Abstract

DNA damage is ubiquitous and can arise from endogenous or exogenous sources. DNA-damaging alkylating agents are present in environmental toxicants as well as in cancer chemotherapy drugs and are a constant threat, which can lead to mutations or cell death. All organisms have multiple DNA repair and DNA damage tolerance pathways to resist the potentially negative effects of exposure to alkylating agents. In bacteria, many of the genes in these pathways are regulated as part of the SOS reponse or the adaptive response. In this work, we probed the cellular responses to the alkylating agents chloroacetaldehyde (CAA), which is a metabolite of 1,2-dichloroethane used to produce polyvinyl chloride, and styrene oxide (SO), a major metabolite of styrene used in the production of polystyrene and other polymers. Vinyl chloride and styrene are produced on an industrial scale of billions of kilograms annually and thus have a high potential for environmental exposure. To identify stress response genes in E. coli that are responsible for tolerance to the reactive metabolites CAA and SO, we used libraries of transcriptional reporters and gene deletion strains. In response to both alkylating agents, genes associated with several different stress pathways were upregulated, including protein, membrane, and oxidative stress, as well as DNA damage. E. coli strains lacking genes involved in base excision repair and nucleotide excision repair were sensitive to SO, whereas strains lacking recA and the SOS gene ybfE were sensitive to both alkylating agents tested. This work indicates the varied systems involved in cellular responses to alkylating agents, and highlights the specific DNA repair genes involved in the responses.

Keywords: transcriptional reporters, DNA repair, DNA damage, SOS response

1. Introduction

DNA damage poses a challenge to cells due to the possibilities that DNA lesions can lead to mutations or cell death [1]. DNA damage can form spontaneously or upon environmental exposures, for example to UV radiation and alkylating agents [1]. Alkylating agents are potentially genotoxic due to their ability to react at nucleophilic centers on DNA, forming adducts that can be cytotoxic or mutagenic, causing heritable mutations to occur in DNA, which can lead to cancer [1]. In this work, we probe the cellular effects of the alkylating agents chloroacetaldehyde (CAA) and styrene oxide (SO) in E. coli as a model system. We chose CAA and SO for our assays since they are direct-acting, share a common mechanism (alkylation), have been studied for their genotoxic properties, are readily available, and are important industrially [2–7].

CAA is a carcinogenic metabolite of vinyl chloride, forming several different DNA adducts including the cyclic base adducts 3,N4-ethenocytosine (εC), 1,N6-ethenoadenine (εA), N2,3-ethenoguanine (εG), and 1,N2-ethenoguanine (1,N2-εG), with the A and C cyclic adducts the most predominant, and all of which can be mutagenic [8–10]. The εC adduct mostly produces C to A and C to T mutations, whereas εA results in mainly A to C mutations [10, 11]. In bacterial systems, εG has miscoding properties and can yield G to A transition mutations [10]. Mutagenic signatures of vinyl chloride exposure have been observed in the oncogenes H-ras and K-ras [12]. The εA and εG adducts can be removed by DNA glycosylases as part of the Base Excision Repair (BER) pathway [13, 14]. For example, the εA lesions are excised by the human and E. coli 3-methyladenine-DNA glycosylases and AlkA proteins, respectively [15–17]. E. coli AlkB and its human homologues ABH2 and ABH3 specifically repair base lesions, including the mutagenic exocyclic adducts εC, εA, and 1,N2-εG by using an oxidative dealkylation mechanism known as Direct Repair (DR) [18–21].

SO, the principal metabolite of styrene, is a versatile electrophile that is able to react at various positions on DNA bases [5–7, 22, 23] either through the α- or β-carbon of the epoxide ring, resulting in a diversity of adducts. From studies with nucleosides in vitro, SO has been shown to react at the N7-, N2-, and O6-positions of deoxyguanine (dG), 1- and N6-positions of deoxyadenine (dA), N4-, N3-, and O2-positions of deoxycytosine (dC), and the N3-position of thymine [22, 23]. E. coli strains harboring deletions of several DNA repair genes including the SOS-inducible genes recA and uvrA, the adaptive response genes ada, alkB, and alkA, and the 3-methyladenine repair gene tag were treated with SO and other reactive chemicals to evaluate growth [24]. SO caused extreme sensitivity of the E. coli strain lacking DNA damage repair genes relative to the wild-type strain [24]. Induction of the SOS response as a result of E. coli treated with multiple epoxides including SO was also evaluated using the SOS-Chromotest, which revealed that most of the monosubstituted epoxides including SO resulted in SOS induction [25].

E. coli cells have a variety of mechanisms to repair DNA damage, many of which are regulated by the SOS response [26–28]. The SOS response leads to the LexA-, RecA-dependent upregulation of at least 57 genes, including those involved in DNA repair, DNA damage tolerance, and regulation of the cell cycle [1, 29]. In addition, the E. coli adaptive response is induced when cells are exposed to DNA-damaging alkylating agents and results in the direct reversal of DNA damage. The Ada protein, a DNA alkyltransferase, directly dealkylates damaged DNA and transfers the alkyl group to itself, leading to the expression of four genes: ada, alkB, alkA, and aidB [30, 31]. While human cells lack the LexA-mediated SOS response, most E. coli repair pathways have analogous systems in humans and other organisms [1, 32]. Moreover, many of the responses to genotoxic chemicals are conserved in E. coli and humans, so that interesting results with E. coli can, in turn, suggest areas of DNA repair systems in humans for study [33].

The focus of this work was to determine which E. coli genes contribute to survival upon exposure to CAA and SO. We first analyzed the expression of certain stress response genes upon exposure to each agent, using the established Transcriptional Effect Level Index (TELI) assay [34]. The main advantage of the TELI assay is to help to build better understanding of DNA damage responses and other cellular responses to stresses, by revealing correlations or lack of correlations for further study. Quantitative endpoints such as TELI, which incorporates temporal expression activities of multiple genes and gives more integrated DNA-damage and repair pathway activities, have been shown to be generally correlated with phenotypic genotoxicity endpoints [33–35]. The TELI gene expression library consists of each promoter of interest fused to the gene encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) on a low-copy plasmid; the plasmid-based expression reporters as opposed to chromosomal integration may represent a potential challenge in interpreting the results [36]. Potentially the TELI assay will become useful to characterize in DNA damage responses in cells derived from individuals for different exposures, to learn which exposures are of greatest concern for an individual.

The TELI results of DNA damage responses to CAA and SO then informed our choice of bacterial strains in subsequent experiments. We investigated E. coli cellular survival in response to CAA and SO exposure by determining the sensitivity of a number of E. coli strains, each possessing single or multiple gene deletions. We find that multiple repair processes confer resistance to SO while only a few processes confer resistance to CAA.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Transcriptional Effect Level Index (TELI) Assays

Chloroacetaldehyde (CAA; f.c. 0.5 mg/mL in H2O, TCI America) and styrene oxide (SO; f.c. 1.4 mg/mL in DMSO, TCI America) were prepared at 7x of the final concentratrions used for the TELI assay. A library of transcriptional fusions of the gene encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) to the respective promoters for 114 stress-related genes in E. coli MG1655 was employed in this assay, with detailed information for the library reported elsewhere [34, 36–38]. Within this library, each promoter fusion is expressed from a low-copy plasmid, pUA66 or pUA139, containing a kanamycin (Kan) resistance gene and a fast folding gfpmut2 gene, which allows continuous and real-time measurements of the promotor activities [34, 36]. The transcriptional effect level induced by the alkylating agents was measured according to the published protocol [34]. Quantitative end-point of the time-series response of a given gene, termed as transcriptional effect level index (TELI), is obtained by aggregating the induction of the altered gene expression level normalized over exposure time [34]. The TELI values indicate the relative change in expression of a given promotor upon treatment with alkylating agent relative to untreated control.

