Abstract

Three efficient Bacillus species selected among the 55 indigenous isolates from poultry manure (PM) were used for the development of a rapid and efficient composting process. The biochemical and 16sr RNA sequence analyses identified the isolates as Bacillus flexus (B-07), B. cereus (B-41) and B. subtilis (B-54). Collectively, the consortium has the ability of cellulolysis, keratinolysis, ammonia oxidation, nitrite oxidation and P solubilization for composting PM along with carbon amendments. The efficacy of composting with rice husk or sawdust with the consortium (109 CFU/ml) was tested. The biochemical and microbiological profiles showed that the efficacy of compost with sawdust along with consortium was better when compared to rice husk, resulting in the development of a rapid and single cycle of composting in 30 days. The resultant compost in pot trials enhanced the yield of the pulse crop, Vigna radiata to 78% and the oilseed crop, Sesamum indicum to 45% when compared to the addition of chemical fertilizers.

Keywords: Rapid composting, Poultry manure, Bacillus spp., Nitrogen conservation, Carbon amendment

Highlights

A versatile consortium of native Bacillus spp. from poultry manure was designed.

Efficacy of composting poultry manure was tested with rice husk or sawdust.

Sawdust performed better resulting in a single step rapid composting process.

Sawdust compost enhanced growth and yield of Vigna radiata and Sesamum indicum.

Introduction

Bioremediation of poultry manure (PM) to tackle the odour-associated problem, and water and air pollution is a global concern due to the expansion of poultry industries and the accumulation of PM. Livestock manure was known to emit over 160 odorous compounds (O’neill and Phillips 1992) and nitrogen loss due to ammonia volatilization is the major problem in PM in addition to other problems such as NO2 emission, NO3 leaching, and P run-off (Moore 1998; Yaowu et al. 2001; Burgos and Burgos 2006; González et al. 2009). As poultry manure contains greater concentration of nutrients such as nitrogen (~ 2%), phosphorus (~ 1.5%) and calcium (~ 3.5%) than other animal manures, it provides more incentive for its utilization as a source of plant nutrients (Wilkinson 1979; Fontenot et al. 1983). Further, maize fertilized with composted poultry manure was more resistant to grey leaf spot disease (Lyimo et al. 2012). Many factors are known to influence the composition of PM, viz., age of birds, climatic conditions, nature of feed used (Iyappan et al. 2011) and seasons (Karthikeyan et al. 2011). PM is a microcosm rich in microbial diversity (108 CFU/g dry weight) where bacteria particularly aerobic bacteria are predominant (Nodar et al. 1990). Various reports indicate the abundance of actinomycetes, fungi and specific groups such as acidophiles or acidotolerant, cyanobacteria, cellulolytic, amylolytic, pectinolytic, proteolytic, ammonificant, anaerobic as well as aerobic free-living nitrogen fixers, denitrifiers, ammonium oxidizers, nitrate oxidizers, sulphate reducers, sulphur oxidizers, and organic sulphur mineralizers (Nodar et al. 1990). The collective action of these microorganisms results in the mineralization of various elements in PM that formed the basis for the problem of pollution. Seasonal changes influence the population of ammonia and nitrite oxidizers as well as urease and uricase producers which have an impact on the nutrient status of PM (Karthikeyan et al. 2011). Indigenous microorganisms usually denote specific mixed cultures of known, beneficial microorganisms that are being used effectively as microbial inoculants. They could exist naturally in soil or added as microbial inoculants to soil where they can improve soil quality, enhance crop production and create a more sustainable agriculture and environment (Kumar and Sai Gopal 2015). It is reported that balancing the native microorganisms to dominate desired microbe may end up with conservation of nutrients. There are numerous patents on the utilization of PM into fertilizer, feed, energy/fuel and other non-conventional applications (Sekar et al. 2010). Patents also encompass methods for reducing odour/ammonia volatilization from PM and development of microbial consortia for rapid degradation. However, exploitation of native microorganisms particularly, heterotrophic nitrifying bacteria and other beneficial microbes to redirect and hasten the process of composting to the desired level was lacking. The nitrogen in the poultry manure can be conserved by either inhibiting the hydrolysis of uric acid to NH3 or by reducing the volatilization of NH3 (Carlile 1984). This can be achieved by chemical means but they render the manure unsuitable for composting. Employing composting to convert the problematic PM into value-added fertilizer for crop application is a viable, renewable and environment-friendly approach. It will be novel and apt to exploit the beneficial native microflora of PM as well as perform better composting with the inoculation of a consortium of beneficial microbes. This approach warrants a systematic screening of native microflora of PM, designing of a competent consortium of microbes to conserve nitrogen and phosphorus as well as perform decomposition of organic components by composting followed by crop testing and hence this work.

Materials and methods

Screening and consortium development

Poultry manure samples were collected from three different high-rise layer farms located at Namakkal region (11.23°N 78.17°E) of Tamil Nadu, India, for the isolation and screening of bacteria and stored at 4 °C in lab within 3 h of sampling. Morphologically distinct bacterial colonies were obtained by standard microbiological procedures (Abdelhamid et al. 2004). The bacterial isolates were screened for the absence of the biochemical properties such as ammonifying activity (Kidd et al. 2008), urease- (Atlas and Parks 2004) and uricase-producing activity (Schefferle 1965) and presence of heterotrophic ammonia and nitrite oxidation (Matsuzaka et al. 2003), P solubilization (Mehta and Nautiyal 2001), cellulolytic (Kasana et al. 2008) and keratinolytic activity (Kim et al. 2001). The selected organisms were further tested for the absence of nitrate reduction (Abdelhamid et al. 2004) and faecal coliform activities (Hartel and Hagedorn 1983). The isolates were cross streaked on nutrient agar plates to check compatibility among them for coexistence as a consortium.

Identification of selected isolates

The selected bacterial isolates utilized in the consortium were identified using Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology (Abdelhamid et al. 2004; Schleifer 2009) and further 16 s rRNA analysis was also performed (Hiorns et al. 1995).

Composting experiment

Source materials and setup of composting

The collected poultry manure samples and the carbon-rich amendments such as rice husk and saw dusts procured from local market were utilized for the experiments. The composting experiments were carried out in wooden compost bins (60 cm × 60 cm × 60 cm) as modified from Sivakumar et al. (2008). Walls of the compost bins were made up of wooden blocks having aeration gaps of 2.5 cm width. Movable door was provided at one side of the compost bin. Temperature prevailed at the compost yard and the compost bins were monitored using compost thermometer. To maintain the level of inoculum in the consortium used for composting, log phase cultures with a culture density of 109 CFU/ml were maintained. To achieve this, growth curve and generation time of the organisms were ascertained (Abdelhamid et al. 2004).

Compost mixture preparation

The source materials such as poultry manure, sawdust and rice husk were analysed for their moisture (Peters et al. 2003), organic carbon (Walkley and Black 1934) and total nitrogen (Bremner and Mulvaney 1982; Foss Tecator 2003). Total carbon was calculated by multiplying organic carbon (%) by a factor of 1.3 (Muthuvel and Udayasoorian 1999). The percentage values were converted into numerals for the preparation of compost mixtures (Rynk et al. 1994).

