Abstract

15q13.3 syndrome is associated with a wide spectrum of neurological disorders. Among a cohort of 150 neurodevelopmental cases, we identified two patients with two close proximity interstitial hemizygous deletions on chromosome 15q13. Using high-density microarrays, we characterized these deletions and their approximate breakpoints. The second deletion in both patients overlaps in a small area containing CHRNA7 where the gene is partially deleted. The CHRNA7 is considered a strong candidate for the 15q13.3 deletion syndrome’s pathogenicity. Patient 1 has cognitive impairment, learning disabilities, hyperactivity and subtle dysmorphic features whereas patient 2 has mild language impairment with speech difficulty, mild dysmorphia, heart defect and interestingly a high IQ that has not been reported in 15q13.3 syndrome patients before. Our study presents first report of such two successive deletions in 15q13.3 syndrome patients and a high IQ in a 15q13.3 syndrome patient. Our study expands the breakpoints and phenotypic features related to 15q13.3 syndrome.

Keywords: 15q13.3 syndrome, Consecutive deletions, High IQ, CHRNA7, Hyperactivity, Cognitive impairment, And learning disability

Background

15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome (MS) expands on approximately 1.5 Mbp on chromosome 15q. This region is also known to involve in other diseases such as Prader Willi, Angelman syndrome, and autism [1, 2]. The syndrome has a wide spectrum of phenotypic consequences even within the same family. Patients exhibit various degrees of intellectual disabilities ranging from rarely normal intelligence to a high degree of impairment that leads to severe learning difficulties. The condition may include various dysmorphic characteristics, neurodevelopmental phenotypes, impaired vision as well as psychiatric problems, such as schizophrenia and epilepsy with recurring seizures or in some cases asymptomatic [3–8]. 15q13.3 MS may appear as de novo or could be transmitted in an autosomal dominant mode with reduced penetrance. Presence of homozygous microdeletions have also been reported [9, 10]. The prevalence of the disease remains unknown [1, 10–16]. However, a recent study estimated that 1 in 5525 live birth has a pathogenic 15q13.3 microdeletion, which can indicates that the syndrome is under-diagnosed [17].

In this study, a pool of 150 cases suspected to have chromosomal abnormalities, including dysmorphia, autism, language delay, ADHD, speech and developmental delay, were examined. The investigation was carried out by different types of oligonucleotide microarrays. Among the cohort, two cases related to 15q13.3 deletion syndrome were identified. Both patients have consecutive microdeletions separated by an intact region in the 15q13 cytogenetic bands where CHRNA7 is partially deleted.

Clinical presentation

Patient 1 The patient is an 8 ½ -year-old boy presented with hyperactivity, cognitive impairment, learning disabilities and subtle dysmorphic features. He was born at term to non-consanguineous parents. Pregnancy history was not remarkable and there were no postnatal complications. He was said to be floppy initially, but managed to sit by the age of 8 months, and walked by his 15th month. Additionally, language abilities are significantly delayed and he is currently able to say comprehensible sentences of 3–4 words only. He was also noted to be hyperactive with stereotypic hands movements which improved significantly after some sessions of behavioral therapy. His parents noted improvement in his social skills after he was on methylphenidate hydrochloride with a dose of 36 mg once daily 2 years ago. His IQ was graded as 70 at the age of 6 years and was attending a special needs school. Upon examination, his weight was 21 kg at the 5th centile, height was 126.6 cm (> 25th <50th centile) and his head circumference was 53 cm (slightly above the 50th centile). He showed subtle dysmorphic features with large ears, prominent nasal tip, clinodactyly of the fifth finger and persistent fetal fingertip pads. There was one tiny pigmented naevus on the left cheek and another two (about 0.5 cm) over the abdomen and back. Cranial nerves were intact and he had normal tone, power and reflexes in the upper and the lower limbs with normal gait.

