Abstract

The concentration of pasteurized buffalo skim milk (PBSM) employing ultrafiltration (UF) alters the chemical composition of ultrafiltered retentate that adversely affect its proteins and salts equilibrium. Effect of stabilizing salts addition in concentrated milks or retentates was majorly dedicated to their thermal stability only. Therefore, this study was aimed to investigate the effect of disodium phosphate (DSP) addition and homogenization of 2.40 × UF retentate (0.60 protein to total solids ratio) on its ζ-potential, particle size, heat stability, turbidity, pH, viscosity and crossover temperature of storage (G′) and loss (G″) modulus. Concentration of PBSM in UF process, significantly (P < 0.05) increased its percent TS, protein, fat and ash contents, but markedly decreased its lactose content. DSP addition significantly increased (P < 0.05) the ζ-potential, pH, viscosity and particle size in majority of the homogenized and non-homogenized retentates. Homogenized retentates containing 2.5 and 5% DSP exhibited Newtonian and Power law flow behaviour. However, rheological behaviour of non-homogenized retentates containing zero (control), 1 and 4% DSP was best explained by Bingham model. Further, non-homogenized retentates with 0.5, 2, 3, 5% DSP exhibited Newtonian flow, but retentates containing 6 and 7% DSP was best explained by Power law. The correlation among different attributes of DSP added non-homogenized and homogenized samples were also studied. Particle size and turbidity (r = + 0.999, P < 0.05) as well as ζ-potential and crossover temperature of G′ and G″ (r = + 0.999, P < 0.05) showed positive correlation in 4% DSP added non-homogenized retentate.

Keywords: Buffalo milk, Ultrafiltration, Na2HPO4, Homogenization, Physical properties, Rheological modelling

Introduction

Ultrafiltration (UF) is one among the four of conventional pressure driven membrane processes. UF is a well established process for the concentration of milk proteins as it retains milk fat, proteins and insoluble salts in retentate, but allows selective passage of water soluble (lactose, minerals and vitamins) milk components into permeate (Meena et al. 2016, 2017b). The concentration of pasteurized buffalo skimmed milk (PBSM) in UF process increases protein content through decrease in water soluble constituents such as lactose and minerals in ultrafiltered retentate (UFR) samples than the concentrated milks of similar total solids (TS) produced either by evaporation or by reverse osmosis (RO). Singh, (2004) reported that heat stability or heat coagulation time (HCT) is an important property of liquid and concentrated milk that can be measured by various objective and subjective assays (O’Connell and Fox 2011). It is defined as the resistance shown by these samples in minutes towards their heat induced coagulation at 140 °C and 120 °C, respectively. As per Meena et al. (2016), higher HCT values of different milk systems show their suitability towards processing at elevated temperature conditions owing to their appropriate proteins stability and vice versa. Solanki and Gupta (2009) reported that even slight modification either by any process or additives in the delicate salt equilibrium of liquid or concentrated milks, markedly influences their heat stability. Holt et al. (1981) reported that UFR samples exhibit decreased heat stability and altered HCT-pH profile due to shift in delicate ionic equilibrium between serum and micellar proteins as a result of increased concentration of colloidal salt and protein contents during UF concentration.

Patel et al. (1999) reported that increase in TS during UF concentration of buffalo skim milk (BSM) leads to subsequent decrease in its heat stability. The initial HCT (111 min) of BSM (10.59% TS, 4.19% protein) decreased to 11 min in UFR sample (28.39% TS, 21.45% protein) at 120 °C. Solanki and Gupta (2014) reported that ultrafiltered-diafiltered (UF-DF) retentate (29.16%) obtained from BSM, pasteurized at 85 °C and stored overnight below 5 ± 1 °C got destabilized on next morning. Tayal and Sindhu (1983) reported markedly decreased HCT in homogenized concentrated milk with increase in the first stage homogenization pressure from 1000 to 2500 psi and the same was related to disruption in salt equilibrium due to homogenization.

The improvement in HCT of buffalo and cow milk based UF-DF retentates with the addition of different stabilizing salts in isolation and combination such as monosodium phosphate, disodium phosphate and trisodium citrates have been reported by various researchers (Solanki and Gupta 2014; Khatkar et al. 2014; Meena et al. 2016, 2017a, b; 2018). However, stabilizing salt induced changes in other physical properties such as zeta potential, viscosity, particle size, turbidity, and crossover temperature of G′ and G″ as well as rheological properties of buffalo milk based UFR samples have not been studied so far. Generally, stabilizing salts interact with casein micelles and chelate calcium that decrease calcium ion activity based on their calcium binding capacity and subsequently change other physical properties of UFR samples. Some of the changes in these physical properties are interrelated. For example, it is well established fact that stabilizing salts induce dissociation of casein micelles and thereby decreases their turbidity (Orlien et al. 2010). Turbidity measurements have also been used to show that increasing pressure causes a decrease in micellar aggregation at varying temperatures and pH levels (de Kort et al. 2012). Higher absolute values of zeta potential indicates better protein stability.

