Significance

Are the rich less generous than the poor? Results of studies on this topic have been inconsistent. Recent research that has received widespread academic and media attention has provided evidence that higher income individuals are less generous than poorer individuals only if they reside in a US state with comparatively large economic inequality. However, in large representative datasets from the United States (study 1), Germany (study 2), and 30 countries (study 3), we did not find any evidence for such an effect. Instead, our results suggest that the rich are not less generous than the poor, even when economic inequality is large. This result has implications for contemporary debates on what increasing inequality in resource distributions means for modern societies.

Keywords: social class, income, economic inequality, prosocial behavior, generosity

Abstract

A landmark study published in PNAS [Côté S, House J, Willer R (2015) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:15838–15843] showed that higher income individuals are less generous than poorer individuals only if they reside in a US state with comparatively large economic inequality. This finding might serve to reconcile inconsistent findings on the effect of social class on generosity by highlighting the moderating role of economic inequality. On the basis of the importance of replicating a major finding before readily accepting it as evidence, we analyzed the effect of the interaction between income and inequality on generosity in three large representative datasets. We analyzed the donating behavior of 27,714 US households (study 1), the generosity of 1,334 German individuals in an economic game (study 2), and volunteering to participate in charitable activities in 30,985 participants from 30 countries (study 3). We found no evidence for the postulated moderation effect in any study. This result is especially remarkable because (i) our samples were very large, leading to high power to detect effects that exist, and (ii) the cross-country analysis employed in study 3 led to much greater variability in economic inequality. These findings indicate that the moderation effect might be rather specific and cannot be easily generalized. Consequently, economic inequality might not be a plausible explanation for the heterogeneous results on the effect of social class on prosociality.

Economic inequality has been on the rise around the world for several decades (1, 2), and researchers from several disciplines have investigated the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of this increasing economic divide (3–5). Mostly negative effects have been reported, and not only in the economic domain but also including increases in health and social problems [e.g., increased drug use, higher obesity, more violent crimes, higher imprisonment rates, lower interpersonal trust (6, 7)], ultimately leading to lower levels of life satisfaction in the population (8–10) (but see refs. 11–13 for positive and null effects of inequality on well-being and happiness).

An additional negative consequence was recently reported in PNAS, where Côté et al. (14) provided evidence that economic inequality leads higher income individuals to be less generous than low-income individuals. Their study is important for several reasons: (i) It has policy implications because the negative effects of economic inequality on outcomes that are desirable for a society are important issues for the public, (ii) it shows how a macroeconomic variable measured on the state level (economic inequality) can interact with a sociological variable (social class) to affect a psychological variable (prosocial behavior), and (iii) it has the potential to reconcile the debate on why findings on the association between social class and prosocial behavior have been inconsistent.

This debate began with two influential psychological studies in which Piff et al. (15, 16) reported that individuals from higher social classes behaved more unethically and were less charitable, less trusting, and less generous than individuals from a lower social class. The authors explained this negative effect of social class from a social-cognitive perspective (17): Individuals from lower social classes are more attuned to the welfare of others as a way to adapt to their more hostile environments, and are thus more likely to be compassionate (18) and to engage in other beneficial prosocial behavior (15). On the other end of the continuum, the abundant resources enjoyed by upper-class individuals lead to an individualistic focus on their own internal states, goals, motivations, and emotions (15, 16, 18, 19; recently reviewed in refs. 17, 20, 21).

However, other researchers from various disciplines have not been able to confirm the negative effects of higher social class on prosocial behaviors and observed either no associations or even effects in the opposite direction. Such research has employed a large number of diverse behaviors as indicators of prosociality, such as making charitable donations (22, 23), volunteering (23–25), behaving prosocially in economic games (23, 25, 26), returning lost letters (27, 28), helping others (23), and being compassionate and empathetic (29). This research also includes two failed but high-powered direct replications of studies reported by Piff et al. (16) on the effect of social class on unethical activities (30, 31).

What might explain the discrepant results? Piff and Robinson (20) argued that moderating variables might be responsible for the heterogeneous effects of social class on prosociality, thus qualifying the “having less, giving more” main effect reported by Piff et al. (15). Indeed, Côté et al. (14) identified such a moderator when they found that the negative effect of social class on prosociality could be observed only when economic inequality was high. By contrast, when economic inequality was low, social class and prosocial behavior were even positively related, whereas they found no effects when all participants were considered together. Specifically, higher income individuals were less generous in an economic game than poorer individuals only when they resided in a US state that was plagued by comparatively large economic inequality (study 1) or only when a perception of high inequality was induced experimentally (study 2). Different levels of economic inequality may thus explain why individuals from a lower social class were more generous in the US sample (a country with comparatively high inequality) of Piff at al. (15), whereas we (23) found the opposite effect in a German sample (a country with lower inequality). The explanation for this moderating effect is that in less equal environments, higher income individuals perceive a wider gap between themselves and low-income individuals, which leads higher income individuals to have a sense of entitlement and ultimately reduces their prosocial behavior (14, 20).

