Abstract

Background:

Studies postulate that certain religious beliefs related to medical care influence advanced cancer patients’ end-of-life (EOL) medical decision-making and care. Because no current measure explicitly assesses such beliefs, we here introduce and evaluate the Religious Beliefs in EOL Medical Care (RBEC) scale, a new measure designed to assess religious beliefs in the context of EOL cancer care.

Methods:

The RBEC scale consists of seven items designed to reflect religious beliefs in EOL medical care. Its psychometric properties were evaluated in a sample of advanced cancer patients (N=275) from Coping with Cancer II, an NCI-funded, multi-site, longitudinal, observational study of communication processes and outcomes in EOL cancer care.

Results:

The RBEC scale proved to be internally consistent (Cronbach’s α=0.81), unidimensional, positively associated with other indicators of patients’ religiousness and spirituality (establishing its convergent validity), and inversely associated with patients’ terminal illness understanding and acceptance (establishing its criterion validity), suggesting its potential clinical utility in promoting informed EOL decision-making. Most patients (87%) reported some (‘somewhat’, ‘quite a bit’ or ‘a great deal’) endorsement of at least one RBEC item and a majority (62%) endorsed three or more RBEC items.

Conclusions:

The RBEC scale is a reliable and valid tool assessing religious beliefs in the context of EOL medical care, beliefs that are frequently endorsed and inversely associated with terminal illness understanding.

Keywords: Religion, cancer, end-of-life care, spirituality, psychometrics

Precis:

Patients with advanced cancers frequently hold religious beliefs in EOL medical care (RBEC), and these beliefs are related to lower levels of illness understanding. The RBEC scale is a valid and reliable tool to assess these beliefs.

INTRODUCTION

Religion and spirituality (R/S) play important roles in patients’ experiences of life-threatening illnesses such as cancer.1 R/S has been shown to influence cancer patient quality of life2,3 and medical decision-making.4,5 Patients who rely heavily on their religious beliefs to cope with cancer have been shown to receive more aggressive interventions (e.g., cardiopulmonary resuscitation and ventilation) in the last week of life compared to those who rely less heavily on R/S beliefs.4 Furthermore, spiritual support from medical teams has been shown to be associated with higher rates of hospice enrollment and fewer aggressive medical interventions at life’s end.6 In contrast, spiritual support from a patient’s religious community has been associated with lower rates of hospice enrollment and more intensive medical interventions at the end of life (EOL).7

Complex relationships between patient religiousness, religious coping, and spiritual care from religious communities and medical care teams on EOL care highlight the need to clarify the particular R/S beliefs that influence care near death. It has been hypothesized that underlying religious beliefs related to EOL care contribute to medical decisions leading to more aggressive care at life’s end. Accordingly, religious beliefs pertaining to EOL medical care – arising from and reinforced by personal religiousness and by spiritual support from religious communities – may result in medical decisions that can forestall acceptance of incurable illness and promote the use of care focused on life-prolongation and cure, even in terminal illness. Religion, spirituality, and related beliefs influencing illness understanding and medical care decisions are critical to understand within serious illness as part of culturally-sensitive and patient-centered communication and care.

Particular religious beliefs expected to influence EOL medical decision-making and care have been proposed in the literature,1,4,8–20 including: (1) God’s sovereignty (e.g., treatment decisions), (2) sanctity of life, (3) miracles, and (4) sanctification through suffering. However, to our knowledge, there does not exist a scale developed to assess these constructs and examine their performance in a terminally-ill patient sample. We have developed a measure for this explicit purpose; that is, an assessment that captures each of the four themes noted above as they relate to the provision of end-stage cancer care. Based on a thorough review of the literature and discussion among the authors for the crafting of items, we developed the Religious Beliefs in EOL Medical Care (RBEC) measure and included it in the multi-site, National Cancer Institute-funded, prospective cohort Coping with Cancer II study (CwC-II). The aim of CwC-II was to evaluate factors influencing EOL care communication and secondarily assessing psychosocial and spiritual factors, including RBEC, and how they influence understanding of terminal illness.