The charge on protein particle is measured in terms of zeta potential that is defined as the potential difference between dispersion medium and a stationary layer of fluid attached to the particle. A value of 25 mV (positive or negative) is considered as the arbitrary value that separates low charged surfaces from high charged surfaces. A high zeta potential (positive or negative) denotes good stabilization of milk proteins while low zeta potential correlates with their particle aggregation. Zeta potential of milk proteins decreases with increase in either Ca2+ activity or decrease in pH and vice versa. Further, reduction in zeta potential of milk proteins indicates their destabilization which does not lead to curd formation but, merely decreases electrostatic repulsions and may decrease their thermal stability but increases viscosity and particle size. Zeta potential decreases with increase in degree of protein concentration during UF process. Addition of stabilizing salt (such as disodium phosphate) increases the pH and decreases Ca2+ activity of ultrafiltered retentates which induces associated changes in its ζ-potential, particle size, thermal stability, turbidity and viscosity based on added amount.

Improvement in HCT of concentrated milks and RO/UF retentates through different stabilizing salts addition is well established. Sweetsur and Muir (1980), Khatkar et al. (2014) and Meena et al. (2016) have reported improvement in HCT of UF retentates and liquid dairy whitener because of stabilizing salts addition. However, these salts induced changes in other physical properties of non-homogenized and homogenized UF retentates have not been described so far and same has been discussed here under.

It was hypothesized that addition of disodium phosphate in homogenized or non-homogenized retentate will not change its properties. Therefore, this study was aimed to study the effect of disodium phosphate (Na2HPO4, DSP) and homogenization on ζ-potential, particle size, heat stability, turbidity, pH, rheological properties (viscosity and cross over temperature of G′ and G″) and rheological modelling of UFR samples produced from PBSM employing ultrafiltration.

Materials and methods

Ultrafiltration

Fresh buffalo milk was obtained from the Experiential Dairy of ICAR-National Dairy Research Institute, Karnal (India). It was subjected to centrifugal separation followed by its pasteurization at 74 ± 1 °C/15 s to obtain pasteurized buffalo skim milk (PBSM). The PBSM (100 kg) was indirectly heated up to 50 ± 1 °C in a batch system and then ultrafiltered at 50 ± 1 °C in pilot UF plant (CARBOCEP, Tech-Sep., France, tubular module equipped with 50 kDa, ZrO2 membrane having 0.60 m2 membrane surface area) at 1 kg/cm2 constant trans membrane pressure (TMP) as reported by Meena et al. (2016). The quantity of permeate coming out was measured by taking its weight on each concentration factor (CF) as described by Meena et al. (2017a, b). Permeate flux was directly monitored from the flow meter equipped with the UF plant and expressed as l/m2/h (LMH). Mean flux was calculated using the following formula reported by St-Gelais et al. (1991)

All experiments were conducted in triplicate (n = 3).

Concentration factor (CF)

The folds or degree of concentration of PBSM was calculated using the following formula as reported by Smith (2013).

CF were reported as 1 × and 2.40 × , where 1 × represents PBSM while 2.40 × represents the UFR samples obtained after 2 and 2.40 times or folds concentration, respectively.

Sample collection

Representative samples of PBSM (1 ×) and 2.40 × UFR were collected in 500 mL pre-sterilized glass bottles. Total 41 kg retentate was recovered after 2.40 × concentration from 100 kg feed that was further divided into two parts. Retentate obtained after 2.40 × UF concentration was named 2.40 × UFR and treated as control. A part of this was homogenized at 137.89/34.47 bar pressure in double stage homogenizer (make—Goma Engineering Pvt. Ltd., Thane, India, capacity-50 kg/h) and named 2.40 × HUFR. Both samples were stored at 4 ± 1 °C and preserved by the addition of 0.03% (w/w) sodium azide to check the microbial growth till further analysis.

Addition of DSP stabilizing salt

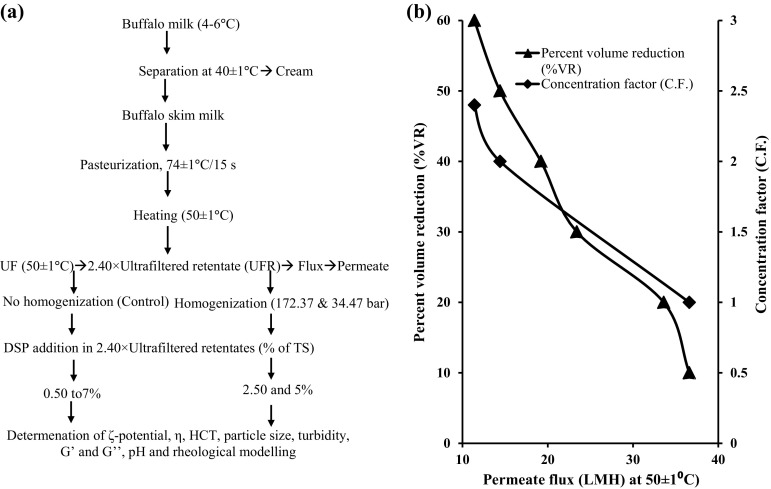

In non-homogenized and homogenized 2.40 × UFR samples, DSP (10% w/v solution) was added in the range of 0.5–7%; 2.5 and 5% of their TS, respectively. The production of UFR samples from PBSM, their homogenization and addition of DSP at different levels in non-homogenized and homogenized samples has been shown in Fig. 1a.

Fig. 1.

a Production of 2.40 × UFR from buffalo skim milk and its treatments and, b change in permeate flux (n = 3) during UF of PBSM as a function of % volume reduction (VR) and concentration factor (C.F.)

