Abstract

Background

Our previous data suggested that three single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), rs1048661, rs3825942, and rs2165241, of the lysyl oxidase-like 1 gene (LOXL1) are significantly associated with exfoliation syndrome (XFS) and exfoliation glaucoma (XFG). The following study investigated other SNPs that potentially effect XFS/XFG.

Methods

A total of 216 Uygur patients diagnosed with XFS/XFG, and 297 Uygur volunteers were admitted to the First Affiliated Hospital at Xinjiang Medical University between January 2015 and October 2017. Blood samples were collected by venipuncture. Alleles and genotypes of LOXL1, TBC1D21, ATXN2, APOE, CLU, AFAP1, TXNRD2, CACNA1A, ABCA1, GAS7, and CNTNAP2 were analyzed by direct sequencing.

Results

The allele G of rs41435250 of LOXL1 was a risk allele for XFS/XFG (P < 0.001), whereas the allele G of rs893818 of LOXL1 was a protective allele for XFS/XFG (P < 0.001). After adjusting all data for age and gender, the following results were obtained: the frequency of genotype CC for rs7137828 of ATXN2 was significantly higher in XFS/XFG patients than in controls (P = 0.027), while no significance was found with reference to the frequency of genotype TT. The frequency of genotype GG for rs893818 of LOXL1 (P < 0.001) and the frequency of genotype AA were both significantly higher in XFS/XFG groups compared to the control group (P < 0.001). In addition, the frequency of genotype TT for rs41435250 of LOXL1 was higher in XFS/XFG patients than in controls (P = 0.003), while no significant difference was found with reference to the frequency of genotype GG after adjusting for age and gender. In addition, the haplotypes G-A/T-G/G-G for rs41435250 and rs893818 were significantly associated with XFS/G.

Conclusions

With reference to LOXL1, the rs41435250 resulted as a risk factor and rs893818 as a protective factor for XFS/XFG in the Uygur populations. Meanwhile, the rs16958445 of TBC1D21 and the rs7137828 of ATXN2 have also shown to be associated with pathogenesis of XFS/XFG.

1. Introduction

Exfoliation syndrome (XFS) is an age-related, systemic, elastic microfibrillopathy characterized by deposition and progressive accumulation of a white, fibrillary, extracellular material affecting intraocular and extraocular tissues [1]. A recent study has suggested a high prevalence of XFS in the Uygur population [2, 3]. XFS is characterized by rapid progression, high resistance to medical therapy, and poor prognosis and may lead to exfoliation glaucoma (XFG), open-angle glaucoma, angle-closure glaucoma, and acceleration of cataract insensibly [4]. In China, especially in Xinjiang, many XFS/XFG patients lost their visual acuity due to the lack of medical treatment.

Genetic factors have an important role in XFS pathogenesis. Our previous data have suggested that three single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), i.e.,rs1048661, rs3825942, and rs2165241, of the lysyl oxidase-like 1 gene (LOXL1) were significantly associated with XFS and XFG [5]. Moreover, Yao et al. have discovered that rs4886467, rs4558370, rs4461027, rs4886761, and rs16958477 SNPs located in the LOXL1 gene promoter region are risk factors for XFS [6]. In addition, many other SNPs, such as rs429358 and rs7412 located on apolipoprotein E (APOE) [7], rs2107856 and rs2141388 of contactin-associated protein-like 2 (CNTNAP2) [8], rs41435250 and rs893818 of LOXL1 [9], rs16958445 of TBC1 domain family member 21 (TBC1D21) [10], rs7137828 of autosomal-dominant ataxin 2 (ATXN2), rs35934224 of thioredoxin reductase 2 (TXNRD2), rs11732100 of actin filament-associated protein 1 (AFAP1), rs2472493 of ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1 (ABCA1), rs9897123 of growth arrest-specific 7 (GAS7) [11], rs4926244 of calcium voltage-gated channel subunit alpha1 A (CACNA1A) [12], and rs2279590 of clusterin (CLU) [13], have been associated with XFS/XFG. Accordingly, the aim of this study is to investigate whether these SNPs also affect XFS/XFG.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