Patient 2 The patient is a 17-year-old female who has been followed up at King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center (KFSHRC) for nearly 15 years. The patient was referred to KFSHRC with the suspicion of autism and had history of speech and language delay. She had normal pre- and perinatal history with slow milestones in language areas. She was given Beery-VMI, Leiter International Performance Scale, Selected subtests, and McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities (MSCA) at the age of 4-year-2-month-old. She managed a 3 and 5 block figures on MSCA without difficulty for an equivalency of 4+ years. She stacked only six blocks, showed some motor clumsiness. She speaks full sentences with reasonable clarity but her vocabulary was limited. She named only one of the picture vocabulary cards and was able to point 17 out of 19. She follows directions and her receptive language skills seem relatively impact. She did extremely well on the Leiter with an age equivalency of 5-years-5-months-old and IQ of 134. On the Beery-VMI she had similar but little lesser score. She showed poor pencil control with an age of equivalency of 42 months and a standard score of 93. There were no attention related problems. She was able to toilet herself with some help but could dress and feed herself without help. She was quite irritable and demanding, particularly with her parents, but not aggressive. At the age of 6 years, she had an echocardiogram that showed a redundant mildly prolapsed mitral valve. The cardiac muscle was mildly thickened, but otherwise normal in function. At the age of 7 years she was evaluated by a neurophysiologist due to speech delay and diagnosed with expressive language delay but normal psychomotor development. Her weight was only 15.3 kg, which is far below the 5th percentile; and her height was 104.5 cm, which is also far below 5th percentile. The second ECG was also performed confirming previous findings of localized septal hypertrophy and redundant anterior mitral leaflet. At the age of 16 she has a short status found to have growth hormone deficiency and delayed puberty.

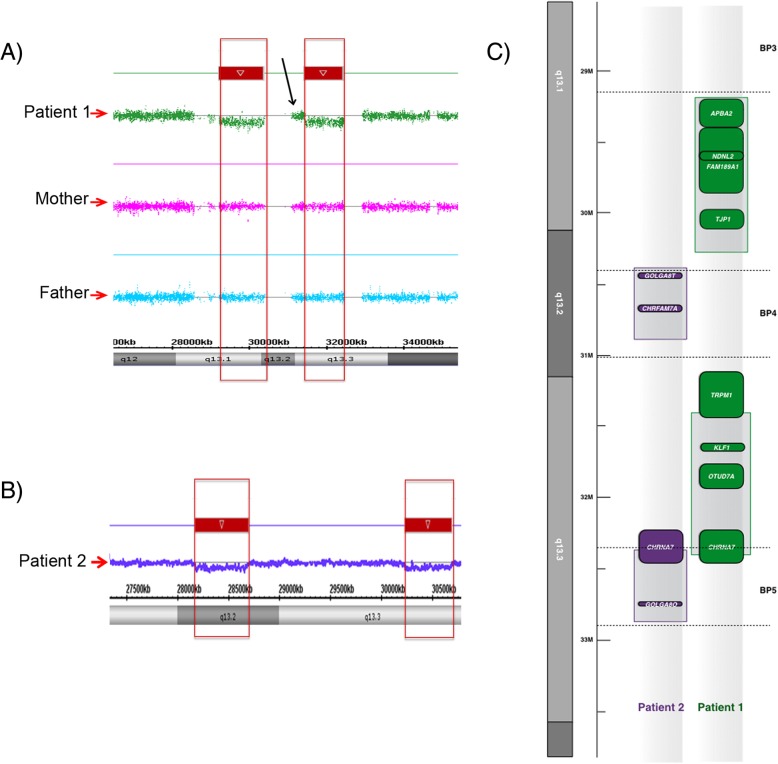

Molecular analysis of the patient 1 was done using high-resolution GTW-banding and high-density oligo arrays. High-resolution GTW-banding (550 band resolution) was carried out as part of diagnostic procedures and did not reveal any gross abnormality. Cytoscan HD arrays (Affymetrix Inc., San Paolo, CA, US) identified two deletions with close proximity on 15q13 cytogenetic. The second deletion sits on 15q13.3 band (Table 1, Fig. 1a). The deletion sites are covered by more than 1082 probes in the first and 1052 probes in the second deletions. There are probeless regions on both deletions making precise BP calculations difficult. Interestingly, an area covered by 435 SNP-CP probes between the deletions clearly demonstrated that these deletions are two separate unique deletions in the region (Fig. 1a). Parental DNA was tested using the same chip, no chromosomal imbalance was detected hence the hemizygous deletion in our patient is considered de novo.

Table 1.