In sum, the “inequality as a moderator of the relation between social class and prosociality” explanation seems to be theoretically compelling and empirically sound. However, can one article comprising two studies really provide a definitive answer and resolve the debate on the effects of social class on prosocial behavior? Certainly not. A few conceptually related recent studies might be interpreted as additional evidence in support of the central claim of Côté et al. (14). From 1917 to 2012, higher income individuals in the United States donated less in years when inequality was high than in years when inequality was low (32). In the laboratory, individuals with more resources in a public goods game acted more selfishly when resources were markedly unequal than when resources were more equally distributed (33), at least as long as resource inequality was visible to the participants (34). Finally, passersby in a wealthy area supported a “millionaire tax” less often in the presence of a homeless person (a signal of inequality) than in the presence of a professional-looking person (35).

At the same time, other conceptually related findings might be interpreted as evidence against the claim of Côté et al. (14). First, experimentally inducing a tendency to accept and endorse inequalities in society moderated the relation between individual power and charitable giving, but in exactly the opposite direction than what would be expected from the previously described studies. When instructed to provide reasons in support of societal inequality, individuals high in power donated more, whereas when instructed to provide reasons against societal inequality, those low in power behaved more generously (36). Second, not only did millionaires give more in economic games than any other group studied in the literature before but they were also more generous toward individuals with lower incomes in a setting with high inequality (dictator game: the other participant could not punish unfair behavior) compared with a more equal setting (ultimatum game: the other participant could punish unfair behavior) (37). Third, in a natural experiment in Indian schools, integrating poor students into elite private schools, and thus making economic inequality salient, led students from affluent families to be more prosocial, generous, and egalitarian (38).

In view of this inconclusive current state of studies and recent evidence for a rather low rate of successful replications in psychology (39), the issues of reproducibility and replicability are major issues not only in psychology but in science in general (40). For instance, the National Academy of Sciences organized a colloquium on this issue (41) and initiated a committee on reproducibility and replicability in December 2017 (42). We support the idea that replications should become the norm rather than the exception before new findings are readily accepted, even when such findings appear to be plausible and desirable (43, 44). As the importance of a study increases, it is even more essential to confirm the reproducibility and replicability of that research, and importance might be defined through a study’s theoretical weight, societal implications, influence through citations, or mass appeal (45). As argued above, all these descriptors of importance are fulfilled for the association between social class and prosociality in general and especially for the potential moderating effect of economic inequality. For these reasons, we sought to test whether we would be able to find this Income × Inequality interaction in three large datasets that we analyzed previously regarding the effects of social class on prosocial behavior (23). Data and analysis scripts are provided at https://osf.io/b6m2r/.

Study 1

In study 1, we tried to replicate the Income × Inequality interaction in a large and reasonably representative US sample, the American Consumer Expenditure Survey (CEX) (46). In this survey, households from 41 US states were asked about their yearly household income and the amount of charitable contributions they made during the last 3 mo in four quarterly interviews across a year. We used CEX data collected between 2005 and 2012. By using different inclusion criteria, we created two samples for our main analysis: For sample A, we included only households that participated in all four interviews within a given year and for which all variables relevant for our analyses were available (n = 27,714). This inclusion criterion maximized data quality at the expense of excluding many households. For sample B, we relaxed the demands on data quality to maximize sample size and included households that participated in at least two of the four interviews (n = 43,739). If necessary, the yearly amount of donations was extrapolated from the available information (more information about the CEX data and our samples is provided in SI Appendix, Supplementary Information Text).

The mean after-tax household incomes were $68,204 (SD = 61,822) and $65,188 (SD = 61,859) in samples A and B, respectively. Because the distribution of the income variable was skewed (skewness of 2.35 and 2.50), with more household incomes below the mean and some households with very large incomes (medians of $50,817 and $47,499), we logarithmized the income variable. On average, 0.39% and 0.35% of a household’s after-tax income was donated, and 55.32% and 61.94% of households reported donating nothing during the year. Households that reported donating more than 100% of their yearly income were removed from the main analyses (eight and 12 households).

As a measure of economic inequality between states, we used Gini coefficients, which range from 0 (perfect equality) to 1 (maximal inequality). We retrieved 5-y Gini coefficients from the American Community Survey (47) for the year 2012. Gini coefficients were based on the pretax household income and varied from 0.413 (Alaska) to 0.532 (District of Columbia) between states (mean = 0.457, SD = 0.022). An overview of the states included in our analysis, along with the corresponding sample size and the Gini coefficients, is provided in SI Appendix, Table S1.

