Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of long-term low salt diet on blood pressure and its underlying mechanisms.

Methods

Male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats were divided into normal salt diet group (0.4%) and low salt diet group (0.04%). Blood pressure was measured with the non-invasive tail-cuff method. The contractile response of isolated mesenteric arteries was measured using a small vessel myograph. The effects on renal function of the intrarenal arterial infusion of candesartan (10 µg/kg/min), an angiotensin II receptor type 1 (AT1R) antagonist, were also measured. The expressions of renal AT1R and mesenteric arterial α1A, α1B, and α1D adrenergic receptors were quantified by immunoblotting. Plasma levels of angiotensin II were also measured.

Results

Systolic blood pressure was significantly increased after 8 weeks of low salt diet. There were no obvious differences in the renal structure between the low and normal salt diet groups. However, the plasma angiotensin II levels and renal AT1R expression were higher in low than normal salt diet group. The intrarenal arterial infusion of candesartan increased urine flow and sodium excretion to a greater extent in the low than normal salt diet group. The expressions of α1A and α1D, but not α1B, adrenergic receptors, and phenylephrine-induced contraction were increased in mesenteric arteries from the low salt, relative to the normal salt diet group.

Conclusion

Activation of the renin-angiotensin and sympathetic nervous systems may be involved in the pathogenesis of long-term low salt diet-induced hypertension.

Keywords: Hypertension, low salt diet, renin-angiotensin system, sympathetic nervous system, sodium excretion, vascular contraction

Introduction

Hypertension is one of the most important risk factors for cardiovascular diseases, such as left heart failure and myocardial infarction, and renal disease. Decreasing the prevalence of hypertension may provide the greatest reduction in premature cardiovascular disease-specific deaths in most regions of the world (1). Previous studies have suggested that high sodium intake can lead to cardiovascular disease, including hypertension (2). Moreover, salt-sensitive individuals on high salt intake are more likely to develop not only hypertension but also kidney injury related to renal inflammation and interstitial fibrosis (3). To this end, the reduction in sodium intake is recommended to prevent cardiovascular and kidney disease, and stroke (4).

Guidelines in the treatment of hypertension include a reduction in sodium intake (5,6). However, there are several studies showing that low sodium intake may not always be beneficial in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases (7–13). A low sodium intake has been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events and death, regardless of blood pressure levels (7,10). Some studies have found that urinary sodium excretion less than 3 g per day (presumably reflecting the sodium intake) did not decrease further the systolic blood pressure but actually tended to increase the diastolic blood pressure in subjects with or without hypertension (11). In both normotensive and hypertensive subjects, a low sodium intake can cause insulin resistance and increase in plasma or serum renin, aldosterone, epinephrine, and norepinephrine levels (8–10). However, there are only a few studies in humans (14) and in animal models dealing with the increase in blood pressure caused by low salt diet (15–17). Therefore, the present study was designed to investigate the effect of a low sodium diet (0.04%) on blood pressure and to determine the mechanisms underlying the effect of this diet in normotensive Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats.

Methods

Animal experiments

Six-week-old male SD rats from Daping Hospital Animal Center were randomly divided into two groups. One group was fed a normal NaCl diet (0.4%) and the other group was fed a low NaCl diet (0.04%), for 8 weeks. The rats were housed in plastic cages and given tap water to drink. All procedures were approved by the Daping Hospital Animal Use and Care Committee. All experiments conformed to the guidelines of the ethical use of animals, and all efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and reduce the number of animals used.

Non-invasive blood pressure measurement

The computerized non-invasive tail-cuff manometry system (MODEL MK-2000, Muromachikikai Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) was used to measure the systolic and diastolic blood pressure of conscious SD rats (18). The blood pressures were measured for 15 min between 8:00 AM and 12:00 PM in rats individually restrained in a clear acrylic restrainer at an ambient temperature of 37°C. The average of five blood pressure recordings for each rat was taken as the blood pressure at that particular time. To ensure the reliability of the measurements, the rats were trained for one week to acclimatize them to the procedure.

After the measurement of blood pressure, the rats were then sacrificed under pentobarbital anesthesia (60 mg/kg). The kidneys and mesenteric arteries were removed quickly, lysed in a lysis buffer, sonicated, placed on ice for 1 h and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatants were stored at −70°C until subjected to western blot analysis.

Renal histology

The kidneys, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin, were cut into 4-µm-thick sagittal sections and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The renal histology was studied using an optical microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Plasma angiotensin II detection

At the end of the eight-weeks of normal or low salt intake, and after the injection of pentobarbital, blood was collected. The plasma levels of angiotensin II were measured with a commercially available kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China).

Preparation and study of small resistance arteries

Male SD rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg body weight). The entire mesenteric bed was removed carefully and placed in ice-cold physiological salt solution (PSS). The mesenteric artery was dissected from the surrounding fat and connective tissues. Third-order branches of the superior mesenteric artery (diameter of 250 ± 20 µm) were cut into approximately 2 mm long ring segments, and then mounted on 40 µm stainless-steel wires in an isometric Mulvany-Halpern small-vessel myograph (model 620M, J.P. Trading, Science Park, Aarhus, Denmark).

