Significance

Human evolution through the Middle to the Late Pleistocene in East Asia has been seen as reflecting diverse groups and discontinuities vs. a continuity of form reflecting an evolving population. New Middle Pleistocene (∼300,000 y old) human remains from Hualongdong (HLD), China, provide further evidence for regional variation and the continuity of human biology through East Asian archaic humans. The HLD 6 skull is notable for its low and wide neurocranial vault and pronounced brow ridge, but less projecting face and modest chin. Along with the isolated teeth, the skull provides morphologically simple teeth with reduced or absent third molars. The remains foreshadow changes evident with modern human emergence, but primarily reinforce Old World continuity through Middle to Late Pleistocene humans.

Keywords: human paleontology, cranium, mandible, teeth, East Asia

Abstract

Middle to Late Pleistocene human evolution in East Asia has remained controversial regarding the extent of morphological continuity through archaic humans and to modern humans. Newly found ∼300,000-y-old human remains from Hualongdong (HLD), China, including a largely complete skull (HLD 6), share East Asian Middle Pleistocene (MPl) human traits of a low vault with a frontal keel (but no parietal sagittal keel or angular torus), a low and wide nasal aperture, a pronounced supraorbital torus (especially medially), a nonlevel nasal floor, and small or absent third molars. It lacks a malar incisure but has a large superior medial pterygoid tubercle. HLD 6 also exhibits a relatively flat superior face, a more vertical mandibular symphysis, a pronounced mental trigone, and simple occlusal morphology, foreshadowing modern human morphology. The HLD human fossils thus variably resemble other later MPl East Asian remains, but add to the overall variation in the sample. Their configurations, with those of other Middle and early Late Pleistocene East Asian remains, support archaic human regional continuity and provide a background to the subsequent archaic-to-modern human transition in the region.

The human remains from Zhoukoudian have dominated perceptions of Middle Pleistocene (MPl) human morphology and variation in East Asia (1–3). Subsequent discoveries of Middle and early Late Pleistocene human fossils from the region have substantially augmented later archaic human variability and trends (e.g., refs. 4–12; see ref. 13), with insights into the background and patterns of modern human emergence in the region (6, 8, 9). It has been proposed that human evolution in East Asia followed a regionally continuous, but not isolated, pattern from the Early Pleistocene through subsequent archaic humans and into the earlier Late Pleistocene, with variable degrees of continuity into early modern humans (e.g., refs. 14–19). However, given the fragmentary nature and variably reliable dating for some of the human fossils, the inference of regional continuity has remained controversial (e.g., refs. 20–22; see also discussions in refs. 14 and 23), and the degrees of cranial and dental variation have suggested substantial diversity within the region (e.g., refs. 21 and 24–26).

Additional human fossils with better preservation and more reliable dating therefore have the potential to shed further light on these concerns. In this study, we describe a recently discovered human skull and associated remains from the MPl site of Hualongdong (HLD, i.e., Hualong Cave), Anhui Province, China, in the context of MPl human remains in East Asia and more broadly.

Results

The Site of HLD.