Compositional analysis

Total solids (TS) and ash contents of PBSM and ultrafiltered retentates were determined by gravimetric method as described by Indian standards IS: 12333–1997 and IS: 1479 part III-1961, respectively. The crude protein and fat contents of PBSM and ultrafiltered retentates were determined using Macro Kjeldahl Method (IDF 20B: 1993) and Gerber method (IS: 1224 part I-1977), respectively. Lactose contents of the samples were determined by difference by subtracting protein, fat and ash from their respective TS contents as reported earlier (Meena et al. 2016, 2017a, b, 2018).

Measurement of ζ-potential and particle size

ζ-potential and particle size of 1 × and 2.40 × UFR samples were measured in a particle size analyser (Nano ZS90 Zetasizer, Malvern Instruments Ltd, Worcestershire, UK) at 25 °C which works on Laser Doppler Micro-electrophoresis. Prior to the measurement of ζ-potential and particle, PBSM and 2.40 × UFR samples were diluted 100 times in Mili Q water followed by shaking in vortex shaker for 5 min at 20 ± 1 °C ambient temperature.

Measurement of turbidity

For turbidity measurement of ζ-potential and particle, PBSM and 2.40 × UFR samples were diluted 10 times in Mili Q water. Thereafter, their turbidity values were measured at 700 nm using a spectrophotometer at ambient temperature as suggested by de Kort et al. (2012).

Determination of pH and heat coagulation time (HCT)

pH of all samples were measured using Eutech pH meter (model—Cyberscan 1100) of Thermo Scientific at 20 ± 1 °C. The HCT was obtained through measuring the time taken by the samples to form visible clots. HCT of PBSM and DSP added 2.40 × UFR samples was measured at 120 °C using the standard method reported by Tayal and Sindhu (1983) as reported by Meena et al. (2016).

Measurement of rheological properties

Flow behavior of control and other DSP containing 2.40 × UFR samples were performed at 20 °C using Rheometer (MCR 52, Anton Paar, Germany) attached with cone plate CP75-1° (SS) probe at variable shear rate ranging from 1 to 100 s−1 and the obtained rheological data were then fitted to different rheological models such as Bingham, Power law and Herschel–Bulkley as earlier described by Meena et al. (2016).

Dynamic rheological measurements, which are performed under small amplitude oscillatory conditions, are often used to examine short-range interactions in proteins (Tunick 2000). To determine the crossover temperature of storage (G′) and loss (G″) modulus, temperature sweep test was also performed to study the flow behaviour of samples under the influence of operational temperature. The samples were heated from 20 to 90 °C with 5 °C per min increase in temperature at constant shear rate (100 s−1).

Statistical analysis

Results of this study (mean value, n = 3) were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SAS Enterprise guide (5.1, 2012) developed by SAS Institute Inc., North Carolina, USA (SAS 2008). The means were compared using Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (Duncan 1955). Pearson correlation between physical properties of different UFR samples were established using SAS Enterprise guide (5.1, 2012) as earlier reported by Meena et al. (2016) for different attributes of dahi.

Results and discussion

Chemical composition

Chemical composition of PBSM and control (2.40 ×) UFR samples has been reported in Table 1. It is evident from Table 1 that concentration of PBSM in UF process up to 2.40 × concentration significantly (P < 0.05) increased percent TS, protein, fat and ash contents, but significantly (P < 0.05) decreased lactose content of 2.40 × UFR sample compared to 1 × (PBSM). Moreover, on TS (dry matter) basis also protein, fat and ash contents were increased, while lactose content decreased significantly (P < 0.05) in 2.40 × UFR sample that was attributed to passage of water soluble milk components such as lactose, salts, vitamin and non-protein nitrogen substances into permeate through UF membrane. Similar findings have been previously reported by Patil et al. (2018) and Solanki and Gupta (2014).

Table 1.

Proximate composition of PBSM and 2.40 × UFR samples

| Samples | TS | Protein | Lactose | Ash | Fat | pH | Protein | Lactose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | – | Percent of TS | ||||||

| 2.40 × UFR | 18.52a | 11.70a | 4.72b | 1.60a | 0.49a | 6.81a | 63.17a | 25.49b |

| (P/TS = ~0.60) | ± 0.66 | ± 0.40 | ± 0.08 | ± 0.07 | ± 0.15 | ± 0.03 | ± 0.40 | ± 0.08 |

| PBSM | 11.45b | 4.88b | 5.59a | 0.78b | 0.20a | 6.71b | 42.62b | 48.82a |

| ± 0.26 | ± 0.07 | ± 0.14 | ± 0.07 | ± 0.06 | ± 0.03 | ± 0.07 | ± 0.14 | |

Mean ± SE (n = 9), mean values with different superscripts are significantly (P < 0.05) different with each other columnwise

In UF process, highly significant (P < 0.01) increase in the pH of retentates was observed during 1 × (pH 6.71) to 2.40 × UFR (pH 6.81) concentration (Table 1) that might be attributed to the concentration of milk salts (Ca2+, Mg+ and K+) during UF process that changes the cationic profile of milk, based on their association with proteins.