The mesenteric rings were bathed in PSS at 37°C and continuously bubbled with 95% oxygen and 5% carbon dioxide. All dissections were performed with extreme care to protect the endothelium from inadvertent damage. The mesenteric rings were contracted with phenylephrine and high-potassium PSS(KPSS, 125 mM) to obtain the maximal response. Then, the response curves to phenylephrine, an α1 adrenoreceptor agonist, were measured by a cumulative concentration-dependent protocol (10−9 to 10−5 M) (19,20).

Renal arterial perfusion

The rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneally; Sigma) and tracheotomized (PE-240) to facilitate breathing. For measurement of systemic arterial pressure, catheters (PE-50) were placed into the carotid artery and connected to a pressure transducer (Grass Instrument, Quincy, MA). The left jugular vein was catheterized with PE-50 tubing to infuse normal saline for fluid replacement (see below). A midline abdominal incision was made, the right suprarenal artery was catheterized (PE-10), and the vehicle (saline) or drugs were infused at a rate of 40 µl/h. Both the right and left ureters were catheterized (PE-10) for urine collection. The duration of the surgical preparation was about 60 min. To maintain a stable fluid volume, 5% albumin was infused to replace the blood extracted during each period and normal saline solution, 1% body weight per hour, was infused to replace insensible fluid loss. Rats were allowed to stabilize for 120 min after surgery prior to the suprarenal arterial infusions. For the determination of candesartan-mediated diuresis and natriuresis, the rats were allowed to stabilized for 120 min after surgery, followed by five consecutive 40-min collection periods. During the first collection period, considered as basal, vehicle alone was infused through the right suprarenal artery. This was followed by three collection periods during which time candesartan (10 µg/kg/min, i. v.), an angiotensin II receptor type 1 (AT1R) antagonist, was infused. This was followed by a recovery period during which time only vehicle was infused. Blood samples, 200 µl, replaced by equal volume of 5% albumin, were collected at the end of each period (21,22). Sodium concentrations in the urine samples were measured by a flame photometer 480 (Ciba Corning Diagnostics, Norwood, MA).

Immunoblotting

Mesenteric arteries and kidney from SD rats were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer (5 mL/g tissue) (20 Mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4; 2 mM EDTA, pH 8.0; 2 mM EGTA; 100 mM NaCl; 10µg/ml leupeptin; 10 µg/ml aprotinin; 2 mM phenylmethyllsulfonyl fluoride; and 1% NP-40), sonicated, kept on ice for 1 h, and centrifuged at 16,000g for 30 min. After measuring the protein concentrations, the proteins were boiled in sample buffer at 95°C for 5 min. The proteins in the samples were separated in 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The blots were blocked overnight with 5% nonfat dry milk in phosphate-buffered saline with Tween 20 (PBST, 0.05% Tween-20 in 10 mmol/L phosphate buffered saline) at 4°C with constant shaking, then incubated with AT1R (1:400), α1A receptor (1:200), α1B receptor (1:200), and α1D receptor (1:200) antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) overnight at 4°C. These antibodies were validated in our previous report and those of others (23,24). The membranes were washed with PBST and then incubated with infrared-labeled secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The bound complex was detected using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). The images were analyzed using the Odyssey Application Software to obtain the integrated intensities.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SEM and categorical variables as percentages, unless otherwise stated. Comparison between two groups was made by paired t-test and comparison among groups was made by factorial ANOVA with Holm-Sidak test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Low salt diet increases the blood pressure of SD rats

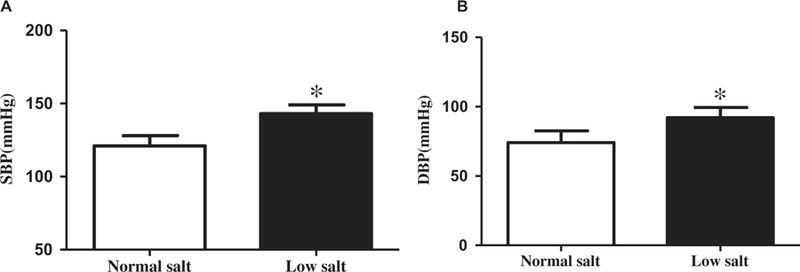

To investigate the effect of a low salt diet on the blood pressure, SD rats were randomly divided into low salt (0.04% NaCl) diet group and normal salt (0.4% NaCl) diet group. After 8 weeks, the systolic and diastolic blood pressures of conscious SD rats were measured using a non-invasive tail-cuff manometry system (18). The results showed that the blood pressures of the low salt diet group (SBP: 143 ± 6.0 mmHg, DBP: 92 ± 7.4 mmHg) were significantly higher than the normal salt diet group (SBP: 121 ± 7.0 mmHg, DBP: 74 ± 8.5 mmHg) (Figures 1(a) and 1(b)).

Figure 1. The regulation of low salt diet on the blood pressure.

