days: awakening, arrival at the lab, min 10 and 20 of the baseline period, min 15, 30, and 45 of the stress protocol or continued rest, and at 30 min post stress or continued rest, and again at bedtime. Salivettes were centrifuged at 4200 RPM for 20 min, and the saliva was transferred to cryogenic storage tubes and stored at – 20° C until quantification. Saliva free cortisol assays were conducted by Salimetrics (State College, PA, USA) using a competitive enzymatic immunoassay with a sensitivity of < .083 μg/dL and an interassay coefficient of variation of < 6.42%. Cortisol data were log values to normalize the distribution.

Heart rate

Heart rate was measured continuously during both protocol days from readings made every 2 min using an oscillometric monitor (Dinamap, V100, General Electric, USA).

Data analysis

Dependent variables were the cortisol and heart rate responses to stress along with self-reports. Cortisol reactivity was measured as the difference in the mean of the cortisol values over minutes 30 and 45 of the stress period minus the mean of the cortisol values over the same two time periods during the extended rest protocol. Heart rate reactivity was measured as the mean heart rate during speech preparation periods minus the heart rate at those times during the rest day protocol to avoid confounding by vocal activity during the speech delivery or mental arithmetic.

The present analysis used a general linear model including HC group, Time of day of testing, and the HC x Time interaction, followed by Tukey-Kramer post hoc tests. Type III sums of squares were evaluated to ensure independence of significant effects. Data were analyzed using SAS software, Ver. 9.4 for Windows. Copyright© 2012 SAS Institute Inc. SAS and all other SAS Institute Inc. product or service names are registered trademarks of SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA.

Results

Characteristics of the study sample are shown in Table 1. Relative to HC– women, HC+ were more likely to be white, higher in SES, and to be less likely to smoke.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Male | HC- Female | HC+ Female | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 315 | 254 | 139 | |

| AM sessions (%) | 49 | 49 | 50 | 0.94 |

| Age | 23.8 [0.2] | 23.6 [0.2] | 23.6 [0.3] | 0.94 |

| Race (% White) | 85 | 71 | 85 | 0.01 |

| SES | 49 [0.7] | 44 [0.8] | 47 [1.0] | 0.02 |

| Education (yr) | 15.7 [0.2] | 15.5 [0.1] | 15.9 [0.2] | 0.09 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.5 [0.2] | 23.0 [0.2] | 22.7 [0.3] | 0.34 |

| Smokers (%) (n) | 9.52 (30) | 8.66 (22) | 3.60 (5) | 0.06 |

Note: SES = Socioeconomic status using Hollingshead and Redlich’s system based on the highest job category held by the head of the subject’s childhood household (Hollingshead, 1975). p-values compare the HC groups and are based on Student’s t test or X2