Biochemical characterization of compost mixture

Various biochemical features such as pH, moisture and dry matter (Peters et al. 2003), organic carbon (Walkley and Black 1934), total nitrogen (Bremner and Mulvaney 1982; Foss Tecator 2003), C:N ratio, total Kjeldahl nitrogen (Bremner and Mulvaney 1982), available nitrogen (Subbiah 1956), ammonia nitrogen (American Public Health Association 1998), nitrate nitrogen (Cataldo et al. 1975), nitrite nitrogen (Mulvaney 1994), urea nitrogen (Mulvaney and Bremner 1979) and uric acid nitrogen (Alumot and Bielorai 1979) were analysed in the compost mix during the composting process. The total nitrogen and total Kjeldahl nitrogen were analysed by macro-Kjeldahl method. Samples were digested using auto 2000 block digestion system, distilled in 2100 Kjeltec™ distillation unit (FOSS Tecator, Sweden) and analysed for nitrogen as in Foss Tecator Application Note, AN300 (Bremner and Mulvaney 1982; Foss Tecator 2003).

Microbiological characterization of compost mixture

Total heterotrophic bacterial counts (Zuberer 1994), ammonifiers (Kidd et al. 2008), urease producers (Atlas and Parks 2004), uricase producers (Schefferle 1965) and heterotrophic nitrifiers (Matsuzaka et al. 2003) were analysed during the composting process.

Compost maturity analysis

Maturity of the compost was assessed by the temperature profile of the compost, reduction of moisture and reduction in the volume of the compost during the composting process. Moreover, C:N ratio, nitrate:nitrite ratio and ammonia:nitrate ratio were also calculated during the composting process (Fong et al. 1999).

Crop testing

A cereal crop—rice (Oryza sativa) variety ‘TRY 3’, a pulse crop—green gram (Vigna radiata) variety ‘KM 2’ and an oil seed crop—sesame (Sesamum indicum) variety ‘TMV 6’ were chosen to study the efficacy of the composted manure against recommended chemical fertilizer for each crop. Crop testing was performed in earthen pots of 5 l capacity containing a mix of 5 kg of red soil and 2.5 kg of sand. The quantum of compost for the composting experiment was at the rates of 15 g/pot (PT2) and 30 g/pot (PT3) against recommended chemical fertilizer (PT1) for each crop (http://agritech.tnau.ac.in). The control (without any fertilizer/compost) was also maintained. The pot experiment was carried out in triplicates. Various morphometric parameters such as germination percentage, number of leaves/plant, shoot length, number of seeds per plant and yield per plant were calculated during the experiment (Mishra et al. 2009).

Statistical analysis

The experiments were conducted with three replicates and the standard deviations (±) were computed using Microsoft Excel 2010 (Windows 8 Edition, Microsoft Corporation, USA). One-way analysis of variance and comparison of means based on the Duncan’s multiple range test (P < 0.05) were used to determine the significant differences between the treatments. Paired T test was used to analyse significant differences between initial and final results of a particular treatment. All statistical tests were evaluated at the 95% confidence level. Statistical analyses were carried out with SPSS statistical package version 21 from SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA (Griffith 2010).

Results and discussion

Screening and consortium development

From the random PM samples collected from poultry industries, 55 isolates of heterotrophic bacteria with distinct colony morphology were selected. They were screened for various properties such as cellulolysis, keratinolysis, ammonia oxidation, NO2 oxidation, P solubilization, ammonification, and uricase and urease production. Of the 55 isolates, three bacteria (B-07, B-41 and B-54) possessing a variety of desirable metabolic properties were selected for the formation of a consortium (Table 1). This consortium had the ability of utilizing cellulose of the carbon amendments (rice husk and/or sawdust) and digestion of withered feather from the reared birds. In addition, ability to oxidize ammonia and nitrite (heterotrophic nitrification) to conserve its nitrogen and to perform P solubilization was also present. However, strains B-07 and B-54 showed uricase activity which may be apparently undesirable but essential for the conversion of uric acid into ammonia. This problem could be compensated by augmenting the conversion of ammonia into NO3 by ammonia and nitrite oxidation potentials which is present in the consortium. Moreover, the designated consortium microbes compensate and alternate each other in terms of possessing desired properties as well as lacking properties that should not be enhanced such as ammonification and urease activity (Table 1). Three bacteria in the consortium were devoid of the activity of nitrate reduction and faecal coliform. These isolates were checked for the suitability of consortia formation by cross-streaking experiment and there was no antagonism indicating their compatibility for the formation of consortium. Hence, including the three organisms in the consortium is essential to obtain the collective properties for enhanced composting of PM along with carbon amendment.

Table 1.

Properties of the selected bacteria chosen for consortium development

| Strain no. | Desired properties | Properties not to be enhanced | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulolytic activity | Keratinolytic activity | Ammonia oxidization | Nitrite oxidization | P solubilization | Ammonification | Uricase production | Urease production | |

| B-7 | +a | − | + | − | + | − | + | − |

| B-41 | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| B-54 | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − |

a + Denotes presence of and − denotes absence of the particular property

Identification of bacteria in consortium

The consortium members were identified using colony characters, microscopic examinations and biochemical tests. Further, 16 s rRNA analysis identified the microorganisms as Bacillus flexus (B-07), B. cereus (B-41) and B. subtilis (B-54) and the GenBank accession numbers are KJ854384, KJ854385 and KJ854386, respectively. Notably, all the microbes in the consortium are endospore formers which could be advantageous for using them as microbial inoculants in the composting process.

Composting

The process of composting destroys pathogens, converts N from unstable ammonia to stable organic forms, reduces the volume of waste and improves the nature of the waste. It also makes waste easier to handle and transport and often allows for higher application rates because of the increased stability and slow release of N from compost (Fauziah and Agamuthu 2009). The effectiveness of the composting process is influenced by factors such as temperature, oxygen supply (i.e. aeration) and moisture content (Tweib et al. 2011). For proper handling of bacterial inoculants, growth pattern and growth potential (generation time) of the three organisms are necessary to proceed with composting. Growth curve and the time required to obtain 109 CFU/ml were assessed for all the three bacteria. It is to provide higher level (109 CFU/ml) of inoculum to catalyse composting. The generation time (min) and the time (h) required to attain the culture density of 109 CFU/ml for B. flexus (58.4 min & 20 h), B. cereus (63.7 min & 22 h) and B. subtilis (64.7 min and 21 h) were obtained. For proper composting, maintenance of desired C:N level (25:1) and moisture content (60%) is crucial (De Bertoldi et al. 1983). The major problem of PM is its low C:N level (6–9:1), moisture and microbial activity. If the initial C:N ratio is greater than 35, the microorganisms have to go through many life cycles, oxidizing the excess carbon until a more convenient C:N ratio for their metabolism is reached. In spite of that, this low value would lead to a nitrogen loss through ammonia volatilization especially at high pH and temperature values. After extensive experiments on composting of municipal solid waste (mixed and unmixed with sludge) it was determined that the general optimum C:N ratio was 25 in the starting material (De Bertoldi et al. 1983). To enhance C:N level, amendment with carbon substrate is practiced. PM being a pelleted material, particulate and cheap carbon sources such as sawdust and rice husk will be suitable for mixing and composting. To start with, compost ingredients were biochemically analysed (Table 2) to know the level of moisture, carbon and nitrogen. Subsequently, the percentage values were converted into per kg values (Rynk et al. 1994) that were useful to plan the various treatments for composting (Table 3). In all the treatments, the C/N ratio of 25:1 and moisture content of 60% were maintained (Table 3).