SD rats were randomly divided into low and normal salt diet groups. After 8 weeks on the diet, blood pressures were measured by a non-invasive tail-cuff manometry system. The systolic blood pressure (A) and diastolic blood pressure (B) in conscious SD rats fed with low or normal salt diet for 8 weeks are shown (*P < 0.05 vs. normal salt diet, n = 24/group).

Low salt diet increases renal AT1R expression and function

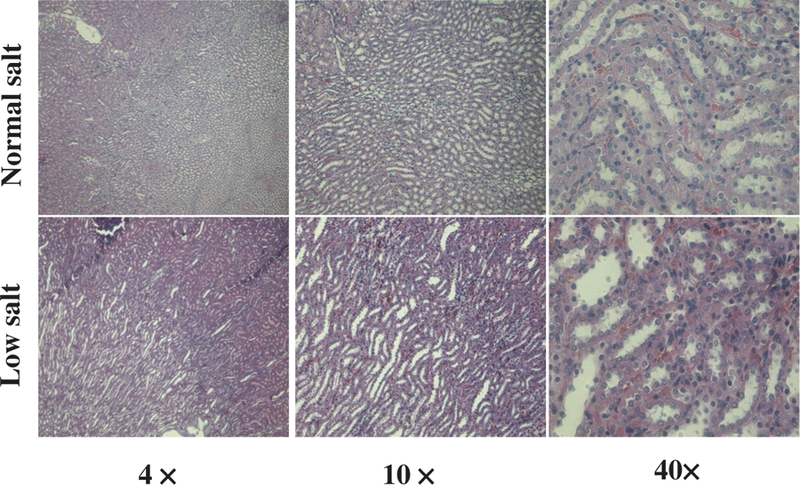

The kidney plays an important role in the long-term control of blood pressure and is the major organ involved in the regulation of sodium homeostasis (25). First, we determined whether or not 8 weeks of low salt diet altered renal histology. The histological analyses showed no obvious differences in the gross structure of the kidneys between low salt diet group and normal salt diet group (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Effect of low salt diet on the renal histology.

Renal histological analysis was performed on hematoxylin and eosin-stained kidney samples from the SD rats fed low or normal salt diet for 8 weeks.

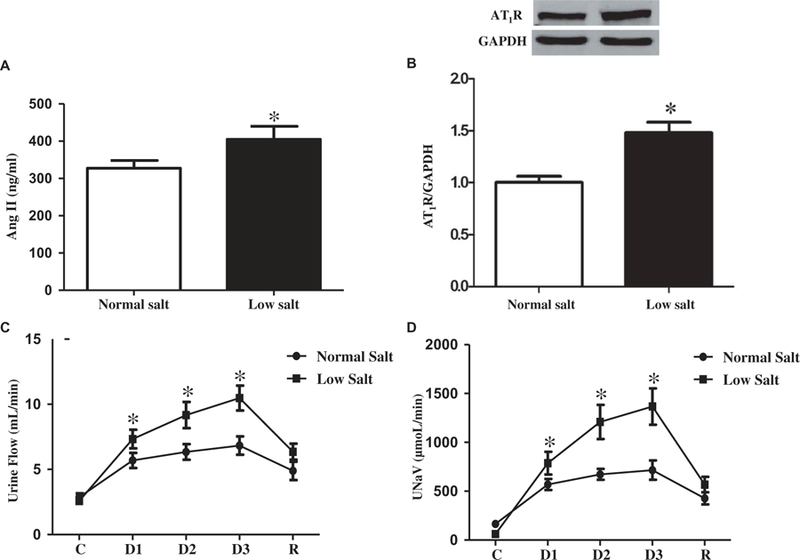

After 8 weeks on low or normal salt diet, the plasma angiotensin II levels of the low salt diet group were higher than the levels in the normal salt diet group (Figure 3(a)). The renal AT1R protein expression was also greater in the low salt than the normal diet group (Figure 3(b)). The increased renal expression of AT1R was also reflected by the increased effects of the intrarenal arterial infusion of the AT1R antagonist, candesartan. The right intrarenal arterial infusion of candesartan increased urine flow and sodium excretion (UNaV) to a greater extent in the low salt than normal salt diet group (Figures 3(c) and 3(d)).

Figure 3. Effects of low salt diet on the renin-angiotensin system.

A. Effect of low salt diet on the plasma angiotensin II (Ang II) levels. Plasma angiotensin II levels were quantified in the SD rats fed low or normal salt diet for 8 weeks (*P < 0.05 vs. normal salt diet, n = 12/group). B. Effects of low salt diet on the renal expression of AT1R. AT1R expression in renal cortex homogenates was quantified by immunoblotting in the SD rats fed low or normal salt diet for 8 weeks (*P < 0.05 vs. normal salt diet, n = 8/group). C and D. Effect of candesartan on urine flow and sodium excretion. The SD rats were fed low or normal salt diet for 8 weeks. Then candesartan, an AT1R antagonist, was infused into the right renal artery via the right suprarenal artery in pentobarbital-anesthetized rats. Urine flow (C) and sodium excretion (D) were measured (*P < 0.05 vs. normal salt diet, n = 8–9). C = control, values before candesartan administration, D = values during candesartan administration, R = recovery, values after stopping the candesartan infusion.