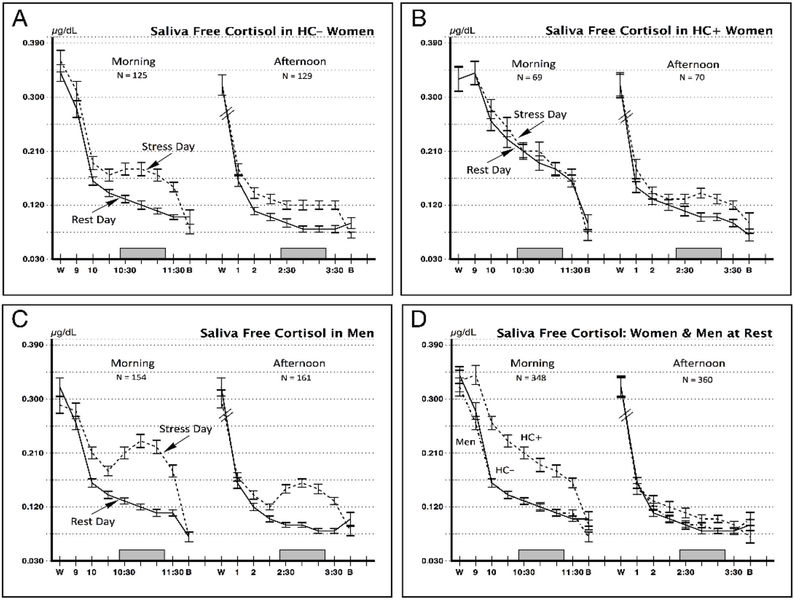

Table 2 compares the men and HC+ and HC– women on stress cortisol reactivity collapsed across morning and afternoon test sessions. Men had the largest responses overall, and the HC– and HC+ women had progressively smaller response scores (F = 23.26, p < .0001). Tukey-Kramer adjusted comparisons showed that each group differed from the other two. However, this overall difference in stress reactivity between HC+ and HC– women is qualified by the time of day they were tested. Cortisol levels across the waking hours on the stress and rest days are displayed in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Cortisol reactivity delta scores for the three study groups

| Mean | SEM | N | |

| Males | 0.546 | 0.03 | 315 |

| HC− Women | 0.355 | 0.04 | 254 |

| HC+ Women | 0.175 | 0.04 | 139 |

| F = 23.26, p < 0.0001 | |||

| Paired contrasts using Tukey-Kramer adjusted p-values | |||

| HC− | HC+ | ||

| Men | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | |

| HC+ | 0.0001 | ||

Note: Reactivity scores denote the difference in cortisol levels collected during the stress protocol minus those collected at the corresponding times during the resting control day. HC = hormonal contraceptive

Figure 1.

Log transformed saliva free cortisol values on resting control days and stress days. Data are shown for subjects tested in morning sessions starting at 9:00 am and in afternoon sessions at 1:00 pm. W = saliva sample taken upon awakening in the morning. B = saliva sample taken at bedtime. Clock times are shown to indicate times each protocol was conducted. Shaded rectangle corresponds to the time of the stress period on the stress day. Entries show Mean ± SEM.

Rest day cortisol values.

Figure 1, Panel D shows the diurnal secretion pattern across the rest day for morning and afternoon test groups. Cortisol values reflected the expected diurnal pattern, with all three study groups having nearly identical values in saliva samples taken at awakening and bedtime and levels that decline across the waking hours. The rest day awakening values were nearly identical for the three study groups (Means ± SEM for Males = 0.32 ±. 01, HC– Females = 0.33 ± .011, and HC+ Females = 0.33 ± 0.14; F = 0.13, p = 0.88). However, the HC+ women stood out from this pattern during the hours from 9:00 to 11:30, during which they showing substantially elevated levels of cortisol relative to the HC– women, t = 5.99, p << .0001, Cohen’s d = 0.95, an elevation they also showed on the stress day. In addition, the HC+ women were the only group to show a rise in cortisol at the 9:00 am sampling time relative to their awakening value at home, also shown on both days (Panel B).

Stress reactivity in the morning and afternoon sessions.

The HC– women and the men had cortisol reactivity values that were higher in the morning and lower in the afternoon (Panels A and C). This pattern was reversed in the HC+ women, who had a complete absence of stress response in the morning (Panel B) and a normal level of response in the afternoon, as referenced to the HC– women. Paired comparisons are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

General Linear Model of cortisol reactivity scores in women tested in the morning and afternoon

| F-value | p-value | partial eta2 | |

| HC Group | 10.31 | 0.0014 | 0.026 |

| Time of day | 5.90 | 0.0156 | 0.015 |

| Interaction | 5.65 | 0.0180 | 0.014 |

| Tukey-Kramer adjusted p-values for paired comparisons | |||

| HC− AM | HC− PM | HC+ PM | |

| HC+ AM | 0.0006 | 0.0005 | 0.0157 |

| HC+ PM | 0.9458 | 0.9342 | — |

Note: Reactivity scores are collapsed across morning and afternoon sessions and are the difference between the mean of three cortisol samples taken during the stress period and the mean of the corresponding samples during the rest day. HC = hormonal contraceptive

Heart rate responses to stress were recorded to represent the autonomic arm of the stress axis. We addressed the question of whether the HC groups differed in heart rate during the stress protocol relative to the resting control day at either the morning or afternoon test sessions, as shown in Table 4. A general linear model on heart rate reactivity, including HC group, time of day, and the interaction, showed that there were no significant differences for any of the terms.