Change in permeate flux with respect to percent volume reduction (%VR) and concentration factor (CF) during UF process has been shown in Fig. 1b. Decrease in membrane flux during UF concentration was observed. UF concentration of PBSM leads to increased TS and protein contents and viscosity in 2.40 × UFR sample. At a constant temperature, permeate flux is inversely proportional to retentate viscosity and it is well established that during UF concentration of PBSM, membrane flux decreases with increase in TS and viscosity of the feed. The observed gradual decrease in flux can be easily explained by membrane concentration polarization and fouling. Decrease in membrane flux has also reported by Patil et al. (2018) and Solanki and Gupta (2014) during concentration of PBSM in UF Process. Flux mean, calculated using the values of initial and final flux for this study was 19.72 LMH.

Effect of Na2HPO4 addition on physical properties of homogenized and non-homogenized 2.40 × UFR samples

Effect of Na2HPO4 addition on ζ-potential, and pH of homogenized and non-homogenized 2.40 × UFR samples

The ζ-potential of 2.40 × UFR (control) sample was minimum (− 17.40 mV) and Na2HPO4 addition significantly (P < 0.01) improved the ζ-potential of all other homogenized and non- homogenized 2.40 × UFR samples as shown in Table 2. The ζ-potential values of 2.40 × UFR samples containing 1% and 3% and 2.40 × HUFR sample with 2.5% Na2HPO4 showed no-significant difference (P > 0.01) with each other. Moreover, ζ-potential of these UFR samples were statistically at par (P > 0.05) with 2.40 × UFR samples containing 0.5%, 5%, 6% and 2.40 × HUFR sample with 5% Na2HPO4 (Table 2). Maximum ζ-potential was observed in 7% Na2HPO4 added 2.40 × UFR sample and the same was statistically at par (P > 0.05) with the ζ-potential values of 0.5% and 4–6% Na2HPO4 containing samples as shown in Table 2. Moreover, at similar (5%) Na2HPO4 addition, homogenized and non- homogenized UFR samples did not showed any difference (P > 0.05) between their ζ-potential values.

Table 2.

Effect of DSP addition on different properties of non-homogenized and homogenized 2.40 × UFR samples

| UFR samples | ζ-potential (mV) | HCT (min) | Viscosity (η, mPa s at 50 s−1, 20 °C) | Particle size (d, nm) | Turbidity (NTU) | Crossover temperature of G′ and G″ (°C) | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.40 × UFR (control) | − 17.40a ± 0.15 | 60.00a ± 0.00 | 5.44 h ± 0.08 | 222.00ef ± 1.53 | 2.26ab ± 0.02 | 54.80 cd ± 0.66 | 6.81d ± 0.01 |

| 2.40 × UFR + 0.5%DSP | − 21.67cde ± 0.15 | 60.00a ± 0.00 | 19.27 g ± 0.43 | 219.63 fg ± 1.04 | 2.27ab ± 0.02 | 53.79d ± 2.02 | 6.81d ± 0.02 |

| 2.40 × UFR + 1%DSP | − 20.43c ± 0.43 | 60.00a ± 0.00 | 18.34 g ± 3.05 | 217.50 g ± 1.08 | 2.24ab ± 0.01 | 59.12bc ± 1.00 | 6.93c ± 0.03 |

| 2.40 × UFR + 2%DSP | − 19.47b ± 0.71 | 60.00a ± 0.00 | 54.98e ± 3.17 | 227.73bc ± 0.43 | 2.53ab ± 0.19 | 55.80 cd ± 1.46 | 7.05ab ± 0.03 |

| 2.40 × UFR + 3%DSP | − 20.77c ± 0.69 | 60.00a ± 0.00 | 31.38f ± 2.20 | 224.80cde ± 0.17 | 2.17ab ± 0.02 | 65.46a ± 1.46 | 7.06ab ± 0.03 |

| 2.40 × UFR + 4%DSP | − 22.62de ± 0.92 | 60.00a ± 0.00 | 155.99d ± 2.64 | 232.13a ± 1.27 | 1.39c ± 0.19 | 54.45 cd ± 1.19 | 7.05ab ± 0.03 |

| 2.40 × UFR + 5%DSP | − 21.67cde ± 0.42 | 60.00a ± 0.00 | 187.43c ± 2.69 | 220.05 fg ± 1.10 | 2.38ab ± 0.17 | 53.14d ± 3.00 | 7.05ab ± 0.02 |

| 2.40 × UFR + 6%DSP | − 21.57cde ± 0.34 | 60.00a ± 0.00 | 316.33a ± 1.20 | 223.87de ± 0.38 | 2.26ab ± 0.27 | 53.45d ± 1.21 | 7.02b ± 0.02 |

| 2.40 × UFR + 7%DSP | − 22.80e ± 0.40 | 60.00a ± 0.00 | 274.67b ± 1.76 | 230.60ab ± 1.18 | 1.98b ± 0.41 | 51.44d ± 1.46 | 7.09a ± 0.01 |

| 2.40 × HUFR + 2.5%DSP | − 20.40c ± 0.25 | 60.00a ± 0.00 | 17.73 g ± 0.64 | 225.46 cd ± 0.67 | 2.20ab ± 0.04 | 62.79ab ± 1.76 | 6.89c ± 0.01 |

| 2.40 × HUFR + 5%DSP | − 21.10 cd ± 0.46 | 60.00a ± 0.00 | 35.50f ± 2.52 | 229.63ab ± 0.61 | 2.63a ± 0.12 | 53.47d ± 0.67 | 6.91c ± 0.01 |