Table 2.

Composition of materials used for composting

| Parameters | Poultry manure | Sawdust | Rice husk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture (%) | 23.13 ± 3.11 | 8.0 ± 1.22 | 5.58 ± 0.83 |

| Dry matter (%) | 76.87 ± 3.11 | 92.0 ± 1.22 | 94.42 ± 0.83 |

| Organic carbon [OC] (%) | 15.3 ± 2.53 | 22.82 ± 2.46 | 17.47 ± 1.38 |

| Total nitrogen (%) | 0.373 ± 0.15 | 0.015 ± 0.004 | 0.044 ± 0.01 |

| Total carbon (OC × 1.3) (%) | 19.83 ± 3.29 | 29.66 ± 3.20 | 22.7 ± 1.80 |

| C:N ratio | 53.16 | 1977.33 | 515.90 |

The numerical values are given as mean ± standard deviation

Table 3.

Quantity of compost ingredients used to attain the desired C:N ratio (25:1), moisture content (60%) and the level of inoculum (109 CFU/ml) for the formulation of compost treatments

| Treatments | Poultry manure (kg) | Saw dust (kg) | Rice husk (kg) | Water (l) | Bacterial consortium (l) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 100.00 | – | – | – | – |

| T1 | 79.29 | 20.71 | – | 100.00 | – |

| T2 | 75.07 | – | 24.93 | 103.00 | – |

| T3 | 79.29 | 20.71 | – | 95.00 | 5.00 |

| T4 | 75.07 | – | 24.93 | 97.85 | 5.15 |

Control PM (poultry manure) alone, T1 PM + saw dust, T2 PM + rice husk, T3 PM + saw dust + consortium, T4 PM + rice husk + consortium

Monitoring composting

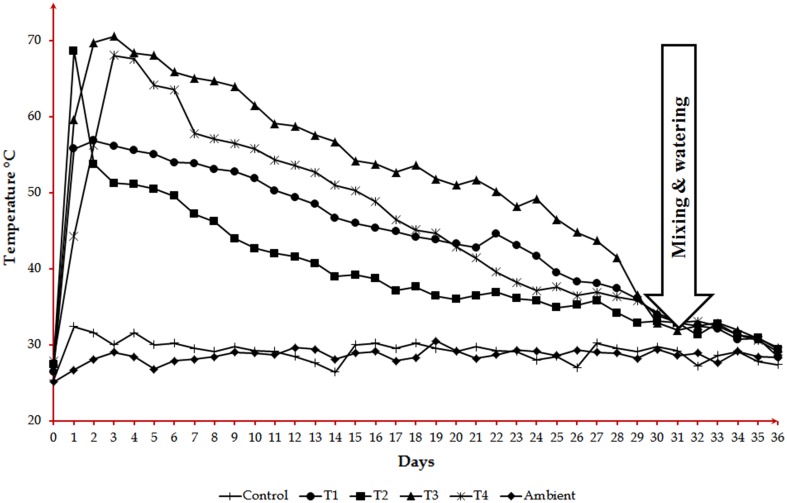

For all the five treatments, temperature at the core of the compost bins was recorded every day (Fig. 1) which is compared with the ambient temperature. Usually, composting is associated with a rise in temperature. Once the temperature reaches ambience, the composting treatments were aerated by mixing as well as watered to maintain the moisture content. If the composting was incomplete in the first phase, the temperature will again shoot up (Rynk et al. 1994). This procedure of mixing and watering has to be repeated whenever the compost reaches the ambient temperature and until no further rise in temperature was observed.

Fig. 1.

Ascertaining compost maturity by tracking temperature during composting

For rapid composting, high temperatures for long periods must be avoided. An initial thermophilic phase may be useful in controlling thermo-sensitive pathogens (Golueke 1982). After this stage, it is preferable to reduce temperatures to levels which allow the development of eumycetes and actinomycetes which are the main decomposers of the long-chain polymers, cellulose and lignin (Chang 1967; Chang and Hudson 1967; Dunlap and Chiang 1980; De Bertoldi et al. 1982). All the composting treatments performed here started with thermophilic temperatures in the range of 56 and 71 °C (Fig. 1), an indication that the C:N ratios were ideal (Ogunwande et al. 2008) and the pathogens and weed seeds would have been destroyed (Haga 1999; Misra et al. 2003). The thermophilic phase (> 50 °C, for 7–22 days) observed is also associated with the turned windrow method (Diaz et al. 2002).

In control, poultry manure alone was subjected to composting (Fig. 1). There was a slight increase in temperature in the early period of composting up to 10 days and subsequently, only ambient was maintained. In the case of T1 (poultry manure and sawdust), temperature increased from ambient to 60 °C which gradually decreased up to 30 days to reach ambience. In T2 (poultry manure and rice husk), the pattern was almost similar to T1 except increase in temperature which was up to 70 °C. Upon adding bacterial consortium to poultry manure and sawdust combination (T3) and poultry manure and rice husk combination (T4), the temperature could increase up to 70 °C showing very gradual decrease up to 30 days to reach ambient. Comparatively, temperature profile upon adding inoculum showed steep increase in temperature and very gradual decrease to reach ambient indicating that microbial action is involved by the introduction of consortium. The addition of ammonia oxidizing archaea to poultry waste compost was able to speed up both the onset of the hyperthermic phase and the composting time (Xie et al. 2012).

Subsequently, in all the treatments, mixing and watering to reach 60% moisture level was performed and refilled into the compost bins. Monitoring of core temperature of the compost bins was followed up to 37 days (Fig. 1) which showed no change indicating that the composting process was complete. So, a single cycle of composting for a period of 30 days is evident.

Biochemical and microbiological analyses of compost

Upon completion of composting, various biochemical features were estimated and compared with the initial level and among the treatments (Tables 4, 5 and 6).

Table 4.

Physico-chemical changes upon composting with various treatments

| Property | Time | Control | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | Initial | 7.13 ± 0.11a | 7.24 ± 0.10a | 7.15 ± 0.10a | 7.28 ± 0.03a | 7.19 ± 0.03a |

| 31 days | 7.10 ± 0.05b | 7.50 ± 0.08c | 6.95 ± 0.08ab | 7.62 ± 0.07c | 6.91 ± 0.06a | |

| Moisture (%) | Initial | 36.00 ± 1.04b | 60.50 ± 0.90c | 60.44 ± 2.32a | 60.90 ± 1.05c | 60.40 ± 1.05c |

| 31 days | 27.00 ± 0.83a | 35.00 ± 0.86b | 43.00 ± 0.86c | 34.10 ± 0.7b | 45.80 ± 1.58d | |

| Dry matter (%) | Initial | 64.00 ± 0.85c | 39.50 ± 0.74a | 39.56 ± 1.89b | 39.10 ± 0.86a | 39.60 ± 0.86a |

| 31 days | 73.00 ± 0.83d | 65.00 ± 1.17c | 57.00 ± 0.86b | 65.90 ± 0.70c | 54.20 ± 1.58a | |