We hypothesized that religious beliefs in EOL care would be common in the experience of advanced cancer, and that they would be related to patient religiousness, daily spiritual experiences, and spiritual care from religious communities. Additionally, we hypothesized that stronger endorsement of RBEC would be inversely related to terminal illness understanding given past evidence of lower rates of terminal illness acknowledgment associated with patients’ degree of religious coping.4

METHODS

Study Sample

The sample was derived from NCI-funded CWC-II (CA106370; PI: Prigerson). CwC-II participants were recruited from November 2010 through April 2015 from outpatient facilities of eight US cancer centers: Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA); Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (New York, NY); Parkland Hospital (Dallas, TX); Pomona Valley Hospital Medical Center (Pomona, CA); Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center (Dallas, TX); Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center (Richmond, VA); Weill Cornell Medical College Meyer Cancer Center (New York, NY); and Yale Cancer Center (New Haven, CT). Institutional review boards of all participating institutions approved study procedures.

Eligibility criteria included: Black or White race, age 21 or greater, stage IV gastrointestinal, gynecologic, and lung cancers or stage III cancers (e.g., pancreas and lung) deemed ‘incurable and poor prognosis’ by an oncologist, oncologist-estimated life expectancy of 6 months or less, disease progression after one or more chemotherapy regimens or, for advanced colorectal cancers, progression after two chemotherapy regimens. Patients were ineligible if they had cognitive impairment, were too weak to perform the interview, or if they were receiving hospice or palliative care.

The sample (N=275) consisted of patient participants who provided responses to items assessing RBEC during their baseline interview, administered by trained interviewers. Among 482 eligible patients, we enrolled and interviewed 374 (78%) at baseline. Among those 374, 99 (26%) were excluded due to missing data on analyzed variables: 24 (6%) due to missing data for the RBEC scale (which may lack meaning for non-religious or non-Christian patients); 52 (14%) due to missing data for terminal illness understanding (primarily for the life-expectancy item); and 23 (6%) due to missing data for sociodemographic characteristics. The vast majority (84%) of patients in the study sample were receiving either chemotherapy or radiation therapy at the time of their baseline interviews. Receipt of these treatments was not associated with patients’ terminal illness understanding.

Measures

Religious Beliefs in End-of-Life Medical Care (RBEC):

Seven-items assessing patient RBEC were developed by an expert panel [MJB (theology, palliative care), TAB (oncology, palliative care, spirituality/EOL care), ACE (oncology, palliative care, spirituality/EOL care), TJV (epidemiology, causal methods, religion/health), and HGP (psychosocial oncology, measure development)]. Beliefs potentially associated with EOL care were based on the medical literature,1,4,8–20 and addressed four religious belief themes potentially related to medical care decision-making: God’s sovereignty, sanctity of life, miracles, and sanctification through suffering. Patients were asked, “To what extent do you agree with each of the following statements?” Seven beliefs displayed in Table 1 were then assessed with patients indicating their degree of agreement on a 5-point scale: (1) not at all, (2) a little, (3) somewhat, (4) quite a bit, (5) a great deal.

Table 1:

Religious Beliefs in End-of-Life Medical Care Scale Items

| Item | Theme(s) |

|---|---|

| My belief in God relieves me of needing to think about future medical decisions (e.g., do-not-resuscitate order or healthcare proxy) especially near the end of life. | God’s sovereignty |

| I will accept every possible medical treatment because my faith tells me to do everything I can to stay alive longer. | Sanctity of life |

| I think agreeing to a do-not-resuscitate order is immoral because of my religious beliefs. | Sanctity of life |

| I would be giving up on my faith if I stopped pursuing cancer treatment. | Sanctity of life |

| I believe that God could perform a miracle in curing me of cancer. | Miracles, God’s sovereignity |

| I must faithfully endure painful medical procedures because suffering is part of God’s way of testing me. | Sanctification through suffering |

| My faith helps me to endure the suffering that comes with difficult medical treatments. | Sanctification through suffering |

Sociodemographic Characteristics:

Patients reported information on their age, gender, race, ethnicity, health insurance status, education level, marital status, and religious identification in the baseline interview. Patients’ sites of recruitment were coded to indicate geographic region (Northeast vs. South/West).