The Ethical Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University, China, approved this study. In addition, the informed consent was obtained from all participants after explaining the objective and nature of the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Study Population

A total of 216 Uygur patients who were diagnosed as XFS/XFG and 297 normal Uygur volunteers who were admitted at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University, the First People's Hospital of Kashgar, and the Kuqa County Hospital between January 2015 and October 2017 were enrolled in this study. XFS was diagnosed based on the previously described approach [5]. In brief, XFS was diagnosed by exfoliation materials on the anterior lens capsule or on the pupil margin in either eye with dilation of the pupils. The inclusion criteria were the following: (1) IOP ≥22 mmHg in either eye; (2) glaucomatous changes on the optic disc, defined as a cup-to-disc ratio >0.7 in either eye or an asymmetric cup-to-disc ratio >0.2 or notching of the disc rim; and (3) characteristic glaucomatous visual field loss [14]. Patients with other causes of secondary glaucoma, such as uveitis, pigment dispersion syndrome, and iridocorneal endothelial syndrome, were excluded from the study. All study subjects were unrelated and received comprehensive ophthalmic examinations.

Peripheral blood samples (2-3 ml) were collected from each subject by venipuncture. Genomic deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was extracted from the whole blood using a Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (The Beijing Genomics Institute, Beijing, China). The SNPs (rs429358, rs7412, rs2107856, rs2141388, rs41435250, rs893818, rs16958445, rs7137828, rs35934224, rs11732100, rs2472493, rs9897123, rs4926244, and rs2279590) were amplified by photoconductive relay (PCR) and directly sequenced [7–13]. Two sets of primers were used for amplification by PCR.

Genotypes of these SNPs were determined by direct DNA sequencing, using a BigDye Terminator v3.1 Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in a 3730XL capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems). The sequences were analyzed by sequencing analysis software Chromas (Technelysium Pty Ltd., Queensland, Australia).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v17.0 software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) analysis was tested by using the χ2 test in SAS/Genetics v9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The comparison of allelic and genotypic frequencies between the patient and control groups, as well as haplotype association analysis, was performed using a standard χ2 test. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Relative risk association was estimated by calculating odds ratios (OR) along with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

3. Results

A total of 216 Uygur XFS/XFG patients (case group) and 297 normal Uygur volunteers (control group) were included in the study. In the case group, there were 146 males and 70 females (average age: 68 years), while in the control group, there were 159 males and 138 females (average age: 62 year) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline of the two groups.

| Case | Control | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=216 | n=297 | |||

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 68.90 ± 8.47 | 62.46 ± 9.94 | 9.13 | <0.001 |

| Gender (M/F), n (%) | 146 (67.59%)/70 (32.41%) | 159 (53.54%)/138 (46.45%) | 10.25 | <0.001 |

M:male; F:female.

All SNPs underwent the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium test before further data analysis. Besides rs7137828 that deviated from HWE (P=0.006) in the control group and rs35934224 that deviated from HWE (P=0.005) in the case group, other SNPs were all in line with the HWE Table 2.

Table 2.

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium test of these SNPs.

| GeneName | SNP | HWE_Case | HWE_Control | HWE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOXL1 | rs893818 | 0.255 | 0.310 | 0.324 |

| LOXL1 | rs41435250 | 0.497 | 1.000 | 0.505 |

| TBC1D21 | rs16958445 | 0.111 | 0.555 | 0.553 |

| ATXN2 | rs7137828 | 1.000 | 0.006 | 0.025 |

| CNTNAP2 | rs2107856 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| CNTNAP2 | rs2141388 | 0.895 | 0.908 | 0.795 |

| APOE | rs429358 | 0.484 | 0.755 | 0.253 |

| APOE | rs7412 | 0.310 | 0.632 | 0.299 |

| CLU | rs2279590 | 0.367 | 1.000 | 0.490 |

| CACNA1A | rs4926244 | 0.074 | 0.616 | 0.099 |

| ABCA1 | rs2472493 | 0.895 | 0.646 | 0.862 |

| GAS7 | rs9897123 | 1.000 | 0.122 | 0.279 |

| AFAP1 | rs11732100 | 0.692 | 0.482 | 0.793 |

| TXNRD2 | rs35934224 | 0.005 | 1.000 | 0.101 |

Besides rs7137828 that deviated from the HWE in the control group and rs35934224 that deviated from the HWE in the case group, other SNPs were all in line with the HWE.