| Organic Carbon (%) | Initial | 24.15 ± 1.16a | 32.07 ± 1.17b | 35.91 ± 1.13d | 30.95 ± 0.91b | 36.27 ± 0.34c |

| 31 days | 22.96 ± 0.13b | 23.22 ± 0.03c | 24.78 ± 0.03e | 20.89 ± 0.03a | 24.46 ± 0.10d | |

| Total Carbon (%) | Initial | 31.40 ± 0.20b | 41.70 ± 0.23c | 46.68 ± 0.19a | 40.23 ± 1.18c | 44.96 ± 1.61d |

| 31 days | 29.85 ± 0.17b | 30.19 ± 0.03c | 32.21 ± 0.04e | 27.16 ± 0.04a | 31.80 ± 0.13d | |

| Total nitrogen (%) | Initial | 2.60. ± 0.10c | 1.64 ± 0.05ab | 1.90 ± 0.1d | 1.59 ± 0.02a | 1.80 ± 0.04b |

| 31 days | 2.54 ± 0.02e | 2.21 ± 0.02b | 2.02 ± 0.02a | 2.36 ± 0.05d | 2.29 ± 0.02c | |

| C/N ratio | Initial | 12.09 ± 0.78a | 25.43 ± 1.13b | 24.47 ± 1.16c | 25.30 ± 0.74b | 24.98 ± 0.75b |

| 31 days | 11.77 ± 0.13a | 13.66 ± 0.09b | 15.98 ± 0.18c | 11.75 ± 0.23a | 13.89 ± 0.11b |

The numerical values are given as mean ± standard deviation. Values with the same superscript in a row are not significantly different as per Duncan’s multiple range test at probability level P < 0.05

Control PM alone, T1 PM + saw dust, T2 PM + rice husk, T3 PM + saw dust + consortium, T4 PM + rice husk + consortium

Table 5.

Changes in the level of nitrogenous compounds upon composting with various treatments

| Property | Time | Control | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Available nitrogen (ppm) | Initial | 8260 ± 143a | 4130 ± 164a | 4610 ± 287b | 4320 ± 70a | 5010 ± 80a |

| 31 days | 5160 ± 125b | 7230 ± 267c | 3920 ± 70a | 8490 ± 83d | 4130 ± 164a | |

| Nitrate N (ppm) | Initial | 130 ± 4d | 60 ± 3b | 90 ± 2e | 50 ± 1a | 80 ± 6c |

| 31 days | 80 ± 2a | 74 ± 1.8a | 118 ± 6.5b | 131 ± 0.9c | 90 ± 3b | |

| Nitrite N (ppm) | Initial | 9 ± 0.1a | 6 ± 0.1a | 4 ± 0.2b | 7 ± 0.2a | 8 ± 0.1a |

| 31 days | 6 ± 0.1a | 6 ± 0.01a | 5 ± 0.1a | 9 ± 0.2b | 9 ± 0.2b | |

| Ammonia N (ppm) | Initial | 1700 ± 72c | 1430 ± 46a | 1210 ± 20a | 1520 ± 13b | 1610 ± 70b |

| 31 days | 1920 ± 9d | 1208 ± 10a | 1360 ± 22b | 1130 ± 14a | 1770 ± 60c | |

| Urea N (ppm) | Initial | 40 ± 2d | 10 ± 1b | 30 ± 2a | 20 ± 0.8c | 50 ± 2e |

| 31 days | 30 ± 2b | 20 ± 1.6a | 50 ± 2c | 30 ± 0.8b | 60 ± 1.6d | |

| Uric acid N (ppm) | Initial | 3860 ± 153d | 2710 ± 88b | 2720 ± 86a | 2630 ± 85b | 2910 ± 18c |

| 31 days | 3100 ± 170c | 2530 ± 114a | 2810 ± 7b | 2730 ± 75ab | 3020 ± 52c | |

| NH3/NO3 ratio | Initial | 13.82 ± 0.11b | 23.83 ± 0.42d | 13.44 ± 0.09a | 30.4 ± 0.82e | 20.12 ± 0.41c |

| 31 days | 23.97 ± 0.51e | 16.33 ± 0.40d | 11.53 ± 0.21b | 8.63 ± 0.14a | 14.59 ± 0.34c | |

| NO3/NO2 ratio | Initial | 17.55 ± 0.63b | 10 ± 0.43a | 22.5 ± 0.48b | 7.14 ± 0.08a | 10 ± 0.31a |

| 31 days | 13.94 ± 0.43a | 12.47 ± 0.31a | 23.6 ± 0.41b | 14.55 ± 0.113a | 13.48 ± 0.42a |

The numerical values are given as mean ± standard deviation. Values with the same superscript in a row are not significantly different as per Duncan’s multiple range test at probability level P < 0.05

Control PM alone, T1 PM + saw dust, T2 PM + rice husk, T3 PM + saw dust + consortium, T4 PM + rice husk + consortium

Table 6.

Assessment of microbial communities that metabolize nitrogen in the compost with various treatments

| Property | Time | Control | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total heterotrophic bacteria (CFU/g) | Initial | 2.01 × 108 ± 5.7 × 102e | 0.06 × 108 ± 3.2 × 102a | 0.17 × 108 ± 2.4 × 102b | 0.63 × 108 ± 8.1 × 102d | 0.41 × 108 ± 4.0 × 102c |

| 31 days | 10.80 × 106 ± 2.4 × 102e | 0.81 × 106 ± 3.2 × 102b | 2.36 × 106 ± 3.2 × 102c | 0.32 × 106 ± 2.4 × 102a | 6.10 × 106 ± 4.0 × 102d | |

| Uricase producers (CFU/g) | Initial | 450 × 103 ± 2.4 × 102d | 40 × 103 ± 1.6 × 102a | 38 × 103 ± 8.1 × 102a | 27 × 103 ± 4.4 × 102b | 29 × 103 ± 1.6 × 102c |

| 31 days | 3.6 × 103 ± 124b | 0.38 × 103 ± 132a | 0.47 × 103 ± 138a | 0.016 × 103 ± 245c | 0.035 × 103 ± 163d | |

| Ammonifiers (cells/g) | Initial | 63,174 | 62,137 | 60,316 | 57,410 | 55,320 |

| 31 days | 42,163 | 58,108 | 56,765 | 55,167 | 51,720 | |

| Urease producers (cells/g) | Initial | 49,317 | 47,163 | 45,110 | 36,310 | 38,415 |

| 31 days | 34,170 | 41,670 | 42,320 | 32,170 | 35,476 | |

| Ammonia oxidizers (cells/g) | Initial | 115 | 73 | 65 | 140 | 165 |

| 31 days | 73 | 69 | 56 | 176 | 183 | |

| Nitrite oxidizers (cells/g) | Initial | 317 | 68 | 73 | 516 | 631 |

| 31 days | 215 | 65 | 76 | 775 | 931 |

The numerical values are given as mean ± standard deviation. Values with the same superscript in a row are not significantly different as per Duncan’s multiple range test at probability level P < 0.05

Control PM alone, T1 PM + saw dust, T2 PM + rice husk, T3 PM + saw dust + consortium, T4 PM + rice husk + consortium

aThe given data are MPN values from the statistical table available in Woomer (1994)

Changes in each treatment upon composting

A comparison of the levels of various parameters at final stage of composting with that of initial level was made. Significantly, in all the treatments, pH was stable while moisture and C:N ratio were reduced and dry matter was increased by composting (Table 4). The stable pH may be due to the buffering capacity of the composting matrix. For example, the buffering capacity of poultry manure is higher than the dairy manure (Termeer and Warman 1993). In the case of control where poultry manure alone was composted, carbon content was slightly reduced while available nitrogen, nitrate and urea were significantly reduced (p > 0.05) but ammonia:nitrate ratio was significantly increased (73%) indicating its unsuitability for fertilizer application (Table 5). In addition, the microbial profile (Table 6) in terms of bacterial population, uricase and urease producers, ammonifiers, ammonia oxidizers and nitrite oxidizers were reduced upon composting. This clearly indicates the need of amendments to suppress ammonia production and produce a product which will conserve nitrogen (Webster et al. 2006) due to incomplete composting (Elwell et al. 1998).