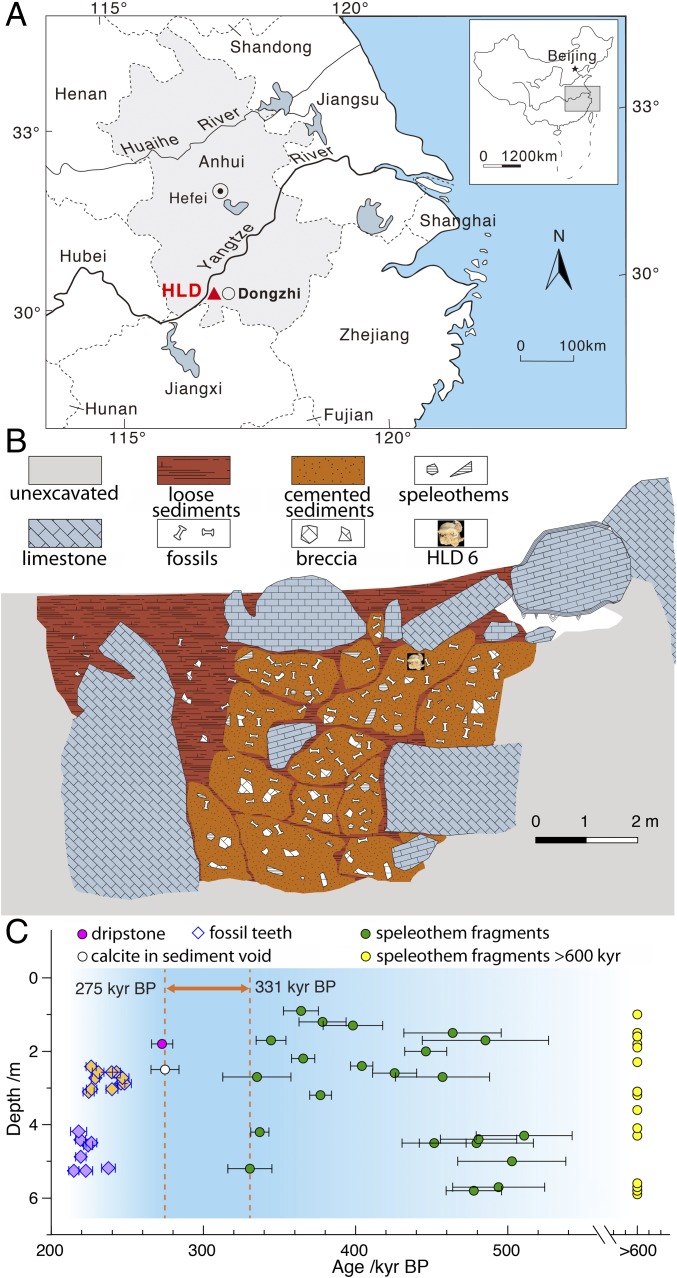

The HLD site contains two major depositional units, one of carbonate cemented cave breccia and the other of unconsolidated clay mixed with gravel (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Figs. S1–S4). Excavations in 2006 and 2014–17 yielded 16 human fossils from the brecciated deposits in association with abundant mammalian remains and a small mode 1 core and flake lithic assemblage (SI Appendix, sections 1 and 3). Forty-seven speleothem fragments from the cavern breccia provide a maximum depositional age of 330.5 ± 14.5 kyBP for the breccia and its fossil remains. A U-Th age of 274.8 ± 9.2 kyBP for a calcitic crust that formed around a void inside the cavern breccia provides a minimum age for the brecciated accumulation. An additional U-Th age of 272.8 ± 7.0 kyBP from a dripstone, likely grown on the cavern breccia, provides a similar minimum age constraint, and both are consistent with the best fit age using the iDAD model for the U-series measurements of fossil teeth (SI Appendix, section 2). These radiometric dates are supported by the faunal assemblage, in which the principal elements of the Ailuropoda–Stegodon fauna are dominant; it lacks archaic Early Pleistocene species and the later-appearing Asian elephant (27) (SI Appendix, Table S1). Therefore, HLD human fossils can be confidently dated between 275 and 331 kyBP (Fig. 1C), spanning marine isotope stages 9e to 8c.

Fig. 1.

The HLD site.(A) Location of the HLD site in Dongzhi county, Anhui province, China. (B) Longitudinal section of the deposits with in situ location of human skull. (C) Overview of U-series dating results; all ages are given with 2σ error bars. The dashed lines indicate the maximum (∼331 kyr) and minimum (∼275 kyr) age estimations of the Hualongdong breccia, respectively (SI Appendix, section 2, Figs. S9 and S10).

The HLD Human Remains.

The HLD brecciated deposits have yielded 16 human fossils, including 8 cranial elements (HLD 2, 3, 7, 8, 12, and 14), seven isolated teeth (HLD 1, 3–5, 9, 10 and 13), three femoral diaphyseal pieces (HLD 11, 15, and 16), and major portions of an adolescent skull (HLD 6; SI Appendix, Table S7). The HLD 2 frontal bone indicates a low and thick cranial vault (28), but the other cranial pieces are undiagnostic. The femoral diaphyses exhibit thick cortical bone and cross-sectional proportions within MPl ranges of variation (29–31). The HLD dental remains and especially the HLD 6 skull are presented here.