Mean ± S.E. (n = 9), mean values with different superscripts are significantly different (P < 0.05) with each other columnwise

The improvement in ζ-potential values of Na2HPO4 containing homogenized and non- homogenized 2.40 × UFR samples (Table 2) were mainly attributed to the addition of different levels of Na2HPO4 that has been changed their pH and might also have shift the protein-minerals equilibrium which reduces the concentration of calcium ion from colloidal calcium phosphate (CCP) and released specific casein from micelles as earlier reported by Snoeren et al. (1982). Addition of stabilizing salts have been related to the increased repulsions between negatively charged amino acids in casein micelles and hydration of micelles, which leads to increase in zeta potential. Broyard and Gaucheron (2015) reported that more negative values of ζ-potential were related to the reduced interactions between phosphoseryl residue and calcium. Thus, both increase in pH and decrease in calcium ion activity have favourable effect on milk proteins stability as indicated ζ-potential value (Table 2). Increased in ζ-potential of the reconstituted solution of micellar casein isolate (MCI) upon addition (60 mEq/L) of Sodium hexametaphosphate [(NaPO3)6, SHMP] was also reported by de Kort et al. (2012) and the similar action of Na2HPO4 can explain the observed increase in ζ-potential in this study.

Except 2.40 × UFR + 0.5% Na2HPO4 sample, Na2HPO4 addition significantly increased (P < 0.05) the pH values of all other homogenized and non- homogenized 2.40 × UFR samples as shown in Table 2. The pH of control and 2.40 × UFR + 0.5% Na2HPO4 samples were statistically at par (P > 0.05) with each other that was attributed to the addition of Na2HPO4 in smaller (0.5%) quantity and buffering capacity of 2.40 × UFR sample because of its higher (11.52%) protein content. The Na2HPO4 (0.5–7%) addition markedly increased the pH of control (6.81) in the range of 6.89–7.09 (Table 2).

Effect of Na2HPO4 addition on HCT of homogenized and non-homogenized 2.40 × UFR samples

The thermal stability of control, homogenized and non- homogenized 2.40 × UFR samples were determined in terms of their HCT as shown in Table 2. The HCT of all these samples were markedly higher (60 min) and showed no-significant difference (P > 0.05) with each other. Moreover, up to 60 min, heat induced coagulation was not seen in any of these samples. Thereafter, the test was discontinued. Such, higher HCT in all these samples might be attributed to lower concentration (2.40 ×) of PBSM in UF process. Usually, addition of sodium or potassium phosphate such as Na2HPO4 causes perception of colloidal of calcium phosphate that subsequently decreases the concentration of soluble calcium and calcium ions, responsible for improved HCT values of UFR retentates (Deeth and Lewis 2016).

Effect of Na2HPO4 addition on viscosity, particle size and turbidity of homogenized and non-homogenized 2.40 × UFR samples

The viscosity of control sample was significantly lower (P < 0.05) compared all Na2HPO4 added homogenized and non-homogenized 2.40 × UFR samples as shown in Table 2. The relation between shear stress and shear rate of different samples has been shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Relation between shear stress and shear rate of control and treated samples

The addition of Na2HPO4 in 2.40 × UFR samples in the 2–7% range, significantly increased (P < 0.05) their viscosity values compared to control sample having minimum viscosity as shown in Table 2. Viscosity values of 0.5 and 1% Na2HPO4 containing 2.40 × UFR samples were significantly higher (P < 0.05) than control sample, but it was statistically at par (P > 0.05) with each other. This increase in viscosity values of Na2HPO4 containing UFR samples were attributed to the interactions between Na2HPO4 and casein micelles that lead to swelling of casein micelles (i.e. increased voluminosity) due to dissociation of casein micelles as Na2HPO4 is known as a mild calcium chelator (de Kort et al. 2012). They also reported that addition of calcium chelators are often added to dairy products to improve their heat stability, but also increases their viscosity through interactions with the casein proteins. Moreover, viscosity is majorly a function of casein micelles particle size and the same can easily explain the gradual increase in viscosity values of UFR samples with subsequent increase in levels of added Na2HPO4 in the range of 2–7%. Thus, addition of more (particularly at 4–7%) Na2HPO4 leads to higher viscosities because of its severe interactions with milk proteins and vice versa. Homogenized 2.40 × UFR samples exhibited significantly lower (P < 0.05) viscosity than non-homogenized samples containing similar (5%) Na2HPO4 (Table 2) that might be attributed to their lower pH and applied homogenization as it is known to reduce viscosity.

In comparison to particle size of control sample, the 1% Na2HPO4 added 2.40 × UFR sample exhibited significantly lower (P < 0.05) particle size, but 2, 4 and 7% Na2HPO4 added non-homogenized and both homogenized 2.40 × UFR samples showed significantly higher (P < 0.05) particle size. Moreover, values of particle size of 0.5, 3, 5 and 6% Na2HPO4 containing samples were statistically at par (P > 0.05) with the particle size of control sample as shown in Table 2. These changes in particle size were attributed to the addition of Na2HPO4. However, it did not followed any specific trend.