In the case of T1 treatment (poultry manure and sawdust without bacterial consortium), the level of organic carbon, total carbon, ammonia and ammonia:nitrate ratio decreased while total nitrogen, available nitrogen, nitrate and urea levels increased significantly (Tables 4 and 5). The carbon amendment by the addition of sawdust showed better performance than the control which has poultry manure alone. Microbiologically, bacterial population, uricase and urease producers, and ammonifiers were desirably decreased while population of ammonia oxidizers and nitrite oxidizers were more or less maintained that are expected to be increased (Table 6). In treatment T2 containing poultry manure and rice husk without inoculation of consortium, organic carbon, total carbon and ammonia:nitrate ratio decreased upon composting while ammonia and nitrate levels increased significantly. Further, bacterial population, uricase and urease producers and ammonia oxidizers decreased while the population of nitrite oxidizers was maintained. The observation suggests that this treatment is partly effective due to the lack of increase in the population of nitrite oxidizers. At the same time, the desired decrease in uricase and urease producers and ammonia oxidizers occurred. When compared to rice husk, sawdust (T1) showed a better performance as carbon amendment in terms of biochemical and microbiological profile. Sawdust was also reported as efficient in preserving the organic matter and nitrogen in the compost of poultry manure (Dias et al. 2010).

The above carbon amendments (sawdust and rice husk) were further tested individually along with the added consortial inoculum (T3 and T4 treatments). In the case of composting poultry manure with sawdust and consortium (T3), there was a significant and desired increase in total nitrogen (48%), available nitrogen (96%), nitrate nitrogen (162%) and nitrate:nitrite ratio (103%) along with the population of ammonia oxidizers and nitrite oxidizers (Table 5). As desired, there was a highly significant reduction in C:N ratio (53%), ammonia:nitrate ratio (72%) along with the population of ammonifiers, urease and uricase producers. Organic matter is mineralized after composting, mostly due to the degradation of easily degradable compounds, which are utilized by microorganisms as carbon and nitrogen sources. While degrading organic compounds, microorganisms convert 60–70% carbon to carbon dioxide and utilize the remaining 30–40% for their bodies as cellular components (Barrington et al. 2002). So, this treatment (T3) showed desired changes in terms of increase in beneficial microbes and nitrogen conservation while the population of undesired microbes would have been reduced. In the treatment (T4) containing poultry manure, rice husk and consortium, the level of carbon and available nitrogen and the population of total heterotrophic bacteria, ammonifiers, urease and uricase producers decreased though total nitrogen, nitrate and nitrate:nitrite ratio along with the population of ammonia and nitrite oxidizers increased (Tables 4 and 5). Production of nitrate during composting seems almost exclusively the work of heterotrophic nitrifiers (Eylar and Schmidt 1959; Alexander 1977, Mulvaney 1994). Further, nitrification has been observed in the mixture of gelatin sludge with organic fraction of municipal solid waste and poultry manure when it was enriched with nitrifying bacterial consortium and zeolite (Awasthi et al. 2016). The above trends indicate that the performance of T3 (PM + sawdust + consortium) was better due to the efficacy of composting.

Comparison of composting behaviour among the treatments

Upon composting, desired changes have to be augmented while the undesired changes have to be controlled. For instance, the level of organic carbon, total carbon and C:N ratio should get decreased while total nitrogen should be increased due to composting. Similarly, the levels of available nitrogen, nitrate, nitrite and nitrate:nitrite ratio have to be increased with concomitant increase in the population of ammonia oxidizers (AO) and nitrite oxidizers (NO). Further, the level of ammonia, urea, uric acid, ammonia:nitrate ratio should be kept controlled with concomitant control over the population of urease and uricase producers and ammonifiers. It is imperative that urease and uricase producers and ammonifiers are also essential as a part of the biogeochemical cycling which will enable to keep the level of ammonia in control. Increased level of ammonia will be detrimental and will lead to its release into the environment. Moreover, the population of ammonia and nitrite oxidizers should be increased so as to conserve nitrogen in the form of nitrate preferred by the plants.

When these strategies are applied, the performance of the control (poultry manure alone) was poor while the performance of treatment T3 (poultry manure, sawdust and consortium) was the highest among the five treatments (Tables 4, 5 and 6). Treatment T3 showed better performance in terms of maximum utilization of carbon (organic carbon and total carbon), highest level of total nitrogen, available nitrogen, nitrate and nitrite while lowest level of C:N ratio, ammonia and ammonia:nitrate ratio. The microbiological profile also showed desired changes in terms of the lowest population of ammonifiers and urease producers coupled with the highest population of ammonia and nitrite oxidizers. All these desired changes proved that the performance of microbial consortia along with sawdust is comparatively good. Increased level of nitrogen resulted from the loss of dry weight as carbon dioxide and water evaporation during the mineralization of the organic matter. This correlates with the previous observations on composting experiments (Bernai et al. 1998; Paredes et al. 2002; Meunchang et al. 2005; Alburquerque et al. 2006). The results clearly indicate that the performance of sawdust as carbon amendment was better and the use of microbial consortium definitely enhanced carbon utilization coupled with nitrogen conservation.

Assessment of compost maturity

Assessment of compost maturity is pivotal to obtain the final product. Though various methods are available, lack of increase in temperature after turning (mixing and watering to 60% moisture level), increase in nitrate:nitrite ratio coupled with volume reduction and decrease in the C:N ratio and ammonia:nitrate ratio are used as indicators for determining compost maturity (Khan et al., 2014). C:N ratio between 14 and 24 would be ideal for ready-to-use compost (Benito et al. 2006).

When these parameters were analysed (Table 7), the performance of treatment T3 (poultry manure, sawdust and bacterial consortium) was the highest among treatments. This condition favoured highest reduction in C:N ratio, NH3:NO3 ratio and volume with maximum increase in NO3:NO2 ratio (Table 7). The C:N ratio of this compost was 11.75. As per French standard NFU 44,051, C:N ratio should be greater than 8 in the matured compost. The attainment of higher C:N ratio indicates proper maturation of compost (Zdanevitch and Bour 2011). Moreover, as per EPA Sludge Rule (US EPA 1999), during composting the temperature should reach at least 55 °C and retained for a minimum of 3 days. This will ensure the destruction of pathogens possibly present in the poultry waste. However, in this study, all the treatments reached a temperature greater than 55 °C and retained for more than 3 days (Fig. 1). In the case of T3, temperature rose to 70 °C on the 3rd day and it was retained above 55 °C up to 15th day of composting.

