The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services convened the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee (PAGAC) and charged it with reviewing and summarizing the current scientific evidence linking physical activity to human health and function. The 2018 PAGAC Scientific Report1 serves as the basis for the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition.2 The 2018 Scientific Report extends the findings of the 2008 Scientific Report3 by examining a broader range of health outcomes and special populations that benefit from increased physical activity. In addition, the 2018 Scientific Report more closely examined the specific types, volumes, and intensities of physical activity that are associated with those benefits and now describes novel strategies for physical activity promotion at the population level. A full overview of the process and methods for compiling the scientific evidence, as well as the important new findings from the 2018 PAGAC Scientific Report, have recently been published.4 In this Opinion Piece, we summarize the important topics that were not addressed in 2008 (Table 1). The full 2018 Scientific Report is available at https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/report.aspx.

Table 1.

Summary of key new findings from the 2018 PAGAC Scientific Report.

| Target | Key finding |

|---|---|

| Early childhood (2–5 years) | PA lowers weight and fat gain. |

| PA is associated with better bone health. | |

| Older adults | Multicomponent PA reduces risk of fall-related injuries. |

| Aerobic and multicomponent PA improves physical function in the general older population, those with frailty, and those with other chronic conditions. | |

| Balance activities improve physical function. | |

| Sedentary behavior | There is a dose–response relationship between SB and all-cause and CVD mortality risk. |

| Direct relation between SB and incidence of CVD, type 2 diabetes, and 3 types of cancer. | |

| Risk associated with SB is attenuated with greater amounts of MVPA. | |

| Hypertension | An inverse, linear dose–response relationship exists between PA and incidence of hypertension. |

| Type 2 diabetes | An inverse, curvilinear dose–response relationship exists between MVPA and risk of type 2 diabetes that is independent of weight status. |

| In people with diabetes, there is an inverse association between the volume of physical activity and risk of CVD mortality. | |

| Aerobic and dynamic resistance exercise reduces the risk of progression of type 2 diabetes. | |

| Body weight/adiposity | There is an inverse relationship between PA and the trajectory of weight gain in adults and in children 6–17 years of age. |

| Attenuation in weight gain strongest for those spending >150 min/week in moderate-intensity activity and for those engaging in MVPA, | |

| Regular MVPA reduces the incidence of obesity and is positively associated with the maintenance of a healthy body weight. | |

| Brain health | PA improves cognitive function across the lifespan in people both with and without existing cognitive impairments. |

| PA improves quality of life, symptoms of anxiety and depression, and sleep. | |

| PA promotion | There has been an explosion of PA-relevant information and communication technologies can expand the reach, the tailored “touch”, and the sustained impact of interventions to those who could benefit most. |

| Activity-friendly physical and social environments are associated with more physically active lifestyles across several community sectors and settings. |

Abbreviations: CVD = cardiovascular disease; MVPA = moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity; PA = physical activity; PAGAC = Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee; SB = sedentary behavior.

1. Physical activity in early childhood

The first edition of the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, released in 2008, included physical activity recommendations for children and youth.5 Those 2008 Guidelines applied only to school-age children (6–17 years), because at that time, the body of knowledge on the health effects of physical activity in children <6 years of age was too limited to support any conclusions. The absence of physical activity recommendations for early childhood has changed, owing to important developments over the decade between the release of the first and second editions of the Physical Activity Guidelines. Most important, the evidence linking physical activity to health during early childhood has expanded markedly. Also, during that period, physical activity recommendations for young children were produced by the Institute of Medicine in the United States and by public health authorities in several other countries.6, 7

The more recent research on the health effects of physical activity in young children focuses largely on children of preschool age (3–5 years). Further, this research targets indicators of 2 critical pediatric health outcomes—weight status/adiposity and bone health. The 2018 PAGAC concluded that, for both weight status/adiposity and bone health, there was strong evidence linking higher levels of physical activity to better outcomes in 3- to 5-year-old children. For weight status/adiposity, this conclusion was based on the consideration of 15 studies, all of which used prospective, observational study designs. Twelve of those studies reported that higher levels of physical activity were associated with lower rates of gain in weight and/or fat mass in early childhood. For bone health, 3 studies using either experimental or prospective, observational designs were available, and all 3 reported the positive effects of higher levels of physical activity on bone strength in 3- to 5-year-olds.

Although substantial, the evidence linking physical activity to health in early childhood has some limitations. For instance, existing data do not allow a clear assessment of dose–response relationships, and, therefore, it is not currently possible to identify a specific amount of physical activity that is needed to produce these observed health benefits. Future research should specifically address this limitation. In addition, research is needed to determine whether or not physical activity influences other important health outcomes of early childhood, such as indicators of cardiometabolic health and brain health.