In our main analysis, we estimated a multilevel Tobit model that adequately dealt with both the nested structure of our data (participants were nested in states) and the zero inflation in the donation variable (more than 50% of households reported donating nothing during the year). In this model, the amount of donations (as percentage of income) was predicted by logarithmized household income, state-level inequality (Gini coefficients), and the cross-level interaction of these two variables. Analogous to the study of Côté et al. (14), income was grand mean-centered, Gini coefficients were centered across states, and covariation was allowed between random slopes and random intercepts.*

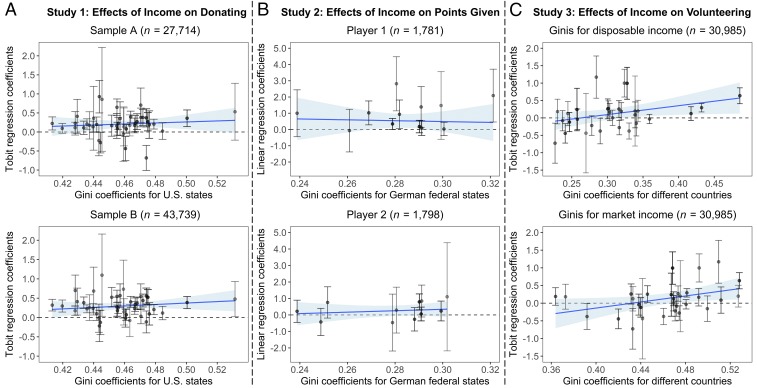

The results for sample A (n = 27,714) and sample B (n = 43,739) are presented in Table 1. Most importantly, the interaction between income and inequality was not significant in either sample (b = −3.40, P = 0.31; b = −4.28, P = 0.14). Instead, we observed a significant positive main effect of household income on donations (b = 0.40, P < 0.001; b = 0.49, P < 0.001) but no main effect of state-level inequality. In addition, we computed the effect of income on the amount of donations separately for each of the 41 states. Fig. 1A illustrates this result. The effect of income indeed varied substantially between states, but the size of this effect was not related to state-level inequality (Gini indices), reflecting the nonsignificant interaction in our analyses.

Table 1.

Study 1: Results of the multilevel Tobit model predicting amount donated to charity in percentage of household income (American CEX)

| Sample A | Sample B | |||

| Variable | b | P | b | P |

| Intercept | −1.59 | <0.001 | −2.09 | <0.001 |

| Household income | 0.40 | <0.001 | 0.49 | <0.001 |

| State-level inequality | −4.77 | 0.226 | −5.43 | 0.169 |

| Income × Inequality | −3.40 | 0.308 | −4.28 | 0.143 |

Households are nested in 41 US states (including the District of Columbia). Household income was logarithmized and grand mean-centered; state-level inequality (Gini index) was centered across states. Sample A includes only households with complete data (n = 27,714), and sample B includes all households that participated in at least two of the four interviews (n = 43,739). SEs and z values are provided in SI Appendix, Table S2.

Fig. 1.

Association between generous behavior and income in each of the states (or countries) for each of our analyses. Single dots display, separately for each state, the regression coefficients when predicting generous behavior [study 1 (A): amount of donations in percentage of income; study 2 (B): points transferred to another player in an economic game; study 3 (C): volunteering to participate in charitable activities] by logarithmized household income (for study 2, states with fewer than 10 observations were not included in the figure). Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval for each of these state-specific regression coefficients. The blue line displays the linear association between state-level economic inequality (Gini coefficients) and the state-specific regression coefficients (weighted by sample size), with the light blue area showing the SE for this association. The figure shows that the association between generous behavior and income does not become negative with increasing state-level income inequality as suggested by Côté et al. (14). Instead, we found neither an increase nor a decrease in regression coefficients in studies 1 and 2 and even an increase in study 3. This reflects the nonsignificant interaction effects in studies 1 and 2 and the significant positive interaction effect in study 3 (results are provided in Tables 1–3).

We also conducted several robustness analyses. First, we specified a model that was identical to the one used by Côté et al. (14), that is, a linear mixed model with nonlogarithmized income. Second, we used a logistic multilevel model with no donating versus donating as the dependent variable. Third, we analyzed two additional samples with other inclusion criteria. Fourth, we used year-specific Gini coefficients to consider differences in economic inequality across years in which households were interviewed. Fifth, we conducted analyses that included households with donations that exceeded 100% of their yearly income. However, in none of these robustness analyses was the interaction between inequality and income on percentage of donations significant (results are provided in SI Appendix, Tables S3–S7).