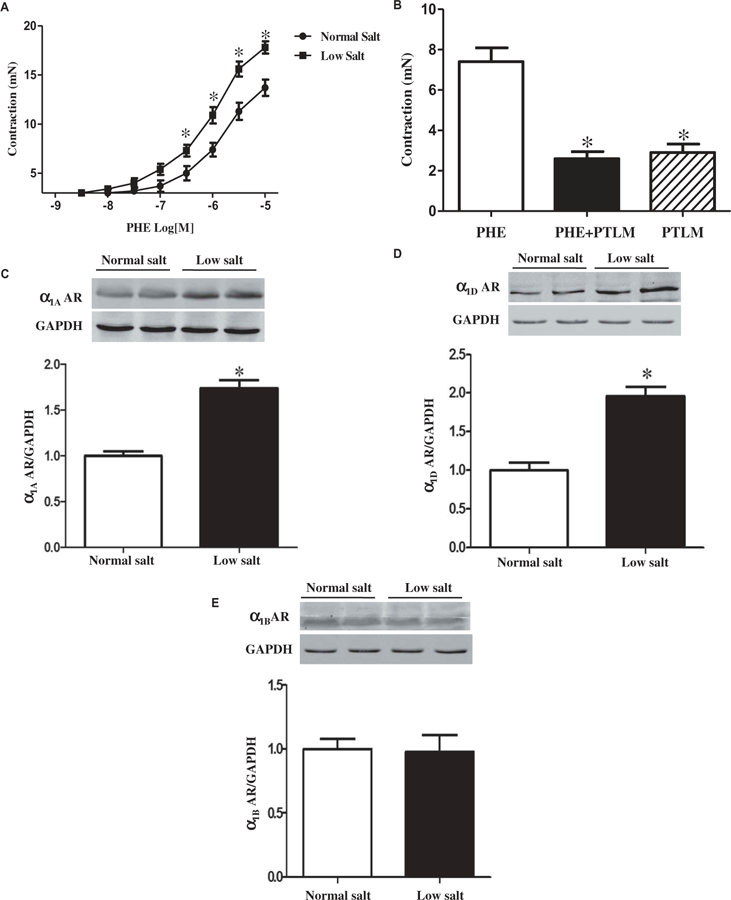

Low salt diet increases the phenylephrine-induced contraction and expression of α1 adrenergic receptors in mesenteric arteries

To determine the effect of low salt diet on vascular reactivity, the third order mesenteric arteries from SD rats were studied. We found that the concentration-dependent contraction of the third-order mesenteric arteries induced by phenylephrine (10−9 M to10−5 M), an α1 adrenergic receptor agonist, was enhanced in rats fed low salt diet, relative to the rats fed normal salt diet (Figure 4(a)). The increased vascular contractility due to phenylephrine in the low salt diet group was via α1 adrenergic receptors because phentolamine, an α1 adrenergic receptor antagonist (10−6 M), which by itself, had no direct contractile effect, completely inhibited the phenylephrine (10−6 M)-mediated contraction in the mesenteric arteries (Figure 4(b)). We also found that the mesenteric arterial expressions of the α1A and α1D, but not α1B, adrenergic receptors were significantly greater in the low salt than normal salt diet group (Figure 4(c), 4(d), and 4(e)). These results suggest that the increased expressions of α1A and α1D adrenergic receptors and their mediated contraction in mesenteric arteries were involved in the low salt diet-induced high blood pressure in the SD rats.

Figure 4. Effects of low salt diet on the sympathetic nervous system.

A. Effects of low salt diet on phenylephrine-induced contraction in mesenteric arteries. The SD rats were fed with low or normal salt diet for 8 weeks. Then, the contraction-response curves to phenylephrine (PHE, 10−9 to 10−5 M), an a1, receptor agonist, were measured by a cumulative concentration-dependent protocol in third-order mesenteric from the SD rats fed low or normal salt diet for 8 weeks (*P < 0.05 vs. normal salt diet, n = 8/group). B. Effect of low salt diet on a1 adrenergic receptor-mediated contraction in third order mesenteric arteries. The contractile responses to the stimulation with the α1 adrenergic receptor agonist, phenylephrine (PHE, 10−6 M) and/or α1 adrenergic receptor antagonist, phentolamine (PTLM, 10−6 M) were measured in third-order mesenteric from SD rats fed low or normal salt diet for 8 weeks (*P < 0.05 vs. normal salt diet, n = 12/group). C, D, and E. Effect of low salt diet on the expression of α1 adrenergic receptors in mesenteric arteries. The expressions of α1A, α1B, and α1D adrenergic receptors (AR) in mesenteric arteries were quantified by immunoblotting in the SD rats fed low or normal salt diet for 8 weeks (*P < 0.05 vs. normal salt diet, n = 8/group).