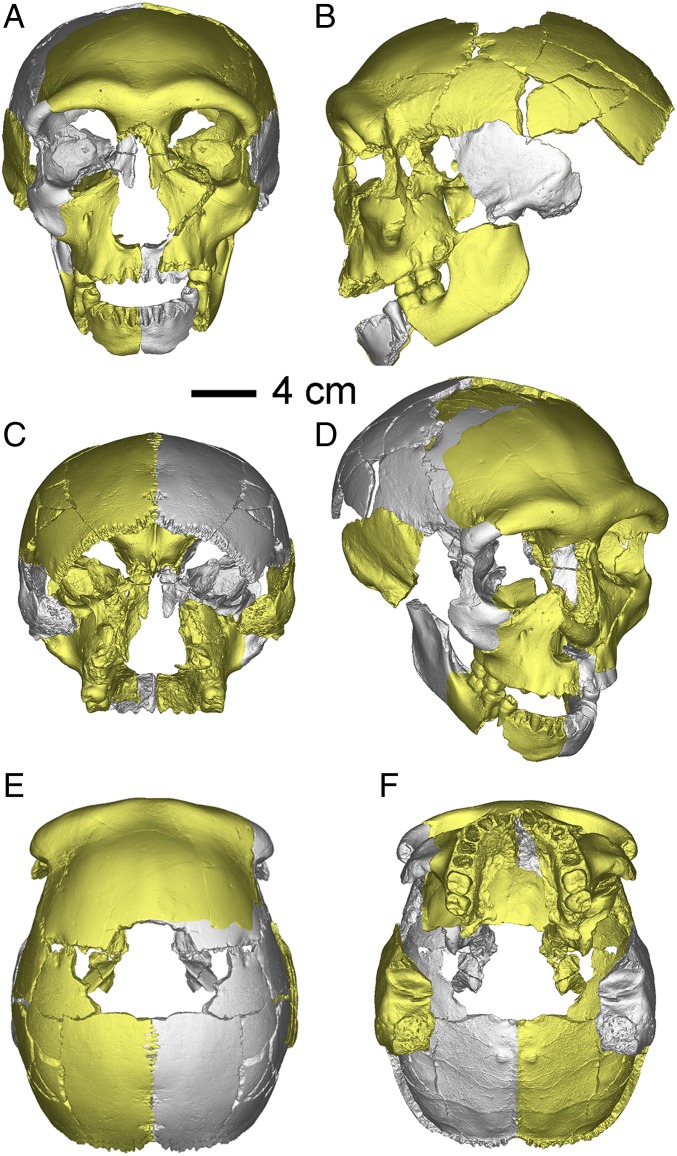

The HLD 6 cranium (Figs. 2 and 3 and SI Appendix, Figs. S2–S15) preserves 11 pieces, including most of the frontal bone, the left parietal bone, the maxillae and left zygomatic bone, a posterior temporal portion, the palatine bones, and the lateral left sphenoid. The associated mandible retains the right corpus and the posterior left corpus and ramus to the condylar neck (SI Appendix, Table S7). The elements are undistorted, and the midline is preserved for the frontal and parietal bones, maxillae, and mandibular symphysis, permitting mirror-imaging of absent portions. Midline landmarks include gnathion, infradentale, prosthion, nasion, and lambda, plus a minimally estimated bregma.

Fig. 2.

The virtually reconstructed HLD 6 skull: (A) anterior view, (B) left lateral view, (C) posterior view, (D) isometric (right lateral) view, (E) superior view, and (F) inferior view. Filled-in mirror-imaged portions are shown in gray.

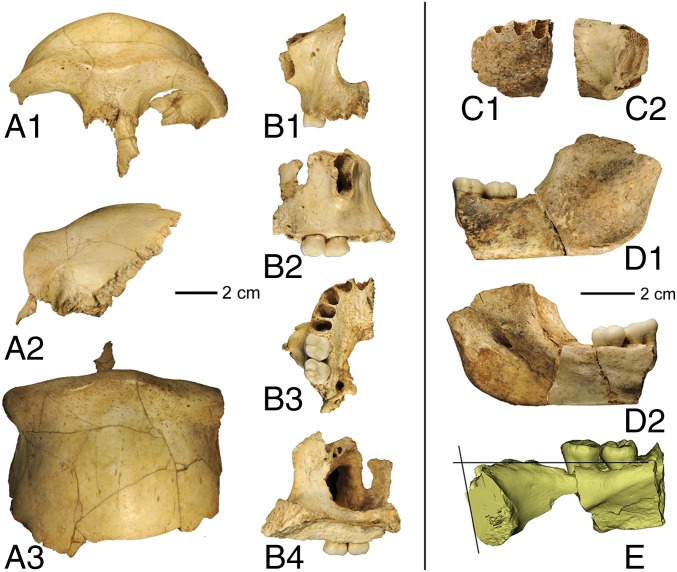

Fig. 3.