Table 7.

Maturity indices of composts

| Treatments | Percentage reduction in | Percentage increase in NO3:NO2 ratio | Volume reduction (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C:N ratio | NH3:NO3 ratio | |||

| Control | 2.6 | − 73.4 | − 20.6 | 3.3 |

| T1 | 46.3 | 31.5 | 24.7 | 25.3 |

| T2 | 34.7 | 14.2 | 4.9 | 12.0 |

| T3 | 53.5 | 71.6 | 103.7 | 33.9 |

| T4 | 44.4 | 27.5 | 34.8 | 23.4 |

Control PM alone, T1 PM + saw dust, T2 PM + rice husk, T3 PM + saw dust + consortium, T4 PM + rice husk + consortium

In all the treatments after turning, there was no increase in temperature indicating that the compost was matured (Fig. 1). The quality of the composts obtained in this study can be considered comparable to the quality of other composts reported in the literature (De Bertoldi et al. 1985; Zucconi and De Bertoldi 1987; Ayers 1997; Gajalakshmi and Abbasi 2008). Co-composting of poultry manure with barley waste (Guerra-Rodrıguez et al. 2000) or with chestnut burr and leaf litter (Guerra-Rodriguez et al. 2001) took a period of 103 days and reached the C:N ratio of 13. Composting of poultry litter in forced aeration piles resulted in physico-chemical and microbial changes and increase in NO3–N with decrease in NH4–N (Tiquia and Tam 2002). Similar forced aeration composting of PM took a period of 65 days with sawdust (Gao et al. 2010). Composting of poultry manure with rice straw reached maturity in 90 days (Abdelhamid et al. 2004). Co-composting of poultry manure with exhausted olive cake and sesame shells attained stability after 70 days. The final product had low C:N ratio of 14–17 (Sellami et al. 2008). Poultry manure amended paddy straw compost had a C:N ratio of 13.06. It improved soil microbial biomass and nutrient cycling (Gaind and Nain 2010). However, the composting process developed hereby is very rapid and took only 30 days against the reported period of 70–103 days because the process is augmented by employing a desired consortium of microbes.

Influence of the selected compost (T3) on the growth and yield of crop plants

Three crop plants, a cereal (Oryza sativa, rice), a pulse (Vigna radiata, green gram) and an oil seed (Sesamum indicum, sesame) were chosen to study the efficacy of the selected composted manure T3 against recommended chemical fertilizer for each crop (Table 8). The compost treatment (PT3—30 g compost/pot) resulted in significantly higher germination percentage when compared with other treatments (Table 8). The number of leaves was also higher in all the crops tested when compared with chemical fertilizer (PT1). The pod number and length were also higher in green gram when applied with compost (PT3). When compared to other crop plants, the yield of green gram showed the highest increase (78%) by the application of poultry manure compost (PT3) followed by the oilseed crop (sesame, 45%) but not in rice (Table 8). It indicates that the compost application at the rate of 30 g/pot enhanced productivity in green gram and sesame. Addition of compost prepared from poultry manure and oilseed rape cake at the rate of 20 g/pot was reported to increase growth and yield of Faba bean (Abdelhamid et al. 2004).

Table 8.

Growth response of crop plants upon the application of selected compost (obtained from PM + sawdust + bacterial consortium) in comparison with recommended fertilizer

| Crop(s) | Treatment(s) | Germination percent (%) | No. of leaves | Shoot length (cm) | No. of seeds per plant | Yield/plant (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice (Oryza sativa) | Control | 75.0a | 11.6 ± 1.94a | 27.7 ± 1.80a | 133.3 ± 24.49a | 6.7 ± 1.2a |

| PT1 | 91.7a | 22.4 ± 2.83b | 34.5 ± 3.56b | 361.6 ± 36.68c | 18.2 ± 1.8c | |

| PT2 | 93.3a | 26.8 ± 2.75c | 40.2 ± 2.13c | 270.9 ± 53.93b | 13.6 ± 2.7b | |

| PT3 | 100a | 43.7 ± 3.60d | 50.8 ± 2.69d | 348.3 ± 72.59c | 17.4 ± 3.6c | |

| Green gram (Vigna radiata) | Control | 73a | 7.1 ± 1.30a | 15.4 ± 2.16a | 19.1 ± 5.24a | 2.4 ± 0.7a |

| PT1 | 80a | 11.0 ± 2.79b | 30.4 ± 3.37b | 40.5 ± 16.94b | 5.0 ± 2.1b | |

| PT2 | 100a | 12.4 ± 1.99bc | 31.9 ± 2.96b | 35.2 ± 10.81b | 4.4 ± 1.3b | |

| PT3 | 100a | 14.2 ± 2.5c | 46.0 ± 3.38c | 70.8 ± 18.27c | 8.9 ± 2.3c | |

| Sesame (Sesamum indicum) | Control | 67a | 11.8 ± 2.15a | 32.4 ± 3.53a | 162.5 ± 39.52a | 4.9 ± 1.2a |

| PT1 | 73ab | 19.7 ± 2.61b | 42.3 ± 3.66b | 385.0 ± 71.72c | 11.6 ± 2.1c | |

| PT2 | 93ab | 18.6 ± 2.17b | 41.7 ± 4.00b | 282.8 ± 56.08b | 8.5 ± 1.7b | |

| PT3 | 100b | 25.7 ± 3.20c | 51.4 ± 3.01c | 532.0 ± 102.57a | 16.0 ± 3.0d |

The numerical values except germination percent are given as mean ± standard deviation. Values with the same superscript in a row are not significantly different as per Duncan’s multiple range test at probability level P < 0.05

Control without fertilizer/compost, PT1 recommended chemical fertilizer, PT2 15 g compost/pot, PT3 30 g compost/pot

Conclusions

The findings demonstrate the exploitation of native microbiome consisting of three Bacillus species to form a complementary consortium inheriting five metabolic properties required for the efficient composting of PM combined with cheap agriculture residues as carbon source. For the first time, development of a single step and rapid composting of PM in 30 days was made. There was a better performance of co-composting PM with sawdust and the developed bacterial consortium. Ability of this compost in supporting the growth and yield of a pulse crop and an oilseed crop could be established.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Council for Scientific and Industrial research (CSIR), Government of India, for the award of Senior Research Fellowship to one of them (S.K.) and M/s. Ilango Poultry Farms (P) Limited, M/s. Kaliappan Poultry Farms (P) Limited and M/s. Samithurai Poultry Farms (P) Limited, Namakkal, India, for enabling the sampling of poultry manure.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Abdelhamid MT, Horiuchi T, Oba S. Composting of rice straw with oilseed rape cake and poultry manure and its effects on faba bean (Vicia faba L.) growth and soil properties. Bioresour Technol. 2004;93:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alburquerque JA, Gonzálvez J, García D, et al. Composting of a solid olive-mill by-product (“alperujo”) and the potential of the resulting compost for cultivating pepper under commercial conditions. Waste Manag. 2006;26:620–626. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alumot E, Bielorai R. Colorimetric determination of uric acid in poultry excreta and in mixed feeds. J Assoc Off Anal Chem. 1979;62:1350–1352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Public Health Association . Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. Washington: American Water Works Association and Water Environment Federation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Atlas RM, Parks LC. Handbook of microbiological media. Tokyo: CRC Press; 2004. p. 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi MK, Pandey AK, Bundela PS, Wong JWC, Li R, Zhang Z. Co-composting of gelatin industry sludge combined with organic fraction of municipal solid waste and poultry waste employing zeolite mixed with enriched nitrifying bacterial consortium. Biores Technol. 2016;213:181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers V (1997) Farmer composting of cotton gin trash. In: Proceedings beltwide cotton conferences, vol. II. New Orleans. pp 1615–1616