Discussion

Sodium intake is of great interest because it is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events and mortality (7,26). It has been reported that 1.65 million deaths from cardiovascular causes that occurred in 2010 were attributed to sodium consumption above a reference level of 2.0 g per day (27). A high salt diet is strongly associated with increased blood pressure and cardiovascular disease (2–5,7,11,12,14,26–28). Excessive dietary salt intake induces extensive cardiovascular and renal damage in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) that may be prevented by antihypertensive agents (29). Therefore, high salt intake has always been known as one of the most important risk factors for hypertension. Studies have shown that moderate reduction of salt intake can significantly reduce blood pressure with longterm benefits (2–7,11–14,26–28,30). The 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend consuming less than 2,300 mg sodium per day for persons 14 years, and older and less for persons 2–13 years of age (31). Although a low sodium intake (<2.0 g/d) has been achieved in short-term feeding clinical trials, sustained low sodium intake has not been achieved by any of the longer-term clinical trials (>6-month duration) (30). Current evidence supports the recommendation for moderate sodium intake in the general population (3–5 g/d), targeting the lower end to those with hypertension (32).

There is persistent controversy regarding the relationship between low salt intake and blood pressure or other cardiovascular diseases. Most studies show that dietary salt restriction decreases the blood pressure of hypertensive and normotensive subjects (2–7,11–14,26–28,30,33). However, a “low” sodium intake, <3–5 g/day (assessed by urinary sodium) may not necessarily decrease the blood pressure (11–14). Furthermore, a low sodium intake is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular events in those individuals with and without hypertension whereas high sodium intake is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events in individuals with hypertension (7). These results were confirmed in other two meta-analyses, which reported a J- or U-shaped association between urinary sodium excretion and cardiovascular disease events and mortality (7,10,34,35). Moreover, the inconsistent effects of low salt intake on blood pressure have also been reported in animal studies. A decrease in salt intake has been reported to decrease the blood pressure of SHRs (17) but tended to increase the blood pressure in normotensive rats (16) while other studies have found no effect of low salt diet on blood pressure in SHRs and humans (36,37). The reasons for the different results of low salt intake on blood pressure are not clear but may include the varying definitions of low salt diet, different animal models, and the duration of low salt feeding. Our present study found that compared with the normal salt (0.4% NaCl) diet group, 8 weeks of low salt (0.04% NaCl) diet significantly increased the blood pressure of male SD rats. A recent study showed that salt intake is not associated with development of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in humans with normal blood pressure, whereas both high and low sodium intake are associated with an increased risk of CKD in hypertensive individuals, suggesting that lowering sodium intake to preserve renal function may be effective only in patients with hypertension (38). However, we found no difference in the gross renal morphology between low salt and normal salt diet groups.

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) plays a vital role in the development of hypertension (39). Local RAS exists in different organs, including the kidney. AT1R mediates the vast majority of the renal actions of angiotensin II, including the stimulation of renal sodium transport (40). In many animal models of hypertension, the expression of AT1R is increased in several organs, including the kidney, brain, and adrenal gland (41–43). In the present study, in SD rats, we found that plasma angiotensin II levels and renal AT1R expression were higher in the low than normal salt diet group. The increased renal expression of AT1R may be associated with increased renal AT1R function because the intrarenal infusion of the AT1R antagonist candesartan increased urine flow and sodium excretion to a greater extent in the SD rats fed low than normal salt diet. Thus, the low salt diet may have increased the blood pressure by an overactivation of the RAS, similar to that proposed in some (14,37,44,45) but not in other studies (16).

The sympathetic nervous system also plays an important role in the pathogenesis of hypertension (46–48). Therefore, we investigated the effect of low salt diet on the vascular reactivity induced by sympathetic nervous system. We found that the expressions of the α1A and α1D adrenergic receptors in mesenteric artery were significantly higher in the low salt than normal salt diet group. Moreover, the α1 adrenergic receptor agonist, phenylephrine had a greater contractile effect in the third-order mesenteric arteries from rats fed low than those from rats fed high salt diet. The contractile effect of phenylephrine was inhibited completely by phentolamine, an α1 adrenergic receptor antagonist. These data indicate that α1 adrenergic receptors, presumably α1A and α1D adrenergic receptors, are involved in the low salt diet induced-hypertension in SD rats.

The underlying mechanism may involve inflammation. Low salt diet generates a pro-inflammatory phenotype characterized by an increase in procalcitonin and TNF-α and an opposite effect on an anti-inflammatory cytokine-like adiponectin (49). On the other hand, inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β and TNF-α, induce the expression of α1A-AR in THP-1 monocytic cells; however, the regulation of inflammatory cytokines on the expression of α1-AR may be subtype- and tissue-specific because IL-1-beta and TNF-alpha decrease both α1B-AR and α1D-AR mRNA levels in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (50).