2. Aging and chronic conditions

Evidence from randomized trials linking regular physical activity to major health benefits in aging has grown rapidly in the past 10 years—and the findings in older adults are even more impressive than they are at younger ages. In the 2008 PAGAC Scientific Report, there was strong evidence that exercise programs targeted toward fall prevention substantially decreased the risk of falls, and that balance training was an effective component of such programs. Now there is strong evidence that multicomponent programs can reduce the risk of injuries resulting from falls, with meta-analyses reporting risk reductions of ≥40%.

There is now strong evidence that aerobic activity and muscle-strengthening activities improve physical function in older adults. Moderate evidence also indicates that balance activities improve physical function in this age group, thereby supporting recommendations for balance training among all older adults (rather than for only those at increased fall risk). Moreover, any concerns that the benefits of physical activity to physical function may decrease with older age and be mitigated by frail health are not supported by current evidence. Indeed, although limited evidence suggests that age does not influence the effect of physical activity on physical function, there was strong evidence that even adults with existing frailty can benefit from adding physical activity to their lifestyle. In fact, there is now strong or moderate evidence that physical activity provides health benefits to people with a wide variety of chronic conditions, including type 2 diabetes, stroke, multiple sclerosis, osteoarthritis, Parkinson disease, and 3 types of cancer.

The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines continue to affirm the importance of regular aerobic activities, such as walking for older people. However, they also emphasize multicomponent physical activity and recommend including regular muscle strengthening and balance activities to the weekly physical activity plan. Moreover, data from randomized trials clearly demonstrate that the health benefits of this type of activity in older adults occur after relatively short periods of training (i.e., 3–12 months depending on the health outcome of interest), suggesting that multicomponent physical activity may be our most potent countermeasure against aging-associated functional decline. Unfortunately, only about 20% of U.S. adults meet the 2008 federal guidelines for aerobic and muscle-strengthening activity. Therefore, the clinical and public health benefits of increasing levels of multicomponent activity in older adults are substantial. The first sentence of the Executive Summary of the 2018 PAGAC Scientific Report states that the evidence “abundantly demonstrates that physical activity is a ‘best buy’ for public health”. Nowhere is the evidence for this statement more compelling than in older adults.