The HLD 6 frontal bone, maxilla, and mandible. (A) Frontal bone in anterior (A1), left lateral (A2), and superior (A3) views. (B) Right maxilla in anterior (B1), lateral (B2), inferior (B3), and medial (B4) views. (C–E) Mandible. (C1 and C2) Anterior and medial views of right symphyseal region from I1 to P3; (D1 and D2) external and internal views of left corpus and ramus; and (E) mandibular cross-section at the symphysis and medial view of right corpus showing the mental angle between infradentale-pogonion and the alveolar plane.

The HLD 6 dentition retains the eight M1s and M2s in occlusion, a P4, a P3 root, the developing left M3 crowns, and all alveoli on at least one side. The apically open distal M2 roots and the M3 crown stages (Cc and C3/4) provide an age at death of 13–15 y based on extant human samples (32–34) (SI Appendix, section 3).

The HLD 6 Cranium and Mandible.

The estimated endocranial capacity (∼1,150 cm3; SI Appendix, section 5) is unexceptional for its age and context [global MPl, 1,179 ± 146 cm3, n = 49; east Asia MPl (eAMPl), 1,109 ± 131 cm3, n = 18; SI Appendix, Fig. S18]. It occurs in a low neurocranial vault with an even curve from the supratoral sulcus to lambda. HLD 6 has a modest and rounded frontal keel from the supratoral sulcus to anterior of bregma, as in 88.9% eAMPl crania (SI Appendix, Table S10). The parietal bone lacks a sagittal keel, as do later but not earlier eAMPl. Its supramastoid crest ends at entomion, and hence there is no angular torus, unlike 75.0% of eAMPl. The biparietal arc is even with no angulation at the eminences and little at the sagittal suture.

The supraorbital torus is continuous across midline with an inferiorly placed glabella and even arches over the orbits, as with most eAMPl (88.9%). The torus is thickest medially, similar to Dali 1 but with a more pronounced lateral constriction. Nasion is recessed, as with 66.7% of eAMPl, and it projects minimally relative to frontomalare orbitale. The frontal keel and the lateral supraorbital torus might have become thicker with maturity, but their forms are unlikely to have changed. Multiple variable analysis (i.e., principal component analysis) with seven cranial vault metrics (SI Appendix, section 5) shows HLD 6 far from earlier Chinese remains but in a position overlapping Indonesian late archaic humans, Neandertals, and western MPl humans.

HLD 6 presents a low and wide nasal aperture (30.0 mm) similar in breadth to other eAMPl (western MPl, 33.0 ± 4.4 mm, n = 13). The lateral nasal crest is simple [category 1 (35)], and the anterior nasal spine is minimally developed [category 0/1 (35)]. The nasal floor is sloping rather than bilevel as in most other eAMPl (36) (Fig. 3). The infraorbital foramina are double, with open cranial nerve V2 orbital floor paths. The infraorbital surfaces are largely flat, lack canine fossae, and continue to a rounded zygomatic profile with the midzygomatic root above M1 (the last aspect likely to have changed with facial growth). The inferior zygomaxillary profile lacks a malar incisure [incisura malaris (1)], similar to Jinniushan 1 and unlike other eAMPl. The subnasal height is low, reflecting modest incisor root lengths (SI Appendix, sections 6 and 7).

The mandibular symphysis presents a modest anterior retreat (79°), a planum alveolare, and a clearly delimited mental trigone [category 3 (37); Fig. 3]. The last feature is between categories 1 and 2 of earlier eAMPl (and other MPl symphyses globally) and categories 4 and 5 for Zhiren 3 and Tianyuan 1 (SI Appendix, section 8), and similar to 25.8% (n = 31) of Late Pleistocene archaic humans (29). The lateral corpus size scaled to mandibular length is similar to other eAMPl (SI Appendix, Fig. S23), but possibly affected by immaturity.

The ramus breadth (39.4 mm) is modest but unexceptional when scaled to mandible length (SI Appendix, Fig. S23). The medial ramus has an open mandibular foramen, and the gonial angle is mildly everted. However, it presents a large superior medial pterygoid tubercle [a common Neandertal feature (38)], similar to Xujiayao 14 and unlike the Zhoukoudian mandibles (2, 39).