- Barrington S, Choinière D, Trigui M, et al. Effect of carbon source on compost nitrogen and carbon losses. Bioresour Technol. 2002;83:189–194. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8524(01)00229-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito M, Masaguer A, Moliner A, et al. Chemical and physical properties of pruning waste compost and their seasonal variability. Bioresour Technol. 2006;97:2071–2076. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernai MP, Paredes C, Sanchez-Monedero MA. Maturity and stability parameters of composts prepared with a wide range of organic wastes. Bioresour Technol. 1998;63:91–99. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8524(97)00084-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JM, Mulvaney CS. Nitrogen-total. In: Page AL, Miller RH, Keeney DR, editors. Methods of soil analysis: part 2. Chemical and microbiological properties. Madison: SSSA Book Ser. 5; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Burgos S, Burgos SA. Environmental approaches to poultry feed formulation and management. Int J Poult Sci. 2006;5:900–904. doi: 10.3923/ijps.2006.900.904. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlile FS. Ammonia in poultry houses: a literature review. Worlds Poult Sci J. 1984;40:99–113. doi: 10.1079/WPS19840008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo DA, Maroon M, Schrader LE. Rapid colorimetric determination of nitrate in plant tissue by nitration of salicylic acid. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. 1975;6:71–80. doi: 10.1080/00103627509366547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y. The fungi of wheat straw compost: II biochemical and physiological studies. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1967;50:667–677. doi: 10.1016/S0007-1536(67)80098-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Hudson HJ. The fungi of wheat straw compost—ecological studies. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1967;50:649–667. doi: 10.1016/S0007-1536(67)80097-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Bertoldi M, Vallini G, Pera A, et al. Comparison of three windrow compost systems. Biocycle. 1982;23:45–50. [Google Scholar]

- de Bertoldi MD, Vallini GE, Pera A. The biology of composting: a review. Waste Manag Res. 1983;1:157–176. doi: 10.1177/0734242X8300100118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Bertoldi MD, Vallini GE, Pera A. Technological aspects of composting including modelling and microbiology. In: Gasser JKR, editor. Composting of agricultural and other wastes. London: Elsevier Applied Science Publishers; 1985. pp. 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Dias BO, Silva CA, Higashikawa FS, et al. Use of biochar as bulking agent for the composting of poultry manure: effect on organic matter degradation and humification. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101:1239–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz MJ, Madejon E, Ariza J, et al. Co-composting of beet vinasse and grape marc in windrows and static pile systems. Compost Sci Util. 2002;10:258–269. doi: 10.1080/1065657X.2002.10702088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap CE, Chiang LC. Cellulose degradation: a common link. In: Shuler ML, editor. Utilization and recycle of agricultural wastes and residues. Boca Raton: CRC Press Inc; 1980. p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Elwell DL, Keener HM, Carey DS, et al. Composting unamended chicken manure. Compost Sci Util. 1998;6:22–35. doi: 10.1080/1065657X.1998.10701918. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eylar OR, Schmidt EL. A survey of heterotrophic micro-organisms from soil for ability to form nitrite and nitrate. Microbiology. 1959;20:473–481. doi: 10.1099/00221287-20-3-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauziah SH, Agamuthu P. Sustainable household organic waste management via vermicomposting. Malaysian J Sci. 2009;28(2):135–142. doi: 10.22452/mjs.vol28no2.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fong M, Wong JW, Wong MH. Review on evaluation of compost maturity and stability of solid waste. Shanghai Environ Sci. 1999;18:91–93. [Google Scholar]

- Fontenot JP, Smith LW, Sutton AL. Alternative utilization of animal wastes. J Anim Sci. 1983;57:221–233. [Google Scholar]

- Foss Tecator (2003).The determination of nitrogen according to kjeldahl using block digestion and steam distillation. FOSS Analytical AB, Application note AN300. Sweden

- Gaind S, Nain L. Exploration of composted cereal waste and poultry manure for soil restoration. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101:2996–3003. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajalakshmi S, Abbasi SA. Solid waste management by composting: state of the art. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol. 2008;38:311–400. doi: 10.1080/10643380701413633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Li B, Yu A, Liang F, et al. The effect of aeration rate on forced-aeration composting of chicken manure and sawdust. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101:1899–1903. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golueke CG. When is compost” safe”? Biocycle. 1982;23:28–38. [Google Scholar]

- González CE, Gil E, Fernández-Falcón M, Hernández MM. Water leachates of nitrate nitrogen and cations from poultry manure added to an Alfisol Udalf soil. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2009;202:273–288. doi: 10.1007/s11270-008-9975-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith A. SPSS for dummies. Hoboken: Wiley Publishing Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-Rodrıguez E, Vázquez M, Dıaz-Ravina M. Co-composting of barley wastes and solid poultry manure. Bioresour Technol. 2000;75:223–225. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8524(00)00069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-Rodrıguez E, Diaz-Ravina M, Vazquez M. Co-composting of chestnut burr and leaf litter with solid poultry manure. Bioresour Technol. 2001;78:107–109. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8524(00)00159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haga K. Development of composting technology in animal waste treatment-review. Asian Aust J Anim Sci. 1999;12:604–606. doi: 10.5713/ajas.1999.604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartel PG, Hagedorn C. Microtechnique for isolating fecal coliforms from soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;46:518–520. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.2.518-520.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiorns WD, Hastings RC, Head IM, et al. Amplification of 16S ribosomal RNA genes of autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria demonstrates the ubiquity of nitrosospiras in the environment. Microbiology. 1995;141:2793–2800. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-11-2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyappan P, Karthikeyan S, Sekar S. Changes in the composition of poultry farm excreta (PFE) by the cumulative influence of the age of birds, feed and climatic conditions and a simple mean for minimizing the environmental hazard. Int J Environ Sci. 2011;1:847–859. [Google Scholar]