3. Sedentary behavior

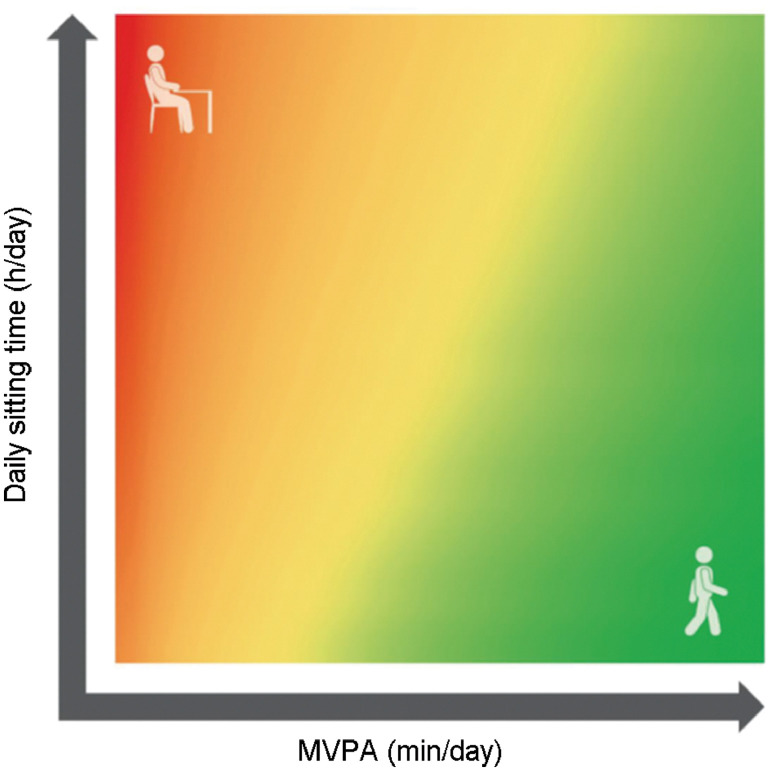

The 2018 PAGAC Scientific Report identifies a direct relationship between sedentary behavior and all-cause and cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality, incidence of CVD and type 2 diabetes, as well as the incidence of endometrial, colon, and lung cancers. Mortality risk increases in a dose–response manner with increasing amounts of sitting time; however, this sedentary-related mortality risk is attenuated with greater volumes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA).8 In fact, for individuals reporting the greatest volume of MVPA (about 35–38 metabolic equivalent of task hours (MET-h) per week), the excess mortality risk within different categories of sitting seems to be negligible, thus indicting a robust interaction between physical activity and sedentary time. For instance, sedentary time, as well as light physical activity and MVPA interact within a finite, 24-hour day. The 2018 PAGAC developed a heat map illustrating the interplay between various combinations of sitting time and MVPA and their joint effects on all-cause mortality (Fig. 1). The heat map was derived from regression techniques based on harmonized data from a meta-analysis by Ekelund et al.8 An assumption was made that, for any given level of MVPA, the time spent sitting and the time spent in light intensity physical activity are reciprocal. Thus, greater amounts of sitting time over the course of a day will displace light-intensity physical activity and vice versa. As indicated by the heat map: (1) at low levels of MVPA, replacing sitting time with light-intensity physical activity reduces the risk of premature mortality; (2) MVPA is necessary to achieve the greatest risk reduction; (3) for an equivalent reduction in risk, increasing MVPA requires appreciably less time per day than increasing light-intensity physical activity; and (4) at the highest levels of MVPA (about 35–38 MET-h/week), the time spent sitting has a negligible effect on mortality risk.

Fig. 1.

Relationship among moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), sitting time, and risk of all-cause mortality. The red zone illustrates greater mortality risk with higher amounts of sitting time combined with low levels of MVPA (top left corner). The green zone illustrates how higher amounts of MVPA can mitigate the risk of even moderate-to-high levels of sitting time (top right area).

4. Physical activity and hypertension

The 2018 PAGAC Scientific Report cites strong evidence for a linear, inverse dose–response relationship between leisure time physical activity of any intensity and incident hypertension, with no upper threshold of benefit among adults with normal blood pressure. For each 10 MET-h/week increment in leisure time physical activity, the risk of developing hypertension decreases by 6%.9 Among people with hypertension, increasing the systolic blood pressure will increase the risk of CVD mortality; however, this excess CVD mortality is blunted among those who are more physically active.

Improvements in blood pressure with regular physical activity depend on the initial blood pressure levels of an individual, with the greatest improvements observed in those with the greatest impairments. Adults with hypertension may experience an improvement of about 4%–6% of their resting blood pressure level (5–8 mm Hg), followed by those with prehypertension (2%–4% of resting level; 2–4 mm Hg), and those with normal blood pressure (1%–2% of resting level; 1–2 mm Hg). These improvements occur immediately after an exercise session and seem to be independent of exercise modality. This latter finding is a departure from the current exercise and hypertension guidelines that recommend aerobic over dynamic resistance exercise for the prevention and treatment of hypertension.10

5. Physical activity and type 2 diabetes

The 2018 PAGAC also found strong evidence of an inverse curvilinear dose–response relationship between MVPA and the development of type 2 diabetes that was independent of weight status. Indeed, 150–300 min/week of moderate-intensity activity decreases the risk of diabetes by 25%–35%. There is also strong evidence of an inverse association between the volume of physical activity and risk of CVD mortality (a 30%–40% decrease in risk), which is the most common cause of death among adults with type 2 diabetes and an indicator of disease progression. The PAGAC examined 4 indicators of type 2 diabetes risk progression that included hemoglobin A1C, blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), and blood lipid concentrations. The new findings indicate that aerobic and dynamic resistance exercise (performed alone or combined) reduces the risk of progression of type 2 diabetes, with the strength of the relationship varying by individual risk factor. Again, those with the greatest levels of impairment in hemoglobin A1C, blood pressure, or lipid concentrations experience the greatest improvements in cardiometabolic health and the magnitude of these health effects is greater the longer one participates in exercise. Regular physical activity also improves insulin sensitivity, with transient benefits occurring immediately after exercise.

6. Physical activity and weight/adiposity

The 2008 PAGAC Scientific Report concluded that physical activity was associated with modest weight loss, prevention of weight regain, and decreases in total and regional adiposity. The focus of the 2018 PAGAC Scientific Report was on the primary prevention of excessive weight gain. The 2018 Scientific Report describes a strong inverse relationship between physical activity and the trajectory of weight gain in adults, with the attenuation in weight gain strongest for those spending more than 150 min/week in moderate-intensity activity and for those engaging in MVPA. Regular MVPA also reduces the incidence of obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) and is positively associated with the maintenance of a healthy body weight (BMI: 18.5–24.9 kg/m2).