To summarize, we did not find the postulated interaction between household income and state-level inequality on generosity in any of our analyses, although our sample sizes (n = 27,714 and n = 43,739) were 18- and 29-fold larger, respectively, than the sample size (n = 1,498) of Côté et al. (14). One could argue, however, that the CEX dataset included households from only 41 US states, whereas Côté et al. (14) analyzed participants from all 51 states (from n = 2 to n = 166 participants from each state; SI Appendix, Table S1) and that, for this reason, the power of our analysis to detect the cross-level interaction might actually not have been higher than that in the study by Côté et al. (14) despite our much larger sample size. For this reason, we conducted a Monte Carlo power analysis with 1,000 simulations to estimate the power to detect the cross-level interaction reported in study 1 of Côté et al. (14) at an alpha level of 0.05 (the code for the power analysis is provided at https://osf.io/b6m2r/ and explained in detail in SI Appendix, Supplementary Information Text). The simulations showed that even for our smaller sample A, the statistical power was above 99.9% (in 1,000 simulations, there was not even one simulation in which the cross-level interaction was not significant), demonstrating that our statistical power was indeed more than sufficient and that we could safely conclude from the null finding that there was indeed no interaction effect in our study.

Study 2

Nevertheless, because the real-life generous behavior in study 1 was not directly observed but was instead self-reported, such reports have the potential to be biased by self-presentation strategies, and higher income individuals may be particularly affected by such strategies. Thus, in study 2, we attempted to replicate the postulated Income × Inequality interaction with data from the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) (49), a nationally representative longitudinal survey of private households in Germany (50). In 2003–2005, a randomly selected subsample was asked to play an economic game that was similar to the one used by Côté et al. (14) in that participants could behave generously by giving money to another player. We had information on behavior in the economic game and income for 1,334 participants (678 women), with a mean age of 49.3 y (SD = 17.2) and a mean household income of 33,395€ (SD = 18,118, median = 30,392€; more information is provided in SI Appendix, Supplementary Information Text).

In the economic game, participants were assigned the role of either player 1 or player 2 (667 participants each). Both players received 10 points as seed capital and could either keep these points for themselves or fully or partially allocate them to the other player. For nontransferred points, players earned 1€, and for received points, they earned 2€. Because player 2’s decision was made after being told how many points player 1 transferred to him or her, we controlled for the number of points sent by player 1 when we analyzed player 2. Please note that player 2 was not allowed to send back the points received from player 1 (i.e., both players could send between 0 and 10 points). Participants had the opportunity to play the game three times in the years 2003–2005.

Similar to the United States, Germany is divided into several federal states (totaling 16). As a state measure of economic inequality, we retrieved the 2005 Gini coefficients from the German Federal Statistical Office (51). The Gini coefficients were based on posttax household income and ranged from 0.24 (Saxonia) to 0.32 (Hamburg) (mean = 0.281, SD = 0.022).

We estimated two linear multilevel models (one for player 1 and one for player 2) with three levels (observations nested in participants nested in states) predicting the amount given in the economic game by logarithmized household income, state-level inequality (Gini coefficients), and the cross-level interaction of these two variables. The results for the model are presented in Table 2. Most importantly, the interaction between income and inequality was not significant for player 1 (b = 7.73, P = 0.53) or for player 2 (b = 1.03, P = 0.88). Instead, similar to study 1, we observed an at least marginally significant positive main effect of household income (player 1: b = 0.57, P = 0.005; player 2: b = 0.27, P = 0.063) but no robust main effect of state-level inequality. Fig. 1B shows the effect of income on the transferred points separately for each of the German federal states. The size of this effect was not related to the state-level economic inequality (Gini coefficients) for either player.

Table 2.

Study 2: Results of the multilevel linear model predicting number of points given to another player in the economic game (German Socio-Economic Panel)

| Player 1 | Player 2 | |||

| Variable | b | P | b | P |

| Intercept | 5.07 | <0.001 | 4.84 | <0.001 |

| Household income | 0.57 | 0.005 | 0.27 | 0.063 |

| State-level inequality | 10.36 | 0.081 | 1.08 | 0.850 |

| Income × Inequality | 7.73 | 0.526 | 1.03 | 0.879 |

| Year | ||||

| 2004 | 0.31 | 0.006 | −0.04 | 0.735 |

| 2005 | 0.56 | <0.001 | 0.09 | 0.445 |

| Received by player 1 | 0.39 | <0.001 | ||

Model for player 1: 1,781 observations of n = 667 participants, nested in 14 federal German states. Model for player 2: 1,798 observations of n = 667 participants, nested in 13 federal German states. Logarithmized household income and points received by player 1 were grand mean-centered; state-level inequality (Gini index) was centered across states, and the year was dummy-coded with 2003 as the reference year. SEs and z values are provided in SI Appendix, Table S8.

For a better comparison with the analyses provided by Côté et al. (14), we also analyzed our model with nonlogarithmized household income. Again, the interaction between income and inequality was not significant for player 1 or for player 2. Results for this analysis are presented in SI Appendix, Table S9.