The HLD Dental Remains.

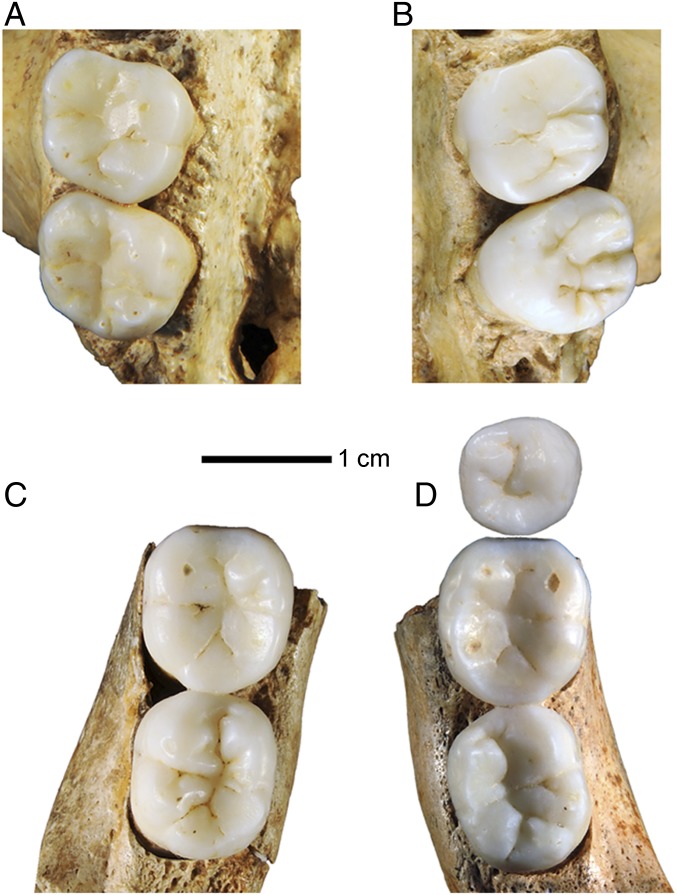

The HLD dental remains (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S24) present simple occlusal morphologies, especially vis-à-vis those from Zhoukoudian, Hexian, and Xujiayao (3, 11, 40). HLD 6 has four-cusp maxillary molars and five-cusp mandibular ones; its M2s present two additional small distal cusps, and its P4 has a large distal fossa. The HLD 1 M2 has a cusp 6, and the shovel-shaped HLD 13 I2 lacks a lingual tubercle.

Fig. 4.

Occlusal views of HLD 6 teeth: (A) right M1 and M2, (B) left M1 and M2, (C) left M1 and M2, and (D) right P4, M1, and M2.

The HLD M1, M2, P4, and C1 crown dimensions are unexceptional in an eAMPl context, although the HLD 6 M2s are narrow for their mesiodistal lengths (SI Appendix, Table S13). The HLD 7 and 9 P3s are relatively small, and the HLD 3 M3 is quite small (“area,” 93.1 mm2), slightly smaller than Zhoukoudian A2 (100.0 mm2) and H1 (102.0 mm2). HLD 6 exhibits right M3 agenesis, as does the M3 of Chenjiawo 1, and its left M3 crown is very small; its “area” of 69.2 mm2 is 2.44 SDs from an eAMPl mean (SI Appendix, Table S13). It is approached only by the Jinniushan 1 and Atapuerca 274 M3s (81.5 and 80.8 mm2, respectively) among MPl humans. The HLD teeth are therefore notable for their simple occlusal morphology and the reduction/agenesis of the M3s.

Discussion

The HLD human sample, primarily the HLD 6 skull but including the isolated cranial, dental, and femoral remains, provides a suite of morphological features that place it comfortably within the previously known Middle to early Late Pleistocene East Asian human variation and trends. These Middle-to-Late Pleistocene archaic human remains from East Asia can be grouped into four chronological groups, from the earlier Lantian–Chenjiawo, Yunxian, and Zhoukoudian; to Hexian and Nanjing; then Chaoxian, Dali, HLD, Jinniushan, and Panxian Dadong; and ending with Changyang, Xuchang, and Xujiayao. They are followed in the early Late Pleistocene by Huanglong, Luna, Fuyan, and Zhiren, which together combine archaic and modern features.