Summary of Molecular and Clinical Findings in Patient 1 and Patient 2 compared to other cases with 15q13.3 deletion syndrome reviewed in Lowther et al. 2015

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Lowther et al. 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical features | |||

| Intellectual Disabilities | Present | _ | 59% |

| High IQ | _ | Present | Not reported |

| Autisistic Features | _ | Suspected | 10.9% |

| Speech | Delayed | Delayed | 15.9% |

| Hyperactivity | Present | _ | 4.5% |

| Congenital Malformation | _ | Present | 2.4% |

| Dysmorphic features | Present | Present | Not indicated |

| Molecular Analysis | |||

| FISH Analysis | N/A | ||

| GTW Banding | N/A | ||

| Microarrays | CytoHD | SNP Array 6.0 | N/A |

| Double Hit | N/A | ||

| 1st Deletion BP | 29,215,009–30,370,019(hg19; 1155 kbp) | 30,450,356–30,779,579 (hg19; 329 kbp) | N/A |

| 2nd Deletion BP | 31,444,122–32,446,830 (hg19;1003 kbp) | 32,561,665–32,876,972 (hg19; 315 kbp) | N/A |

| 1st Deletion Genes | APBA2, NDNL2, TJP1, FAM189A1 | GOLGA8T, CHRFAM7A | N/A |

| 2nd Deletion Genes | TRPM1, KLF13, OTUD7A, CHRNA7 | CHRNA7, GOLGA8O | N/A |

Fig. 1.

SNP array results for patient 1 and his parents, and patient 2 a) The patient and his parents are run on whole genome human cytogenetics 2.7 M arrays. The patient has consecutive hemizygous deletions separated by a probeless region next to a densely probed region (marked by a black arrow) comprising numerous SNP-CP probes. b The patient was tested on Affymetrix’s 6.0 Mapping Arrays. The analysis indicated two subsequent deletions separated by a large heavily probed region. c The alignment of the deletions present in both patients is shown

Patient 2 was also analyzed using GTW-banding that did not revealed any abnormality. However, similar to patient 1, SNP Array 6.0 (Affymetrix Inc.) indicated two consecutive deletions on 15q13. The first deletion is located on 15q13.2 while the second deletion resides on 15q13.3 (Table 1, Fig. 1b). During the analyses, we converted hg18 annotations to hg19 using UCSC’s Left Genome Annotations application for the purpose of comparison (Fig. 1c). The coordinates after the conversion are 30,450,356–30,779,579 (hg19) and 32,561,665–32,876,972 (hg19) for the first and the second deletion, respectively. The first deletion is pointed out by 95 CN and 2 SNP probes on 6.0 arrays whereas the second deletion is covered by only 43 CN probes on the same arrays. The parental DNA was not available for examination.

Discussion and conclusions

Six break points (BPs) have been characterized in 15q region, due to the prevalence of low-copy repeats in chromosome 15q11–13 that attributes for frequent deletion and duplication in the area [2]. Among these we focus on deletions extending on 15q13.3, where 264 cases have been found in the literature [18] . Here we present two cases; a male and a female, with two separate microdeletions reside within the 15q13 cytogenetic band. Although 15q13 arm is considered one of the most instability regions of the human genome [19], to the best of our knowledge, no patient has been reported to have such pattern of deletions in this region.

Patient 1 first deletion is located in 15q13.1 cytogenetic band, small number of deletions related to PW extend to reach BP4 where the deletion resides [20]. Moreover, cases of deletions between BP3 and BP4 were reported to suggest a link between developmental and neurological disorder phenotype [21]. In addition to chromosomal rearrangement, APBA2 (OMIM# 602712) located in the deleted area has been linked to neurological disorders. The gene encodes for amyloid precursor protein-binding protein A2. APBA2 is expressed in neuronal cytoplasm, it interacts with amyloid protein precursor and leads to the amyloid β protein production suppression, a key protein involved in Alzheimer’s pathogenesis [22]. Furthermore, duplications of APBA2 have been associated with Schizophrenia and Autism spectrum disorders [23, 24]. The second deletion contains OTUD7A (OMIM# 612024) and CHRNA7 (OMIM# 118511); both are closely associated with 15q13.3 phenotype [25]. On the other hand, cases with CHRNA7 haploinsufficiency only manifests the 15q13.3 deletion syndrome [12, 13]. CHRNA7 encodes α7 subunit of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor protein, among several, it is expressed the pre and post-synaptic region where it regulates both GABA and glutamate neurotransmitters in the hippocampus, it was also detected in the rat striatum dopaminergic neurons. CHRNA7 involves in Ca2+regulation, which then affect several Ca2+ dependent pathways [26]. It is worth to note that CHRNA7 is partially deleted in our patient. This gene has 10 exons, only half of which are deleted in our case. Although CHRNA7 is a strong candidate for the disease pathogenicity, a recent comprehensive study of OTUD7A human and mouse KO model, indicates that this gene contributes in brain development, moreover, abnormal morphology have been recorded in cortical neuronal and dendritic spine in mouse KO model. Hence, OTUD7A is a critical gene in the 15q13.3 disease manifestation and phenotypic variability [27].