2.2. Strain Construction by Genetic Transduction

Knockout strains were obtained from the KEIO collection [39] in which gene deletions are constructed in BW25113; we constructed the AB1157 deletion strains via transduction using bacteriophage P1 [40]. The strains obtained from the E. coli Genetic Stock Center (CGSC) each had a Kan antibiotic resistance marker sequence in place of the gene to be studied (Table 1). The presence of the deletions in AB1157 was confirmed by PCR with primer pairs that amplify the region of interest for analysis by agarose gel electrophoresis and DNA sequencing (Eton and Macrogen, Cambridge, MA). Primer pairs used to verify transductions are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Strains used in this work.

| Bacterial Strain | Relevant Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| AB1157 | thr-1 araC-14 leuB-6(Am) Δ(gpt-proA)62 lacY1 tsx-33 qsr-0 glnV44(AS) galK2(Oc) LAM-Rac-0 hisG4(Oc) rfbC1 mgl-51 rpoS396(Am) rpsL31 kdgK51 xylA5 mtl-1 argE3(Oc) thi-1 | Laboratory stock |

| MG1655 | F−-λ−-ilvG−-rfb-50 rph-1 | Laboratory stock |

| PB108 | AB1157 Δada::kan | PI (JW2201–1) [39] to AB1157, this work |

| PB109 | AB1157 ΔalkB::kan | PI (JW2200–1) [39] to AB1157, this work |

| AB1157 ΔdinB | AB1157 ΔdinB | [41, 42] |

| PB110 | AB1157 ΔdinG::kan | PI (JW0784–1) [39] to AB1157, this work |

| PB130 | AB1157 Δmfd::kan | PI (JW1100–l) [39] to AB1157, this work |

| PB111 | AB1157 Δmug::kan | PI (JW3040–1) [39] to AB1157, this work |

| PB112 | AB1157 ΔmutM::kan | PI (JW3610–2) [39] to AB1157, this work |

| PB113 | AB1157 ΔmutS::kan | PI (JW2703–2) [39] to AB1157, this work |

| PB129 | AB1157 ΔmutY::kan | PI (JW2928–1) [39] to AB1157, this work |

| PB114 | AB1157 Δnfo::kan | PI (JW2146–1) [39] to AB1157, this work |

| PB115 | AB1157 ΔrecA::kan | PI (JW2669–1) [39] to AB1157, this work |

| PB116 | AB1157 ΔrecE::kan | PI (JW1344–1) [39] to AB1157, this work |

| PB101 | AB1157 ΔrecJ::kan | PI (JW2860–1) [39] to AB1157; Graham Walker |

| PB117 | AB1157 ΔrecN::kan | PI (JW5416–1) [39] to AB1157, this work |

| PB118 | AB1157 Δrnt::kan | PI (JW1644–5) [39] to AB1157, this work |

| PB119 | AB1157 ΔruvA::kan | PI (JW1850–2) [39] to AB1157, this work |

| PB120 | AB1157 ΔsbmC::kan | PI (JW1991–2) [39] to AB1157, this work |

| PB121 | AB1157 ΔsulA::kan | PI (JW0941–1) [39] to AB1157, this work |

| PB122 | AB1157 ΔsymE::kan | PI (JW4310–1) [39] to AB1157, this work |

| PB100 | AB1157 ΔumuC | Graham Walker |

| AB1157 ΔumuD | AB1157 ΔumuD | Graham Walker |

| GW8017 | AB1157 ΔumuDC | [43] |

| SEC136 | AB1157ΔdinB ΔumuDC | Susan Cohen; Graham Walker |

| PB123 | AB1157 ΔuvrA | Graham Walker |

| PB124 | AB1157 ΔuvrC::kan | PI (JW1898–l) [39] to AB1157, this work |

| PB125 | AB1157 ΔuvrD::kan | PI (JW3786–5) [39] to AB1157, this work |

| PB126 | AB1157 ΔuvrY::kan | PI (JW1899–1) [39] to AB1157, this work |

| PB127 | AB1157 ΔybfE::kan | PI (JW5816–1) [39] to AB1157, this work |

| PB128 | AB1157 ΔyebG::kan | PI (JW1837–1) [39] to AB1157, this work |

Table 2.

Primers used to verify transductions performed for this work.

| Primer Name | Primer Sequence |

|---|---|

| KanFor1 | CAGTCATAGCCGAATAGCCT |

| KanRev1 | CGGCCACAGTCGATGAATCC |

| ada-check5 | GGAGAAAGCTAAAGAGGTTGTTCG |

| ada-check3 | GGCTGGCAACGTCATTAATATCGC |

| alkB-check5 | CGTGGTGATGGCACACTTTCCG |

| alkB-check3 | CAGACAAGTACAAGAAGTTCCATGC |

| dam-seq5 | CGATCTGAAGTAATCAAGGTTATCTCC |

| dam-seq3 | CCAGCTGCCAGGGCTTTTGCGG |

| dinG-check5 | CGCATTATGTTGGTGGTTATTGCG |

| ding-check3 | GGACTTCACCATTGAGCATATGAGC |

| mfd-seq5 | GGCGATTCAATTTGCTAAACCATGTC |

| mfd-seq3 | GGTGACAGTGTCGGATAGTGCAGG |

| mug-check5 | CCAAGCGATTATGAGTCGCCTGC |

| mug-check3 | CGTAGCTTCCTGGACGATTAATCG |

| mutM-check5 | GCTTTGATGTAACAAAAAACCTCGC |

| mutM-check3 | GCGATGTCACCCATTTCCTGCC |

| mutS-check5 | GCGTACTTGCTTCATAAGCATCACG |

| mutS-check3 | CCCATATATGGCGATAGTGATGGG |

| mutY-seq5 | CCGGATGCAAGCATGATAAGGCC |

| mutY-seq3 | GACCTTCTGCTTCACGTTGCAGG |

| nfo-check5 | CCTGTTAACCCGCTATCATTACCG |

| nfo-check3 | GCTGAATCAGCGGGTTACGCCG |

| recA-check5 | CGTATGCATTGCAGACCTTGTGG |

| recA-check3 | GCGTACCGCACGATCCAACAGG |

| recE-check5 | GCAAGATCATTCACTGAACAAAACG |

| recE-check3 | GCACGGTTTCCCTGAGTTTTTTGC |

| recN-check5 | CCTGATTCGTCGCTGTGATTACC |

| recN-check3 | CGCATAGTGATTTGATTCCTTTTCG |

| rnt-check5 | GGTTATCGCGTTTGTGGAAGATCC |

| rnt-check3 | CCTGAATCATTGCATGTCATCAGGC |

| ruvA-check5 | CCATTTTTCAGTTCATCGAGACACC |

| ruvA-check3 | CCAACATACTCTTCCAGTAATTTGG |

| sbmC-check5 | CCTTTCTTTTGCAGCAGACTGGC |

| sbmC-check3 | GGCAGGAGCGAAAAAATTGAAAGG |

| sulA-check5 | GGTATTCAATTGTGCCCAACG TTGC |

| sulA-check3 | GGATCTGCTCAATATTAACTCTACC |

| symE-check5 | GCATCGCTAATCACAATCACTATTCC |

| symE-check3 | GCTAAGCCTCTATTATCGCTTTCG |

| uvrC-check5 | GCTCAATCTCAGTCCGAAAACGG |

| uvrC-check3 | GGATGACACGGAACAGTGTAAGC |

| uvrD-check5 | CGGTTGGCATCTCTGACCTCGC |

| uvrD-check3 | GGCAACGCTATCCTTTTGTCACC |

| uvrY-check5 | CGTGACCATAACTGTGGACAATCG |

| uvrY-check3 | GCGACATAGATAACCGTACCACCA |

| ybfE-check5 | CGTCGCTATCTCAATGATTAACGC |

| ybfE-check3 | CGGTATTACCGGTGTCGCTGCC |

| yebG-check5 | GCCTAATAACATCACGCGAGTTGC |

| yebG-check3 | CCGACTTGCTGGTTTCATTATTGG |

As reported in [44]