As in study 1, we estimated the statistical power for finding a significant interaction using Monte Carlo simulations based on the effects reported by Côté et al. (14). However, we were not able to conduct a direct power simulation for the three-level mixed model on the basis of the effects reported by Côté et al. (14) because those data had a two-level structure. Therefore, we conducted two different two-level power analyses to estimate the power of our study 2. As a lower bound estimate, we computed the power for our study assuming that every participant was assessed only once instead of up to three times, which obviously strongly underestimated the true power. As an upper bound estimate, we computed the power under the assumption that all of our observations were independent (more information on the power analyses is provided in SI Appendix, Supplementary Information Text). Because both the overall number of participants and the number of states were smaller than in study 1, the statistical power of study 2 was also substantially lower, with power estimated to lie between 65.2% and 87.4% for the analysis of player 1 and between 63.6% and 81.8% for the analysis of player 2. Nevertheless, our results are still indicative of a null effect for the Income × Inequality interaction because we did not observe a significant interaction for either of the two players, and because the combined statistical power to find a significant effect in at least one of the two analyses was between 86.9% and 98.6%.

It should be noted that the average state-level Gini coefficient was substantially lower in Germany (mean = 0.281 in our study 2) than in the United States [mean = 0.459; value taken from study 1 of Côté et al. (14)]. However, these state-level Gini coefficients between the United States and Germany are not directly comparable because they are based on pretax or posttax income, respectively. On a country level, Gini estimates calculated in a comparative fashion are provided by the Standardized World Income Inequality Database (SWIID) (52) and suggest that the difference between the United States and Germany in economic inequality is actually much smaller. Gini estimates based on pretax, pretransfer market income are not different at all between the United States and Germany (0.495 for the United States and 0.511 for Germany), and only when estimates are based on posttax, posttransfer disposable income is inequality somewhat lower in Germany (0.370 for the United States and 0.284 for Germany; all estimates are for 2005). Most important for our analysis, however, variability in the Gini coefficients was similar between German federal states in our study 2 (SD = 0.0217) and between US states in the original study by Côté et al. (SD = 0.0224) (14), showing that both studies suffered from relatively low heterogeneity in income inequality. Thus, for our next study, we decided to analyze data from different countries rather than from different states in one country so that we could test for the interaction in data with much greater variability in inequality, including countries with Gini coefficients lower than in Germany and higher than in the United States.

Study 3

For this aim, in study 3, we analyzed data from the International Social Survey Program (ISSP) (53), which annually collects representative data for different countries from all over the world. In 1998, the ISSP survey contained a question about how often participants volunteered to participate in charitable activities in the past 12 mo. Overall, 73.79% reported that they did not volunteer to participate in charitable activities; 13.35% indicated yes, once or twice; 5.04% indicated yes, three to five times; and 7.82% indicated yes, six or more times. In total, we had information on volunteering and household income for 30,985 participants from 30 countries (16,366 women; mean age = 45.22 y, SD = 16.72; more information is provided in SI Appendix, Supplementary Information Text).

To measure country-level income inequality, we used Gini estimates from the SWIID (51) for 1998. Based on the disposable income, Gini estimates varied from 0.227 (Denmark) to 0.486 (Chile), and variability was much larger than in the other studies (mean = 0.309, SD = 0.060). For market income, Gini estimates varied from 0.364 (Bulgaria) to 0.528 (Chile) (mean = 0.461, SD = 0.040). Given the large heterogeneity in income inequality across countries and the large sample size, it is not surprising that we had an extremely high statistical power of above 99.9% to find an effect of the size reported by Côté et al. (14).

In our main analysis, we estimated a multilevel Tobit model that adequately dealt with the zero inflation in the volunteering variable (more than 70% of the participants reported that they did not volunteer). In this analysis, participants were nested in countries, and the amount of volunteering was predicted by logarithmized household income (standardized per country to account for the different currencies), country-level inequality (Gini coefficients), and the cross-level interaction of these two variables. The results are presented in Table 3. The analyses showed a significantly positive interaction between income and inequality both for Gini estimates based on disposable income (b = 1.82, P = 0.004) and for Gini estimates based on market income (b = 2.26, P = 0.028). Fig. 1C illustrates this interaction by showing that in countries with greater economic inequality, the effect of income on volunteering was more positive (the wealthier volunteered more) than in countries that had greater equality. Thus, the direction of the interaction was opposite the effect postulated by Côté et al. (14). In addition to the interaction effect, we found marginally significant general positive effects of income and no main effects of economic inequality.

Table 3.

Study 3: Results of the multilevel Tobit model predicting volunteering to participate in charitable activities (ISSP)

| Disposable income inequality | Market income inequality | |||

| Variable | b | P | b | P |

| Intercept | −1.57 | <0.001 | −1.57 | <0.001 |

| Household income | 0.07 | 0.063 | 0.07 | 0.076 |

| Country-level inequality | 2.58 | 0.328 | 0.65 | 0.871 |

| Income × Inequality | 1.82 | 0.004 | 2.26 | 0.028 |

n = 30,985 participants, nested in 30 countries. Logarithmized household income was standardized for each country to account for the different currencies, and country-level inequality (Gini index) was centered across countries. Disposable income = posttax, posttransfer income; market income = pretax, pretransfer income. SEs and z values are provided in SI Appendix, Table S10.