Religious and Spiritual Characteristics:

Patients were asked the degree to which they considered themselves to be (1) religious and (2) spiritual using items from the Multi-dimensional Measure of Religiousness and Spirituality (MMRS). 21 Response options were: “not at all”, “slightly”, “moderately”, or “very” religious or spiritual. Two additional items from the MMRS were used to assess daily spiritual experiences: To what extent can you say you experience the following on a 6-point scale from “never to almost never” to “many times a day”: (1) You feel God’s presence and (2) You are spiritually touched by the beauty of creation. Finally, patients were asked, “To what extent are your religious/spiritual needs being supported by your spiritual community (e.g., clergy, members of your congregation)? Response options were on a 5-point scale from “not at all” to “a great deal”.

Terminal Illness Understanding:

Illness understanding (IU) and acceptance was assessed with four items that assessed: (1) the patient’s terminal illness acknowledgement; (2) recognition of disease as incurable; (3) knowledge of advanced stage of disease; and (4) expectation to live months as opposed to years. Items and their response options are described previously.22 Responses were coded 0 or 1, absence or presence, respectively, for each of these items which were then summed (possible 0 to 4); higher scores indicate greater understanding of illness.

Statistical Methods

Responses to RBEC scale items were evaluated both as proportions for each response option and as mean and standard deviations for each item. RBEC scale scores were calculated as the average score of the RBEC items. Pearson correlations were used to estimate item-total correlations between RBEC items and the total RBEC score. Cronbach’s alpha was used to evaluate the internal consistency of the RBEC items, and a principal components analysis was conducted to evaluate the dimensionality of the RBEC scale construct.

Pearson correlations were used to evaluate associations between patients’ RBEC scores and illness understanding (IU) sum scores, and between their religious and spiritual characteristics and both RBEC and IU scores.

Associations between sociodemographic characteristics and RBEC scores were evaluated as least-squares-mean RBEC scores and associated standard errors for each category for each characteristic estimated using generalized linear models (GLMs). A single-predictor GLM was constructed for each sociodemographic characteristic to evaluate its bivariate association with RBEC score. A multiple-predictor GLM including all of the patient sociodemographic characteristics as predictors of RBEC score was used to evaluate associations between each characteristic and RBEC score adjusted for each of the other characteristics.

Associations between RBEC scores, sociodemographic characteristics and IU scores were also evaluated within the context of GLMs. A single-predictor GLM for IU scores was constructed for the RBEC score and for each sociodemographic characteristic to evaluate its bivariate association with IU score. A multiple-predictor GLM including RBEC score and all of the sociodemographic characteristics as predictors of IU score was used to evaluate associations between each predictor and IU score adjusted for each of the other predictors in the model.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Sociodemographic Characteristics (Table 2)

Table 2:

Sociodemographic characteristics (N=275)

| Variable | Group | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Under 55 | 73 | 26.6 |

| 55 to 64 | 115 | 41.8 | |

| 65+ | 87 | 31.6 | |

| Gender | Male | 88 | 32.0 |

| Female | 187 | 68.0 | |

| Race | Black | 60 | 21.8 |

| White | 215 | 78.2 | |

| Ethnicity | Latino | 34 | 12.4 |

| non-Latino | 241 | 87.6 | |

| Insured | Yes | 224 | 81.5 |

| No | 51 | 18.6 | |

| Education | Beyond HS | 174 | 63.3 |

| Not Beyond HS | 101 | 36.7 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 156 | 56.7 |

| Not Married | 119 | 43.3 | |

| Religion | Catholic | 112 | 40.7 |

| Protestant | 56 | 20.4 | |

| Baptist | 46 | 16.7 | |

| Other-Christian | 17 | 6.2 | |

| Jewish | 23 | 8.4 | |

| Other | 9 | 3.3 | |

| None | 12 | 4.4 | |

| Region* | Northeast | 174 | 63.3 |

| South/West | 101 | 36.7 |

Abbreviations: HS – high school

Regions include Northeast: Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA); Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (New York, NY); Weill Cornell Cancer Center (New York, NY); and Yale Cancer Center (New Haven, CT); and South/West: Parkland Hospital (Dallas, TX); Pomona Valley Medical Center (Pomona, CA); Simmons Cancer Center (Dallas, TX); Virginia Commonwealth University Cancer Center (Richmond, VA)

Patient mean age was 60.1 (SD=10.4) years. Majorities were female (68.0%), and identified as White (78.2%) and non-Latino (87.6%). Nearly two-thirds (63.3%) had education beyond high school, and just over half were married (56.7%). The most common religious tradition patients identified with was Catholic (40.7%), followed by Protestant (20.4%) and Baptist (16.7%).