The second patient’s microdeletions reside within 15q13.2 and 15q13.3. CHRFAM7A (OMIM # 609756) is one of the genes located within the first deletion; it is a fusion gene between a partial duplication of CHRNA7 and FAM7A [28], it has a dominant negative affect in the CHRNA7 function [29], variations in CHRFAM7A are linked to epilepsy, schizophrenia and bipolar disorders [30, 31]. While chromosomal rearrangements and duplication in 15q13.2 have been linked to autism [32, 33], similar to patient 1, CHRNA7 is partially deleted in the second deletion, where exons (5–10) are deleted.

Since describing 15q13.3 deletion syndrome by Sharp et al. in 2008, several reports has followed describing patients with complex variable phenotypes, included autism, seizure, dysmorphia among several, and different deletion sizes, reviewed in [18, 34]. An in depth study regarding 15q13.3 microdeletion, neuropsychiatric observations were reported in 80.5% of cases whereas developmental disabilities including speech and intellectual impairment as well as epilepsy and seizures were present in 73.6 and 28.0% of the cases, respectively. However, among the cohort, only 10–11% of patients had autism spectrum disorder or schizophrenia or mood disorder [18] and none had high IQ.

Here in, patient 1 has cognitive impairment, learning disabilities, hyperactivity and subtle dysmorphic features while patient 2 has dysmorphia, speech delay, congenital heart problems, delayed puberty and growth hormone deficiency. Interestingly patient 2 has been reported to have high IQ (IQ Score: 134). The prevalence of our patients’ phenotype in comparison to other cases reported in literature is illustrated in Table 1. It is worth mentioning that nonverbal reasoning IQ average is 60.1 [35]. It is estimated that15q13.3 microdeletion is 40–80% penetrant [17], this implies that the presence of individuals with high IQ is a possibility among carriers of the microdeletion whom does not exhibit the phenotype. Nevertheless, based on our intensive search of the literature, we have not encounter of such high IQ among the 15q13.3-S cases.

Moreover, a mouse model harboring a 15q13.3 hemizygous deletion was developed. The model demonstrated marked changes in neuronal excitability with epilepsy and schizophrenia [36]. In addition, several single gene KO mouse models have been developed in order to further understand the disease mechanism [27, 37, 38].

In summary, we present the first consecutive hemizygous microdeletions in chromosome 15q13 with atypical BPs, the two cases; a male and a female share a small overlapping region containing CHRNA7, and exhibit a phenotypic variation.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank to the patients and the parents for their kind participation to the study. We highly appreciate late Prof. Pinar T. Ozand who recruited the first patient to the study. We also thank KFSHRC Core Facilities at Genetics Department, Saudi Genome Program Director and Participants, KFSHRC’s Research Advisory Council Committees and Purchasing Departments, especially Mr. Faisal Al-Otaibi and his team, for facilitating and expediting our requests.

Funding

This study was generously funded by King Salman Center (KSCDR 02-R-0029-NE-02-AU-1 and KSCDR 2180 004) and also received generous funds under National Plan for Science, Technology and Innovation program from King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology for Dr. Namik Kaya (NSTIP/KACST, 14-MED2007–20) and Dr. Dilek Colak (11-BIO2072–20). The study was also supported by King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research center’s seed grants for Dr. Namik Kaya (KFSHRC-RAC# 2120022 2040042, 2030046, 2040024). MAS was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia through research group no RGP-VPP- 301.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Web resources

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/gdv/

Declaration

We have obtained consents from the studied patients for the study. The patients were evaluated at the Kind Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center using the institutionally approved IRB protocols (RAC# 2040042, 2,030,046, 2,120,022, 2,080,032).

