Abstract

3-Phenyllactic acid (PLA) is a novel and natural antimicrobial compound. However, the concentration of PLA produced by native microbes was rather low. To enhance the production of PLA of Lactobacillus plantarum AB-1, the microcapsules of L. plantarum AB-1 cells with a high quorum-sensing capacity was established and investigated. In addition, the relation between PLA production and quorum sensing was further investigated and confirmed by adding the exogenous 4,5-dihydroxy-2,3-pentanedione (DPD, AI-2 precursor). The results indicated that the PLA production of L. plantarum AB-1 in microencapsulated cells (MC cells) was higher than that of the free cells, and the lactate dehydrogenase activity, autoinducer-2 (AI-2) levels and the relative expression of the luxS gene were also significantly increased in MC cells (P < 0.05). In addition, the cell growth, AI-2 levels and PLA production of L. plantarum AB-1 were also significantly promoted after adding 24 μM exogenous DPD. The results suggest that the PLA production of L. plantarum was partly regulated by the AI-2/LuxS system, and microencapsulation can increase the local AI-2 level and enhance QS capacity, which are beneficial to PLA production. The results may provide a new insight and experimental basis for the industrial production of PLA.

Keywords: Lactobacillus plantarum, Microencapsulation, 3-Phenyllactic acid, Quorum sensing

Introduction

3-Phenyllactic acid (PLA) is a novel and natural antimicrobial compound with broad-spectrum activity against both bacteria and fungi. PLA has greater efficient antimicrobial activity than that of other organic acids due to its dual mechanisms (Ning et al. 2017). PLA is mainly produced by lactic acid bacteria (LAB) through the degradation of phenylalanine. During this process, phenylalanine is transaminated to phenylpyruvic acid (PPA), and then, PPA is reduced further to PLA (Vermeulen et al. 2006). The physiological PLA was produced as a secondary metabolite, which was accumulated then transferred to external environment. Meanwhile, the PLA showed no significant physiological function to the organism itself. Although several LABs have shown PLA productivity, low yield (less than 1 mM) is the main restriction for commercial production. Microbial biotransformation based on metabolic engineering is one of the available biological approaches for improving the production of PLA (Zhao et al. 2018); however, the high cost and safety of this method also restricted its application in commercial production. Therefore, the development of efficient and inexpensive biological systems that can produce PLA is necessary.

Quorum sensing (QS) is a cell–cell communication mechanism that regulates the expression of certain target genes with autoinducers in a cell density-dependent manner (Miller and Bassler 2001). The bacteriocin biosynthesis (Jia et al. 2017) and resistance to various environmental stresses (Gu et al. 2018) of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are regulated by quorum-sensing autoinducer-2 (AI-2)/luxS system. The bacterial QS capacity can be improved by spatial constraints, which can influence cell–cell communication by affecting both the diffusion of released signaling molecules and the spatial distribution of cells (Gao et al. 2016c). Thus, this study aims to investigate the relationship between PLA production and the QS of Lactobacillus Plantarum AB-1 to improve PLA production through the enhancement of the QS capacity of L. Plantarum AB-1 by microencapsulation.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains

Lactobacillus plantarum AB-1 was gifted by Prof. Heping Zhang and was cultured in a DeMan-Rogosa-Sharpe (MRS) medium. Vibrio harveyi BB152, Vibrio harveyi BB170 and Vibrio harveyi MM77 were gifted by Prof. Xiaohua Zhang and were cultured in the autoinducer bioassay (AB) medium with aeration.

Preparation of the microcapsules of L. Plantarum AB-1

The microcapsules of L. Plantarum AB-1were prepared according to the method of Gao et al. (2016b). Firstly, sodium alginate solution of 1.5% (w/v) was prepared by being dissolved in 0.9% (w/v) NaCl solution and then filtered through a 0.22 μm sterile membrane filter. L. plantarum AB-1, in mid-exponential phase, were centrifuged (8000 rpm, 5 min) and suspended in sodium alginate solution. About 1 mL suspension was extruded through a 0.5 mm external diameter needle into 1.1% (w/v) CaCl2 solution to form calcium alginate beads. The beads were hardened for about 30 min and collected. Afterwards the beads were put into chitosan solution (0.5% w/v) at the beads/solution ratio of 1:10 (v/v) to form alginate-chitosan microcapsule membrane for 20 min, followed by rinsing with 0.9% (w/v) NaCl solution to remove the excess chitosan. After that, 0.15% alginate solution was added to counteract charges on the membranes and formed another membrane for 20 min. The microcapsules were collected, rinsed and put into 0.055 M sodium citrate for 5 min to obtain the microcapsules; then, the microencapsulated cells (MC cells) were formed and cultured in an MRS medium.