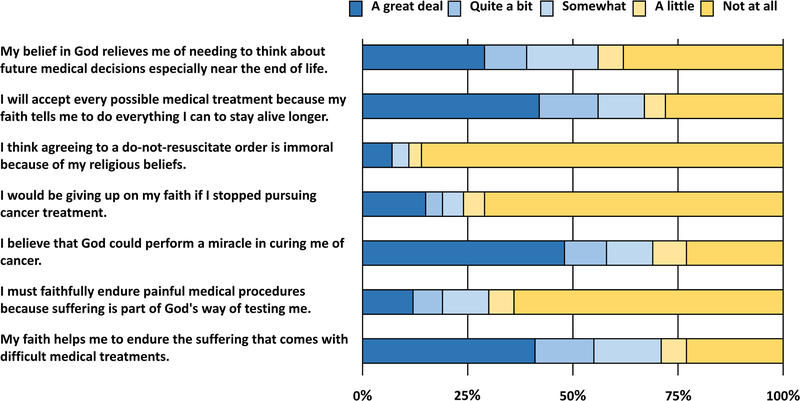

Endorsements of RBEC Items (Figure 1)

Figure 1:

Distribution of responses to Religious Beliefs in End-of-Life Medical Care scale items (N=275)

Figure 1 shows the proportions of patients endorsing each response option for each RBEC item. The most commonly highly endorsed items (i.e., at least ‘somewhat’) were “my faith helps me to endure the suffering that comes with difficult medical treatments” (71%); “I will accept every possible medical treatment because my faith tells me to do everything I can to stay alive longer” (67%); and “I believe God could perform a miracle in curing me of cancer” (69%). Most patients (87%) reported some (‘somewhat’, ‘quite a bit’ or ‘a great deal’) endorsement of at least one of the RBEC items and a majority (62%) endorsed three or more RBEC items.

RBEC Scale Properties (Table 3)

Table 3:

Religious beliefs in end-of-life medical care means and item-total correlations (N=275)

| Item | N | Mean | SD | Correlation with Average Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| My belief in God relieves me of needing to think about future medical decisions (e.g., do-not-resuscitate order or healthcare proxy) especially near the end of life. |

266 | 2.86 | 1.68 | 0.76 |

| I will accept every possible medical treatment because my faith tells me to do everything I can to stay alive longer. |

274 | 3.37 | 1.69 | 0.72 |

| I think agreeing to a do-not-resuscitate order is immoral because of my religious beliefs. | 266 | 1.39 | 1.08 | 0.48 |

| I would be giving up on my faith if I stopped pursuing cancer treatment. |

274 | 1.86 | 1.49 | 0.63 |

| I believe that God could perform a miracle in curing me of cancer. |

267 | 3.52 | 1.67 | 0.75 |

| I must faithfully endure painful medical procedures because suffering is part of God’s way of testing me. |

268 | 1.97 | 1.46 | 0.72 |

| My faith helps me to endure the suffering that comes with difficult medical treatments. |

263 | 3.43 | 1.61 | 0.73 |

| Average Score | 275 | 2.61 | 1.07 | 1.00 |

Item-total correlations revealed high item-total correlations (>0.7) for five items and moderate correlations for the items “do not resuscitate orders are immoral due to religious beliefs” (0.48) and “I would be giving up on my faith if I stopped pursuing cancer treatment” (0.63). Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.81, indicating good internal consistency. In a principal components factor analysis of the RBEC scale items, only the first component factor (eigenvalue λ1=3.25, variance explained=46%) had an eigenvalue greater than 1, indicating that underlying RBEC construct is unidimensional and adequately represented by an item sum, or equivalently an item average, aggregate measure.