2.3. Survival assays

E. coli strains were exposed separately to CAA at a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL prepared in sterile water or SO at 1.4 mg/mL prepared in dimethylformamide. The concentrations of each agent to be used for dosing were determined using WT AB1157 and PB109 (AB1157 ΔalkB) and represent the concentration at which moderate sensitivity was observed in PB109 relative to WT. Overnight cultures in LB (RPI or Affymetrix) were diluted 1:50 and incubated at 37 °C for 35–40 min. Once the OD600 reached 0.1 – 0.3, 1.5 mL of OD600 = 0.5 culture was harvested by centrifugation for 10 min at 3.8K RCF followed by removal of supernatant and resuspension of the pellets in 1 mL fresh LB. Next, 900 μL was transferred to the stock (S) microcentrifuge tube and 90 μL from the “S” tube transferred to the time 0 or control tube without treatment (T0). A 90-μL aliquot of alkylating agent at the selected concentration was added to each (S) tube, mixed, and incubated at 37 °C with shaking. The T0 samples were centrifuged for 3 min at 6K RCF, followed by removal of supernatant and resuspension of the pellet in 500 μL 0.85% saline, after which the samples were stored on ice. Time points were taken at 30 min (T30), 60 min (T60), and 90 min (T90) and were processed as the T0 time point. Serial dilutions (10-fold) of each time point were plated on LB-agar plates which were then incubated at 37 °C overnight. The data described herein represent the average of at least three trials; error bars represent standard deviation.

3. Results

In order to determine the cellular pathways responsible for tolerance to CAA and SO, we determined the expression of stress response genes and assessed the survival of a number of E. coli strains containing deletions of genes that were likely to confer survival. The strains chosen for this work contained deletions of genes that represented a range of DNA repair functions as well as some of the genes implicated in cellular responses to CAA and SO from TELI experiments.

3.1. Transcriptional Effect Level Index (TELI) Assays reveal stress responses to alkylating agents

The TELI assay is a toxicogenomic assay that indicates which genes show changed expression in response to specific treatments [34]. TELI values determined for each stress-related gene category can indicate the involvement of different stress response and damage repair pathways [34]. In the case of the TELI assay, the promoters of specific stress-related genes are fused to the gfp gene on a low-copy plasimid. The accumulation of GFP fluorescence in the strains serves as a reporter for the rate of transcription initiation from the promoter region.

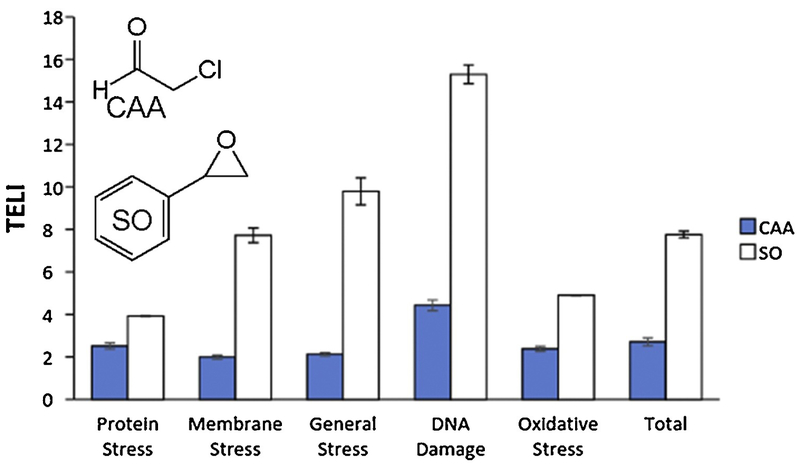

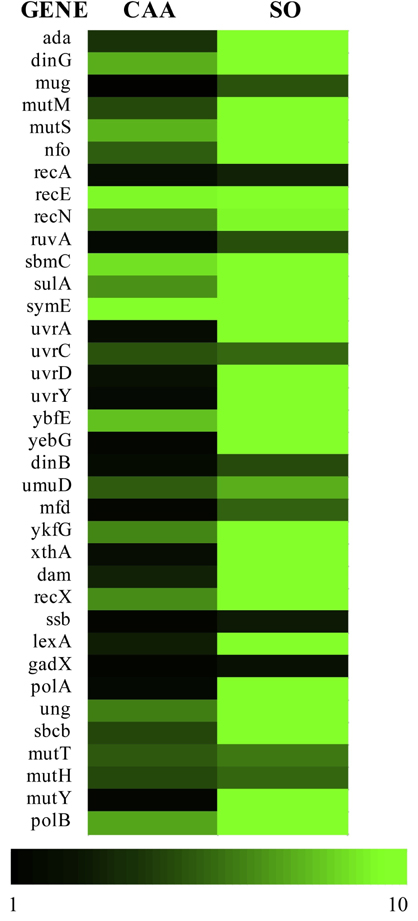

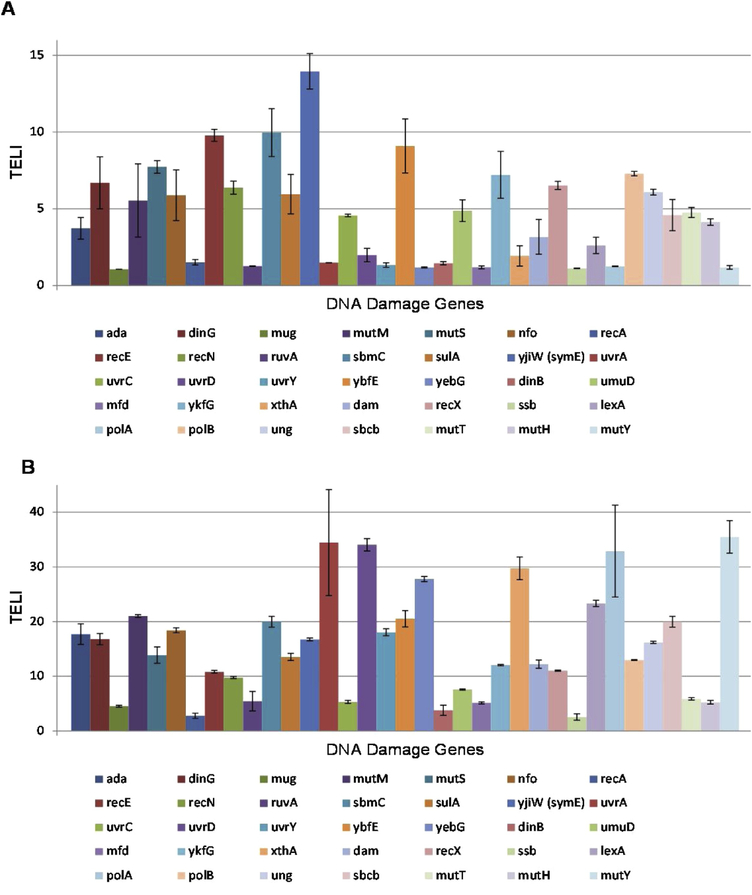

The TELI assay utilizes a library of transcriptional fusions of GFP to the promoters of 114 E. coli stress-related genes, encompassing several categories including protein stress (including clpB, dnaK, entC, grpE, and lon), membrane stress (including amiC, emrA, and marR), oxidative stress (including oxyR, soxR, and sodA), general stress (including uspA and rpoE), and DNA damage (including lexA, recA, umuD, and uvrA) [34], revealing those promoters that respond when cells are exposed to, in this work, the alkylating agents CAA and SO. Overall, CAA and SO induce multiple stress responses and yield higher TELI values in the DNA damage category compared to the other stress categories, which is consistent with the known abilities of both agents to damage DNA (Figure 1) [3, 5–7]. The expression of multiple genes (Figures 2 and 3) in the DNA damage stress category of the TELI library was induced upon exposure to either CAA or SO, with SO exposure inducing expression of more genes and at higher expression levels than CAA.

Figure 1.

Overall TELI response versus various stress categories upon exposure to CAA (0.5 mg/mL in H2O) and SO (1.4 mg/mL in DMSO). Values represent the average of TELI values for all genes in the category indicated.