Abbreviations

- ADHD

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- BEERY VMI

Beery-Buktenica Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration

- BPs

Breakpoints

- CNV

Copy number variation

- DGV

Database of genomic variants

- ECG

Echocardiogram

- GTW-banding

Giemsa banding using trypsin with Wright’s stain

- HD

High density

- IQ

Intelligence quotient

- KACST

King Abdulaziz Center for Science and Technology

- KFSHRC

King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research

- KSCDR

King Salman Center for disability research

- Mbp

Megabasepair

- MSCA

McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities

- OMIM

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Ma

Authors’ contributions

NK conceived and designed the experiments, drafted manuscript, reviewed the data analyses. DC and AA involved in experimental design and reviewed data analyses, involved in drafting the manuscript. MA involved in analyzing the data and drafting the manuscript. MAS, MHAH, MN, NS, reviewed the charts, evaluated the patients, undertook patient care and management, collected clinical data, delineated the patients’ phenotype. MD involved in drafting and reviewing the manuscript and helped to analyze the data. MA, YA, SMW, JA performed the experiments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Michael Nester - recently retired from KFSHR.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The patients were ascertained under one of the King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center’s institutionally approved IRB protocols (KFSHRC’s Research Advisory Council Committees (RAC# 2120022 2040042, 2030046, 2040024). Before the sample collection, the patients and/or parents (legal guardians) signed the written informed consents.

Consent for publication

Written informed consents were obtained from the related parties.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Maysoon Alsagob, Email: malsagob88@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Mustafa A. Salih, Email: mustafa_salih05@yahoo.com

Muddathir H. A. Hamad, Email: mudhamad@yahoo.com

Yusra Al-Yafee, Email: yalyafee@hotmail.com.

Jawaher Al-Zahrani, Email: jawaheralzahrani@gmail.com.

Albandary Al-Bakheet, Email: abinbakheet@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Michael Nester, Email: nestermj44@gmail.com.

Nadia Sakati, Email: nsakati@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Salma M. Wakil, Email: smajid@kfshrc.edu.sa

Ali AlOdaib, Email: odaib@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Dilek Colak, Email: dkcolak@gmail.com.