Religious/Spiritual Variables and Illness Understanding, and Their Associations with RBEC (Table 4)

Table 4:

Associations between RBEC scores with religious/spiritual items and illness understanding scores (N=275)

| RBEC | IU Sum | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale/Item | N | Mean | SD | r | p | r | p |

| RBEC | 275 | 2.6 | 1.1 | 1.00 | N/A | −0.19 | 0.002 |

| To what extent do you consider yourself a religious person? | 274 | 2.9 | 1.0 | 0.58 | 0.000 | −0.02 | 0.733 |

| To what extent do you consider yourself a spiritual person? | 274 | 3.1 | 0.9 | 0.45 | 0.000 | −0.04 | 0.466 |

| I feel God’s presence | 259 | 3.9 | 1.8 | 0.64 | 0.000 | −0.11 | 0.086 |

| I am spiritually touched by the beauty of creation | 258 | 4.3 | 1.5 | 0.37 | 0.000 | −0.09 | 0.159 |

| To what extent are your religious/spiritual needs being supported by your spiritual community | 245 | 3.2 | 1.7 | 0.55 | 0.000 | −0.01 | 0.935 |

Abbreviations: RBEC – religious beliefs in end-of-life medical care; IU – illness understanding

Most patients considered themselves moderately or very religious (68.6%) and moderately or very spiritual (79.9%). Most noted feeling God’s presence at least some days (70.7%) and feeling touched by the beauty of creation at least some days (83.7%). Nearly half (48.8%) experienced quite a bit or a great deal of support of their religious/spiritual needs from their spiritual community. Consistent with a prior study also employing CwC-II data,22 nearly half of patients (48%) had poor illness understanding (scores 0–1 of possible 4); 28% had moderate (score 2) illness understanding; and 23% had good (scores 3–4) understanding of terminal illness.

Table 4 shows the significant positive associations of the RBEC scores with the religiousness, spirituality, spiritual experiences, and religious community spiritual support items (all p<0.001). RBEC was also associated with worse terminal illness understanding (r=−0.19, p=0.002), while the other religious/spiritual items were not associated with illness understanding.

Sociodemographic Characteristics as Predictors of RBEC (Table 5)

Table 5:

Associations (unadjusted and adjusted) between sociodemographic characteristics and RBEC scores (N=275)

| RBEC Score (single predictor) | RBEC Score (multiple predictors*) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Group | LS Mean | SE | p | LS Mean | SE | p |

| Age | Under 55 | 2.68 | 0.13 | 0.43 | 2.82 | 0.14 | 0.98 |

| 55 to 64 | 2.66 | 0.10 | 2.83 | 0.13 | |||

| 65+ | 2.49 | 0.11 | 2.84 | 0.15 | |||

| Gender | Male | 2.83 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 2.86 | 0.15 | 0.65 |

| Female | 2.51 | 0.08 | 2.80 | 0.12 | |||

| Race | Black | 3.53 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 3.25 | 0.16 | 0.00 |

| White | 2.35 | 0.07 | 2.41 | 0.12 | |||

| Ethnicity | Latino | 2.99 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 2.89 | 0.19 | 0.53 |

| non-Latino | 2.56 | 0.07 | 2.77 | 0.10 | |||

| Insured | Yes | 2.48 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 2.85 | 0.12 | 0.77 |

| No | 3.18 | 0.15 | 2.80 | 0.17 | |||

| Education | Beyond HS | 2.35 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 2.71 | 0.14 | 0.06 |

| Not Beyond HS | 3.06 | 0.10 | 2.95 | 0.13 | |||

| Marital Status | Married | 2.54 | 0.09 | 0.20 | 2.90 | 0.13 | 0.22 |

| Not Married | 2.71 | 0.10 | 2.76 | 0.13 | |||

| Religion | Catholic | 2.45 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 3.05 | 0.13 | 0.00 |

| Protestant | 2.80 | 0.13 | 3.18 | 0.15 | |||

| Baptist | 3.45 | 0.14 | 3.13 | 0.17 | |||

| Other-Christian | 2.71 | 0.23 | 2.79 | 0.24 | |||

| Jewish | 1.52 | 0.20 | 2.32 | 0.22 | |||

| Other | 2.47 | 0.32 | 3.03 | 0.32 | |||

| None | 2.12 | 0.28 | 2.31 | 0.27 | |||

| Region | Northeast | 2.25 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 2.56 | 0.17 | 0.00 |

| South/West | 3.23 | 0.10 | 3.10 | 0.12 | |||

Abbreviations: RBEC – religious beliefs in end-of-life medical care; LS – least square; SE – standard error; HS – high school

Model includes all covariates simultaneously.