Cell growth assay

The microencapsulated cells and the free cells were cultured at the final concentrations of 106 colony-forming units per mL (cfu mL−1) and then were inoculated from the same seed culture. The cells were grown into their logarithmic phase. After being cultured for 48 h, all the microcapsules of the microencapsulated cell group were broken up with a chemical method (Xue et al. 2004); then, the L. plantarum AB-1 cells were released and measured. The cell growth was expressed as μg L−1.

Morphology of microcapsules

Optical morphology of the microcapsules entrapped by the L. plantarum AB-1 cells was obtained under an inverted research microscope.

3-Phenyllactic acid concentration detection

The cells that were cultured for 48 h were centrifuged at 10,000g, 4 °C for 10 min and filtrated with a sterile 0.22 μm filter. The cell-free supernatant was obtained and analyzed by using reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) equipped with an Agilent Zorbax SB-C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm). 3-Phenyllactic acid (PLA) was analyzed with an SPD-20A ultraviolet detector (Shimadzu LC-20AT, Japan) at 210 nm according to the procedure described by Li et al. (2008).

Autoinducer-2 activity detection

Autoinducers-2 (AI-2) activity was detected as previously described (Surette and Bassler 1998). The reporter strain V. harveyi BB170 was cultured overnight (12–16 h) at 30 °C with shaking (180 rpm) in an autoinducer bioassay (AB) medium, then the cells were diluted 1:5000 in fresh AB medium (approximately 105 cfu mL−1). Cultured samples were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm, 4 °C for 10 min and filtrated with a 0.22 µm sterile filter, then the cell-free culture supernatant mixed with diluted V. harveyi BB170 at a ratio of 1:100 (v/v).The mixtures were incubated at 30 °C with shaking (180 rpm). Either samples or control luminescence was measured every 30 min for 6 h at a wavelength of 490 nm using a Multi-Detection Reader (SynergyMx, Biotek, USA) in the luminescence mode. Relative luminescence units (RLU) were used to quantify AI-2 activity when the luminescence of the negative control was lowest.

Lactate dehydrogenase activity detection

The lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity was measured using a Cytotoxicity Detection KitPLUS [LDH]. The 100 µL cell-free supernatant and 100 µL reaction mixture of the Cytotoxicity Detection KitPLUS[LDH] were added into each well of 48-well flat-bottom polystyrene plates (Costar, Corning, NY). The plates were incubated statically at 37 °C for 1 h and then were detected at a wavelength of 490 nm using a Multi-Detection Reader (SynergyMx, Biotek, USA).

LuxS gene relative expression

The free and microencapsulated cells that had been cultured for 9 h were harvested for RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted using the Bacteria Total RNA Isolation Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription was conducted using a 5X All-In-One RT MasterMix with AccuRT Genomic DNA Removal Kit according to the manufacturer’s instruction, and the synthesis of the cDNA was performed by using an A300 Fast Thermal Cycler PCR instrument (LongGene, China). The qRT-PCR amplifications were performed with at least 3 biological replicates using an EVAGreen 2X qPCR MasterMix-No Dye Kit (ABM, Canada) and the CFX connect™ real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad, USA). The housekeeping gene 16S rRNA was used as a control for normalization because its stable expression, and the luxS and 16S rRNA primer sequences are shown in the Table 1. The relative expression is to compare the differences in expression between the target transcripts of treated and untreated samples. The transcriptional level of luxS was normalized to the 16S rRNA gene as the relative expression level of treated and untreated samples (MC cells and free cells group, DPD added and non-DPD added group). A relative quantification method was used for data analysis and 2−ΔΔCq value was used to determine the relative fold changes.

Table 1.

Primer sequences of luxS and 16s rRNA gene

| Gene name | Oligonucleotide sequence (5′–3′) | |

|---|---|---|

| 16s rRNA | Forward | CGTAGGTGGCAAGCGTTGTCC |

| Reverse | CGCCTTCGCCACTGGTGTTC | |

| luxS | Forward | CGGATGGATGGCGTGATTGACTG |

| Reverse | CTTAGCAACTTCAACGGTGTCATGTTC | |

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated at least in triplicate and the data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation. The least significant difference (LSD) procedure was used to test for differences between the means. The statistical analysis was performed by using SPSS software (SPSS Inc, USA), and all the figures were made by Origin 8.0 (Origin Lab, USA).