Figure 2.

TELI fluorescence heat map of DNA damage and DNA stress response genes from E. coli MG1655 exposed to CAA (0.5 mg/mL in H2O) and SO (1.4 mg/mL in DMSO). The TELI values range from 1 (black = promoter of gene not upregulated and GFP not produced) to 10 (bright green = promoter of gene upregulated and GFP produced), as indicated.

Figure 3.

TELI versus DNA damage gene promoters from E. coli MG1655 exposed to (A) CAA (0.5 mg/mL in H2O) and (B) SO (1.4 mg/mL in DMSO).

Within the TELI library of 114 stress-related genes employed, there are 36 DNA damage and repair genes represented. Of these 36 genes, we chose a sub-set of 29 genes, as well as three additional genes, that are known to contribute to DNA damage repair pathways and acquired strains lacking these genes for cell survival assays (Table 1). Within the subset of genes chosen for survival assays, ada, dinG, mutM, mutS, mutT, nfo, recE, recN, sbmC, sulA, symE, umuD, uvrC, and ybfE all yielded moderate to high TELI response signals upon exposure to CAA. Upon exposure to SO, as high or higher TELI responses were observed for these genes as well as dam, dinB, mfd, mug, mutY, ruvA, uvrA, uvrD, uvrY, and yebG (Figures 2 and 3). We find that CAA and SO exposure induces genes that play multiple roles in responding to DNA damage, with SO inducing genes that represent a wider range of DNA stress categories and inducing higher expression in general. Furthermore, although expression of the lexA gene was induced weakly by CAA and more strongly by SO, as determined by TELI (Figure 2), it was not selected for sensitivity assays since, as the master regulator of the SOS reponse, deletion of lexA is likely to render difficulties in data interpretation in these experiments [45, 46].

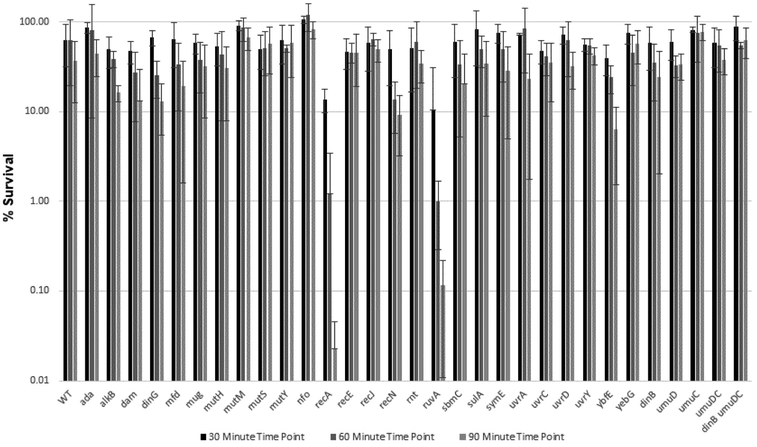

3.2. Survival Assays

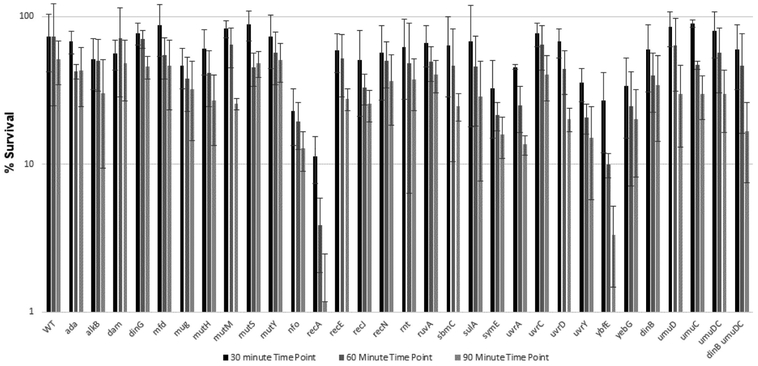

To identify the DNA damage response pathways that contribute to survival upon exposure to CAA and SO, we used a library of E. coli strains harboring gene deletions. We selected a subset of the genes upregulated in the TELI experiments as well as several others likely to contribute to survival (Table 3). The E. coli mutants were assayed versus WT separately for survival upon treatment with CAA (Figure 4) and SO (Figure 5).

Table 3.

Summary of E. coli DNA stress response genes tested here and their functions [49]

| Gene(s)/References | DNA Stress Category | Gene Function |

|---|---|---|

| ada [31] | Adaptive Response (AR) | DNA alkylation repair; O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase |

| alkB [50] | DR and AR | DNA alkylation repair; alpha-ketoglutarate- and Fe(II)-dependent dioxygenase |

| dam [51] | Alkylation | DNA-(adenine-N6)-methyltransferase |

| dinB [52, 53] | Pol IV (SOS) | DNA polymerase IV (Y-family DNA polymerase); translesion DNA synthesis; damage bypass |

| dinG [54] | Recombination repair | ATP-dependent DNA helicase; putative repair and recombination enzyme; unwinding of DNA |

| mfd [55] | Transcription repair coupling factor; translocase | |

| mug [56] | MMR | Stationary phase mismatch/uracil DNA glycosylase |

| mutH [57] | MMR | Methyl-directed mismatch repair |

| mutM [58] | BER | formamidopyrimidine DNA glycosylase; GC to TA |

| mutS [57] | MMR | Methyl-directed mismatch repair protein |

| mutY | BER | Adenine glycosylase, GA repair |

| nfo [59] | Oxidative stress | AP endodeoxyribonuclease IV; member of soxRS regulon; endonuclease IV |

| recA [60] | SOS, recombination repair | Binds ssDNA to form nucleoprotein filament during SOS mutagenesis; homologous recombination |

| recE [61] | Recombination repair | exonuclease VIII, ds DNA exonuclease, 5’ → 3’ specific; recombination and repair |

| recJ [60, 62] | Recombination repair | ssDNA 5’ → 3’ exonuclease; recombination and repair |

| recN [61, 63] | Recombination repair | Recombination and repair |

| rnt [64] | RNA Degradation | RNase T; RNA processing; degrades RNA |

| ruvA [65, 66] | Recombination repair | Drives branch migration of Holliday structures during recombination and repair |

| sbmC [67] | Relieve strain | DNA gyrase inhibitor, SOS regulated |

| sulA [68] | SOS | SOS cell division inhibitor; Inhibits cell division and FtsZ ring formation; LexA regulon |

| symE [69, 70] | unknown | Hypothetical protein; RNA antitoxin |

| umuDC [52, 53] | SOS | SOS mutagenesis and repair; DNA polymerase V (Y-family DNA polymerase complex); DNA translesion synthesis; damage bypass |

| uvrA [71] | NER | excision nuclease subunit A; Component of UvrABC Nucleotide Excision Repair Complex |

| uvrC [71] | NER | Excision nuclease subunit C; repair of UV damage to DNA |

| uvrD [71] | NER | DNA-dependent ATPase I and helicase II; Component of UvrABC Nucleotide Excision Repair Complex; unwinds forked DNA structures; dismantles the RecA nucleoprotein filament |

| uvrY [72] | DNA Binding | DNA binding response regulator; controls the expression of csrB/C sRNAs; hydrogen peroxide resistance |

| xthA [73] | DNA Repair | Exodeoxyribonuclease III and AP endodeoxyribonuclease VI; RNase H activity; DNA repair |

| ybfE [74] | SOS | LexA-regulated protein; unknown function |

| yebG [75] | SOS | DNA damage-inducible gene; SOS regulon |

Figure 4.

Summary bar graph of percent survival of E. coli WT AB1157 and AB1157 mutant strains versus time upon 30 min, 60 min, and 90 min exposure to 0.5 mg/mL CAA.

Figure 5.

Summary bar graph of percent survival of E. coli WT AB1157 and AB1157 mutant strains versus time upon 30 min, 60 min, and 90 min exposure to 1.4 mg/mL SO.