In the multivariable model that included all sociodemographic characteristics as predictors, higher RBEC scores were significantly associated with being Black as opposed to White, with some religious traditions (e.g., all but Jewish or None), and with the South/West as opposed to the Northeast.

RBEC and Sociodemographic Characteristics as Predictors of Illness Understanding (Table 6)

Table 6:

Associations (unadjusted and adjusted) between RBEC scores, sociodemographic variables and illness understanding scores (N=275)

| IU Score (single predictor) | IU Score (multiple predictors*) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | |

| RBEC Score | −0.20 | 0.07 | 0.00 | −0.22 | 0.08 | 0.01 | |

| Variable | Group | LS Mean | SE | p | LS Mean | SE | p |

| Age | Under 55 | 1.45 | 0.14 | 0.37 | 1.35 | 0.19 | 0.49 |

| 55 to 64 | 1.70 | 0.11 | 1.50 | 0.17 | |||

| 65+ | 1.56 | 0.13 | 1.32 | 0.20 | |||

| Gender | Male | 1.58 | 0.13 | 0.93 | 1.36 | 0.19 | 0.71 |

| Female | 1.59 | 0.09 | 1.42 | 0.15 | |||

| Race | Black | 1.42 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 1.36 | 0.22 | 0.83 |

| White | 1.64 | 0.08 | 1.41 | 0.16 | |||

| Ethnicity | Latino | 1.18 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 1.26 | 0.25 | 0.26 |

| non-Latino | 1.65 | 0.08 | 1.52 | 0.13 | |||

| Insured | Yes | 1.67 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 1.58 | 0.16 | 0.07 |

| No | 1.25 | 0.16 | 1.19 | 0.22 | |||

| Education | Beyond HS | 1.74 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 1.51 | 0.18 | 0.14 |

| Not Beyond HS | 1.34 | 0.12 | 1.27 | 0.17 | |||

| Marital Status | Married | 1.65 | 0.09 | 0.30 | 1.47 | 0.18 | 0.28 |

| Not Married | 1.50 | 0.11 | 1.31 | 0.17 | |||

| Religion | Catholic | 1.45 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 1.23 | 0.17 | 0.09 |

| Protestant | 1.73 | 0.15 | 1.46 | 0.20 | |||

| Baptist | 1.61 | 0.17 | 1.53 | 0.23 | |||

| Other-Christian | 1.06 | 0.28 | 0.79 | 0.31 | |||

| Jewish | 2.04 | 0.24 | 1.52 | 0.29 | |||

| Other | 2.33 | 0.39 | 2.06 | 0.41 | |||

| None | 1.50 | 0.33 | 1.12 | 0.36 | |||

| Region* | Northeast | 1.63 | 0.09 | 0.43 | 1.17 | 0.22 | 0.05 |

| South/West | 1.51 | 0.12 | 1.61 | 0.16 | |||

Abbreviations: RBEC – Religious beliefs in end-of-life medical care; IU – Illness understanding; HS – high school;

Model includes all covariates simultaneously.

In bivariate models, worse illness understanding was significantly associated with higher RBEC scores, Latino ethnicity, uninsured status, lower education, and some religious traditions (e.g., Catholic, Other-Christian, or None). In the multivariable model that included RBEC scores and all sociodemographic characteristics as predictors, the only remaining significant predictors of worse illness understanding were higher RBEC scores and recruitment in the Northeast.

DISCUSSION

Findings from this study demonstrate that religious beliefs in the context of end-of-life medical care are common in advanced cancer, with a majority having some endorsement of three or more of seven beliefs. The RBEC items revealed a high degree of internal consistency of the items and proved to be unidimensional. RBEC scores were closely associated with patient spirituality, daily spiritual experiences, and spiritual care from religious communities, supporting the convergent validity of the RBEC scale. Additionally, we hypothesized that greater RBEC scores would be related to reduced illness understanding, over and above the effects of other R/S measures. This hypothesis was supported, thereby, establishing the criterion validity of this novel scale.