For a better comparison with the analyses provided by Côté et al. (14), we also analyzed hierarchical linear models with nonlogarithmized household income. Finally, we computed a multilevel logistic regression in addition to our main analysis, with the dichotomous answer “volunteering” versus “no volunteering” as the dependent variable. Again, the interaction between income and inequality was positive in all of these analyses (SI Appendix, Tables S11 and S12).

Discussion

In two studies involving US samples, Côté et al. (14) reported evidence that only under high economic inequality were higher income individuals less generous in an economic game than lower income individuals. We were not able to find this moderation effect (i) in a similar, but about 20-fold larger, US sample with donating behavior as a real-life measure of generosity; (ii) for a similar behavioral measure of generosity in a German sample; and (iii) in a large-scale cross-country analysis of generosity with much greater variability in economic inequality. We were able to rule out the possibility that low statistical power might have caused these null effects. Indeed, the statistical power was extremely high (>99.9%) in studies 1 and 3 and at least sufficient (>80%) in study 2. Furthermore, in study 3, we even found a significant interaction effect in the direction opposite the one postulated by Côté et al. (14). Besides this central result of our study, we also did not find any evidence for negative main effects of high economic inequality or high income on any of our measures of generosity. Instead, the results even suggested a positive effect of income on generosity in many of our analyses, confirming our previous analyses with the same datasets (23).

There are multiple possible and not necessarily mutually exclusive explanations for why we failed to detect the interaction reported by Côté et al. (14). One explanation might be that our measures were not comparable to those used by Côté et al. (14) and might not have measured generosity. According to the Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley, however, generosity is defined as the “virtue of giving good things to others freely and abundantly . . . money, possessions, time, attention, aid, encouragement” (ref. 54, p. 8) and charitable giving and volunteering (the dependent variables in our studies 1 and 3) are explicitly mentioned as “generally recognized forms of generosity” (ref. 54, p. 8). Côté et al. (14) also used such a broad definition of generosity and explicitly referred to behaviors such as donating, volunteering, and not behaving unethically in their article. In fact, they aimed to explain the discrepancy in the effects of social class between the studies of Piff et al. (15) and Korndörfer et al. (23) by introducing inequality as a moderator. Because we used the same datasets and dependent variables as Korndörfer et al. (23), the dependent variables in our analyses can be concluded to meet the definition of generosity used by Côté et al. (14).

Second, Côté et al. (14) observed the interaction in both an observational study and an experimental study, and we failed to replicate only the observational part. Thus, the experimental effect could still be replicable. For purposes of illustration, imagine a scenario in which the experimental effect was reproducible but the observational effect was not. In this case, an evident explanation would be that experimentally manipulating income inequality by showing bogus pie charts to Amazon Mechanical Turkers (of which 28.5% did not pass the comprehension checks for the inequality manipulation) is simply not equivalent to living in a more or less unequal state; that is, it is a likely explanation that the experimental manipulation lacks external validity.

A third potential explanation for the discrepant results is that Côté et al. (14) analyzed differences in economic inequality only between US states and that these are rather small in comparison to differences between countries. A priori, however, it should be easier to find inequality effects in data from multiple countries, which show larger variance in economic inequality, than in data from only the United States. Nevertheless, we did not find any evidence for an effect of the interaction between economic inequality and income on generosity in either intercountry or US data.

Thus, at a minimum, our findings indicate that the moderation effect identified by Côté et al. (14), as interesting and plausible as it seems, might be rather specific and cannot be easily generalized to different samples or to other measures of generosity. Consequently, economic inequality might not be a plausible explanation for the heterogeneous results on the effect of social class on prosocial and unethical behaviors as previously suggested (20; publication bias of low-powered studies as an alternative explanation is discussed in ref. 55). A further argument against the inequality as a moderator explanation is that the original studies showing the negative effect of higher social class published by Piff et al. (15) were conducted in California with a Gini index of 0.475, but Côté et al. (14) did not observe any effects of income on generosity in states with this level of economic inequality, and thus failed to replicate the findings of Piff et al. (15): “The association between income and generosity was significantly negative in states with Ginis of 0.485 or higher. By contrast, the association between income and generosity was significantly positive in states with Ginis of 0.454 or lower” (ref. 14, p. 15839). We also analyzed the effect of income on generosity for participants from California (n = 166) with the data used by Côté et al. (14) and found no significant effect (b = −0.03, P = 0.13).