Upon exposure to CAA, strains lacking recA and ruvA showed the lowest survival; both genes contribute to homologous recombination, although RecA is also important for SOS induction [29] and translesion synthesis by E. coli pol V [47, 48]. Strains lacking ybfE, an SOS-induced gene of unknown function, and recN, which is involved in recombination repair (Table 3), also showed a decrease in survival, although the observed change for recN was not statistically significant. Strikingly, none of the other strains tested exhibited sensitivity to CAA.

Upon treatment with SO, a number of the strains tested exhibited sensitivity. The strain lacking recA yielded the greatest sensitivity to SO, as it did upon CAA treatment. The strain lacking ybfE was also highly sensitive to SO. Deletion of both Y-family DNA polymerase genes, dinB and umuDC, resulted in modest sensitivity to SO. Strains lacking the uvrA or uvrD genes involved in nucleotide excision repair were sensitive to SO, as were strains lacking the DNA glycosylase mutM and nucleases nfo, recE, and recJ. Deletion of the SOS-regulated genes sbmC, symE and yebG also conferred sensitivity to SO.

We observed a general correlation between TELI and survival assays in that SO induced expression of more genes and to a higher level than CAA and more mutant strains were sensitive to SO than to CAA. Several of the genes we studied were observed by TELI to be highly expressed upon exposure to SO and their deletion conferred sensitivity to SO, including strains lacking recE, symE, and sbmC. Notable exceptions for both CAA and SO were recA, ruvA, dinG and umuD. Both recA and ruvA promoters showed low to undetectable expression in the TELI assay (Figure 1); the strain lacking recA was sensitive to both CAA and SO but ΔruvA was only sensitive to CAA (Figure 5). Whereas both dinG and umuD promoters showed activity in the TELI assay, deletion of either of these genes did not confer sensitivity to CAA or SO. The lack of cellular sensivity could be due to the ability of DNA repair pathways to compensate for each other; since these pathways are criticial for survival, a given lesion can often be repaired by more than one route [1]. In addition, deletion of umuD, a translesion synthesis manager protein [76], alone does not cause sensitivity, but a strain lacking genes for both Y-family translesion DNA polymerases umuDC and dinB is moderately sensitive to SO.

4. Discussion

In this work, we used assays of gene expression and cellular sensitivity to identify repair pathways that play pivotal roles in tolerance to DNA damage induced by the alkylating agents CAA and SO. There are several types of DNA damage caused by the alkylating agents studied here. For example, DNA exposure to CAA has been shown to result in formation of the mutagenic exocyclic adducts εC, εA, εG, and 1,N2-εG [8–11, 19, 77]. E. coli AlkB repairs εC, εA, and 1,N2-εG adducts, similar to the repair profile of the human homolog ABH2 [9, 18–21, 78, 79]. The εC and 1,N2-εG lesions are also repaired by base excision repair proteins double-stranded uracil-DNA glycosylase (UDG) and mug, respectively; 1,N2-εG does not appear to be a substrate for Nfo or AlkB [9, 15]. Some DNA glycosylase genes, such as ung and mutM, exhibit altered expression upon cellular exposure to CAA (Figure 2). We observed only modest sensitivity to CAA of a strain lacking alkB, which could be due to the presence of compensating repair pathways. Indeed, the most sensitive strains to CAA here were those lacking recombination repair genes recA and ruvA.

SO forms adducts via either its epoxide α- or β-position at multiple sites of dA, dC, and dG, and at the N3 position of dT [5–7, 22, 23]. The dG adduct can undergo subsequent depurination, resulting in an abasic site [80], consistent with the finding that endonuclease III is involved in repair of SO-induced damage in human cells [81], and our observation that several BER-associated genes showed TELI responses upon exposure to SO (Figure 2). In E. coli, elevated SO concentrations promoted acetic acid formation, membrane permeability, and cell lysis, and a reduction in colony growth and formation, which together are likely the reasons for the more robust stress response to SO in the TELI experiment [82]. It was observed in in vivo bacterial replication assays that DNA containing most SO lesions could be replicated, but DNA containing some of these same lesions could not be replicated with purified replicative DNA polymerases [83, 84]. This previous work was carried out prior to the discovery of the biochemical activity of Y-family translesion DNA polymerases; indeed, we observed that deletion of both Y-family polymerases umuDC and dinB sensitizes cells to SO (Figure 5), suggestion that they play a role in bypass of SO-induced DNA lesions.

Deletions of the genes recA, involved in recombination and repair, and ybfE, a gene of unknown function, conferred sensitivity to both CAA and SO. Although recA promoter activity was essentially unchanged upon CAA exposure, there was low but detectable expression upon exposure to SO. A similar observation was made for the ruvA promoter, which showed slightly higher expression when exposed to SO than to CAA. One possible reason for the lack of recA promoter activity in TELI is that recA is one of the most abundant proteins in the cell and thus it has been proposed that sufficient RecA is present for some of its functions without induction [85]. Similarly, of two related carcinogens, N-hydroxy-N-2-aminofluorene and acetoxy-N-2-acetylaminofluorene, only the latter induced RecA [86]. Using TELI, similar effects were observed with two genotoxic nanomaterials, nano-silver and nano-TiO2_a, in which nano-silver did not induce RecA whereas nano-TiO-2_a led to robust induction [33–35]. Although the promoters of recA and ruvA are not appreciably activated by exposure to either agent, the roles of recA and ruvA in recombination and DNA repair [60, 65, 66, 87] appear to be important for survival upon exposure to these agents. The strains lacking recA and ybfE showed the largest degree of sensitivity upon exposure to both agents. The critical and multifaceted roles of these genes, particularly recA, in stress resposes are also highlighted by their contributions to survival upon UV- and X-irradation, as well as exposure to a number of antibiotics and other damaging agents [88–93]. Although the function of ybfE is unknown, the decrease in cell survival observed for the mutant strain when exposed to either agent suggests that it plays a key role in DNA damage tolerance; indeed, the ybfE gene is known to be regulated by LexA [74, 94] and was upregulated by both CAA and SO.

Although there was little to no expression observed by TELI of the recA and ruvA genes upon CAA exposure, other specific repair pathways were induced by both CAA and SO and include the SOS-inducible gene sulA, the DNA repair gene ykfG, the mismatch repair gene mutS, the recombination and repair genes recE and recN, the DNA gyrase inhibitor sbmC, and the SOS-induced putative antitoxin symE. The recE gene encodes exonuclease VIII and digests DNA in the 5′ → 3′ direction, yielding dsDNA with 3′- ssDNA overhangs and recE mutations cause recB, recC, and sbcA mutants to become recombination-deficient [95]. By TELI, the recE promoter showed increased expression upon exposure to both CAA and SO. We further find by TELI that the sbcB promoter shows increased expression upon exposure to both agents; sbcB encodes exonuclease I, which is involved in the RecBCD pathway [96]. We find that the recN promoter showed increased TELI response, but the strain harboring a recN deletion was not sensitive to either CAA or SO. Taken together, this work implicates recombination repair in cellular responses to CAA and SO.

The promoters of the glycosylases mutM, mug, and the nuclease nfo each showed increased TELI responses upon exposure to CAA and SO and the strains lacking mutM and nfo showed sensitivity to SO. Increased expression of the mug, mutM, and nfo promotors as determined by TELI and the lowered survival of the mutM and nfo mutants suggests the involvement of BER in repair of SO-induced lesions, consistent with the finding that SO-induced lesions lead to formation of abasic sites [80]. Finally, deletion of uvrA and uvrD, both involved in NER, resulted in sensitivity to SO, presumably due to the presence of bulky styrene adducts and consistent with a previous report that lack of uvrA confers modest sensitivity to SO [97]. Like recA, genes involved in NER also confer survival upon exposure to a wide range of agents including radiation and several antibiotics [88–92].