- Karthikeyan S, Iyappan P, Sekar S. Effect of seasons on the microbiological and biochemical composition of poultry farm excreta. Indian J Poult Sci. 2011;46:99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kasana RC, Salwan R, Dhar H. A rapid and easy method for the detection of microbial cellulases on agar plates using Gram’s iodine. Curr Microbial. 2008;57:503–507. doi: 10.1007/s00284-008-9276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan N, Clark I, Sánchez-Monedero MA. Maturity indices in co-composting of chicken manure and sawdust with biochar. Bioresour Technol. 2014;168:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.02.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd PS, Prieto-Fernández A, Monterroso C. Rhizosphere microbial community and hexachlorocyclohexane degradative potential in contrasting plant species. Plant Soil. 2008;302:233–247. doi: 10.1007/s11104-007-9475-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JM, Lim WJ, Suh HJ. Feather-degrading Bacillus species from poultry waste. Process Biochem. 2001;37:287–291. doi: 10.1016/S0032-9592(01)00206-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar BL, Sai Gopal DVR. Effective role of indigenous microorganisms for sustainable environment. 3 Biotech. 2015;5:867–876. doi: 10.1007/s13205-015-0293-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyimo HJ, Pratt RC, Mnyuku RS. Composted cattle and poultry manures provide excellent fertility and improved management of gray leaf spot in maize. Field Crops Res. 2012;126:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2011.09.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaka E, Nomura N, Nakajima-Kambe T. A simple screening procedure for heterotrophic nitrifying bacteria with oxygen-tolerant denitrification activity. J Biosci Bioeng. 2003;95:409–411. doi: 10.1016/S1389-1723(03)80077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta S, Nautiyal CS. An efficient method for qualitative screening of phosphate-solubilizing bacteria. Curr Microbiol. 2001;43:51–56. doi: 10.1007/s002840010259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunchang S, Panichsakpatana S, Weaver RW. Co-composting of filter cake and bagasse; by-products from a sugar mill. Bioresour Technol. 2005;96:437–442. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2004.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra M, Sahu RK, Sahu SK. Growth, yield and elements content of wheat (Triticum aestivum) grown in composted municipal solid wastes amended soil. Environ Dev Sustain. 2009;11:115–126. doi: 10.1007/s10668-007-9100-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Misra, R.V., Roy, R.N., Hiraoka, H., 2003. On-farm composting methods. FAO corporate document repository. http://www.fao.org/docrep/007/y5104e/y5104e00.HTM. Accessed 07 Sept 2014

- Moore PA. Best management practices for poultry manure utilization that enhance agricultural productivity and reduce pollution. In: Hatfield JL, Stewart BA, editors. Animal waste utilization: effective use of manure as a soil resource. Chelsea: Ann Arbor Press; 1998. pp. 80–123. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvaney RL. Nitrogen- inorganic forms. In: Sparks DL, editor. Methods of soil analysis: part 3-Cemical methods. Madison: Soil Science Society of America Book Series 5; 1994. pp. 1123–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvaney RL, Bremner JM. A modified diacetyl monoxime method for colorimetric determination of urea in soil extracts. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. 1979;110:1163–1170. doi: 10.1080/00103627909366969. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthuvel P, Udayasoorian C. Soil, plant, water and agrochemical analysis. Coimbatore: Tamil Nadu Agricultural University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nodar R, Acea MJ, Carballas T. Microbial populations of poultry pine-sawdust litter. Biol Wastes. 1990;33:295–306. doi: 10.1016/0269-7483(90)90133-D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ogunwande GA, Osunade JA, Adekalu KO. Nitrogen loss in chicken litter compost as affected by carbon to nitrogen ratio and turning frequency. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99:7495–7503. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’neill DH, Phillips VR. A review of the control of odour nuisance from livestock buildings: part 3, properties of the odorous substances which have been identified in livestock wastes or in the air around them. J Agricul Eng Res. 1992;53:23–50. doi: 10.1016/0021-8634(92)80072-Z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes C, Bernal MP, Cegarra J, et al. Bio-degradation of olive mill wastewater sludge by its co-composting with agricultural wastes. BioresourTechnol. 2002;85:1–8. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8524(02)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J, Combs SM, Hoskins B, et al. Recommended methods of manure analysis. Madison: University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension Publishing; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rynk R, Sailus M, Popow JS, et al. On-farm composting handbook. Northeast regional agricultural engineering service. New York: Cooperative Extension; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Schefferle HE. The decomposition of uric acid in built up poultry litter. J Appl Microbiol. 1965;28:412–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1965.tb02171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleifer KH (2009) Phylum XIII. Firmicutes, Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology, The Firmicutes, Springer Science & Business Media, New York, pp. 19–128

- Sekar S, Karthikeyan S, Iyappan P. Trends in patenting and commercial utilisation of poultry farm excreta. Worlds Poult Sci J. 2010;66:533–572. doi: 10.1017/S0043933910000607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sellami F, Jarboui R, Hachicha S. Co-composting of oil exhausted olive-cake, poultry manure and industrial residues of agro-food activity for soil amendment. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99:1177–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar K, Kumar VR, Jagatheesan PR, et al. Seasonal variations in composting process of dead poultry birds. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99:3708–3713. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbiah BV. A rapid procedure for the determination of available nitrogen in soils. Curr Sci. 1956;25:259–260. [Google Scholar]

- Termeer WC, Warman PR. Use of mineral amendments to reduce ammonia losses from dairy-cattle and chicken manure slurries. Biores Technol. 1993;44:217–222. doi: 10.1016/0960-8524(93)90155-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tiquia SM, Tam NF. Characterization and composting of poultry litter in forced-aeration piles. Process Biochem. 2002;37:869–880. doi: 10.1016/S0032-9592(01)00274-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tweib SA, Rahman RA and Kalil MS (2011) A Literature Review on the Composting. In: International conference on environment and industrial innovation. IACSIT Press, Singapore, pp 124–127

- US EPA (1999) Control of pathogens and vector attraction in sewage sludge EPA/625/R-92/013 Revised October 1999. United States environmental protection agency, office of research and development, national risk management laboratory, center for environmental research information, Cincinnati, OH

- Walkley A, Black IA. An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 1934;37:29–38. doi: 10.1097/00010694-193401000-00003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Webster AB, Thompson SA, Hinkle NC. In-house composting of layer manure in a high-rise, tunnel-ventilated commercial layer house during an egg production cycle. J Appl Poult Res. 2006;15:447–456. doi: 10.1093/japr/15.3.447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson SR. Plant nutrient and economic values of animal manures 1, 2. J Anim Sci. 1979;48:121–133. doi: 10.2527/jas1979.481121x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woomer PL. Most probable number counts. In: Weaver RW, Angle S, Bottomley P, editors. Methods of soil analysis, part 2-Microbiological and biochemical properties. Madison: SSSA Book Ser 5; 1994. pp. 59–79. [Google Scholar]

- Xie K, Jia X, Xu P, et al. Improved composting of poultry feces via supplementation with ammonia oxidizing archaea. Bioresour Technol. 2012;120:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaowu H, Yuhei I, Motoyuki M, et al. Nitrous oxide emissions from aerated composting of organic waste. Environ Sci Tech. 2001;35:2347–2351. doi: 10.1021/es0011616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zdanevitch I and Bour O (2011) Quality of composts from municipal biodegradable waste of different origins. In: Cossu R, He P, Kjeldsen P, Matsufuji Y, Reinhart D and Stegmann R. 13. International waste management and landfill symposium (Sardinia 2011), Oct 2011, Cagliari, Italy, CISA Publisher, Italy, pp 87–88

- Zuberer DA. Chapter 8. Recovery and enumeration of viable bacteria. In: Weaver RW, Angle S, Bottomley P, editors. Methods of soil analysis, part 2-Microbiological and biochemical properties. Madison: SSSA Book Ser. 5; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Zucconi F, De Bertoldi M, et al. Compost specifications for the production and characterization of compost from municipal solid waste. In: de Bertoldi M, Ferranti MP, LHermite P, et al., editors. Compost: production, quality and use. Barking: Elsevier; 1987. pp. 30–50. [Google Scholar]