To conclude, we were not able to replicate the previously published finding that economic inequality moderates the effect of income on generosity (14). In three studies comprising large and reasonably representative datasets from different countries, we did not find any evidence for the interactive effect of individual income and state- or country-level inequality on diverse outcomes of generosity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Julia Rohrer for comments on this paper and for helping to create the figure. The data from the CEX were made available to us by the American Bureau of Labor Statistics, the data from the SOEP were made available to us by the German Institute for Economic Research, and the data from the ISSP were made available to us by the GESIS Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences. We thank these institutions for providing these datasets. However, these institutions bear no responsibility for our analysis or interpretation of these data.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. R.L. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Data deposition: The data used in our studies 1 and 3, and the scripts for replicating our data analyses for all studies are archived in the Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/b6m2r/. The data used in our study 2 are deposited in the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) archive at www.diw.de/soep-re-analysis and may be obtained after signing a data distribution contract (soepmail@diw.de).

*We grand mean-centered income to test the same statistical hypothesis as Côté et al. (14), that is, the interaction of grand-mean–centered income and across-states–centered Gini indices. However, grand-mean–centered income might be problematic because it includes (i) differences in income between persons within states and (ii) differences in average income between states. In our view, to investigate the hypothesis of whether effects of income on generosity observed within states differ between states with different levels of inequality, it would be more accurate to test the pure cross-level interaction of within-states–centered household income and across-states–centered Gini indices (see ref. 48). We report results for such an analysis in SI Appendix, Table S13 (study 1) and SI Appendix, Table S14 (study 2). Results were not substantially different, however, because income varies much more within states than between states, thus minimizing the differences between the two analyses. For study 3, this methodological issue did not matter because we standardized income within countries to account for different currencies.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1807942116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development . Divided We Stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising. OECD Publishing; Paris: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piketty T, Saez E. Inequality in the long run. Science. 2014;344:838–843. doi: 10.1126/science.1251936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piketty T. Capital in the 21st Century. Harvard Univ Press; Cambridge, MA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stiglitz JE. The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future. Norton; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilkinson RG, Pickett KE. The Spirit Level: Why Equality Is Better for Everyone. Bloomsbury; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pickett KE, Wilkinson RG. Income inequality and health: A causal review. Soc Sci Med. 2015;128:316–326. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkinson RG, Pickett KE. Income inequality and social dysfunction. Annu Rev Sociol. 2009;35:493–511. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buttrick NR, Oishi S. The psychological consequences of income inequality. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2017;11:e12304. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheung F, Lucas RE. Income inequality is associated with stronger social comparison effects: The effect of relative income on life satisfaction. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2016;110:332–341. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oishi S, Kesebir S, Diener E. Income inequality and happiness. Psychol Sci. 2011;22:1095–1100. doi: 10.1177/0956797611417262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider SM. Income inequality and subjective wellbeing: Trends, challenges, and research directions. J Happiness Stud. 2016;17:1719–1739. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelley J, Evans MDR. Societal inequality and individual subjective well-being: Results from 68 societies and over 200,000 individuals, 1981-2008. Soc Sci Res. 2017;62:1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2016.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheung F. Can income inequality be associated with positive outcomes? Hope mediates the positive inequality-happiness link in rural China. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 2016;7:320–330. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Côté S, House J, Willer R. High economic inequality leads higher-income individuals to be less generous. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:15838–15843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511536112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piff PK, Kraus MW, Côté S, Cheng BH, Keltner D. Having less, giving more: The influence of social class on prosocial behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;99:771–784. doi: 10.1037/a0020092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piff PK, Stancato DM, Côté S, Mendoza-Denton R, Keltner D. Higher social class predicts increased unethical behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:4086–4091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118373109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kraus MW, Piff PK, Mendoza-Denton R, Rheinschmidt ML, Keltner D. Social class, solipsism, and contextualism: How the rich are different from the poor. Psychol Rev. 2012;119:546–572. doi: 10.1037/a0028756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stellar JE, Manzo VM, Kraus MW, Keltner D. Class and compassion: Socioeconomic factors predict responses to suffering. Emotion. 2012;12:449–459. doi: 10.1037/a0026508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Doesum NJ, Tybur JM, van Lange PA. Class impressions: Higher social class elicits lower prosociality. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2017;68:11–20. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piff PK, Robinson AR. Social class and prosocial behavior: Current evidence, caveats, and questions. Curr Opin Psychol. 2017;18:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piff PK, Kraus MW, Keltner D. Unpacking the inequality paradox: The psychological roots of inequality and social class. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2018;57:53–124. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gittell R, Tebaldi E. Charitable giving: Factors influencing giving in U.S. states. Nonprofit Volunt Sector Q. 2006;35:721–736. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korndörfer M, Egloff B, Schmukle SC. A large scale test of the effect of social class on prosocial behavior. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0133193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramirez-Valles J. Volunteering in public health: An analysis of volunteers’ characteristics and activities. Int J Volunt Adm. 2006;24:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trautmann ST, van de Kuilen G, Zeckhauser RJ. Social class and (un)ethical behavior: A framework, with evidence from a large population sample. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2013;8:487–497. doi: 10.1177/1745691613491272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fehr D, Rau H, Trautmann ST, Xu Y. 2018. Inequality, Fairness and Social Capital (Department of Economics, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg), Discussion Paper Series No. 650.