The turbidity values of 4 and 7% Na2HPO4 containing non-homogenized and 5% Na2HPO4 containing homogenized 2.40 × UFR samples were significantly different (P < 0.05) with each other. However, turbidity values of all remaining samples were statistically at par (P < 0.05) with each other as shown in Table 2. The aggregation and dissociation of casein micelles can be indirectly examined through turbidity measurements (Kaliappan and Lucey 2011) as the turbidity ultrafiltered retentates decreases due to dissociation of the casein micelles into smaller structures.

Rheological properties of different samples

The samples were characterized for their rheological behaviour and the shear rate-shear stress (Fig. 2) relationship data were fitted to selected rheological models as shown the Table 3. UFR containing 0.5% DSP exhibited the Newtonian flow. However, the addition of 1% DSP imparted the yield stress at very low shear rate that disappeared upon shearing and positive linear stress–strain relationship above shear rate of 26 s−1 (data not shown). This particular flow behaviour was not characteristics of common flow behaviour observed among the viscous samples. Further, increase in DSP concentration imparted Newtonian behaviour, except 4% DSP wherein yield stress of 0.5 Pa was observed before linear plastic flow as characterized by Bingham flow. Higher concentration of DSP (6–7%) shifted the flow behaviour from Newtonian to Power law or non-Newtonian behaviour, particularly pseudoplastic as indicated by the flow behaviour index values less than 1. The apparent viscosity of samples exhibiting such behaviour also increased with increase in the DSP concentration from 3 to 7%. The gelation of protein in presence of DSP was also indicated by appearance of yield stress in the flow curve. Meena et al. (2016) reported the effects of various treatments on flow behaviour of cow milk based 5 × UF retentate. DSP addition imparted the flow characteristics that follow Herschel Bulkley as well as Carreau–Yasuda behaviour with infinite zero shear viscosity explaining its consistency. Further, these researchers reported the importance of pH adjustment on rheological behaviour of UFR by addition of DSP. The rheological properties and heat gelation temperature are of great importance as they govern the stability of feed material during the spray drying. The feed with very high yield stress and lower heat gelation temperature is expected to block the spray dryer nozzle as for optimal atomization the viscosity values of whole milk and skim milk concentrate (TS: 48–50%) must not be more than 60 and 100 Cp, respectively at 40 °C (Early 1998). The 2.40 × HUFR + 5%DSP sample exhibited Power law flow behaviour whereas 2.40 × HUFR + 2.5%DSP exhibited Newtonian flow. Very high apparent viscosity in 2.40 × HUFR + 5%DSP compared to 2.40 × HUFR + 2.5%DSP and 2.40 × UFR + 5%DSP samples suggested possible role of homogenization in the alteration in protein and mineral structure along with DSP addition. This was also evident from the apparent viscosity values of 2.40 × UFR + 2%DSP, 2.40 × UFR + 3%DSP and 2.40 × HUFR + 2.5%DSP, which was extremely high for 2.40 × UFR + 2%DSP, but drastic reduction was observed upon increase in DSP concentration and homogenization.

Table 3.

Rheological parameters modelling of non-homogenized and homogenized 2.40 × UFR samples obtained after the addition of different levels of Na2HPO4 (DSP)

| UFR samples | Rheological models | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newtonian | Bingham | Power law | Herschel–Bulkley | ||||||||

| η (mPa s) | R2 | σ (Pa) | ηb (mPa s) | R2 | k (Pa sn) | n | R2 | σ (Pa) | n | R2 | |

| 2.40 × UFR + 0%DSP (control) | 5.4 | 0.875 | 0.071 | 4.4 | 0.952 | 0.026 | 0.6229 | 0.839 | 0.071 | 0.405 | 0.243 |

| 2.40 × UFR + 0.5%DSP | 25.3 | 0.992 | – | – | – | 0.027 | 0.974 | 0.768 | 0.027 | 0.974 | 0.768 |

| 2.40 × UFR + 1%DSP | – | – | 2.095 | 4.8 | 0.405 | 0.42 | 0.122 | 0.131 | – | – | – |

| 2.40 × UFR + 2%DSP | 14.5 | 0.898 | – | – | – | 0.37 | 0.311 | 0.534 | 1.93 | 0.091 | 0.3397 |

| 2.40 × UFR + 3%DSP | 5.1 | 0.964 | – | – | – | 0.202 | 0.085 | 0.008 | 0.203 | 0.057 | 0.0025 |

| 2.40 × UFR + 4%DSP | 24.4 | 0.721 | 0.503 | 16.8 | 0.986 | 0.313 | 0.383 | 0.801 | 0.503 | 0.392 | 0.802 |

| 2.40 × UFR + 5%DSP | 12.6 | 0.984 | – | – | – | 0.124 | 0.42 | 0.245 | 0.085 | 0.498 | 0.232 |

| 2.40 × UFR + 6%DSP | – | – | 10.76 | 77.8 | 0.842 | 6.464 | 0.22 | 0.867 | 6.437 | 0.221 | 0.866 |

| 2.40 × UFR + 7%DSP | – | – | 5.29 | 150.1 | 0.968 | 1.985 | 0.491 | 0.992 | 0.17 | 0.938 | 0.768 |

| 2.40 × HUFR + 2.5%DSP | 8.2 | 0.985 | – | – | – | 0.017 | 0.826 | 0.574 | – | – | – |

| 2.40 × HUFR + 5%DSP | – | – | 9.72 | 77.6 | 0.902 | 6.077 | 0.217 | 0.933 | – | – | – |

Where η-viscosity, σ-yield stress, ηb-plastic viscosity, k-consistency coefficient, n-flow behavior index, R2-coefficient of determination

The bold text shows the best fit model for a particular sample

The G′ and G″ crossover temperature (65.46 °C) of 2.40 × UFR + 3%DSP sample was significantly higher (P < 0.05) compared to other remaining DSP containing non-homogenized and homogenized UFR samples (Table 2). Moreover, crossover temperature of 2.40 × UFR + 3%DSP and 2.40 × HUFR + 2.5%DSP UFR samples were statistically at par (P > 0.05) with each other. However, remaining all other UFR samples exhibited no-significant (P > 0.05) difference with each other.