Results and discussion

Effects of microencapsulation on cell growth, AI-2 levels and the PLA production of Lactobacillus plantarum AB-1

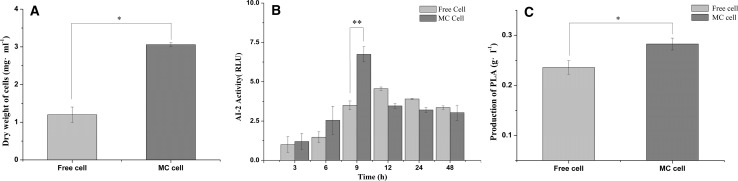

The previous reports showed that the spatial distribution of cells plays a crucial role in bacterial QS (Gao et al. 2016c). The results indicated that the cell growth in microencapsulated cells (MC cells) increased rapidly during incubation. The total aerobic plate count of L. plantarum AB-1 in MC reached 27.1 × 109 cfu mL−1 after an incubation time of 48 h and was 30.1 times higher than that of the free cells (Fig. 1a, P < 0.01). The PLA production of L. plantarum AB-1 in MC cells was 19.96% higher than that of the free cells at the incubation time of 48 h (Fig. 1c, P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Effects of microencapsulation on cell growth (a), autoinducer-2 (AI-2) levels (b) and 3-phenyllactic acid (PLA) of Lactobacillus plantarum AB-1 after incubation of 48 h. Microencapsulated cell: MC cell. Relative luminescence units (RLU) were used to quantify AI-2 activity. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

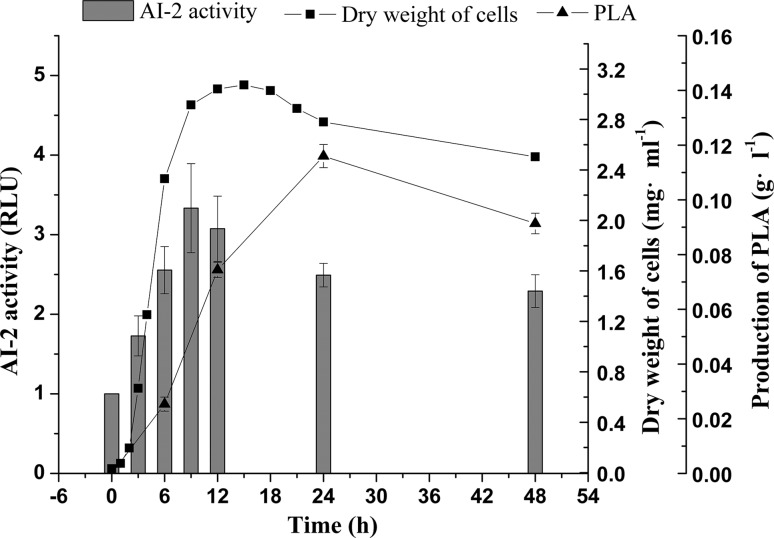

Meanwhile, the AI-2 activity of MC cells was significantly (P < 0.05) higher than that of free cells at the incubation time of 9 h (Fig. 1b). The accumulations of AI-2 and PLA were unsynchronized, and the maximum point of the AI-2 levels appeared earlier than that of the PLA levels (Fig. 2). Unsynchronized accumulation is a phenomenon that identified with the QS theory, which believed that the autoinducers accumulation triggered bacterial QS performance. Similar results also reported that the maximum point of the signaling molecule levels appeared earlier than did certain characteristics of microorganisms (Gao et al. 2016a). The higher production of PLA in MC cells might be due to the increase in the AI-2 levels. In addition, we also considered influence of the encapsulation matrix on the QS capacity. Recently, chitosan was reported having antibacterial and anti-quorum sensing activity whereas sodium alginate did not. The QS dependent phenotype virulence factors and biofilms was significantly reduced in the influence of chitosan (Muslim et al. 2017). Interestingly, it seemed that chtiosan showed no inhibitions when it diffused into sodium alginate network and formed independent structure by polyelectrolyte reaction.

Fig. 2.