The allele association analysis showed that the frequency of allele G of rs41435250 and rs893818 of LOXL1 was significantly higher in XFS/XFG patients than in controls (rs41435250: P < 0.001, OR = 1.791, 95% CI: 1.334–2.405; rs893818: P < 0.001, OR = 0.423, 95% CI: 0.318–0.563), while no significant differences were found for other alleles (P > 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Allele association analysis with these SNPs.

| SNP | XFS/XFG | Control | χ 2 | P | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBC1D21 | |||||

| rs16958445 | |||||

| Allele | |||||

| G | 432 | 583 | 3.025 | 0.082 | 1.369 (0.960–1.953) |

| A | 70 | 69 | |||

|

| |||||

| ATXN2 | |||||

| rs7137828 | |||||

| Allele | |||||

| T | 429 | 531 | 3.272 | 0.070 | 0.7467 (0.544–1.025) |

| C | 73 | 121 | |||

|

| |||||

| APOE | |||||

| rs429358 | |||||

| Allele | |||||

| T | 452 | 587 | |||

| C | 50 | 65 | <0.001 | 0.996 | 0.999 (0.677–1.473) |

|

| |||||

| rs7412 | |||||

| Allele | |||||

| C | 468 | 610 | |||

| T | 34 | 42 | 0.051 | 0.822 | 1.055 (0.661–1.685) |

|

| |||||

| CLU | |||||

| rs2279590 | |||||

| Allele | |||||

| C | 351 | 455 | |||

| T | 151 | 197 | 0.002 | 0.961 | 0.994 (0.771–1.280) |

|

| |||||

| AFAP1 | |||||

| rs11732100 | |||||

| Allele | |||||

| C | 402 | 524 | |||

| T | 100 | 128 | 0.015 | 0.903 | 1.018 (0.760–1.364) |

|

| |||||

| TXNRD2 | |||||

| rs35934224 | |||||

| Allele | |||||

| C | 446 | 574 | |||

| T | 56 | 78 | 0.180 | 0.671 | 0.924 (0.642–1.331) |

|

| |||||

| CACNA1A | |||||

| rs4926244 | |||||

| Allele | |||||

| T | 401 | 515 | |||

| C | 101 | 137 | 0.138 | 0.710 | 0.947 (0.710–1.263) |

|

| |||||

| ABCA1 | |||||

| rs2472493 | |||||

| Allele | |||||

| A | 301 | 391 | |||

| G | 201 | 261 | <0.001 | 0.998 | 1.000 (0.789–1.269) |

|

| |||||

| LOXL1 | |||||

| rs41435250 | |||||

| Allele | |||||

| G | 379 | 552 | |||

| T | 123 | 100 | 15.280 | <0.001 | 1.791 (1.334–2.405) |

|

| |||||

| rs893818 | |||||

| Allele | |||||

| G | 418 | 442 | |||

| A | 84 | 210 | 35.780 | <0.001 | 0.423 (0.318–0.563) |

|

| |||||

| GAS7 | |||||

| rs9897123 | |||||

| Allele | |||||

| C | 249 | 341 | |||

| T | 253 | 311 | 0.827 | 0.363 | 1.114 (0.883–1.406) |

|

| |||||

| CNTNAP2 | |||||

| rs2107856 | |||||

| Allele | |||||

| G | 299 | 390 | |||

| T | 203 | 262 | 0.008 | 0.930 | 1.011 (0.797–1.281) |

|

| |||||

| rs2141388 | |||||

| Allele | |||||

| C | 301 | 391 | |||

| T | 201 | 261 | <0.001 | 0.998 | 1.000 (0.789–1.269) |

G allele of rs41435250 of LOXL1 was the risk allele for the disorder. In contrast, G allele of rs893818 of LOXL1 was the protective allele for the disorder. Other alleles of SNPs showed no statistical significance.