Table 4.

Heart rates in women on rest and stress days

| HC− | HC+ | |||

| Stress Day | ||||

| Baseline | 73 | 0.62 | 73 | 0.71 |

| Speech Preparation | 81 | 0.74 | 82 | 0.98 |

| Mental arithmetic | 78 | 0.81 | 81 | 1.07 |

| Recovery | 72 | 0.66 | 73 | 0.79 |

| Rest Day | ||||

| Baseline | 73 | 0.65 | 73 | 0.79 |

| Rest 1 | 71 | 0.64 | 72 | 0.76 |

| Rest 1 | 70 | 0.71 | 72 | 0.85 |

| Recovery | 70 | 0.68 | 72 | 0.78 |

| General Linear Model of heart rate reactivity scores | ||||

| F value | p-value | |||

| HC | 0.00 | 0.9706 | ||

| Time of Day | 0.10 | 0.7527 | ||

| Interaction | 1.30 | 0.2556 | ||

Note. Entries show Mean ± SEM. Rest 1 and 2 during the rest day protocol correspond to speech preparation and mental arithmetic periods in the stress protocol. Reactivity scores are the difference between the means of the values recorded during the stress period and the comparable periods during the rest day. HC = hormonal contraceptive

Since hormonal contraceptive use could have effects on cognitive interpretation or emotional experience of the stressors, we examined subjective responses to the stressors in the HC groups and found no main effects or interaction for ratings of activation (Fs ≤ 3.83, ps > .05) or for ratings of distress (Fs ≤ 1.01, ps > .31) (data not shown). Although HC use did not affect how the women experienced acute stress situation, there remained a possibility that HC groups differed in long-term affective disposition. The current data set had measures of the BDI, the EPI-N, and the CPI-So that we considered useful for this purpose. Table 5 shows scores on these measures for the HC groups. The HC+ women had lower scores on BDI and EPI-N and modestly higher scores on CPI-So. We then tested models that included the covariates, CPI-So, BDI, EPI-N, SES, and smoking status, and found that the F values remained statistically significant in all cases (HC group effects, Fs ≥ 22.4, ps < .0001, and HC group x time of day interaction terms, Fs ≥ 4.17, ps ≤ .017).

Table 5.

Measures of affect in relation to HC use

| HC− | HC+ | Student’s t | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPI Neuroticism | 6.79 (0.26) | 5.54 (0.32) | 2.93 | 0.004 |

| CPI-So | 31.88 (0.30) | 33.02 (0.36) | 2.32 | 0.021 |

| Beck Depression | 4.84 (0.32) | 3.72 (0.34) | 2.41 | 0.016 |

Note: Entries show Mean ± SEM. HC = hormonal contraceptive

Discussion

The present data show that HC+ women, considered as a group, have attenuated cortisol responses to stress, in agreement with much prior research (Kirschbaum, Pirke, & Hellhammer, 1995; Kudielka, Hellhammer, & Wust, 2009; Kudielka et al., 1998; Winkler and Sudik, 2009). However, cortisol response attenuation in the present sample of HC+ women was confined to the morning hours. In the afternoon lab sessions, HC+ and HC– women had similar cortisol levels at rest and during stress. By comparison, men had the largest responses in both morning and afternoon sessions. Diminished cortisol reactivity in the HC+ women was not associated with alterations in autonomic responses to stress or in perception of the stressors, since heart rate changes and self-reports during the acute stress procedure were similar in both HC groups. HC+ women had modestly fewer symptoms of depression and greater emotional and behavioral stability.