The changes of cell growth, autoinducer-2 (AI-2) levels and 3-phenyllactic acid (PLA) production of Lactobacillus plantarum AB-1 during incubation. Relative luminescence units (RLU) were used to quantify AI-2 activity

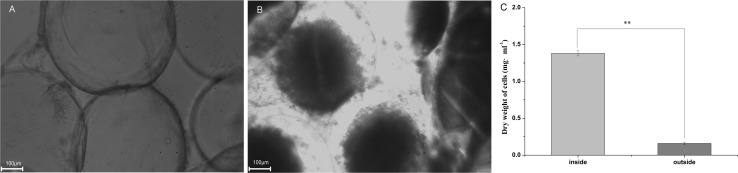

Optical images of the microcapsules of L.plantarum AB-1

The microcapsules of L. plantarum AB-1 were spherical, complete, smooth, and evenly dispersed in a solution (Fig. 3a, b). The average diameter of the microcapsules was approximately 500 µm, and the total aerobic plate count inside of the MC cells was significantly higher than that of the outside of the MC cells (Fig. 3c, P < 0.01). The result was in agreement with Fig. 2a and was also in agreement with previous reports that microcapsule-entrapped low-density cells were able to improve probiotic viability and facilitate stress resistance (Gao et al. 2016b).

Fig. 3.

Optical images of Lactobacillus plantarum AB-1 microcapsules (106 cfu mL−1) at the incubation times of 0 h (a) and 48 h (b) with an aerobic plate count of L. plantarum AB-1 inside and outside of microcapsules after incubation of 48 h (c). **P < 0.01

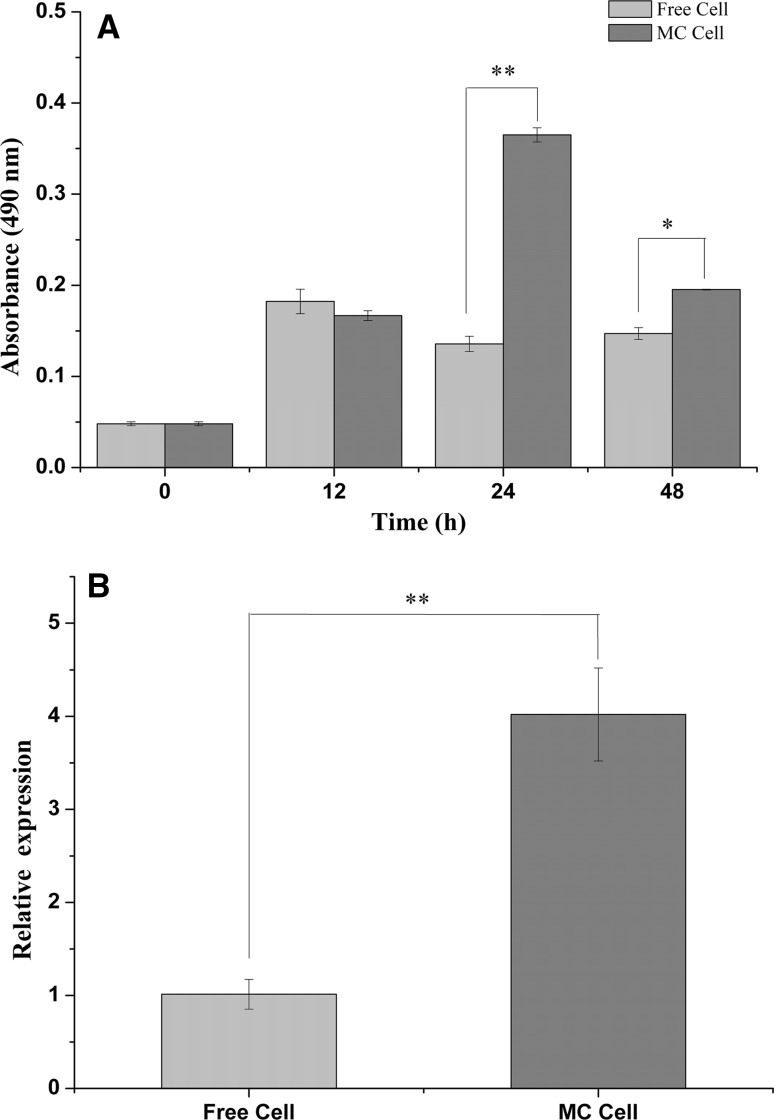

Effects of microencapsulation on LDH activity and the luxS gene expression of L. plantarum AB-1

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was the main enzyme for producing PLA from phenylpyruvic acid (PPA) in lactobacillus (Yu et al. 2014). The results indicated that the LDH activity of L. plantarum AB-1 in MC cells was significantly higher than that of the free cells at the incubation times of 24 h and 48 h (Fig. 4a, P < 0.05), which was consistent with PLA production (Fig. 1c), indicating that both the LDH activity and PLA biosynthesis were regulated in the MC cells due to the effects of spatial constraints.