The genotype association analysis showed that the frequency of genotype AA for rs16958445 of TBC1D21 was higher in XFS/XFG patients than in controls (P=0.033, OR = 5.481, 95% CI: 1.151–26.11), while the frequency of genotype GG was not significantly different between the two groups. After adjusting all data for age and gender, the following results were obtained: the frequency of genotype CC for rs7137828 of ATXN2 was significantly higher in XFS/XFG patients than in controls (P=0.027, OR = 0.322, 95% CI: 0.118–0.879), while no significant differences were found with reference to the frequency of genotype TT. The frequency of genotype GG for rs893818 of LOXL1 (P < 0.001, OR = 0.511, 95% CI: 0.358–0.729) and the frequency of genotype AA were both significantly higher in the XFS/XFG group compared to the control group (P < 0.001, OR = 0.095, 95% CI: 0.033–0.272). In addition, the frequency of genotype TT for rs41435250 of LOXL1 was higher in XFS/XFG patients than in controls (P=0.003, OR = 3.902, 95% CI: 1.580–9.640), while no significant difference was found with reference to the frequency of genotype GG after adjusting for age and gender. All data are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Genotype association analysis with these SNPs.

| Gene/SNP | XFS/XFG | Control | p | OR (95% CI) | Adjusted-P | Adjusted-OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBC1D21 | ||||||

| rs16958445 | ||||||

| Genotype | ||||||

| GG | 189 | 259 | 0.532 | 1.138 (0.758–1.71) | 0.114 | 1.465 (0.913–2.351) |

| GA | 54 | 65 | 0.033 | 5.481 (1.151–26.110) | 0.043 | 5.439 (1.053–28.090) |

| AA | 8 | 2 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| ATXN2 | ||||||

| rs7137828 | ||||||

| Genotype | ||||||

| TT | 183 | 224 | 0.705 | 0.929 (0.635–1.360) | 0.955 | 1.013 (0.654–1.569) |

| TC | 63 | 83 | 0.027 | 0.322 (0.118–0.879) | 0.030 | 0.299 (0.100–0.891) |

| CC | 5 | 19 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| APOE | ||||||

| rs429358 | ||||||

| Genotype | ||||||

| TT | 202 | 263 | 0.910 | 1.025 (0.673–1.560) | 0.532 | 1.171 (0.714–1.920) |

| TC | 48 | 61 | 0.727 | 0.651 (0.059–7.230) | 0.773 | 0.697 (0.060–8.091) |

| CC | 1 | 2 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| rs7412 | ||||||

| Genotype | ||||||

| CC | 219 | 286 | 0.907 | 1.031 (0.619–1.717) | 0.873 | 1.049 (0.585–1.882) |

| CT | 30 | 38 | 0.790 | 1.306 (0.183–9.344) | 0.887 | 1.172 (0.132–10.400) |

| TT | 2 | 2 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| CLU | ||||||

| rs2279590 | ||||||

| Genotype | ||||||

| CC | 126 | 159 | 0.604 | 0.912 (0.644–1.292) | 0.298 | 0.807 (0.538–1.209) |

| CT | 99 | 137 | 0.760 | 1.094 (0.616–1.943) | 0.171 | 1.586 (0.819–3.071) |

| TT | 26 | 30 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| AFAP1 | ||||||

| rs11732100 | ||||||

| Genotype | ||||||

| CC | 162 | 208 | 0.678 | 0.927 (0.649–1.324) | 0.922 | 0.979 (0.650–1.477) |

| CT | 78 | 108 | 0.442 | 1.412 (0.585–3.407) | 0.576 | 0.711 (0.215–2.350) |

| TT | 11 | 10 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| TXNRD2 | ||||||

| rs35934224 | ||||||

| Genotype | ||||||

| CC | 203 | 252 | 0.118 | 0.709 (0.461–1.091) | 0.175 | 0.710 (0.433–1.165) |

| CT | 40 | 70 | 0.142 | 2.483 (0.737–8.362) | 0.258 | 2.245 (0.553–9.114) |

| TT | 8 | 4 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| CACNA1A | ||||||