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to contrast HC+ and HC– women on basal and stress levels of cortisol secretion during the morning and the afternoon hours. Prior work showed that oral contraceptives raised levels of both bound and unbound blood cortisol (Klose et al., 2007; Kuhl, et al., 1993; Simunkova et al., 2008; Winkler and Sudik, 2009), with values of unbound cortisol being about double those in unmedicated women, and these elevated values appeared to be confined to the morning hours (Meulenberg and Hofman, 1990). In the present data, HC+ women also had elevated morning session cortisol values starting at 9:00 am, accompanied by attenuated stress responses. However, during the early afternoon, HC+ women normal basal cortisol levels and reactivity values in reference to the HC– women.

The impact of HC use on rest-day free cortisol values raise three points of interest. First, the waking and bedtime cortisol samples provide a pair of anchor points to the daytime data. As shown in Figure 1 panel D, the HC+ and HC– women, and the men, all had nearly identical waking and bedtime cortisol values, suggesting comparable intrinsic regulation of cortisol secretion. Basal cortisol values appeared to be perturbed in the HC+ group only during the morning lab visits. Second, relative to their normal waking values at home, HC+ women had elevated cortisol levels at 9:00 am on both the rest and stress days (Figure 1, Panel B). This 9:00 am elevation was not present in the other groups (Figure 1, Panel D). Others have also reported a shift in the morning cortisol peak in HC+ women (Meulenberg and Hofman, 1990). Third, the substantial elevations in saliva free cortisol across the morning hours in the HC+ women signify a pharmacologic effect of HC that may increase cortisol’s level of feedback to brain structures, including the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala, that regulate decision-making, memory, and moods (Buchanan, al’Absi, & Lovallo, 1999; Buchanan, Brechtel, Sollers, & Lovallo, 2001; Buchanan and Lovallo, 2001; Cahill et al., 1996; Chan, Chow, Hamson, Lieblich, & Galea, 2014; De Kloet and Reul, 1987; Het and Wolf, 2007). These actions of cortisol have been documented in studies of acute and chronic corticosteroid administration (Buchanan, et al., 2001; Buchanan and Lovallo, 2001; Lovallo, Robinson, Glahn, & Fox, 2010). In the present study, HC+ women had greater levels of mood stability and social connectedness than the HC– group (Table 5). Although these differences were statistically significant, they were also small and very likely of limited clinical significance.

The means by which HCs modify morning cortisol levels and responses is not fully understood. One explanation is that HC use roughly doubles the levels of cortisol binding globulin (CBG) (Aden, Jung-Hoffmann, & Kuhl, 1998) resulting in increased circulating cortisol. Although CBG may account for increases in circulating cortisol, it does not account for the substantially elevated morning levels of free cortisol seen here and in other studies (Carr, et al., 1979; Kuhl, et al., 1993). In addition, CBG levels alone do not account for variation in free cortisol from morning to afternoon in the HC+ women, since CBG does not appear to vary across the waking hours (Coolens, Van Baelen, & Heyns, 1987; Lewis and Elder, 2013). The source of cortisol variation in the HC+ women remains unclear pending further endocrine studies.

The present study has two main strengths. The study sample is large. The subjects were all tested on a stress day in comparison to a resting control day, allowing a strong basis for diurnal controls in evaluating cortisol reactivity in the HC+ women. These data do not provide information on menstrual cycle effects in this protocol due to the complexities of scheduling rest- and stress-day sessions in coordination with menstrual cycle phases. Menstrual influences on cortisol reactivity have been carefully documented elsewhere (Kirschbaum, et al., 1999; Marinari, Leshner, & Doyle, 1976). Accordingly, the results in the HC– women may have unknown influences due to lack of menstrual cycle controls. However, menstrual cycle effects seem less likely to account for these findings in women taking hormonal contraceptives. Nonetheless, additional tests in HC– women with careful documentation of cycle phase would clarify this aspect of the present data.