Along with these remains, the HLD human fossils exhibit consistent patterns of neurocranial form (wide, low, and rounded in posterior view), frontal keeling, nasal aperture form (low and wide), rounded supraorbital tori with an inferior glabella and a recessed nasion, sloping to bilevel nasal floors, and consistent mandibular hypertrophy. The HLD 3 and 6 M3 reduction is shared with Chenjiawo 1, Yunxian 2, Zhoukoudian A2 and H1, and Jinniushan 1. There are also trends in endocranial capacity (from the smaller Zhoukoudian sample and Nanjing 1 to the very large Xuchang 1), neurocranial superstructures (reductions in sagittal keels and supraorbital tori, especially into the Late Pleistocene), mandibular symphyses (becoming more vertical with more pronounced mental trigones), malar incisures (in the Zhoukoudian sample, Nanjing 1, and Dali 1, but not in HLD 6 and Jinniushan 1), and mandibular rami (large medial pterygoid tubercles in HLD 6 and Xujiayao 14). Other aspects are variable, as in dental occlusal complexity (low at HLD but generally complex in other eAMPL remains), medial supraorbital thickening with lateral thinning (strong in Dali 1 and HLD 6), and nasal floor pattern (sloping in HLD 6, bilevel in Chaoxian 1 and Xujiayao 1, and sloping/bilevel in Changyang 1). In addition, the reduced midfacial projection, mandibular symphyseal morphology, and dental crown simplicity foreshadow the patterns of early modern humans, supporting some degree of regional consistency from archaic to modern morphology (see also refs. 6, 17, and 18).

There is nonetheless substantial variation across the available East Asian sample within and across these chronological groups and especially in terms of individual traits and their combinations within specimens (SI Appendix, Figs. S16 and S17 and Tables S10, S12, and S13). However, similar variation within regions and within site samples is evident elsewhere during the MPl (as reflected in the persistent absence of taxonomic consensus regarding MPl humans; see refs. 19, 23, 41, and 42), and it need not imply more than normal variation among these fluctuating forager populations.

The growing human fossil sample from mainland East Asia, enhanced by the HLD remains, therefore provides evidence of continuity through later archaic humans, albeit with some degree of variation within chronological groups. As such, the sample follows the same pattern as the accumulating fossil evidence for MPl (variably into the Late Pleistocene) morphological continuity within regional archaic human groups in Europe (e.g., ref. 43), Northwest Africa (e.g., ref. 44), and insular Southeast Asia (e.g., refs. 21 and 24), as well as into early modern humans in East Africa (e.g., ref. 45). Several divergent peripheral samples [Denisova, Dinaledi, and Liang Bua (46–48)] do not follow this pattern, but they are best seen as interesting human evolutionary experiments (49) and not representative of Middle to Late Pleistocene human evolution. It is the core continental regions that provide the overall pattern of human evolution during this time period and form the background for the emergence of modern humans.

Although there is considerable interregional diversity across these Old World subcontinental samples, primarily in details of craniofacial morphology, these fossil samples exhibit similar trends in primary biological aspects (e.g., encephalization, craniofacial gracilization). Moreover, all of these regional groups of Middle to Late Pleistocene human remains reinforce that the dominant pattern through archaic humans [and variably into early modern humans through continuity or admixture (16, 50, 51)] was one of regional population consistency combined with global chronological trends.

Conclusion

The HLD later MPl human fossil sample, with an associated archaic human cranium and mandible in East Asia, provides considerable morphological evidence for a period of human emergence when remains tend to be scattered, fragmentary, and/or poorly dated. It substantially reinforces the pattern of MPl morphological variation and change in East Asia, especially showing continuity (with other later MPl remains) through the MPl and into the early Late Pleistocene. The skull and dental remains also exhibit features foreshadowing the subsequent transition to modern humans. More importantly, it is consistent with the pan-Old World pattern of regional change through this time period.