| rs4926244 | ||||||

| Genotype | ||||||

| TT | 165 | 205 | 0.349 | 0.840 (0.584–1.209) | 0.224 | 0.774 (0.512–1.170) |

| TC | 71 | 105 | 0.684 | 1.165 (0.559–2.426) | 0.826 | 0.901 (0.356–2.282) |

| CC | 15 | 16 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| ABCA1 | ||||||

| rs2472493 | ||||||

| Genotype | ||||||

| AA | 91 | 115 | 0.713 | 0.934 (0.650–1.343) | 0.831 | 0.955 (0.626–1.457) |

| AG | 119 | 161 | 0.888 | 1.036 (0.631–1.702) | 0.906 | 0.966 (0.544–1.716) |

| GG | 41 | 50 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| LOXL1 | ||||||

| rs41435250 | ||||||

| Genotype | ||||||

| GG | 145 | 233 | 0.006 | 1.663 (1.158–2.388) | 0.071 | 1.478 (0.966–2.259) |

| GT | 89 | 86 | 0.003 | 3.902 (1.580–9.640) | 0.003 | 5.276 (1.748–15.930) |

| TT | 17 | 7 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| rs893818 | ||||||

| Genotype | ||||||

| GG | 171 | 154 | <0.001 | 0.511 (0.358–0.729) | <0.001 | 0.4449 (0.293–0.676) |

| GA | 76 | 134 | <0.001 | 0.095 (0.033–0.272) | <0.001 | 0.119 (0.039–0.356) |

| AA | 4 | 38 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| GAS7 | ||||||

| rs9897123 | ||||||

| Genotype | ||||||

| CC | 62 | 82 | 0.739 | 0.934 (0.625–1.396) | 0.440 | 0.833 (0.523–1.325) |

| CT | 125 | 177 | 0.335 | 1.263 (0.785–2.033) | 0.808 | 0.935 (0.542–1.612) |

| TT | 64 | 67 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| CNTNAP2 | ||||||

| rs2107856 | ||||||

| Genotype | ||||||

| GG | 89 | 117 | 0.917 | 1.02 (0.709–1.467) | 0.687 | 1.091 (0.715–1.665) |

| GT | 121 | 156 | 0.947 | 1.017 (0.622–1.664) | 0.537 | 1.194 (0.681–2.094) |

| TT | 41 | 53 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| rs2141388 | ||||||

| Genotype | ||||||

| CC | 91 | 118 | 0.981 | 0.996 (0.692–1.431) | 0.772 | 1.064 (0.698–1.624) |

| CT | 119 | 155 | 0.990 | 1.003 (0.614–1.639) | 0.570 | 1.177 (0.672–2.060) |

| TT | 41 | 53 | ||||

The genotypes AA for rs16958445 of TBC1D21 and GG/TT for rs41435250 of LOXL1 were risk genotypes for the disease. The genotypes CC for rs7137828 of ATXN2 and GG/AA for rs893818 of LOXL1 were protective genotypes for the disease.

Moreover, our results indicated that all MAFs were greater than 0.05, which further suggested that all SNPs were statistically significant (Table 5).

Table 5.

MAFs of these SNPs.

| Gene | SNP | Ref allele | Alt allele | Case MAF | Control MAF | Total MAF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOXL1 | rs893818 | G | A | 0.167 | 0.322 | 0.255 |