The HC+ women tested in the morning showed elevated cortisol baseline values on the resting control day and stress day (Figure 1B). This suggested an elevated morning baseline level due to hormonal status. However, alternative hypotheses are possible and cannot be ruled out from the present data. One such hypothesis is that the HC+ women tested in the morning had been exposed to stress on their initial lab visit and may have still been in an anticipatory state on the second lab visit on the rest day. This could account for an elevated baseline on the rest day. We note that the self report data do not reveal a greater sense of anticipation in this group on the rest day. In addition, the HC+ women tested in the afternoon show a decreased baseline on the rest day, indicating a lack of potential anticipatory anxiety. However, the question may be addressable in a counterbalanced design in which rest days occur on day 1 for some subjects and day 2 for others. In addition, the same women could serve in both morning and afternoon test sessions.

Conclusion

HC+ women show very large elevations in nonstressed cortisol secretion during the early to midmorning hours relative to HC– controls. This morning elevation is accompanied by an absence of cortisol stress response to mental arithmetic and public speaking challenges. In the midafternoon hours, HC+ women have normal levels of basal secretion and normal levels of cortisol response to these stressor challenges. The morning attenuation of cortisol reactivity in HC+ women is not accompanied by altered autonomic response, indexed by heart rate, or to differences in subjective experience of the stressors. Additional information would become available in future studies examining morning and afternoon stress reactivity in HC– women in whom detailed menstrual phase data is collected. Inclusion of HC+ women in studies of stress reactivity should consider time of day in the planning of test sessions.

Acknowledgements

Supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Research Service, the National Institutes of Health, NIAAA, R01 AA012207. The content is solely the view of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health or the VA.