Among children 6–17 years of age, the 2018 Scientific Report cites strong evidence from prospective, observational studies that higher levels of physical activity are associated with smaller increases in body weight and adiposity. These benefits are observed in both boys and girls, as well as in preschool children. Although the data are limited, there is some evidence that sedentary behavior is associated with higher weight status or adiposity in children and adolescents; however, the evidence is stronger for television viewing and screen time than for total device-based sedentary time.

7. Brain health and cognition

The topic of Brain Health was added to the 2018 PAGAC Scientific Report owing to the expanding body of evidence citing the benefits of regular physical activity to cognition, affect, and sleep. The 2018 Scientific Report now indicates that physical activity positively influences cognitive function across the lifespan in people both with and without existing cognitive impairments and that these benefits are consistent across a variety of methods for assessing cognition. The 2018 Scientific Report also describes for the first time the positive effects of physical activity on biomarkers of brain health (e.g., brain volume) that were obtained from neuroimaging techniques and describes evidence on the acute effects of single exercise bouts on improvements in cognitive function.

The evidence linking physical activity to mental health is now described in greater depth than in the 2008 Scientific Report. For example, the 2018 Scientific Report highlights the benefits of physical activity to validated indicators of quality of life (QoL) (rather than a limited definition of “well-being”). Indeed, the 2018 Scientific Report describes the effects of physical activity on physical and mental domains of health-related QoL with data from clinical trials that were conducted across the lifespan and in populations that often show significant losses in QoL (e.g., people with schizophrenia). The 2018 Scientific Report also provides sound evidence that regular physical activity is an effective treatment for decreasing symptoms of anxiety and depression across multiple age groups and that both regular and single bouts of physical activity have positive effects on several different sleep outcomes, including sleep apnea.

8. Physical activity promotion

Strategies to promote physical activity and reduce sedentary behavior were not included in the 2008 Scientific Report or the 2008 Guidelines. Given the surplus of literature describing the effectiveness of different interventions for promoting physical activity at the individual level, it was surprising to discover that there were no definitive answers about what works best to promote and sustain an active lifestyle at the population level. The 2018 Scientific Report describes effective strategies targeted toward multiple levels within the social ecological framework. Indeed, many of the successful approaches described have been directed toward individuals via specific channels, such as telephone-based advice and support, text messaging, smartphone apps, and other forms of electronic communication. The explosion of physical activity-relevant information and novel communication technologies provides an unprecedented opportunity to expand the reach, the tailored “touch”, and the sustained impact of interventions to those who could benefit most. In addition, a large amount of evidence indicates that activity-friendly physical and social environments are associated with more physically active lifestyles across age groups, settings (school, workplace), and different forms of activity (recreation, active transport).

The 2018 Scientific Report also highlights what we still do not know about promoting physical activity. The primary knowledge gap relates to the “scaling up” of interventions that work well with motivated volunteers under standardized (i.e., ideal) conditions, but then break down under real-life conditions at the community or population level. In fact, translating findings from the laboratory to the population level remains a significant challenge for public health researchers and practitioners alike, and this is even more problematic when working with under-represented and/or low-resourced communities.

9. Conclusion

Findings from the 2018 Scientific Report continue to underscore the public health impact of increasing population levels of regular physical activity and provide a firm foundation for the new federal physical activity guidelines for Americans. Regular physical activity can prevent the most common causes of early mortality, as well as the most prevalent chronic conditions and most expensive medical conditions in the United States.4 Thus, even small increases in regular physical activity, especially if made by the least physically active individuals, would appreciably decrease the burden and cost of lifestyle-related disease in the United States.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

References

- 1.Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee . U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2018. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. [Google Scholar]

- 2.2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2nd ed. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2018. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee . U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2008. 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powell K.E., King A.C., Buchner D.M., Campbell W.W., DiPietro L., Erickson K.I. The scientific foundation of the physical activity guidelines for Americans. J Phys Act Health. 2019;17:1–11. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2018-0618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2008. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGuire S. Institute of Medicine (IOM) Early childhood obesity prevention policies. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. Adv Nutr 2012;3:56–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Pate R.R., O'Neill J.R. Physical activity guidelines for young children: an emerging consensus. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:1095–1096. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ekelund U., Steene-Johannessen J., Brown W.J., Fagerland M.W., Owen N., Powell K.E. Does physical activity attenuate, or even eliminate, the detrimental association of sitting time with mortality? A harmonised meta-analysis of data from more than 1 million men and women. The Lancet. 2016;388:1302–1310. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30370-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu X., Zhang D., Liu Y., Sun X., Han C., Wang B. Dose-response association between physical activity and incident hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Hypertension. 2017;69:813–820. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.08994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pescatello L.S. Exercise measures up to medication as antihypertensive therapy: its value has long been underestimated. Br J Sports Med. 2018 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-100359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]