There are varying doses and durations of low salt diet tested in different rat models including normotensive rats, SHRs and other rats. Webb DJ, et al. found that a dietary sodium deprivation (a low sodium diet including 10 mmol Na+ for 5 weeks) raised blood pressure in adult rats (15). Lichardus B, et al. showed that blood pressure in hereditary hypertriglyceridemic rats rose on a low salt diet (without an additional 0.23% NaCl) in the second week, then fell on in the third week, and it increased again in the fourth week (51). Nicolantonio R, et al. reported that low salt diet (0.1% NaCl from weaning until 6 months of age) attenuated the development of hypertension and increased mortality rate in the SHR, but not altered the blood pressure of normotensive WKY rats (52). The low salt (0.01% salt diet for 8 weeks) diet did not affect the systolic blood pressure but increased the heart rate both in WKYs and SHRs (37). Systolic blood pressure was lower and heart rate was higher in male Wistar rats fed a low salt diet (0.06% Na) from weaning to adulthood (53). Low salt diet can also regulate other cardiovascular functions, for example: low-salt diet (0.2% NaCl for 7 days) enhances vascular reactivity in pregnant SD rats (54); low-salt diet (0.03% NaCl for 28 weeks) modulates mesenteric vascular responses via increasing NO bioavailability and COX-2 vasoconstrictor prostanoid production in SHRs (55).

In conclusion, our present study demonstrates that 8 weeks of low salt diet led to the increased blood pressure by activating the RAS and the sympathetic nervous system in male SD rats. However, many questions remain regarding the relationship between low salt diet and blood pressure. For example, the amount of dietary sodium chloride in the junction between increased and decreased blood pressure and cardiovascular diseases remains to be determined. Moreover, it is not known if the varying effects of low salt diet on blood pressure are related to genes or other environmental and dietary factors, such as potassium, calcium, and magnesium intake, among others.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported in part by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31730043, 81570379), Program of Innovative Research Team by National Natural Science Foundation (81721001), and the National Institutes of Health (5R01DK039308–31, 5R01HL092196–10, and 5P01HL074940–11).

Funding

This work was supported by the the National Natural Science Foundation of China [31730043, 81570379]; Program of Innovative Research Team by National Natural Science Foundation [81721001];the National Institutes of Health [5R01DK039308–31, 5R01HL092196–10, and 5P01HL074940];

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. This manuscript is an original contribution not previously published, and not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