Materials and Methods

The human paleontological analysis is based on the morphological and morphometric analysis of the original HLD human fossils (SI Appendix, Table S7), using standard osteometric variables (52, 53) (SI Appendix, Tables S9 and S11). The original observations not outlined here are included in SI Appendix, sections 6–8 and Tables S9–S13. The analyses of the site structure and the lithic assemblage are included in SI Appendix, section 1. All remains referred to in this study are available in the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing. The comparative HLD faunal representation is included in SI Appendix, Table S1. The U-series dating methods are included in SI Appendix, section 2 and the detailed results included in SI Appendix, sections 5 and 6.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to colleagues who have provided access to comparative materials and/or other assistance with the research; W. Huang, Z.-X. Qiu, and T. Deng regarding the site’s geology; Z.-Y. Zhao for preparing, molding, and casting the human remains; L.-T. Zheng, L.-M. Zhang, P.-P. Wei, Y.-M. Zhang, L.-T. He, X. Zhang, and L. Pan for participation in the excavations; and X. Ding, Z.-X. Jia, and H.-L. Xiao for help with photography and the figures. The research was supported by Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences Grant XDB26000000; National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 41630102, 41672020, 41872029, and 41872030; Grand International Collaboration Project GJHZ1777 from the Chinese Academy of Science; National Science Foundation Grant 1702816; and Chinese Academy of Sciences President’s International Fellowship Initiative Grant 2017VCA0038.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1902396116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Weidenreich F. The skull of Sinanthropus pekinensis. Palaeontol Sinica. 1943;10D:1–484. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weidenreich F. The mandible of Sinanthropus pekinensis. Palaeontol Sinica. 1936;7D:1–132. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weidenreich F. The dentition of Sinanthropus pekinensis. Palaeontol Sinica. 1937;1D:1–180. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu XZ, Poirier F. Human Evolution in China. Oxford Univ Press; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu X, Athreya S. A description of the geological context, discrete traits, and linear morphometrics of the Middle Pleistocene hominin from Dali, Shaanxi Province, China. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2013;150:141–157. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu W, et al. Human remains from Zhirendong, South China, and modern human emergence in East Asia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:19201–19206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014386107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bae CJ, et al. Modern human teeth from late Pleistocene Luna Cave (Guangxi, China) Quat Int. 2014;354:169–183. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li ZY, et al. Late Pleistocene archaic human crania from Xuchang, China. Science. 2017;355:969–972. doi: 10.1126/science.aal2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu XJ, Crevecoeur I, Liu W, Xing S, Trinkaus E. Temporal labyrinths of eastern Eurasian Pleistocene humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:10509–10513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410735111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu W, et al. The earliest unequivocally modern humans in southern China. Nature. 2015;526:696–699. doi: 10.1038/nature15696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xing S, Martinón-Torres M, Bermúdez de Castro JM, Wu X, Liu W. Hominin teeth from the early late Pleistocene site of Xujiayao, Northern China. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2015;156:224–240. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu W, et al. Late Middle Pleistocene hominin teeth from Panxian Dadong, south China. J Hum Evol. 2013;64:337–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu W, Wu XJ, Xing S, Zhang YY. 2014. Human Fossils in China (Science Press, Beijing). Chinese.