Fig. 4.

Effects of microencapsulation on lactate dehydrogenase activity after incubation of 48 h (a) and the luxS gene relative expression (b) of Lactobacillus plantarum AB-1 after incubation of 9 h. Microencapsulated cell: MC cell. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

Given that AI-2 might play an important role in the synthesis of PLA, the luxS gene might be involved in PLA production (Pereira et al. 2013). The results confirmed that the relative expression of the luxS gene in MC cells was significantly higher than that of the free cells (Fig. 4b, P < 0.01).

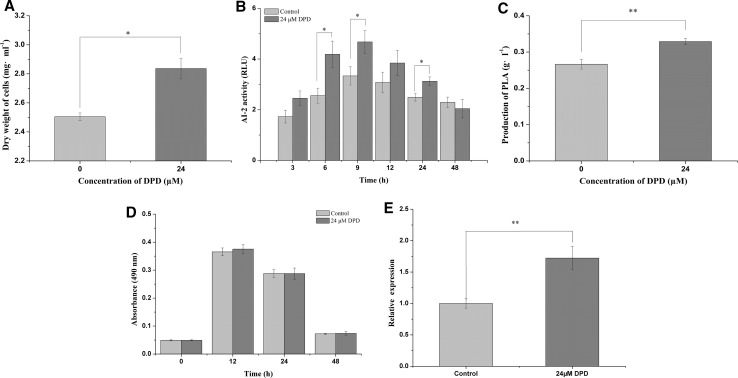

The effect of exogenous DPD on cell growth, AI-2 levels, PLA production, LDH activity and the luxS gene expression of L. plantarum AB-1

DPD, 4,5-dihydroxy-2,3-pentanedione, was an autoinducer precursor of AI-2. To further confirm the above results, exogenous DPD was added when L. plantarum AB-1 was incubated in vitro. The results showed that the growth and PLA production of L. plantarum AB-1were significantly increased upon adding 24 μM DPD (Fig. 5a, c), and the PLA production of L. plantarum AB-1 was 23.44% higher than that of the control (0.328 g L−1 vs. 0.266 g L−1, respectively) (P < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Effects of exogenous 4,5-dihydroxy-2,3-pentanedione (DPD, precursor of autoinducer-2) on the cell growth (a), autoinducer-2 (AI-2) levels (b) and 3-phenyllactic acid (PLA) production (c), lactate dehydrogenase activity (d) after incubation of 48 h and luxS gene relative expression (f) of Lactobacillus plantarum AB-1 after incubation of 9 h. Relative luminescence units (RLU) were used to quantify AI-2 activity. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

At the same time, the AI-2 levels and the luxS gene expression of L. plantarum AB-1 were also significantly increased upon adding 24 μM DPD (Fig. 5b, f). The results indicated that microencapsulation plays similar roles to that of exogenous AI-2 in regulating the behavior of L. plantarum AB-1, which indicated that the PLA production in MC cells might be regulated by the AI-2/LuxS system.

It’s widely believed that QS can regulate bacteria growth and metabolism, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Flickinger et al. 2011) and Shewanella baltica (Jie et al. 2018). PLA production levels may be relevant to the complicated energy transduction (glucose metabolism), different enzyme system and the influence of peptide supply and cosubstrate (Vermeulen et al. 2006; Mu et al. 2012). PLA is mainly produced by lactic acid bacteria (LAB) through the degradation of phenylalanine. During this process, phenylalanine is transaminated to phenylpyruvic acid (PPA), and then, PPA is reduced further to PLA. In addition, the α-ketoglutarate commonly played a role as the amino group acceptor during the transamination reaction and was supplied by glucose metabolism (tricarboxylic acid cycle, TAC) in most LAB strains. Interestingly, Vermeulen et al (2006) reported that the addition of α-ketoglutarate acid strongly increased PLA production by 5–30%, which was consistent with the result of 19.96% in our work. Thus, the LuxS/AI-2 QS system might regulate cell growth, glucose metabolism and LDH activity of L. plantarum AB-1, which finally contributed to the production of 3-phenyllactic acid (PLA).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the 3-phenyllactic acid (PLA) production of Lactobacillus plantarum AB-1 was partly regulated by the LuxS/AI-2 QS system. The PLA production of L. plantarum AB-1 can be enhanced by microencapsulation or by adding exogenous 4,5-dihydroxy-2,3-pentanedione (DPD) in vitro. The microencapsulation of bacteria was an efficient way to improve the PLA production of L. plantarum AB-1.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China (ZR2016CM24).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xiaoyuan Yang and Jianpeng Li have contributed equally to this work and should be considered joint first authors.