In summary, we confirmed that a broader range of DNA damage genes were expressed upon exposure to SO, with a number of the same genes expressed upon exposure to CAA by the TELI assay. The survival assays also yielded a broader range of DNA damage response genes that confer resistance toward SO, which could be due to the greater diversity of DNA damage induced by SO. The goal of this work was to identify genes important for responses to the two alkylating agents CAA and SO and to point out aspects of DNA damage responses that need further study. For example, the lack of correlation between TELI gene expression and cellular sensitivity for dinG is unexpected, and deletion of ybfE, a gene of unknown function, confers sensitivity to both CAA and SO. In the long term, the technology might be applied to exposure of cell cultures from individuals to learn which chemicals are most toxic on an individual basis.

Highlights.

Numerous stress responses are induced by chloroacetaldehyde and styrene oxide

DNA damage is most prominent category of stress responses

Strains lacking recA, ruvA, and ybfE are sensitive to chloroacetaldehyde

Strains lacking recA, mutM, nfo, uvrA, uvrD, ybfE are sensitive to styrene oxide

Acknowledgments

Susan Cohen and Graham Walker of MIT are acknowledged for the gift of several strains used in this work. Bilyana Koleva is acknowledged for technical assistance. Rhodes Technologies is acknowledged for their generous support of M.M.M. This research was supported by the American Cancer Society (RSG-12-161-01-DMC to P.J.B.), ROUTES Fellowships (NIEHS 1R25ES0254960–01) to A.A. and J.A., the Northeastern University Office of the Provost for Undergraduate Research and Creative Endeavors Awards to C.J. and S.B. and an Honors Assistantship to K.W. This study was also supported by National Science Foundation (NSF, CBET-1437257, CBET-1810769), National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS, PROTECT 3P42ES017109–07 and CRECE 1P50ES026049–02), and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA, CRECE 83615501) to A.Z.G.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

This work was carried out while M.M.M. was an employee of Rhodes Technologies, which played no role in the design, execution, or interpretation of the experiments reported here.