- 27.Holland J, Silva AS, Mace R. Lost letter measure of variation in altruistic behaviour in 20 neighbourhoods. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andreoni J, Nikiforakis N, Stoop J. 2017 Are the rich more selfish than the poor, or do they just have more money? A natural field experiment (National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA). Available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w23229. Accessed April 12, 2019.

- 29.Greitemeyer T, Sagioglou C. Does low (vs. high) subjective socioeconomic status increase both prosociality and aggression? Soc Psychol. 2018;49:76–87. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balakrishnan A, Palma PA, Patenaude J, Campbell L. A 4-study replication of the moderating effects of greed on socioeconomic status and unethical behaviour. Sci Data. 2017;4:160120. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clerke AS, Brown M, Forchuk C, Campbell L. Association between social class, greed, and unethical behaviour: A replication study. Collabra Psychol. 2018;4:35. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duquette NJ. Inequality and philanthropy: High-income giving in the United States 1917–2012. Explor Econ Hist. 2018;70:25–41. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hargreaves Heap SP, Ramalingam A, Stoddard BV. Endowment inequality in public goods games: A re-examination. Econ Lett. 2016;146:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishi A, Shirado H, Rand DG, Christakis NA. Inequality and visibility of wealth in experimental social networks. Nature. 2015;526:426–429. doi: 10.1038/nature15392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sands ML. Exposure to inequality affects support for redistribution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:663–668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1615010113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han D, Lalwani AK, Duhachek A. Power distance belief, power, and charitable giving. J Consum Res. 2017;44:182–195. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smeets P, Bauer R, Gneezy U. Giving behavior of millionaires. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:10641–10644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507949112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rao G. Familiarity does not breed contempt: Generosity, discrimination, and diversity in Delhi schools. Am Econ Rev. 2019;109:774–809. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Open Science Collaboration PSYCHOLOGY. Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science. 2015;349:aac4716. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Munafò MR, et al. A manifesto for reproducible science. Nat Hum Behav. 2017;1:0021. doi: 10.1038/s41562-016-0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allison DB, Shiffrin RM, Stodden V. Reproducibility of research: Issues and proposed remedies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:2561–2562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1802324115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Academy of Science 2018 Committee on Reproducibility and Replicability in Science. Available at sites.nationalacademies.org/DBASSE/BBCSS/%20Reproducibility_and_Replicability_in_Science/index.htm. Accessed April 2, 2019.

- 43.Zwaan RA, Etz A, Lucas RE, Donnellan MB. Making replication mainstream. Behav Brain Sci. 2018;41:E120. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X17001972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Egloff B. To make innovations such as replication mainstream, publish them in mainstream journals. Behav Brain Sci. 2018;41:E126. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X18000614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giner-Sorolla R, Amodio DM, van Kleef GA. Three strong moves to improve research and replications alike. Behav Brain Sci. 2018;41:E130. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X18000651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.US Bureau of Labor Statistics 2013 Consumer Expenditure Surveys. Public-Use Microdata 2005-2012. Available at https://www.bls.gov/cex/. Accessed November 13, 2013.

- 47.US Census Bureau 2015 American Community Survey. Gini index estimates (Table B19083). Available at factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml. Accessed August 15, 2018.

- 48.Enders CK, Tofighi D. Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychol Methods. 2007;12:121–138. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.German Institute for Economic Research [Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung] 2013. Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP): Data for Years 1984-2012 (DIW/SOEP, Berlin), Version 29.

- 50.Wagner G, Frick J, Schupp J. The German Socio-Economic Panel study (SOEP): Scope, evolution and enhancements. J Appl Soc Sci Stud. 2007;127:139–169. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Statistisches Bundesamt [Federal Statistical Office] 2015 Sozialberichterstattung der amtlichen Statistik. Gini coefficients (Table A.3). Available at http://www.amtliche-sozialberichterstattung.de/index_en.html. Accessed November 29, 2015.

- 52.Solt F. The standardized world income inequality database. Soc Sci Quart. 2016;97:1267–1281. [Google Scholar]

- 53.ISSP Research Group 2000 doi: 10.4232/1.3190. Data from “ZA3190: International Social Survey Programme: Religion II – ISSP 1998.” Version 1.0.0. GESIS Data Archive. Available at . [DOI]

- 54.Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley 2018 The Science of Generosity. Available at https://www.issuelab.org/resources/29718/29718.pdf. Accessed April 2, 2019.

- 55.Francis G. Evidence that publication bias contaminated studies relating social class and unethical behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E1587; author reply E1588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203591109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.