Namik Kaya, Phone: +966-1-464-7272, Email: nkaya@kfshrc.edu.sa, Email: namikkaya@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Sharp AJ, Mefford HC, Li K, Baker C, Skinner C, Stevenson RE, Schroer RJ, Novara F, De Gregori M, Ciccone R, et al. A recurrent 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome associated with mental retardation and seizures. Nat Genet. 2008;40(3):322–328. doi: 10.1038/ng.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pujana MA, Nadal M, Guitart M, Armengol L, Gratacos M, Estivill X. Human chromosome 15q11-q14 regions of rearrangements contain clusters of LCR15 duplicons. Eur J Hum Genet. 2002;10(1):26–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shinawi M, Schaaf CP, Bhatt SS, Xia Z, Patel A, Cheung SW, Lanpher B, Nagl S, Herding HS, Nevinny-Stickel C, et al. A small recurrent deletion within 15q13.3 is associated with a range of neurodevelopmental phenotypes. Nat Genet. 2009;41(12):1269–1271. doi: 10.1038/ng.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freedman R, Leonard S, Gault JM, Hopkins J, Cloninger CR, Kaufmann CA, Tsuang MT, Farone SV, Malaspina D, Svrakic DM, et al. Linkage disequilibrium for schizophrenia at the chromosome 15q13-14 locus of the alpha7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit gene (CHRNA7) Am J Med Genet. 2001;105(1):20–22. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20010108)105:1<20::AID-AJMG1047>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen NM, Conroy J, Shahwan A, Ennis S, Lynch B, Lynch SA, King MD. Excellent outcome with de novo 15q13.3 microdeletion causing infantile spasms--a further patient. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A(7):1863–1866. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Endris V, Hackmann K, Neuhann TM, Grasshoff U, Bonin M, Haug U, Hahn G, Schallner JC, Schrock E, Tinschert S, et al. Homozygous loss of CHRNA7 on chromosome 15q13.3 causes severe encephalopathy with seizures and hypotonia. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A(11):2908–2911. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lacaze E, Gruchy N, Penniello-Valette MJ, Plessis G, Richard N, Decamp M, Mittre H, Leporrier N, Andrieux J, Kottler ML, et al. De novo 15q13.3 microdeletion with cryptogenic West syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A(10):2582–2587. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prasun P, Hankerd M, Kristofice M, Scussel L, Sivaswamy L, Ebrahim S. Compound heterozygous microdeletion of chromosome 15q13.3 region in a child with hypotonia, impaired vision, and global developmental delay. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A(7):1815–1820. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lepichon JB, Bittel DC, Graf WD, Yu S. A 15q13.3 homozygous microdeletion associated with a severe neurodevelopmental disorder suggests putative functions of the TRPM1, CHRNA7, and other homozygously deleted genes. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A(5):1300–1304. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao J, DeWard SJ, Madan-Khetarpal S, Surti U, Hu J. A small homozygous microdeletion of 15q13.3 including the CHRNA7 gene in a girl with a spectrum of severe neurodevelopmental features. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A(11):2795–2800. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ben-Shachar S, Lanpher B, German JR, Qasaymeh M, Potocki L, Nagamani SC, Franco LM, Malphrus A, Bottenfield GW, Spence JE, et al. Microdeletion 15q13.3: a locus with incomplete penetrance for autism, mental retardation, and psychiatric disorders. J Med Genet. 2009;46(6):382–388. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.064378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoppman-Chaney N, Wain K, Seger PR, Superneau DW, Hodge JC. Identification of single gene deletions at 15q13.3: further evidence that CHRNA7 causes the 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome phenotype. Clin Genet. 2013;83(4):345–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masurel-Paulet A, Andrieux J, Callier P, Cuisset JM, Le Caignec C, Holder M, Thauvin-Robinet C, Doray B, Flori E, Alex-Cordier MP, et al. Delineation of 15q13.3 microdeletions. Clin Genet. 2010;78(2):149–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller DT, Shen Y, Weiss LA, Korn J, Anselm I, Bridgemohan C, Cox GF, Dickinson H, Gentile J, Harris DJ, et al. Microdeletion/duplication at 15q13.2q13.3 among individuals with features of autism and other neuropsychiatric disorders. J Med Genet. 2009;46(4):242–248. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.059907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pagnamenta AT, Wing K, Sadighi Akha E, Knight SJ, Bolte S, Schmotzer G, Duketis E, Poustka F, Klauck SM, Poustka A, et al. A 15q13.3 microdeletion segregating with autism. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17(5):687–692. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahoo T, Theisen A, Rosenfeld JA, Lamb AN, Ravnan JB, Schultz RA, Torchia BS, Neill N, Casci I, Bejjani BA, et al. Copy number variants of schizophrenia susceptibility loci are associated with a spectrum of speech and developmental delays and behavior problems. Genet Med. 2011;13(10):868–880. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182217a06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gillentine MA, Lupo PJ, Stankiewicz P, Schaaf CP. An estimation of the prevalence of genomic disorders using chromosomal microarray data. J Hum Genet. 2018;63(7):795–801. doi: 10.1038/s10038-018-0451-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowther C, Costain G, Stavropoulos DJ, Melvin R, Silversides CK, Andrade DM, So J, Faghfoury H, Lionel AC, Marshall CR, et al. Delineating the 15q13.3 microdeletion phenotype: a case series and comprehensive review of the literature. Genet Med. 2015;17(2):149–157. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szafranski P, Schaaf CP, Person RE, Gibson IB, Xia Z, Mahadevan S, Wiszniewska J, Bacino CA, Lalani S, Potocki L, et al. Structures and molecular mechanisms for common 15q13.3 microduplications involving CHRNA7: benign or pathological? Hum Mutat. 2010;31(7):840–850. doi: 10.1002/humu.21284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim SJ, Miller JL, Kuipers PJ, German JR, Beaudet AL, Sahoo T, Driscoll DJ. Unique and atypical deletions in Prader-Willi syndrome reveal distinct phenotypes. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20(3):283–290. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenfeld JA, Stephens LE, Coppinger J, Ballif BC, Hoo JJ, French BN, Banks VC, Smith WE, Manchester D, Tsai AC, et al. Deletions flanked by breakpoints 3 and 4 on 15q13 may contribute to abnormal phenotypes. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19(5):547–554. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomita S, Ozaki T, Taru H, Oguchi S, Takeda S, Yagi Y, Sakiyama S, Kirino Y, Suzuki T. Interaction of a neuron-specific protein containing PDZ domains with Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(4):2243–2254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Babatz TD, Kumar RA, Sudi J, Dobyns WB, Christian SL. Copy number and sequence variants implicate APBA2 as an autism candidate gene. Autism Res. 2009;2(6):359–364. doi: 10.1002/aur.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirov G, Gumus D, Chen W, Norton N, Georgieva L, Sari M, O'Donovan MC, Erdogan F, Owen MJ, Ropers HH, et al. Comparative genome hybridization suggests a role for NRXN1 and APBA2 in schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(3):458–465. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mikhail FM, Lose EJ, Robin NH, Descartes MD, Rutledge KD, Rutledge SL, Korf BR, Carroll AJ. Clinically relevant single gene or intragenic deletions encompassing critical neurodevelopmental genes in patients with developmental delay, mental retardation, and/or autism spectrum disorders. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A(10):2386–2396. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albuquerque EX, Pereira EF, Alkondon M, Rogers SW. Mammalian nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol Rev. 2009;89(1):73–120. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uddin M, Unda BK, Kwan V, Holzapfel NT, White SH, Chalil L, Woodbury-Smith M, Ho KS, Harward E, Murtaza N, et al. OTUD7A regulates neurodevelopmental phenotypes in the 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;102(2):278–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riley B, Williamson M, Collier D, Wilkie H, Makoff A. A 3-Mb map of a large segmental duplication overlapping the alpha7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor gene (CHRNA7) at human 15q13-q14. Genomics. 2002;79(2):197–209. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Araud T, Graw S, Berger R, Lee M, Neveu E, Bertrand D, Leonard S. The chimeric gene CHRFAM7A, a partial duplication of the CHRNA7 gene, is a dominant negative regulator of alpha7*nAChR function. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;82(8):904–914. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rozycka A, Dorszewska J, Steinborn B, Lianeri M, Winczewska-Wiktor A, Sniezawska A, Wisniewska K, Jagodzinski PP. Association study of the 2-bp deletion polymorphism in exon 6 of the CHRFAM7A gene with idiopathic generalized epilepsy. DNA Cell Biol. 2013;32(11):640–647. doi: 10.1089/dna.2012.1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flomen RH, Collier DA, Osborne S, Munro J, Breen G, St Clair D, Makoff AJ. Association study of CHRFAM7A copy number and 2 bp deletion polymorphisms with schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006;141B(6):571–575. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Christofolini DM, Meloni VA, Ramos MA, Oliveira MM, de Mello CB, Pellegrino R, Takeno SS, Melaragno MI. Autistic disorder phenotype associated to a complex 15q intrachromosomal rearrangement. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2012;159B(7):823–828. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu DJ, Wang NJ, Driscoll J, Dorrani N, Liu D, Sigman M, Schanen NC. Autistic disorder associated with a paternally derived unbalanced translocation leading to duplication of chromosome 15pter-q13.2: a case report. Mol Cytogenet. 2009;2:27. doi: 10.1186/1755-8166-2-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gillentine MA, Schaaf CP. The human clinical phenotypes of altered CHRNA7 copy number. Biochem Pharmacol. 2015;97(4):352–362. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ziats MN, Goin-Kochel RP, Berry LN, Ali M, Ge J, Guffey D, Rosenfeld JA, Bader P, Gambello MJ, Wolf V, et al. The complex behavioral phenotype of 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome. Genet Med. 2016;18(11):1111–1118. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fejgin K, Nielsen J, Birknow MR, Bastlund JF, Nielsen V, Lauridsen JB, Stefansson H, Steinberg S, Sorensen HB, Mortensen TE, et al. A mouse model that recapitulates cardinal features of the 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome including schizophrenia- and epilepsy-related alterations. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;76(2):128–137. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yin J, Chen W, Yang H, Xue M, Schaaf CP. Chrna7 deficient mice manifest no consistent neuropsychiatric and behavioral phenotypes. Sci Rep. 2017;7:39941. doi: 10.1038/srep39941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yin J, Chen W, Chao ES, Soriano S, Wang L, Wang W, Cummock SE, Tao H, Pang K, Liu Z, et al. Otud7a knockout mice recapitulate many neurological features of 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;102(2):296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.