| LOXL1 | rs41435250 | G | T | 0.245 | 0.153 | 0.193 |

| TBC1D21 | rs16958445 | G | A | 0.139 | 0.106 | 0.121 |

| ATXN2 | rs7137828 | T | C | 0.145 | 0.186 | 0.168 |

| CNTNAP2 | rs2107856 | G | T | 0.404 | 0.402 | 0.403 |

| CNTNAP2 | rs2141388 | C | T | 0.400 | 0.400 | 0.400 |

| APOE | rs429358 | T | C | 0.100 | 0.100 | 0.100 |

| APOE | rs7412 | C | T | 0.068 | 0.064 | 0.066 |

| CLU | rs2279590 | C | T | 0.301 | 0.302 | 0.302 |

| CACNA1A | rs4926244 | T | C | 0.201 | 0.210 | 0.206 |

| ABCA1 | rs2472493 | A | G | 0.400 | 0.400 | 0.400 |

| GAS7 | rs9897123 | C | T | 0.496 | 0.477 | 0.489 |

| AFAP1 | rs11732100 | C | T | 0.199 | 0.196 | 0.198 |

| TXNRD2 | rs35934224 | C | T | 0.112 | 0.120 | 0.116 |

All MAFs were greater than 0.05, which pointed out that all these SNPs were statistically significant.

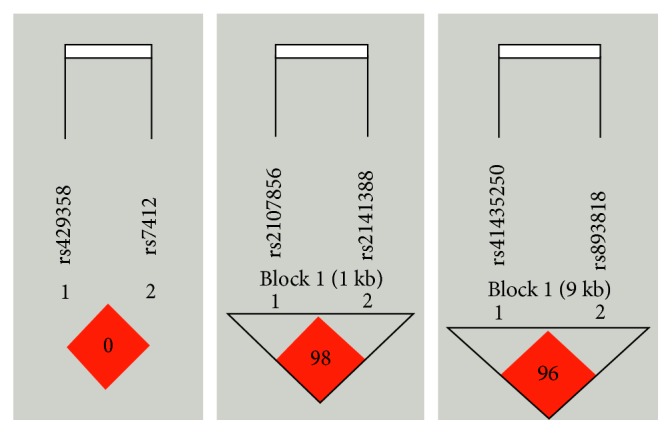

After the study of alleles and genotypes, we screened out the LOXL1, APOE, and CNTNAP2 for the haplotype association analysis. The genotyping graphs for these SNPs are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The genotyping graphs for LOXL1, APOE, and CNTNAP2.

For the rs41435250 and rs893818 of LOXL1, three haplotypes were observed. As shown in Table 6, all haplotypes showed a significantly higher frequency in XFS/XFG patients than in controls: GA (P ≤ 0.001, OR = 0.417, 95% CI: 0.313–0.556), TG (P ≤ 0.001, OR = 1.772, 95% CI: 1.320–2.380), and GG (P=0.028, OR = 1.302, 95% CI: 1.030–1.648). Furthermore, after adjusting for age and gender, the similar data were obtained (Table 7): GA (P ≤ 0.001, OR = 0.400, 95% CI: 0.286–0.559), TG (P=0.001, OR = 1.769, 95% CI: 1.251–2.503), and GG (P=0.029, OR = 1.356, 95% CI: 1.032–1.782). We also observed three haplotypes for rs429358 and rs7412 of APOE and rs2107856 and rs2141388 of CNTNAP2; nevertheless, there was no connection between the case and control group.

Table 6.

Haplotype association analysis between these SNPs.

| Gene | Haplotype | Case (proportion) | Control (proportion) | P value | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs41435250 | rs893818 | ||||||

| LOXL1 | G | A | 83 (0.165) | 210 (0.322) | ≤0.001 | 0.417 | 0.313–0.556 |

| T | G | 122 (0.243) | 100 (0.153) | ≤0.001 | 1.772 | 1.320–2.380 | |

| G | G | 296 (0.590) | 342 (0.525) | 0.028 | 1.302 | 1.030–1.648 | |

|

| |||||||

| rs429358 | rs7412 | ||||||

| APOE | T | C | 418 (0.833) | 545 (0.836) | 0.884 | 0.977 | 0.715–1.336 |

| C | C | 50 (0.100) | 65 (0.100) | 0.996 | 0.999 | 0.677–1.473 | |

| C | T | 34 (0.068) | 42 (0.064) | 0.822 | 1.055 | 0.661–1.685 | |

|

| |||||||

| rs2107856 | rs2141388 | ||||||

| CNTNAP2 | T | T | 201 (0.400) | 261 (0.400) | 0.998 | 1.000 | 0.789–1.269 |

| G | C | 299 (0.596) | 390 (0.598) | 0.930 | 0.990 | 0.781–1.254 | |

The haplotypes GG/TG/GA for the SNPs rs41435250 and rs893818 were significantly associated with XFS/XFG.