References

- 1.Friedberg EC, Walker GC, Siede W, Wood RD, Schultz RA, and Ellenberger T, DNA Repair and Mutagenesis. 2nd ed. 2006, ASM Press. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCann J, Simmon V, Streitwieser D, and Ames BN, Mutagenicity of chloroacetaldehyde, a possible metabolic product of 1,2-dichloroethane (ethylene dichloride), chloroethanol (ethylene chlorohydrin), vinyl chloride, and cyclophosphamide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 72 (1975) 3190–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartsch H, Barbin A, Marion MJ, Nair J, and Guichard Y, Formation, detection, and role in carcinogenesis of ethenobases in DNA. Drug Metab Rev, 26 (1994) 349–71. 10.3109/03602539409029802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nair J, Barbin A, Guichard Y, and Bartsch H, 1,N6-ethenodeoxyadenosine and 3,N4-ethenodeoxycytine in liver DNA from humans and untreated rodents detected by immunoaffinity/32P-postlabeling. Carcinogenesis, 16 (1995) 613–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koskinen M, Calebiro D, and Hemminki K, Styrene oxide-induced 2’-deoxycytidine adducts: implications for the mutagenicity of styrene oxide. Chem Biol Interact, 126 (2000) 201–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koskinen M and Plna K, Specific DNA adducts induced by some mono-substituted epoxides in vitro and in vivo. Chem Biol Interact, 129 (2000) 209–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koskinen M, Vodicka P, and Hemminki K, Adenine N3 is a main alkylation site of styrene oxide in double-stranded DNA. Chem Biol Interact, 124 (2000) 13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guengerich FP, Min KS, Persmark M, Kim MS, Humphreys WG, and Cmarik JL, DNA Adducts: Identification and Significance. 1994, International Agency for research on Cancer; Lyon, France. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shrivastav N, Li D, and Essigmann JM, Chemical biology of mutagenesis and DNA repair: cellular responses to DNA alkylation. Carcinogenesis, 31 (2010) 59–70. 10.1093/carcin/bgp262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swenberg JA, Bogdanffy MS, Ham A, Holt S, Kim A, Morinello EJ, Ranasinghe A, Scheller N, and U. P.B., Formation and Repair of DNA adducts in vinyl chloride- and vinyl fluoride-induced carcinogenesis, in Singer B and Bartsch H, Ed.Exocyclic DNA Adducts in Mutagensis and Carcinogenesis, International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France: 1999, p. 29–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basu AK, Wood ML, Niedernhofer LJ, Ramos LA, and Essigmann JM, Mutagenic and genotoxic effects of three vinyl chloride-induced DNA lesions: 1,N6-ethenoadenine, 3,N4-ethenocytosine, and 4-amino-5-(imidazol-2-yl)imidazole. Biochemistry, 32 (1993) 12793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brandt-Rauf PW, Li Y, Long C, Monaco R, Kovvali G, and Marion MJ, Plastics and carcinogenesis: The example of vinyl chloride. J Carcinog, 11 (2012) 5 10.4103/1477-3163.93700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oesch F, Adler S, Rettelbach R, and Doerjer G, The Role of Cyclic and Nucleic Acid Adducts in Carcinogenesis and Mutagenesis. 1986, Oxford University Press; New York. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singer B, Antoccia A, Basu AK, Dosanjh MK, Fraenkel-Conrat H, Gallagher PE, Kusmierek JT, Qiu ZH, and Rydberg B, Both purified human 1,N6-ethenoadenine-binding protein and purified human 3-methyladenine-DNA glycosylase act on 1,N6-ethenoadenine and 3-methyladenine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 89 (1992) 9386–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saparbaev M and Laval J, 3,N4-ethenocytosine, a highly mutagenic adduct, is a primary substrate for Escherichia coli double-stranded uracil-DNA glycosylase and human mismatch-specific thymine-DNA glycosylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 95 (1998) 8508–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saparbaev M, Kleibl K, and Laval J, Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, rat and human 3-methyladenine DNA glycosylases repair 1,N6-ethenoadenine when present in DNA. Nucleic Acids Res, 23 (1995) 3750–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matijasevic Z, Sekiguchi M, and Ludlum DB, Release of N2,3-ethenoguanine from chloroacetaldehyde-treated DNA by Escherichia coli 3-methyladenine DNA glycosylase II. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 89 (1992) 9331–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mishina Y and He C, Oxidative dealkylation DNA repair mediated by the mononuclear non-heme iron AlkB proteins. J Inorg Biochem, 100 (2006) 670–8. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2005.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim MY, Zhou X, Delaney JC, Taghizadeh K, Dedon PC, Essigmann JM, and Wogan GN, AlkB influences the chloroacetaldehyde-induced mutation spectra and toxicity in the pSP189 supF shuttle vector. Chem Res Toxicol, 20 (2007) 1075–83. 10.1021/tx700167v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maciejewska AM, Ruszel KP, Nieminuszczy J, Lewicka J, Sokolowska B, Grzesiuk E, and Kusmierek JT, Chloroacetaldehyde-induced mutagenesis in Escherichia coli: the role of AlkB protein in repair of 3,N(4)-ethenocytosine and 3,N(4)-alpha-hydroxyethanocytosine. Mutat Res, 684 (2010) 24–34. 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maciejewska AM, Sokolowska B, Nowicki A, and Kusmierek JT, The role of AlkB protein in repair of 1,N(6)-ethenoadenine in Escherichia coli cells. Mutagenesis, 26 (2011) 401–6. 10.1093/mutage/geq107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Savela K, Hesso A, and Hemminki K, Characterization of reaction products between styrene oxide and deoxynucleosides and DNA. Chem Biol Interact, 60 (1986) 235–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schrader W and Linscheid M, Styrene oxide DNA adducts: in vitro reaction and sensitive detection of modified oligonucleotides using capillary zone electrophoresis interfaced to electrospray mass spectrometry. Arch Toxicol, 71 (1997) 588–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harder A, Escher BI, Landini P, Tobler NB, and Schwarzenbach RP, Evaluation of bioanalytical assays for toxicity assessment and mode of toxic action classification of reactive chemicals. Environ Sci Technol, 37 (2003) 4962–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von der Hude W, Seelbach A, and Basler A, Epoxides: comparison of the induction of SOS repair in Escherichia coli PQ37 and the bacterial mutagenicity in the Ames test. Mutat Res, 231 (1990) 205–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janion C, Inducible SOS response system of DNA repair and mutagenesis in Escherichia coli. Int J Biol Sci, 4 (2008) 338–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kreuzer KN, DNA damage responses in prokaryotes: regulating gene expression, modulating growth patterns, and manipulating replication forks. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 5 (2013) a012674 10.1101/cshperspect.a012674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baharoglu Z and Mazel D, SOS, the formidable strategy of bacteria against aggressions. FEMS Microbiol Rev, 38 (2014) 1126–45. 10.1111/1574-6976.12077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simmons LA, Foti JJ, Cohen SE, and Walker GC, Chapter 5.4.3. The SOS Regulatory Network, in Bock A, et al. , Ed.EcoSal--Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, ASM Press: Washington, D.C. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sedgwick B, Bates PA, Paik J, Jacobs SC, and Lindahl T, Repair of alkylated DNA: recent advances. DNA Repair (Amst), 6 (2007) 429–42. 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mielecki D, Wrzesinski M, and Grzesiuk E, Inducible repair of alkylated DNA in microorganisms. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res, 763 (2015) 294–305. 10.1016/j.mrrev.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanawalt PC, Cooper PK, Ganesan AK, and Smith CA, DNA repair in bacteria and mammalian cells. Annu Rev Biochem, 48 (1979) 783–836. 10.1146/annurev.bi.48.070179.004031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lan J, Gou N, Gao C, He M, and Gu AZ, Comparative and mechanistic genotoxicity assessment of nanomaterials via a quantitative toxicogenomics approach across multiple species. Environ Sci Technol, 48 (2014) 12937–45. 10.1021/es503065q [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gou N and Gu AZ, A new Transcriptional Effect Level Index (TELI) for toxicogenomics-based toxicity assessment. Environ Sci Technol, 45 (2011) 5410–7. 10.1021/es200455p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lan J, Gou N, Rahman SM, Gao C, He M, and Gu AZ, A Quantitative Toxicogenomics Assay for High-throughput and Mechanistic Genotoxicity Assessment and Screening of Environmental Pollutants. Environ Sci Technol, 50 (2016) 3202–14. 10.1021/acs.est.5b05097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaslaver A, Bren A, Ronen M, Itzkovitz S, Kikoin I, Shavit S, Liebermeister W, Surette MG, and Alon U, A comprehensive library of fluorescent transcriptional reporters for Escherichia coli. Nat Methods, 3 (2006) 623–8. 10.1038/nmeth895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zaslaver A, Kaplan S, Bren A, Jinich A, Mayo A, Dekel E, Alon U, and Itzkovitz S, Invariant distribution of promoter activities in Escherichia coli. PLoS Comput Biol, 5 (2009) e1000545 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gou N, Onnis-Hayden A, and Gu AZ, Mechanistic toxicity assessment of nanomaterials by whole-cell-array stress genes expression analysis. Environ Sci Technol, 44 (2010) 5964–70. 10.1021/es100679f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, and Mori H, Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol, 2 (2006) 2006 0008. 10.1038/msb4100050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller JH, A Short Course in Bacterial Genetics. 1 ed. 1992, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jarosz DF, Godoy VG, Delaney JC, Essigmann JM, and Walker GC, A single amino acid governs enhanced activity of DinB DNA polymerases on damaged templates. Nature, 439 (2006) 225–8. 10.1038/nature04318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim SR, Maenhaut-Michel G, Yamada M, Yamamoto Y, Matsui K, Sofuni T, Nohmi T, and Ohmori H, Multiple pathways for SOS-induced mutagenesis in Escherichia coli: an overexpression of dinB/dinP results in strongly enhancing mutagenesis in the absence of any exogenous treatment to damage DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 94 (1997) 13792–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guzzo A, Lee MH, Oda K, and Walker GC, Analysis of the region between amino acids 30 and 42 of intact UmuD by a monocysteine approach. J Bacteriol, 178 (1996) 7295–7303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Datsenko KA and Wanner BL, One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 97 (2000) 6640–5. 10.1073/pnas.120163297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Witkin EM, Ultraviolet mutagenesis and inducible DNA repair in Escherichia coli. Bacteriol Rev, 40 (1976) 869–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Little JW, Mount DW, and Yanisch-Perron CR, Purified lexA protein is a repressor of the recA and lexA genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 78 (1981) 4199–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schlacher K, Leslie K, Wyman C, Woodgate R, Cox MM, and Goodman MF, DNA polymerase V and RecA protein, a minimal mutasome. Mol Cell, 17 (2005) 561–72. 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reuven NB, Arad G, Maor-Shoshani A, and Livneh Z, The mutagenesis protein UmuC is a DNA polymerase activated by UmuD’, RecA, and SSB and is specialized for translesion replication. J Biol Chem, 274 (1999) 31763–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu JC, Sherlock G, Siegele DA, Aleksander SA, Ball CA, Demeter J, Gouni S, Holland TA, Karp PD, Lewis JE, Liles NM, McIntosh BK, Mi H, Muruganujan A, Wymore F, Thomas PD, and Altman T, PortEco: a resource for exploring bacterial biology through high-throughput data and analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res, 42 (2014) D677–84. 