- 14.Wolpoff MH, Caspari R. The origin of modern east Asians. Acta Anthropol Sinica. 2013;32:377–410. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu XZ. On the origin of modern humans in China. Quat Int. 2004;117:131–140. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao X, Zhang XL, Yang DY, Shen C, Wu XZ. Revisiting the origin of modern humans in China and its implications for global human evolution. Sci China Earth Sci. 2010;53:1927–1940. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shang H, Trinkaus E. The Early Modern Human from Tianyuan Cave, China. Texas A&M Univ Press; College Station, TX: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu Q, et al. DNA analysis of an early modern human from Tianyuan Cave, China. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:2223–2227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221359110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Athreya S, Wu X. A multivariate assessment of the Dali hominin cranium from China: Morphological affinities and implications for Pleistocene evolution in East Asia. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2017;164:679–701. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.23305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stringer C. The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2016;371:20150237. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antón SC. Evolutionary significance of cranial variation in Asian Homo erectus. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2002;118:301–323. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bae CJ, Douka K, Petraglia MD. On the origin of modern humans: Asian perspectives. Science. 2017;358:eaai9067. doi: 10.1126/science.aai9067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bae CJ. The late middle Pleistocene hominin fossil record of eastern Asia: Synthesis and review. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2010;143:75–93. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaifu Y. Archaic hominin populations in Asia before the arrival of modern humans. Curr Anthropol. 2017;58:S418–S433. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinón-Torres M, Xing S, Liu W, Bermúdez de Castro JM. A “source and sink” model for East Asia? Preliminary approach through dental evidence. C R Palevol. 2018;17:33–43. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xing S, et al. Hominin teeth from the Middle Pleistocene site of Yiyuan, eastern China. J Hum Evol. 2016;95:33–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tong HW, et al. Preliminary report on the mammalian fossils unearthed from the ancient human site of Hualong Cave in DongZhi, Anhui. Acta Anthropol Sin. 2018;37:284–305. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gong XC, et al. Human fossils found from Hualong Cave, Dongzhi County, Anhui Province. Acta Anthropol Sin. 2014;33:427–436. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weidenreich F. The extremity bones of Sinanthropus pekinensis. Palaeontol Sinica. 1941;5D:1–82. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trinkaus E, Ruff CB. Femoral and tibial diaphyseal cross-sectional geometry in Pleistocene Homo. Paleoanthropology. 2012;2012:13–62. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodríguez L, Carretero JM, García-González R, Arsuaga JL. Cross-sectional properties of the lower limb long bones in the Middle Pleistocene Sima de los Huesos sample (Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain) J Hum Evol. 2018;117:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.AlQahtani SJ, Hector MP, Liversidge HM. Brief communication: The London atlas of human tooth development and eruption. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2010;142:481–490. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gustafson G, Koch G. Age estimation up to 16 years of age based on dental development. Odontol Revy. 1974;25:297–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ubelaker DH. Human Skeletal Remains. Aldine; Chicago: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Franciscus RG. Internal nasal floor configuration in Homo with special reference to the evolution of Neandertal facial form. J Hum Evol. 2003;44:701–729. doi: 10.1016/s0047-2484(03)00062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu XJ, Maddux SD, Pan L, Trinkaus E. Nasal floor variation among eastern Eurasian Pleistocene Homo. Anthropol Sci. 2012;120:217–226. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dobson SD, Trinkaus E. Cross-sectional geometry and morphology of the mandibular symphysis in Middle and Late Pleistocene Homo. J Hum Evol. 2002;43:67–87. doi: 10.1006/jhev.2002.0563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trinkaus E, Buzhilova AP, Mednikova MB, Dobrovolskaya MV. The People of Sunghir. Oxford Univ Press; New York: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu XJ, Trinkaus E. The Xujiayao 14 mandibular ramus and Pleistocene Homo mandibular variation. C R Palevol. 2014;13:333–341. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xing S, et al. Middle Pleistocene hominin teeth from Longtan Cave, Hexian, China. PLoS One. 2014;9:e114265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stringer C. The status of Homo heidelbergensis (Schoetensack 1908) Evol Anthropol. 2012;21:101–107. doi: 10.1002/evan.21311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manzi G. Humans of the Middle Pleistocene: The controversial calvarium from Ceprano (Italy) and its significance for the origin and variability of Homo heidelbergensis. Quat Int. 2016;411B:254–261. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arsuaga JL, et al. Neandertal roots: Cranial and chronological evidence from Sima de los Huesos. Science. 2014;344:1358–1363. doi: 10.1126/science.1253958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hublin JJ, et al. New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens. Nature. 2017;546:289–292. doi: 10.1038/nature22336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bräuer G. The origin of modern anatomy: By speciation or intraspecific evolution? Evol Anthropol. 2008;17:22–37. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reich D, et al. Genetic history of an archaic hominin group from Denisova Cave in Siberia. Nature. 2010;468:1053–1060. doi: 10.1038/nature09710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown P, et al. A new small-bodied hominin from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia. Nature. 2004;431:1055–1061. doi: 10.1038/nature02999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berger LR, et al. Homo naledi, a new species of the genus Homo from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa. eLife. 2015;4:e09560. doi: 10.7554/eLife.09560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trinkaus E. An abundance of developmental anomalies and abnormalities in Pleistocene people. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:11941–11946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1814989115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trinkaus E. Early modern humans. Annu Rev Anthropol. 2005;34:207–230. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fu Q, et al. The genetic history of ice age Europe. Nature. 2016;534:200–205. doi: 10.1038/nature17993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bräuer G. Osteometrie. In: Knussman R, editor. Anthropologie. Fischer; Stuttgart: 1988. pp. 160–232. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Howells WW. Cranial variation in man. Pap Peabody Mus. 1973;67:1–259. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.