Greater endorsement of the RBEC items was found among Black patients, patients of certain religious faiths (e.g, Catholic, Protestant, Baptist) and patients recruited from Southern and Western state study sites. Furthermore, greater endorsement of RBEC was significantly associated with less understanding of the terminal nature of illness in bivariate and multivariable models, with the associations between RBEC and illness understanding in the small (|r|=0.1) to medium (|r|=0.3) effect size range.23 Although being Latino, uninsured, less educated, and certain religious faiths were significantly associated with reductions in illness understanding in bivariate analyses, these associations no longer remained significant once RBEC scores were included in the model. This suggests that RBEC may be a critical factor explaining Latino ethnicity and educational disparities in illness understanding, and suggests the potential role of religious beliefs in patient illness understanding. The only other factor significantly associated with illness understanding in multivariate analyses was region, with patients from Northeastern sites having reduced illness understanding. This may be due to regional/institutional differences in frequency of EOL conversations24, which have been shown to be associated with greater illness understanding.22

The influence of religious beliefs on EOL medical care decision-making has been hypothesized as a potential causal pathway between religious variables and patient EOL medical care preferences and care received. Phelps et al., in prospective cohort study of advanced cancer patients, found that patients who turn to religion as a major source of coping with their illness, both preferred and received more aggressive EOL care (e.g., resuscitation, ventilation).4 Hypothesized mechanisms included belief in miraculous cure through high risk therapies, religiously-based moral concerns regarding life-sustaining treatments, equating forgoing aggressive therapies as violating God’s sovereignty, and seeing religious purpose in suffering through invasive treatments. Advanced cancer patients reporting high spiritual support from their religious communities, in analyses that accounted for patient religious coping, found them to be less likely to receive hospice care and more likely to undergo aggressive medical interventions.7 These, and other studies demonstrating associations between religious variables and EOL care decision-making,5,25 may reflect the causal role of RBEC that are captured in the RBEC scale.

Future work will examine longitudinal associations between RBEC scores and EOL decisions. The individual items of the RBEC scale were constructed so that specific religious beliefs (concerning miracles, sanctity of life, sanctification through suffering, and God’s sovereignty) were framed to be relevant for EOL decisions. Further ethical and pastoral reflection is needed, but information on associations with individual RBEC items may be of interest in intervention development and in the provision of spiritual care from both medical teams and patients’ religious communities. While religious values are critical to uphold as part of culturally-sensitive, patient-centered care, a theologically-consistent reframing of religious values in EOL care may be appropriate. For example, a patient may affirm sanctity of life or God’s sovereignty without believing that this requires “accepting every possible medical treatment”.

The study of the interplay between religion, spirituality, medical decision-making and care requires the use of relevant, psychometrically sound instruments.26 We developed such an instrument to assess the role of specific religious beliefs in EOL care decision-making among advanced cancer patients. By contributing a valid and reliable tool for assessing these religious beliefs, this scale should be a resource to studies examining factors impacting medical care decision-making in advanced illness and to studies examining the complex interplay of religion, health and illness.27,28

Limitations of this study include that the sample is a U.S., advanced cancer population that predominantly identifies with various Christian traditions. Furthermore, cognitive testing was not performed as part of the item development. Thus, this scale needs further testing and validation in other disease, religious and cultural contexts. Also, the RBEC specifically assesses religious beliefs that are interfacing with decisions for more aggressive medical interventions at life’s end. Further study, and scale development, is required of R/S beliefs that may influence decisions for more comfort-focused EOL medical care.

CONCLUSION

In summary, religious beliefs in EOL medical care are common among patients with advanced cancer. The seven-item RBEC scale shows excellent reliability and construct and criterion validity supporting its utility in the study of religion, spirituality and EOL care decision-making.