10.1093/nar/gkt1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fedeles BI, Singh V, Delaney JC, Li D, and Essigmann JM, The AlkB Family of Fe(II)/alpha-Ketoglutarate-dependent Dioxygenases: Repairing Nucleic Acid Alkylation Damage and Beyond. J Biol Chem, 290 (2015) 20734–42. 10.1074/jbc.R115.656462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marinus MG, DNA methylation and mutator genes in Escherichia coli K-12. Mutat Res, 705 (2010) 71–6. 10.1016/j.mrrev.2010.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fuchs RP and Fujii S, Translesion DNA synthesis and mutagenesis in prokaryotes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 5 (2013) a012682 10.1101/cshperspect.a012682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goodman MF and Woodgate R, Translesion DNA polymerases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 5 (2013) a010363 10.1101/cshperspect.a010363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Voloshin ON and Camerini-Otero RD, The DinG protein from Escherichia coli is a structure-specific helicase. J Biol Chem, 282 (2007) 18437–47. 10.1074/jbc.M700376200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Selby CP, Mfd Protein and Transcription-Repair Coupling in Escherichia coli. Photochem Photobiol, 93 (2017) 280–295. 10.1111/php.12675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grippon S, Zhao Q, Robinson T, Marshall JJ, O’Neill RJ, Manning H, Kennedy G, Dunsby C, Neil M, Halford SE, French PM, and Baldwin GS, Differential modes of DNA binding by mismatch uracil DNA glycosylase from Escherichia coli: implications for abasic lesion processing and enzyme communication in the base excision repair pathway. Nucleic Acids Res, 39 (2011) 2593–603. 10.1093/nar/gkq913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Modrich P, Mechanisms in E coli and Human Mismatch Repair (Nobel Lecture). Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 55 (2016) 8490–501. 10.1002/anie.201601412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jiricny J, DNA repair: how MutM finds the needle in a haystack. Curr Biol, 20 (2010) R145–7. 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Laval J, Jurado J, Saparbaev M, and Sidorkina O, Antimutagenic role of base-excision repair enzymes upon free radical-induced DNA damage. Mutat Res, 402 (1998) 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bell JC and Kowalczykowski SC, RecA: Regulation and Mechanism of a Molecular Search Engine. Trends Biochem Sci, 41 (2016) 491–507. 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kowalczykowski SC, Dixon DA, Eggleston AK, Lauder SD, and Rehrauer WM, Biochemistry of homologous recombination in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev, 58 (1994) 401–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morimatsu K and Kowalczykowski SC, RecQ helicase and RecJ nuclease provide complementary functions to resect DNA for homologous recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 111 (2014) E5133–42. 10.1073/pnas.1420009111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Odsbu I and Skarstad K, DNA compaction in the early part of the SOS response is dependent on RecN and RecA. Microbiology, 160 (2014) 872–82. 10.1099/mic.0.075051-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lovett ST, The DNA Exonucleases of Escherichia coli. EcoSal Plus, 4 (2011). 10.1128/ecosalplus.4.4.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yamada K, Ariyoshi M, and Morikawa K, Three-dimensional structural views of branch migration and resolution in DNA homologous recombination. Curr Opin Struct Biol, 14 (2004) 130–7. 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Iwasa T, Han YW, Hiramatsu R, Yokota H, Nakao K, Yokokawa R, Ono T, and Harada Y, Synergistic effect of ATP for RuvA-RuvB-Holliday junction DNA complex formation. Sci Rep, 5 (2015) 18177 10.1038/srep18177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baquero MR, Bouzon M, Varea J, and Moreno F, sbmC, a stationary-phase induced SOS Escherichia coli gene, whose product protects cells from the DNA replication inhibitor microcin B17. Mol Microbiol, 18 (1995) 301–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Higashitani A, Higashitani N, and Horiuchi K, A cell division inhibitor SulA of Escherichia coli directly interacts with FtsZ through GTP hydrolysis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 209 (1995) 198–204. 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kawano M, Divergently overlapping cis-encoded antisense RNA regulating toxin-antitoxin systems from E. coli: hok/sok, ldr/rdl, symE/symR. RNA Biol, 9 (2012) 1520–7. 10.4161/rna.22757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gerdes K and Wagner EG, RNA antitoxins. Curr Opin Microbiol, 10 (2007) 117–24. 10.1016/j.mib.2007.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hu J, Selby CP, Adar S, Adebali O, and Sancar A, Molecular mechanisms and genomic maps of DNA excision repair in Escherichia coli and humans. J Biol Chem, 292 (2017) 15588–15597. 10.1074/jbc.R117.807453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pernestig AK, Melefors O, and Georgellis D, Identification of UvrY as the cognate response regulator for the BarA sensor kinase in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem, 276 (2001) 225–31. 10.1074/jbc.M001550200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Centore RC, Lestini R, and Sandler SJ, XthA (Exonuclease III) regulates loading of RecA onto DNA substrates in log phase Escherichia coli cells. Mol Microbiol, 67 (2008) 88–101. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06026.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Courcelle J, Khodursky A, Peter B, Brown PO, and Hanawalt PC, Comparative gene expression profiles following UV exposure in wild-type and SOS-deficient Escherichia coli. Genetics, 158 (2001) 41–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Oh TJ and Kim IG, Identification of genetic factors altering the SOS induction of DNA damage-inducible yebG gene in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett, 177 (1999) 271–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ollivierre JN, Fang J, and Beuning PJ, The Roles of UmuD in Regulating Mutagenesis. J Nucleic Acids, 2010 (2010). 10.4061/2010/947680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Langouet S, Muller M, and Guengerich FP, Misincorporation of dNTPs opposite 1,N2-ethenoguanine and 5,6,7,9-tetrahydro-7-hydroxy-9-oxoimidazo[1,2-a]purine in oligonucleotides by Escherichia coli polymerases I exo- and II exo-, T7 polymerase exo-, human immunodeficiency virus-1 reverse transcriptase, and rat polymerase beta. Biochemistry, 36 (1997) 6069–79. 10.1021/bi962526v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Delaney JC, Smeester L, Wong C, Frick LE, Taghizadeh K, Wishnok JS, Drennan CL, Samson LD, and Essigmann JM, AlkB reverses etheno DNA lesions caused by lipid oxidation in vitro and in vivo. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 12 (2005) 855–60. 10.1038/nsmb996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zdzalik D, Domanska A, Prorok P, Kosicki K, van den Born E, Falnes PO, Rizzo CJ, Guengerich FP, and Tudek B, Differential repair of etheno-DNA adducts by bacterial and human AlkB proteins. DNA Repair (Amst), 30 (2015) 1–10. 10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.02.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vodicka P and Hemminki K, Depurination and imidazole ring-opening in nucleosides and DNA alkylated by styrene oxide. Chem Biol Interact, 68 (1988) 117–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kohlerova R and Stetina R, The repair of DNA damage induced in human peripheral lymphocytes with styrene oxide. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove), 46 (2003) 95–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Park JB, Buhler B, Habicher T, Hauer B, Panke S, Witholt B, and Schmid A, The efficiency of recombinant Escherichia coli as biocatalyst for stereospecific epoxidation. Biotechnol Bioeng, 95 (2006) 501–12. 10.1002/bit.21037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Latham GJ, McNees AG, De Corte B, Harris CM, Harris TM, O’Donnell M, and Lloyd RS, Comparison of the efficiency of synthesis past single bulky DNA adducts in vivo and in vitro by the polymerase III holoenzyme. Chem Res Toxicol, 9 (1996) 1167–75. 10.1021/tx9600558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Latham GJ, Zhou L, Harris CM, Harris TM, and Lloyd RS, The replication fate of R- and S-styrene oxide adducts on adenine N6 is dependent on both the chirality of the lesion and the local sequence context. J Biol Chem, 268 (1993) 23427–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Salles B and Paoletti C, Control of UV induction of recA protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 80 (1983) 65–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Salles B, Lang MC, Freund AM, Paoletti C, Daune M, and Fuchs RP, Different levels of induction of RecA protein in E. coli (PQ 10) after treatment with two related carcinogens. Nucleic Acids Res, 11 (1983) 5235–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cox MM, Regulation of bacterial RecA protein function. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol, 42 (2007) 41–63. 10.1080/10409230701260258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Al Mamun AA, Lombardo MJ, Shee C, Lisewski AM, Gonzalez C, Lin D, Nehring RB, Saint-Ruf C, Gibson JL, Frisch RL, Lichtarge O, Hastings PJ, and Rosenberg SM, Identity and function of a large gene network underlying mutagenic repair of DNA breaks. Science, 338 (2012) 1344–8. 10.1126/science.1226683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Becket E, Chen F, Tamae C, and Miller JH, Determination of hypersensitivity to genotoxic agents among Escherichia coli single gene knockout mutants. DNA Repair (Amst), 9 (2010) 949–57. 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Byrne RT, Chen SH, Wood EA, Cabot EL, and Cox MM, Escherichia coli genes and pathways involved in surviving extreme exposure to ionizing radiation. J Bacteriol, 196 (2014) 3534–45. 10.1128/JB.01589-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Liu A, Tran L, Becket E, Lee K, Chinn L, Park E, Tran K, and Miller JH, Antibiotic sensitivity profiles determined with an Escherichia coli gene knockout collection: generating an antibiotic bar code. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 54 (2010) 1393–403. 10.1128/AAC.00906-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sargentini NJ, Gularte NP, and Hudman DA, Screen for genes involved in radiation survival of Escherichia coli and construction of a reference database. Mutat Res, 793–794 (2016) 1–14. 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2016.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Klitgaard RN, Jana B, Guardabassi L, Nielsen KL, and Lobner-Olesen A, DNA Damage Repair and Drug Efflux as Potential Targets for Reversing Low or Intermediate Ciprofloxacin Resistance in E. coli K-12. Front Microbiol, 9 (2018) 1438 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fernandez De Henestrosa AR, Ogi T, Aoyagi S, Chafin D, Hayes JJ, Ohmori H, and Woodgate R, Identification of additional genes belonging to the LexA regulon in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol, 35 (2000) 1560–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Smith GR, Homologous recombination in E coli: multiple pathways for multiple reasons. Cell, 58 (1989) 807–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Miesel L and Roth JR, Evidence that SbcB and RecF pathway functions contribute to RecBCD-dependent transductional recombination. J Bacteriol, 178 (1996) 3146–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Backendorf C, Brandsma JA, Kartasova T, and van de Putte P, In vivo regulation of the uvrA gene: role of the “−10” and “−35” promoter regions. Nucleic Acids Res, 11 (1983) 5795–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]