References

- 1.Roth GA, Nguyen G, Forouzanfar MH, Mokdad AH, Naghavi M, Murray CJ. Estimates of global and regional premature cardiovascular mortality in 2025. Circulation 2015;132:1270–82. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reddy V, Sridhar A, Machado RF, Chen J. High sodium causes hypertension: evidence from clinical trials and animal experiments. J Integr Med 2015;13:1–8. 10.1016/S2095-4964(15)60155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wei SY, Wang YX, Zhang QF, Zhao SL, Diao TT, Li JS, Qi WR, He YX, Guo XY, Zhang MZ, et al. Multiple mechanisms are involved in salt-sensitive hypertension-induced renal injury and interstitial fibrosis. Sci Rep 2017;7:45952 10.1038/srep45952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appel LJ, Frohlich ED, Hall JE, Pearson TA, Sacco RL, Seals DR, Sacks FM, Smith SC Jr, Vafiadis DK, Van Horn LV. The importance of population-wide sodium reduction as a means to prevent cardiovascular disease and stroke: a call to action from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011;123:1138–43. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820d0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He FJ, Li J, Macgregor GA. Effect of longer term modest salt reduction on blood pressure: cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 2013;346:f1325 10.1136/bmj.f1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension 2018;71:1269–324. 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mente A, O’Donnell M, Rangarajan S, Dagenais G, Lear S, McQueen M, Diaz R, Avezum A, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Lanas F, et al. PURE, EPIDREAM and ONTARGET/TRANSCEND Investigators. Associations of urinary sodium excretion with cardiovascular events in individuals with and without hypertension: a pooled analysis of data from four studies. Lancet 2016;388:465–75. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30467-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oh H, Lee HY, Jun DW, Lee SM. Low salt diet and insulin resistance. Clin Nutr Res 2016;5:1–6. 10.7762/cnr.2016.5.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garg R, Williams GH, Hurwitz S, Brown NJ, Hopkins PN, Adler GK. Low-salt diet increases insulin resistance in healthy subjects. Metabolism 2011;60:965–68. 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graudal NA, Hubeck-Graudal T, Jurgens G. Effects of low sodium diet versus high sodium diet on blood pressure, renin, aldosterone, catecholamines, cholesterol, and triglyceride. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;4:CD004022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mente A, O’Donnell MJ, Rangarajan S, McQueen MJ, Poirier P, Wielgosz A, Morrison H, Li W, Wang X, Di C, et al. ; PURE Investigators. Association of urinary sodium and potassium excretion with blood pressure. N Engl J Med 2014;371:601–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamelas PM, Mente A, Diaz R, Orlandini A, Avezum A, Oliveira G, Lanas F, Seron P, Lopez-Jaramillo P, CamachoLopez P, et al. Association of urinary sodium excretion with blood pressure and cardiovascular clinical events in 17,033 Latin Americans. Am J Hypertens 2016;29:796–805. 10.1093/ajh/hpv195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braam B, Huang X, Cupples WA, Hamza SM. Understanding the two faces of low-salt intake. Curr Hypertens Rep 2017;19:49 10.1007/s11906-017-0744-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Overlack A, Ruppert M, Kolloch R, Göbel B, Kraft K, Diehl J, Schmitt W, Stumpe KO. Divergent hemodynamic and hormonal responses to varying salt intake in normotensive subjects. Hypertension 1993;22(3):331–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Webb DJ, Clark SA, Brown WB, Fraser R, Lever AF, Murray GD, Robertson JI. Dietary sodium deprivation raises blood pressure in the rat but does not produce irreversible hyperaldosteronism. J Hypertens 1987;5:525–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ott CE, Welch WJ, Lorenz JN, Whitescarver SA, Kotchen TA. Effect of salt deprivation on blood pressure in rats. Am J Physiol 1989;256(5 Pt 2):H1426–H1431. 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.5.H1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodge G, Ye VZ, Duggan KA. Dysregulation of angiotensin II synthesis is associated with salt sensitivity in the spontaneous hypertensive rat. Acta Physiol Scand 2002;174:209–15. 10.1046/j.1365-201x.2002.00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ye Z, Lu X, Deng Y, Wang X, Zheng S, Ren H, Zhang M, Chen T, Jose PA, Yang J, et al. In utero exposure to fine particulate matter causes hypertension due to impaired renal dopamine D1 receptor in offspring. Cell Physiol Biochem 2018;46:148–59. 10.1159/000488418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Wang J, Luo H, Chen C, Pei F, Cai Y, Yang X, Wang N, Fu J, Xu Z, et al. Prenatal lipopolysaccharide exposure causes mesenteric vascular dysfunction through the nitric oxide and cyclic guanosine monophosphate pathway in offspring. Free Radic Biol Med 2015;86:322–30. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu J, Han Y, Wang H, Wang Z, Liu Y, Chen X, Cai Y, Guan W, Yang D, Asico LD, et al. Impaired dopamine D1 receptor-mediated vasorelaxation of mesenteric arteries in obese Zucker rats. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2014;13:50 10.1186/1475-2840-13-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang X, Luo H, Chen C, Chen K, Wang J, Cai Y, Zheng S, Yang X, Zhou L, Jose PA, et al. Prenatal lipopolysaccharide exposure results in dysfunction of the renal dopamine D1 receptor in offspring. Free Radic Biol Med 2014;76:242–50. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Asico LD, Zheng S, Villar VA, He D, Zhou L, Zeng C, Jose PA. Gastrin and D1 dopamine receptor interact to induce natriuresis and diuresis. Hypertension 2013;62:927–33. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen K, Deng K, Wang X, Wang Z, Zheng S, Ren H, He D, Han Y, Asico LD, Jose PA, et al. Activation of D4 dopamine receptor decreases angiotensin II type 1 receptor expression in rat renal proximal tubule cells. Hypertension 2015;65:153–60. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hennenberg M, Miersch J, Rutz B, Strittmatter F, Waidelich R, Stief CG, Gratzke C. Noradrenaline induces binding of Clathrin light chain A to a1-adrenoceptors in the human prostate. Prostate 2013;73:715–23. 10.1002/pros.22614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herrera M, Coffman TM. The kidney and hypertension: novel insights from transgenic models. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2012;21:171–78. 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283503068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mills KT, Chen J, Yang W, Appel LJ, Kusek JW, Alper A, Delafontaine P, Keane MG, Mohler E, Ojo A, et al. Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study investigators. Sodium excretion and the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. JAMA 2016;315:2200–10. 10.1001/jama.2016.4447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mozaffarian D, Fahimi S, Singh GM, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Engell RE, Lim S, Danaei G, Ezzati M, Powles J. Global burden of diseases nutrition and chronic diseases expert group. Global sodium consumption and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 2014;371:624–34. 10.1056/NEJMoa1304127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garfinkle MA. Salt and essential hypertension: pathophysiology and implications for treatment. J Am Soc Hypertens 2017;11:385–91. 10.1016/j.jash.