Table 7.

Haplotype (adjusted) association analysis between these SNPs.

| Gene | Haplotype | Case (proportion) | Control (proportion) | P value | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs41435250 | rs893818 | ||||||

| LOXL1 | G | A | 67 (0.155) | 189 (0.319) | ≤0.001 | 0.400 | 0.286–0.559 |

| T | G | 101 (0.234) | 89 (0.150) | 0.001 | 1.769 | 1.251–2.503 | |

| G | G | 264 (0.611) | 314 (0.530) | 0.029 | 1.356 | 1.032–1.782 | |

|

| |||||||

| rs429358 | rs7412 | ||||||

| APOE | T | C | 360 (0.833) | 494 (0.834) | 0.609 | 0.910 | 0.634–1.307 |

| C | C | 42 (0.097) | 57 (0.096) | 0.643 | 1.113 | 0.707–1.753 | |

| C | T | 30 (0.069) | 41 (0.069) | 0.834 | 1.059 | 0.621–1.806 | |

|

| |||||||

| rs2107856 | rs2141388 | ||||||

| CNTNAP2 | T | T | 180 (0.417) | 239 (0.404) | 0.569 | 1.083 | 0.823–1.424 |

| G | C | 250 (0.579) | 352 (0.595) | 0.523 | 0.915 | 0.696–1.202 | |

The haplotypes GG/TG/GA for the SNPs rs41435250 and rs893818 were significantly associated with XFS/XFG.

4. Discussion

So far, numerous studies have focused on the polymorphisms of LOXL1. Our previous studies have shown that there were polymorphisms of LOXL1 in different alleles and genotypes of different SNPs in XFS/XFG of different ethnic groups. In this study, we found two SNPs (rs41435250 and rs893818) of LOXL1 that were polymorphic and associated with XFS/XFG. Meanwhile, we also examined other genes which were previously affirmed to have polymorphisms in XFS/XFG. We found that rs16958445 of TBC1D21 and rs7137828 of ATXN2 were significantly associated with XFS/XFG. Yet, three haplotypes for rs429358 and rs7412 of APOE and rs2107856 and rs2141388 of CNTNAP2 had no connection between the case and control group.

As a result, LOXL1 is still the susceptibility gene of XFS/XFG in Uygur populations. The rs1048661, rs3825942, rs2165241, rs4886467, rs4558370, rs4461027, rs4886761, rs16958477 [5, 6], and rs41435250 resulted to be risk factors, while rs893818 resulted to be a protective factor for XFS/XFG in the Uygur population.

Genes, such as TBC1D21, ATXN2, APOE, CLU, AFAP1, TXNRD2, CACNA1A, ABCA1, GAS7, and CNTNAP2, have been associated with glaucoma. In this study, we discovered that SNPs, rs16958445 of TBC1D21 and the rs7137828 of ATXN2, had an important role in the pathogenesis of XFS/XFG in the Uygur population. Nonetheless, it is necessary to note that there may be other factors affecting the pathogenesis of XFS/G, which should be addressed by future studies.

In this research, we gathered a number of genes to study the polymorphisms of the special ethnic groups, thus providing valuable information and expanding the knowledge on the gene mechanism of XFS/XFG. Nonetheless, the current study has some limitations that should be pointed out. Although the patients were recruited from the three largest areas of Xinjiang, the sample representativeness may be somewhat inaccurate, which could be addressed by expanding the sample size and thus improving the accuracy. We found that multiple gene polymorphisms had an important role in the pathogenesis of the disorder in Uygur patients, but we cannot exclude the possibility that other additional genetic or environmental factors also participate in modifying the development of this disorder.

Acknowledgments

The Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81360153) supported this study.