Correlation in ζ-potential, viscosity, particle size, turbidity and pH of homogenized and non-homogenized 2.40 × UFR samples

In 2.40 × UFR (control) sample, ζ-potential (r = + 1.00, P < 0.01) showed highly positively correlation with its particle size (data given in supplementary file). In 2.40 × UFR + 0.5%DSP sample, particle size exhibited highly positively (r = + 0.999, P < 0.01) and highly negatively (r = − 0.997, P < 0.01) correlation with its crossover temperature of G′ and G″ and viscosity, respectively. It was observed that particle size and turbidity were negatively (r = − 0.999, P < 0.05) correlated with each other in 2.40 × UFR + 1% DSP sample, while ζ-potential and turbidity of 2.40 × UFR + 3% DSP sample were positively (r = + 0.997, P < 0.05) correlated with each other. Moreover, ζ-potential and crossover temperature of G′ and G″(r = + 0.999, P < 0.05); particle size and turbidity (r = + 0.999, P < 0.05) were positively while particle size (r = − 0.999, P < 0.05) and turbidity (r = − 0.999, P < 0.05) showed negative correlation with pH in 2.40 × UFR + 4% DSP sample. Further, particle size and viscosity were negatively correlated (r = − 0.999, P < 0.05) with each other in 2.40 × HUFR + 2.5% DSP sample. However, in remaining UFR samples correlation among their physical properties were absent.

Conclusion

The changes in ζ-potential, particle size, heat stability, turbidity, pH, viscosity as well as G′ and G″ of the ultrafiltered retentate as a function of disodium phosphate addition and homogenization have been investigated. Ultrafiltered retentate possesses higher amount of milk constituents except lactose than pasteurized buffalo skim milk owing to its concentration in UF process. Disodium phosphate addition markedly improved (i.e. increased values in negative side) ζ-potential values of homogenized and non- homogenized retentates due to their increased pH. This increased pH might have shifted the protein-mineral equilibrium, enhanced the repulsions within the casein micelles, decreased calcium ion activity and attributed to better stability of milk proteins in retentate samples. Apart this, interaction of disodium phosphate with casein micelles also increased viscosity and pH of non-homogenized retentates; induced variable changes in their particle size and turbidity as these properties are interrelated. Contrary to this, double stage homogenization checked the rise in viscosity of homogenized retentate at even higher (2.5 and 5%) levels of disodium phosphate. The rheological behaviour of homogenized retentate (2.40 ×) containing 2.5 and 5% disodium phosphate and control retentate was best explained by Newtonian, Power law and Bingham models, respectively. The G′ and G″ crossover temperature (65.46 °C) of 3% disodium phosphate containing retentate was significantly higher (P < 0.05) as this levels might be most suitable to enhance thermal stability of 2.40 × retentate. The impact of applied interventions on retentates properties was also advocated by their correlation coefficients. Thus, this study has established that addition of disodium phosphate at suitable levels enables the processing of homogenized and non-homogenized UF retentates at elevated temperatures. It may also express better functionality in dried products such as milk protein concentrates and dairy whiteners which are produced from UF retentates.

Acknowledgements

The first author is very grateful to the Director, ICAR-National Dairy Research Institute, Karnal for providing the required facilities to carrying out this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Broyard C, Gaucheron F. Modifications of structures and functions of caseins: a scientific and technological challenge. Dairy Sci Technol. 2015;95(6):831–862. doi: 10.1007/s13594-015-0220-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Kort E, Minor M, Snoeren T, van Hooijdonk T, van der Linden E. Effect of calcium chelators on heat coagulation and heat-induced changes of concentrated micellar casein solutions: the role of calcium-ion activity and micellar integrity. Int Dairy J. 2012;26(2):112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2012.03.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deeth H, Lewis M. Protein stability in sterilised milk and milk products. In: McSweeney PLH, O’Mahony JA, editors. Advanced dairy chemistry. New York: Springer; 2016. pp. 247–286. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan DB. Multiple range and multiple F tests. Biometrics. 1955;11(1):1–42. doi: 10.2307/3001478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Early R. Technology of dairy products. London: Blackie Academic and Professional; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Holt C, Dalgleish DG, Jenness R. Inorganics constituents of milk. 2. Calculation of the ion equilibrium in milk diffusate and comparison with experiment. Anal Biochem. 1981;113:154–163. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IDF . Lait: determination de la teneur en azote; IDF standard 20 B. Brussels: International Dairy Federation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Indian Standard . Methods of test for dairy industry-Part II: chemical analysis of milk. Bureau of Indian Standards, IS-1479, Manak Bhavan. New Delhi: BIS; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Indian Standard . Determination of fat by the Gerber method-Part I: milk. Bureau of Indian Standards, IS-1224, Manak Bhavan. New Delhi: BIS; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Indian Standard . Milk, cream and evaporated milk-determination of total solid content (reference method). Bureau of Indian Standards, IS-12333, Manak Bhavan. New Delhi: BIS; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kaliappan S, Lucey JA. Influence of mixtures of calcium-chelating salts on the physicochemical properties of casein micelles. J Dairy Sci. 2011;94(9):4255–4263. doi: 10.3168/jds.2010-3343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatkar SK, Gupta VK, Khatkar AB. Studies on preparation of medium fat liquid dairy whitener from buffalo milk employing ultrafiltration process. J Food Sci Technol. 2014;51(9):1956–1964. doi: 10.1007/s13197-014-1259-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S (2011) Studies on the preparation of Dairy Whitener employing ultrafiltration. Ph.D. thesis, National Dairy Research Institute, Karnal, India