Acknowledgments

Funding support: This study was supported by: CA106370 (HGP) and CA197730 (HGP) from the National Cancer Institute, MD007652 (PKM, HGP) from the National Institute of Minority Heath and Health Disparities and a grant from the John Templeton Foundation (TAB).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alcorn SR, Balboni MJ, Prigerson HG, et al. : “If God wanted me yesterday, I wouldn’t be here today”: religious and spiritual themes in patients’ experiences of advanced cancer. J Palliat Med 13:581–8, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brady MJ, Peterman AH, Fitchett G, et al. : A case for including spirituality in quality of life measurement in oncology. Psychooncology 8:417–28, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vallurupalli M, Lauderdale K, Balboni MJ, et al. : The role of spirituality and religious coping in the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative radiation therapy. J Support Oncol 10:81–7, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phelps AC, Maciejewski PK, Nilsson M, et al. : Religious coping and use of intensive life-prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer. Jama 301:1140–7, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silvestri GA, Knittig S, Zoller JS, et al. : Importance of faith on medical decisions regarding cancer care. J Clin Oncol 21:1379–82, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balboni TA, Paulk ME, Balboni MJ, et al. : Provision of spiritual care to patients with advanced cancer: associations with medical care and quality of life near death. J Clin Oncol 28:445–52, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balboni TA, Balboni M, Enzinger AC, et al. : Provision of spiritual support to patients with advanced cancer by religious communities and associations with medical care at the end of life. JAMA Intern Med 173:1109–17, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bulow HH, Sprung CL, Reinhart K, et al. : The world’s major religions’ points of view on end-of-life decisions in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med 34:423–30, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crawley L, Payne R, Bolden J, et al. : Palliative and end-of-life care in the African American community. Jama 284:2518–21, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frick E, Riedner C, Fegg MJ, et al. : A clinical interview assessing cancer patients’ spiritual needs and preferences. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 15:238–43, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson KS, Elbert-Avila KI, Tulsky JA: The influence of spiritual beliefs and practices on the treatment preferences of African Americans: a review of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc 53:711–9, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson KS, Kuchibhatla M, Tulsky JA: What explains racial differences in the use of advance directives and attitudes toward hospice care? J Am Geriatr Soc 56:1953–8, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson SC, Spilka B.: Coping with breast cancer: the role of clergy and faith. Journal of Religion and Health 30:21–33, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koenig HG: Religious attitudes and practices of hospitalized medically ill older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 13:213–24, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koenig HG: MSJAMA: religion, spirituality, and medicine: application to clinical practice. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 284:1708, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koenig HG: Religion, spirituality, and medicine: how are they related and what does it mean? Mayo Clin Proc 76:1189–91., 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mansfield CJ, Mitchell J, King DE: The doctor as God’s mechanic? Beliefs in the Southeastern United States. Social science & medicine 54:399–409, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pargament K, Mahoney A: Sacred Matters: Sanctification as a vital topic for the psychology of religion. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 15:179–99, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith AK, Sudore RL, Perez-Stable EJ: Palliative care for Latino patients and their families: whenever we prayed, she wept. Jama 301:1047–57, E1, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sulmasy DP: Spiritual issues in the care of dying patients: ". . . it’s okay between me and god". JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 296:1385–92, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fetzer Institute / National Institute on Aging Working Group. Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality for Use in Health Research: A Report of the Fetzer Institute / National Institute on Aging Working Group (1st ed.). Kalamazoo, Fetzer Institute, 1999, pp 95 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Epstein AS, Prigerson HG, O’Reilly EM, et al. : Discussions of Life Expectancy and Changes in Illness Understanding in Patients With Advanced Cancer. J Clin Oncol 34:2398–403, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen J: A power primer. Psychol Bull 112:155–9, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright AA, Zhang B, Keating NL, et al. : Associations between palliative chemotherapy and adult cancer patients’ end of life care and place of death: prospective cohort study. BMJ 348:g1219, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.True G, Phipps EJ, Braitman LE, et al. : Treatment preferences and advance care planning at end of life: the role of ethnicity and spiritual coping in cancer patients. Ann Behav Med 30:174–9, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selman L, Harding R, Gysels M, et al. : The measurement of spirituality in palliative care and the content of tools validated cross-culturally: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 41:728–53, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKinley WO, Huang ME, Brunsvold KT: Neoplastic versus traumatic spinal cord injury: an outcome comparison after inpatient rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 80:1253–7, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care: Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care, Second Edition, 2009, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]