References

- Flickinger ST, Copeland MF, Downes EM, Braasch AT, Tuson HH, Eun YJ. Quorum sensing between pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms accelerates cell growth. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(15):5966–5975. doi: 10.1021/ja111131f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Song H, Liu X, Yu W, Ma X. Improved quorum sensing capacity by culturing Vibrio harveyi in microcapsules. J Biosci Bioeng. 2016;121(4):406–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Song H, Zheng H, Ren Y, Li S, Liu X, Yu W, Ma X. Culture of low density E. coli cells in alginate–chitosan microcapsules facilitates stress resistance by up-regulating luxS/AI-2 system. Carbohydr Polym. 2016;141:160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Zheng H, Ren Y, Lou R, Wu F, Yu W, Liu X, Ma X. A crucial role for spatial distribution in bacterial quorum sensing. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34695. doi: 10.1038/srep34695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Li B, Tian J, Wu R, He Y. The response of LuxS/AI-2 quorum sensing in Lactobacillus fermentum 2–1 to changes in environmental growth conditions. Ann Microbiol. 2018;68(5):287–294. doi: 10.1007/s13213-018-1337-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia FF, Pang XH, Zhu DQ, Zhu ZT, Sun SR, Meng XC. Role of the luxS gene in bacteriocin biosynthesis by Lactobacillus plantarum KLDS1.0391: a proteomic analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:13871. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13231-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jie J, Yu H, Han Y, Liu Z, Zeng M. Acyl-homoserine-lactones receptor LuxR of Shewanella baltica involved in the development of microbiota and spoilage of refrigerated shrimp. J Food Sci Technol. 2018;55(7):2795–2800. doi: 10.1007/s13197-018-3172-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Jiang B, Pan B, Mu W, Zhang T. Purification and partial characterization of Lactobacillus species SK007 lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) catalyzing phenylpyruvic acid (PPA) conversion into phenyllactic acid (PLA) J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:2392–2399. doi: 10.1021/jf0731503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing in bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55(1):165–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu W, Yu S, Zhu L, Zhang T, Jiang B. Recent research on 3-phenyllactic acid, a broad-spectrum antimicrobial compound. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;95(5):1155–1163. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4269-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muslim SN, Imsa K, Anm A, Salman BK, Ahmad M, Khazaal SS, Hussein NH. Chitosan extracted from aspergillus flavus shows synergistic effect, eases quorum sensing mediated virulence factors and biofilm against nosocomial pathogen pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;107(Part A):52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.08.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning Y, Yan A, Yang K, Wang Z, Li X, Jia Y. Antibacterial activity of phenyllactic acid against Listeria monocytogenes and Escherichia coli by dual mechanisms. Food Chem. 2017;228:533–540. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.01.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira CS, Thompson JA, Xavier KB. AI-2-mediated signalling in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2013;37:156–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surette MG, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7046–7050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen N, Ganzle MG, Vogel RF. Influence of peptide supply and cosubstrates on phenylalanine metabolism of Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis DSM20451T and Lactobacillus plantarum TMW1.468. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:3832–3839. doi: 10.1021/jf052733e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue WM, Yu WT, Liu XD, He X, Wang W. Chemical method of breaking the cell-loaded sodium alginate/chitosan microcapsules. Chem Res Chin Univ. 2004;25:1342–1346. [Google Scholar]

- Yu S, Zhu L, Zhou C, An T, Jiang B, Mu W. Enzymatic production of D-3-phenyllactic acid by Pediococcus pentosaceusD-lactate dehydrogenase with NADH regeneration by Ogataea parapolymorpha formate dehydrogenase. Biotechnol Lett. 2014;36:627–631. doi: 10.1007/s10529-013-1404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W, Ding H, Lv C, Hu S, Huang J, Zheng X, Yao S, Mei L. Two-step biocatalytic reaction using recombinant Escherichia coli cells for efficient production of phenyllactic acid from l-phenylalanine. Process Biochem. 2018;64:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2017.09.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]