- Meena GS, Singh AK, Borad S, Raju PN. Effect of concentration, homogenization and stabilizing salts on heat stability and rheological properties of cow skim milk ultrafiltered retentate. J Food Sci Technol. 2016;53(11):3960–3968. doi: 10.1007/s13197-016-2388-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meena GS, Singh AK, Arora S, Borad S, Sharma R, Gupta VK. Physico-chemical, functional and rheological properties of milk protein concentrate 60 as affected by disodium phosphate addition, diafiltration and homogenization. J Food Sci Technol. 2017;54(6):1678–1688. doi: 10.1007/s13197-017-2600-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meena GS, Singh AK, Panjagari NR, Arora S. Milk protein concentrates: opportunities and challenges—a review. J Food Sci Technol. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s13197-017-2796-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meena GS, Singh AK, Gupta VK, Borad S, Parmar PT. Effect of change in pH of skim milk and ultrafiltered/diafiltered retentates on milk protein concentrate (MPC70) powder properties. J Food Sci Technol. 2018;55(9):3526–3537. doi: 10.1007/s13197-018-3278-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell JE, Fox PF. Heat stability of milk. In: Fuquay JW, Fox PF, McSweeney PLH, editors. Encyclopedia of dairy science. 2. San Diego: Academic Press; 2011. pp. 744–749. [Google Scholar]

- Orlien VL, Boserup L, Olsen K. Casein micelle dissociation in skim milk during high-pressure treatment: effects of pressure, pH, and temperature. J Dairy Sci. 2010;93(1):12–18. doi: 10.3168/jds.2009-2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AA, Patel RS, Singh RRB, Rao KK, Singh Sudhir, Gupta SK, Sindhu JS, Dodeja AK, Kessler HG, Hinrichs J (1999) Studies on heat stability of membrane concentrated milk meant for ultra-high temperature (UHT) sterilization. Final report: Volkswagen Foundation Funded Research Project. In collaboration between National Dairy Research Institute, Karnal and Institute of Dairy and Food Process Engineering Technical University of Munich, Fresing, Germany

- Patil AT, Meena GS, Upadhyay N, Khetra Y, Borad S, Singh AK. Production and characterization of milk protein concentrates 60 (MPC60) from buffalo milk. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2018;91:368–374. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2018.01.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Randhahn H. The flow properties of skim milk concentrates obtained by ultrafiltration. J Texture Stud. 1976;7(2):205–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4603.1976.tb01262.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh H (1995) Heat-induced changes in caseins including interactions with whey proteins. In: Fox PF (ed) Heat-induced changes in milk. Special issue 9501, International Dairy Federation, Brussels, pp 86–99

- Singh H. Heat stability of milk. Int J Dairy Technol. 2004;57:111–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0307.2004.00143.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K. Commercial membrane technology. In: Tamime AY, editor. Membrane processing: dairy and beverage applications. 1. Hoboken: Wiley; 2013. pp. 52–71. [Google Scholar]

- Snoeren THM, Damman AJ, Klok HJ. The viscosity of skim milk concentrate. Neth Milk Dairy J. 1982;36:305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Solanki P, Gupta VK. Effects of stabilizing salts on heat stability of buffalo skim milk ultrafiltered-diafiltered retentate. J Food Sci Technol. 2009;46(5):466–469. [Google Scholar]

- Solanki P, Gupta VK. Manufacture of low lactose concentrated ultrafiltered-diafiltered retentate from buffalo milk and skim milk. J Food Sci Technol. 2014;51(2):396–400. doi: 10.1007/s13197-013-1142-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Gelais D, Hache S, Gros-louis M. Combined effects of temperature, acidification, and diafiltration on composition of skim milk retentate and permeate. J Dairy Sci. 1991;75:1167–1172. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(92)77863-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sweetsur AWM, Muir DD. Effect of concentration by ultrafiltration on the heat stability of skim milk. J Dairy Res. 1980;47:327–335. doi: 10.1017/S002202990002121X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tayal M, Sindhu JS. Heat stability and salt balance of buffalo milk as affected by concentrate and addition of casein. J Food Process Preserv. 1983;7:151–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4549.1983.tb00673.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tunick MH. Rheology of dairy foods that gel, stretch, and fracture. J Dairy Sci. 2000;83:1892–1898. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(00)75062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]