Abbreviations

- XFS:

Exfoliation syndrome

- XFG:

Exfoliation glaucoma

- SNPs:

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms

- LOXL1:

Lysyl oxidase-like 1 gene

- APOE:

Apolipoprotein E

- CNTNAP2:

Contactin-associated protein-like 2

- TBC1D21:

TBC1 domain family member 21

- ATXN2:

Autosomal-dominant ataxin 2

- TXNRD2:

Thioredoxin reductase 2

- AFAP1:

Actin filament-associated protein 1

- ABCA1:

ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1

- GAS7:

Growth arrest-specific 7

- CACNA1A:

Calcium voltage-gated channel subunit alpha1 A

- CLU:

Clusterin

- DNA:

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- PCR:

Photoconductive relay

- HWE:

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium

- OR:

Odds ratios

- CI:

95% confidence intervals.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Yi-Nu Ma was in charge of statistical analysis and manuscript writing; Ting-Yu Xie was involved in the diagnosis and screening of patients; and Xue-Yi Chen was the instructor.

References

- 1.Damji K. F. Progress in understanding pseudoexfoliation syndrome and pseudoexfoliation-associated glaucoma. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology. 2007;42(5):657–658. doi: 10.3129/i07-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiao L., Liu L., Zhang J., Liu J., Lv H. Investigation of sight restoring operation of pseudoexfoliation syndrome associated cataract in Kashi area in Xinjiang. Chinese Journal of Ocular Trauma and Occupational Eye. Dis2005;28(7):485–456. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie T., Chen X., Mutellip Epidemiology of pseudoexfoliation syndrome in aged Uygur farmers in Xinjiang. Chinese Journal of Geriatrics. 2008;27(3):229–230. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ritch R., Schlotzer-Schrehardt U. Exfoliation syndrome. Survey of Ophthalmology. 2001;45(4):265–315. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6257(00)00196-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayinu, Chen X. Evaluation of LOXL1 polymorphisms in exfoliation syndrome in the Uygur population. Molecular Vision. 2011;17:1734–1744. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yao L., Ding R.-X., Guo M.-Y., Chen X.-Y. Correlations between single nucleotide polymorphisms in the lysyl oxidase-like 1 gene promoter region and exfoliation syndrome in the Uighur population. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medical Sciences. 2016;9(10):19709–19716. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiras D., Tzika K., Kokotas H., et al. Development of novel LOXL1 genotyping method and evaluation of LOXL1, APOE and MTHFR polymorphisms in exfoliation syndrome/glaucoma in a Greek population. Molecular Vision. 2013;19:1006–1016. http://www.molvis.org/molvis/v19/1006. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krumbiegel M., Pasutto F., Schlötzer-Schrehardt U., et al. Genome-wide association study with DNA pooling identifies variants at CNTNAP2 associated with pseudoexfoliation syndrome. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2011;19(2):186–193. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weisschuh D., Miranda-Duarte A., Zenteno J. C. The T allele of lysyl oxidase-like 1 rs41435250 is a novel risk factor for pseudoexfoliation syndrome and pseudoexfoliation glaucoma independently and through intragenic epistatic interaction. Molecular Vision. 2013;19:1937–1944. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakano M., Ikeda Y., Tokuda Y., et al. Novel common variants and susceptible haplotype for exfoliation glaucoma specific to Asian population. Scientific Reports. 2014;4(1) doi: 10.1038/srep05340.5340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiggs J. L., Pasquale L. R. Genetics of glaucoma. Human Molecular Genetics. 2017;26(1):R21–R27. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aung T., Ozaki M., Mizoguchi T., et al. A common variant mapping to CACNA1A is associated with susceptibility to exfoliation syndrome. Nature Genetics. 2015;47(4):387–392. doi: 10.1038/ng.3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bao J. Louis R. P., Kan J. H., Verbin H. L., Haines J. L., Wiggs J. L. Association of clusterin (CLU) variants and exfoliation syndrome: an analysis in two caucasian studies and a metaanalysis. Experimental Eye Research. 2015;139:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster P. J., Buhrmann R., Quigley H. A., Johnson G. J. The definition and classification of glaucoma in prevalence surveys. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2002;86(2):238–242. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.2.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.