Footnotes

Author Declarations

William R. Lovallo declares no conflict of interest

Andrew J. Cohoon declares no conflict of interest

Andrea S. Vincent declares no conflict of interest

Ashley Acheson declares no conflict of interest

Kristen H. Sorocco declares no conflict of interest

References

- Aden U, Jung-Hoffmann C, & Kuhl H (1998). A randomized cross-over study on various hormonal parameters of two triphasic oral contraceptives. Contraception, 58(2), pp. 75–81. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9773261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’Absi M, Bongard S, Buchanan T, Pincomb GA, Licinio J, & Lovallo WR (1997). Cardiovascular and neuroendocrine adjustment to public speaking and mental arithmetic stressors. Psychophysiology, 34(3), pp. 266–275. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=9175441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association, A. P. (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th (text rev.) ed.) Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, & Beamesderfer A (1974). Assessment of depression: the depression inventory. Modern Problems of Pharmacopsychiatry, 7(0), pp. 151–169. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4412100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan TW, al’Absi M, & Lovallo WR (1999). Cortisol fluctuates with increases and decreases in negative affect. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 24(2), pp. 227–241. doi:S0306–4530(98)00078-X [pii] Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=10101730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan TW, Brechtel A, Sollers JJ, & Lovallo WR (2001). Exogenous cortisol exerts effects on the startle reflex independent of emotional modulation. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, 68(2), pp. 203–210. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11267624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan TW, & Lovallo WR (2001). Enhanced memory for emotional material following stress-level cortisol treatment in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 26(3), pp. 307–317. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11166493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, Haier RJ, Fallon J, Alkire MT, Tang C, Keator D, … McGaugh JL (1996). Amygdala activity at encoding correlated with long-term, free recall of emotional information. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 93(15), pp. 8016–8021. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=8755595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr BR, Parker CR Jr., Madden JD, MacDonald PC, & Porter JC (1979). Plasma levels of adrenocorticotropin and cortisol in women receiving oral contraceptive steroid treatment. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 49(3), pp. 346–349. doi:10.1210/jcem-49-3-346 Retrieved from 10.1210/jcem-49-3-346https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/224073 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/224073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan M, Chow C, Hamson DK, Lieblich SE, & Galea LA (2014). Effects of chronic oestradiol, progesterone and medroxyprogesterone acetate on hippocampal neurogenesis and adrenal mass in adult female rats. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 26(6), pp. 386–399. doi:10.1111/jne.12159 Retrieved from 10.1111/jne.12159http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24750490 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24750490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coolens JL, Van Baelen H, & Heyns W (1987). Clinical use of unbound plasma cortisol as calculated from total cortisol and corticosteroid-binding globulin. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry, 26(2), pp. 197–202. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3560936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler CA, & Klerman EB (1999). Circadian and sleep-dependent regulation of hormone release in humans. Recent Progress in Hormone Research, 54, pp. 97–130; discussion 130–132. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=10548874 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallman MF, Akana SF, Laugero KD, Gomez F, Manalo S, Bell ME, & Bhatnagar S (2003). A spoonful of sugar: feedback signals of energy stores and corticosterone regulate responses to chronic stress. Physiology and Behavior, 79(1), pp. 3–12. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=12818705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kloet ER, & Reul JM (1987). Feedback action and tonic influence of corticosteroids on brain function: a concept arising from the heterogeneity of brain receptor systems. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 12(2), pp. 83–105. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=3037584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SS, & Kemeny ME (2004). Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychological Bulletin, 130(3), pp. 355–391. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15122924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck SB, & Eysenck HJ (1964). An improved short questionnaire for the measurement of extraversion and neuroticism. Life Sciences, 305, pp. 1103–1109. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=14225366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough HG (1994). Theory, development, and interpretation of the CPI socialization scale. Psychological Reports, 75(1 Pt 2), pp. 651–700. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7809335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Het S, & Wolf OT (2007). Mood changes in response to psychosocial stress in healthy young women: effects of pretreatment with cortisol. [Clinical Trial Comparative Study Randomized Controlled Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Behavioral Neuroscience, 121(1), pp. 11–20. doi:10.1037/0735-7044.121.1.11 Retrieved from 10.1037/0735-7044.121.1.11http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17324047 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17324047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Kudielka BM, Gaab J, Schommer NC, & Hellhammer DH (1999). Impact of gender, menstrual cycle phase, and oral contraceptives on the activity of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. Psychosomatic Medicine, 61(2), pp. 154–162. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=10204967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Pirke KM, & Hellhammer DH (1995). Preliminary evidence for reduced cortisol responsivity to psychological stress in women using oral contraceptive medication. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 20(5), pp. 509–514. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=7675935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Wust S, & Hellhammer D (1992). Consistent sex differences in cortisol responses to psychological stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 54(6), pp. 648–657. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1454958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose M, Lange M, Rasmussen AK, Skakkebaek NE, Hilsted L, Haug E, … Feldt-Rasmussen U (2007). Factors influencing the adrenocorticotropin test: role of contemporary cortisol assays, body composition, and oral contraceptive agents. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 92(4), pp. 1326–1333. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-1791 Retrieved from 10.1210/jc.2006-1791https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17244781 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17244781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudielka BM, Hellhammer DH, & Wust S (2009). Why do we respond so differently? Reviewing determinants of human salivary cortisol responses to challenge. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34(1), pp. 2–18. doi:S0306–4530(08)00264–3 [pii] 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.10.004 Retrieved from 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.10.004http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19041187 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19041187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudielka BM, Hellhammer J, Hellhammer DH, Wolf OT, Pirke KM, Varadi E, … Kirschbaum C (1998). Sex differences in endocrine and psychological responses to psychosocial stress in healthy elderly subjects and the impact of a 2-week dehydroepiandrosterone treatment. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 83(5), pp. 1756–1761. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=9589688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl H, Jung-Hoffmann C, Weber J, & Boehm BO (1993). The effect of a biphasic desogestrel-containing oral contraceptive on carbohydrate metabolism and various hormonal parameters. Contraception, 47(1), pp. 55–68. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8436002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JG, & Elder PA (2013). Intact or “active” corticosteroid-binding globulin (CBG) and total CBG in plasma: determination by parallel ELISAs using monoclonal antibodies. Clinica Chimica Acta, 416, pp. 26–30. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2012.11.016 Retrieved from 10.1016/j.cca.2012.11.016https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23178744 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23178744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovallo WR, Farag NH, Sorocco KH, Acheson A, Cohoon AJ, & Vincent AS (2013). Early life adversity contributes to impaired cognition and impulsive behavior: studies from the Oklahoma Family Health Patterns Project. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 37(4), pp. 616–623. doi:10.1111/acer.12016 Retrieved from 10.1111/acer.12016http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23126641 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23126641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovallo WR, Farag NH, & Vincent AS (2010). Use of a resting control day in measuring the cortisol response to mental stress: diurnal patterns, time of day, and gender effects. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 35(8), pp. 1253–1258. doi:S0306–4530(10)00060–0 [pii] 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.02.015 Retrieved from 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.02.015http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=20233640 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=20233640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovallo WR, Robinson JL, Glahn DC, & Fox PT (2010). Acute effects of hydrocortisone on the human brain: an fMRI study. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 35(1), pp. 15–20. doi:S0306–4530(09)00287-X [pii] 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.09.010 Retrieved from 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.09.010http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19836143 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19836143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg U (1980). Catecholamine and cortisol excretion under psychologically different laboratory conditions In Usdin RKE, & Kopin I (Ed.), Catecholamines and stress: Recent advances. The Netherlands: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Marinari KT, Leshner AI, & Doyle MP (1976). Menstrual cycle status and adrenocortical reactivity to psychological stress. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.]. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 1(3), pp. 213–218. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/996215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meites K, Lovallo W, & Pishkin V (1980). A comparison of four scales for anxiety, depression, and neuroticism. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 36(2), pp. 427–432. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7372812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meulenberg PM, & Hofman JA (1990). The effect of oral contraceptive use and pregnancy on the daily rhythm of cortisol and cortisone. Clinica Chimica Acta, 190(3), pp. 211–221. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2253401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche DJ, King AC, Cohoon AJ, & Lovallo WR (2013). Hormonal contraceptive use diminishes salivary cortisol response to psychosocial stress and naltrexone in healthy women. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, 109, pp. 84–90. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2013.05.007 Retrieved from 10.1016/j.pbb.2013.05.007https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23672966 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23672966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saab PG, Matthews KA, Stoney CM, & McDonald RH (1989). Premenopausal and postmenopausal women differ in their cardiovascular and neuroendocrine responses to behavioral stressors. Psychophysiology, 26(3), pp. 270–280. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=2756076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simunkova K, Starka L, Hill M, Kriz L, Hampl R, & Vondra K (2008). Comparison of total and salivary cortisol in a low-dose ACTH (Synacthen) test: influence of three-month oral contraceptives administration to healthy women. Physiological Research, 57 Suppl 1, pp. S193–199. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18271677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman ED, Fukushima D, Nogeire C, Roffwarg H, Gallagher TF, & Hellman L (1971). Twenty-four hour pattern of the episodic secretion of cortisol in normal subjects. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 33(1), pp. 14–22. doi:10.1210/jcem-33-1-14 Retrieved from 10.1210/jcem-33-1-14https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4326799 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4326799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler UH, & Sudik R (2009). The effects of two monophasic oral contraceptives containing 30 mcg of ethinyl estradiol and either 2 mg of chlormadinone acetate or 0.15 mg of desogestrel on lipid, hormone and metabolic parameters. Contraception, 79(1), pp. 15–23. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2008.08.011 Retrieved from 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.08.011https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19041436 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19041436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]