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Susic D, Frohlich ED. Telmisartan improves survival and ventricular function in SHR rats with extensive cardiovascular damage induced by dietary salt excess. J Am Soc Hypertens 2014;8:297–302. 10.1016/j.jash.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blumenthal JA, Sherwood A, Smith PJ, Hinderliter A. The role of salt reduction in the management of hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:1597–98. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson SL, King SM, Zhao L, Cogswell ME. Prevalence of excess sodium intake in the United States - NHANES, 2009–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;64:1393–97. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6452a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Donnell M, Mente A, Yusuf S. Sodium intake and cardiovascular health. Circ Res 2015;116:1046–57 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He FJ, Marciniak M, Visagie E, Markandu ND, Anand V, Dalton RN, MacGregor GA. Effect of modest salt reduction on blood pressure, urinary albumin, and pulse wave velocity in white, black, and Asian mild hypertensives. Hypertension 2009;54:482–88. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.133223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Donnell M, Mente A, Rangarajan S, McQueen MJ, Wang X, Liu L, Yan H, Lee SF, Mony P, Devanath A, et al. ; PURE Investigators. Urinary sodium and potassium excretion, mortality, and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med 2014;371:612–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Graudal N, Jürgens G, Baslund B, Alderman MH. Compared with usual sodium intake, low- and excessive-sodium diets are associated with increased mortality: a meta-analysis. Am J Hypertens 2014;27:1129–37. 10.1093/ajh/hpu028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma S, McFann K, Chonchol M, Kendrick J. Dietary sodium and potassium intake is not associated with elevated blood pressure in US adults with no prior history of hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2014;16(6):418–23 10.1111/jch.12312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okamoto C, Hayakawa Y, Aoyama T, Komaki H, Minatoguchi S, Iwasa M, Yamada Y, Kanamori H, Kawasaki M, Nishigaki K, et al. Excessively low salt diet damages the heart through activation of cardiac (pro) renin receptor, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone, and sympatho-adrenal systems in spontaneously hypertensive rats. PLoS One 2017;12:e0189099 10.1371/journal.pone.0189099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoon CY, Noh J, Lee J, Kee YK, Seo C, Lee M, Cha MU, Kim H, Park S, Yun HR, et al. High and low sodium intakes are associated with incident chronic kidney disease in patients with normal renal function and hypertension. Kidney Int 2018;93:921–31. 10.1016/j.kint.2017.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carey RM. The intrarenal renin-angiotensin system in hypertension. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2015;22:204–10. 10.1053/j.ackd.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giani JF, Janjulia T, Taylor B, Bernstein EA, Shah K, Shen XZ, McDonough AA, Bernstein KE, Gonzalez-Villalobos RA. Renal generation of angiotensin II and the pathogenesis of hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep 2014;16:477 10.1007/s11906-014-0477-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Asico L, Zhang X, Jiang J, Cabrera D, Escano CS, Sibley DR, Wang X, Yang Y, Mannon R, Jones JE, et al. Lack of renal dopamine D5 receptors promotes hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;22:82–89. 10.1681/ASN.2010050533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shan Z, Zubcevic J, Shi P, Jun JY, Dong Y, Murҫa TM, Lamont GJ, Cuadra A, Yuan W, Qi Y, et al. Chronic knockdown of the nucleus of the solitary tract AT1 receptors increases blood inflammatory-endothelial progenitor cell ratio and exacerbates hypertension in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension 2013;61:1328–33. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jöhren O, Golsch C, Dendorfer A, Qadri F, Häuser W, Dominiak P. Differential expression of AT1 receptors in the pituitary and adrenal gland of SHR and WKY. Hypertension 2003;41:984–90. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000062466.38314.B7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Montasser ME, Douglas JA, Roy-Gagnon MH, Van Hout CV, Weir MR, Vogel R, Parsa A, Steinle NI, Snitker S, Brereton NH, et al. Determinants of blood pressure response to low-salt intake in a healthy adult population. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2011;13:795–800. 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00523.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suematsu N, Ojaimi C, Recchia FA, Wang Z, Skayian Y, Xu X, Zhang S, Kaminski PM, Sun D, Wolin MS, et al. Potential mechanisms of low-sodium diet-induced cardiac disease: superoxide-NO in the heart. Circ Res 2010;106:593–600. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.208397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grassi G, Mark A, Esler M. The sympathetic nervous system alterations in human hypertension. Circ Res 2015;116:976–90. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DiBona GF. Sympathetic nervous system and hypertension. Hypertension 2013;61:556–60. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Michel MC, Brodde OE, Insel PA. Peripheral adrenergic receptors in hypertension. Hypertension 1990;16:107–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mallamaci F, Leonardis D, Pizzini P, Cutrupi S, Tripepi G, Zoccali C. Procalcitonin and the inflammatory response to salt in essential hypertension: a randomized cross-over clinical trial. J Hypertens 2013;31:1424–30. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328360ddd5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heijnen CJ, Rouppe van der Voort C, van de Pol M, Kavelaars A Cytokines regulate alpha(1)-adrenergic receptor mRNA expression in human monocytic cells and endothelial cells. J Neuroimmunol 2002;125:66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lichardus B, Seböková E, Jezová D, Mitková A, Zemánková A, Földes O, Vrána A, Klimes I. Effect of a low salt diet on blood pressure and vasoactive hormones in the hereditary hypertrigly-ceridemic rat. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1993;683:289–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Di Nicolantonio R, Silvapulle MJ. Blood pressure, salt appetite and mortality of genetically hypertensive and normotensive rats maintained on high and low salt diets from weaning. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 1988;15:741–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ruivo GF, Leandro SM, Do Nascimento CA, Catanozi S, Rocha JC, Furukawa LN, Dolnikoff MS, Quintão EC, Heimann JC. Insulin resistance due to chronic salt restriction is corrected by alpha and beta blockade and by L-arginine. Physiol Behav 2006;88:364–70. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Giardina JB, Cockrell KL, Granger JP, Khalil RA. Low-salt diet enhances vascular reactivity and Ca(2+) entry in pregnant rats with normal and reduced uterine perfusion pressure. Hypertension 2002;39:368–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Travaglia TC, Berger RC, Luz MB, Furieri LB, Ribeiro JR, Vassallo DV, Mill JG, Stefanon I, Vassallo PF. Low-salt diet increases NO bioavailability and COX-2 vasoconstrictor prostanoid production in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Life Sci 2016;145:66–73. 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]